Abstract

Natural extracts have been of very high interest since ancient time due to their enormous medicinal use and researcher’s attention have further gone up recently to explore their phytochemical compositions, properties, potential applications in the areas such as, cosmetics, foods etc. In this present study phytochemical analysis have been done on the aqueous and methanolic Moringa leaves extracts using Gas Chromatography-Mass spectrometry (GCMS) and their free radical scavenging potency (FRSP) studied using 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical for further applications. GCMS analysis revealed an extraction of range of phytochemicals in aqueous and methanolic extracts. In aqueous, extract constituents found with high percent peak area are Carbonic acid, butyl 2-pentyl ester (20.64%), 2-Isopropoxyethyl propionate (16.87%), Butanedioic acid, 2-hydroxy-2-methyl-, (3.14%) (also known as Citramalic acid that has been rarely detected in plant extracts) and many other phytochemicals were detected. Similarly, fifty-four bio components detected in methanolic extract of Moringa leaves, which were relatively higher than the aqueous extract. Few major compounds found with high percent peak area are 1,3-Propanediol, 2-ethyl-2- (hydroxymethyl)- (21.19%), Propionic acid, 2-methyl-, octyl ester (15.02%), Ethanamine, N-ethyl-N-nitroso- (5.21%), and 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid etc. FRSP for methanolic extract was also recorded much higher than aqueous extract. The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) of Moringa aqueous extract observed is 4.65 µl/ml and for methanolic extract 1.83 µl/ml. These extracts can act as very powerful antioxidants, anti-inflammatory ingredient for various applications in diverse field of food, cosmetics, medicine etc.

Keyword: Moringa, Gas chromatography-mass spectra, Phytochemicals, Free radical scavenging, IC50, Antioxidant

1. Introduction

Plants and extracts of their various sections have been used for their medical characteristics and to cure specific ailments as well as general tonics, meals, and other methods to increase the body's immunity and vigor since ancient times (Ullah et al., 2020, Ageel et al., 1986, Gamal et al., 2010, Purena et al., 2018). However, since last few decades the interest of researchers has gone up dramatically to understand their detailed compositions and also to explore and establish their potential applications in diverse areas. In fact, it is the need of the hour to leverage the vital power of the nature to combat proliferating diseases like cancer, heart attacks, diabetes, rapid skin aging etc. and upcoming varieties of new alarming health concerns like recent concerns of Coronavirus disease in 2019 (COVID-19), which affects the respiratory system acutely (Varahachalam et al., 2021, Paliwal et al., 2020).

Different parts like seeds, roots, stem, bark, leaves, flower and fruits of the plant have their own phytochemical compositions and potential medicinal properties. Moringa have various species across the globe which are known for their variety of usages few examples of Moringa species are Moringa longituba, Moringa drouhardii, Moringa ovalifolia etc. (Leone et al., 2015). Moringa Oleifera is one of the magical plants considered in India due to its high medicinal properties. However, there is still a lot to unleash the potential of Moringa Oleifera by understanding their phytocomponents and variation in extraction due to solvents, understanding their potential properties and to establish their applications in various fields. The present study is focused to investigate the phytochemical composition of the Moringa Oleifera leave’s aqueous and alcoholic extracts by GC-MS and their free radical scavenging potencies, which make them useful for their further applications in cosmetic products to prevent skin damage due to free radicals generated because of pollution, UV from sunlight, smoke, also for animal feed etc.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Methanol of 99.8% purity, HPLC grade from SD fine chemical limited, distilled water having pH 5.3–7 and conductivity 2µS/cm. Raw leaves powder of Moringa Oleifera of India origin grown in the climate of tropics and sub tropics were used for the investigation. Extra pure 2,2-Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) from SRL Pvt. Ltd was used for the free radical scavenging studies.

2.2. Preparation of aqueous and Methanolic extracts

The suspension of 5% Moringa Oleifera leaves were prepared in distilled water and in Methanol separately and were subjected to continuous stirring at 45–50 °C for 8 h respectively. The resultant samples were filtered through Whatman filter paper 1 to extract the phytochemicals. The filtrates were concentrated by evaporating the solvents and were used to prepare the samples for further analysis.

2.3. GC-MS analysis

The analysis of extracted phytochemicals of M. Oleifera leaves were done using GC-MS Agilent Technologies-7820A GC system. Gas Chromatogram coupled with Mass Spectrometer of Agilent Technologies-5977MSD equipped with an Agilent Technologies GCMS capillary column HP-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25µ) composed of 5% diphenyl 95% Dimethyl polysiloxane. An electron ionization system with ionizing energy of 70 eV was used. Helium gas (99.99%) was used as the carrier gas at constant flow rate 1 mL/min and an injection volume of 1 µl was employed at split ratio of 50:1, injector temperature was at 60 ˚C and ion source temperature was at 250˚C. Mass spectra were recorded using voltage of 70 eV. The relative percentage amount of each component were calculated by comparing its average peak area to the total areas, software of GC-MS Mass Hunter used for spectra and chromatograms analysis.

2.4. Phytocomponents identification

The phytochemicals were identified based on their retention time, percentage of peak area and pattern of mass spectra and its comparison with the data of library of NIST11.LIB of National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

2.5. Anti-oxidant/free radical scavenging potency (FRSP) using diphenyl picrylhydrazyl (DPPH)

The Anti-oxidant efficacy and in other words free radical scavenging potency (FRSP) of the aqueous and methanolic extract of the Moringa leaves powder were determined by using DPPH. Methanolic solution of 1.52*10-4 M of DPPH was used in 1:1 ratio with Moringa aqueous and methanolic extracts at varying concentrations, studied the scavenging activity as a function of time. FRSP percentage rate was studied after incubating the mixture of DPPH and extracts for 30 min and recording the UV absorption at 517 nm. The same was used to calculate the concentration of antioxidant required to reduce the concentration of DPPH to 50% (IC50). Higher value of IC50 indicates the lower antioxidant activity and vice a versa. The control samples were prepared using DPPH solution and mixing only with respective solvents (Aqua/Methanol) at 1:1 ratio and measured at 517 nm.

| FRSP% = (Controlabs - Sampleabs) x100/Controlabs |

3. Results

3.1. Phytocomponent identification by GC MS of aqueous extract of M. Oleifera leaves powder

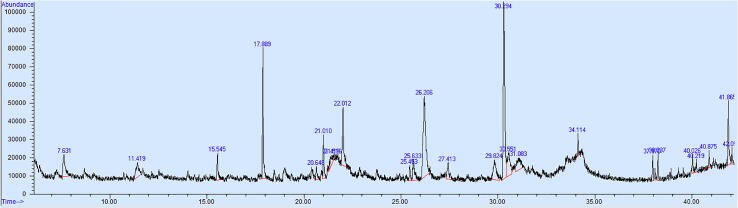

The GC-MS profile of the aqueous extract of M. Oleifera leaves is shown in Fig. 1, which reflects 25 peaks of biomolecules. Table 1 presents the phytocomponents, their retention time, peak area percentage and Molecular weight. Chemical structure of active components and their known key applications like medicinal, cosmetics etc. are tabulated in Table 2. Few major compounds found with high percent peak area are Carbonic acid, butyl 2-pentyl ester (20.64%), 2-Isopropoxyethyl propionate (16.87%), 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- (8.98%), and 1,3-Dioxolan-2-one, 4,5-dimethyl- (6.16%) additional compounds with reasonable percentage of peak area are Tetra acetyl-d-xylonic nitrile (5.03%), Azetidin-2-one 3,3-dimethyl-4-(1-aminoethyl)- (4.67%), 1,3-Dihydroxyacetone dimer (3.85%), Alpha-D-Glucose (3.44%), and Butanedioic acid, 2-hydroxy-2-methyl-, (3.14%) which is rarely been detected in plant extracts and have various applications.

Fig. 1.

GC MS of Moringa O. leaves aqueous extract.

Table 1.

List of phytochemicals identified in aqueous extract of Moringa O. leaves, their retention time and peak area% with molecular weight (grams/mole).

| Sr. No. | RT | Peak Area % | Library/ID | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.63 | 3.8551 | 1,3-Dihydroxyacetone dimer | 180 |

| 2 | 11.42 | 3.2396 | Acetic acid, [(aminocarbonyl)amino]oxo- | 132 |

| 3 | 15.54 | 2.2433 | 4(1H)-Pyrimidinone, 2,6-diamino- | 126 |

| 4 | 17.89 | 8.9858 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | 144 |

| 5 | 20.65 | 1.1214 | 2-Hexynoic acid | 112 |

| 6 | 21.01 | 3.1422 | Butanedioic acid, 2-hydroxy-2-methyl-, (S)- | 148 |

| 7 | 21.42 | 1.9275 | 3,3′-Iminobispropylamine | 131 |

| 8 | 21.52 | 0.0774 | 1-Hexanamine | 101 |

| 9 | 22.01 | 6.1627 | 1,3-Dioxolan-2-one, 4,5-dimethyl- | 116 |

| 10 | 25.45 | 1.3083 | 2-Butenethioic acid, 3-(ethylthio)-, S-(1-methylethyl) ester | 204 |

| 11 | 25.63 | 3.0349 | Propanamide, N,N-dimethyl- | 101 |

| 12 | 26.21 | 16.8738 | 2-Isopropoxyethyl propionate | 160 |

| 13 | 27.41 | 2.5622 | D-Mannoheptulose | 210 |

| 14 | 29.82 | 4.6738 | Azetidin-2-one 3,3-dimethyl-4-(1-aminoethyl)- | 142 |

| 15 | 30.29 | 20.6431 | Carbonic acid, butyl 2-pentyl ester | 188 |

| 16 | 30.55 | 5.0379 | Tetra acetyl-d-xylonic nitrile | 343 |

| 17 | 31.08 | 3.445 | .alpha.-D-Glucose | 180 |

| 18 | 34.11 | 1.2587 | 1H-Cyclopenta[c]furan-3(3aH)-one, 6,6a-dihydro-1-(1,3-dioxolan-2-yl)-, (3aR,1-trans,6a-cis)- | 196 |

| 19 | 37.97 | 1.5253 | 3-[1-(4-Cyano-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthyl)]propanenitrile | 210 |

| 20 | 38.24 | 1.4067 | Quinolinium, 1-ethyl-, iodide | 285 |

| 21 | 40.03 | 0.9462 | N-Isopropyl-3-phenylpropanamide | 191 |

| 22 | 40.22 | 0.7335 | Propanamide | 73 |

| 23 | 40.88 | 0.8805 | 1,2-Ethanediamine, N-(2-aminoethyl)- | 103 |

| 24 | 41.87 | 4.3169 | 1,4-Benzenediol, 2-methyl- | 124 |

| 25 | 42.05 | 0.5981 | Ethene, ethoxy- | 72 |

Table 2.

Phytochemicals in aqueous extract of Moringa O. leaves, their structure from NIST library and known potential applications wherever applicable.

| Ingredients | Structure | Key Applications (if any readily available) |

|---|---|---|

| 1,3-Dihydroxyacetone dimer |  |

Synthesis of polymeric biomaterials (Zelikin and Putnam, 2005) |

| Acetic acid, [(aminocarbonyl)amino]oxo- |  |

|

| 4(1H)-Pyrimidinone, 2,6-diamino- |  |

Hydroxy and amino Pyrimidines are of great interest in natural products and in the development of new drugs for various diverse areas like anti-cancer (Skoweranda et al., 1990) |

| 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- |  |

Strong Anti-oxidant (Yu et al., 2013, Čechovská et al., 2011) |

| 2-Hexynoic acid |  |

As precursor for synthesizing various biological metabolites like leucotrienes, oxylipins (Starostin et al., 2000) |

| Butanedioic acid, 2-hydroxy-2-methyl-, (S)- |  |

One of the rarely identified component in plant extracts. Mobilize the Phosphates in soil for agricultural applications to enhance the P availability (Khorassani et al., 2011) |

| 3,3′-Iminobispropylamine | This is also among the rare component identified in plant have various role in plant as well as medicinal antitumor active (Rodriguez-Garay et al., 1989, Sunkara et al., 1988, Nishio et al., 2019) | |

| 1-Hexanamine | ||

| 1,3-Dioxolan-2-one, 4,5-dimethyl- |  |

Precursor for various drugs and cyclic Carbonates have applications in Electrochemical energies (Takebe et al., 1984, Hagiyama et al., 2008) |

| 2-Butenethioic acid, 3-(ethylthio)-, S-(1-methylethyl) ester |  |

|

| Propanamide, N,N-dimethyl- |  |

|

| 2-Isopropoxyethyl propionate |  |

|

| D-Mannoheptulose |  |

D-Mannoheptulose widely studied for its activity against breast cancer and to suppress the D-glucose induced insulin release. (Al-Ziaydi et al., 2020, Courtois et al., 2001) |

| Azetidin-2-one 3,3-dimethyl-4-(1-aminoethyl)- |  |

Anti-inflammatory, ulcerogenic, and analgesic activities (Siddiqui et al., 2010) |

| Carbonic acid, butyl 2-pentyl ester |  |

|

| Tetra acetyl-d-xylonic nitrile |  |

Anti-tumor and Anti-oxidant (Imad et al., 2015, Kanhar and Sahoo, 2018) |

| Alpha-D-Glucose |  |

Source of energy, highly effective and used in food, medicine and its derivatives also have many medicinal use. (Shendurse and Khedkar, 2016, Cancelas et al., 2000) |

| 1H-Cyclopenta[c]furan-3(3aH)-one, 6,6a-dihydro-1-(1,3-dioxolan-2-yl)-, (3aR,1-trans,6a-cis)- |  |

|

| 3-[1-(4-Cyano-1,2,3,4-tetrahydronaphthyl)]propanenitrile |  |

|

| Quinolinium, 1-ethyl-, iodide |  |

|

| N-Isopropyl-3-phenylpropanamide |  |

|

| Propanamide |  |

Propanamide derivatives studied for antimicrobial and antiviral efficacy (Ölgena et al., 2008) |

| 1,2-Ethanediamine, N-(2-aminoethyl)- | ||

| 1,4-Benzenediol, 2-methyl- |  |

|

| Ethene, ethoxy- |

3.2. Phytocomponent identification by GC-MS of Methanolic extract of M. Oleifera leaves

The GC-MS profile of the methanolic extract of M. Oleifera leaves is shown in Fig. 2, which reflects 54 peaks of biomolecules. Table 3 presents the phytocomponents, their retention time, peak area percentage and Molecular weight. Chemical structure of active components and their known key applications like medicinal, cosmetics etc. are tabulated in Table 4. Few major compounds found with high percent peak area are 1,3-Propanediol, 2-ethyl-2- (hydroxymethyl)- (21.19%), Propionic acid, 2-methyl-, octyl ester (15.02%), Ethanamine, N-ethyl-N-nitroso- (5.21%), and 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, (Z,Z,Z)- (5.00%) additional compounds with reasonable percentage of peak area are 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- (4.18%), Benzeneacetonitrile, 4-hydroxy- (3.47%), 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone (3.29%), n-Hexadecanoic acid (2.57%) and Monomethyl malonate (2.56%).

Fig. 2.

GC MS of Moringa O. leaves Methanolic extract.

Table 3.

List of phytochemicals identified in methanolic extract of Moringa O. leaves, their retention time and peak area% with molecular weight (grams/mole).

| Sr.No | RT | Peak Area % | Library/ID | Molecular Weight (g/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.66 | 2.4651 | Dihydroxyacetone | 90 |

| 2 | 11.5285 | 1.8656 | Glycerin | 92 |

| 3 | 11.7064 | 0.5327 | Erythritol | 122 |

| 4 | 14.0612 | 2.5684 | Monomethyl malonate | 118 |

| 5 | 15.5626 | 0.6434 | 4,5-Diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine | 126 |

| 6 | 17.8911 | 4.1801 | 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- | 144 |

| 7 | 18.9343 | 0.2105 | Furan, 2,3-dihydro-4-methyl- | 84 |

| 8 | 20.4278 | 0.6806 | Catecholborane | 120 |

| 9 | 20.6515 | 0.8121 | 2-Fluoropyridine | 97 |

| 10 | 21.017 | 1.4375 | 1,2,3-Propanetriol, 1-acetate | 134 |

| 11 | 21.2273 | 0.1746 | 3,4-Furandiol, tetrahydro-, trans- | 104 |

| 12 | 21.4101 | 0.5114 | 1-Nitro-.beta.-d-arabinofuranose, tetraacetate | 363 |

| 13 | 21.5424 | 0.1172 | 1,8-Diamino-3,6-dioxaoctane | 148 |

| 14 | 22.033 | 1.7997 | 1,7-Diaminoheptane | 130 |

| 15 | 22.6606 | 0.454 | N,N-Dimethylacetamide | 131 |

| 16 | 22.8934 | 0.5466 | 2-Oxoglutaric acid | 146 |

| 17 | 23.1495 | 0.9008 | Oxazolidine, 2-ethyl-2-methyl- | 115 |

| 18 | 23.7541 | 0.7112 | Heptanal | 114 |

| 19 | 25.4554 | 0.4293 | 6-Methoxy-3-pyridazinethiol | 142 |

| 20 | 25.6675 | 0.5971 | 3-Piperidinol | 101 |

| 21 | 26.4192 | 21.1909 | 1,3-Propanediol, 2-ethyl-2-(hydroxymethyl)- | 134 |

| 22 | 27.4032 | 3.4763 | Benzeneacetonitrile, 4-hydroxy- | 133 |

| 23 | 27.6817 | 0.395 | Benzenebutanal, .gamma.,4-dimethyl- | 176 |

| 24 | 28.8207 | 0.4491 | 2(4H)-Benzofuranone, 5,6,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,4,7a-trimethyl- | 180 |

| 25 | 30.0026 | 5.2161 | Ethanamine, N-ethyl-N-nitroso- | 102 |

| 26 | 30.3938 | 15.0279 | Propanoic acid, 2-methyl-, octyl ester | 200 |

| 27 | 30.7101 | 3.2947 | 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone | 162 |

| 28 | 31.0768 | 0.3814 | d-Glycero-d-ido-heptose | 210 |

| 29 | 31.1206 | 0.3314 | D-erythro-Pentose, 2-deoxy- | 134 |

| 30 | 32.4351 | 0.5345 | N-Methoxy-1-ribofuranosyl-4-imidazolecarboxylic amide | 273 |

| 31 | 33.2282 | 0.5847 | Formamide, N,N-dimethyl- | 73 |

| 32 | 33.4717 | 0.5651 | d-Talonic acid lactone | 178 |

| 33 | 33.7365 | 0.482 | Sorbitol | 182 |

| 34 | 33.9282 | 0.5189 | Allo-Inositol | 180 |

| 35 | 34.1181 | 1.595 | D-chiro-Inositol, 3-O-(2-amino-4-((carboxyiminomethyl)amino)-2,3,4,6-tetradeoxy-.alpha.-D-arabino-hexopyranosyl)- | 379 |

| 36 | 34.3555 | 1.1254 | Allo-Inositol | 180 |

| 37 | 34.5368 | 1.1121 | Scyllo-Inositol | 180 |

| 38 | 34.7792 | 2.0264 | Muco-Inositol | 180 |

| 39 | 34.8409 | 0.8749 | Allo-Inositol | 180 |

| 40 | 34.8998 | 2.0545 | Inositol | 180 |

| 41 | 35.6364 | 0.4822 | Cyclohexane, 1-methyl-4-(2-hydroxyethyl)- | 142 |

| 42 | 37.3767 | 0.8519 | Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester | 270 |

| 43 | 37.9829 | 2.5703 | n-Hexadecanoic acid | 256 |

| 44 | 38.9185 | 0.3737 | Phenol, 2-methyl- | 108 |

| 45 | 39.2935 | 0.967 | (1S)-Propanol, (2S)-[(tert.butyloxycarbonyl)amino]-1-phenyl- | 251 |

| 46 | 39.7227 | 1.0307 | 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester | 296 |

| 47 | 39.8325 | 0.9664 | Phytol | 296 |

| 48 | 40.0418 | 5.0063 | 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, (Z,Z,Z)- | 278 |

| 49 | 40.2184 | 1.2051 | Octadecanoic acid | 284 |

| 50 | 40.3832 | 0.4257 | 4-Allyl-3-(dimethylhydrazono)-2-methylhexane-2,5-diol | 228 |

| 51 | 40.8886 | 0.6056 | Benzyl .beta.-d-glucoside | 270 |

| 52 | 41.0816 | 0.1698 | 4,6-dimethyl-2-propyl-1,3,5-dithiazinane | 191 |

| 53 | 41.8877 | 0.545 | 1,3-Benzenediol, 2-methyl- | 124 |

| 54 | 42.0626 | 1.4694 | 9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- | 281 |

Table 4.

Phytochemicals in methanolic extract of Moringa O. leaves, their structure from NIST library and known potential applications wherever applicable.

| Ingredients | Structure | Key applications (if any readily known) |

|---|---|---|

| Dihydroxyacetone |  |

Dihydroxyacetone (DHA) are being used in Sunless tanning type of products. (Huang et al., 2017) |

| Glycerin |  |

Used as humectant, Moisturizer having application in cosmetics and Medicines (Sagiv et al., 2001) |

| Erythritol |  |

Antioxidant Improve blood vessel function in people with type 2 diabetes (den Hartog et al., 2010) |

| Monomethyl malonate |  |

|

| 4,5-Diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine |  |

Analogues are used for various Medicinal properties like antimicrobial (Abbas et al., 2017) |

| 4H-Pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- |  |

Strong Anti-oxidant (Yu et al., 2013, Čechovská et al., 2011) |

| Furan, 2,3-dihydro-4-methyl- |  |

|

| Catecholborane |  |

Versatile compound for various organic synthesis (Brown and West, 2001, Paquette et al., 2009) |

| 2-Fluoropyridine |  |

|

| 1,2,3-Propanetriol, 1-acetate |  |

|

| 3,4-Furandiol, tetrahydro-, trans- |  |

|

| 1-Nitro-.beta.-d-arabinofuranose, tetraacetate |  |

|

| 1,8-Diamino-3,6-dioxaoctane | ||

| 1,7-Diaminoheptane |  |

Malaria treatment (Kaiser et al., 2001) |

| N,N-Dimethylacetamide |  |

Novel antiviral agent (He et al., 2005) |

| 2-Oxoglutaric acid |  |

Biosynthesis of Carotenoids in Chloroplasts (Liu et al., 2018) |

| Oxazolidine, 2-ethyl-2-methyl- |  |

|

| Heptanal | ||

| 6-Methoxy-3-pyridazinethiol |  |

|

| 3-Piperidinol |  |

Anti-tuberculosis agent (Markad et al., 2015) |

| 1,3-Propanediol, 2-ethyl-2-(hydroxymethyl)- |  |

|

| Benzeneacetonitrile, 4-hydroxy- |  |

|

| Benzenebutanal, .gamma.,4-dimethyl- |  |

|

| 2(4H)-Benzofuranone, 5,6,7,7a-tetrahydro-4,4,7a-trimethyl- |  |

Anti‑arthritic activity (Rhew et al., 2020) |

| Ethanamine, N-ethyl-N-nitroso- |  |

Boost immune system. (Zaitseva et al., 2018) |

| Propanoic acid, 2-methyl-, octyl ester |  |

Anti-Microbial properties (Hamedi et al., 2019) |

| 3-Deoxy-d-mannoic lactone |  |

|

| d-Glycero-d-ido-heptose |  |

Inhibition of insulin secretion & Hexokinase (Scruel et al., 1998) |

| D-erythro-Pentose, 2-deoxy- |  |

|

| N-Methoxy-1-ribofuranosyl-4-imidazolecarboxylic amide |  |

|

| Formamide, N,N-dimethyl- |  |

|

| d-Talonic acid lactone |  |

|

| Sorbitol |  |

Help to prevent hyperglycemia (Wick et al., 1951) Protect and rejuvenation of skin from oxidative stress (Manca et al., 2018) |

| Allo-Inositol |  |

Control the il6 level to reduce the inflammation (Bizzarri et al., 2020) |

| D-chiro-Inositol, 3-O-(2-amino-4-((carboxyiminomethyl)amino)-2,3,4,6-tetradeoxy-.alpha.-D-arabino-hexopyranosyl)- |  |

Type 2 Diabetes Treatment (Pintaudi et al., 2016) |

| Allo-Inositol |  |

Control the il6 level to reduce the inflammation (Bizzarri et al., 2020) |

| Scyllo-Inositol |  |

Treat mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. (Choi et al., 2010) |

| Muco-Inositol |  |

Oligomer of muco-inositol act as glycosidase inhibitors (Freeman and Hudlicky, 2004) |

| Allo-Inositol |  |

Control the il6 level to reduce the inflammation (Bizzarri et al., 2020) |

| Inositol |  |

Inositol and its derivative are known for treatment of Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) (Kamenov and Gateva,, Mariano and Gianfranco, 2014) |

| Cyclohexane, 1-methyl-4-(2-hydroxyethyl)- |  |

|

| Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester |  |

Anti-inflammatory (Saeed et al., 2012) |

| n-Hexadecanoic acid (palmitic acid) |  |

Anti-inflammatory (Aparna et al., 2012) |

| Phenol, 2-methyl- |  |

|

| (1S)-Propanol, (2S)-[(tert.butyloxycarbonyl)amino]-1-phenyl- |  |

Human Immunodeficiency virus -1 (HIV-1) Protease Inhibitors (Ghosh et al., 2015) |

| 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester |  |

Lubricant (Faujdar and Singh, 2021) |

| Phytol | Control Ganoderma boninense (Plant disease) (ABDUL AZIZ,) Antioxidant, Anti-inflammatory (Islam et al., 2018) |

|

| 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, (Z,Z,Z)- |  |

Reduce complications in Covid-19 patients. (Weill et al., 2020) Neuroprotective Properties. (Blondeau et al., 2015) |

| Octadecanoic acid |  |

Play role in food reward (Li et al., 2020) Lowers High density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (van Rooijen et al., 2021) |

| 4-Allyl-3-(dimethylhydrazono)-2-methylhexane-2,5-diol |  |

|

| Benzyl .beta.-d-glucoside |  |

|

| 4,6-dimethyl-2-propyl-1,3,5-dithiazinane |  |

|

| 1,3-Benzenediol, 2-methyl- |  |

|

| 9-Octadecenamide, (Z)- |  |

Anti-depressive effects (Ge et al., 2015) |

3.3. Free radical scavenging efficacy of aqueous and Methanolic extracts of M. Oleifera leaves at varying concentrations:

The aqueous extract of Moringa leaves have the IC50 at concentration of 4.65 µl/ml after incubating for 30 min Fig. 3 whereas the IC50 of Methanolic extract was found 1.83 µl/ml Fig. 4 which is significantly lower than the IC50 of Moringa aqueous extract. Various concentrations (1 µl/ml to 5 µl/ml) of Moringa aqueous and Methanolic extracts were also evaluated and compared at the defined interval of incubation time up to 160 min to identify the maximum FRSP for each concentration and the results are showcased in Fig. 5.

Fig. 3.

IC50 of Moringa O. leaves aqueous extract.

Fig. 4.

IC50 of Moringa O. leaves Methanolic extract.

Fig. 5.

Free radical scavenging potency (FRSP) comparison of Aqueous and Methanolic extract of varying concentration at various incubation time points.

4. Discussion

This study is among the very few reports where the phytochemical profile of Moringa extracts with their free radical scavenging potency studies have been reported. In this study, higher number of phytochemicals in methanolic extract (Table 3) of Moringa extract in comparison to aqueous (Table 1) could be due to difference in their polarity, which could have led to difference in the extraction of phytochemicals. These, phytochemicals have various industrial applications and medicinal properties like anti-tumor, anti-cancer, Insulin regulation, anti-oxidant etc. which makes it really a magical plant for food, medicine and suitable natural ingredient to explore its further applications in diverse areas like in cosmetics, personal care products etc.

Natural antioxidants are always of very high importance for health as a part of food and as a part of cosmetics for topical applications to combat the detrimental affects of free radicals on internal and external organs like skin aging etc. Both aqueous and methanolic Moringa extracts have excellent anti-oxidant/FRSP. However, in relative terms Methanolic extract found to have lower IC50 (1.83 µl/ml) Fig. 4 reflecting higher free radical scavenging ability in comparison to of aqueous extract having higher IC50 (4.65 µl/ml) Fig. 3. This could be mainly due to higher number of polyphenolic component extracted in Methanolic extracts and relatively at higher percentages, which is contributing towards higher scavenging potency at lower concentration. It has been found that Methanolic extract at 5 µl/ml gives the 88.5% FRSP and does not change significantly over the period of time and reaches maximum level of 92.8% FRSP. Whereas aqueous extract at 5 µl/ml show 35.8% FRSP at the initial time point and which further scavenge the DPPH free radical significantly up to 68.4% in 160 min Fig. 6, however still less FRSP of Moringa Aqueous extract than the Methanolic extract could be due to the same reason as explained above of having more polyphenolic components in Methanolic extract of Moringa as reflected in GC-MS results.

Fig. 6.

Free radical scavenging potency (FRSP) comparison of Aqueous and Methanolic extract of 5 µl/ml concentration at various incubation time points.

5. Conclusions

This study has investigated the Moringa aqueous extract and identified twenty-five phytochemicals and similarly in Methanolic extract fifty-four phytochemical components were identified. The higher number of these constituents in methanol may be due to polarity difference, which contributed to solubilize the various molecules. Few of phytochemicals reported here are rarely detected in plant extracts like 3,3′-Iminobispropylamine, Butanedioic acid, 2-hydroxy-2-methyl- etc. and have potential applications. In further studies these extracts have shown substantial free radical scavenging potency, IC50 of Moringa aqueous extract observed is 4.65 µl/ml and for methanolic extract 1.83 µl/ml. Also, found that Methanolic extract at 5 µl gives the 88.5% FRSP at initial time point and does not change significantly over the period of time and reaches maximum level of 92.8% FRSP. Whereas aqueous extract at 5 µl show 35.8% FRSP at the initial time point and which further scavenge the DPPH free radical significantly up to 68.4% in 160 min. These high FRSP make them very suitable ingredients for various applications like food, animal feed medicines, cosmetic etc. We are in the process of establishing the same in products of topical application to have skin benefits like prevention of skin damage, aging etc.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

Authors are highly thankful to IFFCO group, UAE, especially Mr. Isa Allana, Managing director (MD), Serhad C. Kelemci, Chief executive officer (CEO), Mr. Sunil Singh, Technical director and NIT-Warangal’s director for their encouragement and continuous support for this study.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of King Saud University.

References

- Abbas A. A. Z., Abu-Mejdad N. M. J., Atwan W. Z., Al-Masoudi A. N., 2016. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of New Dipyridylpteridines, Lumazines, and Related Analogues. J. Heterocyclic Chem., HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1002/jhet.2651.

- Syamimi D.A.A., 2019. Phytol-Containing Seaweed Extracts as Control for Ganoderma boninense. J.O.P.R. 31(2), 238-247. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.21894/jopr.2019.0018.

- Ageel A.M., Parmar N.S., Mossa J.S., Al-Yahya M.A., Al-Said M.S., Tariq M. Anti-inflammatory activity of some Saudi Arabian medicinal plants. Agents Actions. 1986;17(3-4):383–384. doi: 10.1007/BF01982656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ziaydi A.G., Imran M., Al-Shammari A.M., Kadhim H.S., Jabir M., 2020. The anti-proliferative activity of D-Mannoheptulose against breast cancer cell line through glycolysis inhibition AIP Conference Proceedings 2307, 020023. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/ 10.1063/5.0032958.

- Aparna V., Vijayan D., Mandal P., Karthe P., 2012. Anti-Inflammatory Property of n-Hexadecanoic Acid: Structural Evidence and Kinetic Assessment. J. Chem. Bio. D. D. 80(3), 434-9. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bizzarri M., Laganà A.S., Aragona D., Unfer V., 2020. Inositol and pulmonary function. Could myo-inositol treatment downregulate inflammation and cytokine release syndrome in SARS-CoV-2? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 24 (6): 3426-3432 HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.26355/eurrev_202003_20715. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blondeau, N., Lipsky, R.H., Bourourou, M., Duncan, M.W., Philip, 2015. Alpha-Linolenic Acid: An Omega-3 Fatty Acid with Neuroprotective Properties—Ready for Use in the Stroke Clinic? HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1155/2015/519830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Brown H. C., West Lafayette W., 2001. Economical and Convenient Procedures for The Synthesis of Catecholborane. Patent No.: US 6,204,405 B1.

- Cancelas J., Acitores A., Penacarrillo M.L.V., Malaisse W.J., Valverde I. Activation of glycogen synthase a in hepatocytes exposed to alpha-D-glucose pentaacetate. I. J. Mol. Med. 2000;6(2):197–199. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.6.2.197. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.3892/ijmm.6.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Čechovská L., Cejpek K., Konečný M., Velíšek J. On the role of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-(4H)-pyran-4-one in antioxidant capacity of prunes. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2011;233(3):367–376. [Google Scholar]

- Choi J.-K., Carreras I., Dedeoglu A., Jenkins B.G. Detection of increased scyllo-inositol in brain with magnetic resonance spectroscopy after dietary supplementation in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models. J. Neuropharm. 2010;59(4-5):353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois P., Sener A., Malaisse W.J. D-mannoheptulose phosphorylation by hexokinase isoenzymes. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2001;7:359–363. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.7.4.359. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.3892/ijmm.7.4.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gertjan J.M., Den Hartog, Agnes Boots W., Aline Adam-Perrot, Fred Brouns, Inge W.C.M Verkooijen, Antje R.Weseler, Guido R.M.M Haenen, Aalt Bast, 2010 Erythritol is a sweet antioxidant. PubMed, Nutrition 26(4), 449-58. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.nut.2009.05.004. pub 2009 Jul 24. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Faujdar E., Singh R.K. Methyl oleate derived multifunctional additive for polyol based lubricants. Wear. 2021;466-467:203550. doi: 10.1016/j.wear.2020.203550. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, S., Hudlicky, T., 2004. New oligomers of conduritol-F and muco-inositol. Synthesis and biological evaluation as glycosidase inhibitors. J. BMCL. 14(5).1209-12. HTTPS://DOI.ORG//10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.12.050. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gamal E.E.G., Khalifa S.A.K., Gameel A.S., Emad M.A. Traditional medicinal plants indigenous to Al-Rass province, Saudi Arabia. J. Med. Plants Res. 2010;4(24):2680–2683. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, L., Zhu, M.M., Yang, J.Y., Wang, F., Zhang, R., Zhang, J.H., Shen, J., Tian, H.F., Wu, C.F., 2015. Differential proteomic analysis of the anti-depressive effects of oleamide in a rat chronic mild stress model of depression. J.PBB. vol.131, 77-86. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.pbb.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A..K, Yu, X., Osswald, H.L., Agniswamy, J., Wang, Y.F., Amano, M., Weber, I.T., Mitsuya, H., 2015. Structure-based design of potent HIV-1 protease inhibitors with modified P1-biphenyl ligands: synthesis, biological evaluation, and enzyme-inhibitor X-ray structural studies. J Med Chem. 2015 Jul 9;58(13):5334-43. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b00676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Hagiyama K., Suzuki K., Ohtake M., Shimada M., Nanbu N., Takehara M., Ue M., Sasaki Y. Physical properties of substituted 1,3-dioxolan-2-ones. Chem. Let. 2008;37(2):210–211. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1246/cl.2008.210. [Google Scholar]

- Hamedi A., Lashgari A.P., Pasdaran A. 2019 Antimicrobial Activity and Analysis of the Essential Oils of Selected Endemic Edible Apiaceae Plants Root from Caspian Hyrcanian Region (North of Iran) Pharm Sci. 2019;25(2):138–144. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.15171/PS.2019.21. [Google Scholar]

- He Y., Johnson J. L. H., Yalkowsky S. H., 2005. Oral formulation of a novel antiviral agent, PG301029, in a mixture of Gelucire 44/14 and DMA (2:1, wt/wt). AAPS PharmSciTech 6, E1–E5 (2005). HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1208/pt060101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Huang, A., Neil Brody, Liebman Tracey N, 2017. Dihydroxyacetone and sunless tanning: knowledge, myths, and current understanding. J. of the A. Acad. of Dermat. Vol-77, I-5, 991-992. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.jaad.2017.04.1117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Imad H.H., Hussein J.H., Muhanned A.K., Nidaa S.H. Identification of five newly described bioactive chemical compounds in methanolic extract of Mentha viridis by using gas chromatography – mass spectrometry (GC-MS) J. Pharmacognosy Phytother. 2015;7(7):107–125. [Google Scholar]

- Islam M.T., Ali E.S., Uddin S.J., Shaw S., Islam M.A., Ahmed M.I., Chandra Shill M., Karmakar U.K., Yarla N.S., Khan I.N., Billah M.M., Pieczynska M.D., Zengin G., Malainer C., Nicoletti F., Gulei D., Berindan-Neagoe I., Apostolov A., Banach M., Yeung A.W.K., El-Demerdash A., Xiao J., Dey P., Yele S., Jóźwik A., Strzałkowska N., Marchewka J., Rengasamy K.R.R., Horbańczuk J., Kamal M.A., Mubarak M.S., Mishra S.K., Shilpi J.A., Atanasov A.G. Phytol: A review of biomedical activities. F. Chem. T. 2018;121:82–94. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2018.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser A., Gottwald A., Wiersch C., 2001. Effect of drugs inhibiting spermidine biosynthesis and metabolism on the in vitro development of Plasmodium falciparum. Parasitol Res 87, 963–972 (2001). HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1007/s004360100460. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zdravko, K., Antoaneta, T.G., 2020. Inositols in PCOS Molecules 25(23):5566 HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.3390/molecules25235566.

- Kanhar S., Sahoo A.K. Ameliorative effect of Homalium zeylanicum against carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative stress and liver injury in rats. J. biopha. 2018;111:305–314. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.045. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khorassani R., Hettwer U., Ratzinger A., Steingrobe B., Karlovsky P., Claassen N. Citramalic acid and salicylic acid in sugar beetroot exudates solubilize soil phosphorus. BMC Plant Bio. 2011;11(1):121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-11-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leone A., Spada A., Battezzati A., Schiraldi A., Aristil J., Bertoli S. Cultivation, genetic, ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and pharmacology of Moringa oleifera leaves: an overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015;16:12791–12835. doi: 10.3390/ijms160612791. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.3390/ijms160612791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y., Wu, H., Zhang, R., Shu, G., Wang, S., Gao, P., Zhu, X., Jiang, Q., Wang, L., 2020. Diet containing stearic acid increases food reward-related behaviors in mice compared with oleic acid. J.brainresbull.vol.164, 45-54. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Liu S., He L., Yao K. The antioxidative function of alpha-ketoglutarate and its applications. Bio Med R.I. 2018;2018:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2018/3408467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manca M.L., Palomo S.M., Caddeo C., Nacher A., Sales O.D., Peris J.E., Pedraz J.L., Fadda A.M., Manconi M. Sorbitol-penetration enhancer containing vesicles loaded with baicalin for the protection and regeneration of skin injured by oxidative stress and UV radiation. J. ijpharm. 2018;555:175–183. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.053. HTTPS://DOI.ORG /10.1016/j.ijpharm.2018.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariano B., Gianfranco C. Inositol: history of an effective therapy for polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;18:1896–1903. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markad, S.D., Kaur, P., Kishore Reddy, B.K. 2015. Novel lead generation of an anti-tuberculosis agent active against non-replicating mycobacteria: exploring hybridization of pyrazinamide with multiple fragments. Med Chem Res 24, 2986–2992 (2015). HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1007/s00044-015-1352-6.

- Nishio T., Yoshikawa Y., Shew C.Y., Umezawa N., Higuschi T., Yoshikawa K. Specific effects of antitumor active norspermidine on the structure and function of DNA. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:14971. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-50943-1. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1038/s41598-019-50943-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ölgena S., Altanlarb N., Karataylıc E., Bozdayıc M. Antimicrobial and antiviral screening of novel indole carboxamide and propanamide derivatives. Z. Naturforsch. 2008;63c:189–195. doi: 10.1515/znc-2008-3-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paliwal P., Sargolzaei S., Bhardwaj K.S., Bhardwaj V., Dixit C., Kaushik A. Grand challenges in bio-nanotechnology to manage the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Nanotechnol. 2020;2 HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.3389/fnano.2020.571284. [Google Scholar]

- Paquette L.A., Crich D., Fuchs P.L., Molander G.A. Encyclopedia of reagents for organic synthesis. Wiley, New York. 2009;2:1017. [Google Scholar]

- Pintaudi B., Di Vieste G., Bonomo M. The Effectiveness of Myo-Inositol and D-Chiro Inositol Treatment in Type 2 Diabetes. I. J Endocrinology. 2016;2016:1–5. doi: 10.1155/2016/9132052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purena R., Seth R., Bhatt R. Protective role of Emblica officinalis hydro-ethanolic leaf extract in cisplatin induced nephrotoxicity in Rats. Tox. Rep. 2018;5:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.01.008. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhew, ZI., Lee, J.H. & Han, Y. 2020. Aster yomena has anti-arthritic activity against septic arthritis induced by Candida albicans: its terpenoid constituent is the most effective and has synergy with indomethacin. ADV TRADIT MED (ADTM) 20, 213–221 (2020). HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1007/s13596-019-00405-w.

- Rodriguez-Garay B., Phillips G.C., Kuehn G.D. Detection of norspermidine and norspermine in Medicago sativa L. (Alfalfa) Plant Physiol. 1989;89(2):525–529. doi: 10.1104/pp.89.2.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed N.M., Demerdashb E. E., Abdel-Rahmana H.M., Algandabyc M. M., Al-Abbasid F. A., Abdel-Naim A. B., 2012. Anti-inflammatory activity of methyl palmitate and ethyl palmitate in different experimental rat models.J. TAAP. 264(1), 84-93. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.taap.2012.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sagiv A.E., Dikstein S., Ingber A., 2001 Feb. The efficiency of humectants as skin moisturizers in the presence of oil. PubMed, S.R&T, 7(1), 32-5. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1034/j.1600-0846.2001.007001032.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scruel, O., Vanhoutte, C., Sener, A., 1998. Interference of D-mannoheptulose with D-glucose phosphorylation, metabolism and functional effects: Comparison between liver, parotid cells and pancreatic islets. Mol Cell Biochem 187, 113–120 (1998). HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1023/A:1006812300200. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Shendurse A.M., Khedkar C.D. Encyclopedia of Food and Health. Elsevier; 2016. pp. 239–247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui N., Azad B., Alam M.S., Ali R. Indoles: role in diverse biological activities. IJPCR. 2010;2(4):121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Skoweranda J., Bukowska-Strzyzewska M., Bartnik R., Strzyżewski W. Molecular structure and some reactivity aspects of 2,6-diamino-4(3H)-pyrimidinone monohydrate. J. Chem. Cryst. 1990;20(2):117–121. [Google Scholar]

- Starostin K.E., Lapitskaya A.M., Ignatenko V.A., Pivnitsky K.K., Nikishin L.G. Practical synthesis of hex-5-ynoic acid from cyelohexanone. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2000;49:81–84. [Google Scholar]

- Sunkara S.P., Zwolshen H.J., Prakash J.N., Bowlin L.T. Progress in Polyamine Research. Plenum Press; New York: 1988. Mechanism of Antitumor activity of Norspermidine, a structural homologue of Spermidine; pp. 707–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takebe Y., Iuchi K., Tsukamoto G., 1984. 4-Chloro-4-Methyl-5-Methylene-1,3-Dioxolan-2-One. Patent EP0147472 B1.

- Ullah R., Alqahtani S.A., Noman M.A.O., Alqahtani M.A., Ibenmoussa S., Bourhia M. A review on ethno-medicinal plants used in traditional medicine in the Kindgdom of Saudi Arabia. S. J. Bio. Sci. 2020;27:2706–2718. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.06.020. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rooijen, M.A.V, Plat, J., Blom, W.A.M., Zock, P.L. Mensink, R.P., 2020. Dietary stearic acid and palmitic acid do not differently affect ABCA1-mediated cholesterol efflux capacity in healthy men and postmenopausal women: A randomized controlled trial. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.clnu.2020.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Varahachalam S.P., Lahooti B., Chamaneh M., Bagchi S., Chhibber T., Morris K., Bolanos F.J., Kim Y.N., Kaushik A. Nanomedicine for the SARS-CoV-2: state-of-the- art and future prospects. Int. J. Nanomed. 2021;16:539–560. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S283686. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.2147/IJN.S283686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weill P., Plissonneau C., Legrand P., Rioux V., Thibault R. May omega-3 fatty acid dietary supplementation help reduce severe complications in Covid-19 patients? J. Biochi. 2020;179:275–280. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2020.09.003. HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1016/j.biochi.2020.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arne N., Wick, Mary C., Almen, Lionel Joseph., 2016. The Metabolism of Sorbitol., jps. Volume 40, Issue 11, November 1951, Pages 542-544. HTTPS://DOI.ORG10.1002/jps.3030401104. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Yu X., Zhao M., Liu F., Zeng S., Hu J. Identification of 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl-4H-pyran-4-one as a strong antioxidant in glucose–histidine Maillard reaction products. Food res. Int. 2013;51(1):397–403. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitseva, N.V., Ulanova, T.S., Dolgikh, O.V., 2018. Diagnostics of Early Changes in the Immune System Due to Low Concentration of N-Nitrosamines in the Blood. Bull Exp Biol Med 164, 334–338 (2018). HTTPS://DOI.ORG/10.1007/s10517-018-3984-2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zelikin A.N., Putnam D. Poly(carbonate-acetal)s from the dimer form of dihydroxyacetone. Macromolecules. 2005;38(13):5532–5537. [Google Scholar]