Abstract

Background

Although helicopters are presently an integral part of trauma systems in most developed nations, previous reviews and studies to date have raised questions about which groups of traumatically injured people derive the greatest benefit.

Objectives

To determine if helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) transport, compared with ground emergency medical services (GEMS) transport, is associated with improved morbidity and mortality for adults with major trauma.

Search methods

We ran the most recent search on 29 April 2015. We searched the Cochrane Injuries Group's Specialised Register, The Cochrane Library (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; CENTRAL), MEDLINE (OvidSP), EMBASE Classic + EMBASE (OvidSP), CINAHL Plus (EBSCOhost), four other sources, and clinical trials registers. We screened reference lists.

Selection criteria

Eligible trials included randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized intervention studies. We also evaluated nonrandomized studies (NRS), including controlled trials and cohort studies. Each study was required to have a GEMS comparison group. An Injury Severity Score (ISS) of at least 15 or an equivalent marker for injury severity was required. We included adults age 16 years or older.

Data collection and analysis

Three review authors independently extracted data and assessed the risk of bias of included studies. We applied the Downs and Black quality assessment tool for NRS. We analyzed the results in a narrative review, and with studies grouped by methodology and injury type. We constructed 'Summary of findings' tables in accordance with the GRADE Working Group criteria.

Main results

This review includes 38 studies, of which 34 studies examined survival following transportation by HEMS compared with GEMS for adults with major trauma. Four studies were of inter‐facility transfer to a higher level trauma center by HEMS compared with GEMS. All studies were NRS; we found no RCTs. The primary outcome was survival at hospital discharge. We calculated unadjusted mortality using data from 282,258 people from 28 of the 38 studies included in the primary analysis. Overall, there was considerable heterogeneity and we could not determine an accurate estimate of overall effect.

Based on the unadjusted mortality data from six trials that focused on traumatic brain injury, there was no decreased risk of death with HEMS. Twenty‐one studies used multivariate regression to adjust for confounding. Results varied, some studies found a benefit of HEMS while others did not. Trauma‐Related Injury Severity Score (TRISS)‐based analysis methods were used in 14 studies; studies showed survival benefits in both the HEMS and GEMS groups as compared with MTOS. We found no studies evaluating the secondary outcome, morbidity, as assessed by quality‐adjusted life years (QALYs) and disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs). Four studies suggested a small to moderate benefit when HEMS was used to transfer people to higher level trauma centers. Road traffic and helicopter crashes are adverse effects which can occur with either method of transport. Data regarding safety were not available in any of the included studies. Overall, the quality of the included studies was very low as assessed by the GRADE Working Group criteria.

Authors' conclusions

Due to the methodological weakness of the available literature, and the considerable heterogeneity of effects and study methodologies, we could not determine an accurate composite estimate of the benefit of HEMS. Although some of the 19 multivariate regression studies indicated improved survival associated with HEMS, others did not. This was also the case for the TRISS‐based studies. All were subject to a low quality of evidence as assessed by the GRADE Working Group criteria due to their nonrandomized design. The question of which elements of HEMS may be beneficial has not been fully answered. The results from this review provide motivation for future work in this area. This includes an ongoing need for diligent reporting of research methods, which is imperative for transparency and to maximize the potential utility of results. Large, multicenter studies are warranted as these will help produce more robust estimates of treatment effects. Future work in this area should also examine the costs and safety of HEMS, since multiple contextual determinants must be considered when evaluating the effects of HEMS for adults with major trauma.

Plain language summary

Helicopter emergency medical services for adults with major trauma

Background

Trauma is a leading cause of death and disability worldwide and, since the 1970s, helicopters have been used to transport people with injuries to hospitals that specialize in trauma care. Helicopters offer several potential advantages, including faster transport, and care from medical staff who are specifically trained in the management of major injuries.

Study characteristics

We searched the medical literature for clinical studies comparing the transport of adults who had major injuries by helicopter ambulance (HEMS) or ground ambulance (GEMS). The evidence is current to April 2015.

Key results

We found 38 studies which included people from 12 countries around the world. Researchers wanted to find out if using a helicopter ambulance was any better than a ground ambulance for improving an injured person's chance of survival, or reducing the severity of long‐term disability. Some of these studies indicated some benefit of HEMS for survival after major trauma, but other studies did not. The studies were of varying sizes and used different methods to determine if more people survived when transported by HEMS versus GEMS. Some studies included helicopter teams that had specialized physicians on board whereas other helicopter crews were staffed by paramedics and nurses. Furthermore, people transported by HEMS or GEMS had varying numbers and types of procedures during travel to the trauma center. The use of some of these procedures, such as the placement of a breathing tube, may have helped improve survival in some of the studies. However, these medical procedures can also be provided during ground ambulance transport. Data regarding safety were not available in any of the included studies. Road traffic and helicopter crashes are adverse effects which can occur with either method of transport.

Quality of the evidence

Overall, the quality of the included studies was low. It is possible that HEMS may be better than GEMS for people with certain characteristics. There are various reasons why HEMS may be better, such as staff having more specialty training in managing major injuries. But more research is required to determine what elements of helicopter transport improve survival. Some studies did not describe the care available to people in the GEMS group. Due to this poor reporting it is impossible to compare the treatments people received.

Conclusions

Based on the current evidence, the added benefits of HEMS compared with GEMS are unclear. The results from future research might help in better allocation of HEMS within a healthcare system, with increased safety and decreased costs.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Worldwide, unintentional injuries are responsible for over 3.9 million deaths and over 138 million disability‐adjusted life‐years (DALY) (Chandran 2010). Trauma currently accounts for 12% of the world's burden of disease and annually there are more than five million deaths due to injuries worldwide (CDC 2010; Krug 2002; Murray 1996). By 2020, it is estimated that 1 in 10 people will die from injuries (CDC 2010; Murray 1996).

Description of the intervention

Early reports from the Korean and Vietnam wars suggested a 2% increase in survival for casualties as the time to definitive care improved from five hours to one hour with prompt transport by helicopter to forward‐deployed surgical theaters (Baxt 1983; Baxt 1985; Bledsoe 2006; Cowley 1973; McNabney 1981; Shatz 2004; Taylor 2010). Based on the results of these wartime experiences, civilian helicopters were used for the first time in the 1970s to transport traumatically injured people to trauma centers (Kerr 1999; Wish 2005). In Germany, the Christoph 1 helicopter entered service in 1970, and services rapidly expanded to over seven rescue bases (Seegerer 1976). Today, the use of helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) for the transportation of people with trauma is common in most developed nations (Butler 2010; Champion 1990; Kruger 2010; Ringburg 2009a). Helicopters are capable of transporting people with major trauma significantly faster than ground units and the speed benefit is more pronounced as the distance from a trauma center increases. Nevertheless, research has questioned which traumatically injured people derive the greatest benefit from the utilization of this limited and resource‐intensive form of transportation (Bledsoe 2005; Bledsoe 2006; Cunningham 1998; DiBartolomeo 2005; Ringburg 2009a).

How the intervention might work

The use of HEMS is largely predicated on the concept of the 'golden hour' (Cowley 1979). Time may play a crucial role in the treatment of adults with major trauma, and delays in management could worsen prognosis. Helicopter transport can decrease transport times and may facilitate earlier, definitive treatment. Several studies have established that timely and advanced trauma care may help improve mortality figures by reversing hypoperfusion to vital organs (Cowley 1979; Sampalis 1999). In one study, the risk of death was found to be significantly increased for every 10‐minute increase in out‐of‐hospital time (Sampalis 1999). However, the origins and scientific evidence for the 'golden hour', while intuitively appealing, have been questioned as has the role of HEMS in the chain of survival for people who are critically injured (Lerner 2001).

Mortality from motor vehicle crashes is reduced when an organized system of trauma care is implemented, of which HEMS is often an important component (Nathans 2000). The risk of death may be reduced by 15% to 20% when care is provided in a trauma center (MacKenzie 2006; MacKenzie 2007). A level I trauma center provides the highest level of surgical and critical care for people with trauma. Level I trauma centers have 24‐hour surgical coverage, including in‐house coverage by orthopedic surgeons, neurosurgeons, plastic surgeons, and other specialists, in addition to an active research program and a commitment to regional trauma education. People with major trauma who require an operation may benefit from management at a level I trauma center, but it is unclear if earlier intervention and rapid assessment alone fully explain the survival benefit (Haas 2009). The mortality benefits resulting from admission to a level I trauma center may be due to the definitive surgical expertise available at these centers (Haut 2006), in addition to the advanced resources for critical care and rehabilitation services (Haut 2009). Furthermore, speed may not be the only contributory effect of HEMS in terms of mortality benefits for adults with major trauma. HEMS crews are typically composed of highly trained personnel, including experienced paramedics, critical care nurses, respiratory therapists, and, in some cases, physicians. Hence, any HEMS‐associated outcome benefit is likely to be the result of some combination of speed, expertise, and the role that HEMS programs have as part of integrated trauma systems (Thomas 2003). Transport of injured people remains a major goal for most HEMS programs (Thomas 2002); beneficial effects of specialized trauma care regarding morbidity and mortality may be mediated by HEMS.

Why it is important to do this review

Results supporting mortality benefits for adults with major trauma transported by HEMS have been inconsistent (Ringburg 2009a; Thomas 2002; Thomas 2004; Thomas 2007), resulting in substantial controversy in both the medical literature and the transportation safety arena. Many HEMS outcome studies have the limitations of small sample sizes, important heterogeneity, and other inadequate statistical methodologies. Some overviews of the literature have pointed to a clear positive effect on survival associated with HEMS transport (Ringburg 2009a), while others have maintained persistent skepticism about the beneficial impact of HEMS (Bledsoe 2006). The use of HEMS is not without potential risk. In addition to the risk to patients, HEMS flight crews have one of the highest mortality risks of all occupations (Baker 2006). For these reasons, a systematic review of the literature is warranted so that structured evidence may be produced to inform and improve clinical interventions, triage decisions, and public policies regarding HEMS. The results from this review may inform the design of subsequent randomized or nonrandomized trials through the identification of relevant subgroups of people with trauma who may benefit from HEMS transport.

Objectives

To determine if helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) transport, compared with ground emergency medical services (GEMS) transport, is associated with improved morbidity and mortality for adults with major trauma.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Eligible trials include randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and nonrandomized intervention studies.

Evidence for benefit or harm of HEMS was not hypothesized to be found with RCTs because HEMS has become a highly integrated component of many trauma systems; therefore, we also evaluated nonrandomized studies (NRS), which is in accordance with guidance from The Cochrane Collaboration for including NRS (Reeves 2011). We excluded case‐control studies as they are susceptible to different types of biases than other observational studies and allocation to groups is by outcome, which introduces further bias. We did not combine evidence from RCTs with that from NRS.

As NRS cover a wide variety of fundamentally different designs, we included only studies utilizing the best available designs. Studies had to include a comparison group consisting of a GEMS group with or without a comparison via a Trauma‐Related Injury Severity Score (TRISS)‐based analysis. TRISS is a logistic regression model that compares outcomes to a large cohort of people in the Major Trauma Outcomes Study (MTOS) (Champion 1990). As first utilized by Baxt in 1983, TRISS‐based comparisons are made with a three‐step process (Baxt 1983). First, the actual mortality of people transported by HEMS is compared with TRISS‐predicted mortality. Second, the mortality of people transported by GEMS is compared with TRISS‐predicted mortality. Third, the null hypothesis that actual survival is no different than TRISS‐predicted survival is tested for the HEMS cohort versus the GEMS cohort. For non‐United States (US) TRISS‐based studies, use of the standardized W statistic was required because the M statistic for non‐US populations may be below the cutoff for nonstandardized TRISS (Schluter 2010). An M statistic of at least 0.88 is considered acceptable for comparing non‐US populations with the MTOS cohort, based on case‐mix and injury severity. A W statistic indicates the number of survivors expected per 100 people treated. We tracked non‐US TRISS‐based studies that did not report the W statistic and examined them in a subgroup analysis. We also included TRISS studies reporting the Z statistic. A Z statistic of at least 1.96 indicates a potential survival benefit when one population is compared with the MTOS cohort (Champion 1990).

We included studies if other techniques, such as regression modeling or stratification, were used to control for confounding. Each included study had to provide a description of how the groups were formed. We excluded any study that did not compare two or more groups of participants. Groups were defined based on time or location differences or by naturally occurring variations in treatment decisions. For example, some studies examined groups with different crew configurations, different equipment, or different capabilities to perform invasive interventions.

We included both prospective and retrospective NRS. If parts of a retrospective study were conducted prospectively, we only included these studies if the study was described in sufficient detail to discern this. Included studies had to describe comparability between the groups assessed. For instance, the Injury Severity Score (ISS) varied between HEMS and GEMS groups in some studies.

There are many potential confounders that may be responsible for any positive or detrimental effect of HEMS. Potential confounders included:

different types of prehospital interventions (i.e. needle thoracentesis, cricothyrotomy, rapid‐sequence endotracheal intubation);

different levels of care at the receiving trauma center (e.g. integrated trauma system versus isolated rural hospital);

varying expertise of HEMS versus GEMS providers (i.e. different crew configurations);

age, gender of participants;

injury stratification (i.e. ISS or other score);

type of traumatic injury (i.e. blunt versus penetrating trauma; isolated traumatic brain injury (TBI) versus other types of trauma);

scene transport versus interfacility transport.

Types of participants

Adults with major trauma and age 16 years or older. We included studies that had less than 10% of children but controlled for age with regression or stratification methods.

We defined major trauma by an ISS of at least 15, which has been shown to be associated with a greater need for trauma care (Baker 1976; Kane 1985). In the event that the ISS was not reported, we considered alternative scoring systems or other definitions for major trauma such as a New Injury Severity Score (NISS) of at least 15 (Osler 1997). Since any individual Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) of at least four will result in an ISS of at least 15, this was also used to indicate major trauma if studies only reported AIS (Wyatt 1998). We included participants reported to have sustained 'major trauma', or a similar description that was nearly equivalent to an ISS of at least 15.

Studies of burn patients are not eligible for inclusion in the review.

Types of interventions

Transport of people with major trauma by HEMS compared with transport by GEMS.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Survival, as defined by discharge from the hospital.

Survival is the most consequential, most consignable, and least ambiguous variable used to express outcome in HEMS studies (Ringburg 2009a).

Secondary outcomes

Quality‐adjusted life years (QALYs).

Disability‐adjusted life years (DALYs).

Since the focus of this review was the evaluation of the benefits of HEMS in terms of morbidity and mortality, we did not consider economic outcomes. The financial costs and benefits associated with HEMS are complex and sufficiently important to warrant a separate study.

Search methods for identification of studies

In order to reduce publication and retrieval bias, we did not restrict our search by language, date, or publication status.

Electronic searches

We searched the following:

Cochrane Injuries Group Specialised Register (29 April 2015);

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (Issue 4 of 12, 2015);

MEDLINE (OvidSP) (1946 to April week 3 2015);

Embase Classic + Embase (OvidSP) (1947 to 29 April 2015);

CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (1982 to 29 April 2015);

ISI Web of Science: Science Citation Index Expanded (SCI‐EXPANDED) (1970 to April 2015);

ISI Web of Science: Conference Proceedings Citation Index‐Science (CPCI‐S) (1990 to April 2015);

ZETOC (accessed 29 April 2015);

OpenSIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe) (opensigle.inist.fr/) (accessed 29 April 2015);

National Library of Medicine's Health Services Research Projects in Progress (HSRProj) (wwwcf.nlm.nih.gov/hsr_project/home_proj.cfm) (accessed 29 April 2015).

We adapted the MEDLINE search strategy, where necessary, for use in other databases. Appendix 1 provides all search strategies.

Searching other resources

We screened reference lists in all relevant material found to identify additional published and unpublished studies and performed handsearches of secondary references.

We searched the following trials registries for published and unpublished studies:

Clinicaltrials.gov (www.clinicaltrials.gov) (accessed 29 April 2015);

Controlled Trials metaRegister (www.controlled‐trials.com) (accessed 29 April 2015);

World Health Organization (WHO) Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (apps.who.int/trialsearch/) (accessed 29 April 2015).

Data collection and analysis

We collated the search results and merged them into a single bibliographic database. We removed duplicates before screening the titles and abstracts.

Selection of studies

Two review authors (SG and RS) examined the electronic search results in order to reject material that did not meet any of the inclusion criteria. Three review authors (SG, CS, and RS) independently screened the remaining titles and abstracts for reports of possibly relevant trials. We marked each study as 'exclude', 'include', or 'uncertain'.

One of the other three review authors cross‐reviewed all titles or abstracts classified as 'exclude' and documented the reasons for exclusion. If a title was not clearly relevant, we retrieved the full‐text version. Reasons for exclusion included studies not pertaining to traumatically injured adults, studies with nonoriginal data, single case reports, lack of a control group or description of a comparison group, or other reasons, based on the rationale described above (see Characteristics of excluded studies table).

We retrieved all titles or abstracts classified as 'include' or 'uncertain' in full and assessed them using the recommendations provided in Chapter 13 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Reeves 2011).

We resolved disagreements by group consensus (SG, CS, RS, and ST). If further clarification was required, we attempted to contact the authors.

Data extraction and management

Three review authors (SG, CS, and RS) were each assigned one‐third of the included articles and they independently extracted information on study characteristics and the results. We resolved any uncertainty about study inclusion by group consensus. We developed, pilot tested, and used data extraction and study quality forms. Extracted data included: last name and first initial of the first author, publication year, study design, participants, duration of follow‐up, definition of participant population, data for each intervention‐outcome comparison, estimate of effect with confidence intervals (CI) and P values, key conclusions of study authors, and review author's comments. We entered data into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2014).

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (SG and RS) planned to assess risk of bias for included RCTs. We planned to evaluate six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias. The risk of bias in each category was to be judged as high risk, low risk, and unclear risk according to guidance in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We intended to resolve any disagreements by group consensus.

For NRS not conducted entirely prospectively, we assessed risk of bias with the Downs and Black quality assessment scale (Downs 1998). This is considered an acceptable tool for evaluating NRS (Deeks 2003). The Downs and Black assessment tool has five items for evaluating risk of bias in NRS and we used all five subscales. The total number of points for each subscale was 11 for reporting bias, 3 for external validity, 7 for internal validity, 6 for internal validity confounding and selection bias, and 5 for power. Thresholds were established to define 'low', 'unclear', and 'high' levels of bias. Scores met the definition for a 'low' risk of bias if the scores were: at least 8/11 for reporting bias, 3/3 for external validity, at least 5/7 for internal validity, at least 5/6 for internal validity confounding and selection bias, and at least 4/5 for power. Studies were at 'high' risk of bias if the scores were: 6/11 or less for reporting bias, 1/3 or less for external validity, 4/7 or less for internal validity, 3/6 or less for internal validity confounding and selection bias, and 2/5 or less for power. Scores between the 'low' and 'high' bias thresholds were scored as 'unclear'.

Measures of treatment effect

For the dichotomous outcome of mortality, we calculated summary risk ratios (RR) or log RRs using the generic inverse‐variance method, but only if the included studies had similar design features. For the continuous secondary outcomes (QALYs and DALYs), we planned to calculate mean differences (MD); however, no studies reporting these outcomes were found.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the individual participant.

Dealing with missing data

We attempted to contact the authors of included studies to request missing data. If the authors did not respond, we considered the data missing.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We explored possible sources of heterogeneity between studies, and constructed a forest plot. We assessed the forest plot visually for heterogeneity by examining overlap of CIs. We calculated an I2 statistic to determine the proportion of variation due to heterogeneity; we considered a value greater than 50% as an indicator of significant statistical heterogeneity and a value greater than 90% as an indicator of considerable heterogeneity. We also calculated a Chi2 statistic for heterogeneity, with a P value < 0.05 suggestive of significant heterogeneity.

Assessment of reporting biases

We generated a funnel plot and examined it visually to assess for potential publication bias. We anticipated difficulty in showing that all relevant studies could be identified because of poor indexing and inconsistent use of design labels by HEMS researchers. We read full papers to determine eligibility of studies that came into question.

Data synthesis

We presented a narrative synthesis of our review by summarizing the design characteristics, risk of bias, and results of the included studies. We commented extensively on how each study design or quality attribute affected the quantitative result. We discussed potential sources of bias in our review, in addition to our methods used to control for these potential biases.

We hypothesized that several factors relating to different study designs may have an important effect on the results from individual studies. We anticipated that some studies may have used a TRISS‐based analysis, which is based on a population from the MTOS, as a control group. The TRISS analysis, which is used extensively in trauma research, is the most commonly used tool for benchmarking trauma outcomes but the coefficients have not been updated since 2010 (Schluter 2010). TRISS is a weighted combination of participant age, ISS, and Revised Trauma Score (RTS), and was developed to predict a person's probability of survival (Ps) after sustaining a traumatic injury. As trauma care may have improved over time, the data from which the original coefficients were derived may not reflect present day survival. Furthermore, TRISS‐based studies may not be wholly representative of all trauma injury populations (Champion 1990). We considered these limitations in all of our interpretations and analyses of TRISS‐based studies. Since 1996, the Trauma Audit and Research Network in the UK has been used to collect and analyze data for people with trauma (Gabbe 2011). The developers of this trauma registry have formulated a case‐mix adjustment model that addresses some of the limitations of the TRISS model (TARN 2011). Like the TRISS, the Ps for each person can be accurately calculated using age, gender, Glasgow Coma Score (GCS), ISS, and an interaction term for age and gender (TARN 2011).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Any salutary effect of HEMS is likely to be the result of some combination of speed, crew configuration (i.e. medical expertise), and that HEMS programs are often an integral part of a comprehensive trauma system (Thomas 2003). Therefore, in our narrative review, we described salient aspects of the different studies that may have contributed to a multifactorial outcomes benefit or detriment.

To investigate the effects of the interventions more precisely, we describe the results of studies according to the methods used for analysis: 1. studies that used multivariate regression methods, 2. studies that used TRISS‐based methods, and 3. studies that used other methods for analysis. We specified a priori that we would conduct a subgroup analysis based on ISS.

Sensitivity analysis

We were able to conduct three sensitivity analyses which were specified a priori: interfacility transfers, TBI, and blunt trauma.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies table.

We scored each study according to the five domains of the Downs and Black risk of bias assessment tool (Downs 1998). Domain scores for each study are reported as the numerator in the risk of bias tables, with the denominator representing the maximum score for each domain.

Results of the search

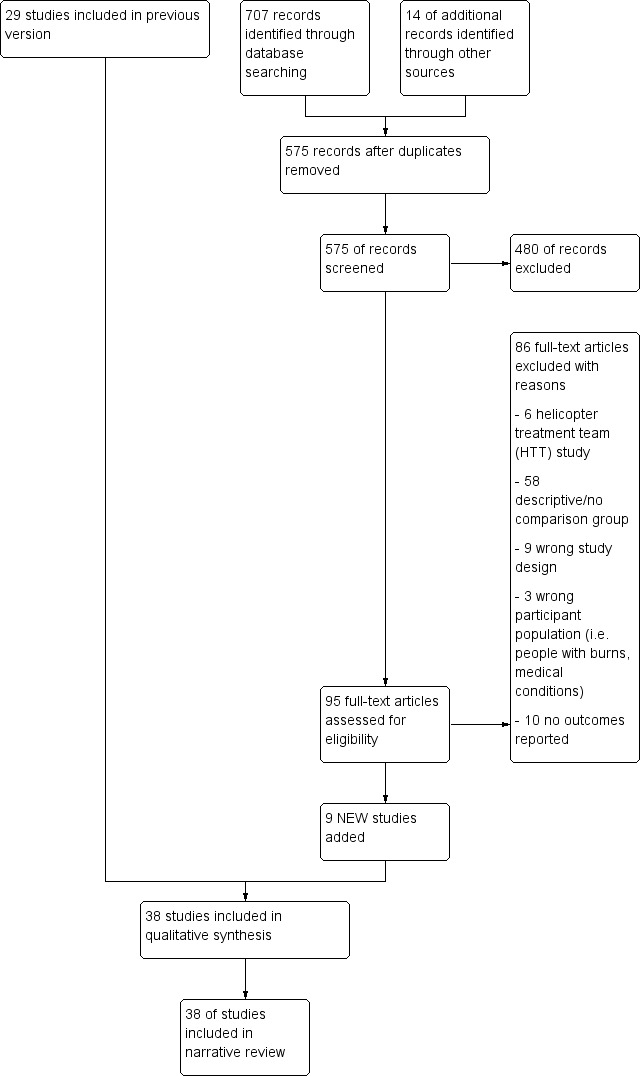

See Figure 2.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Thirty‐eight studies met the entry criteria for this review.

Included studies

All studies were NRS; we found no RCTS. The methods of analysis used in each study are summarised in Table 2. Nineteen studies included in the primary analysis used logistic regression to control for known confounders (Abe 2014; Andruskow 2013; Braithwaite 1998; Brown 2010; Bulger 2012; Cunningham 1997; Desmettre 2012; Frey 1999; Galvagno 2012; Giannakopoulus 2013; Koury 1998; Newgard 2010; Ryb 2013; Schwartz 1990; Stewart 2011; Sullivent 2011; Talving 2009; Thomas 2002; von Recklinghausen 2011). Eight studies in the primary analysis used TRISS methods (Andruskow 2013; Biewener 2004; Buntman 2002; Frink 2007; Giannakopoulus 2013; Nicholl 1995; Phillips 1999; Schwartz 1990). Two studies did not use TRISS methods or regression but relied on stratification to control for confounding factors (Nardi 1994; Weninger 2005). In Nardi 1994, all participants had an ISS of at least 15, and only data from people transported by HEMS and GEMS to level I centers were used. Weninger 2005 used extensive stratification by physiologic parameters such as blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and AIS to evaluate people transported by HEMS and GEMS.

1. Method of analysis used in the included studies.

| Number | Study Name | Data included in analysis 1.1.1 | Regression used | TRISS‐based method | Other analysis method used |

| 1 | Abe 2014 | X | X | ||

| 2 | Andruskow 2013 | X | X | X | |

| 3 | Bartolacci 1998 | X | X | ||

| 4 | Baxt 1983 | X | X | ||

| 5 | Baxt 1987 | X | X | ||

| 6 | Berlot 2009 | X | X | ||

| 7 | Biewener 2004 | X | X | ||

| 8 | Braithwaite 1998 | X | |||

| 9 | Brown 2010 | X | |||

| 10 | Brown 2011 | X | |||

| 11 | Bulger 2012 | X | X | ||

| 12 | Buntman 2002 | X | X | ||

| 13 | Cunningham 1997 | X | X | ||

| 14 | Davis 2005 | X | X | ||

| 15 | Desmettre 2012 | X | X | ||

| 16 | Di Bartolomeo 2001 | X | X | ||

| 17 | Frey 1999 | X | |||

| 18 | Frink 2007 | X | X | ||

| 19 | Galvagno 2012 | X | X | ||

| 20 | Giannakopoulus 2013 | X | X | X | |

| 21 | Koury 1998 | X | X | ||

| 22 | McVey 2010 | X | |||

| 23 | Mitchell 2007 | X | |||

| 24 | Moylan 1988 | X | |||

| 25 | Nardi 1994 | X | X | ||

| 26 | Newgard 2010 | X | |||

| 27 | Nicholl 1995 | X | X | ||

| 28 | Phillips 1999 | X | X | ||

| 29 | Rose 2012 | X | X | ||

| 30 | Ryb 2013 | X | |||

| 31 | Schiller 1988 | X | X | ||

| 32 | Schwartz 1990 | X | X | ||

| 33 | Stewart 2011 | X | X | ||

| 34 | Sullivent 2011 | X | X | ||

| 35 | Talving 2009 | X | X | ||

| 36 | Thomas 2002 | X | X | ||

| 37 | von Recklinghausen 2011 | X | X | ||

| 38 | Weninger 2005 | X | X |

We evaluated studies examining HEMS versus GEMS for blunt trauma or TBI separately in preplanned sensitivity analyses. Four studies examined outcomes for people sustaining blunt trauma (Bartolacci 1998; Baxt 1983; Desmettre 2012; Thomas 2002). Of the four blunt trauma studies, two used TRISS‐based methods (Bartolacci 1998; Baxt 1983) and two used logistic regression (Desmettre 2012; Thomas 2002). Six studies focused on TBI (Baxt 1987; Berlot 2009; Bulger 2012; Davis 2005; Di Bartolomeo 2001; Schiller 1988). Of these six studies, two were TRISS‐based (Baxt 1987; Di Bartolomeo 2001), two used logistic regression (Bulger 2012; Davis 2005), and two reported unadjusted mortality without stratification (Berlot 2009; Schiller 1988).

Four studies examining the role of people transferred by HEMS versus GEMS met the inclusion criteria for a sensitivity analysis that was planned a priori (Brown 2011; McVey 2010; Mitchell 2007; Moylan 1988). One transfer study used logistic regression (Brown 2011), and two used TRISS‐based methods (McVey 2010; Mitchell 2007). Another transfer study stratified people according to trauma score (Moylan 1988).

Excluded studies

See Characteristics of excluded studies table.

Several HEMS studies examined the effect of physician‐based helicopter treatment teams (HTTs). HTTs, used extensively in European systems in Germany and the Netherlands, rarely transport the person in the helicopter and we excluded these studies since the main objective of this review was to determine the effect of HEMS versus GEMS transport for traumatically injured adults. Only one study examined people with burns, and we excluded this study. Some studies used TRISS to compare the outcomes of people transported by HEMS with the MTOS cohort, but not GEMS, and we excluded these studies since they violated the TRISS methods for comparing HEMS with GEMS as originally described by Baxt 1983. Figure 2 describes additional study exclusions.

Risk of bias in included studies

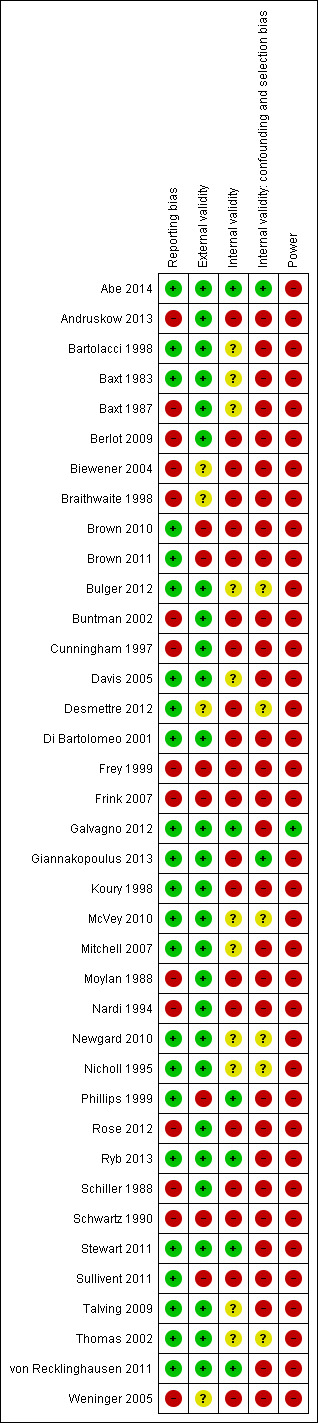

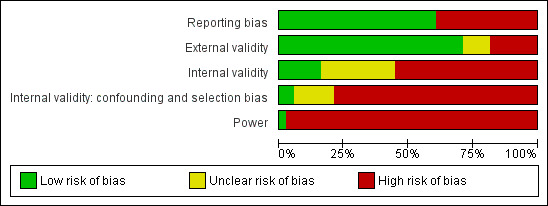

3.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies. Thirty‐eight studies are included in this review.

We assessed risk of bias with the Downs and Black assessment tool (Downs 1998). The highest possible score for this instrument is 32. The mean overall quality score for all included studies was 15.9 (range 6 to 27). Overall, the majority of studies were of low methodologic quality and no study had an overall 'low' risk of bias. Only two studies included a valid power calculation (Galvagno 2012; Thomas 2002). Thirteen studies (34.2%) had an overall quality score of at least 19 (Abe 2014; Bulger 2012; Davis 2005; Desmettre 2012; Di Bartolomeo 2001; Galvagno 2012; Giannakopoulus 2013; Newgard 2010; Nicholl 1995; Ryb 2013; Stewart 2011; Thomas 2002; von Recklinghausen 2011).

Allocation

All studies had an unclear or high level of selection bias. This was not a surprising finding considering the nature of the included studies; selection bias is an inherent risk of NRS.

One potential source of selection bias was injury severity; not all studies used ISS of at least 15 as an inclusion criterion, and some studies used other measures of injury severity. In Phillips 1999, participants were stratified by probability of survival (Ps) rather than ISS and, therefore, we only included people with a Ps less than 50% in our review. The study by Talving 2009 consisted of a participant population that had an ISS less than 15 in 74% of individuals; we only used data from the subgroup in this study with an ISS of at least 15. In Cunningham 1997, the mean ISS was lower than 15 in the GEMS group, but participants were stratified by ISS and logistic regression was used to adjust for differences in injury severity. Although ISS was not used in Moylan 1988, we included this study because participants were stratified by trauma score, and the mean trauma score was 8.7 for people transported by HEMS and 9.2 for people transported by GEMS (P value not reported).

Most studies attempted to control for confounding. Of the 28 studies in the primary analysis, including the four transfer studies in the prespecified sensitivity analysis, 14 studies (50%) used multivariable logistic regression. Only six studies reported regression diagnostics to ensure that the regression model was specified correctly (Abe 2014; Desmettre 2012; Galvagno 2012; Newgard 2010; Sullivent 2011; Thomas 2002). Four studies used advanced regression techniques including propensity scores (Abe 2014; Davis 2005; Galvagno 2012; Stewart 2011), instrumental variables (Newgard 2010), and techniques to control for clustering by trauma center (Thomas 2002).

Fourteen studies relied on a TRISS‐based analysis to compare both HEMS and GEMS outcomes against the MTOS cohort; however, TRISS‐based statistics were not reported consistently. The validity of TRISS methods has been questioned because the MTOS was established over two decades ago (Champion 1990), and changes in injury prevention and trauma care may preclude valid comparisons over time. Participants in the MTOS might have had a worse prognosis or different injury severity than contemporary trauma participants. To adjust for these potential differences, investigators using TRISS are encouraged to report an M statistic to ensure that severity and case‐mix is comparable (Schluter 2010). Only one study included in this review reported an M statistic (Buntman 2002). Eight TRISS studies were published after 2000 and it is possible that these populations might have differed significantly from the original MTOS cohort (Andruskow 2013; Biewener 2004; Buntman 2002; Di Bartolomeo 2001; Frink 2007; Giannakopoulus 2013; McVey 2010; Mitchell 2007). Di Bartolomeo 2001 attempted to control for case‐mix differences by comparing participants with an Italian MTOS cohort. Four studies reported the W statistic (Bartolacci 1998; Di Bartolomeo 2001; McVey 2010; Mitchell 2007). Five studies reported a Z statistic (Baxt 1983; Biewener 2004; Giannakopoulus 2013; Phillips 1999; Schwartz 1990), and four studies did not formally report any TRISS statistics (Andruskow 2013; Baxt 1987; Frink 2007; Nicholl 1995).

Crew configuration varied widely between studies and this may have had an effect on mortality since people transported by HEMS or GEMS might have been preferentially exposed to potential life‐saving interventions. For example, in one of the earliest and best‐known HEMS studies, Baxt 1983 reported a 52% reduction in mortality for the HEMS group. In this study, the HEMS crews consisted of an acute care physician who could perform advanced airway interventions, while the prehospital interventions authorized for the GEMS group were limited to advanced first aid and placement of an esophageal obturator airway. HEMS and GEMS crew configurations were not described in all studies and fewer than half of all studies included in the primary analysis described the type and frequency of prehospital interventions. The Characteristics of included studies table describes the crew configurations for the studies that provided this information. Sixteen studies included in the primary analysis had physicians as part of the HEMS crew (Abe 2014; Andruskow 2013; Bartolacci 1998; Baxt 1983; Baxt 1987; Berlot 2009; Davis 2005; Desmettre 2012; Di Bartolomeo 2001; Frink 2007; Giannakopoulus 2013; Nardi 1994; Nicholl 1995; Schwartz 1990; Thomas 2002; Weninger 2005). Twelve studies did not describe the crew configuration for HEMS or GEMS (Biewener 2004; Brown 2010; Bulger 2012; Cunningham 1997; Frey 1999; Galvagno 2012; Newgard 2010; Rose 2012; Ryb 2013; Schiller 1988; Stewart 2011; Sullivent 2011). Fourteen studies described the frequency and types of prehospital interventions performed between the HEMS and GEMS groups (Abe 2014; Andruskow 2013; Bartolacci 1998; Berlot 2009; Biewener 2004; Bulger 2012; Davis 2005; Desmettre 2012; Di Bartolomeo 2001; Giannakopoulus 2013; Nardi 1994; Phillips 1999; Schwartz 1990; Weninger 2005), whereas two studies only described the frequency of endotracheal intubation (Stewart 2011; Talving 2009).

Blinding

None of the included studies attempted to blind study participants to the intervention of HEMS versus GEMS. None of the included studies made an attempt to blind those measuring the main outcome of the intervention (HEMS versus GEMS). This resulted in either an 'unclear' or 'high' degree of bias, indicating poor levels of internal validity, for over 90% of the included studies. Detection bias was possible in the majority of included studies due to the retrospective nature of the study designs and because for people with an ISS of at least 15 mortality is more likely. It is also possible that deaths were recorded more frequently in the trauma registries that served as a primary source of data for most of the included studies. Survivors lost to follow‐up might not have been captured in the registries, biasing the results. Furthermore, mortality definitions differed among studies. Thirty‐day mortality may be different from 60‐day mortality, and this outcome is often difficult to assess. Most studies did not provide information on duration of follow‐up.

Incomplete outcome data

We did not include studies with incomplete outcome data in this review; however, attrition bias could not be accurately assessed due to the retrospective nature of the study designs. None of the studies adjusted the analyses for different lengths of follow‐up, and it is possible that not all outcomes were available. Losses to participant follow‐up were not taken into account in any of the included studies and this explains why over 80% of included studies were at high risk of bias in terms of internal validity. For the unadjusted analysis (Analysis 1.1), data were available for 28 of the 38 studies in the primary analysis.

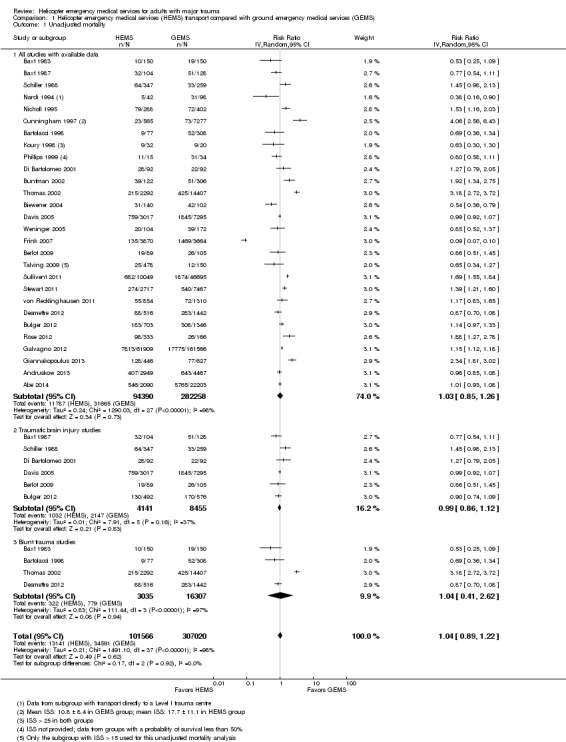

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) transport compared with ground emergency medical services (GEMS), Outcome 1 Unadjusted mortality.

Selective reporting

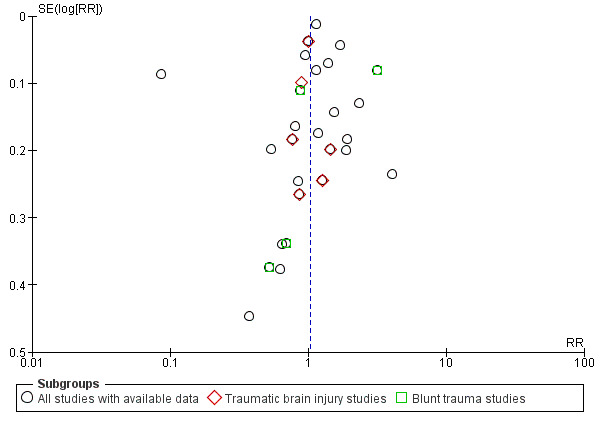

None of the studies fully controlled for all known confounders; 50% of all included studies had a low level of reporting bias and the remaining 50% had a high level of reporting bias. We assessed publication bias with a funnel plot (Figure 4). Trials were seen both to the right and left of the point of no effect, with no trials clustered around the line indicating no difference. There was an empty zone in the lower right quadrant of the plot. Therefore, it is possible that publication bias was present. This result might also be explained by the considerable clinical heterogeneity among the included studies. It is possible that smaller studies with results that were not statistically significant were never published.

4.

Funnel plot of comparison: helicopter emergency medical services (HEMS) versus ground emergency medical services (GEMS), outcome: 1.1 Overall unadjusted mortality.

Other potential sources of bias

Eleven studies had a minority of children included in the groups; however, the mean age in all of these studies was reported to be greater than 25 years. One study had 74% of people with an ISS less than 15 (Talving 2009); we included only the results from the subgroup with an ISS at least 15.

Effect estimates, and associated CIs in studies using regression techniques, might be inaccurate based on the availability of the data used to specify the regression model. For instance, five studies use the National Trauma Data Bank (USA) (Brown 2010; Brown 2011; Galvagno 2012; Ryb 2013; Sullivent 2011), and this data source is known to have a high proportion of missing data, especially for the physiological variables that the authors included as covariates (Roudsari 2008).

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Helicopter emergency medical services compared with ground emergency medical services for adults with major trauma.

| Helicopter emergency medical services compared with ground emergency medical services for adults with major trauma | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults (age > 15 years) with major trauma (ISS > 15) Settings: multinational Intervention: transportation to a trauma center by HEMS Comparison: transportation to a trauma center by GEMS | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| GEMS | HEMS | |||||

| Overall unadjusted mortality | Low risk population | RR 1.03 (0.85 to 1.26) | 376,648 | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low | Results could not be reliably combined for meta‐analysis due to considerable heterogeneity. The relative effect calculated here reflects unadjusted mortality only for studies that reported data enabling the calculation of a risk ratio. See text and Figure 1 (Analysis 1.1) for details | |

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Medium risk population | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| High risk population | ||||||

| ‐ | ‐ | |||||

| Quality‐adjusted life years | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies examining quality‐adjusted life years as an outcome met the inclusion criteria for this review |

| Disability‐adjusted life years | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | No studies examining disability‐adjusted life years as an outcome met the inclusion criteria for this review |

| Adverse events | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | None of the 38 included studies reported adverse events (such as GEMS or HEMS crashes) |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GEMS: ground emergency medical service; HEMS: helicopter emergency medical service; ISS: Injury Severity Score; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

See Table 1.

Primary outcome measure ‐ Survival (defined as discharge from the hospital)

Twenty‐eight of the included studies had extractable data on unadjusted mortality (Analysis 1.1). Considerable heterogeneity was observed as indicated by an I2 value of 98% and a highly statistically significant Chi2 test for heterogeneity (P value < 0.00001). Combining the results from these unequally sized and heterogeneous studies in a meta‐analysis would be likely to lead to a Yule‐Simpson effect (i.e. Simpson's paradox) and flawed conclusions. For example, when certain groups are combined without accounting for injury severity and other confounders, a correlation may be present. This correlation may disappear when the groups are stratified or when analyzed with regression techniques. Such a phenomenon appears to be evident in Analysis 1.1. Four studies that appeared to show a pronounced benefit for GEMS based on unadjusted mortality had opposite and statistically significant greater odds of survival for people transported by HEMS after adjusting for confounders with multivariable logistic regression (Galvagno 2012; Stewart 2011; Sullivent 2011; Thomas 2002) (Table 3). Another study that appeared to favor GEMS based on unadjusted mortality significantly showed no statistical difference between HEMS and GEMS after adjustment with regression (Cunningham 1997). Similarly, based on the unadjusted mortality from Buntman 2002 and Giannakopoulus 2013, one would infer that GEMS is superior to HEMS. However, after TRISS methods were applied, HEMS was shown to improve survival by 21.43% in Buntman 2002, and Giannakopoulus 2013 calculated 5.4 additional lives per 100 HEMS transports. Alternatively, several studies that appeared to support clearly HEMS based on unadjusted mortality had small sample sizes and the results from these studies might have been biased (Bartolacci 1998; Baxt 1983; Baxt 1987; Koury 1998; Nardi 1994).

2. Studies that utilized multivariate logistic regression to adjust for potential confounders.

| Study | Number of participants | Odds ratio for survival | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

| Abe 2014 | HEMS: 2090 GEMS: 22,203 |

1.23 | 1.02 to 1.49 | (3) |

| Andruskow 2013 | HEMS: 4989 GEMS: 8231 |

1.33 | 1.16 to 1.57 | (3) |

| Braithwaite 1998 | HEMS: 15,938 GEMS: 6473 |

Not reported (1) | Not reported (1) | < 0.01 (2) |

| Brown 2010 | HEMS: 41,987 GEMS: 216,400 |

1.22 | 1.18 to 1.27 | < 0.01 |

| Bulger 2012 | HEMS: 703 GEMS: 1346 |

1.11 | 0.82 to 1.74 | N.S. (3) |

| Cunningham 1997 | HEMS: 1346 GEMS: 17,144 |

Not reported (1) | Not reported (1) | (1) |

| Desmettre 2012 | HEMS: 516 GEMS: 1442 |

1.47 | 1.02 to 2.13 | 0.035 |

| Frey 1999 | HEMS: not reported GEMS: not reported |

1.34 | 0.91 to 1.8 | N.S. (3) |

| Galvagno 2012 | HEMS: 47,637 (7) GEMS: 111,874 (7) HEMS: 14,272 (8) GEMS: 111,874 (8) |

1.16 1.15 |

1.14 to 1.17 1.13 to 1.17 |

< 0.001 < 0.001 (9) |

| Giannakopoulus 2013 | HEMS: 446 GEMS: 627 |

Not reported (1) | Not reported (1) | (1) |

| Koury 1998 | HEMS: 168 GEMS: 104 |

1.6 | 0.77 to 3.34 | 0.24 |

| Newgard 2010 (4) | HEMS: 158 GEMS: 3498 |

1.41 | 0.68 to 2.94 | N.S. (3) |

| Ryb 2013 | HEMS: 29,472 GEMS: 162,950 |

1.78 | 1.65 to 1.92 | (3) |

| Schwartz 1990 | HEMS: 93 GEMS: 33 |

Not reported (1) | Not reported (1) | (1) |

| Stewart 2011 (5) | HEMS: 2739 GEMS: 6473 |

1.49 | 1.19 to 1.89 | 0.001 |

| Sullivent 2011 | HEMS: 10,049 GEMS: 46,695 |

1.64 | 1.45 to 1.87 | < 0.0001 |

| Talving 2009 (6) | HEMS: 1836 GEMS: 1537 |

1.81 | 0.55 to 5.88 | 0.33 |

| Thomas 2002 | HEMS: 2292 GEMS: 14,407 |

1.32 | 1.03 to 1.71 | 0.031 |

| von Recklinghausen 2011 | HEMS: 854 GEMS: 1310 |

1.75 1.87 |

0.86 to 4.2 (10) 0.94 to 3.66 (11) |

N.S. (3) |

GEMS: ground emergency medical service; HEMS: helicopter emergency medical service; N.S.: not significant.

(1) Effect estimate and 95% confidence interval not reported.

(2) Statistically significant effect on survival (in favor of HEMS) when HEMS analyzed as interaction between HEMS and ISS ranges of 16‐60.

(3) P value not reported.

(4) Instrumental variables analysis.

(5) Cox proportional hazards regression, including a propensity score as a confounding covariate.

(6) Adjusted odds ratio for subgroup with ISS > 15.

(7) Data for level I trauma centers.

(8) Data for level II trauma centers.

(9) Results of propensity score matching logistic regression analysis.

(10) ISS 16‐24 group, P value and n not reported.

(11) ISS 25‐75 group, P value and n not reported.

Additionally, it is important to understand that four studies did not provide raw data for calculation of unadjusted mortality, and this may have influenced the overall relative risk of unadjusted mortality (Brown 2010; Frey 1999; Newgard 2010; Schwartz 1990). Three of these studies were regression‐based and all three indicated a statistically significantly improved odds of survival (Brown 2010; Frey 1999; Newgard 2010). Schwartz 1990 used a TRISS analysis to demonstrate an improvement in predicted survival for HEMS but not GEMS, a finding that was contrary to the results from an unadjusted analysis; a similar result was observed in a more recent study by Giannakopoulus 2013. Due to the considerable clinical and methodological heterogeneity found in the included studies, a pooled estimate of effect is not presented.

Subgroup analyses

To investigate the effects of the interventions more precisely, we describe the results of studies according to the methods used for analysis: 1. studies that used multivariate regression methods, 2. studies that used TRISS‐based methods, and 3. studies that used other methods for analysis.

1. Studies that used multivariate regression methods

Nineteen studies used multivariate regression techniques to adjust for known confounders (Abe 2014; Andruskow 2013; Braithwaite 1998; Brown 2010; Bulger 2012; Cunningham 1997; Desmettre 2012; Frey 1999; Galvagno 2012; Giannakopoulus 2013; Koury 1998; Newgard 2010; Ryb 2013; Schwartz 1990; Stewart 2011; Sullivent 2011; Talving 2009; Thomas 2002; von Recklinghausen 2011). Table 3 shows the effect estimates and 95% CIs from these 19 studies (effect estimates and CIs were not available for Cunningham 1997, Giannakopoulus 2013 and Schwartz 1990). The results from three of these studies focused exclusively on people with blunt trauma (Braithwaite 1998; Schwartz 1990; Thomas 2002), and these studies are summarized in the section below 'Sensitivity analysis, blunt trauma'. The results from Andruskow 2013 and Giannakopoulus 2013 are described in the section detailing the results from TRISS‐based studies since this was the primary analysis performed in these studies.

Abe 2014 utilized the Japan Trauma Data Bank (JTDB) to examine retrospectively 2090 HEMS transports and 22,203 GEMS transports between 2004 and 2011. The study used three different logistic regression techniques, adjusting for age, sex, type of trauma, ISS, and prehospital treatments. HEMS were staffed by a physician and nurse and GEMS were staffed by an emergency medical technician (EMT) and firefighter. In all three logistic regression models, HEMS was independently associated with statistically significantly improved survival to hospital discharge when compared with GEMS.

Brown 2010 analyzed 41,987 HEMS transports and 216,400 GEMS transports from the 2007 National Trauma Data Bank. When adjusting for ISS, age, gender, injury mechanism, vital signs, type of trauma center, and urgency of operation, HEMS was associated with a statistically significant greater odds of survival to hospital discharge (odds ratio (OR) 1.22; 95% CI 1.18 to 1.27; P value < 0.01).

Bulger 2012 and researchers from the North American Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium conducted a retrospective analysis from two RCTs that enrolled people with severe TBI or hypovolemic shock. The study analyzed 2049 people in both the shock and TBI cohorts. More people had penetrating trauma in the GEMS group (21.2%) compared with the HEMS group (6%). Mean ISS was higher in HEMS group (30.1) compared with the GEMS group (22.8; P value < 0.0001). Multivariable logistic regression, adjusting for age, mechanism, GCS, hypotension, heart rate, ISS, site of enrolment, and AIS, was used to calculate odds of 24‐hour and 28‐day survival. While the OR for overall survival was 1.11 favoring HEMS, this result was not statistically significant (95% CI 0.82 to 1.51). Nonsignificant results were found independently when the shock and TBI cohorts were analyzed separately. This study had a total number of people of 2049; yet, to detect up to a 5% survival advantage in either the HEMS or GEMS cohort, with 80% power at the 5% significance level, at least 2526 participants would have to be enrolled; a far greater number of participants would have to be enrolled to detect even smaller differences in survival. Of the 703 people transported by HEMS, 60% came from three trauma centers.

Cunningham 1997 found that HEMS was associated with statistically significant survival benefit for people with mid‐range, but not higher, acuity. People with an ISS of 21 to 30 had 56% survival in the HEMS group versus 37.4% survival in the GEMS group. For people with an ISS of 31 to 40, 80% of the HEMS group survived versus 62.8% of the GEMS group. However, for the most severely injured people with a Ps less than 90%, the HEMS group had 66.9% survival and the GEMS group had 81.9% survival.

Desmettre 2012 studied the impact of HEMS versus GEMS on mortality of people with severe blunt trauma. This French study included 1958 participants, of which 74% were transported by GEMS and 26% by HEMS. Although crew configurations both consisted of physicians, HEMS crews were staffed by a team that included an emergency physician from a regional University hospital. Multivariable logistic regression was performed, controlling for several prehospital physiologic and injury‐specific variables. Interaction terms between mode of transport and other independent variables were assessed in the regression model. People treated by HEMS crews were more likely to be treated aggressively with interventions such as endotracheal intubation, administration of fluids, treatment with vasopressors, and blood product transfusion. After adjustment, the risk for survival was greater in the HEMS group (OR 1.47; 95% CI 1.02 to 2.13; P value = 0.035).

Frey 1999 reported in an abstract on 12,233 people involved in motor vehicle crashes admitted to trauma centers in Pennsylvania, PA, USA. There was no difference in survival between transport by HEMS or GEMS (OR 1.34; 95% CI 0.91 to 1.80; P value not reported). Reasons for a lack of statistical significance may be due to residual confounding, transport of people with lower severity trauma, and the fact that this study included only people involved in motor vehicle crashes. Recent advances in vehicle safety may partially explain why no benefit was found when HEMS was compared with GEMS.

Galvagno 2012 used the National Trauma Data Bank to analyze 223,475 people transported by HEMS or GEMS to a level I or level II trauma center. Outcomes were assessed with multiple regression methods. After a propensity score matching was used in a logistic regression, and after outcomes were assessed in an analysis stratified by type of trauma center, people transported by HEMS were statistically significantly more likely to survive to hospital discharge compared with people transported by GEMS. The effect estimate (OR) was more conservative after propensity score matching as compared with two standard logistic regression and an analysis using generalized estimating equations (GEE) to control for clustering by trauma center. The study did not account for crew expertise, distance, time, and prehospital interventions.

A retrospective cohort study by Koury 1998 found no difference in survival in people with an ISS of at least 25 and transported by HEMS (OR 1.6; 95% CI 0.77 to 3.34; P value = 0.24). This study controlled for confounding factors such as age, type of trauma, ISS, hospital length of stay, and length of emergency room stay. This study also included some children (14% to 16.7%) and interfacility transfers, although these factors were adjusted for in the regression model. The relatively small number of participants in Koury et al (n = 272) may explain the wide CI for the effect estimate. Moreover, a higher ISS cutoff was used (≥ 25) and the authors acknowledged that the study was likely to be underpowered to find a difference between HEMS and GEMS.

Newgard 2010 conducted a secondary analysis of a prospective cohort registry study of adults with trauma transported by 146 emergency medical service (EMS) agencies to 51 level I and II trauma centers in North America. A multivariate regression model using instrumental variables was used to study the association of EMS intervals and mortality among people with trauma with field‐based physiologic abnormalities, using distance from a trauma center as the instrument. There was no difference in survival with the use of HEMS (OR 1.41; 95% CI 0.68 to 2.94; P value not reported) in the multivariate model. The primary objective of this study was to test the association of EMS intervals and mortality among people with trauma (e.g. the 'golden hour' concept) and HEMS was only analyzed as one independent variable that might have influenced outcome.

Ryb 2013 used data from 2007 available in the National Trauma Data Bank to examine the effect of HEMS on trauma survival across different subpopulations of people with trauma in relation to injury severity, degree of physiologic derangement, and transport time. The study analyzed 192,422 people with complete data. Using multiple logistic regression models adjusting for ISS, levels of physiologic derangement, and different transport times, HEMS was statistically significantly associated with improved survival (OR 1.78; 95% CI 1.65 to 1.92). When stratified by RTS as a marker of physiologic instability, people transported by HEMS with worse scores had significantly higher adjusted odds of survival. The limitations of the National Trauma Data Bank must be considered when interpreting the results from this study (see Other potential sources of bias).

Stewart 2011 calculated a propensity score based on prehospital variables (age, gender, mechanism of injury, respiratory rate, anatomic triage criteria, intubation, level of prehospital care, and road distance to a trauma center) and hospital variables (RTS on arrival at emergency room, ISS, time from receipt of EMS call to arrival at emergency room, time in minutes from receipt of the first EMS call to time of death). This study included 10,184 people in the state of Oklahoma, USA who were admitted to one level I trauma center or one of two level II trauma centers. The propensity score was used as a single confounding covariate in a Cox multivariable proportional hazards regression model to determine the association between mode of transport and mortality. Overall, people transported by HEMS had a statistically significantly higher HR for survival compared with people transported by GEMS (HR for improved survival 1.49; 95% CI 1.19 to 1.89; P value = 0.001). In the most severely injured people (RTS of 3 or less at the scene), the mode of transport was not associated with improved survival.

Sullivent 2011 used multivariate logistic regression to examine the association between mortality and transportation between HEMS and GEMS. The 2007 National Trauma Data Bank was used for this study, with 148,270 records of people treated at 82 participating trauma centers in the USA. The authors stratified the regression analysis results by three age categories: 18 years and over, 18 to 54 years, and 55 years and over. Overall, HEMS transport conferred a statistically significant mortality benefit (OR 1.64; 95% CI 1.45 to 1.87; P value < 0.0001), although in the age category 55 years and over, there was no difference in survival between HEMS and GEMS (OR 1.08; 95% CI 0.88 to 1.75; P value = 0.42).

Talving 2009 retrospectively examined data for 1836 people transported by HEMS or GEMS in a predominantly urban environment. In the subgroup of people with an ISS of at least 15, there was no difference in survival between people transported by HEMS or GEMS (OR 1.81; 95% CI 0.55 to 5.88; P value = 0.33). An analysis of four high‐risk subgroups was conducted in this study. People with ISS of at least 15, penetrating trauma, a head AIS of at least 4, or systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg did not experience a statistically significantly benefit from HEMS transport in a multivariable analysis adjusting for age, vital signs, injury mechanism, and injury severity. The lack of benefit in this study may be due to the geographical location of the HEMS program that was studied. The region serviced by HEMS was predominantly urban and HEMS was used when transport times exceeded 30 minutes. Thirty minutes may not be a clinically important cutoff to justify HEMS use, and patient over‐triage was likely in this study.

von Recklinghausen 2011 compared rural GEMS and HEMS in a retrospective cohort of 2164 participants at one level I trauma center in the northeastern USA. There was no difference in survival among people transported by HEMS or GEMS with ISS scores of 16 to 24 (OR 1.75; 95% CI 0.86 to 4.2). Among people with ISS of 25 to 75, there was also no difference in survival (OR 1.87; 95% CI 0.94 to 3.66). Information about crew expertise and en route interventions was not available. With a low mortality in both the HEMS (6.46%) and GEMS group (5.5%; P value = 0.35), the study was not likely powered to find a statistically significant difference in survival.

2. Studies that used Trauma‐Related Injury Severity Score‐based methods

Fourteen studies used TRISS‐based methods to compare survival for HEMS versus GEMS against the standard of the MTOS cohort (Andruskow 2013; Bartolacci 1998; Baxt 1983; Biewener 2004; Buntman 2002; Frink 2007; Giannakopoulus 2013; Nicholl 1995; Phillips 1999; Schwartz 1990).

In Andruskow 2013, outcomes from physician‐led HEMS and GEMS teams were compared using TRISS methodology. People transported by HEMS had higher ISS compared with people transported by GEMS (26.0 with HEMS versus 23.7 with GEMS; P value < 0.001). The people in the HEMS group were also treated more aggressively with more frequent endotracheal intubation, chest thoracostomy tube placement, and treatment with vasopressors. Predicted mortality according to TRISS was lower in both HEMS and GEMS groups. For people transported to level I trauma centers, the standardized mortality ratio (SMR) was significantly decreased in the HEMS group compared with the GEMS group (0.647 with HEMS versus 0.815 with GEMS; P value = 0.002). The authors performed a multivariable regression analysis and found an improved odds of survival for the HEMS group compared with the GEMS group when 11 confounding variables were included in the regression model (OR for survival in HEMS group: 1.33; 95% CI 1.16 to 1.57). The study reported neither the M or W statistics.

The results from Bartolacci 1998 are discussed in the preceding section ('Studies that used multivariate regression methods'). There was a significant difference between observed and expected survivors for people transported by HEMS (Z = 3.38; P value < 0.0001). The W statistic reported in this study was 11.88, which suggests nearly 12 expected survivors for every 100 people flown; but the M statistic was 0.52, which is less than the acceptable 0.88 threshold for comparing populations (Schluter 2010). The nonsignificant M statistic indicated that there was a higher proportion of people with a low Ps in the HEMS group compared with the MTOS cohort.

Baxt 1983 studied 300 consecutive HEMS and GEMS transports to a level I trauma center over a 30‐month period. Although the actual Z statistic was not reported, a 52% reduction in predicted mortality occurred in the HEMS group (P value < 0.001). Overall, 20.62 people were predicted to die in the HEMS group based on a comparison with the MTOS cohort, but only 10 people died. In the GEMS group, 14.79 people were predicted to die but 19 died. Major improvements in survival were most pronounced for the more seriously injured participant groups. For people with a 24% or less chance of survival, four people transported by HEMS died when 7.03 were predicted to die; in the GEMS group, six people died when 7.03 were predicted to die.

Biewener 2004 assessed the impact of rural HEMS versus urban GEMS in 403 people with trauma in the Dresden region in Germany. The study used TRISS‐based methods only to compare HEMS versus GEMS for people transported directly from the scene to a level I trauma center. No TRISS statistics were reported. In the HEMS groups, the TRISS analysis identified 27 unexpected survivors and four unexpected deaths out of the 140 people transported. In the GEMS group there were 13 unexpected survivors and two unexpected deaths from the people transported. The TRISS evaluation did not identify any differences between the HEMS and GEMS groups in terms of survival. In a multivariate regression model, there was also no difference in survival (OR 0.94; 95% CI 0.38 to 2.34; P value not reported).

Buntman 2002 reported the results from a prospective database analysis of 428 people transported by HEMS and GEMS in South Africa. Survival rates in the HEMS and GEMS groups were compared with TRISS‐predicted survival rates, and people with a Ps less than 65% were more likely to survive if transported by HEMS. Overall, 38.15 people in the HEMS group were expected to die and 39 actually died (Z = 0.223), and 38.96 people in the GEMS group were predicted to die and 51 actually died (Z = 2.939). The difference in the Z statistic between the HEMS and GEMS groups was 1.921 (P value < 0.05) indicating a greater chance for survival in the HEMS group than the GEMS group. It should be noted that the M statistic reported in this study was 0.618 for the HEMS group and 0.867 for the GEMS group; both groups did not meet the threshold for accurate comparison to the MTOS cohort.

Frink 2007 retrospectively evaluated 7534 people transported by HEMS and GEMS in Germany and used a TRISS prediction of survival to demonstrate a survival benefit for people transported by HEMS, though no specific TRISS statistics were reported in this study. Overall mortality was 34.9% in the HEMS group versus 40.1% in the GEMS group (P value < 0.01), but this difference was only found in people with an ISS less than 61.

Giannakopoulus 2013 analyzed 1073 people with an ISS of at least 16 and transported directly from the scene by HEMS or GEMS. HEMS crews consisted of a physician capable of providing advanced airway management and limited surgical interventions. The study did not describe the configuration of the GEMS crew. There was a longer on‐scene time in the HEMS group compared with the GEMS group (27.1 minutes with HEMS versus 20.7 minutes with GEMS, P value < 0.001), and the HEMS population was younger (mean age: 40.5 with HEMS versus 49.3 with GEMS; P value < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the types of injuries. Unadjusted analysis indicated a higher mortality in the HEMS group (28.7% with HEMS versus 12.3% with GEMS, P value < 0.001). However, people in the HEMS group had a significantly higher ISS. The M statistic showed that the population in this study was not comparable to the original TRISS MTOS population, likely because of the higher ISS (> 16) used as an inclusion criteria for this study. The Z statistic showed a positive difference between the observed and the estimated survival for the HEMS group (P value < 0.005) indicating that the actual survival for the HEMS group was higher than predicted by TRISS; there was no difference in the predicted and the actual survival in the GEMS group. When the RTS reached 9 or less, the difference in survival between the groups increased, demonstrating an increased chance of survival for people transported by HEMS. The authors concluded that 5.4 people with multiple traumatic injuries were saved for every 100 HEMS deployments.

Nicholl 1995 compared 337 people transported by HEMS and 466 people transported by GEMS in the UK using the TRISS methodology. The number of HEMS deaths exceeded the MTOS norms by 15.6%, compared with an excess of 2.4% in the GEMS group. No TRISS‐specific statistics were reported and overall mortality for people with an ISS of at least 15 was 51% in the HEMS group and 44% in the GEMS group (not statistically significant, P value not reported). There was no difference in survival between people transported by HEMS compared with GEMS, who had an ISS of 16 to 24 (OR for improved survival 1.25; 95% CI 0.44 to 3.33) or an ISS of 25 to 40 (OR for improved survival 1.11; 95% CI 0.83 to 1.43). In both of these ISS groups, there were fewer than 60 people in each group, thus the wide CIs are likely due to the relatively small number of people within each subgroup.

Phillips 1999 used the TRISS methodology to compare mortality rates of 792 people with trauma transported by HEMS or GEMS in Texas, USA. The Z statistic was not significant for actual versus predicted deaths for HEMS (Z = 0.40) or GEMS (Z = 0.151). The HEMS group sustained 15 deaths compared with a TRISS‐predicted rate of 16.44 deaths; the GEMS group sustained 41 deaths compared with a TRISS‐predicted rate of 39.11 deaths; neither result was statistically significant.

Schwartz 1990 reported on a series of people with blunt trauma transported by HEMS or GEMS to a single level I trauma center in Connecticut, USA, during 1987 and 1988. This study used TRISS methodology, but did not report W, Z, and M statistics. HEMS crews were comprised of highly trained providers, including a physician, nurse, and respiratory therapist, while GEMS crews were comprised of an EMT and paramedic. People transported by HEMS had a Ps of 2.23 standard deviations better than the national norm, while people transported by GEMS had a survival ‐2.69 standard deviations below the national norm. More people in the HEMS group were intubated (42% with HEMS versus 3% with GEMS) and more people in the HEMS group were treated with a pneumatic antishock garment (56% with HEMS versus 30% with GEMS). There was no significant difference in the prehospital times for either HEMS or GEMS once crews had arrived at the scene.

3. Studies using other methods to adjust for confounding

Three additional studies that did not use regression techniques or a TRISS‐based analysis met the inclusion criteria (Nardi 1994; Rose 2012; Weninger 2005).

The results from Nardi 1994 are summarized in the 'Blunt trauma studies' section. This study did not utilize TRISS‐based methods or regression techniques.

In Weninger 2005, people transported by HEMS and by GEMS were similar in age, sex, and injury severity. People in the HEMS group had more frequent administration of intravenous fluids, endotracheal intubation, and chest tube placement than people in the GEMS group. Twenty of 104 (19.2%) people transported by HEMS died (19.2%) versus 39 of 172 (22.7%) people transported by GEMS (P value not reported).

Rose 2012 performed a stratified analysis of 1028 HEMS and 1443 GEMS transports in Alabama, USA. The mode of transport was stratified only by ISS and mean miles to a trauma center. HEMS did not improve survival for people with high ISS (> 30) or in people with lower ISS (< 10) transported from rural areas. The study made no adjustments for crew expertise, prehospital interventions, types of injuries, physiologic data, or other variables. This study was limited by considerable low methodological quality, and did not employ descriptive statistics for between‐group comparisons.

Sensitivity analyses

1. Traumatic brain injury studies

Five studies focused on the role of HEMS versus GEMS transport for TBI (Baxt 1987; Berlot 2009; Davis 2005; Di Bartolomeo 2001; Schiller 1988). These studies analyzed 11,528 people and data were available from all five studies to calculate unadjusted mortality. There was moderate heterogeneity in this subgroup (Chi2 = 6.80; I2 = 41%). Based on the raw mortality data from these five trials, there was no association with improved survival (RR 1.02 in favor of HEMS; 95% CI 0.85 to 1.23).

Davis 2005 studied 10,314 people transported by HEMS or GEMS. They used propensity scores to account for the variability in selection of people undergoing HEMS versus GEMS transport and used a multivariate regression model to adjust for age, sex, mechanism of injury, hypotension, GCS, AIS, and ISS. There was an improved odds of survival for people transported by HEMS after adjustment for potential confounders (OR 1.90; 95% CI 1.60 to 2.25; P value < 0.0001). When stratified by GCS, there was a statistically significant survival benefit observed only for the GCS group with a score of 3 to 8 (OR 1.84; 95% CI 1.51 to 2.23; P value < 0.001).

Di Bartolomeo 2001 utilized a population‐based, prospective cohort design to investigate the effect of two different patterns of prehospital care in the Fiuli‐Venezia Giulia region of Italy. The HEMS group was staffed by a physician and the GEMS group was staffed by a nurse. Significantly more people in the HEMS group received chest tube placement, placement of intravenous lines, and advanced modes of ventilation, including endotracheal intubation. After controlling for transport mode, gender, age, ISS, and RTS, there was no difference in survival between HEMS and GEMS (OR not reported; P value = 0.68). For people requiring urgent neurosurgery, there was no difference in survival between HEMS and GEMS (OR 1.56; 95% CI 0.38 to 6.25; P value not reported).

Schiller 1988 was a retrospective cohort of 606 people in a primarily urban setting in Phoenix, AZ, USA. Unadjusted mortality was statistically significantly higher for HEMS (18%) versus GEMS (13%) (P value < 0.05). All participants in this cohort had blunt trauma and 80% had a TBI. All participants had an ISS between 20 and 39. All participants were transported to a level I trauma center but the study did not describe crew configurations.

Baxt 1987 studied the impact of HEMS versus GEMS for 128 consecutive participants with TBI in San Diego, CA, USA. HEMS crews consisted of an attending physician and nurse, and GEMS crews consisted of EMTs capable of providing only basic life support. Overall unadjusted mortality was 31% in the HEMS group and 40% in the GEMS group (P value < 0.0001). For GCS scores of 5, 6, or 7 the GEMS group had improved mortality; however, for GCS scores of 3 or 4, mortality was statistically significantly lower for the HEMS group (52%) versus the GEMS group (64%) (P value not reported for this subgroup).