COVID-19 and police brutality have simultaneously heightened public awareness of disparities in health outcomes by race/ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status, and the underlying structural drivers of systemic racism and social privilege in the USA.1,2 Increasingly major professional associations such as the American Medical Association, American Hospital Association, and Association of American Medical Colleges are decrying racism and inequities, and many individual healthcare organisations are committing to addressing health disparities. Hospitals, clinics and health plans are looking inwards to identify organisational biases and discrimination, and developing outward interventions to advance health equity for their patients. Looking in the mirror honestly takes courage; frequently the discoveries and self-insights are troubling.3 At their best, discussions about racism and inequities are challenging.4 Within the quality of care field, disparities in patient safety are relatively understudied.5,6 Thus, Schulson et al’s study in this issue of BMJ Quality and Safety, finding that voluntary incident reporting systems may underdetect safety issues in marginalised populations, is an important sentinel event.7 Implicit bias in providers and structural bias in safety reporting systems might explain this underdetection of problems.

In this editorial, I summarise the practical lessons for advancing health equity sustainably, with the hope of accelerating equity in patient safety. I present a framework for advancing health equity, describe common pitfalls and apply the framework to patient safety to inform research and policy recommendations. The wider health disparities field has been criticised for spending too many years describing the phenomenon of inequities before emphasising interventions and solutions. The patient safety field should move faster, incorporating major advances that have occurred regarding how to reduce health disparities.8,9 While equity issues in patient safety have been understudied, the principles for successfully advancing health equity align well with the culture and toolkit of the safety field.10 Thus, achieving equitable patient safety is a realistic and important opportunity.

My lessons are from the ‘school of hard knocks’: over 25 years of performing multilevel health disparities research and interventions locally,11 nationally9,12,13 and internationally.14 I have been fortunate to work with many passionate, inspirational staff and leaders from healthcare and the community who have demonstrated that advancing health equity is not a mirage—it can be done.

A FRAMEWORK FOR ADVANCING HEALTH EQUITY

The WHO defines health equity as ‘the absence of unfair and avoidable or remediable differences in health among population groups defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically’.15 To achieve health equity, people should receive the care they need, not necessarily the exact same care.16

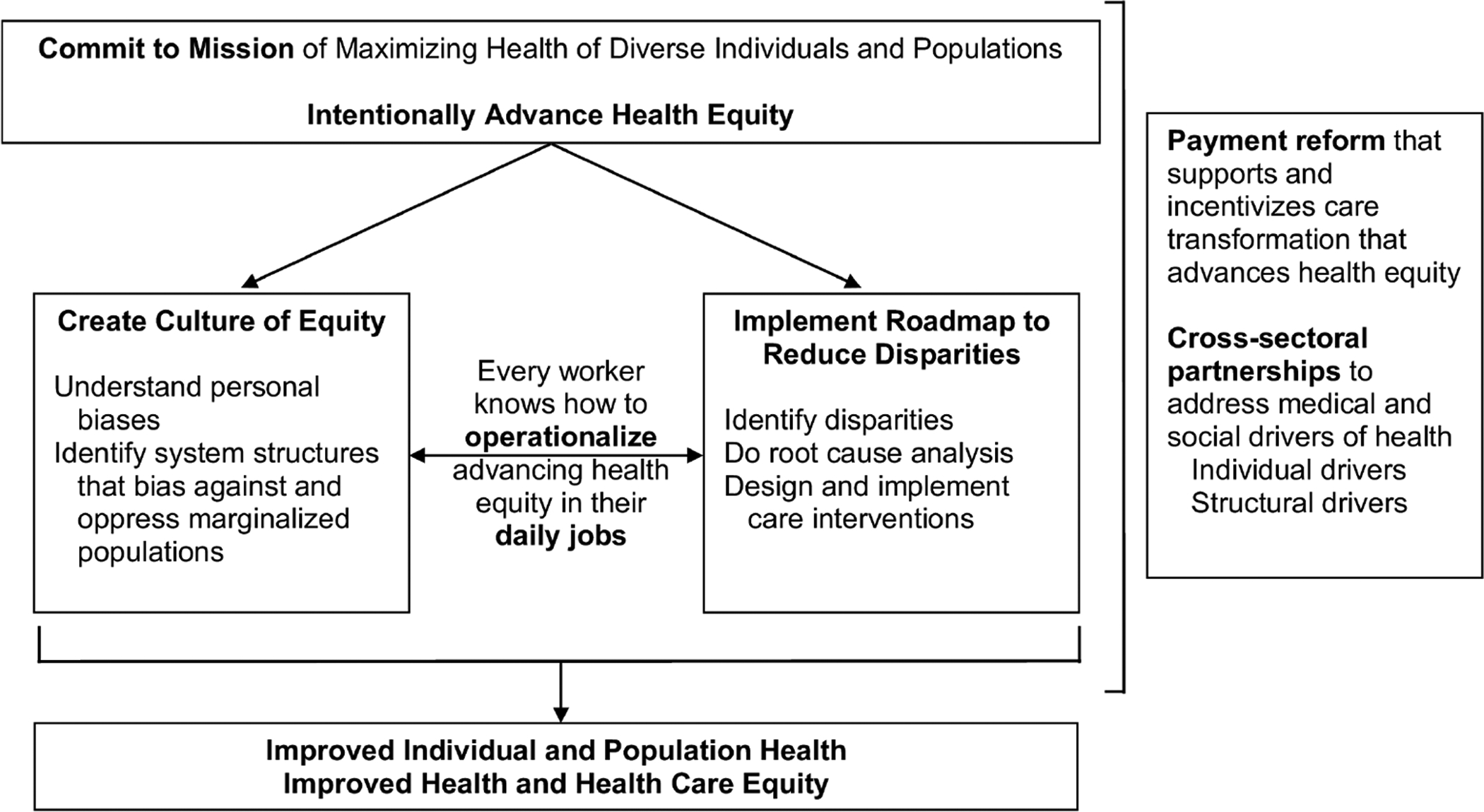

I summarise a framework for advancing health equity (figure 1). In brief, individuals and organisations must commit to the mission of maximising the health of diverse individuals and populations. Their actions, policies and procedures must intentionally advance health equity. This intentional design to advance health equity consists of two simultaneous tracks: (1) Create a culture of equity in which the whole organisation—senior leadership, mid-level management, front-line staff and clinicians—truly values and buys in to the mission of advancing health equity.17 Developing a culture of equity requires an inward personal look for biases as well as examination for systematic structures within the organisation that bias against and oppress marginalised groups. (2) Implement the Road Map to Reduce Disparities.9,18 Road map principles are the tenets of good quality improvement, emphasising an equity lens that tailors care to meet the needs of diverse patients rather than a one-size-fits-all approach. Key steps of the road map are to: identify disparities with stratified clinical performance data and input of clinicians, staff and patients; do a root cause analysis of the drivers of the disparities; and design and implement care interventions that address the root causes in collaboration with the affected patients and populations. These actions will ultimately improve individual and population health and improve health and healthcare equity.

Figure 1.

Creating a culture of equity and implementing the concrete actions of the road map are equally important for change. Management consultant Peter Drucker’s famous aphorism that ‘Culture eats strategy for breakfast’ applies to equity work. Technically sound disparity interventions and strategies will not be implemented or sustained unless equity is an organisational priority among all workers. Similarly, well-meaning intentions will not take an organisation far unless accompanied by concrete actions. The key bridge between a culture of equity and road map principles is that every worker in the organisation, from the chief executive officer to front-line staff, must know how to practically operationalise advancing health equity in their daily jobs. Successful application of these lessons is in part interacting effectively with diverse persons, as classically taught in cultural humility classes.19 However, operationalisation goes beyond interpersonal relations to each worker knowing how they should perform their daily jobs with an equity lens and reform the structures in which they work, regardless of whether they are working in clinical care, data analytics, quality improvement, strategic operations, finances, patient experience, environmental services, health information technology or human resources. Leadership needs to provide front-line staff with the training and support necessary for success. The wider environment requires payment reform that supports and incentivises care transformation that advances health equity.20–22 Partnerships across health and social sectors need to align goals and efforts to address the medical and social drivers of health, both drivers for individual persons as well as the underlying systematic structural drivers.23

COMMON PITFALLS

(1). Not being intentional about advancing health equity.

Relying on magical thinking.

When I ask healthcare leaders what they are doing to advance health equity, I frequently hear well-meaning statements such as: ‘We’re already doing quality improvement.’ ‘We’re a safety-net organization that cares for the most vulnerable persons. It’s who we are.’ ‘The shift from fee-for-service payment to value-based payment and alternative payment models will fix things.’ Such statements are variants of the ‘rising tide lifts all boats’ philosophy and the belief that the ‘invisible hand’, whether it be general free market principles, a general system of quality improvement and patient safety, or general commitment to serving marginalised populations, will suffice in reducing health disparities. Yet, disparities stubbornly persist in quality of care and outcomes by race, ethnicity and socioeconomic status.24

Culturally tailored care interventions that address the underlying causes of disparities often work better than default one-size-fits-all approaches.25 However, the ‘invisible hand’ incentives in general quality improvement and pay-for-performance approaches are frequently too weak to drive organisations to tailor approaches to advance health equity,13 and can even be counterproductive. Rather than implement individualised, tailored care that can improve outcomes for diverse minority populations, some organisations perceive that it is easier to improve their aggregate patient outcomes or clinical performance per dollars spent by investing resources in the general system of care, or by intentionally or unintentionally erecting barriers that make it harder for marginalised populations to access their system of care. For example, persons living in zip code areas that have higher percentages of African Americans or persons living in poverty have less access to physicians practising in accountable care organisations.26,27 Moreover, inadequately designed incentive systems can penalise safety-net hospitals that care for marginalised populations, leading to a downward spiral in quality of care and outcomes. The initial iteration of Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) reduced Medicare payments to safety-net hospitals by 1%–3% and increased readmission rates for black patients in these hospitals.28 Directed by legislation passed by Congress, the Medicare programme intentionally addressed this equity problem in the HRRP in 2019 by stratifying hospitals by proportion of patients dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid, so that a given hospital’s clinical performance would be compared with that of hospitals with a similar prevalence of poverty when calculating financial rewards and penalties.29

(2). Focusing exclusively on cultural humility or implicit bias training and avoiding looking for systemic, structural drivers of inequities.

Many organisations institute cultural humility or implicit bias training as their equity intervention.19 While an important and essential component of creating a culture of equity, such training must be accompanied by hard examination for structural processes that lead to inequities. For example, in a project designed to decrease hospital length of stay, the University of Chicago Medicine data analytics group discovered that the process the organisation had proposed for developing and using machine learning predictive algorithms to identify patients for intervention would have systematically shifted resources away from African Americans to more affluent white patients.30,31 This inequitable process was caught before implementation, and now the data analytics group is proactively building analytical processes to advance health equity.

(3). Insufficiently engaging patients and community.

Too often perfunctory or no efforts are made to meaningfully engage patients and community in quality improvement and patient safety efforts. Patients and families frequently feel they have not been heard and that their experiences and preferences are not adequately valued.32,33 A common mistake is using proxies for the community rather than the actual community. One organisation we worked with sought advice from Latinx (gender-neutral, non-binary term to indicate of Latin American descent) healthcare workers to design an intervention to reduce disparities in the outcomes of their Latinx patients with depression, rather than speaking with actual patients. The organisation designed a telephone intervention that failed, partly because their patients frequently had pay-by-the-minute cellphone plans rather than unlimited minute cellphone plans that were probably more commonly used by the Latinx employees. Few patients agreed to enrol in the intervention because of cost.

(4). Marginalising equity efforts rather than involving the whole organisation.

Frequently healthcare organisations will do an isolated care demonstration project to reduce disparities or appoint a siloed chief equity officer rather than mobilising the whole organisation to advance health equity. It helps having health equity leaders with dedicated resources to catalyse reform, but meaningful sustainable change only occurs when everyone makes it their job to improve health equity. Most organisations do not engage in substantive discussions with payers regarding how to support and incentivise disparities reduction, nor consider how cross-sector partnerships can be organised in effective and financially sustainable ways.

(5). Requiring a linear, stepwise process for reducing disparities and allowing the ‘perfect to be the enemy of the good’.

For example, some organisations get stuck collecting race/ethnicity/language data so they can stratify their clinical performance measures by these factors. Such stratified data are valuable but it can be time consuming to establish the initial data collection systems. While those efforts are ongoing, other projects could occur. These additional projects could include creating a culture of equity, and identifying disparity problems based on clinician, staff and patient input, and then designing and implementing interventions to mitigate them.34

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE PATIENT SAFETY FIELD TO ADVANCE HEALTH EQUITY

I offer several recommendations to inform research, policy and practical action.

(1). Broaden collaborators to include experts on racism, intersectionality and systems of oppression.3,4,35

A great strength of the patient safety field is its interdisciplinary team approach. However, it is difficult for even the most well-meaning people to understand what they have not experienced. A recent powerful formative experience for me was living in Aotearoa/New Zealand for several months and writing a paper with diverse international colleagues comparing what Aotearoa/New Zealand and the USA were doing to advance health equity.14 After dozens of frank conversations with my Maori coauthors, I began to understand in depth the devastating nature of colonialism, and the overt and insidious ways power structures can oppress marginalised populations. Increasing the diversity of lived experiences and expertise on patient safety teams is critical, and requires a hard look for systemic biases in hiring practices and procedures.

(2). Examine safety criteria and systems for bias. Design and implement equitable systems for identifying, measuring and eliminating safety problems.

Patient safety is an inherently complex field that will require explicit and implicit criteria to capture and monitor problems.36,37 Schulson et al’s paper highlights how voluntary reporting systems can introduce bias.7 In practice, automatic and voluntary reporting systems have different strengths and weaknesses that will require careful integration to maximise the chance that equitable safety outcomes will be attained. Automated measures are explicit review measures that are objective but can be relatively crude and limited for capturing safety issues. In general, voluntary measures are implicit review measures that are subject to a variety of personal and judgement biases but which are more comprehensive and potentially richer. Given that individual discretion is used in voluntary reporting, reports could be grouped into different categories based on degree of legitimate discretion. Such categorisation could help identify whether variation across different patient groups in rates of reported safety defects occurs primarily among criteria with legitimate discretion versus ones where variation likely reflects implicit bias. Diverse workers and patients should be empowered to help create and implement the safety systems and report potential safety problems.33

(3). View failures in treatment plans due to social determinants of health as safety issues.

A treatment plan that is likely to fail because of social challenges is a safety problem. Discharging a patient from the hospital when they are medically stable but likely to have poor outcomes because of homelessness is a safety problem. If the purpose of healthcare is to maximise health, then healthcare organisations must collaborate with community partners to address medical and social issues.38

(4). Develop validated patient safety equity performance measures.

What is measured and rewarded influences what is done.39,40 Safety equity measures could include general safety measures stratified by social factors such as race/ethnicity, population health metrics incorporating the impact of medical and social interventions,41 and structural and process measures such as procedures that incorporate marginalised populations in the safety review process or use safety checklists with explicit consideration of equity at key junctures.30,42

(5). Use a full implementation science framework to maximise the chance of effective scale-up and spread of patient safety interventions that advance health equity.

Patient safety work has the strength of being an integral valued part of healthcare organisations’ operations. Thus, patient safety leaders, researchers and implementers frequently have a seat at the table when strategic planning is occurring regarding institutional priorities, system reform, financing and relations with external stakeholders such as payers. A strength of the patient safety field has been its ability to understand and shape culture, and its awareness of how inner and outer contexts affect systems change.43 These perspectives need to be intentionally viewed through an equity lens to reduce disparities.44,45 For example, American organisations need to honestly ask themselves to what extent they will advocate for payment policies that incentivise maximising population health and equitable patient safety rather than current payment systems that support too much low value care.38,46

(6). Ride and nurture the moral wave for equity in patient safety.

Intrinsic motivation is the most powerful driver of behaviour.47 People want to do the right thing, and they will do so if supported and provided the training and tools for success.48 Seize the opportunity presented by the heightened public readiness for addressing racism and inequities. Keep the momentum going. Now is the time for us to make strong, bold choices.49 We can make a difference and advance health equity, providing hope and the opportunity for a healthy life to all.50

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Peek ME, Simons RA, Parker WF, et al. COVID-19 among African Americans: an action plan for mitigating disparities. Am J Public Health 2020:e1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vela M, Blackman D, Burnet D, et al. Racialized violence and health care’s call to action. MedPage Today’s KevinMD.com: Social media’s leading physician voice, 2020. Available: https://www.kevinmd.com/blog/2020/06/racialized-violence-and-health-cares-call-to-action.html [Accessed 19 Nov 2020]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peek ME, Lopez FY, Williams HS, et al. Development of a conceptual framework for understanding shared decision making among African-American LGBT patients and their clinicians. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:677–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peek ME, Vela MB, Chin MH. Practical lessons for teaching about race and racism: successfully leading free, frank, and fearless discussions. Acad Med 2020;95:S139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chauhan A, Walton M, Manias E, et al. The safety of health care for ethnic minority patients: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 2020;19:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Piccardi C, Detollenaere J, Vanden Bussche P, et al. Social disparities in patient safety in primary care: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schulson LB, Novack V, Folcarelli PH. Inpatient patient safety events in vulnerable populations: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Qual Saf 2021;30:372–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Systems practices for the care of socially at-risk populations. Washington, D.C: The National Academies Press, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin MH, Clarke AR, Nocon RS, et al. A roadmap and best practices for organizations to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:992–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sivashanker K, Gandhi TK. Advancing equity and safety together. N Engl J Med 2020;382:301–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin MH, Goddu AP, Ferguson MJ, et al. Expanding and sustaining integrated health care-community efforts to reduce diabetes disparities. Health Promot Pract 2014;15:29S–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chin MH. Quality improvement implementation and disparities: the case of the Health Disparities Collaboratives. Med Care 2010;48:668–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.DeMeester RH, Xu LJ, Nocon RS, et al. Solving disparities through payment and delivery system reform: a program to achieve health equity. Health Aff 2017;36:1133–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chin MH, King PT, Jones RG, et al. Lessons for achieving health equity comparing Aotearoa/New Zealand and the United States. Health Policy 2018;122:837–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health: health equity. Available: https://www.who.int/topics/health_equity/en/ [Accessed 19 Nov 2020].

- 16.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. Visualizing health equity: one size does not fit all infographic, 2017. Available: https://www.rwjf.org/en/library/infographics/visualizing-health-equity.html [Accessed 19 Nov 2020].

- 17.Advancing Health Equity. Creating a culture of equity. Available: https://www.solvingdisparities.org/sites/default/files/Culture%20of%20Equity%20Strategy%20Overview%20Final%20Oct%202020_0.pdf [Accessed 19 Nov 2020].

- 18.Advancing Health Equity. Roadmap to reduce disparities. Available: https://www.solvingdisparities.org/tools/roadmap [Accessed 19 Nov 2020].

- 19.Smith A, Foronda C. Promoting cultural humility in nursing education through the use of ground rules. Nurs Educ Perspect 2019. doi: 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000594. [Epub ahead of print: 26 Nov 2019]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chin MH. Creating the business case for achieving health equity. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:792–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel S, Smithey A, Tuck K. Leveraging value-based payment models to advance health equity: a checklist for payers. Advancing health equity: leading care, payment, and systems change. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Chapter 3: Paying for equity in health and health care. In: The future of nursing 2020–2030: charting a path to achieve health equity. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2021. (forthcoming). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Integrating social care into the delivery of health care: moving upstream to improve the nation’s health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2018 national healthcare quality and disparities report. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher TL, Burnet DL, Huang ES, et al. Cultural leverage: interventions using culture to narrow racial disparities in health care. Med Care Res Rev 2007;64:243S–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasaitis LC, Pajerowski W, Polsky D, et al. Physicians’ participation in ACOs is lower in places with vulnerable populations than in more affluent communities. Health Aff 2016;35:1382–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fahrenbach J, Chin MH, Huang ES, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage and hospital quality ratings in the Medicare Hospital Compare Program. Med Care 2020;58:376–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaiyachati KH, Qi M, Werner RM. Changes to racial disparities in readmission rates after Medicare’s Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program within safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e184154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joynt Maddox KE, Reidhead M, Qi AC, et al. Association of stratification by dual enrollment status with financial penalties in the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA Intern Med 2019;179:769–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajkomar A, Hardt M, Howell MD, et al. Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:866–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hardt M, Chin MH. It is time for bioethicists to enter the arena of machine learning ethics. Am J Bioeth 2020;20:18–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez Jolles M, Richmond J, Thomas KC. Minority patient preferences, barriers, and facilitators for shared decision-making with health care providers in the USA: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns 2019;102:1251–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abid MH, Abid MM, Surani S, et al. Patient engagement and patient safety: are we missing the patient in the center? Cureus 2020;12:e7048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cook SC, Goddu AP, Clarke AR, et al. Lessons for reducing disparities in regional quality improvement efforts. Am J Manag Care 2012;18:s102–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bi S, Vela MB, Nathan AG, et al. Teaching intersectionality of sexual orientation, gender identity, and race/ethnicity in a health disparities course. MedEdPORTAL 2020;16:10970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spinewine A, Schmader KE, Barber N, et al. Appropriate prescribing in elderly people: how well can it be measured and optimised? Lancet 2007;370:173–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pronovost PJ, Nolan T, Zeger S, et al. How can clinicians measure safety and quality in acute care? Lancet 2004;363:1061–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen AH, Chin MH. What if the role of healthcare was to maximize health? J Gen Intern Med 2020;35:1884–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Quality Forum. A roadmap for promoting health equity and eliminating disparities: the four I’s for health equity, 2017. Available: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2017/09/A_Roadmap_for_Promoting_Health_Equity_and_Eliminating_Disparities__The_Four_I_s_for_Health_Equity.aspx [Accessed 19 Nov 2020].

- 40.Anderson AC, O’Rourke E, Chin MH, et al. Promoting health equity and eliminating disparities through performance measurement and payment. Health Aff 2018;37:371–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Leading health indicators 2030: advancing health, equity, and well-being. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Quality Forum. An environmental scan of health equity measures and a conceptual framework for measure development, 2017. Available: http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2017/06/An_Environmental_Scan_of_Health_Equity_Measures_and_a_Conceptual_Framework_for_Measure_Development.aspx [Accessed 19 Nov 2020].

- 43.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galaviz KI, Breland JY, Sanders M, et al. Implementation science to address health disparities during the coronavirus pandemic. Health Equity 2020;4:463–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spitzer-Shohat S, Chin MH. The “waze” of inequity reduction frameworks for organizations: a scoping review. J Gen Intern Med 2019;34:604–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shrank WH, Rogstad TL, Parekh N. Waste in the US health care system: estimated costs and potential for savings. JAMA 2019;322:1501–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nantha YS. Intrinsic motivation: how can it play a pivotal role in changing clinician behaviour? J Health Organ Manag 2013;27:266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chin MH. Movement advocacy, personal relationships, and ending health care disparities. J Natl Med Assoc 2017;109:33–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chin MH. Lessons from improv comedy to reduce health disparities. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:5–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chin MH. Cherry blossoms, COVID-19, and the opportunity for a healthy life. Ann Fam Med. Available: https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/handle/2027.42/163332/PPR_AFM-464-20V2.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y [Accessed 24 Dec 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]