Abstract

Background:

Improved screening for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) could enhance MS clinical care; yet the utility of current screening tools for OSA have yet to be evaluated in PwMS.

Objectives:

The STOP-Bang Questionnnaire is an 8-item screening tool for OSA that is commonly used in non-MS samples. The aim of this study was to assess the validity of the STOP-Bang in PwMS.

Methods:

STOP-Bang and polysomnography data were analyzed from n=200 PwMS. Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive value (PPV and NPV) were calculated, with ROC curves, for each STOP-Bang threshold score, against polysomnography-confirmed OSA diagnosis at three apnea severity thresholds (mild, moderate, and severe).

Results:

Nearly 70% had a STOP-Bang score of ≥3 and 78% had OSA. The STOP-Bang at a threshold score of 3 provided sensitivities of 87% and 91% to detect moderate and severe OSA, respectively; and NPV of 84% and 95% to identify PwMS without moderate or severe OSA, respectively. Sensitivity to detect milder forms of OSA was 76%. The NPV to identify persons without milder forms of OSA was 40%.

Conclusions:

The STOP-Bang Questionnaire is an effective tool to screen for moderate and severe OSA in PwMS, but may be insufficient to exclude mild OSA.

Keywords: multiple sclerosis, obstructive sleep apnea, STOP-Bang, brainstem, fatigue, sleepiness

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is characterized by repeated episodes of partial or complete obstruction of the upper airway during sleep, which lead to sleep fragmentation and resultant hypoxia1. This common sleep disorder is linked to many comorbid health problems and economic consequences2, 3. In persons with and without multiple sclerosis (MS), OSA is also associated with symptoms of daytime impairment, including fatigue, cognitive dysfunction, mood disturbances, and reduced quality of life4–8.

The prevalence of OSA may also be increased in persons with MS (PwMS) compared to the general population. Although nationally representative, population-based data are scarce, prior studies of local or regional samples suggest that a substantially higher proportion (37–56%) of PwMS are at elevated risk for OSA, when subjected to screening with commonly used OSA screening tools10–11. These collective data highlight a potential disparity in the diagnosis of OSA among PwMS, and a need for better OSA screening methods12. Yet, to date, well-validated algorithms to identify clinical features that may signal an increased risk of OSA in PwMS are lacking.

Given the overlap between OSA and chronic MS symptoms, as well as the potential comorbidities associated with untreated sleep apnea, screening for OSA in PwMS, in an effective manner, should be prioritized. The STOP-Bang Questionnnaire is a sensitive, reliable OSA screening tool that has been validated in several non-MS outpatient samples against overnight polysomnography, the gold standard diagnostic tool for OSA13. Despite its frequent use in prior MS samples10, 11, the STOP-Bang has not yet been validated in PwMS. This is a key knowledge gap, as the STOP-Bang could potentially perform differently in the setting of other MS-related features that may influence OSA risk9 or fatigue14 – a highly prevalent symptom in MS that may have both OSA and non-OSA contributions, and overlaps with tiredness (a more commonly recognized consequence of OSA that is assessed by the STOP-Bang)5. A better understanding of the utility of the STOP-Bang as a measure of sleep apnea risk assessment in PwMS is therefore needed.

Efficient and cost-effective methods to identify PwMS who are most likely to benefit from OSA evaluation and treatment could enhance MS clinical care. The aim of this study was to assess the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of the STOP-Bang questionnaire in PwMS. We hypothesized that the STOP-Bang would provide adequate sensitivity and predictive values to identify more severe forms of OSA in PwMS, but that predictive values for milder forms of OSA in PwMS would be reduced, relative to non-MS samples.

METHODS

Participants:

Study activities were approved by the University of Michigan (U-M) Institutional Review Board (IRBMED). Data were derived from two sources. First, we extracted baseline data from a sample of participants assessed between November 2015-December 2019 in an ongoing, single-center, randomized controlled trial (RCT) to determine the effects of OSA and its treatment with positive airway pressure on cognitive function in PwMS (“CPAP to Treat Cognitive Dysfunction in MS,” NCT02544373). Second, we extracted retrospective clinical encounter data from patients who underwent multidisciplinary clinical evaluations for fatigue from July 2015-February 2020. These individuals were seen by an MS neurologist and a sleep medicine neurologist at the Michigan Medicine MS Fatigue and Sleep Clinic, which offers comprehensive evaluation and management of sleep disorders that can underlie fatigue in PwMS. Inclusion criteria for the RCT included PwMS age 18-70 with a STOP-Bang score of ≥2 at screening (to maximize inclusivity), or PwMS who carried a diagnosis of OSA (who had not yet started positive airway pressure), regardless of STOP-Bang score. For both groups, all MS subtypes (relapsing-remitting, active secondary progressive/relapsing-progressive, non-active secondary progressive, and primary progressive) were included in this study. Data regarding use of centrally-acting medications at the time of PSG and STOP-Bang administration were also collected.

Measures:

The STOP-Bang Questionnaire:

The STOP-Bang is a validated, 8-item instrument that assesses characteristics known to signal risk for OSA; these characteristics form the acronym “STOP-BANG” (Snoring, Tiredness, Observed apneas, high blood Pressure, BMI, Age, Neck circumference, Gender). Item scores (1/0) are based on yes/no answers13. In a prior non-MS sample, the sensitivity of a STOP-Bang score cutoff at ≥3 was 83.9% to identify mild OSA (apnea hypopnea index (AHI) ≥5 on polysomnography), 92.9% to identify moderate to severe OSA (AHI ≥15), and 100% to predict severe OSA (AHI ≥ 30). In general, a score of 0-2 is considered low risk, 3-4 is considered moderate risk, and 5 or greater (or a score of ≥3 that includes a specific combination of STOP-Bang items) is considered high risk15. The STOP-Bang has been used to assess OSA across variety of study populations, including PwMS10, 11.

For the MS Fatigue and Sleep Clinic patients, STOP-Bang questionnaires were provided in written form upon clinic check-in, for self-administration by patients (with BMI item obtained from weight measured during the visit). For the RCT participants, the trial coordinator assessed each STOP-Bang item verbally, except for neck circumference, which was measured using a tape measure. Previous research by our group among non-MS patients suggested that elicitation of the “Bang” elements of the STOP-Bang in person or by self-report generated comparable results17.

Epworth Sleepiness Scale:

At initial encounters within both groups, subjective sleepiness was assessed with the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)18. The ESS is an 8-item questionnaire that uses 4-point Likert scale items to quantify the likelihood of dozing in sedentary situations. Scores ≥ 10 are consistent with excessive daytime sleepiness18.

Fatigue Severity Scale:

At initial encounters within both groups, fatigue was assessed with the Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS)14. The FSS is a 9-item questionnaire that uses a 7-point Likert scale to assess the impact of fatigue in persons with MS and other chronic diseases. Average FSS scores ≥ 4 suggest fatigue.

Polysomnography (PSG):

Polysomnographic procedures were performed in a sleep laboratory accredited by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM). Scoring followed the latest AASM Scoring Rules19, applied identically to both the clinical and RCT PSG data. Standard measures included: total sleep time (TST, in minutes), sleep efficiency (ratio of time spent asleep to total time in bed), sleep latency (minutes from lights out to first 30-second epoch of any sleep stage), wake after sleep onset (total minutes spent awake after sleep onset, before final awakening time), total arousal index (TAI, average number of electroencephalographic arousals per hour of sleep), % of TST spent in non-rapid-eye-movement stages N1, N2, and N3 sleep, and in stage R sleep, apnea-hypopnea index (AHI; total number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep), respiratory disturbance index (RDI; total number of apneas, hypopneas, and respiratory-related arousals per hour of sleep), minimum oxygen saturation (MinO2; percentage of sleep time with O2 saturation ≤ 88%), the periodic leg movement index (PLMI; number of periodic leg movements per hour of sleep), and the periodic leg movement arousal index (number of periodic leg movements associated with arousals per hour of sleep). Apneas were defined as the cessation of airflow for 10 seconds or longer, with continued respiratory effort (obstructive apneas) or lack of respiratory effort (central apneas). Hypopneas were defined as a reduction in airflow (≥ 30%) lasting ≥10 seconds, accompanied by either a ≥ 3% oxygen desaturation or an arousal. Respiratory effort related arousals were defined by the presence of ≥ 10 seconds of increasing respiratory effort or flattening of the inspiratory portion of the nasal pressure signal, leading to an arousal from sleep. All PSGs were scored by an experienced, registered polysomnographic technologist, and reviewed by a board-certified sleep medicine physician. Any OSA [apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) ≥5], moderate-to-severe OSA (AHI ≥15), or severe OSA (AHI ≥30) was defined according to commonly used criteria20.

Statistical Analyses:

Descriptive statistics were used to examine demographics, health, and sleep data from study participants, stratified by OSA diagnosis. Comparisons of continuous and categorical variables were performed using t-tests, and chi-square tests, respectively. Significance level was set at p < 0.05. Receiving operating characteristics (ROC) curves and summaries of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were computed for each of the observed STOP-Bang scores, against PSG confirmed OSA diagnosis, at three different AHI thresholds (≥5, ≥15, and ≥30). Statistical analysis procedures were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Data from n=200 participants were available for analyses (n=124 trial participants and n=76 clinic patients). The majority of participants were female (Table 1). Mean age was 48.8 ± 10.9 years and the mean BMI was 31.6 ± 7.2 kg/m2. Seventy-eight percent received a PSG diagnosis of OSA (39% mild, 21.5% moderate, 17.5% severe). Most study participants were white (85%) with relapsing forms of MS (Table 1). Median time lapse between STOP-Bang screening and overnight PSG was 0 days for the RCT group and 55.5 days for the clinical group.

Table 1:

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics by OSA diagnosis

| Total Sample (%) | OSA (%) | Non-OSA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Size N (%) | 200 | 156 (78) | 44 (22) |

| Mean age (SD) | 48.8 (10.9) | 50.3 (10.9) | 43.5 (9.6) |

| Sex | |||

| Women N (%) | 138 (69) | 103 (66) | 35 (80) |

| Men N (%) | 62 (31) | 53 (34) | 9 (20) |

| Mean BMI (SD) | 31.6 (7.2) | 32.4 (7.0) | 28.8 (7.5) |

| Race | |||

| White N (%) | 169 (85) | 135 (87) | 34 (77) |

| Black N (%) | 19 (10) | 15 (10) | 4 (9) |

| Other N (%) | 11 (5) | 5 (3) | 6 (14) |

| MS subtype | |||

| RRMS/active SPMS | 161 (81) | 124 (81) | 37 (84) |

| Not active SPMS/PPMS | 37 (19) | 30 (19) | 7 (16) |

| MS Treatment Potency | |||

| Low | 46 (23) | ||

| Moderate /High | 100 (50) | ||

| No treatment | 53 (26) | ||

| Missing DMT data | 1 (1) | ||

| Hypertension | 52 (26) | 46 (29) | 6 (14) |

Acronyms - OSA: obstructive sleep apnea; BMI: body mass index; RRMS: relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; SPMS: secondary progressive multiple sclerosis; PPMS: primary progressive multiple sclerosis.

Treatment Potency - Low: Interferons, Glatiramer acetate and Teriflunomide;

Moderate/High: Dimethyl Fumarate, Fingolimod, Ocrelizumab, Rituximab, Natalizumab and Alemtuzumab

Observed STOP-Bang scores ranged between 0-7, out of a maximum of eight (Figures 1 and 2). Nearly 70% had a STOP-Bang score of ≥3, whereas 26% had a STOP-Bang score of ≥5. Mean STOP-Bang score was 3.5 ± 1.6 points for the entire sample, 3.8 ± 1.6 points in persons with OSA, and 2.4 ± 1.3 points in persons without OSA (Table 2).

Figure 1:

Distribution of STOP-Bang score for the entire sample

Figure 2:

Distribution of STOP-Bang score by obstructive sleep apnea diagnosis

Table 2:

Mean (SD) values for polysomnography-based measures, STOP-Bang score, and fatigue and sleepiness severity by OSA diagnosis

| Variable | Total sample | OSA | Non-OSA |

|---|---|---|---|

| AHI*, hypopneas identified with >= 3% oxygen desaturation or arousal | 17.2 (17.2) | 21.4 (17.3) | 2.5 (1.5) |

| AHI, hypopneas identified with >= 4% oxygen desaturation or arousal | 7.6 (13.0) | 9.6 (14.1) | 0.5 (0.5) |

| Minimum oxygen saturation, % | 87.1 (6.1) | 85.8 (6.2) | 91.6 (2.5) |

| STOP-Bang score | 3.5 (1.6) | 3.8 (1.6) | 2.4 (1.3) |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale score | 9.0 (4.5) | 8.8 (4.2) | 9.6 (5.4) |

| Fatigue Severity Scale score | 5.1 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.4) | 5.1 (1.3) |

AHI: apnea-hypopnea index (number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep)

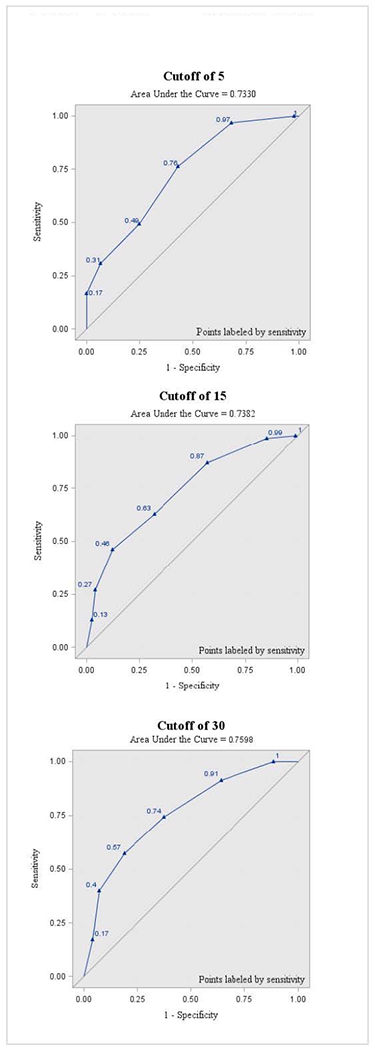

The sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV for each AHI threshold (≥5, ≥15, and ≥30) are described in Tables 3, 4, and 5, respectively. A threshold STOP-Bang score of ≥3 for AHI levels of ≥5, ≥15, and ≥30 was associated with sensitivities of 76%, 87%, and 91%; and specificities of 57%, 43%, and 36%, respectively. Figure 3 illustrates the ROC curves for each AHI threshold (≥5, ≥15, and ≥30). Area under the curve was similar for all thresholds (0.73-0.75). The FSS and ESS scores did not differ significantly between OSA and non-OSA groups (Table 2). Most subjects (n=173) were taking at least one centrally-acting medication. The proportion who used stimulants, sedating medications, or both did not significantly differ between OSA and non-OSA groups.

Table 3.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive-, and negative-predictive values to detect OSA, at an AHI cutoff of ⩾5

| STOP-BANG score | Sensitivity (95%CI) | Specificity (95%CI) | PPV (95%CI) | NPV (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 (97-100) | 0 (0-10) | 78 (71-83) | N/A |

| 1 | 100 (97-100) | 2 (0-14) | 78 (72-84) | 100 (5-100) |

| 2 | 97 (92-99) | 32 (19-48) | 83 (77-88) | 74 (49-90) |

| 3 | 76 (69-83) | 57 41-71) | 86 (79-91) | 40 (28-54) |

| 4 | 49 (41-57) | 75 (59-86) | 88 (79-93) | 29 (21-39) |

| 5 | 31 (24-39) | 93 (80-98) | 94 (83-98) | 28 (21-36) |

| 6 | 17 (11-24) | 100 (90-100) | 100 (84-100) | 25 (19-33) |

| 7 | 8 (5-14) | 100 (90-100) | 100 (72-100) | 24 (18-30) |

All values expressed as percentage unless otherwise indicated. Abbreviations: PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive-, and negative-predictive values to detect OSA, at an AHI cutoff of ⩾15

| STOP-BANG | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 (94-100) | 0 (0-4) | 39 532-46) | N/A |

| 1 | 100 (94-100) | 1 (0-5) | 39 (32-46) | 100 (5-100) |

| 2 | 99 (92-100) | 15 (9-23) | 43 (35-50) | 95 (72-100) |

| 3 | 87 (77-93) | 43 (34-52) | 49 (41-58) | 84 (72-92) |

| 4 | 63 (51-73) | 68 (59-76) | 56 (45-66) | 73 (65-82) |

| 5 | 46 (35-58) | 88 (80-93) | 71 (56-82) | 72 (64-79) |

| 6 | 27 (18-38) | 96 (90-98) | 81 (60-93) | 67 (60-74) |

| 7 | 13 (7-23) | 98 (92-99) | 77 (46-94) | 64 (56-70) |

All values expressed as percentage unless otherwise indicated. Abbreviations: PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value

Table 5.

Sensitivity, specificity, positive-, and negative-predictive values to detect OSA, at an AHI cutoff of ⩾30

| STOP-BANG | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 (88-100) | 0 (0-3) | 18 (13-241) | NA |

| 1 | 100 (88-100) | 1 (0-4) | 18 (13-24) | 100 (5-100) |

| 2 | 100 (88-100) | 12 (7-18) | 19 (14-26) | 100 (79-100) |

| 3 | 91 (76-98) | 36 (29-44) | 23 (17-31) | 95 (86-99) |

| 4 | 74 (56-87) | 62 (55-70) | 29 (21-40) | 92 (85-96) |

| 5 | 57 (40-73) | 81 (74-87) | 39 (26-54) | 90 (84-94) |

| 6 | 40 (24-56) | 93 (87-96) | 54 (34-73) | 88 (82-92) |

| 7 | 17 (7-34) | 96 (91-98) | 46 (20-74) | 84 (78-89) |

All values expressed as percentage unless otherwise indicated. Abbreviations: PPV: positive predictive value; NPV: negative predictive value

Figure 3:

ROC curve of the STOP-Bang for apnea-hypopnea index cutoffs of 5, 15, and 30

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the validity of the STOP-Bang Questionnaire as a screening tool for OSA in PwMS. Our results show that the STOP-Bang, set at a threshold score of 3 or more positive features out of 8, provides reasonably high sensitivity to detect moderate and severe forms of OSA in PwMS, and good negative predictive value to correctly identify PwMS who do not have OSA. The sensitivity of this instrument to detect patients with milder forms of OSA was less robust, and the negative predictive value of the STOP-Bang to correctly classify persons without mild OSA was poor. This new evidence suggests that the STOP-Bang is likely to be a useful screening tool to identify PwMS who may have moderate-severe OSA, but may be insufficient to exclude those with mild OSA.

The STOP-Bang provides a simple, cost-effective means to facilitiate timely identification and treatment of OSA. To this end, our findings offer potential to enhance clinical MS care by determining which PwMS have the highest need for clinical OSA evaluations. Obstructive sleep apnea, and severe forms of OSA in particular, are independently associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality, incident stroke, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, and other comorbidities2, 21–23 that are linked to increased disability in PwMS24. In addition to these long-term health consequences, prior studies suggest that OSA also contributes to fatigue and sleepiness in persons with and without MS11, 25, 26, making early identification and treatment of OSA an essential yet overlooked aspect of MS management. Persons with MS who have concomitant OSA, and those at elevated OSA risk, may experience increased fatigue severity compared with undiagnosed or low-risk patients8, 10, 11, 27.

Obstructive sleep apnea severity also is associated with cognitive dysfunction, which affects up to 70% of PwMS28. Impairment of memory, executive function, processing speed, and calculation29–31 have been linked to sleep fragmentation and hypoxemia in OSA4. Nocturnal hypoxia that arises from OSA is also postulated to cause neuroimaging and neuropathological abnormalities in the hippocampus, subcortical white matter, and regions of the cerebral cortex that may be disproportionately affected in MS32. Previous work by the authors has demonstrated significant associations between respiratory measures of OSA and working memory, processing speed, attention, verbal learning, and response inhibition. These collective findings highlight a potential opportunity to ameliorate a treatable cause of fatigue and cognitive impairment in MS through improved sleep4, 11.

The cost of sleep apnea evaluations further highlight the need for more efficient sleep apnea screening methods in PwMS. In-lab polysomnography is costly and may impose excessive patient burden in those with neurological impairment, highlighting the need for judicious referral and selection of testing methods. Home sleep apnea tests (HSAT) or Type 3 tests are modified portable sleep apnea tests can be used patients with a high-pretest probability of moderate to severe OSA in the absence of signifcant pulmonary or cardiovascular disease. Identifying PwMS with high likelihood of moderate to severe OSA could assist in the stratification of patients for whom HSAT may be appropriate, resulting in cost savings and decreased patient burden. However, future research on HSAT use in PwMS is needed.

One notable finding was the limited negative predictive value of the STOP-Bang to correctly exclude patients with any form of sleep apnea, when including milder forms sleep apnea (AHI≥5). Given that the prevalence of a condition under study has a direct effect on predictive values, this finding (as well as the high observed positive predictive value), could be explained by the high overall prevalence of OSA in the present sample (78%). The high proportion of females in our sample may also in part explain these findings, which are similar to a recent study that suggested the STOP-Bang may not be as sensitive for OSA screening of women33.

A possibility also exists that MS-specific features not captured by the STOP-Bang could partially explain the lower negative predictive value of the STOP-Bang to detect milder forms of apnea. Although MS patients are susceptible to the same OSA risk factors as the general population, additional risk factors associated with MS may increase the likelihood or severity of sleep-disordered breathing in this population. These include impairment of brainstem motor and sensory networks that control airway patency and respiratory drive9, progressive MS subtypes and increased disability9, and use of several medications including anti-spasmodics benzodiazepines and opiate analgesics. Disease modifying therapy use has been associated with lower apnea severity, and treatment with disease modifying therapies may improve apnea severity in non-MS patients9, 34. Given these MS-specific sleep apnea risk factors along with current findings that indicate limited effectiveness of the STOP-Bang to identify potential mild OSA among PwMS, clinicians should not be dissuaded to seek further OSA evaluations for those with low STOP-Bang scores, if clinical suspicion for OSA is high. An MS-specific screening tool that includes MS-specific as well as general OSA risk factors could prove useful.

The observed positive predictive values also deserve mention. The capacity of the STOP-Bang to identify true OSA cases among those with positive scores (≥3) was relatively low for moderate and severe OSA subtypes. One potential explanation for this finding may be the high prevalence of fatigue in MS, which overlaps substantially with tiredness, a symptom that is captured in the STOP-Bang. Although many patients with OSA report problems with fatigue, tiredness, or lack of energy to supersede problems with sleepiness35, MS fatigue has other potential determinants, beyond OSA. Fatigued individuals without OSA who endorse “yes” on the tiredness STOP-Bang item may therefore be more likely to score 3 or more on the questionnaire, and consequently appear to have higher risk for OSA. To this end, observed FSS and ESS scores deserve comment. Although increased fatigue and sleepiness have been associated with OSA in prior MS11 and non-MS samples35, neither symptom significantly differed between OSA and non-OSA patients in our study. This observation may relate to effects from stimulants or sedating medications, which were used by a similar proportion of OSA and non-OSA patients. In this respect, inclusion of patients on centrally-acting medications is a limitation. The study was also not designed to assess for concomitant sleep disorders, including central hypersomias, following OSA diagnosis.

This study assessed validity of the STOP-Bang instrument in a unique sample of PwMS. The observed range of STOP-Bang scores (0-7) allowed us to test the performance of this instrument across heterogeneous and representative OSA risk levels. Further, inclusion of all MS subtypes and a high proportion of clinical patients provided an opportunity to mimic real-world administration of the STOP-Bang in a clinical setting. Use of in-laboratory polysomnography, the gold standard diagnostic tool for OSA, with uniformly-applied scoring methods across both patient groups alleviated potential measurement biases.

Some limitations should be acknowleged. Despite a relatively heterogeneous sample of clinical and research patients, the majority of both groups received their primary MS care at the University of Michigan, a tertiary MS center which could limit generalizability of these findings. Some patients in the clinical group had a relatively long lapse of time between STOP-Bang and PSG, which could potentially affect results if patients had experienced any changes in STOP-Bang-related characteristics within that timeframe (BMI, new hypertension). Finally, we acknowledge that selection bias, due to recruitment of patients and RCT participants who were more likely to have sleep problems, could have influenced results. However, individuals seen in the MS-sleep clinic, many of whom do not have OSA, are referred for a heterogeneous mix of complaints; in some cases, fatigue in the absence of a sleep disorder. Furthermore, data from RCT participants who did not have OSA (screen failures) were still included in analyses.

Obstructive sleep apnea is a consequential and prevalent condition that is underdiagnosed in MS. Enhanced detection of OSA in PwMS through better screening could provide a new opportunity to enhance patient health and wellbeing. Our findings support the use of the STOP-Bang as an effective tool to screen for moderate and severe OSA in PwMS, and suggest that providers should consider incorporating this tool into clinical practice. As the reduced ability of the STOP-Bang to exclude mild OSA may reflect in part the high prevalence of OSA in this sample, decisions regarding the need for OSA evaluations in patients with low STOP-Bang scores should be governed by clinical judgment.

Funding:

This work was supported by a research grant from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (RG 5280-A-2, PI Braley). Dr. Dunietz’s work was supported in part by a K01 award (K01 HL144914 NIH/NIHLBI). Dr. Gavidia’s work was supported in part by an NINDS Neurology T32 award (T32 NS007222 NIH/NINDS). Dr. Chervin has received research grant funding from the NIH. He serves as an editor and author for UpToDate. He has produced a copyrighted questionnaire, patents, and patents pending, owned by the University of Michigan, focused on assessment or treatment of sleep disorders. He has received questionnaire licensing fees from Zansors. He has served on the Boards of Directors for the International Pediatric Sleep Association and the non-profit Sweet Dreamzzz, and on an advisory board for the non-profit Pajama Program.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, et al. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010;90(1):47–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gottlieb DJ, Yenokyan G, Newman AB, et al. Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: the sleep heart health study. Circulation. 2010;122(4):352–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Redline S, Yenokyan G, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and incident stroke: the sleep heart health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182(2):269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braley TJ, Kratz AL, Kaplish N, et al. Sleep and Cognitive Function in Multiple Sclerosis. Sleep 2016;39(8):1525–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braley TJ, Chervin RD, Segal BM. Fatigue, Tiredness, Lack of Energy, and Sleepiness in Multiple Sclerosis Patients Referred for Clinical Polysomnography. Multiple Sclerosis International. 2012;2012:673936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daurat A, Sarhane M, Tiberge M. [Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome and cognition: A review]. Neurophysiol Clin. 2016;46(3):201–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kerner NA, Roose SP. Obstructive Sleep Apnea is Linked to Depression and Cognitive Impairment: Evidence and Potential Mechanisms. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2016;24(6):496–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaminska M, Kimoff R, Benedetti A, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea is associated with fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Multiple Sclerosis Journal.2012;18(8):1159–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Braley TJ, Segal BM, Chervin RD. Sleep-disordered breathing in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2012; 79(9):929–936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brass SD, Li CS and Auerbach S. The underdiagnosis of sleep disorders in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Sleep Med 2014; 10(9): 1025–1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Braley TJ, Segal BM and Chervin RD. Obstructive sleep apnea and fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine 2014; 10(02): 155–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braley TJ, Segal BM, Chervin RD. Obstructive sleep apnea is an under-recognized and consequential morbidity in multiple sclerosis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):709–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung F, Subramanyam R, Liao P, et al. High STOP-Bang score indicates a high probability of obstructive sleep apnoea. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108(5):768–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Krupp LB, LaRocca NG, Muir-Nash J, et al. The fatigue severity scale. Application to patients with multiple sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Arch Neurol. 1989;46(10):1121–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung F, Yang Y, Brown R, et al. Alternative scoring models of STOP-bang questionnaire improve specificity to detect undiagnosed obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(9):951–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boynton G, Vahabzadeh A, Hammoud S, et al. Validation of the STOP-BANG Questionnaire among Patients Referred for Suspected Obstructive Sleep Apnea. J Sleep Disord Treat Care. 2013;2(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, et al. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events: Rules, Terminology and Technical Specifications. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sleep-Related Breathing Disorders in Adults: Recommendations for Syndrome Definition and Measurement Techniques in Clinical Research. Sleep. 1999;22(5):667–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall NS, Wong KK, Cullen SR, et al. Sleep apnea and 20-year follow-up for all-cause mortality, stroke, and cancer incidence and mortality in the Busselton Health Study cohort. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(4):355–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nieto FJ, Young TB, Lind BK, et al. Association of sleep-disordered breathing, sleep apnea, and hypertension in a large community-based study. Sleep Heart Health Study. JAMA. 2000;283(14):1829–1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xie J, Sert Kuniyoshi FH, Covassin N, et al. Nocturnal Hypoxemia Due to Obstructive Sleep Apnea Is an Independent Predictor of Poor Prognosis After Myocardial Infarction. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang T, Tremlett H, Zhu F, et al. Effects of physical comorbidities on disability progression in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2018;90(5):e419–e427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mulgrew AT, Ryan CF, Fleetham JA, et al. The impact of obstructive sleep apnea and daytime sleepiness on work limitation. Sleep Med. 2007;9(1):42–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popp RF, Fierlbeck AK, Knuttel H, et al. Daytime sleepiness versus fatigue in patients with multiple sclerosis: A systematic review on the Epworth sleepiness scale as an assessment tool. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;32:95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veauthier C, Radbruch H, Gaede G, et al. Fatigue in multiple sclerosis is closely related to sleep disorders: a polysomnographic cross-sectional study. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2011;17(5):613–622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Grzegorski T, Losy J. Cognitive impairment in multiple sclerosis - a review of current knowledge and recent research. Rev Neurosci. 2017;28(8):845–860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DeLuca J, Barbieri-Berger S, Johnson SK. The nature of memory impairments in multiple sclerosis: acquisition versus retrieval. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1994;16(2):183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kujala P, Portin R, Ruutiainen J. Memory deficits and early cognitive deterioration in MS. Acta Neurol Scand. 1996;93(5):329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology. 1991;41(5):685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zimmerman ME, Aloia MS. A review of neuroimaging in obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2006;2(4):461–471. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Orbea CAP, Lloyd RM, Faubion SS, et al. Predictive ability and reliability of the STOP-BANG questionnaire in screening for obstructive sleep apnea in midlife women. Maturitas. 2020;135:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braley TJ, Huber AK, Segal BM, et al. A randomized, subject and rater-blinded, placebo-controlled trial of dimethyl fumarate for obstructive sleep apnea. SLEEP 2018; 41(8). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chervin RD. Sleepiness, Fatigue, Tiredness, and Lack of Energy in Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Chest. 2000;118(2):372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]