Abstract

Introduction

Early discontinuation and poor adherence are common limitations of conventional preventive migraine medications that limit their long-term efficacy. Therefore, a migraine preventive medication with favorable long-term safety is warranted.

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate the long-term safety and tolerability of fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic or episodic migraine in Japanese patients.

Methods

In this 52-week, randomized, open-label, parallel-group study, fremanezumab monthly or quarterly was administered in newly enrolled Japanese patients with chronic migraine or episodic migraine. Safety was assessed by monitoring of treatment-emergent adverse events, including injection-site reactions, laboratory and vital sign assessments. Newly enrolled patients and rollover patients from previous phase IIb/III trials who did not receive fremanezumab in this study were included in the immunogenicity testing cohort (n = 587). Efficacy outcomes included changes from baseline in the average monthly migraine days and headache days of at least moderate severity. Other efficacy outcomes included changes in disability scores.

Results

A total of 50 patients were enrolled with chronic migraine (monthly, n = 17; quarterly, n = 17) or episodic migraine (monthly, n = 8; quarterly, n = 8). The most commonly reported treatment-emergent adverse events were nasopharyngitis (64.0%) and injection-site reactions (erythema, 24.0%; induration, 10.0%; pain, 8.0%; pruritus, 6.0%). The discontinuation rate was low (4.0% from adverse events, 2.0% from a lack of efficacy) and no deaths were reported. The incidence of anti-drug antibody development was low (2.4%). Fremanezumab reduced monthly migraine days and headache days of at least moderate severity from 1 month after initial administration, and this effect was maintained with no worsening throughout 12 months. Fremanezumab also led to sustained reductions in any acute headache medication use and headache-related disability at 12 months.

Conclusions

Fremanezumab administered monthly and quarterly was well tolerated in patients with chronic migraine and episodic migraine and led to sustained improvements in monthly migraine days and headache days of at least moderate severity throughout 12 months.

Clinical Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03303105.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40264-021-01119-2.

Key Points

| This long-term, randomized, open-label trial in Japanese patients with chronic or episodic migraine found that fremanezumab was associated with no drug-related serious adverse events, or deaths reported during the 12-month study period. |

| The most common adverse events related to fremanezumab treatment were nasopharyngitis and injection-site reactions; antidrug antibody development was infrequent. |

Introduction

Currently available oral therapies for the prevention of chronic migraine (CM) and episodic migraine (EM), which include antiepileptic drugs, beta-blockers, antidepressants, and calcium channel blockers, are associated with several limitations. These broadly include adverse effects and a lack of efficacy [1–3], both of which lead to discontinuation and well-recognized poor adherence [2, 4–6]. A systematic review of studies related to propranolol, amitriptyline, and topiramate reported that persistence with these agents may fall to 7–55% at 12 months, mainly as a result of tolerability issues [7]. A subsequent retrospective claims analysis concluded that, although switching between oral migraine preventive medications is common, persistence worsens as patients cycle through various such agents [8]. A real-world treatment pattern survey in Japan confirmed that patients with both CM and EM also experience such limitations, indicating a need for well tolerated and effective migraine preventive options [3].

Monoclonal antibodies target the calcitonin gene-related peptide or receptor to specifically target migraine pathophysiological processes [3, 9, 10]. In addition, monoclonal antibodies have been shown to exhibit several advantages over oral migraine preventive medications, such as a long half-life that allows monthly or even quarterly administration and favorable tolerability [11, 12]. Fremanezumab, a fully humanized IgG2Δa/kappa monoclonal antibody, has been comprehensively investigated in two similar international large-scale, 12-week, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials in patients with CM (HALO CM trial) and EM (HALO EM trial) [13, 14]. In these trials, monthly or quarterly fremanezumab treatment reduced the average monthly headache days of at least moderate severity (HALO CM trial) and migraine days (HALO CM and EM trials) compared with placebo along with improvements in other outcomes, including those related to disability, with good tolerability. More recently, a 52-week, phase III, double-blind, randomized trial enrolled rollover patients from the HALO CM and HALO EM trials as well as newly enrolled patients to assess the long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of fremanezumab with long-term treatment [15]. Fremanezumab treatment for up to 12 months was well tolerated with no safety concerns identified, including immunogenicity, and led to sustained reductions in monthly migraine days, headache days, and headache-related disability vs baseline levels.

Japanese patients were included in the HALO CM, HALO EM, and long-term HALO extension trials, and demonstrated similar efficacy and safety profiles with the overall global study populations. Safety and efficacy of fremanezumab in Japanese patients with CM or EM requires further investigation for both regulatory and clinical purposes. In consideration of this, two separate randomized phase III studies have demonstrated favorable efficacy and safety of fremanezumab in Japanese and Korean patients with CM and EM [16, 17]. Based on this background, the objective of this trial was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of long-term study of monthly or quarterly fremanezumab for preventive treatment in Japanese patients with CM or EM.

Methods

Trial Design

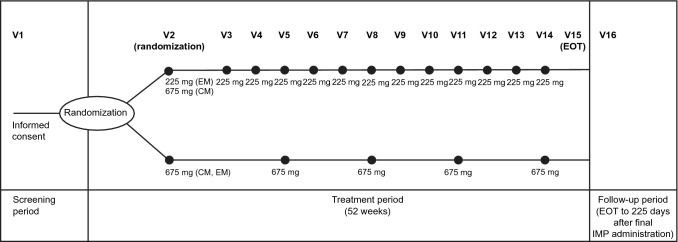

This multicenter, randomized, open-label trial in Japanese patients with CM or EM (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03303105) consisted of a 4-week screening period (Visit 1), a 52-week treatment period (Visit 2 to Visit 15), an end of treatment evaluation (Visit 15), and a follow-up period of 225 days after the final dose of fremanezumab to allow an anti-drug antibody (ADA) assessment to be performed (Visit 16; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Study design (newly enrolled patients). CM chronic migraine, EM episodic migraine, EOT end of treatment, IMP investigational medicinal product, V visit

Key inclusion criteria were a history of migraine (according to The International Classification of Headache Disorders, third edition [beta version] criteria) or clinical judgment suggests a migraine diagnosis for ≥ 12 months prior to giving informed consent. Included patients also had to fulfill criteria for EM or CM during the 28-day screening period in terms of frequency (headache occurring on ≥ 4 and ≤ 14 days for EM; ≥ 15 days for CM and fulfilling any of the criteria for migraine on ≥ 4 days for EM; ≥ 8 days for CM). Full inclusion and exclusion criteria for newly enrolled patients are listed in Table 1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). A subset of patients who completed or discontinued the phase IIb/III trials of CM or EM were also enrolled in this trial for the purpose of evaluating immunogenicity, although fremanezumab was not administered to these rollover patients.

Treatment

After obtaining informed consent and the initial screening for eligibility at Visit 1, newly enrolled patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to receive monthly or quarterly subcutaneous administration of fremanezumab according to schedules specific for CM or EM. Randomization was performed by means of electronic interactive-response technology, with stratification according to CM or EM.

Fremanezumab was subcutaneously administered according to the following monthly dosing regimen by clinical trial personnel responsible for the administration of injections. The monthly regimen was fremanezumab 675 mg (three injections of 225 mg per 1.5 mL) for CM and 225 mg (one injection of 225 mg per 1.5 mL) for EM at baseline (Visit 2) followed by 225 mg monthly thereafter (month 1 [Visit 3] to month 12 [Visit 14]). The quarterly dosing regimen was fremanezumab 675 mg (three injections of 225 mg per 1.5 mL) once every 3 months for both CM and EM groups (baseline [Visit 2], month 3 [Visit 5], month 6 [Visit 8], month 9 [Visit 11], month 12 [Visit 14]).

Outcomes

The safety objective of this trial was to assess the long-term safety and tolerability of fremanezumab in the preventive treatment of CM and EM. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) during the observation period were recorded based on patient reports using Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities version 22.0 by system organ class and preferred term and summarized according to severity, seriousness, and relationship to the study drug and treatment discontinuation. Injection sites were monitored for reactions (erythema, induration, ecchymosis, and pain) and classified according to severity (none; mild, ≤ 5 to 50 mm, moderate, > 50 to ≤ 100 mm; severe, > 100 mm) with pain graded on a 5-point scale (painless, 0 to extreme, 4). Treatment-emergent adverse events of special interest were the same as those included in the previous phase IIb/III trials of Japanese and Korean patients with CM and EM and included injection-site reactions, drug-related hepatic TEAEs, ophthalmic TEAEs of at least moderate severity, anaphylaxis and severe hypersensitivity reactions, and cardiovascular-related TEAEs. In addition, safety was monitored via clinical laboratory tests (chemistry, hematology, coagulation, and urinalysis) as well as the recording of 12-lead electrocardiograms, physical examination, vital signs (systolic and diastolic blood pressure, pulse rate, temperature, and respiratory rate), body weight, and the Electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale [18].

Efficacy outcomes included the average monthly migraine days and headache days of at least moderate severity (see Table 2 of the ESM). Other efficacy outcomes included the average monthly headache days of any severity, average monthly days with use of any acute headache medications, number of patients who discontinued concomitant preventive migraine medications during the treatment period, average monthly days with nausea or vomiting, and the average monthly days with photophobia and phonophobia. The ≥ 50% responder outcome at each month is the percentage of patients with a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly migraine days or monthly headache days of at least moderate severity in each month (1, 2, 3, 6, 12 months). Disability was assessed using the 6-Item Headache Impact Test (HIT-6) in patients with CM and the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) in patients with EM [19, 20]. Both the HIT-6 and MIDAS are reliable and validated tools with higher scores indicating more severe impact or disability.

Statistics

The International Conference on Harmonisation E1 guideline has recommended that at least 100 patients exposed to treatment for 1 year are needed to evaluate the long-term safety of medicines for non-life-threatening conditions [21]. In order to ensure at least 100 Japanese patients who had completed 1 year of treatment in the multinational phase III long-term trials and this trial, it was considered necessary to enroll 40 new patients in this trial.

The safety set consisted of new patients who received the study medication at least once. The full analysis set consisted of new patients in the safety set who had at least 10 days of baseline and post-baseline efficacy assessment data in the electronic headache diary. The immunogenicity analysis set comprised newly enrolled patients, patients enrolled in the phase IIb/III CM trial in Japanese and Korean patients who rolled over to this trial, or patients enrolled in the phase IIb/III EM trial in Japanese and Korean patients after trial resumption and rolled over to this trial who had received one or more doses of the study medication in any trial and in whom the date and time of serum ADA was recorded at one or more post-dose time points in this trial.

Safety and efficacy outcome measurements were descriptively analyzed. For the efficacy analyses, headache-related data were normalized to 28 days of data when the number of evaluation days of the electronic headache diary in each month was 10 days or more. Missing data were not imputed. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all statistical calculations.

Results

Subject Disposition and Baseline Characteristics

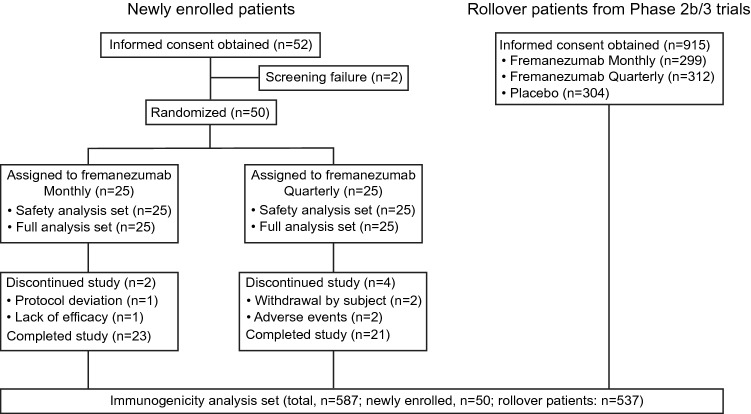

New patients for the assessment of efficacy were enrolled from 11 institutions in Japan (Table 3 of the ESM) whereas patients who continued from the previous phase IIb/III CM and phase IIb/III EM trials for ADA assessment were enrolled from institutions in Japan and Korea. The trial was conducted from December 2017 to June 2020. Flow of patients throughout the trial is summarized in Fig. 2. In total, six patients discontinued treatment mainly for adverse events (n = 2) and withdrawal by subject (n = 2) with a lack of efficacy and protocol deviation responsible for discontinuation in one patient each. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of newly enrolled patients are summarized in Table 1. In the two fremanezumab groups combined, the proportion of female patients was 84.0% and the mean ± standard deviation (SD) age was 46.3 ± 7.4 years. The proportion of patients receiving preventive migraine medications was 46.0% and the mean ± SD number of years since onset of migraine was 20.2 ± 11.7 years. The two fremanezumab groups combined consisted of 34 patients with CM and 16 patients with EM. In the two fremanezumab groups combined, the baseline mean ± SD monthly migraine days and headache days of at least moderate severity were 13.9 ± 5.5 days and 12.3 ± 6.2 days, respectively. The proportion of patients receiving acute headache medications at baseline was 98.0% and the proportion of patients receiving migraine-specific acute headache medications (triptans or ergot derivatives) at baseline was 92.0%.

Fig. 2.

Patient disposition

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics

| Fremanezumab | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly (n = 25) | Quarterly (n = 25) | Total (n = 50) | |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 46.8 (7.9) | 45.8 (7.0) | 46.3 (7.4) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD) | 22.2 (3.8) | 22.7 (4.1) | 22.5 (3.9) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 23 (92.0) | 19 (76.0) | 42 (84.0) |

| Migraine subtype, n (%) | |||

| Chronic migraine | 17 (68.0) | 17 (68.0) | 34 (68.0) |

| Episodic migraine | 8 (32.0) | 8 (32.0) | 16 (32.0) |

| Disease history | |||

| Time since onset of migraine, year, mean (SD) | 23.9 (13.3) | 16.5 (8.6) | 20.2 (11.7) |

| Use of preventative migraine medication at baseline, yes, n (%) | 14 (56.0) | 9 (36.0) | 23 (46.0) |

| Disease characteristics during 28-day preintervention period | |||

| Number of days with headache of any severity and duration, mean (SD) | 17.8 (6.5) | 18.5 (6.9) | 18.1 (6.6) |

| Number of migraine days, mean (SD) | 14.1 (5.6) | 13.8 (5.5) | 13.9 (5.5) |

| Number of headache days of at least moderate severity, mean (SD) | 11.8 (5.8) | 12.8 (6.7) | 12.3 (6.2) |

| Use of any acute headache medications, yes, n (%) | 25 (100.0) | 24 (96.0) | 49 (98.0) |

| Use of migraine-specific acute headache medicationsa, yes, n (%) | 25 (100.0) | 21 (84.0) | 46 (92.0) |

SD standard deviation

aTriptans and ergot compounds

Safety

Results of the safety analysis in newly enrolled patients are shown in Table 2. Treatment-emergent adverse events were reported in 92.0% (23/25 patients) in the monthly fremanezumab group and 88.0% (22/25 patients) in the quarterly fremanezumab group with nasopharyngitis being the most common TEAE (fremanezumab monthly, 72.0% [18/25 patients], fremanezumab quarterly, 56.0% [14/25 patients]). No deaths were reported during the study period and serious TEAEs occurred only in two patients in the fremanezumab quarterly group (rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and subarachnoid hemorrhage). However, no serious TEAEs were considered to be potentially drug related. Two patients in the fremanezumab quarterly group discontinued the trial because of TEAEs, of which one patient had trial discontinuation thought to be drug related (injection-site reaction).

Table 2.

Summary of adverse events

| Characteristics, n (%) | Fremanezumab | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly (n = 25) | Quarterly (n = 25) | Total (n = 50) | |

| Patients with at least one TEAE | 23 (92.0) | 22 (88.0) | 45 (90.0) |

| Patients with at least one TEAE related to the trial regimen | 11 (44.0) | 6 (24.0) | 17 (34.0) |

| Patients with at least one serious TEAE | 0 | 2 (8.0) | 2 (4.0) |

| Patients with any TEAE leading to discontinuation of the trial | 0 | 2 (8.0) | 2 (4.0) |

| Death | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Patients with TEAE reported in ≥ 5% of patients in any group | |||

| Injection-site reactions | |||

| Erythema | 7 (28.0) | 5 (20.0) | 12 (24.0) |

| Induration | 3 (12.0) | 2 (8.0) | 5 (10.0) |

| Pain | 1 (4.0) | 3 (12.0) | 4 (8.0) |

| Pruritus | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| Infections and infestations | |||

| Gastroenteritis | 3 (12.0) | 1 (4.0) | 4 (8.0) |

| Influenza | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 18 (72.0) | 14 (56.0) | 32 (64.0) |

| Oral herpes | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| Back pain | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| Dysmenorrhea | 2 (8.0) | 1 (4.0) | 3 (6.0) |

| Cough | 1 (4.0) | 2 (8.0) | 3 (6.0) |

TEAE treatment-emergent adverse event

Regarding TEAEs of special interest, one ophthalmic adverse event of moderate severity (rhegmatogenous retinal detachment) was observed but evaluated as not related to fremanezumab treatment and the patient recovered. No patients experienced possible trial-agent-induced liver injury, anaphylaxis, or severe hypersensitivity reactions. Regarding cardiovascular-related TEAEs, hemiparesis was reported in one patient in the monthly fremanezumab group whereas tachycardia, increased blood pressure, hypertension, and subarachnoid hemorrhage were reported in one patient each in the quarterly fremanezumab group. The most common injection-site reaction was erythema, which occurred in 24.0% of patients overall, followed by induration (10.0% of patients). All injection-site reactions were evaluated as mild or moderate in severity and recovered, although one patient with an injection-site reaction discontinued treatment.

Changes in vital signs and electrocardiogram findings during the long-term follow-up were minor and reported in only a small number of patients treated with fremanezumab. No patients had a positive score on the Electronic Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale for assessing suicidal ideation and behavior after fremanezumab administration.

Immunogenicity

Of 587 patients enrolled in the immunogenicity analysis set, 14 (2.4%) patients were ADA negative before fremanezumab administration and ADA positive after administration, suggesting a treatment-related reaction. Of these treatment-related ADA-positive patients, three patients (fremanezumab monthly, n = 2; fremanezumab quarterly, n = 1) were newly enrolled and 11 patients were from the continuation cohort (fremanezumab monthly, n = 5; fremanezumab quarterly, n = 6). Further, 12 patients produced neutralizing antibodies of which two patients were newly enrolled and ten patients were from the continuation cohort. No relationship was found between ADA and efficacy or safety. More specifically, no adverse events considered to be ADA related, such as anaphylaxis or severe hypersensitivity reactions, were observed in subjects with ADA.

Efficacy

Results of the efficacy analysis in newly enrolled patients are shown in Table 3. These reveal reductions in the average monthly migraine days, headache days of at least moderate severity, headache days of at any severity, and use of any acute headache medication. From baseline to 1 month, the mean (95% confidence interval [CI]) change in the average monthly migraine days was − 4.1 (− 6.37, − 1.85) with fremanezumab monthly treatment and − 4.2 (− 6.40, − 2.04) with fremanezumab quarterly treatment. Similarly, the mean (95% CI) change in the average monthly headache days of at least moderate severity was − 3.6 (− 5.67, − 1.59) with fremanezumab monthly treatment and − 4.7 (− 6.62, − 2.79) with fremanezumab quarterly treatment. From baseline to 12 months, the mean (95% CI) change in the average monthly migraine days was − 5.9 (− 7.72, − 4.04) with fremanezumab monthly treatmen and − 1.6 (− 4.08, 0.94) with fremanezumab quarterly treatment. Similarly, the mean (95% CI) change in the average monthly headache days of at least moderate severity was − 4.3 (− 6.03, − 2.50) with fremanezumab monthly treatment and − 2.1 (− 3.92, − 0.24) with fremanezumab quarterly treatment. Fremanezumab reduced the average monthly migraine days and headache days of at least moderate severity from 1 month after initial administration, which was maintained throughout the treatment period.

Table 3.

Summary of efficacy results

| Fremanezumab | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Monthly | n | Quarterly | |||

| Actual | Change from baseline | Actual | Change from baseline | |||

| Average monthly migraine days, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Baseline | 25 | 14.1 (5.6) | 25 | 13.8 (5.5) | ||

| Month 1 | 25 | 10.0 (7.0) | − 4.1 (5.5) | 25 | 9.5 (6.4) | − 4.2 (5.3) |

| Month 3 | 25 | 12.0 (7.3) | − 2.1 (5.5) | 25 | 11.7 (7.0) | − 2.1 (6.5) |

| Month 6 | 24 | 11.3 (6.6) | − 2.9 (4.9) | 23 | 10.7 (6.4) | − 3.3 (4.2) |

| Month 12 | 23 | 8.5 (5.6) | − 5.9 (4.3) | 22 | 12.4 (7.0) | − 1.6 (5.7) |

| Average monthly headache days of at least moderate severity, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Baseline | 25 | 11.8 (5.8) | 25 | 12.8 (6.7) | ||

| Month 1 | 25 | 8.2 (6.0) | − 3.6 (4.9) | 25 | 8.1 (6.7) | − 4.7 (4.6) |

| Month 3 | 25 | 9.9 (6.9) | − 2.0 (5.2) | 25 | 10.1 (7.7) | − 2.7 (6.1) |

| Month 6 | 24 | 9.8 (6.2) | − 2.1 (4.2) | 23 | 10.1 (7.2) | − 3.2 (4.2) |

| Month 12 | 23 | 8.0 (5.4) | − 4.3 (4.1) | 22 | 11.0 (7.4) | − 2.1 (4.1) |

| Average monthly headache days at any severity, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Baseline | 25 | 13.8 (6.6) | 25 | 14.1 (7.3) | ||

| Month 1 | 25 | 9.8 (7.5) | − 4.0 (5.7) | 25 | 9.2 (7.0) | − 4.9 (4.5) |

| Month 3 | 25 | 11.2 (7.4) | − 2.6 (5.3) | 25 | 11.2 (8.1) | − 2.8 (5.8) |

| Month 6 | 24 | 10.8 (6.9) | − 3.2 (4.7) | 23 | 11.0 (7.2) | − 3.7 (4.1) |

| Month 12 | 23 | 8.5 (5.5) | − 5.8 (4.4) | 22 | 12.2 (7.1) | − 2.3 (4.9) |

| Average monthly days with use of any acute headache medication, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Baseline | 25 | 13.7 (6.8) | 25 | 13.8 (6.6) | ||

| Month 1 | 25 | 10.3 (7.3) | − 3.4 (5.1) | 25 | 9.0 (5.9) | − 4.8 (5.1) |

| Month 3 | 25 | 11.0 (6.6) | − 2.7 (6.3) | 25 | 11.2 (7.3) | − 2.6 (5.8) |

| Month 6 | 24 | 12.0 (7.1) | − 1.9 (5.6) | 23 | 11.5 (6.6) | − 2.8 (4.0) |

| Month 12 | 23 | 9.5 (6.1) | − 4.5 (5.6) | 22 | 11.8 (5.4) | − 2.3 (4.6) |

| Average monthly days with nausea or vomiting, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Baseline | 25 | 5.2 (5.5) | 25 | 3.7 (3.5) | ||

| Month 1 | 25 | 3.5 (5.8) | − 1.7 (2.6) | 25 | 2.3 (2.9) | − 1.4 (3.0) |

| Month 3 | 25 | 4.4 (6.0) | − 0.8 (5.1) | 25 | 3.4 (4.6) | − 0.3 (3.1) |

| Month 6 | 24 | 3.4 (4.6) | − 1.9 (4.8) | 23 | 2.3 (3.2) | − 1.7 (3.5) |

| Month 12 | 23 | 2.2 (3.1) | − 3.2 (4.4) | 22 | 3.7 (4.3) | − 0.4 (4.5) |

| Average monthly days with photophobia and phonophobia, mean (SD) | ||||||

| Baseline | 25 | 6.5 (6.8) | 25 | 5.3 (6.4) | ||

| Month 1 | 25 | 5.6 (7.7) | − 1.0 (4.3) | 25 | 4.2 (6.7) | − 1.1 (4.8) |

| Month 3 | 25 | 6.5 (7.9) | 0.0 (4.6) | 25 | 4.4 (7.3) | − 0.9 (6.2) |

| Month 6 | 24 | 5.7 (7.2) | − 0.8 (4.8) | 23 | 4.0 (6.3) | − 1.5 (4.6) |

| Month 12 | 23 | 3.5 (4.0) | − 3.1 (4.3) | 22 | 5.1 (7.1) | − 0.6 (6.2) |

SD standard deviation

According to the responder analyses, the percentage of patients with a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly migraine days in the monthly and quarterly fremanezumab groups was 28.0 and 24.0% at 3 months, and 43.5 and 22.7% at 12 months, respectively (Table 4 of the ESM). The percentage of patients with a ≥ 50% reduction in monthly headache days of at least moderate severity in the monthly and quarterly fremanezumab groups was 28.0 and 24.0% at 3 months, and 34.8 and 18.2% at 12 months, respectively (Table 4 of the ESM).

In addition to headache-related outcomes, reductions from baseline were also found in disability scores in both patients with CM and EM with available data following long-term fremanezumab treatment. In patients with CM (monthly, n = 17, quarterly n = 17), the mean ± SD HIT-6 score at baseline and at month 12 was 63.6 ± 4.3 and 58.5 ± 4.1, respectively, in the monthly fremanezumab group and 62.8 ± 5.3 and 58.6 ± 4.6, respectively, in the quarterly fremanezumab group. In both fremanezumab groups combined, the mean change from baseline at month 12 in HIT-6 score showed a reduction of – 5.1 ± 4.8. Similarly, in patients with EM (monthly, n = 8, quarterly n = 8), the mean ± SD MIDAS score at baseline and at month 12 was 20.5 ± 22.1 and 11.4 ± 25.4, respectively, in the monthly fremanezumab group and 12.6 ± 13.7 and 11.9 ± 21.6, respectively, in the quarterly fremanezumab group. In both fremanezumab groups combined, the mean change from baseline at month 12 in the MIDAS score showed a reduction of − 3.4 ± 15.2.

Discussion

The results of this multicenter, randomized, open-label trial in Japanese patients with CM or EM support the long-term safety and efficacy of fremanezumab reported in previous international trials that enrolled Japanese patients and two specific phase IIb/III trials in Japanese and Korean patients. Adverse events and adverse drug reactions were common but there were few serious or severe adverse events, or discontinuations related to adverse events. Results related to the safety of long-term fremanezumab broadly reflect those derived from Japanese patients enrolled in the HALO long-term study presented previously (Table 5 of the ESM) [15, 22]. In particular, the total incidences of common injection-site reactions in the present study (erythema, 24.0%; induration, 10.0%; pruritus, 6.0%) were comparable to those in Japanese patients from the HALO long-term study (erythema, 18.2%; induration, 14.2%; pruritus, 9.1%), while erythema in the overall HALO population was also similar (26.3%). In the present study, injection-site reactions were evaluated as mild or moderate in severity and all cases recovered with few discontinuations related to injection-site reactions. The investigator or sub-investigator assessed the case of rhegmatogenic retinal detachment as moderate and considered it to be related to aging and not to external factors, and thus determined that the event was not related to the study drug. Similarly, the case of hemiparesis due to subarachnoid hemorrhage, despite being rated as severe by the investigator or sub-investigator, was judged to be not related to the study drug because it was caused by a congenital rupture of a cerebral aneurysm. Nasopharyngitis was also commonly noted in the analysis of Japanese patients from the HALO long-term trial population [22]. Results of the immunogenicity analysis found low levels of treatment-emergent ADA responses and production of neutralizing antibodies, which is also consistent with the results of the international HALO long-term trial [15].

As noted in previous trials, ophthalmic events of at least moderate severity were defined as adverse events of special interest based on results of unconfirmed preclinical findings in monkeys. In this study, ophthalmic events occurred in only one patient and were not considered related to fremanezumab. No safety signal was detected in this study consistent with results obtained from the HALO long-term trial [15].

Regarding efficacy, the average monthly migraine days and headache days of at least moderate severity decreased as soon as 1 month after treatment in both fremanezumab groups, and the reduction was maintained without return to baseline levels during long-term treatment. This is similar to the result of two separate randomized placebo-controlled trials of monthly and quarterly fremanezumab phase IIb/III trials in Japanese and Korean patients with CM and EM. In these trials, reductions were also evident within 1 month after baseline and were maintained during the 12-week treatment. Hence, the efficacy results of this long-term trial exclusively in Japanese patients extend those of previous phase IIb/III trials in similar populations. The HALO long-term trial also noted a rapid mean change in the average monthly migraine days that was sustained during the long-term follow-up to 12 months [15, 22]. Results of the present long-term trial, in terms of the mean changes in average monthly migraine days and headache days of at least moderate severity, followed similar trends in the HALO long-term trial. Migraine-related disability score was measured by the HIT-6 in patients with CM and by the MIDAS questionnaire in patients with EM. Scores for both questionnaires at month 12 showed decreases from baseline in the two fremanezumab groups combined.

For clinical practice, the results of this study support the potential benefits of fremanezumab administration. Migraine is a chronic disease associated with high rates of poor adherence to preventive medication, mainly as a result of adverse reactions or a lack of efficacy [1–7]. Fremanezumab offers good tolerability and a choice of dosing options to meet individual patient needs, providing the potential to improve medication persistence along with clinical outcomes.

The main limitations of this study were the lack of a placebo comparison arm and relatively small patient numbers to evaluate safety and tolerability. As a result, it is difficult to evaluate the efficacy effects of treatment in detail because the number of patients was small and there was no comparison with placebo as the study was intended primarily for the assessment of safety. Further studies, including those in real-world settings, will help provide a fuller assessment of the long-term safety and tolerability of fremanezumab treatment.

Conclusions

Fremanezumab monthly or quarterly shows favorable long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy in Japanese patients with CM or EM. Fremanezumab provides an effective treatment option for migraine prevention by its effect on reducing pain and disability.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients for their participation in the trial, and all trial sites, investigators, and all clinical research staff for their contributions. The authors also thank Yoshiko Okamoto, PhD, and Mark Snape, MBBS, of inScience Communications, Springer Healthcare, for helping write the outline and first draft of the manuscript. This medical writing assistance was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Declarations

Funding

This study was funded by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Conflict of interest

FS reports being an advisor for Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd., Eli Lilly, and Amgen. NS reports personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. XN is a full-time employee of Teva Branded Pharmaceutical Products R&D. MI, CU, KI, YI, and NK are full-time employees of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Ethics approval

The institutional review board or independent ethics committee/ethics committee approved this protocol.

Consent to participate

Patient consent was documented on a written informed consent form, which was accompanied by written information for patients and the informed consent forms were approved by the same institutional review board or independent ethics committee/ethics committee that approves this protocol. Each written information for patients and informed consent form complied with the International Conference on Harmonisation Good Clinical Practice Guideline 18 and local regulatory requirements.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and material

Anonymized individual participant data that underlie the results of this study will be shared with researchers to achieve aims pre-specified in a methodologically sound research proposal.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Author contributions

FS, NS, XN, MI, CU, and KI were involved in the conception or design of the study. FS, NS, MI, CU, and KI were involved in the data acquisition or analysis. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data as well as drafting and revising the manuscript.

References

- 1.Blumenfeld AM, Bloudek LM, Becker WJ, Buse DC, Varon SF, Maglinte GA, et al. Patterns of use and reasons for discontinuation of prophylactic medications for episodic migraine and chronic migraine: results from the second international burden of migraine study (IBMS-II) Headache. 2013;53(4):644–655. doi: 10.1111/head.12055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loder EW, Rizzoli P. Tolerance and loss of beneficial effect during migraine prophylaxis: clinical considerations. Headache. 2011;51(8):1336–1345. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2011.01986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ueda K, Ye W, Lombard L, Kuga A, Kim Y, Cotton S, et al. Real-world treatment patterns and patient-reported outcomes in episodic and chronic migraine in Japan: analysis of data from the Adelphi migraine disease specific programme. J Headache Pain. 2019;20(1):68. doi: 10.1186/s10194-019-1012-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonafede M, Wilson K, Xue F. Long-term treatment patterns of prophylactic and acute migraine medications and incidence of opioid-related adverse events in patients with migraine. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(9):1086–1098. doi: 10.1177/0333102419835465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Gillard P, Hansen RN, Devine EB. Adherence to oral migraine-preventive medications among patients with chronic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(6):478–488. doi: 10.1177/0333102414547138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woolley JM, Bonafede MM, Maiese BA, Lenz RA. Migraine prophylaxis and acute treatment patterns among commercially insured patients in the United States. Headache. 2017;57(9):1399–1408. doi: 10.1111/head.13157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF. Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm. 2014;20(1):22–33. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.1.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hepp Z, Dodick DW, Varon SF, Chia J, Matthew N, Gillard P, et al. Persistence and switching patterns of oral migraine prophylactic medications among patients with chronic migraine: a retrospective claims analysis. Cephalalgia. 2017;37(5):470–485. doi: 10.1177/0333102416678382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edvinsson L. Role of CGRP in migraine. In: Brain SD, Geppetti P, editors. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) mechanisms. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. pp. 121–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edvinsson L, Haanes KA, Warfvinge K, Krause DN. CGRP as the target of new migraine therapies—successful translation from bench to clinic. Nat Rev Neurol. 2018;14(6):338–350. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Headache Society The American Headache Society position statement on integrating new migraine treatments into clinical practice. Headache. 2019;59(1):1–18. doi: 10.1111/head.13456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dodick DW. CGRP ligand and receptor monoclonal antibodies for migraine prevention: evidence review and clinical implications. Cephalalgia. 2019;39(3):445–458. doi: 10.1177/0333102418821662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dodick DW, Silberstein SD, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T, et al. Effect of fremanezumab compared with placebo for prevention of episodic migraine: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(19):1999–2008. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silberstein SD, Dodick DW, Bigal ME, Yeung PP, Goadsby PJ, Blankenbiller T, et al. Fremanezumab for the preventive treatment of chronic migraine. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(22):2113–2122. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goadsby PJ, Silberstein SD, Yeung PP, Cohen JM, Ning X, Yang R, et al. Long-term safety, tolerability, and efficacy of fremanezumab in migraine: a randomized study. Neurology. 2020;95:e2487–e2499. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakai F, Suzuki N, Kim B-K, Igarashi H, Hirata K, Takeshima T, et al. Efficacy and safety of fremanezumab for chronic migraine prevention: multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, parallel-group trial in Japanese and Korean patients. Headache. 2021;61:1092–1101. doi: 10.1111/head.14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakai F, Suzuki N, Kim BK, Tatsuoka Y, Imai N, Ning X, et al. Efficacy and safety of fremanezumab for episodic migraine prevention: multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial in Japanese and Korean patients. Headache. 2021;61:1102–1111. doi: 10.1111/head.14178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mundt JC, Greist JH, Gelenberg AJ, Katzelnick DJ, Jefferson JW, Modell JG. Feasibility and validation of a computer-automated Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale using interactive voice response technology. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(16):1224–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, Bjorner JB, Ware JE, Jr, Garber WH, Batenhorst A, et al. A six-item short-form survey for measuring headache impact: the HIT-6. Qual Life Res. 2003;12(8):963–974. doi: 10.1023/A:1026119331193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart WF, Lipton RB, Dowson AJ, Sawyer J. Development and testing of the Migraine Disability Assessment (MIDAS) Questionnaire to assess headache-related disability. Neurology. 2001;56(6 Suppl. 1):S20–S28. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.suppl_1.S20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. ICH topic E 1: population exposure: the extent of population exposure to assess clinical safety. CPMP/ICH/375/95. Available from: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2009/09/WC500002747.pdf. Accessed 18 Dec 2020.

- 22.Ning X, Cohen JM, Wu M, Nagaoka T, Sakai F. Efficacy and safety of fremanezumab versus placebo for the preventive treatment of episodic migraine (EM) and chronic migraine (CM) in a subpopulation of Japanese patients: results from the randomized, double-blind, phase 3 HALO studies. Presented at the 48th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Headache Society; 7–8 November 2020.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.