Abstract

Purpose:

The Expanded Prostate Cancer Index-Short Form (EPIC-26) is a validated questionnaire for measuring health-related quality-of-life. However, the relationship between domain scores and functional outcomes remains unclear, leading to potential confusion about expectations after treatment. For instance, does a sexual function domain score of 80 mean a patient can obtain an erection sufficient for intercourse? Consequently, we sought to determine the relationship between domain score and response to obtaining the best possible outcome for each question.

Materials and Methods:

Utilizing data from the Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation Study, a multicenter, prospective study of men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer, we analyzed 11,464 EPIC-26 questionnaires from 2,563 men at baseline through 60 months of follow-up who were treated with robotic prostatectomy, radiotherapy, or active surveillance. We dichotomized every item into its best possible outcome and assessed the percentage at each domain score who obtained the best result.

Results:

For every EPIC-26 item, the frequency of best possible outcome was reported by domain score category. For example, a score of 80-100 on sexual function corresponded to 97% of men reporting erections sufficient for intercourse, whereas at 40-60, only 28% reported adequate erections. Meanwhile, at 80-100 on the urinary incontinence domain, 93% reported rarely or never leaking versus 6% at 61-80.

Conclusion:

Our findings show a novel way to interpret EPIC-26 domain scores, demonstrating large variations in the percentage reporting best possible outcomes over narrow domain score differences. This information may be valuable when counseling men on treatment options.

Keywords: Prostate cancer, patient-reported function, comparative effectiveness, health-related quality of life, questionnaires

Introduction:

Despite continuous advances in the detection and treatment of localized prostate cancer, the long-term survival between varying treatment options remains similar.[1–6] As a result, patients and providers alike have placed increasing importance on the risks of treatment and longitudinal health-related quality of life (HRQOL) outcomes.[7,8] Although many analyses exist, most have used retrospective, cross-sectional data and/or lacked baseline data, the latter of which is helpful in predicting posttreatment outcomes.[9–11] Furthermore, misinterpretation of scores is frequent, and clinical interpretability is often poor with physicians and patients unsure of what the scores actually mean.[12]

In order to bridge the gap between the research and clinical applicability of measuring functional outcomes, the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC)-26, a 26-item patient reported outcome (PRO) questionnaire, has been frequently used to assess HRQOL before and after treatment for prostate cancer.[13,14] Measuring urinary incontinence, urinary irritation, and sexual, bowel, and hormonal function, this questionnaire is convenient to use in practice and has good internal consistency, reliability, and discriminative validity.[13–15] Nevertheless, despite being widely disseminated, its clinical interpretability remains elusive. For example, if a patient’s sexual function domain score is 80, what is the probability of that patient obtaining an erection sufficient for intercourse?

In this study, we analyzed the relationship between individual best-item responses and domain score for several thousand EPIC-26 questionnaires within a longitudinal cohort study of men with localized prostate cancer[16]. In essence, by translating these domain scores into a probabilistic outcome, e.g., helping patients understand the likelihood of retaining or regaining erections firm enough for intercourse, we sought to enrich both patients’ and providers’ expectations with varying treatments for all clinically relevant outcomes of the EPIC-26.

Materials and Methods:

Analytical Cohort

The Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation (CEASAR) study is a multicenter, longitudinal, prospective, population-based, observational study of men diagnosed with localized prostate cancer in 2011 to 2012, designed to measure the impact of contemporary treatment strategies on functional outcomes (NCT0136286). The CEASAR methodology has been previously described.[17] Briefly, eligibility criteria included men <=80 years of age with clinical cT1 or cT2 disease, a prostate specific antigen (PSA) level of <50 ng/dl, no nodal involvement or metastases on clinical evaluation, were enrolled within 6 months of diagnosis, and underwent robotic-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy (RALP), external beam radiotherapy (EBRT), or active surveillance (AS). Patient-reported outcomes including the EPIC-26 survey were collected via mail survey at enrollment, and at 6, 12, 36, and 60 months after enrollment. This study includes follow-up through September 2018. All sites obtained approval from their local institutional review boards.

EPIC-26

The primary outcome measure for the CEASAR study was patient-reported, disease-specific function as measured by the 26-item EPIC questionnaire. In particular, the EPIC-26 measures sexual function, bowel function, hormone therapy side effects, urinary incontinence and urinary irritative/obstructive symptoms. The 26 individual items have 4 to 5 response options reflecting a range of function from poor to excellent (Supplementary Figure 1). Responses to individual items are scaled from 0 to 100, and the domain score is computed as an average of scores for the questions within that domain. Thus, the domain score is a continuous scale ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better function. Previously, studies estimated the “minimum clinically important difference (MCID)” between scores, that is the change in score that would be noticeable to the patient (hormone domain, 4-6 points; urinary irritative, 5-7; urinary incontinence, 6-9; sexual, 10-12), to aid in interpretation.[18,19] Although urinary bother is part of both the urinary incontinence and irritative domains, we felt this was important to include and listed it as part of the urinary irritative domain for classification purposes.

In order to delineate the percentage of men who had the best possible outcome to each question across the range of domain scores, each question was dichotomized into best outcome versus any other response. For example, we dichotomized “How would you describe the usual QUALITY of your erections over the last 4 weeks?” into the best possible response “Firm enough for intercourse” versus any lesser response.

In addition to analyzing all 26 questions for interpretation of score, we singled out “key items” based on their clinical relevance to the patient advisory panel and prostate cancer providers on our research team. Overall, pad use, frequency of leakage, quality of erections, and whether an erection was sufficient for intercourse were deemed the most clinically relevant questions and subsequently assessed in more detail in this manuscript.

Statistical analysis

Patients’ demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized with median and quartiles for continuous variables or frequency and percentage for categorical variables. For each of the EPIC-26 functional items, the frequency (percentage) of the best possible outcome was reported by domain score category (0-20, 21-40, 41-60, 61-80, 81-100). In order to translate a functional domain score into a more intuitive specific functional item, we used logistic regression models from all data time points to estimate the likelihood of having the best possible outcome for each item, using functional domain score (range from 0-100) as a continuous predictor. To account for inclusion of the correlated data (collected at multiple surveys) for each participant, generalized estimation equation (GEE) method was applied. To visualize the relationship between the domain score with each EPIC-26 item, the logistic-regression-predicted probability of having the best possible outcome was plotted against the corresponding domain score. In a sensitivity analysis estimating the likelihood of having the best two possible outcomes for each of the EPIC-26 items, the same approach was used. We assumed the relationship between domain score and specific items did not change over time or by treatment, and combined the data from various surveys in fitting the logistic regression models. Statistical significance was considered for all two-sided p values ≤ 5%. All analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.[20]

Results:

Patient characteristics and demographics

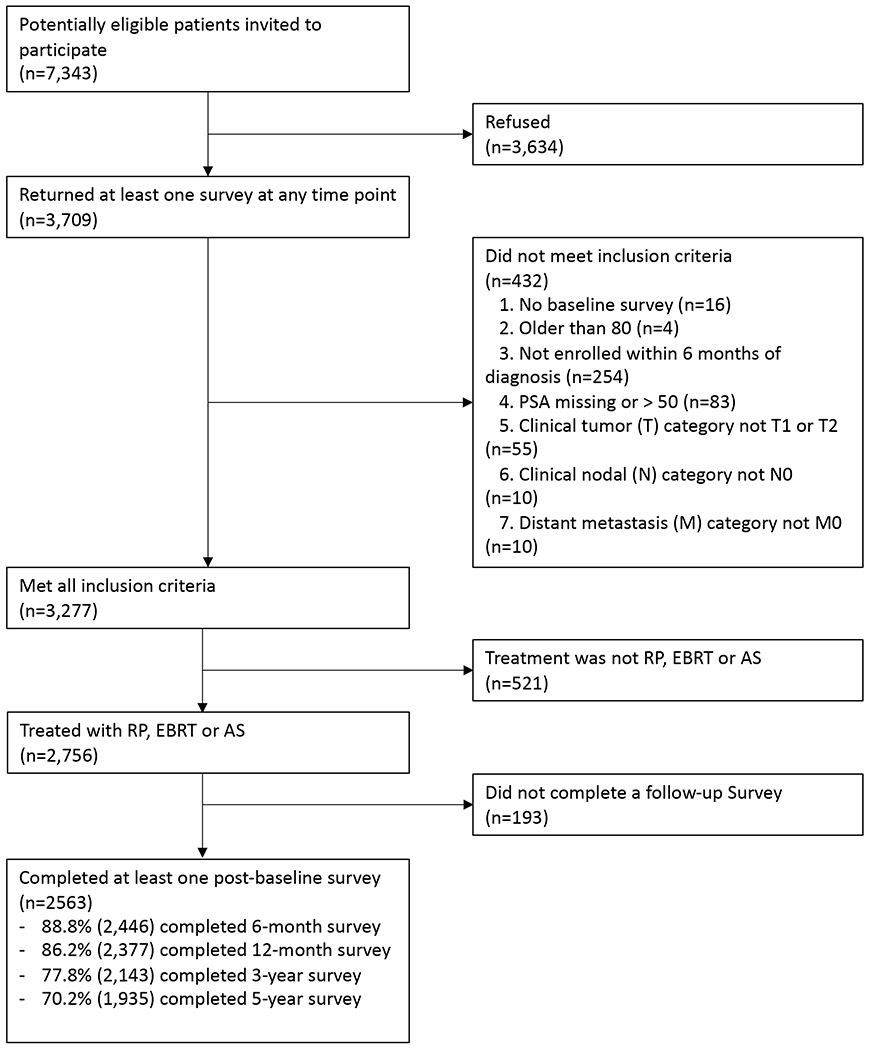

The parent CEASAR study accumulated 3,709 men, of whom 432 were excluded for failing to meet the inclusion criteria. Additionally, 521 additional men were excluded for receiving a treatment other than AS, EBRT, or RALP, leaving 2,756 men for consideration. Among these men, 2,563 (93%) completed a baseline survey and at least 1 survey thereafter and were included in the current study. Survey response rates were 89% (n=2,446) at 6 months, 86% (n=2,377) at 12 months, 78% (n=2,143) at 36 months, and 70% (n=1,935) at 60 months. Thus, 11,464 EPIC-26 questionnaires were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Descriptive characteristics for the overall cohort are reported in Table 1. Median age (quartiles) at enrollment was 64 (58,69); 74% (1,884) of patients were white, and 45% (1,151) had D’Amico prostate cancer low-risk, 39% (988) intermediate-risk, and 16% (418) high-risk disease. 66% (1,693) had a PSA between 4-10 ng/mL.

Figure 1:

Diagram of the assembly of the analytic cohort in the Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation (CEASAR) Study (5-Year data)

Table 1:

Patients Demographics and Baseline Characteristics, CEASAR study, 2011-2012

| Patient Characteristics | Subjects (N=2563) |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis (Median, IQR) | 64 (58,69) |

| Race | |

| White | 74% (1884) |

| Black | 14% ( 359) |

| Hispanic | 7% ( 187) |

| Asian | 3% ( 80) |

| Other | 1% ( 37) |

| Education | |

| <High school | 10% (250) |

| High school graduate | 21% (500) |

| Some college | 22% (533) |

| College graduate | 23% (562) |

| Graduate or professional school | 24% (588) |

| Marital status | |

| Not married | 20% ( 474) |

| Married | 80% (1953) |

| TIBI Comorbidity score | |

| 0-2 | 28% ( 690) |

| 3-4 | 42% (1024) |

| >= 5 | 30% ( 731) |

| D’Amico prostate cancer risk | |

| Low risk | 45% (1151) |

| Intermediate risk | 39% ( 988) |

| High risk | 16% ( 418) |

| Prostate specific antigen, ng/mL | |

| [0,4] | 21% ( 529) |

| (4,10] | 66% (1693) |

| (10,20] | 10% ( 257) |

| (20,50] | 3% ( 84) |

| Clinical stage | |

| T1 | 76% (1943) |

| T2 | 24% ( 609) |

| Biopsy Gleason score | |

| 6 or less | 52% (1331) |

| 3 + 4 | 28% ( 707) |

| 4 + 3 | 10% ( 264) |

| 8,9,10 | 10% ( 253) |

| Any hormone therapy in the first year | |

| No | 86% (2157) |

| Yes | 14% ( 346) |

| Accrual site | |

| Louisiana | 28% (725) |

| Utah | 8% (206) |

| Atlanta | 12% (309) |

| Los Angeles County, CA | 29% (731) |

| New Jersey | 16% (411) |

| CaPSURE | 7% (181) |

Abbreviations: CaPSURE- Cancer of the Prostate Strategic Urologic Research Endeavor

Table 2 summarizes the patients’ responses to the best possible outcome for each question at baseline and at 6, 12, 36, and 60 months. Table 3 details the percentage of men at each domain score stratum who report the best possible outcome. As the domain scores improve, so does the percentage of men reporting the best possible outcome. These relationships are further depicted graphically in Figure 2. Each curve illustrates the relationship between the individual item and the domain score and demonstrates the distinct kinetics with different degrees of elasticity exhibited by every question. The most elastic areas are those at which a small change in domain score is associated with the greatest difference in the proportion of men reporting the best response to an individual item. None of these curves exhibit linear kinetics, and further detail into these most clinically relevant domain trends are below. In the sensitivity analysis, which estimated the likelihood of having the best two possible outcomes for each question, the results mirrored those of the primary analysis (Supplementary Figure 2).

Table 2:

Summary of patient’s choice to each of the EPIC-26 items collected at every survey from baseline through 5-years.

| Survey time |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPIC-26 Items% | Patient’s choice | Baseline | 6-month | 1-year | 3-year | 5-year | Combined |

| N=2563 | N=2446 | N=2377 | N=2143 | N=1935 | N=11464 | ||

|

| |||||||

| Urinary Incontinence | |||||||

| 1. Rarely or never leaks | Yes | 73% (1809) | 47% (1155) | 50% (1150) | 48% (1026) | 48% (918) | 54% (6058) |

| No | 27% (681) | 53% (1282) | 50% (1156) | 52% (1093) | 52% (993) | 46% (5205) | |

| 2. Total urinary control | Yes | 66% (1644) | 43% (1042) | 44% (1038) | 41% (867) | 40% (762) | 47% (5353) |

| No | 34% (851) | 57% (1393) | 56% (1314) | 59% (1254) | 60% (1154) | 53% (5966) | |

| 3. No pads | Yes | 92% (2297) | 71% (1733) | 77% (1808) | 78% (1668) | 76% (1464) | 79% (8970) |

| No | 8% (196) | 29% (702) | 23% (550) | 22% (463) | 24% (451) | 21% (2362) | |

| 4 a. No problem with dripping | Yes | 70% (1752) | 46% (1126) | 48% (1139) | 49% (1041) | 47% (904) | 53% (5962) |

| No | 30% (750) | 54% (1311) | 52% (1213) | 51% (1078) | 53% (1009) | 47% (5361) | |

|

| |||||||

| Urinary Irritative | |||||||

| 4 b. No pain or burning with urination | Yes | 83% (2062) | 89% (2152) | 89% (2091) | 92% (1952) | 93% (1772) | 89% (10029) |

| No | 17% (434) | 11% (278) | 11% (263) | 8% (175) | 7% (141) | 11% (1291) | |

| 4 c. No bleeding with urination | Yes | 93% (2303) | 98% (2354) | 98% (2287) | 97% (2047) | 98% (1853) | 97% (10844) |

| No | 7% (175) | 2% (57) | 2% (57) | 3% (59) | 2% (42) | 3% (390) | |

| 4 d. No weak stream or incomplete emptying | Yes | 46% (1163) | 60% (146) | 61% (1433) | 62% (1313) | 61% (1166) | 58% (6535) |

| No | 54% (1340) | 40% (978) | 39% (918) | 38% (816) | 39% (747) | 42% (4799) | |

| 4 e. No frequency of urination | Yes | 37% (930) | 39% (945) | 41% (966) | 45% (959) | 44% (849) | 41% (4649) |

| No | 63% (1572) | 61% (1487) | 59% (1398) | 55% (1181) | 56% (1072) | 59% (6691) | |

| 5. Overall, no problem with urinary function | Yes | 50% (1223) | 42% (1009) | 46% (1071) | 49% (1046) | 48% (917) | 47% (5266) |

| No | 50% (1242) | 58% (1414) | 54% (1247) | 51% (1083) | 52% (998) | 53% (5984) | |

|

| |||||||

| Bowel function | |||||||

| 6 a. No rectal urgency | Yes | 77% (1927) | 75% (1837) | 72% (1699) | 74% (1583) | 72% (1379) | 74% (8425) |

| No | 235 (580) | 25% (599) | 28% (664) | 26% (549) | 28% (536) | 26% (2928) | |

| 6 b. No bowel frequency | Yes | 82% (2047) | 80% (1943) | 80% (1894) | 83% (1755) | 81% (1555) | 81% (9194) |

| No | 18% (457) | 20% (487) | 20% (465) | 17% (368) | 19% (353) | 19% (2130) | |

| 6 c. No fecal incontinence | Yes | 93% (2332) | 91% (2207) | 90% (2124) | 90% (1901) | 89% (1706) | 91% (10270) |

| No | 7% (174) | 9% (220) | 10% (225) | 10% (218) | 11% (203) | 9% (1040) | |

| 6 d. No bloody stools | Yes | 95% (2389) | 96% (2330) | 95% (2245) | 94% (2005) | 96% (1834) | 95% (10803) |

| No | 5% (113) | 4% (101) | 5% (117) | 6% (125) | 4% (80) | 5% (536) | |

| 6 e. No pain with bowel movements | Yes | 84% (2097) | 88% (2135) | 87% (2050) | 89% (1903) | 89% (1711) | 87% (9896) |

| No | 16% (409) | 12% (296) | 13% (305) | 11% (228) | 11% (202) | 13% (1440) | |

| 7. No problems with bowel function | Yes | 79% (1964) | 75% (1832) | 75% (1754) | 75%(1597) | 76%(145) | 76% (8597) |

| No | 21% (527) | 25% (600) | 25% (594) | 25% (535) | 24% (465) | 24% (2721) | |

|

| |||||||

| Sexual function | |||||||

| 8 a. Very good erections | Yes | 24% (582) | 7% (175) | 8% (188) | 9% (192) | 9% (168) | 12% (1305) |

| No | 76% (1854) | 93% (2192) | 92% (2076) | 91% (1887) | 91% (1714) | 88% (9723) | |

| 8 b. Very good orgasm | Yes | 29% (709) | 13% (306) | 14% (330) | 16% (329) | 15% (289( | 18% (1963) |

| No | 71% (1733) | 87% (2052) | 86% (1966) | 84% (1741) | 85% (1579) | 82% (9071) | |

| 9. Erections firm enough for intercourse | Yes | 56% (1380) | 28% (669) | 32% (739) | 33% (689) | 32% (598( | 37% (4075) |

| No | 44% (1066) | 72% (1698( | 68% (1569) | 67% (1389) | 68% (1272) | 63% (6994) | |

| 10. Erections whenever desired | Yes | 40% (973) | 18% (419) | 20% (467) | 22% (457) | 23% (417) | 25% (2733) |

| No | 60% (1450) | 82% (1914) | 80% (1832) | 78% (1596) | 77% (1428) | 75% (8220) | |

| 11. Very good sexual function | Yes | 22% (541) | 8% (178) | 9% (206) | 10% (206) | 10% (185) | 12% (1316) |

| No | 78% (1885) | 92% (2153) | 91% (2082) | 90% (1857) | 90% (1678) | 88% (9655) | |

|

| |||||||

| Hormonal | |||||||

| 13 a. No hot flashes | Yes | 89% (2195) | 85% (2034) | 86% (2004) | 90% (1885) | 91% (1724) | 88% (9842) |

| No | 11% (273) | 15% (361) | 14% (332) | 10% (214) | 9% (169) | 12% (1349) | |

| 13 b. No breast tenderness | Yes | 96% (2335) | 97% (2275) | 94% (2160) | 95% (1969) | 96% (1797) | 96% (10536) |

| No | 4% (88) | 3% (81) | 6% (140) | 5% (105) | 4% (73) | 4% (487) | |

| 13 c. No problem with depression | Yes | 64% (1581) | 67% (1609) | 65% (1518) | 68% (1417) | 68% (1282) | 66% (7407) |

| No | 36% (881) | 33% (786) | 35% (800) | 32% (677) | 32% (609) | 34% (3753) | |

| 13 d. No problem with low energy | Yes | 50% (1247) | 52% (1236) | 46% (1085) | 52% (1089) | 51% (971) | 50% (5628) |

| No | 50% (1231) | 48% (1164) | 54% (1251) | 48% (1022) | 49% (924) | 50% (5592) | |

| 13 e. No change in body weight | Yes | 77% (1913) | 74% (1767) | 71% (1656) | 75% (1569) | 74% (1394) | 74% (8299) |

| No | 23% (563) | 26% (630) | 29% (685) | 25% (533) | 26% (502) | 26% 2913) | |

This is the number for each specific item.

Reformatted for better displaying.

Table 3:

Summary of patient’s choice to each of the EPIC-26 items at 5-year survey by corresponding domain score categories.

| Domain Score Category |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPIC-26 Items% | Patient’s choice | 0-20 | 21-40 | 41-60 | 61-80 | 81-100 | Combined |

| Urinary Incontinence | N=384 | N=781 | N=1251 | N=2466 | N=6263 | N=11145 | |

| 1. Rarely or never leaks | Yes | 0% (0) | 0% (1) | 1% (10) | 6% (160) | 93% (5833) | 54% (6004) |

| 2. Total urinary control | Yes | 0% (0) | 0% (1) | 1% (12) | 5% (114) | 82% (5162) | 47% (5289) |

| 3. No pads | Yes | 0% (0) | 9% (70) | 27% (333) | 89% (2207) | 99% (6213) | 79% (8823) |

| 4 a. No problem with dripping | Yes | 0% (0) | 1% (8) | 4% (45) | 14% ( 343) | 88% (5482) | 53% (5878) |

|

| |||||||

| Urinary Irritative | N=38 | N=112 | N=524 | N=1760 | N=8728 | N=11162 | |

| 4 b. No pain or burning with urination | Yes | 0% (0) | 2% (2) | 39% (206) | 74% (1310) | 96% (8382) | 89% (9900) |

| 4 c. No bleeding with urination | Yes | 0% (0) | 59% (66) | 84% (439) | 93% ( 1643) | 99% ( 8636) | 97% (10784) |

| 4 d. No weak stream or incomplete emptying | Yes | 0% (0) | 2% (2) | 2% (9) | 9% ( 160) | 72% (6296) | 58% (6467) |

| 4 e. No frequency of urination | Yes | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 1% (3) | 2% ( 39) | 52% (4557) | 41% (4599) |

| 5. Overall, no problem with urinary function | Yes | 5% (2) | 1% (1) | 2% (10) | 8% (138) | 58% (5043) | 47% (5266) |

|

| |||||||

| Bowel function | N=22 | N=88 | N=256 | N=940 | N=10031 | N=11337 | |

| 6 a. No rectal urgency | Yes | 0% ( 0) | 0% (0) | 2% (6) | 9% ( 88) | 83% (8313) | 74% (8407) |

| 6 b. No bowel frequency | Yes | 0% (0) | 1% (1) | 7% (18) | 20% (187) | 90% (8986) | 81% (9192) |

| 6 c. No fecal incontinence | Yes | 0% (0) | 7% ( 6) | 23% (57) | 56% (519) | 97% ( 9684) | 91% (10266) |

| 6 d. No bloody stools | Yes | 10% (2) | 51% (44) | 74% (188) | 84% (787) | 97% ( 9772) | 95% (10793) |

| 6 e. No pain with bowel movements | Yes | 0% (0) | 17% (15) | 39% (98) | 53% (497) | 93% (9277) | 87% (9887) |

| 7. No problems with bowel function | Yes | 10% (2) | 2% (2) | 2% (4) | 6% (54) | 85% (8515) | 76% (8577) |

|

| |||||||

| Sexual function | N=3678 | N=1643 | N=1462 | N=1871 | N=2321 | N=10975 | |

| 8 a. Very good erections | Yes | 0% (0) | 0% (6) | 1% (9) | 2% (43) | 54% (1236) | 12% (1294) |

| 8 b. Very good orgasm | Yes | 1% (42) | 4% (67) | 6% (92) | 14% (268) | 64% (1484) | 18% (1953) |

| 9. Erections firm enough for intercourse | Yes | 0% (2) | 3% (51) | 28% (405) | 72% (1339) | 97% (2257) | 37% (4054) |

| 10. Erections whenever desired | Yes | 0% (3) | 2% (26) | 6% (82) | 29% (533) | 90% (2079) | 25% (2723) |

| 11. Very good sexual function | Yes | 0% (3) | 0% (1) | 1% (11) | 2% (37) | 55% (1259) | 12% (1311) |

|

| |||||||

| Hormonal | N=31 | N=145 | N=635 | N=1914 | N=8430 | N=11155 | |

| 13 a. No hot flashes | Yes | 3% (1) | 20% (29) | 50% (318) | 73% (1406) | 96% (8057) | 88% (9811) |

| 13 b. No breast tenderness | Yes | 6% ( 2) | 57% (75) | 79% (489) | 91% (1703) | 99% ( 8258) | 96% (10527) |

| 13 c. No problem with depression | Yes | 0% (0) | 1% ( 1) | 8% (53) | 25% (483) | 81% (6825) | 66% (7362) |

| 13 d. No problem with low energy | Yes | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 1% (9) | 5% (105) | 65% (5480) | 50% (5594) |

| 13 e. No change in body weight | Yes | 0% (0) | 5% (7) | 18% (11) | 41% (786) | 87% (7348) | 74% (8252) |

Figure 2:

Association of EPIC-26 domain scores to dichotomized best possible outcomes for each question within that domain. The light blue histogram signifies the frequency of men (n) who reported each domain interval. Each line depicts the relationship between domain score and the percentage reporting the best possible outcome at that score along a continuum. A) urinary incontinence; B) urinary irritative*; C) bowel function; D) sexual function; E) hormonal function

* The urinary bother score question 5 was included in the urinary irritative domain for classification purposes but was not used to calculate the overall urinary irritative domain score

Urinary incontinence

In the urinary incontinence domain, the two items we considered most clinically relevant have distinct relationships with domain score. At a domain score between 41-60, 1% of patients reported rarely or never leaking and between 61-80, only 6% reported being dry. However, between scores of 81 and 100, 93% reported being dry (Table 3). This relationship was represented by a steep, narrow and right-shifted curve (Figure 2a, blue line). By contrast, the need for pad usage was most elastic between domain scores of 40 to 80 with 27% reporting no pad use at a score between 41-60 versus 89% at 61-80. Above a domain score of 80, pad use was rarely reported. This curve (Figure 2a, red line) was notably more left-shifted and broader based compared to the question pertaining to leakage.

Urinary bother

Question 5 on the EPIC-26 pertains to urinary bother. This curve is notably right shifted, and even at EPIC domain scores of 81-100, only 58% of men report having no problem with urination overall. This drops to 8% with EPIC domain scores of 61-80.

Sexual Function

We dichotomized the quality of erections category into firm enough for intercourse versus any lesser response. Between 41-60 on the sexual domain score, only 28% of patients reported an erection sufficient for intercourse. Meanwhile, when the sexual domain score was 61-80, 72% of patients reported an erection sufficient for intercourse versus 97% at 81-100. The greatest elasticity was between a sexual domain score of 40 and 80, which was further visualized Figure 2d. In contrast, when analyzing the overall sexual function item (EPIC-26 question 11), the curve was more right-shifted with a steep change in elasticity between scores of 81 to 100. Scores less than 80 are highly indicative of poor sexual function with only 55% reporting very good overall sexual function between 61-80 and 2% between 41-60.

Discussion:

As we continue to emphasize the need for shared decision making, it is essential that providers and patients alike have accurate information regarding outcomes.[21,22] While the main CEASAR study provided high-quality data regarding comparative harms of different treatments for localized prostate cancer based on EPIC-26 domain scores, the current study provides a means for interpretation of these domain scores for application into clinical practice.

Altogether, our study has many areas of clinical significance and is important for several reasons. First, these findings allow us to better counsel men with newly diagnosed, localized prostate cancer by detailing the realistic probabilities of being impotent or needing pads when undergoing treatment. The current study makes this information more clinically useful by allowing one to translate the domain scores into relevant functional outcomes that are easy to interpret. For example, our previous 3-year CEASAR data found an adjusted mean score difference of −16.2 points in sexual function score for RALP versus AS.[16] If a patient’s preoperative sexual function domain score was 100, we can say that if their score remains between 81-100, 97% of men in that range achieve an erection sufficient for intercourse versus only 72% at 61-80. Further predictive models are currently underway.

Second, this study demonstrates that the probability distributions for functional outcomes are non-linear as seen in Table 3 and demonstrated in Figure 2. Viewed through the lens of dichotomous functional outcomes (e.g., pads-yes/no or erections firm enough for intercourse-yes/no), one can see that the MCID has a varying effect on function depending on domain score. For example, a fall from 81-100 to 61-80 on the urinary irritative domain corresponds to a 52% versus 2% chance, respectively, of reporting no frequency of urination whereas a similar drop in sexual function corresponds to 97% versus 72% chance of obtaining an erection sufficient for intercourse. As a result, these data suggest that the MCID is dependent upon and varies along the continuum of starting domain scores rather than being fixed.[18]

Third, the EPIC-26 domain scores are psychometrically validated. This tool itself is invaluable for comparing the functional outcomes of different treatment options and studying the trajectory of functional outcomes over time. Nevertheless, a numerical domain score may be difficult for patients and providers alike to interpret.[18,23,24] Fortunately, this instrument comprises easily interpretable items that may better resonate with the patients’ “actual experiences” of side effects. For example, previous studies have attempted to define potency as a sexual function domain score greater than 60 and very potent as being greater than 80.[25] Nevertheless, at a sexual function domain score between 61 to 80, our data show that only 2% of patients reported “very good” erections and less than 1/3 (29%) reported being able to get erections whenever they wanted. We feel the ability to make this data more granular helps better define expectations after treatment.

Our study demonstrates that each of the individual items has a unique relationship, or kinetic, with the domain score. The domain score can thus be translated into a likelihood of retaining or regaining specific functional capabilities in a way that the patient and provider can understand. We understand that the individual items and domain score are highly associated, but the primary objective allowed for the individual items to have improved clinical interpretability which may be more meaningful to the patient than the generalized domain scores themselves. Furthermore, robust data suggest that PROs correlate with improved clinical care,[26,27] increased referrals,[28] and improved care processes.[29] Continuing to improve our understanding of PROs will hopefully only improve these stated benefits.[30]

Our study is not without limitations. First, our analyzed data do not take into account PROs from time points other than those studied and do not distinguish between treatments type. Nevertheless, given the large sample size, prolonged follow-up, and range of treatments provided, we strongly feel this encapsulates the majority of patients with localized disease. Furthermore, while treatment type affects domain score,[16] the scoring is the same regardless of treatment; a score of 60 on sexual function has the same meaning regardless of whether a patient underwent AS, EBRT, or a RALP. We also assumed the EPIC domain scores are the same regardless of time point. Second, dichotomization of the items at the highest level may not represent the entire spectrum of a patient’s expectation, and some patients may consider other cut points clinically meaningful. For example, erections sufficient for foreplay instead of intercourse may be highly relevant in some patients. Further analysis with additional cut points would be needed to discern this. That said, our sensitivity analysis incorporates the best two answers for each question and shows comparable results to our primary analysis, supporting our methodology. Third, these results have not been externally validated. Nevertheless, CEASAR’s longitudinal, population-based design, diverse cohort and focus on contemporary treatments provides a representative dataset for this type of analysis.[16]

Conclusion:

The EPIC-26 provides a validated means of comparing functional outcomes across treatments and over time. Nevertheless, the interpretation of domain scores can be challenging for both patients and providers. In this study, we sought to translate domain scores into the probability of obtaining pertinent outcomes, such as need for incontinence pads or obtaining erections sufficient for intercourse, highlighting that the percentage reporting best possible outcomes varies widely over narrow domain score differences. This information may be valuable when counseling men on treatment options.

Supplementary Material

EPIC-26 Short-Form Questionnaire

A sensitivity analysis assessing the association of EPIC-26 domain scores to the best two possible outcomes for each question within that domain. The light blue histogram signifies the frequency of men (n) who reported each domain interval. Each line depicts the relationship between domain score and the percentage reporting the best possible outcome at that score along a continuum. A) urinary incontinence; B) urinary irritative; C) bowel function; D) sexual function; E) hormonal function

Acknowledgements:

Financial support and sponsorship:

Dr. Laviana’s effort was supported by 5K12HS022990 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Funding for the study was provided by grants 1R01HS019356 and 1R01HS022640 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; UL1TR000011 to the Vanderbilt Institute of Clinical and Translational Research from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Research reported in this article was partially funded through a Patient- Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) award CE12-11-4667.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None

References:

- 1).Albertsen PC, Hanley JA, Fine J, et al. 20-year outcomes following conservative management of clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA. 2005; 293: 2095–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2).Fenton JJ, Weyrich MS, Durbin S, et al. Prostate-specific antigen-based screening for prostate cancer. Evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventative Services Task Force. JAME. 2018; 319(18): 1914–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Eifler JB, Alvarez J, Koyama T, et al. More judicious use of expectant management for localized prostate cancer during the last 2 decades. J Urol. 2017; 197(3): 614–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Weiner AB, Kundu SD. Prostate cancer: a contemporary approach to treatment and outcomes. Med Clin North Am. 2018; 102(2): 215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Wilt TJ, Jones KM, Barry MJ, et al. Follow-up of prostatectomy versus observation for early prostate cancer. NEJM. 2017; 377: 132–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6).Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. NEJM. 2016; 375: 1415–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Litwin MS, Gore JL, Kwan L, et al. Quality of life after surgery, external beam irradiation, or brachytherapy for early-stage prostate cancer. Cancer. 2007; 11(1): 2239–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Reeve BB, Wang M, Weinfurt K, et al. Psychometric evaluation of PROMIS sexual function and satisfaction measures in a longitudinal population-based cohort of men with localized prostate cancer. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2018. Available online 24 Oct 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Stanford JL, Feng Z, Hamilton AS, et al. Urinary and sexual function after radical prostatectomy for clinically localized prostate cancer: the Prostate Cancer Outcomes Study. JAMA. 2000; 283: 354–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Sanda MG, Dunn Rl, Michalski J, et al. Quality of life and satisfaction with outcome among prostate-cancer survivors. NEJM. 2008; 358: 1250–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Tyson MD, Koyama T, Lee D, et al. Effect of Prostate Cancer Severity on Functional Outcomes After Localized Treatment: Comparative Effectiveness Analysis of Surgery and Radiation Study Results. European Urology. 2018; 74(1): 26–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Chipman JJ, Sanda MG, Dunn RL, et al. Measuring and predicting prostate cancer related quality of life changes using the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite for Clinical Practice (EPIC-CP). J Urol. 2014; 191(3): 638–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Wei JT, Dunn RL, Litwin MS, et al. Development and validation of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) for comprehensive assessment of health-related quality of life in men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2000; 56:899–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Szymanski KM, Wei JT, Dunn RL, et al. Development and validation of an abbreviated version of the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite instrument for measuring health-related quality of life among prostate cancer survivors. Urology. 2010; 76(5):1245–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Chang P, Szymansi KM, Dunn RL, et al. Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite for Clinical Practice (EPIC-CP): Development and validation of a practical health-related quality of life instrument for use in routine clinical care of prostate cancer patients. J Urol. 2011;186(3): 865–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Barocas DA, Alvarez J, Resnick MJ. Association between radiation therapy, surgery, or observation for localized prostate cancer and patient-reported outcomes after 3 years. JAMA. 2017; 317(11); 1126–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Barocas DA, Chen V, Cooperberg M, et al. Using a population-based observational cohort study to address difficult comparative effectiveness research questions: the CEASAR study. J Comp Eff Res. 2013; 2(4): 445–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Skolarus TA, Dunn RL, Sanda MG, et al. Minimally important differences for the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite Short Form. Urology. 2015; 85:101–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Ellison JS, He C, Wood DP. Stratification of post-prostatectomy urinary function using Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite. Urology. 2013; 81(1):56–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).R Core Team (2019): A language and environment of statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: <https://www.R-project.org/> [Google Scholar]

- 21).Protopapa E, Meulen JVD, Moore C, et al. Patient-reported outcome (PRO) questionnaires for men who have radical surgery for prostate cancer: a conceptual review of existing instruments. BJU International. 2017; 129(4): 468–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Unger JM, Vaidya R, Gore JL, et al. Key design and analysis principles for quality for life and patient-reported outcomes in clinical trials. Urologic Oncology. 2019; 37(4):324–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Resncik MK, Barocas DA, Morgans AK, et al. The evolution of self-reported urinary and sexual dysfunction over the last two decades: implications for comparative effectiveness research. Eur Urol. 2015; 67(6): 1019–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Resnick MJ, Barocas DA, Morgans AK et al. Contemporary prevalence of pretreatment urinary, sexual, hormonal and bowel dysfunction. Defining the population at risk for harms of prostate cancer treatment. Cancer. 2014; 120(8): 1263–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Schroeck FR, Donatucci CF, Smathers EC, et al. Defining potency: a comparison of the International Index of Erectile Function short version and the Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite. Cancer. 2008; 113(10):2687–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Gerhardt W, Mara CA, Kudel I, et al. Systemwide implementation of patient-reported outcomes in routine clinical care at a Children’s Hospital. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2018l; 44(8): 441–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Detmar SB, Martin MJ, Schornagel JH, et al. Health-related quality-of-life assessment and patient-physician communication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002; 288(23): 3027–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Espallargues M, Valderas JM, and Alonso J. Provision of feedback on perceived health status to health care professionals: a systematic review of its impact. Med Care. 2000; 38: 175–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Geenhalgh J and Meadows K. The effectiveness of the use of patient-based measures of health in routine practice in improving the process and outcome of patient-care: a literature review. J Eval Clin Pract. 1999; 5: 401–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Knaup C, Koesters M, Schoefer D, et al. Effect of feedback of treatment outcome in specialist mental healthcare; meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2009; 195: 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

EPIC-26 Short-Form Questionnaire

A sensitivity analysis assessing the association of EPIC-26 domain scores to the best two possible outcomes for each question within that domain. The light blue histogram signifies the frequency of men (n) who reported each domain interval. Each line depicts the relationship between domain score and the percentage reporting the best possible outcome at that score along a continuum. A) urinary incontinence; B) urinary irritative; C) bowel function; D) sexual function; E) hormonal function