Abstract

Background:

Inhibition of the renin angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) improves survival and reduces adverse cardiac events in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, but the benefit is not well-defined following left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

Methods:

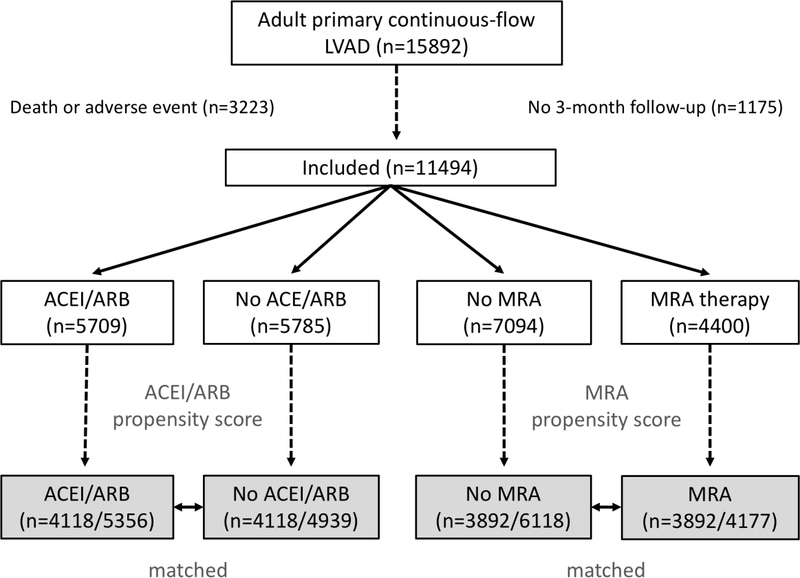

We analyzed the ISHLT IMACS registry for adults with a primary, continuous-flow LVAD from January 2013 to September 2017 who were alive at post-operative month 3 without a major adverse event, and categorized patients according to treatment an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI/ARB) or mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA). Propensity score matching was performed separately for ACEI/ARB versus none (n=4118 each) and MRA versus none (n=3892 each).

Results:

Of 11,494 patients included, 50% were treated with ACEI/ARB and 38% with MRA. Kaplan-Meier survival was significantly better for patients receiving ACEI/ARB (p<0.001) but not MRA (p=0.31). In Cox proportional hazards analyses adjusted for known predictors of mortality following LVAD, ACEI/ARB use (HR 0.81 [95% CI 0.71–0.93], p<0.0001) but not MRA use (HR 1.03 [95% CI 0.88–1.21], p=0.69) was independently associated with lower mortality. Among patients treated with an ACEI/ARB, there was a significantly lower unadjusted risk of cardiovascular death (p<0.001), gastrointestinal bleeding (p=0.01), and serum creatinine (p<0.001). MRA therapy was associated with lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (p=0.01) but higher risk of hemolysis (p<0.01). Potential limitations include residual confounding and therapy crossover.

Conclusion:

These findings suggest a benefit for ACEI/ARB therapy in patients with heart failure after LVAD implantation.

Keywords: heart-assist devices, heart failure, renin angiotensin aldosterone system, mortality

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) leads to reduced effective arterial volume with consequent activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), ultimately resulting in vasoconstriction, volume retention, and pathologic myocardial remodeling. Neurohormonal modulators including angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors/angiotensin receptor blockers (ACEI/ARBs), angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors, and mineralocorticoid antagonists (MRAs) decrease mortality, sudden cardiac death, and hospitalization among patients with HF.(1) LVAD therapy improves survival in select patients with advanced heart failure. Nevertheless, cardiovascular events such as arrhythmias, right heart failure, and stroke remain major causes of morbidity and mortality during the long-term support of patients with LVADs, and this population has grown over time.(2, 3)

It remains uncertain whether guideline-directed medical therapy is beneficial following mechanical unloading with left ventricular assist device (LVAD). Utilization of RAAS antagonists is generally low prior to LVAD implantation but increases afterward, plateauing by 3 months.(4) A small, single-center observational study compared patients treated with guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT which included RAAS inhibition) after LVAD versus not and found that GDMT was associated with reduced left ventricular diameter, improved functional status, and decreased cardiovascular death or hospitalization.(5) We sought to determine the association specifically between RAAS inhibition post-implant and mortality in a large, multi-center, international population of patients with continuous-flow LVADs.

Methods

Patient selection

Data were prospectively collected and maintained in the ISHLT Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (IMACS) registry. We included adult patients from January 2013 to September 2017 with a primary continuous-flow LVAD who were alive at three months following device implantation. Patients with a right ventricular assist device, biventricular assist device, stroke, device exchange, or device malfunction during the first three months were excluded. Patients were categorized into cohorts by whether they received ACEI/ARB therapy or MRA therapy at the three-month follow-up visit post-implant. The primary outcome measured was all-cause mortality, censored for transplant or explant for recovery as competing risks. Secondary outcomes during follow-up included cardiovascular death (any circulatory cause excluding stroke), stroke (ischemic, hemorrhagic, or other), pump thrombosis (hemolysis), gastrointestinal bleeding (upper, lower, or unknown), dialysis, and serum creatinine. For recurrent events, only the first was counted.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical and continuous baseline characteristics were compared with Chi-square and Wilcoxon tests respectively, with a two-tailed p<0.05 threshold for significance. Separate propensity scores were generated for ACEI/ARB and MRA treatment post-implant as the dependent variable, with covariates considered relevant a priori. Baseline variables included age, sex, severe diabetes (INTERMACS definition), INTERMACS profile, implant strategy, and pre-implant RAAS inhibitor use. Post-implant variables at three-months included medications (ACEI/ARB, beta-blocker, calcium channel blocker, loop diuretic, MRA, and phosphodiesterase inhibitor), labs (blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, potassium, and sodium), and post-implant dialysis.(4, 6, 7) Patients were selected according to propensity score with 1:1 matching without replacement using the nearest neighbor method and a caliper width of 0.2.(8) Distribution of propensity scores and improvement in standard mean differences were examined for matched and unmatched cohorts. All variables had <10% missing data, except right atrial pressure which had 10% missing. About 70% of eligible patients were matched. Kaplan-Meier survival and freedom from event curves for each treatment cohort were constructed and compared by the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards regression was applied to estimate hazard ratios (HR) for survival with treatment class as the independent variable, censoring for transplant and device explant for recovery. Models were adjusted for beta-blocker use, age, sex, body-mass index, device strategy, INTERMACS profile, prior cardiac surgery, vascular disease, smoking, blood urea nitrogen (post-implant), creatinine (post-implant), and bilirubin (post-implant) based on prior literature.(2, 3) Continuous variables were modeled using restricted Cubic splines with four knots to account for non-linear relationships, and HRs were calculated based on change over the interquartile range (75th to 25th percentile values) for continuous variables. Model assumptions were checked by examining Schoenfeld residuals. All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.1.0 (R Development Core Team) with MatchIt 4.1.0 package, operating under Ubuntu 20.04.2 LTS. This was an investigator-initiated and -analyzed project using IMACS de-identified data. The findings herein represent those of the authors and not the IMACS collectives.

Results

Cohort Characteristics

Of 12,669 adult patients with a primary continuous-flow LVAD who met inclusion criteria, 11,494 had follow-up data and were included (Figure 1). Median follow up was 16 months. At three months post-implant, 50% (5,709) of patients were on ACEI/ARB therapy, 38% (4,400) were on MRA therapy, and 23% (2,624) were on both. Prior to matching, patients treated with either ACEI/ARB or MRA (Table S1) were overall more likely to have younger age, female gender, higher BMI, non-ischemic etiology, bridge-to-transplant or bridge-to-decision strategy, less acute INTERMACS profile, lower BUN, lower creatinine, lower bilirubin, and prior use of RAAS therapies. Propensity scores were generated separately for likelihood of receiving each therapy at three months post-implant, with 4118 matched cases for ACEI/ARB therapy and 3892 matched cases for MRA therapy. Matching substantially improved standardized mean difference among variables in both cohorts to <10% (Table S2). The distribution of scores between cases and controls were similar (Figures S1a and S1b). Baseline characteristics of matched cohorts are listed in Table 1. Among the matched cohorts, there were statistically significant but clinically very small residual differences between matched groups in age, BMI, centrifugal/axial flow, etiology, cardiac resynchronization therapy, prior cardiac surgery, pre-implant laboratory values, post-implant laboratory values, intra-aortic balloon pump use, right atrial pressure, and other medical therapies. At 12 months, 47% of the matched ACEI/ARB cohort remained on therapy while 18% of the control group were on an ACEI/ARB. Likewise, by 12 months, 41% of the matched MRA cohort remained on therapy and 10% of the control group was on MRA therapy.

Figure 1. Patient selection.

Cases were selected from the IMACS Registry January 2013 – September 2017. Patients who died or experienced a major adverse within 3 months of implant were excluded and separate propensity scores generated for each therapy. ACEI – angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB – angiotensin receptor blocker, MRA – mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

Table 1.

Baseline matched cohort characteristics

| Variable | No ACEI/ARB n=4118 |

ACEI/ARB n=4118 |

P | No MRA n=3892 |

MRA n=3892 |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-implant Clinical | ||||||

| Age (years) | 59 [50–67] | 58 [48–66] | <0.001 | 57 [48–65] | 57 [45–64] | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 79 (3255/4118) | 79 (3246/4118) | 0.81 | 79 (3060/3892) | 78 (3033/3892) | 0.46 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 [23.9–32.3] | 27.6 [23.7–32.4] | 0.82 | 27.5 [23.7–32.3] | 28.1 [24.1–33.0] | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (severe) | 10 (394/4118) | 10 (395/4118) | 0.97 | 10 (374/3892) | 10 (377/3892) | 0.91 |

| Centrifugal device | 29 (1203/4118) | 29 (1207/4118) | 0.92 | 29 (1143/3892) | 33 (1273/3892) | 0.001 |

| INTERMACS profile | 0.35 | 0.94 | ||||

| 1 | 15 (611/4118) | 14 (574/4118) | 13 (523/3.892) | 13 (520/3892) | ||

| 2 | 35 (1429/4118) | 34 (1387/4118) | 34 (1331/3892) | 34 (1342/3892) | ||

| 3 | 35 (1440/4118) | 36 (1493/4118) | 36 (1412/3892) | 37 (1423/3892) | ||

| 4–7 | 15 (638/4118) | 16 (664/4118) | 16 (626/3892) | 16 (607/3892) | ||

| Ischemic | 44 (1818/4118) | 42 (1734/4118) | 0.06 | 42 (1630/3892) | 38 (1481/3892) | <0.001 |

| Non-ischemic | 52 (2126/4118) | 53 (2202/4118) | 0.09 | 54 (2089/3892) | 57 (2213/3892) | <0.01 |

| LVEF <20% | 69 (2705/3899) | 71 (2742/3873) | 0.17 | 69 (2525/3634) | 71 (2581/3651) | 0.26 |

| NYHA | 0.17 | 0.85 | ||||

| II | 1 (47/4106) | 1 (49/4105) | 1 (47/3870) | 1 (46/3881) | ||

| III | 17 (685/4106) | 18 (743/41 05) | 18 (700/3870) | 17 (668/3881) | ||

| IV | 79 (3226/4106) | 76 (3137/4105) | 77 (2974/3870) | 78 (3019/3881) | ||

| Prior cardiac surgery | 32 (1279/4032) | 28 (1130/3970) | 0.001 | 29 (1102/3764) | 29 (1059/3698) | 0.54 |

| Pulmonary disease | 10 (396/4118) | 8 (340/4117) | 0.03 | 9 (347/3890) | 9 (357/3891) | 0.69 |

| Renal disease | 24 (963/4038) | 18 724/4004) | <0.001 | 21 (782/3767) | 20 (727/3722) | 0.19 |

| Smoking (current) | 5 (203/4103) | 5 (202/4094) | 0.98 | 5 (198/3874) | 5 (187/3867) | 0.58 |

| Strategy | 0.03 | 0.61 | ||||

| Bridge to recovery | 0 (4/4118) | 0 (16/4118) | 0 (9/3892) | 0 (12/3892) | ||

| Bridge to transplant | 27 (1094/4118) | 28 (1142/4118) | 29 (1141/3892) | 30 (1180/3892) | ||

| Bridge to decision | 26 (1068/4118) | 27 (1097/4118) | 27 (1066/3892) | 28 (1085/3892) | ||

| Destination | 47 (1941/4118) | 45 (1854/4118) | 43 (1669/3892) | 41 (1606/3892) | ||

| Vascular disease | 4 (181/4118) | 4 (159/4117) | 0.22 | 4 (151/3892) | 4 (146/3891) | 0.77 |

| Pre-implant Labs | ||||||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.5 [3.0–3.8] | 3.5 [3.1–3.9] | <0.001 | 3.5 [3.1–3.9] | 3.5 [3.1–3.9] | <0.001 |

| ALT/SGPT | 27 [18–46] | 28 [19–46] | 0.38 | 27 [18–45] | 28 [19–46] | 0.08 |

| AST/SGOT | 28 [21–42] | 28 [20–41] | 0.08 | 27 [20–41] | 28 [21–41] | 0.31 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | 25 [18–36] | 23 [17–32] | <0.001 | 24 [17–34] | 23 [17–33] | 0.07 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.28 [1.00–1.63] | 1.20 [0.99–1.50] | <0.001 | 1.20 [0.98–1.52] | 1.20 [0.95–1.50] | 0.01 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.2 [9.7–12.7] | 11.5 [10.0–12.9] | <0.001 | 11.5 [9.9–12.8] | 11.5 [10.0–12.9] | 0.29 |

| INR | 1.20 [1.10–1.40] | 1.20 [1.10–1.39] | <0.001 | 1.2 [1.1–1.4] | 1.2 [1.1–1.4] | <0.001 |

| Platelets (x103/μL) | 188 [142–239] | 189 [143–241] | 0.50 | 186 [141–238] | 192 [145–245] | <0.01 |

| Sodium (mEq/dL) | 135 [132–138] | 136 [132–138] | 0.01 | 136 [132–138] | 135 [132–138] | <0.001 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.0 [0.6–1.5] | 0.9 [0.6–1.5] | <0.001 | 0.9 [0.6–1.5] | 1.0 [0.7–1.6] | <0.001 |

| Post-implant Labs | ||||||

| BUN (mg/dL) | 19 [14–26] | 19 [14–25] | 0.01 | 19 [14–25] | 19 [14–25] | 0.06 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.10 [0.90–1.40] | 1.10 [0.90–1.30] | <0.001 | 1.10 [0.89–1.35] | 1.10 [0.90–1.32] | 0.80 |

| Potassium (mmol/dL) | 4.1 [3.8–4.4] | 4.2 [3.9–4.5] | <0.001 | 4.1 [3.9–4.4] | 4.2 [3.9–4.4] | 0.08 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 138 [136–140] | 138 [136–140] | 0.03 | 139 [137–140] | 138 [136–139] | <0.001 |

| Pre-implant Support | ||||||

| ECMO | 5 (191/4110) | 4 (172/4107) | 0.31 | 4 (163/3874) | 4 (149/3884) | 0.41 |

| Dialysis/ultrafiltration | 3 (126/4117) | 2 (79/4118) | <0.001 | 2 (90/3892) | 2 (82/3891) | 0.54 |

| IABP | 31 (1257/4111) | 28 (1147/4108) | 0.01 | 27 (1060/3874) | 29 (1124/3885) | 0.12 |

| Inotrope | 82 (3386/4118) | 82 (3357/4118) | 0.41 | 81 (3168/3892) | 82 (3190/3892) | 0.52 |

| Ventilator | 12 (477/4117) | 11 (456/4117) | 0.47 | 10 (401/3892) | 11 (444/3892) | 0.12 |

| Hemodynamics | ||||||

| RA (mmHg) | 12 [7–17] | 11 [7–16] | <0.001 | 12 [7–17] | 12 [7–16] | 0.67 |

| PA systolic (mmHg) | 50 [40–60] | 49 [39–60] | 0.48 | 50 [39–60] | 50 [40–60] | 0.38 |

| PA diastolic (mmHg) | 25 [19–31] | 24 [19–30] | 0.18 | 25 [19–31] | 25 [19–30] | 0.26 |

| PCW (mmHg) | 25 [19–31] | 24 [18–31] | 0.11 | 25 [18–31] | 25 [19–31] | 0.82 |

| Cardiac output (L/min) | 4.0 [3.2–5.0] | 4.0 [3.2–4.9] | 0.11 | 4.0 [3.2–5.0] | 4.0 [3.2–5.0] | 0.29 |

| Pre-implant Therapies | ||||||

| ACEI | 19 (796/4090) | 28 (1160/4089) | <0.001 | 28 (1060/3848) | 26 (1007/3851) | <0.001 |

| ARB | 8 (330/4086) | 11 (432/4087) | <0.001 | 10 (393/3841) | 10 (387/3844) | <0.01 |

| MRA | 41 (1677/4089) | 44 (1792/4090) | 0.01 | 40 (1540,3846) | 54 (2094/3850) | <0.001 |

| Beta-blocker | 48 (1956/4089) | 51 (2102/4089) | 0.01 | 52 (1996/3846) | 51 (1967/3850) | 0.87 |

| CRT | 28 (1153/4118) | 27 (1115/4118) | <0.001 | 26 (1010/3892) | 30 (1163/3892) | <0.001 |

| Post-implant therapies | ||||||

| ACEI | 0 (0/4118) | 79 (3267/4118) | 46 (1780/3892) | 45 (1751/3892) | 0.22 | |

| ARB | 0 (0/4118) | 23 (954/4118) | 12 (454/3892) | 14 (555/3892) | <0.001 | |

| MRA | 38 (1572/4118) | 42 (1723/4118 | 0.001 | 0 (0/3892) | 100 (3892/3892) | |

| Amiodarone | 47 (1918/4118) | 44 (1816/4118) | 0.03 | 42 (1648/3892) | 45 (1735/3892) | 0.10 |

| Beta-blocker | 62 (2543/4118) | 65 (2658/4118) | 0.02 | 66 (2555/3892) | 66 (2580/3892) | 0.83 |

| Calcium channel | 11 (452/4118) | 11 (441/4118) | 0.01 | 10 (399/3892) | 10 (370/3892) | 0.01 |

| Hydralazine | 20 (839/4118) | 19 (773/4118) | <0.01 | 18 (711/3892) | 18 (695/3892) | 0.01 |

| Loop diuretic | 72 (2979/4118) | 71 (2921/4118) | 0.37 | 74 (2878/3892) | 75 (2910/3892) | 0.68 |

| PDE inhibitor | 23 (941/4118) | 22 (906/4118) | 0.01 | 23 (888/3892) | 23 (900/3892) | 0.01 |

Data represent % (number) or median [interquartile range]. ACEI – angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ALT – alanine aminotransferase, AST – aspartate aminotransferase, ARB – angiotensin receptor blocker, BMI – body mass index, BP – blood pressure, BUN – blood urea nitrogen, CRT – cardiac resynchronization therapy, ECMO – extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, IABP – intraaortic balloon pump, LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction, MRA – mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, NYHA – New York Heart Association, PA – pulmonary artery pressure, PCW – pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, PDE – phosphodiesterase, RA – right atrial pressure

Survival

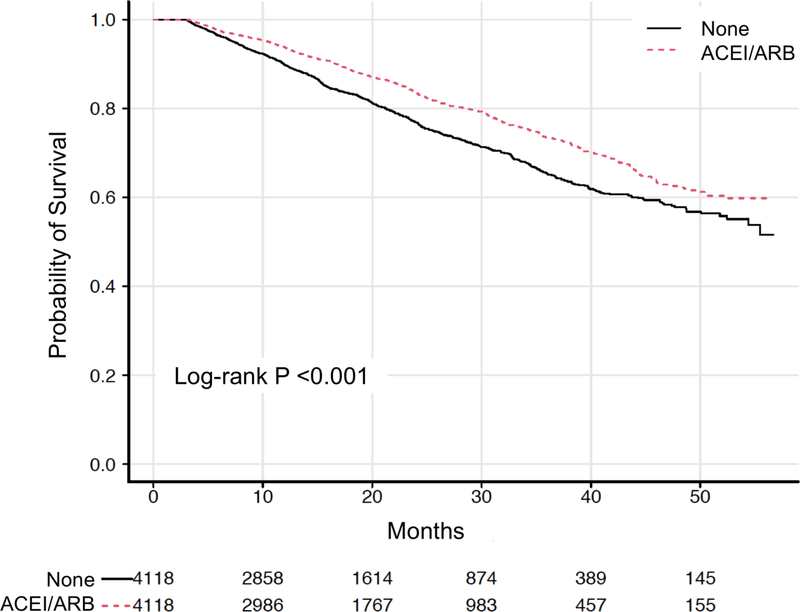

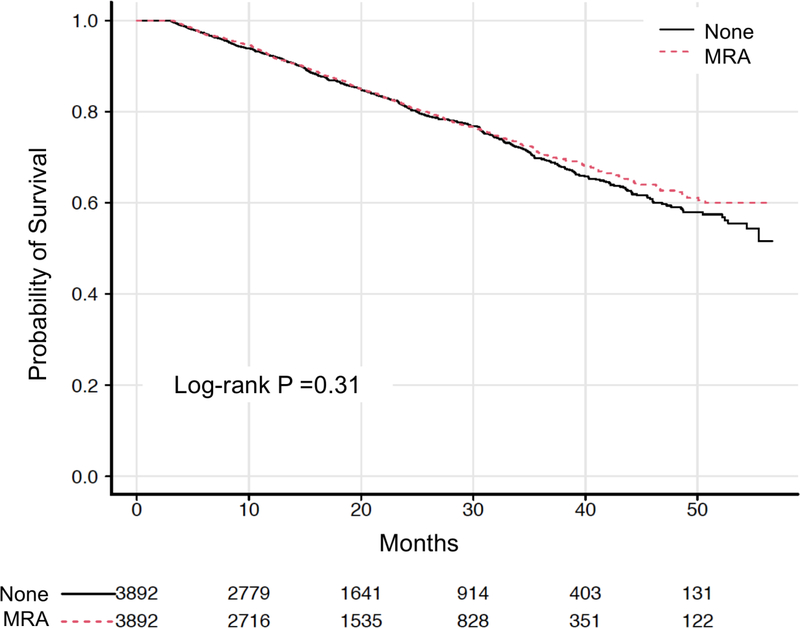

Kaplan-Meier survival was significantly better in patients treated with ACEI/ARB post-implant in both unmatched (Figure S2a, p<0.001) and propensity-matched cohorts (Figure 2a, hazard ratio [HR] 0.72 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.65–0.79], p<0.001). For ACEI/ARB treatment, the estimated survival probability at 12 months (conditional on three-month survival) was 0.94 (CI 0.93–0.95) versus 0.90 (CI 0.89–0.91) for controls and at 24 months was 0.84 (CI 0.82–0.85) versus 0.77 (CI 0.75–0.79) for controls. Survival advantage remained after stratification by median creatinine (Figure 3). To adjust for established predictors of mortality, Cox proportional hazards regression was performed (Table 2, Table S3). Therapy with ACEI/ARB post-implant was independently associated with lower mortality (hazard ratio [HR] 0.81 [CI 0.71–0.93], p<0.0001). Other variables associated with mortality included age (HR 1.33 [CI 1.12–1.57], p<0.0001), beta-blocker use (HR 0.84 [CI 0.75–0.94], p<0.01), BUN (HR 1.21 [CI 1.06–1.38], p<0.0001), creatinine (HR 1.03 [CI 0.89–1.18], p=0.04), strategy (bridge-to-transplant HR 0.72 [CI 0.61–0.85] and possible bridge-to-transplant HR 0.83 [CI 0.72–0.95] versus destination therapy), p=0.001), prior cardiac surgery (HR 1.16 [CI 1.04–1.31], p=0.01), and smoking (HR 1.38 [CI 1.10–1.72], p<0.01). Although there was significantly more MRA use post-implant in the ACEI/ARB matched cohort, this was not a significant predictor (HR 1.06 [CI 0.91–1.23], p=0.33). There was no statistically significant interaction between ACEI/ARB and MRA use post-implant (p=0.14).

Figure 2. Survival by therapy in matched cohorts.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves with number at risk for propensity-matched cohorts of post-implant (A) angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ACEI/ARB) therapy and (B) mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist (MRA) therapy.

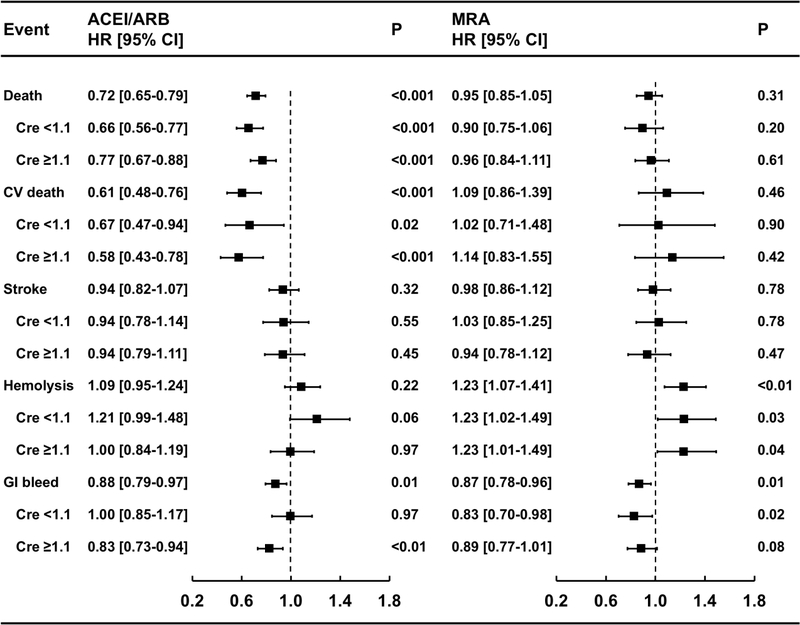

Figure 3. Adverse events by therapy in matched cohorts.

Unadjusted hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for Kaplan-Meier time-to-event analyses are shown for each therapy, both overall and stratified by median creatinine. In the forest plots, HR < 1.0 indicates benefit. ACEI – angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB – angiotensin receptor blocker, MRA – mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

Table 2.

Multivariate predictors of mortality in matched cohorts

| Variable (reference) | ACEI/ARB | MRA | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X2 | HR [95% CI] | P | X2 | HR [95% CI] | P | |

| ACEI/ARB | 26.3 | 0.81 [0.71–0.93] | <0.0001 | 26.7 | 0.77 [0.66–0.90] | <0.0001 |

| MRA | 2.2 | 1.06 [0.91–1.23] | 0.33 | 0.74 | 1.03 [0.88–1.21] | 0.69 |

| Beta-blocker | 11.9 | 0.84 [0.75–0.94] | <0.01 | 8.2 | 0.81 [0.65–0.94] | 0.02 |

| Age (49–66/46–65) | 30.1 | 1.33 [1.12–1.57] | <0.0001 | 27.7 | 1.36 [1.13–1.63] | <0.0001 |

| Female (male) | 0.2 | 1.03 [0.90–1.19] | 0.64 | 1.5 | 1.10 [0.95–1.27] | 0.22 |

| BMI (23.8–32.4/23.8–32.6) | 4.2 | 1.04 [0.90–1.19] | 0.24 | 15.4 | 1.03 [0.88–1.19] | <0.01 |

| BUN (14–25, 14–25) | 45.4 | 1.21 [1.06–1.38] | <0.0001 | 18.9 | 1.25 [1.09–1.43] | <0.001 |

| Creatinine* (0.90–1.36/0.9–1.31) | 8.6 | 1.03 [0.89–1.18] | 0.04 | 7.8 | 1.11 [0.96–1.28] | 0.05 |

| Bilirubin (0.6–1.5/0.6–1.5) | 3.9 | 0.92 [0.83–1.03] | 0.27 | 2.8 | 0.95 [0.85–1.07] | 0.42 |

| Strategy (DT) | 18.2 | 0.001 | 14.0 | <0.01 | ||

| BTT | 0.72 [0.61–0.85] | 0.75 [0.63–0.88] | ||||

| Possible BTT | 0.83 [0.72–0.95] | 0.85 [0.73–0.99] | ||||

| INTERMACS Profile (1) | 5.3 | 0.15 | 4.9 | 0.18 | ||

| Profile 2 | 0.91 [0.76–1.09] | 0.92 [0.76–1.11] | ||||

| Profile 3 | 0.88 [0.73–1.05] | 0.91 [0.75–1.11] | ||||

| Profile 4–7 | 0.79 [0.65–0.97] | 0.79 [0.63–0.99] | ||||

| Prior cardiac surgery | 6.4 | 1.16 [1.04–1.31] | 0.01 | 14.0 | 1.27 [1.12–1.43] | <0.001 |

| Vascular disease | 0.9 | 1.12 [0.89–1.41] | 0.34 | 0.8 | 1.12 [0.88–1.43] | 0.37 |

| Smoking | 7.7 | 1.38 [1.10–1.72] | <0.01 | 6.2 | 1.37 [1.07–1.75] | 0.01 |

Variables are shown with reference category or range for the hazard ratio (HR) and confidence interval (CI). ACEI – angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB – angiotensin receptor blocker, BMI – body mass index, BTT – bridge to transplant, BUN – blood urea nitrogen, DT – destination therapy, MRA – mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, RAAS – renin-angiotensin aldosterone therapy, X2 – model Chi square statistic

– significant nonlinear effect (p<0.05)

Kaplan-Meier survival was significantly better in patients treated with MRA post-implant only among unmatched cohorts (Figure S2b, p<0.001). There was no significant difference in survival among propensity-matched cohorts (Figure 2b, HR 0.95 [CI 0.85–1.05], p=0.31), suggesting other factors favored survival in the unmatched MRA cohort. The estimated survival probability at 12 months (conditional on three-month survival) was 0.92 [CI 0.91–0.93] versus 0.92 [CI 0.91–0.93] for controls and at 24 months was 0.82 [CI 0.80–0.83] versus 0.81 [CI 0.80–0.83] for controls. There was also no survival advantage after stratification by median creatinine (Figure 3). Accordingly, MRA treatment had no significant association with mortality (HR 1.03 [CI 0.88–1.21], p=0.69) after adjustment for established predictors in Cox-regression (Table 2). Notably, ACEI/ARB use was also independently associated with lower mortality in the MRA cohort (HR 0.77 [CI 0.66–0.90], p<0.0001). Other factors independently associated with mortality were age (HR 1.36 [CI 1.13–1.63], p<0.0001), BMI (HR 1.03 [CI 0.88–1.19], p<0.01), beta-blocker use (HR 0.84 [CI 0.75-.95], p=0.02), BUN (HR 1.25 [CI 1.09–1.43], p<0.001), creatinine (HR 1.11 [CI 0.96–1.28], p=0.05), strategy (bridge-to-transplant HR 0.75 [CI 0.63–0.88] and possible bridge-to-transplant HR 0.85 [CI 0.73–0.99], p<0.01), prior cardiac surgery (HR 1.27 [CI 1.12–1.43], p<0.001), and smoking (HR 1.37 [CI 1.07–1.75], p=0.01).

As a sensitivity analysis to ensure there was no selection bias from discarding unmatched subjects, we performed a Cox proportional hazards regression among all patients without matching (Table S4). After age, BUN, and strategy, ACEI/ARB therapy post-implant was one of the strongest factors associated with mortality (HR 0.81 [CI 0.71–0.93], p<0.0001). MRA therapy post-implant (HR 1.06 [CI 0.91–1.23], p=0.33) was not significantly associated with mortality. There was no statistically significant interaction between ACEI/ARB and MRA therapy (p=0.14). Other factors associated with mortality were beta-blocker use (HR 0.84 [CI 0.75–0.94], p<0.01), age, BUN, creatinine, device strategy, prior cardiac surgery, and smoking. These findings were consistent with the propensity-matched analysis.

Adverse Events

The risk of adverse events post-implant in matched cohorts are shown in Figure 3. ACEI/ARB therapy post-implant was associated with significantly lower risk of cardiovascular death (HR 0.61 [CI 0.48–0.76], p<0.001) and lower risk of gastrointestinal bleeding (HR 0.88 [CI 0.79–0.97], p=0.01). There was no significant difference in the risk of hemolysis (HR 1.09 [CI 0.95–1.24], p=0.22), stroke (HR 0.94 [CI 0.82–1.07], p=0.32), or rate of explant for recovery (0.1% vs 0.1%, p=0.99). With stratification by median creatinine, the risk of cardiovascular death was significantly lower in both strata, the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was significantly lower only in the strata with higher creatinine, and there was a non-significant trend toward more hemolysis only in the strata with lower creatinine (Figure 3, Figure S3).

MRA therapy post-implant was associated with significantly lower rate of gastrointestinal bleeding (HR 0.87 [CI 0.78–0.96], p=0.01). There was no significant difference in the rate of cardiovascular death (HR 1.09 [CI 0.86–1.39], p=0.46), stroke (HR 0.98 [CI 0.86–1.12], p=0.78), explant for recovery (0.1% vs 0.1% events/patient-year, p=1.0). There was significantly higher risk of hemolysis (HR 1.23 [CI 1.07–1.41], p<0.01). After stratification by median creatinine, the risk of hemolysis remained significantly higher in both strata, but the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding was only significantly lower in the lower creatinine strata, with a non-significant trend in the higher creatinine strata (Figure 3, Figure S4).

Renal Outcomes

Use of ACEI/ARB post-implant was associated with lower median creatinine at 12-months (1.20 mg/dL [1.00–1.49] vs 1.27 mg/dL [1.00–1.57], p<0.001). There was a non-significant trend toward less dialysis at 12-months (0.4% [16/3567] vs 0.8% [28/3504] events/patient-year, p=0.06). Use of MRA was not associated with significantly different median creatinine at 12-months (1.2 mg/dL [1.00–1.50] vs 1.20 mg/dL [1.00–1.50], p=0.52). There was no significant difference in the rates of dialysis at 12-months (0.5% [18/3322] vs 0.7% [24/3348] events/patient, p=0.37).

Discussion

This is the largest study to date specifically examining outcomes related to RAAS therapy in a multi-center, international cohort of LVAD patients. We analyzed mortality and adverse events among patients with primary, continuous-flow LVADs treated with RAAS inhibitors at three months post-implant and report several notable findings. Patients treated with RAAS therapy tended to be healthier, as evidenced by age, comorbidities, INTERMACS profile, device strategy, and laboratory values. In both propensity-matched and unmatched analyses, ACEI/ARB therapy but not MRA therapy alone, was associated with improved survival despite adjustment for established risk factors for mortality. Accordingly, cardiovascular death was lower in patients treated with an ACEI/ARB but not MRA. GI bleeding was lower among patients receiving either ACEI/ARB or MRA therapies compared to those who did not. Neither therapy was associated with progressive renal dysfunction.

Renin angiotensin aldosterone inhibitors decrease all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality in patients with chronic heart failure, including those NYHA III and IV symptoms, chiefly through reducing progressive heart failure and sudden cardiac death.(9–13) These results showing that ACEI/ARB use was associated with decreased mortality, and specifically decreased cardiovascular death, are consistent with results and effect size observed in landmark trials.(9, 10, 12, 13) The sensitivity analysis in all patients showed a significant association and similar effect size for ACEI/ARB treatment, suggesting the association is less likely secondary to bias from matching. We did not find significant mortality benefit with MRA therapy alone, but it should be noted that the landmark trials for MRAs all included patients already on an ACEI or ACEI plus beta-blocker.(11, 14, 15) Similar to these findings, an earlier INTERMACS analysis reported improved survival associated with both ACEI/ARB therapy or beta-blocker therapy alone, but not MRA alone.(16) In this study, McCollough et al found the greatest benefit occurred in patients on triple neurohormonal combination therapy. Rates of other adverse events associated with goal directed medical therapy (GDMT) are not reported in this earlier study from the North American registry. While the focus of the present investigation was specific to RAAS antagonism in the international cohort, beta-blocker use was similarly associated with improved survival in Cox modelling, independent of RAAS antagonism.

Multiple centers have previously reported outcomes associated with protocolization of intensive neurohormonal blockade targeting recovery or ventricular remodeling among select LVAD recipients. (17–23) Of patients successfully explanted for recovery in EUROMACS, 85% were on a beta-blocker and 71% were on ACEI.(24) In contrast to these reports, we did not observe a significant difference in explant for recovery with isolated ACEI/ARB or MRA therapy when examining the overall cohort, in which rates of explant were very low. However, different populations, different time frames, and the effect of combination therapy do not permit direct comparison.

There are several mechanisms whereby RAAS therapy may impact outcomes during LVAD support. In studies analyzing paired left ventricular myocardial samples during implant and after explant, LVAD support was associated with increased myocardial angiotensin II, norepinephrine, collagen cross-linking, and stiffness.(25–27) These changes were attenuated by ACEI therapy.(25, 26) By inhibiting fibrosis and attenuating catecholamine activity, ACEI/ARB therapy could reduce ventricular arrhythmias. A prior study found that lack of ACEI/ARB therapy predicted occurrence of ventricular arrhythmias.(28) Nevertheless, the mortality benefit associated with ACEI/ARB administration in chronic heart failure is due to a reduction in progressive heart failure, rather than sudden cardiac death. Despite mechanical unloading with an LVAD, progressive heart failure and multiorgan failure remain common causes of death after implant.(2, 3) Rehospitalization rates regrettably are not available in this registry, but would provide greater clarity. Notably, there was no difference in stroke with either RAAS therapy. This was unexpected, since strict blood pressure control decreases the risk of stroke after LVAD implant in at least one device-specific population.(29) Blood pressure was not recorded in the registry, but we included use of other antihypertensives in propensity matching to mitigate any effect. Effect on blood pressure may account for some cardiovascular benefit or conversely the increased risk of hemolysis if treated cohorts had higher pressures.

Finally, RAAS inhibitor use was associated with decreased rate of gastrointestinal bleeding. Single-center, retrospective analyses comparing patients treated with ACEI/ARB versus not found significantly lower rates of all-cause and endoscopically-confirmed arteriovenous malformation-related gastrointestinal bleeding.(30–32) Blocking activation of the angiotensin-II receptor may inhibit angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor and angiopoietin-2. To our knowledge, this is the first study showing an association between MRA use and reduced gastrointestinal bleeding in LVAD patients. Spironolactone inhibits angiogenesis in animal models and human umbilical vein endothelial cells.(33–35) Clinical efficacy for this indication warrants further investigation.

Limitations

Our study was limited by factors inherent to observational data. Despite robust statistical methodology utilizing propensity matching to reduce selection bias for RAAS treatment and adjustment for known predictors of survival, residual bias or confounding cannot be entirely excluded. A causal effect of these observations, therefore, cannot be concluded. Secondly, there was significant cross-over between treatment and control groups by 12 months. A conservative “intention-to-treat” definition of therapy was utilized, whereby crossover would be anticipated to bias toward the null hypothesis rather than a positive treatment effect as identified in the study. Congruous with an effect of early therapy, survival curves separated within a relatively short time-frame. The effect size may thus be underestimated in patients on long-term support, such as destination therapy. Although a time-varying effect model might account for crossover, the volume of missing data at later time points would significantly limit sample size and generalizability.

Conclusion

Among patients alive at three-months, treatment with ACEI/ARB is associated with improved long-term survival following continuous-flow LVAD implantation. MRA therapy is not associated with improved survival based on this observational data, but there was neither evidence of harm. Further research is necessary to better understand biologic mechanisms that may account for this observation. Given the known mortality benefit and safety profile of ACEI/ARB therapy in other heart failure populations, these findings support re-introduction of these medications following LVAD implantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The data for this study was provided by the ISHLT and includes data from the Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support (INTERMACS), National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, Contract number HHSN268200548198C, 2010. Funding for analysis was provided by CTSA award No. UL1 TR002243 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. The reporting and interpretation of these data are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent official views of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

Dr. Brinkley reports a grant from National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from scPharmaceuticals Inc, personal fees from VoluMetrix, and other from Myokardia, outside the submitted work. Drs. Wang, Yu, and Grandin have nothing to disclose. Dr. Kiernan reports personal fees from Medtronic, outside the submitted work; and participation in Medtronic steering committee.

Abbreviations:

- ACEI

angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor

- ARB

angiotensin receptor blocker

- CI

confidence interval

- GDMT

guidelines directed medical therapy

- HF

heart failure

- HR

hazard ratio

- LVAD

left ventricular assist device

- MRA

mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist

- RAAS

renin angiotensin aldosterone system

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al. : 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation 2017;136:e137–e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kormos RL, Cowger J, Pagani FD, et al. : The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs database annual report: Evolving indications, outcomes, and scientific partnerships. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:114–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldstein DJ, Meyns B, Xie R, et al. : Third Annual Report From the ISHLT Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support Registry: A comparison of centrifugal and axial continuous-flow left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:352–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khazanie P, Hammill BG, Patel CB, et al. : Use of Heart Failure Medical Therapies Among Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices: Insights From INTERMACS. J Card Fail 2016;22:672–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grupper A, Zhao YM, Sajgalik P, et al. : Effect of Neurohormonal Blockade Drug Therapy on Outcomes and Left Ventricular Function and Structure After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation. Am J Cardiol 2016;117:1765–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shreibati JB, Sheng S, Fonarow GC, et al. : Heart failure medications prescribed at discharge for patients with left ventricular assist devices. Am Heart J 2016;179:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan Nicholas Y, Sangaralingham Lindsey R, Schilz Stephanie R, Dunlay Shannon M: Longitudinal Heart Failure Medication Use and Adherence Following Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation in Privately Insured Patients. Journal of the American Heart Association 2017;6:e005776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Austin PC: Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharmaceutical Statistics 2011;10:150–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Group TCTS: Effects of Enalapril on Mortality in Severe Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 1987;316:1429–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Investigators TS: Effect of Enalapril on Survival in Patients with Reduced Left Ventricular Ejection Fractions and Congestive Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 1991;325:293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitt B, Zannad F, Remme WJ, et al. : The Effect of Spironolactone on Morbidity and Mortality in Patients with Severe Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 1999;341:709–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohn JN, Tognoni G: A Randomized Trial of the Angiotensin-Receptor Blocker Valsartan in Chronic Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2001;345:1667–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Granger CB, McMurray JJV, Yusuf S, et al. : Effects of candesartan in patients with chronic heart failure and reduced left-ventricular systolic function intolerant to angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors: the CHARM-Alternative trial. The Lancet 2003;362:772–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pitt B, Remme W, Zannad F, et al. : Eplerenone, a Selective Aldosterone Blocker, in Patients with Left Ventricular Dysfunction after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1309–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zannad F, McMurray JJV, Krum H, et al. : Eplerenone in Patients with Systolic Heart Failure and Mild Symptoms. N Engl J Med 2010;364:11–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCullough M, Caraballo C, Ravindra NG, et al. : Neurohormonal Blockade and Clinical Outcomes in Patients With Heart Failure Supported by Left Ventricular Assist Devices. JAMA Cardiology 2020;5:175–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birks EJ, Drakos SG, Lowes BD, et al. : Outcome and Primary Endpoint Results From a Prospective Multi-center Study of Myocardial Recovery Using LVADs: Remission from Stage D Heart Failure (RESTAGE-HF). J Heart Lung Transplant 2018;37:S142–S. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Birks EJ, Tansley PD, Hardy J, et al. : Left Ventricular Assist Device and Drug Therapy for the Reversal of Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2006;355:1873–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birks Emma J, George Robert S, Hedger M, et al. : Reversal of Severe Heart Failure With a Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device and Pharmacological Therapy. Circulation 2011;123:381–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catino AB, Ferrin P, Wever-Pinzon J, et al. : Clinical and histopathological effects of heart failure drug therapy in advanced heart failure patients on chronic mechanical circulatory support. European Journal of Heart Failure 2018;20:164–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dandel M, Weng Y, Siniawski H, et al. : Pre-Explant Stability of Unloading-Promoted Cardiac Improvement Predicts Outcome After Weaning From Ventricular Assist Devices. Circulation 2012;126:S9–S19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drakos SG, Wever-Pinzon O, Selzman CH, et al. : Magnitude and Time Course of Changes Induced by Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Device Unloading in Chronic Heart Failure: Insights Into Cardiac Recovery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;61:1985–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patel SR, Saeed O, Murthy S, et al. : Combining neurohormonal blockade with continuous-flow left ventricular assist device support for myocardial recovery: A single-arm prospective study. J Heart Lung Transplant 2013;32:305–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antonides CFJ, Schoenrath F, de By TMMH, et al. : Outcomes of patients after successful left ventricular assist device explantation: a EUROMACS study. ESC Heart Failure 2020;n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klotz S, Burkhoff D, Garrelds IM, Boomsma F, Danser AHJ: The impact of left ventricular assist device-induced left ventricular unloading on the myocardial renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system: therapeutic consequences? European Heart Journal 2009;30:805–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klotz S, Danser AH, Foronjy RF, et al. : The impact of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor therapy on the extracellular collagen matrix during left ventricular assist device support in patients with end-stage heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:1166–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Klotz S, Foronjy Robert F, Dickstein Marc L, et al. : Mechanical Unloading During Left Ventricular Assist Device Support Increases Left Ventricular Collagen Cross-Linking and Myocardial Stiffness. Circulation 2005;112:364–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Galand V, Flécher E, Auffret V, et al. : Predictors and Clinical Impact of Late Ventricular Arrhythmias in Patients With Continuous-Flow Left Ventricular Assist Devices. JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology 2018;4:1166–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teuteberg JJ, Slaughter MS, Rogers JG, et al. : The HVAD Left Ventricular Assist Device: Risk Factors for Neurological Events and Risk Mitigation Strategies. JACC: Heart Failure 2015;3:818–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Converse MP, Sobhanian M, Taber DJ, Houston BA, Meadows HB, Uber WE: Effect of Angiotensin II Inhibitors on Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients With Left Ventricular Assist Devices. J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;73:1769–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Houston BA, Schneider ALC, Vaishnav J, et al. : Angiotensin II antagonism is associated with reduced risk for gastrointestinal bleeding caused by arteriovenous malformations in patients with left ventricular assist devices. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017;36:380–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schultz J, John R, Alexy T, Thenappan T, Cogswell R: Association between angiotensin II antagonism and gastrointestinal bleeding on left ventricular assist device support. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019;38:469–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klauber N, Browne F, Anand-Apte B, D’Amato Robert J: New Activity of Spironolactone. Circulation 1996;94:2566–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miternique-Grosse A, Griffon C, Siegel L, Neuville A, Weltin D, Stephan D: Antiangiogenic effects of spironolactone and other potassium-sparing diuretics in human umbilical vein endothelial cells and in fibrin gel chambers implanted in rats. Journal of Hypertension 2006;24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wilkinson-Berka Jennifer L, Tan G, Jaworski K, Harbig J, Miller Antonia G: Identification of a Retinal Aldosterone System and the Protective Effects of Mineralocorticoid Receptor Antagonism on Retinal Vascular Pathology. Circulation Research 2009;104:124–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.