Abstract

Asparagine endopeptidase (AEP), a newly identified delta-secretase, simultaneously cleaves both APP and Tau, promoting Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathologies. However, its pathological role in AD remains incompletely understood. Here we show that delta-secretase cleaves BACE1, a rate-limiting protease in amyloid-β (Aβ) generation, escalating its enzymatic activity and enhancing senile plaques deposit in AD. Delta-secretase binds BACE1 and cuts it at N294 residue in an age-dependent manner and elevates its protease activity. The cleaved N-terminal motif is active even under neutral pH and associates with senile plaques in human AD brains. Subcellular fractionation reveals that delta-secretase and BACE1 reside in the endo-lysosomes. Interestingly, truncated BACE1 enzymatic domain (1–294) augments delta-secretase enzymatic activity and accelerates Aβ production, facilitating AD pathologies and cognitive impairments in APP/PS1 AD mouse model. Uncleavable BACE1 (N294A) inhibits delta-secretase activity and Aβ production and decreases AD pathologies in 5XFAD mice, ameliorating cognitive dysfunctions. Hence, delta- and beta- secretases’ crosstalk aggravates each other’s roles in AD pathogenesis.

Keywords: delta-secretase, beta-secretase, Aβ, senile plaques, Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the leading cause of dementia worldwide, is characterized by the pathological hallmarks including the extracellular senile plaques, mainly consisted of accumulated β-amyloid peptide (Aβ) within the brain, along with intraneuronal neurofibrillary tangles (NFT), predominantly composed of hyperphosphorylated and cleaved forms of microtubule-associated protein Tau(Selkoe, 2001). Aβ peptide is generated following the sequential cleavage of APP (amyloid precursor protein) by β- and γ-secretases in the amyloidogenic pathway(Vassar, 2004). β-secretase, which is an aspartyl protease, is known to be β-site APP cleaving enzyme I (BACE1)(Hussain et al., 1999; Lin et al., 2000; Sinha et al., 1999; Vassar et al., 1999; Yan et al., 1999). BACE1 is initially synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) as a precursor protein (pro-BACE1) with a molecular weight around ~60 kDa(Capell et al., 2000; Haniu et al., 2000; Huse et al., 2000), which in turn undergoes swift modification into a 70 kDa mature form in the Golgi via glycosylation and the removal of the propeptide motif. While BACE1 has a relatively long half-life, the enzyme is known to be degraded by at least three mechanisms: 1) endoproteolytic within its catalytic domain(Huseet al., 2003); 2) The ubiquitin-proteasomal pathway(Qing et al., 2004); 3) the lysosomal pathway(Cole and Vassar, 2007; Koh et al., 2005). Most recently, we reported that BACE1 K501 residue is SUMOylated, which increases its protease activity and stability, leading to the cognitive defect in AD mouse model(Bao et al., 2018). Noticeably, BACE1 levels and enzymatic activity are increased in AD(Fukumoto et al., 2002; Fukumoto et al., 2004; Zhao et al., 2007).

Delta-secretase is a newly characterized asparagine endopeptidase (AEP, gene name Legumain, LGMN)(Zhang et al., 2015). Delta-secretase is an endo-lysosomal cysteine proteinase with a preference for an asparagine residue at the P1 site and its enzymatic activity is mainly mediated by post-translational modification under different pH values(Chen et al., 1997). Delta-secretase undergoes auto-proteolytic maturation at acidic pH for catalytic activation. It is activated by sequential removal of the N-terminal pro-peptide and followed by cleavage via caspases at D25. On the C-terminus, its autocatalytic truncation occurs at N323, followed by removal of the activation peptide at K289, resulting in a mature active core domain with the peak activity around pH 4.5–5(Dall and Brandstetter, 2013; Zhao et al., 2014). Previously, we reported that AEP is activated under acidosis triggered by MCAO (middle cerebral artery occlusion) that cleaves SET, a DNase inhibitor, leading to neuronal cell death under stroke(Liu et al., 2008). Remarkably, it is upregulated and activated during aging in the brain, and simultaneously cleaves both APP and Tau and mediates amyloid pathology and NFT. Notably, delta-secretase cleaves APP at N373 and N585 residues, augmenting Aβ production and facilitating senile plaque formation(Zhang et al., 2015). It also shreds Tau at N255 and N368, enhancing Tau aggregation and neurotoxicity. Deletion of delta-secretase from Tau P301S mice ameliorates the Tauopathies(Zhang et al., 2014). Most recently, we also show that SRPK2, a cell-cycle kinase activated in AD, phosphorylates delta-secretase on S226 residue and triggers its activation and cytoplasmic translocation, accelerating AD pathologies(Wang et al., 2017). Notably, we found that its age-dependent escalation is predominantly mediated C/EBPβ, an inflammatory cytokine-mediated transcription factor, which is also upregulated in AD(Strohmeyer et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018).

In the current study, we report that BACE1 is a substrate of delta-secretase, which mainly cleaves BACE1 at N294 and escalates its protease activity, promoting Aβ production. Delta- and beta- secretases reside together in the endo-lysosomes, and the truncated N-terminal BACE1 fragment (a.a. 1–294) and delta-secretase co-localize with senile plaques in human AD brains. Markedly, BACE1 N294 feeds back and elevates delta-secretase activity. Viral delivery of BACE1 (a.a. 1–294) into APP/PS1 mice stimulates delta-secretase activities and Aβ deposition, leading to AD pathologies and cognitive deficits. By contrast, uncleavable of BACE1 (N294A) mutant decreases delta-secretase activities and Aβ production in 5XFAD mice, mitigating AD pathologies and cognitive deficits.

Materials and Methods:

Cell culture, mice and human samples

HEK293 cells were cultured in high-glucose DMEM added with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin (100 units/ml) - streptomycin (100 μg/ml) (all from Hyclone). Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Primary rat cortical neurons were cultured as previously described(Zhang et al., 2015). All rats were bought from the Jackson Laboratory. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. 5XFAD mice and APP/PS1 mice on a C57BL/6J background were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Stock No. 006554 and 004462, respectively). 3XTg mice on a C7BL/6; 129X1/SvJ; 129S1/Sv background was obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Stock No. 034830). AEP knockout mice on a mixed C57BL/6 and 129/Ola background were generated as reported (Shirahama-Noda et al., 2003). Only male mice were used, the animals were assigned to different experimental groups based on the litter in a way that every experimental group had a similar number of males. Animal care and handling were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and Emory Medical School guidelines. The following animal groups were analyzed: WT, AEP−/−, 5XFAD, 5XFAD/AEP−/−, APP/PS1, 3XTg, 3XTg/AEP−/−. Sample size was determined by Power and Precision (Biostat). The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Emory Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (201700197). Post-mortem brain samples were dissected from frozen brains of 6 AD cases and 6 non-demented controls from the Emory Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (Table S1). The study was approved by Emory Biospecimen Committee. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. AD was diagnosed according to the criteria of the Consortium to Establish a Registry for AD and the National Institute on Aging. Diagnoses were confirmed by the presence of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in formalin-fixed tissue. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects.

Antibodies and Reagents

Primary antibodies to the following targets were used: APP N585, APP C586 and Tau N368 which specifically recognize the δ-secretase-derived APP and tau fragments respectively, were described previously(Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). AEP 6E3 and 11b7 (from Dr Colin Watts, University of Dundee), GST-HRP (Sigma-Aldrich, # GE RPN1236), LAMP1 (Santa Cruz, #5570), GFP (Santa Cruz, #101525), TrkB (Santa Cruz, #377218), myc (Santa Cruz, #M4439), sAPPβ (6A1, IBL, #10321), AT100 (Thermo, #MN1060), BACE1 N terminal (abcam, #ab79921), APP N terminal (22C11, Calbiochem, #MAB348), Aβ 4G8 (Signet, #800709), β-actin (Cell Signaling, #3700), BACE1 C terminal (Cell Signaling, #5606), EEA1 (Cell Signaling, #3288), GGA3 (Cell Signaling, #8027), Histone H3 (Cell Signaling, #4499), TOMM 20 (Cell Signaling, #42406), ERp57 (Cell Signaling, #2881), see details in Table S2. Mouse and human Aβ1–40 and Aβ1–42 ELISA kits were purchased from Invitrogen, recombinant AEP was purchased from Novoprotein.

Generation of antibodies specifically recognizing AEP-generated BACE1 fragment (anti–BACE1 N294).

Two rabbits received booster injections 4 times with the immunizing peptide Ac-CSIVDSGTTN-OH every 3 weeks intervals, which includes the 10 amino acids in BACE1 that precede the AEP cleavage site at N294 as well as an amino-terminal cysteine residue. The collected antiserum was purified via affinity chromatography with the immunizing peptide and then was adsorbed to a peptide spanning the Full-length BACE1. The immune-activity of the antiserum was further confirmed by western blot and immunohistochemistry.

Transfection and infection of the cells

The overexpressing plasmids were purchased from Addgene. HEK293 transfection was performed by the calcium phosphate precipitation method. To express GFP, BACE1 FL-GFP, BACE1 N294A-GFP, BACE1 1–294-GFP, BACE1 295–501-GFP in primary neurons, 1.0 μl lentiviruses (1 × 1013 vg ml min−1) was added into 1 ml culture medium respectively. The overexpression lentivirus (pFCGW-GFP) was from the viral vector core (VVC) of Emory University.

Hippocampal stereotactic injection

Animals were anesthetized with intraperitoneal injections of 100/10 mg/kg ketamine/xylazine and given 0.1 mg/kg buprenorphine subcutaneously for pain management. Depth of anesthesia was assessed via toe-pinch. The mice had their heads shaved and restrained in a stereotaxic frame with mouse adapter (Stoeltling, Wood Dale, IL). Sterile Bausch & Lomb erythromycin ophthalmic ointment (0.5%) was applied to the eyes to keep them from drying out, and their heads cleaned with 70% ethanol. A small incision was made in the skin down the midline of the cranium, exposing the skull landmarks lambda and Bregma. Hydrogen peroxide was used to clean the top of the skull. Target injection coordinates were mapped from Bregma, and a small hole drilled through the skull directly above target sites with a bone drill. Each HC of each animal received two 1 -μL injections of lentiviruses (1 × 1013 vg ml min−1): Control, BACE1 Fl-GFP, BACE1 N294A-GFP, BACE1 1–294 respectively, into areas CA1. CA1 coordinates were anteroposterior (AP) −2.2 mm, mediolateral (ML) ± 1.7 mm, dorsoventral (DV) 1.6mm. Injection rate was 0.2 μL per minute, for a total of 5 min per injection, and the needle left in place for 1-min post-injection. After injections, the incision was sutured and Neosporin applied. Animals recovered on heating pads until awake and monitored 1, 2, 7, and 10 days post-surgery. All surgeries were performed with IACUC approval. Mice were assigned into gender- and age-matched treatment groups using a randomized block design.

GST-pull Down

The cell lysates were incubated with 50 μl of a 50% slurry of Glutathione Sepharose 4B overnight at 4 °C with end-over-end mixing. The medium was sendimented by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min. The supernatant was decanted carefully. The Glutathione Sepharose 4B breads were washed by adding 1 ml lysate buffer to each tube and inverted to mix and sedimented by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min. After repeating three times, the sediment was analyzed by Western blot.

Mass spectrometry analysis

To assess the cleavage of BACE1 by AEP in vitro, two 10-cm dishes of HEK293 (~1X107 cells each dish, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)) were transfected with 10 μg GST-BACE1 plasmids by the calcium phosphate precipitation method. 48 hours after transfection, the cells were collected, washed 3 times in PBS, lysed in RIPA buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% NP-40, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerophosphate, and 1 mM Na3VO4) with protease inhibitor cocktail on ice for 20 min. The starting material used for this experiment is 1000ug. The protein concentration was diluted into 5 ug/ul. Samples were precleared by pre-incubation with protein A/G beads for 20 min in 4°C, then centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000g at 4 °C. The supernatants were incubated with Glutathione Sepharose 4B (10 ul) overnight at 4 °C. After washed with PH=6.0 RIPA buffer for 3 times, change the buffer into PH=6.0 RIPA buffer, then incubated with 1ug activated AEP (37 kD) at 37 °C for 60 min, shacked every 10 min. The samples were then boiled in 50 ul 1XSDS loading buffer for 10min and analyzed by Coomassie staining and immunoblotting. Protein samples were in-gel digested with trypsin and analyzed by LC/MS/MS.

In vitro BACE1 cleavage assay

To assess the cleavage of BACE1 by AEP in vitro, HEK293 cells (obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC)) were transfected with 10 mg BACE1-GFP or GST-BACE1 plasmids by the calcium phosphate precipitation method. 48 hours after transfection, the cells were collected, washed once in PBS, lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM sodium citrate, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1% CHAPS and 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 7.4), and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000g at 4 °C. The supernatant was then incubated with recombinant AEP proteins at pH 7.4 or 6.0 at 37 °C for 30 min. To measure the cleavage of purified BACE1 fragments by AEP, GST-tagged BACE1 full length or fragments were purified with glutathione beads. The purified BACE1 was incubated with recombinant AEP (5 mg ml−1) in AEP buffer (50 mM sodium citrate, 5 mM DTT, 0.1% CHAPS and 0.5% Triton X-100, pH 6.0) for 30 min. The samples were then boiled in 1X SDS loading buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Immunoprecipitation and Western Blotting

The tissues or cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 5 mM EDTA, 5 mM EGTA, 15 mM MgCl2, 60 mM glycerophosphate, 0.1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 0.1 mM NaF, 0.1 mM benzamide, 10 mg/ml aprotinin, 10 mg/ml leupeptin and 1 mM PMSF) for 20 min on ice. Cell debris was removed by centrifuging at 14,000 rpm for 20 min at 4 °C. The protein extract was diluted to 1–5 mg/ml. The sample was incubated overnight at 4 °C with the recommended amount of antibody, followed by detection by immunoblotting.

AEP activity assay

Tissue homogenates or cell lysates (20 μg) were incubated in 200 μL reaction buffer (20 mM citric acid, 60 mM Na2HPO4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% CHAPS and 1 mM DTT, pH 5.5) containing 20 μM AEP substrate Z-Ala-Ala-Asn-AMC (Bachem). AMC released by sub-strate cleavage was quantified by measuring at 460 nm in a fluorescence plate reader at 37 °C in kinetic mode.

BACE1 activity assay

Analysis was performed as previously described(Ermolieff et al., 2000). Briefly, tissue homogenates or cell lysates (10 μg) were incubated in 200 μL reaction buffer (0.1 M Sodium acetate, pH 4.5) containing 10 mM BACE1 substrate H-Arg-Glu (Edans)-Glu-Val-Asn-Leu-Asp-Ala-Glu-Phe-Lys (Dabcyl)-Arg-OH (Peptides international). An excitation wavelength of 350 nm and an emission wavelength of 490 nm were used to monitor the hydrolysis of substrate in a fluorescence plate reader at 37 °C in the kinetic mode.

ELISA quantification of Aβ

To detect the concentrations of Aβ in tissues or cell lysates, the samples were diluted with cold reaction buffer (PBS with 5% BSA and 0.03% Tween-20, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail), and centrifuged at 16,000g for 20 min at 4 °C. Then analyzed with human Aβ42 (KHB3441, Invitrogen), human Aβ40 (KHB3481, Invitrogen), mouse Aβ42 (KMB3441, Invitrogen), mouse Aβ40 (KMB3481, Invitrogen) ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Aβ concentrations were determined by comparison with the standard curve.

Subcellular fractionation

Subcellular fractionation of the mouse brain tissue was performed as described previously (Zhang et al., 2015). Briefly, 200 mg frontal cortex tissue was minced with a scalpel blade in 1ml of homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail). The buffer was discarded after centrifugation at 100 g for 2 min. The tissues were suspended in 1.5 ml homogenization buffer and homogenized by successive passages through needles of increasing gauge number (19–26). The suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min to discard nuclei and cellular debris. The supernatant was adjusted to 1.4 M sucrose, and incorporated into a discontinuous sucrose gradient consisting of the four following layers: 2 ml 2 M sucrose, 2.25 ml 1.4 M sucrose, 3.75 ml 1.2 M sucrose and 5 ml 0.8 M sucrose. The gradients were centrifuged for 2.5 h at 100,000 g. 13 fractions were collected from the top of the gradient and stored as aliquots at −80 °C. Equal volume of each fraction was boiled in 1X SDS loading buffer and analyzed by immunoblotting.

Cell organelle separation

400 mg mouse cortex tissue was minced with a scalpel blade in 1ml of homogenization buffer (0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail). The buffer was discarded after centrifugation at 100 g for 2 min. The tissues were suspended in 1.5 ml homogenization buffer and homogenized by successive passages through needles of increasing gauge number (19–26). The suspension was centrifuged at 1,000 g for 10 min to collect P1 (pellet) and S1 (suspension), S1 was centrifuged at 3,000 g for 10 min to obtain P2 and S2, S2 was centrifuged at 6,000 g for 10 min to fraction into P3 and S3, S3 was centrifuged at 10,000 g for 10 min to separate P4 and S4, S4 was centrifuged at 20,000 g for 10 min to collect P5 and S5, S5 was centrifuged at 100,000 g for 10 min to yield P6. P1 was adjusted to 60% sucrose and centrifuged at 100,000 g for 60 min to obtain the nuclear part, the suspension was centrifuged at 160,000 g for 180 min to enrich the plasma membrane part. P2+P3+P4 was put in a discontinuous OptiPrep™ (Sigma) gradient consisting of the 3 following layers: 20%, 30%, 45%, and centrifuged at 50,000g for 120 min to obtain the mitochondria part, P4+P5 was put in a discontinuous OptiPrep™ (Sigma) gradient consisting of the 4 following layers: 10%, 20%, 40%, 55%, and centrifuged at 50,000 g for 120 min to achieve the lysosomes part, P4+P5 was loaded in a discontinuous sucrose gradient consisting of the 4 following layers: 10%, 20%, 32%, 44%, and centrifuged at 160,000 g for 60 min to obtain the Golgi apparatus part, P6 was loaded in a discontinuous sucrose gradient consisting of the 2 following layers: 20%, 45% with 15mM CsCl, and centrifuged at 150,000 g for 60 min to obtain the endoplasmic reticulum part, P6 was loaded in a continuous OptiPrep™ (Sigma) gradient consisting of the following layers from 5% to 40% and centrifuged at 85,000g for 45 min to collect the endosome part.

Immunofluorescence

Transfected/treated cells or mice brain slices or human tissues were fixed and incubated for 2448 h at 4 °C with primary antibodies followed by 1 h at 37 °C with Alexa Fluor® 568- or Alexa Fluor® 488- or Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). DAPI (1 μg/ml) (Sigma) was used for the nuclei staining. Images were acquired through Confocal (Olympus FV1000).

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed by using the peroxidase protocol. Briefly, tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene, hydrated through descending ethanol, and endogenous peroxidase activity was eliminated by incubation in 3% hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 5 min. After antigen-retrieval in boiling sodium citrate buffer (10 mM), the sections were incubated with primary antibodies for overnight at 4 °C. The signal was developed using Histostain-SP kit (Invitrogen).

Aβ plaque histology

Amyloid plaques were stained with Thioflavin-S. Free-floating 40 μm brain sections were incubated in 0.25% potassium permanganate solution for 20 min, rinsed in distilled water, and incubated in bleaching solution containing 2% oxalic acid and 1% potassium meta-bisulfite for 2 min. After rinsed in distilled water, the sections were transferred to blocking solution containing 1% sodium hydroxide and 0.9% hydrogen peroxide for 20 min. The sections were incubated for 5 s in 0.25% acidic acid, then washed in distilled water and stained for 5 min with 0.0125% Thioflavin-S in 50% ethanol. The sections were washed with 50% ethanol and placed in distilled water. Then the sections were covered with a glass cover using mounting solution and examined under a fluorescence microscope. The plaque number and plaque area were calculated using the ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). For immunohistochemical visualization of Aβ, the brain sections were treated with 0.3% H2O2 for 10 min. Then, sections were washed three times in PBS and blocked in 1% BSA, 0.3% Triton X-100, for 30 min followed by overnight incubation with anti-Aβ antibody (1: 500, Sigma-Aldrich) at 4°C. The signal was developed using Histostain-SP kit.

Golgi staining

Mouse brains were fixed in 10% formalin for 24 h, and then immersed in 3% potassium bichromate for 3 days in the dark. The solution was changed each day. Then the brains were transferred into 2% silver nitrate solution and incubated for 24 h in the dark. Vibratome sections were cut at 60 μm, air dried for 10 minutes, dehydrated through 95% and 100% ethanol, cleared in xylene and cover-slipped.

Electron Microscopy

After deep anesthesia, mice were perfused transcardially with 2% glutaraldehyde and 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Hippocampal slices were post-fixed in cold 1% OsO4 for 1 hr. Samples were prepared and examined using standard procedures. Ultrathin sections (90 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead acetate and viewed at 100 kV in a JEOL 200CX electron microscope. Synapses were identified by the presence of synaptic vesicles and postsynaptic densities.

Electrophysiology

Acute hippocampal transversal slices were prepared from different ages of 5XFAD, APP/PS1 mice injected with lentiviruses as previously described (Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). Briefly, mice were anaesthetized with isoflurane, decapitated, and their brains dropped in ice-cold artificial cerebrospinal fluid (a-CSF) containing 124 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 6.0 mM MgCl2, 26 mM NaHCO3, 2.0 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM glucose. Hippocampi were dissected and cut into 400-μm thick transverse slices with a vibratome. After incubation at room temperature (23–24 °C) in a-CSF for 60–90 min, slices were placed in a recording chamber (RC-22C, Warner Instruments) on the stage of an up-right microscope (Olympus CX-31) and perfused at a rate of 3 ml per min with a-CSF (containing 1 mM MgCl2) at 23–24 °C. A 0.1 MΩ tungsten monopolar electrode was used to stimulate the Schaffer collaterals. The field excitatory post-synaptic potentials (fEPSPs) were recorded in CA1 stratum radiatum by a glass microelectrode filled with a-CSF with resistance of 3–4 MΩ. The stimulation output (Master-8; AMPI, Jerusalem) was controlled by the trigger function of an EPC9 amplifier (HEKA Elektronik, Lambrecht, Germany). fEPSPs were recorded under current-clamp mode. Data were filtered at 3 kHz and digitized at sampling rates of 20 kHz using Pulse software (HEKA Elektronik). The stimulus intensity (0.1 ms duration, 10–30 μA) was set to evoke 40% of the maximum f-EPSP and the test pulse was applied at a rate of 0.033 Hz. LTP of fEPSPs was induced by 3 theta-burst-stimulation (TBS), it is 4 pulses at 100 Hz, repeated 3 times with a 200-ms interval). The magnitudes of LTP are expressed as the mean percentage of baseline fEPSP initial slope.

Morris Water maze

Different ages of 5XFAD, APP/PS1 mice injected with indicated lentiviruses were trained in a round, water-filled tub (52-inch diameter) in an environment rich with extra maze cues. An invisible escape platform was located in a fixed spatial location 1 cm below the water surface independent of a subject start position on a particular trial. In this manner, subjects needed to utilize extra maze cues to determine the platform’s location. At the beginning of each trial, the mouse was placed in the water maze with their paws touching the wall from 1 of 4 different starting positions (N, S, E and W). Each subject was given 4 trials/day for 5 consecutive days with a 15-min inter-trial interval. The maximum trial length was 60 s and if subjects did not reach the platform in the allotted time, they were manually guided to it. Upon reaching the invisible escape platform, subjects were left on it for an additional 5 s to allow for survey of the spatial cues in the environment to guide future navigation to the platform. After each trial, subjects were dried and kept in a dry plastic holding cage filled with paper towels to allow the subjects to dry off. The temperature of the water was monitored every hour so that mice were tested in water that was between 22 and 25 °C. Following the 5 days of task acquisition, a probe trial was presented during which time the platform was removed and the percentage of time spent in the quadrant which previously contained the escape platform during task acquisition was measured over 60 s. All trials were analysed for latency and swim speed by means of MazeScan (Clever Sys, Inc.).

Contextual fear conditioning

The ability to form and retain an association between an aversive experience and environmental cues was tested with a standard fear conditioning paradigm that occurs over a period of 3 d. Mice were placed in the fear conditioning apparatus (7” W, 7” D 3 12” H, Coulbourn) composed of Plexiglass with a metal shock grid floor and allowed to explore the enclosure for 3 min. Following this habituation period, 3 conditioned stimulus (CS)-unconditioned stimulus (US) pairings were presented with a 1 min intertrial interval. The CS was composed of a 20 s, 85-dB tone and US was composed of 2 s of a 0.5-mA footshock, which was co-terminate with each CS presentation. One minute following the last CS-US presentation, mice were returned to their home cage. On day 2, the mice were presented with a context test, during which subjects were placed in the same chamber used during conditioning on day 1 and the amount of freezing was recorded via a camera and the software provided by Coulbourn. No shocks were given during the context test. On day 3, a tone test was presented, during which time subjects were exposed to the CS in a novel compartment. Initially, animals were allowed to explore the novel context for 2 min. Then the 85-db tone was presented for 6 min and the amount of freezing behavior was recorded.

Statistical analysis

For in vitro assays, the analysis was conducted by a blind individual, who did not know the sample information. The animal’s information for in vivo assays was decoded after all samples were analyzed. All data are expressed as mean ± SEM from three or more independent experiments and analyzed using GraphPad Prism statistical software (GraphPad Software). All of the statistical details of experiments can be found in the figure legends for each experiment, including the statistical tests used, number of mice in animal experiments (represented as n, unless otherwise stated), number of wells in cell culture experiments (represented as n, unless otherwise stated), definition of center (mean). Sample size was determined by Power and Precision (Biostat). The level of significance between two groups was assessed with unpaired t test with Welch’s correction. For more than two groups, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test was applied. The two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test compared the differences between groups that have been split on two independent factors. A value of p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

BACE1 is a substrate of delta-secretase

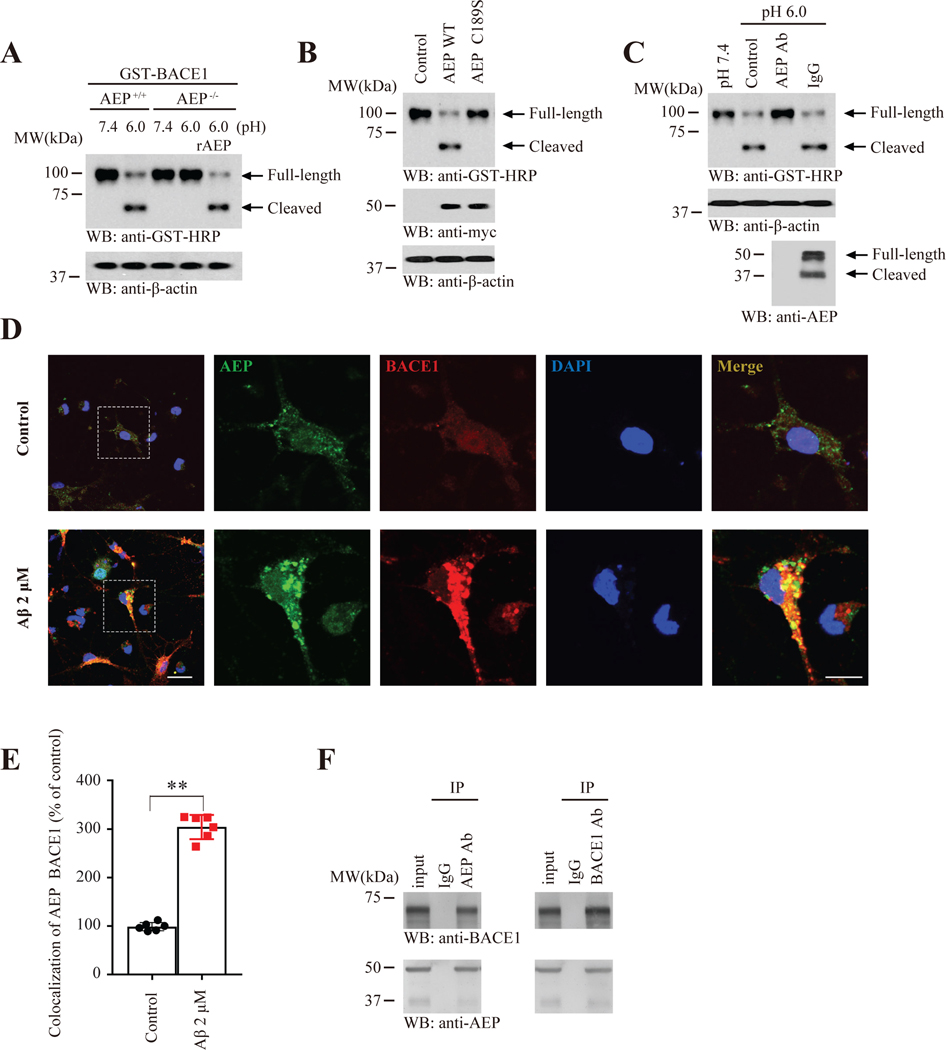

BACE1 acts as rate-limiting enzyme for Aβ production, an important event for AD pathology. Moreover, delta-secretase acts as an upstream trigger that cleaves both APP and Tau in AD. Since both secretases cleave APP, hence, they might crosstalk with each other.To assess whether indeed BACE1 can be cleaved by delta-secretase, we conducted an in vitro cleavage assay. GST-BACE1 was selectively truncated under pH 6.0 but not 7.4 in WT but not delta-secretase KO lysates. Re-introduction of recombinant delta-secretase proteins into pH 6.0 KO samples reconstituted BACE1 cleavage, indicating that delta-secretase might be responsible for BACE1 proteolytic cleavage (Figure 1A). Further, we found that WT but not enzymatic-dead delta-secretase (C189S) shredded BACE1, supporting that delta-secretase enzymatic activity is required for BACE1 fragmentation (Figure 1B). In addition, BACE1 cleavage was completely blunted in the presence of delta-secretase antibody but not control IgG, suggesting that delta-secretase specifically mediates BACE1 fragmentation (Figure 1C). To investigate whether these two secretases may associate with each other in cells, we treated primary neurons with Aβ42 (2 μM) for 24 h, which reduced the neuronal density and changed the morphology (Supplementary Figure 1). Immunofluorescent (IF) co-staining showed that Aβ42 treatment potently augmented both secretase protein levels and they co-localized within the neurons (Figure 1D&E). Co-IP revealed that both proteins tightly interacted with each other in human AD brains (Figure 1F). Thus, delta-secretase binds and cleaves BACE1.

Figure 1: BACE1 is a substrate of delta-secretase.

(A) GST-BACE1 cleavage assay with AEP+/+ and AEP−/− mice brain lysates. Western blot analysis of BACE1 cleavage by AEP. BACE1 was cleaved at pH 6.0 by AEP+/+ brain lysates or recombinant AEP. (B) BACE1 cleavage assay with enzymatic-dead delta-secretase. GST-BACE1 was cotransfected with wild-type or C189S mutant myc-AEP in SH-SY5Y cells, western blot analysis of cleavage of BACE1. (C) Antibody titration assay. Brain lysates (100 ug) were incubated with AEP-specific antibody (20 ug) for 10 min, and then incubated with GST-BACE1 for 30 min. The processing of BACE1 was determined using western blot. (D) Delta-secretase and BACE1 co-localize in primary neurons. Primary neuronal cultures (DIV 12) were treated with 2 μM of pre-aggregated Aβ for 24 h, followed by immunostaining with various antibodies including anti-AEP, anti-BACE1. Scale bar, Low magnification 20 μm, High magnification 10 μm. (E) Quantification of AEP binding with BACE1 in D, Data represent mean ± SEM., n=6. (**P < 0.01, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction). (F) Co-IP of BACE1 and AEP in human AD brain. BACE1 in human AD brain lysates was immunoprecipitated with anti-BACE1 antibody and analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-BACE1 and anti-AEP antibody. Delta-secretase interacted with BACE1.

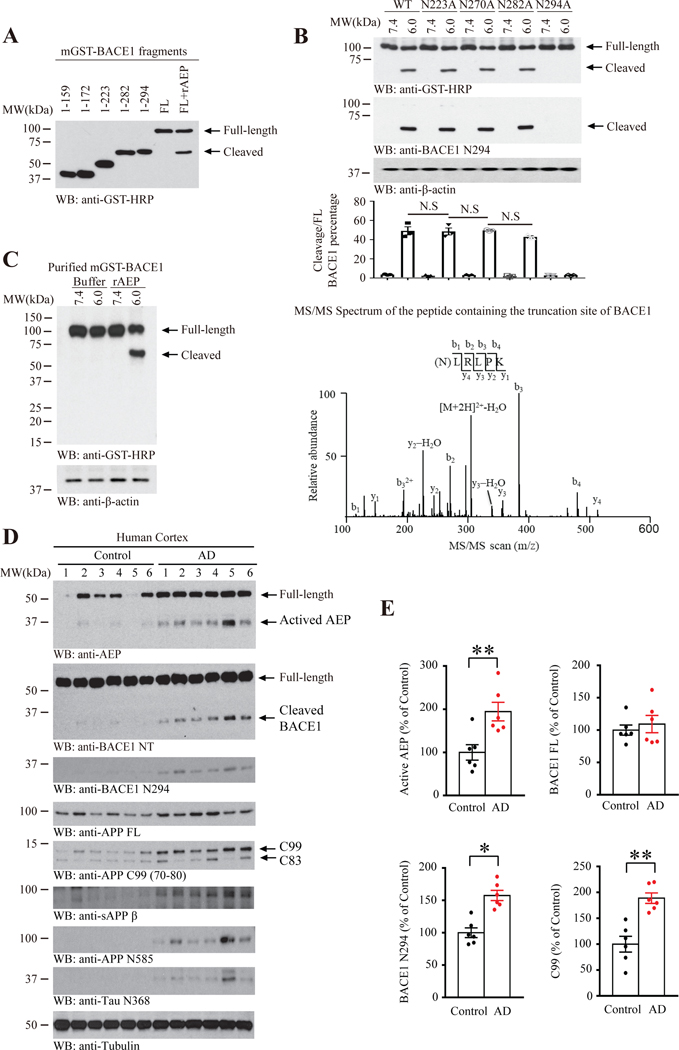

Delta-secretase cleaves BACE1 at N294 residue

To map the potential cleavage site on BACE1 by delta-secretase, we prepared numerous BACE1 fragments and in vitro cleavage assay showed that BACE1 might be cut around 282–294 region by delta-secretase (Figure 2A). Next, we developed and purified rabbit polyclonal BACE1 N294 specific antibody that selectively recognized the truncated but not BACE1 FL (Full-length). To test the specificity of this antibody, we conducted an in vitro assay with purified delta-secretase and recombinant mGST-BACE1 proteins expressed in mammalian cells, and found that BACE1 N294 but not FL BACE1 was selectively recognized by this antibody (Supplementary Figure 2A). Next, BACE1 WT and BACE1−/− mice brains were lysed under pH 7.4 or 6.0, and endogenous BACE1 was selectively cleaved under pH 6.0. The truncated fragments were specifically recognized by rabbit polyclonal anti-BACE1 N294 antibody, whereas BACE1 FL was not recognized by this antibody, underscoring the specificity of the antibody (Supplementary Figure 2B). We extended our studies into human AD brain lysates, which were Co-IP with BACE1 N294 antibody, was recognized by anti-BACE1 NT and anti-BACE1 N294 antibodies at the same location, supporting that anti-BACE1 N294 antibody is specific in recognizing fragmented BACE1 cutting at N294 site (Supplementary Figure 2C). The antibodies’ specificity was further validated by pre-incubation with various peptides. Antigen peptide (BACE1 286–294) completely abolished the IHC staining signals of anti-BACE1 N294, whereas the scramble nonspecific peptide failed (Supplementary Figure 2D). Notably, employing the specific antibodies, we found that BACE1 N294 co-localized with BACE1 NT in AD cortex (Supplementary Figure 2E). Site-directed mutagenesis assay revealed that N294A mutation completely abrogated BACE1 cleavage by delta-secretase, suggesting that N294 might be the key cutting site (Figure 2B). To ascertain BACE1 cleavage site, we purified cleaved BACE1 fragment and performed proteomic analysis and found that N294 is the major cutting site on BACE1 by delta-secretase (Figure 2C). It is worth noting that the aspartate catalytic domain is located in the N-terminus of BACE1 before N294. Cleavage at N294 site may release the enzyme domain of BACE1 from tethering it within the membrane. Immunoblotting analysis showed that delta-secretase was selectively activated in human AD brains, correlating with prominent BACE1 N294 cleavage, coupling with the positive control APP N585 and Tau N368 (Figure 2D). BACE1 fragmentation was also validated by its specific NT antibody (Figure 2D, 2nd panel). The quantitative analysis showed that active AEP, BACE1 N294 and C99 (70–80) levels were higher in AD group compared with age-matched healthy control (Figure 2E). Co-IP showed that both FL and its N-terminal fragment of BACE1 1–294 but not C-terminal 295–501 truncate selectively interacted with delta-secretase (Supplementary Figure 2F). In addition, knockout of delta-secretase from 5XFAD mice completely abrogated BACE1 N294 cleavage (Supplementary Figure 2G), further supporting that delta-secretase is indispensable for BACE1 cleavage in AD brains.

Figure 2: Delta-secretase cleaves BACE1 at N294 residue.

(A) Mapping the cleavage site of BACE1 by delta-secretase. Western blot of the purified recombinant BACE1 fragments. (B) BACE1 N294A mutation blocks its cleavage by delta-secretase. Western blot showing processing of various mutated BACE1 cleavage by AEP (upper). Quantization of cleavage/full length BACE1 percentage (lower), Data represent mean ± SEM. of 3 samples in each group (N.S no significant, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction). (C) Western blot showing purified GST-BACE1 cleaved by recombinant AEP at pH 6.0 (left), proteomic analysis of BACE1 recombinant proteins processed by AEP (right). The detected peptide sequences indicate that N294 is the main cleavage site with the shed bands of molecular weight (MW) ~40kDa. (D) Delta-secretase cleaves BACE1 in the AD brains. WB detection of BACE1 processing in human brain samples from AD patients and age-matched controls. (E) Quantification of active AEP, BACE1 FL, BACE1 N294, C99 (70–80) protein level in D, Data represent mean ± SEM. of 6 cases in each group (*P<0.05, **P < 0.01, unpaired t test with Welch’s correction).

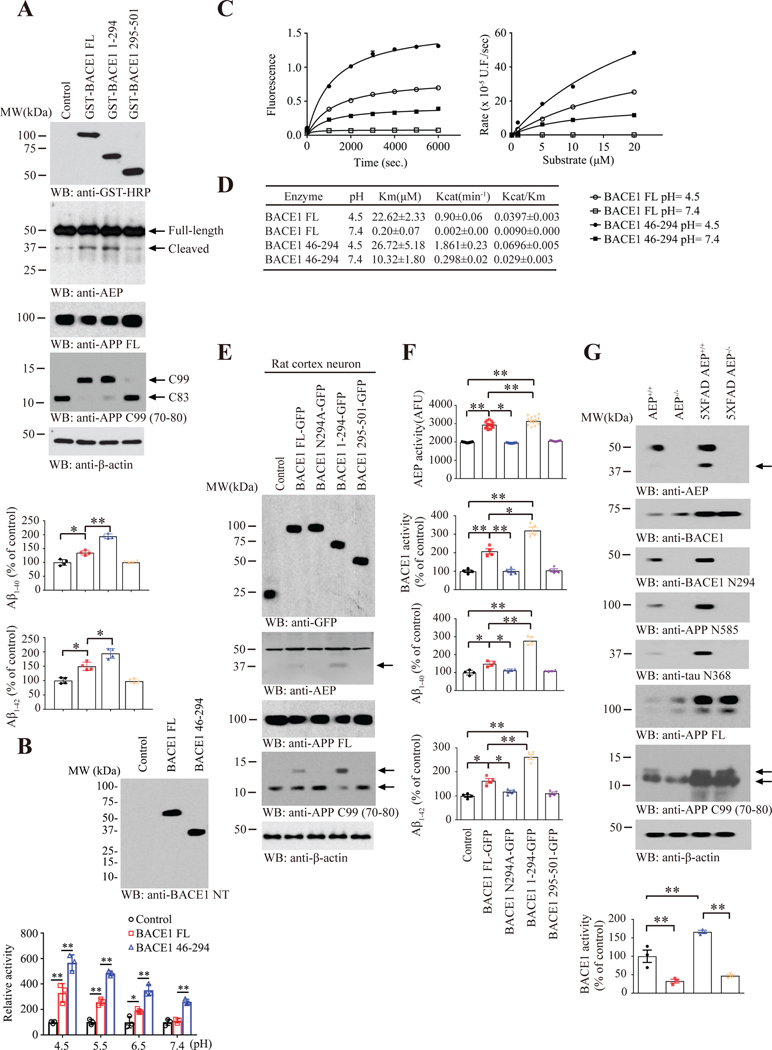

Delta-secretase cleavage elevates BACE1 enzymatic activity

To examine the biological effect of BACE1 cleavage by delta-secretase, we generated BACE1 N-terminal 1–294 and C-terminal 295–501 truncates. Remarkably, Aβ ELISA showed that BACE1 N294 significantly escalated Aβ40 and Aβ42 production as compared to FL BACE1, whereas C-terminal 295–501 displayed no activity as compared to control (Figure 3A). Immunoblotting showed that delta-secretase was strongly activated under BACE1 N294, followed by BACE1 FL. It was barely activated in the presence of control or C-terminal 295–501 fragment (Figure 3A, 2nd panel), fitting with BACE1 enzymatic activity pattern. Since BACE1 enzymatic activity is mediated by pH, we examined whether pH values affect BACE1 N294 enzymatic activity or not. In vitro assay found that FL BACE1 displayed its peak activity at pH 4.5 and declined as the pH increased. By contrast, its catalytic domain a.a. 46–294 without the signal peptide exhibited more robust enzymatic activity than FL under all of pH values. Strikingly, it was even active under neutral pH (pH 7.4), whereas FL revealed no activity at all (Figure 3B). To establish the precise nature of the hydrolysis of this substrate by different BACE1 and pH values, we measured initial rates of BACE1 hydrolysis with different time points and substrate concentrations (Figure 3C) and determined the kinetic parameters Km and Kcat (Figure 3D). For recombinant BACE1, the kinetic parameters at pH 4.5 were Km= 22.62± 2.33 μM, Kcat= 0.90± 0.06 min−1, BACE1 46–294 displayed higher Km and Kcat than BACE1 at pH 4.5. Once again, it was active under neutral pH (pH 7.4), whereas FL revealed no activity at all. To explore the potential effect of BACE1 N294 cleavage on delta-secretase maturation, we infected virus expressing BACE1 FL, 1–294, 295–501 and uncleavable N294A mutant into primary neurons. Again, we found that BACE1 N294 strongly triggered delta-secretase activation and maturation. In contrast, BACE1 295–501 and N294A mutant failed to trigger delta-secretase activation. Consequently, Aβ40 and Aβ42 secreted in the neuronal medium was the highest in BACE1 N294 expressed cells, followed by FL. The C-terminal 295–501 and FL displayed no enzymatic effects as compared with control (Figure 3E–F). In alignment with its proteolytic cleavage, delta-secretase enzymatic activity was climaxed in BACE1 N294 transfected cells (Figure 3F, upper panels). To further investigate delta-secretase cleavage on BACE1 enzymatic activity, we monitored BACE1 enzymatic activity in WT and 5XFAD mice and found both delta-secretase and BACE1 were upregulated in 5XFAD mice as compared to WT mice, and N294 was more abundant in 5XFAD than WT mice. These effects were consistent with prominent APP N585 and Tau N368 truncates in 5XFAD. However, when delta-secretase was depleted, BACE1 N294 was completed eradicated. Accordingly, 5XFAD mice displayed higher BACE1 enzymatic activity than WT mice, which was substantially reduced in delta-secretase knockout mice (Figure 3G). Therefore, delta-secretase cleaves BACE1 and augments its enzymatic activity.

Figure 3: Delta-secretase cleavage elevates BACE1 enzymatic activity.

(A) Cleaved BACE1 (a.a. 1–294) possesses higher enzymatic activity. HEK293-APP cells transfected with control plasmid, GST-BACE1 FL, GST-BACE1 1–294 and GST-BACE1 295–501 for 48 h, then harvested for WB, Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42 Elisa. Data represent mean ± SEM. of 4 samples in each group (*P < 0.05, **P<0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (B) Truncated BACE1 (a.a.46–294) displays enzymatic activity under neutral pH. WB showing PBS control, Recombinant BACE1 FL, Recombinant BACE1 46–294 (upper), continued with BACE1 activity assay of gradient pH (lower). Data represent mean ± SEM. of 3 samples in each group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (C) Increase in fluorescence during the hydrolysis of 5 μM substrate (left) and kinetic plot for the hydrolysis of fluorogenic substrate FS-1 in the presence of 0.5 μM BACE1 FL or BACE1 46–294 at different pH conditions (right). U.F. is arbitrary fluorescent unit. (D) Kinetic Parameters of BACE1 FL or BACE1 46–294 at different pH conditions. (E-F) Cleaved BACE1 (a.a. 1–294) triggers delta-secretase activation. Rat cortex neuron (DIV 10) infected with control, BACE1 FL-GFP, BACE1 N294A-GFP, BACE1 1–294-GFP and BACE1 295–501-GFP lentivirus for 4d, then harvested for WB, BACE1 activity assay, AEP activity assay and Aβ1–40, Aβ1–42 Elisa. Arrows indicated the cleaved AEP, C99, and C83 respectfully. Data represent mean ±SEM. of 4 samples in each group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (G) Delta-secretase is required for BACE1 activation in 5XFAD mice. 10 months old AEP+/+, AEP−/−, 5XFAD AEP+/+ and 5XFAD AEP−/− brain samples were employed for detection of BACE1 N294 by WB and BACE1 activity assay. Arrows indicated the cleaved AEP, C99, and C83 respectfully. Data represent mean ± SEM. of 3 mice in each group (**P < 0.01, two-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post hoc test).

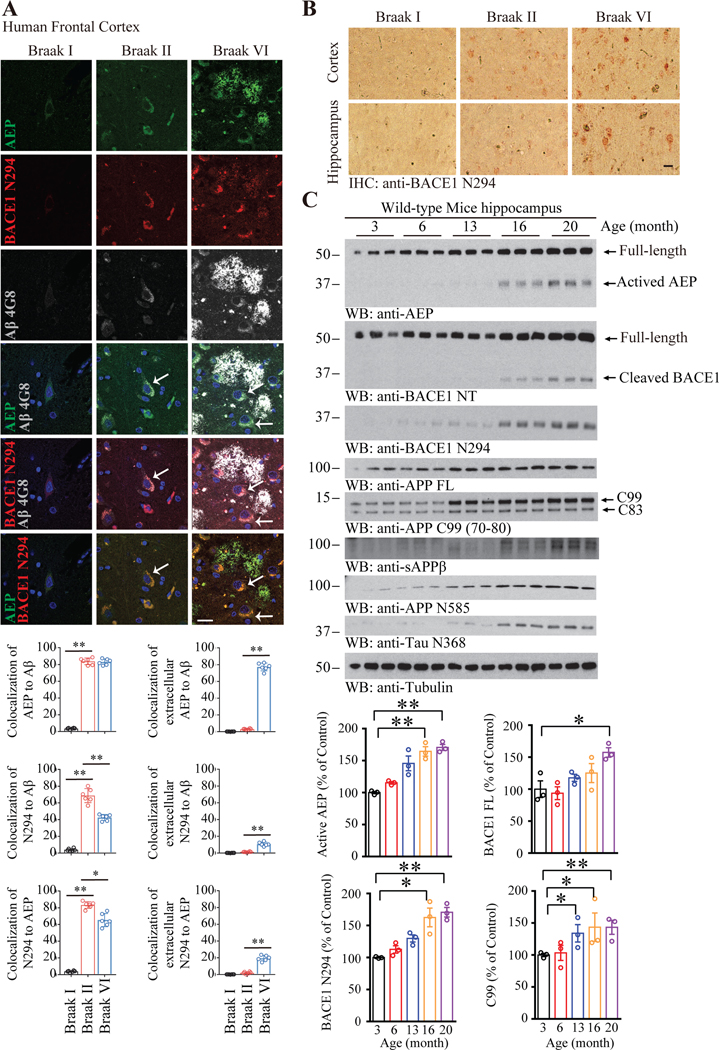

Delta-secretase and BACE1 progressively escalate in AD brains

To test whether both secretases crosstalk with each other during AD progression, we conducted IF staining on healthy control, Braak II and Braak VI AD brain sections. Interestingly, we found that both delta-secretase and BACE1 N294 progressively augmented from control to Braak II to VI stage, tightly correlating with elevated Aβ deposition in the Braak VI AD brains. Noticeably, not only delta-secretase co-localized with BACE1 N294 but also the extracellular Aβ plaques co-stained with BACE1 N294. Moreover, delta-secretase was also secreted extracellularly, co-localizing with Aβ and BACE1 N294 (Figure 4A), indicating that both secretases may associate with each other within the neurons and bind to the extracellular senile plaques as well. Confocal IF study revealed that both delta-secretase and BACE1 signal intensities were elevated in AD brain as compared to control brain, so were delta-secretase/BACE1 N294 and BACE1/BACE1 N294 co-localization activities (Supplementary Figure 3A–C). Z-stack analysis of each section scanning confirmed that delta-secretase co-localized with BACE1 N294, and BACE1 co-localized with BACE1 N294 signals (Supplementary Figure 4). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) showed that BACE1 N294 gradually elevated from control to Braak II to VI (Figure 4B). To validate the staining’s specificity, APP N terminal antibody was employed as a negative control for Aβ plaques. Clearly, AEP and BACE1 N294 co-localized in the extracellular space (Supplementary Figure 3D, showed with arrowheads). In addition, the extracellular AEP in Braak VI frontal cortex co-localized with Aβ plaques, which was confirmed by Aβ (4G8) and Thioflavin S co-staining (Supplementary Figure 3G). To assess whether delta-secretase cuts BACE1 during aging, we examined the processes in both mouse brains and human brains with different ages. As expected, delta-secretase was gradually escalated with the ages, so were the truncated mature form (Figure 4C & Supplementary Figure 3H, top panels). To ascertain that delta-secretase indeed plays a crucial role in mediating BACE1 N294 cleavage and Aβ generation, we conducted IF co-staining using anti-BACE1 N294 or anti-BACE1 NT with anti-Aβ and anti-delta-secretase on WT, delta-secretase-KO, and 3×Tg and 3×Tg/delta-secretase KO brain sections. Delta-secretase was largely upregulated and co-localized with truncated BACE1 N294 or BACE1 in 3×Tg mice as compared with WT mice, and it was completed eradicated in delta-secretase-null mice. Consequently, BACE1 N294 cleavage was greatly escalated, so was Aβ in 3×Tg mice, and these effects were substantially diminished in delta-secretase-KO mice (Supplementary Figure 5). Consistent with active delta-secretase augmentation, BACE1 was also pronouncedly escalated with aging in both human and mouse brains, fitting with continuing elevation of truncated BACE1 N294 and APP N585 fragments from delta-secretase, the quantitative analysis showed that active AEP, BACE1 FL, BACE1 N294 and C99 (70–80) levels were higher in aging compared with young group (Figure 4C). Hence, both secretases are age-dependently upregulated and delta-secretase cleaves BACE1 N294 in human AD brains, promoting Aβ generation.

Figure 4: Delta-secretase and BACE1 progressively escalate in AD brains.

(A) Cleaved BACE1 (a.a. 1–294) colocalized with delta-secretase. Upper, Confocal analysis showing AEP (green), BACE1 N294 (red), Aβ (gray) localization in frontal cortex of Aging control (Braak I, Braak II) and Braak VI AD patients. Scale bar, 20 μm. Arrows showed the merged intracellular part. Lower, quantifications of the immunofluorescence, data represent mean ± SEM. of 3 independent cases in each group, 2 sections per case (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (B) Immunohistochemistry showing BACE1 N294 staining in cortex and hippocampus of Aging control, Braak II and Braak VI AD patients. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) BACE1 N294 is age-dependently cleaved by delta-secretase. WB showing AEP and BACE1 N294 expressing and processing in mouse brain during aging, Data represent mean ± SEM. of 3 mice in each group (*P<0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test).

Delta-secretase and BACE1 co-localize in the endo-lysosomes

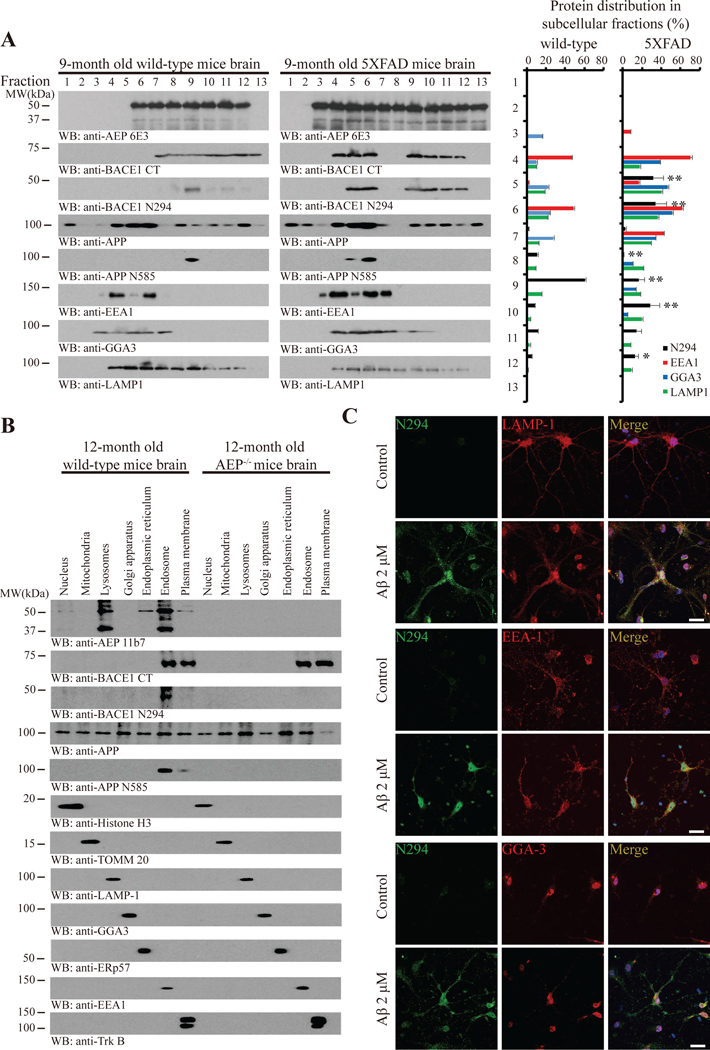

To define the cellular compartments where delta-secretases cleaves BACE1, we conducted the subcellular fractionation, and found that most of both secretases co-fractionated within LAMP1 positive the endo-lysosomes, and discovered truncated BACE1 N294 and APP N585 mainly distributed in fraction #9 in 9-month old WT brain (Figure 5A, left panels). In 5XFAD mice, both secretases were highly upregulated, and delta-secretase was distributed from fraction #3 to 13, and BACE1 was allocated from fraction #4–6 and from #9–12. Notably, truncated BACE1 N294 and APP N585 were greatly augmented and allotted from fraction #5–6, where both the EEA-1 positive early endosome and the GGA-3 positive TGN were resided, and from #9–12, where predominantly the endo-lysosomes were dispensed (Figure 5A, middle panels). The relative subcellular protein distribution ratios were summarized in right panel of Figure 5A. To further determine exact which subcellular organelle possesses both secretases and BACE1 N294, we isolated various cellular organelles by subcellular fractionation. In WT mouse brain, delta-secretase FL and its mature form were primarily distributed in both the early endosomes and endo-lysosomes, whereas BACE1 FL principally resided in both the early endosomes and plasma membrane. Noticeably, BACE1 N294 and APP N585 selectively localized within the early endosomes. Depleting delta-secretase completely diminished BACE1 N294, but did not change BACE1 FL residency. The separated organelles were validated by their specific biomarkers (Figure 5B). To further interrogate BACE1 N294 cleavage in neurons, we prepared primary cultures and treated neurons with 2 μM Aβ42 for 24 h. IF co-staining revealed that Aβ treatment greatly increased BACE1 N294 levels when compared with control, which were co-localized with LAMP1, EEA1 and GGA-3, respectively (Figure 5C). The subcellular residency of GFP-tagged BACE1 FL, 1–294 fragment or uncleavable N294A construct was further validated in transfected HEK293 cells with the specific biomarkers (Supplemental Figure 6A–D). Again, Aβ stimulation escalated both delta-secretase and BACE1 N294 in primary neurons (Supplementary Figure 6E). Thus, delta-secretase and BACE1 and APP mostly co-localize in the endo-lysosomes in the AD mouse brains, where they are truncated by delta-secretase.

Figure 5: Delta-secretase and BACE1 co-localize in the endo-lysosomes.

(A) Delta-secretase and BACE1 distribution in the subcellular fractions. Brain samples from 9-month-old WT and age-matched 5XFAD mice were homogenated and fractionated on a discontinuous sucrose gradient. The fractions were analyzed by WB (left) for AEP, BACE1, BACE1 fragments, APP, APP fragments, EEA1 (endosome marker), GGA3 (trans-Golgi network maker) and LAMP1 (lysosome marker). The relative amount of BACE1 N294, EEA1, GGA3 and LAMP1 in each fraction was quantified (right). Data represent mean ± SEM. of 3 mice in each group (*P<0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test, compared with WT mice). (B) Delta-secretase and BACE1 distribution in the cell organelles. Brain samples from 12-month-old WT and age-matched AEP−/− mice were homogenated and fractionated with gradient density centrifugation. The fractions were analyzed by WB for AEP, BACE1, BACE1 fragments, APP, APP fragments, Histone H3 (nucleus marker), TOMM20 (mitochondria marker), LAMP1 (lysosome marker), GGA3 (trans-Golgi network maker), ERp57 (endoplasmic reticulum marker), EEA1 (endosome marker) and TrkB (cell membrane marker). (C) BACE1 N294 co-localizes with LAMP1, EEA1 and GGA3. Primary neuronal cultures (DIV. 14) were treated with DMSO or 2 μM of pre-aggregated Aβ for 24 h, followed by immunostaining with various antibodies including anti-BACE1 N294, anti-LAMP1, anti-EEA1 and anti-GGA3. Scale bar, 20 μm.

BACE1 N294 facilitates senile plaque deposition and elevates cognitive deficits

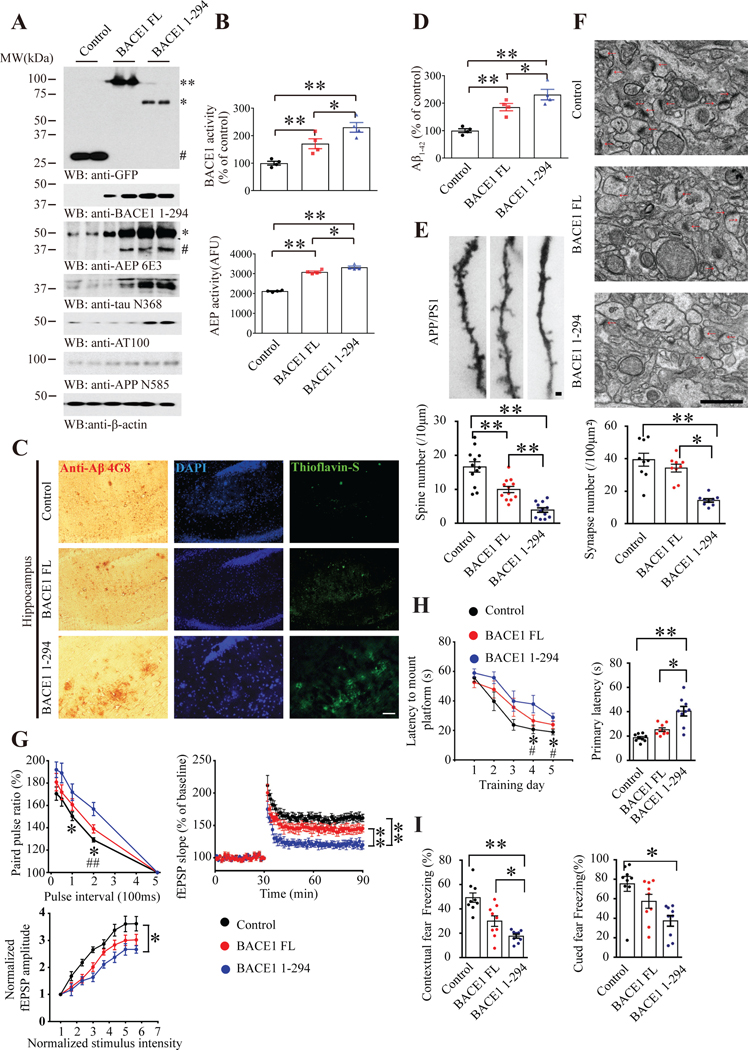

To investigate the pathological role of BACE1 N294, we injected lentivirus expressing BACE1 N294 into the hippocampus of 6 months old APP/PS1 mice. In addition, we also injected virus expressing BACE1 FL and control virus, respectively. Two months later, mice were sacrificed and the virus expression was verified on brain sections by IF. The proteins were mainly expressed in CA1 and spread throughout the hippocampus and a portion of the cortex (Supplementary Figure 7A). In addition, we monitored BACE1 expression by immunoblotting, and found that both FL BACE1 and BACE1 N294 were robustly expressed, and a portion of BACE1 FL was cleaved into BACE1 N294. Remarkably, BACE1 N294 strongly elevated delta-secretase, which was potently activated. Compared to control virus, BACE1 FL also increased delta-secretase but the extent was not as robustly as BACE1 N294. Consequently, both APP N585 and Tau N368 was prominently cleaved in BACE1 N294 mice, so were phosphor-Tau AT100 activities and C99 (70–80) levels, fitting with delta-secretase activation pattern. Another BACE1 substrate CHL-1 showed the similar pattern to APP, and aggregated Aβ was highly increased in BACE1 N294 mice (Figure 6A, Supplementary Figure 7B). BACE1 enzymatic assay showed that BACE1 N294 exhibited the strongest enzymatic activity, followed by BACE1 FL and then control (Figure 6B, upper panel). As expected, delta-secretase enzymatic assay displayed the similar pattern (Figure 6B, lower panel), consistent with its mature levels by immunoblotting. IHC staining showed that BACE1 N294 elicited more plentiful Aβ deposits in both the cortex and the hippocampus than BACE1 FL, which was a bit more copious than control. Thioflavine S also validated abundant senile plaques in BACE1 N294 samples, echoing IHC staining results (Figure 6C, supplementary figure 7D). Aβ40 and Aβ42 ELISA mirrored BACE1 enzymatic findings (Figure 6D, Supplementary Figure 7C). Golgi staining and IF demonstrated the fewest dendritic spines in BACE1 N294 brains, and BACE1 FL also decreased the spines as compared with control (Figure 6E, Supplementary Figure 7E). Electronic microscopy (EM) showed that BACE1 N294 significantly reduced the synapses when compared with control (Figure 6F). Electrophysiological analysis revealed that LTP (long-term potentiation) and paired-pulse ratio (PPR) were demonstrably reduced in BACE1 N294 mice (Figure 6G). In alignment with these findings, Morris Water Maze (MWM) behavioral tests found that BACE1 N294 considerably decreased the latency during the training course, and it also evidently increased the primary latency, supporting that BACE1 N294 diminished the spatial memory of APP/PS1 mice as compared with control. The swim speed was comparable among the groups, indicating that BACE1 does not affect the motor functions (Figure 6H, supplementary figure 7F–G). Fear conditioning test also showed the same results (Figure 6I). Therefore, BACE1 N294 highly increases Aβ production and elicits senile plaques deposition, leading to synaptic degeneration and cognitive deficits.

Figure 6: BACE1 N294 facilitates senile plaque deposition and elevates cognitive deficits.

(A) BACE1 N294 expression induces delta-secretase activation and APP and Tau cleavage. Western blot analysis of BACE1, delta-secretase, Tau and APP cleavage by delta-secretase in APP/PS1 mice CA1 infected with lentivirus expressing BACE1 FL or fragment. AEP-cleaved BACE1 fragment elevated delta-secretase cleavage. 1st panel: ** BACE1 FL-GFP, *endogenous BACE1 1–294-GFP, # GFP. 3rd panel: * full-length AEP, # cleaved AEP (active or mature form). (B) BACE1 and delta-secretase enzymatic assays. Beta-secretase (upper) and delta-secretase activity in cleaved-BACE1-expressed APP/PS1 mice CA1. AEP-truncated BACE1 escalated both beta-/delta-secretase activities. Data represent mean ± SEM. of 4 mice in each group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (C) Amyloid plaques are increased in cleaved-BACE1-expressed APP/PS1 mice. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of Aβ (left) and Thioflavin S staining (right) showing the Aβ plaques in the hippocampus. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Truncated BACE1 escalates Aβ1–42 level. Aβ1–42 ELISA represent mean ± SEM of 4 mice per group (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (E) BACE1 cleavage by delta-secretase decreases the dendritic spine density. Upper, Golgi staining was conducted on brain sections from BACE1 WT or truncated BACE1 overexpressed apical dendritic layer of the CA1 region. Scale bar, 1μm. Bottom, quantification of spine density represents mean ± SEM. of 12 sections from 3 mice in each group. (**P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (F) BACE1 cleavage by delta-secretase decreases the number of synapses in CA1 region of APP/PS1 mice. Electron microscopy analysis of synapses (upper panels, n = 3 mice per group). Scale bar, 1 μm. Quantitative analysis of synapses in CA1 (bottom panels, mean ± SEM. of 9 sections from 3 mice per group; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). Arrows indicate the synapses. (G) Electrophysiology analysis. Truncated BACE1 (1–294) overexpression in CA1 worsened the LTP defects in APP/PS1 mice. The ratio of paired pulses in different groups (mean ± SEM.; n = 6 in each group; *P < 0.05 BACE1 1–294 compared with Control, ##P<0.01 BACE1 1–294 compared with BACE1 FL, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test) (upper, left). LTP of fEPSPs (mean ± SEM.; n = 6 in each group; **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test) (upper, right). Input-output curve represent mean ± SEM. of 6 mice per group (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (H) Morris Water Maze analysis of cognitive functions. AEP-cleaved BACE1 overexpression in the CA1 exacerbated the learning and memory dysfunctions in APP/PS1 mice (mean ± SEM.; n = 8–10 mice per group; *P< 0.05 BACE1 1–294 vs. Control, #P<0.05 BACE1 1–294 compared with BACE1 FL, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (I) Fear condition tests. Contextual and cued fear memory was reduced in AEP-truncated BACE1 expressed mice (mean ± SEM.; n = 8–10 mice per group; *P < 0.05, **P<0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). See also Supplementary Figure 7.

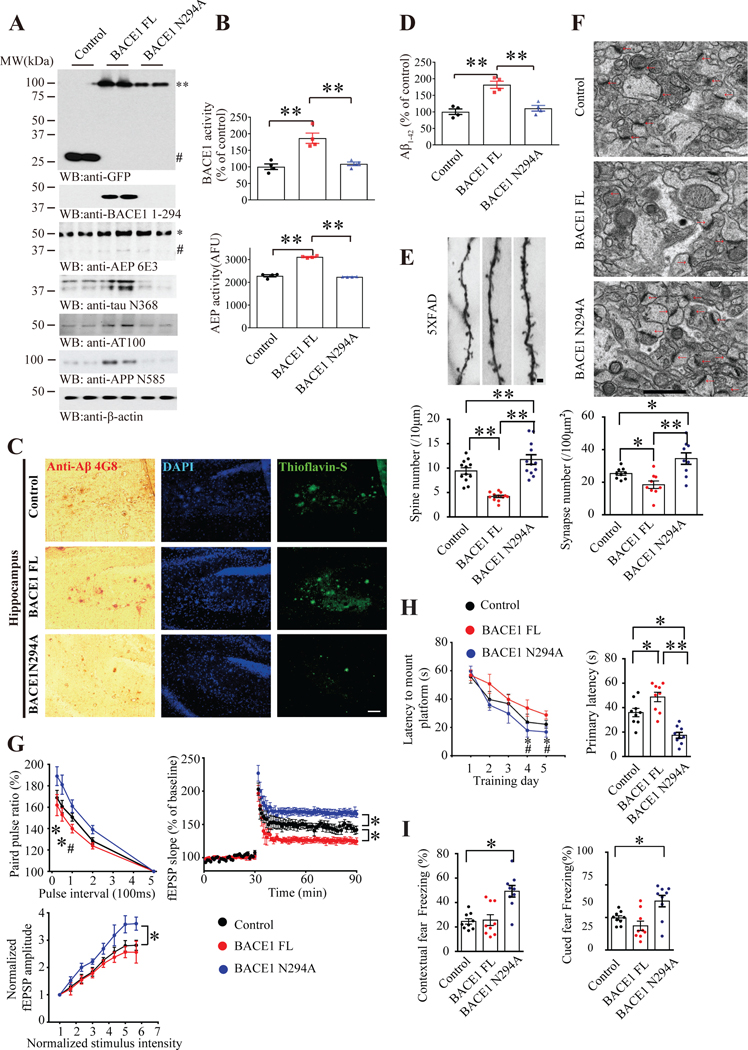

Uncleavable BACE N294A diminishes Aβ production and mitigates cognitive defects

To interrogate in-depth the pathological role of delta-secretase cleavage of BACE1 in AD pathologies, we employed 2 months old 5XFAD mice and administrated lentivirus expressing uncleavable BACE1 N294A or BACE1 FL into the hippocampus, respectively. Two months later, mice were sacrificed and the virus expression was verified on the brain sections by IF. The proteins were mainly expressed in CA1 and spread throughout the hippocampus and a part of the cortex (Supplementary Figure 8A). In addition, we examined BACE1 and delta-secretase expression by immunoblotting. As expected, delta-secretase was weakly activated by BACE1 FL, which also partially yielded BACE1 N294. Consequently, APP N585 and Tau N368 were cleaved in BACE1 FL samples compared to control, and it was greatly blocked in BACE1 N294A brains. Tau N368 abundance tightly coupled with Tau phosphorylation, as demonstrated by AT100 and C99 (70–80) activities. Further, cleaved CHL-1 was significantly decreased in BACE1 N294A group vs. BACE1 FL, and aggregated Aβ was also reduced in BACE1 N294A mice (Figure 7A, Supplementary Figure 8B). BACE1 activities were significantly augmented in BACE1 overexpressed samples than control and uncleavable mutant (Figure 7B, upper panel). Delta-secretase activity essentially echoed BACE1 enzymatic activities (Figure 7B, lower panel), correlating with its active form levels. IHC staining with anti-Aβ showed that BACE1 increased Aβ aggregation as compared with control. However, the signals were strongly reduced in BACE1 N294A hippocampus. Thioflavine S staining disclosed the same pattern. We made the similar observations with the cortex (Figure 7C, supplementary figure 8D). ELISA analysis revealed Aβ40 and Aβ42 concentrations tightly coupled with BACE1 enzymatic activity in the brains (Figure 7D, Supplementary Figure 8C). In alignment with these findings, the dendritic spines in BACE1 N294A brain were obviously increased as compared with control, however, BACE1 FL largely decreased the spines (Figure 7E, Supplementary Figure 8E). Moreover, EM study indicated that uncleavable mutant N294A significantly elevated synapses compared to control (Figure 7F). Electrophysiology analysis showed that LTP and PPR were escalated in BACE1 N294A samples as compared to control and BACE1 FL (Figure 7G). MWM tests demonstrated that uncleavable N294A mice exhibited the best spatial memory, and the mice spent significantly less time of primary latency in the probe test. The swim speed was comparable among the groups, indicating that BACE1 N294A does not affect the motor functions (Figure 7H, supplementary figure 8F–G). Fear conditioning test also supported this finding (Figure 7I). Together, our data strongly support that delta-secretase uncleavable BACE1 N294A mutant losses its enzymatic activity and diminishes Aβ generation, mitigating cognitive deficits in 5XFAD mice.

Figure 7: Uncleavable BACE N294A diminishes Aβ production and mitigates cognitive defects.

(A) Uncleavable BACE1 N294A inhibits delta-secretase activation. Western blot analysis of BACE1, delta-secretase, Tau and APP cleavage by delta-secretase in 5×FAD mice CA1 infected with lentivirus expressing BACE1 FL or AEP-uncleavable BACE1 mutant (N294A). Blocking of BACE1 cleavage by AEP reduced delta-secretase cleavage. 1st panel: ** GFP-BACE1 FL-GFP or BACE1 N294A-GFP, # GFP. 3rd panel: * full-length AEP, # cleaved AEP (active or mature form). (B) BACE1 and delta-secretase enzymatic assays. Beta-secretase (upper) and delta-secretase activity in uncleavable BACE1-expressed 5XFAD mice CA1. Uncleavable BACE1 reduced both beta-/delta-secretase activities. Data represent mean ± SEM of 4 mice in each group (**P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (C) Amyloid plaques are decreased in BACE1 N294A-expressed 5XFAD mice. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining of Aβ (left) and Thioflavin S staining (right) showing the Aβ plaques in the hippocampus. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Aβ1–42 level is decreased in BACE1 N294A-expressed 5XFAD mice. Aβ1–42 ELISA represent mean ±SEM. of 4 mice per group (**P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (E) Blocking BACE1 cleavage by delta-secretase rescues the loss of dendritic spine density. Upper, Golgi staining was conducted on brain sections from BACE1 FL or N294A expressed apical dendritic layer of the CA1 region. Scale bar, 1μm. Bottom, quantification of spine density represents mean ± SEM. of 9–12 sections from 3 mice in each group. (**P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (F) Blockade of BACE1 cleavage by delta-secretase increases the number of synapses in CA1 region of 5XFAD mice. Electron microscopy analysis of synapses (upper panels, n = 3 mice per group). Scale bar, 1 μm. Quantitative analysis of synapses in CA1 (bottom panels, mean ± SEM. of 9 sections from 3 mice per group; *P < 0.05, **P<0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). Arrows indicate the synapses. (G) Electrophysiology analysis. Uncleavable BACE1 (N294A) expression in CA1 rescued the LTP dysfunction in 5XFAD mice. The ratio of paired pulses in different groups (mean ± SEM.; n = 6 in each group; *P < 0.05 BACE1 N294A compared with Control, #P<0.05 BACE1 N294A compared with BACE1 FL, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test) (upper, left). LTP of fEPSPs (mean ± SEM.; n = 6 in each group; **P < 0.01, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test) (upper, right). Input-output curve represent mean ± SEM. of 6 mice per group (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). (H) Morris Water Maze analysis of cognitive functions. Uncleavable BACE1 expression in the CA1 reversed the learning and memory dysfunctions in 5XFAD mice (mean ± SEM; n = 8–10 mice per group; *P< 0.05, **P<0.01, #P<0.05 BACE1 N294A compared with BACE1 FL, one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s multiple comparison test). (I) Fear condition tests. Contextual and cued fear memory was rescued in uncleavable BACE1 expressed mice (mean ± s.e.m.; n = 8–10 mice per group; *P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA). See also Supplementary Figure 8.

Discussion

Our study establishes that delta- and beta- secretases cross talk to each other and mutually elevate the protease activities, increasing Aβ generation, APP N585 and Tau N368 cleavage in AD pathogenesis. We show that these two crucial secretases interact with each other in the endolysosomes organelles, where the acidic lumen activates delta-secretase, which subsequently cleaves APP at N373 and N585 residues and BACE1 at N294 site. Conceivably, active BACE1 (a.a. 1–294) in turn shreds the resultant APP (a.a. 586–695) fragment at the β-site in the endosomes or trans-Golgi network (TGN). Interestingly, we found that the truncated N-terminal fragment of BACE1 and delta-secretase associate with extracellular senile plaques in human AD brains, indicating that after the proteolytic cleavage, truncated BACE1 catalytic domain (a.a. 1–294) may be dumped into the extracellular space via the secretory pathway. Our findings are consistent with previous reports. For instance, co-expression of APP and the soluble ectodomain of BACE1 in cells increase the generation of Aβ, suggesting the enhanced BACE1 ectodomain shedding may raise amyloidogenic processing of APP(Benjannet et al., 2001). Interestingly, active and soluble BACE1 has been detected in human CSF(Verheijen et al., 2006), a finding that raises the potential use of BACE1 detection in an easily accessible biological fluid, such as CSF, in future diagnostic or prognostic applications. Further, replacing the BACE1 transmembrane domain with a glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor exclusively targets BACE1 to lipid rafts and substantially increases Aβ production(Cordy et al., 2003). Notably, truncated BACE1 (a.a. 46–294) displays the enzymatic activities even under neutral pH, whereas FL counterpart only reveals the enzymatic activity under pH below 5.5 (Figure 3B). Since the truncated fragment is secreted extracellularly, co-localizing with senile plaques (Figure 4A), presumably, the released N-terminal BACE1 (a.a. 46–294) may shred APP at β-site on the plasma membrane extracellularly even under neutral pH.

We have previously reported that delta-secretase is age-dependently upregulated and activated in human brains(Zhang et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2015). Here we show that both beta- and delta-secretases are progressively escalated with aging, and truncated BACE1 N294 is gradually augmented, tightly correlating with escalated APP C586 fragment by delta-secretase in both mouse and human brains (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 3H). Employing subcellular fractionation with wild-type, 5XFAD and delta-secretase KO mouse brains, we show that delta-secretase and BACE1 co-distribute in the lysosomes and the endosomes, where BACE1 N294 proteolytic cleavage primarily takes place. Knockout of delta-secretase completely abolishes BACE1 N294 fragmentation (Figure 5). Furthermore, utilizing IF staining with various specific biomarkers for the cellular organelles, we reveal that BACE1 N294 fragment resides in the EEA1, LMAP1 and GGA3 positive compartments in 5×FAD mice, which stands for the endolysosomes and the TGN, respectively (Figure 5, Supplementary Figure 6A–C).

BACE1 plays an indispensable role in Aβ generation. Elevated levels of BACE1 have been directly correlated with Aβ-induced pathology in AD brains(Fukumoto et al., 2002; Yang et al., 2003). To explore whether BACE1 might cut delta-secretase, we performed biochemical assay using wild-type delta-secretase, and various mutants including enzymatic-dead C189S, N323A and K289R mutants. Though APP is strongly cleaved by both BACE1 (M596) and delta-secretase (N585), none of delta-secretase proteins is cleaved by BACE1, suggesting that delta-secretase may not be a substrate of BACE1 (Supplementary Fig 9). However, delta-secretase activity is decreased in BACE1 KO mice brains as compared to WT (Supplementary Figure 9), suggesting that BACE1 might indirectly affect its activity. It is worth noting that both WT delta-secretase and K289R mutants possess autocleavage activity, yielding the mature form, whereas neither C189S nor uncleavable N323A mutant was truncated into the mature form. Remarkably, the truncated delta-secretase band concentrations were elevated in the presence of GFP-BACE1 WT or GFP-BACE1 N294 as compared to GFP-control, suggesting that BACE1 N-terminus somehow stimulates delta-secretase enzymatic activity, resulting it augmented autocleavage (Supplementary Figure 9). This catalytic effect is probably mediated by augmented Aβ, which has been shown to activate delta-secretase(Zhang et al., 2015). Interestingly, we found that Aβ stimulation augments both delta-secretase and BACE1 protein levels in primary neurons (Figure 1D), indicating that Aβ may feedback to escalate the two upstream amyloidogenic secretases, amplifying the vicious cycle. Noticeably, Co-IP assays demonstrate that both BACE1 FL and truncated N-terminal BACE1 (a.a. 1–294) fragment associate with delta-secretase in the transfected cells and human AD brains (Supplementary Figure 2F and Figure 1F). IF staining also indicates that delta-secretase co-localizes with both BACE1 and truncated BACE1 N294 in the cells (Figure 1D, supplementary Figure 6E) and cortex and hippocampus of human AD brains (Figure 4, Supplementary Figure 3). As the disease progresses (Braak II to VI), more and more delta-secretase, BACE1 and BACE1 N294 are identified and tightly co-localize in AD frontal cortex (Figure 4), fitting with the observation that Aβ treatment augments both delta-secretase and BACE1/BACE1 N294 protein levels (Figure 1D and Supplementary Figure 6E).

We show that APP cleavage at N585 accelerates Aβ production, presumably due to alleviation of the steric hindrance on the extracellular domains of APP to allow BACE1 to get access more readily to cut at β-site (Zhang et al., 2015). In the current work, we show that delta-secretase cleaves BACE1 at N294 and the resultant N-terminal protease domain possesses elevated enzymatic activity, promoting Aβ production (Figure 1–3). It is worth noting that BACE1 (a.a.1–294) also augments delta-secretase activity; in contrast, AEP-uncleavable BACE1 (N294A) or the C-terminal BACE1 (a.a.295–501) displays no β-secretase activity and inhibits delta-secretase activation. From in vitro (Fig. 3F) and in vivo (Fig. 7B) data, we find that BACE1 enzymatic activities show no change as compared with control, confirming that BACE1 N294A mutant possesses no enzymatic activity. However, we cannot distinguish which of the following two possibilities accounting for the effect: lack of BACE1 cleavage by AEP or inactivation of BACE1 enzymatic activity due to the point mutation too close to the active site. BACE1 is an aspartic protease. There are two separate aspartic protease active site motifs of the sequence DTGS (residues 93–96) and DSGT (residues 289–292) in BACE1, and mutation of either aspartic acid renders the enzyme inactive(Hussain et al., 1999). Crystal structure of an active form of BACE1 shows that both Asp residues bind to one H2O under pH 4.0 ~ 5.0, which is implicated in hydrolyzing the C-N bond in the substrate. Moreover, Y71 residue in the loop domain mediates the flap conformation and the substrate binding(Shimizu et al., 2008). Four Asn residues (153, 172, 223, 354) but not Asn (N) 294 are N-glycosylated on BACE1(Haniu et al., 2000). Extensive mutagenesis has been conducted on BACE1 and none of these studies reveals that N294 is implicated in the enzymatic activity(Hampel et al., 2021), and X-ray crystal studies also do not support that N294 is crucial for the substrate binding or C-N bond hydrolysis(Hong et al., 2000). Hence, there is not any data supporting that N294A mutation might abrogate BACE1 enzymatic activity. Presumably, N294A mutation disrupts BACE1 protease activity might not be due to its proximity to the active DSGT enzyme site, because this residue is not implicated in the substrate binding or hydrolysis. Moreover, BACE1 1–294 truncation enhances its enzymatic activity at both pH 4.5 and 7.5, instead of demolishing the protease activity, underscoring the modification at this site even elevates protease activity. Together, our in vitro and in vivo data strongly support that proteolytic cleavage at N294 by AEP might be prerequisite for BACE1 activation. Nevertheless, delta-secretase-truncated BACE1 1–294 fragment displays highly enhanced enzymatic activity (Fig 3 & 6). Given that BACE1 plays a rate-limiting role in Aβ generation, probably, inhibition of delta-secretase will strongly antagonize Aβ peptide production. As expected, most recently, we identified a small molecular delta-secretase inhibitor compound #11 via high throughput screening, which is orally bioactive and brain permeable. Oral administration of this compound selectively reduces APP N373/N585 and Tau N368 cleavage by delta-secretase, resulting in decrease of senile plaques in 5XFAD and NFT aggregation in Tau P301S mice(Zhang et al., 2017). In addition, knockout of delta-secretase from 5XFAD or WT mice blocks BACE1 N294 cleavage (Supplementary Figure 2G, Figure 3G), diminishing Aβ40 and Aβ42 production and senile plaques deposition(Zhang et al., 2015). Hence, δ- and β- secretases cross talk to each other amplify the AD pathogenesis.

Conclusions

Our data demonstrate that delta-secretase binds and cuts BACE1 at N294 residue in the endolysosomes and elevates its enzymatic activity, leading to upregulation of amyloid-β production. Aβ in turn feeds back and escalates both δ and β-secretase protein levels, amplifying the detrimental pathway. Together, these findings strongly support the notion that delta-secretase may act upstream of amyloidogenic pathway and mediate BACE1, APP and Tau proteolytic fragmentation, dictating both senile plaques and NFT pathologies in AD pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Delta-secretase interacts with BACE1 and cleaves it in the endo-lysosomes.

BACE1 N294 fragment displays higher enzymatic activity than full-length counterpart, stimulating δ-secretase activation.

BACE1 N294 fragment is secreted extracellularly and associates with senile plaques.

BACE1 N294 is active even under pH 7.4, indicating that it may cleave APP in the extracellular space.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from NIH RO1 (AG051538) to K. Y., and grant from National Natural Science Foundation (NSFC) of China (No. 81528007) to J.Z.W. We thank ADRC at Emory University for human AD patients and healthy control samples (P30 AG066511). The virus was prepared by Emory Viral Core Facility. This study was supported in part by the Rodent Behavioral Core (RBC), which is subsidized by the Emory University School of Medicine and is one of the Emory Integrated Core Facilities. BACE1 KO brain tissues were got from Prof. Riqiang Yan as a gift. Additional support was provided by the Emory Neuroscience NINDS Core Facilities (P30NS055077). Further support was provided by the Georgia Clinical & Translational Science Alliance of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number UL1TR002378. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference:

- Bao J, Qin M, Mahaman YAR, Zhang B, Huang F, Zeng K, Xia Y, Ke D, Wang Q, Liu R, Wang JZ, Ye K, Wang X, 2018. BACE1 SUMOylation increases its stability and escalates the protease activity in Alzheimer’s disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 115, 3954–3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjannet S, Elagoz A, Wickham L, Mamarbachi M, Munzer JS, Basak A, Lazure C, Cromlish JA, Sisodia S, Checler F, Chretien M, Seidah NG, 2001. Post-translational processing of beta-secretase (beta-amyloid-converting enzyme) and its ectodomain shedding. The pro- and transmembrane/cytosolic domains affect its cellular activity and amyloid-beta production. The Journal of biological chemistry 276, 1087910887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capell A, Steiner H, Willem M, Kaiser H, Meyer C, Walter J, Lammich S, Multhaup G, Haass C, 2000. Maturation and pro-peptide cleavage of beta-secretase. The Journal of biological chemistry 275, 30849–30854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JM, Dando PM, Rawlings ND, Brown MA, Young NE, Stevens RA, Hewitt E, Watts C, Barrett AJ, 1997. Cloning, isolation, and characterization of mammalian legumain, an asparaginyl endopeptidase. The Journal of biological chemistry 272, 8090–8098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SL, Vassar R, 2007. The Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase enzyme, BACE1. Molecular neurodegeneration 2, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordy JM, Hussain I, Dingwall C, Hooper NM, Turner AJ, 2003. Exclusively targeting beta-secretase to lipid rafts by GPI-anchor addition up-regulates beta-site processing of the amyloid precursor protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100, 11735–11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dall E, Brandstetter H, 2013. Mechanistic and structural studies on legumain explain its zymogenicity, distinct activation pathways, and regulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 110, 10940–10945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ermolieff J, Loy JA, Koelsch G, Tang J, 2000. Proteolytic activation of recombinant pro-memapsin 2 (pro-beta-secretase) studied with new fluorogenic substrates. Biochemistry 39, 12450–12456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto H, Cheung BS, Hyman BT, Irizarry MC, 2002. Beta-secretase protein and activity are increased in the neocortex in Alzheimer disease. Archives of neurology 59, 1381–1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukumoto H, Rosene DL, Moss MB, Raju S, Hyman BT, Irizarry MC, 2004. Beta-secretase activity increases with aging in human, monkey, and mouse brain. The American journal of pathology 164, 719–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampel H, Vassar R, De Strooper B, Hardy J, Willem M, Singh N, Zhou J, Yan R, Vanmechelen E, De Vos A, Nistico R, Corbo M, Imbimbo BP, Streffer J, Voytyuk I, Timmers M, Tahami Monfared AA, Irizarry M, Albala B, Koyama A, Watanabe N, Kimura T, Yarenis L, Lista S, Kramer L, Vergallo A, 2021. The beta-Secretase BACE1 in Alzheimer’s Disease. Biol Psychiatry 89, 745–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haniu M, Denis P, Young Y, Mendiaz EA, Fuller J, Hui JO, Bennett BD, Kahn S, Ross S, Burgess T, Katta V, Rogers G, Vassar R, Citron M, 2000. Characterization of Alzheimer’s beta -secretase protein BACE. A pepsin family member with unusual properties. The Journal of biological chemistry 275, 21099–21106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong L, Koelsch G, Lin X, Wu S, Terzyan S, Ghosh AK, Zhang XC, Tang J, 2000. Structure of the protease domain of memapsin 2 (beta-secretase) complexed with inhibitor. Science 290, 150–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse JT, Byant D, Yang Y, Pijak DS, D’Souza I, Lah JJ, Lee VM, Doms RW, Cook DG, 2003. Endoproteolysis of beta-secretase (beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme) within its catalytic domain. A potential mechanism for regulation. The Journal of biological chemistry 278, 17141–17149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huse JT, Pijak DS, Leslie GJ, Lee VM, Doms RW, 2000. Maturation and endosomal targeting of beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme. The Alzheimer’s disease beta-secretase. The Journal of biological chemistry 275, 33729–33737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain I, Powell D, Howlett DR, Tew DG, Meek TD, Chapman C, Gloger IS, Murphy KE, Southan CD, Ryan DM, Smith TS, Simmons DL, Walsh FS, Dingwall C, Christie G, 1999. Identification of a novel aspartic protease (Asp 2) as beta-secretase. Mol Cell Neurosci 14, 419–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh YH, von Arnim CA, Hyman BT, Tanzi RE, Tesco G, 2005. BACE is degraded via the lysosomal pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry 280, 32499–32504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X, Koelsch G, Wu S, Downs D, Dashti A, Tang J, 2000. Human aspartic protease memapsin 2 cleaves the beta-secretase site of beta-amyloid precursor protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 97, 1456–1460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Jang SW, Liu X, Cheng D, Peng J, Yepes M, Li XJ, Matthews S, Watts C, Asano M, Hara-Nishimura I, Luo HR, Ye K, 2008. Neuroprotective actions of PIKE-L by inhibition of SET proteolytic degradation by asparagine endopeptidase. Molecular cell 29, 665–678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]