Abstract

Objectives:

To evaluate the incidence of deprescribing of antihypertensive medication among older adults residing in VA nursing homes for long-term care and rates of deprescribing after potentially triggering events.

Design:

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting and Participants:

Long-term care residents aged 65 years and older admitted to a VA nursing home from 2006 to 2019 and using blood pressure medication at admission

Methods:

Data were extracted from the VA electronic health record, and CMS Minimum Data Set and Bar Code Medication Administration. Deprescribing was defined on a rolling basis as a reduction in the number or dose of antihypertensive medications, sustained for 2+ weeks. We examined potentially triggering events for deprescribing included low blood pressure (<90/60 mmHg), acute renal impairment (creatinine increase of 50%), electrolyte imbalance (potassium below 3.5 mEq/L, sodium decrease by 5 mEq/L), and falls.

Results:

Among 31,499 VA nursing home residents on antihypertensive medication, 70.4% had an one or more deprescribing event (median length of stay = 6 months), and 48.7% had a net reduction in antihypertensive medications over their stay. Deprescribing events were most common in the first 4 weeks after admission and the last 4 weeks of life. Among potentially triggering events, a 50% increase in serum creatinine was associated with the greatest increase in the likelihood of deprescribing over the subsequent 4 weeks: residents with this event had a 41.7% chance of being deprescribed compared to 11.5% in those who did not (risk difference = 30.3%, p<0.001). A fall in the past 30 days was associated with the smallest magnitude increased risk of deprescribing (risk difference = 3.8%, p<0.001) of the events considered.

Conclusions and Implications:

Deprescribing of antihypertensive medications is common among VA nursing home residents, especially after a potential renal adverse event.

Keywords: nursing home, hypertension, deprescribing, epidemiology, functional status

Summary:

Over 70% of long-term VA nursing home residents aged 65 years and older had a antihypertensive medication deprescribed during their stay, most commonly after a potential renal adverse event.

Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension include cautionary statements suggesting higher blood pressure targets in those who are frail or have a limited life expectancy.1–3,4 However, these guidelines largely focus on when and in whom to initiate or intensify blood pressure treatment. Thus, patients tend to accumulate medications in old age,5 with little evidence on what to do when medications are no longer of benefit. In addition to the potential for attenuated benefit, antihypertensive therapy can also result in unintended harms due to its contribution to polypharmacy, and drug-specific adverse events such as hypotension, kidney injury, electrolyte imbalance, and falls.

There is growing interest in deprescribing of antihypertensive medications, which is often defined as a reduction in the number or dose of antihypertensive drugs. Deprescribing can be used when a patient’s clinical situation evolves such that the medications benefits are outweighed by the harms, or in response to potential adverse effects. The evidence from randomized controlled trials of deprescribing antihypertensives suggests no major adverse events,6 and observational studies demonstrate that reducing or stopping antihypertensive medication is common. One recent study evaluated over 200,000 Veterans age >70 years with diabetes who were treated at a primary care clinic and found that about 19% of persons with systolic blood pressure <120 mmHg had antihypertensive treatment deprescribed.7 The prior study was limited to patients evaluated in the outpatient setting. Nursing home residents are a potentially high priority population for deprescribing due to the high prevalence of multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and frailty, which may put residents at increased risk of geriatric specific adverse events. Two studies of nursing home residents evaluated the prevalence of deprescribing in specific clinical situations. One study of nursing home residents with a fall history reported deprescribing of antihypertensive medications in 11% of the population over the following week,8 whereas a study of residents with limited life expectancy or Alzheimer’s disease reported 35% had blood pressure treatment deprescribed over one month.9

In this study, we evaluated the incidence of deprescribing of antihypertensive medication among older adults residing in VA nursing homes for long-term care. We did not restrict to residents with any specific indicating condition, as the goal of this investigation is to provide a broad descriptive analysis of the VA nursing home population. As with the previous research in this population, VA nursing home data presents an advantage because it includes chronic health conditions, blood pressure, laboratory measures, and medication use, and can be readily linked with data from acute hospital stays, outpatient visits, as well as from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Minimum Data Set, which includes data on functional status. We examined factors that differed among those who did and did not undergo a deprescribing event, as well as deprescribing rates among those with acute “triggering” events, such as incident very low blood pressure, acute renal impairment, electrolyte imbalance, and falls. This study was conducted in a cohort of over 30,000 Veterans on blood pressure lowering treatment and residing in long-term care in the period 2006–2019.

METHODS

Study Population

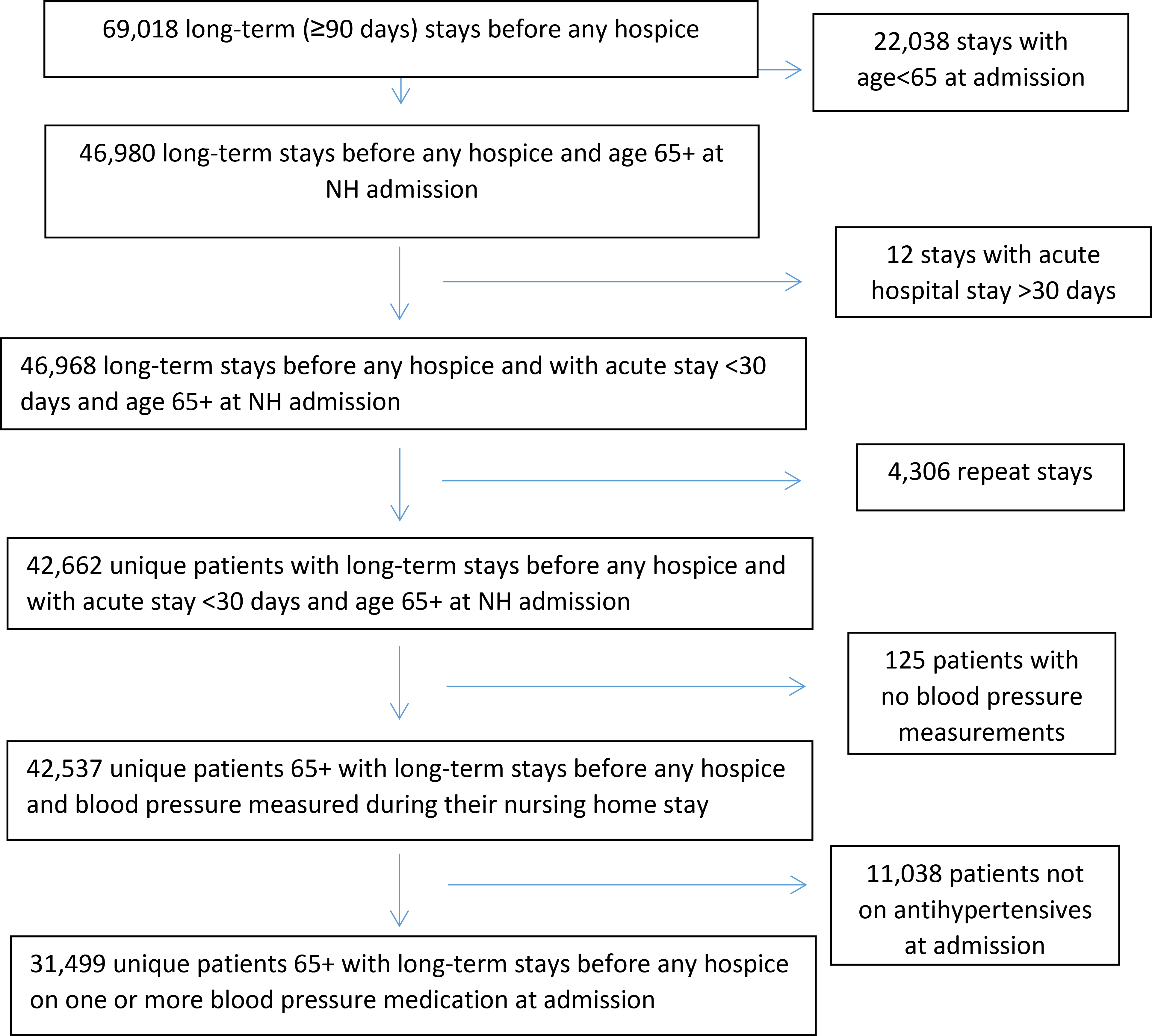

We constructed a retrospective cohort of residents in VA nursing homes, which are known as Community Living Centers (CLCs). Residents were included if they were admitted to a CLC ward between October 1, 2006, and September 29, 2019. Residents were excluded if they 1) had a CLC stay <90 days in order to exclude those undergoing post-acute rehabilitation; 2) were <65 years at admission; 3) had a >30 day acute hospital stay during their CLC stay (those with hospital stays ≤ 30 days were included); 4) had no blood pressure measures; 5) were not given at least one antihypertensive medication in the first week after admission (not on antihypertensive medications). CLCs provide both long-term and acute care; the restriction to 90 or more days (2) was intended to identify residents who received long-term care. (Figure 1) Follow-up was censored at discharge, death, entry into hospice, or on June 1, 2020. This study received institutional review board approval with a waiver of informed consent from Stanford University and the VA Palo Alto Health Care System.

Figure 1:

Flow Diagram of Study Population

Measures

The VA supports a network-wide national electronic health record with a master patient index that links all patients receiving care at all VA facilities. The primary data source for this study was the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and CLC stays were identified using validated methods.10 The CDW is a comprehensive national repository of data from the electronic medical record at all VA facilities and several other VA clinical and administrative systems.11 This repository provides detailed information on almost all data elements ascertained as part of clinical care at VA facilities since October 1999. This includes information on all inpatient and outpatient episodes of care within the VA, including related diagnoses and procedures, vital signs, laboratory values, and medications.12–14 VA Informatics and Computing Infrastructure (VINCI) provides a secure workspace for data management and analyses. We used VINCI to link to resident assessments in the Minimum Data Set (MDS), which is a federally mandated clinical assessment of all residents in Medicare or Medicaid certified nursing homes. This assessment includes a comprehensive, standardized evaluation of residents’ functional status.

Data on antihypertensive medication use were captured from the Bar-Coded Medication Administration (BCMA) data, which provide a granular assessment of each medication administered at a VA facility. Data include not only the date of administration but also the route, amount, and nurse notes regarding the medication administration. We evaluated BCMA medications given in order to account for non-use of medications prescribed but not administered. Antihypertensive medications were identified by VA Drug Classification Code. We included beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), diuretics, central alpha-blockers, vasodilators, and potassium-sparing diuretics. All medications were reviewed by two authors (MCO, CAP) to ensure that the primary indication was as a blood pressure lowering medication.

We averaged antihypertensive medication use over one week periods to account for the fact that some medications were occasionally refused or held. Average medication use was rounded to the nearest integer such that a medication that was given less than half of the days in a week would be considered to be not given. A deprescribing event was defined as a reduction in the number of antihypertensive medications or a reduction in dose of 30% or greater in comparison to the previous week, and sustained for at least two weeks. We did not include therapeutic substitution as a deprescribing event since it would not result in the change in the number of antihypertensive medications. Deprescribing events were calculated on a rolling basis with each week compared to the previous week, throughout a resident’s entire stay.

The CDW Patient domain was used to determine patient age, gender, race, and ethnicity. Data on blood pressure levels, weight, and laboratory measures were pulled from the CDW Vital Signs domain and the Managerial Cost Accounting (MCA) laboratory data domain (DSS_LAR) and averaged weekly. Chronic conditions were identified using ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes one year prior to and during the nursing home stay.15 Diagnosis codes were obtained from the CDW Inpatient and Outpatient domains. Data on falls, activities of daily living, and cognitive function were obtained from the Medicare Minimum Data Set, which changed from 2.0 to 3.0 on October 1st, 2010. We used the Cognitive Function Scale to combine the cognitive assessment tools from MDS 2.0 and 3.0 into a single, integrated, 4-level assessment of cognitive function: cognitively intact, mildly impaired, moderately impaired, and severely impaired.16

Statistical Analysis

We first described the characteristics of the cohort upon admission, and the cumulative incidence and incidence rates of deprescribing. We next evaluated changes in the rate of deprescribing over time, and estimated the proportion deprescribing after admission to the nursing home and prior to death, as these were hypothesized periods of high deprescribing rates. For the analyses prior to death, we excluded the person-weeks in which spent time outside the VA, since non-VA hospitalizations may be common near the end of life and we did not capture BCMA data outside the VA. For all subsequent analyses, we excluded deprescribing events in the last two weeks of life.

We next evaluated time-varying differences among those who did and did not have a deprescribing event. To do this, we stratified all person-weeks into those in which a resident was or was not deprescribed, and compared the most recent measure of blood pressure, laboratory value, or functional status between person-weeks with and without a deprescribing event. This analysis used the deprescribing event as the index time and looked backwards in time at measurements. If a measure was assessed more than once (as was frequent for blood pressure), we averaged over the two weeks prior. We estimated the mean/median value (continuous measures) or prevalence (categorical measures) of each measure for weeks with and without a deprescribing event and used logistic regression models with robust standard errors to account for the within person and within CLC correlation to calculate the p-value of the associations. In these regression models deprescribing was used as the dependent variable, and the blood pressure, laboratory value, or functional status measure was used as the independent variable.

Finally, we estimated the predicted probability of deprescribing in the 4 weeks following a potentially triggering clinical event that could precipitate deprescribing. This analysis used the potentially triggering event as the index time, and then looked forward over the next 4 weeks. The comparison group was those who did not have an event that could precipitate deprescribing. Events of interest included: incident low systolic BP <90 mmHg, incident low diastolic BP <60 mmHg, creatinine increase by 50%, incident potassium below 3.5 mEq/L, sodium decrease by 5 mEq/L, or fall in past 30 days. These predicted probabilities were estimated using unadjusted logistic regression models of deprescribing in the 4 weeks following an event compared with the 4 weeks following a non-event. In these models we also accounted for clustering by person (repeated measures) and CLC in the regression models and used robust standard errors.

RESULTS

Among Veterans who had long-term stays in VA nursing homes, 74.0% (31,499/42,537) were on one or more antihypertensive medication at admission. The study population of 31,499 VA nursing home residents on antihypertensive medication at admission was, on average, 78.0 ± 8.4 years of age, mostly male and non-Hispanic White. (Table 1) Blood pressure was well-controlled, with 28,235 (90.6%) residents having a blood pressure <150/90 mmHg at admission. Despite well-controlled blood pressure (mean = 129/70 mmHg), participants had a high burden of disability and morbidity. Among the residents, 94.3% had some dependence in ADLs, and 37.3% had moderate or severe cognitive impairment. The most common conditions were diabetes and coronary heart disease, which affected about half of residents at admission.

Table 1:

Characteristics of VA nursing home residents on blood pressure lowering medication at admission (2006–2019)

| Characteristic at Admission | Mean ± SD or N (%) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Age | 78.0 ± 8.4 |

| Women | 725 (2.3%) |

| White | 23,268 (79.3%) |

| Black | 5,428 (18.5%) |

| Asian | 459 (1.6%) |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 205 (0.7%) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | 1,854 (5.9%) |

| Admission Date | Nov 20, 2012 ± 3.7 yrs |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 129 ± 16 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 70 ± 8 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 124 ± 50 |

| eGFR (mg/mL/1.73m2) | 69 ± 35 |

| ADL Score = 0 | 1,764 (5.7%) |

| 1–14 | 13,824 (44.8%) |

| 15–27 | 14,142 (45.8%) |

| 28 | 1,137 (3.7%) |

| Intact Cognitive Function Score (1) | 7,444 (25.6%) |

| Mildly impaired (2) | 10,813 (37.1%) |

| Moderately impaired (3) | 6,006 (20.6%) |

| Severely impaired (4) | 4,877 (16.7%) |

| Falls in 30 days prior to Admission | 9,293 (31.0%) |

| Depression | 12,742 (40.5%) |

| Renal Disease | 10,758 (34.2%) |

| Diabetes | 15,956 (50.7%) |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 9,461 (30.0%) |

| Coronary Heart Disease | 15,110 (48.0%) |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 10,897 (34.6%) |

| Heart Failure | 12,522 (39.8%) |

| ADRD | 13,194 (41.9%) |

| Metastatic Cancer | 2,899 (9.2%) |

| 1 Antihypertensive Medication | 12,455 (39.5%) |

| 2 Antihypertensive Medications | 10,800 (34.3%) |

| 3 Antihypertensive Medications | 5,804 (18.4%) |

| 4+ Antihypertensive Medications | 2,450 (7.8%) |

| ACE/ARB | 16,310 (51.8%) |

| Beta-Blockers | 21,196 (67.3%) |

| CA Channel blockers | 10,168 (32.2%) |

| Diuretics | 14,253 (45.2%) |

| Other | 4,620 (14.7%) |

| Medication/Supplement Administrations per day | 28 (IQR: 17, 42) |

BP = blood pressure; ADL = activities of daily living; ADRD = Alzheimer’s disease and relate dementias

The median length of stay in the nursing home was a little over 6 months (195 days, IQR: 121–454 days). Of 31,499 residents, 12,559 (39.9%) died in the nursing home, and an additional 7,132/31,499 (22.6%) died within 1 year after discharge. Acute hospital stays were common, 53.7% of residents had at least one VA or non-VA hospital stay during their nursing home care. The rate of describing was 3.5/100 person-weeks (1.8 per person-year) throughout follow-up. A total of 22,187 (70.4%) participants experienced a deprescribing event at some point during the nursing home stay. Of those with one or more deprescribing events, 30.9% (6,856/22,187) had an antihypertensive medication re-started during their stay such that they did not have a net decrease in number of antihypertensive meds between CLC admission and discharge, and 69.1% (15,331/22,187) had a net decrease in antihypertensive medications between admission and discharge.

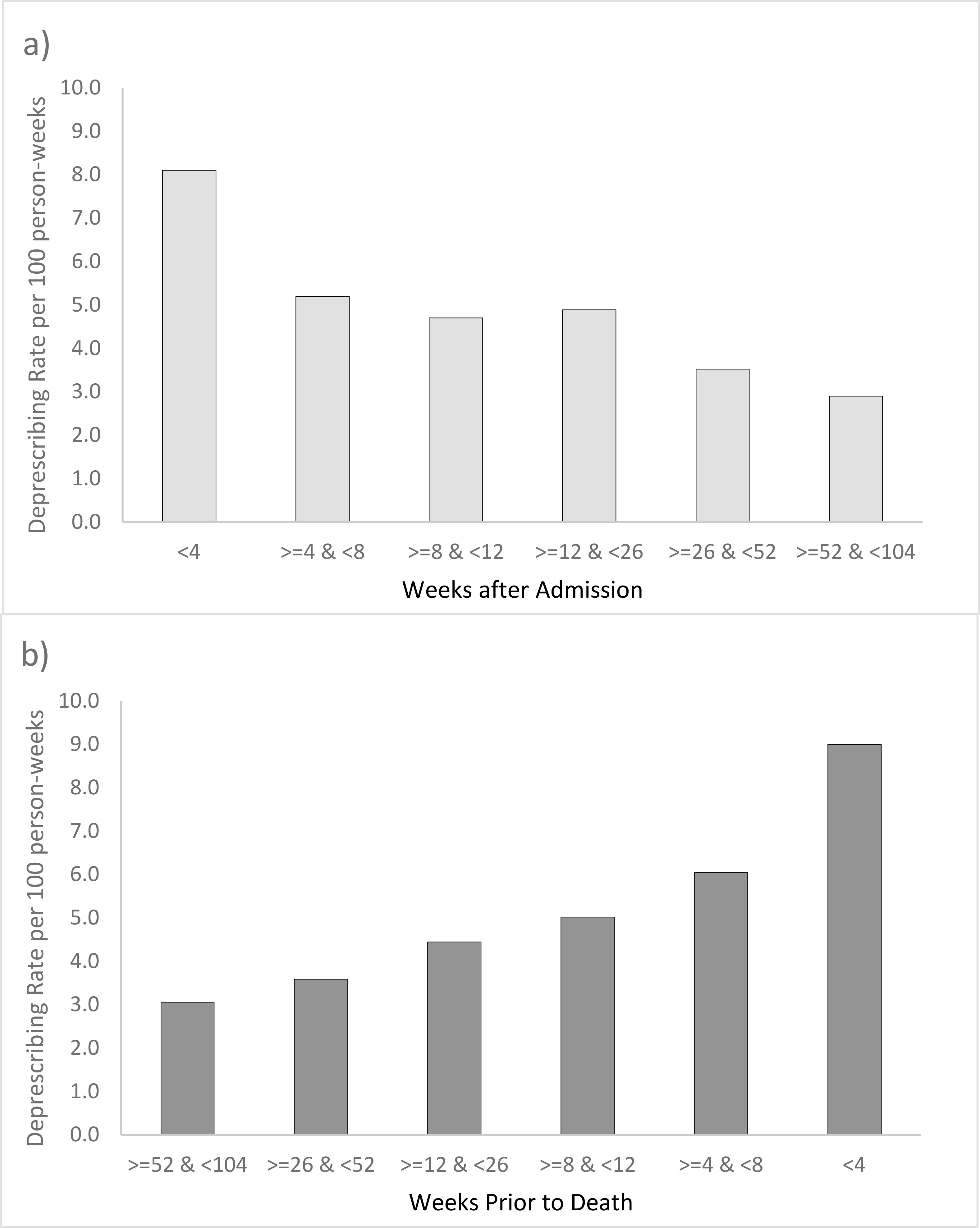

Deprescribing was most common in the first 4 weeks after admission and the last 4 weeks of life, and the rate of deprescribing was 8.1 per 100 person-weeks in the first 4 weeks after admission, and 9.0 per 100 person-weeks in the last 4 weeks of life. (Figure 2)The incidence of deprescribing fell in the months after admission.

Figure 2:

Proportion deprescribed a) after admission and b) prior to death in varying intervals of follow-up. Note that we excluded the person-weeks with any time spent outside the VA in the prior to death analysis (b) since non-VA hospitalizations may increase prior to death.

Lower systolic and diastolic blood pressure, better cognitive function, a recent fall, and lower eGFR were all associated with deprescribing. (Table 2) Higher albumin to creatinine ratio, creatinine, glucose, BUN, and potassium were all associated with greater likelihood of deprescribing, whereas lower carbon dioxide, albumin, triglycerides, and cholesterol were associated with deprescribing. However, the magnitude of differences between residents who did and did not have a deprescribing event was small for some of these laboratory measures. Those who had a deprescribing event were less likely to be in the highest quartile of medication/supplement administrations and use 4 or more antihypertensive medications. Results were essentially unchanged when we restricted to the person-weeks with no time spent outside the VA (Table S1). In an exploratory multivariable model, greater age, later admission date, higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure, severe ADL limitation, higher sodium and potassium, and greater medication use were associated with a lower odds of deprescribing (Table S2). Black race, worse cognitive function, and higher BUN were associated with a higher odds of deprescribing. There were few participants with measures of all candidate predictor variables, thus complete case analysis in the multivariable model limited the sample size to 85,267 (5%) person-weeks from a total of 1,561,761 possible.

Table 2:

Time-varying values of patient characteristics at most recent measure* prior to a deprescribing event

| Characteristic | Deprescribing (54,942 person weeks) | No Deprescribing (1,506,189 person weeks) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD or N (%) | |||

|

| |||

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 126 ± 16 | 131 ± 15 | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 68 ± 8 | 70 ± 8 | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP ≥ 150 mmHg | 7.8% | 10.4% | p-for trend |

| 130–<150 mmHg | 29.1% | 39.8% | <0.001 |

| 110–<130 mmHg | 48.0% | 42.6% | |

| 90–<110 mmHg | 14.7% | 7.0% | |

| <90 mmHg | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| Diastolic BP ≥90 mmHg | 0.7% | 1.2% | p-for trend |

| 80–<90 mmHg | 6.6% | 10.3% | <0.001 |

| 70–<80 mmHg | 31.4% | 40.1% | |

| 60–<70 mmHg | 46.1% | 39.4% | |

| <60 mmHg | 15.1% | 9.0% | |

| ADL Score = 0 | 6.7% | 7.3% | p-for trend |

| 1–14 | 42.9% | 42.4% | 0.90 |

| 15–27 | 46.3% | 45.5% | |

| 28 | 4.1% | 4.8% | |

| Intact Cognitive Function Score (1) | 18.3% | 21.6% | p-for trend |

| Mildly impaired (2) | 32.3% | 30.7% | <0.001 |

| Moderately impaired (3) | 24.9% | 24.6% | |

| Severely impaired (4) | 24.6% | 23.2% | |

| Fall in last 30 days | 23.3% | 21.4% | <0.001 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73m2) | 64 ± 34 | 69 ± 33 | <0.001 |

| Albumin to Creatinine Ratio† (μg/mg) | 33 (6, 167) | 24 (5, 126) | 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.57 ± 1.73 | 1.38 ± 1.60 | <0.001 |

| CO2 (mEq/L) | 27.2 ± 4.1 | 27.4 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.16 ± 0.58 | 3.30 ± 0.54 | <0.001 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 120 ± 76 | 126 ± 80 | <0.001 |

| Total Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 135 ± 35 | 140 ± 35 | <0.001 |

| LDL-Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 73 ± 29 | 75 ± 29 | <0.001 |

| HDL-Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 38.8 ± 12.7 | 39.1 ± 12.3 | <0.001 |

| HbA1C (%) | 6.6 ± 1.3 | 6.6 ± 1.2 | 0.11 |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 129 ± 51 | 127 ± 52 | <0.001 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 31 ± 17 | 26 ± 14 | <0.001 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138.0 ± 5.1 | 138.5 ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.28 ± 0.49 | 4.25 ± 0.45 | <0.001 |

| Top Quartile of Medication/Supplement Use | 21.1% | 27.4% | <0.001 |

| 2 Antihypertensive medications | 32.8% | 34.5% | p-for trend <0.001 |

| 3 Antihypertensive medications | 19.6% | 15.7% | |

| 4+ Antihypertensive medications | 6.5% | 10.5% | |

This analysis used the deprescribing event as the index time and looked backwards in time at the most recent value of the measure of interest.

median (IQR)

BP = blood pressure; ADL = activities of daily living; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; CO2 = carbon dioxide; LDL = low density lipoprotein; HDL = high density lipoprotein; HbA1C = hemoglobin A1C, BUN = blood urea nitrogen

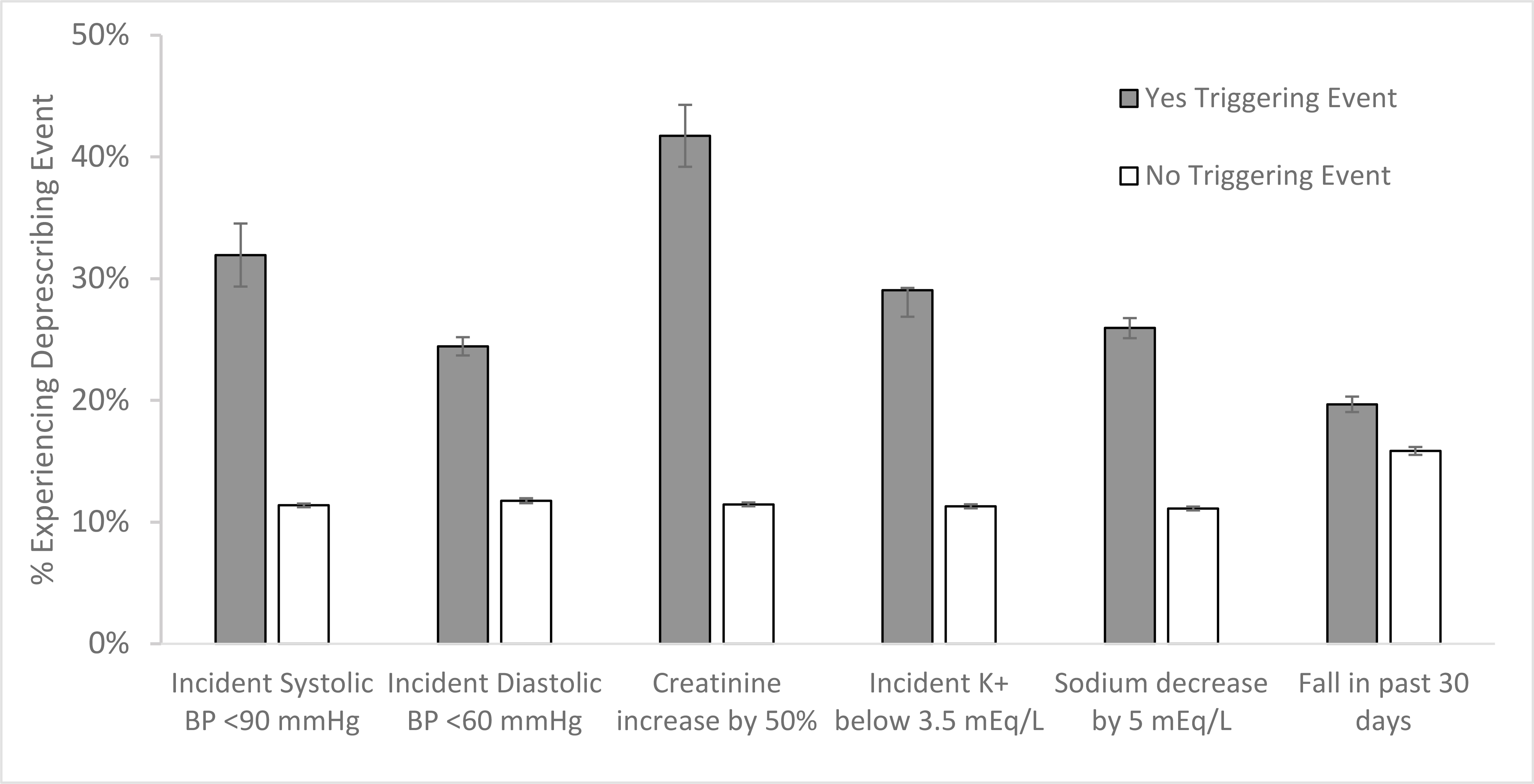

Most of the prespecified events that may trigger a deprescribing event were rare: incident low systolic BP <90 mmHg, incident low diastolic BP <60 mmHg, creatinine increase of 50%, potassium below 3.5 mEq/L, sodium decrease by 5 mEq/L, fall in past 30 days occurred 0.13, 1.84, 0.13, 0.48, and 0.85 per 100 person-weeks, respectively. A fall in the past 30 days was more common and was reported at the rate of 20.4 per 100 person-weeks. All events were associated with a greater probability of deprescribing in the following 4 weeks. (Figure 3) The greatest effect was observed for an increase in creatinine by at least 50%; residents with this event had a 41.7% chance of being described compared to 11.5% in those who did not (risk difference = 30.3%, p<0.001). A fall in the past 30 days was associated with the smallest magnitude increased risk of deprescribing (risk difference = 3.8%, p<0.001) of the events considered. Table S3 shows the proportion of residents with BCMA data available after a potentially triggering event.

Figure 3:

Probability of deprescribing in the following 4 weeks after a potentially triggering event. This analysis used the triggering event as the index time and then evaluated the probability of deprescribing over the next 4 weeks.

DISCUSSION

Among Veterans who had long-term stays in VA nursing homes, 74% were on one or more antihypertensive medications at admission, and over 90% of these patients had blood pressure <150/90 mmHg. During the course of their nursing home stay, over two-thirds (70.4%) of residents had one or more deprescribing event and such deprescribing events occurred most commonly in the four weeks after admission or the last four weeks of life. However, deprescribing was transient for many residents and only 48.7% had a net reduction in antihypertensive medication over their stay. Worse health was associated with an increased likelihood of deprescribing. However, deprescribing rates were modest after clinical events that often trigger deprescribing. Rates were highest after potential acute kidney injury, with over 40% of residents having one or more medication removed after such an event.

Our study contributes to the literature describing the incidence and predictors of deprescribing. A recent study from Vu et al. over a similar period (2009–2015) in Veterans residing in nursing home reported a cumulative incidence of 35% over 30 days among those with limited life expectancy or advanced dementia for deprescribing events sustained for 14 days.9 This is a similar proportion than observed in our population, which ranged from 11–42% depending on the presence of an indicating event. Another investigation in Veterans residing in nursing homes found 11% had antihypertensive drug therapy deintensified (dose reduction or medication discontinuation) within one week after a fall, is slightly lower than our estimates, although this could be due to the fact that we evaluated deprescribing over a longer period after a fall. We found that deprescribing was less common in residents with a high medication burden, perhaps reflecting the patients’ actual or perceived need for greater medication use. A medication review may help identify any unnecessary medications in these high-use patients.

The clinically appropriate way to manage blood pressure treatment in the setting of adverse events is complex and is influenced by whether the prescribing clinician believes the event to be related to treatment. The events examined in this study, hypotension, electrolyte imbalance, acute renal failure, and falls, are multifactorial in nature and are not uncommon in nursing home populations. Whether deprescribing can reduce the risk of future events is unknown. Song et al. examined this in the nursing home population and found that among those with a history of falls, deintensification of antihypertensive therapy was associated with a lower risk of recurrent falls, but an increased risk of death.8 It remains uncertain as to whether the increased risk of death was due to confounding by indication, as deprescribing may be most common in the last month of life.

A recent systematic review found that the evidence from randomized controlled trials of deprescribing has been limited by small studies and low event rates.6 The authors found a low certainty of evidence for no increased risk of myocardial infarction, stroke, death, or adverse events.6 One recent trial, the Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in Elderly People (DANTE) trial randomized community dwelling adults aged 75 years and older without cardiovascular disease and with mild cognitive impairment to discontinuation or continuation of antihypertensive treatment and found no differences in cognitive decline and no change in other adverse events.17 Another trial, the Optimising Treatment for Mild Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly (OPTIMISE) study randomized adults aged 80 years and older to a removal of one medication and found the intervention was noninferior with regard to systolic blood pressure control, and no difference in secondary endpoints.18 Taken together, the evidence presents no evidence of harm of deprescribing, which may be reassuring to patients and providers who are interested in stopping or reducing antihypertensive medications. However, the low certainty of evidence regarding the benefits and harms of deprescribing highlights the importance of shared decision-making that accounts for patient preferences and values.

The vast majority of literature on blood pressure medication has focused on the initiation and intensification of therapy. Moreover, nursing home residents have been excluded in nearly all studies of blood pressure treatment and control. The major clinical practice guidelines have recognized those with reduced functional status, dementia, and those residing in long-term care as high priority populations for further evidence. Our work and that of others presents the first epidemiologic investigations of deprescribing.

A major strength of VA data is the ability to link data from the nursing home with data from acute hospital stays, outpatient visits, and functional status from the Minimum Data Set. Moreover, antihypertensive medication use was obtained from barcode medication administration data, and thus can accurately capture actual use of medications compared with data on prescriptions or fills. This also allows us to evaluate week-to-week changes in administered medications, and evaluate potential changes after an event that may trigger a deprescribing event. However, our study has limitations that should be considered. The VA population does not represent the U.S. population of nursing home residents, and has a disproportionately high ratio of men to women. Additionally, our study population had a high degree of comorbidity, and some antihypertensives are prescribed for conditions other than hypertension (e.g. beta blockers for atrial fibrillation, diuretics for heart failure). This limits our ability to evaluate the extent to which a drug may have been continued for these other effects (e.g. rate control, volume overload) in relation to blood pressure lowering. And we were unable to estimate deprescribing rates among those residents who died or were discharged in the 4 weeks after a potentially triggering event, so these results can only be generalized to residents who survive and remain in long term care. Additionally, electronic health records have known misclassification and measurement error in the classification of chronic conditions from ICD codes. Moreover, we only included chronic conditions diagnosed in the VA acute care or outpatient setting, and thus may have missed chronic conditions that were solely treated by a non-VA provider. However we believe that this situation would be rare as any chronic condition would need to be identified in the CLC record in order to support follow-up care in the nursing home. We interpret our multivariable models with caution since few participants had all variables assessed and the degree of missingness limited our ability to use multiple imputation. Finally, blood pressure measurements taken in the clinic differ from those taken in research settings, and are generally taken with less rigorous methods. The volume of blood pressure measurements would reduce concerns about random error, but systematic error may remain.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

In conclusion, blood pressure medication use is common in a VA nursing home population and blood pressures are well-controlled. Deprescribing is frequent during the nursing home stay, but only occurs between 10–30% of the time in the month after deprescribing triggering events. A better understanding of the consequences of deprescribing in nursing home residents can help guide the management of blood pressure in this complex population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This research was funded by the National Institute on Aging (R56AG055576, RF1AG062568). SJL’s effort was supported in part by VA HSR&D (IIR 15–434) and NIA (R01AG057751). ZAM’s effort was supported in part by NIA (K76AG059929). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Veterans’ Health Association.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

CAP serves as the Chief Medical Officer for Cricket Health, Inc. MCO serves as a consultant for Cricket Health, Inc.

MAS and SJL receive honoraria as authors on UpToDate

References:

- 1.Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ, et al. ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents. Circulation 2011;123(21):2434–2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal 2013;34(28):2159–2219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, Rich R, et al. Pharmacologic Treatment of Hypertension in Adults Aged 60 Years or Older to Higher Versus Lower Blood Pressure Targets: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians and the American Academy of Family Physicians. Annals of internal medicine 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cassel CK, Guest JA. Choosing wisely: helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA 2012;307(17):1801–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Charlesworth CJ, Smit E, Lee DS, et al. Polypharmacy Among Adults Aged 65 Years and Older in the United States: 1988–2010. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2015;70(8):989–995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reeve E, Jordan V, Thompson W, et al. Withdrawal of antihypertensive drugs in older people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020;6:CD012572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sussman JB, Kerr EA, Saini SD, et al. Rates of Deintensification of Blood Pressure and Glycemic Medication Treatment Based on Levels of Control and Life Expectancy in Older Patients With Diabetes Mellitus. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(12):1942–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Song W, Intrator O, Lee S, et al. Antihypertensive Drug Deintensification and Recurrent Falls in Long-Term Care. Health Serv Res 2018;53(6):4066–4086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vu M, Sileanu FE, Aspinall SL, et al. Antihypertensive Deprescribing in Older Adult Veterans at End of Life Admitted to Veteran Affairs Nursing Homes. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021;22(1):132–140 e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scott WJ, Gonsoulin M, Ramanthan D, et al. Identifying CLC Stays in CDW. The Researcher’s Notebook; no. 12. Hines, IL: VA Information Resource Center; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW); https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/vinci/cdw.cfm. Accessed July 2, 2021.

- 12.Cowper DC, Kubal JD, Maynard C, et al. A primer and comparative review of major US mortality databases. Ann Epidemiol 2002;12(7):462–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hynes DM, Cowper D, Kerr M, et al. Database and informatics support for QUERI: current systems and future needs. Quality Enhancement Research Initiative. Med Care 2000;38(6 Suppl 1):I114–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murphy PA, Cowper DC, Seppala G, et al. Veterans Health Administration inpatient and outpatient care data: an overview. Eff Clin Pract 2002;5(3 Suppl):E4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care 2005;43(11):1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, et al. The Minimum Data Set 3.0 Cognitive Function Scale. Med Care 2017;55(9):e68–e72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moonen JE, Foster-Dingley JC, de Ruijter W, et al. Effect of Discontinuation of Antihypertensive Treatment in Elderly People on Cognitive Functioning--the DANTE Study Leiden: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175(10):1622–1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheppard JP, Burt J, Lown M, et al. Effect of Antihypertensive Medication Reduction vs Usual Care on Short-term Blood Pressure Control in Patients With Hypertension Aged 80 Years and Older: The OPTIMISE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2020;323(20):2039–2051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.