Abstract

Background

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) or varicose ulcers are the final stage of chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), and are the most common type of leg ulcer. The development of VLUs on ankles and lower legs can occur spontaneously or after minor trauma. The ulcers are often painful and exudative, healing is often protracted and recurrence is common. This cycle of healing and recurrence has a considerable impact on the health and quality of life of individuals, and healthcare and socioeconomic costs. VLUs are a common and costly problem worldwide; prevalence is estimated to be between 1.65% to 1.74% in the western world and is more common in adults aged 65 years and older. The main treatment for a VLU is a firm compression bandage. Compression assists by reducing venous hypertension, enhancing venous return and reducing peripheral oedema. However, studies show that it only has moderate effects on healing, with up to 50% of VLUs unhealed after two years of compression. Non‐adherence may be the principal cause of these poor results, but presence of inflammation in people with CVI may be another factor, so a treatment that suppresses inflammation (healing ulcers more quickly) and reduces the frequency of ulcer recurrence (thereby prolonging time between recurrent episodes) would be an invaluable intervention to complement compression treatments. Oral aspirin may have a significant impact on VLU clinical practice worldwide. Evidence for the effectiveness of aspirin on ulcer healing and recurrence in high quality RCTs is currently lacking.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of oral aspirin on the healing and recurrence of venous leg ulcers.

Search methods

In May 2015 we searched: The Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register; The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library); Ovid MEDLINE; Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations); Ovid EMBASE and EBSCO CINAHL. Additional searches were made in trial registers and reference lists of relevant publications for published or ongoing trials. There were no language or publication date restrictions.

Selection criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared oral aspirin with placebo or no drug intervention (in the presence or absence of compression therapy) for treating people with venous leg ulcers. Our main outcomes were time to complete ulcer healing, rate of change in the area of the ulcer, proportion of ulcers healed in the trial period, major bleeding, pain, mortality, adverse events and ulcer recurrence (time for recurrence and proportion of recurrence).

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies for inclusion, extracted data, assessed the risk of bias of each included trial and assessed overall quality of evidence for the main outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' table.

Main results

The electronic search located 62 studies. We included two RCTs of oral aspirin (300 mg/daily) given in addition to compression compared with compression and placebo, or compression alone. To date, the impact of aspirin on VLUs has been examined by only two randomised clinical trials, both with a small number of participants. The first RCT was conducted in the United Kingdom (n=20) and reported that daily administration of aspirin (300mg) in addition to compression bandages increased both the rate of healing, and the number of participants healed when compared to placebo in addition to compression bandaging over a four month period. Thirty‐eight per cent of the participants given aspirin reported complete healing compared with 0% in the placebo group . Improvement (assessed by reduction in wound size) occurred in 52% of the participants taking aspirin compared with 26% in those taking placebo). The study identified potential benefits of taking aspirin as an adjunct to compression but the sample size was small, and neither the mechanism by which aspirin improved healing nor its effects on recurrence were investigated.

In 2012 an RCT in Spain (n=51) compared daily administration of aspirin (300mg) in addition to compression bandages with compression alone over a five month period. There was little difference in complete healing rates between groups (21/28 aspirin and 17/23 compression bandages alone) but the average time to healing was shorter (12 weeks in the treated group vs 22 weeks in the compression only group) and the average time for recurrence was longer in the aspirin group (39 days: [SD 6.0] compared with 16.3 days [SD 7.5] in the compression only group). Although this trial provides some limited data about the potential use of aspirin therapy, the sample size (only 20 patients) was too small for us to draw meaningful conclusions. In addition, patients were only followed up for 4 months and no information on placebo was reported.

Authors' conclusions

Low quality evidence from two trials indicate that there is currently insufficient evidence for us to draw definitive conclusions about the benefits and harms of oral aspirin on the healing and recurrence of venous leg ulcers. We downgraded the evidence to low quality due to potential selection bias and imprecision due to the small sample size. The small number of participants may have a hidden real benefit, or an increase in harm. Due to the lack of reliable evidence, we are unable to draw conclusions about the benefits and harms of oral daily aspirin as an adjunct to compression in VLU healing or recurrence. Further high quality studies are needed in this area.

Plain language summary

Oral aspirin for venous leg ulcers

Background Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are the most common type of leg ulcers (sores) and are caused by poor blood flow in the veins of the legs (chronic venous insufficiency). Chronic venous insufficiency leads to high blood pressure in the veins (venous hypertension), which triggers many alterations in the skin of the leg. Leg ulcers are the end stage of these alterations. VLUs can occur spontaneously or after minor trauma, they are often painful and produce heavy exudation (loss of fluid). VLUs are a major health problem because they are quite common, tend to become chronic (long‐lasting) and also have a high tendency to recur. They affect older people more frequently, have high costs of care, and a high individual and social burden for those affected.

Compression therapy, in the form of a firm bandage over the leg, which aids the flow of blood in the veins, is a well‐established treatment for VLUs. However, studies show that compression has only moderate effects on healing, with up to 50% of VLUs remaining unhealed after two years of compression, possibly due to a prolonged inflammation process. A better understanding of the degenerative changes in the skin of the leg in people with VLUs and the chronic inflammation process involved in them, has led researchers to test different medicines that could improve the treatment of this condition. Aspirin has some well‐known properties including: pain relief (analgesic), reducing inflammation and fever, and stopping blood cells from clumping together, which prevents formation of blood clots. Aspirin therapy may improve time to healing and decrease the number of recurrent VLU episodes. If proved effective, the low cost of aspirin therapy as an adjunct to compression would make it an affordable preventive agent for people with VLUs in all countries.

Review question

What are the benefits and harms of oral aspirin on the healing and recurrence of venous leg ulcers.

What we found

We identified only two randomised controlled trials that compared oral aspirin (300mg daily) plus compression with compression and placebo, or compression alone. One study conducted in UK included 20 participants (ten in the aspirin group and ten in the control group) and followed people for four months. This trial reported that the ulcer area had reduced (by 6.5 cm², a 39.4% reduction) in the aspirin group compared with no reduction in ulcer area in the control group, and that a higher proportion of the ulcers (38%) in the aspirin group had completely healed compared with none in the control group. Recurrence was not investigated in this study. Another study conducted in Spain included 51 participants (23 in the aspirin group and 28 in the control group) and followed people until their ulcers had healed. The study reported that the average time for healing was 12 weeks in the aspirin group and 22 weeks in the control group, and that there was no real difference between the proportion of people with ulcers healed (17 (74%) out 23 people in the aspirin group and 21 (75%) out 28 people in the control group). The average time for recurrence was longer in the aspirin group (39 days) compared with (16.3 days) in group of compression alone. Adverse events were not reported in either trial.

We considered these two studies too small and low quality for us to draw definitive conclusions about the benefits and harms of oral aspirin on the healing and recurrence of venous leg ulcers. The UK study provides only limited data about the potential benefits of daily oral aspirin therapy with compression due to a small sample size of only 20 participants and short follow up. The Spanish study provides limited data on 51 participants comparing aspirin and compression to a control group. The fact that no information was reported regarding placebo in the control group means the estimate of effect is uncertain. Further high quality studies are needed in this area.

This plain language summary is up to date as of 27 May 2015.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Oral aspirin for venous leg ulcers.

| Oral aspirin for venous leg ulcers | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with venous leg ulcers Settings: hospital outpatients in UK and Spain Intervention: oral aspirin | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Oral aspirin | |||||

| Average time for ulcer healing | 22 weeks | 12 weeks | Not estimable | 51 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | P values and confidence intervals were not reported |

| Reduction of ulcer area (median) | 0 cm² | 6.5cm² | Not estimable | 20 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | P value < 0.002 Follow‐up: 4 months |

| Proportion of healed ulcers in the trial period | No healed ulcers | 38% of healed ulcers | Not estimable | 20 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | P value < 0.007 Follow‐up: 4 months |

| Major bleeding | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 20 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low2,3 | No events were observed in either group, follow‐up: 4 months Another study reported 2 hospitalisations for unknown reasons, intervention group not specified |

| Average time of ulcer recurrence |

16.33 days SD: 7.5 |

39 days SD: 6.0 |

Not estimable | 51 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | P value = 0.007 Post hoc assessment not pre‐specified in protocol |

| Mortality | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | See comment | See comment | Mortality not reported |

| Other adverse events | See comment | See comment | Not estimable | 71 (2 study) | See comment | No events were observed in either group. del Río Solá reported 2 hospitalisations for unknown reasons, the group of these patients were not specified and they were removed from the study |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (for example, the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio; SD: standard deviation | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate | ||||||

1 Allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessment were not described. Participants and personnel were not blinded. There was a high risk of bias from incomplete outcome data.There were some inconsistencies in the reporting of the data 2 The study results are based on one small study with insufficient data to estimate the effect precisely 3 Selection, performance and reporting biases were unclear

Background

Description of the condition

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs; also known as varicose ulcers or stasis ulcers) occur as results of the chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), which is a functional disorder of the venous system of the leg. The venous leg system is a compound of superficial, deep and perforating veins (perforating veins connect the superficial and deep veins). Damage in any of these veins causes an impairment of venous return, this impairment causes increased venous pressure also known as venous hypertension Ballard 2000). Chronic venous hypertension (CVH) leads to an inflammatory response by leukocytes (white blood cells involved in the inflammation process) that causes cellular and tissue dysfunction which in turn results in varicose veins (veins unnaturally and permanently distended) and dermal changes called lipodermatosclerois characterised by the presence of oedema, hyperpigmentation, induration and eczema of the skin. Ulceration is the final stage of these alterations. (Appendix 1; Thomas 1988; De Araujo 2003; Barron 2007; Rafetto 2009).

Clinically, a VLU is characterised by erosion of the skin usually in the gaiter area of the lower leg (between the knee and the ankle; Dorland 2007). Ulcers vary in size and number. Usually, they have a shallow base, flat margin with the surrounding skin showing features of CVH (Gilliland 1991; Valencia 2001; Raju 2009). Pain that impairs quality of life is present in 75% of people with this condition (Friedman 1990; Philips 1994); in some cases the ulcer has an associated odour that can result in social isolation and depression (Gilliland 1991;Jones 2008).

Venous leg ulceration has a tendency to become chronic and recurrent; one estimate suggests that 30% of healed ulcers recur in the first year, rising to 78% after two years (Mayer 1994). Around 80% of lower extremity leg ulcers presenting in general practice are VLUs; the remaining 20% are as a result of arterial insufficiency, neuropathy, trauma, inflammatory or metabolic conditions, malignancy and infections (Falabella 1998; Sibbald 1998; Valencia 2001; Moloney 2004; Dealey 2005). Diagnosis of a VLU is based on a clinical assessment and the presence of symptoms that are consistent with venous hypertension (i.e. an ulcer located in the medial gaiter area; presence of varicose veins, eczema, pigmentation, induration and oedema, in any combination). In a few cases the diagnosis can be complemented by non‐invasive methods such as ultrasonography.

VLUs are a major health problem because of their frequent occurrence and associated high cost of care. The disease mainly affects people between 60 and 80 years of age, women are affected three times more frequently than men. The rate of occurrence of VLUs is likely to increase as the average age of the population increases (Callam 1987; Margolis 2002). Estimates of its occurrence rate vary by country. For example, in Europe, including countries such as Denmark, Czechoslovakia and Switzerland, the rates of occurrence have been reported at 1% to 5.5% in women and 0.9% to 1.9% in men (Bobek 1966; Arnoldi 1968; Kamber 1978); in the USA the rates were reported as 0.2% in women and 0.1% in men (Coon 1973); and in Brazil as approximately 1.5% for open or healed VLU (Maffei 1986). The cost of treating VLUs is estimated to be one billion USD per year in the USA, and the average cost for one person over a lifetime has been estimated to exceed USD 40,000 (Valencia 2001). Another study of people with VLUs estimated that the average duration of follow‐up was 119 days and the average total medical cost per person was USD 9685 (Olin 1999).

Description of the intervention

The goals of treatment for people with venous leg ulcers include: reduction of oedema, relief of pain and lipodermatosclerosis, ulcer healing, and prevention of recurrence (De Araujo 2003). Different modalities of treatment are used for treating VLUs and these are sometimes used in combination (Blankensteijn 2009). The most common form of treatment is compression therapy (covering the leg with a firm bandage or socks, to apply an external force which aids the flow of blood in the veins). Whilst compression has the potential to heal approximately 50% of VLUs (Weller 2012), rest with elevation of the affected leg, venous surgery, and oral medication with drugs (such as pentoxifylline that aim to improve blood flow and reduce clotting (Jull 2007)) are also used to treat this condition. A treatment that can suppress inflammation would be useful. Oral aspirin is a widely used drug that may have the potential to exert a beneficial influence in the treatment of VLUs. However, until now, no comprehensive summary of the available evidence has been conducted.

How the intervention might work

Classical signs of inflammation have been observed in biopsies and plasma samples in experimental models of venous disease. The cascade starts with increased vascular permeability (increased leakage of plasma and cells through the vein wall) and progression to adhesion of leukocytes (white blood cell involved in the inflammation process) and platelets (very small structures shaped like a discus, present in the blood with important role in the coagulation) to endothelium (the cells lining the lumen of the veins). Over time the disease progresses to vascular restructuring of venous varicosities (veins which are unnaturally and permanently distended). Unlike acute wound healing, chronic VLUs remain at an prolonged inflammatory stage with formation of granulation tissue (newly formed tissue which repairs damaged areas) (Bergan 2007).

Aspirin or acetylsalicylic acid was introduced as a medication in 1899 by Dreser (Burke 2006). Aspirin has analgesic, anti‐inflammatory and antipyretic (fever‐reducing) properties (Winter 1966). It inhibits platelet aggregation, and acts as an inhibitor of cyclooxygenase (substance involved in the synthesis prostaglandins), resulting in the inhibition of the biosynthesis (physiologic production of a substance into the body) of prostaglandins (substances involved in the inflammatory process causing venous dilatation and inhibition the platelet aggregation) (Salzman 1971; Vane 1971). Prostaglandins are released during the inflammatory phase, and are thought to increase blood vessel permeability, manifested by venous oedema and capillary leakage. Aspirin stimulates the biosynthesis of other anti‐inflammatory compounds by inhibiting the cyclooxygenase pathway. The precise mechanism by which aspirin is thought to mediate effects on VLU healing is unclear, although inhibition of platelet activation and reduction of inflammation and pain have been suggested (Ibbotson 1995; De Araujo 2003). However, aspirin is known to have adverse effects, most commonly gastric ulceration and other gastrointestinal effects, as well as hepatotoxicity (liver damage), exacerbation of asthma, skin rashes and renal toxicity (Cappelleri 1995; Burke 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Chronic VLU healing remains a complex clinical problem and requires the intervention of skilled, but costly, multidisciplinary wound care teams. Recurrence is often an ongoing issue for people who experience venous ulcers. Aspirin is an inexpensive and widely available treatment currently used in several other clinical situations. Oral aspirin is potentially one of the most effective preventive agents for use in people with VLUs. It has the potential to improve healing rates, shorten time to healing and decrease the number of recurrent episodes after healing. If proved effective, the low cost of aspirin therapy as an adjunct to compression would make it an affordable preventive agent for people with VLUs in all countries. Despite its potential benefits, there are limited data available about the effectiveness of aspirin in people with VLUs. Additionally, with the number of people with VLUs expected to rise significantly in the coming decades, development of new safe ways of healing and reducing recurrence are high priorities in health research.

Objectives

To assess the benefits and harms of oral aspirin on the healing and recurrence of venous leg ulcers.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of oral aspirin to treat people with venous leg ulcers.

Types of participants

Adults (as defined in trials) undergoing treatment for venous leg ulceration or prevention of recurrence of venous leg ulcers.

Types of interventions

Oral aspirin compared with placebo or any other therapy in the presence or absence of compression therapy.

To be eligible for inclusion, treatment with oral aspirin must be the only systematic difference between treatment arms, therefore a study in which one group received compression and one did not would not be eligible for inclusion unless within a factorial design.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Time to complete ulcer healing.

Rate of changes in the area of the ulcer in the trial period.

Proportion of ulcers healed in the trial period.

Proportions of people with ulcers completely healed in the trial period.

Major bleeding (haemorrhagic stroke, gastric bleeding, any bleeding requiring blood transfusion, any bleeding causing hospitalisation).

Secondary outcomes

Pain relief (as measured by a valid pain scale).

Mortality from any cause.

Any adverse events (e.g. renal failure, neutropenia, low platelets level, gastric complaints, diarrhoea, skin rash, minor bleeding).

Ulcer recurrence (time to recurrence and proportion of people with recurrence).

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following electronic databases to identify reports of randomised controlled trials:

The Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register (searched 27 May 2015);

The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2015, Issue 4);

Ovid MEDLINE (1946 to 26 May 2015);

Ovid MEDLINE (In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations) (searched 26 May 2015);

Ovid EMBASE (1974 to 26 May 2015);

EBSCO CINAHL (1982 to 27 May 2015).

The search strategies we used can be found in Appendix 2. The Ovid MEDLINE searches were combined with the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximizing version (2008 revision) (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the EMBASE search with the Ovid EMBASE trial filter terms developed by the UK Cochrane Centre (Lefebvre 2011). We combined the CINAHL search with the trial filter developed by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN 2011). There was no restriction on the basis of date, or language of publication.

We also searched the following clinical trials registries:

ClinicalTrials.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/); WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) (http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/default.aspx).

Searching other resources

We searched the references of all identified studies in order to find any further relevant trials. We also contacted experts in the field.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two reviews authors (NGM and RFA) selected studies as described in Chapter 7 of theCochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions as follows (Higgins 2011a):

We merged search results using reference management software, and removed duplicate records of the same report.

We examined titles and abstracts to remove obviously irrelevant reports.

We retrieved full text of the potentially relevant reports.

We linked multiple reports of the same study.

We examined full‐text reports for compliance of studies with eligibility criteria.

We clarified study eligibility (where appropriate) by corresponding with investigators.

We made final decisions on study inclusion to allow data collection to proceed.

Any disagreements were solved by discussion. If this did not result in agreement, the opinion of the third review author (PEdOC) was decisive. We documented the reasons for exclusion of any article.

Data extraction and management

Two reviews authors (NGM and RFA) independently extracted details of eligible studies and summarised them using a data extraction sheet specific to this review that was constructed according Chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011a). The data extracted included the baseline characteristics of the intervention and control group participants, and included (where available): participant numbers, age, gender, ethnicity, the main outcome measures, length of follow‐up, and numbers of drop‐outs (Table 2).

1. Data extracted from included studies.

| Study identification | Layton | del Río Solá | ||||

| Country | United Kingdom | Spain | ||||

| Period | Not reported | 2001 to 2005 | ||||

| Centres | Academic Unit of Dermatology, General Infirmary at Leeds, West Yorkshire | University Hospital of Valladolid | ||||

| Source of funding | Not specified | Not specified | ||||

| Method | ||||||

| Study design | Prospective randomized, double‐blind | Prospective randomized trial | ||||

| Power calculation | Not described | Yes | ||||

| Method of randomisation | Not described | Generated by computer program | ||||

| Concealment of allocation | Not described | Not described | ||||

| Number of participants randomized | 20 | 51 | ||||

| Number of participants analyzed | 20 | 47 | ||||

| Number of participants excluded after randomizations | 0 | 0 | ||||

| Number of participant withdrawals and reasons | 0 | 4 people; 2 people needed hospitalisation and left the study and 2 people opted for treatment in another service | ||||

| Intention‐to‐treat analysis | Yes | Yes | ||||

| Participants | ||||||

| Inclusion criteria | People with chronic venous leg ulcer | Venous leg ulcer ≥ 2 cm Ankle‐brachial rate < 0.9 No contraindication to taking aspirin |

||||

| Exclusion criteria | Ulcer diameter < 2 cm Already taking aspirin, anticoagulants or non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory Doppler flowmetry ankle‐brachial rate < 0.9 |

People with diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral arterial disease and neurologic disease Previous or concomitant therapy with aspirin |

||||

| Aspirin | Control | P value | Aspirin | Control | P value | |

| Number of participants | 10 | 10 | 23 | 28 | ||

| Age (years) | 62.2 years (mean) (48‐81) |

66 years (mean) (46 ‐ 85) |

60.50 years (SD:12.07) | 58.59 years (SD:16.55) | reported as non significant | |

| Sex | 3 female, 7 male | 5 female, 5 male | 10 female, 13 male | 19 female, 9 male | reported as non significant | |

| Ulcer duration before the study | 11.4 years (mean) (1‐24) |

10.5 years (mean) (2‐22) |

6‐12 months | > 12 months | ||

| 1 Number of ulcers | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | reported as non significant | |

| Initial ulcer surface area (cm²) | 16.5 cm² (mean) (2.5‐39.5) |

14.25 cm² (mean) (1.5‐48.5) |

25.15 cm² | 24.87 cm² | P=0.944 | |

| Signs of ulcer infection | Not reported | Not reported | Yes, 20 patients | Yes, 22 patients | P=0.094 | |

| Any comorbidity | Not reported | Not reported | 9 patients | 10 patients | ||

| Previously treated | \not reported | Not reported | 10 patients | 20 patients | ||

| Interventions | Aspirin 300 mg/day | Placebo | Aspirin 300 mg/day | No drug treatment | ||

| Outcomes | ||||||

| Follow‐up (months) | 4 months | 4 months | 42 months mean (24‐61) | 42 months mean (24‐61) | ||

| 2 Withdrawals | 0 | 0 | 2 people | 2 people | ||

| Duration of the study to complete ulcer healing | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 12.4 weeks | 16.5 weeks | P=0.07 Mann‐Whitney |

| Healing period | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | Reported as short in the aspirin group | Reported as short in the aspirin group | P=0.04 log‐rank test = 3.90 OR = 0.93 95% CI 0.25‐3.5 |

| Average time to complete ulcer healing (weeks) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 12 | 22 | Not reported |

| Number of participants with complete ulcer healing in the trial period | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 17 (74%) | 21 (75%) | reported as non significant |

| Proportion of ulcers healed in the trial period | 38% of the ulcers | 0% of the ulcers | < 0.007 (x² test) |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Change in ulcer areas in the trial period (second month; ulcer area cm²) | 15.5 cm² (median) 1 cm² of reduction (6.07% of reduction) |

No reduction | < 0.01 (x² test) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Reduction in ulcer size in the trial period (fourth month; ulcer area cm²) | 10.0 cm² (median) 6.5 cm² of reduction (39.4% of reduction) |

No reduction | < 0.002 (x² test) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Improvement assessed by reduction in ulcer size | 52% of the ulcers | 26% of the ulcers | < 0.007 (x² test) |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Increase in ulcer size in the trial period | 10% of the ulcers | 26% of the ulcers | < 0.004 (x² test) |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Ulcers size unchanged in the trial period | 0% of the ulcers | 48% of the ulcers | < 0.001 (x2 test) |

Not reported | Not reported | Not reported |

| Proportion of participants with ulcers healed in the trial period | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 17 (74%) | 21 (75%) | reported as non significant |

| Proportion of participants with ulcer recurrence | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 25% | 33.33% | 0.74 |

| Average time for ulcer recurrence (days) | Not reported | Not reported | Not reported | 39 (SD 6) | 16.33 (SD 7.5) | P=0.007 Kaplan‐Meier |

| adverse effects | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Not reported | |

- Layton reported 12 people (60%) and del Rio 28 people (54%) with multiples ulcers but they did not specified the number in each group

- del Rio Solá reported that two people were hospitalised and were withdrawn from the study, but did not specify the cause of hospitalisation or their trial group

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We used the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias to present a summary of the risk of bias for each included study . This tool addresses seven specific domains Higgins 2011b:

Was the allocation sequence adequately generated?

Was the allocation adequately concealed?

Was the blinding of participants and personnel adequately provided?

Was the blinding of outcome assessors adequately provided?

Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed?

Were reports of the study free of suggestion of selective outcome reporting?

Was the study apparently free of other problems that could put it at a high risk of bias?

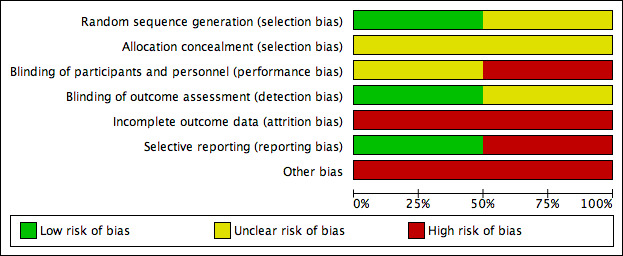

Two authors (NGM and RFA) assessed each study independently; disagreements were solved by consultation with the third review author (PEdOC). Additionally, we presented a 'Risk of bias' summary figure, reporting all our judgements in a cross‐tabulation of study by entry (Figure 1). This display of internal validity shows the weight given to the results of the particular studies.

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

For binary outcomes (e.g. recurrence, improvement), we planned to present risk ratios (RR); risk differences (RD), the number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB), and the number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH), all with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

For continuous data (e.g. ulcer area), we planned to present differences as mean differences (MD) with corresponding 95% CIs, or standardised mean differences (SMD) when the studies assessed the same outcome but measured it in a variety of ways (e.g. different questionnaires for pain assessment).

For time to complete ulcer healing, that is time‐to‐event data, we planned to use the most appropriate way of summarising this type of data using survival analysis methods and to express the intervention effect as a hazard ratio (HR).

Unit of analysis issues

We only considered simple parallel‐group designs for clinical trials (Deeks 2011). If healing outcomes were reported at several time points, we planned to perform the analysis using the time‐points reported (for example, 30 or 60 days or the time for ulcer healing). We planned to consider the number of ulcers per patient and the ulcer area per patient, which means, for patients with more than one ulcer, calculating the total area of the ulcers.

Dealing with missing data

We contacted the trial authors to obtain relevant missing data and investigated attrition rates (for example, drop‐outs, losses to follow‐up and withdrawals). Authors did not respond to our requests. We address the potential impact of missing data on the findings of the review in the discussion section (Higgins 2011c).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We planned to assess statistical heterogeneity using the I² statistic to examine the percentage of total variation across studies due to heterogeneity rather than to chance (Higgins 2003). Values of I² under 40% indicate a low level of heterogeneity and justify the use of a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis. Values of I² between 30% and 60% are considered to indicate moderate heterogeneity and a random‐effects model would have been used. Values of I² higher than 60% indicate a high level of heterogeneity; in which case meta‐analysis would not be appropriate. We planned to report whether statistical, methodological and clinical heterogeneity were present (Deeks 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

If a sufficient number of studies had been eligible for inclusion (more than 10), we planned to use funnel plots to assess for the potential existence of small study bias. There are a number of explanations for the asymmetry of a funnel plot and we planned to interpret the results (Egger 1997).

Data synthesis

In the absence of heterogeneity, we planned to use a fixed‐effect model for meta‐analysis. If statistical heterogeneity was moderate (I² between 30% and 60%), we planned to use a random‐effects model. In the presence of substantial statistical heterogeneity between studies, we planned to present a narrative summary (O'Rourke 1989).

'Summary of findings' tables

We planned to present the main results of the review in 'Summary of findings' tables. These tables present key information concerning the quality of the evidence, the magnitude of the effects of the interventions examined and the sum of available data for the main outcomes (Schunemann 2011a). The 'Summary of findings' tables also include an overall grading of the evidence related to each of the main outcomes using the GRADE (Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach. The GRADE approach defines the quality of a body of evidence as the extent to which one can be confident that an estimate of effect or association is close to the true quantity of specific interest. The quality of a body of evidence involves consideration of within trial risk of bias (methodological quality), directness of evidence, heterogeneity, precision of effect estimates and risk of publication bias (Schunemann 2011b). We planned to present the following outcomes in the 'Summary of findings' tables.

Time to complete ulcer healing.

Rate of changes in the area of the ulcer in the trial period.

Proportion of ulcers healed in the trial period.

Major bleeding (haemorrhagic stroke, gastric bleeding, any bleeding requiring blood transfusion, any bleeding causing hospitalisation).

Mortality from any cause.

Any adverse events (e.g. renal failure, neutropenia, low platelets level, gastric complaints, diarrhoea, skin rash, minor bleeding).

Ulcer recurrence (time to recurrence and proportion of people with recurrence).

Sensitivity analysis

We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to explore the influence of the following factors on the effect of aspirin:

repeating the analysis excluding unpublished studies;

repeating the analysis taking into account risk of bias: we planned to exclude those studies at high risk of bias (i.e. those lacking adequate sequence generation, unclear allocation concealment and no blinding of outcome assessment).

We also planned to test the robustness of the results by repeating the analysis using different measures of effect size (risk ratio, odds ratio, etc.) and different statistical models (fixed‐effect and random‐effects models; (Deeks 2011).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

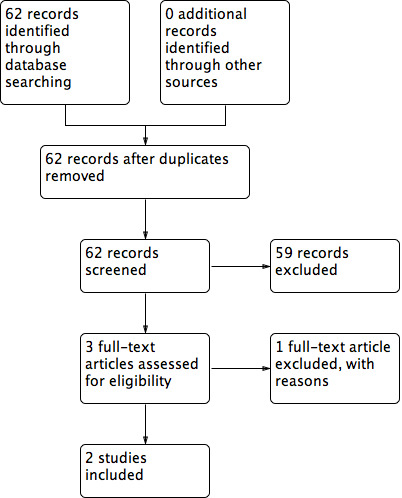

The electronic search identified 62 studies; no studies were found through additional searching strategies (such as contact with experts and checking the references of studies). After the analysis of title and abstracts, we excluded 59 studies as they did not meet the inclusion criteria.Three RCTs were selected for full‐text analysis: Layton 1994; Ibbotson 1995 and del Río Solá 2012. After the full‐text analysis, two RCTs were included in the review (Layton 1994; del Río Solá 2012). Ibbotson 1995 used the same people and data as the Layton RCT but compared them with a control group of healthy people, so we excluded this trial (Figure 2).

2.

Flow diagram of included and excluded studies

Included studies

Details of the included studies are summarised in Characteristics of included studiesTable 2.

Layton 1994 reported a single‐centre parallel RCT (20 participants) that evaluated daily administration of oral aspirin (300 mg) in addition to compression, compared to placebo and compression. Participants were recruited from the Academic Unit of Dermatology, General Infirmary at Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK. del Río Solá 2012 reported a single‐centre parallel RCT (51 participants) that evaluated daily administration of oral aspirin (300 mg) in addition to compression compared to compression only and recruited from the Department of Angiology and Vascular Surgery, University Hospital of Valladolid, Spain, from December 2001 to September 2005.

Layton 1994 was a prospective trial that included 20 people with venous leg ulcers 2 cm or larger, divided into two parallel groups: 10 participants received oral aspirin (300 mg/day) plus compression therapy compared with 10 who received placebo plus compression therapy.

The del Río Solá 2012 study was a prospective trial that included 51 people with venous leg ulcers 2 cm or larger, divided into two parallel groups: 23 participants received oral aspirin (300 mg/day) plus compression therapy compared with 28 who received compression therapy alone.

The source of funding was not reported for either trial.

Both RCTs used the same intervention (oral aspirin 300 mg/day). The Layton 1994 study randomized participants to a placebo as an adjunct to compression therapy in the control group, while the del Río Solá 2012 study randomized those in the control group to compression therapy alone (no placebo). Compression therapy consisted of high compression (Setopress) in the Layton 1994 RCT. The del Río Solá 2012 RCT did not specify what type of compression was used, although the trialists reported the application of a two‐layer system consisting of one layer of padding and one layer of compression bandage.

The Layton 1994 trial followed participants for four months and then stopped the trial. The results were expressed in terms of reduction of the ulcers' size (surface area cm²) and proportions of ulcers completely healed in the trial period.

The del Río Solá 2012 trial followed participants until their ulcers had healed completely. The results were expressed in terms of proportion of healed ulcers in each group and average time for ulcer healing. . After healing, they continued to follow participants to analyse the proportion of ulcer recurrence and time until ulcer recurrence.

Excluded studies

We excluded the Ibbotson 1995 trial. This trial used the same participants reported in Layton 1994 and compared them with a control group of healthy people without venous leg ulcers. The objective was to evaluate some haemostatic parameters in people with venous leg ulcers taking oral aspirin (see Characteristics of excluded studies).

Ongoing studies

We identified three ongoing studies which evaluate the benefits and harms of aspirin in people with VLUs. (Characteristics of ongoing studies).

Low dose aspirin for venous leg ulcers in NZ (Aspirin4VLU) (NCT02158806) is a prospective, randomised, double blinded, 2 groups in parallel study that will evaluate whether aspirin (150 mg) once daily for up to 24 weeks improves time to healing when compared to placebo once daily for up to 24 weeks as an adjunct to compression. NCT02333123 is leading a phase II randomised, double blind, parallel group, placebo‐controlled efficacy trial taking place in the UK. The Aspirin for Venous Ulcer Randomised Trial (AVURT) will evaluate if aspirin 300 mg once daily for up to 27 weeks added to compression improves time to healing when compared to placebo once daily for up to 27 weeks. ACTRN12614000293662 is investigating the clinical effectiveness of aspirin as an adjunct to compression therapy in healing chronic venous leg ulcers: a randomised double‐blinded placebo‐controlled trial in Australia. The ASPiVLU study will compare if a daily dose of 300 mg enteric coated aspirin as an adjunct to compression for 24 weeks improves time to healing when compared to a placebo. Recruitment has commenced for all three trials.

Risk of bias in included studies

Allocation

The Layton 1994 trial was described as 'randomized' but did not report the method of randomizations or the concealment of allocation. In del Río Solá 2012, randomization was undertaken by an independent researcher using a computer program, but allocation concealment was not described.

Blinding

The Layton 1994 trial compared oral aspirin with placebo, and the trial was described as 'double‐blinded', but the trialists did not describe their methods. The evaluation of ulcer size was conducted by planimetry of photographs taken in standardized conditions, so we judged this as low risk of bias.

The del Río Solá 2012 trial did not use a placebo but compared intervention (aspirin) with no intervention. In this scenario, blinding of participants and personnel was not possible. The study reported information about ulcer development (size, epithelization) weekly in a specific data sheet, but they did not describe who did what and how this work was done, so we judged this study as high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

The Layton 1994 trial did not have any withdrawals. The del Río Solá 2012 trial reported four withdrawals, two from each group. Two of these four participants were withdrawn because they needed to be in hospital, but the cause and group assignments were not reported.

Selective reporting

As there were several inconsistencies in the del Río Solá 2012 report, we assigned the study a low risk of reporting bias. Time for complete ulcer healing in the control group, which was stated as 22 weeks in the text but as 16.5 weeks in the table (Table I of the study); errors with the numbers of people in each group, which were reported as 23 for the aspirin group and 28 for the control group in the main text, but appeared as 20 and 31 in the table; and the proportion of people completely healed was reported as 0.73% rather than 75% (21 out of 28 people) for the control group and 0.75% rather than 74% (17 out of 23 people) for the treatment group.

As the results of both prespecified primary outcomes were reported in Layton 1994, we judged it to be free of selective reporting.

Other potential sources of bias

The Layton 1994 trial was stopped in the fourth month. In that time, 38% of ulcers had healed in the aspirin group, but no ulcers had healed in the placebo group. However, the time period could be considered too short, as the assumption that all ulcers could heal in this period may lead to misinterpretation (i.e. some ulcers may have healed in the control group given more time).

In the del Río Solá 2012 trial, despite an appropriate method of randomizations (an independent researcher and computer program), the generated groups were different in relation to the length of time that people had ulcers before treatment. 'Young' ulcers predominated in the aspirin group, and may have had a tendency to heal faster than chronic or 'older' ulcers. Also, the trial authors did not determine a specific trial period. To calculate the size of the study, they used an expected difference of 45% between groups, but did not specify whether the difference was in the proportion of people with healed ulcers, the area of the ulcers or the time for healing.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Both included RCTs analysed the ulcer healing time, but reported it using different outcome measures. The interventions that were studied in the two trials that reported relevant outcomes for this review were too heterogenous to allow pooling of outcomes data. We therefore reported the trial results for each trial separately.

Primary outcomes

Time to complete ulcer healing

The del Río Solá 2012 trial followed the people until the healing of their ulcers and reported the average time for healing was 12 weeks in the aspirin group and 22 weeks in the control group, P values and confidence intervals were not reported Table 2.

Rate of changes in the area of the ulcer in the trial period

The Layton 1994 stopped the trial in the fourth month and reported this outcome: by four months, ulcer area had reduced (by 6.5 cm², a 39.4% reduction) in the aspirin group compared with no reduction in ulcer area in the control group (P value < 0.002; Table 1).

Proportion of ulcers healed in the trial period

The Layton 1994 trial reported this outcome: a higher proportion of the ulcers (38%) in the aspirin group had completely healed in the trial period compared with none in the control group (P value < 0.007; Table 1).

Proportion of people with ulcers healed in the trial period

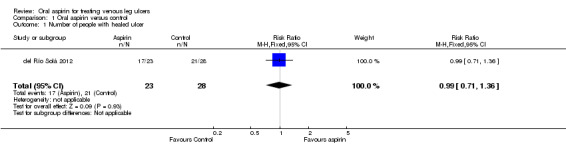

The del Río Solá 2012 trial reported that there was no real difference between the proportion of people with ulcers healed in the aspirin group (74%, 17 out of 23 people) and in the control group (75%, 21 out of 28 people; Table 2), (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.36; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral aspirin versus control, Outcome 1 Number of people with healed ulcer.

Major bleeding (haemorrhagic stroke, gastric bleeding, any bleeding requiring blood transfusion, any bleeding causing hospitalisation)

The del Río Solá 2012 trial reported two hospitalisations, in addition to two other withdrawals, but did not specify the cause or the group assignment of the participants who withdrew (Table 2).

The Layton 1994 trial reported that no side effects were experienced (Table 2).

Secondary outcomes

Pain relief

Neither study reported pain relief.

Mortality

The Layton 1994 trial reported that no side effects were experienced.

The del Río Solá 2012 trial reported that two people needed hospitalisation and had to be withdrawn from the trial (in addition to two other withdrawals), but they didn't report the reason for hospitalisation or their group assignment. The authors did not report other adverse events.

Adverse events

The Layton 1994 trial reported that participants had no adverse effects, but did not explain how this was established. The del Río Solá 2012 trial did not report adverse events.

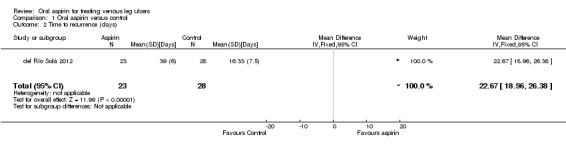

Ulcer recurrence

The del Río Solá 2012 trial reported the average time of ulcer recurrence was 16.33 days (SD: 7.5) in the control group and 39 days (SD: 6.0) in the aspirin group (P = 0.007).

Layton 1994 did not report recurrence.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Aspirin has been used as medication since 1899 and its pharmacodynamic properties as an anti‐inflammatory, analgesic, antipyretic, and inhibitor of both platelet aggregation and biosynthesis of prostaglandins, have been well studied. VLUs are associated with venous stasis, inflammation and necrosis; so some of the properties of aspirin may be useful for patients with VLUs. We searched extensively in seven different databases, using an appropriate search strategy for each one, to identify studies that had analysed the effect of aspirin on healing of VLUs. This review intended to summarize the effect of oral aspirin in treatment of VLUs; our searches identified no previous reviews and only two clinical trials that could be included, del Río Solá 2012 with 51 participants, and Layton 1994 with 20 participants. Both studies used the same intervention (oral aspirin 300 mg/day) and had the objective of evaluating the effects of oral aspirin on the healing of VLUs, however they used different outcome measurements. The Layton 1994 trial compared the average reduction in ulcer area in the second and fourth months, while the del Río Solá 2012 trial compared the average time for complete healing of the ulcer. The conclusions of both studies favoured the aspirin group: Layton 1994 showed a significant reduction in ulcer area in the fourth month of treatment and del Río Solá 2012 showed a significant reduction in the time required for complete healing of ulcers. However the two studies included very few participants, a total of 71, and the differences in the outcomes measurements prevented meta‐analysis. The evidence was downgraded to low quality due to the potential for selection bias and imprecision in the results, thus there is uncertainty around the effect estimates.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

There was scant evidence available to assess the benefits of 300,mg aspirin to heal people with venous leg ulcers.The small number, small size and differing outcome measurements of the two included trials meant that there was insufficient evidence for us to draw meaningful conclusions about the use of oral aspirin in the treatment of VLUs.

The benefits and harms of aspirin varies with its plasmatic level. Aspirin blood concentration from 50 to 300 mcg/ml are sufficient for most of its therapeutic effects and doses greater than 200 mcg/ml increase the risks for adverse events. Nowadays aspirin is used to treat many vascular conditions such as, ischemic stroke, angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, revascularization procedures, etc, with doses that vary from 50 to 325 mg/day. Both studies included in this review used 300 mg aspirin daily, however, the ideal dose for each clinical condition remains in debate (Cappelleri 1995; Dalen 2006).

Layton 1994, did not report any characteristics of the population included in his study; del Río Solá 2012 included 51 patients, 29 women and 22 men with mean age of 60 years ranging from 36‐86 years old. The study excluded patients with co morbidities such as diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral arterial disease and neurologic disease. The characteristics of this population is in concordance with the populations described in the epidemiologic studies of chronic venous insufficiency (Beebe‐Dimmer 2005).

Quality of the evidence

Only low quality evidence was available from two trials and both the RCTs that were eligible for inclusion in the review had an unclear or high risk of bias for most domains (allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, incomplete outcome data and other biases). Due to the lack of reliable evidence, we are unable to draw conclusions about the benefits and harms of oral daily aspirin as an adjunct to compression in VLU healing or recurrence. We graded the overall quality of the evidence as low, indicating that future research is likely to have an important influence on the effect estimates.

Potential biases in the review process

We are confident that the broad literature search used in this review has captured most of the relevant literature, and minimised the likelihood that we have missed any relevant trials. Two review authors independently selected trials, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias, in order to minimise bias. Due to the differences in reporting of outcome measures between the trials, we could not conduct the planned meta‐analysis.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

This is the first review of randomised studies that address this question, as far as we are aware. The treatment of VLUs can be frustrating for physicians and people with ulcers because these kinds of ulcers have a tendency to recur and become chronic. Some therapies are already well established, such as compression and rest with elevated legs (O'Meara 2012). On the basis of recent research that showed the importance of inflammation in the development of ulcers, new therapies using anti‐inflammatory drugs have been evaluated, including pentoxifylline (Jull 2007), prostaglandins (Rudofsky 1989), and prostacyclin analogues (Werner‐Schlenzka 1994). These studies often describe benefits, but like the studies included in this review, they have only included small numbers of participants.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Two small studies showed that aspirin may improve the healing of venous leg ulcers (VLUs). Given that these studies were at moderate (to high) risk of bias and did not report on other important adverse events, such as bleeding, it may be prudent to limit the use of aspirin to aid healing in this population until evidence of benefit, and of no harm, is available. The conclusions we can draw in our systematic review are limited by the quality and number of trials that met our inclusion criteria, and lack of reporting of important outcomes. The trials we identified were susceptible to bias, and hampered by inadequate reporting and small sample sizes, which may have hidden real benefits.

Implications for research.

Although the role of inflammation in the development of VLUs is well documented, this review has shown that there is very little research on the benefits and harms of aspirin in their treatment. Consequently, we still have insufficient high‐quality evidence to make definitive conclusions about the effectiveness and safety of aspirin for people with this condition. Further high quality research is required before definitive conclusions can be made about the benefits of aspirin as an adjunct to compression in people with VLUs. Future trials should clearly report baseline participant characteristics and conform to the CONSORT 2010 recommendations with sufficient power to detect a true treatment effect.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank:

Peer referees: Susan O' Meara, Liz McInnes, Duncan Chambers, Gill Worthy, Mike Clark, Una Adderley and Jane Nadel, for their valuable and constructive feedback.

FAPESP (Fundaçao de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo) for the support granted.

Copy editors, Jenny Bellorini and Elizabeth Royle.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary for terms described in the background

Analgesic: substance that provides pain relief. Anticoagulant: prevents blood clot formation. Antipyretic: reduces fever. Chronic venous insufficiency: very poor blood flow or circulation in veins. Hyperpigmentation: abnormally increased skin colour/pigmentation, such as of the skin or a mucous membrane. Lipodermatosclerosis: area of hyperpigmentation and induration of the skin in the lower legs caused by inflammation and leakage of red blood cells into the skin and subcutaneous fat. Seen in people with chronic venous insufficiency. Oedema: swelling; an abnormal accumulation of fluid beneath the skin, or in one or more of the cavities of the body. Venous hypertension: high blood pressure in veins

Appendix 2. Search strategies

The Cochrane Wounds Specialised Register

(aspirin or "2‐acetyloxy benzoic acid" or acylpyrin or aloxiprinum or colfarit or disopril or aspirin or ecotrin or endosprin or magnecyl or micristin or polopirin or polopiryna or solprins or solupsan or zorprin or acetysal) AND (INREGISTER)

The Cochrane Central Register of Randomised Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

#1 MeSH descriptor Leg Ulcer explode all trees #2 (varicose NEXT ulcer*) or (venous NEXT ulcer*) or (leg NEXT ulcer*) or (stasis NEXT ulcer*) or ((lower NEXT extremit*) NEAR/2 ulcer*) or (crural NEXT ulcer*) or ulcus cruris:ti,ab,kw #3 (#1 OR #2) #4 MeSH descriptor Aspirin explode all trees #5 (aspirin or “2‐acetyloxy benzoic acid” or acylpyrin or aloxiprinum or colfarit or disopril or aspirin or ecotrin or endosprin or magnecyl or micristin or polopirin or polopiryna or solprins or solupsan or zorprin or acetysal):ti,ab,kw #6 (#4 OR #5) #7 (#3 AND #6)

Ovid MEDLINE

1 exp Leg Ulcer/ 2 (varicose ulcer* or venous ulcer* or leg ulcer* or stasis ulcer* or crural ulcer* or ulcus cruris or ulcer cruris).tw. 3 or/1‐2 4 exp Aspirin/ 5 (aspirin or 2‐acetyloxy benzoic acid or acylpyrin or aloxiprinum or colfarit or disopril or aspirin or ecotrin or endosprin or magnecyl or micristin or polopirin or polopiryna or solprins or solupsan or zorprin or acetysal).tw. 6 or/4‐5 7 3 and 6 8 randomized controlled trial.pt. 9 controlled clinical trial.pt. 10 randomi?ed.ab. 11 placebo.ab. 12 clinical trials as topic.sh. 13 randomly.ab. 14 trial.ti. 15 or/8‐14 16 exp animals/ not humans.sh. 17 15 not 16 18 7 and 17

OVID EMBASE

1 exp leg ulcer/ 2 (varicose ulcer* or venous ulcer* or leg ulcer* or stasis ulcer* or crural ulcer* or ulcus cruris or ulcer cruris).tw. 3 or/1‐2 4 exp acetylsalicylic acid/ 5 (aspirin or 2‐acetyloxy benzoic acid or acylpyrin or aloxiprinum or colfarit or disopril or ecotrin or endosprin or magnecyl or micristin or polopirin or polopiryna or solprins or solupsan or zorprin or acetysal).tw. 6 or/4‐5 7 3 and 6 8 Randomized controlled trials/ 9 Single‐Blind Method/ 10 Double‐Blind Method/ 11 Crossover Procedure/ 12 (random* or factorial* or crossover* or cross over* or cross‐over* or placebo* or assign* or allocat* or volunteer*).ti,ab. 13 (doubl* adj blind*).ti,ab. 14 (singl* adj blind*).ti,ab. 15 or/8‐14 16 exp animals/ or exp invertebrate/ or animal experiment/ or animal model/ or animal tissue/ or animal cell/ or nonhuman/ 17 human/ or human cell/ 18 and/16‐17 19 16 not 18 20 15 not 19 21 7 and 20

EBSCO CINAHL

S20 S7 and S19 S19 S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12 or S13 or S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 S18 MH "Quantitative Studies" S17 TI placebo* or AB placebo* S16 MH "Placebos" S15 TI random* allocat* or AB random* allocat* S14 MH "Random Assignment" S13 TI randomi?ed control* trial* or AB randomi?ed control* trial* S12 AB ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and AB ( blind* or mask* ) S11 TI ( singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl* ) and TI ( blind* or mask* ) S10 TI clinic* N1 trial* or AB clinic* N1 trial* S9 PT Clinical trial S8 MH "Clinical Trials+" S7 S3 and S6 S6 S4 or S5 S5 TI ( aspirin or 2‐acetyloxy benzoic acid or acylpyrin or aloxiprinum or colfarit or disopril or aspirin or ecotrin or endosprin or magnecyl or micristin or polopirin or polopiryna or solprins or solupsan or zorprin or acetysal ) or AB ( aspirin or 2‐acetyloxy benzoic acid or acylpyrin or aloxiprinum or colfarit or disopril or aspirin or ecotrin or endosprin or magnecyl or micristin or polopirin or polopiryna or solprins or solupsan or zorprin or acetysal ) S4 (MH "Aspirin") S3 S1 or S2 S2 TI (varicose ulcer* or venous ulcer* or leg ulcer* or stasis ulcer* or crural ulcer* or ulcer cruris or ulcus cruris) or AB (varicose ulcer* or venous ulcer* or leg ulcer* or stasis ulcer* or crural ulcer* or ulcer cruris or ulcus cruris) S1 (MH "Leg Ulcer+")

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Oral aspirin versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Number of people with healed ulcer | 1 | 51 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.71, 1.36] |

| 2 Time to recurrence (days) | 1 | 51 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 22.67 [18.96, 26.38] |

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Oral aspirin versus control, Outcome 2 Time to recurrence (days).

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

del Río Solá 2012.

| Methods | Prospective RCT | |

| Participants | 51 people with venous leg ulcers (29 women and 22 men); mean age of 60 years (range from 36‐86) | |

| Interventions | Intervention Group (n = 23): aspirin 300 mg/day Control Group (n = 28): no placebo treatment Compression therapy was used for both groups |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | Excluded patients with diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral arterial disease, neurologic disease, previous or concomitant therapy with aspirin, and ulcers ≤ 2 cm | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Low risk | Performed by an independent researcher using a computer program |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | High risk | The comparison was conducted between intervention and non‐intervention, blinding of participants and personnel was not possible in this case |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | The participants were evaluated weekly using a specific form, but no information was provided about blinding of the personnel who did this work |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | There were 4 withdrawals; 2 people were hospitalised and 2 people opted for treatment in another service. The authors did not describe the cause of the hospitalisations or group assignment of the withdrawn participants |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Low risk | The only primary prespecified outcome reported was the influence of aspirin on the rate of ulcer healing |

| Other bias | High risk | The individual data for each participant were not presented There were some inconsistencies and mistakes in the reported results (the same outcome measures were presented with different values in the text and in the tables) |

Layton 1994.

| Methods | Prospective double‐blind and placebo‐controlled RCT | |

| Participants | 20 people with chronic venous leg ulcers | |

| Interventions | Intervention Group (n = 10): aspirin 300 mg/day Control Group (n = 10): placebo |

|

| Outcomes |

|

|

| Notes | People with ulcers ≤ 2 cm and previous or concomitant therapy with aspirin were excluded | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Not described |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Study was described as double‐blinded but the strategy for blinding the patients and personnel was not described |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | The assessment of ulcer area was conducted using planimetry of photographs of ulcers |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | The individual data from each participant were not presented |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | High risk | Both the primary prespecified outcomes were reported (the influence of aspirin on the reduction of ulcer surface area and percentage of ulcers healed completely in trial period) |

| Other bias | High risk | The prevalence of co morbidities (diabetes, arterial hypertension) that could influence the ulcer healing was not reported |

Abbreviation

RCT: randomized controlled trial

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Ibbotson 1995 | This trial used the same participants and data as the Layton 1994 trial to evaluate some haemostatic parameters in people with venous leg ulcers taking oral aspirin. This group of people with leg ulcers was compared with a control group of healthy people |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

ACTRN12614000293662.

| Trial name or title | Clinical effectiveness of aspirin as an adjunct to compression therapy in healing chronic venous leg ulcers: a randomised double‐blinded placebo‐controlled trial [the ASPiVLU study] |

| Methods | Prospective, randomised, double blinded, 2 groups in parallel |

| Participants | 268 male or female Inclusion:

Exclusion criteria:

|

| Interventions |

Aspirin Arm: will receive oral dose 300 mg enteric coated aspirin daily for 24 weeks Placebo Arm: will receive oral dose of placebo tablet daily for 24 weeks All participants will be treated with compression |

| Outcomes | Primary measures:

Secondary measures:

|

| Starting date | March 2015 |

| Contact information | carolina.weller@monash.edu maria.lachina@monash.edu |

| Notes | Financial support from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (APP1069329). ASPiVLU is registered with Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry. Registration number: ACTRN12614000293662 Bayer Schering Pharm manufactured the aspirin and matching placebo. |

NCT02158806.

| Trial name or title | Low dose aspirin for venous leg ulcers (Aspirin4VLU) |

| Methods | Prospective, randomised, double blinded, 2 groups in parallel |

| Participants | Estimated enrolment: 354 patients; 18 years or older; both genders Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

| Interventions | Experimental: aspirin 150 mg capsule once daily for up to 24 weeks Placebo comparator: inert capsule matching aspirin capsule once daily for up to 24 weeks |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures

|

| Starting date | January 2015 |

| Contact information | Andrew Jull a.jull@auckland.ac.nz; Chris Bullen c.bullen@auckland.ac.nz |

| Notes |

NCT02333123.

| Trial name or title | Aspirin for Venous Ulcers: Randomised Trial (AVURT) |

| Methods | Phase II randomised, double blind, parallel group, placebo‐controlled efficacy trial |

| Participants | Estimated enrolment: 100 patients; >18 years Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria:

|

| Interventions | Experimental: aspirin 300 mg once daily for up to 27 weeks Placebo comparator: placebo once daily for up to 27 weeks |

| Outcomes |

Primary outcome measures

Secondary outcome measures

|

| Starting date | 2015 |

| Contact information | not available |

| Notes |

Differences between protocol and review

Proportion of ulcer recurrence and mean time until recurrence were not specified in the protocol, but these outcomes appeared in the del Río Solá 2012 trial and were considered important by the review team, so they were included in the review.

Contributions of authors

Paulo de Oliveira Carvalho: conceived the review; designed the review; coordinated the review; extracted data; checked the quality of data extraction; undertook and checked quality assessment; analysed or interpreted data; performed statistical analysis; checked the quality of the statistical analysis; produced the first draft of the review; contributed to writing or editing the review; made an intellectual contribution to the review; approved the final review prior to submission; secured funding; performed previous work that was the foundation of the current review; performed translations; and is a guarantor of the review.

Natiara Magolbo: conceived the review; designed the review; extracted data; undertook quality assessment; produced the first draft of the review; performed previous work that was the foundation of the current review; wrote to study author / experts / companies; and provided data.

Rebeca De Aquino: conceived the review; designed the review; extracted data; undertook quality assessment; produced the first draft of the review; performed previous work that was the foundation of the current review; wrote to study author / experts / companies; and provided data.

Carolina Weller: extracted data; analysed or interpreted data; contributed to writing or editing the review; made an intellectual contribution to the review; approved the final review prior to submission; advised on the review; and provided data.

Contributions of editorial base:

Editors: Nicky Cullum edited the protocol; advised on methodology, interpretation and protocol content; approved the final protocol prior to submission. Joan Webster: edited the protocol; advised on methodology, interpretation and protocol content; approved the final protocol prior to submission.

Managing Editors: Sally Bell‐Syer and Gill Rizzello, coordinated the editorial process; advised on interpretation and content. Edited the review.

Ruth Foxlee: designed the search strategy, Rocio Rodriguez Lopez ran the searches.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Evidence Based Actions Department From Marília Medical School ‐ FAMEMA, Brazil.

External sources

FAPESP‐ Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, Brazil.

This project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research via Cochrane Infrastructure funding to Cochrane Wounds. The views and opinions expressed therein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Systematic Reviews Programme, NIHR, NHS or the Department of Health, UK.

Declarations of interest

Paolo Eduardo de Oliveira Carvalho: none known. Natiara Magolbo: none known. Rebeca De Aquino: none known. Carolina Weller: none known.

New

References

References to studies included in this review

del Río Solá 2012 {published data only}

- Río Solá ML, Antonio J, Fajardo G, Vaquero Puerta C. Influence of aspirin therapy in the ulcer associated with chronic venous insufficiency. Annals of Vascular Surgery 2012;26(5):620‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Layton 1994 {published data only}

- Layton AM, Ibbotson SH, Davies JA, Goodfield MJ. Randomised trial of oral aspirin for chronic venous leg ulcers. Lancet 1994;16(344):164‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Ibbotson 1995 {published data only}

- Ibbotson SH, Layton AM, Davies JA, Goodfield MJ. The effect of aspirin on haemostatic activity in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulceration. British Journal of Dermatology 1995;132(3):422‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

ACTRN12614000293662 {unpublished data only}

- ACTRN12614000293662. Clinical effectiveness of aspirin as an adjunct to compression therapy in healing chronic venous leg ulcers: a randomised double‐blind placebo‐controlled trial [the ASPiVLU study]. https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=365858 (accessed 27 January 2016).

NCT02158806 {unpublished data only}

- NCT02158806. Low Dose Aspirin for Venous Leg Ulcers (Aspirin4VLU). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02158806 (accessed 27 January 2016).

NCT02333123 {unpublished data only}

- NCT02333123. Aspirin for Venous Ulcers: Randomised Trial (AVURT). https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02333123 (accessed 27 January 2016).

Additional references

Arnoldi 1968

- Arnoldi CC, Linderholm H. On the pathogenesis of the venous leg ulcer. Acta Chirurgica Scandinavica 1968;134(6):427‐40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ballard 2000

- Ballard JL, Bergan JJ, Sparks S. Pathogenesis of chronic venous insufficiency. In: Ballard JL, Bergan JJ editor(s). Chronic Venous Insufficiency: Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: Springer, 2000:17‐24. [Google Scholar]

Barron 2007

- Barron G, Jacob S, Kirsner R. Dermatologic complications of chronic venous disease: medical management and beyond. Annals of Vascular Surgery 2007;21(5):652‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Beebe‐Dimmer 2005

- Beebe‐Dimmer JL, Pfeifer JR, Engle JS, Schottenfeld D. The epidemiology of chronic venous insufficiency and varicose veins. Annals of Epidemiology 2005;15(3):175‐84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bergan 2007

- Bergan J, Schmid‐Schonbein G, Coleridge Smith P, Nicolaides A, Boisseau M, Eklof B. Chronic venous disease. Minerva Cardioangiology 2007;55(4):459‐76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Blankensteijn 2009

- Blankensteijn JD, Philip D. Leg ulcer treatment. Journal of Vascular Surgery 2009;49:804‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bobek 1966

- Bobek K, Cajzl L, Cepelak V, Slaisova V, Opatzny K, Barcal R. Study of phlebological disease frequency and the influence of etiologic factors [Étude de la fréquence des maladies phlébologiques et de l'influence de quelques facteurs étiologiques]. Phébologie 1966;19:217‐30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Burke 2006

- Burke A, Smith E, FitzGerald GA. Analgesics and antipyretics [Analgésicos e antipiréticos]. In: Goodman, Gilman editor(s). As Bases Farmacológicas da Terapêutica. Rio de Janeiro: McGraw‐Hill Interamericana do Brasil, 2006:601‐31. [Google Scholar]

Callam 1987

- Callam MJ, Harper DR, Dale JJ, Ruckley CV. Chronic ulcer of the leg: clinical history. British Medical Journal 1987;294(6584):1389‐91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cappelleri 1995

- Cappelleri JC, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Chalmers TC. Efficacy and safety of different aspirin dosages on vascular diseases in high‐risk patients. A metaregression analysis. Online Journal of Current Clinical Trials 1995;March 14:doc. no. 174. [PUBMED: 7889238] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

CONSORT 2010

- CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials). http://www.consort‐statement.org/downloads/consort‐statement (accessed 27 January 2016).

Coon 1973

- Coon WE, Willis PW, Keller JB. Venous thromboembolism and other venous disease in the Tecumseh community health study. Circulation 1973;48:406‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dalen 2006

- Dalen JE. Aspirin to prevent heart attack and stroke: what's the right dose?. American Journal of Medicine 2006;119(3):198‐202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

De Araujo 2003

- Araujo T, Valencia IC, Federman DG, Kirsner RS. Managing the patient with venous ulcers. Annals of Internal Medicine 2003;138:326‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dealey 2005

- Dealey C. The Care of Wounds: a Guide for Nurses. UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2005:143‐58. [Google Scholar]

Deeks 2011

- Deeks JJ, Higgins JPT, Altman DG, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group (Editors). Chapter 9: Analysing data and undertaking meta‐analysis. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Dorland 2007

- Dorland WAN. Dorland's Illustrated Medical Dictionary. 1st Edition. Saunders, 2007. [Google Scholar]

Falabella 1998

- Falabella A, Carson P, Eaglstein W, Falanga V. The safety and efficacy of a proteolytic ointment in the treatment of chronic ulcers of the lower extremity. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 1998;39(5):737‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Friedman 1990

- Friedman SA. The diagnosis and medical management of vascular ulcers. Clinics in Dermatology 1990;8(3‐4):30‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gilliland 1991

- Gilliland EL, Wolfe JH. Leg ulcers. BMJ 1991;303(6805):776‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Higgins 2011a

- Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ. Chapter 7: Selecting studies and collecting data. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011 . Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org. Wiley‐Blackwell.

Higgins 2011b

- Higgins JPT, Altman DG, on behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group (Editors). Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Jones 2008

- Jones JE, Robinson J, Barr W, Carlisle C. Impact of exudate and odour from chronic venous leg ulceration. Nursing Standard 2008;22(45):53‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jull 2007

- Jull AB, Arroll B, Parag V, Waters J. Pentoxifylline for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 3. [DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001733.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Kamber 1978

- Kamber V, Widmer LK, Munst G. Prevalence. In: Widmer LK editor(s). Peripheral Venous Disorders: Prevalence and Socio‐Medical Importance. Bern: Hans Huber Publishers, 1978:43‐50. [Google Scholar]

Lefebvre 2011