Abstract

Background

Adolescent and young women (10–24 years old) are habitually a neglected group in humanitarian settings. Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) is an unmet aspect of sexual and reproductive health (SRH) and an additional challenge if lack of hygiene products, inadequate access to safe, clean, and private toilets identified as period poverty. Our objective was to provide an overview of the main MHM issues affecting Venezuelan migrant adolescents and young women in the north-western border of Venezuela-Brazil.

Method

A cross-sectional study was conducted, early in 2021, with the use of a self-responded questionnaire, in Spanish, adapted from the Menstrual Practice Needs Scale (MPNS-36). All identified adolescents and young women aged between 12 and 24 years old were invited to participate (convenience sample-167 women). Women with complete questionnaires and who menstruate were included. Information on access to and quality of hygiene kits and toilets were retrieved, and a descriptive analysis performed, with an evaluation of frequencies for categorical variables (n, %) and mean (± SD-standard deviation) for continuous variables. In addition to the open-ended questions, we included one open question about their personal experience with menstruation.

Results

According to official reports, at the moment of the interviews, there were 1.603 Venezuelans living on the streets in Boa Vista. A total of 167 young women were invited, and 142 further included, mean age was 17.7 years, almost half of the participants who menstruate (46.4%) did not receive any hygiene kits, 61% were not able to wash their hands whenever they wanted, and the majority (75.9%) did not feel safe to use the toilets. Further, menstruation was often described with negative words.

Conclusions

Migrant Venezuelan adolescents and young women have their MHM needs overlooked, with evident period poverty, and require urgent attention. It is necessary to assure appropriate menstrual materials, education, and sanitation facilities, working in partnership among governmental and non-governmental organizations to guarantee menstrual dignity to these young women.

Keywords: Adolescent/young women, Menstrual health, Period poverty, Migrant, Venezuela, Brazil

Plain language summary

Adolescent and young women (10–24 years old) are habitually a neglected group in humanitarian settings (situations of forced displacement, armed conflict, or natural disaster) and, in those contexts, they hardly have access to hygienic menstrual products, safe toilets, or water. This study provides an overview of the menstrual hygiene management issues among Venezuelan adolescents and young migrants living in the northwestern Brazilian border. We found almost half of the participants who menstruate (46.4%) did not receive any hygiene kits, 61% were not able to wash their hands whenever they wanted, and the majority (75.9%) did not feel safe to use the toilets evidencing the period poverty (lack of menstrual supplies, private toilets, sanitation conditions, and education) that affects the wellbeing of these women, especially during humanitarian crisis. Knowing about the Venezuelan adolescent migrant’s menstrual health management issues may help other humanitarian settings to discuss and address those needs, reducing the physical, psychological, and social consequences of menstrual poverty.

Abstract

Contexto

Adolescentes e mulheres jovens (10–24 anos) são frequentemente negligenciadas em contextos humanitários. O manejo da higiene menstrual (MHM) é um aspecto ignorado em saúde sexual e reprodutiva (SSR) e um desafio adicional é a pobreza menstrual: falta de produtos de higiene pessoal, acesso inadequado a banheiros seguros, limpos e privados. Nosso objetivo foi fornecer uma visão geral das principais questões no MHM que afetam adolescentes e mulheres jovens imigrantes venezuelanas na fronteira da Venezuela com o Brasil.

Método

Foi realizado um estudo transversal no qual aplicou-se um questionário autorrespondido, em espanhol, adaptado da “Menstrual Practice Needs Scale” (MPNS-36) em janeiro de 2021, 167 adolescentes e mulheres jovens com idades entre 12 e 24 anos foram convidadas a participar, 142 responderam ao questionário. Os dados obtidos foram inseridos em um Banco de Dados elaborado para o estudo, no programa Excel para Windows e analisados no software SPSS. Foi realizada análise descritiva dos dados, com avaliação de frequências para variáveis categóricas (n, %) e média (± DP-desvio padrão) para variáveis contínuas. Recuperamos as informações de acesso e qualidade dos kits de higiene e realizamos uma análise descritiva. Além das questões de múltipla escolha, incluímos uma questão aberta: “Como é a menstruação para você?”.

Resultados

Segundo informações oficiais, no momento das entrevistas, havia 1.603 venezuelanos vivendo nas ruas de Boa Vista. Foram entrevistadas 142 adolescentes, com média de idade de 17,7 anos, quase metade das participantes que menstruavam (46,4%) não receberam kit de higiene, 61% não conseguiam lavar as mãos quando desejassem e a maioria (75,9%) não se sentia segura para usar o banheiro. Além disso, a menstruação foi frequentemente descrita com palavras negativas.

Conclusões

Adolescentes e mulheres jovens imigrantes venezuelanas têm suas necessidades no MHM negligenciadas, com evidente pobreza menstrual, e requerem atenção urgente. É necessário garantir absorventes, educação e saneamento básico, trabalhando em parceria entre organizações governamentais e não governamentais para garantir a dignidade menstrual a essas jovens.

Background

It is estimated that there are at least 79.5 million people worldwide who have left their homes due to armed conflict, persecution, generalized violence, lack of economic opportunities, or human rights violations [1]. Around half of them are adolescent girls and women of reproductive age [1, 2]. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adolescents as the group aged from 10 to 19 years old [3]. Nevertheless, research concerning adolescents is often extended to include individuals until 24 years old, defined as young adults or Youth, in agreement with contemporary patterns of adolescent growth [4].

Adolescent girls and young women are a neglected group in humanitarian settings [5] and their sexual and reproductive health (SRH) issues are habitually neglected [6]. They have limited knowledge about contraceptive methods, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and are more vulnerable to unplanned pregnancies, leading to increased rates of unsafe abortion, maternal morbidity, and mortality. Gender-based, domestic, and sexual violence is also a key concern among this group [6, 7]. Issues considered trivial in other contexts, are of relevance in vulnerable populations, with important impact on individual wellbeing and healthcare. Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) is an unmet aspect of SRH and can be an additional challenge for displaced adolescents and young women, due to a period poverty: lack of hygiene products, inadequate access to safe, clean, and private toilets that all of them impacting in their health and wellbeing [8–10]

In Latin America, the Venezuelan economic crisis during the last 5 years, led that almost 5.4 million Venezuelans leave the country [11], and it is considered the largest displacement in the history of the region [1, 12]. It was estimated that since 2017 over 455,000 Venezuelans have arrived in Brazil, and of these, about 40,000 currently reside in the city of Boa Vista (the state capital, near to Venezuelan border), representing around 10% of the local population [12, 13]. The Brazilian Government, in collaboration with the United Nation High Commissioner for Refugee (UNHCR), built 13 shelters in the state hosting at early May 2021, 7,175 Venezuelans as transit location waiting for a definitive resettlement in other parts of the country [14].

Due to the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, since March 2020, the Brazilian border with Venezuela was closed [15]; nevertheless, the Venezuelans continue to cross the border through alternative routes [16, 17]. The International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported around 1603 Venezuelans living in tents behind the Roraima’s bus station, including 84 female adolescents (12–17 years old) [16]. Further, MHM is an important issue for migrant women worldwide [4]. Due to the scarce information regarding Venezuelan migrant adolescents about MHM, our aim was to provide an overview of the main MHM issues affecting migrant Venezuelan adolescents and young women in Boa Vista, Roraima, Brazil.

Methods

Study design and study tools

A cross-sectional study was conducted, with the use of a self-responded questionnaire, designed for this study, adapted, and translated into Spanish (the native language of the Venezuelan) from the Menstrual Practice Needs Scale (MPNS-36) [18]. This scale was developed after a literature review about menstrual practices in low-and middle-income countries and was assessed in a pilot survey in Uganda. It is available for download and can be further adapted for different ages and contexts [18, 19]. The questionnaire used in the current study included one open question about menstruation and multiple-choice questions on sociodemographic characteristics (age, ethnicity, cohabitation status, years of schooling, employment, income, place of residence, and migration information), access to and quality of hygiene kits, and toilets. A unique pre-defined identification to each adolescent and young woman was attributed, respecting data confidentiality.

Study participants and sampling

Since 2019, there are hundreds of Venezuelans living in tents behind the Boa Vista bus station. The Brazilian army is responsible for organizing the daily routine at the place, providing food, vaccines, and some hygiene kits. In this place, there are limited non-potable water points among the tents, one place used as restroom, with toilets and showers, and one point adapted for laundry. It is estimated that 1603 Venezuelans non-legally documented are living in that place, including 84 adolescent girls (12–17 years old) [16].

A sample was selected from Venezuelan adolescents and young women living in tents behind the Boa Vista bus station, however those living in UNHCR shelters or in informal non-UN settlements in Boa Vista who attended the St. Agostinho church, a location that provides food and other essential items that migrant needed including hygiene kits under a program managed by UNICEF and CARITAS International, were also included.

A total of 167 adolescents and young women were invited to participate, 153 completed the questionnaire and 142 reported menstruation.

Data collection

The study was conducted in Boa Vista, capital of Roraima state. Due to the epidemiological condition of the Covid-19 pandemic, the research team was not authorized to enter the UNHCR shelters, as initially established and the only allowed places to perform the interviews were informal shelters. The largest one, located at the Boa Vista bus station and at the St. Agostinho church.

Two female healthcare providers (one physician and one nurse) were responsible for the data collection between 18 and 23 January 2021. The team identified young women between 10 and 24 years old (fluent in Spanish and literate) at the informal shelter or the St. Agostinho church and further invited them to participate in the study. A self-responded questionnaire was applied with an average duration of 30 min. Participants did not receive financial compensation.

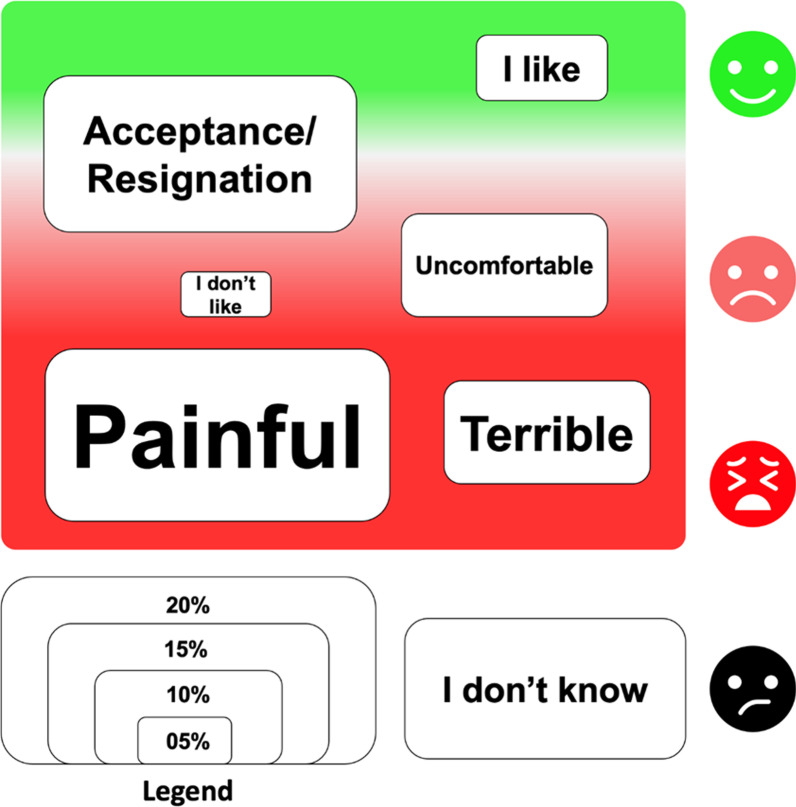

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was performed, the simple distribution was initially performed for numeric variables (using frequency, means, and standard deviations (SD), range, median, and quartiles). There was one open question in the questionnaire, on the women’s personal experience/feeling about menstruation, as: “How is menstruation for you?” The answers were grouped by the frequency of the most used words and analyzed by similarity considering a keyword, from that, a visual representation of the results was created.

Ethical issues

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Campinas, Brazil and all participants signed an informed consent or assent form prior to being interviewed (IRB no. 20458219.0.0000.5404).

For the unaccompanied girls under 18 years of age, a waiver for the need that a responsible adult signed the informed consent form was obtained. The Brazilian regulation for research involving human beings [20] only accepted research without the consent signed for the legal responsible, in case of vulnerable populations [20], understanding that it could add an additional risk for the adolescents when considering questions on SRH issues. Nevertheless, all included young women have signed an assent form and were exhaustively elucidated about the research. The UNHCR and the Roraima State Underage Guardianship Council (Roraima’s Conselho Tutelar) also authorized the study prior to its implementation.

Results

A total of 167 adolescents and young women were invited to participate, 142 (12–24 years old; 85.0%) completed the questionnaire; the age (mean ± SD) was 17.7 (± 3.6). Ten adolescents aged 10–11 years old were excluded because they did not adequately respond, filling out all alternatives in every question, invalidating their analysis and other four (under 18 years old), 11 adolescents were excluded because they reported that they had not yet had menarche and other four (under 18 years old), were also excluded because they were deprived of authorization by their mothers to participate in the study due to the topic related to sexual and reproductive health issues, including menstruation. In relation to housing conditions, the majority (84.5%) was living on the tents behind the Roraima’s bus station, and for most of them (80%) the main source of income since they arrived in Brazil, was donations (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the migrant Venezuelan adolescents and young women interviewed at the Brazilian-Venezuelan border (n = 142), 2021a

| Characteristics of the adolescent (n = 142) | N | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 10–19 | 83 | 58.4 |

| 20–24 | 59 | 41.6 |

| Adolescent younger than 18 years old unaccompanied?b (n = 81) | ||

| Yes | 28 | 34.6 |

| No | 53 | 65.4 |

| Race (n = 142) | ||

| White | 34 | 23.9 |

| Biracial | 60 | 42.3 |

| Black | 24 | 16.9 |

| Asian | 24 | 16.9 |

| Schooling (n = 142)c | ||

| 0–4 years | 46 | 32.4 |

| 5–10 years | 77 | 54.2 |

| 11 or more years | 19 | 13.4 |

| Main reasons for migrating (n = 142) | ||

| Lack of economic opportunities | 101 | 71.1 |

| Insecurity | 12 | 8.5 |

| Hunger | 7 | 4.9 |

| Corruption | 5 | 3.5 |

| Don’t know | 17 | 12.0 |

aMultiple choice questions. Were included all the adolescents and young women who menstruate

bIn Brazil the legal majority is from the age of 18 years old

cCompleted years at school. In South American countries, 0–4 years at school, means they did not finish primary school, 5–9 years means they completed primary school and 10 or more years means they studied until secondary school or more. At the moment of the interview, none of the adolescents was studying

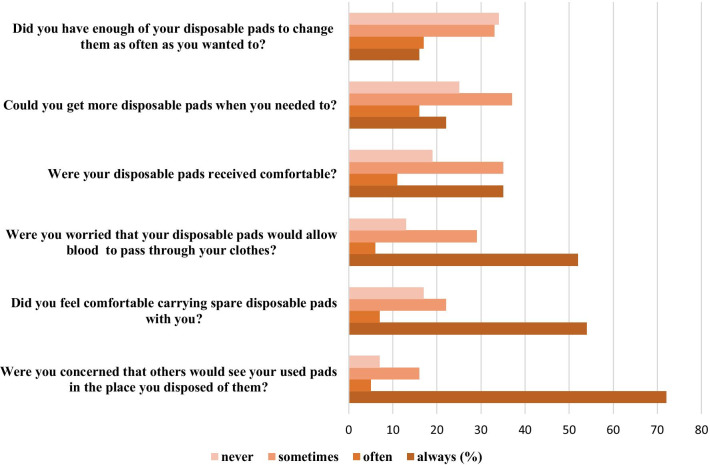

A half of the interviewed females (50%) who menstruate did not receive any hygiene kit since they arrived at Boa Vista (Table 2). In addition, among those who received disposable pads (45%), little more than a half (53.6%) reported that the pads’ material was rarely or never comfortable and there were not distributed in sufficient quantity (33.3%) (Fig. 1). No menstrual caps were distributed in this population.

Table 2.

Access to hygiene kits by migrant Venezuelan adolescents and young women interviewed at the Brazilian-Venezuelan border (n = 153), 2021

| Since arriving at Boa Vista, which items of hygiene have you received?(n = 153) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Disposable sanitary pads | 69 | 45.1 |

| Others hygiene items (soap, shampoo, toothpaste, tooth brush) | 2 | 1.3 |

| None | 71 | 46.4 |

| Haven't had menarch yet | 11 | 7.2 |

| How were hygiene items distributed? (n = 153) | ||

| International Organization for Migration (IOM) | 8 | 5.2 |

| United Nations Population Fund (UNPF) | 5 | 3.3 |

| Caritas | 6 | 3.9 |

| Brazilian army | 8 | 5.2 |

| Other | 6 | 3.9 |

| Don’t know | 37 | 24.2 |

| Didn’t receive | 72 | 47.1 |

| Haven't had menarch yet | 11 | 7.2 |

| Where were the kits distribute? (n = 153) | ||

| Bus station shelter | 46 | 30.1 |

| Caritas Unit | 6 | 3.9 |

| Other | 19 | 12.4 |

| Didn’t receive | 71 | 46.4 |

| Haven't had menarch yet | 11 | 7.2 |

aWere included all the adolescents and young women who menstruate

Fig. 1.

Access to menstrual materials received by the migrant Venezuelan young women at the Brazilian-Venezuelan border. Only the adolescents and young women who received disposable pads answered this section (n = 69)

Concerning the sociocultural concepts about menstruation, one third of the interviewed females do not feel comfortable about carrying pads with them and almost all of them (93.2%) in a certain way were concerned that someone could see the pads in the place where they were disposed (Fig. 1).

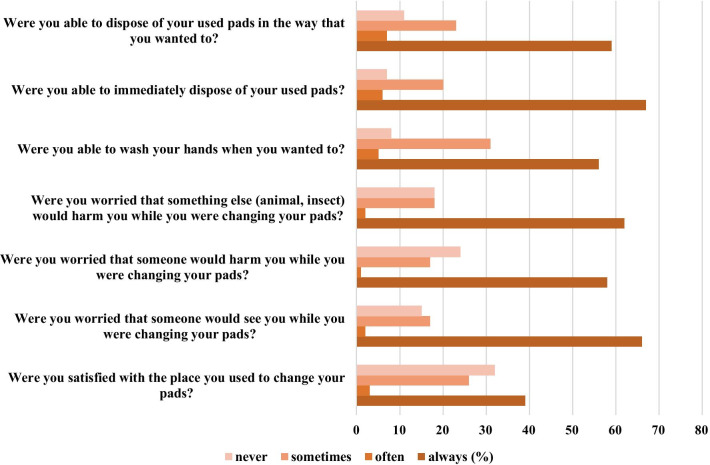

Although the majority (88%) reported they had access to a toilet for changing pads, these places do not offer adequate sanitation conditions, 61% were not able to wash their hands whenever they wanted and did not feel safe to use the toilets. Most of the interviewed women reported, at least sometimes, they were afraid to be harmed by someone (75.9%) or by an animal or insect (82%) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Sanitation conditions regarding MHM among the migrant Venezuelan young women at the Brazilian-Venezuelan border. Were included all the adolescents and young women who menstruate (n = 142)

Regarding the open question (“How is menstruation to you?”), 28 participants (19.7%) did not respond it. Among those who responded, almost a quarter said they did not know, for the others in general the responses about menstruation were often described with negative words as horrible, terrible, bad, or painful. Figure 3 shows the grouping of words in their meanings according to the frequencies in which they appeared.

Fig. 3.

How is menstruation for you? 114 adolescents and young women answered this question

Discussion

Menstrual poverty among the Venezuelan migrant youth in Boa Vista, Brazil was evident: lack of access to adequate menstrual hygiene products, sanitation conditions and toilets.

Less than a half of the interviewed adolescents and young women had received menstrual materials (disposable pads), and for those, one-third reported that the quantity distributed was not enough for a month period. Further, menstrual caps were not allowed in this group of young women. The literature showed that in the lack of appropriate materials, the adolescents and young women handle menstruation with methods that could be unhygienic as reusable old cloth, tissue paper, leaves, wool pieces, or cotton [10, 21, 22]; this could cause discomfort, irritation, and potentially increase the risk of reproductive tract infections (RTI) [22, 23]. In the year 2014, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) reported that 1 out of every 10-menstruating youth miss school during their menstrual cycle due to lack of access to menstrual products and resources. Further, in many developing countries many schools do not have sufficient toilets and when exist they were without adequate privacy and in many cases, they provided poor water, sanitation and hygiene infrastructure [24]. If this situation was described in settings not under humanitarian crisis it is possible to imagine what happens among females living almost on the streets as occurred with the interviewed females.

In addition, it was described that those adolescents and young women in humanitarian settings can suffer sexual exploitation trying to manage their MHM needs [10, 22]. In our study, we observed that the majority of females reported fear and anxiety of leakage of bleeding through the clothes which was also reported in other humanitarian contexts causing psychological and social effects as harassment, isolation, and absenteeism at school [9, 10, 25].

Regarding the access to private toilets and sanitation infrastructure, not all the interviewed youth were able to use the toilets and the majority were unable to wash their hands, acknowledging the negligence already reported previously in MHM in emergency settings [8–10]. The absence of adequate sanitation facilities can increase the risk of sexual violence [22, 26] which was related as a fear by the majority of adolescents and young women in our study.

A stigma or taboo about menstruation in this group of migrants is clear, including the finding of mothers who have deprived their daughters to participate in this research, highlighting the characteristics of this transgenerational taboo, which contributes to the persistence of menstrual poverty [27]. Almost 30% of them did not answer the questions or answered that they did not know what menstruation for them is; moreover, for the others, menstruation was associated either with negative feelings or resignation. This has been described in other studies regardless the nationality, religious, or cultural beliefs [9, 10, 22–25], underlying the needs of education on menstrual and reproductive health with the youth and the communities, so that everyone, including men, would be knowledgeable and comfortable in discussing MHM issues [10, 22, 27].

The interviewed females reported a shortage of menstrual supplies, private toilets, sanitation conditions, and comprehensive information. This situation has been published previously in studies with adolescents and young women in other humanitarian contexts including in low- and middle-income countries; with socio-psychological impacts in quality of life and in reproductive health of this population [22–24, 26]. Regarding the reality in Boa Vista, so far, the Brazilian government does not have a policy to address period poverty. On the latest October 07th, Jair Bolsonaro, Brazilian president vetoed a bill that provided for the distribution of sanitary pads to vulnerable populations. [28]

An international effort to alert and educate about this condition was created by the Alliance for Period Supplies: Period Poverty Awareness Week which took place on the last week of May (24–30) 2021 [29]. This initiative is very important to raise society’ awareness, prompting to pressure governments to develop an educational policy that demystifies menstruation and ensures hygiene kits for adolescents, as has been done in Canada, Australia and New Zealand [30].

In humanitarian settings, the presence of other actors as NGO´s, working in collaboration with governments and community leaders is also very important to educate, advocate, provide adequate sanitation installations and assure access to hygiene kits [31].

This study has some limitations. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic it was not possible to have access to the UNCHR shelters, as initially agreed, consequently the results are almost only from migrants living on the streets. Since a self-responded questionnaire was used, adolescents between 10 and 11 years old were excluded because they did not complete the questionnaires adequately. Also, focus group discussions could be more appropriate to enable more data from the younger adolescents. However, the study strength is that, as far as we know, it is the first report which provides an overview of the status of MHM issues among Venezuelan adolescent migrants.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the migrant Venezuelan adolescents and young women in Boa Vista have their MHM needs overlooked and due to the COVID-19 pandemic they might be more affected since they are living in precarious conditions. Efforts to address the MHM needs from this population require urgent attention.

Despite the COVID-19 pandemic, it is necessary to strengthen the collaboration among NGO’s which are already working in Boa Vista, UNHCR shelters, the Brazilian army and local leaders discussing menstrual health, offering menstrual and hygiene kits, building adequate sanitation with proper water and specific toilets for women and advocating a government policy to address period poverty, in order to guarantee a menstrual dignity to this neglected population.

Acknowledgements

To all the personnel of the United Nation High Commissioner for Refugees and the personnel of CARITAS and UNICEF based in Boa Vista, Roraima and to the personnel of the Brazilian Army, without their help we could not have conducted this research study. We also thank Guilherme de Moraes Nobrega for his collaboration on the presented Fig. 3.

Abbreviations

- IOM

International Organization for Migration

- IRB

Institutional Review Board

- MHM

Menstrual hygiene management

- MPNS-36

Menstrual Practice Needs Scale

- SARS‑CoV‑2

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- SRH

Sexual and reproductive health

- STI

Sexually transmitted infections

- UNESCO

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- UNHCR

United Nation High Commissioner for Refugee

- WHO

World Health Organization

Authors’ contributions

RES, LB and MLC had the initial idea for the study. RES and LR were responsible for data collection. RES, FGS, LB and MLC were responsible for planning the analysis and interpretation of data. RES wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the CEMICAMP, Center for Research in Reproductive Health of Campinas. LR received funding from SRH, part of the UNDP-UNFPA-UNICEFWHO-World Bank Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction (HRP), a cosponsored programme executed by the World Health Organization (WHO), to complete her MSc.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the University of Campinas, Brazil and all participants signed an informed consent or assent form prior to being interviewed (IRB no. 20458219.0.0000.5404).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.UNHCR. Mid-year trends 2020 Trends at a Glance. 2020. https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwjGrfCi0aXvAhVYLLkGHUizA9oQFjADegQIARAD&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.unhcr.org%2F5fc504d44.pdf&usg=AOvVaw04qCNWxh_R5Og1tNbGZlgs. Accessed 11 Mar 2021.

- 2.Christelle Cazabat. Women and girls in internal displacement. UN Women, [Internet]. 2020. 2021. http://www.internationalinspiration.org/women-and-girls-in-internal-displacement. Accessed 11 Mar.

- 3.World Health Organisation (WHO). Health for the World’s Adolescents: a second chance in the second decade. 2014.

- 4.Inter-Agency Working Group on Reproductive Health in Crises (IAWG). Adolescent sexual and reproductive health toolkit for humanitarian settings. 2020. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/IAWG%20Toolkit_Full_compressed.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan 2021. [PubMed]

- 5.Jennings L, George AS, Jacobs T, Blanchet K, Singh NS. A forgotten group during humanitarian crises: a systematic review of sexual and reproductive health interventions for young people including adolescents in humanitarian settings. Confl Health. 2019;13(1):15–17. doi: 10.1186/s13031-019-0240-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ivanova O, Rai M, Kemigisha E. A systematic review of sexual and reproductive health knowledge, experiences and access to services among refugee, migrant and displaced girls and young women in Africa. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(8):1–12. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15081583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Adolescent Girls in Disaster and Conflict. Interventions for Improving Access to Sexual and Reproductive Health Services.2016. https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/UNFPA. Accessed 11 Mar 2021.

- 8.Schmitt ML, Wood OR, Clatworthy D, Rashid SF, Sommer M. Innovative strategies for providing menstruation-supportive water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities: learning from refugee camps in Cox’s bazar, Bangladesh. Confl Health. 2021;15(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13031-021-00346-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemigisha E, Rai M, Mlahagwa W, Nyakato VN, Ivanova O. A qualitative study exploring menstruation experiences and practices among adolescent girls living in the nakivale refugee settlement, Uganda. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(18):1–11. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17186613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.VanLeeuwen C, Torondel B. Exploring menstrual practices and potential acceptability of reusable menstrual underwear among a middle eastern population living in a refugee setting. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:349–360. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S152483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Venezuela situation. 2021. https://www.unhcr.org/venezuelaemergency.html?query=venezuela. Accessed 05 Jan 2021.

- 12.Inter-Agency Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V). Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan January–December 2021. https://rmrp.r4v.info/.

- 13.United Nations Refugee Agency. Venezuela Situation responding to the needs of people displaced from Venezuela. 2019. https://www.unhcr.org/5ab8e1a17.pdf. Accessed 11 Mar 2021.

- 14.UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). Profile of shelters in Roraima. https://app.powerbi.com/view?r=eyJrIjoiZTRhOWVlOTgtYTk2MS00YmY3LWEyY2YtMGM1Y2MzODFjMmVjIiwidCI6ImU1YzM3OTgxLTY2NjQtNDEzNC04YTBjLTY1NDNkMmFmODBiZSIsImMiOjh9. Accessed 07 May 2021

- 15.Brazilian Goverment. PORTARIA No. 125, DE 19 DE MARÇO DE 2020.

- 16.International Organization for Migration. Homeless Venezuelan Population in Boa Vista. 2021. https://www.iom.int/news/iom-launches-report-indigenous-migration-venezuela-brazil. Accessed 07 May 2021.

- 17.Baeninger R, Belmonte N, Jóice De Oliveira D, Domeniconi S, Duval C, João F, et al. Observatório das Migrações em São Paulo. Observatório das Migrações Internacionais no Estado de Minas Gerais, Migrações Venezuelanas. 2020. https://www.nepo.unicamp.br/publicacoes/livros/mig_venezuelanas/migracoes_venezuelanas.pdf. Accessed 11 Mar 2021.

- 18.Hennegan J, Nansubuga A, Smith C, Redshaw M, Akullo A, Schwab KJ. The menstrual practice needs scale (MPNS-36) BMJ Open. 2020;10:1–2. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hennegan J, Nansubuga A, Smith C, Redshaw M, Akullo A, Schwab KJ. Measuring menstrual hygiene experience: development and validation of the Menstrual Practice Needs Scale (MPNS-36) in Soroti, Uganda. BMJ Open. 2020;10(2):e034461. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brazil. Resolution No. 466, December 12, 2012. 2012.

- 21.Chandra-Mouli V, Patel SV. Mapping the knowledge and understanding of menarche, menstrual hygiene and menstrual health among adolescent girls in low- and middle-income countries. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sommer M, Schmitt M, Clatworthy D. Menstrual Hygiene Management (MHM) Into Humanitarian Response the Full Guide. 2017;91. www.elrha.org. https://www.wsscc.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/12/The-MHM-Toolkit-Full-Guide.pdf.

- 23.Kaur R. Menstrual hygiene, management, and waste disposal: practices and challenges faced by girls/women of developing countries. J Environ Public Health. 2018;2018:1730964. doi: 10.1155/2018/1730964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). Teaching and learning: achieving quality for all. 2014. https://www.heart-resources.org/doc_lib/teaching-and-learning-achieving-quality-for-all/. Accessed 07 Jul 2021.

- 25.Crichton J, Okal J, Kabiru CW, Zulu EM. Emotional and psychosocial aspects of menstrual poverty in resource-poor settings: a qualitative study of the experiences of adolescent girls in an informal settlement in Nairobi. Health Care Women Int. 2013;34(10):891–916. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2012.740112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vanleeuwen C, Torondel B. Improving menstrual hygiene management in emergency contexts: literature review of current perspectives. Int J Womens Health. 2018;10:169–186. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S135587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shannon AK, Melendez-Torres GJ, Hennegan J. How do women and girls experience menstrual health interventions in low- and middle-income countries? Insights from a systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. Cult Health Sex. 2020;23(5):624–643.27. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2020.1718758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/oct/11/bolsonaro-blocks-free-tampons-and-pads-for-disadvantaged-women-in-brazil. [Internet]. 2021. Accessed 22 Oct 2021.

- 29.Alliance for periods supplies. Period Poverty Awareness Week [Internet]. 2021. https://www.allianceforperiodsupplies.org/period-poverty-awareness-week. Accessed 08 Jun 2021.

- 30.Wall LL. Period poverty in public schools: a neglected issue in adolescent health. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):315–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), Guidance on Menstrual Health and Hygiene. 2019.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.