Abstract

Objectives

Define the services available for the care of breast cancer at hospitals in the Eastern Region of Ghana, identify areas of the region with limited access to care through geospatial mapping, and test a novel survey instrument in anticipation of a nationwide scale up of the study.

Design

A cross-sectional, facility-based survey study.

Setting

This study was conducted at 33 of the 34 hospitals in the Eastern Region of Ghana from March 2020 to May 2020.

Participants

The 33 hospitals surveyed represented 97% of all hospitals in the region. This included private, government, quasi-government and faith-based organisation owned hospitals.

Results

Sixteen hospitals (82%) surveyed provided basic screening services, 11 (33%) provided pathological diagnosis and 3 (9%) provided those services in addition to basic surgical care.53%, 64% and 78% of the population lived within 10 km, 25 km and 45 km of screening, diagnostic and treatment services respectively. Limited chemotherapy was available at two hospitals (6%), endocrine therapy at one hospital (3%) and radiotherapy was not available. Twenty-nine hospitals (88%) employed a general practitioner and 13 (39%) employed a surgeon. Oncology specialists, pathology personnel and a plastic surgeon were only available in one hospital (3%) in the Eastern Region.

Conclusions

Although 16 hospitals (82%) provided screening, only half the population lived within reasonable distance of these services. Few hospitals offered diagnosis and surgical services, but 64% and 78% of the population lived within a reasonable distance of these hospitals. Geospatial analysis suggested two priorities to cost-effectively expand breast cancer services: (1) increase the number of health facilities providing screening services and (2) centralise basic imaging, pathological and surgical services at targeted hospitals.

Keywords: breast tumours, breast imaging, breast surgery, organisation of health services, surgical pathology

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study accomplished a comprehensive assessment of breast cancer care available at 33 out of 34 hospitals in the Eastern Region of Ghana.

Through geospatial analyses, areas of the region with limited access to services were identified and recommendations for expanding services with limited resources were able to be developed.

Our study only evaluated geographical access to care and did not address other significant barriers in accessing care including transportation challenges, financial barriers, patient factors, facility capacity thresholds and cultural factors.

Only hospitals were surveyed for this study, so other health facilities that may provide some limited breast cancer screening or care services were not captured in this study.

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death for women in Ghana, with 4482 cases and 2055 deaths attributed to breast cancer in 2020.1 Incidence of breast cancer is lower in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) compared with North America, but current estimates suggest the incidence is increasing.2 Outcomes vary widely across the continent, but 5-year survival is estimated to be around 35% for women in western SSA compared with the greater than 80% 5-year survival seen in high-income countries.3–5 Some early-stage breast cancers may be treated with surgery alone, but advanced disease requires complex multidisciplinary care. Given that 77% of black women in SSA have advanced disease (stage III or IV) at presentation,6 expanding services that allow for early diagnosis of breast cancer, improving access to basic diagnostic and surgical treatment, and developing sites with more comprehensive care should be prioritised. The Global Breast Cancer Initiative, launched by WHO in 2021, acknowledges these priorities to improve equitable access to breast cancer care across the globe.7

Ghana is a lower-middle-income country located in West Africa with 16 regions and a population of around 31 million.8–10 The gross national income per capita is US$2230, which ranks 147th out of 194 countries with data reported by The World Bank.9 11 Around half of Ghanaians pay for their healthcare out of pocket despite the presence of the National Health Insurance Scheme, which only 38% of the population is enrolled in.12 13 Management of breast cancer in Ghana is guided by The Ministry of Health’s (MOH) ‘Standard Treatment Guidelines.’ These guidelines recommend clinical breast examination (CBE) every 3 years for women younger than 40 years old and annually after the age of 40. Mammography is also recommended every 2 years for women 40 years and older. The remainder of the guidelines are broad and emphasise the need for personalisation of treatment based on patient and tumour factors. Surgery, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, radiotherapy, hormonal therapy and palliative care are all listed as treatment options that should be considered.14 There are no formal specifications detailing what different health facilities should provide in regards to breast cancer care, but the most comprehensive care is expected at tertiary teaching hospitals, followed by regional hospitals, municipal hospitals, then district hospitals.15

In 2011, Ghana’s MOH published the ‘National Strategy for Cancer Control in Ghana 2012–2016.’ This document outlines goals to improve early diagnosis of breast cancer through breast awareness, breast self-examination and CBE. It also details targets for the expansion of cancer related equipment, infrastructure and services at the various levels of health facilities across the country.16 In this study, we aimed to delineate the current resources available for breast cancer care in the Eastern Region of Ghana and map these services to identify populations without geographical access to care. In addition, we aimed to test the survey instrument and administration process in anticipation of a nationwide scale up of this study. The MOH can use the information obtained from this project to evaluate progress towards the stated targets in their National Strategy and help direct resource implementation to improve access to care.

Methods

Study design and setting

A cross-sectional, facility-based survey was performed from March 2020 to May 2020 in Ghana’s Eastern Region. This region was chosen for the pilot because the senior principal investigator (PI) for the project and our partners in the Ghana Health Service (GHS) live and work in the region. This provided our team with familiarity of the region and ensured the research assistants (RAs) would be geographically close to the senior PI if questions or concerns arose. The Eastern Region covers 8% of Ghana’s landmass, is home to almost 3 million people, and is about 55% rural.17

Inclusion criteria

Targeted facilities included all hospitals in the region because hospitals are expected to provide the majority of care for breast cancer. Lists of hospitals in the region were obtained from databases of the Health Facilities Regulatory Agency (HeFRA) and from the GHS. A total of 34 hospitals were identified, and 33 agreed to participate.

Exclusion criteria

Health facilities that were not designated as hospitals by HeFRA and GHS were not included in this study. Health facilities not surveyed included: community-based health planning and services (facilities), health centres, clinics and polyclinics.

Survey design

The objective of the survey was to provide an assessment of a hospital’s capacity to provide breast cancer care. The general framework for the survey was based on the WHO’s Situational Analysis Tool for assessing emergency and essential surgical care and the Surgeons OverSeas Personnel, Infrastructure, Procedure, Equipment, and Supplies (PIPES) tool for assessing surgical infrastructure.18 19 Experts in breast cancer surgery, oncology and global surgery reviewed the tool and made key modifications. The final version was developed through expert consensus and input from local and international partners. The data entry form used by RAs in the field and a guide with expanded information on each question is available in online supplemental file 1 (please note the full survey also included assessment of cervical cancer services which is not reported in this article).

bmjopen-2021-051122supp001.pdf (177.3KB, pdf)

Survey structure

General information collected about each hospital included address, Global Positioning System (GPS) coordinates, facility type and ownership. Additional sections identifying the nature and quantity of personnel, imaging services, screening and diagnostic capacity, procedure and treatment options, surveillance and follow-up were also queried. Respondents were asked if a service is available at their facility (yes/no). ‘Yes’ responses were specified as being always available (defined as greater than 80% of the time) or not always available. A subsurvey with additional questions about mammograms including number performed per month, patient cost and who reviews the imaging was completed if a facility reported having a mammogram machine.

The personnel section surveyed how many healthcare providers involved with breast cancer care were employed at each hospital. Medical doctors (MDs) included general medical practitioners, general and plastic surgeons, obstetricians and gynaecologists (ob/gyns) as well as radiology, pathology, oncology and radiation oncology specialists and consultants. Ob/gyns were included in the survey because they often perform CBE. Non-MD trained providers included radiology and pathology technicians, physician assistants (PAs) and social workers. Social workers were included because they are often involved with palliative care and patient counselling.

Survey administration

Four RAs familiar with the local geography were recruited via The Ensign College of Public Health (ECOPH) in Kpong, Ghana, located in the Eastern Region. The RAs participated in a week-long training course based at ECOPH. Training included didactic and field work components. The didactic portion detailed the study purpose and design and included an introductory clinical course on breast cancer and oncology basics. The field work component included proctored visits to local hospitals with gradually increased autonomy with survey administration. To promote consistency of the survey administration methods, all four RAs participated together in the initial portions of the study prior to travelling to their individually designated areas within the Eastern Region.

Both paper and electronic copies of the survey were distributed to all hospital directors prior to site visits by the RAs. The survey was administered through a structured interview with key administrative personnel, the most knowledgeable clinical specialist (eg, medical director, hospital superintendent) of each facility, or the lead breast cancer specialist. If a question was encountered that the respondent did not know, the appropriate person within the hospital was contacted. The RA returned to the hospital for follow-up of any missing questions after the respondent had acquired the necessary information. The in-person survey administration and follow-up of missing sections contributed to complete survey responses by all participating hospitals.

Hospital stratification

In order to present the data in a meaningful manner, we developed a system to stratify hospitals based on the services they provided. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network’s (NCCN) Framework for Resource Stratification of NCCN guidelines consists of three tiers: ‘basic,’ ‘core’ and ‘enhanced.’ These tiers are intended to provide guidelines for appropriate care in a resource-limited environment.20 Although these guidelines were not developed as a stratification system, their tiered structure provides an intuitive way to describe care available at each hospital. The three sets of guidelines for Invasive Breast Cancer and for Breast Cancer Screening and Diagnosis were closely reviewed by our researchers, and the services necessary to provide the care detailed in each guideline were listed and used as the basis for the stratification system (table 1).21–26 In order for a hospital to be categorised as a specific level, they needed to offer all services for that level. In addition, the hospital had to offer the service greater than 80% of the time throughout the year, except as specified in level 4.

Table 1.

Hospital stratification

Level 1 (NCCN enhanced) screening and clinical diagnosis

|

Level 2 (NCCN Core) screening and clinical diagnosis

|

Level 4 screening and clinical diagnosis

|

Pathological confirmation and imaging

|

Pathological confirmation and imaging

Surgical treatment

|

Pathological confirmation and imaging

Surgical treatment

|

Surgical treatment

|

Non-surgical treatment

|

|

Level 3 (NCCN basic) screening and clinical diagnosis

|

Level 5 Screening and clinical diagnosis

|

|

Non-surgical treatment

|

Pathological confirmation and imaging

Surgical treatment

|

Pathological confirmation and imaging

|

Level 6 screening and clinical diagnosis

| ||

Non-surgical treatment

|

Detailed list of services required to be categorised under each hospital level. A hospital must have all listed services to be categorised under a specific level. These services must be available >80% of the time throughout the year unless otherwise specified. Level 6 represents a hospital with the fewest breast cancer services.

*’Sometimes available’ includes hospitals that reported offering a service, but it is only available <80% of the time throughout the year.

ER, oestrogen receptor; HER2, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; NCCN, National Comprehensive Cancer Network; PR, progesterone receptor.

We renamed the levels that reflect the NCCN ‘basic,’ ‘core’ and ‘enhanced’ guidelines as level 3, 2 and 1, respectively. The resources required to provide guideline-concordant care in a ‘basic’ or level 3 hospital, were more extensive than what was available in the Eastern Region of Ghana. Thus, to better differentiate hospitals that offer limited services, we developed three additional levels: level 6 is defined as hospitals that provided basic screening and clinical diagnosis, level 5 hospitals provided screening, clinical diagnosis and pathological diagnosis and level 4 hospitals provided screening, clinical and pathological diagnosis and basic surgical services table 1. Hospitals that did not fulfil criteria for any of the levels were labelled as ‘other’. The ‘other’ category included hospitals that perform no breast cancer care as well as hospitals that offered some services, but were missing important components of breast cancer care (eg, a hospital that had an ultrasound and X-ray machine, but did not perform CBE).

Mapping of available services

Geographical information systems (GIS) technology was employed to derive the proximity of service availability and proportion of the population within a specified distance of key services. Each hospital location was geospatially visualised using Esri ArcGIS Pro software (2020 Ve.2.6) and proximity buffers extending outward in 5 km increments were generated. A 2018 LandScan population density raster from the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Oak Ridge, Tennessee, USA), which depicts the dispersal of individuals throughout the region was used, and a zonal statistics tool was deployed to obtain population numbers contained within each of the 5 km proximity buffers. The results of the spatial analysis returned values for populations within each of the specified distances while presenting a visual representation of the data.

Hypothetical targeted resource allocation

To observe the impact of a hypothetical targeted resource allocation, an additional spatial and population analysis was performed. The goal of this analysis was to evaluate access to breast cancer care after a modest addition of services at targeted hospitals. This hypothetical targeted resource allocation included two conditions aimed at modelling cost-effective expansion of care: (1) All hospitals were modelled to provide CBE. Under this assumption all hospitals are at least level 6. (2) Hospitals that were missing only a single service in order to increase their level within the stratification system were modelled as if they provided that service. For example, a level 6 hospital that only required the addition of ultrasound services in order to be categorised as level 5 was modelled as a level 5 hospital.

Reasonable travel distance

For the spatial and population analyses, reasonable travel distances were established as 10 km, 25 km and 45 km for screening, pathological diagnosis and surgical care, respectively. The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery describes access for essential surgery as being within 2 hours of a facility performing care.27 Given the numerous aspects of cancer care however, this threshold is not easily transferable, and there are no established thresholds that describe geographical access to cancer care. A Ghanaian study found that patients greater than 10 km from a health facility were less likely to use laboratory screening services, so 10 km was established as our screening threshold.28 In South Africa, women who lived greater than 20 km from a diagnostic hospital were more likely to have advanced disease at time of breast cancer diagnosis, so we established 25 km as our diagnosis threshold.29 For surgical management, we established 45 km as our distance threshold to keep travel time typically less than 1 hour. This is based on a Ghanaian study that found greater than 80% of respondents reported they would rarely or irregularly use available health services if travel time was 1 hour or greater.30

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics are presented as frequency and percentages. The hospital that was not surveyed was removed from the dataset and analysis was only run on the 33 hospitals with completed surveys. Analysis was performed using R software version V.3.6.2 (R Core Team, 2019).

Patient and public involvement

The GHS through the Eastern Regional Health Directorate has been involved with the entirety of this study from the development of the study concept through implementation. Results were presented to the GHS’s Eastern Regional leadership, including a discussion of recommendations. These officials directly represent the public. Patients were not involved in this study.

Results

Thirty-three out of the 34 hospitals (97%) in the Eastern Region were surveyed. The single hospital not surveyed was due to lack of response. Surveyed hospitals included 1 regional hospital, 1 municipal hospital, 20 district hospitals and 11 hospitals with no special designation. Sixteen of the hospitals were owned by the state, nine were privately owned, six were owned by faith-based organisations and two were quasi-government (hospitals with partial funding from the government).

A total of 350 healthcare workers involved with breast cancer care were reported across the 33 hospitals. Of these healthcare workers, 182 (56.2%) were MDs and 32 (97.0%) of the hospitals employed at least 1 MD. The 182 MDs included 130 (71.4%) general practitioners without a specialty, 20 (11.0%) general surgeons, 24 (13.2%) ob/gyns, 3 (1.6%) radiology specialists, 2 (1.1%) oncology specialists, 1 (0.5%) pathology specialist, 1 (0.5%) pathology consultant and 1 (0.5%) plastic surgeon. General practitioners were employed at 29 (87.9%) hospitals, general surgeons at 13 (39.4%) hospitals and ob/gyns at 17 (51.5%). The second largest group of healthcare workers were PAs with a total of 112 in the region across 32 (97.0%) hospitals. Twenty-seven radiology technicians, 3 pathology technicians and 26 social workers were also reported in the surveys. The 30 total radiology personnel (27 technicians and 3 specialists) were employed at 14 (42.4%) hospitals and the 5 pathology personnel (3 technicians, 1 specialist and 1 consultant) were all employed by the same hospital.

Breast cancer screening was mainly performed via CBE, and this was always available at 27 (81.8%) of the hospitals. None of the surveyed facilities had a mammogram machine. Ultrasound was available in 25 (75%) facilities, and X-ray machines were available in 19 (57%) facilities. One hospital (3.0%) had a CT scanner, while MRI machines and PET scans were not available in the region.

For the pathological diagnosis of breast cancer, excisional biopsy was offered at 18 hospitals (54.5%). Five of these sites also performed fine needle aspiration and core needle biopsy and one additional hospital offered core needle biopsy only. Thirty (90.9%) hospitals used an external lab for pathology, and seven (21.2%) of these also had in house pathology services. Two (6.1%) hospitals used in house pathology services only. Only one (3.0%) hospital in the region had the capacity to perform immunohistochemistry to test for oestrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status.

Thirteen hospitals (39.4%) provided surgery for the treatment of breast cancer. Six of these hospitals reported performing both mastectomy and wide local excision, and the other seven provided wide local excision only. Four of the hospitals that performed both mastectomy and wide local excision also performed axillary surgery, but no facilities performed sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Two hospitals (6.1%) offered chemotherapy for breast cancer. One of them offered cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and fluorouracil and the other provided cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and fluorouracil chemotherapy. One of these hospitals (3.0%) offered endocrine therapy with tamoxifen. Radiotherapy was not available in any of the surveyed hospitals. Palliative care was available at 10 hospitals (30.3%).

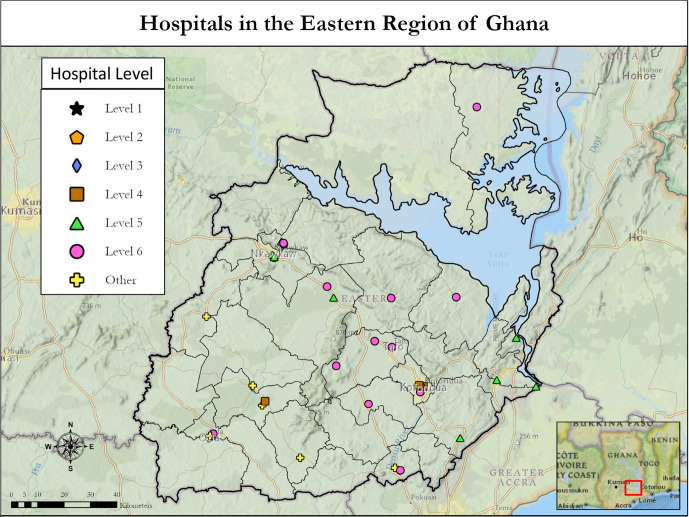

When the hospital level stratification was applied, 3 hospitals were classified as level 4, 8 were categorised as level 5 and 16 were classified as level 6 (figure 1 and table 2). The regional hospital, which is the main referral centre in the region was categorised as level 4, but the municipal hospital was categorised as other (table 2). No facilities in the Eastern region could provide the full spectrum of care detailed in the NCCN Framework for Resource stratification (levels 1, 2 and 3). The three facilities that offered the most breast cancer services required the addition of mammogram, endocrine therapy and testing for ER/PR status in order to provide level 3 (NCCN basic) care.21

Figure 1.

Map depicting the stratification level and location of hospitals in the Eastern Region of Ghana. Black lines depict borders for districts within the Eastern Region.

Table 2.

Number of hospitals by level at the time of survey and after hypothetical targeted resource allocation

| Hospital level | No of hospitals at time of survey | No of hospitals after hypothetical targeted resource allocation |

| Level 1 (NCCN enhanced) | 0 | 0 |

| Level 2 (NCCN core) | 0 | 0 |

| Level 3 (NCCN basic) | 0 | 0 |

| Level 4 (screening+path + surgery) | 3 | 6 |

| Hospital type | 1 regional, 2 district | 1 regional, 5 district |

| Hospital ownership | 1 government, 2 CHAG | 3 government, 2 CHAG, 1 quasi-gov |

| Level 5 (screening +path) | 8 | 9 |

| Hospital type | 5 district, 3 general | 5 district, 4 general |

| Hospital ownership | 3 govt, 1 CHAG, 1 quasi-govt, 3 private | 4 govt, 1 CHAG, 4 private |

| Level 6 (screening) | 16 | 18 |

| Hospital type | 10 district, 6 general | 10 district, 1 municipal, 7 general |

| Hospital ownership | 8 govt, 3 CHAG, 5 private | 9 govt, 3 CHAG, 1 quasi-govt, 5 private |

| Other | 6 | 0 |

| Hospital type | 3 district, 1 municipal, 2 general | |

| Hospital ownership | 4 govt, 1 quasi-govt, 1 private | |

| No of hospitals in each level at the time of survey and after hypothetical targeted resource allocation. The hypothetical targeted resource allocation included the following two conditions:

| ||

CBE, clinical breast examination; CHAG, Christian Health Association of Ghana, hospital with no special designation (general), quasi-government (quasi-govt); govt, government.

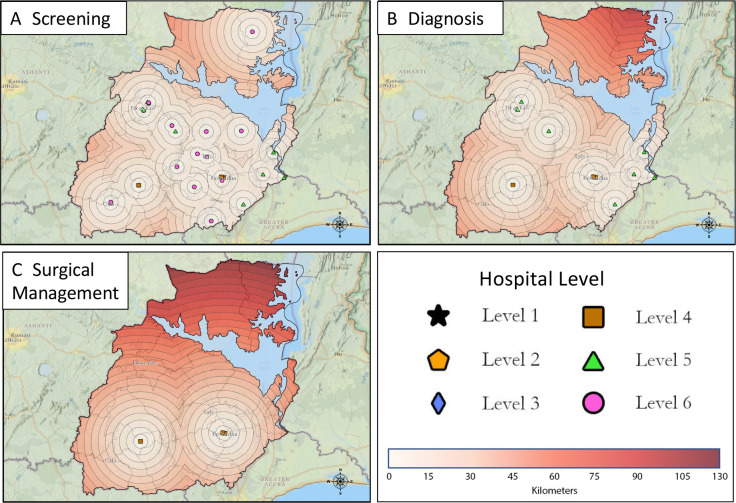

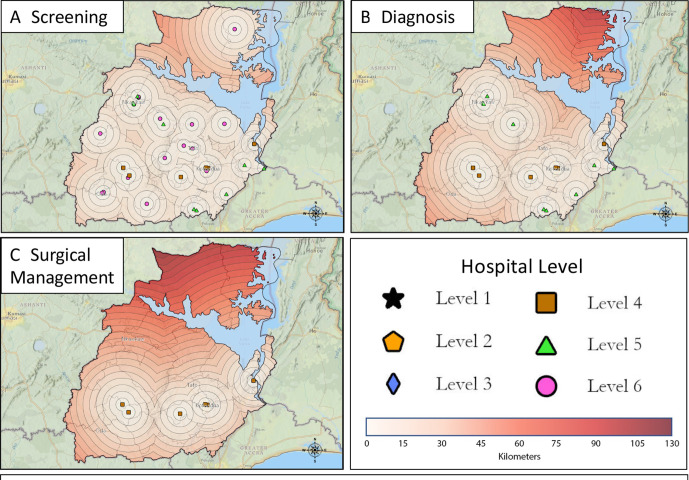

The spatial analysis using LandScan population data found that 52% of the population in the Eastern Region lived within 10 km of a hospital that provided breast cancer screening with CBE (figure 2A), 64% of the population lived within 25 km of pathological diagnosis services (figure 2B), and 78% of the population lived within 45 km of basic surgical care (figure 2C). Assessment of the hypothetical targeted resource allocation previously detailed was then performed. Implementing the first condition of the hypothetical resource allocation, modelling all hospitals to provide CBE, increased the population living within 10 km of basic screening from 52% to 60% (figure 3A). This model impacted six hospitals that reported they did not perform or only sometimes performed CBE. Four of these hospitals would be upgraded to a level 6, one would be upgraded to level 5 and one would be upgraded to level 4 with the addition of CBE only. For the second condition of the hypothetical resource allocation, one hospital was identified that required the addition of an ultrasound machine to be upgraded to level 5 and two hospitals could be upgraded to level 4 with the addition of an X-ray machine and breast biopsy, respectively (table 2). If these services were added, the proportion of the population in the Eastern Region within 25 km of a hospital that provided both screening and pathological diagnostic services would increase to 74% (from 64%) (figure 3B). The population within 45 km of a hospital that provided screening, pathological diagnosis, and basic surgical care would increase to 81% (from 78%) (figure 3C).

Figure 2.

Proximity maps depicting the stratification level and location of hospitals in the Eastern Region of Ghana. Each concentric circle depicts a 5 km distance from the corresponding Hospital. (A) hospitals providing screening services (levels 1–6). (B) hospitals providing diagnostic services (levels 1–5). (C) hospitals providing surgical management (levels 1–4).

Figure 3.

Proximity maps depicting the stratification level and location of hospitals in the Eastern Region of Ghana after hypothetical targeted resource allocation. Each concentric circle depicts a 5 km distance from the corresponding Hospital. (A) hospitals hypothetically providing screening services (levels 1–6). (B) hospitals hypothetically providing diagnostic services (levels 1–5). (C) hospitals hypothetically providing surgical management (levels 1–4).

Discussion

WHO provides a stepwise framework to guide the development of a National Cancer Control Programme. The first step involves an in-depth situational analysis to identify where gaps in care exist.31 Breast cancer is the most common cancer in Ghana,1 and its incidence is increasing across SSA,2 32 so analysing breast cancer services and access to care is increasingly important. While enumerating various services might be straightforward, measuring true access is complex. Existing frameworks to measure access to care recognise numerous factors as important including socio-cultural, demographic, geographical, psychological and organisational factors.33 Previous research in Ghana has identified many patient level factors including lack of knowledge about the disease, fear of treatment, financial concerns, religious and social factors, and preference for care from traditional healers as reasons for delays in accessing care or incomplete treatment.34–36 In contrast, system level and geographical factors have not been well studied. In addition, since publication of the ‘National Strategy for Cancer Control in Ghana: 2012–2016,’ which outlined goals for equipment and infrastructure at various hospitals, no follow-up studies have been conducted.16 Our survey of 33 hospitals provides a detailed situational analysis of personnel and services available for breast cancer care in the Eastern Region of Ghana.

Geographical considerations in access to care are a key element in describing capacity. Several recent studies have demonstrated the impact that distance from care has on breast cancer presentation in SSA. The African Breast Cancer Disparities in Outcomes Cohort Study identified that distance to a diagnostic health facility was independently associated with a delay in diagnosis of greater than 3 months and late diagnosis (stage III/IV) for women with breast cancer in Namibia, Uganda and Zambia.37 In Ethiopia, rural residence and a distance greater than 5 km from a cancer referral centre were associated with a delay greater than 3 months between onset of symptoms and medical consultation.38 Lastly, a diagnostic hospital in South Africa identified that their patients who lived farther from the hospital were more likely to have late stage (stage III/IV) breast cancer at time of diagnosis.29 By including spatial analyses, we are able to geographically describe service availability, identify areas most in need of enhanced care, and quantify the impact that various capacity improvements can have on population level access.

The first step of the care pathway for breast cancer involves screening and early clinical diagnosis, which the WHO describes as the ‘cornerstone of breast cancer control’ owing to the impact that stage at diagnosis has on outcomes.39 This is illustrated in a 2016 study of over 1000 Ghanaian women with breast cancer, which found cumulative 5-year survival rates of 91.94%, 59.93%, 33.95% and 15.09% for stage 0 and I, II, III and IV disease, respectively.40 In our survey, we identified that no hospitals offered mammography. CBE was offered at 82% of the surveyed hospitals, but only about 50% of the population in the Eastern Region lived within 10 km of a level 4, 5 or 6 hospital. If all hospitals started offering CBE, still only 60% of the population would be within 10 km of care. Given the limited access to screening and the fact that the majority of women in SSA present with late-stage disease,6 guidance from the Breast Health Global Initiative suggests a focus on expansion of early detection services with CBE, rather than screening programmes with mammography, should be prioritised.41 Availability of CBE at non-hospital community level health facilities, which are more abundant and widespread than hospitals, is critical to expand services to reach a greater proportion of the population.

The next step of care is pathological diagnosis. There are few publications about access to pathology services in Ghana. Estimates from a survey conducted by the International Academy of Pathology demonstrated limited access to pathology services in Ghana with only 30 pathologists in the entire country (1.1 per million population).42 Our study reiterated the sparse availability of pathology services in Ghana with only one-third of hospitals meeting requirements for a level 4 or five designation. We have identified a few hospitals offering in-house or send out pathology services and with GIS analysis found that 64% of the population in the Eastern Region lived within 25 km of a level 4 or 5 hospital. Nine hospitals reported always or sometimes offering in-house pathological review of breast biopsies, but only one of these hospitals employed formally trained pathology personnel. In addition, none of the facilities which offered in-house services tested for ER, PR or HER2 status, which is crucial in guiding appropriate therapies for breast cancer.43 Many hospitals surveyed send pathology to other laboratories for evaluation, but this also has limitations. Wait times of 2 weeks to 1 month for results were most frequently reported. Only one hospital used an outside laboratory that performs ER/PR and HER2 testing. Development of surgical pathology services is time consuming and requires significant investment in equipment and education as demonstrated by the decade-long effort to develop pathology services at a teaching hospital in Kumasi, Ghana.44 Because of this, further development of centralised pathology services with an emphasis on streamlining send out services should be prioritised as Ghana continues the long-term investment of increasing the pathology workforce.

The final step in breast cancer care, treatment, requires several medical specialties and treatment modalities. Four hospitals surveyed provided basic surgical care with mastectomy and axillary dissection and 2 hospitals offered mastectomy only. All of these hospitals and seven additional hospitals also offered wide local excision. Sentinel lymph node biopsy was not available in the region. Availability of non-surgical therapies were more restricted, with limited chemotherapy available at two hospitals, endocrine therapy at one hospital, and no radiotherapy services in the region. Although only three hospitals were categorised as level 4, representing that they performed screening, pathological diagnosis and basic surgical care, a large share of the population (78%) lived within 45 km of one of those facilities. Further study needs to be done in SSA and Ghana to evaluate ‘how far is too far’ in regards to cancer treatment accessibility, especially for services such as chemotherapy and radiation therapy that require extended periods of treatment with multiple trips to the hospital. Until that information is available, we believe that centralising care by expanding non-surgical services at hospitals already categorised as level 4 is a reasonable strategy to expand services. This would help to centralise care for patients in one hospital, potentially minimising travel-related barriers and expenses.

The complex and interdisciplinary nature of cancer care makes reporting results of a situational analysis challenging. Presentation of data in a concise and actionable manner for use by the MOH and NGOs is crucial. This study used the NCCN tiered guidelines as a starting point to define appropriate care across a spectrum of resource levels. The stratification made it easy to identify what resources should be added next to expand care at a single facility. When applying this stratification system to hospitals in the Eastern Region, we identified that no hospitals had the resources to provide the care outlined in the NCCN ‘basic’ guidelines for low-resource areas.21,24 The lack of mammography services prevented all hospitals in the region from providing full care concurrent with the ‘basic’ guidelines and lack of ER/PR testing was also a significant barrier.21–23 By defining three additional ‘levels,’ we were able to better describe the services available across the region. The GIS analysis added additional value to the survey results by determining the proportion of the population within a set distance from care. This analysis was used to evaluate the impact that potential resource allocation would have on the population, allowing for a more cost-effective and impactful expansion of care.

Limitations

There are a few limitations to address in this study. First, although it is modelled on PIPES and the WHO situational analysis tools, our novel survey tool has not been validated. The importance of expanding tools that enumerate surgical services lies in the multidisciplinary nature of cancer care, which extends well beyond surgical treatment. Second, this analysis only assessed geographical access to services using an Euclidean ‘straight line’ distance from care, rather than actual travel time. Our study did not evaluate other significant barriers to care including transportation challenges, financial barriers, patient factors such as breast cancer awareness, facility capacity thresholds, and cultural factors. This means that our population analysis likely overestimated the proportion of the population with access to breast cancer care. Additionally, because of these other barriers in access to care, the proposed hypothetical targeted resource allocation may not lead to improved access or utilisation of care if other factors are not addressed. Third, only hospitals were surveyed, so there may be non-hospital health facilities and local healthcare workers offering select services that were not captured by our assessment. Because of the limited availability of resources observed in the included hospitals, however, we believe it is unlikely these non-hospital facilities provide cancer services that would significantly change our estimations. In addition, one hospital declined to participate in the survey. This was a small hospital that was not expected to provide comprehensive breast cancer services. In addition, it is geographically close to other hospitals that were surveyed, so is unlikely to have impacted our population analysis. Fourth, many hospitals employed locum doctors who work at more than one hospital. This may have inflated the absolute numbers of providers reported, but does not impact the number of hospitals that employ specific providers. Lastly, as this study was confined to the Eastern Region, there may be facilities just beyond the borders in another region that provide care. This would skew the spatial analysis for areas along the border since individuals are able to access care in any region. We anticipate that the possibility of para-regional access will be more clearly elucidated in the ongoing nationwide expansion of this survey.

Conclusions

This study accomplished an in-depth situational analysis of available breast cancer care in the Eastern Region of Ghana using a novel facility-based survey tool. By stratifying each hospital and performing GIS analysis to identify areas most in need of services, the results of the survey can be used by the MOH to target cost-effective and guideline-concordant resource allocation to improve breast cancer care in Ghana. Based on the results of the study, we suggest two priorities in the Eastern Region: (1) expansion of screening and early diagnosis services with CBE by ensuring it is available at all hospitals, and leveraging providers at non-hospital health facilities to provide CBE and (2) centralisation of treatment (surgery, chemotherapy and radiotherapy services) to select hospitals to help streamline patient care until resources are available to expand services in more hospitals across the region.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Florence Dedey and Dr. Grace Ayensu-Danquah for their support throughout this project.

Footnotes

Twitter: @doc_mali

Contributors: All authors discussed the results of the project, critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version, this was the primary role for authors SM and KEB. In addition, the following authors had additional responsibilities: MM designed and organised the project, oversaw data collection, and wrote the manuscript with MEM and FL-V. MEM and FL-V analysed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript with MM. OS was involved with project design. AB-N and IO assisted with organisation and design of the project and provided local support. JS assisted with analysing the data, performed the geospatial analysis and created the maps. JN and AG assisted with organisation and management of the project. AK was the lead research assistant and helped to coordinate local data collection efforts. RRP and ES designed, organised and oversaw the entirety of the project and are senior investigators. ES is the guarantor of the study.

Funding: This study was supported by the University of Utah Center for Global Surgery with no specific grant or award number.

Map disclaimer: The inclusion of any map (including the depiction of any boundaries therein), or of any geographic or locational reference, does not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. Any such expression remains solely that of the relevant source and is not endorsed by BMJ. Maps are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data detailing services available at diagnostic centers and non-governmental organization health facilities as well as information on cervical cancer cervices provided at the surveyed hospitals is available and was not included in this manuscript. For inquiries regarding the data please contact Dr. Edward Sutherland at sutherlandmd@yahoo.com. For inquiries regarding the survey tool and possible use in another country, please contact sutherlandmd@yahoo.com or rayrprice@comcast.net.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of the Ghana Health Service, and was shared with the Regional Health Directorate of the Eastern Region. The protocol ID number is GHS-ERC 010/11/19.

References

- 1.The global cancer Observatory: Globocan 2020, Ghana, 2020. Available: https://gcoiarcfr/today/data/factsheets/populations/288-ghana-fact-sheetspdf

- 2.Adeloye D, Sowunmi OY, Jacobs W, et al. Estimating the incidence of breast cancer in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health 2018;8:010419. 10.7189/jogh.08.010419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allemani C, Matsuda T, Di Carlo V, et al. Global surveillance of trends in cancer survival 2000-14 (CONCORD-3): analysis of individual records for 37 513 025 patients diagnosed with one of 18 cancers from 322 population-based registries in 71 countries. Lancet 2018;391:1023–75. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33326-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCormack V, McKenzie F, Foerster M, et al. Breast cancer survival and survival gap apportionment in sub-Saharan Africa (ABC-DO): a prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 2020;8:e1203–12. 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30261-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ssentongo P, Lewcun JA, Candela X, et al. Regional, racial, gender, and tumor biology disparities in breast cancer survival rates in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2019;14:e0225039. 10.1371/journal.pone.0225039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jedy-Agba E, McCormack V, Adebamowo C, et al. Stage at diagnosis of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e923–35. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30259-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brunier A. New global breast cancer initiative highlights renewed commitment to improve survival. World Health Organization Departmental News, 8 March, 2021. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/08-03-2021-new-global-breast-cancer-initiative-highlights-renewed-commitment-to-improve-survival [Accessed 5 Sep 2021].

- 8.Ghana Health Service . Regions. Available: https://ghs.gov.gh [Accessed 7 Sep 2021].

- 9.World Bank, Ghana Country Profile . Data from: world development indicators database. Available: https://databank.worldbank.org/views/reports/reportwidget.aspx?Report_Name=CountryProfile&Id=b450fd57&tbar=y&dd=y&inf=n&zm=n&country=GHA [Accessed 5 Sep 2021].

- 10.Fleming, Sean. The World Bank’s 2020 country classifications explained, 2020. Available: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/08/world-bank-2020-classifications-low-high-income-countries/ [Accessed 20 Aug 2021].

- 11.World Bank, Gross national income per capita 2019, Atlas method and PPP . Data from: world development indicators database, 2021. Available: https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/GNIPC.pdf [Accessed 20 Aug 2021].

- 12.Saleh K. The health sector in Ghana: a comprehensive assessment, pg 6. Washington, DC: The World Bank, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.National Health Insurance Authority . Annual report. pg 5, 2013. Available: http://www.nhis.gov.gh/files/2013%20Annual%20Report-Final%20ver%2029.09.14.pdf

- 14.Ghana National Drugs Programme (GNDP) . Standard treatment guidelines: Ministry of health, seventh edition (7th), pgs 655-656, 2017. Available: https://www.moh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/GHANA-STG-2017-1.pdf [Accessed 1 Sep 2021].

- 15.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) . Health service provision in Ghana: assessing facility capacity and cots of care. Seattle, WA: IHME, 2015. Available: http://www.healthdata.org/sites/default/files/files/policy_report/2015/ABCE_Ghana_finalreport_Jan2015.pdf [Accessed 30 Aug 2021].

- 16.Ministry of Health, Ghana, National strategy for cancer control in Ghana 2012-2016, 2011. Available: https://www.iccp-portal.org/sites/default/files/plans/Cancer%20Plan%20Ghana%202012-2016.pdf

- 17.Eastern Regional Co-Ordinating Council . Eastern regional official website: profile of the eastern region, 2016. Available: http://www.easternregion.gov.gh/index.php/profile/

- 18.World Health Organization (WHO) . WHO global initiative for emergency and essential surgical care, 2019. Available: http://www.who.int/surgery/globalinitiative/en/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Surgeons overseas, SOS pipes surgical capacity assessment tool, 2017. Available: http://www.adamkushnermd.com/files/PIPES_tool_103111.pdf

- 20.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . NCCN framework for resource stratification of NCCN guidelines (NCCN FrameworkTM), 2021. Available: https://www.nccn.org/framework/default.aspx

- 21.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Invasive breast cancer: basic resources version 2.2017, 2018. Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_basic.pdf

- 22.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Invasive breast cancer: core resources version 2.2017, 2018. Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_core.pdf

- 23.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Invasive breast cancer: enhanced resources version 2.2017, 2018. Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast_enhanced.pdf

- 24.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Breast cancer screening and diagnosis: basic resources version 3.2018, 2018. Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening_basic.pdf

- 25.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Breast cancer screening and diagnosis: core resources version 3.2018, 2018. Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening_core.pdf

- 26.National Comprehensive Cancer Network . Breast cancer screening and diagnosis: enhanced resources version 3.2018, 2018. Available: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/breast-screening_enhanced.pdf

- 27.Meara JG, Greenberg SLM. The Lancet Commission on global surgery global surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare and economic development. Surgery 2015;157:834–5. 10.1016/j.surg.2015.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Der JB, Grint D, Narh CT, et al. Where are patients missed in the tuberculosis diagnostic cascade? A prospective cohort study in Ghana. PLoS One 2020;15:e0230604. 10.1371/journal.pone.0230604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dickens C, Joffe M, Jacobson J, et al. Stage at breast cancer diagnosis and distance from diagnostic hospital in a periurban setting: a South African public hospital case series of over 1,000 women. Int J Cancer 2014;135:2173–82. 10.1002/ijc.28861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buor D. Analysing the primacy of distance in the utilization of health services in the Ahafo-Ano South district, Ghana. Int J Health Plann Manage 2003;18:293–311. 10.1002/hpm.729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health organization (who), National cancer control programmes (NCCP), 2017. Available: http://www.who.int/cancer/nccp/en/

- 32.Joko-Fru WY, Jedy-Agba E, Korir A, et al. The evolving epidemic of breast cancer in sub-Saharan Africa: results from the African cancer registry network. Int J Cancer 2020;147:2131–41. 10.1002/ijc.33014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gurch Randhawa KR. Access to healthcare: issues of measure and method. Prim Health Care 2013;03. 10.4172/2167-1079.1000136 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obrist M, Osei-Bonsu E, Awuah B, et al. Factors related to incomplete treatment of breast cancer in Kumasi, Ghana. Breast 2014;23:821–8. 10.1016/j.breast.2014.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clegg-Lamptey J, Dakubo J, Attobra YN. Why do breast cancer patients report late or abscond during treatment in Ghana? A pilot study. Ghana Med J 2009;43:127–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agbokey F, Kudzawu E, Dzodzomenyo M, et al. Knowledge and health seeking behaviour of breast cancer patients in Ghana. Int J Breast Cancer 2019;2019:5239840 10.1155/2019/5239840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Togawa K, Anderson BO, Foerster M. Geospatial barriers to healthcare access for breast cancer diagnosis in sub-Saharan African settings: the African breast Cancer–Disparities in outcomes cohort study. Int J Cancer 2020:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tesfaw A, Demis S, Munye T, et al. Patient delay and contributing factors among breast cancer patients at two cancer referral centres in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. J Multidiscip Healthc 2020;13:1391–401. 10.2147/JMDH.S275157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization (WHO) . Breast cancer: prevention and control, 2016. Available: https://wwwwhoint/cancer/detection/breastcancer/en/

- 40.Mensah AC, Yarney J, Nokoe SK, et al. Survival outcomes of breast cancer in Ghana: an analysis of clinicopathological features. OAlib 2016;03:1–11. 10.4236/oalib.1102145 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ginsburg O, Yip C-H, Brooks A, et al. Breast cancer early detection: a phased approach to implementation. Cancer 2020;126 Suppl 10:2379–93. 10.1002/cncr.32887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.African Strategies for Advancing Pathology . IAP survey results summary: summary for Ghana, 2019. http://www.pathologyinafrica.org/surveydata/summary-data-country.php?id=020 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunt KK, Mittendorf EA. Diseases of the Breast. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, eds. Sabiston textbook of surgery: the biological basis of modern surgical practice. Elsevier/Saunders, 2017: 819–64. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stalsberg H, Adjei EK, Owusu-Afriyie O, et al. Sustainable development of pathology in sub-Saharan Africa: an example from Ghana. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017;141:1533–9. 10.5858/arpa.2016-0498-OA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2021-051122supp001.pdf (177.3KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Data detailing services available at diagnostic centers and non-governmental organization health facilities as well as information on cervical cancer cervices provided at the surveyed hospitals is available and was not included in this manuscript. For inquiries regarding the data please contact Dr. Edward Sutherland at sutherlandmd@yahoo.com. For inquiries regarding the survey tool and possible use in another country, please contact sutherlandmd@yahoo.com or rayrprice@comcast.net.