Abstract

FePO4 NPs are of special interest in food fortification and biomedical imaging because of their biocompatibility, high bioavailability, magnetic property, and superior sensory performance that do not cause adverse organoleptic effects. These characteristics are desirable in drug delivery as well. Here, we explored the FePO4 nanoparticles as a delivery vehicle for the anticancer drug, doxorubicin, with an optimum drug loading of 26.81% ± 1.0%. This loading further enforces the formation of Fe3+ doxorubicin complex resulting in the formation of FePO4-DOX nanoparticles. FePO4-DOX nanoparticles showed a good size homogeneity and concentration-dependent biocompatibility, with over 70% biocompatibility up to 80 µg/mL concentration. Importantly, cytotoxicity analysis showed that Fe3+ complexation with DOX in FePO4-DOX NPs enhanced the cytotoxicity by around 10 times than free DOX and improved the selectivity toward cancer cells. Furthermore, FePO4 NPs temperature-stabilize RNA and support mRNA translation activity showing promises for RNA stabilizing agents. The results show the biocompatibility of iron-based inorganic nanoparticles, their drug and RNA loading, stabilization, and delivery activity with potential ramifications for food fortification and drug/RNA delivery.

Keywords: Iron phosphate nanoparticles, Doxorubicin, Drug delivery, Drug loading, RNA stabilization, Biocompatible nanoparticles

Introduction

Among various inorganic nanoparticles such as gold, silica, and quantum dots, iron-based nanoparticles (Fe-NPs) are widely explored for biomedical applications like contrast agents, drug delivery vehicles, and thermal-based therapeutics [1–3]. Owing to the magnetic property, high bio-adaptability, and known endogenous metabolism of iron, Fe-NPs are desirable candidates for biomedical applications. As such, Fe-NPs make the majority of FDA-approved inorganic nanomedicine [1, 2]. These include INFeD, DexFerrum, Ferrlecit, Venofer, Feraheme, and Injectafer which are commercially available for their application in iron-deficient anemia and iron deficiency in chronic kidney disease [1]. Similarly, intravenous administration of the chelate iron gluconate is a well-tolerated intervention for anemia [4]. Anemia is one of the most prevalent nutritional deficiency in the world and Fe-based nanoparticles like FePO4 and FeSO4 has been used in food fortification to prevent anemia. Food fortification is the process of adding micronutrients to the food with an aim to overcome the nutritional deficiency in a population [5]. FePO4 NPs are of special interest in food fortification because of their biocompatibility, high bioavailability, and superior sensory performance that do not cause adverse organoleptic effects [6–9]. Perfecto et al. have demonstrated the FePO4 NPs internalization in human intestinal cells occurs primarily through divalent metal transporter-1 (DMT-1) and therefore can be readily absorbed [9, 10]. Iron-based Feridex® and Revosit® are widely used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents for contrast enhanced MRI [11–16]. In light of these outstanding reports, FePO4 NPs present themselves as a good delivery vehicle. Here, we explored FePO4 as a drug-delivery vehicle by loading an anticancer drug, Doxorubicin (DOX). Ferric ion (Fe3+) can form complex with DOX molecule facilitated by electrostatic interaction between electron deficient Fe in FePO4 and electron rich –OH group in DOX to form DOX loaded FePO4 NPs: FePO4-DOX NPs. We evaluated the physicochemical properties of FePO4 and FePO4-DOX NPs and assessed their biocompatibility and cytotoxicity profile, respectively, in mouse osteosarcoma K7M2 and fibroblast NIH/3T3 cell-line.

Along with that, the inorganic nanoparticle has shown promises in nucleic acid stabilization and delivery [17–19]. In this regard, the gold nanoparticle has been widely studied because of their ability to immobilize oligonucleotides in their surface resulting in the prevention of molecular aggregation and degradation [17, 20]. However, gold is not an endogenous element and thereby may limit its translational application. Here, Fe-based nanoparticles like FePO4 nanoparticles can be of prime interest for RNA stabilization study because of their endogenous nature and established biocompatibility profile. There is two proposed mechanism of interaction of nucleic acid (RNA/DNA) with Fe-NPs for the stabilization—(1) formation of hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interaction between the phosphate group of nucleic acid backbone and Fe-NPs resulting in adsorption of nucleic acid in Fe-NPs, and (2) nucleic acid can adsorb to the Fe-NPs surface via nucleotide base pair interaction [19, 21, 22]. A study has shown the potential of calcium phosphate nanoparticles for DNA vaccine stabilization and delivery [23]. In this regard, here we have explored the RNA stabilization and functional activity of another phosphate-based nanoparticle, FePO4, to investigate the multifunctional potential of FePO4 based nanoparticles, in the delivery and stabilization of cargo.

With rapid approval of mRNA vaccine against COVID19, mRNA vaccine nanoparticles are of great interest, RNA being subject to rapid hydrolysis and loss of functional expression, it is incumbent upon the nanoparticle to improve these critical characteristics. Here we show FePO4 NPs stabilize RNA and support functional mRNA translation. Given these excellent characteristics, FePO4 NPs may merit consideration for food fortification, drug, and RNA delivery, opening up exciting biomedical applications.

Results and Discussion

FePO4 NPs Synthesis, Characterization, and Biocompatibility Analysis

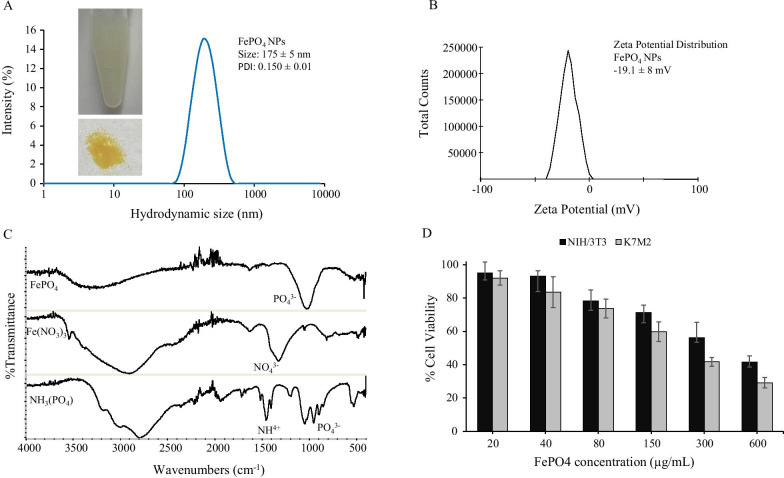

A simple one-step chemical reaction between (NH4)3PO4 and Fe(NO3)3 gives FePO4 as precipitate which is dispersed in biocompatible lipid-PEG surfactant that helps to stabilize FePO4 nanoparticles and prevent aggregation. FePO4 NPs showed a hydrodynamic size of 175 ± 5 nm with a polydispersity index (PDI) of 0.150 ± 0.01 suggesting good particle homogeneity and narrow size distribution. Zeta potential analysis showed a negative surface charge of FePO4 NPs with − 19.1 ± 8 mV zeta potential. The negative surface charge further helps to stabilize particles in colloids thereby preventing protein opsonization, a mechanism that prevents cellular targeting and alters pharmacokinetics [24–26]. FePO4 was further characterized by FTIR. Figure 1c shows the spectral characteristic of FePO4 nanoparticles and their precursor—Fe(NO3)3 and (NH4)3PO4. FePO4 spectra show a distinct sharp peak on 1030 cm−1 which can be attributed to the P–O stretching band, a small peak at 520 cm−1 corresponds to the O–P–O antisymmetric bending, and a broad ranges from 3000 to3500 cm−1 represents water bending and stretching vibrations from adsorbed water molecules [27, 28]. The FePO4 spectra showed the presence of PO43− group and are similar to the FTIR peak reported by other studies thus confirming the formation of FePO4 nanoparticles [27–29]. Fe(NO3)3 spectra showed characteristic peaks for N–O stretching bands at 1326 and 813 cm−1 [30]. Peak at 1625 can be attributed to –OH bending vibration and a broad peak around 3000 cm−1 can be attributed to water bending and stretching vibrations [30]. Likewise, (NH4)3PO4 showed characteristic peaks for the ammonium group around 1500 cm−1 and phosphate group around 1000 cm−1 [31]. The absence of nitrate and ammonium peaks in FePO4 nanoparticles suggest the product is free from possible byproducts and confirms the purity of synthesis.

Fig. 1.

Characterization and biocompatibility of FePO4 nanoparticles. a Hydrodynamic size distribution of FePO4 NPs, b zeta potential measurement of FePO4 NPs showing the surface charge, c FTIR of FePO4 NPs and its precursor-Fe(NO3)3 and (NH4)3PO4, and d biocompatibility of FePO4 NPs on mouse osteosarcoma K7M2 and mouse fibroblast NIH/3T3 cell line. NPs were treated at various concentrations for 48 h (a, b data represents mean ± s.d.; n = 3 replicates. d represents mean ± s.d., n = 6 replicates).

With the assurance of successful synthesis, purity, good size homogeneity, and stable surface charge of FePO4 NPs, we went on to analyze the biocompatibility of FePO4 NPs. For this purpose, we used cancer and non-cancer cells: mouse osteosarcoma K7M2 and mouse fibroblast NIH/3T3 and analyzed the biocompatibility of NPs at a varying concentration in terms of cell viability using MTT assay. FePO4 NPs showed concentration-dependent biocompatibility in both cell lines-K7M2 and NIH/3T3, in the concentration range of 20 to 600 µg/mL (Fig. 1d). FePO4 NPs showed good biocompatibility up to 80 µg/mL concentration with cell viability greater than 70%. Biocompatibility was relatively higher in non-cancer cell NIH/3T3 compared to cancer cell K7M2.

Doxorubicin Loading in FePO4 and Cytotoxicity of FePO4-DOX

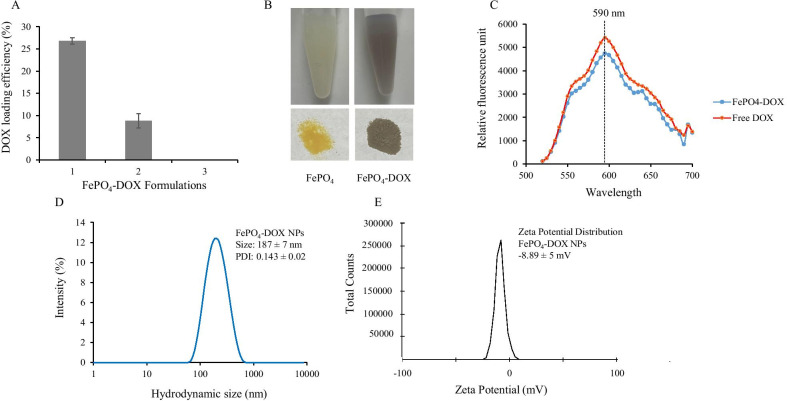

Doxorubicin is loaded in FePO4 through the co-incubation-precipitation method in which doxorubicin solution is mixed with the precursor of FePO4 that results in the formation of DOX loaded FePO4. Three different formulations to load DOX are employed as discussed in the methods. Formulation 1 showed the best loading efficiency of 26.81% ± 1 whereas formulation 2 showed a loading efficiency of 8.83% ± 2 and formulation 3 did not show any loading (Fig. 2a). For loading, we added DOX solution to the precursor Fe(NO3)3 in formulation 1 and to (NH4)3PO4 in formulation 2, whereas, in formulation 3, we added DOX solution to FePO4 NPs directly. The loading data clearly showed that adding DOX to the FePO4 NPs does not retain the DOX whereas adding DOX to either precursor: Fe(NO3)3 and (NH4)3PO4 solution helps in the loading and retention of DOX. This can be explained by the fact that Fe3+ from Fe(NO3)3 can form a complex with the electron-rich oxygen group present in Doxorubicin [32, 33]. The Fe3+-DOX complex is then precipitated by the addition of (NH4)3PO4 resulting in FePO4-DOX, which is characterized by a change of color from faint yellow to faint brown (Fig. 2b). Despite the color change, there was no change in the emission spectra of FePO4-DOX which showed emission maxima at 590 nm similar to that of Free DOX, when excited at 480 nm (Fig. 2c). FePO4-DOX NPs showed a hydrodynamic size of 187 ± 7 nm and PDI of 0.143 ± 0.02, similar to that of FePO4 (Fig. 2d). However, there was a significant difference in the surface charge of FePO4-DOX NPs (-8.89 ± 5 mV), compared to FePO4 NP (-19.1 ± 8 mV) (Fig. 2e). Change in zeta potential suggests functional changes in the surface property of nanoparticles. Here, the reduction of zeta potential from − 19.1 to − 8.89 mV can be attributed to the DOX complexation which adds cationic property in the complex.

Fig. 2.

Doxorubicin (DOX) loading in FePO4 NPs and characterization of FePO4-DOX. a DOX loading efficiency in three different formulations of FePO4 NPs and DOX, b pictorial representation of the change of color from yellow to brown after DOX loading in FePO4 to formulate FePO4-DOX, c emission spectra characterization of DOX loaded FePO4 NPs (FePO4-DOX) after excitation at 480 nm, d hydrodynamic size distribution of FePO4-DOX NPs, and e zeta potential characterization of FePO4-DOX NPs showing surface charge (data represents mean ± s.d.; n = 3 replicates)

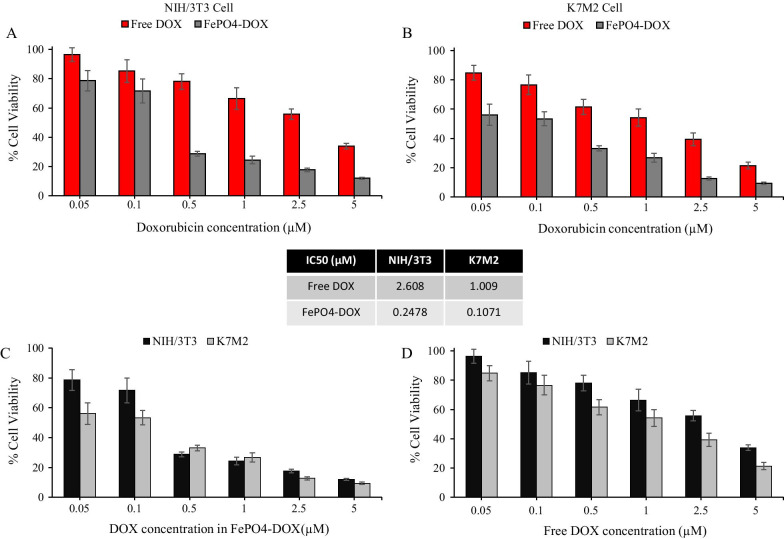

Following the physicochemical characterization, the cytotoxicity of FePO4-DOX was analyzed in K7M2 and NIH/3T3 cells and compared with free DOX (Fig. 3). FePO4-DOX showed higher cytotoxicity compared to Free DOX at equivalent DOX concentration in both cell lines. IC50 value showed around 10 times reduction with FePO4-DOX treatment, from 2.61 to 0.248 µM in NIH/3T3 and 1.01 to 0.107 µM in K7M2 cells. This drastic reduction in IC50 value in both cell lines suggests an enhanced cytotoxicity profile of FePO4-DOX NPs. The equivalent FePO4 concentration in the IC50 concentration range of FePO4-DOX is 40 µg/mL (0.107 µM in K7M2 cells) and 100 µg/mL (0.248 µM in NIH/3T3 cells), which are both within the biocompatible range of FePO4 concentration, with more than 70% cell viability. Hence, the elevation of FePO4-DOX cytotoxicity can be attributed to the Fe3+-DOX complex formation and not to the individual contribution of FePO4 and DOX. Literature has shown the elevated cytotoxic effect of anthracycline like doxorubicin in presence of iron [34–37]. These reports are further supported by the alleviation of Fe-DOX cytotoxicity by the use of iron chelators [35–37]. One proposed mechanism is Fe-DOX complex potentiates the toxicity of DOX-derived reactive oxygen species (ROS) transforming relatively safe ROS (O2·– and H2O2) into much more toxic ROS leading to elevated DNA damage and cell death [34, 36]. Another proposed mechanism is the interaction of DOX with the function of iron regulatory proteins and ferritin in presence of excess Fe thereby affecting iron homeostasis leading to ROS-dependent and independent damage and apoptotic cell death [36, 38].

Fig. 3.

Cytotoxicity of FePO4-DOX NPs. a, b Cytotoxicity of Free Doxorubicin (DOX) and FePO4-DOX NPs in mouse fibroblast NIH/3T3 and osteosarcoma K7M2 cell-line, respectively, at various DOX equivalent concentration. Cytotoxicity was analyzed in percentage cell viability after particle treatment for 48 h. c, d A comparison in percentage cell viability of FePO4-DOX NPs and Free DOX in NIH/3T3 and K7M2 cell lines, respectively, at equivalent DOX concentration. The inset in the middle represents the IC-50 values of Free DOX and FePO4-DOX NPs in NIH/3T3 and K7M2 cells (data represents mean ± s.d.; n = 6 replicates)

Along with the elevated cytotoxicity, FePO4-DOX showed selectivity toward cancer cells with higher cytotoxicity behavior similar to that of Free DOX. Figure 3c shows 0.1 µM DOX equivalent FePO4-DOX showed 53% cell viability for cancer cell K7M2 compared to 72% cell viability for non-cancer NIH/3T3. Likewise, Free DOX also showed higher cytotoxicity behavior toward cancer cells, with 54% cell viability in K7M2 cells compared to 66% in NIH/3T3. However, the differences have increased in the case of FePO4-DOX, with 19% differences in cell viability among cancer and non-cancer cells compared to 12% in Free DOX. Cytotoxicity analysis has shown that Fe complexation with DOX in FePO4-DOX NPs has significantly enhanced the cytotoxicity and improved the selectivity toward cancer cells.

Cellular Internalization of FePO4-DOX NPs

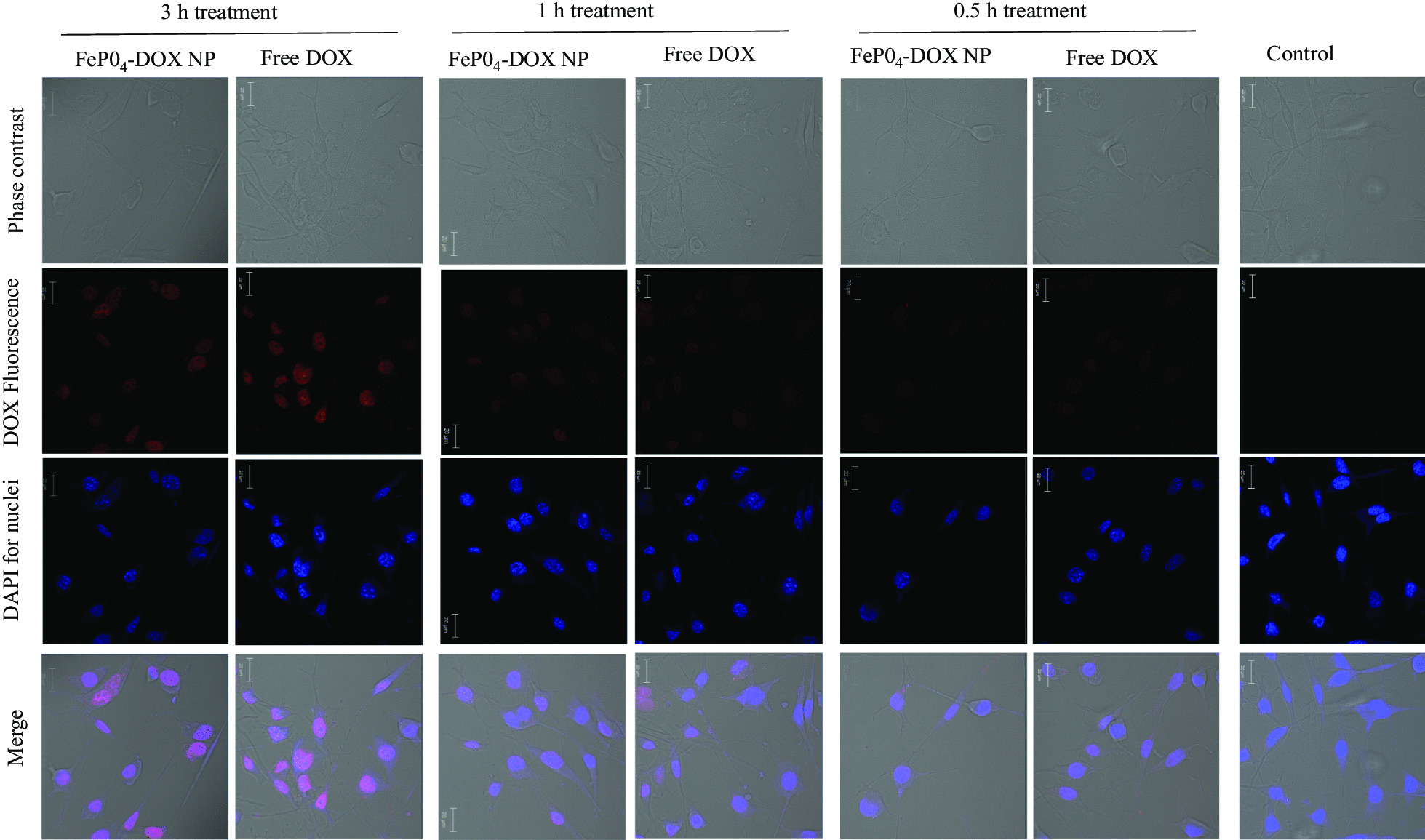

The internalization behavior of FePO4-DOX NPs was analyzed using confocal microscopy following a time-dependent internalization study (Fig. 4). Free DOX was used as a positive control. Both FePO4-DOX NPs and Free DOX did not show significant internalization in the initial 0.5 and 1 h incubation time points. However, at 3 h incubation, both showed internalization as depicted by red DOX fluorescence in the confocal image. The blue color comes from nucleus staining by DAPI. The analysis shows that within 3 h, FePO4-DOX NPs internalize to cells following similar internalization behavior as that of Free DOX. It is important to note that, due to the change of color of FePO4-DOX, which is brownish compared to the red color of Free DOX, we may not quantitatively compare the relative internalization profile of FePO4-DOX. Nonetheless, the internalization assay confirmed that FePO4-DOX is uptake by the cells within 3 h. Given the well-understood mechanism of handling iron by our body, proposed NPs could hold promises in the development of iron-based anticancer therapeutics with an ability to monitor therapeutic response in a single therapy session.

Fig. 4.

Cellular internalization study. Cellular internalization of FePO4-DOX NPs and Free DOX on K7M2 cells after 3 h, 1 h, and 0.5 h treatment. Cells were treated with 200 µL of 5 µg/mL DOX concentration. The red color observed in nanoparticle treated cell line signify successful internalization of the nanoparticles. The red color is due to the fluorescence characteristic of DOX. No red signal is observed in the untreated control cell

RNA Stabilization and mRNA Expression

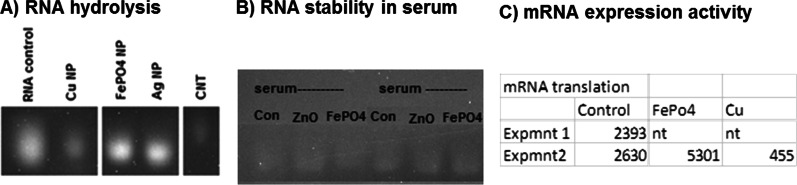

As can be seen in Fig. 5a, whereas copper nanoparticles (Cu NP) and carbon nanotubes (CNTs) accelerate RNA hydrolytic degradation (lower band intensity than control), the FePO4 and control silver (Ag) nanoparticle stabilize the RNA as shown by relatively strong band intensity in RNA agarose gel electrophoresis (RAGE). The FePO4 and control zinc oxide nanoparticle (ZnO NP) also impart some resistance to degradation in serum, as depicted by the band intensity which is slightly higher than controls (Fig. 5b). Importantly the functional activity, mRNA expression is higher than non-nanoparticle controls, whereas the RNA-degrading Cu NP causes loss in mRNA expression as measure by relative light units (Fig. 5c). These results show that FePO4 NPs helps to stabilize RNA and can be used as a stabilizing delivery agent for therapeutic RNA delivery. Earlier preliminary experiments had indicated a normal working range of translation shown are two independent experiments for the control non-nanoparticle treated samples showing 2393 and 2630 RLU/well which is representative. A twofold increase consistent with the above data suggests FePO44 NP supports translation whereas consistent with RNA denaturation/degradation above, the Cu NP suppresses translation. A variety of inorganic nanoparticle systems have been exploited for therapeutic RNA stabilization and delivery including; gold, silver, copper, iron oxide, mesoporous silica nanoparticle (MSN), carbon-based polymers, composites, and others [39–45]. For example our group had reported nanoparticle complexation to macromolecular RNA can cause it to resist degradation by RNase, or nucleases present in serum and tissues. The COVID-19 mRNA vaccine has renewed interest in such macromolecular RNA therapies extending beyond vaccines, where it is incumbent upon the nanoparticle to not only protect RNA from hydrolysis and nuclease-mediated digestion, but complexation to the NP must preserve RNA function, for example, mRNA expression. Previously we had seen copper nanoparticle complexation macromolecular RNA causes RNA denaturation [46] Thus we investigated the effects of NP complexation to macromolecular RNA using Torula yeast RNA (TY-RNA) or a reporter construct mRNA expressing Luciferase.

Fig. 5.

RNA hydrolysis. a A model RNA we have used in a number of our publications similar in size and sequence composition to most mRNAs from torula yeast (TY-RNA) was used. The RNA was incubated in double-distilled water over time in the presence or absence of nanoparticles either copper (Cu NP), iron phosphate (FePO4), silver (Ag NP) or carbon nanotube (CNT) at 37 degrees celcius and samples removed at the same time point and assayed by RNA agarose gel electrophoresis (RAGE). Loss of band staining intensity indicates RNA degradation whereas maintenance of RNA band staining intensity indicates stabilization. b Similar to above, RNA was incubated in 10% FBS/DMEM at room temperature in the presence of zinc oxide (ZnO) NP or FePO4 NP versus control which was RNA alone in the absence of nanoparticle. Again samples were removed over time and assayed by RAGE, presence of the stained RNA band over time again indicates stability and resistance from nuclease or RNase degradation from the serum. c mRNA encoding Luciferase was translated in vitro from standard rabbit reticulocyte and the relative luminescence standardized to RNA in the presence or absence of either iron phosphate (FePO4) or copper (Cu) nanoparticle

Conclusion

FePO4 nanoparticles were successfully synthesized following a simple co-incubation-precipitation technique resulting in the formation of homogenous-sized particles of 175 ± 5 nm. FTIR analysis confirmed the presence of phosphate group and the absence of precursor impurities in the nanoparticle. Biocompatibility analysis revealed concentration-dependent biocompatibility with more than 70% cell viability up to 80 µg/mL. Further, DOX was effectively loaded in FePO4 resulting in FePO4-DOX NPs which showed similar physicochemical properties to that of FePO4. Cytotoxicity analysis revealed that Fe complexation with DOX in FePO4-DOX NPs enhanced the cytotoxicity, with around 10 times improvement in IC50, and improved the selectivity toward cancer cells. Additionally, the internalization assay showed FePO4-DOX NPs were efficiently internalized in cells at a 3 h incubation time point. RNA stabilization study showed that FePO4 nanoparticles efficiently stabilize RNA, prevent rapid degradation, and maintain the functional activity demonstrating promises for delivery of therapeutic RNA. Given the good size homogeneity, biocompatibility range, drug loading efficiency, enhanced cytotoxicity profile, RNA stabilizing property, and efficient cellular uptake, FePO4 NPs showed desirable characteristics for drug and RNA delivery vehicles. Furthermore, the results have shown promising prospects of using FePO4-drug NPs in food fortifications for the development of a food-based drug platform.

Methods

Synthesis and Characterization of FePO4 Nanoparticles

FePO4 nanoparticles were synthesized by chemical precipitation technique optimizing protocol by Sokolova et al. [47]. Briefly, Ammonium phosphate ((NH4)3PO4, 16 mg/mL) and iron nitrate (Fe(NO3)3, 8 mg/mL) solution was prepared. To the 1 mL of Fe(NO3)3, 1 mL of (NH4)3PO4 was added dropwise under constant stirring resulting in precipitation of iron phosphates (FePO4). Excess of (NH4)3PO4 was used so that all Fe from Fe(NO3)3 precipitate as FePO4. Thus formed iron phosphates solution was washed with water 3 times to remove byproducts by centrifuging at 300 g for 2 min. Finally, FePO4 precipitate was dispersed with DSPE-PEG-COOH solution (10% w/w) in water to formulate FePO4 nanoparticles. FePO4 NPs were characterized for size and surface property using dynamic light scattering (DLS) and spectral characteristics using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR).

Doxorubicin (DOX) Loading on FePO4 Nanoparticles

Doxorubicin was loaded in FePO4 nanoparticles by the co-incubation-precipitation method. Three different DOX-FePO4 NPs formulations were explored to optimize the best loading efficiency. In the first formulation, DOX-FePO4 NPs were formulated by adding 100 µg DOX in 1 mL of Fe(NO3)3 (8 mg/mL) followed by the addition of 1 mL of (NH4)3PO4 (16 mg/mL) dropwise under constant stirring. In the second formulations, 100 µg DOX was first added to 1 mL of (NH4)3PO4 (16 mg/mL) followed by the addition of 1 mL of Fe(NO3)3 (8 mg/mL) dropwise under constant stirring. In the third formulations, 100 µg DOX was added to the FePO4 NP solution. Thus formulated FePO4-DOX NPs were washed three times with water and the amount of doxorubicin in FePO4-DOX was quantified spectrofluorimetrically by measuring DOX excitation and emission at 490 nm and 595 nm.

DOX loading efficiency was calculated by the following equation:

Biocompatibility of FePO4 NPs and Cytotoxicity of FePO4-DOX NPs

Biocompatibility of FePO4 NPs and cytotoxicity of FePO4-DOX NPs were assayed in mouse osteosarcoma K7M2 and mouse fibroblast NIH/3T3 using MTT assay following established protocol [48, 49]. Briefly, 10,000 cells were seeded in 96 well plates and incubated for 24 h in a 37 °C 5% CO2 incubator. Then, media was removed and fresh media with varying concentrations of nanoparticles were treated to cells and left for incubation for 48 h. Control cells were maintained with media only. FePO4 NPs concentration ranges from 20 to 600 µg/mL and DOX concentration ranges from 0.05 to 5 µM. After NP incubation, media was removed and cells were incubated with MTT solution (0.5 mg/ml) in serum-free media for 2 h to allow for the formation of formazan crystal. MTT solution was removed and formazan crystal was dissolved in DMSO and left for 15 min at room temperature for proper mixing. Then the absorbance of DMSO solution was measured at 550 nm using a microplate reader (BioTek, Synergy H1 Hybrid Reader) and percentage cell viability was calculated.

Cellular Internalization via Confocal Microscopy

Cellular internalization of FePO4-DOX NPs was analyzed in mouse osteosarcoma K7M2 cells using confocal microscopy [49–51]. Briefly, 12,000 cells were seeded in 8-well plates and incubated for 24 h in 37 °C 5% CO2 incubator. Then, 200 µL of 5 µg/mL DOX concentration in media were treated for 3 h, and cells were fixed with 4% Paraformaldehyde for imaging. The nucleus was stained by DAPI and cells were observed under a Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope (Carl Zeiss, LSM-700). Here, the emission maximum of DOX at 560 nm can be exploited to track its internalization which gives red color in confocal microscopy. Using the same protocol, a time-dependent internalization assay was performed by incubating FePO4-DOX NPs and Free DOX for 0.5, 1, and 3 h respectively.

RNA Stability and Expression

Torula yeast RNA (Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved at 1 mg/ml in sterile deionized water and 2 µg aliquots exposed to 20 ug/mL nanoparticle (CNT, Cu, Ag, ZnO NP or FePO4) incubated at 37 deg C and assayed over time by RNA agarose gel electrophoresis as we have previously reported [42, 52]. Timepoint shown in Fig. 5 is overnight. Similarly, the RNA with/without nanoparticles was exposed to 10% FBS/DMEM and again assayed by RAGE as above. mRNA fLuc was obtained from Trilink Biotechnologies, 2 µl were incubated in rabbit reticuloysate supplemented with Methinine, Cysteine and Leucine (ProMega Corp) for 30 degrees for 1.5 h with or without nanoparticle at 20 μg/ml, standard Luciferin reagent added, and luminescence measurement taken on a Biotek Synergy H1 plate reader under standard conditions.

Statistical Analysis

All data represents at least three independent replicates and expressed as mean ± s.d. whenever possible. Cell viability data includes six replicates.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support from National Science Foundation (NSF Award Number: 2029579).

Authors' Contributions

SA and RD conceived the study and discussed with SR and SW. SR and SW conducted all the experiment in supervision of SA and RD. SR and SA prepared the manuscript. RD finalized RNA part. SA and RD edited the final manuscript with input from all authors. All authors read and approves the final manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sagar Rayamajhi and Sarah Wilson have contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Santosh Aryal, Email: santosharyal@uttyler.edu.

Robert DeLong, Email: robertdelong@ksu.edu.

References

- 1.Mitchell MJ, Billingsley MM, Haley RM, Wechsler ME, Peppas NA, Langer R. Engineering precision nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2021;20:101–124. doi: 10.1038/s41573-020-0090-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bobo D, Robinson KJ, Islam J, Thurecht KJ, Corrie SR. Nanoparticle-based medicines: a review of FDA-approved materials and clinical trials to date. Pharm Res. 2016;33:2373–2387. doi: 10.1007/s11095-016-1958-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguyen VL, Cao MT, Yang Y, Yanqin C, Haibo W, Masayuki N. Synthesis and characterization of Fe-based metal and oxide based nanoparticles: discoveries and research highlights of potential applications in biology and medicine. Recent Pat Nanotechnol. 2013;8:52–61. doi: 10.2174/1872210507666131117183008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Auerbach M, Macdougall I. The available intravenous iron formulations: History, efficacy, and toxicology. Hemodial Int. 2017;21(Suppl 1):S83–S92. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hurrell RF. Preventing iron deficiency through food fortification. Nutr Rev. 1997;55:210–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.1997.tb01608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hilty FM, Arnold M, Hilbe M, Teleki A, Knijnenburg JTN, Ehrensperger F, Hurrell RF, Pratsinis SE, Langhans W, Zimmermann MB. Iron from nanocompounds containing iron and zinc is highly bioavailable in rats without tissue accumulation. Nat Nanotechnol. 2010;5:374–380. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rohner F, Ernst FO, Arnold M, Hilbe M, Biebinger R, Ehrensperger F, Pratsinis SE, Langhans W, Hurrell RF, Zimmermann MB. Synthesis, characterization, and bioavailability in rats of ferric phosphate nanoparticles. J Nutr. 2007;137:614–619. doi: 10.1093/jn/137.3.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.von Moos LM, Schneider M, Hilty FM, Hilbe M, Arnold M, Ziegler N, Mato DS, Winkler H, Tarik M, Ludwig C, Naegeli H, Langhans W, Zimmermann MB, Sturla SJ, Trantakis IA. Iron phosphate nanoparticles for food fortification: Biological effects in rats and human cell lines. Nanotoxicology. 2017;11:496–506. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2017.1314035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perfecto A, Elgy C, Valsami-Jones E, Sharp P, Hilty F, Fairweather-Tait S. Mechanisms of iron uptake from ferric phosphate nanoparticles in human intestinal caco-2 cells. Nutrients. 2017;9:359. doi: 10.3390/nu9040359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanatori I, Kishi F. DMT1 and iron transport. Free Radical Biol Med. 2019;133:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ThanhNguyen TD, Pitchaimani A, Ferrel C, Thakkar R, Aryal S. Nano-confinement-driven enhanced magnetic relaxivity of SPIONs for targeted tumor bioimaging. Nanoscale. 2018;10:284–294. doi: 10.1039/C7NR07035G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morana G, Cugini C, Scatto G, Zanato R, Fusaro M, Dorigo A. Use of contrast agents in oncological imaging: magnetic resonance imaging. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13:350–359. doi: 10.1102/1470-7330.2013.9018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cervadoro A, Cho M, Key J, Cooper C, Stigliano C, Aryal S, Brazdeikis A, Leary JF, Decuzzi P. Synthesis of multifunctional magnetic nanoflakes for magnetic resonance imaging, hyperthermia, and targeting. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2014;6:12939–12946. doi: 10.1021/am504270c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rayamajhi S, Marasini R, Thanh Nguyen TD, Plattner BL, Biller D, Aryal S. Strategic reconstruction of macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles as a magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. Biomater Sci. 2020;8:2887–2904. doi: 10.1039/D0BM00128G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fornasiero D, Bellen JC, Baker RJ, Chatterton BE. Paramagnetic complexes of manganese(II), iron(III), and gadolinium(III) as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. The influence of stability constants on the biodistribution of radioactive aminopolycarboxylate complexes. Investig Radiol. 1987;22:322–327. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bulte JWM, Kraitchman DL. Iron oxide MR contrast agents for molecular and cellular imaging. NMR Biomed. 2004;17:484–499. doi: 10.1002/nbm.924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y, Huo S, Hardie J, Liang X-J, Rotello VM. Progress and perspective of inorganic nanoparticle-based siRNA delivery systems. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2016;13:547–559. doi: 10.1517/17425247.2016.1134486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shu Y, Pi F, Sharma A, Rajabi M, Haque F, Shu D, Leggas M, Evers BM, Guo P. Stable RNA nanoparticles as potential new generation drugs for cancer therapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2014;66:74–89. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Storhoff JJ, Elghanian R, Mirkin CA, Letsinger RL. Sequence-dependent stability of DNA-modified gold nanoparticles. Langmuir. 2002;18:6666–6670. doi: 10.1021/la0202428. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeLong RK, Reynolds CM, Malcolm Y, Schaeffer A, Severs T, Wanekaya A. Functionalized gold nanoparticles for the binding, stabilization, and delivery of therapeutic DNA, RNA, and other biological macromolecules. NSA. 2010;3:53–63. doi: 10.2147/NSA.S8984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghaemi M, Absalan G. Study on the adsorption of DNA on Fe3O4 nanoparticles and on ionic liquid-modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Microchim Acta. 2014;181:45–53. doi: 10.1007/s00604-013-1040-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abarca-Cabrera L, Fraga-García P, Berensmeier S. Bio-nano interactions: binding proteins, polysaccharides, lipids and nucleic acids onto magnetic nanoparticles. Biomater Res. 2021;25:12. doi: 10.1186/s40824-021-00212-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rojas-Sánchez L, Zhang E, Sokolova V, Zhong M, Yan H, Lu M, Li Q, Yan H, Epple M. Genetic immunization against hepatitis B virus with calcium phosphate nanoparticles in vitro and in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2020;110:254–265. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blanco E, Shen H, Ferrari M. Principles of nanoparticle design for overcoming biological barriers to drug delivery. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:941–951. doi: 10.1038/nbt.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suk JS, Xu Q, Kim N, Hanes J, Ensign LM. PEGylation as a strategy for improving nanoparticle-based drug and gene delivery. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2016;99:28–51. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2015.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nandhakumar S, Dhanaraju MD, Sundar VD, Heera B. Influence of surface charge on the in vitro protein adsorption and cell cytotoxicity of paclitaxel loaded poly(ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles. Bull Fac Pharm Cairo Univ. 2017;55:249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.bfopcu.2017.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boonchom B, Puttawong S. Thermodynamics and kinetics of the dehydration reaction of FePO4·2H2O. Physica B. 2010;405:2350–2355. doi: 10.1016/j.physb.2010.02.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palacios E, Leret P, Fernández JF, De Aza AH, Rodríguez MA. Synthesis of amorphous acid iron phosphate nanoparticles. J Nanopart Res. 2012;14:1131. doi: 10.1007/s11051-012-1131-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang F, Su Y, Long Z, Chen G, Yao Y. Enhanced formation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural from glucose using a silica-supported phosphate and iron phosphate heterogeneous catalyst. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2018;57:10198–10205. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b01531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stodt MFB, Gonchikzhapov M, Kasper T, Fritsching U, Kiefer J. Chemistry of iron nitrate-based precursor solutions for spray-flame synthesis. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2019;21:24793–24801. doi: 10.1039/C9CP05007H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vollmer N, Ayers R. Decomposition combustion synthesis of calcium phosphate powders for bone tissue engineering. Int J Self-Propag High-Temp Synth. 2012;21:189–201. doi: 10.3103/S1061386212040073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drechsel H, Fiallo M, Garnier-Suillerot A, Matzanke BF, Schünemann V. Spectroscopic studies on iron complexes of different anthracyclines in aprotic solvent systems. Inorg Chem. 2001;40:5324–5333. doi: 10.1021/ic0002723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jamieson GC, Fox JA, Poi M, Strickland SA. Molecular and pharmacologic properties of the anticancer quinolone derivative vosaroxin: a new therapeutic agent for acute myeloid leukemia. Drugs. 2016;76:1245–1255. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0614-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ichikawa Y, Ghanefar M, Bayeva M, Wu R, Khechaduri A, Prasad SVN, Mutharasan RK, Naik TJ, Ardehali H. Cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin is mediated through mitochondrial iron accumulation. J Clin Investig. 2014;124:617–630. doi: 10.1172/JCI72931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Qin Y, Guo T, Wang Z, Zhao Y. The role of iron in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: recent advances and implication for drug delivery. J Mater Chem B. 2021;9:4793–4803. doi: 10.1039/D1TB00551K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gammella E, Maccarinelli F, Buratti P, Recalcati S, Cairo G. The role of iron in anthracycline cardiotoxicity. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:25. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hershko C, Link G, Tzahor M, Kaltwasser JP, Athias P, Grynberg A, Pinson A. Anthracycline toxicity is potentiated by iron and inhibited by deferoxamine: Studies in rat heart cells in culture. J Lab Clin Med. 1993;122:245–251. doi: 10.5555/uri:pii:002221439390070F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hentze MW, Muckenthaler MU, Andrews NC. Balancing acts: molecular control of mammalian iron metabolism. Cell. 2004;117:285–297. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(04)00343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu D, Wang W, He X, Jiang M, Lai C, Hu X, Xi J, Wang M. Biofabrication of nano copper oxide and its aptamer bioconjugate for delivery of mRNA 29b to lung cancer cells. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;97:827–832. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen W, Glackin CA, Horwitz MA, Zink JI. Nanomachines and other caps on mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug delivery. Acc Chem Res. 2019;52:1531–1542. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Friedman AD, Kim D, Liu R. Highly stable aptamers selected from a 2’-fully modified fGmH RNA library for targeting biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2015;36:110–123. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.08.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reyes-Reveles J, Sedaghat-Herati R, Gilley DR, Schaeffer AM, Ghosh KC, Greene TD, Gann HE, Dowler WA, Kramer S, Dean JM, Delong RK. mPEG-PAMAM-G4 nucleic acid nanocomplexes: enhanced stability, RNase protection, and activity of splice switching oligomer and poly I: C RNA. Biomacromol. 2013;14:4108–4115. doi: 10.1021/bm4012425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jiang S, Eltoukhy AA, Love KT, Langer R, Anderson DG. Lipidoid-coated iron oxide nanoparticles for efficient DNA and siRNA delivery. Nano Lett. 2013;13:1059–1064. doi: 10.1021/nl304287a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumal RR, Abu-Laban M, Hamal P, Kruger B, Smith HT, Hayes DJ, Haber LH. Near-infrared photothermal release of siRNA from the surface of colloidal gold–silver–gold core–shell–shell nanoparticles studied with second-harmonic generation. J Phys Chem C. 2018;122:19699–19704. doi: 10.1021/acs.jpcc.8b06117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnson BJ, Melde BJ, Dinderman MA, Lin B. Stabilization of RNA through absorption by functionalized mesoporous silicate nanospheres. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e50356. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huslig G, Marchell N, Hoffman A, Park S, Choi S-O, DeLong RK. Comparing the effects of physiologically-based metal oxide nanoparticles on ribonucleic acid and RAS/RBD-targeted triplex and aptamer interactions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2019;517:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.06.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sokolova VV, Radtke I, Heumann R, Epple M. Effective transfection of cells with multi-shell calcium phosphate-DNA nanoparticles. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3147–3153. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rayamajhi S, Marchitto J, Nguyen TDT, Marasini R, Celia C, Aryal S. pH-responsive cationic liposome for endosomal escape mediated drug delivery. Colloids Surf B. 2020;188:110804. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.110804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rayamajhi S, Nguyen TDT, Marasini R, Aryal S. Macrophage-derived exosome-mimetic hybrid vesicles for tumor targeted drug delivery. Acta Biomater. 2019;94:482–494. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2019.05.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rayamajhi S, Marasini R, Nguyen TDT, Plattner BL, Biller D, Aryal S. Strategic reconstruction of macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles as a magnetic resonance imaging contrast agent. Biomater Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1039/D0BM00128G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nguyen TDT, Marasini R, Rayamajhi S, Aparicio C, Biller D, Aryal S. Erythrocyte membrane concealed paramagnetic polymeric nanoparticle for contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Nanoscale. 2020;12:4137–4149. doi: 10.1039/D0NR00039F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeLong RK, Dean J, Glaspell G, Jaberi-Douraki M, Ghosh K, Davis D, Monteiro-Riviere N, Chandran P, Nguyen T, Aryal S, Middaugh CR, Chan Park S, Choi S-O, Ramani M. Amino/amido conjugates form to nanoscale cobalt physiometacomposite (PMC) materials functionally delivering nucleic acid therapeutic to nucleus enhancing anticancer activity via Ras-targeted protein interference. ACS Appl Biol Mater. 2020;3:175–179. doi: 10.1021/acsabm.9b00798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.