Abstract

The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family consists of a large group of evolutionarily divergent glycoproteins. The secreted pregnancy-specific glycoproteins constitute a subgroup within the CEA family. They are predominantly expressed in trophoblast cells throughout placental development and are essential for a positive outcome of pregnancy, possibly by protecting the semiallotypic fetus from the maternal immune system. The murine CEA gene family member CEA cell adhesion molecule 9 (Ceacam9) also exhibits a trophoblast-specific expression pattern. However, its mRNA is found only in certain populations of trophoblast giant cells during early stages of placental development. It is exceptionally well conserved in the rat (over 90% identity on the amino acid level) but is absent from humans. To determine its role during murine development, Ceacam9 was inactivated by homologous recombination. Ceacam9−/− mice on both BALB/c and 129/Sv backgrounds developed indistinguishably from heterozygous or wild-type littermates with respect to sex ratio, weight gain, and fertility. Furthermore, the placental morphology and the expression pattern of trophoblast marker genes in the placentae of Ceacam9−/− females exhibited no differences. Both backcross analyses and transfer of BALB/c Ceacam9−/− blastocysts into pseudopregnant C57BL/6 foster mothers indicated that Ceacam9 is not needed for the protection of the embryo in a semiallogeneic or allogeneic situation. Taken together, Ceacam9 is dispensable for murine placental and embryonic development despite being highly conserved within rodents.

The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family is a branch of the immunoglobulin superfamily and consists of a large group of evolutionarily highly divergent glycoproteins (11, 55, 60). Based on sequence similarities and expression pattern, they can be subdivided into two subgroups: the CEA and the pregnancy-specific glycoprotein (PSG) subgroups. The members of the CEA subgroup are mostly membrane anchored and are found in a wide variety of cell types, e.g., epithelial and endothelial cells, granulocytes, macrophages, B cells, and activated T cells, whereas the expression of the PSGs is restricted predominantly to trophoblast cell lineages (12).

CEA-related molecules have been implicated in a number of normal and pathological processes. CEA-related glycoproteins seem to play a role in the control of granulocyte and T-cell activation (20, 23, 49), as well as in the regulation of differentiation and tissue remodeling, such as the supposed involvement of CEA cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1) in breast duct formation and angiogenesis (6, 7, 16). The expression of a number of CEA family members is often deregulated in tumors (18, 34, 42, 47), and in vitro and in vivo experiments suggest that they play a role in tumor genesis either by enhancement of metastasis or suppression of anoikis (13, 36, 54). CEACAM1 (for the recently revised nomenclature of the CEA family, see reference 1) can act as a tumor suppressor, and its common loss of expression in epithelial tumors probably causes deregulation of growth or differentiation (15, 24). Furthermore, most CEA subfamily glycoproteins serve as receptors for bacterial pathogens, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae (3, 9, 56), whereas murine CEACAM1 and CEACAM2 are responsible for mouse hepatitis virus entry into cells (5, 33).

Although PSGs represent the most abundant fetal protein in the maternal circulation at term (27), little is known about their function. Low levels of PSG correlate with poor outcomes of pregnancies, and anti-PSG antibodies have been demonstrated to induce abortions in mice and monkeys (2, 14, 28, 30, 31, 53). Recent findings indicate that PSGs might act via receptors on monocytes by inducing cytokines favorable to TH2 immune responses which are biased in the maternal immune system during pregnancy (44, 58). The shift from a TH1 to a TH2-type immune status together with a preference of the innate over the adaptive immune system in the placenta is thought to be important for the acceptance of the histoincompatible fetal tissue during pregnancies without compromising strong immune reactions against pathogens (45, 57, 59). PSGs and other trophoblast members of the CEA family might thus be involved in protecting the semiallotypic fetus from the maternal immune system.

The murine Ceacam9 gene encodes a secreted two-immunoglobulin (Ig)-domain glycoprotein which cannot be clearly assigned to either subgroup. Although it shares a higher degree of sequence similarity with CEA subgroup members, it is exclusively expressed in trophoblast cells reminiscent of PSGs. However, its spatio-temporal expression pattern differs from that of the PSGs. Ceacam9 mRNA is found during early stages of placental development mainly in specific subpopulations of primary and secondary trophoblast giant cells, whereas PSG transcripts accumulate in the mature placenta, predominantly in the spongiotrophoblast (8, 22). Due to the rapid evolution of the CEA families, orthologous genes are difficult to assign even between closely related mammals, such as rat and mouse. CEACAM9 represents an exception in exhibiting a sequence identity of 91% (Finkenzeller and Zimmermann, unpublished results). In contrast, the only other identifiable homologous gene product, CEACAM1, shares 74% of its amino acid sequence between the rat and mouse. This suggests that CEACAM9 plays an important function during placental development in rodents.

In order to clarify the in vivo functions of Ceacam9, gene ablation experiments were performed. Here we report for the first time on the inactivation by homologous recombination of a member of the murine Cea gene family. Ceacam9−/− males and females are viable and fertile and exhibit no obvious phenotype. This indicates that even highly conserved members of the evolutionarily young Cea gene family serve subtle functions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Construction of the targeting vector.

The mouse genomic cosmid clone cosC3 from BALB/c liver DNA containing the Ceacam9 gene was used to construct the targeting vector (8, 43). Digestion with BamHI yielded a 7.5-kb fragment and a 3.5-kb fragment comprising the promoter region and part of exons 2 and 3, respectively. To generate the targeting vector, the 7.5-kb BamHI DNA fragment was ligated with a BamHI-HindIII adapter which destroyed the BamHI sites and subcloned into the HindIII-digested pPGKneo vector (48) upstream of the neomycin expression cassette. After digestion of the 3.5-kb BamHI DNA fragment with EcoRI, the 1.7-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment was cloned after ligation of an EcoRI-BamHI adapter into the BamHI-digested targeting vector downstream of the neo cassette. To allow negative selection against random integration, a pMCI-HSV-TK cassette (29) was introduced 3′ of the 1.7-kb BamHI-EcoRI Ceacam9 fragment. The resulting targeting construct lacks, in comparison with the genomic sequences, a 1.5-kb BamHI DNA fragment which comprises 340 bp of the 5′-flanking region, exon 1, intron 1, and part of exon 2. It was replaced by a 1.7-kb neo cassette. For electroporation, the targeting vector was linearized with KpnI.

Gene targeting in embryonal stem cells and generation of mutant mice.

The BALB/c-derived embryonic stem (ES) cell line BALB/c-I (35) was maintained on a layer of mitomycin C-treated G418-resistant embryonal mouse fibroblasts used as feeder cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium (Life Technologies) with 15% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum (FCS) (Life Technologies) containing 4.5 mg of glucose/ml, 2 mM glutamine, 50 U of penicillin per ml, 50 μg of streptomycin per ml, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 1,000 U of leukemia inhibitory factor/ml, and 0.8 mg of adenosine 0.73 mg of cytidine, 0.85 mg of guanosine, 0.24 mg of thymidine, and 0.73 mg of uridine per 100 ml (all supplements were from Life Technologies). A sample of 107 BALB/c-I ES cells was electroporated with 25 μg of the linearized targeting vector DNA at 240 V and 500 μF in phosphate-buffered saline. The electroporated cells were placed under selection and replica plated as previously described (51).

Ceacam9 mutant ES cell lines were injected into day 3.5 postcoitum (p.c.) (C57BL/6 × DBA/2)F1 blastocysts. After 2 h in culture in M16 medium (Sigma), the embryos were surgically transferred into the uteri of pseudopregnant NMRI recipients at day 2.5 p.c. Male chimeras were mated with BALB/c females to produce mice heterozygous for the null mutation. F1 intercrosses of heterozygous mice finally resulted in F2 offspring which were wild type and heterozygous or homozygous for the targeted allele. Heterozygous mice were backcrossed to BALB/c and 129/Sv mice for four generations. Then, Ceacam9−/− strains were established by crossing heterozygous animals and maintained by breeding Ceacam9−/− males and females.

Mouse genotyping.

Homologous recombination between the targeting vector and Ceacam9 on mouse chromosome 7 was examined by PCR and Southern blotting using genomic DNA isolated from ES cells or tail biopsies after digestion in lysis buffer with 100 μg of proteinase K/ml (25). PCR was performed using three primers in two separate reaction tubes. One pair of primers included the mutant allele-specific bpA primer (5′-TGGGAAGACAATAGCAGGCATGC), which binds in the 3′ region of the neomycin cassette, and a second pair of primers included the wild-type allele-specific wild-type oligonucleotide (5′-TCAGCACAGTGATAGGAAAACCG), which binds in the N-terminal domain exon. Both primers were combined with the common M8-ko oligonucleotide (5′-ATCCTGCTGACTGGAGTTTTACC), which binds in the 3′ untranslated region of Ceacam9 downstream of the 1.7-kb BamHI-EcoRI fragment also present in the targeting construct. The mutant allele gave rise to a 2,012-bp fragment, and the wild-type allele gave rise to a 2,089-bp fragment. Both PCRs were performed in Taq polymerase buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 50 mM KCl) complemented with 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM (each) deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 1 pmol of each primer/μl, and 1 U of Taq polymerase for 35 cycles (denaturation, 94°C, 15 s; annealing, 65°C, 30 s; elongation, 72°C, 3 min).

The established Ceacam9 knockout strain was genotyped using two different pairs of oligonucleotides as PCR primers in one reaction mixture. The mutant allele-specific primers (5′-ATGCGGCGGCTGCATACGCTTGATCC and 5′-CGTCAAGAAGGCGATAGAAGGCGATGC-3′ [32]) bind in the neomycin gene and generate a 427-bp DNA fragment, while the wild-type allele-specific primers (5′-CTTAACCTGCTGGAATGCACCCGCCG and 5′-GCACTTCCAGATGCACATGTG-TTAATTCG), located in the N-terminal domain exon, gave rise to a 349-bp fragment. The PCR was performed as described above using modified cycle conditions (denaturation, 94°C, 45 s; annealing, 60°C, 45 s; elongation, 74°C, 1 min).

Southern and Northern blot analyses.

Genomic DNA isolated from ES cells or tail tips was digested with HindIII, separated by electrophoresis through a 1% agarose gel overnight, and transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane. 32P-labeled 0.5- and 1.8-kb EcoRI-BamHI fragments were used as probes to confirm correct homologous recombination in the 5′- and 3′-flanking regions, respectively (Fig. 1A). Northern blot analysis of Ceacam9 and β-actin transcripts was performed as described before (8).

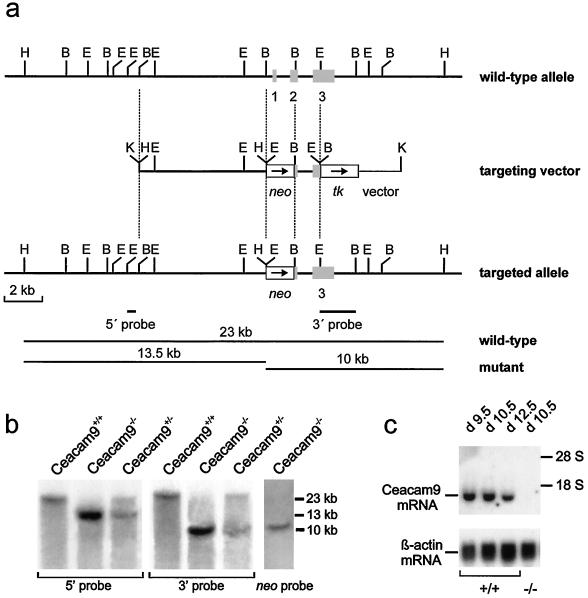

FIG. 1.

Targeted disruption of the murine Ceacam9 gene. (a) Structure of the wild-type allele, targeting construct, and recombinant locus. Gray boxes represent the three exons of Ceacam9. The neo and tk expression cassettes used for the selection of homologous recombinants are shown as open boxes. Arrows indicate their transcriptional directions. The vector sequence within the targeting plasmid is shown as a thin line at the 3′ end of the tk gene. The expected sizes of the DNA fragments obtained were 23 kb after digestion with HindIII for the wild-type allele and 13.5 and 10 kb after digestion with both probes, which are located 5′ and 3′ of the targeting construct, respectively, for the correctly targeted allele. B, BamHI; E, EcoRI; H, HindIII; K, KpnI. (b) Southern blot analyses of DNA isolated from tail biopsies obtained from the progeny of a mating of Ceacam9+/− parents. The DNAs were digested with HindIII and hybridized with a genomic probe 5′ of the Ceacam9 sequence present in the targeting vector. The blot was rehybridized with a probe from the 3′-flanking region. To exclude additional nonhomologous integration events of the targeting construct, the blot was hybridized with the whole HindIII-linearized 32P-labeled pGK-neotk vector as a probe, which did not reveal additional hybridizing fragments apart from the 10-kb HindIII DNA fragment. The sizes of the hybridizing DNA fragments are in the right margin. (c) Northern blot analysis of total RNA isolated from days 9.5, 10.5, and 12.5 p.c. placentae of wild-type (+/+) and day 10.5 p.c. placentae of Ceacam9−/− mice (−/−). The same filter was sequentially hybridized with 32P-labeled Ceacam9 and β-actin cDNA probes. The mobilities of the 28S and 18S ribosomal RNAs are shown.

In situ hybridization.

Placentae and embryos collected on day 8.5 of development of Ceacam9−/− mice and wild-type controls were frozen in Tissue Freezing medium (Jung) diluted 1:1 with water. Seven-micrometer cryosections were placed on SuperFrost/Plus microscope slides (Roth). In situ hybridization with digoxigenin-labeled sense and antisense RNA probes was performed as described before (46, 58). The RNA probes for the detection of transcripts of the marker genes 4311 (750 bp) and PL-I (800 bp) are described elsewhere (4, 26).

Blastocyst transfer and genetic backcross to C57BL/6 mice.

BALB/c Ceacam9−/− mice and, as a control, Ceacam9+/+ mice were mated overnight, and the day of the vaginal plug was designated day 0.5 of gestation. Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane (Forene; Abbott) and sacrificed by cervical dislocation on day 3.5 p.c. Blastocysts were flushed out from the uterus by using M2 medium (Sigma) with 10% FCS. Compacted morulae were collected, washed in M2–10% FCS, and cultured at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2 in M16 medium until they were transferred into day 2.5 p.c. pseudopregnant C57BL/6 foster mothers. The mice were killed by cervical dislocation 13 days after blastocyst transfer, and fetuses were dissected from the uteri and inspected for the presence of abnormalities.

Alternatively, male BALB/c Ceacam9−/− mice (H-2d/d) were mated with female C57BL/6 Ceacam9+/+ mice (H-2b/b). Resulting double heterozygous (Ceacam9+/−/H-2b/d) male mice were backcrossed with BALB/c Ceacam9−/− females. The haplotype of the littermates was determined by PCR and restriction endonuclease digestion of the resulting product (37).

RESULTS

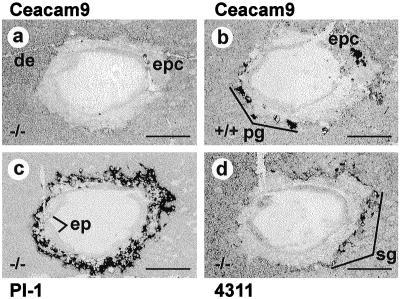

Generation of CEACAM9-null mice. A targeting vector was constructed using isogenic DNA from the Ceacam9 cosmid cosC3 (8) for inactivation of the Ceacam9 gene in the BALB/c ES cell line BALB/c-I. In the resulting vector, exon 1 (which comprises the start codon), intron 1, and two-thirds of exon 2 were replaced by a neomycin gene expression cassette (Fig. 1A). This construct should yield a null allele after homologous recombination. An HSV-tk expression unit was added to the 3′ end of the construct to allow selection against random integration events. After transfer of the linearized targeting vector by electroporation, homologous recombination was observed at a frequency of 12% (16 of 130) in G418 and FIAU double-resistant ES cell colonies. This was inferred from hybridization of a 13-kb genomic HindIII DNA fragment in addition to the 23-kb wild-type fragment with probes from the 5′ and 3′ regions of the Ceacam9 gene (Fig. 1A; data not shown). Two ES cell clones (2C3, 2D7) were used for microinjection into C57BL/6 × DBA blastocysts. Only clone 2D7 exhibited germ line transmission. Mice heterozygous for the knockout allele were identified by allele-specific PCR and were interbred. The offspring were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization with probes from the 5′- and 3′-flanking regions of Ceacam9 (Fig. 1B). The results obtained with both probes confirmed that correct homologous recombination occurred at the Ceacam9 locus. No additional integration events of the targeting construct could be detected using a neo probe (Fig. 1B). To examine the effect of the replacement mutation on Ceacam9 expression, total RNA from day 10.5 p.c. placentae of Ceacam9−/− mice was analyzed by Northern blotting. No full-length or truncated Ceacam9 transcripts could be detected (Fig. 1C). It is known that Ceacam9 expression is restricted to a subset of primary and secondary trophoblast giant cells of the placenta (Fig. 2b) (8). In situ hybridizations were performed with day 8.5 p.c. placentae from Ceacam9−/− mice and wild-type littermates to rule out loss of this cell population during tissue preparation for Northern blot analyses. Again, no Ceacam9 mRNA was found in placentae of Ceacam9−/− mice (Fig. 2a), while transcripts of the trophoblast marker genes PL-I and 4311 could be identified (Fig. 2c and d). These results indicated successful disruption of Ceacam9.

FIG. 2.

Analysis of trophoblast marker gene expression in placentae from wild-type and Ceacam9−/− mice by in situ hybridization. Placentae from wild- type (+/+) and homozygous mutant (−/−) mice were isolated day 8.5 p.c., cryosectioned, and hybridized with digoxigenin-labeled antisense RNA probes. Specifically binding RNA was visualized after incubation with anti-digoxigenin antibodies coupled with alkaline phosphatase using NBT-BCIP (nitroblue tetrazolium–5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate) as a chromogenic substrate. No labeling was observed with sense probes (data not shown). The probes used are indicated above and below the panels. Bars, 0.5 mm. De, decidua; ep, embryo proper; epc, ectoplacental cone; pg, primary giant trophoblast cells; sg, secondary giant trophoblast cells.

Phenotypic analyses of Ceacam9−/− mice.

Genotype analyses of 200 offspring resulting from the mating of Ceacam9+/− mice revealed a nearly Mendelian distribution of the various genotypes (Ceacam9+/+, 29%; Ceacam9−/−, 23%). No obvious morphological or behavioral abnormalities were observed in Ceacam9−/− mice. They exhibited the same weight gain and fertility as their heterozygous or wild-type littermates on both BALB/c and 129/Sv backgrounds (data not shown). Furthermore, histological analyses of the placentae and fetuses between days 10.5 and 16.5 p.c. using paraffin-embedded sections did not reveal morphological differences. In addition, the expression pattern of the placental marker genes PL-I and 4311, which are expressed in primary and secondary trophoblast giant cells and spongiotrophoblast cells and their precursors, respectively, was unchanged (Fig. 2c and d and data not shown).

Ceacam9 is not essential for allogeneic pregnancies.

Since members of the CEA family which are specifically expressed in trophoblast cells are suspected of being involved in the protection of the allotypic fetus from the maternal immune system, the survival of Ceacam9−/− embryos was analyzed in allogeneic and semiallogeneic mothers. BALB/c Ceacam9−/− or Ceacam9+/+ blastocysts (H-2d) were transferred into C57BL/6 foster mothers (H-2b) with a wild-type Ceacam9 genotype. Both transfers yielded normal embryos with comparable efficiencies (Table 1), which indicates that fetal expression of CEACAM9 is dispensable for the maintenance of allotypic pregnancies. In order to evaluate whether maternally expressed CEACAM9 contributes to the survival of semiallotypic embryos or Ceacam9−/− embryos suffer from competition by Ceacam9-positive embryos, Ceacam9−/− BALB/c females (H-2d/d) were first mated with Ceacam9+/+ C57BL/6 males (H-2b/b). Resulting Ceacam9+/− males (H-2b/d) (C57BL/6 × BALB/c Ceacam9−/−) were crossed with Ceacam9−/−/H-2d/d BALB/c females, and offspring were genotyped 3 weeks after birth. Mice with all possible genotypes were born at similar frequencies (H-2d/d/Ceacam9+/−, five offspring; H-2b/d/Ceacam9+/−, five offspring; H-2d/d/Ceacam9−/−, seven offspring; H-2b/d/Ceacam9−/−, eight offspring), which excludes a major role of CEACAM in the tolerance of semiallogeneic embryos.

TABLE 1.

Survival of allogeneic BALB/c Ceacam9−/− embryos (H-2d) in C57BL/6 Ceacam9+/+ foster mothers (H-2b)

| Genotype of transferred blastocysts | No. of transferred blastocytes (no. of foster mothers) | No. of viable embryos 13 days after transfer | No. of resorbed embryos |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ceacam9−/− | 20 (2) | 12 (60%) | 2 |

| Ceacam9+/+ | 12 (1) | 4 (30%) | 3 |

DISCUSSION

The results presented here clearly demonstrate that Ceacam9 is dispensable for the development, adult life, and reproduction of mice on a BALB/c and BALB-c-129/Sv mixed background kept under non-pathogen-free laboratory conditions despite its high degree of conservation among rodents. Furthermore, transfer experiments with allotypic Ceacam9−/− embryos as well as backcrosses leading to semiallotypic pregnancies did not reveal an essential function of Ceacam9 in the protection of the fetal allograft from the maternal immune system. Multiple mechanisms have been suggested to explain the phenomenon of maternal tolerance toward the semiallogeneic fetus in mammals. Transient specific T-cell tolerance to paternal alloantigens and a biased expression of TH2 cytokines during pregnancy are thought to play a role in this process (52, 57). Furthermore, the lack of classical major histocompatibility complex class I molecules on fetal trophoblast cells which are in intimate contact with maternal blood has been implicated in the ignorance of paternal antigens expressed by the fetus (21, 39). In addition, it has been proposed that Fas ligand molecules present on trophoblast cells contribute to the immune privilege of the placenta by inducing apoptosis via Fas receptors on maternal lymphocytes reactive against fetal antigens (17, 19). It has been demonstrated recently by forced expression of major histocompatibility complex class I in placenta and genetic disruption of Fas-mediated cell death, however, that neither of the latter two mechanisms or a combination of the two is sufficient to abolish maternal tolerance in mice (41). Taken together, these results imply that several nonessential mechanisms contribute either incrementally to materno-fetal tolerance or highly redundant processes secure the positive outcome of mammalian pregnancies.

Preliminary experiments using CEACAM9–human IgG-Fc fusion proteins indicate the presence of putative CEACAM9 receptors in the decidua (Finkenzeller and Zimmermann, unpublished results). The maternal part of the placenta, therefore, probably represents the target tissue of secreted CEACAM9. This could imply that CEACAM9 directly influences the maternal system to achieve favorable physiological conditions for the fetus. On the other hand, CEACAM9 and its putative receptor could be players in the maternal-fetal and paternal conflict postulated by Haig (10), in which the CEACAM9 receptor could function as a molecular sink to reduce the amounts of the fetally expressed CEACAM9, which possibly promotes fetal growth at the mother's expense. This would prevent excessive drainage of maternal resources. Knocking out one of the redundant arms produced during the materno-fetal “arms race” in evolution would, therefore, show no or only a marginal phenotype. If this assumption were true, one would expect that overexpression of CEACAM9 rather than loss of function would exhibit an effect on fetal development.

Alternatively, the viability and fertility of Ceacam9 null mutants could be due to compensatory effects exerted by the PSGs, which are also predominantly expressed by trophoblast cells. This appears unlikely, however, because of the unique structure and spatio-temporal expression pattern of Ceacam9. In addition, the uniqueness of Ceacam9 is supported by the fact that it is separated by 2 centimorgans from the Psg gene cluster on chromosome 7, which consists of about 15 tightly linked and coordinately expressed genes (22, 40, 43, 50; W. Zimmermann, unpublished results). However, functional replacement of Ceacam9 by Psg genes can only be rigorously proven or excluded by deletion of the closely related Psg genes, e.g., by chromosomal engineering (38).

In conclusion, the lack of an obvious phenotype suggests that the evolutionarily young family of Ceacam genes does not serve an essential role but arose in order to achieve optimization of a function which is important for competitiveness under natural conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ernst-Martin Füchtbauer for suggestion of the allogeneic backcross experiment and Martina Weiss for excellent technical help. The gift of the placental marker plasmids which were obtained from Janet Rossant and Daniel Linzer through Reinald Fundele is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was supported by the Mildred-Scheel-Stiftung für Krebsforschung.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beauchemin N, Draber P, Dveksler G, Gold P, Gray-Owen S, Grunert F, Hammarström S, Holmes K V, Karlson A, Kuroki M, Lin S H, Lucka L, Najjar S M, Neumaier M, Öbrink B, Shively J E, Skubitz K M, Stanners C P, Thomas P, Thompson J A, Virji M, von Kleist S, Wagener C, Watt S, Zimmermann W. Redefined nomenclature for members of the carcinoembryonic antigen family. Exp Cell Res. 1999;252:243–249. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bohn H, Weinmann E. [Immunological disruption of implantation in monkeys with antibodies to human pregnancy specific beta 1-glycoprotein (SP1) (author's translation).] Arch. Gynakol. 1974;217:209–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02570647. . (In German.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen T, Grunert F, Medina-Marino A, Gotschlich E C. Several carcinoembryonic antigens (CD66) serve as receptors for gonococcal opacity proteins. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1557–1564. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colosi P, Talamantes F, Linzer D I. Molecular cloning and expression of mouse placental lactogen I complementary deoxyribonucleic acid. Mol Endocrinol. 1987;1:767–776. doi: 10.1210/mend-1-11-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dveksler G S, Pensiero M N, Cardellichio C B, Williams R K, Jiang G S, Holmes K V, Dieffenbach C W. Cloning of the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) receptor: expression in human and hamster cell lines confers susceptibility to MHV. J Virol. 1991;65:6881–6891. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.12.6881-6891.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eidelman F J, Fuks A, DeMarte L, Taheri M, Stanners C P. Human carcinoembryonic antigen, an intercellular adhesion molecule, blocks fusion and differentiation of rat myoblasts. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:467–475. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.2.467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ergün S, Kilic N, Ziegeler G, Hansen A, Nollau P, Götze J, Wurmbach J-H, Horst A, Weil J, Fernando M, Wagener C. CEA-related cell adhesion molecule 1: a potent angiogenic factor and a major effector of vascular endothelial growth factor. Mol Cell. 2000;5:311–320. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finkenzeller D, Kromer B, Thompson J, Zimmermann W. cea5, a structurally divergent member of the murine carcinoembryonic antigen gene family, is exclusively expressed during early placental development in trophoblast giant cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31369–31376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.50.31369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray-Owen S D, Dehio C, Haude A, Grunert F, Meyer T F. CD66 carcinoembryonic antigens mediate interactions between Opa-expressing Neisseria gonorrhoeae and human polymorphonuclear phagocytes. EMBO J. 1997;16:3435–3445. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haig D. Genetic conflicts in human pregnancy. Oxf Rev Reprod Biol. 1993;68:495–532. doi: 10.1086/418300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hammarström S. The carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) family: structures, suggested functions and expression in normal and malignant tissues. Semin Cancer Biol. 1999;9:67–81. doi: 10.1006/scbi.1998.0119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammarström S, Olsen A, Teglund S, Baranov V. The nature and expression of the human CEA family. In: Stanners C P, editor. Cell adhesion and communication mediated by the CEA family. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hashino J, Fukuda Y, Oikawa S, Nakazato H, Nakanishi T. Metastatic potential of human colorectal carcinoma SW1222 cells transfected with cDNA encoding carcinoembryonic antigen. Clin Exp Metastasis. 1994;12:324–328. doi: 10.1007/BF01753839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hau J, Gidley-Baird A A, Westergaard J G, Teisner B. The effect on pregnancy of intrauterine administration of antibodies against two pregnancy-associated murine proteins: murine pregnancy-specific beta 1-glycoprotein and murine pregnancy-associated alpha 2-glycoprotein. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1985;44:1255–1259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh J T, Luo W, Song W, Wang Y, Kleinerman D I, Van N T, Lin S H. Tumor suppressive role of an androgen-regulated epithelial cell adhesion molecule (C-CAM) in prostate carcinoma cell revealed by sense and antisense approaches. Cancer Res. 1995;55:190–197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J, Hardy J D, Sun Y, Shively J E. Essential role of biliary glycoprotein (CD66a) in morphogenesis of the human mammary epithelial cell line MCF10F. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:4193–4205. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.23.4193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt J S, Vassmer D, Ferguson T A, Miller L. Fas ligand is positioned in mouse uterus and placenta to prevent trafficking of activated leukocytes between the mother and the conceptus. J Immunol. 1997;158:4122–4128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ilantzis C, Jothy S, Alpert L C, Draber P, Stanners C P. Cell-surface levels of human carcinoembryonic antigen are inversely correlated with colonocyte differentiation in colon carcinogenesis. Lab Investig. 1997;76:703–716. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang S P, Vacchio M S. Multiple mechanisms of peripheral T cell tolerance to the fetal “allograft.”. J Immunol. 1998;160:3086–3090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kammerer R, Hahn S, Singer B B, Luo J S, von Kleist S. Biliary glycoprotein (CD66a), a cell adhesion molecule of the immunoglobulin superfamily, on human lymphocytes: structure, expression and involvement in T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3664–3674. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3664::AID-IMMU3664>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kovats S, Main E K, Librach C, Stubblebine M, Fisher S J, DeMars R. A class I antigen, HLA-G, expressed in human trophoblasts. Science. 1990;248:220–223. doi: 10.1126/science.2326636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kromer B, Finkenzeller D, Wessels J, Dveksler G, Thompson J, Zimmermann W. Coordinate expression of splice variants of the murine pregnancy-specific glycoprotein (PSG) gene family during placental development. Eur J Biochem. 1996;242:280–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0280r.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuijpers T W, Hoogerwerf M, van der Laan L J, Nagel G, van der Schoot C E, Grunert F, Roos D. CD66 nonspecific cross-reacting antigens are involved in neutrophil adherence to cytokine-activated endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1992;118:457–466. doi: 10.1083/jcb.118.2.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunath T, Ordonez-Garcia C, Turbide C, Beauchemin N. Inhibition of colonic tumor cell growth by biliary glycoprotein. Oncogene. 1995;11:2375–2382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laird P W, Zijderveld A, Linders K, Rudnicki M A, Jaenisch R, Berns A. Simplified mammalian DNA isolation procedure. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4293. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.15.4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lescisin K R, Varmuza S, Rossant J. Isolation and characterization of a novel trophoblast-specific cDNA in the mouse. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1639–1646. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.12a.1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin T M, Halbert S P, Spellacy W N. Measurement of pregnancy-associated plasma proteins during human gestation. J Clin Investig. 1974;54:576–582. doi: 10.1172/JCI107794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.MacDonald D J, Scott J M, Gemmell R S, Mack D S. A prospective study of three biochemical fetoplacental tests: serum human placental lactogen, pregnancy-specific beta 1-glycoprotein, and urinary estrogens, and their relationship to placental insufficiency. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;147:430–436. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(16)32239-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mansour S L, Thomas K R, Capecchi M R. Disruption of the proto-oncogene int-2 in mouse embryo-derived stem cells: a general strategy for targeting mutations to non-selectable genes. Nature. 1988;336:348–352. doi: 10.1038/336348a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantzavinos T, Phocas I, Chrelias H, Sarandakou A, Zourlas P A. Serum levels of steroid and placental protein hormones in ectopic pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 1991;39:117–122. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90074-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masson G M, Anthony F, Wilson M S. Value of Schwanger-schaftsprotein 1 (SP1) and pregnancy-associated plasma protein-A (PAPP-A) in the clinical management of threatened abortion. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;90:146–149. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1983.tb08899.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meng F, Lowell C A. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced macrophage activation and signal transduction in the absence of Src-family kinases Hck, Fgr, and Lyn. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1661–1670. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nedellec P, Dveksler G S, Daniels E, Turbide C, Chow B, Basile A A, Holmes K V, Beauchemin N. Bgp2, a new member of the carcinoembryonic antigen-related gene family, encodes an alternative receptor for mouse hepatitis viruses. J Virol. 1994;68:4525–4537. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4525-4537.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumaier M, Paululat S, Chan A, Matthaes P, Wagener C. Biliary glycoprotein, a potential human cell adhesion molecule, is down-regulated in colorectal carcinomas. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10744–10748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.22.10744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Noben-Trauth N, Kohler G, Burki K, Ledermann B. Efficient targeting of the IL-4 gene in a BALB/c embryonic stem cell line. Transgenic Res. 1996;5:487–491. doi: 10.1007/BF01980214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ordonez C, Screaton R A, Ilantzis C, Stanners C. Human carcinoembryonic antigen functions as a general inhibitor of anoikis. Cancer Res. 2000;60:3419–3424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Peng S L, Craft J. PCR-RFLP genotyping of murine MHC haplotypes. BioTechniques. 1996;21:362. doi: 10.2144/96213bm03. , 366–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ramirez-Solis R, Liu P, Bradley A. Chromosome engineering in mice. Nature. 1995;378:720–724. doi: 10.1038/378720a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Redline R W, Lu C Y. Localization of fetal major histocompatibility complex antigens and maternal leukocytes in murine placenta. Implications for maternal-fetal immunological relationship. Lab Investig. 1989;61:27–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rettenberger G, Zimmermann W, Klett C, Zechner U, Hameister H. Mapping of murine YACs containing the genes Cea2 and Cea4 after B1-PCR amplification and FISH-analysis. Chromosome Res. 1995;3:473–478. doi: 10.1007/BF00713961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rogers A M, Boime I, Connolly J, Cook J R, Russell J H. Maternal-fetal tolerance is maintained despite transgene-driven trophoblast expression of MHC class I, and defects in Fas and its ligand. Eur J Immunol. 1998;28:3479–3487. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199811)28:11<3479::AID-IMMU3479>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenberg M, Nedellec P, Jothy S, Fleiszer D, Turbide C, Beauchemin N. The expression of mouse biliary glycoprotein, a carcinoembryonic antigen-related gene, is down-regulated in malignant mouse tissues. Cancer Res. 1993;53:4938–4945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rudert F, Saunders A M, Rebstock S, Thompson J A, Zimmermann W. Characterization of murine carcinoembryonic antigen gene family members. Mamm Genome. 1992;3:262–273. doi: 10.1007/BF00292154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rutherfurd K J, Chou J Y, Mansfield B C. A motif in PSG11s mediates binding to a receptor on the surface of the promonocyte cell line THP-1. Mol Endocrinol. 1995;9:1297–1305. doi: 10.1210/mend.9.10.8544838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sacks G, Sargent I, Redman C. An innate view of human pregnancy. Immunol Today. 1999;20:114–118. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(98)01393-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schaeren-Wiemers N, Gerfin-Moser A. A single protocol to detect transcripts of various types and expression levels in neural tissue and cultured cells: in situ hybridization using digoxigenin-labelled cRNA probes. Histochemistry. 1993;100:431–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00267823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schölzel S, Zimmermann W, Schwarzkopf G, Grunert F, Rogaczewski B, Thompson J. Carcinoembryonic antigen family members CEACAM6 and CEACAM7 are differentially expressed in normal tissues and oppositely deregulated in hyperplastic colorectal polyps and early adenomas. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:595–605. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64764-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soriano P, Montgomery C, Geske R, Bradley A. Targeted disruption of the c-src proto-oncogene leads to osteopetrosis in mice. Cell. 1991;64:693–702. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90499-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stocks S C, Ruchaud-Sparagano M H, Kerr M A, Grunert F, Haslett C, Dransfield I. CD66: role in the regulation of neutrophil effector function. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2924–2932. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stubbs L, Carver E A, Shannon M E, Kim J, Geisler J, Generoso E E, Stanford B G, Dunn W C, Mohrenweiser H, Zimmermann W, Watt S M, Ashworth L K. Detailed comparative map of human chromosome 19q and related regions of the mouse genome. Genomics. 1996;35:499–508. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Swiatek P J, Gridley T. Perinatal lethality and defects in hindbrain development in mice homozygous for a targeted mutation of the zinc finger gene Krox20. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2071–2084. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.11.2071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tafuri A, Alferink J, Moller P, Hammerling G J, Arnold B. T cell awareness of paternal alloantigens during pregnancy. Science. 1995;270:630–633. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5236.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tamsen L, Johansson S G, Axelsson O. Pregnancy-specific beta 1-glycoprotein (SP1) in serum from women with pregnancies complicated by intrauterine growth retardation. J Perinat Med. 1983;11:19–25. doi: 10.1515/jpme.1983.11.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thomas P, Gangopadhyay A, Steele G, Jr, Andrews C, Nakazato H, Oikawa S, Jessup J M. The effect of transfection of the CEA gene on the metastatic behavior of the human colorectal cancer cell line MIP-101. Cancer Lett. 1995;92:59–66. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(95)03764-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Thompson J A, Grunert F, Zimmermann W. Carcinoembryonic antigen gene family: molecular biology and clinical perspectives. J Clin Lab Anal. 1991;5:344–366. doi: 10.1002/jcla.1860050510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Virji M, Watt S M, Barker S, Makepeace K, Doyonnas R. The N-domain of the human CD66a adhesion molecule is a target for Opa proteins of Neisseria meningitidis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:929–939. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.01548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wegmann T G, Lin H, Guilbert L, Mosmann T R. Bidirectional cytokine interactions in the maternal-fetal relationship: is successful pregnancy a TH2 phenomenon? Immunol Today. 1993;14:353–356. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90235-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wessels J, Wessner D, White K, Finkenzeller D, Zimmermann W, Dveksler G S. Pregnancy-specific glycoprotein 18 induces IL-10 expression in murine macrophages. Eur J Immunol. 2000;30:1830–1840. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200007)30:7<1830::AID-IMMU1830>3.0.CO;2-M. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu C, Mao D, Holers V M, Palanca B, Cheng A M, Molina H. A critical role for murine complement regulator crry in fetomaternal tolerance. Science. 2000;287:498–501. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5452.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zimmermann W. The nature and expression of the rodent CEA families: evolutionary considerations. In: Stanners C P, editor. Cell adhesion and communication mediated by the CEA family. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1998. pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar]