Abstract

This study aimed to analyze the diagnosis and treatment process of patients with hematogenous disseminated pulmonary tuberculosis after treatment with in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET). We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data, including imaging and etiological data, the use of antimicrobials, metagenomic next-generation sequencing (mNGS) results, and the treatment process, of a patient who underwent IVF-ET due to an obstruction in the fallopian tube; after the treatment, she developed a persistent fever with shortness of breath and suffered a spontaneous abortion. Due to the failure of other treatment modalities, fiber optic bronchoscopy was performed, and the alveolar lavage fluid was obtained for mNGS. Tests for Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance (Xpert MTB/RIF) showed positive and negative results, respectively. Subsequently, anti-tuberculosis treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol was administered. After the patient’s condition improved, she was transferred to a specialized tuberculosis hospital for further treatment, where she died one month later from multiple organ failure. From this case, we conclude that clinicians should remain highly vigilant for pulmonary infection with M. tuberculosis in pregnant women, particularly in patients treated with IVF-ET, and check for its presence as soon as possible.

Keywords: tuberculosis, IVF-ET, maternal, mNGS

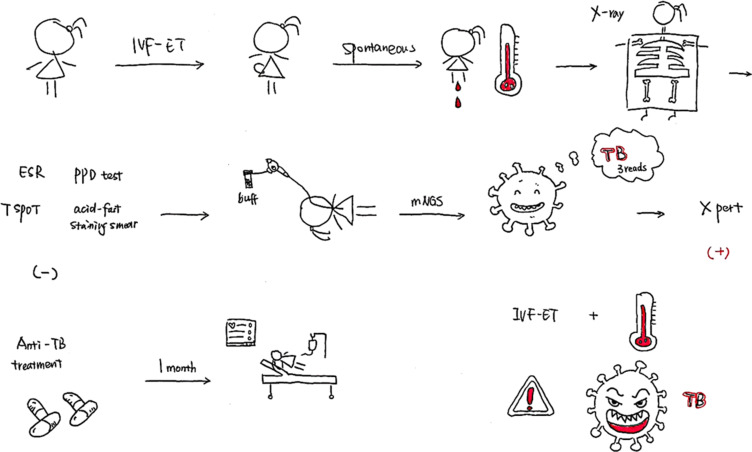

Video Abstract

Point your SmartPhone at the code above. If you have a QR code reader the video abstract will appear. Or use:

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is a global infectious disease that seriously endangers human health and is one of the top ten causes of death worldwide.1 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 10 million new TB cases occurred worldwide in 2019. The levels of estrogen and progesterone increase in pregnant women. This inhibits T lymphocytes and leads to an increased incidence of TB infection. In patients with in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET), the peak serum estrogen levels are several times higher than those in normal individuals. This is conducive to the reproduction of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and may be one of the factors that aggravate disease progression.2,3

The exact scale of TB during pregnancy remains uncertain globally, and a large number of active TB cases in pregnant women are likely to remain undetected.4 As patients with TB do not show obvious symptoms during pregnancy, and radiographic imaging examination is limited due to the patient’s condition, the proportion of patients that have TB during pregnancy and are not diagnosed and treated timely may be as high as 40%.5–7 These patients are not diagnosed until the disease has advanced to a severe stage. Pregnancy and childbirth are the two primary causes of severe TB in women; it has been reported early in 2015 that the pregnant women who died from TB were all in the advanced stage of the disease.8,9

Therefore, the early diagnosis of TB is particularly important in pregnant women, especially those receiving IVF-ET treatment. However, currently, there are some challenges in the clinical diagnosis of TB after IVF-ET,9 because of a lack of relevant literature. Here, we report a case of blood-type disseminated pulmonary TB after IVF-ET and analyze the diagnosis and treatment process to provide a reference for improving the early diagnosis and treatment success rate of pulmonary TB in pregnant women.

Case Report

The patient was a 28-year-old Asian female farmer. Due to fever and shortness of breath after spontaneous abortion (one week earlier), which aggravated over the next two days, she was admitted to the Department of Critical Care Medicine, the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, Xi’ an, Shaanxi, China on October 17, 2019.

The patient had received IVF-ET treatment due to an obstruction in the fallopian tube, and the pregnancy was successfully established on July 12, 2019. However, vaginal bleeding began on October 8, 2019. On October 10, 2019, she had a spontaneous abortion on the way to the hospital and underwent uterine clearance at the Northwest Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Xi’ an, Shaanxi, China. During treatment, the patient started feeling cold and developed shortness of breath, fever, and chills. Her body temperature was 38.7 °C, and she had an occasional, mainly dry cough, accompanied by dizziness and general fatigue. She went to the Shaanxi Women’s and Children’s Hospital, where a five-day oral treatment with cefpodoxime proxetil was initiated; however, there was no improvement in her condition. Two days before admission to the intensive care unit (October 15), she complained of worsening shortness of breath. Her body temperature at the time was 38 °C, and she had an occasional cough. She was admitted to the local hospital one day before admission into the intensive care unit (October 16); chest computed tomography (CT) revealed scattered ground-glass dense opacities in both the lungs. Furthermore, we noticed a few nodular shadows in the upper lobes of both the lungs of the patient (Figure 1A and B). With a diagnosis of severe pneumonia, she was referred to the emergency department of the First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University. Her body temperature peaked at 40 °C, which was accompanied by shivering. Oxygen was supplied using a mask at 5–8 L/min, and oxygen saturation fluctuated between 90–93%. Infection-related indices, such as white blood cell count (WBC), neutrophilic granulocyte percentage (NEUT), and procalcitonin (PCT), increased; thus, cefoperazone sodium/sulbactam sodium and moxifloxacin were administered as an anti-infection therapy. However, the patient’s shortness of breath worsened, and her respiratory rate increased. The pulse oxygen saturation decreased to 89%, and the patient was connected to a non-invasive ventilator to assist breathing. Six hours later, the patient still had dyspnea and became irritable The oxygen saturation fell to 44%. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed type I respiratory failure.

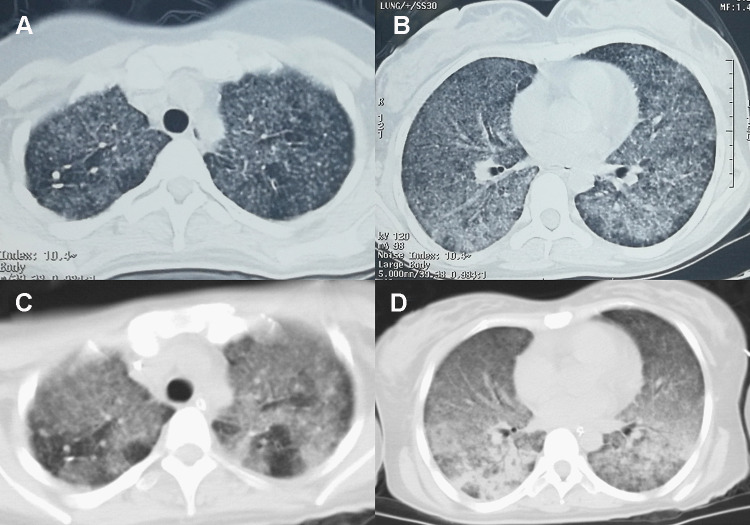

Figure 1.

(A) few nodular shadows in the upper lobes of both lungs, (B) ground-glass dense opacities in both lungs, (C) multiple nodules in the upper lobes of both lungs, (D) multiple patchy high-density shadows in both lungs with uneven density.

Physical examination of the patient revealed the following: a body temperature of 36.9 °C, a heart rate of 123 beats/min, a respiratory rate of 26 breaths/min, and blood pressure of 86/54 mmHg. She was conscious, but had an emaciated body. Ventilation was assisted via a ventilator and tracheal tube intubation. The breathing sound of both lungs was rough, and few wet rales were heard. There was no abnormality in heart and abdominal examination, and slight pitting edema in the lower limbs was observed.

The laboratory test results after admission are listed in Table 1. The imaging results are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of Laboratory Test Indicators in the Patient

| Variable | Value | Reference/Normal Range | Elevated/ Normal/Low |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood cell count | |||

| Haemoglobin | 75 | 110–150 g/L | Low |

| White cell count | 9.66×109 | 3.5–9.5×109/L | Elevated |

| Neutrophil | 97.0% | 40–75% | Elevated |

| Platelets | 141×109 | 125–350×109/L | Normal |

| Lymphocyte count | 0.16×109 | 1.1–3.2×109/L | Low |

| Eosinophils | 0.01×109 | 0.02–0.52×109/L | Low |

| Infection and inflammatory markers | |||

| C-reactive protein | 96.7 | 0–10 mg/L | Elevated |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 23 | 0–20 mm/h | Elevated |

| Procalcitonin | 8.89 | <0.5 ng/mL | Elevated |

| Interleukin-6 | 174.3 | 0–7 pg/mL | Elevated |

| Respiratory Virus antibodies | Legionella pneumophila weakly positive | Negative | Elevated |

| Epstein-Barr Virus DNA | Nuclear antigen IgG 327 U/mL; Capsid antigen IgG 34.5 U/mL | <20 U/mL | Elevated |

| Cytomegalovirus DNA | IgG positive | Negative | Elevated |

| Sputum smear (bacterial/fungus) | Normal | - | Normal |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid culture, blood culture, urine culture | Normal | - | Normal |

| Legionella pneumophila antigen in urine | Normal | - | Normal |

| Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid galactomannan | 0.22 | <0.5 μg/L | Normal |

| 1,3-beta-D-glucan | <10 pg/mL | <60 pg/mL | Normal |

| Tuberculosis | |||

| Tuberculosis-infected T cell | Antigen A 5 SFCs/2.5×105 PBMC; Antigen B 0 SFCs/2.5×105 PBMC | <6 SFCs/2.5×10E5 PBMC | Normal |

| Acid-fast stain in sputum smear | Normal | - | Normal |

| Tuberculin test | Normal | - | Normal |

| Rheumatology | |||

| Autoantibody profile | Normal | - | Normal |

| Immune | Normal | - | Normal |

| Rheumatism | |||

| C-reaction protein | 87.6 mg/L | 0–10 mg/L | Elevated |

| CD8+T-cells | 30.29% | 18.1–29.6% | Elevated |

| CD4+/CD8+ T-cells | 1.57 | 0.8–2.1 | Normal |

| Thyroid function | Normal | - | Normal |

| Liver and kidney function | Normal | - | Normal |

| Albumin | 19.1 | 40–55 g/L | Low |

| Coagulation profile | Normal | - | Normal |

| Arterial blood gas (mechanical ventilation; PEEP, 12 cmH2O; FiO2, 100%) | |||

| PH | 7.335 | 7.35–7.45 | Low |

| PCO2 | 32 | 35–45 | Low |

| PaO2 | 83 | 83–108 | Normal |

| HCO3− | 17.9 | 21–27 mmol/L | Low |

| BE | −8.0 | −3 to +3 | Low |

| Lactate | 3.6 | 0.5–1.6 mmol/L | Elevated |

| Urinalysis | |||

| Protein | 2+ | - | Elevated |

| Occult blood | 3+ | - | Elevated |

| White blood cell | - | - | Normal |

| Myocardial enzyme | |||

| LDH | 1073 U/L | 120–250 U/L | Elevated |

| HBDH | 767 U/L | 72–182 U/L | Elevated |

| CK, CKMB | Normal | - | Normal |

| NT-proBNP | 162.3 pg/mL | 0–125 pg/mL | Elevated |

| Faeces test | Normal | - | Normal |

Abbreviations: PEEP, positive end expiratory pressure; FiO2, fraction of inspiration O2; PH, pondus hydrogenii; PCO2, partial pressure of carbon dioxide; PaO2, arterial partial pressure of oxygen; HCO3-, bicarbonate; BE, base excess; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; HBDH, hydroxybutyrate dehydrogenase; CK, creatine kinase; CKMB, creatine kinase myocardial band; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide.

Table 2.

Summary of Ultrasound and Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy Results in the Patient

| Variable | Check Date | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Echocardiography | 18 Oct. | EF59%, pulmonary artery pressure is 35mmHg, no abnormalities in heart structure and blood flow |

| Abdominal ultrasound | 17 Oct. | No abnormalities |

| Pelvic ultrasound | 17 Oct. | A small amount of fluid (27mm) |

| Gynecological ultrasound | 17 Oct. | Endometrial cavity fluid 23mm×7mm(a little), uterus size 87×69×59(mm), intima media thickness 14mm, uneven echo; Double attachment is normal |

| Fiberoptic bronchoscopy | 17 Oct. | Bronchial patency, the mucosa is slightly congested, the surface was covered with a small amount of yellow sputum scab |

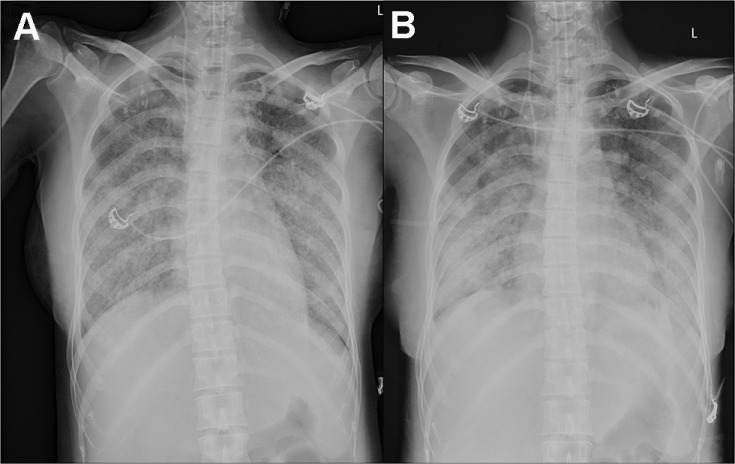

On October 17, 2019, she was admitted to the Department of Critical Care Medicine and was initially diagnosed with severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), septic shock, and moderate anemia. The patient was administered anti-infective moxifloxacin therapy. Due to septic shock, the patient was given fluid rehydration (initial fluid volume: 30 mL/kg) and administered noradrenaline to raise her blood pressure. Thymopetidum injection was used to enhance immunity, and vitamin C was used as an anti-inflammatory agent. A bedside chest X-ray scan revealed double-lung pneumonia (Figure 2A). Fiberoptic bronchoscopy was performed on the same day, and small amounts yellow sputum, scabbing, and mucosa were observed. The alveolar lavage fluid was collected for etiological examination. On the second day of admission, her body temperature peaked to 38 °C; her blood pressure was 109/84 mmHg under noradrenaline treatment (0.2 µg/kg/min), the concentration of oxygen inhaled using mechanical ventilation was 80%, and she was still short of breath and sweating. The patient was given sedation and analgesic treatments. The PCT increased from 8.89 to 18.24 ng/mL, and the C-reactive protein (CRP) level was as high as 142.4 mg/L. The causative pathogen remained unknown, and anti-infection treatment was administered. However, the levels of relevant infection-related markers continued to rise. Therefore, anti-infection treatment with meropenem and linezolid was started on October 19. The treatment led to a gradual improvement in infection indices. On October 21, the PCT was 2.24 ng/mL, blood leukocyte count was 4.49×109/L, the proportion of neutrophils was 82.2%, blood pressure (BP) was 110/70 mmHg after stopping noradrenaline treatment, heart rate (HR) was 86 bpm, respiration rate (RR) was 18 breaths per minute, and the saturation of pulse oxygen (SpO2) was 98%. The use of the ventilator was reduced, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) was 8 cm H2O, and the fraction of inspiration O2 (FiO2) was 45%. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed a pH of 7.438, PCO2 of 40.1 mmHg, PO2 of 118 mmHg, HCO3− of 26.8 mmol/L, BE (base excess) of 2.7 mmol/L, and lactate levels of 2.0 mmol/L. The patient was discharged from the bed with a ventilator, for exercise. Although the infection-related indicators of the patient improved and her general condition was stable, the patient still had a fever with a peak body temperature of 38.4 °C. This occurred mainly in the afternoon and evening and was accompanied by sweating. Further, the CRP was still as high at 90.5 mg/L. Abdominal, pelvic, and gynecological ultrasonography revealed no obvious abnormalities. The examination indices of bacteria, fungi, TB, viruses, specific pathogenic bacteria, and factors related to non-infectious fever were all normal (Table 1), and no pathogenic bacteria were found. However, the patient failed to leave ventilator support. Re-examination of chest CT revealed multiple nodules in the upper lobes of both the lungs and multiple patchy high-density shadows with uneven density in both the lungs (Figure 1C and D). The chest CT showed no improvement on October 16. Combined together, the patient’s pathogenesis, relevant examination, and treatment process led us to believe that she had no infectious diseases. Therefore, we sent the alveolar lavage fluid for an mNGS test. The mNGS results showed that only three sequences of the M. tuberculosis complex group were present; moreover, the Xpert results were positive for M. tuberculosis but negative for rifampicin resistance. Combined with the symptoms and signs of the patient, a diagnosis of pulmonary TB was established, and hematogenous disseminated pulmonary TB was considered. Accordingly, the administration of moxifloxacin, meropenem, and linezolid was stopped. Isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol were administered as anti-TB therapy. Re-examination of chest radiographs on October 25 revealed extensive exudation in both the lungs, with small nodules visible, particularly in the lower lobes of both the lungs (Figure 2B). On October 28, the patient was referred to a specialized TB hospital for treatment. M. tuberculosis culture results were positive. Quadruple anti-TB therapy and ventilator assistance were continued. One month after being transferred from our hospital, the patient died of multiple organ failure.

Figure 2.

(A) A bedside chest X-ray revealed double-lung pneumonia, (B) extensive exudation in both lungs, with small nodules visible, especially in the lower lobes of both lungs.

Discussion

TB is a major cause of death in women of child-bearing age and a common non-obstetric cause of maternal death.10 Studies have shown that women are at a significantly increased risk of active TB infection during pregnancy and postpartum.11,12 An estimated 216,500 (95% confidence interval, 192,000–247,000) pregnant women were diagnosed with active TB globally in 2011,10 and there may be a large number of cases of undetected active TB during pregnancy.4 Ye et al9 reported six cases of pregnant women with TB, in 2019, in whom the hormone level changes during pregnancy led to decreased T cell activity and immunosuppression. This resulted in the reactivation and spread of M. tuberculosis, ultimately leading to hemorrhagic disseminated and extrapulmonary TB.

Reproductive system TB is an important factor that causes tubal infertility, and it has been reported that 20% of the cases of female primary infertility are caused by reproductive system TB.13,14 TB of the female reproductive system leads to chronic inflammatory lesions of the reproductive organs. The incidence of fallopian tube TB is highest, followed by the TB of the endometrium and ovary.15 The patient’s condition is insidious, and there are no other clinical manifestations except infertility. The incubation period from initial infection to the expression of urogenital TB is usually 5–40 years.15

With the gradual maturity of IVF-ET, an increasing number of infertile patients have received this treatment and a large proportion of them are patients with occult genital TB whose TB is activated after receiving IVF-ET.16 After pregnancy, vascular permeability increases, and a large number of TB bacilli spread throughout the body through the bloodstream. This results in hematogenous disseminated and extrapulmonary TB,17 which often presents as severe pneumonia with rapid progression and poor prognosis. Gai et al18 recently reported seven cases of acute miliary tuberculosis in pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer, suggesting that patients with miliary TB have poor pregnancy outcomes. The coexistence of primary infertility, untreated prior pulmonary TB, and fallopian tube obstruction is a high-risk factor for TB dissemination. Therefore, clinicians should be aware of the signs of TB before administering a course of IVF-ET treatment. In patients undergoing IVF, estrogen levels suddenly increase during ovulation induction and the peak levels of serum estrogen are several times higher than the peak value of serum estrogen levels in the natural cycle. This is conducive to the reproduction of M. tuberculosis.3 At the same time, the estrogen, progesterone, and chorionic sex hormones can directly inhibit T cells and induce lymphocyte apoptosis, thereby inhibiting the cellular immune function of the body after superovulation and embryo transfer. This also leads to the rapid reproduction of M. tuberculosis,19–21 which may aggravate the progression of the disease. In addition, the inhibition of lymphocyte function due to glucocorticoid use during IVF-ET therapy may lead to increased risks of TB infection and reactivation.

Studies have shown9 that patients with TB after IVF-ET usually exhibit a fever, with body temperatures as high as 40 °C and pulmonary imaging changes. Most spontaneous abortions occur at 12 to 16 weeks after embryo transfer, which is mainly caused by severe TB toxemia and chorioamnionitis due to the spread of M. tuberculosis through the blood to infect the placenta, thus leading to abortion and fetal death. However, in these patients, early TB-related examinations, such as purified protein derivative (PPD) test, sputum TB smear, TB polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and T-spot, are mostly negative. Therefore, the diagnosis is somewhat difficult, and it is usually 12–13 days from onset to a definite diagnosis.9 In this case, spontaneous abortion occurred 12 weeks after IVF-ET; high fever (body temperature of 40 °C) and pulmonary imaging changes occurred after abortion. The conventional TB tests were negative. Three sequences of TB bacteria were detected in alveolar lavage fluid mNGS, and the Xpert MTB/RIF test was positive, confirming the final diagnosis. The time from onset to diagnosis was approximately six days. Quadruple anti-TB therapy was administered after the diagnosis. After referral to a specialized TB hospital for treatment, sputum TB bacterial culture was used to identify the responsible Mycobacterium. However, the damage caused by the tuberculous toxin to the whole body causes MODS, eventually resulting in the death of the patient. The period from the onset to death is 50 days. With the help of mNGS detection technology, the pathogen could be rapidly and accurately identified, allowing a diagnosis six days earlier than the average time reported in the literature. Untreated prenatal TB increases the risk of perinatal complications. This includes preeclampsia, intrauterine growth delay, prenatal bleeding, low birth weight, low Apgar score at birth, and early fetal death.22,23 Early treatment can reverse this negative effect on perinatal outcomes. Late diagnosis and incomplete or partial pharmacotherapy are associated with poor outcomes.24 Therefore, early diagnosis and treatment of TB are of great significance for improving the survival rate of pregnant women and new-borns.25

As a powerful detection method, mNGS assists in the diagnosis of patients with acute and severe diseases.26 Studies have shown that in terms of pathogen identification, the consistency between mNGS and traditional microbial culture detection results is as high as 77.78%.27 Additionally, it has been reported that mNGS is superior to traditional cultures in the identification of rare infectious pathogens, especially M. tuberculosis (odds ratio=4; 95% CI, 1.7–10.8; P < 0.01), and the sensitivity of mNGS is better than that of cultures (52.5% vs 34.2%) with previous antibiotic use, with little effect on the results.28 Xie et al29 found that mNGS can determine the pathogen in patients with severe pneumonia in early stages, guide the application of antimicrobial drugs, and improve the mortality rate of patients with severe pneumonia. Therefore, it should be widely used in the diagnosis of unidentified infections to assist in pathogen screening, as it has great potential as a diagnostic tool.30

Conclusions

In conclusion, when severe infection occurs in patients undergoing IVF-ET, high vigilance is necessary, and an M. tuberculosis infection test should be conducted as soon as possible. Application of alveolar lavage fluid mNGS is helpful in improving the early etiological diagnosis of patients and is effective in the clinical setting; additionally, it helps in improving the treatment success rate of patients with severe pulmonary infections.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient and she’s families and all staff in the department for their support. This study was supported by the The First Affiliated Hospital of Xi’ an Jiaotong University (CN) (2019ZYTS-12).

Abbreviations

ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; BE, base excess; BP, blood pressure; CRP, C-reactive protein; CT, computed tomography; FiO2, fraction of inspiration O2; HCO3-, bicarbonate; HR, heart rate; IVF-ET, in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer; mNGS, metagenomic next-generation sequencing; MTB/RIF, Mycobacterium tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance; NEUT, neutrophilic granulocyte percentage; PCO2, Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PCT, procalcitonin; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; PH, potential of hydrogen; PO2, Partial arterial oxygen pressure; PPD, purified protein derivative; RR, respiration rate; SpO2, saturation of pulse oxygen; TB, Tuberculosis; WBC, white blood cell; WHO, World Health Organization.

Data Sharing Statement

All the information supporting our conclusions and relevant references are included in the manuscript. There are no datasets related to this case report.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee at The Fifth People’s Hospital of ShaanXi to publish the case details.

Consent for Publication

The patient’s husband gave written informed consent to publish this report, and a copy of the consent document is available.

Disclosure

All authors declare that there are no competing interests.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. Accessed November 10, 2021.

- 2.Dam P, Shirazee HH, Goswami SK, et al. Role of latent genital tuberculosis in repeated IVF failure in the Indian clinical setting. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2006;61(4):223–227. doi: 10.1159/000091498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malhotra N, Sharma V, Bahadur A, Sharma JB, Roy KK, Kumar S. The effect of tuberculosis on ovarian reserve among women undergoing IVF in India. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2012;117(1):40–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.10.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zumla A, Bates M, Mwaba P. The neglected global burden of tuberculosis in pregnancy. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(12):e675–e676. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70338-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Llewelyn M, Cropley I, Wilkinson RJ, Davidson RN. Tuberculosis diagnosed during pregnancy: a prospective study from London. Thorax. 2000;55(2):129–132. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.2.129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathad JS, Gupta A. Tuberculosis in pregnant and postpartum women: epidemiology, management, and research gaps. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(11):1532–1549. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adhikari M. Tuberculosis and tuberculosis/HIV co-infection in pregnancy. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;14(4):234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hongbo L, Li Z. Miliary tuberculosis after in vitro fertilization and embryo transplantation. Afr Health Sci. 2015;15(2):701–704. doi: 10.4314/ahs.v15i2.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye R, Wang C, Zhao L, Wu X, Gao Y, Liu H. Characteristics of miliary tuberculosis in pregnant women after in vitro fertilisation and embryo transfer. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23(2):136–139. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.18.0223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugarman J, Colvin C, Moran AC, Oxlade O. Tuberculosis in pregnancy: an estimate of the global burden of disease. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(12):e710–6. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70330-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zenner D, Kruijshaar ME, Andrews N, Abubakar I. Risk of tuberculosis in pregnancy: a national, primary care-based cohort and self-controlled case series study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185(7):779–784. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201106-1083OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jonsson J, Kühlmann-Berenzon S, Berggren I, Bruchfeld J. Increased risk of active tuberculosis during pregnancy and postpartum: a register-based cohort study in Sweden. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(3):1901886. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01886-2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma JB, Kriplani A, Sharma E, et al. Multi drug resistant female genital tuberculosis: a preliminary report. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang YQ, Shen H, Chen J, Chen ZW. [A prevalence survey of infertility in Beijing, China]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2011;91(5):313–316. Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zajaczkowski T. Genitourinary tuberculosis: historical and basic science review: past and present. Cent Eur J Urol. 2012;65(4):182–187. doi: 10.5173/ceju.2012.04.art1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parikh FR, Nadkarni SG, Kamat SA, Naik N, Soonawala SB, Parikh RM. Genital tuberculosis–a major pelvic factor causing infertility in Indian women. Fertil Steril. 1997;67(3):497–500. doi: 10.1016/S0015-0282(97)80076-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bothamley GH, Ehlers C, Salonka I, et al. Pregnancy in patients with tuberculosis: a TBNET cross-sectional survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):304. doi: 10.1186/s12884-016-1096-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gai X, Chi H, Cao W, et al. Acute miliary tuberculosis in pregnancy after in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer: a report of seven cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):913. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06564-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singh N, Perfect JR. Immune reconstitution syndrome and exacerbation of infections after pregnancy. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(9):1192–1199. doi: 10.1086/522182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilsher ML, Hagan C, Prestidge R, Wells AU, Murison G. Human in vitro immune responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79(6):371–377. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Birku M, Desalegn G, Kassa G, et al. Pregnancy suppresses Mycobacterium tuberculosis-specific Th1, but not Th2, cell-mediated functional immune responses during HIV/latent TB co-infection. Clin Immunol. 2020;218:108523. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2020.108523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Figueroa-Damian R, Arredondo-Garcia JL. Pregnancy and tuberculosis: influence of treatment on perinatal outcome. Am J Perinatol. 1998;15(5):303–306. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-993948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zenhäusern J, Bekker A, Wates MA, Schaaf HS, Dramowski A. Tuberculosis transmission in a hospitalised neonate: need for optimised tuberculosis screening of pregnant and postpartum women. S Afr Med J. 2019;109(5):310–313. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2019.v109i5.13789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jana N, Vasishta K, Jindal SK, Khunnu B, Ghosh K. Perinatal outcome in pregnancies complicated by pulmonary tuberculosis. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1994;44(2):119–124. doi: 10.1016/0020-7292(94)90064-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kothari A, Mahadevan N, Girling J. Tuberculosis and pregnancy–results of a study in a high prevalence area in London. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2006;126(1):48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2005.07.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simner PJ, Miller S, Carroll KC. Understanding the promises and hurdles of metagenomic next-generation sequencing as a diagnostic tool for infectious diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(5):778–788. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y, Sun B, Tang X, et al. Application of metagenomic next-generation sequencing for bronchoalveolar lavage diagnostics in critically ill patients. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2020;39(2):369–374. doi: 10.1007/s10096-019-03734-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miao Q, Ma Y, Wang Q, et al. Microbiological diagnostic performance of metagenomic next-generation sequencing when applied to clinical practice. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(suppl_2):S231–S240. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xie Y, Du J, Jin W, et al. Next generation sequencing for diagnosis of severe pneumonia: China, 2010–2018. J Infect. 2019;78(2):158–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2018.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Street TL, Sanderson ND, Atkins BL, et al. Molecular diagnosis of orthopedic-device-related infection directly from sonication fluid by metagenomic sequencing. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(8):2334–2347. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00462-17s [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]