Abstract

Background/Aim: [6]-Gingerol, a compound extracted from ginger, has been studied for its therapeutic potential in various types of cancers. However, its effects on oral cancer remain largely unknown. Here, we aimed to investigate the potential anticancer activity and underlying mechanisms of [6]-gingerol in oral cancer cells. Materials and Methods: We analyzed the antigrowth effects of [6]-gingerol in oral cancer cell lines by cell proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion assays. We detected cell cycle and apoptosis with flow cytometry and further explored the mechanisms of action by immunoblotting. Results: [6]-Gingerol significantly inhibited oral cancer cell growth by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle G2/M phase arrest. [6]-Gingerol also inhibited oral cancer cell migration and invasion by up-regulating E-cadherin and down-regulating N-cadherin and vimentin. Moreover, [6]-gingerol induced the activation of AMPK and suppressed the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in YD10B and Ca9-22 cells. Conclusion: [6]-Gingerol exerts anticancer activity by activating AMPK and suppressing the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in oral cancer cells. Our findings highlight the potential of [6]-gingerol as a therapeutic drug for oral cancer treatment.

Keywords: [6]-Gingerol, AMPK, AKT, mTOR, oral cancer

Oral cancer, one of the many affecting the head and neck, is among the world’s ten most common cancers (1). The 5-year survival rate of oral cancer patients is still relatively low, less than 50% (2). Oral cancer treatments include surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and targeted therapy, depending on the diagnosis (3). The most commonly used chemotherapy drugs are 5-fluorouracil, carboplatin, cisplatin, paclitaxel, and irinotecan. However, drug resistance and side effects are serious problems that still hinder chemotherapy success. Hence, it is essential to develop more effective and safer drugs to treat oral cancers.

AMPK is a classical energy sensor activated by diverse conditions, including metabolic and oxidative stresses (4). The mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a highly conserved serine/threonine kinase in eukaryotes; it serves as a central regulator of cell metabolism, growth, proliferation, and survival (5). AMPK is a tumor suppressor, as it inhibits the activation of the oncogene mTORC1 (6). AMPK inhibits mTOR phosphorylation through the tumor suppressor complex (TSC) (7) and raptor (8). Multiple reports indicate that activating AMPK and inhibiting the mTOR pathway can repress the growth of a variety of cancer cells, including colon (9), gastric (10), cervical (11), and oral cancers (12). These observations indicate that the AMPK/mTOR pathway plays a critical role in the progression of various tumors.

Numerous anticancer agents such as metformin (13), resveratrol (14), and cordycepin (15) can activate AMPK. [6]-Gingerol is a major phenolic compound present in the ginger (Zingiber officinale) root which has been used as a spice and ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine for centuries. [6]-Gingerol has numerous pharmacological activities, including anti-inflammatory (16), neuroprotective (17), and anticancer properties (18-20). [6]-Gingerol enhances cisplatin sensitivity of gastric cancer cells by inhibiting cell proliferation, migration, and invasion via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (18). Treatments with [6]-gingerol induce gastric adenocarcinoma cell apoptosis by increasing the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and altering the Bax/Bcl-2 protein level (21). A recent study reported that [6]-gingerol inhibited oral cancer cells growth by triggering apoptosis and cell cycle arrest (19). The effect and the underlying mechanisms of [6]-gingerol in oral cancer cell growth remain largely unknown.

Here, we investigated the anticancer effects of [6]-gingerol on proliferation, migration, invasion, apoptosis, and cell cycle distribution in oral cancer cells. Additionally, we investigated the underlying molecular mechanisms of these effects. We found that [6]-gingerol significantly inhibits oral cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. It also induces cell cycle arrest at the G2/M phase and apoptosis. Furthermore, [6]-gingerol treatments activate AMPK and suppress the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in oral cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and cell culture. [6]-Gingerol was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Ca9-22 cells were purchased from the Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (Shinjuku, Japan). YD10B cells were obtained from the Oral Cancer Institute at the College of Dentistry, Yonsei University (Seoul, Korea) (22). The cells were incubated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco™) and 1% antibiotics. Cells were maintained at 37˚C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Cell viability assay. Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8 CCK-8; Dojindo Laboratories, Kumamoto, Japan) assays were performed to assess cell viability. Briefly, oral cancer cells were plated on 96-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells/well. After 24 h of culture, the medium was replaced with one containing the specified [6]-gingerol concentrations. The cells were then cultured for 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h, followed by an incubation with 10 μl of the CCK-8 regent per well for an additional 1 h at 37˚C. The optical density at 450 nm of each well was measured using a microplate reader (BioTek).

Soft agar colony formation assay. YD10B and Ca9-22 cells (8×103 cells/well) were suspended in complete growth medium containing 0.3% agar with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol, and then overlaid into 6-well plates containing 0.6% agar and the same [6]-gingerol concentrations. The cultures were incubated for 14 days with 5% CO2 at 37˚C. Subsequently, they were photographed under a microscope (Leica) and the number of colonies was counted on photographs using ImageJ.

Cell cycle and apoptosis analysis. Oral cancer cells were seeded into 60-mm culture dishes (1×105 cells/dish) and cultured overnight at 37˚C. Cells were then treated with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol for 48 h. For the cell cycle analysis, cells were collected and washed with cold PBS and then fixed in 70% ethanol at –20˚C overnight. Cells were incubated with propidium iodide (PI, 20 μg/ml) and RNase (100 μg/ml) in the dark for 30 min and detected by flow cytometry. For the apoptosis analysis, cells were stained with Annexin V-FITC and PI in the dark for 20 min and subsequently analyzed by FACS Verse flow cytometry (BD Science, CA, USA).

Migration and invasion assays. Migration assays were performed in 24-well transwell plates (8 μm pore size, Corning) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were seeded in the upper chambers at a density of 5×104 cells in 200 μl serum-free DMED with the indicated concentrations of [6]-gingerol. The lower chambers were filled with 600 μl of culture medium containing 20% FBS to stimulate cell traveling. After 48 h in culture at 37˚C with 5% CO2, cells were fixed for 20 min using 4% paraformaldehyde. The non-invaded cells were wiped using a cotton swab, and the invaded cells were stained with 0.05% crystal violet. For invasion assays, the chamber was pre-coated with Matrigel® (BD Biosciences, St Louis, MO, USA). The other procedures were the same as for the migration assays. The stained cells were quantified under a microscope to determine the number of invaded cells.

Western blotting assay. Oral cancer cells (1×106) were plated in 10-cm dishes and incubated with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol for 48 h at 37˚C. The cells were collected and lysed using the Pro-Prep lysis buffer (Intron Biotechnology, Gyeonggi-do, Republic of Korea). Protein concentrations were measured with a Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo). A total of 30 μg of protein was separated by SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (0.22 μm, Merck Millipore). The membranes were blocked in 5% BSA for 1 h and then incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies overnight at 4˚C, followed by incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. The primary antibodies cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, p53, Bax, cyclin A1, CDK2, cyclin B1, E-cadherin, N-cadherin, vimentin, p-AMPKα (Thr172), AMPKα, p-AKT(Ser473), AKT, p-mTOR (Ser2448), mTOR, p-p70S6K(Thr389), and p70S6K were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA). β-Actin was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Protein signals were detected with the ECL detection kit (GE Healthcare, Seoul, Korea) using the Davinch imaging system (Davinch-K, Seoul, Republic of Korea). β-actin was used as a loading control.

Statistical analysis. Results are presented as mean±SD from three independent experiments. Statistical significance was determined using the Student’s t-test. A p-value less than 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.

Results

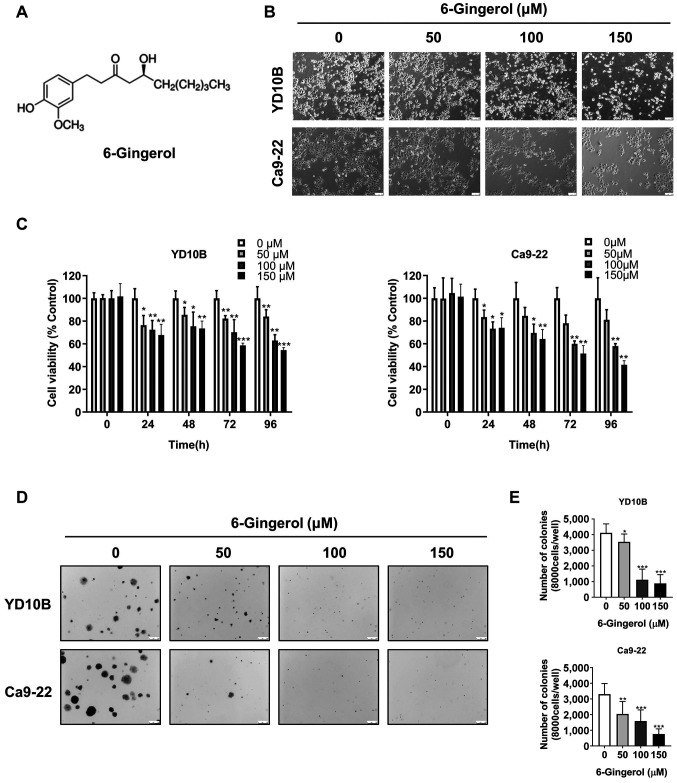

[6]-Gingerol has antiproliferative effects in oral cancer cells. The chemical structure of [6]-gingerol is shown in Figure 1A. To evaluate the effects of [6]-gingerol on human oral cancer cell growth, YD10B and Ca9-22 cells were exposed to different concentrations (0, 50, 100, or 150 μM) of [6]-gingerol for 48 h. Treatments changed cell morphology to round, caused shrinkage, and reduced cell density (Figure 1B). This indicated that [6]-gingerol could induce oral cancer cell death. Next, we performed CCK-8 assays to evaluate the viability of treated oral cancer cells at different time points. As shown in Figure 1C, [6]-gingerol inhibited oral cancer cell proliferation in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Soft agar colony formation assays showed that the number and size of clones were markedly reduced by [6]-gingerol in a dose-dependent manner in YD10B and Ca9-22 cells (Figure 1D, E). These results show that [6]-gingerol effectively inhibits oral cancer cell proliferation and colony formation.

Figure 1. [6]-Gingerol has antiproliferative effects in oral cancer cells. (A) Chemical structure of [6]-gingerol. (B) Cell morphology of YD10B and Ca9-22 cells after treatment with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol for 48 h, as observed with a light microscope (magnification, 100×). (C) Cell viability analyzed with the CCK-8 assay. YD10B and Ca9-22 cells were treated with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol for 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h. (D) Representative images of the soft agar assay in YD10B and Ca9-22 cells after treatment with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol (magnification, 50×). (E) Relative colony number and size of YD10B and Ca9-22 cells after treatment with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol. Data are presented as the mean±SD (n=6). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

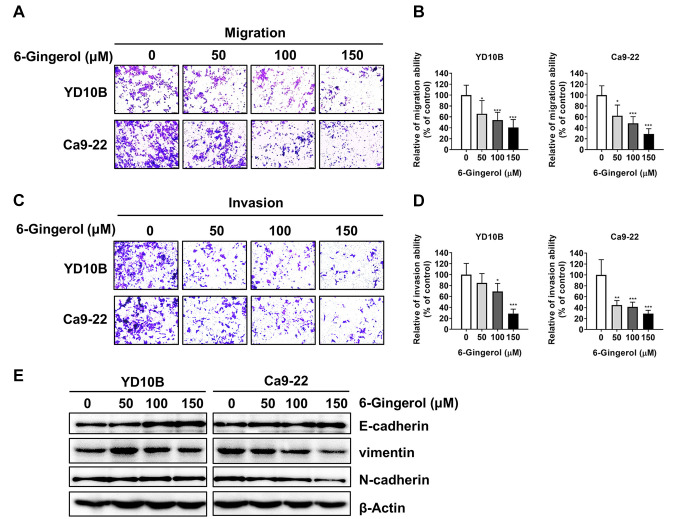

[6]-Gingerol inhibits the migration and invasion abilities of oral cancer cells. We then investigated whether [6]-gingerol could attenuate oral cancer cell migration and invasion abilities. Both migration and invasion of oral cancer cells were significantly inhibited by [6]-gingerol in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2A-D). The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) process can make solid tumors more malignant and increase their invasiveness and metastatic activity (23,24). Therefore, we investigated the effect of [6]-gingerol on the expression of the EMT marker proteins E-cadherin, N-cadherin, and vimentin. Immunoblotting results revealed that [6]-gingerol down-regulated N-cadherin and vimentin and up-regulated E-cadherin in YD10B and Ca9-22 cells (Figure 2E). These results suggest that [6]-gingerol inhibits the migration and invasion abilities of oral cancer cells by suppressing the EMT process.

Figure 2. [6]-Gingerol inhibits the migration and invasion of oral cancer cells. (A and B) Migration abilities of YD10B and Ca9-22 cells were determined after treatment with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol for 48 h. (C) and (D) Invasion abilities of YD10B and Ca9-22 cells were determined after treatment with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol for 48 h. (E) Western blot analysis on the expression of vimentin, N-cadherin, and E-cadherin in the YD10B and Ca9-22 cells after treatment with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM [6]-gingerol for 48 h. Magnification, 100×. Data are presented as the mean±SD (n=6). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

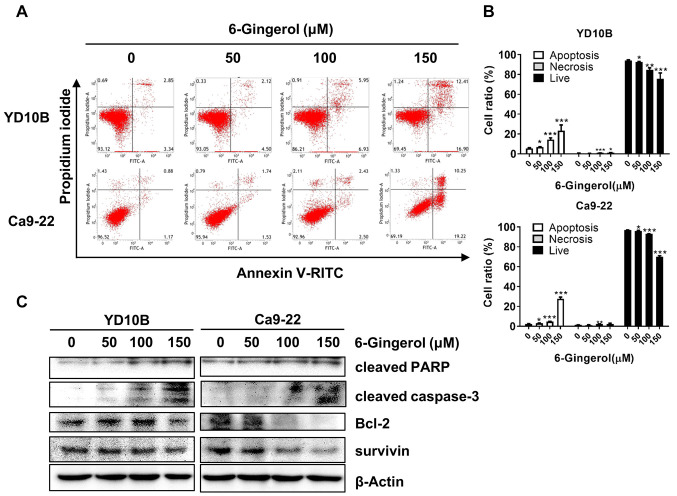

[6]-Gingerol induces apoptosis of oral cancer cells. Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in physiological and pathological conditions; the loss of apoptotic control is the key to cancer development (25). Hence, many cancer treatment strategies involve targeting different steps of apoptotic pathways (26). To investigate the effects of [6]-gingerol on apoptosis, oral cancer cells were treated with 0, 50, 100, or 150 μM of [6]-gingerol for 48 h, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The results showed that [6]-gingerol induced oral cancer cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A and B). Furthermore, we examined the expression of apoptotic-related proteins by western blotting assays. As shown in Figure 3C, [6]-Gingerol up-regulated the expression of cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, and Bax and down-regulated the expression of Bcl-2 and survivin in oral cancer cells.

Figure 3. [6]-Gingerol induces apoptosis of oral cancer cells. (A and B) Effects of [6]-gingerol on YD10B and Ca9-22 cell apoptosis as determined by flow cytometry. (C) Effects of [6]-gingerol on the expression of cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-3, Bcl-2, and survivin. Data are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

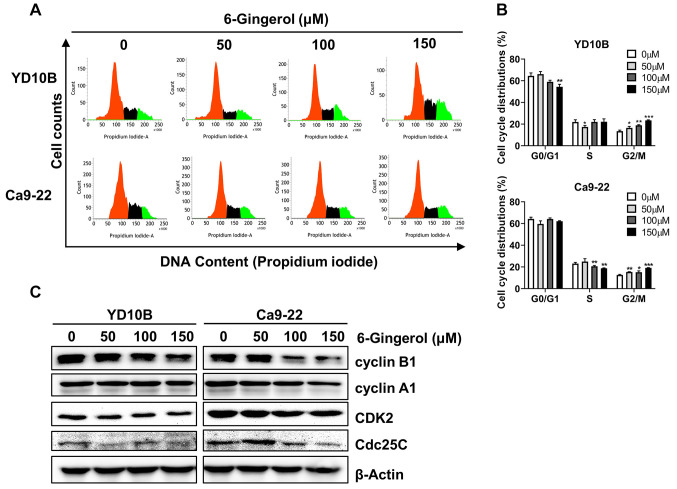

[6]-Gingerol induces cell cycle G2/M phase arrest of oral cancer cells. One strategy behind many cancer chemotherapy treatments is to induce cancer cell cycle arrest and then inhibit cell growth. To elucidate the mechanism responsible for growth inhibition by [6]-gingerol, we examined cell cycle distribution by flow cytometry following treatments with different concentrations (0, 50, 100, or 150 μM). [6]-Gingerol significantly increased the proportion of YD10B and Ca9-22 cells in the G2/M phase (Figure 4A and B). We then examined the expression of the G2/M phase associated proteins cyclin B1, cyclin A1, CDK2, and Cdc25C expression after treatment with [6]-gingerol. As shown in Figure 4C, [6]-gingerol down-regulated cyclin B1, cyclin A1, CDK2, and Cdc25C in YD10B and Ca9-22 cells.

Figure 4. [6]-Gingerol induces cell cycle G2/M phase arrest of oral cancer cells. (A) Effects of [6]-gingerol on cell cycle distribution quantified by flow cytometry. (B) Bar graphs represent values of cells in different phases. (C) Protein expression of cyclin B1, cyclin A1, CDK2, and Cdc25C analyzed by western blotting. Data are presented as the mean±SD (n=3). *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

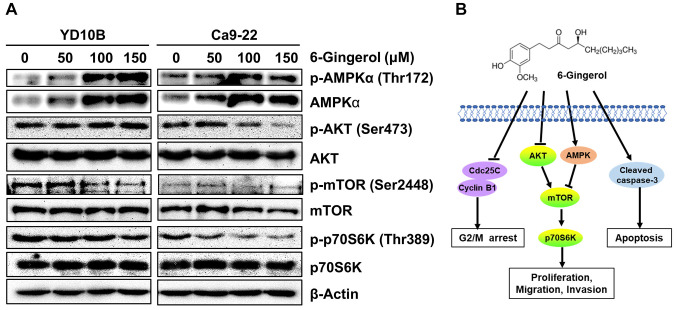

[6]-Gingerol activates AMPK and inhibits the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in oral cancer cells. One of the strategies for cancer chemotherapy drug development is to activate AMPK and inhibit the AKT/mTOR pathway (27,28). Interestingly, [6]-gingerol enhances cisplatin sensitivity of gastric cancer cells via the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway (18). We determined whether [6]-gingerol had an effect on the AMPK/AKT signaling pathway. As demonstrated in Figure 5A, [6]-gingerol treatments up-regulated p-AMPKα and AMPKα and significantly down-regulated p-AKT, p-mTOR, and p-70S6K expression in YD10B and Ca9-22 cells. The potential mechanism of [6]-gingerol in oral cancer cell growth is depicted in Figure 5B. These results suggest that [6]-gingerol inhibits oral cancer cell growth through activation of AMPK and suppression of the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway.

Figure 5. [6]-Gingerol activates AMPK and suppresses the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in oral cancer cells. (A) Protein expression of p-AMPK, AMPK, p-AKT, AKT, p-mTOR, mTOR, p-p70S6K, and p70S6K as determined by western blotting. (B) Potential mechanism of [6]-gingerol inhibition of oral cancer cell growth.

Discussion

Natural products play an important role in the development of drugs aimed at the clinical treatment of cancer. Numerous studies demonstrated that [6]-gingerol has a powerful therapeutic effect by inhibiting cancer-related signaling pathways in various types of cancer cells (18,21,29-31). For example, 6-gingerol suppresses tumorigenesis in benzo[a]pyrene and dextran sulfate sodium-induced colorectal cancer in mice by inhibiting inflammation and proliferation and inducing apoptosis (29). Another study reported that [6]-gingerol inhibits metastasis of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells through down-regulation of MMP-2 and MMP-9 (32). [6]-Gingerol also induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in human oral cancer cells (19). However, the anticancer effect and underlying molecular mechanism of [6]-gingerol in oral cancer cells remained largely unknown. Here, we demonstrated that [6]-gingerol significantly inhibited oral cancer cell proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion. Furthermore, we showed that it induced apoptosis and cell cycle G2/M phase arrest. Analyzes of the mechanism of [6]-gingerol action showed that treatments increased the expression of apoptotic proteins, inhibited the expression of cell cycle G2/M phase-related proteins, and regulated the level of EMT-related proteins. Additionally, we showed that [6]-gingerol inhibited oral cancer cell growth by activating AMPK and suppressing the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway.

AMPK acts as a metabolic tumor suppressor by regulating energy levels, performing metabolic checkpoints, and inhibiting cell growth (33,34). mTOR is a nutrient and growth factor sensing complex, and contributes to cell growth, biosynthesis, and autophagy (35). There is evidence that AMPK inhibits the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) through the phosphorylation of the tuberous sclerosis complex protein-2 (TSC2) and raptor (36). Furthermore, the AMPK/mTOR pathway plays a crucial role in the progression of various tumors (9,11,37). For example, trifolirhizin induces colorectal cancer cell autophagy and apoptosis through activating AMPK and suppressing the mTOR pathway in vivo and in vitro (9). Periplocin inhibits human pancreatic cancer cell proliferation and induces apoptosis by activating AMPK and suppressing the mTOR pathway (38). Our study demonstrated that [6]-gingerol significantly up-regulated p-AMPKα and down-regulated p-AKT, p-mTOR, and p-p70S6K expression in oral cancer cells. This indicates that [6]-gingerol inhibits oral cancer cell growth by activating AMPK and inhibiting the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway.

Apoptosis is the natural mechanism of programmed cell death; it is a particularly critical process in long-lived mammals (39). Apoptosis is also one of the mechanisms of cancer prevention (40). We found that [6]-gingerol increased expression of cleaved caspase-3, cleaved PARP, and decreased the expression of Bcl-2 and survivin in oral cancer cells, indicating that [6]-gingerol induced oral cancer cell apoptosis via the mitochondria-dependent pathway. Cell cycle deregulation is one of the characteristics of cancer cells. CDK/Cyclins have crucial roles in the regulation of cell cycle progression (41). Cyclin B1 is a regulatory protein involved in mitosis, playing an important role in the G2 to M phase transition. Over-expression of cyclin B1 causes the uncontrolled growth of cancer cells by binding to its partner Cdks (42). Cyclin A/CDK2 also regulates the G2/M phase transition, as it controls mitosis entry-time through activation of cyclin B/CDK1 (43,44). Cell division cycle 25C (Cdc25c) is a dual-specific phosphatase that activates the cyclin B1/CDK1 complex promoting G2/M progression (45). We found that [6]-gingerol inhibits oral cancer cell growth by inducing G2/M phase cell cycle arrest through down-regulating cyclin B1, cyclin A1, CDK2, and Cdc25C.

EMT is one of the major factors contributing to the metastasis of cancer cells and drug resistance (46). EMT is characterized by the activation of vimentin, N-cadherin, snai1, slug, and fibronectin and the down-regulation of the epithelial markers E-cadherin and desmoplakin (23). In this study, we explored the effect of [6]-gingerol on the oral cancer cell migration and invasion ability. We found that [6]-gingerol significantly inhibited the migration and invasion ability of oral cancer cells. Moreover, [6]-gingerol down-regulated vimentin and N-cadherin and up-regulated E-cadherin. These results indicate that [6]-gingerol suppresses EMT process in oral cancer cells, which may play a role in cancer progression prevention.

Taken together, our results suggest that [6]-gingerol significantly inhibits oral cancer cell proliferation, migration, and invasion and induces apoptosis and cell cycle G2/M phase arrest. [6]-Gingerol inhibits oral cancer cell growth by inducing the activation of AMPK and suppressing the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. These findings highlight the potential of [6]-gingerol as a therapeutic agent for the treatment of oral cancer.

Conflicts of Interest

The Authors declare that they have no competing interests in relation to this study.

Authors’ Contributions

HBZ performed experiments and wrote the manuscript. EYK, JKY, HH, HK performed molecular experiments. SJP, SGL, SYK, SYJ, KK analyzed data. EKK, YKL designed experiments and analyzed data. MYK and ZYR supervised the experiments and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2020R1A4A1018280).

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, Mathers C, Parkin DM, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Bray F. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer. 2019;144(8):1941–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Migueláñez-Medrán BC, Pozo-Kreilinger JJ, Cebrián-Carretero JL, Martínez-García MA, López-Sánchez AF. Oral squamous cell carcinoma of tongue: Histological risk assessment. A pilot study. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2019;24(5):e603–e609. doi: 10.4317/medoral.23011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marur S, Forastiere AA. Head and neck cancer: changing epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(4):489–501. doi: 10.4065/83.4.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13(4):251–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. TOR signaling in growth and metabolism. Cell. 2006;124(3):471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shackelford DB, Shaw RJ. The LKB1-AMPK pathway: metabolism and growth control in tumour suppression. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(8):563–575. doi: 10.1038/nrc2676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuan Y, Xue X, Guo RB, Sun XL, Hu G. Resveratrol enhances the antitumor effects of temozolomide in glioblastoma via ROS-dependent AMPK-TSC-mTOR signaling pathway. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(7):536–546. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00319.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, Turk BE, Shaw RJ. AMPK phosphorylation of raptor mediates a metabolic checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008;30(2):214–226. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sun D, Tao W, Zhang F, Shen W, Tan J, Li L, Meng Q, Chen Y, Yang Y, Cheng H. Trifolirhizin induces autophagy-dependent apoptosis in colon cancer via AMPK/mTOR signaling. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):174. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-00281-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luan M, Shi SS, Shi DB, Liu HT, Ma RR, Xu XQ, Sun YJ, Gao P. TIPRL, a novel tumor suppressor, suppresses cell migration, and invasion through regulating AMPK/mTOR signaling pathway in gastric cancer. Front Oncol. 2020;10:1062. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2020.01062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang Y, Wang Q, Song D, Zen R, Zhang L, Wang Y, Yang H, Zhang D, Jia J, Zhang J, Wang J. Lysosomal dysfunction and autophagy blockade contribute to autophagy-related cancer suppressing peptide-induced cytotoxic death of cervical cancer cells through the AMPK/mTOR pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):197. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01701-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang CH, Lee CY, Lu CC, Tsai FJ, Hsu YM, Tsao JW, Juan YN, Chiu HY, Yang JS, Wang CC. Resveratrol-induced autophagy and apoptosis in cisplatin-resistant human oral cancer CAR cells: A key role of AMPK and Akt/mTOR signaling. Int J Oncol. 2017;50(3):873–882. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2017.3866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sośnicki S, Kapral M, Węglarz L. Molecular targets of metformin antitumor action. Pharmacol Rep. 2016;68(5):918–925. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2016.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Puissant A, Robert G, Fenouille N, Luciano F, Cassuto JP, Raynaud S, Auberger P. Resveratrol promotes autophagic cell death in chronic myelogenous leukemia cells via JNK-mediated p62/SQSTM1 expression and AMPK activation. Cancer Res. 2010;70(3):1042–1052. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao Y, Chen DL, Zhou M, Zheng ZS, He MF, Huang S, Liao XZ, Zhang JX. Cordycepin enhances the chemosensitivity of esophageal cancer cells to cisplatin by inducing the activation of AMPK and suppressing the AKT signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(10):866. doi: 10.1038/s41419-020-03079-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zahoor A, Yang C, Yang Y, Guo Y, Zhang T, Jiang K, Guo S, Deng G. 6-Gingerol exerts anti-inflammatory effects and protective properties on LTA-induced mastitis. Phytomedicine. 2020;76:153248. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2020.153248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee C, Park GH, Kim CY, Jang JH. [6]-Gingerol attenuates β-amyloid-induced oxidative cell death via fortifying cellular antioxidant defense system. Food Chem Toxicol. 2011;49(6):1261–1269. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo Y, Zha L, Luo L, Chen X, Zhang Q, Gao C, Zhuang X, Yuan S, Qiao T. [6]-Gingerol enhances the cisplatin sensitivity of gastric cancer cells through inhibition of proliferation and invasion via PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Phytother Res. 2019;33(5):1353–1362. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kapoor V, Aggarwal S, Das SN. 6-gingerol mediates its anti tumor activities in human oral and cervical cancer cell lines through apoptosis and cell cycle arrest. Phytother Res. 2016;30(4):588–595. doi: 10.1002/ptr.5561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeong CH, Bode AM, Pugliese A, Cho YY, Kim HG, Shim JH, Jeon YJ, Li H, Jiang H, Dong Z. [6]-Gingerol suppresses colon cancer growth by targeting leukotriene A4 hydrolase. Cancer Res. 2009;69(13):5584–5591. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mansingh DP, O J S, Sali VK, Vasanthi HR. [6]-Gingerol-induced cell cycle arrest, reactive oxygen species generation, and disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential are associated with apoptosis in human gastric cancer (AGS) cells. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2018;32(10):e22206. doi: 10.1002/jbt.22206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee EJ, Kim J, Lee SA, Kim EJ, Chun YC, Ryu MH, Yook JI. Characterization of newly established oral cancer cell lines derived from six squamous cell carcinoma and two mucoepidermoid carcinoma cells. Exp Mol Med. 2005;37(5):379–390. doi: 10.1038/emm.2005.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ribatti D, Tamma R, Annese T. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in cancer: A historical overview. Transl Oncol. 2020;13(6):100773. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramesh V, Brabletz T, Ceppi P. Targeting EMT in cancer with repurposed metabolic inhibitors. Trends Cancer. 2020;6(11):942–950. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2020.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wong RS. Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:87. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-30-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pfeffer CM, Singh ATK. Apoptosis: A target for anticancer therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(2):448. doi: 10.3390/ijms19020448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Han F, Li CF, Cai Z, Zhang X, Jin G, Zhang WN, Xu C, Wang CY, Morrow J, Zhang S, Xu D, Wang G, Lin HK. The critical role of AMPK in driving Akt activation under stress, tumorigenesis and drug resistance. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):4728. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07188-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang H, Gao Y, Fan X, Liu X, Peng L, Ci X. Oridonin sensitizes cisplatin-induced apoptosis via AMPK/Akt/mTOR-dependent autophagosome accumulation in A549 cells. Front Oncol. 2019;9:769. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farombi EO, Ajayi BO, Adedara IA. 6-Gingerol delays tumorigenesis in benzo[a]pyrene and dextran sulphate sodium-induced colorectal cancer in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2020;142:111483. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo Y, Chen X, Luo L, Zhang Q, Gao C, Zhuang X, Yuan S, Qiao T. [6]-Gingerol enhances the radiosensitivity of gastric cancer via G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis induction. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(5):2252–2260. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lv L, Chen H, Soroka D, Chen X, Leung T, Sang S. 6-gingerdiols as the major metabolites of 6-gingerol in cancer cells and in mice and their cytotoxic effects on human cancer cells. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(45):11372–11377. doi: 10.1021/jf303879b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee HS, Seo EY, Kang NE, Kim WK. [6]-Gingerol inhibits metastasis of MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19(5):313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo Z, Zang M, Guo W. AMPK as a metabolic tumor suppressor: control of metabolism and cell growth. Future Oncol. 2010;6(3):457–470. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li W, Saud SM, Young MR, Chen G, Hua B. Targeting AMPK for cancer prevention and treatment. Oncotarget. 2015;6(10):7365–7378. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albert V, Hall MN. mTOR signaling in cellular and organismal energetics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2015;33:55–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shaw RJ. LKB1 and AMP-activated protein kinase control of mTOR signalling and growth. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009;196(1):65–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou J, Zhu J, Yu SJ, Ma HL, Chen J, Ding XF, Chen G, Liang Y, Zhang Q. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibition reduces glucose uptake to induce breast cancer cell growth arrest through AMPK/mTOR pathway. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;132:110821. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xie G, Sun L, Li Y, Chen B, Wang C. Periplocin inhibits the growth of pancreatic cancer by inducing apoptosis via AMPK-mTOR signaling. Cancer Med. 2021;10(1):325–336. doi: 10.1002/cam4.3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Danial NN, Korsmeyer SJ. Cell death: critical control points. Cell. 2004;116(2):205–219. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00046-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopez J, Tait SW. Mitochondrial apoptosis: killing cancer using the enemy within. Br J Cancer. 2015;112(6):957–962. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peyressatre M, Prével C, Pellerano M, Morris MC. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases in human cancers: from small molecules to Peptide inhibitors. Cancers (Basel) 2015;7(1):179–237. doi: 10.3390/cancers7010179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soria JC, Jang SJ, Khuri FR, Hassan K, Liu D, Hong WK, Mao L. Overexpression of cyclin B1 in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and its clinical implication. Cancer Res. 2000;60(15):4000–4004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Boer L, Oakes V, Beamish H, Giles N, Stevens F, Somodevilla-Torres M, Desouza C, Gabrielli B. Cyclin A/cdk2 coordinates centrosomal and nuclear mitotic events. Oncogene. 2008;27(31):4261–4268. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oakes V, Wang W, Harrington B, Lee WJ, Beamish H, Chia KM, Pinder A, Goto H, Inagaki M, Pavey S, Gabrielli B. Cyclin A/Cdk2 regulates Cdh1 and claspin during late S/G2 phase of the cell cycle. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(20):3302–3311. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.949111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu K, Zheng M, Lu R, Du J, Zhao Q, Li Z, Li Y, Zhang S. The role of CDC25C in cell cycle regulation and clinical cancer therapy: a systematic review. Cancer Cell Int. 2020;20:213. doi: 10.1186/s12935-020-01304-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chaffer CL, San Juan BP, Lim E, Weinberg RA. EMT, cell plasticity and metastasis. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35(4):645–654. doi: 10.1007/s10555-016-9648-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]