Abstract

In the United States, women are over-represented and Blacks are under-represented as living kidney donors. A traditional bioethics approach would state that as long as living donors believe that the benefits of participation outweigh the risks and harms (beneficence) and they give a voluntary and informed consent, then the demographics reflect a mere difference in preferences. Such an analysis, however, ignores the social, economic and cultural determinants as well as various forms of structural discrimination (e.g., racism, sexism) that may imply that the distribution is less voluntary than may appear initially. The distribution also raises justice concerns regarding the fair recruitment and selection of living donors. We examine the differences in living kidney donor demographics using a vulnerabilities analysis and argue that these gender and racial differences may not reflect mere preferences, but rather, serious justice concerns that need to be addressed at both the individual and systems level.

Keywords: Living donor, Justice, Vulnerability, Black, Race/ethnicity, Gender, Women

1. Introduction

The first successful kidney transplant was performed in 1954 between identical twin brothers, [1] and within the decade, a voluntary international registry of kidney transplantation of both living and deceased donors was established. The actual donor data reported were quite sparse.

Historically, who were the donors? The first report of the Human Kidney Transplant Registry, published in January 1964, described 244 donors, 68 (28%) of which were deceased donors. [2] Of the remaining 176 kidney grafts, the donor’s relationship to the recipients were: 49 parents (28%); 39 non-twin siblings (22%), 33 twin siblings (19%), 3 other blood relatives (2%) and 52 non-related individuals (30%). [2] Neither gender nor race of the donors was reported. In fact, donor race would never be reported by this registry. Full gender breakdown was not provided until the fifth report, published in July 1967. [3] Males were more likely to be living donors in all categories of donor/recipient relationships except for parent-to-child donations, but because of the high frequency of mother-child donations, women were the majority of living donors (~54%). [3]

In the 12th and penultimate report published in August 1975, deceased donors now accounted for 70% of all donors. [4] Among living donors, virtually all were first-degree relatives. Parents and siblings comprised 43% and 49% of all living donors respectively. [4] Again, neither gender nor race of the donors were reported.

In 1988, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS)/Organ Procurement and Organ Transplantation Network (OPTN) began the collection of systematic data on solid organ transplants in the United States (US). [5] In the first year of US systematic data collection, there were 5693 kidney donors of whom 1817 (32%) were living donors [5] (similar to the data reported voluntarily by centers in the US and abroad in 1975 [4]). The vast majority of the living donors were first-degree biological relatives: 513 (28%) were parents; 977 (54%) were siblings, including 1 identical twin and 5 half-siblings; and 158 (9%) were children. [5] Women accounted for 994 (55%) of all living donors and the racial/ethnic breakdown was: 1384 (76%) were White, 210 (12%) were Black; and 166 (9%) were Hispanic. [5]

In 2019, both the number and percentage of living kidney donors had increased. There were 18,014 kidney donors, 6862 (38%) of whom were living donors, most of whom were female (4472, 65%). [5] Most living donors were White (4848, 71%), with the percentage of Black (12%) and Hispanic donors (9%) unchanged from 1994. A major demographic change however had occurred over the 3 decades: Whereas 91% of all living donors in 1988 were first-degree biological relatives, in 2019 they only accounted for 32% of all living donors. [5] The percentage decrease in living donation by first-degree biological relatives was more pronounced in the White community than in the Black community.

Beginning March 2020, many living donor transplants were put on hold during the COVID-19 pandemic to avoid overtaxing hospitals that were inundated with COVID-19 patients and to avoid transmission of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. Only 5237 living kidney donations occurred, a drop of 23.7% from 2019. [5] The greatest percentage drop occurred among Black donors (from 598 to 372, a drop of 37.8%). The percentage of White living donors fell by 22.8% (from 4846 to 3739) and Hispanic living donors dropped 22.5% (from 999 to 774). [5] This led to a change in the racial/ethinic distribution of living donors. Whereas the percentage of White living donors modestly increased (from 70.6% in 2019 to 71.4% in 2020) and the percentage of Hispanics living donors more sharply increased (from 9% in 2019 to 14.7% in 2020), the percentage of Black living donors fell significantly (from 12.0% in 2019 to 7.1% in 2020). [5] It remains to be seen whether these data represent a change in demographics or a one-time secondary effect of the pandemic.

In this manuscript we examine the demographics of living donors. While deceased donor organs are a public good and are allocated using a transplant algorithm developed with broad stakeholder input, living donor grafts are a private resource and are allocated according to donor wishes. Most living donors who donate directly, donate to a candidate of the same race and socioeconomic status (SES), [6] such that the benefits of living donor transplantation are not evenly distributed across the kidney transplant candidate pool. [7,8] Specifically, we examine two demographic traits of living donors: the over-representation of women and the under-representation of Blacks.

A traditional bioethics approach would state that as long as living donors believe that the benefits of participation outweigh the risks and harms (beneficence) and they give a voluntary and informed consent (autonomy, or more accurately, respect for persons) free from undue influence, then the demographics reflect a mere difference in preferences. Such an analysis, however, ignores the social, economic and cultural determinants as well as various forms of structural discrimination (e.g., racism, sexism) that may imply that the distribution is less voluntary than may appear initially. The distribution also raises justice concerns regarding the fair recruitment and selection of living donors and their recipients. The justice concerns are asymmetrical since women are over-represented and Blacks (especially Black men) are under-represented.

So should gender and racial differences in living donation be considered a disparity or a preference? We examine the demographics of living donors using the vulnerability analysis we described previously as part of a five-principle living donor ethics framework. [9] Our vulnerabilities taxonomy is based on the work of Kenneth Kipnis who explored the different types of vulnerabilities that research participants may experience. [10,11] We have modified this taxonomy to apply to living donors (see Table 1). [12] We show how the multiple vulnerabilities that an individual experiences can help explain why women tend to be over-represented as donors (and under-represented as recipients), and why Blacks tend to be under-represented as living donors (and as living donor recipients). As such, our vulnerabilities analyses help clarify why these differences may not reflect mere preferences but rather more serious justice concerns.

Table 1.

Eight Vulnerabilities of Potential Living Donors.

| Trait | Living donor transplantation |

|---|---|

| Capacitational (aka Cognitive) | Does the potential living donor have the capacity to deliberate about and decide whether or not to participate as a living donor? |

| Juridic | Is the potential living donor liable to the authority of others who may have an independent interest in that donation? |

| Deferential | Is the potential living donor given to patterns of deferential behavior that may mask an underlying unwillingness to participate? |

| Social | Does the potential living donor belong to a group whose rights and interests have been socially disvalued? |

| Medical | Has the potential living donor been selected, in part, because of the presence of a serious health-related condition in the intended recipient for which there are only less satisfactory alternative remedies? |

| Situational | Is the potential living donor in a situation in which medical exigency of the intended recipient prevents the education and deliberation needed by the potential living donor to decide whether to participate as a living donor? |

| Allocational | Is the potential living donor lacking in subjectively important social goods that will be provided as a consequence of participation as a donor? |

| Infrastructural | Does the political, organizational, economic, and social context of the donor care setting possess the integrity and resources needed to manage living donation process and follow-up? |

This table is modified from Lainie Friedman Ross and J. Richard Thistlethwaite, “The Prisoner as Living Organ Donor,” Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics 27, no. 1 (2018): 93–108, at 97. Reprinted with permission from Cambridge University Press.

2. Gender demographics 1956 -present

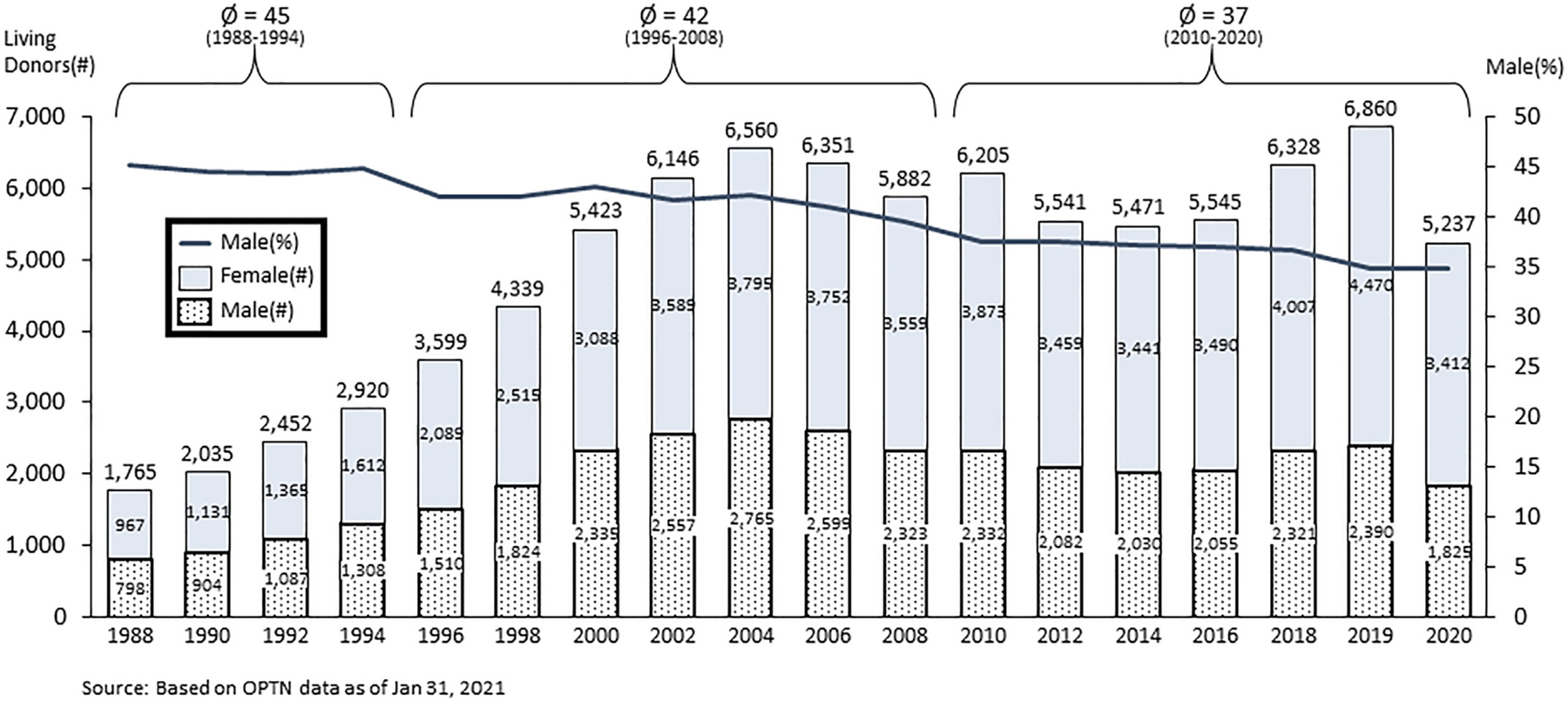

The limited gender data from the Human Transplant Kidney Registry (1963–1976) showed a slight predominance of women to men donors (54%–46%). In 1988, when UNOS/OPTN began to collect living donor data, the ratio of female-to-male living donors was 55%:45%, although in the past 5 years men now comprise less than 40% of all living kidney donors. [5] The over-representation of female living donors over the past 30 years is not unique to the US. In all countries except Iran, women account for over 50% of living donors. [13]

Also noteworthy is that both women and men are more likely to be a living kidney donor to a male recipient. While part of this can be explained by the fact that men are more likely to have end-stage renal disease (ESRD), [14] there are data at all time points and in virtually all countries that women have reduced or delayed access compared to men throughout the process—from donor education and evaluation to undergoing transplantation, in both living and deceased donor kidney transplantation. [15] As Melk and colleagues explain:

Potential reasons for reduced or delayed access to transplantation for women versus men have been described for all steps of the transplantation process, including a lower probability of discussing transplantation as a treatment option with women, fewer women completing the clinical workup needed for transplantation, and sex discrimination in waitlisting. Physicians may assess a woman’s health differently [[15] at p. 1097, references omitted].

A striking example of gender difference in access to transplant is the female-to-male ratio of spousal donors. When Terasaki and colleagues published their data to support non-biological relatives as living donors in 1995, they reported on 360 spousal donations of which 261 (72.5%) were wife-to-husband grafts and 99 (27.5%) were husband-to-wife grafts. [16] In 2019, the data are the same: of the 866 spousal and life partner living kidney donations, 229 (26%) were donations by men and 637 (74%) from women. [5] Some of the discordance may be due to the fact that men are more likely to develop ESRD, and/or that fewer men can donate to their spouses because of increased sensitization secondary to pregnancy. Others have postulated that the lower participation of men as living donors is that they are more frequently “excluded as donors as they are more likely to exhibit symptoms of hypertension and ischemic heart disease than their female counterparts.” [[17] at p. 474]

The lower participation of men may also be due to familial financial issues that are based on who works outside the home, who can afford to take time off from work, as well as the social value placed on men compared to women. In 1963, women who worked full-time, year-round made 59 cents on average for every dollar earned by men which improved to 77 cents in 2010 and close to 80 cents to the men’s dollar in 2018. [18] Recently, given the large number of households in which both spouses work, Frech et al. discussed the need for transplant teams to examine more closely kidney donation between couples:

Our findings suggest that transplant teams should consider household responsibilities and gender roles and should work with donor-recipient couples to identify the required social and economic support during recovery, as well as facilitating paid employment among couples facing the unique challenges of spousal kidney donation. [[19] at p. 888].

3. Race/ethnicity demographics 1950s-present

There are no race/ethnicity demographics of donors in the Human Transplant Registry Reports that included data voluntarily provided from centers in the US and internationally from 1963 to 1977. In fact, race data are not provided until the 13th and final report, when it was reported that Blacks represented 12% of the recipients. [20] Although the Report only discusses the race of the recipients, one can assume that donor-recipient race are concordant: Data between 1995 and 2009 found that 95% of white living kidney donors gave to white recipients and 96% of black living kidney donors gave to black recipients. [6]

Data from the UNOS/OPTN registry shows an increasing number of living donors of all race/ethnicities from 1988 to 2004 when it begins to fall (See Fig. 1). This decrease in living donors continues for a decade (until 2014), varying across gender and race/ethnicity with greater percentage drop in males (see Fig. 1) and in Blacks (see Fig. 2). In the past 3 decades, Black living donors account for ~12.7% of all living donors, slightly less than their percentage in the overall US population (13.4%), [21] but under-represented given their community’s need (Blacks constitute 31.9% of the kidney waitlist). [5] The absolute number of Black living donors peaked in 2004 when there were 927 Black donors (425 male Black donors), but there have been less than 600 living Black donors annually since 2014. [5] Of note, in 2018 and 2019, there was a significant increase in total living donation in White, Black, Hispanic and Asian racial and ethnic groups, but in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a fall in all living donors in White, Black, Hispanic and Asian racial and ethnic groups. [5]

Fig. 1.

Gender of Living Kidney Donors 1998–2020. Legend: Left Y-axis is number of living donors; Right Y-axis is percent male; and X-axis is year. The columns represent the number of male and female living donors in even years between 1988 and 2020. Dotted bar = # of women and Gray bar = # of men; The black line depicts the percentage of male living donors over time.

Fig. 2.

Living Kidney Donors by Race/Ethnicity and Year. Legend: Y-axis is number of living donors; X-axis is year. The number of donors by race/ethnicity are depicted by different line colors and patterns: White = Light gray dashed line; Black = Black solid line; Hispanic = Dark gray dotted line; and Asian = Gray dotted line.

Let us see how these gender and racial/ethnic differences can be understood using a vulnerabilities analysis.

4. Women as living donors: a vulnerabilities analysis

The over-representation of women as living donors raises many vulnerabilities concerns. The first vulnerability listed in Table 1 focuses on capacitational vulnerability, “whether the potential living donor have the capacity to deliberate about and decide whether or not to participate as a living donor.” While some individuals may lack the capacity to participate due to cognitive impairment, young age, or immaturity, in general, adult women and men are presumed to have decisional capacity. As such, capacitational vulnerability does not help explain the gender discrepancy.

The next two vulnerability traits are juridic and deferential vulnerabilities which refer to formal (juridic) and informal (deferential) power inequities in relationships that may lead to undue pressure to donate. In most US families, the vulnerability is better understood as deferential rather than juridic, and women may be more likely to be donors secondary to familial expectations that mothers, sisters and wives care for, and therefore donate kidneys to, their male counterparts. [22] In their early ground-breaking study, Simmons and colleagues found that women were more likely to perceive donation as an extension of their obligation to their family whereas men were more likely to express ambivalence. [23] This is despite the fact that women reported donation more stressful, although it is not clear if women donors were more stressed or were just more honest about feeling stressed, or received less emotional (and physical) support post-donation. [24]

Social vulnerability refers to whether the living donor belongs to a group whose interests have been socially disvalued. For example, when families negotiate intrafamilial donation, they may look to non-wage earners who have traditionally been women who provide unpaid in-home family caregiving responsibilities to other household members. In addition, as we noted previously:

It is also possible that the non-wage earners volunteer themselves, either because they view this as an opportunity to be an active contributor to the family’s resources or because they have internalized the view that they are of lower worth. [[9] at p. 3].

Even if both male and female family members are wage-earners, men often earn more than women, even when occupying the same role, [18] which may lead families to endorse women to be the donors.

Another factor that may explain the imbalance is gender-bias on the part of physicians or institutions. In 2002, Kayler wrote:

Although women may have cultural or attitudinal proclivities toward donation, it is the responsibility of the healthcare system to ensure that women experience neither active nor unintentional discrimination. [[25] at p. 252].

Medical:

This vulnerability focuses on whether the potential living donor has been selected, in part, because of the presence of a serious health-related condition in the intended recipient for which there are only less satisfactory alternative remedies? Clearly living donation is the best renal replacement treatment for most individuals with ESRD, and so all friends or relatives of an individual in ESRD face medical vulnerability because they may be asked to serve a living kidney donor.

There are medical arguments to support encouraging male donors. Gender concordant donor-recipient pairs (particularly male donor-male recipient pairs) have better outcomes than gender discordant donor-recipient pairs’ with the worst graft survival occurring with female donors to male recipients. [26,27] Thus, men in ESRD should be encouraged to find male living donors.

Situational:

Situational vulnerability refers to cases in which the medical exigency of the intended recipient prevents the education and deliberation needed by the potential living donor to decide whether to participate as a living donor. For kidney transplantation, because of the availability of dialysis, medical exigency of the intended donor is almost never an issue. The number of cases where adequate dialysis access cannot be established in an intended recipient who has a compatible, medically acceptable living donor are anecdotally rare, but possible. However, the number of cases is so small as to not be able to distinguish a difference in living donor gender distribution. For liver transplantation, the classic example is in the setting of acute liver failure (ALF). While recent data show that women are more likely to develop ALF than men and that women in ALF are more likely to be sicker when listed, the number of living liver transplants for ALF in the US is also too small to explain a gender difference. [28] In both situations, a vulnerabilities analysis must be incorporated into the time-constrained work-up, which the LDAT and potential donor must review and address. While the work-up is taking place, candidates can and should be waitlisted for a deceased donor transplant.

Allocational:

Is the potential living donor lacking in subjectively important social goods that will be provided as a consequence of participation as a donor? In many cultures where male dominance within the family is the norm, there can be a relative lack of self-esteem of female family members. Living donation may increase women’s self-esteem as their family members praise and or socially reward them for their donation. [22,23] Conversely, a female donor lacking in subjectively important social goods who seeks not only increased self-esteem but also the esteem and praise of others in the family may be disappointed if post-transplant attention of family members is focused on the recipient whom they regard as sick, while they still perceive the donor as a healthy individual.

Infrastructural:

Does the political, organizational, economic, and social context of the donor care setting possess the integrity and resources needed to manage living donation process and follow-up? Consider, first, economic vulnerability. After the economic recession in 2008, the number of living donors of both genders decreased suggesting economic infrastructural vulnerability of both men and women. However, the decline in living donation was most marked in men from lower income groups. [29] It is also important to note that financial barriers to donation are not limited to out of pocket expenses and lost wages, but also concerns that an interruption in employment or loss of employment may lead to loss of work-related benefits, including health insurance. [30,31]

A second concern is the need for both short- and long-term medical follow-up of donors to mitigate the short- and long-term medical risks that unilateral nephrectomy entails. [32,33] Our current system only guarantees living donors short-term follow-up related to the kidney procurement itself. Approximately 20% of donors lack health insurance, [34,35] exposing them to lack of long-term health care access. As women tend to utilize more health care services, lack of adequate insurance may be even more problematic for them. [36] Health literacy can further complicate understanding of the risks of living donation as well as in accessing needed care post-donation. However, women generally have slightly better health literacy than men, [37–39] so gender may mitigate some of the access concerns.

A particular health issue for women post-donation is that they are at increased risk of developing pregnancy complications including an increased risk of pre-eclampsia, premature birth, and low birth weight infants. [40,41] What impact post-donation pregnancy has on whether these women develop ESRD or other medical co-morbidities (e.g., hypertension, cardiac disease) later in life is unknown. [42]

In sum, while all donors have vulnerabilities, there are reasons to believe that women may experience greater deferential, social, and allocational vulnerabilities with respect to their relationship to their recipients and wider social circle (family) and these vulnerabilities may lead to their over-representation. They may also be more deferential to transplant teams and feel unable to say no. It is important for the living donor advocate (LDA) or the living donor advocate team (LDAT)— a required component of living donor transplant programs since 2007 [43]–ensure that the donation is voluntary and that women donors are not experiencing undue pressure.

However, it may be that women are donating at a rate consistent with their autonomous preferences and that the real problem is that men are under-represented. This may be voluntary due to greater ambivalence about donating which shifts the burden to women. Alternatively, it may be due to the social pressures and expectations of being the major bread winner which deprives men of the psychosocial benefits of serving as a living donor. Justice then would require attempts to promote donation among potential male donors: to remove barriers (such as out of pocket expenses and paid medical leave) and to promote more education about why donation is safe. Furthermore, explaining the benefits of gender concordance in graft outcomes may encourage male candidates with ESRD to preferentially seek out male donors both within and outside their family when more than one potential donor is available to a candidate. And yet, such programs should proceed with caution as it may be that male under-representation is appropriate since the medical data show that some male donors, particularly, young Black male donors, are at greater risk of ESRD post-donation than older donors and White donors. [44]

That women are more likely to be living donors is only part of the issue. As important is that they are less likely to be a living donor transplant recipient. [45] The reasons are multifactorial including cultural, social, economic and personal factors. It is from this more holistic perspective that the over-representation of women as living donors raises justice concerns.

5. Blacks as living donors: a vulnerabilities analysis

A vulnerabilities analysis also helps explain why Blacks are under-represented as living donors. However, before we undertake this analysis, several caveats should be enumerated.

First, Blacks donate kidneys comparable to their representation in the population. Of the 163,664 living donors listed on the UNOS website between 1988 and 2020, 19,169 (11.7%) are classified as Black, [5] and Blacks account for 13.4% of the US population. [21] Similarly, 115,335 (70.4%) of the living donors on the UNOS website are White, [5] and Whites account for 76.3% of the population. [21] However. of the 99,060 candidates on the UNOS deceased donor kidney waitlist, Blacks account for 31.9% (31,587) and Whites 35.2% (34,950) of the waitlist. [5] Since most living donors donate within their ethnic group, [6] Black candidates with ESRD are disadvantaged in receiving a living kidney donor compared to White candidates. [7,8] Purnell and colleagues showed that from 1995 to 2014, of the 453,162 first-time adult candidates on the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR), receipt of a kidney from a living donor within 2 years on the waiting list increased from 7.0% to 11.4% among White candidates and decreased from 3.4% to 2.9% among Blacks candidates. [46] That is, although Blacks donate at a similar rate as Whites, Black candidates are less likely to get a living donor transplant. More research is needed to understand whether this is driven by recipient factors (such as a reduced willingness to seek out potential donors), donor factors, or a combination of the two. Unfortunately, most of the available studies focus on recipient-related factors that contribute to decreased identification of potential living donors by ethnic minorities and less research on donor-related factors. [47,48]

Second, part of the under-representation of Black living donors may be due to greater health co-morbidities within the Black community, including obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, [49,50] making fewer Blacks eligible to be living donors such that candidates may be less likely to find medically acceptable living donors within their social networks. [48,51–53]

Third, the interplay between race and SES is complex, and efforts to understand the under-representation of Black living donors must account for these effect. [7,8,46,47] The data suggest that racial disparities in access to living donor transplantation may be more related to SES factors rather than to cultural differences. [47] Many of the obstacles attributed to living donation in the Black community may be more accurately attributed to lower SES rather than race/ethnicity. [47,48,54] A study by Gill found that the incidence of living kidney donation was lower in Blacks than Whites in the lowest income quintile (incidence rate ratio 0.84; 95% confidence interval, 0.78 to 0.90), but higher in Blacks in the three highest income quintiles. [7] Thus potential financial barriers for prospective Black donors are both their capacity to absorb the financial consequences of donation, and/or the limited capacity of their recipients to reimburse allowable expenses. [8]

Fourth, in the past decade, researchers have identified Apolipoprotein 1 (APOL1) as a gene endemic to parts of Africa where having one copy of identified allelic variants (39% of the US Black population) protects against African sleeping sickness. [55] Carrying 2 copies of these same APOL1 allelic variants. (12% of the US Black population), [55] however, increases the risk of developing renal failure, explaining much of the excess rate of ESRD in Blacks compared with Whites in the US. [55–58] Hence, these allelic variants have become commonly called APOL1 risk alleles. APOL1 also has significant implications for kidney transplantation. Deceased donor kidneys from Black donors with 2 APOL1 risk alleles have worse graft survival not only compared to kidneys from donors of other races, but also compared to Black donors with 0 or 1 risk allele; [59] however, the relative graft survival of living donor kidneys from Black living donors based on the number of donor APOL1 risk alleles is unknown. But more importantly for the purpose of this chapter, it is also unknown what impact the unilateral nephrectomy has on living donor clinical outcomes when combined with APOL1 risk alleles. Current data indicate that living donors are at low but increased risk of developing ESRD, [60,61] particularly young Black male donors. [60] What we don’t know is whether unilateral nephrectomy places the Black donor with 2 APOL1 risk alleles at greater risk than donors who have fewer than 2 APOL1 risk alleles. Given these uncertainties, how the data should impact the LDAT’s discussions with potential Black living donors is controversial. [62] Elsewhere, we have argued that the LDAT should discuss both what is known and what is unknown with respect to donor and recipient well-being. [62]

Now let us look at each vulnerability and examine whether they explain why Blacks are under-represented as living donors.

The first vulnerability is capacitational vulnerability. While individuals of all races and ethnicities may lack the capacity to participate due to cognitive impairment, young age, or immaturity, in general, adults are presumed to have decisional capacity such that this vulnerability does not appear to have a racial/ethnic proclivity.

Juridic and deferential vulnerabilities refer to formal and informal power inequities in relationships that may lead to undue pressure. While this may lead women to be over-represented, it may lead potential minority donors not to donate. Harding explains:

Prospective living donors may be challenged with barriers created by their own friends, family, and even the intended recipients. Many potential donors have reported having to defend themselves from friends and family who persistently question their wisdom in donating. Negative responses from everyone involved can deter living donation. [[48] at pp. 166–7].

The negative responses of friends and family coupled with a potential donor’s respect and/or dependence on them may create an influence that the potential donor cannot overcome. The lack of support for donation among family and social networks may explain, at least in part, why Blacks are less likely to complete living donor work-up and are less likely to be living donors. [63–65]

Social vulnerability refers to whether the living donors belong to a group whose interests have been socially disvalued. Given that donors and recipients are usually of the same race/ethnicity and SES group, potential donors and recipients may share social vulnerabilities that exacerbates their negative impact. For example, the lack of awareness by the health care providers of the racial disparities in kidney transplantation may result in failure to provide the necessary supports that minority patients in ESRD may need to overcome personal and structural barriers toward seeking kidney transplantation. [66,67] Multiple studies confirm that Black patients, older patients, obese patients, uninsured patients, and Medicaid-insured patients less likely to receive education about transplantation, [68–70] despite the 2005 and 2008 Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ (CMS’) Conditions for Coverage for ESRD facilities that required education about transplantation. [71] As Waterman et al. point out:

Transplant educators in dialysis centers (predominantly nurses and dialysis social workers) themselves report having limited time and knowledge to successfully educate patients about transplantation, with educators at for-profit dialysis centers less likely to administer high-quality, more intensive transplant educational strategies (e.g., one-on-one discussions) compared with nonprofit centers (references omitted). [[72] at pp. 1617–8].

Part of the reason for Blacks being under-represented as living donors, then, may be that they are not being asked to be living kidney donors by their loved ones in ESRD. Candidates may not ask because 1) they did not receive adequate education about the benefits of living donor transplantation and the low knowledge of living donation in their social networks reinforces their silence; 2) they fear the potential donor may refuse; 3) Black recipients and Black donors worry about long-term health of Black donors; 4) cultural attitudes about not sharing health problems makes it difficult for potential Black donors to know that they are needed; and 5) the implicit bias of some transplant professionals that Black patients with ESRD would not want a transplant. [48,54,65,73] How much of these are environmental and modifiable, and what interventions may be effective need to be explored.

Medical vulnerability refers to whether “the potential living donor been selected, in part, because of the presence of a serious health-related condition in the intended recipient for which there are only less satisfactory alternative remedies?” Virtually all patients in ESRD would do better with a transplant compared with dialysis, and survival of a living donor graft is, on average, far better than a deceased donor graft. [74] Friends and relatives of candidates face medical vulnerability in that the candidates may ask them to serve as a living donor. However, any attempt to increase Black living donation must confront the fact that multiple studies have shown that Black living donors are at greater risk for ESRD, particularly young Black male donors. [75]

Situational vulnerability refers to the medical exigency of the intended recipient that precludes adequate education of and deliberation by the potential living donor. As noted above, the most common scenario is in the case of acute liver failure where living liver donors must be evaluated and make decisions in a very short time frame. ALF is the prototypical case of situational vulnerability in living donor organ transplantation when living donor evaluation must be done quickly with limited time for the potential donor to reflect. ALF occurs in all racial and ethnic groups. In a cohort in the US “of 927 subjects (81.8% white, 12.8% black and 5.4% Asian), enrolled between January 1998 and March 2006, age, gender and level of education were comparable among the groups.” [76] However, many patients with ALF improve without transplantation, and when transplantation occurs, the vast majority of candidates receive a deceased donor liver graft so this is an unlikely cause of racial disparities in living donor transplantation.

Allocational vulnerability focuses on the potential living donor who is lacking in subjectively important social goods that she believes will be provided as a consequence of participation as a donor. Social goods can include, for example, improved familial social status or improved intrafamilial relationships. For Black living donors, this may not be the case. One qualitative study found that Black living donors “encountered negative responses from others about the donors’ desire to donate and the initial refusal of recipients to accept a LDKT [living donor kidney transplant] offer.”[[65] at p. 671] Culturally sensitive educational programs are needed to overcome these barriers. [77,78]

Infrastructural:

Does the political, organizational, economic, and social context of the donor care setting possess the integrity and resources needed to manage living donation? First, living kidney donation may be a bigger barrier for those of lower SES, especially for those who have physical requirements for employment (lifting heavy boxes for example). [30,79] Since donors often “look like” recipients in terms of SES, the financial barriers may be tougher on those of lower income, consistent with the greater drop off in living donation among low SES Blacks after the financial crisis of 2008. [6] This has led many to talk about reimbursement of wages, health insurance for donors and other financial resources to make it possible for all to be able to donate. [80,81] The transplant community has been fighting for legislation to permit some donor reimbursement to make donation financially neutral. On December 29, 2019, a proposed rule was published in the Federal Register entitled “Removing Financial Disincentives to Living Organ Donation”. [82] Final rule was published September 22, 2020 and went into effect on October 22, 2020. [83] Its actual impact remains to be seen.

Concern about income loss for living donors may affect decision-making by both transplant candidates and potential donors. In a study of two centers with over 450 candidates and transplant recipients, Rodrigue et al. found:

One-third (32%) were told by a family member/friend that they were willing to donate but were concerned about potential lost income. The majority of those who expressed financial concern (64%) did not initiate donation evaluation. Many patients (42%) chose not to discuss living donation with a family member/friend due to concern about the impact of lost income on the donor. In the multivariable model, lower annual household income was the only statistically significant predictor of both having a potential donor expressing lost income concern and choosing not to talk to someone because of lost income concern. [[79] at p. 292].

As noted above, the financial barriers to donation are not limited to lost wages and out of pocket expenses, but also include potential for loss of work-related benefits, including health insurance. Approximately 20% of donors lack health insurance, and this is more common in ethnic minorities, [34,35] which exposes them to less access to needed life-long care post nephrectomy.

A second potential infrastructural barrier is health literacy. [84,85] While health illiteracy is an issue for all racial and ethnic groups, Hispanics and Blacks have a higher rate of health illiteracy. [86] At the systems (infrastructural) level, health care professionals may be unwilling to promote potential donor understanding by using simpler language and/or employing decision aids or videos to improve comprehension and overcome literacy barriers that exist. This may be complicated by poor communication skills, lack of cultural awareness, or implicit bias of health care professionals which may contribute to the current under-representation of Black living donors, particularly those of lower educational and lower SES. [47,48,54,87] Whether and to what extent health illiteracy may be surmountable by an LDA(T) needs to be determined.

Third, some of the barriers to living donor transplantation by Blacks may also reflect structural racism. [48,87] Racial disparities can result from clinicians’ misinterpretation of patients’ indecision or passivity as lack of interest. [73,88] Clinician complacency about referring Blacks for transplantation because they are reported to have a high quality of life on dialysis also leads to referral delays. [46–48] For example, in a survey of 278 nephrologists and 606 patients, Ayanian and colleagues asked about quality of life and survival for Black and White patients undergoing renal transplantation and reasons for racial differences in access to transplantation. They found that:

[p]hysicians were less likely to believe transplantation improves survival for blacks than whites (69% versus 81%; P < 0.001), but similarly likely to believe it improves quality of life (84% versus 86%). Factors commonly cited by physicians as important reasons why blacks are less likely than whites to be evaluated for transplantation included patients’ preferences (66%), availability of living donors (66%), failure to complete evaluations (53%), and comorbid illnesses (52%). Fewer physicians perceived patient-physician communication and trust (38%) or physician bias (12%) as important reasons. [[73] at p. 350].

A fourth infrastructural challenge is the fact that many dialysis units and transplant programs are ill equipped and even uninformed as to how to address the risks posed by APOL1 for the living donor and her recipient. [89] As noted above, no data exist regarding graft survival from Black living donors based on the number of donor APOL1 risk alleles. Nor are there data regarding what impact the unilateral nephrectomy has on living donor clinical outcomes. Nevertheless, some transplant programs are ruling out some Black donors based on ApoL1 status, [90,91] which may exacerbate the shortage of Black living donors despite lack of conclusive evidence that these donors and their grafts have worse outcomes.

How to address these infrastructural vulnerabilities needs to be studied.

In sum, while all donors are at risk for a variety of vulnerabilities, there are reasons to believe that Black donors may be at greater social, allocational, and infrastructural vulnerabilities due to lack of awareness of the benefits, misconceptions of the risks, and racism at the individual, social/cultural and institutional levels. To increase living donation in the Black community, we need culturally tailored educational resources to increase knowledge and awareness, social support provided by transplant programs, and reduced financial disincentives. Since living kidney donation may require costs to travel, costs of meals, as well as the need to take time off from work, potential Black living donors without adequate financial flexibility may not be able to donate. Ensuring that these costs are covered for living donors would likely increase the number of Black living donors.

There are also reasons, however, why some level of lower donation rate in the Black community may be appropriate given that living donation does have health risks to donors and these risks are more frequent in Black living donors. Data show that post-donation, Blacks have an even greater risk than other donors for developing hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and ESRD and that their risk of developing these conditions is increased over their non-donor Black counterparts. [75]

6. Conclusion

There are many reasons why women may be over-represented and Blacks under-represented as living donors. Our vulnerabilities analyses show that these differences may not be mere preferences but may reflect serious justice concerns that need to be addressed at both the individual and systems levels. At the individual level, the LDAT must help living donors identify and address their various vulnerabilities in a shared decision-making process that allows them to decide whether or not the benefits of donation outweigh the risks and harms. At the systems level, the transplant community needs to take a more proactive role in addressing structural challenges (e.g. inadequate education at dialysis centers) and work to remove or at least reduce the institutional and systemic inequities (structural racism and sexism) that threaten Black and female potential donors from making decisions that best reflect their own preferences, interests, and needs.

Additional research that engages potential and actualized donors regarding the barriers they face and the factors that facilitate their decision-making and the donation process is needed. The research should address obstacles and support generated from both the transplant centers and from the (potential) donors’ social networks. This information would enable the LDAT to empower donors to make decisions that best reflect their values and goals.

Funding

This research was funded in part by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Investigator Award in Health Policy.

Abbreviations

- APOL1

Apolipoprotein 1

- CMS

Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- KAS

kidney allocation system

- LDA

living donor advocate

- LDAT

living donor advocate team

- OPTN

Organ Transplantation Network

- PRA

panel reactive antibodies

- SES

socioeconomic status

- SRTR

Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipients

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

- US

United States

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest

None.

References

- [1].Merill JP, Harrison JH, Murray J, Guild WR. Successful homotransplantation of the kidney in an identical twin. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 1956;67:166–73. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Murray JE. Proceedings: human kidney transplant conference. Transplantation. 1964;2:147–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Murray JE, Barnes BA, Atkinson J. Fifth report of the human kidney transplant registry. Transplantation. 1967;5:752–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Advisory Committee to the Renal Transplant Registry. The 12th report of the human renal transplant registry. JAMA. 1975;233:787–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network). National data. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/.

- [6].Gill J, Dong J, Rose C, Johnston O, Landsberg D, Gill J. The effect of race and income on living kidney donation in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24:1872–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gill JS, Gill J, Barnieh L, et al. Income of living kidney donors and the income difference between living kidney donors and their recipients in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3111–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ross LF, Thistlethwaite JR. Developing an ethics framework for living donor transplantation. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:843–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kipnis K Vulnerability in research subjects: a bioethical taxonomy. The National Bioethics Advisory Commission (NBAC). Ethical and policy issues in research involving human participants volume ii commissioned papers and staff analysis. Bethesda, MD: National Bioethics Advisory Commission; August 2001. p. G1–13. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kipnis K Seven vulnerabilities in the pediatric research subject. Theor Med Bioeth. 2003;24:107–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ross LF, Thistlethwaite JR. The prisoner as living organ donor. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2018;27:93–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Carrero JJ, Hecking M, Chesnave NC, Jager KJ. Sex and gender disparities in the epidemiology and outcomes of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018;14: 151–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Goldberg I, Krause I. The role of gender in chronic kidney disease. EMJ. 2016;1: 58–64. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Melk A, Babitsch B, Borchert-Mörlins B, et al. Equally interchangeable? How sex and gender affect transplantation. Transplantation. 2019;103:1094–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Terasaki PI, Cecka JM, Gjertson DW, Takemoto S. High survival rates of kidney transplants from spousal and living unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:333–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Jindal RM, Ryan JJ, Sajjad I, Murthy MH, Baines LS. Kidney transplantation and gender disparity. Am J Nephrol. 2005;25:474–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].The New York Times Editorial Staff, editor. The gender pay gap: equal work, unequal pay (in the headlines). 1st ed. New York: The New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Frech A, Natale G, Tumin D. Couples’ employment after spousal kidney donation. Soc Work Health Care. 2018;57:880–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Advisory Committee to the Renal Transplant Registry. The 13th report of the human renal transplant registry. Transplant Proc. 1977;9:9–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Reese PP, Nair M, Bloom RD. Eliminating racial disparities in access to living donor kidney transplantation: how can centers do better? Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59 751–3 at p. 751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].United States Census Bureau. Quick facts. On the web at: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219.

- [22].Tong A, Chapman JR, Wong G, Kanellis J, McCarthy G, Craig JC. The motivations and experiences of living kidney donors: a thematic synthesis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60: 15–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Simmons RG, Marine SK, Simmons RL. Gift of life: The effect of organ transplantation on individual, family, and societal dynamics. New Brunswick NJ: Transaction Books; 2002. [Second printing]. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Jacobs C, Johnson E, Anderson K, Gillingham K, Matas A. Kidney transplants from living donors: how donation affects family dynamics. Adv Ren Replace Ther. 1998;5: 89–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kayler LK, Meier-Kriesche H-U, Punch JD, et al. Gender imbalance in living donor renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2002;73:248–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Oh C-K, Kim SJ, Kim JH, Shin GT, Kim HS. Influence of donor and recipient gender on early graft function after living donor kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2004; 36:2015–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ashby VB, Leichtman AB, Rees MA, Song PX-K, Bray M, Wang W, et al. A kidney graft survival calculator that accounts for mismatches in age, sex, HLA, and body size. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:1148–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Campsen J, Blei AT, Emond JC, et al. For the adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation cohort study group. Outcomes of living donor liver transplantation for acute liver failure: the adult-to-adult living donor liver transplantation cohort study. Liver Transpl. 2008;14:1273–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gill J, Joffres Y, Rose C, et al. The change in living kidney donation in women and men in the United States (2005–2015): a population-based analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:1301–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Clarke KS, Klarenbach S, Vlaicu S, Yang RC, Garg AX. The direct and indirect economic costs incurred by living kidney donors—a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:1952–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].LaPointe Rudow D, Hays R, Baliga P, et al. Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:914–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Gaston RS, Danovitch GM, Epstein RA, Kahn JP, Matas AJ, Schnitzler MA. Limiting financial disincentives in live organ donation: a rational solution to the kidney shortage. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:2548–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Maggiore U, Budde K, Heemann U, the ERA-EDTA (European Renal Association-European Dialysis and Transplant Association) DESCARTES (Developing Education Science and Care for Renal Transplantation in European States) Working Group, et al. Long-term risks of kidney living donation: review and position paper by the ERA-EDTA DESCARTES working group. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2017;32:216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Gibney EM, Doshi MD, Hartmann EL, Parikh CR, Garg AX. Health insurance status of US living kidney donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (CJASN). 2010;5:912–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Casagrande LH, Collins S, Warren AT, Ommen ES. Lack of health Insurance in Living Kidney Donors. Clin Transplant. 2012;26:E101–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000;49:147–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Shah LC, West P, Bremmeyr K, Savoy-Moore RT. Health literacy instrument in family medicine: the ‘Newest Vital Sign’ ease of use and correlates. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Christy SM, Gwede CK, Sutton SK, et al. Health literacy among medically underserved: the role of demographic factors, social influence, and religious beliefs. J Health Commun. 2017;22:923–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Clouston SAP, Manganello JA, Richards M. A life course approach to health literacy: the role of gender, educational attainment and lifetime cognitive capability. Age Ageing. 2017;46:493–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Garg AX, Nevis IF, McArthur E, For the DONOR Network, et al. Gestational hypertension and preeclampsia in living kidney donors. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:124–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Davis S, Dylewski J, Shah PB, Holmen J, You Z, Chonchol M, et al. Risk of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes during pregnancy in living kidney donors: a matched cohort study. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Reese PP, Boudville N, Garg AX. Living kidney donation: outcomes, ethics and uncertainty. Lancet. 2015;385 2003–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Department of Health and Human Services Part II. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 42 DFR Parts 405, 482, 488 and 498. Medicare Program; Hospital Conditions of Participation: Requirements for approval and re-approval of transplant centers to perform organ transplants; Final Rule. Fed Regist. 2007;72:15198–280 March 30, 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Lentine KL, Segev DL. Understanding and communicating medical risks for living kidney donors: a matter of perspective. J Am Soc Nephrol (JASN). 2017;28:12–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Schaubel DE, Stewart DE, Morrison HI, Zimmerman DL, Cameron JI, Jeffrey JJ, et al. Sex inequality in kidney transplantation rates. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2349–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Purnell TS, Luo X, Cooper LA, et al. Association of race and ethnicity with live donor kidney transplantation in the United States from 1995 to 2014. JAMA. 2018;319: 49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Institute of Medicine (IOM). Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Harding K, Mersha TB, Pham P-T, et al. Health disparities in kidney transplantation for African Americans. Am J Nephrol. 2017;46:165–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Harris MI, Flegal KM, Cowie CC, et al. Prevalence of diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, and impaired glucose tolerance in U.S. adults. The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:518–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Carson AP, Howard G, Burke GL, et al. Ethnic differences in hypertension incidence among middle-aged and older adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Hypertension. 2011;57:1101–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Ladin K, Hanto DW. Understanding disparities in transplantation: do social networks provide the missing clue? Am J Transplant. 2010;10:472–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Weng FL, Reese PP, Mulgaonkar S, Patel AM. Barriers to living donor kidney transplantation among black or older transplant candidates. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (CJASN). 2010;5:2338–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lunsford SL, Simpson KS, Chavin KD, et al. Racial disparities in living kidney donation: is there a lack of willing donors or an excess of medically unsuitable candidates? Transplantation. 2006;82:876–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Patzer RE, McClellan WM. Influence of race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status on kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:533–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010;329:841–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Foster MC, Coresh J, Fornage M, et al. APOL1 variants associate with increased risk of CKD among African Americans. J Am Soc Nephrol (JASN). 2013;24:1484–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Parsa A, Kao WH, Xie D, et al. APOL1 risk variants, race, and progression of chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:2183–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Palanisamy A, Reeves-Daniel AM, Freedman BI. The impact of APOL1, CAV1, and ABCB1 gene variants on outcomes in kidney transplantation: donor and recipient effects. Pediatr Nephrol. 2014;29:1485–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1025–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Mjøen G, Hallan S, Hartmann A, et al. Long-term risks for kidney donors. Kidney Int. 2014;86:162–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Muzaale AD, Massie AB, Wang MC, et al. Risk of end-stage renal disease following live kidney donation. JAMA. 2014;311:579–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Ross LF, Thistlethwaite JR Jr. Introducing genetic tests with uncertain implications in living donor kidney transplantation: ApoL1 as a case study. Prog Transplant. 2016; 26:203–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Alexander G, Sehgal A. Why hemodialysis patients fail to complete the transplantation process. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;37:321–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Clark CR, Hicks LS, Keogh JH, Epstein AM, Ayanian JZ. Promoting access to renal transplantation: the role of social support networks in completing pre-transplant evaluations. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1187–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Davis LA, Grogan TM, Cox J, Weng FL. Inter- and intrapersonal barriers to living donor kidney transplant among black recipients and donors. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2017;4:671–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Kim JJ, Basu M, Plantinga L, et al. Awareness of racial disparities in kidney transplantation among health care providers in dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (CJASN). 2018; 13:772–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Lipford KJ, McPherson L, Hamoda R, et al. Dialysis facility staff perceptions of racial, gender, and age disparities in access to renal transplantation. BMC Nephrol. 2018; 19:5 2018 01 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Hyland SS, McCabe MS, Schenk EA, Liu J. Modifiable patient characteristics and racial disparities in evaluation completion and living donor transplant. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (CJASN). 2013;8:995–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Balhara KS, Kucirka LM, Jaar BG, Segev DL. Disparities in provision of transplant education by profit status of the dialysis center. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:3104–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Gander JC, Zhang X, Ross K, et al. Association between Dialysis facility ownership and access to kidney transplantation. JAMA. 2019;322:957–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- [71].Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services: Medicare and Medicaid Programs. Conditions for coverage for end-stage renal disease facilities; final rule. In: Department of Health and Human Services, editor. Fed Reg, 73. ; 2008. p. 20369–484 (April 15, 2008). Available at https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2008/04/15/08-1102/medicare-and-medicaid-programs-conditions-for-coverage-for-end-stage-renal-disease-facilities. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Waterman AD, Peipert JD, Goalby CJ, Dinkel KM, Xiao H, Lentine KL. Assessing transplant education practices in dialysis centers: comparing educator reported and medicare data. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1617–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ayanian JZ, Clearly PD, Keogh JH, Noonan SJ, David-Kasdan JA, Epstein AM. Physicians’ beliefs about racial differences in referral for renal transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;43:350–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Chadban SJ, Ahn C, Axelrod DA, et al. Summary of the kidney disease: improving global outcomes (KDIGO) clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and management of candidates for kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2020;104:708–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Lentine KL, Lam NN, Segev DL. Risks of living kidney donation: current state of knowledge on outcomes important to donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol (CJASN). 2019;14:597–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Forde KA, Reddy KR, Troxel AB, Sanders CM, Lee WM, For the Acute Liver Failure Study Group. Racial and ethnic differences in presentation, etiology and outcomes of acute liver failure in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7: 1121–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Rodrigue JR, Paek MJ, Egbuna O, et al. Making house calls increases living donor inquiries and evaluations for blacks on the kidney transplant waiting list. Transplantation. 2014;98:979–86. 10.1097/TP.0000000000000165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Waterman AD, Rodrigue JR, Purnell TS, Ladin K, Boulware LE. Addressing racial/ethnic disparities in live donor kidney transplantation: priorities for research and intervention. Semin Nephrol. 2010;30:90–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Mandelbrot DA, Taber DJ, Phan V, Baliga PK. Concern for lost income following donation deters some patients from talking to potential living donors. Prog Transplant. 2016;26:292–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Przech S, Garg AX, Arnold JB, et al. Financial costs incurred by living kidney donors: a prospective cohort study and on behalf of the Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) network. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:2847–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Bailey P, Tomson C, Risdale S, Ben-Shlomo Y. From potential donor to actual donation: does socioeconomic position affect living kidney donation? A systematic review of the evidence. Transplantation. 2014;98:918–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). Proposed rule: removing financial disincentives to living organ donation. Fed Regist. 2019;84:70139–45 (December 20, 2019). On the web at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2019/12/20/2019-27532/removing-financial-disincentives-to-living-organ-donation. [Google Scholar]

- [83].Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), Health and Human Services Department (HHS). Final rule: removing financial disincentives to living organ donation. 42 CFR 121. Fed Regist. 2020;85:59438–45 (September 22, 2020). On the web at: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2020/09/22/2020-20804/removing-financial-disincentives-to-living-organ-donation. [Google Scholar]

- [84].United States Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National action plan to improve health literacy. Washington DC: United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [85].Institute of Medicine. Promoting health literacy to encourage prevention and wellness: Workshop summary. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [86].Institute of Medicine Committee on Health Literacy. Health literacy: A prescription to end confusion. Washington DC: National Academies Press; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Norris K, Nissenson AR. Race, gender, and socioeconomic disparities in CKD in the United States. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2008;19:1261–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Humi AM, Sullivan CM, Pencak JA, Sehgal AR. Accuracy of dialysis medical records in determining patient interest in and suitability for transplantation. Clin Transplant. 2013;27. 10.1111/ctr.12147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Newell KA, Formica RN, Gill JS, et al. Integrating APOL1 gene variants into renal transplantation: considerations arising from the American Society of Transplantation Expert Conference. Am J Transplant. 2017;17 901–911 at p. 905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Gordon EJ, Wicklund C, Lee J, Sharp RR, Friedewald J. A national survey of transplant surgeons and nephrologists on implementing apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) genetic testing into clinical practice. Prog Transplant. 2019;29:26–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].McIntosh T, Mohan S, Sawinski D, Iltis A, DuBois J. Variation of ApoL1 testing practices for living kidney donors. Prog Transplant. 2020;30:22–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]