Abstract

On January 26, 2011, the Pardon of Patrick Murphy, a document in the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) Record Group 153 (RG 153) Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), was submitted to conservation for examination. The record was examined with special focus on the handwritten “1865” to the left of Abraham Lincoln's signature. All analysis techniques were non-sampling, non-invasive, and non-damaging as retaining the integrity of cultural heritage is very similar to the forensic handling of evidence. Microscopy, transmitted light, Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence, and X-Ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy analysis confirmed that the ink used to write the “5”, in the April 14, 1865 date is different from the remaining text written by Lincoln and these analytical forensic-inspired techniques allowed scientists and conservators to “set the record straight” about the modern forged “5” for future generations of researchers.

Keywords: Microscopy, Transmitted light, Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence, X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy

1. Introduction

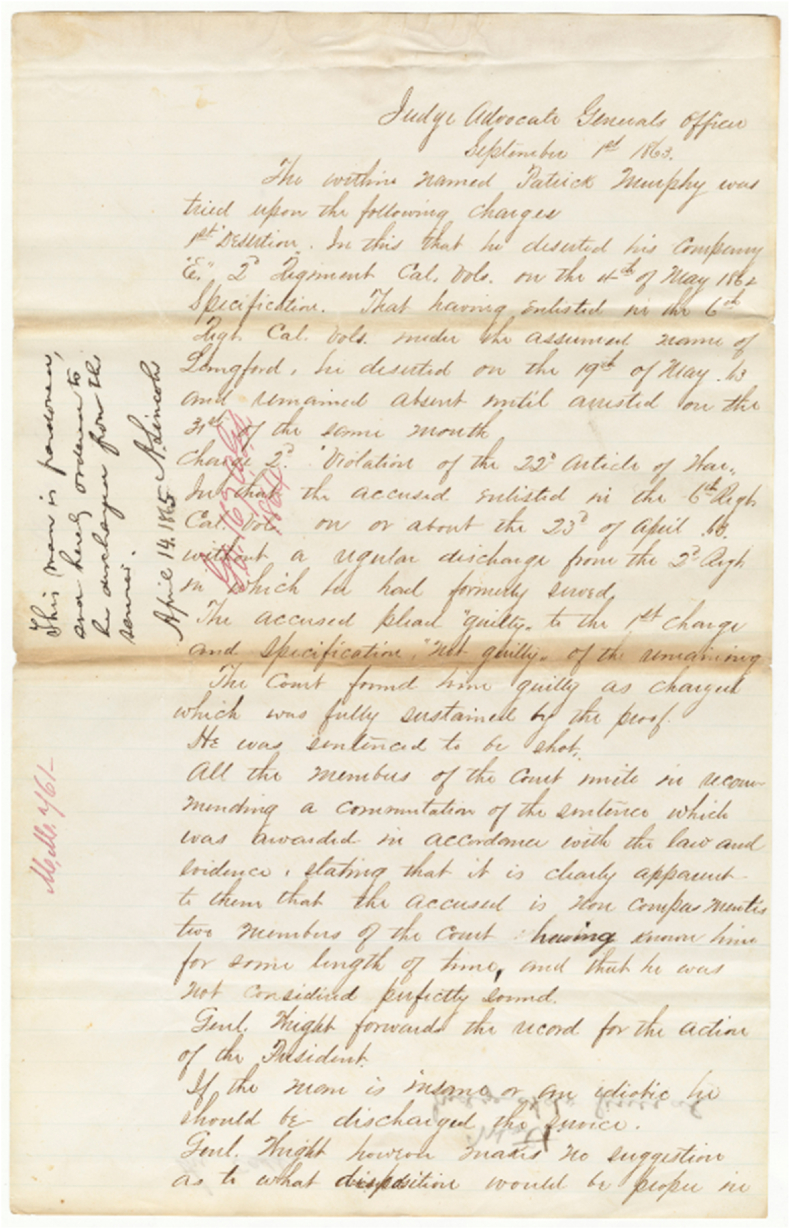

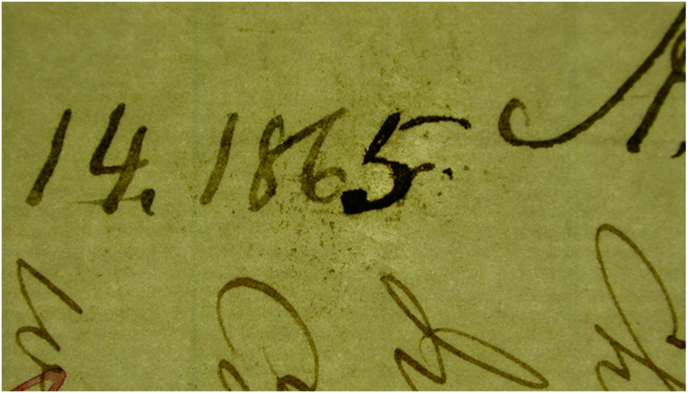

Abraham Lincoln regularly ranks within the top three Presidents in yearly surveys of the best and worst Presidents of the United States throughout the nation's history [1]. He has a reputation for mercy and signed 128 pardons during his Presidency. One such pardon was for Patrick Murphy, a private from California in the 2nd Infantry, Company E found in the National Archives and Record Administration's (NARA) Record Group 153: Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General (Army), 1792–2010 (Fig. 1, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/1839980), which is a letter dated September 1, 1863 from the Judge Advocate General's Office requesting the President pardon Patrick Murphy from being shot to death for desertion and violating the 22nd Article of War. This same letter contains a pardon statement written by President Lincoln perpendicularly to the original letter in the left margin. This pardon reads, “This man is pardoned, and hereby ordered to be discharged from the service.” then dated “April 14, 1865” and signed “A. Lincoln.” To the left and below the pardon statement are notations citing the case number “MM 761” and an endorsement date of “1864” in red ink. The second page is the initial statement dated June 12th, 1863, from the General Court Martial recommending leniency in pardoning Patrick Murphy. Because the date of Lincoln's pardon - April 14, 1865 - is the very day Lincoln was assassinated, signing this pardon would be one of Lincoln's last actions prior to his death. Therefore, this Lincoln-signed pardon was made famous in Civil War Era history circles when a researcher published his book based upon the idea that Lincoln's last act in life was one of mercy - even on his last day on Earth, Lincoln was saving others from death. However, with the increased scrutiny, questions arose about the authenticity of the year of Lincoln's signature and whether evidence of tampering could be found (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

NARA ID31839980: https://catalog.archives.gov/id/1839980 Page of unwatermarked (H) 12 9/16″ X (W) 7 15/16″ paper that contains Lincoln's pardon written perpendicularly in the left margin of the letter from the Judge Advocate General's Office requesting the President pardon Patrick Murphy.

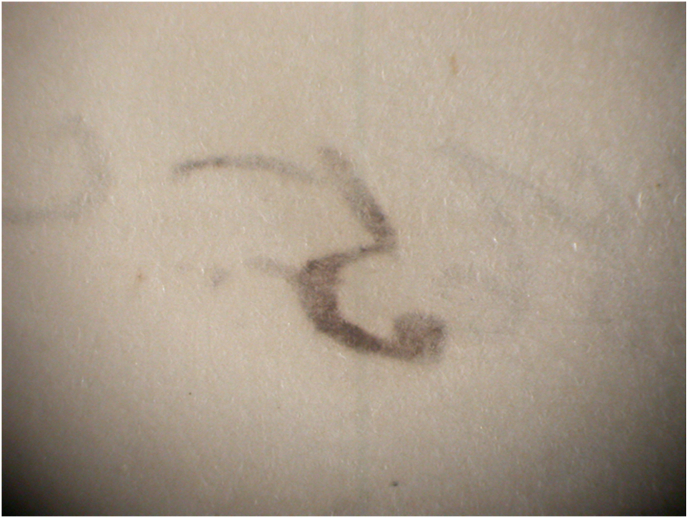

Fig. 2.

Close up photograph of the pardon statement written and signed by Lincoln with the questionable “5” appearing darker than the surrounding ink.

Following typical procedures in forensic laboratories when first receiving evidence, the entire document was carefully examined, and notable features and observations were recorded. The pardon consists of two sheets of stationery paper adhered with an unidentified glue/adhesive to one another along the top edge. The top page is an unwatermarked (H) 12 9/16″ X (W) 7 15/16″ sheet of ruled paper, while the second page is a (H) 9 7/8″ X (W) 7 7/8″ sheet of ruled paper. The entire document exhibits three pronounced horizontal creases and a vertical crease 11/16″ from the left edge indicating the document was previously folded before being accessed by NARA and stored flat. The inks used in this document appear to be iron gall ink, which can vary in color based upon recipe and age but is consistent with the period [2]. As a note, the second page of the letter was not examined during the investigation as Lincoln's writing is only on the front left of the top page.

Additionally, archivists remembered transcriptions of this document in Roy P. Basler's definitive Lincoln document source “The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln” published in 1953 which listed the date as April 14, 1864 [3]. This date would be more in line with the 1864 endorsement date. Therefore, the conservation and heritage science labs at NARA were asked by the textual archivists and holdings protection staff to analyze the document more closely for information to support that the “5” was a forgery and if it might be possible to reverse any inflicted damage.

The heritage science lab was well equipped to help answer the forensic questions surrounding this cultural heritage object since many analytical techniques, including microscopy, ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence, Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and X-ray fluorescence (XRF) analysis, have found wide use in both forensic [[4], [5], [6]] and cultural heritage applications [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. While these techniques are most frequently deployed in NARA's labs to learn more about the material history of a record, unexpected, anachronistic and measurable material differences can have important implications for record integrity, authentication and provenance. Thus, the analytical challenges faced during cultural heritage and forensic examination often overlap. In the specific case of the Lincoln pardon document, visual observations of the date were made under different conditions, including visible and ultraviolet radiation, and XRF analysis was used to compare the elemental composition of the ink in the different numbers of the date.

2. Forensic and cultural heritage examination methods

Optical microscopy was performed using a Wild M − 8 Stereozoom microscope with 6X-50× magnification and reflective fiber optic lighting for both transmitted light and raking light. The ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence was observed at 254 nm, 302 nm, and 365 nm using a hand-held Spectroline Longlife Filter Highest Intensity short wave UV lamp. Non-destructive XRF using the Bruker ARTAX 400 XRF system with a rhodium source (50 kV, 700 μA), a helium flush, 0.65 mm collimator, and a collection time of 60 s was used to analyze Lincoln's signature and several numbers and features of the date, including the questionable “5” and uninked paper. Spectra were collected at 50 keV to capture the full range of elements 50 keV, after which the spectral range was modified to 25 keV to focus on lower weight elements, such as iron.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Stereozoom microscope examination

3.1.1. Recto

The “1865” date was first examined under magnification and reflective fiber optic lighting. Magnification shows the ink used to write the number “5” is different in overall color and edge opacity compared to the preceding “186” numbers (Fig. 3A, Fig. 3B). The “5” ink is a darker brown - almost black - compared to the paler brown of the “186”. The “186” numbers are more translucent, the “5” has greater opacity along the edges of the number. The “5” also displays tine indentations from the pen nib, while tine indentations are not visible in the other numbers. Vestiges of ink from a scratched away number can be seen below and beside the darker “5” as well as smeared across the paper. These ink residues are similar in color to the other numbers in the date and are most clearly visible near the curve of the “5,” and appear likely to be the end of the horizontal line and foot from the “4” recorded in transcriptions of the pardon. Fig. 3B adds an overlay of the “4” Lincoln wrote in the day of the date (”14”) to the image in Figure A to show for the foot and the horizontal line of a “4” would fit with the traces of the original number written by Lincoln and transcribed in Basler's collected Lincoln writings.

Fig. 3A.

Normal illumination under 6× magnification. Note the obvious color difference and tine marks that only appear in the “5” of the date. In the second image, a “4” was overlaid to show how the original 4 might have appeared. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 3B.

Normal illumination under 6× magnification but with the “4” from Lincoln's date, “April 14” overlaid to show approximately where the original “4” may have been. Notice the foot and horizontal lines of a “4” overlay with the dark areas that remained after the removal of the original number.

The “1865” date was also viewed under raking light (Fig. 4). The fiber optic light source was placed at a 180○ angle to the text, allowing the light to “wash” across the surface of the paper accentuating hills and valleys in the paper texture. Under magnification the raking lighting revealed paper abrasion under and around the “5”. It is possible to see vertical striations and abraded paper surfaces. This abrasion is not found anywhere else on the pardon document.

Fig. 4.

Raking light under 6× magnification. Note the heavily abraded paper surface around the “5” and vestiges of the ink from the “4” which had been previously written.

3.1.2. Verso

The document was turned over and the verso was examined. It is characteristic for iron gall ink to strike-through or penetrate to the back of the paper. This means it is possible to see the image of the front text on the back of the sheet. The strike-through of the Lincoln text is visible, but it is noticeably more intense in the “5” as seen in Fig. 5. This prominent strike-through may be attributed to the darker, blacker ink being applied more heavily to the paper already thinned when the original ink of the “4” was scratched away.

Fig. 5.

Strike-through of “5” on the verso, 6× magnification. Note the strong strike-through of the ink from the “5” as compared to the lighter penetration of the older ink.

3.2. Transmitted light

The document was examined by transmitted light. It is apparent that the paper around the “5” is thinner than its surroundings. Greater light is transmitted through the thinned paper near the “5” as seen by the halo of light around the “5” in Fig. 6. Residues of ink from the “4” scratched away were caught in the abraded paper fibers and can be clearly seen with transmitted light. This paper around the date appears to look “dirty” because of these dark particles of ink trapped in the abraded paper surface.

Fig. 6.

Transmitted light showing thinned paper around the “5” with the halo of light. Notice the trapped ink particles around the “5”.

3.3. Ultraviolet-induced visible fluorescence

The document was placed under ultraviolet radiation at wavelengths of 254 nm, 302 nm, and 365 nm. Ultraviolet radiation may be absorbed by a substance and appear darker or may excite a substance to fluoresce. In this case, all three wavelengths caused the ink to absorb the UV radiation but the “5” appears darker than the “186” likely due to the thicker application as well as potentially different ink composition (see below for XRF results). Fig. 7 depicts the document under 254 nm radiation. The UV irradiation also revealed UV absorbing residue smeared around the “5” which is not visible around the “186” or other areas of text. This suggests that ink particles from the original number “4” were caught in the paper fibers when the “4” was removed.

Fig. 7.

UV absorption at 254 nm. Note the smear of absorbing residue around the “5” from the abraded paper fibers capturing ink particles as the original number was scratched away.

3.4. XRF analysis

Non-invasive XRF using the Bruker ARTAX allows the identification of the elemental composition of areas of interest on historic and culturally important documents. Knowing the elemental composition of different areas of a document can help provide insight into degradation as well as intentional changes to the document. XRF analysis plays a significant role in the museum and conservation community because non-invasive techniques are preferred for analyses of irreplaceable heritage objects [10]. The design of the NARA ARTAX XRF allows the instrument to be positioned very closely but safely to the document with a spot size down to about 1 mm so that small areas of interest, such as a line of text, can be distinguished from other features of the document. The crosshairs shown in Fig. 8 mark the center of some examples of the 0.65 mm spots selected for analysis, including the center of the center of the thickest part of the “L” in Lincoln's signature, the center of the thickest part of the “5” and the center of the residue of the suspected “4” removed during the forgery.

Fig. 8.

Examples of three of the different analysis spots selected to compare the ink used by Lincoln in the L of his signature, the questionable “5” and the vestiges of the abraded “4” also written by Lincoln.

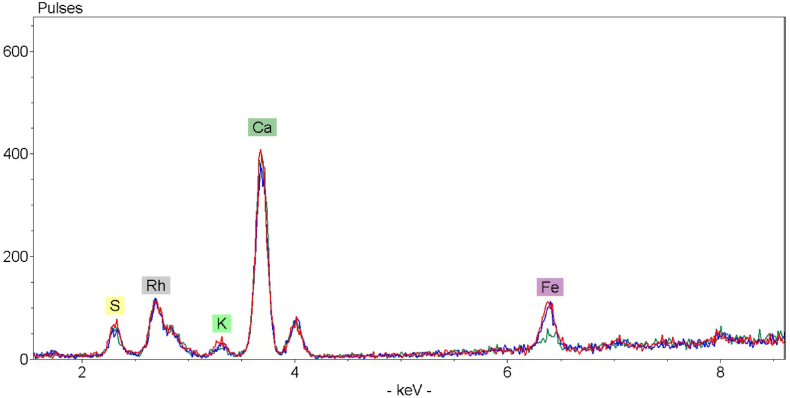

The ink used by Lincoln in the “L” of his signature and the “8” of the unquestioned date were compared to the paper background (Fig. 9), where the region of interest was selected to show the most prominent energy lines related to the ink analysis. Notice the near perfect overlay of the ink from the “L” and the “8” which supports that the same ink was used in both places (red and blue spectra, respectively). The iron signal from the paper is much lower than the iron of the ink; iron is often found on historic documents due to the water used during the papermaking process or iron-containing dust and dirt that would have collected during their use prior to storage and preservation at NARA. Iron gall inks typically include potassium and sulfur in their components and these elements are present in both inks as well as the iron expected from the ink name [2]. The spectrum of the inks and paper also contain calcium, which is likely present in paper substrate as an added filler during production. The peak for rhodium is backscatter from the excitation and not part of the actual chemical composition of the document.

Fig. 9.

XRF spectral comparison of the elements found in the “L” of Lincoln's signature (red trace) and the “8” of the unquestioned date (blue trace) with the elements found in the uninked paper (green trace). Instrumental parameters: 50 kV, 700 μA, 50 keV, a helium flush, 0.65 mm collimator, and a collection time of 60 s. Only the region of interest is shown in the graph. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 10, plotted on the same scale as Fig. 9, shows the ink used to write the number “5” compared to the ink used by Lincoln in the “L” of his signature and the “8” of the date. The overall signal for the elements used in the ink (iron, potassium, and sulfur) of the “5” are much higher than observed for the ink used by Lincoln. While clearly also an iron gall ink, the increased signal from the ink of the “5” may at first be interpreted as being due to the much thicker application. However, a distinctive difference in composition between the two inks is found by comparing the ratios of iron to sulfur or iron to potassium, since the ratios of iron to the other ink elements in the questionable “5” are not the same as the ratios of these same elements in the historic ink. The ratio of iron to sulfur in Lincoln's ink is 1.5 while the forged “5” has a ratio of iron to sulfur of 4.2 which, along with the optical examination and previous documentation of the pardon support that the “5” is not part of the original date written.

Fig. 10.

XRF spectral comparison of the elements found in the “L” of Lincoln's signature (red trace) and the “8” of the unquestioned date (blue trace) with the elements found in the questionable “5” (black trace). Instrumental parameters: 50 kV, 700 μA, 50 keV, a helium flush, 0.65 mm collimator, and a collection time of 60 s. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Once the full spectral range was analyzed to identify elements present, the analysis conditions were modified to focus on the iron and lower weight elements. The rhodium source energy range was changed to 25 keV, still through a 0.65 mm collimator with a helium flush for a collection time of 60s. The vestiges of the scraped “4” was compared to Lincoln's “8” and the questionable “5” (Fig. 11). The comparison again shows that spectra of the ink used by Lincoln give an almost perfect overlay while the forged “5” is very different from the historic ink; the elemental ratios in the historic ink do not match the ratios from the “5” ink, suggesting that the “5” was written using a different ink composition. Combining the analytical results with Basler's transcription and the archivist's recollections, there is strong support that the ink was not written by Lincoln but at a more recent time with a thicker application after Lincoln's original “4” was removed.

Fig. 11.

XRF spectral comparison of the elements found in the vestiges of the scraped away “4” (red trace) and the “8” of the unquestioned date (blue trace) with the elements found in the questionable “5” (black trace). Instrumental parameters: 50 kV, 700 μA, 25 keV, a helium flush, 0.65 mm collimator, and a collection time of 60 s. Only the region of interest is shown in the graph. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

4. Conclusions

Non-invasive XRF analysis, microscopy and examination under different lighting conditions allowed conservation and heritage science investigators to “set the record straight” regarding the forging of the date on the pardon of Patrick Murphy. Using XRF to compare the ink used to write the number “5” to the ink used by Lincoln in his signature and other areas of the date, it is apparent that the ink attributed to Lincoln in the date and his signature gives the same peak patterns, peak ratios, and signal response for the key elements detected [iron, calcium, sulfur, potassium] regardless of the sample area analyzed, while the ink of the questionable “5” gives different patterns, ratios, and signal response. Most obviously, the forged “5” gives a much larger response and in different proportions for the iron and sulfur than the Lincoln ink. Optical examination under different lighting supports the conclusion that the original number, a “4” based upon recorded transcriptions, was scratched away thus thinning and abrading the paper and allowing the new ink of the “5” to be highly visible on both sides of the document. These results support that the “5” was written using a different ink composition at a different time and more thickly applied. The differences between the altered “5” and the original “186” and even the vestiges of the original “4” are distinguished more clearly because of the use of the detailed forensic approach. The data collected was augmented by paper conservation expertise that determined any further intervention or attempted removal of the new “5” could not be done selectively and would only further damage the original materials of the historical document. A report summarizing the forensic examination accompanies the pardon of Patrick Murphy in the National Archives catalog so that future researchers will have access to the original information in the record as well as how the record was altered.

5. Postscript

This paper aims to document the forensic and cultural heritage analysis performed to determine if the forged “5” could be removed without losing the traces of the original “4” written by Abraham Lincoln. Those who wish for more information on the criminal investigation, please see the press release from the National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/press/press-releases/2011/nr11-57.html and NARA catalog entry (https://catalog.archives.gov/id/1839980).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the NARA colleagues who searched the archives finding aids and participated in the legal investigation: Greg Tremaglio, Trevor Plante, Mitchell Yockelson, Paul Brachfeld.

References

- 1.CBS news story about: the results of a sweeping survey of historians, political scientists and presidential scholars maintained by the Siena College Research Institute. Since 1982, the SCRI Survey of U.S. Presidents has been conducted during the second year of the first term of a new president, ranking presidents across 20 different categories, ranging from integrity to ability to compromise. https://www.cbsnews.com/pictures/presidents-ranked-worst-best/40/April 2021

- 2.Eusman E. Iron gall ink history. 1998. https://irongallink.org/iron-gall-ink-history.html

- 3.NARA youtube interview documenting the altered date and background for the criminal investigation into the researcher who changed the date from 1864 to 1865 to gain renown. 2011. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qKo8H9NN4nA January 24

- 4.Saadat S., Pandey G., Dharmavaram M. In: Technology in Forensic Science. Rawtani Deepak, Hussainv Chaudhery Mustansar., editors. Wiley-VCH GmbH; Boschstr: 2020. Microscopy for forensic investigations. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appoloni C.R., Melquiades F.L. Portable XRF and principal component analysis for bill characterization in forensic science. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2014;85:92–95. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2013.12.004. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0969804313005940 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vittiglio G., Bichlmeier S., Klinger P., Heckel J., Fuzhongal W., Vincze L., Janssens K., Engström P., Rindby A., Dietrich K., Jembrih-Simbürger D., Schreiner M., Denis D., Lakdar A., Lamotte A. A compact μ-XRF spectrometer for (in situ) analyses of cultural heritage and forensic material. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. Atoms. 2004;213:693–698. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0168583X03016872 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castro K., Pessanha S., Proietti N., Princi E., Capitani D., Carvalho M.L., Madariaga J.M. Noninvasive and nondestructive NMR, Raman and XRF analysis of a Blaeu coloured map from the seventeenth century. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2008;391:433–441. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gorassini A., Adami G., Calvini P., Giacomello A. ATR-FTIR characterization of old pressure sensitive adhesive tapes in historic papers. J. Cult. Herit. 2016;21:775–785. [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Hoyo-Meléndez J., Gondko K., Mendys A., Król M., Klisiſska-Kopacz A., Sobczyk J., Jaworucka-Drath A. A multi-technique approach for detecting and evaluating material inconsistencies in historical banknotes. Forensic Sci. Int. 2016;266:329–337. doi: 10.1016/j.forsciint.2016.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith G., Hamm J., Kushel D., Rogge C. Collaborative Endeavors in the Chemical Analysis of Art and Cultural Heritage Materials ACS Symposium Series. American Chemical Society; Washington, DC: 2012. What's wrong with this picture? The technical analysis of a known forgery.https://pubs.acs.org/doi/pdf/10.1021/bk-2012-1103.ch001 [Google Scholar]