Abstract

Background

Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists can be used to prevent a luteinizing hormone (LH) surge during controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) without the hypo‐oestrogenic side‐effects, flare‐up, or long down‐regulation period associated with agonists. The antagonists directly and rapidly inhibit gonadotrophin release within several hours through competitive binding to pituitary GnRH receptors. This property allows their use at any time during the follicular phase. Several different regimens have been described including multiple‐dose fixed (0.25 mg daily from day six to seven of stimulation), multiple‐dose flexible (0.25 mg daily when leading follicle is 14 to 15 mm), and single‐dose (single administration of 3 mg on day 7 to 8 of stimulation) protocols, with or without the addition of an oral contraceptive pill. Further, women receiving antagonists have been shown to have a lower incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Assuming comparable clinical outcomes for the antagonist and agonist protocols, these benefits would justify a change from the standard long agonist protocol to antagonist regimens. This is an update of a Cochrane review first published in 2001, and previously updated in 2006 and 2011.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists compared with the standard long protocol of GnRH agonists for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in assisted conception cycles.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Register (searched from inception to May 2015), the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library, inception to 28 April 2015), Ovid MEDLINE (1966 to 28 April 2015), EMBASE (1980 to 28 April 2015), PsycINFO (1806 to 28 April 2015), CINAHL (to 28 April 2015) and trial registers to 28 April 2015, and handsearched bibliographies of relevant publications and reviews, and abstracts of major scientific meetings, for example the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). We contacted the authors of eligible studies for missing or unpublished data. The evidence is current to 28 April 2015.

Selection criteria

Two review authors independently screened the relevant citations for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) comparing different GnRH agonist versus GnRH antagonist protocols in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently assessed trial eligibility and risk of bias, and extracted the data. The primary review outcomes were live birth and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Other adverse effects (miscarriage and cycle cancellation) were secondary outcomes. We combined data to calculate pooled odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. We assessed the overall quality of the evidence for each comparison using GRADE methods.

Main results

We included 73 RCTs, with 12,212 participants, comparing GnRH antagonist to long‐course GnRH agonist protocols. The quality of the evidence was moderate: limitations were poor reporting of study methods.

Live birth

There was no evidence of a difference in live birth rate between GnRH antagonist and long course GnRH agonist (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.23; 12 RCTs, n = 2303, I2= 27%, moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the chance of live birth following GnRH agonist is assumed to be 29%, the chance following GnRH antagonist would be between 25% and 33%.

OHSS

GnRH antagonist was associated with lower incidence of any grade of OHSS than GnRH agonist (OR 0.61, 95% C 0.51 to 0.72; 36 RCTs, n = 7944, I2 = 31%, moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the risk of OHSS following GnRH agonist is assumed to be 11%, the risk following GnRH antagonist would be between 6% and 9%.

Other adverse effects

There was no evidence of a difference in miscarriage rate per woman randomised between GnRH antagonist group and GnRH agonist group (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.29; 34 RCTs, n = 7082, I2 = 0%, moderate quality evidence).

With respect to cycle cancellation, GnRH antagonist was associated with a lower incidence of cycle cancellation due to high risk of OHSS (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.69; 19 RCTs, n = 4256, I2 = 0%). However cycle cancellation due to poor ovarian response was higher in women who received GnRH antagonist than those who were treated with GnRH agonist (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.65; 25 RCTs, n = 5230, I2 = 68%; moderate quality evidence).

Authors' conclusions

There is moderate quality evidence that the use of GnRH antagonist compared with long‐course GnRH agonist protocols is associated with a substantial reduction in OHSS without reducing the likelihood of achieving live birth.

Keywords: Adult; Female; Humans; Reproductive Techniques, Assisted; Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone; Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone/agonists; Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone/antagonists & inhibitors; Live Birth; Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome; Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome/prevention & control; Ovulation Induction; Ovulation Induction/methods; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonists versus GnRH agonist in subfertile couples undergoing assisted reproductive technology

Review question

This updated Cochrane review evaluated the efficacy and safety of GnRH antagonists compared to the more widely‐used GnRH agonists (long‐course protocol).

Background:

Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist is commonly used to prevent cycle cancellation secondary to a premature luteinizing hormone (LH) surge, and thereby increase the chance of live birth in women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART), while reducing the risk of complications such as ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists are now being seriously considered as a potential means of achieving better treatment outcomes because the protocol is more flexible and antagonists may reduce OHSS more effectively than agonists. However, there is the need to evaluate the benefits as well as the safety of these GnRH antagonist regimens in comparison with the existing GnRH agonist regimens.

Study characteristics

We found 73 randomised controlled trials comparing GnRH antagonist with GnRH agonist in a total of 12,212 women undergoing ART. The evidence is current to May 2015

Key results

There was no evidence of a difference between the groups in live birth rates (i.e. rates at conclusion of a course of treatment). The evidence suggested that if the chance of live birth following GnRH agonist is assumed to be 29%, the chance following GnRH antagonist would be between 25% and 33%. However, the OHSS rates were much higher after GnRH agonist. The evidence suggested that if the risk of OHSS following GnRH agonist is assumed to be 11%, the risk following GnRH antagonist would be between 6% and 9%.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence was of moderate quality for both live birth and OHSS. The main limitations of the evidence were the possibility of publication bias for live birth (with small studies likely to report favourable outcomes for GnRH antagonist) and poor reporting of study methods for OHSS.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. GnRH antagonist compared to long‐course GnRH agonist for assisted reproductive technology (ART).

| GnRH antagonist compared to long‐course GnRH agonist for assisted reproductive technology (ART) | ||||||

| Population: women undergoing assisted reproductive technology (ART) Settings: clinic for ART Intervention: GnRH antagonist Comparison: long‐course GnRH agonist | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Long course GnRH agonist | GnRH antagonist | |||||

| Live birth rate per woman randomised | 286 per 1000 | 290 per 1000 (254 to 330) | OR 1.02 (0.85 to 1.23) | 2303 (12 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | |

| OHSS per woman randomised (any grade) | 114 per 1000 | 73 per 1000 (62 to 85) | OR 0.61 (0.51 to 0.72) | 7944 (36 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Ongoing pregnancy rate per woman randomised | 293 per 1000 | 276 per 1000 (256 to 295) | OR 0.92 (0.83 to 1.01) | 8311 (37 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Clinical pregnancy rate per woman randomised | 303 per 1000 | 283 per 1000 (267 to 303) | OR 0.91 (0.83 to 1) | 9959 (54 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Miscarriage rate per woman randomised | 48 per 1000 | 49 per 1000 (40 to 61) | OR 1.03 (0.82 to 1.29) | 7082 (34 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate2 | |

| Cycle cancellation due to poor ovarian response | 64 per 1000 | 83 per 1000 (68 to 101) | OR 1.32 (1.06 to 1.65) | 5230 (25 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ moderate3,4 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Asymmetry of the funnel plot with small study effects in favour of GnRH antagonist 2 Most domains of the risk of bias were assessed as either 'unclear' or 'high' 3 Presence of significant heterogeneity among studies with inconsistency in the directions of effect estimates 4 Effect estimate with wide confidence interval

Background

Description of the condition

Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) coupled with in vitro fertilisation (IVF) or intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) was one of the major advances in the treatment of subfertility in the second half of the 20th century. One aspect of COH‐IVF or ICSI that requires attention is the occurrence of a luteinizing hormone (LH) surge which may occur prematurely, before the leading follicle reaches the optimum diameter for triggering ovulation. Such premature LH surges prevent effective induction of multiple follicular maturation patterns for a significant number of women.

Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonists (GnRH agonists) have played an important role in reducing the incidence of premature LH surges by reversibly blocking pituitary gonadotrophin secretion. As a result, the rates of cancellation of assisted conception cycles are decreased and pregnancy rates increased (Albano 1996; Hughes 1992). However, the use of GnRH agonists is not without disadvantages. Even though the standard long‐course GnRH agonist protocol proved to be the most efficacious protocol (Daya 2000) for the use of GnRH agonists, it requires two to three weeks for desensitisation, with relatively high costs due to an increased requirement for gonadotrophin injections, and the need for hormonal and ultrasonographic measurements (Olivennes 1994).

A common complication associated with ovarian stimulation with exogenous gonadotrophins is ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) (Mathur 2007). It usually occurs following a LH surge or after exposure to human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) (Mozes 1965). Most cases of OHSS are mild with few or no clinical consequences. However, severe cases occur occasionally with serious morbidity and mortalities (Delvigne 2002). Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone analogues (GnRH agonists and antagonists) stabilise the luteal phase thereby preventing premature LH surges and reducing the risk of OHSS.

Description of the intervention

In 1999, gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone antagonists (GnRH antagonist) were introduced to the market to prevent LH surge, and it was assumed that GnRH antagonists might be a more patient‐friendly protocol than the mid‐luteal GnRH agonist protocol. GnRH antagonists cause immediate, reversible and dose‐related inhibition of gonadotrophin release by competitive blockade of the GnRH receptors in the pituitary gland, and therefore treatment can be restricted to those days when a premature LH surge is likely to occur (Duijkers 1998; Felberbaum 1995; Huirne 2007).

The first generation of GnRH antagonists were associated with allergic side‐effects due to an induced histamine release, which hampered the clinical development of these compounds. Third generation GnRH antagonists such as ganirelix (NV Organon, Oss, the Netherlands) and cetrorelix (ASTA‐Medica, Frankfurt am Main, Germany) have resolved these issues and are approved for clinical use (Olivennes 1998).

Two approaches have emerged in GnRH antagonist administration; the single‐dose protocol, in which one injection of GnRH antagonist (Cetrotide® 3 mg, Merck SeronoSA., Geneva, Switzerland ) is administered in the late phase of ovarian stimulation and the multiple‐dose regimen, in which 0.25 µg of cetrorelix or ganirelix is administered daily from stimulation day 6 onwards (fixed regimen). A flexible regimen based on the follicular size, has since been introduced to minimise the number and duration of GnRH antagonist injections (Huirne 2007).

In a natural ovulatory cycle, ovulation, the release of the dominant follicle from the ovary, usually occurs about 36 hours after LH surge. In women undergoing controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) during assisted reproductive technology (ART), certain agents are usually administered to mimic the natural LH surge. Ultrasound scan and blood oestrogen levels are used to determine the day on which to administer the triggering agents. Ovulation triggering agents include hCG and GnRH agonist. These agents have different modes of action and their use might, therefore, differentially influence the effectiveness of GnRH antagonists.

How the intervention might work

Applying GnRH antagonists for pituitary desensitisation during COH is expected to result in a dramatic reduction in the duration of GnRH analogue treatment and to reduce the amount of gonadotrophin needed for stimulation as compared with the long agonist protocol. Other potential benefits include a lower risk of developing severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) and avoidance of oestrogen deprivation symptoms (for example hot flushes, sleep disturbances, headaches) frequently observed in the pre‐stimulation phase of a long agonist protocol. Whether the previously mentioned benefits justify a change in routine treatment from the standard long‐course GnRH agonist protocol to the GnRH antagonist regimen depends on whether the clinical outcomes using these protocols are similar.

Why it is important to do this review

The first Cochrane review on this topic was published in 2001 and was updated in 2006 and 2011. As further RCTs have been published, this is a further update of the evidence on the comparative effectiveness of GnRH antagonists versus GnRH agonists in women undergoing COH‐IVF or ICSI, with respect to reducing the risk of OHSS and cycle cancellation while maintaining the live birth rate.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists compared with the standard long protocol of GnRH agonists for controlled ovarian hyperstimulation in assisted conception cycles.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) with a parallel design were eligible for inclusion. Quasi‐randomised trials were not included (e.g. studies with evidence of inadequate sequence generation such as alternate days, patient numbers) as they are associated with a high risk of bias. If cross‐over studies, with cross‐over occurring between cycles, were available, we would have included only the first cycle, before the cross‐over.

Types of participants

Subfertile couples undergoing controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) as part of an IVF or ICSI programme using GnRH antagonists or long‐course GnRH agonist protocols for the prevention of premature LH surges.

Types of interventions

Pituitary suppression with GnRH antagonists (for example cetrorelix, ganirelix) or long‐course GnRH agonists together with ovarian stimulation with recombinant or urinary human follicle stimulating hormone (hFSH) or human menopausal gonadotrophin (hMG), or both, or clomiphene citrate as part of an IVF or ICSI treatment cycles. Further, the use of oral contraceptive pill (OCP) pre‐treatment did not constitute an inclusion or exclusion criterion but rather was a variation in the protocols used.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Live birth rate (LBR) per woman randomised, defined as delivery of a live fetus after 20 completed weeks of gestation.

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) rate per woman randomised, with grading as detected by clinical grading of OHSS, laboratory investigations (e.g. haematocrit, haemoglobin, renal function) or imaging techniques (ovarian and abdominal ultrasound, chest X‐ray), or both: all women, moderate or severe OHSS.

Secondary outcomes

Ongoing pregnancy rate (OPR) per woman randomised, defined as a pregnancy beyond 12 weeks' gestation.

Clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) per woman randomised, defined as the presence of a gestational sac ± fetal heart beat at transvaginal ultrasound.

-

Other adverse effects.

Miscarriage rate per woman randomised: miscarriage is defined as pregnancy loss before 20 weeks' gestation. Miscarriage rate per clinical pregnancy was analysed as a secondary analysis).

Cycle cancellation rate per woman randomised. Two types of cycle cancellation were assessed in separate analyses: cycle cancellation due to high risk of OHSS and cycle cancellation due to poor ovarian response.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all published and unpublished RCTs of GnRH antagonist versus the long‐course GnRH agonist protocol in women undergoing COH‐IVF or ICSI using the following search strategy, without language restriction and in consultation with the Gynaecology and Fertility Group (CGF) (formerly known as Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG)) Information Specialist. We performed the most recent searches on 28 April 2015.

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases, trial registers and websites were searched (from their inception).

Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group (MDSG) Specialised Register (updated search from 2010 to 28 April 2015) (Appendix 1).

Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library; Issue 4 2015) (updated search from 2010 to 28 April 2015) (Appendix 2).

Ovid MEDLINE (updated search from 2010 to 28 April 2015) (Appendix 3). The MEDLINE search was based on the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy (HSSS) for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐maximising version (Lefebvre 2011).

Ovid EMBASE (updated search 2010 up to 28 April 2015) (Appendix 4). The EMBASE search was combined with the trial filter developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (http://sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html).

Ovid PsycINFO (updated search from 2010 to 28 April 2015) (Appendix 5). The PsycINFO search was combined with the trial filter developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (http://sign.ac.uk/methodology/filters.html).

EBSCO CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (Appendix 6).

Trial registers for ongoing and registered trials: ISRCTN (http://www.isrctn.com/), ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/), and the World Health Organization (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) search portal (www.who.int/trialsearch/Default.aspx).

DARE (Database of abstracts of reviews of effectiveness) in The Cochrane Library at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/o/cochrane/cochrane_cldare_articles_fs.html (for reference lists from relevant non‐Cochrane reviews

LILACS database http://lilacs.bvsalud.org/en/ (for trials from the Portuguese and Spanish speaking world)

Citation indexes on the ISI Web of Science (http://ipscience.thomsonreuters.com/product/web‐of‐science/).

LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences) (http://bases.bireme.br/cgi‐bin/wxislind.exe/iah/online/?IsisScript=iah/iah.xis&base=LILACS&lang=i&form=F).

PubMed (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/). The PubMed search was combined with the random control filter for PubMed.

OpenGrey ‐ http://www.opengrey.eu/ for unpublished literature from Europe.

Searching other resources

We also searched the reference lists of all known primary studies, review articles, citation lists of relevant publications, abstracts of major scientific meetings (for example of the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM)). We contacted known experts and personal contacts regarding any unpublished materials.

In addition, we handsearched appropriate journals. The list of journals is in the CGF Module, which can be found in The Cochrane Library under BROWSE ‐ 'By Review Group' ‐ 'Cochrane Gynaecology and Fertility Group' ‐ then 'about this group' at the top of this page. We liaised with the CGF Information Specialist to avoid duplication of handsearching.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

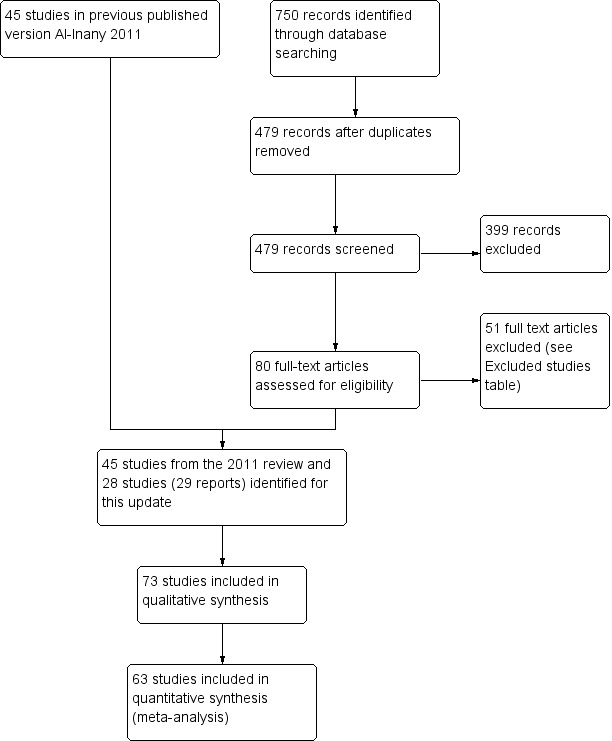

After an initial screen of titles and abstracts retrieved by the search, we retrieved the full texts of all potentially eligible studies. Two review authors (RA and JB) independently examined these full‐text articles for compliance with the inclusion criteria and selected studies eligible for inclusion in the review. We contacted study investigators as required, to clarify study eligibility. We resolved disagreements as to study eligibility by discussion or by involving a third review author (MAY). We documented the selection process with a “PRISMA” flow chart (Figure 1) (Moher 2009)

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

We developed and piloted a standardised data extraction form for consistency and completeness. Three review authors (RA, JB or WSL) independently performed data extraction with discrepancies resolved by discussion. The data extraction forms included study demographics, patient characteristics and study risk of bias. We included this information in the review and presented it in the tables 'Characteristics of included studies' and 'Characteristics of excluded studies' according to the guidance given in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). Where studies had multiple publications the review authors collated multiple reports of the same study, so that each study rather than each report was the unit of interest in the review, and such studies would have a single study ID with multiple references. We contacted trial authors to request additional information or data. We also received a response from the sponsoring pharmaceutical companies.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three authors (RA, JB and WSL) independently assessed the risk of bias of the included trials using The Cochrane 'Risk of bias' (RoB) tool (Higgins 2011b). The domains assessed were: (1) sequence generation (for example; was the method used for allocation sequence adequately described?); (2) allocation concealment (for example, was allocation adequately concealed?); (3) blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors (for example; was knowledge of the allocated intervention adequately prevented during the study?); (4) incomplete outcome data (for example, were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?); (5) selective outcome reporting (for example, were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?); and (6) other sources of bias (for example, was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?). Other potential sources of bias included baseline imbalances, source of funding, early stopping for benefit, and appropriateness of cross‐over design. We resolved disagreements by discussion or by consulting a fourth review author. We described all judgements fully and presented the conclusions in the 'Risk of bias' table (see the Characteristics of included studies table), which was incorporated into the interpretation of review findings by means of sensitivity analyses (see below).

With respect to selective reporting, we sought published protocols and compared the outcomes between the protocol and the final published study, but the searches did not yield published protocols of any of the included studies. We took care to search for within‐trial selective reporting, such as non‐reporting of obvious outcomes, or reporting them in insufficient detail to allow for inclusion. Where identified studies failed to report the primary outcomes of live birth and OHSS but did report interim outcomes such as pregnancy, we undertook informal assessment as to whether the interim values (e.g. pregnancy rates) were similar to those reported in studies that also reported live birth.

Measures of treatment effect

We only reported dichotomous data (e.g. live birth rates) in this review and we used the numbers of events in the control and intervention groups of each study to calculate Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (ORs). We reversed the direction of effect of individual studies, if required, to ensure consistency across trials. We presented 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all outcomes. Where data to calculate ORs were not available, we utilised the most detailed numerical data available that facilitated similar analyses of included studies (e.g. test statistics, P values). We compared the magnitude and direction of effect reported by studies with how they were presented in the review, taking account of legitimate differences (Deeks 2011).

Unit of analysis issues

The primary analysis was per woman randomised. We also included per clinical pregnancy data for miscarriage. we contacted authors of studies that did not allow valid analysis of data (e.g. 'per cycle' data) and requested ‘per woman’ data. If no ‘per woman’ data was provided after contact, we did not include such studies in meta‐analyses.

Dealing with missing data

We analysed the data on an intention‐to‐treat basis as far as possible and made attempts to obtain missing data from the original trialists. Initially, we planned to undertake imputation of individual values for the primary outcomes if we were unable to obtain missing data from the original trialists but no data imputation was undertaken in the end and we analysed only the available data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We assessed statistical heterogeneity by the measure of the I2 statistic (Higgins 2003). We took an I2 statistic measurement greater than 50% to indicate substantial heterogeneity (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, the review authors aimed to minimise their potential impact by ensuring a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by being alert for duplication of data. We used a funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effects (a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies) (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

Where the studies were sufficiently similar, we combined the data using a fixed‐effect analysis (on the assumption that the underlying effect size was the same for all the trials in the analysis) comparing GnRH antagonist versus long course GnRH agonist.

An increase in the odds of a particular outcome that were likely to be beneficial (e.g. live birth) or detrimental (e.g. adverse effects), were displayed graphically in the meta‐analyses to the right of the centre‐line and a decrease in the odds of an outcome to the left of the centre‐line.

All analyses were performed using Review Manager software (RevMan) (RevMan 2014).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Where there were sufficient data we performed subgroup analyses for the following variables, for live birth and pregnancy outcomes.

Triggering agent used for oocyte maturation (hCG, GnRH agonist, mixed (hCG/GnRH agonist) or unknown agent)

Minimal or standard level of stimulation

Where we detected substantial heterogeneity, we explored possible explanations in sensitivity analyses. We took any statistical heterogeneity into account when interpreting the results, especially where there was any variation in the direction of effect.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses for LBR and OPR to determine whether the conclusions were robust to arbitrary decisions made regarding the eligibility and analysis (Moher 1999). These analyses included consideration of whether the review conclusions would have differed if:

a random‐effects model had been adopted;

the summary effect measure was risk ratio rather than odds ratio.

Overall quality of the body of evidence: 'Summary of findings' table

We prepared a 'Summary of findings' table using GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool (GRADEpro GDT 2015). This table evaluated the overall quality of the body of evidence for all review outcomes (live birth, OHSS, ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, miscarriage and cycle cancellation), using GRADE criteria (study limitations (i.e. risk of bias), consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias). Judgements about evidence quality (high, unclear (moderate) or low) were justified, documented, and incorporated into reporting of results for each outcome (Table 1).

Results

Description of studies

See the table 'Characteristics of included studies'.

Results of the search

We retrieved 479 records after removal of duplicates, excluded 399 as ineligible, and assessed 80 full‐text articles. Of these, we excluded 51 and included 28 studies (29 reports). Seventy‐three randomised controlled studies (84 reports), involving 12,212 randomised women, met the inclusion criteria and were fully reviewed (Characteristics of included studies) (See Figure 1 for details of this process).

Included studies

Study characteristics

Twelve studies were multi‐centre (Albano 2000; Baart 2007; Barmat 2005; Euro Middle East 2001; Euro Orgalutran 2000; Fluker 2001; Heijnen 2007; Huirne 2006; Olivennes 2000; Qiao 2012; Rombauts 2006; Sauer 2004), 43 studies were single‐centre trials, while in the remaining studies it was unclear whether they were multi‐centre or single centre.

We considered sample size calculations to be appropriate when the authors of the studies pre‐calculated the number needed in each arm prior to starting the trial. This helps to prevent the occurrence of type II errors. Fifteen studies reported that they had performed a priori sample size calculations (Hwang 2004; Baart 2007; Cota 2012; Engmann 2008a; Heijnen 2007; Huirne 2006; Kim 2011; Kurzawa 2008; Lainas 2010; Sbracia 2009; Sunkara 2014; Tehraninejad 2010; Lin 2006; Depalo 2009; Tazegul 2008); 22 studies reported that they had not performed a sample size calculation; and it was not clear if sample size calculations had been performed in the remaining 36 studies.

Twenty‐three studies said that they had performed intention‐to‐treat analysis (Badrawi 2005; Choi 2012; Cota 2012; Depalo 2009; Engmann 2008a; Euro Middle East 2001; Euro Orgalutran 2000; Fluker 2001; Heijnen 2007; Hosseini 2010; Huirne 2006; Hwang 2004; Khalaf 2010; Kim 2004; Kim 2011; Lin 2006; Loutradis 2004; Marci 2005; Rombauts 2006; Sauer 2004; Serafini 2008; Sunkara 2014; Xavier 2005); 16 studies reported that the original analyses did not use the intention‐to‐treat principle (Albano 2000; Baart 2007; Bahceci 2005; Cheung 2005; El Sahwi 2005; Firouzabadi 2010; Hohmann 2003; Inza 2004; Kurzawa 2008; Kyono 2005; Lee 2005; Olivennes 2000; Sbracia 2009; Tazegul 2008; Tehraninejad 2010; Ye 2009); it was not reported clearly in the rest of the studies.

Participants

Seventy out of 73 studies reported that baseline characteristics were comparable between groups (Characteristics of included studies table) and three did not report information on this. In eighteen of the studies, age was the only reported characteristic compared.

Of the 73 included studies, 49 trials involved an unspecified population of infertile couples, while the remaining trials were performed in specific infertile populations. These populations were or included 'poor responders' (Al‐Karaki 2011; Cheung 2005; Inza 2004; Kim 2011; Kim 2012; Marci 2005; Mohamed 2006; Prapas 2013; Revelli 2014; Sbracia 2009; Sunkara 2014; Tazegul 2008; Toltager 2015) or had polycystic ovary syndrome (Bahceci 2005; Choi 2012; Engmann 2008a; Haydardedeoglu 2012; Hosseini 2010; Hwang 2004; Kim 2004; Kurzawa 2008; Lainas 2007; Lainas 2010; Moshin 2007; Tehraninejad 2010).

The number of randomised women ranged from 20 (Franco 2003) to 1099 (Toltager 2015), including both the GnRH agonist and antagonist groups.

Fifteen studies included 300 or more participants (Awata 2010; Euro Middle East 2001; Euro Orgalutran 2000; Tehraninejad 2011; Gizzo 2014; Haydardedeoglu 2012; Heijnen 2007; Martinez 2008; Prapas 2013; Revelli 2014; Rinaldi 2014; Rombauts 2006; Sbracia 2009; Toltager 2015). There were 30 studies with fewer than 100 participants (Anderson 2014; Barmat 2005; Celik 2011; Check 2004; Cheung 2005; Choi 2012; Cota 2012; Engmann 2008a; Ferrari 2006; Franco 2003; Friedler 2003; Hershko Klement 2015; Hoseini 2014; Hwang 2004; Inza 2004; Khalaf 2010; Kim 2004; Kurzawa 2008; Lainas 2007; Lavorato 2012; Lee 2005; Marci 2005; Mohamed 2006; Moraloglu 2008; Moshin 2007; Sauer 2004; Serafini 2008; Stenbaek 2015Tazegul 2008; Tehraninejad 2010).

Five studies were published before 2002. There were 28 studies published between 2002 and 2006, 18 studies published between 2007 and 2010 and 23 studies between 2011 and 2015

Intervention

All included studies compared GnRH antagonist with long‐course GnRH agonist protocols in women undergoing IVF or ICSI cycles.

We identified three types of antagonist protocols: (1) single, long‐acting administration (Hsieh 2008; Lee 2005; Moshin 2007; Olivennes 2000); (2) fixed, daily administration (Albano 2000; Cheung 2005; Euro Middle East 2001; Euro Orgalutran 2000; Firouzabadi 2010; Fluker 2001; Haydardedeoglu 2012; Hoseini 2014; Hsieh 2008; Huirne 2006; Hwang 2004; Martinez 2008; Moshin 2007; Sauer 2004); and (3) flexible daily administration (Baart 2007; Badrawi 2005; Bahceci 2005; Barmat 2005; Brelik 2004; Check 2004; Choi 2012; Depalo 2009; El Sahwi 2005; Engmann 2008a; Franco 2003; Hershko Klement 2015; Hohmann 2003; Karimzadeh 2010; Kim 2004; Kim 2011; Kurzawa 2008; Lainas 2007; Lainas 2010; Lee 2005; Lin 2006; Loutradis 2004; Marci 2005; Moraloglu 2008; Rombauts 2006; Sbracia 2009; Serafini 2008; Tazegul 2008; Tehraninejad 2010; Xavier 2005; Ye 2009). In the fixed daily protocol, in most of the studies, GnRH antagonist was begun on day six of FSH treatment regardless of follicle size. In the flexible daily protocol, GnRH antagonist was administered according to the lead follicle size and not the cycle date, nor the day of FSH administration. In 25 of the included studies, the type of antagonist protocol used was not reported.

In 44 included trials, the antagonist cetrorelix was administered (Albano 2000; Al‐Karaki 2011; Bahceci 2005; Brelik 2004; Cheung 2005; Cota 2012; Depalo 2009; El Sahwi 2005; Ferrari 2006; Ferrero 2010; Hershko Klement 2015; Hohmann 2003; Hoseini 2014; Hosseini 2010; Hsieh 2008; Huirne 2006; Hwang 2004; Khalaf 2010; Kim 2004; Kim 2011; Kim 2012; Kurzawa 2008; Kyono 2005; Lainas 2010; Lavorato 2012; Lee 2005; Lin 2006; Loutradis 2004; Marci 2005; Mohamed 2006; Moraloglu 2008; Moshin 2007; Olivennes 2000; Rabati 2012; Revelli 2014; Rinaldi 2014; Sauer 2004; Sbracia 2009; Serafini 2008; Sunkara 2014; Tehraninejad 2010; Tehraninejad 2011; Xavier 2005; Ye 2009). In 19 trials, the antagonist ganirelix was administered (Baart 2007; Badrawi 2005; Barmat 2005; Check 2004; Engmann 2008a; Euro Middle East 2001; Euro Orgalutran 2000; Firouzabadi 2010; Fluker 2001; Franco 2003; Gizzo 2014; Haydardedeoglu 2012; Karimzadeh 2010; Lainas 2007; Martinez 2008; Prapas 2013; Qiao 2012; Rombauts 2006; Stenbaek 2015). Three trials used both cetrorelix and ganirelix (Choi 2012; Papanikolaou 2012; Tazegul 2008) and in seven included trials the type of antagonist used was unclear (Anderson 2014; Awata 2010; Celik 2011; Friedler 2003; Heijnen 2007; Inza 2004; Toltager 2015).

Oral contraceptive pill pre‐treatment was used in 18 studies (Barmat 2005; Cheung 2005; Engmann 2008a; Haydardedeoglu 2012; Hershko Klement 2015; Hosseini 2010; Huirne 2006; Kim 2004; Kim 2011; Kim 2012; Kurzawa 2008; Kyono 2005; Lainas 2007; Lainas 2010; Moraloglu 2008; Rombauts 2006; Sauer 2004; Tehraninejad 2010). Further single trials used Diane (Hwang 2004), estradiol in the luteal phase (Franco 2003), and vaginal Nuvaring (Martinez 2008).

Women randomised to treatment with GnRH antagonist started ovarian stimulation on day two to three of the menstrual cycle. The GnRH antagonist was started on stimulation day six, by daily subcutaneous administration up to and including the day of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) administration in the fixed protocol or depending on the dominant follicle size in the flexible protocol.The GnRH long agonist reference treatment was started in the mid‐luteal phase (cycle day 21 to 24) by either daily intranasal or subcutaneous administration.

Ovarian stimulation was started after two weeks if pituitary down‐regulation was established (serum estradiol level < 50 pg/ml). In both treatment groups, ovarian stimulation was started with a fixed daily dose of 150 IU or 225 IU recombinant follicle stimulating hormone (rFSH) or human menopausal gonadotrophin (hMG) for the first five stimulation days. Thereafter, the dose of FSH was adapted depending on the ovarian response, as monitored via ultrasonography (US). Triggering of ovulation was induced with hCG (10,000 IU) if at least three follicles that were more than 17 mm in diameter were observed by US.

Trigger used: the majority of the included studies used hCG trigger or did not state which trigger was used; one of the included studies used a combination of both hCG and GnRH agonist as trigger agents (Engmann 2008a).

Outcomes

Study participant follow up: the optimum follow up would be to report on the number of single, healthy babies going home with their parents (for example single, live, take‐home baby rate). If unavailable, other follow ups were assessed including the live birth rate (LBR) and ongoing pregnancy rate (OPR). None of the included trials described the single, live, take‐home baby rate or the take‐home baby rate. Twelve studies reported on the LBR (Albano 2000; Baart 2007; Barmat 2005; Heijnen 2007; Kim 2011; Kim 2012; Kurzawa 2008; Lin 2006; Marci 2005; Papanikolaou 2012; Rinaldi 2014; Ye 2009). Further, 36 trials reported the OPR and 55 studies reported the clinical pregnancy rate (CPR).

Thirty‐six studies reported OHSS incidence (Albano 2000; Badrawi 2005; Bahceci 2005; Barmat 2005; Engmann 2008a; Euro Middle East 2001; Euro Orgalutran 2000; Firouzabadi 2010; Fluker 2001; Haydardedeoglu 2012; Heijnen 2007; Hohmann 2003; Hosseini 2010; Hsieh 2008; Huirne 2006; Hwang 2004; Karimzadeh 2010; Kim 2012; Kurzawa 2008; Kyono 2005; Lainas 2007; Lainas 2010; Lee 2005; Lin 2006; Moraloglu 2008; Moshin 2007; Olivennes 2000; Papanikolaou 2012; Qiao 2012; Rabati 2012; Rombauts 2006; Serafini 2008; Tehraninejad 2010; Toltager 2015; Xavier 2005; Ye 2009).

Ten studies did not present data in a form that could be included in meta‐analysis (Anderson 2014; Awata 2010; Celik 2011; Choi 2012; Cota 2012; Ferrero 2010; Hoseini 2014; Khalaf 2010; Lavorato 2012; Stenbaek 2015).

Excluded studies

Forty seven studies were excluded for various reasons (see table Characteristics of excluded studies)

Risk of bias in included studies

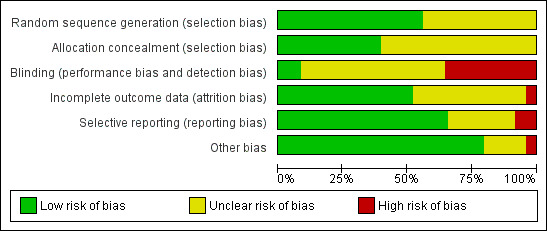

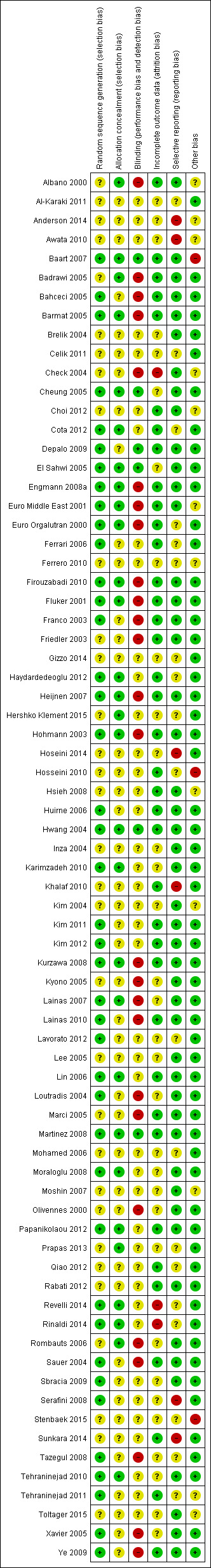

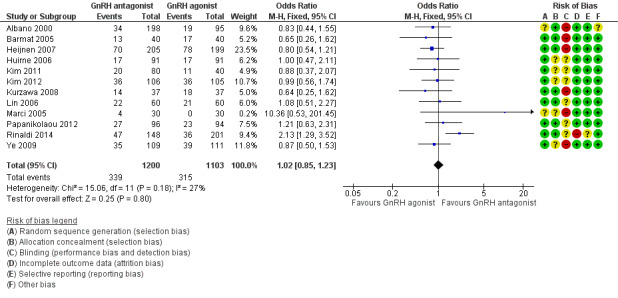

For the risk of bias (ROB) of the included trials, please see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

2.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

Randomisation was done at the time of recruitment of participants.

All trials had a parallel design and proper randomisation was carried out by 39 studies by using: interactive voice response systems (Albano 2000; Euro Middle East 2001; Euro Orgalutran 2000; Rombauts 2006); stratified randomisation (Fluker 2001); computer‐generated random number tables with or without sealed envelopes for allocation concealment (Baart 2007; Badrawi 2005; Barmat 2005; Cota 2012; Depalo 2009; Engmann 2008a; Ferrari 2006; Firouzabadi 2010; Franco 2003; Tehraninejad 2011; Heijnen 2007; Hohmann 2003; Huirne 2006; Hwang 2004; Karimzadeh 2010; Kim 2011; Kim 2012; Kurzawa 2008; Lainas 2007; Lainas 2010; Lavorato 2012; Loutradis 2004; Martinez 2008; Moraloglu 2008; Papanikolaou 2012; Rinaldi 2014; Sauer 2004; Sbracia 2009; Tazegul 2008; Tehraninejad 2010; Ye 2009; Xavier 2005); or random number table (Bahceci 2005; Cheung 2005; Haydardedeoglu 2012 ).

Allocation concealment was properly performed by a nurse (Cota 2012; Lainas 2007; Papanikolaou 2012), by an interactive telephone system (Martinez 2008) or by a sealed opaque envelope (Haydardedeoglu 2012; Hershko Klement 2015; Prapas 2013; Revelli 2014; Rinaldi 2014).

The remaining trials did not report the methods of sequence generation or allocation concealment, or both.

Blinding

We examined blinding with regard to who was blinded in the trials. We looked for all levels of blinding and categorised them as follows: (i) double blind (neither the investigator nor the participants knew the allocation); (ii) single blind (only the investigator knew the allocation); (iii) no blinding (both the investigator and the participants knew the allocated treatment); (iv) unclear.

Since it was impossible to administer the different medications (that is long agonist and antagonist) according to one standard protocol without the use of a double dummy, almost all the studies were open‐label (that is no blinding). One study (Cheung 2005) blinded the clinicians and embryologists from the treatment allocation by using a nurse practitioner to administer the medications. The embryologist scoring the embryos, or the researcher, was blinded to the study groups in five trials (Baart 2007; Depalo 2009; El Sahwi 2005; Hwang 2004; Martinez 2008).

Twenty‐seven trials reported no blinding and we assessed them as being at high risk of bias (Albano 2000; Badrawi 2005; Bahceci 2005; Barmat 2005; Check 2004; Engmann 2008a; Euro Middle East 2001; Euro Orgalutran 2000; Firouzabadi 2010; Fluker 2001; Franco 2003; Friedler 2003; Heijnen 2007; Hohmann 2003; Kurzawa 2008; Kyono 2005; Lainas 2007; Lainas 2010; Loutradis 2004; Marci 2005; Olivennes 2000; Rombauts 2006; Sauer 2004; Tazegul 2008; Tehraninejad 2010; Xavier 2005; Ye 2009). The remaining trials did not clearly report if blinding was performed and we therefore assessed them as being at unclear risk of bias.

However, some of the outcome measures such as live birth were objectively assessed and non‐blinding of study outcome assessors was not likely to have affected their measurement.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged thirty‐seven of the included studies as being at low risk of bias in this domain, because they reported that there were no losses to follow up, proportions of withdrawals and reasons for withdrawals were balanced in both treatment groups, or women were analysed on the basis of intention‐to‐treat, where all women randomised were included in the final analysis whether or not they completed treatment. We judged the remaining studies either as unclear (where studies reported insufficient information with regard to attrition) or high risk of bias (where proportions of and reasons for withdrawals were not balanced between the two treatment groups and not all participants were included in the final analysis).

Selective reporting

Although the protocols of the included studies were not available for assessment, we scrutinised the methods section for pre‐specified outcome measures. Most of the included studies were rated as low risk of bias in this domain as they pre‐specified the outcomes on which data were reported in the methods section. The remaining studies were judged to be either at unclear risk, where there was insufficient information to make conclusive judgements, or low risk, where it was clear that they engaged in selective outcome reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

We found no potential sources of within‐study bias in most of the included studies as the baseline characteristics were similar between the treatment groups and were, therefore, rated to be at low risk of bias. The remaining studies were rated either as unclear risk, where there was insufficient information to arrive at a judgement, or high risk where there was evidence of significant differences in demographic characteristics between the treatment groups.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

The included studies enrolled a total of 12,212 randomised participants, although the sample size varied across the trials. We performed the analyses on the number of women randomised and not on the number of participants treated.

GnRH antagonist versus long course GnRH agonist

Primary outcomes

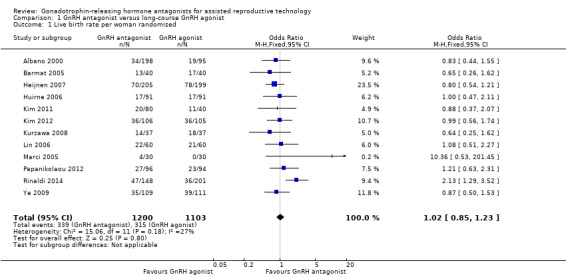

1.1 Live birth rate per woman randomised

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 1 Live birth rate per woman randomised.

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRH antagonist versus long course GnRH agonist, outcome: 1.1 Live birth rate per woman randomised.

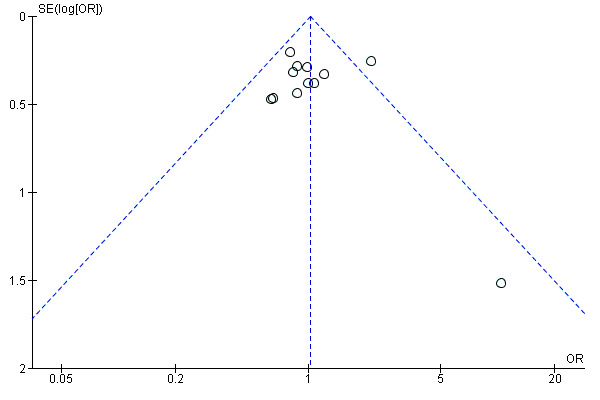

Twelve trials reported live birth rates in 2303 women. There was no evidence of a difference following GnRH antagonist compared with GnRH agonist (OR 1.02, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.23; I2 = 27%, moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the chance of live birth following treatment with GnRH agonist is assumed to be 29%, the chance following treatment with GnRH antagonist would be between 25% and 33%. On sensitivity analysis, there was no change in the above conclusion using a random‐effects model (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.27) or using risk ratio (RR) as a measure of effect estimate (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.15). A funnel plot to explore the possibility of small study effect showed a tendency for estimates of the intervention effect to be more beneficial in smaller studies in the GnRH antagonist group (see Figure 5).

5.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 GnRH antagonist versus long course GnRH agonist, outcome: 1.1 Live birth rate per woman randomised.

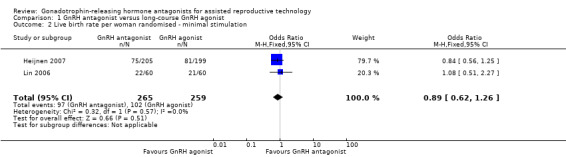

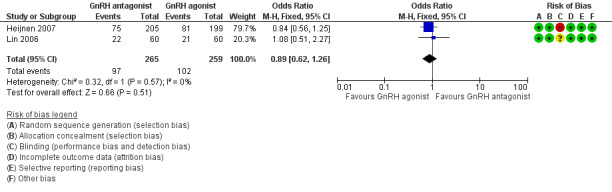

1.2 Live birth rate per woman randomised ‐ Subgroup analysis: Minimal stimulation

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 2 Live birth rate per woman randomised ‐ minimal stimulation.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRH antagonist versus long course GnRH agonist, outcome: 1.2 Live birth rate per woman randomised ‐ minimal stimulation.

Two trials reported live birth rates in 524 women undergoing minimal stimulation IVF. There was no evidence of a difference following GnRH antagonist treatment compared with GnRH agonist treatment (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.26; I2 = 0%).

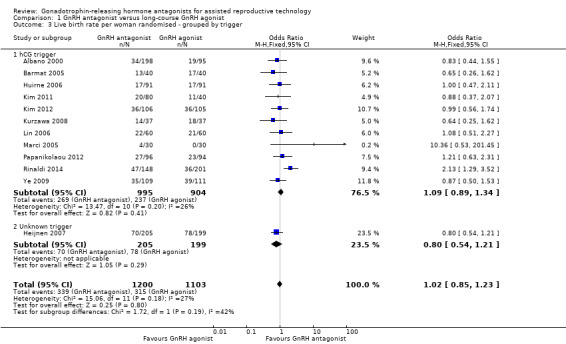

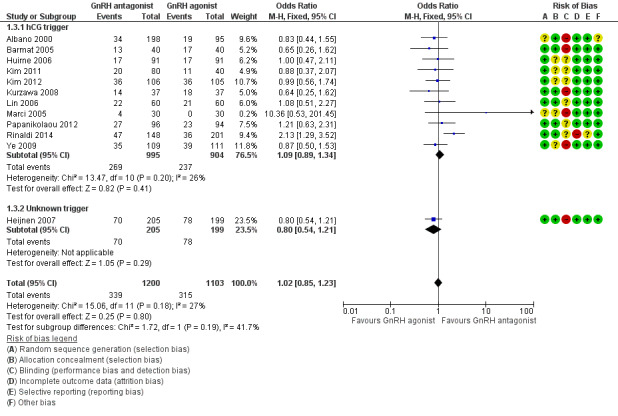

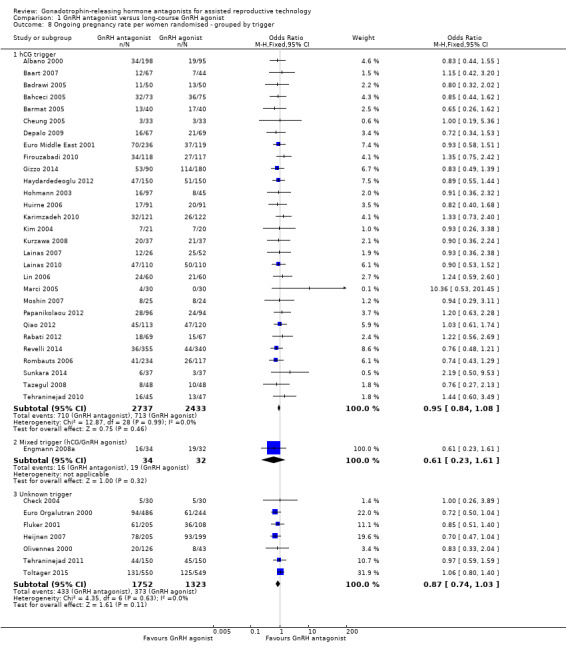

1.3 Live birth rate per woman randomised ‐ Subgroup analysis: Grouped by trigger

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 3 Live birth rate per woman randomised ‐ grouped by trigger.

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, outcome: 1.3 Live birth rate per woman randomised ‐ grouped by trigger.

1.3.1 hCG trigger

In a subgroup analysis, 11 trials reported live birth rates in 1899 women receiving hCG for ovarian maturation. There was no evidence of a difference following GnRH antagonist treatment compared with GnRH agonist treatment (OR 1.09, 95% CI 0.89 to 1.34; I2 = 26%).

1.3.2 Unknown trigger

One trial did not report the triggering agent used for ovarian maturation in 404 women. There was no evidence of a difference in live birth rate between GnRH antagonist and GnRH agonist treatment groups (OR 0.80, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.21).

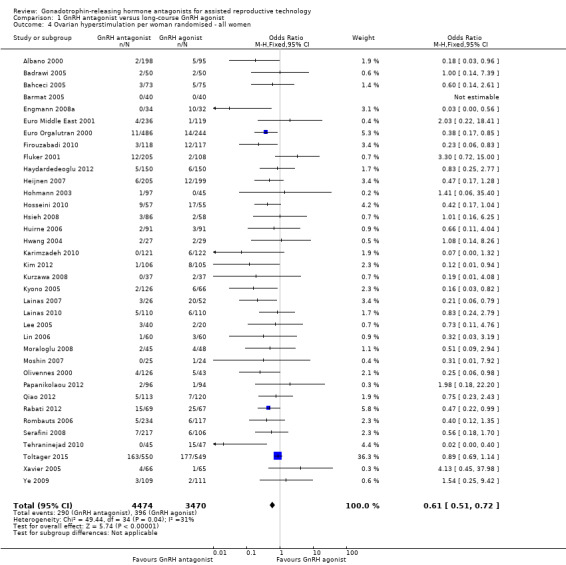

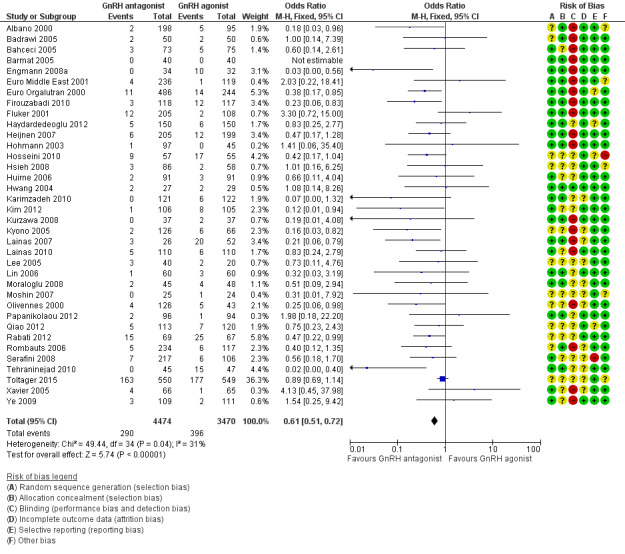

1.4 Ovarian hyperstimulation per woman randomised

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 4 Ovarian hyperstimulation per woman randomised ‐ all women.

8.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRH antagonist versus long course GnRH agonist, outcome: 1.4 Ovarian hyperstimulation per woman randomised ‐ all women.

Thirty‐six trials reported ovarian hyperstimulation rates in 7944 women. There was evidence of a lower OHSS rate in women who received GnRH antagonist compared with those were treated with GnRH agonist: 290/4474 (6%) versus 396/3470 (11%) (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.72; I2 = 31%, moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the risk of OHSS following GnRH agonist is assumed to be 11%, the risk following GnRH antagonist would be between 6% and 9%.

1.5 Ovarian hyperstimulation per woman randomised ‐ Subgroup analysis: Moderate or severe OHSS

1.5. Analysis.

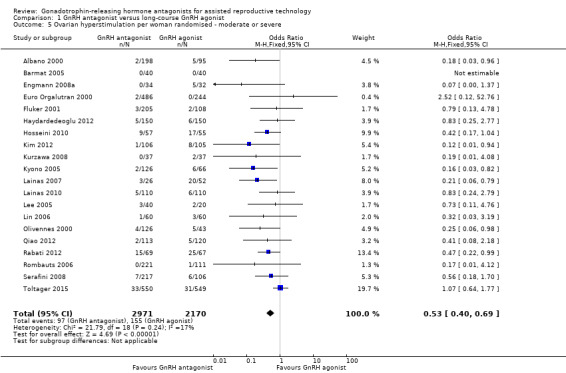

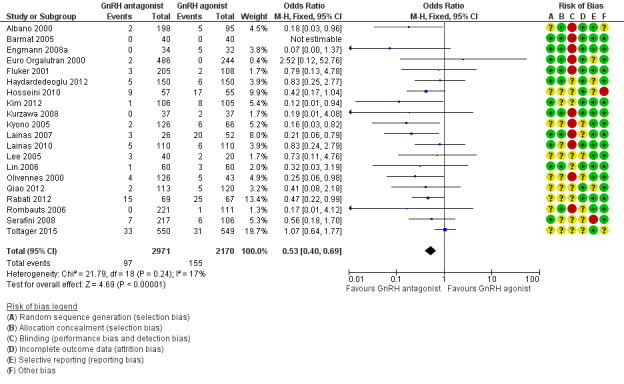

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 5 Ovarian hyperstimulation per woman randomised ‐ moderate or severe.

9.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRH antagonist versus long course GnRH agonist, outcome: 1.5 Ovarian hyperstimulation per woman randomised ‐ moderate or severe.

Twenty trials reported moderate or severe ovarian hyperstimulation rates in 5141 women. There was evidence of a lower rate of moderate or severe OHSS in GnRH antagonist compared with GnRH agonist groups: 97/2971 (3%) versus 155/2170 (7%) (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.69; I2 = 17%).

Secondary outcomes

1.6 Ongoing pregnancy rate per woman randomised

1.6. Analysis.

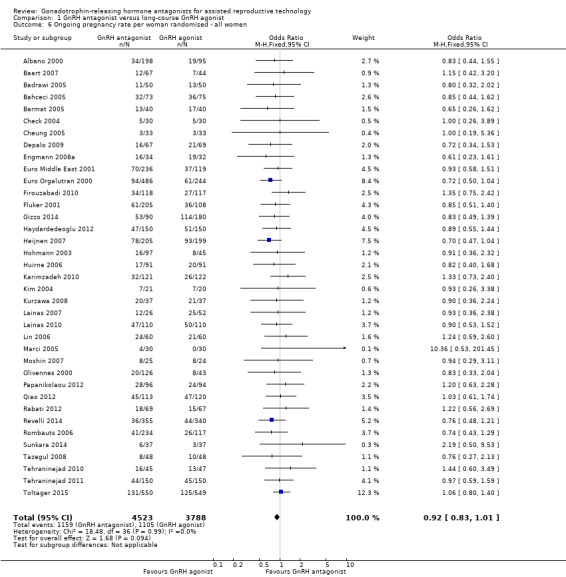

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 6 Ongoing pregnancy rate per woman randomised ‐ all women.

Thirty‐seven trials reported ongoing pregnancy rates in 8311 women. There was no evidence of a difference in ongoing pregnancy rate following treatment with GnRH antagonist compared with GnRH agonist (OR 0.92, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.01; I2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the chance of ongoing pregnancy following GnRH agonist treatment is assumed to be 29%, the chance following GnRH antagonist treatment would be between 26% and 30%. There was no change in the conclusion on sensitivity analysis using either a random‐effects model (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.01) or RR as a measure of treatment effect (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.88 to 1.01).

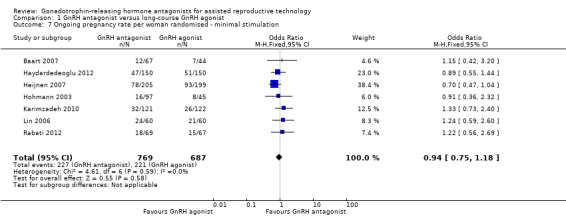

1.7 Ongoing pregnancy rate per woman randomised ‐ Subgroup analysis: Minimal stimulation

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 7 Ongoing pregnancy rate per woman randomised ‐ minimal stimulation.

Seven trials reported ongoing pregnancy rates in 1456 women undergoing minimal stimulation IVF. There was no evidence of a difference following GnRH antagonist treatment compared with GnRH agonist treatment (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.18; I2 = 0%).

1.8 Ongoing pregnancy rate per woman randomised ‐ Subgroup analysis: Grouped by trigger

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 8 Ongoing pregnancy rate per women randomised ‐ grouped by trigger.

1.8.1 hCG trigger

In a subgroup analysis, 29 studies reported ongoing pregnancy rate in 5170 women in whom hCG was used to trigger oocyte maturation. There was no evidence of a difference in ongoing pregnancy rate between the two treatment groups (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.08; I2 = 0%).

1.8.2 Mixed trigger

One study used hCG and GnRH agonist in GnRH antagonist and GnRH agonist groups respectively to trigger oocyte maturation in 66 women. There was no evidence of a difference in ongoing pregnancy rate between GnRH antagonist and GnRH agonist groups (OR 0.61, 95% CI 0.23 to 1.61).

1.8.3 Unknown trigger

In a subgroup analysis, seven trials reported ongoing pregnancy rates in 3075 women in whom the agent used in triggering oocyte maturation was unknown. There was no evidence of a difference following treatment with GnRH antagonist compared with GnRH agonist (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.03; I2 = 0%).

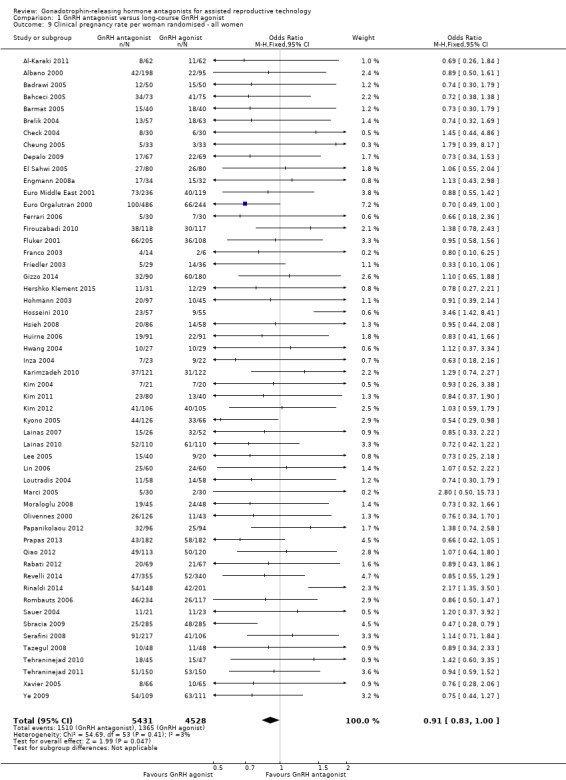

1.9 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman randomised

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 9 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman randomised ‐ all women.

Fifty‐four trials reported clinical pregnancy rates in 9959 women . There was evidence of a difference following GnRH antagonist treatment compared with GnRH agonist treatment with a smaller proportion of women reporting clinical pregnancies in the GnRH antagonist group: 1510/5431 (28%) versus 1365/4528 (30%) (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.00; I2 = 1%, moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the chance of clinical pregnancy following GnRH agonist treatment is assumed to be 30%, the chance following GnRH antagonist treatment would be between 27% and 30%.

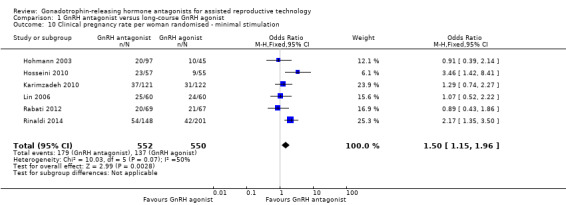

1.10 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman randomised ‐ Subgroup analysis: Minimal stimulation

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 10 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman randomised ‐ minimal stimulation.

Six studies reported clinical pregnancy rate in 1102 women receiving minimal ovarian stimulation. There was evidence of a higher clinical pregnancy rate in the GnRH antagonist group compared to the GnRH agonist group: 179/552 (32%) versus 137/550 (25%) (OR 1.50, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.96; I2 = 50%).

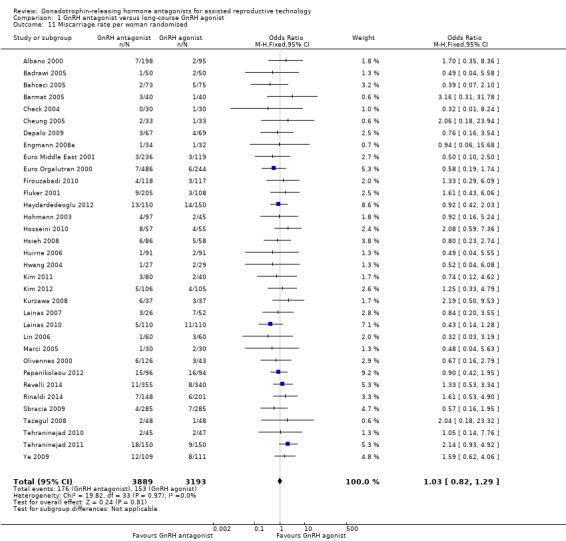

1.11 Miscarriage rate per woman randomised

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 11 Miscarriage rate per woman randomised.

Thirty‐four trials reported miscarriage rates in 7082 women. There was no evidence of a difference following GnRH antagonist treatment compared with GnRH agonist treatment (OR 1.03, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.29; I2 = 0%; moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the risk of miscarriage following GnRH agonist treatment is assumed to be 5%, the risk following GnRH antagonist treatment would be between 4% and 6%.

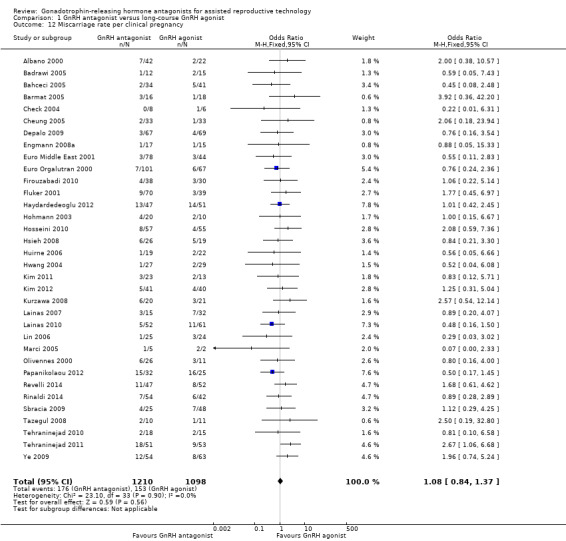

1.12 Miscarriage rate per clinical pregnancy rate

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 12 Miscarriage rate per clinical pregnancy.

Thirty‐four trials reported miscarriage rates per clinical pregnancy rates in 2308 women. There was no evidence of a difference following treatment with GnRH antagonist compared with GnRH agonist (OR 1.08, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.37; I2 = 0%)..

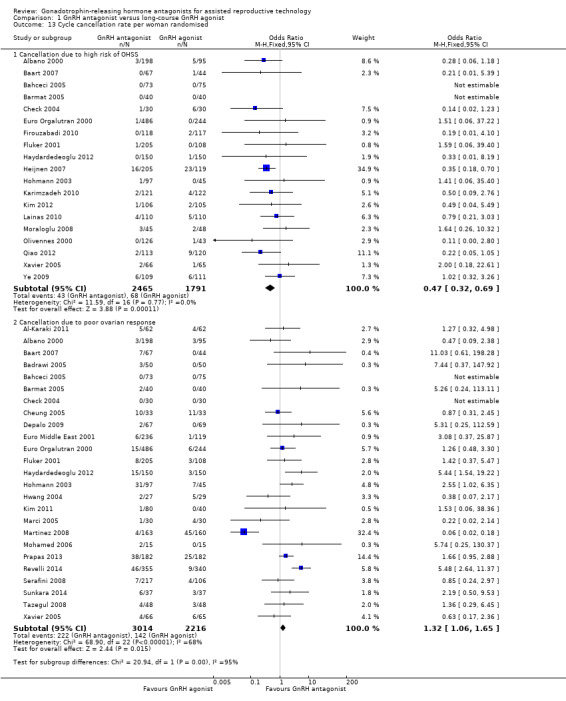

1.13 Cycle cancellation rate per woman randomised

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist, Outcome 13 Cycle cancellation rate per woman randomised.

1.13.1 Cancelled due to high risk of OHSS

Nineteen trials reported rates of cycle cancellation due to high risk of OHSS in 4256 women. There was evidence of a difference in cancellation rates with fewer cycles cancelled in the GnRH antagonist groups compared with the GnRH agonist groups (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.69; I2 = 0%).

1.13.2 Cancellation due to poor ovarian response

Twenty‐five trials reported rates of cancellation due to poor ovarian response in 5230 women. There was evidence of a difference in cycle cancellation rates with more cycles cancelled in GnRH antagonist groups compared with GnRH agonist groups (OR 1.32, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.65; I2 = 68%, moderate quality evidence). The evidence suggested that if the risk of cycle cancellation following GnRH agonist treatment is assumed to be 6%, the risk following GnRH antagonist treatment would be between 7% and 10%. There was evidence of statistical heterogeneity among the trials that contributed data to the pooled effect estimate, with variations in the direction of effect estimates of individual trials. On sensitivity analysis using a random‐effects model, there was no evidence of a difference in cancellation rate between the two treatment groups (OR 1.38, 95% CI 0.82 to 2.31). Thus there is some degree of uncertainty with respect to this outcome, as it is sensitive to the choice of statistical model.

Discussion

Summary of main results

The previous version of this systematic review included 45 studies, while this updated version includes 73 RCTs and 12,212 randomised women. To our knowledge this systematic review and meta‐analysis represents the most recent and largest amount of evidence comparing the use of GnRH antagonist with long‐course GnRH agonist protocols in IVF or ICSI treatment cycles.

In this updated version of the review we focused on the effectiveness and safety of GnRH antagonist compared to GnRH agonist cycles in ART. Regarding effectiveness, there was no evidence of differences in live birth rate and ongoing pregnancy rate between GnRH agonist and GnRH antagonist LH peak suppression protocols.

With regard to safety, GnRH antagonists substantially reduced the incidence of OHSS. For the overall population from assembled studies, the evidence suggested that, if the risk of OHSS following GnRH agonist is assumed to be 11%, the risk following GnRH antagonist would be between 6% and 9%. In addition, there was evidence of a lower rate of moderate or severe OHSS in women who received the GnRH antagonist protocol compared with those who were treated with the GnRH agonist long protocol. However there was no evidence of a difference in miscarriage rates per woman randomised between the two treatment protocols. There was no clear picture with respect to cycle cancellation between the two treatment groups. While fewer cycles were cancelled in the GnRH antagonist group due to high risk of OHSS, there is some degree of uncertainty with cancellation due to poor ovarian response, as this outcome was sensitive to the choice of statistical model. In summary, there is moderate quality evidence that the use of GnRH antagonist compared with long‐course GnRH agonist protocols is associated with a substantial reduction in OHSS without reducing the likelihood of achieving live birth or ongoing pregnancy.

Previous versions of this systematic review showed substantially lower clinical and ongoing pregnancy rates for the GnRH antagonist protocol. Two earlier meta‐analyses of studies, comparing fixed and flexible GnRH antagonist protocols directly, demonstrated a trend towards higher pregnancy rates when using the fixed protocol, possibly explained by better LH control (Al‐Inany 2005; Kolibianakis 2006). The improved performance of antagonist cycles in the present update cannot be explained by the relative use of fixed protocols however, as relatively few new fixed protocols were included.

Several studies have suggested that LH instability decreases the probability of pregnancy in antagonist cycles (Bosch 2003; Kolibianakis 2003; Seow 2010; Shoham 2002). LH instability is defined as any fluctuation in LH level, either a LH surge or rise in LH concentration, in the course of ovarian hyperstimulation. A decrease in the relative incidence of LH instability in the current review can possibly have improved pregnancy outcomes in antagonist cycles, although the mechanism for such change is still unclear. Further studies are needed to investigate the possible role of LH‐instability in the improvement of pregnancy outcomes of GnRH antagonist cycles.

Increased favourable pregnancy outcomes with GnRH antagonist treatment may also be the result of an improved learning curve with the relatively new GnRH antagonist over the last 15 years. Extensive experience with GnRH antagonist protocols in large studies, leading to more favourable study outcomes, may have positively influenced pregnancy outcomes of GnRH antagonist cycles. Finally, changes in the use of OCP pretreatment (Griesinger 2008), scheduling of hCG for final oocyte maturation (Kolibianakis 2004; Tremellen 2010; Orvieto 2008) or patient selection (Sbracia 2009) may all have contributed to the optimisation of the use of antagonist cycles in ART. However, the improvement in pregnancy outcomes could also be due to the effects of potential bias in the included studies. For example, the forest plot (Figure 5) suggests a tendency for publication of studies with more favourable outcomes with the possibility of existence of unpublished studies with less favourable outcomes.

Previous work on the role of OCP pretreatment in direct comparison studies has indicated that OCP pretreatment leads to a longer duration of stimulation, higher oocyte yield, but reduced ongoing pregnancy rate (Smulders 2010). Also a trend towards lower pregnancy rates when using OCP pretreatment has been observed in a separate meta‐analysis (Griesinger 2008). As such, it has been recommended that OCP pretreatment does not seem to be the regimen of choice for GnRH antagonist cycles. In the previous versions of this review, however, a subgroup analysis of studies that used OCP pretreatment revealed no substantial difference between the agonist and antagonist groups for ongoing or clinical pregnancy rates. The percentage of women receiving OCP pretreatment in the 2011 update was comparable with the preceding version in 2006.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Overall, the data demonstrate that GnRH antagonist is useful in women undergoing IVF or ICSI because it substantially reduces the occurrence of OHSS without reducing the chances of achieving live a live birth.

A long‐course GnRH agonist protocol with maximum ovarian stimulation has been the standard protocol for many decades. However, it is relatively complex and expensive, requires long treatment cycles and intensive monitoring, and leads to an abnormal hormonal environment in women. There is now an eager desire to shift to more patient‐friendly, mild ovarian‐stimulation regimens in which GnRH antagonist may be a suitable solution because there is evidence to suggest that its use is associated with comparable pregnancy outcomes.

A good number of the included studies did not report live birth and OHSS: 12 of the included studies reported data on live birth while only 36 reported data on OHSS. One study used single embryo transfer in the antagonist arm and double embryo transfer in the agonist arm. Some of the outcomes of interest were reported by some of the included studies in such a way that they could not be included in meta‐analyses. For example, some of the denominators were reported as 'per oocyte' or 'per embryo' transferred, where the numbers of oocytes or embryos transferred were not equal to the number of women randomised. In some of the included studies, some outcomes were not properly defined making it difficult to categorise such outcomes, for example, 'pregnancy rate' which could either be 'ongoing' or 'clinical' pregnancy. We included a small number of studies because they met the inclusion criteria, although they did not report data on any of the outcomes of interest. With respect to the triggering agent used for oocyte maturation, the majority of the studies either used hCG or did not report the triggering agent used. Thus no comparison could be made between the triggering agents such as hCG versus GnRH agonist.

Quality of the evidence

The evidence was of moderate quality using GRADE ratings for live birth, OHSS, ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, miscarriage and cycle cancellation due to poor ovarian response. The main limitations in the evidence were poor reporting of study methods. For example, a majority of the included studies either did not report the processes involved in random sequence generation and allocation concealment or reported vague and insufficient information on the processes, thereby making it difficult to make conclusive judgements on these domains of risk of bias. Poor reporting also affected the assessment of other domains of risk of bias with most of them being rated as 'unclear'. For live birth, there was evidence suggestive of the possibility of reporting (publication) bias with small studies more likely to report favourable outcomes for GnRH antagonist.

Potential biases in the review process

Although comprehensive searches were undertaken to ensure that all eligible studies were identified, it is not impossible that some potentially eligible studies could have been left out.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

A systematic review and meta‐analysis, Youssef 2012, compared the effectiveness and safety of various protocols including GnRH antagonist versus long‐course GnRH agonist protocol. There was no evidence of a difference between women who received GnRH antagonist and those who were treated with long‐course GnRH agonist protocol in three RCTs, either in clinical pregnancy rate (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.05, five RCTs) or cycle cancellation rate (OR 1.25, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.05).

There is a systematic review and meta‐analysis that included 22 RCTs (n = 3176) to compare GnRH antagonists and GnRH agonists (Kolibianakis 2006). The reported outcome measure, clinical pregnancy or ongoing pregnancy, was converted to live births in 12 studies using the published data. No evidence of a difference was detected in the probability of a live birth between the two GnRH analogues (OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.02). The result remained stable in a subgroup analysis that ordered the studies by type of population studied, gonadotrophin type used for stimulation, type of agonist protocol used, type of agonist used, type of antagonist protocol used, type of antagonist used, presence of allocation concealment, presence of co‐intervention and the way the information on live births was retrieved.

A systematic review and meta‐analysis, Franco 2006, evaluated the efficacy of gonadotrophin antagonist versus GnRH agonist in poor ovarian responders in IVF and ICSI cycles. The review included six RCTs that compared GnRH antagonist to long or short GnRH agonist. There was no difference between GnRH antagonist and GnRH agonist (long and flare‐up protocols) with respect to cycle cancellation rate, number of mature oocytes and clinical pregnancy rate per cycle initiated, per oocyte retrieval and per embryo transfer. When the meta‐analysis was applied to the two trials that had used GnRH antagonist versus long protocols of GnRH agonist, a significantly higher number of retrieved oocytes was observed in the GnRH antagonist protocols (MD 1.12, 95% CI 0.18 to 2.05; P = 0.018).

In another systematic review and meta‐analysis of four RCTs (n = 874) ongoing pregnancy rate was the main outcome (Griesinger 2008). There was no evidence of a statistically significant difference between women with and without OCP pre‐treatment (OR 0.74, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.03). Duration of gonadotrophin stimulation (1.41 days, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.68) and gonadotrophin consumption (542 IU, 95% CI 127 to 956) were significantly increased after OCP pre‐treatment. No significant differences were observed regarding the number of retrieved oocytes.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The GnRH antagonist protocol is a short and simple protocol with evidence suggesting a comparable live birth rate and a substantial reduction in the incidence of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome when compared to GnRH agonist long protocol in women undergoing ART.

Implications for research.

In view of the shortcomings noted in the included studies, especially with regard to the methods of reporting of trial procedures, more properly designed studies in accordance with the CONSORT statement are need to further evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the GnRH antagonist protocol (Schulz 2010). For example, it would be desirable to have trials with low risk of bias with primary outcomes of live birth and OHSS. In addition, further studies are needed to assess this treatment regimen in poor and high responders. We attempted to subgroup treatment regimens by the ovulation triggering agent but no data were available for a proper analysis, as the majority of the included studies either used hCG or did not specify their triggering agents. This is a potential area to be explored by future research. It is also important to understand why pregnancy outcomes have become progressively more favourable with the use of GnRH antagonists. One possible explanation for this could be a decrease in LH instability. This area should be further investigated. Although not a focus of the current update, the potential effects of OCP pretreatment should be further investigated.

Patient satisfaction surveys should also be undertaken to evaluate their impression about GnRH antagonist treatment regimens.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 31 August 2016 | Review declared as stable | Further evidence is unlikely to change the conclusions of this review. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 1999 Review first published: Issue 4, 2001

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 9 May 2016 | Amended | Correction to reinstate data removed in error (Marci 2005) |

| 3 February 2016 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The addition of new studies did not change the conclusions of this review. |

| 3 February 2016 | New search has been performed | This review has been updated, and 28 new studies added. |

| 7 July 2011 | Amended | Minor amendments to new citation version published May 2011 |

| 13 April 2011 | New search has been performed |

|

| 13 April 2011 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | The conclusion has changed |

| 13 June 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 19 May 2006 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all members of the Gynaecology and Fertility Group for their valuable support in this review. The authors also wish to acknowledge the following people for their contributions to the previous versions of the review: Monique D. Sterrenburg, Janine G Smit, Ahmed M Abou‐Setta, and Mohamed Aboulghar.

Appendices

Appendix 1. MDSG specialised register

MDSG Search string for HA412 Procite platform

Keywords CONTAINS "GnRH antagonist" or "GnRh antagonists" or "Antagon" or "ceterolix" or "cetrolix" or "cetrorelix" or "cetrotide" or "Ganirelix" or "Luteinising hormone releasing hormone" or "Lutenising hormone releasing hormone" or "LHRH antagonists" or Title CONTAINS "GnRH antagonist" or "GnRh antagonists" or "Antagon" or "ceterolix" or "cetrolix" or "cetrorelix" or "cetrotide" or "Ganirelix" or "Luteinising hormone releasing hormone" or "Lutenising hormone releasing hormone" or "LHRH antagonists"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "GnRH a", "GnRH agonist" or "GnRH agonist short protocol" or "GnRH agonist vs antagonist" or "GnRH agonists" or "GnRHa" or "GnRHa‐gonadotropin" or"Gonadotrophin releasing agonist" or "buserelin" or "Buserelin Acetate" or "buserelin naferelin" or "busereline" or "Goserelin" or "goserelin acetate" or "Gosereline " or "Leuprolide" or "leuprolide acetate" or "leuprolide depot" or "leuprorelin" or "leuprolin" or "leuprorelin acetate" or "Nafarelin" or "Nafarelin Study Group" or "triptoielin" or "triptoreline" or "triptoreline pamoat" or "triptorelyn" or "triptrolein" or "Lupron" or "Zoladex" or "deslorelin" or "decapeptyl" or "decapeptyl‐daily" or "decapeptyl‐depot" or Title CONTAINS "GnRH a", "GnRH agonist" or "GnRH agonist short protocol" or "GnRH agonist vs antagonist" or "GnRH agonists" or "GnRHa" or "GnRHa‐gonadotropin" or"Gonadotrophin releasing agonist" or "buserelin" or "Buserelin Acetate" or "buserelin naferelin" or "busereline" or "Goserelin" or "goserelin acetate" or "Gosereline " or "Leuprolide" or "leuprolide acetate" or "leuprolide depot" or "leuprorelin" or "leuprolin" or "leuprorelin acetate" or "Nafarelin" or "Nafarelin Study Group" or "triptoielin" or "triptoreline" or "triptoreline pamoat" or "triptorelyn" or "triptrolein" or "Lupron" or "Zoladex" or "deslorelin" or "decapeptyl" or "decapeptyl‐daily" or "decapeptyl‐depot"

Appendix 2. Ovid Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

From inception to April 2015 1 Hormone Antagonists/ (305) 2 gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist$.tw. (87) 3 gonadotrophin releasing hormone antagonist$.tw. (29) 4 GnRH antagonist$.tw. (555) 5 Gn‐RH antagonist$.tw. (0) 6 (Cetrorelix or Cetrotide$).tw. (139) 7 Ganirelix.tw. (81) 8 (Abarelix or Plenaxis).tw. (11) 9 Antagon.tw. (10) 10 Degarelix.tw. (29) 11 or/1‐10 (855) 12 exp gonadotropin‐releasing hormone/ or exp buserelin/ or exp goserelin/ or exp leuprolide/ or exp nafarelin/ or exp triptorelin/ (1885) 13 gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist$.tw. (359) 14 gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonist$.tw. (146) 15 GnRH agonist$.tw. (796) 16 Gn‐RH agonist$.tw. (4) 17 (buserelin or goserelin).tw. (668) 18 (leuprolide or nafarelin).tw. (536) 19 triptorelin.tw. (196) 20 (Lupron or Eligard).tw. (37) 21 (Suprefact or Suprecor).tw. (9) 22 Synarel.tw. (3) 23 Supprelin.tw. (0) 24 Zoladex.tw. (227) 25 deslorelin.tw. (9) 26 Suprelorin.tw. (0) 27 Ovuplant.tw. (0) 28 (decapeptyl or trelstar).tw. (58) 29 (profact or receptal).tw. (4) 30 suprecur.tw. (0) 31 tiloryth.tw. (0) 32 (GNRH‐a or GNRH a).tw. (1393) 33 or/12‐32 (3280) 34 11 and 33 (520)

Appendix 3. Ovid MEDLINE(R)

From inception to April 2015 1 Hormone Antagonists/ (4693) 2 gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist$.tw. (480) 3 gonadotrophin releasing hormone antagonist$.tw. (125) 4 GnRH antagonist$.tw. (2080) 5 Gn‐RH antagonist$.tw. (7) 6 (Cetrorelix or Cetrotide$).tw. (448) 7 Ganirelix.tw. (136) 8 (Abarelix or Plenaxis).tw. (53) 9 Antagon.tw. (17) 10 Degarelix.tw. (114) 11 or/1‐10 (6692) 12 exp gonadotropin‐releasing hormone/ or exp buserelin/ or exp goserelin/ or exp leuprolide/ or exp nafarelin/ or exp triptorelin/ (29123) 13 gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist$.tw. (1745) 14 gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonist$.tw. (467) 15 GnRH agonist$.tw. (3564) 16 Gn‐RH agonist$.tw. (52) 17 (buserelin or goserelin).tw. (2026) 18 (leuprolide or nafarelin).tw. (1812) 19 triptorelin.tw. (563) 20 (Lupron or Eligard).tw. (163) 21 (Suprefact or Suprecor).tw. (24) 22 Synarel.tw. (12) 23 Supprelin.tw. (2) 24 Zoladex.tw. (373) 25 deslorelin.tw. (204) 26 Suprelorin.tw. (16) 27 Ovuplant.tw. (11) 28 (decapeptyl or trelstar).tw. (208) 29 (profact or receptal).tw. (28) 30 suprecur.tw. (5) 31 tiloryth.tw. (0) 32 (GNRH‐a or GNRH a).tw. (937) 33 or/12‐32 (31184) 34 11 and 33 (2358) 35 randomized controlled trial.pt. (392594) 36 controlled clinical trial.pt. (89288) 37 randomized.ab. (317546) 38 placebo.tw. (165796) 39 clinical trials as topic.sh. (172358) 40 randomly.ab. (229154) 41 trial.ti. (136960) 42 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (63745) 43 or/35‐42 (975714) 44 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. (3933883) 45 43 not 44 (898609) 46 34 and 45 (500)

Appendix 4. Ovid EMBASE

From inception to April 2015 1 Hormone Antagonist/ (1475) 2 Gonadorelin Antagonist/ (4507) 3 gonadotropin releasing hormone antagonist$.tw. (533) 4 Gnrh Antagonist$.tw. (2984) 5 Luteinizing Hormone Releasing Hormone Antagonist$.tw. (88) 6 Lhrh Antagonist$.tw. (354) 7 Cetrorelix.tw. (670) 8 cetrorelix/ or ganirelix/ (2218) 9 ganirelix.tw. (306) 10 Cetrotide.tw. (636) 11 Antagon.tw. (118) 12 Orgalutr?n.tw. (397) 13 Degarelix.tw. (226) 14 or/1‐13 (7917) 15 Gonadorelin Agonist/ (11188) 16 GnRH agonist$.tw. (4929) 17 gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist$.tw. (2015) 18 Lhrh Agonist$.tw. (1323) 19 Luteinizing Hormone Releasing Hormone Agonist$.tw. (562) 20 TRIPTORELIN/ (4176) 21 Triptorelin.tw. (824) 22 (Arvekap or Decapeptyl or Detryptorelin or Trelstar or Tryptorelin).tw. (1772) 23 BUSERELIN/ (4084) 24 Buserelin.tw. (1473) 25 (Bigonist or Busereline or Receptal or Superfact or Suprefact).tw. (1135) 26 (GNRH‐a or GNRH a).tw. (1127) 27 or/15‐26 (19742) 28 14 and 27 (2960) 29 Clinical Trial/ (843206) 30 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (368416) 31 exp randomization/ (66003) 32 Single Blind Procedure/ (20039) 33 Double Blind Procedure/ (119722) 34 Crossover Procedure/ (42461) 35 Placebo/ (254717) 36 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (114462) 37 Rct.tw. (16650) 38 random allocation.tw. (1399) 39 randomly allocated.tw. (22089) 40 allocated randomly.tw. (2010) 41 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (721) 42 Single blind$.tw. (15600) 43 Double blind$.tw. (149516) 44 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (439) 45 placebo$.tw. (212288) 46 prospective study/ (286502) 47 or/29‐46 (1449548) 48 case study/ (31233) 49 case report.tw. (279055) 50 abstract report/ or letter/ (920165) 51 or/48‐50 (1224269) 52 47 not 51 (1410589) 53 28 and 52 (929)

Appendix 5. Ovid PsycINFO