Abstract

Background

Several psychological studies have shown that depressive rumination is associated with the onset and severity of depression. However, it is unclear how rumination interacts with other predisposing factors to cause depression. In this study, we hypothesized that rumination mediates the association between depression and two predisposing factors of depression, ie, childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety.

Subjects and Methods

Between 2017 and 2018, 473 adult volunteers were surveyed using self-report questionnaires regarding the following: demographic information, rumination (Ruminative Responses Scale), trait anxiety (State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Y), and the experience of childhood maltreatment (Child Abuse and Trauma Scale). The effects of these factors on depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-9) were analyzed by multiple regression and path analysis to analyze the mediating effects of rumination. This study was conducted with approval from the relevant ethics committee.

Results

Multiple regression analysis using depression as a dependent variable demonstrated that trait anxiety, rumination, childhood maltreatment, and living alone were significantly associated with depression. Path analysis showed that childhood maltreatment had a positive effect on trait anxiety, rumination, and depression; trait anxiety had a positive effect on rumination and depression; and rumination had a positive effect on depression. Regarding indirect effects, the experience of childhood maltreatment increased rumination and depression indirectly via trait anxiety. Furthermore, the experience of childhood maltreatment increased depression indirectly via rumination, and trait anxiety significantly increased depression via rumination. In other words, rumination mediated the indirect effects of abusive experiences and trait anxiety on depression. This model accounted for 50% of the variance in depression in adult volunteers.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that rumination mediates the association between childhood maltreatment, trait anxiety, and depression in adulthood.

Keywords: rumination, trait anxiety, childhood maltreatment, depression, path analysis

Introduction

Childhood experiences of maltreatment have been reported as predisposing factors of depression.1–4 For example, women who were abused as children and adolescents have an increased risk of depression, and the degree of maltreatment experienced and the severity of their depression showed a linear dose-response relationship.5 There is a long time interval between the experience of maltreatment in childhood and the onset of depression in adulthood, and our previous cross-sectional studies suggested that affective temperaments, neuroticism, and trait anxiety mediate the long-term effects of childhood maltreatment.6–8 In these previous studies, we found that childhood maltreatment increases the negative evaluation of stress through its effects on personality traits, which may be a mechanism for exacerbating depression.6–8 Among these personality traits, several studies have suggested that high anxiety traits contribute to the development of depression by influencing behavioral, cognitive, and physiological responses and by increasing an individual’s vulnerability to stress.9

Depressive rumination is defined as the repetitive and passive thinking about one’s depressed mood, and the causes and consequences of that mood state.10 In recent years, there have been increasing lines of evidence suggesting an association between depressive rumination and depression.11 In a 30-day follow-up study of college students, Nolen-Hoeksema et al showed that students with more ruminative responses had longer-lasting and more severe depression.12 In a large, one-year longitudinal study of 1132 community residents between the ages of 25 and 75 years, Nolen-Hoeksema (2000) found that those with a high ruminative response style had a higher incidence of major depression than those with a low ruminative response style.13

Not only does rumination exacerbate depression and increase negative thinking, but it also impairs problem solving, interferes with instrumental behavior, and erodes social support.14 The Habit development, EXecutive control, Abstract processing, GOal discrepancies, and Negative bias (H-EX-A-GON) model has been established as an integrative model from a cognitive psychological perspective of the onset and continuation of depressive rumination.15 In the H-EX-A-GON model, various environmental and biological factors influence depressive rumination, and in particular, childhood maltreatment and unhelpful or overcontrolling parenting styles are factors that influence depressive rumination. Childhood maltreatment reportedly increases depression and unpleasant mood through rumination.16–18 On the other hand, Wang et al indicated a complex association in which rumination mediates the buffering effect of cognitive flexibility on the association between trait anxiety and depression.19 Therefore, it is assumed that depressive rumination plays a mediating role in the association between childhood maltreatment, trait anxiety, and depression. However, no comprehensive path analyses have been reported to date analyzing the mediating effects of depressive rumination and trait anxiety on the effects of childhood maltreatment on depression.

In this study, we assessed childhood maltreatment, trait anxiety, depressive rumination, and depression in adult volunteers using a questionnaire survey, and the associations among these factors and their mediating effects were investigated by path analysis. Our hypotheses were the following: first, childhood maltreatment influences trait anxiety; second, childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety further influence depressive rumination; and third, childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety affect depression in adulthood through their effects on depressive rumination.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

From April 2017 to April 2018, a self-administered questionnaire was distributed to adult volunteers by convenience sampling. A total of 473 individuals (207 men and 266 women; mean age: 41.3 ± 11.8 years), who gave written consent and valid responses, were surveyed anonymously using a demographic information questionnaire and three psychological questionnaires. The participants were informed that participation in the study was voluntary, that no disadvantage would result from nonparticipation, and that their personal information would be anonymized. This study was part of a larger study, which analyzed the results of several questionnaires.20 This study was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committee of Tokyo Medical University (study approval number: SH3502). This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (amended in Fortaleza in 2013).

Questionnaires

Ruminative Responses Scale (RRS)

RRS is a self-report questionnaire of 22 items, which evaluates the frequency of depressive rumination, each rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = almost always).21 The Japanese version used in this study was translated and confirmed for reliability and validity by Hasegawa.22 The total score of the 22 items of the RRS was used for the analysis. The subscores of reflection (5 items) and brooding (5 items) were also used for the analysis as subscales. In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficient calculated for the total score of this scale was 0.944, indicating very high internal consistency.

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory Form Y (STAI-Y)

The STAI-Y is a self-report questionnaire that assesses trait and state anxiety.23 The present study focused on trait anxiety, which reflects a relatively stable tendency to respond to anxiety-provoking experiences. The trait anxiety section of the questionnaire consists of 20 items, each of which was assessed using a 4-point Likert scale (1 = almost never, 2 = sometimes, 3 = often, and 4 = almost always). The Japanese version used in this study was developed and verified by Hidano et al.24 In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficient calculated for the total score of the trait anxiety subscale was 0.925, indicating very high internal consistency.

Child Abuse and Trauma Scale (CATS)

The CATS is a self-report questionnaire that assesses abusive experiences in childhood.25 This scale consists of 38 items that evaluate the type of family environment that the participants experienced as a child and how they felt they were treated by their parents. Each question is rated using a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = very often, and 4 = always). The Japanese version used in this study was translated and verified by Tanabe.26 In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficient calculated for the total score of this scale was 0.931, indicating very high internal consistency.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)

PHQ-9 is a self-report questionnaire for identifying major depressive episodes and the severity of depression.27 Depression symptoms during the previous two weeks were rated on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, and 3 = nearly every day). The Japanese version used in this study was translated and verified by Muramatsu et al.28 In the present study, Cronbach’s α coefficient calculated for the total score of this scale was 0.854, indicating very high internal consistency.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the demographic data and questionnaire data was conducted using the Pearson correlation coefficient or by the t-test (SPSS Statistics Version 25, IBM Armonk NY, USA). The path model was created and analyzed using Mplus software (version 8.0, Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) and the robust maximum likelihood estimation. Standardized coefficients of the covariance structure analysis are shown. Goodness-of-fit indices were not used because this model is a saturated model. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference between two groups.

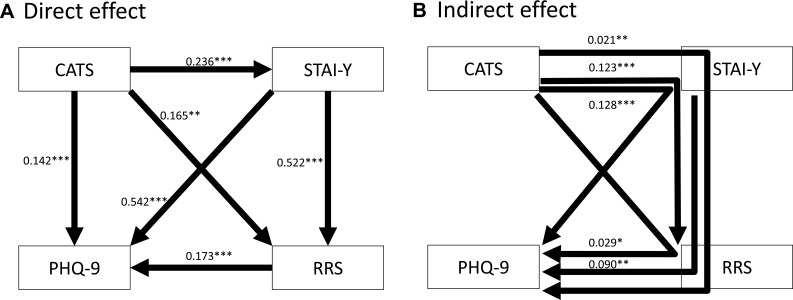

In the path model, childhood maltreatment influences trait anxiety, and trait anxiety influences depressive rumination. These three variables influence depression in adulthood. The mediating effects of trait anxiety and depressive rumination on the effects of childhood maltreatment on depression were analyzed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Results of the path model with the CATS (childhood maltreatment), STAI-Y (trait anxiety), RRS (rumination), and PHQ-9 (severity of depression). Direct effects (A) and indirect effects (B) between the variables are shown. The numbers indicate the standardized path coefficients. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results

Effects of Demographic Variables and Questionnaire Data on Depression

Demographic data, descriptive statistics for scores obtained from the RRS, STAI-Y, CATS, and PHQ-9, and their correlation with PHQ-9 scores or effects on PHQ-9 scores in 473 adults are shown in Table 1. Female, living alone, low subjective social status (1: lowest; 10: highest), previous psychiatric disease, and current psychiatric disease were associated with high PHQ-9 scores. No other demographic variables were associated with PHQ-9 scores. The STAI-Y score (trait anxiety), CATS total score, and RRS total score all positively correlated with the PHQ-9 score. Two subscores of the RRS score, namely, brooding and reflection, showed significant positive correlations with the PHQ-9 score, and the correlation with brooding was numerically larger.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics, Scores of STAI-Y, CATS, RRS, and PHQ-9, and Their Correlation with PHQ-9 Scores

| Characteristic or Measure | Value (Number or Mean ± SD) | Correlation with PHQ-9 score (r) or Effect on PHQ-9 Score (Mean ± SD of PHQ-9 Score, t-test) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 41.3 ± 11.8 | r = −0.024, p = 0.301 |

| Sex (male: female) | 207: 266 | Male 3.5 ± 4.0 vs female 4.6 ± 4.5, p = 0.007 (t-test) |

| Education years | 14.6 ± 1.8 | r = −0.069, p = 0.068 |

| Living alone (yes: no) | 99: 374 | Yes 5.2 ± 4.9 vs no 3.8 ± 4.1, p = 0.007 (t-test) |

| Employment (yes: no) | 465: 8 | Yes 4.1 ± 4.3 vs no 3.3 ± 5.4, p = 0.584 (t-test) |

| Subjective social status | 5.12 ± 1.63 | r = −0.288, p < 0.001 |

| Previous psychiatric disease (yes: no) | 47: 426 | Yes 7.19 ± 5.7 vs no 3.7 ± 4.0, p < 0.001 (t-test) |

| Current psychiatric disease (yes: no) | 15: 458 | Yes 8.0 ± 5.7 vs no 3.9 ± 4.2, p < 0.001 (t-test) |

| STAI-Y score (trait anxiety) | 43.1 ± 10.4 | r = 0.673, p < 0.001 |

| CATS score | 27.5 ± 20.7 | r = 0.320, p < 0.001 |

| RRS total score | 35.2 ± 11.4 | r = 0.518, p < 0.001 |

| RRS brooding score | 8.7 ± 3.3 | r = 0.468, p < 0.001 |

| RRS reflection score | 7.5 ± 2.7 | r = 0.298, p < 0.001 |

| PHQ-9 score | 4.1 ± 4.3 |

Notes: Data are presented as the mean ± SD or numbers. r = Pearson’s correlation coefficient.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; STAI-Y, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y; CATS, Child Abuse and Trauma Scale; RRS, Ruminative Responses Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Multiple Regression Analysis of Depression

The results of the multiple regression analysis of PHQ-9 scores are shown in Table 2. Eleven independent variables were analyzed, and multiple regression analysis identified the following 4 independent variables to be significantly associated with PHQ-9 score: living alone, STAI-Y score (trait anxiety), CATS score, and RRS score. The other variables were not significantly associated with PHQ-9 score (F = 44.23, p < 0.001). There was no multicollinearity.

Table 2.

Results of Multiple Regression Analysis of PHQ-9 Score

| Positive Variable Selected | Beta | p | VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| STAI-Y score (trait anxiety) | 0.521 | < 0.001 | 1.633 |

| RRS score | 0.149 | < 0.001 | 1.642 |

| CATS score | 0.128 | < 0.001 | 1.193 |

| Living alone | 0.071 | 0.044 | 1.179 |

| Sex | 0.055 | 0.109 | 1.117 |

| Current psychiatric disease | 0.049 | 0.185 | 1.313 |

| Subjective social status | –0.046 | 0.224 | 1.340 |

| Previous psychiatric disease | 0.035 | 0.355 | 1.357 |

| Age | 0.032 | 0.410 | 1.391 |

| Education years | 0.018 | 0.659 | 1.613 |

| Employment | –0.010 | 0.771 | 1.026 |

| Adjusted R2 = 0.502, F = 44.23, p < 0.001 | |||

Notes: The 11 independent variables were as follows: age, sex (male = 1, female = 2), education years, employment status (non-employed = 1, employed = 2), living alone (no = 1, yes = 2), previous psychiatric disease (no = 1, yes = 2), current psychiatric disease (no = 1, yes = 2), subjective social status, RRS score, STAI-Y score, and CATS score.

Abbreviations: Beta, standardized partial regression coefficient; VIF, variance inflation factor; RRS, Ruminative Responses Scale; STAI-Y, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory form Y; CATS, Child Abuse and Trauma Scale; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire-9.

Path Analysis of Childhood Maltreatment, Trait Anxiety, Rumination, and Depression

In the path model, childhood maltreatment (CATS), trait anxiety (STAI-Y), rumination (RRS), and depression (PHQ-9) were used as observed variables (Figure 1). Childhood maltreatment increased trait anxiety, rumination, and depression significantly and directly (Figure 1A). In addition, trait anxiety increased rumination and depression significantly and directly, and rumination increased depression significantly and directly (Figure 1A).

Regarding indirect effects, childhood maltreatment increased rumination and depression indirectly via trait anxiety (standardized coefficients 0.123 [p < 0.001] and 0.128 [p < 0.001], respectively) (Figure 1B). Childhood maltreatment increased depression indirectly via rumination (0.029, p = 0.012), trait anxiety increased depression indirectly via rumination (0.090, p = 0.001), and childhood maltreatment increased depression indirectly via the 2 paths involving trait anxiety and rumination (0.021, p = 0.006). These results suggest that rumination mediates the indirect effects of childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety on depression. The R2 for PHQ-9 scores was 0.5, indicating that this model accounts for 50% of the variance in depression.

The two subscales of the RRS scale, namely, reflection and brooding, were also analyzed in the same path analysis as Figure 1 (data not shown). Although reflection was significantly associated with childhood maltreatment, trait anxiety, and depression, it showed no mediation effect on the association between childhood maltreatment or trait anxiety and depression. On the other hand, brooding also showed significant correlations with childhood maltreatment, trait anxiety, and depression. Brooding showed a significant mediation effect between trait anxiety and depression, but no significant mediation effect between childhood maltreatment and depression.

Discussion

The main findings of our study are as follows. Trait anxiety mediated the effects of childhood maltreatment on rumination and depression, and rumination mediated the effects of childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety on depression. These findings support the hypothesis that childhood maltreatment influences depression in adulthood through trait anxiety and depressive rumination.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting the mediating effects of rumination and trait anxiety on the effects of childhood maltreatment on depression. On the other hand, some previous studies investigated these associations to some extent. The present finding that trait anxiety mediated the effects of childhood maltreatment on depression was consistent with our previous study of another sample.8 Furthermore, the finding that rumination mediates the association between childhood maltreatment and depression was consistent with the trends suggested by some previous studies.16,17,29

In the cross-sectional study of pregnant women by O’Mahen et al, the effect of childhood emotional neglect on depression was mediated by behavioral avoidance, whereas the effect of childhood emotional abuse on depression was mediated by the brooding subtype of depressive rumination.18 The trends of their results appeared to be similar to the trends of our results. However, we were unable to compare the differences in results by maltreatment subtype between this previous study and our present study, because O’Mahen et al used the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire, whereas we used the CATS. Furthermore, regarding the subtypes of rumination, in the study by O’Mahen et al, brooding was shown to correlate with depressive symptoms, whereas reflection was not. In contrast, in the present study, both brooding and reflection were associated with the severity of depression, and this result was consistent with that of many previous studies.16,22 The differences between the study by O’Mahen et al and our study might also be owing to differences in the characteristics of the subjects (race, sex, etc.) and the depression scale used.

Trait anxiety is a major risk factor for depression as well as for anxiety disorders.9 Trait anxiety has a biological basis, as it can be hereditary and is known to involve the hypothalamic-pituitary axis, which induces overreactions to stressful life events and associated cognitive behavioral dysfunction. Individuals with high levels of trait anxiety react to stressful events by stimulating the body’s dysfunctional neurocognitive cascade, which increases the individual’s sensitivity to stress.9,30 This is then likely to induce behavioral and cognitive changes that ultimately lead to depression.9,30 Rumination reportedly mediates the cushioning effect of cognitive flexibility on the association between trait anxiety and depression.19 The pathway identified in the present study, namely, that the effect of trait anxiety on depression is mediated by increased rumination, may be explained by the close association between trait anxiety and rumination, as demonstrated by the studies presented above.

The results of the present analysis indicate that childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety are background factors for the development of rumination. Preventing childhood maltreatment can lead to the prevention of depression, but a person’s previous history of maltreatment cannot be changed. However, if the presence of trait anxiety and rumination as mediating factors is recognized in abused victims through their clinical assessment, it can be expected that interventions for these mediating factors will reduce their depression. Therefore, the early intervention of these factors, including cognitive behavioral therapy focusing on rumination, is clinically important in terms of preventing the onset and severity of depression.15 The H-EX-A-GO-N model introduced in the Introduction section indicates that treatments and assessments for depressive rumination should be developed taking into account various mechanisms, such as habit development, executive control, abstract processing, goal discrepancies, and negative bias.15 Our present study suggests that childhood maltreatment and trait anxiety are important factors for elucidating the mechanisms of depressive rumination and developing treatment methods for depressive rumination.

As this study was a questionnaire-based study and relied on the participants’ memories, there is a possibility of memory bias. In addition, as the study was conducted on adult volunteers, there are limitations in generalizing the results to patients with depression. Furthermore, as this was a transverse study, a long-term follow-up study is needed to conclude causality. The background of high trait anxiety of the participants may be due not only to their experience of maltreatment, which was analyzed in this study, but also to various other factors, such as being bullied, a low nurturing environment, and the experience of harassment. In addition, age differences in the characteristics of rumination and the association of rumination with depression have been reported.31,32 As the present study did not consider the effects of age in the path analysis, the effects of age on rumination and depression should be confirmed by path analysis and in older adults.

Conclusions

This study is the first to report that trait anxiety and depressive rumination mediate the association between childhood maltreatment and depression in adulthood, in a non-clinical population with a limited age range. Future large-scale prospective studies on community residents are needed to further clarify the causal association between these factors.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nobutada Takahashi of Fuji Psychosomatic Rehabilitation Institute Hospital, Dr. Hiroshi Matsuda of Kashiwazaki Kosei Hospital, Dr. Yasuhiko Takita (deceased) of Maruyamasou Hospital, and Dr. Yoshihide Takaesu of Izumi Hospital for their collection of subject data. We thank Professor Akira Hasegawa for his generous permission for the use of the Ruminative Responses Scale. We thank Dr. Helena Popiel of the Department of International Medical Communications, Tokyo Medical University, for editorial review of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, acquisition of the data, or analysis and interpretation of the data; took part in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

Jiro Masuya has received personal compensation from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Astellas, and Meiji Yasuda Mental Health Foundation, and grants from Pfizer. Takeshi Inoue has received personal fees from Mochida Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Janssen Pharmaceutical, MSD, Taisho Toyama Pharmaceutical, Yoshitomiyakuhin, and Daiichi Sankyo; grants from Shionogi, Astellas, Tsumura, and Eisai; and grants and personal fees from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Kyowa Pharmaceutical Industry, Pfizer, Novartis Pharma, and Meiji Seika Pharma; and is a member of the advisory boards of Pfizer, Novartis Pharma, and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma. Masahiko Ichiki has received personal compensation from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Mochida Pharmaceutical, Meiji Seika Pharma, Janssen Pharmaceutical, Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, MSD, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, and Eisai; grants from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Eli Lilly, Eisai, Shionogi, Takeda Pharmaceutical, MSD, and Pfizer; and is a member of the advisory board of Meiji Seika Pharma. The other authors declare that they have no actual or potential conflicts of interest associated with this study.

References

- 1.Toda H, Inoue T, Tsunoda T, et al. The structural equation analysis of childhood abuse, adult stressful life events, and temperaments in major depressive disorders and their influence on refractoriness. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:2079–2090. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S82236 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caspi A, Sugden K, Moffitt TE, et al. Influence of life stress on depression: moderation by a polymorphism in the 5-HTT gene. Science. 2003;301:386–389. doi: 10.1126/science.1083968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Magee WJ. Childhood adversities and adult depression: basic patterns of association in a US national survey. Psychol Med. 1993;23:679–690. doi: 10.1017/S0033291700025460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Infurna MR, Reichl C, Parzer P, et al. Associations between depression and specific childhood experiences of abuse and neglect: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;190:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wise LA, Zierler S, Krieger N, Harlow BL. Adult onset of major depressive disorder in relation to early life violent victimisation: a case-control study. Lancet. 2001;358:881–887. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06072-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nakai Y, Inoue T, Toda H, et al. The influence of childhood abuse, adult stressful life events and temperaments on depressive symptoms in the nonclinical general adult population. J Affect Disord. 2014;158:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ono K, Takaesu Y, Nakai Y, et al. Associations among depressive symptoms, childhood abuse, neuroticism, and adult stressful life events in the general adult population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:477–482. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S128557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Uchida Y, Takahashi T, Katayama S, et al. Influence of trait anxiety, child maltreatment, and adulthood life events on depressive symptoms. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:3279–3287. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S182783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weger M, Sandi C. High anxiety trait: a vulnerable phenotype for stress-induced depression. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nolen-Hoeksema S. The response styles theory. In: Papageorgiou C, Wells A, editors. Depressive Rumination: Nature, Theory, and Treatment. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2004:107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visted E, Vøllestad J, Nielsen MB, Schanche E. Emotion regulation in current and remitted depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2018;9:756. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102:20–28. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.1.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psychol. 2000;109:504–511. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.3.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolen-Hoeksema S, Wisco BE, Lyubomirsky S. Rethinking Rumination. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2008;3:400–424. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2008.00088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watkins ER, Roberts H. Reflecting on rumination: consequences, causes, mechanisms and treatment of rumination. Behav Res Ther. 2020;127:103573. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2020.103573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raes F, Hermans D. On the mediating role of subtypes of rumination in the relationship between childhood emotional abuse and depressed mood: brooding versus reflection. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25:1067–1070. doi: 10.1002/da.20447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conway M, Mendelson M, Giannopoulos C, Csank PA, Holm SL. Childhood and adult sexual abuse, rumination on sadness, and dysphoria. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28:393–410. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Mahen HA, Karl A, Moberly N, Fedock G. The association between childhood maltreatment and emotion regulation: two different mechanisms contributing to depression? J Affect Disord. 2015;174:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang T, Li M, Xu S, et al. Relations between trait anxiety and depression: a mediated moderation model. J Affect Disord. 2019;244:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seki T, Shimura A, Miyama H, et al. Influence of parenting quality and neuroticism on perceived job stressors and psychological and physical stress response in adult workers from the community. Neuropsych Dis Treat. 2020;16:2007–2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treynor W, Gonzalez R, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination reconsidered: a psychometric analysis. Cognit Ther Res. 2003;27:247–259. doi: 10.1023/A:1023910315561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hasegawa A. Translation and initial validation of the Japanese version of the Ruminative Responses Scale. Psychol Rep. 2013;112:716–726. doi: 10.2466/02.08.PR0.112.3.716-726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI (Form Y). Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hidano N, Fukuhara M, Iwawaki M, Soga S, Spielberger C. State–Trait Anxiety Inventory-Form JYZ. Tokyo: Japan UNI Agency; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sanders B, Becker-Lausen E. The measurement of psychological maltreatment: early data on the Child Abuse and Trauma Scale. Child Abuse Negl. 1995;19:315–323. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(94)00131-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tanabe H, Ozawa S, Goto K Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Child Abuse and Trauma Scale (CATS). The 9th Annual Meeting of the Japanese Society for Traumatic Stress Studies: Kobe, Japan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muramatsu K, Miyaoka H, Kamijima K, et al. The patient health questionnaire, Japanese version: validity according to the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview-plus. Psychol Rep. 2007;101:952–960. doi: 10.2466/pr0.101.3.952-960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huh HJ, Kim KH, Lee HK, Chae JH. The relationship between childhood trauma and the severity of adulthood depression and anxiety symptoms in a clinical sample: the mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies. J Affect Disord. 2017;213:44–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sandi C, Richter-Levin G. From high anxiety trait to depression: a neurocognitive hypothesis. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ricarte Trives JJ, Navarro Bravo B, Latorre Postigo JM, Ros Segura L, Watkins E. Age and gender differences in emotion regulation strategies: autobiographical memory, rumination, problem solving and distraction. Span J Psychol. 2016;19:E43. doi: 10.1017/sjp.2016.46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ricarte J, Ros L, Serrano JP, Martínez-Lorca M, Latorre JM. Age differences in rumination and autobiographical retrieval. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20:1063–1069. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1060944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]