Highlights

-

•

This study investigated the duration of persistence of chikungunya-related arthralgia.

-

•

Statisticalanalysis of multiple cohorts of chikungunya patients was performed.

-

•

First estimates of the average rate of chronic chikungunya virus arthralgia resolution were calculated.

-

•

Varying rates of arthralgia resolution are associated with age and other factors.

KEYWORDS: Chikungunya, Arthralgia, Joint pain, Virus, Infection, Chronic disease

Abstract

Background

Arthralgia, persistent pain or stiffness of the joints, is the hallmark symptom of chronic chikungunya virus (CHIKV) disease. Associated with significant disability and reduced quality of life, arthralgia can persist for many months following CHIKV infection. Understanding the expected duration of arthralgia persistence is important for managing clinical expectations at the individual-level as well as for estimating long-term burdens on population health following a CHIKV epidemic.

Methods

A review of cohort studies reporting the prevalence of arthralgia post-CHIKV infection over multiple time points was conducted. Generalized linear models were used to estimate the average rate of arthralgia resolution following CHIKV infection.

Results

Sixteen cohort studies matching the inclusion criteria were identified and included in the analysis. An average rate of arthralgia resolution of 10.85% (95% confidence interval (CI) 9.05–12.66%) per month was estimated across studies, corresponding to an expected median time to arthralgia resolution of 6.39 months (95% CI 5.48–7.66 months) and an expected arthralgia prevalence of 72.21% (95% CI 68.40–76.23%) at 3 months post-CHIKV infection.

Conclusions

Estimates of the average rate of arthralgia resolution and the expected prevalence of arthralgia over time post-CHIKV infection were derived. These can help inform expectations regarding the long-term public health burdens associated with CHIKV epidemics.

1. Introduction

First identified in Tanzania in 1952, chikungunya virus (CHIKV) is an RNA Alphavirus transmitted to humans through the bite of infected Aedes mosquitoes. Since its identification, occasional outbreaks have been observed in Africa and Asia, and in 2004 a major outbreak in Kenya spread rapidly to surrounding territories in the Indian Ocean (Sanyaolu et al., 2021; Staples et al., 2009). Since then CHIKV has been identified in over 60 countries, extending its reach to the Americas and Europe (World Health Organization). Four different genotypes of CHIKV have been identified through phylogenetic analysis: the West African genotype, the Asian genotype, the East/Central/South African (ECSA) genotype, and the Indian Ocean lineage (IOL) genotype, which emerged within the ECSA clade (Powers et al., 2000; Wahid et al., 2017).

CHIKV infection is responsible for a biphasic disease that typically begins 2–6 days post infection. The acute phase of CHIKV disease is characterized by an onset of fever, usually accompanied by debilitating joint pain. Other symptoms can include muscle pain, rash, headache, fatigue, and nausea. Following the acute phase of infection, arthralgia (pain in one or multiple joints) and other musculoskeletal disorders can persist in some patients for a period of months or years, known as the chronic phase of infection (Staples et al., 2009). A recent meta-analysis estimated that 43% (95% confidence interval (CI) 35–52%) of patients had chronic symptoms of CHIKV, defined as lasting more than 3 months (Paixão et al., 2018). Although there is a consensus that most of the patients’ symptoms will resolve over time, a large uncertainty exists regarding the proportion of CHIKV-infected individuals going on to suffer from chronic symptoms, with reports ranging from 3% to 83%, and the rate of resolution unclear (Paixão et al., 2018). This means that the proportion of CHIKV-infected individuals whose arthralgia symptoms resolve may never reach 100%.

Arthralgia is the hallmark of chronic CHIKV disease. Whether continuous in nature or following a relapsing–remitting pattern, this debilitating joint pain is associated with significant disability and impaired quality of life (Elsinga et al., 2017; Watson et al., 2020). To date, no commercial vaccine or specific antiviral drugs exist for the prevention or treatment of infection with CHIKV, with clinical management primarily focused on the relief of symptoms. Understanding how long the arthralgia lasts for is therefore critical to managing clinical expectations and plays an important role in clinical decision-making concerning the risk/benefit of starting immunomodulating medications such as methotrexate (Simon et al., 2015). This information is needed to provide patients with a realistic timeframe for symptom resolution and to provide public health officials with a way to estimate the likely long-term burden on health following a CHIKV epidemic. Further, an increased understanding of the rate of resolution of CHIKV symptoms can aid the optimization of clinical trial designs assessing the short- and long-term efficacy profiles of CHIKV vaccines. In this study, cohort studies that have followed individuals after CHIKV infection and tracked their symptoms over time were identified and simple statistical models were used to estimate the average rate of arthralgia resolution.

2. Methods

The literature was searched for published cohort studies of chronic chikungunya disease that included clinical follow-up for at least two time-points from 1 month post-onset of acute symptoms. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) cohort studies reporting longitudinal follow-up of patients after acute CHIKV infections; (2) reporting of the initial number of patients with acute symptomatic CHIKV infection; (3) reporting of the prevalence of arthralgia in ≥80% of the initial cohort at more than one time-point from 1 month post-infection onwards; (4) a description of the criteria used for classification of symptomatic or resolved patients; (5) a description of the methodology used for patient evaluation and data collection.

A search of the PubMed database was performed to identify relevant eligible studies published between January 2001 and December 2020. Articles in all languages were accepted provided that there was an English-language abstract. Search terms employed were “chikungunya” or “post-chikungunya” in combination with “arthralgia”, “arthritis”, “joint pain”, “complication” or “manifestation” and in combination with “chronic”, “persistent” or “long-term”. Review articles were excluded. Reference lists of identified articles and reviews were searched by hand. Initial screening by title and abstract identified articles potentially meeting the criteria. Duplicate articles were removed and full texts of the remaining articles were reviewed in order to confirm that they met all of the criteria for inclusion. Data were extracted on two separate occasions. Any ambiguities in interpretation were resolved between two reviewers (MO and HW). Key missing data or confirmation of data interpretation were sought directly from corresponding authors for eligible and potentially eligible studies where necessary. Additional unpublished data provided by authors were included in the analysis.

For studies that met all inclusion criteria, the following information was extracted: initial cohort size, the timing of follow-up assessments, number of patients evaluated at each time-point, proportion of patients from the initial cohort with arthralgia at each reported time-point, the proportion of children included in each study, the definition of symptoms included, and the methodology for follow-up assessment. The presence of arthralgia was recorded as a binary variable. Where available, the average or median age of the patients and the ratio of male to female patients were also extracted for each cohort. The viral genotype responsible for each outbreak was identified either from the cohort publication or from other published reports on the same chikungunya outbreak.

2.1. Statistical models

Generalized linear models (GLMs) were used to estimate the average resolution rate of individuals suffering from arthralgia following CHIKV infection across studies, shown in equation 1:

| (1) |

where is the expected number of patients with arthralgia, , given the number of months post CHIKV infection, , the monthly rate of arthralgia resolution, , modelled with an offset of the number of patients followed up at each time point, . The reported prevalence of arthralgia over time was assumed to follow a quasipoisson distribution to account for overdispersion in the underlying data. The expected prevalence of arthralgia over time was then calculated, as shown in equation 2:

| (2) |

A separate GLM was fitted with study-specific estimated rates of arthralgia resolution to investigate the heterogeneity in estimates across studies. In addition, separate GLMs were fitted, allowing estimates of the arthralgia rate of resolution to vary separately by genotype, cohort sex ratio, median cohort age, and the method of patient follow-up (in-person vs telephone).

3. Results

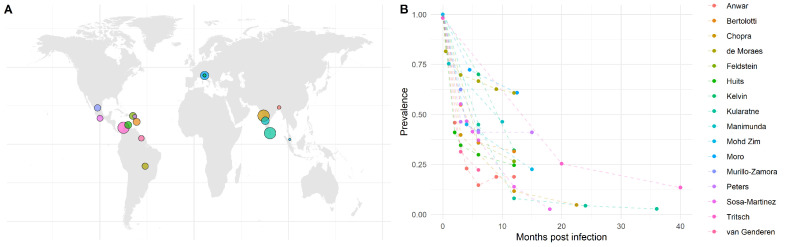

The literature search generated 375 hits. Most studies reporting chronic post-chikungunya arthralgia only reported prevalence at one time-point or only described patients with persistent symptoms. Data were extracted from the 16 cohort studies meeting the inclusion criteria. Included cohort studies were located throughout the Americas, Asia, and Europe, as shown in Figure 1A, with initial cohort study sizes ranging from 40 to 512 patients with CHIKV disease. The cohort studies focused primarily on adult populations, with only small proportions of children (0–18%) included in each cohort (Supplementary Material Table S1). The duration of follow-up across studies ranged from 6 to 40 months post-CHIKV infection (Table 1). The reported prevalence of arthralgia by month post-CHIKV infection for each cohort study is shown in Figure 1B. Only three of the 16 studies were conducted retrospectively (Table 1), with eight of the studies using in-person clinical examinations for determining the persistence of arthralgia and the other eight using telephone interviews. All but one study systematically used laboratory confirmation of CHIKV infection for recruitment into the cohort (Table 1).

Figure 1.

(A) Map of the study locations. Colored points indicate the location of each study, where the point size represents the relative study sample size. (B) Reported prevalence of arthralgia for each study by month post chikungunya virus infection.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies included in the analysis

| Study | Location | Initial number | Number of follow-ups | Follow-up time (months) | CHIKV genotype | % Female | Median age (years) | Age category | In-person/ telephone |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Anwar et al., 2020) | Bangladesh | 48 | 5 | 12 | ECSA/IOL | 52 | 32 | <40 | In-person |

| (Bertolotti et al., 2020) | Martinique | 167 | 3 | 12 | Asian | 64 | >50 | ≥40 | Phone |

| (Chopra et al., 2012) | India | 509 | 3 | 22.5 | ECSA/IOL | 56 | 25–44 | <40 | In-person |

| (de Moraes et al., 2020) | Brazil | 134 | 5 | 12 | ECSA/IOL | 60 | 39 | <40 | In-person |

| (Feldstein et al., 2017) | US Virgin Islands | 165 | 2 | 12 | Asian | 65 | 52 | ≥40 | Phone |

| (Huits et al., 2018) | Aruba | 171 | 4 | 12 | Asian | 68 | 49 | ≥40 | Phone |

| (Kelvin et al., 2011) | Italy | 50 | 2 | 12 | ECSA/IOL | - | - | - | In-person |

| (Kularatne et al., 2012) | Sri Lanka | 512 | 4 | 36 | ECSA/IOL | 54 | <33 | <40 | In-person |

| (Manimunda et al., 2010) | India | 203 | 2 | 10 | ECSA/IOL | 53 | 35 | <40 | In-person |

| (Mohd Zim et al., 2013) | Malaysia | 40 | 2 | 15 | ECSA/IOL | 58 | >40 | ≥40 | Phone |

| (Moro et al., 2012) | Italy | 250 | 2 | 12.5 | ECSA/IOL | 54 | >60 | ≥40 | In-person |

| (Murillo-Zamora et al., 2017) | Mexico | 136 | 2 | 6 | Asian | 68 | 40–64 | ≥40 | Phone |

| (Peters et al., 2018) | Sint Maarten | 56 | 3 | 15 | Asian | 54 | 47 | ≥40 | Phone |

| (Sosa-Martínez et al., 2018) | Mexico | 116 | 6 | 18 | Asian | 67 | 51 | ≥40 | In-person |

| (Chang et al., 2018; Tritsch et al., 2020) | Colombia | 494 | 2 | 40 | Asian | 80 | 49 | ≥40 | Phone |

| (van Genderen et al., 2016) | Suriname | 98 | 2 | 6 | Asian | 68 | 32 | <40 | Phone |

CHIKV, chikungunya virus; ECSA, Central/South African; IOL, Indian Ocean lineage.

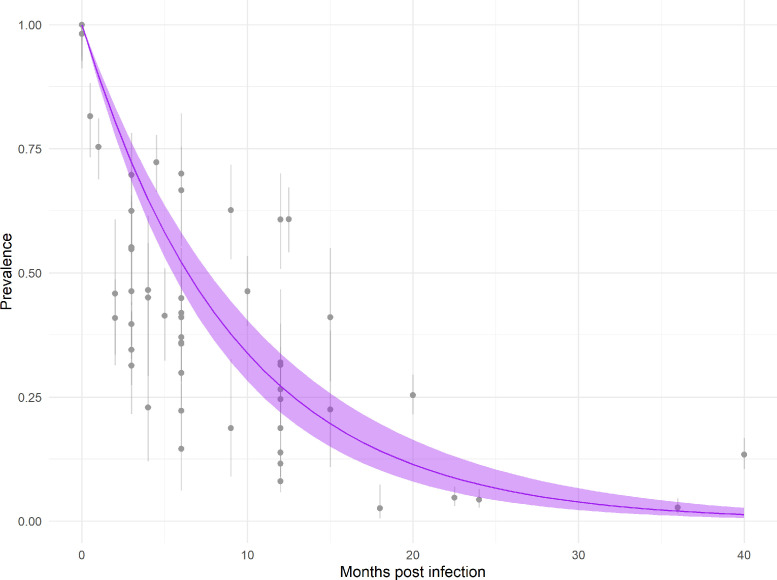

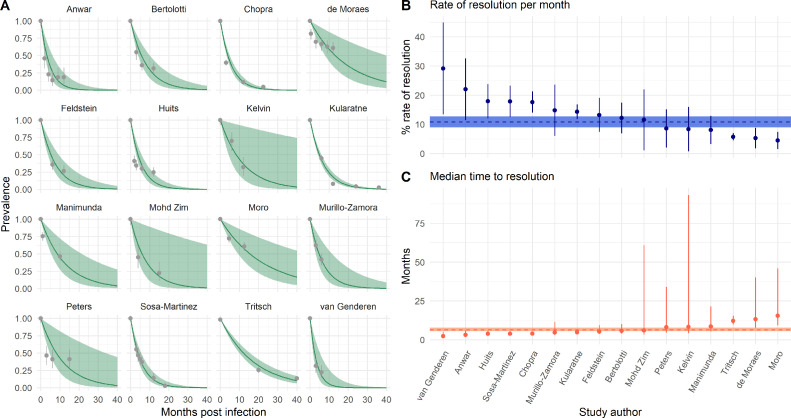

The average rate of arthralgia resolution estimated across studies was 10.85% (95% CI 9.05–12.66%) per month (Figure 2). This corresponds to an estimated median time to arthralgia resolution of 6.39 months (95% CI 5.48–7.66 months) and an expected arthralgia prevalence of 72.21% (95% CI 68.40–76.23%) at 3 months and of 27.19% (95% CI 21.89–33.78%) at 12 months post-CHIKV infection. Study-specific estimated rates of arthralgia resolution ranged from 4.49% (95% CI 1.51–7.47%) per month in Moro et al., conducted in Italy, to 29.13% (95% CI 13.42–44.83%) per month in van Genderen et al., conducted in Suriname (Figure 3). These estimates correspond to a median time to resolution of 15.44 months (95% CI 9.28–45.95 months) in Moro et al., and 2.38 months (95% CI 1.55–5.17 months) post-CHIKV infection in van Genderen et al. (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Estimated prevalence of arthralgia by months post-chikungunya virus infection. Gray points and lines indicate the reported mean prevalence of arthralgia and the 95% binomial confidence intervals. The purple line and ribbon show the mean and 95% confidence interval for expected arthralgia prevalence estimated across all studies.

Figure 3.

Estimated rates of resolution by study. (A) Estimated prevalence of arthralgia by months post infection by study. The green lines and ribbons indicate the model mean and 95% confidence interval estimates. The gray points and lines indicate the reported prevalence of arthralgia and 95% binomial confidence intervals. (B) Estimated rate of resolution per month by study. The points and lines indicate mean and 95% confidence intervals. The horizontal dashed line and ribbon indicate the mean and 95% confidence interval estimates from summary model 1. (C) Estimated median time to resolution by study. The points and lines indicate the mean and 95% confidence intervals. The horizontal dashed line and ribbon indicate the mean and 95% confidence interval estimates from summary model 1.

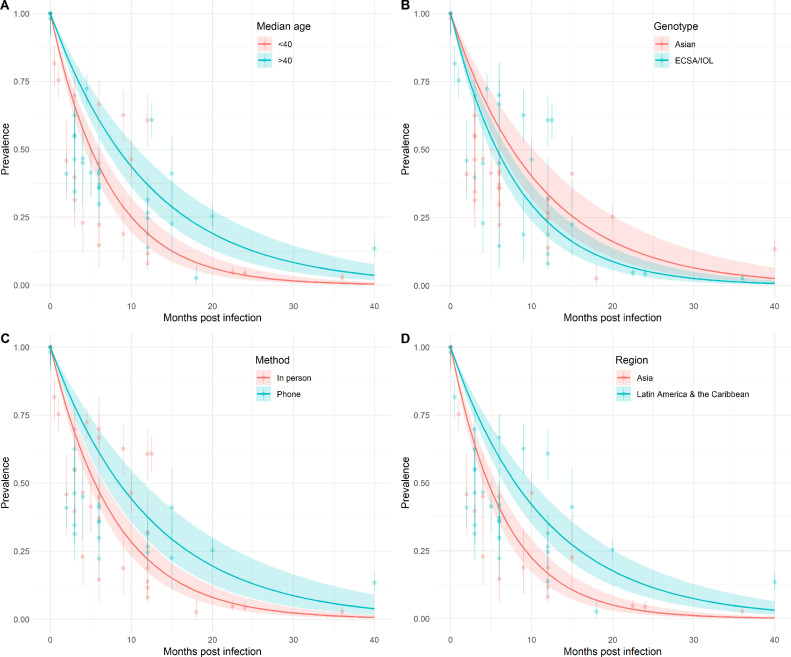

The cohort sex ratio and median age was available for 15 of the 16 studies (Table 1). Cohorts were grouped by age using the reported median age, as shown in Table 1. A mean monthly rate of arthralgia resolution of 13.84% (95% CI 11.34–16.33%) was estimated for studies with median age <40 years and a mean rate of 8.30% (95% CI 6.43–10.17%) for those with a median age ≥40 years (Figure 4A). No significant differences were observed in the mean monthly rates of arthralgia resolution between the Asian and ECSA/IOL genotypes (Figure 4B). A mean rate of arthralgia resolution of 9.10% (95% CI 6.81–11.39%) was estimated for studies where the Asian genotype was the dominant circulating genotype and of 12.14% (95% CI 9.91–14.37%) for studies where the ECSA/IOL is transmitted. Considering the method of cohort study follow-up, a mean rate of arthralgia resolution of 8.16% per month (95% CI 6.02–10.31%) was estimated for studies where patients were followed up via telephone interview. A mean rate of arthralgia resolution of 12.60% (10.51–14.70%) was estimated for studies that conducted in-person follow-ups (Figure 4C). In terms of the geographic location of the cohort studies, a mean rate of monthly arthralgia resolution of 14.94% (95% CI 12.29–17.59%) was estimated for studies conducted in Asia, compared to 8.68% (95% CI 6.86–10.50%) for studies conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean (Figure 4D). A monthly rate of resolution was not estimated for studies conducted in Europe due to small sample size (n = 2). No trend in study-specific rates of arthralgia resolution and cohort sex ratio was observed (Supplementary Material Figure S1).

Figure 4.

Prevalence of arthralgia by months post-chikungunya virus infection estimated by median cohort age (A), circulating viral genotype (B), study follow-up method (C), and region (D). The colored points and lines indicate the reported mean prevalence of arthralgia and 95% binomial confidence intervals. The colored lines and ribbon show the mean and 95% confidence interval for expected arthralgia prevalence estimated across studies by group.

4. Discussion

This analysis of arthralgia persistence using data from 16 longitudinal cohort studies confirms the resolution of chronic arthralgia after CHIKV infection over time. Previous analyses of chronic arthralgia prevalence combining data from multiple time-points yielded an estimate of 43% at 3 months post-infection (Paixão et al., 2018), while an analysis of studies by broad time categories estimated a prevalence of 40%, 36%, and 28% for follow-ups at 6–12 months, 12–18 months, and >18 months, respectively (Noor et al., 2020). An increased understanding of the likely course of chronic CHIKV disease is important for both the clinician and patient. The statistical modelling analysis in the present study provides estimates of the average rate of arthralgia resolution and the expected prevalence of arthralgia over time post-CHIKV infection. Arthralgia prevalence rates of 52.17% (95% CI 46.67–58.31%), 27.21% (95% CI 21.78–34.00%), and 14.19% (95% CI 10.17–19.82%) at 6, 12, and 18 months post-CHIKV infection, respectively, were estimated.

There are a number of potential reasons why the prevalence of chronic symptoms may vary considerably from one chikungunya cohort to another. In addition to biological differences between the patient populations and different viral genotypes, study methodology may also play a role in between-study heterogeneities. The patients’ arthralgia status may be determined by telephone, by face-to-face interview, or in the course of clinical examination, and with a binary question or by using verbal, numerical, or visual analogue scales. In addition, although arthralgia was always the predominant symptom, some studies recorded a composite of musculoskeletal symptoms as the principal endpoint (Supplementary Material Table S1). Considering the disparate ways in which data are collected across studies, it was aimed to estimate the rate of resolution of symptoms over time using data from cohorts in which repeat assessments have been conducted. The consistent definitions and methods used within each study allows us to derive internally consistent estimates of the rate of arthralgia resolution. It is important to note that few studies (4/15) had follow-up times greater than 15 months post-CHIKV infection (Table 1). Loss to follow-up is a frequent issue in longitudinal cohort studies and may bias study results if associated with the study outcome. To limit the potential for loss to follow-up bias, only studies that had ≤20% average loss to follow-up across all time points were included. One consequence of this focus on repeat assessments giving internally consistent estimates is that we were only able to include a small number of studies as compared to some previous analyses of post-CHIKV arthralgia. However, this allowed a greater degree of confidence in the estimates of the rate of symptom resolution. Future work comparing the rate of resolution of arthralgia symptoms in CHIKV-infected individuals and the prevalence of arthralgia in the general population (non-CHIKV-infected individuals) may aid our understanding of the mechanisms underpinning arthralgia resolution.

Large between-study heterogeneity was observed in estimated rates of arthralgia resolution. It was found that the method of patient follow-up was associated with rates of arthralgia resolution, with studies conducting in-person follow-up visits yielding faster rates of arthralgia resolution than those using telephone-based follow-up interviews (Figure 4C). This finding suggests a potential role for recall or other biases to vary by patient follow-up method, although further work is warranted to confirm this result. An earlier systematic review (van Aalst et al., 2017) also noted a lower number of chronic post-chikungunya manifestations recorded after clinical examination compared to patient questionnaires, and proposed the patients’ threshold for reporting a symptom may be lower than the physicians’ threshold for verifying a clinical sign. This may be related to the tendency for patient-reported outcomes like pain and stiffness to predominate over outcomes like joint swelling that are present on physical examination as predictors of patient disability (Watson et al., 2020). A significant difference was also found in the estimated rates of arthralgia resolution across regions, with a slower rate of resolution estimated for studies conducted in Latin America and the Caribbean as compared to those conducted in Asia. It is important to note the collinearity between region and circulating genotype, making the underlying drivers for this difference difficult to disentangle. Biological, cultural, and/or genotypic differences in the circulating virus are all possible drivers of this effect. It was also found that a younger median cohort age <40 years was associated with a quicker rate of arthralgia resolution than that of a median cohort age ≥40 years. The observed association of increased age as a risk factor for persisting post-CHIKV infection symptoms is supported by previous studies (Sissoko et al., 2009; Moro et al., 2012; Essackjee et al., 2013; Schilte et al., 2013; Yaseen et al., 2014; Murillo-Zamora et al., 2017; de Moraes et al., 2020). It is important to note that only a minority of children were included in the 16 cohort studies (Supplementary Material Table S1), making the estimates predominantly generalizable to adult populations. While some studies have previously reported a higher likelihood of chronic arthralgia among women (Moro et al., 2012; Rahim et al., 2016; Huits et al., 2018; de Moraes et al., 2020), no association between the cohort sex ratio and rates of arthralgia resolution were observed in the present study. The role of additional factors, such as the variable prevalence of comorbidities, on the rate of arthralgia resolution could not be explored in this analysis due to the number of different comorbidities and their inconsistent reporting. However, it is possible that the relationship between older age and slower rate of arthralgia resolution may be driven in part by a greater prevalence of comorbidities with age.

While arthralgia is the most frequently reported symptom in chronic chikungunya disease, other symptoms, musculoskeletal and psychological, are also frequent and burdensome. In the absence of any validated composite measure of disease severity for chikungunya, we have considered arthralgia as the best available indicator of persistent disease post-CHIKV infection. The study estimates of the average rate of arthralgia resolution and expected prevalence of arthralgia over time can be used to guide patient expectations regarding the duration of arthralgia post-CHIKV infection. These estimates can also inform the potential long-term health burdens that may be experienced by populations following CHIKV epidemics.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the following in providing clarifications and additional unpublished data for inclusion in this analysis: Dr Thiago Cerqueira-Silva, Professor Viviane Sampaio Boaventura (Fiocruz Insitute, Salvador, Brazil), Dr Ralph Huits (Institute for Tropical Medicine, Antwerp, Belgium), Dr Alyson A. Kelvin (Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada), Saeed Anwar (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada).

Declarations

Funding statement: The authors acknowledge funding from the European Research Council (Grant No. 804744) (MOD and HS).

Ethical approval: No ethical approval was required for this analysis.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2021.08.066.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- van Aalst M, Nelen CM, Goorhuis A, Stijnis C, Grobusch MP. Long-term sequelae of chikungunya virus disease: A systematic review. Travel Med Infect Dis [Internet] 2017;15:8–22. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.01.004. JanAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwar S, Taslem Mourosi J, Khan MF, Ullah MO, Vanakker OM, Hosen MJ. Chikungunya outbreak in Bangladesh (2017): Clinical and hematological findings. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet] 2020;14(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007466. FebAvailable from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti A, Thioune M, Abel S, Belrose G, Calmont I, Césaire R, et al. Prevalence of chronic chikungunya and associated risks factors in the French West Indies (La Martinique): A prospective cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet] 2020;14(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007327. MarAvailable from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang AY, Encinales L, Porras A, Pacheco N, Reid SP, Martins KAO, et al. Frequency of Chronic Joint Pain Following Chikungunya Virus Infection: A Colombian Cohort Study. Arthritis Rheumatol [Internet] 2018;70(4):578–584. doi: 10.1002/art.40384. AprAvailable from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra A, Anuradha V, Ghorpade R, Saluja M. Acute Chikungunya and persistent musculoskeletal pain following the 2006 Indian epidemic: a 2-year prospective rural community study. Epidemiol Infect [Internet] 2012;140(5):842–850. doi: 10.1017/S0950268811001300. MayAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsinga J, Gerstenbluth I, van der Ploeg S, Halabi Y, Lourents NT, Burgerhof JG, et al. Long-term Chikungunya Sequelae in Curaçao: Burden, Determinants, and a Novel Classification Tool. J Infect Dis [Internet] 2017;216(5):573–581. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix312. Sep 1Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essackjee K, Goorah S, Ramchurn SK, Cheeneebash J, Walker-Bone K. Prevalence of and risk factors for chronic arthralgia and rheumatoid-like polyarthritis more than 2 years after infection with chikungunya virus. Postgrad Med. 2013;89(1054):440–447. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2012-131477. J [Internet]AugAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein LR, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Staples JE, Weaver MR, Halloran ME, Ellis EM. Persistent Arthralgia Associated with Chikungunya Virus Outbreak, US Virgin Islands, December 2014-February 2016. Emerg Infect Dis [Internet] 2017;23(4):673–676. doi: 10.3201/eid2304.161562. AprAvailable from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Genderen FT, Krishnadath I, Sno R, Grunberg MG, Zijlmans W, Adhin MR. First Chikungunya Outbreak in Suriname; Clinical and Epidemiological Features. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet] 2016;10(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0004625. AprAvailable from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huits R, De Kort J, Van Den Berg R, Chong L, Tsoumanis A, Eggermont K, et al. Chikungunya virus infection in Aruba: Diagnosis, clinical features and predictors of post-chikungunya chronic polyarthralgia. PLoS One [Internet] 2018;13(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196630. Apr 30Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelvin AA, Banner D, Silvi G, Moro ML, Spataro N, Gaibani P, et al. Inflammatory cytokine expression is associated with chikungunya virus resolution and symptom severity. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet] 2011;5(8):e1279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001279. AugAvailable from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kularatne SAM, Weerasinghe SC, Gihan C, Wickramasinghe S, Dharmarathne S, Abeyrathna A, et al. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, and long-term outcomes of a major outbreak of chikungunya in a hamlet in sri lanka, in 2007: a longitudinal cohort study. J Trop Med [Internet] 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/639178. Feb 1Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manimunda SP, Vijayachari P, Uppoor R, Sugunan AP, Singh SS, Rai SK, et al. Clinical progression of chikungunya fever during acute and chronic arthritic stages and the changes in joint morphology as revealed by imaging. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet] 2010;104(6):392–399. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2010.01.011. JunAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohd Zim MA, Sam I-C, Omar SFS, Chan YF, AbuBakar S, Kamarulzaman A. Chikungunya infection in Malaysia: comparison with dengue infection in adults and predictors of persistent arthralgia. J Clin Virol [Internet] 2013;56(2):141–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2012.10.019. FebAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moraes L, Cerqueira-Silva T, Nobrega V, Akrami K, Santos LA, Orge C, et al. A clinical scoring system to predict long-term arthralgia in Chikungunya disease: A cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet] 2020;14(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0008467. JulAvailable from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moro ML, Grilli E, Corvetta A, Silvi G, Angelini R, Mascella F, et al. Long-term chikungunya infection clinical manifestations after an outbreak in Italy: a prognostic cohort study. J Infect [Internet] 2012;65(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2012.04.005. AugAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murillo-Zamora E, Mendoza-Cano O, Trujillo-Hernández B, Alberto Sánchez-Piña R, Guzmán-Esquivel J. Persistent arthralgia and related risks factors in laboratory-confirmed cases of Chikungunya virus infection in Mexico. Rev Panam Salud Publica [Internet] 2017;41:e72. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2017.72. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28614481 Jun 8Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noor FM, Hossain MB, Islam QT. Prevalence of and risk factors for long-term disabilities following chikungunya virus disease: A meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis [Internet] 2020;35 doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101618. MayAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paixão ES, Rodrigues LC, Costa M da CN, Itaparica M, Barreto F, Gérardin P, et al. Chikungunya chronic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg [Internet] 2018;112(7):301–316. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/try063. Jul 1Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CMM, Pijnacker R, Fanoy EB, Bouwman LJT, de Langen LE, van den Kerkhof JHTC, et al. Chikungunya virus outbreak in Sint Maarten: Long-term arthralgia after a 15-month period. J Vector Borne Dis [Internet] 2018;55(2):137–143. doi: 10.4103/0972-9062.242561. AprAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AM, Brault AC, Tesh RB, Weaver SC. Re-emergence of Chikungunya and O'nyong-nyong viruses: evidence for distinct geographical lineages and distant evolutionary relationships. J Gen Virol [Internet] 2000;81(Pt 2):471–479. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-471. https://www.microbiologyresearch.org/content/journal/micro/10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-471 FebAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim AA, Thekkekara RJ, Bina T, Paul BJ. Disability with Persistent Pain Following an Epidemic of Chikungunya in Rural South India. J Rheumatol [Internet] 2016;43(2):440–444. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141609. FebAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanyaolu A, Okorie C, Badaru O. Chikungunya Epidemiology: A Global Perspective [Internet]. [cited 2021 Apr 1] 2021. Available from: https://smjournals.com/public-health-epidemiology/fulltext/smjphe-v2-1028.php

- Schilte C, Staikowsky F, Couderc T, Madec Y, Carpentier F, Kassab S, et al. Chikungunya virus-associated long-term arthralgia: a 36-month prospective longitudinal study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2013;7(3):e2137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002137. Mar 21Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon F, Javelle E, Cabie A, Bouquillard E, Troisgros O, Gentile G, et al. French guidelines for the management of chikungunya (acute and persistent presentations). November 2014. Med Mal Infect [Internet] 2015;45(7):243–263. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2015.05.007. JulAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sissoko D, Malvy D, Ezzedine K, Renault P, Moscetti F, Ledrans M, et al. Post-epidemic Chikungunya disease on Reunion Island: course of rheumatic manifestations and associated factors over a 15-month period. PLoS Negl Trop Dis [Internet]. 2009;3(3):e389. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000389. Mar 10Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sosa-Martínez MJ, Orea-Flores M, Vázquez-Cruz I, Palacios-Castillo V, Juanico-Morales G, Pérez-Mijangos L. Characterization of chronic clinical manifestations in patients with chikungunya fever. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc [Internet] 2018;56(3):239–245. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30376273 Oct 25Available from: [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples JE, Breiman RF, Powers AM. Chikungunya fever: an epidemiological review of a re-emerging infectious disease. Clin Infect Dis [Internet] 2009;49(6):942–948. doi: 10.1086/605496. Sep 15Available from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tritsch SR, Encinales L, Pacheco N, Cadena A, Cure C, McMahon E, et al. Chronic Joint Pain 3 Years after Chikungunya Virus Infection Largely Characterized by Relapsing-remitting Symptoms. J Rheumatol [Internet] 2020;47(8):1267–1274. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.190162. Aug 1Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahid B, Ali A, Rafique S, Idrees M. Global expansion of chikungunya virus: mapping the 64-year history. Int J Infect Dis [Internet] 2017;58:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2017.03.006. MayAvailable from: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson H, Tritsch SR, Encinales L, Cadena A, Cure C, Ramirez AP, et al. Stiffness, pain, and joint counts in chronic chikungunya disease: relevance to disability and quality of life. Clin Rheumatol [Internet] 2020;39(5):1679–1686. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04919-1. MayAvailable from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Chikungunya [Internet]. [cited 2021 Mar 15] 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/chikungunya

- Yaseen HM, Simon F, Deparis X, Marimoutou C. Identification of initial severity determinants to predict arthritis after chikungunya infection in a cohort of French gendarmes. BMC Musculoskelet Disord [Internet] 2014;15:249. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-15-249. Jul 24Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.