Abstract

The demand of online remote working from home significantly increased in 2020/21 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. This unforeseen situation has forced individuals and organisations to rapidly train employees and adopt the use of on-line working styles, seeking to maintain the same level of productivity as working from the office. The paper outlines a survey conducted amongst people working from home to identify the challenges and opportunities this change in workstyle offers. At the beginning of the pandemic, many employees faced difficulties adapting to using online tools and combining their working hours with daily routines and family commitments. However, the results show that within a short period of time the respondents had managed to develop the necessary experience and knowledge for digital working utilising tools such as collaboration platforms and video conferencing. A large proportion of respondents recognised the advantage of eliminating travelling time when working remotely from home which also has a positive impact on the environment and CO2 emissions. However, some drawbacks have been identified such as the lack of face-to-face discussion and informal meetings during working days. The Self-Determination Theory is discussed within the context of this paper and it has been found that the theory could provide an explanation of the efficient and rapid adaptation of the technology be employees.

Keywords: Covid-19, Coronavirus, Lockdown, Working from home, Digital technology, On-line, Conferencing

1. Introduction

By the end of March 2020, governments worldwide had decided to take measures to restrict the movement of their population in order to reduce the spread of Covid-19 and maintain or reduce the R-number below 1, where R is the average number of people that one infected person will pass on the virus to. These lockdowns lead to the temporary closure of ‘non-essential’ businesses and forced millions of people worldwide to work from home. In many countries, facilities such as schools, nurseries, universities, commercial organisations, dental clinics, and social venues including restaurants and coffee shops were closed [1]. This lockdown has forced millions of workers to embrace remote working when possible to do so and made working from home a must rather than an option.

Carroll and Conboy [2] highlighted the fact that COVID-19 forced organisations into rapid ‘big bang’ sudden adoption of online working from home practices; they draw on the normalisation process theory (NPT) and its underlying components which can be used to understand the dynamics of implementing, embedding, and integrating new technologies and practices into businesses. Matli [3] presented the results of a survey with main findings indicating that despite the positive characteristics of remote working using on-line technology, there are many negative aspects and risks related to working from home such as unbalanced work overload and pressures to perform timeously, which could affect health and wellbeing due to stress-related issues.

Richter [4] discussed the implication of the lockdown on digital-work tools for research and practice, illustrating how the lockdown acted as a facilitator for online working. Also, he indicated how the lockdown had a significant impact on people's lives and work practices. However, many employees struggled due to variety of reasons, such as time management and having to work around childcare commitments (when the schools are closed). Other factors also play an important role, such as the need to share computer facilities and internet access at home with other family members, in addition to increased stress from the increase in daily videoconferences. According to Scheiber [5] Covid-19 pandemic has significantly increased the flexibility of the working hours but has also negatively influenced daily work patterns.

According to Cho [6]; Covid-19 had a significant impact on the workforce and careers on a global level and it has affected many individuals' vocational behaviours and productivity outcomes. Research conducted on working from home prior to the Covid-19 pandemic found similar difficulties. For example, the work of Park, Fritz and Jex [7] confirmed that working from home has many drawbacks and may create disruptions, especially amongst those who prefer to working in an office environment and have family commitments and duties. Prior to Covid19, some researchers discussed the advantages and issues in relation to working from home [[8], [9], [10], [11], [12]]. The difference between working from home before and after the Covid-19 pandemic is that previously it was an optional measure, but due to Covid-19 it has become a necessity within a very short period of time. Nevertheless, even after Covid-19 restrictions, some organisations have decided to permit or even require their employees to work from home indefinitely. Kramer & Kramer [13] identified key aspects that are missing from the working from home culture, such as informal face-to-face meetings, the enjoyment of travel and breaking the routine of staying in one place.

Spurka and Straubb [14] discussed the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on work and careers of individuals within flexible employment relationships; outlining potential impacts of Covid-19 pandemic on the careers of those employees and examining how the pandemic could contribute to the ramification of flexible employment relationships. According to Davison [15]; the lockdown has required most office workers to fully embrace online remote working and digital work tools such as collaboration platforms and video conferencing tools to enable them to work 100% remotely in new innovative ways. Some recent research has indicated that the lockdown has been found to help specifically in reducing travel and pollution levels with potential positive impacts on global warming and climate change [16]. According to Richter [17]; the lockdown has allowed many employees to connect and meet in new ways; and to work more flexibly establishing new forms of management and independent working styles. This has driven many employers to develop their organisational and data management frameworks by using online tools to access resources and data. At the same time, the data security protections requirement has increased significantly during Covid-19 lockdown. A recent study by Ivanti [18] has found that IT security demands have increased by 66% due to online remote working, with the majority of on-line issues coming from, malicious emails, non-compliant employee behaviour, and software vulnerabilities.

The widely available internet infrastructure and software availability has helped organisations adapt to new working styles, which would have been much more difficult in previous decades [17]. Modern software, employee's ICT awareness and recent organisational practices have shown inherent flexibility and openness, supporting a wide variety of work practices without the need for technical customisation [19]. However, it has been argued that if working from home becomes more permanent, organisations will need more sophisticated organisational measures and software to replicate, as far as possible, the ‘in-office’ experience.

Recent publications have also presented significant analysis of Covid19 pandemic and its effect on a wide range of technologies and social aspects. Brem et al. [20], have discussed the implications of Covid-19 pandemic on innovation, with reflections on several areas that have seen a vast advancement in a short period of time such as e-learning, 3D printing, flexible manufacturing, big data analysis, healthcare technologies, cashless payment and e-commerce. George et al. [21], have discussed the Covid-19 pandemic on the technology and innovation management research agenda and it has been concluded that the pandemic has changed the way we live and work. Since innovation requires collaboration and communication, their work discussed the effect of the pandemic on innovation when face-to-face meetings are replaced by on-line communication and the challenges of visualisation of innovation and collaboration. The paper highlights the need for further research to better understand the longer term implications of the pandemic on business management. Lee and Trimi [22] have discussed innovation and the digital age in the Covid-19 pandemic. They have concluded that organisations should depend on their innovation capabilities for survival as sustainable innovation has become key strategy for all types of organisations. Guggenberger et al. [23], have discussed internet of things (IOT), artificial intelligence (AI) and distributed ledger technology (DLT) to tackle pandemic related challenges; and have presented an overview of the huge potential that can be achieved from these three technologies when utilised in the right way, particularly with the use of open innovation. Giones et al. [24], have revised the entrepreneurial action in response to Covid-19 pandemic. It has outlined the needed consideration, on individual and organisational levels, that contributes to enhanced resilience. The paper also highlights the need for emotional support to entrepreneurs, during the pandemic and beyond by expanding on the disaster management framework [25]. Ting et al. [26], have highlighted the importance of innovation in the medical sector as the world continues to depend on classic public-health measures for dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic; as a wide range of digital technologies can be utilised now to improve the public-health sector and reduce the risk for patients and medical staff, now and beyond Covid-19 pandemic. Arribas-Ibar et al. [27], discussed the electric vehicles (EVs) sector and its ecosystem; they have argued the possibility that EV ecosystem would be able to benefit from the opportunity provided by the unforseen disruption created by the pandemic.

1.1. The Self-Determination Theory

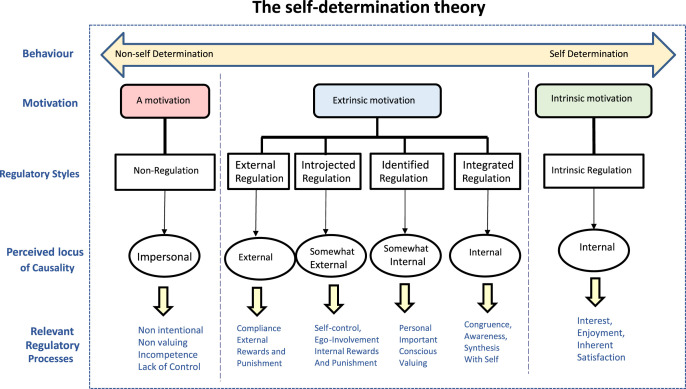

One of the key theories that needs some attention which could explain the reason why people have adapted very quickly to changes and the use on-line systems during the Covid-19 pandemic is the Self-Determination Theory, shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

The self-determination theory, reproduced from Ref. [28].

The theory of self-determination [28,29] can offer insights into how employees have been encouraged to embrace the new working style from home and excel in a short period of time. The self-determination theory suggests that individuals are either intrinsically or extrinsically motivated to behave in specific ways [30]. Intrinsic motivation becomes the dominant driver when an individual wants to perform a certain act for the internal and personal reward or benefit associated with that act [30] such as in this occasion, maintaining their personal satisfaction and sense of achievement. Extrinsic motivation, however, is related to the desire to perform a specific act for the sake of an external reward or penalty [31,32]. Thus, extrinsic motivation within the parameters of self-determination theory might explain why most employees seek to adopt their work practice from home due to economic persuasion, i.e. keeping their job. Or perhaps for them to feel part of the ‘team’ by working closely with colleagues on-line and even becoming more active in relation to that.

2. Method and hypotheses

An online survey was created at the outset of the UK Covid-19 lockdown and shared online via LinkedIn, Reddit community groups and via direct email. A mixture of multiple-choice quantitative questions and open text qualitative questions were posed. This subsequently set a minimum requirement of access to and a basic familiarisation with online tools and platforms as a pre-requirement for completion. The survey went live 3 weeks after the commencement of the UK lockdown and remained live for a month at which point the data was extracted. Therefore the survey reports on the respondent's early experience and initial familiarisation with home online working and this is consistent with the dates that most changes in remote working occurred in early April according to a related study [33].

The survey consists of exploratory research, which sought to gain insights into the respondent's adoption and familiarisation to remote methods of working. Three key hypotheses were explored as outlined below:

Hypothesis 1

There is a relationship between the adaptability to working from home with age [33], highest education level, prior experience of homeworking, device capability, speed of internet connection, software features.

Hypothesis 2

There is a relationship between the adaptability of working from home with related challenges including distractions (childcare, snacking, checking news frequently, risk of redundancy), lack of resources (poor internet, lack of access to necessary documents, lack of printing facilities, lack of suitable space at home, lack of lab facilities, lack of opportunity to be on site to do technical work) and wellbeing concerns (lack of face to face communication, being lonely, lack of physical exercise).

Hypothesis 3

External and home related challenges (such as childcare, poor internet reliability or speed, unhealthy snacking, lack of access to necessary documents, lack of printing facilities, lack of discipline in respect work or family, a lack of informal discussions, a lack of IT support, a lack of suitable space at home, being lonely, checking news frequently, lack of face to face communication, lack of lab facilities, risk of redundancy, lack of physical exercise, lack of opportunity to be on site to get technical work) will result in less enjoyment of home working.

Data was collected from an online survey that was shared across a wide range of online platforms chosen to represent a representative sample including LinkedIn, Reddit UK regional community groups and direct email invitations. The survey was live for a month and was launched 3 weeks into the UK wide lockdown and so reports on early experiences of the transition to working from home.

2.1. Participants

A total of N = 212 respondents completed the survey, representing a 50.5%–49.5% male/female split. Most respondents were UK residents (77.8%), with some responses from other countries (non-UK respondents 22.2%). Although the focus was on the UK, the international participants have provided a wider angle of analysis. This international breakdown was a result of using international forums such as LinkedIn.

The age of respondents was varied but typically within the working age group. The largest group was aged 25–34 (41%), followed by 35–44 (23.16%), 45–54 (17.9%), 18–24 (11.8%) and 55–65 (5.7%). The higher number of respondents aged mid 20's to 40's could partly explain while why childcare issues were so strongly noted as issues relating to home working. As UK schools, pre-schools and nurseries were shut for all children except those of key workers during the time the survey was open. This correlates with the average age of parenthood in England and Wales is 30.4 years for women and 33.3 years for men [34].

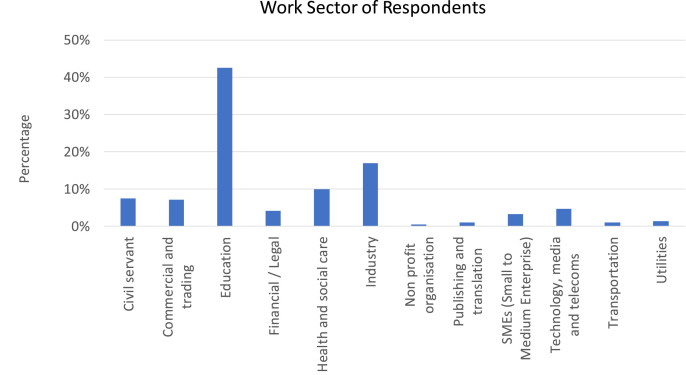

The employment status breakdown of respondents was full time (81.6%), part time (7.1%), self-employment (2.8%) and studying (8.5%). Only economically active respondents are selected and so job seekers or the unemployed were not considered in this survey. Respondents were required to be in a role that permitted working from home for the purposes of the survey and this therefore precluded numerous roles which couldn't be conducted from home. Further to this the survey required completion by those still working throughout the UK lockdown precluding those furloughed due to being in roles that were not financially viable during COVID restrictions and were therefore supported under the financial support measures put in by the UK government, which mirrored those of European neighbours. It is therefore recognised that the demographic data is therefore strongly skewed towards types of employment that was both practically and financially permissible during this period. In this respect the sectors represented by the survey were strongly represented by those in employed in Education (42.5%), Industry (17%), Health and Social Care (9.9%), Civil Service (7.5%) and Commercial and Trading (7.1%), with others at less than 5% as shown in Fig. 2 . Therefore, the demographics had a high percentage of respondents with graduate (28.8%) and postgraduate (49%) qualifications.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of respondents by work sector.

2.2. Measures

Respondents were asked a range of questions pertaining to their working at home experience both prior to and during the Covid-19 pandemic. A total of 22 questions were asked, the first 6 being demographic followed by 15 multiple choice questions each including an ‘other’ option for an open response to capture any additional responses, 11 of these accepted only a single response, whilst four questions permitted multiple response options these questions related to the type of software used, the reasons for the use of the software and the main challenges of working from home and the main benefits. All these questions were reported and analysed as quantitative research, with the key findings reported for each individual question and further statistical analysis employed to permit inferential analysis across a range of questions to test the five key hypotheses.

The final questions were optional and permitted respondents in an open-ended text-based response at the end for any further comments or feelings in relation to homeworking because of COVID. These was analysed qualitatively using thematic analysis to capture key insights that will be discussed separately at the end of the findings section.

3. Results

The reporting of these results will be split into the representative quantitative results from each question, the qualitative open response question, and the inferential analysis results from comparing across question types to determine responses more specifically to the research questions.

3.1. Individual question responses

Prior to the COVID pandemic just over half (55.7%) of the respondents had experience of home or remote working compared to 45.3% who didn't. However when asked about their prior experience of using on-line conferencing from home it was 45.7% having experience, always (4.2%), frequently (16%), sometimes (25.5%), compared to 24.1% who had never and 30.2% who had rarely ever used on-line conferencing from home. This suggests that whilst working from home was occurring previously, the type of work that was typically conducted did not require engagement with others. Conversely when asking the same question regarding online conferencing at home but during the Covid-19 restrictions the responses indicated that 51.4% always, 28.8% frequently and 11.8% sometimes use online conferencing at home compared to only 5.7% that rarely or 2.4% that never use it. This suggests that it is not just the location of work, but the type and function of work that has changed significantly as well.

When asked whether they thought that working online from home would achieve the same outcomes as working onsite, 83% overall felt it did with the breakdown being 13.7% for always, 41.5% for often and 27.8% for sometimes achieving the same outcomes, 2.4% didn't know and the remaining was split between rarely or never. This indicates that the general consensus was that the respondents felt that it would be feasible to continue.

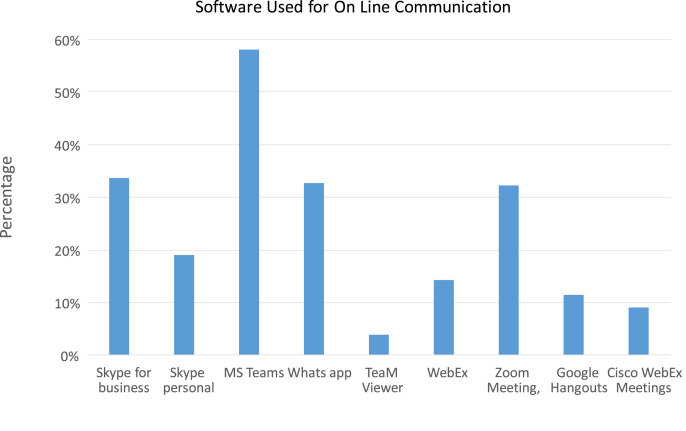

When asked about their software use for communicating through remote working, respondents were permitted multiple choices. The software with the highest usage was MS Teams (58%) as shown in Fig. 3 .

Fig. 3.

Software use for communicating during remote home working.

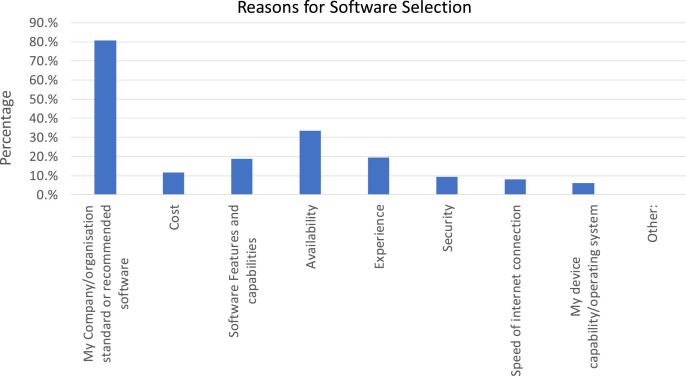

The vast majority of respondents (80.7%) indicated that their software use was dictated by their employers as being the preference/approved software. Whilst, secondary factors were noted by far fewer respondents such as availability (33.5%), experience (19.5%) and Software Features and capabilities (18.9%) (see Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Software preference reason.

When asked about how challenging they found it working at home in their first week due to Covid-19 work closures 12.6% of respondents stated that it is been very difficult, 34.4% of respondents found it difficult. Whilst 25.7% said this was a normal situation and 16.4% and 10.9% of participants stated that they found it easy or very easy respectively. This question was then repeated for their current experience compared to the first week of enforced working from home which would between 3 and 7 weeks experience after the start of lockdown depending on how quickly they completed the survey. Following up, 41.5% of respondents stated that they had got used to working from home finding it slightly better and easier, whilst 26.8% of respondents found the situation much better when compared to the first week. However, 19.1% and 12.6% of participants have still found this situation as challenging or getting more difficult respectively.

Respondents were also asked how long it took them to adapt to working from home following Covid-19, 34.9% stated they adapted themselves to work from home immediately from day one, whilst for 29.2% it took a several days, 14.2% a week, 13.2% two weeks 1.9% a month and 6.6% stated they had never adjusted to working from home.

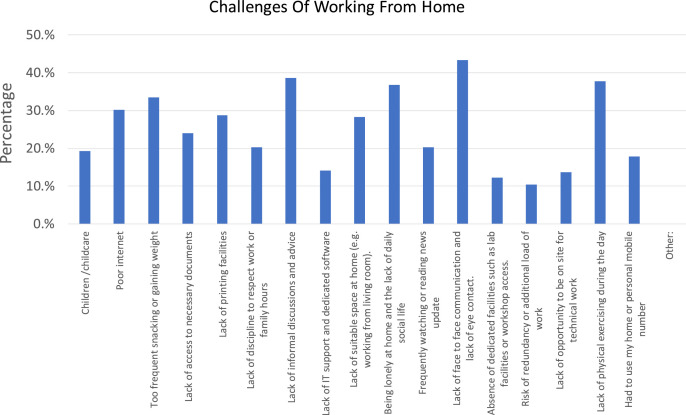

Respondents were asked about the main challenges of working from home during Covid-19, which permitted multiple responses. The greatest challenge (43%) was lack of face to face communication or lack of eye contact whilst 10.4% of respondents considered the risk of redundancy or additional workload as a challenge. The full list of challenges are shown in Fig. 5 , interestingly overall the lack of social face to face interaction featured in the three of the highest four scoring challenges alongside a lack of exercise.

Fig. 5.

Main challenges of working from home during Covid-19 for each variable.

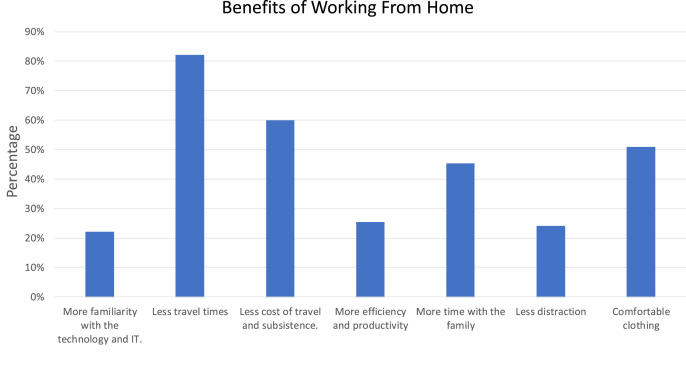

When asked about the benefits of working from home during Covid-19, respondents were given the opportunity to select multiple responses. Respondents almost universally noted reduced travel time (82%), followed by reduced costs related to travel and subsistence (60%) whilst the lowest number of respondents reported familiarity with the technology and IT (22.2%) as shown in Fig. 6 .

Fig. 6.

Main benefits of working from home during Covid-19 situation.

Respondents were asked whether their work type would permit them to continue to work from home after the Covid-19 restrictions had completely eased. The highest number (31.6%) suggested that their work may sometimes permit working from home, followed by 19.8% who felt that they would often be able to work from home and 11.3% who felt they could always work from home. Contrastingly, 9% stated that their type of work would rarely permit working from home and 9.4% stated that their type of work would never permit working from home. Interestingly 18.9% were unsure stating ‘I don't know’. Respondents were then asked if given the choice, how often they would prefer to work from home after COVID-19, over three quarters stated a preference to, with 34% and 32.5% of respondents stating that they would prefer to work from home sometimes and often respectively if allowed and 10.4% always. However, conversely 12.3% respondents stated they would rarely wish to work from home, 6.6% never and 4.2% didn't know their preference for working at home once the Covid-19 restrictions are fully lifted.

When respondents were asked whether they felt working from home achieved the same outcomes as working onsite 41.5% indicated that they felt that working from home will often, 27.8% sometimes and 13.7% always achieve the same outcomes. Whilst 8.5% felt rarely and 6.1% felt it never achieves the same outcomes whilst 2.4% of respondents didn't know.

When asked about whether they felt isolated working at home, 9.4% answered always, 21.7% often and 31.1% sometimes felt isolated when working from home. However, 23.1% and 14.2% of respondents stated that they rarely and never feel isolated when working from home.

When asked about their general opinion of working from home respondents were largely positive with 32.5% and 20.3% of respondents stating or they enjoy and enjoy very much working from home respectively and 24.1% of respondents stated they were neutral. Whilst only 14.6% and 8.5% of participants said they feel slightly dislike and dislike it respectively.

3.2. Qualitative response

The survey included the opportunity for respondents to provide an open text responses at the end provide personal experience in the form of comments of feelings about their experience.. From these comments it would appears that overtime these respondents had largely adapted to the challenges of working from home during Covid-19 as indicated below:

“The experience has been challenging but gradually getting the grip of it”.

In relation to the challenges, one of the respondents also stated that:

“Admin staff seems to be sending too many emails perhaps to show, that, they are working from home”.

This could reflect the psychology of some employees who would feel that it is a privilege to be working from home and they need to show their line managers that they are working as usual. In a traditional office based environment, being in the office is sufficient to evident their work, but being away, they might feel the need to over communicate with colleagues.

Another reasons could be related to the lack of phone calls or informal face-to-face discussions:

“My main thought is that working from home can be more inefficient as being at work. Face to face discussions are quicker and more informed than video call meetings. The decision-making process is slowed down, and communications are slower and more basic”.

“Poor communication, meaning if you're not present in office discussions or certain online meetings or group calls things are often missed or you're out of the loop”.

Another respondent indicated several challenges to working from home stating:

“Working from home loses team spirit and accuracy of work. Also, the face to face team interaction is missing with too many distractions despite the efficiency”.

This comment summarises some of the quantitative feedback we received which implied distraction could be related to family commitments or distraction from a change in work communication methods such as too many emails due to a lack of informal face-to-face discussions.

Another respondent commented on the difficulties of time management stating:

“Think the main problem with working from home is the lack of boundaries. This can be personal, such as the boundary to stop doing something and relax because you don't feel as if you have been as productive to deserve a break or it could be family members not being considerate to needs such as interrupting study sessions”.

People who live alone might feel lonely during lockdown, even if they are working from home. For example, one respondent stated:

“As I live on my own, I find one of the most difficult things to be lack of motivation, there is no one here to motivate me or support me. For example, getting up/out of bed and getting work done”.

This suggests that on-line conferencing might not have the same personal and psychological effect as face-to-face meetings. Another respondent indicated similar feedback in relation to transportation stating:

“I think working from home might be nice for people with commutes or family! I live alone and walking to work is nice exercise for me, so I miss it! It's also easier to work on projects if everyone's available for a quick chat face to face”.

Other employees feel that by working from home, they are helping their own employers but risking work-life balance; for example, one respondent stated:

“Working from home definitely helps the company but managing work life & balance should be important”.

So, the balance between social life, family life and work should be well organised to avoid unnecessary stress. Another respondent stated that:

“From my personal point of view, the work environment in the institutions gives a more formal feeling, time restrictions and commitment”.

This indicates it is easier to manage work-life balance when working away from home and enhances time management.

There were specific challenges for people who started their new job just before lockdown. For example, one respondent stated:

“I recently moved to a new project and new team, so my working remotely is not productive. I don't realize the scope of the work because I am new to the project. Other engineers are more productive than me because they have dealt with project issues. I am unlucky because Covid-19 comes at the time I moved to a new project and joining new team”.

Hence, special arrangements may be needed for new employees to support them in integrating into their new on-line work environment.

Another challenge which most families face is childcare as indicated by one of the respondents:

“Full time job and full time childcare, very challenging”.

This could be one of the main challenges whilst schools are closed. However, this challenge will have been less important once the schools or nurseries reopened.

Reduced transportation was reflected quantitatively as well as qualitatively by respondents’ comments. One respondent stated:

“Normally I work away from home in London 3 days a week. I didn't realize how stressful this was until I was working from home all the time. My mental health feels better because of it and I have more time to order my life. I've heard similar things from other people”.

“This event [Covid-19 Pandemic] has shown us that a lot of jobs can be done at home or can be partially done at home. This is good for the environment chiefly - less travel, electricity spent etc. - but also good for business as this means less unimportant meetings. I appreciate being able to work based on my sleeping pattern, not based only on traditional Victorian factory work schedules”.

Hence, the respondents seem to be positive about the environmental aspects and the elimination of daily commute.

Some types of work can be done from home without being affected by Covid-19 such as computer programming as indicated by one of the respondents:

“I do software development, so the work wasn't difficult to switch over to working from home. It is mainly the self-discipline to not step away from the computer and do something else and the fact how I'm sat at the computer for the entire day rarely leaving my room for both work and out of work hours”.

But the same statement indicated major issues to consider such as mental and physical health of not leaving the room or the desk for long hours. Other business might not have the same flexibility such as the service and hospitality industries as indicated by one of the respondents:

“Hospitality is a face-face business. My working from home has mainly been looking after the financials of the company but can be hard for a small business with cash handling.”

One of the issues that should be considered is the health and safety and the ergonomic considerations from working for a long time using unsuitable furniture in makeshift home working environments as indicated:

“Time off work isn't enough to actually feel relaxed in my home at the minute, set up my work laptop at a desk in my bedroom (so my sleep has suffered) with a cheap chair but usually have an ergonomic one at work. My back is killing but daren't go to the doctor for pain relief”.

“I had a few days of intermittent internet. I don't have a desk. I'm working in the same room as my son, which is very awkward if we both have meetings. Aside from that I don't miss public transport, I am saving loads of money, but just want my social life and exercise back and a desk with a couple of monitors instead of sitting cross-legged on the sofa with a laptop”.

This statement highlights the need for suitable internet infrastructure and a suitable computer workstation for safe use over long hours.

Reflecting on the long-term situation, hybrid working options where considered preferable, with considerations of the optimal ratio:

“I used to work from home 20% of the week (one day) I would like to return to work with the opposite proportion, work from home 80% and go into the office one day a week. That would be perfect for me”.

For some employees, the implications of the pandemic restrictions did not affect their working pattern much:

“I have been a homeworker since October 2019, so nothing has changed with regards to covid-19 for me”.

This suggests that a few business and employees were already in a good position to address the Covid-19 challenges due to a pre-existing flexible working culture.

3.3. Inferential analysis

A range of statistical analysis methods including multiple regression models were employed to test the validity of the three stated hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1: It is hypothesised that there is a relationship between the adaptability (to working from home) with age, highest education level, prior experience of homeworking, device capability, speed of internet connection, software features.

A multiple regression was run to predict the adaptability to working from home from variables of age, highest education level, prior experience of homeworking, device capability, speed of internet connection and software features. Among these variables, only variables of age (β = .13, p < .05) and previous experience of working from home (β = 0.27, p < .001) statistically significantly predicted the adaptability of working from home, F (6, 205) = 4.438, p < .001 and explained 11.5% of the variance. All other variables were not statistically significant to the prediction. This result suggests that as workers get older, they will find it easier to adapt to working from home and prior experience of working from home will also lead to more adaptability to working from home in Covid-19 situations. This finding on age is contrary to the cited literature [33], but perhaps in respect to the unique conditions of COVID is explained by the additional difficulties of caring for younger children that would be less of a challenge to older workers who would likely have older children.

Hypothesis 2: It is hypothesised that there is a relationship between adaptability to working from home with challenges (childcare, poor internet, snacking, lack of access to necessary documents, lack of printing facilities, lack of suitable space at home, being lonely, checking news frequently, lack of face to face communication, lack of lab facilities, risk of redundancy, lack of physical exercise, lack of opportunity to be on site to do technical work.)

To address this question, a multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to evaluate the prediction of the adaptability to working from home from the formally mentioned challenges. The result of the multiple linear regression analysis revealed that among the challenges listed above there is a statistically significant association between childcare (β = −.14, p < .05), lack of access to necessary documents (β = −0.17, p < .05), lack of face to face communication and eye contact (β = −0.18, p < .05), lack of physical exercising during the day (β = −0.19, p < .01) and the adaptability to working from home, F(15, 196) = 3.119, p < .001 and these factors explained 19.3% of the variance. These findings suggest that these four challenges have a significant contribution to predict the adaptability to working from home. In other words, as concerns increase regarding a lack of access to child care, not having access to necessary documentation, a lack of face to face communication and a lack of exercise, these will lead to a reduced satisfaction in working from home and therefore, the adaptability to working from home significantly decreases.

Hypothesis 3: It is hypothesised that greater challenges (childcare, poor internet, snacking, lack of access to necessary documents, lack of printing facilities, lack of discipline to respect work or family, lack of informal discussions, lack of IT support, lack of suitable space at home, being lonely, checking news frequently, lack of face to face communication, lack of lab facilities, risk of redundancy, lack of physical exercise, lack of opportunity to be on site to get technical work) will result in less enjoyment of home working.

A multiple regression analysis was performed to predict the enjoyment of working from home in relation to the listed challenges. Among the listed challenges, the variables of; lack of discipline to respect work or family hours (β = −0.16, p < .05), lack of face to face communication and eye contact (β = −0.20, p = .005) and lack of physical exercise during the day (β = −0.16, p < .05) statistically significantly predicted the enjoyment of working from home, F (15, 196) = 2.329, p = .004 and explained 15.1% of the variance. All other variables noted above were not statistically significant to the prediction. Therefore, this result suggests that, as concerns increase in relation to these three challenges the enjoyment of working from home will decrease accordingly.

4. Discussions

4.1. Practical implications

Reflecting on the data, it is evident that employers and employees are adapting to the culture of working from home when possible. There are several pros and cons from working from home during Covid-19. The main advantage was a lack of travelling time and reduced transportation costs. The issues identified were a lack of social activities, of face-to-face meetings and informal discussion. Being lonely at home was also identified as a negative point. A hospital radiologist, who would normally work in the hospital prior to Covid19, gave interesting feedback to the survey:

“In order for the hospital to reduce infection and density of employees due to Covid19, I started working from home using the right computer, monitor and software to provide reporting on scans of patients. This was rarely done in the past and I discovered that I only need to be physically at the hospital for only one day a week and for four days I could provide the medical reporting from home”.

A university academic has pointed out that on-line meetings provided an excellent tool to share documents and work on projects with several people with reduced travelling time and higher productivity. An industrial employee reported that on-line working styles are not suitable for hands-on work and only limited days of the month can work be done at home for activities such as writing reports of field visits. Parents who are employees or students with young children reported difficulties in utilising the working hours during the day when nurseries and schools are closed, this is one of the main issues cited relating to reduced productivity and perhaps an increase in stress. One of the advantages of working remotely is that people have learnt new software and presentation skills, and this could enable permanent culture change in organisations. Other people reported the lack of a healthy office desk and space to allow healthy working conditions, but reports have shown that some employers are providing office furniture or allowing employees to take their office facilities home with them. The self-determination theory is useful in exploring the reasons for how people managed to adjust and adapt to the rapidly to the conditions for working from home. This applies from the intrinsic motivation such as the feeling of self-satisfaction and the enjoyment of being able to continue with their work activities on-line with other people, and the ability to have some normality and continuity through their work. However, a key extrinsic driver and motivation is also likely to be of maintaining employment and income during these difficult and uncertain times, although this could link to the intrinsic motivation of the ability to feel in control of something in challenging times. In normal circumstances employees would need to, or request, training to be able to use software such as MS Teams or Zoom. However with the pandemic, it is evident that people have learnt the technology in a short period of time; simply stated it has shown that necessity is the mother of invention.

4.2. Implications of theory

There are many theories that could be reflected upon in literature, that would explain or guide individuals or organisations in relation to innovation or technology adaptation. Disaster management framework [25] could be a key theory to provide a strategy and plan in times of disaster, such as Covid-19 pandemic, to effectively manage the situation. The theory indicated that the formalisation of a performance management system during crisis management and creating key performance indicators are critical to monitor productivity and performance. Also having procedures for knowledge management and knowledge sharing, particularly during working from home, is critical for the survival of the organisation during crisis. One of the innovation theories, such as Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), indicates that adopter's attitude and expectations of the innovation influence the likelihood for its adoption [35]. In this research, it was evident that due to the pandemic, the technology acceptance (e.g. using on-line conference software) was much faster than the norm and this acceptance is related to people having no other options due to the pandemic (self-isolation or general lockdown). A similar theory to reflect this is Rogers' Innovation Diffusion Theory [36], which provides a general theory about what could influence an individual's choices about an innovation in normal situations. But due to the unforeseen situation of Covid-19 pandemic, the self-determination theory, developed by Ryan and Deci [28] could provide an explanation of why people have rapidly adopted on global level the innovative technologies, particularly in relation to working from home. The intrinsic motivation such as the enjoyment and the satisfaction of working from home, combined with the extrinsic motivation such as sustaining employability could explain the global attitude of employees as they are looking at the digital technology as the ‘survival kit’ or ‘necessity’; rather than an optional choice as most innovation adaptation theories address. Also the penalty of non-adopting could be costly such as indicating incompetency and lack of control.

4.3. Limitations and further work

This survey opened after the first 3 weeks of the UK lockdown gathering responses for a month and as such collected important early data that was beneficial in enabling a comparison of the respondent's adaptation to remote home working modes. The intention of this study was to capture these early reflections and experiences upon the initial difficulties in adapting to the new modes of remote working. As such this survey presents only a snapshot of the respondents experience at this time, a longitudinal study would be able to address the longer term experiences in relation to settling into a routine of home working and measuring the effects that schools readmitting pupils once the lockdown restrictions were eased would have. Additionally, this study does not consider the longer term effects of a working from home malaise that may have developed over the many months that followed. . Furthermore, future studies could consider also specific wellbeing considerations associated with remote and homeworking and the impact on their adaptability and enjoyment of remote working. These could include a consideration of human factors drawing information on the spaces being used for home working and any adaptations required and ergonomic considerations to give insights into how employers could better support employees remote working in the future. Another aspect for consideration could have been gathering data on the total number of hours worked per week and what the overall picture of the working day looked like during COVID restrictions with the lack of a necessity to conform to traditional 9-5 day and the additional concerns of juggling home life pressures such as schooling and potentially the need to avoid peak usage internet times to minimise bandwidth restrictions. Furthermore consideration of the mental tool of homeworking through loneliness and isolation and the impact that this has on working relationships over time could also be considered in combination with the above in relation to the impact on adaptability, enjoyment and the long term success factors for home working.

5. Conclusions

This study was conducted at the beginning of Covid-19 pandemic to identify opportunities and challenges of working from home. An on-line survey was conducted to capture the information and gather feedback from the public. The results show that the main challenges are of a psychological nature such as being lonely and lack of daily face-to-face discussions and informal meetings. While a lack of physical activities in and the challenges of key factors such as childcare and workload management has been also identified. The main advantages of remote working were reduced travel time and cost which has made people more productive, but has prevented effective work-home life boundaries being maintained for some. As human beings, we are social animals and it will be difficult to continue working from home without this social aspect during or after working hours. The family situation is found to be an influencing factor on the suitability of working from home, particularly with the closure of nurseries and schools. Several theories could explain the rapid adaptation of the technologies and the culture of working from home, but learning the tools to work remotely could be considered the ‘survival kit’ and necessity that required full adaptation in a very short period of time. The internet infrastructure in some regions and countries will need to be improved to allow the required bandwidth for comfortable online video conferencing without delays in the video or audio signals. The Covid-19 pandemic has provided a unique opportunity to understand the potential for enhanced remote working, and at-distance teaching, with greater potential for future developments to allow for international collaboration and cross-border employment in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Amin Al-Habaibeh: Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, VisualizationVisuali. Matthew Watkins: Validation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, VisualizationVisuali. Kafel Waried: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing – original draft. Maryam Bathaei Javareshk: Mathematical modelling, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Formal analysis.

References

- 1.Pan S.L., Cui M., Qian J. Information resource orchestration during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study of community lockdowns in China. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020;54 doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll N., Conboy K. Normalising the “new normal”: changing tech-driven work practices under pandemic time pressure. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matli W. The changing work landscape as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic: insights from remote workers life situations in South Africa. Int. J. Sociol. Soc. Pol. 2020;40(9/10):1237–1256. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richter A. Locked-down digital work. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scheiber N. 2020. Jobless Claims by Uber and Lyft Drivers Revive Fight over Labor Status. NY Times, 17th April.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/17/business/economy/coronavirus-uber-lyft-unemployment.html Available at: 15/07/21. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cho E. Examining boundaries to understand the impact of COVID-19 on vocational behaviours. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park Y., Fritz C., Jex S.M. Relationships between work-home segmentation and psychological detachment from work: the role of communication technology use at home. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2011;16(4):457. doi: 10.1037/a0023594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaklič A., Solina F., Šajn L. User interface for a better eye contact in videoconferencing. Displays. 2017;46:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moeckel R. Working from home: modeling the impact of telework on transportation and land use. Transportation Research Procedia. 2017;26:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowden R.J., Hostetter C. Access, utility, imperfection: the impact of videoconferencing on perceptions of social presence. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2012;28(2):377. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Graaff T., Rietveld P. Substitution between working at home and out-of-home: the role of ICT and commuting costs. Transport. Res. Pol. Pract. 2007;41(2):142–160. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carpenter Aubrey L., Pincus Donna B., Furr Jami M., Comer Jonathan S. Working from home: an initial pilot examination of videoconferencing-based cognitive behavioral therapy for anxious youth delivered to the home setting. Behav. Ther. 2018;49(6):917–930. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2018.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer A., Kramer K.Z. The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spurka D., Straubb C. Flexible employment relationships and careers in times of the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Vocat. Behav. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davison R.M. The transformative potential of disruptions: a viewpoint. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020;55 doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang J., Hayashi Y., Frank L.D. COVID-19 and transport: findings from a world-wide expert survey. Transport Pol. 2021;103:68. doi: 10.1016/j.tranpol.2021.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Richter A., Leyer M., Steinhüser M. Workers united: digitally enhancing social connectedness on the shop floor. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020;52 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanti https://www.ivanti.co.uk/company/press-releases/2020/survey-it-professionals-security-issue-increase

- 19.Richter A., Riemer K. Malleable end-user software. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2013;5(3):195. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brem A., Viardot E., Nylund P.A. Implications of the coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak for innovation: which technologies will improve our lives? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change. 2021;163:2021. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120451. ISSN 0040-1625, 120451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.George G., Lakhani K.R., Puranam P. What has changed? The impact of Covid pandemic on the technology and innovation management research agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2020;57(8):1754. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee S.M., Trimi S. Convergence innovation in the digital age and in the COVID-19 pandemic crisis. J. Bus. Res. 2021;123:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guggenberger T., Lockl J., Röglinger M., Schlatt V., Sedlmeir J., Stoetzer J.C., Urbach N., Völter F. Emerging digital technologies to combat future crises: learnings from COVID-19 to be prepared for the future. Int. J. Innovat. Technol. Manag. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giones F., Brem A., Pollack J.M., Michaelis T.L., Klyver K., Brinckmann J. Revising entrepreneurial action in response to exogenous shocks: considering the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Disaster Prev. Manag. An Int. J. 2020;14 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lettieri E., Masella C., Radaelli G. Disaster management: findings from a systematic review. Disaster Prev. Manag. An Int. J. 2009;18:117–136. doi: 10.1108/09653560910953207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ting D.S.W., Carin L., Dzau V., et al. Digital technology and COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020;26:459–461. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0824-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arribas-Ibar M., Nylund P.A., Brem A. The risk of dissolution of sustainable innovation ecosystems in times of crisis: the electric vehicle during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability. 2021;13(3):1319. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan R.M., Deci E.L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 2000;55(1):68. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Marri W., Al-Habaibeh A., Abdo H. Exploring the relationship between energy cost and people's consumption behaviour. Energy Procedia. 2017;105:3464–3470. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frederiks E.R., Stenner K., Hobman E.V. Household energy use: applying behavioural economics to understand consumer decision-making and behaviour. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015;41:1385–1394. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maslow A.H. A theory of human motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1943;50(4):370. doi: 10.1037/h0054346. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu W. The relationship between incentives to learn and Maslow's hierarchy of needs. Phys. Procedia. 2012;24:1335. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brynjolfsson E., Horton J.J., Ozimek A., Rock D., Sharma G., TuYe H.-Y. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2020. COVID-19 and Remote Work: an Early Look At US Data ( No. 27344)https://www.nber.org/papers/w27344 available at: [Google Scholar]

- 34.Haines N., Office of National statistics . 2017. Births by Parents' Characteristics in England and Wales: 2016.https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/livebirths/bulletins/birthsbyparentscharacteristicsinenglandandwales/2016 Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis F.D. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; 1986. A Technology Acceptance Model for Empirically Testing New End-User Information Systems: Theory and Results. (Doctoral dissertation) Retrieved from DSpace@MIT Database. (Accession No. 14927137) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers E.M. fifth ed. Free Press; New York: 2003. Diffusion of Innovations. [Google Scholar]