Abstract

Background

Following the official announcement of the COVID-19 pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) in March 2020 and decreased activity of healthcare systems, relocation of resources, and the possible reluctance of patients to seek medical help, colorectal cancer patients were exposed to significant risks. Given that colon cancer is the third most common cancer and the second deadliest cancer in the world, its timely diagnosis and treatment are necessary to reduce costs and improve quality of life and patient survival. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer.

Methods and Materials

A comprehensive search performed on June 2021 in various databases, including Medline, Web of Science, and Scopus. Keywords such as “diagnosis,” “treatment,” “coronavirus disease-19,” “COVID-19,” “coronavirus disease,” “SARS-CoV-2 infection,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “2019-nCoV,” “coronavirus, 2019 novel,” “SARS-CoV-2 virus,” severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2,” “COVID-19,” “COVID-19, coronavirus disease 19,” “SARS coronavirus 2,” “colorectal neoplasm,” and “colorectal cancer “ was used individually or a combination of these words. All retrieved articles were entered into a database on EndNote X7. Then, studies were first selected by title and then by abstract, and at the end, full texts were investigated.

Results

Of the 850 studies, 43 were identified as eligible. According to studies, the diagnosis of colorectal cancer and the number of diagnostic procedures have decreased. Emergency visits due to obstruction or perforation of the large intestine or in advanced stages of cancer have increased, and a delay in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer has reported from 5.4 to 26%.

Treatment of colorectal cancer has also decreased significantly or has been delayed, interrupted, or stopped. This reduction and delay have been observed in all treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, and long-term radiation therapy; only cases of emergency surgery and short-term radiotherapy has increased. The waiting time for hospitalization and the length of hospital stay after surgery has been reported to be higher. Changes in patients’ treatment plans and complete to partial cessation of hospitals activities—that provided treatment services—were reported.

Conclusion

According to the reduction in the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer due to the COVID-19 pandemic, compensating for the reduction and preventing the continuation of this declining trend, requires serious and effective interventions to prevent its subsequent consequences, including referrals of people with advanced stages and emergency conditions, increasing treatment costs and reducing the quality of life and patients survival.

Keywords: COVID-19, Colorectal cancer, Diagnosis, Treatment, Systematic review

Introduction

In late December 2019, a new strain of coronavirus was reported from China with symptoms such as acute respiratory disease that quickly spread to other parts of the world [1]. The virus, which was named the new coronavirus 2019 or SARS-CoV-2 [2], was declared a public health emergency and international concern by the World Health Organization on January 30, 2020 [1, 3]. The impact of this virus on the function of healthcare systems and the allocation of resources to combat the disease caused by this virus, and also the reluctance of many patients to seek health care in crowded healthcare centers, led to the cessation of routine care in many care centers and subsequently, exposed vulnerable patients, including those with cancer, to significant risks [4, 5]. Colorectal cancer is also one of the cancers that diagnosis and treatment was faced with serious challenges during the COVID-19 crisis.

According to GLOBOCAN 2020, colorectal cancer is the second deadliest and the third most common cancer in the world, accounting for 9.4% of all cancer deaths. Also, more than 1.9 million new cases and 935,000 deaths caused by this disease have occurred in 2020 [6]. Therefore, any delay in the diagnosis and treatment of this cancer can have irreparable consequences, as it is predicted that a delay of 3 months and only a change from stage I/T1 to stage II/T2 causes 88 additional deaths and is imposed $12 million additional costs on the healthcare system. Also, by 6-month delay in the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer, 349 additional deaths per month and $46 million additional costs over 5 years can be expected [7]. It is also predicted that a 2-month delay in surgery will reduce patient survival by more than 9% and a 6-month delay by more than 29% [8].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the diagnosis and treatment of other diseases have also been challenging, so knowing the effect of COVID-19 on the diagnosis and treatment of cancer is essential for healthcare systems for better planning. Therefore, the present study was conducted to investigate the effects of COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer.

Methods and Materials

Search Strategy

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA checklist. A comprehensive search was conducted in three databases including PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, and Web of Science, using the following keywords from 2020 to 2021: “early diagnosis,” “treatment,”” “COVID-19,” “coronavirus disease,” “SARS-CoV-2 infection,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “2019-nCoV,” “coronavirus, 2019 novel,” “SARS CoV-2 virus,” “severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2,” “COVID-19,” “COVID-19, coronavirus disease 19,” “SARS coronavirus 2,” “colorectal neoplasm,” and “colorectal cancer.” AND, OR and mesh term operators were also used to improve the search result. Also, a manual search was performed in reputable scientific journals to find articles related to the full text.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All types of observational studies, addressing the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer diagnosis and treatment, published in the English language were included in the review.

Review studies, case reports, letters to editors, commentaries and reports were also excluded.

Screening and Selection of Studies

All retrieved articles were entered into EndNote X7 software. After removing duplicates, studies were first selected by title and then by abstract. Then, their eligibility was verified by reviewing the full text. Articles that evaluated every aspect of colorectal cancer diagnosis and treatment during the COVID-19 epidemic were included in the analysis.

Data Extraction

To extract the data, the prepared checklist was used and the following information was extracted from each study: surname of the first author, year of publication, country of study, type of study, sample size, age and sex of the target group, period of evaluation and the main findings.

Quality Assessment

“Adapted Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scales” checklist was used to evaluate the quality of the articles in this review [9]. This tool consists of 3 separate sections: selection, comparison and conclusion. Studies were scored based on overall scores and divided into 3 categories: good, moderate and poor.

Selection of Studies

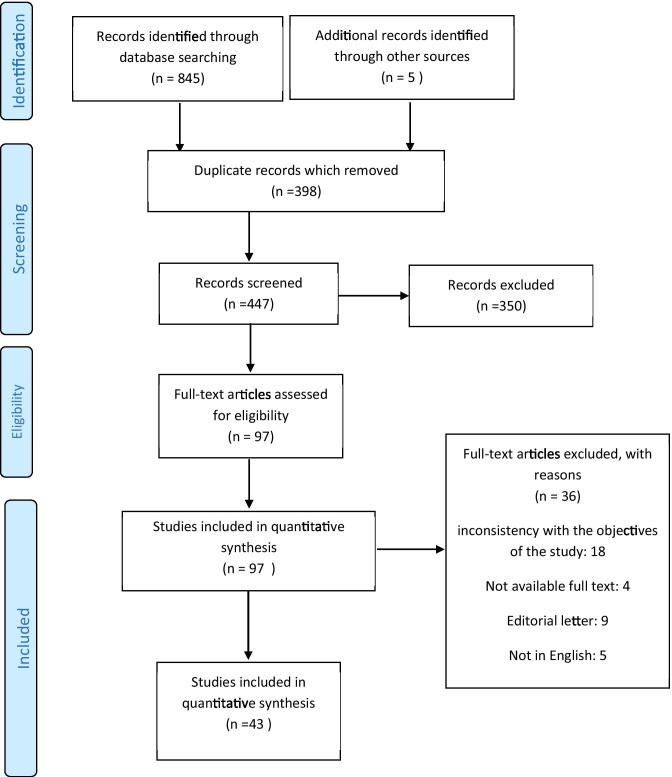

The search result in the databases based on the intended keywords included 850 articles, which after deleting duplicates (398 articles), according to the title and abstract of the remaining articles, 350 articles were deleted. Afterward, a thorough review of the remaining articles was performed; then, 36 other articles were excluded due to publication in a language other than English [5 articles], a letter to the editor [9 articles], etc. Subsequently, the full text of the articles was reviewed, 22 articles were deleted due to lack of access to the full text or inconsistency with the objectives of the study, and finally, 43 articles were analyzed in this systematic review (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow of information through the various phases of the systematic review

Results

Characteristics of Studies and Quality Assessment

According to the goals of this study, included articles were divided in two groups: the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis of colorectal cancer and the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the treatment of colorectal cancer.

Subgroups in diagnosis group were general diagnosis [8, 10–17], emergency diagnosis and in advanced stages [8, 18–20], diagnosis with usual visits [19], diagnosis in screening program [8, 10, 17, 18, 21–24], delay in diagnosis [14, 25] and a number of diagnoses per number of diagnostic methods [16, 24].

Subgroups in treatment group were treatment in general [21, 26–28], surgical treatment [15, 26, 27, 29–41], chemotherapy [26, 30, 36, 39, 41–44], radiation therapy [26, 30, 37], the treatment cost [45], waiting time for hospitalization [8, 27, 45], duration of hospitalization [41, 45, 46], changes in patients’ treatment plan [8, 27, 36, 39, 44], changes in the activity of hospitals providing medical services [19, 39, 47] and follow-up of the suspicious screening cases [26, 45].

Based on the review using the checklist, 22 articles/studies were of good quality, and 16 articles/studies were of medium quality, and 5 articles/studies were of poor quality. The results are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

The characteristics of articles included in a systematic review of diagnosis of colorectal cancer in COVID-19 pandemic

| First author (year) | Place (country) | Sample size | Type of study | Age | Sex | Comparison date | Quality assessment | Examined indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearce et al. (2020) [48] | UK | - | - | All ages | Both | January 1, 2019, through April 30, 2020 | Poor | - New Incidence of colorectal cancer: 54.2% decrease |

| Mizuno et al. (2020) [20] | Japan | - | Retrospective cohort | All ages | Both | December 19, 2019, to August 14, 2020 vs. December 18, 2018, to August 14, 2019 | Good |

- Emergency admission: increase from 18.2 to 38.7%, p < 0.05 - Partial and complete obstruction: increase from 19–42% to 67%, p < 0.05 |

| Lui et al. (2020) [16] | China | - | - | All ages | Both | Jan 21–27 in 2020 vs. Jan 21–27 in 2019 | Good |

- New diagnosis colorectal cancer/week: 37% decrease (from 91.8 to 58); p < 0.001 - Positive rate for colorectal cancer (per 1000 lower endoscopy) in whole period: increase from 75.6 to 118.2; p < 0.001 |

| Dinmohamed et al. (2020) [17] | Netherlands | - | - | 55–75 vs. other ages | Both | 6 January 2020 to 4 October 2020 | Moderate |

In April 2020: - CRC new diagnosis in 55–75 ages: 51% decrease (78 observed vs. 153 expected) - CRC new diagnosis in other ages: 45% decrease (58 observed vs. 105 expected) |

| Suárez et al. (2021) [8] | Spain |

369 (228 before COVID-19 141 after COVID-19) |

- | All ages | Both | March 14 to June 20, 2020 vs. the same time in 2019 | Good |

- Diagnose in Screening program: 33.3% vs. 5.2%; p = 0.000 - New diagnoses of CRC: 53 (48%) decrease (58 vs. 111) - Rate of patients diagnosed in the emergency setting: 12.1% vs. 3.6%; p = 0.048 |

| Shinkwin et al. (2021) [18] | UK |

811: 272 in 2020; 539 in 2019 and 2018 |

Retrospective cohort | All ages | Both | March and June 2020 vs. 2018 and 2019 | Good |

- Emergency presentation: 36.0% vs. 28.6%; p = 0.03 - T4 stages: 34.5% vs. 27.1%; P = 0.03) - Large bowel obstruction: increase from 4.3 to 8.6%; p = 0.01 - Perforation: increase from 3.3 to 4.1%; p = 0.01 |

| Rutter et al. (2021) [12] | UK |

39,790: 4312 COVID-impacted and 35,478 pre-COVID |

Retrospective cohort | All ages | Both | 23 March 2020–31 May 2020 vs. 6 January 2020–15 March 2020 | Moderate |

- Average cancers detected per week: decreased from 394 to 112 - Cancers missing: 71.7% (2828) |

| Purushotham et al. (2021) [14] | UK |

246: 169 before COVID-19 77 after COVID-19 |

All ages | Both | April 2020 to Sept 2020 vs. Oct 2019 to Mar 2020 | Moderate |

- Late stage diagnosis: 5.4% increase (74.0% vs. 68.6%) - Early stage diagnosis: 5.4% decrease (26.0% vs. 31.4%) |

|

| Miller. (2021) [13] | UK |

422: 202 males and 220 females |

Median age 64 years | Both | 1 April to 31 May 2020 vs. same times in 2017–2019 | Moderate | - Average number of monthly cancer diagnosis per month: decrease from 44 vs. 30 | |

| Longcroft-Wheaton et al. (2021) [24] | UK | - | Service evaluation | All ages | Both | 8-week periods in spring, summer and autumn 2019 vs. the first 6 weeks COVID-19 crisis | Moderate |

- Endoscopic procedures/week required to diagnose one CRC cancer: decrease from 47 to 12 - Number of diagnosing new colorectal cancer per week: decreased from 4 to 1.8 |

| Lantinga et al. (2021) [23] | Netherlands | - | Retrospective analysis | - | Both | 15 March to 25 June of 2020 vs. same time in 2019 | Good |

- Number of suspected colon cancer cases: 44% decrease (from 299 in 2019 to 168 in 2020) - Endoscopic suspicion of rectal cancer: 2% decrease (from 56 in 2019 to 55 in 2020) - Increase in suspicion rectal cancer: 0.6% (95% CI 0.4–0.7) in 2020 vs. 0.3% (95% CI 0.2–0.4) in 2019 |

| Ferrara et al. (2021) [49] | Italy | - | - | All ages | Both | Weeks 11 to 20 of 2020 vs. same period of 2018 and 2019 | Poor | -Number of new diagnoses of colorectal cancer: 46.6% decrease (from 333.5 to 178) |

| De Vincentiis et al. (2021) [11] | UK | - | - | All ages | Both | 11th to the 20th week of the years 2018–2020 | Poor | - Average number of new diagnoses of cancer: 62% decrease (from 52.5 to 20) |

| Buscarini et al. (2021) [50] | Italy | - | - | All ages | Both | January 1 to October 31 in 2017–2020 | Moderate | - CRC diagnoses: decreased by 11.9% compared to 2019, in 2020 (4234 in 2020 vs. 4808 in 2019, 4787 in 2018, 4763 in 2017) |

| Brito et al. (2021) [15] | Portugal |

119: 2020: 77 2018: 62 |

Retrospective | All ages | Both | From March to August 2020 vs. equivalent period of 2018 | Moderate | - CRC diagnoses: decreased by 19.5% (62 vs. 77) |

| Boyle et al. (2021) [19] | England and Wales | - | National survey | All ages | Both | In mid-April 2020 | Moderate |

- No reduction in referrals (90 to 100% of the usual number): in 5% of hospitals - Small reduction in referrals (71 to 90% of the usual number): in 10% of hospitals - Large reduction in referrals (20 to 70% of the usual number): in 77% of hospitals - Very few referrals (0 to 19% of the usual number): in 8% of hospitals |

| Bhargava et al. (2021) [22] | Italy | Lockdown group (n = 60); control group (n = 238) | Retrospective controlled cohort | All ages | Both | 9th March–4th May 2020 vs. same time in 2019 | Good |

- “High-risk” adenomas detection rate: 47% in 2020 vs. 25% in 2019, p = 0.001 - Colorectal cancer diagnosis: 5 cases, 8%, in 2020 vs. 3 cases, 1%, in 2019; p = 0.002 |

| Aguiar et al. (2021) [10] | Brazil | - | Cross-sectional | All ages | Both | 1 March to 31 July 2020 vs. same period in 2019 | Moderate |

- Newly diagnosed patients: 46.3% decrease (from 108 to 58) - Referral of patients from the public health system: decrease from 21 to 14% |

| Abdellatif et al. (2021) [25] | UK |

460 in 2020 808 in 2019 |

Retrospective cohort | All ages | Both | 1 March to 31 July 2020 vs. same period in 2019 | Good |

- CRC new diagnosis: 43.1% decrease (from 808 to 460) - Diagnostic delay number: 136 (29%) in 2020 vs. 97 (12%) in 2019 |

Table 2.

The characteristics of articles included in a systematic review of treatment of colorectal cancer in COVID-19 pandemic

| First author; (year) | Location | Sample size | Type of study | Age | Sex | Review period or comparison date | Quality assessment | Examined indicators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beypinar et al. (2020) [43] | Turkey |

Before COVID-19: 13 After COVID-19: 24 |

Retrospective | 22–83 | Both | Before and after of 11th of March 2020 | Good | - Chemotherapy delays: increase from 7.6 to 50% |

| Brunner. (2020) [29] | Germany | 110 hospital | Web-based survey | - | - | April 11th, 2020 | Good |

- 87% of the participating hospitals reduce their total surgical to 34% of their surgical volume for oncological colorectal patients during COVID-19 pandemic - Acceptable waiting time for surgery: up to 2 weeks |

| Byrne et al. (2020) [33] | UK | 29 surgeons | Online survey | - | - | One week during the COVID-19 period | Good |

- Delays in their CR cancer surgeries: 23/29 (79.3%) - Stopped CR cancer surgeries: 3/29 (10.3%) - Performing surgeries in a designated “COVID-free” area: 18/26 (69%) - Relocated cancer surgeries to a private hospital or separate site: 3/26 (11.5%) |

| He et al. (2020) [45] | China |

166: 116 males, 50 females (NTG* group: 95, STG** group: 71) |

Retrospective single-center analysis |

(Mean ± SD) NTG group: 60.34 ± 11.30 STG group: 59.77 ± 12.35 |

Both | From 20th December 2019 to 20th March 2020 (before and after 20th January 2020) | Good |

- Admission waiting (day): 7.95 ± 13.97 days for NTG, 9.59 ± 14.19 days for STG; p = 0.470 - Hospital stay before surgery (day): 4.68 ± 5.88 days for NTG group, 7.42 ± 3.62 days for STG group; p = 0.001 - Proportion of non-local patients: higher in NTG (88.4%) vs. STG (76.05%); (P < 0.05) - Health economics (costs of laboratory tests, anesthesia, total hospitalization expenses, and other costs): higher in STG; (P < 0.05) - Hospital stay after surgery (day): 7.02 ± 3.80 days for NTG, 9.00 ± 3.78 days for STG; p = 0.001 |

| Huddy et al. (2020) [46] | UK | 14 | Research letter | - | Both | Before and after COVID-19 pandemic | Moderate | - The median length of stay: 3⋅5 days for colorectal surgery vs. 5 days for laparoscopic segmental colonic resection prior to COVID-19 |

| Raj Kumar et al. (2020) [26] | India | - | Retrospective observational | - | Both | Between January and May 2020 | Moderate |

- Number of patients seeking or receiving treatment: 65% decline, from 1511 to 506 - Follow‐up screening, lower GI endoscopy (sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy): 90% drop, from 230 to 30 - Total patients planned for radiation: 45% drop, from 70 to 39 - Total patients planned for long-term radiation treatment (LCTR): 88% drop, from 25 to 3 - Total patients planned for short-term radiation treatment (SCTR): 200% increase, from 10 to 21 - Planned for chemotherapy: 70% drop, from 310 to 96 - Planned for surgery- upfront/ post-neoadjuvant: 78% drop, from 65 to 14 - Palliative management: 80% drop, from 15 to 3 - Planned for stoma closure: 83% drop, from 12 to 2 - Surgical procedures: 40% drop, from 93 to 52 |

| Singh et al. (2020) [47] | India | 208 oncosurgeons | Cross-sectional |

31–66 (mean ± SD: 39 ± 7) |

Both | Between 18 and 27th May 2020 (during the nationwide lockdown) | Moderate |

Dedicated oncology and hospitals in green zones vs. multispecialty hospitals and red zones: - Done colorectal oncology surgeries: 89.3% vs. 75.9%, P = 0.04 |

| Sun et al. (2020) [44] | China | 62 patients in 12 hospitals | - | - | Both | By 21 February 2020 | Good |

- Total rate of delay or regimen modification: 43.6% - Delay to receiving adjuvant chemotherapy (aCTx): 31 (50%) with mean delay 13.6 ± 6.1 days - Modifying treatment regimen into single-agent capecitabine: 6 (9.7%) - Total delay incidence in hospitals recruiting patients from the surgery department than from the internal oncology department: 82.5% vs. 18.5%; p < 0.001 |

| Allaix et al. (2021) [34] | Italy | 75 in 2019, 74 in 2020 | Retrospective review |

2019: 69 (16–93) 2020: 67 (18–89) |

Both | Between March 9 and April 15, 2020, compared to the same period in 2019 | Good |

- Operation delay in patients with COVID-19 infection: after obtaining a double check of swab negativity at 15 days - Colorectal resections: not changes: 75 in 2019 and 74 in 2020 - Rate of resections for cancer: slightly increased; 32 (42.6%) in 2019 vs. 44 (59.5%) in 2020; p = 0.049) |

| Boyle et al. (2021) [19] | England and Wales | 123 hospitals | National survey | - | - | Mid-April 2020 | Moderate |

- Colorectal resection activity by cumulative COVID-19 rate and the availability of surgical ‘cold sites: - 0–10% of usual capacity: 28 (23%) - 11–70% of usual capacity: 53 (43%) - 71–100% of usual capacity: 42 (34%) - Alternation in treatment plans: 69 (56%) hospitals for 50% of CRC patients: - 61 hospitals (50%): delay in treatments due to COVID-19 infection risks, - 61 (50%): delay in tissue diagnosis and radiological staging, - 57 (46%) delays in treatment due to diversion of resources - 47 hospitals (38%) changes in length and type of chemotherapy treatment in more than 50% of their patients, - 23 hospitals (19%) use of temporizing treatments changes in more than 50% of their patients: stenting of obstructing cancers and radiotherapy for rectal cancer with a ‘long wait’ |

| Brito et al. (2021) [15] | Portugal |

2020: 62 2018: 77 |

Retrospective study | - | Both | From March to August 2020 vs. same period of 2018 | Good | - Number of patients: 19.5% decline, from 77 to 62 |

| Cui et al. (2021) [32] | China |

2020: 67 2019: 101 2018: 104 |

Retrospective |

Mean ± SD: 2020: 67.1 ± 11.4 2019: 67.0 ± 12.0 2018: 64.3 ± 11.2 |

Both | February 1 to May 31, 2020, vs. same 4-month period in 2018 and 2019 | Good |

- Numbers of patients that underwent elective colorectal surgery: 35% decreased, from 104 in 2018 and 101 in 2019 to 67 in 2020 - Proportion of patients without any digestive system symptoms decreased to 3% and severe clinical symptoms decreased by 20.9% - Compared with 2019, the average post-operative stay was significantly shorter than in 2018 (9.6 ± 3.7 vs. 12.1 ± 9.1, p = 0.015) - Durations of surgery, min, mean ± SD: 206.21 ± 63.64 in 2019 vs. 245.22 ± 88.94; p = 0.002 |

| Baxter et al. (2021) [42] | Scotland | - | - | - | Both | 8 weeks prior to 16 March 2020 to 16 July 2020 | Poor | - Systemic anticancer therapy (SACT) treatment: weekly fall 43.4% for 6–12 April |

| Gurney et al. (2021) [30] | New Zealand | - | National collections | All ages | Both | 2018–2020 | Moderate |

- Curative surgeries (during the shutdown period): 14.5% decreased, from 753 to 644 - Intravenous (IV) chemotherapy no obvious substantial reduction - Radiation therapy: 8% decrease |

| Huddy et al. (2021) [35] | UK | 10: 5 male, 5 female | - |

77 (mean ± SD: 59–79) |

Both | Between 12th May and 30th July 2020 | Moderate |

- Delay in robotic surgery: 60% - Median time from diagnosis to treatment for colorectal patients: 94 days (inter-quartile range 51–105) vs. 62-day treatment target |

| Kamposioras et al. (2020) [28] | UK | 129 | Descriptive analysis | ≥ 31 | Both | Between May 18 and July 1, 2020 | Moderate | - Delayed, break, or canceled in treatment status: 29 (23.4%) |

| Koczkodaj et al. (2021) [21] | Poland | - | - | - | Both | From January to September 2019 vs. same time in 2020 | Poor | - Absolute number of issued ODaTCs*** Comparing January and April 2020: 51% decline, from 4410 to 2161 |

| Lechner et al. (2021) [31] | Austria | - | Cross-sectional study | - | Both | 6 weeks before and after lockdown (March 16–April 26, 2020) | Moderate | - Operations performed for colorectal cancer: 60% decline, from 10 to 4 |

| Merchant et al. (2021) [36] | UK |

2019: 47 2020: 56 |

Prospective cohort study | Both |

11 weeks following the national lockdown on 23rd March 2020, vs. same time period in 2019 |

Good |

- Cancer resections: 30% increase, from 33 to 47 - Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy: decreased from 30 to 19% - Performed open: increase from 26 to 48%, p = 0.03 due to our initial policy of avoiding laparoscopic surgery - Colorectal cancer resections: decrease in May, June, and July 2020, but numbers have now increased and exceeded the 2019 numbers - MDT decisions for cancer patients: - Alternation of treatment plan: 21% with surgery operation - Change treatment plan from chemotherapy to surgical follow-up: 8 patients |

|

| Morris et al. (2021) [37] | England | - | Population-based study | - | Both | From Jan 1, 2019, to Oct 31, 2020 | Good |

- Number of cases referred for treatment: decreased by 22% (95% CI 8–34), from a monthly average of 2781 in 2019 to 2158 referrals in April, 2020 - Numbers receiving surgery: decreased 31% (95% CI 19–42) in April, 2020 (lower proportion of laparoscopic and a greater proportion of stomaforming procedures) - Neoadjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer: increase 44% (95% CI 17–76) due to greater use of short-course regimens - Use of short-course regimen: drop in June, 2020 and remained above 2019 levels until October, 2020 |

| Samani et al. (2021) [51] | UK |

Before COVID-19: 76 After COVID-19: 35 |

Retrospective review | - | Both | 6 months after and before 23 March 2020 | Good | - The median time interval between procedures (time interval between index (diagnostic) and follow-up (therapeutic) procedures): 16 weeks (IQR 12–20) in after COVID-19 group vs. 8 weeks (IQR 5–13) in before COVID-19 group; p = 0.001 |

| Santoro et al. (2021) [27] | 84 countries | 1051: 827 males, 224 females | International survey | - | Both | May 20eJune 10, 2020 | Good |

- Total delay: 745 (70.9%) - Change in the initial surgical plan: 48.9% (365/745) - Shift from elective to urgent operations: 26.3% (196/745) - Delay in Colorectal cancer surgery: 58.3% (434/745) - Delay from 5 to 8 weeks beyond normal wait time: 90.1% (391/434) - Exceeding 8 weeks beyond normal wait time: 9.9% (43/434) |

| Serban et al. (2021) [38] | Romania | - | Retrospective comparative study | - | Both | April and July 2020 vs. a similar period in 2019 | Moderate | - Emergency surgery for complications such as occlusion or tumor perforation: increased in 2020, 32 vs. 6.97%; P = 0.0039 |

| Suárez et al. (2021) [8] | Spain |

169 (111 before COVID-19 58 after COVID-19) |

- | All ages | Both | March 14 to June 20, 2020, vs. the same time in 2019 | Good |

- Number of cases referred for treatment: decreased 48%, from 111 to 53 cases - Time between histological confirmation date and first treatment date: 36.55 days in group A vs. 36.40 days in group B; P = 0.963 - Change in treatment decisions of the new CRC cases in 2020: 8% (4/51) - Modify the scheduled treatment in CRC cases before COVID-19 pandemic |

| Tejedor et al. (2021) [39] | Spain | 301 | Ambispective analysis | Mean ± SD: 68.2 ± 16 | Both | From February 1, 2020, to May 31, 2020 | Good |

- Delay due to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (nCRT): 1.7% (5/301) - Change in treatment management: 61.1% (187/301) - Surgery delay > 30 days: 24% (72/301) - Did not undergo surgery: more than 3% - Hospital activity: 33.3% Only emergent surgery, 1.23% re-scheduled or referred elective surgery, 55.6% asymptomatic colon or rectal cancer after neoadjuvant treatment |

| Tschann et al. (2021) [40] | Austria | 134: 76 male and 58 female | - | - | Both | 1 January 2019 and ending on 31 December 2020 | Good |

- Procedures during first lockdown vs. same period in 2019: 71.4% decrease (2019, n = 14 vs. 2020, n = 4; p = 0.02) - Surgical CRC cases were comparable in 2019 (n = 71) and 2020 (n = 63) - Emergency cases: increase 25%, from 9 to 12; p = 0.03 |

| Xu et al. (2021) [41] | China | - | Retrospective | - | Both | Between January 1, 2020, and May 3, 2020, vs. between January 1, 2019, and May 3, 2019 | Good |

- Number of endoscopic treatments per month: 76% decreased, from 113 to 27 - Number of outpatient stoma closure per month: 35.6% decreased, from 16,087 to 10,367 - Chemotherapy in the outpatient department: 17.1% decreased, from 2490 to 2127 - Care endoscopy: 48.5% decreased, from 2785 to 1435 - Endoscopic treatment: 76.1% decreased, from 113 to 27 - Stoma closure between January 2020 and February 2020: 7.2% decreased, from 97 to 90 - Mean hospital stay (days): 8.8 ± 3.1 vs. 6.8 ± 2.2; t = − 5.238, p < 0.001 - Palliative surgeries: decreased in February 2020 - Mean hospital stay (days): 11.0 ± 4.3 vs. 9.1 ± 3.1; t = − 3.087, p = 0.002 - Multidisciplinary surgery: decreased from late January to early March, for elderly and patients with liver metastasis - Mean hospital stay (days): 14.3 ± 4.3 vs. 12.3 ± 3.3; t = − 2.007, p = 0.049 - Curative resection (between late January and late March): 42.4% decreased, from 373 to 215 - The proportion laparoscopic surgeries: 49.4% vs. 39.5% |

*NTG normal-time group, **STG special-time group (based on hospitalization date), ***ODaTCs Oncology Diagnosis and Treatment Cards

The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Diagnosis of Colorectal Cancer

General Diagnosis

Decreased diagnosis of new cases of colorectal cancer during COVID-19 pandemic is seen in most countries, as Spain has reported 48% reduction [8] and Brazil has reported 46.3% reduction in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer [10].

Numerous studies have been conducted in the UK and various studies have reported 54.2% [48], 43.1% [25], and 62% [11] reduction in the diagnosis of new cases of colorectal cancer. According to the results of other studies, the average number of cancer cases detected per week has decreased by 71.3%, and it seems that 71.7% (2828) of cases of colorectal cancer have not been diagnosed during this period [12]. Also, the average number of monthly diagnoses of cancer has decreased from 44 cases in the last 3 years (2017–2019) to 30 cases by February 2020 [13]. One study found that the diagnosis of colorectal cancer, after a 70% decrease in April 2020, has reached the expected level after 5 months with a gradual increase [14].

In Italy, the reduction in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer in 2020 was reported to be 11.9% [50], 19.5% [15], and 46.6% [49]. In Hong Kong, after the diagnosis of the first case of COVID-19, the mean number of colorectal cancer diagnosis decreased by 37%, from 91.8 to 58 cases per week (p < 0.001) [16]. In the Netherlands, the number of colorectal cancer diagnoses in people under 55 and over 75 in the first weeks of April was significantly lower than expected (45% decrease), but after that, it reached the expected level and remained constant since [17].

Emergency Diagnosis and in Advanced Stages

In Spain, it was observed that, in 2020, a higher rate of patients were diagnosed in emergency situations (12.1% vs. 3.6% in 2019; p = 0.048) [8]. In the UK, the number of emergency visits in 2020 was higher than in 2019 and 2018 (36.0% vs. 28.6%; p = 0.03), and the diagnosis of T4 stage cancer during 2020 was higher than in 2018–2019 (34.5% vs. 27.1%; P = 0.03). Colon obstruction also increased from 4.3% in 2019 and 2018 to 8.6% in 2020 (p = 0.01) and colonic rupture from 3.3% in 2018–2019 to 4.1% in 2020 (p = 0.01) [18]. In England and Wales, due to the prevalence of COVID-19, most hospitals experienced a significant reduction in the number of emergency visits with advanced stages of colorectal cancer [19]. In Japan, admission of emergency cases increased from 18.2 to 38.7% (p < 0.05) and partial or total obstruction of colon increased from 19–42 to 67% (p < 0.05) [20].

Diagnosis with Usual Visits

In England and Wales, due to the prevalence of COVID-19, only 6 hospitals (5%) out of 123 hospitals did not report a decrease in their number of patient visits due to colorectal cancer and stated that their number of patient visits was more than 90% of the usual number. Also, 12 hospitals (10%) saw a slight decrease (71 to 90% of the usual number) in the number of patient visits, 95 hospitals (77%) reported a large decrease (20 to 70% of the usual number), and 10 hospitals (8%) reported a significant decrease in their patient visits (0 to 19% of usual number), [19].

Diagnosis in Screening Program

In Spain, the diagnosis of colorectal cancer in screening programs decreased from 33.3 to 5.2% (p = 0.000) [8]. In the Netherlands, the number of people diagnosed with colorectal cancer among people aged 55 to 75 (those in the target group of the 2-year FIT screening program) was 48.7% lower than the expected number since early May (6 weeks after the cessation of colorectal cancer screening), and from the end of June, the number of diagnoses reached the expected level [17]. There was also a relative increase in suspected cases of rectal cancer (0.6% [95% CI 0.4–0.7] vs. 0.3% [95% CI 0.2–0.4], P < 0.001), while the number of suspected cases of colon cancer and endoscopic cases of suspected rectal cancer decreased by 44% and 2%, respectively [23].

In Poland, the issuance of oncology diagnosis and treatment cards (ODaTCs) decreased by 3.8% [21]. This decrease was more evident in April, so that, in April 2020, 2063 cards were issued, and in the same month in 2019, this number was equal to 3980, and this represents a 51% decrease in referral cases [21]. In Italy, in the screening program that was carried out during the restriction period, the rate of “high-risk” adenomas was significantly higher (47% vs. 25%), (p = 0.001) and with fewer examinations during the restriction period, a significantly higher number of colon cancer was detected (5 cases, 8%, vs. 3 cases, 1%, p = 0.002) [22]. In the UK, the number of colon cancer diagnoses in endoscopic centers decreased from 4 cases per week to 1.8 cases [24], and in Brazil, the number of referrals from the public health system to the hospital for a definitive diagnosis dropped from 21 to 14% [10].

Delay in Diagnosis

Studies in the UK have reported different diagnosis delays. In one study the delay in diagnosis increased from 97 cases (12%) in 2019 to 136 cases (26%) in 2020 [25], and in another study, the delay in diagnosis of colorectal cancer increased by 5.4% (74.0% vs. 68.6%), and as a result, the early diagnosis of cancer decreased from 31.4 to 26% [14].

Number of Diagnoses per Number of Diagnostic Methods

In the UK, the endoscopic procedures required to diagnose one case of colorectal cancer have been reduced from 47 to 12 cases per week [24]. In Hong Kong, the rate of positive colorectal cancer cases per 1000 endoscopies increased from 75.6 to 118.2 over the entire period (p < 0.001) [16].

The Effect of COVID-19 Pandemic on the Treatment of Colorectal Cancer

Treatment in General

The results of various studies show that the treatment of colorectal cancer has decreased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic. In India, for example, the number of patients referred for treatment or under treatment decreased by 65% [26]. In Spain, the number of referrals for treatment in 2020 decreased by 48% [8], and in Poland, the number of colorectal cancer treatments decreased by 51% from January to April 2020 [21]. The results of an international survey in 84 countries also showed that treatment has been delayed in 70.9% of colorectal cancer cases during the COVID-19 pandemic [27]. In the UK, the treatment of 23.4% of colorectal cancer patients was delayed, interrupted, or stopped [28].

Surgical Treatment

The results of various studies show that colorectal cancer surgery has significantly decreased during the COVID-19 pandemic. The rate of this decrease was 34% in Germany [29], 19.5% in Portugal [15], 14.5% in New Zealand [30], and 60% in Australia [31]. In India, colorectal cancer surgery has generally decreased by 40%, including upfront/ post-neoadjuvant surgery by 78%, palliative care by 80%, and stoma closure by 83% [26]. In China, elective colon surgery showed a 35% reduction. Also, the duration of surgery in 2020 (245.22 ± 88.94) compared to 2019 (206.21 ± 63.6) showed an increase (p = 0.002), [32].

In the UK, 79.3% of surgeons delayed their surgeries, and 10.3% stopped their surgeries. Also, 69% of them performed their surgery in places free of COVID-19, and 11.5% transferred their cancer surgery to a private hospital or a separate place, while only 11.5% continued to perform their surgery in previous places [33]. In Italy, despite the similar number of colorectal resection surgeries in 2019 and 2020 (75 in 2019 and 74 in 2020), the percentage of colorectal resection due to cancer has increased (32 cases or 42.6% in 2019 vs. 44 cases or 59.5% in 2020; p = 0.049). Also, the surgery of patients whose tests were positive for COVID-19 was delayed by 15 days until they receive two negative results [34].

In UK, with the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, robotic surgery was delayed for 60% of colorectal cancer patients, increasing the time of diagnosis to treatment from 62 to 94 days [35]. Colorectal resection surgery generally increased by 30% and fluctuated in the long run, so that it decreased in May, June, and July, and then increased, and the number of open surgeries increased in 2020, from 26 to 48% (p = 0.03) [36]. Also, in England, the number of surgeries for referred patients decreased by 31% (95% CI: 19–42) with less laparoscopic procedures, and stomaforming procedures accounting for a larger share [37].

The results of an international survey in 84 countries showed that during the COVID-19 crisis, 70.9% of colorectal cancer cases were delayed, and in 90.1% of cases, the delay was 5 to 8 weeks longer than usual and in 9.9% of cases, the delay was more than 8 weeks [27]. In Romania, emergency colorectal cancer surgery increased due to obstruction or perforation (32 vs. 6.97%; P = 0.0039), [38]. In Spain, 27% of colorectal cancer surgeries were performed with a delay of more than 30 days, and more than 3% of patients refused to undergo the surgery [39]. In Austria, in the first public restrictions, colon cancer surgery decreased by 71.4% (p = 0.02) and emergency surgery cases increased by 25% (p = 0.03) [40].

In China, the number of outpatient stoma closures per month decreased by 35.6% and in patients with nonlocal perforation, it decreased by 41.7%. Also, palliative surgeries decreased in February 2020 and multidisciplinary surgery decreased from late January to early March, mainly for the elderly and patients with liver metastases. Curative resection showed a 42.4% decrease from late January to late March. The proportion of patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery was 49.4, which was significantly higher than 39.5 in the same period in 2019 [41].

Chemotherapy

The results of various studies show that colorectal cancer chemotherapy during COVID-19 pandemic has declined in some countries, including India by 70% [26], Scotland by 43.4% [42], and the UK where chemotherapy cases have declined from 30 to 19% [36], while in New Zealand, it has not decreased significantly [30]. In Turkey, the delay in chemotherapy increased from 7.6% in the pre-pandemic period to 50% in the post-pandemic period [43], and in Spain, it was delayed in 1.7% of patients [39].

In China, outpatient chemotherapy decreased by 17.1% [41], and 43.6% of patients experienced a delayed chemotherapy (50%) or had their treatment regimen changed (9.7%), [44]. Also, the rate of delay in hospitals to which patients were referred from the surgical wards was higher than in hospitals to which patients were referred directly from the oncology wards (82.5% vs. 18.5%; p < 0.001) [44].

Radiation Therapy

In India, the percentage of patients receiving long-term radiation treatment (LCTR) has decreased by 45%, and the number of patients receiving short-term radiation treatment (SCTR) has increased by 200% [26]. In New Zealand, radiotherapy has dropped by 8% [30]. In England, neoadjuvant radiotherapy for rectal cancer increased by 44% (95% CI: 17–76), and the use of short-term treatment regimens decreased in June 2020 and then increased until October 2020 [37].

The Treatment Cost

In China, treatment costs were higher in patients who attended after the COVID-19 pandemic than in those who attended before the pandemic (P < 0.05) [45].

Waiting Time for Hospitalization

In China, the waiting time for hospitalization in patients who attended after the COVID-19 pandemic (9.59 ± 14.19 days) was longer than in patients who attended before the pandemic (7.95 ± 13.97 days) [45]. In the UK, the mean time interval between colorectal cancer diagnosis and treatment during the pandemic (16 weeks (IQR 12–20)) was longer than before pandemic (8 weeks (IQR 5–13)) (p = 0.001) [52]. In an international survey, it was shown that, in 90.1% of cases, the delay time was 5 to 8 weeks longer than usual, and in 9.9%, it was longer than 8 weeks [27]. In Spain, the time interval between diagnosis and treatment before and after COVID-19 pandemic showed no difference [8].

Duration of Hospitalization

In China, the length of hospital stay after surgery was longer in patients who attended after the COVID-19 pandemic than in patients who attended before the pandemic (P < 0.05), [45]. Also, the average day of hospital stay for all surgical procedures during the pandemic was significantly higher than the average day in the same period in 2019. This figure for stoma closure surgery was 8.8 ± 3.1 vs. 6.8 ± 2.2, p < 0.001, for palliative surgery was 11.0 ± 4.3 vs. 9.1 ± 3.1, p = 0.002, and for multidisciplinary surgery was 14.3 ± 4.3 vs. 12.3 ± 3.3, p = 0.049 [41].

In the UK, average hospital stay (3.5 days) in the post-pandemic period was lower in patients who had undergone surgery than in patients who had undergone sigmoidoscopy (5 days) prior to COVID-19 crisis [46].

Changes in Patients’ Treatment Plan

In China, the treatment plans of 9.7% of patients undergoing chemotherapy were changed [44]. In the UK, changes were made to patients’ treatment plans, and they used fewer short-term radiotherapy programs and preferred surgery to chemotherapy [36].

The results of an international survey showed that the delay in treatment was 48.9% due to a change in surgical program and 26.3% due to a change in elective surgery to emergency surgery [27]. In Spain, the treatment plan was changed in a number of patients who had been diagnosed before the COVID-19 pandemic and in 8% of newly diagnosed patients [8]. Another study also showed that 62% of patients’ treatment plans have been changed [39].

Changes in the Activity of Hospitals Providing Medical Services

In India, during the national quarantine period, more surgeons performed colorectal cancer surgery in specialized oncology hospitals and green areas in terms of COVID-19 prevalence compared to multidisciplinary hospitals and red areas in terms of COVID-19 prevalence (89.3% vs. 75.9%; P = 0.04) [47].

In England and Wales, 23% of hospitals reduced their activities to 0–10% of their normal capacity and 43% of hospitals reduced their activities to 11–70% of their normal capacity, only 34% of hospitals operated at 71–100% of their normal capacity [19]. Also, 56% of hospitals replaced the treatment plan for 50% of their patients, 47 hospitals (38%) reported changes in the length and type of chemotherapy treatment in more than 50% of their patients, and 23 hospitals (19%) reported the use of interim treatments in more than 50% of their patients, such as stent insertion for obstructive cancers and radiation therapy for rectal cancer with a “long waiting period” [19]. In Spain, 33.3% of hospitals performed only emergency surgery, 1.23% performed delayed or referral surgery, and 55.6% accepted asymptomatic colorectal cancer after chemotherapy [39].

Follow-up of the Suspicious Screening Cases

In India, the follow-up of screening cases for sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy reduced by 90% [26].

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer by systematic review approach and the final analysis was performed based on 43 articles related to the purpose of the study. Due to the high prevalence of colorectal cancer and its high mortality rate in European countries, the USA, and India and China in Asia [53], most eligible studies have been conducted in European countries 38 articles as well as India and China (6 articles).

As cancer-screening programs have been reduced or stopped following the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, the diagnosis of cancers, including colorectal cancer, has been facing with challenges. Most studies have reported that the diagnosis of colorectal cancer has been significantly reduced [8, 10–17, 25, 48–50]. This reduction included a reduction in the overall diagnosis of cancer, a reduction in routine referrals [19], and a reduction in cancer detection through screening programs [8, 10, 17, 21–24]. At least 2828 colorectal cancer cases have not been diagnosed in the UK [12].

Also, due to the decreased participation in screening programs and referrals of suspected people to diagnostic centers, the number of diagnostic methods required to identify cancer has decreased [16, 24] and the percentage of positive cases has increased [16].

Since the lack of early detection of cancer cases leads to consequences such as disease progression, delayed treatment, and increased mortality [54], all studies conducted on colorectal cancer show an increase in urgent referrals or after the onset of consequences such as obstruction or rupture of the large intestine or in advanced stages of cancer [8, 18–20]. In general, during the COVID-19 crisis, the delay in diagnosis of colorectal cancer has been reported from 5.4 [14] to 26% [25].

Another effect of COVID-19 pandemic has been a delay in the treatment of colorectal cancer, which can have detrimental consequences for the overall and disease-free survival of patients [55], so that, with the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, the number of referrals for colorectal cancer treatment has decreased significantly [8, 21, 26] or has been delayed, interrupted, or stopped [27, 28]. This reduction or delay is seen in all treatments including surgical treatment [15, 26, 27, 29–33, 35–37, 39–41], chemotherapy [26, 36, 39, 42–44], and long-term radiation therapy [26, 37], only cases of emergency surgery [38, 40] and short-term radiotherapy [26, 37] show an increase. However, in Italy, the number of colorectal resection surgeries [34] and, in New Zealand, the cases of chemotherapy before and after COVID-19 pandemic have remained unchanged [30].

During COVID-19 pandemic, the waiting time for hospitalization and admission has also been increased [27, 45, 52], and up to 16 weeks delay has been reported [52], but only one study in Spain reported no difference in this regard before and after the COVID-19 crisis [8]. Also, the length of hospital stay after surgery has been reported to be higher in patients who have attended after the COVID-19 pandemic [41, 45]. In the UK, however, the average hospital stay was lower in patients who had undergone surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic than in patients who had undergone sigmoidoscopy prior to the COVID-19 crisis [46].

Some studies have also reported changes in patients’ treatment plans, including changes from chemotherapy to surgery, changes from long-term to short-term radiation therapy, and from elective surgery to emergency surgery, and the main reason for these changes has been reported to be reducing the risk of developing COVID-19 in patients [8, 27, 36, 39, 44].

COVID-19 disease has affected the activities of hospitals that provide treatment services to patients with colorectal cancer, and given the prevalence of this cancer in their area of activity, this effect ranges from complete or partial cessation of activities or changing treatment plans to alternative methods of treatment or relocation of treatment center [19, 39, 47]. In general, the COVID-19 pandemic has posed serious challenges to all aspects of colorectal cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Conclusion

As the results of this study show, the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer during COVID-19 pandemic have faced serious challenges, which can be a wake-up call for diagnostic systems, especially healthcare systems in the post-COVID-19 crisis, because they will be faced with a large number of patients with advanced stages of the disease who may require emergency treatment. Therefore, it is necessary to implement serious and efficient interventions to compensate for the reduction in treatment and diagnosis of colorectal cancer and prevent the continuation of this reduction.

Author Contribution

All authors contributed equally.

Availability of Data and Material

NA.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

NA

Consent to Participate

NA

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Maukayeva S, Karimova S. Epidemiologic character of COVID-19 in Kazakhstan: a preliminary report. North Clin Istanb. 2020;7(3):210–213. doi: 10.14744/nci.2020.62443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erfani A, Shahriarirad R, Ranjbar K, Mirahmadizadeh A, Moghadami M. Knowledge, Attitude and practice toward the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) outbreak: a population-based survey in Iran 2020. Bull World Health Organ.

- 3.Kandel N, Chungong S, Omaar A, Xing J. Health security capacities in the context of COVID-19 outbreak: an analysis of International Health Regulations annual report data from 182 countries. The Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1047–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30553-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jazieh AR, Akbulut H, Curigliano G, Rogado A, Alsharm AA, Razis ED, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on cancer care: a global collaborative study. JCO global oncology. 2020;6:1428–1438. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amador M, Matias-Guiu X, Sancho-Pardo G, Contreras Martinez J, de la Torre-Montero JC, Peñuelas Saiz A, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the care of cancer patients in Spain. ESMO open. 2021;6(3):100157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians. 2021;71(3):209–49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Degeling K, Baxter NN, Emery J, Jenkins MA, Franchini F, Gibbs P, et al. An inverse stage-shift model to estimate the excess mortality and health economic impact of delayed access to cancer services due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2021;17(4):359–367. doi: 10.1111/ajco.13505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suárez J, Mata E, Guerra A, Jiménez G, Montes M, Arias F, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic during Spain's state of emergency on the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2021;123(1):32–36. doi: 10.1002/jso.26263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wells GA, Shea B, O'Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, et al. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses 2021 Available from: http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 10.Aguiar S, Riechelmann RP, de Mello CAL, da Silva JCF, Diogenes IDC, Andrade MS, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on colorectal cancer presentation. Br J Surg. 2021;108(2):e81–e82. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znaa124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Vincentiis L, Carr RA, Mariani MP, Ferrara G. Cancer diagnostic rates during the 2020 'lockdown', due to COVID-19 pandemic, compared with the 2018–2019: an audit study from cellular pathology. 2021;74(3):187–9Z [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Rutter MD, Brookes M, Lee TJ, Rogers P, Sharp L. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK endoscopic activity and cancer detection: a national endoscopy database analysis. Gut. 2021;70(3):537–543. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller J, Maeda Y. Short-term outcomes of a COVID-adapted triage pathway for colorectal cancer detection. Cancer causes & control : CCC. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Purushotham A, Roberts G, Haire K, Dodkins J, Harvey-Jones E, Han L, et al. The impact of national non-pharmaceutical interventions ('lockdowns') on the presentation of cancer patients. ecancermedicalscience. 2021;15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Brito M, Laranjo A, Sabino J, Oliveira C, Mocanu I, Fonseca J. Digestive Oncology in the COVID-19 Pandemic Era. GE Portuguese J Gastroenterol. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Lui TKL, Leung K, Guo CG, Tsui VWM, Wu JT, Leung WK. Impacts of the coronavirus 2019 pandemic on gastrointestinal endoscopy volume and diagnosis of gastric and colorectal cancers: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(3):1164–6.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dinmohamed AG, Cellamare M, Visser O, de Munck L, Elferink MAG, Westenend PJ, et al. The impact of the temporary suspension of national cancer screening programmes due to the COVID-19 epidemic on the diagnosis of breast and colorectal cancer in the Netherlands. J Hematol Oncol. 2020;13(1):147. doi: 10.1186/s13045-020-00984-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinkwin M, Silva L, Vogel I, Reeves N, Cornish J, Horwood J, et al. COVID-19 and the emergency presentation of colorectal cancer. Colorectal disease: the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Boyle JM, Kuryba A, Blake HA, Aggarwal A, van der Meulen J, Walker K, et al. The impact of the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer services in England and Wales: a national survey. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mizuno R, Ganeko R, Takeuchi G, Mimura K, Nakahara H, Hashimoto K, et al. The number of obstructive colorectal cancers in Japan has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic: a retrospective single-center cohort study. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2020;60:675–679. doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2020.11.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koczkodaj P, Sulkowska U, Kamiński MF, Didkowska J. SARS-CoV-2 as a new possible long-lasting determining factor impacting cancer death numbers. Based on the example of breast, colorectal and cervical cancer in Poland. Nowotwory. 2021;71(1):42–6.

- 22.Bhargava A, D'Ovidio V, Lucidi C, Bruno G, Lisi D, Miglioresi L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer screening program. Br J Surg. 2021;20(1):e5–e11. doi: 10.1016/j.clcc.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lantinga MA, Theunissen F, Ter Borg PCJ, Bruno MJ, Ouwendijk RJT, Siersema PD. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on gastrointestinal endoscopy in the Netherlands: analysis of a prospective endoscopy database. Endoscopy. 2021;53(2):166–170. doi: 10.1055/a-1272-3788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longcroft-Wheaton G, Tolfree N, Gangi A, Beable R, Bhandari P. Data from a large Western centre exploring the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on endoscopy services and cancer diagnosis. 2021;12(3):193–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Abdellatif M, Salama Y, Alhammali T, Eltweri AM. Impact of COVID-19 on colorectal cancer early diagnosis pathway: retrospective cohort study. Br J Surg. 2021;108(4):e146–e147. doi: 10.1093/bjs/znaa122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raj Kumar B, Pandey D. An observational study of the demographic and treatment changes in a tertiary colorectal cancer center during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020;122(7):1271–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Santoro GA, Grossi U, Murad-Regadas S, Nunoo-Mensah JW, Mellgren A, Di Tanna GL, et al. DElayed COloRectal cancer care during COVID-19 Pandemic (DECOR-19): Global perspective from an international survey. Surgery. 2021;169(4):796–807. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamposioras K, Lim KHJ, Saunders MP, Marti K, Anderson D, Cutting M, et al. The impact of changes in service delivery in patients with colorectal cancer during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Clinic Oncol. 2021;39(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Brunner M. Oncological colorectal surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic-a national survey. Br J Surg. 2020;35(12):2219–2225. doi: 10.1007/s00384-020-03697-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gurney JK, Millar E, Dunn A, Pirie R, Mako M, Manderson J, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer diagnosis and service access in New Zealand–a country pursuing COVID-19 elimination. The Lancet Regional Health - Western Pacific. 2021;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Lechner D, Tschann P, Girotti PCN, Königsrainer I. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on a visceral surgical department in western Austria. European Surgery - Acta Chirurgica Austriaca. 2021;53(2):43–47. doi: 10.1007/s10353-020-00683-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cui J, Li Z, An Q, Xiao G. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Elective Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. J Inflamm Res. 2021:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Byrne H, Chawla A, Gurung G, Hughes G, Rao M. Variations in colorectal cancer surgery practice across the United Kingdom during the COVID-19 pandemic – ‘every land has its own law’. The surgeon : journal of the Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Edinburgh and Ireland. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Allaix ME, Lo Secco G, Velluti F, De Paolis P, Arolfo S, Morino M. Colorectal surgery during the COVID-19 outbreak: do we need to change? Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas : organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Patologia Digestiva. 2021;73(1):173–177. doi: 10.1007/s13304-020-00947-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huddy JR, Crockett M, Nizar AS, Smith R, Malki M, Barber N, et al. Experiences of a “COVID protected” robotic surgical centre for colorectal and urological cancer in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Robot Surg. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.Merchant J, Lindsey I, James D, Symons N, Boyce S, Jones O, et al. Maintaining Standards in Colorectal Cancer Surgery During the Global Pandemic: A Cohort Study. World J Surg. 2021;45(3):655–661. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05928-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morris EJA, Goldacre R, Spata E, Mafham M, Finan PJ, Shelton J, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the detection and management of colorectal cancer in England: a population-based study. The lancet Gastroenterology & hepatology. 2021;6(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00005-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serban D, Socea B, Badiu CD, Tudor C, Balasescu SA, Dumitrescu D, et al. Acute surgical abdomen during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical and therapeutic challenges. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2021;21(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Tejedor P, Simó V, Arredondo J, López-Rojo I, Baixauli J, Jiménez LM, et al. The impact of SARS-CoV-2 infection on the surgical management of colorectal cancer: lessons learned from a multicenter study in Spain. Revista espanola de enfermedades digestivas : organo oficial de la Sociedad Espanola de Patologia Digestiva. 2021;113(2):85–91. doi: 10.17235/reed.2020.7460/2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tschann P, Girotti PNC, Lechner D, Adler S, Feurstein B, Szeverinski P, et al. How does the COVID-19 pandemic influence surgical case load and histological outcome for colorectal cancer? A single-centre experience. J Gastrointest Surg : Official J Soc Surg Alimentary Tract. 2021:1–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Xu Y, Huang ZH, Zheng CZ, Li C, Zhang YQ, Guo TA, et al. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on colorectal cancer patients: a single-center retrospective study. BMC Gastroenterol. 2021;21(1):185. doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01768-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baxter MA, Murphy J, Cameron D, Jordan J, Crearie C, Lilley C, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on systemic anticancer treatment delivery in Scotland. Gut. 2021;124(8):1353–1356. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01262-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Beypinar I, Urun M. Intravenous chemotherapy adherence of cancer patients in time of COVID-19 crisis. UHOD - Uluslararasi Hematoloji-Onkoloji Dergisi. 2020;30(3):133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sun L, Xu Y, Zhang T, Yang Y. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on adjuvant chemotherapy for patients with stage II or III colon cancer: experiences from a multicentre clinical trial in China. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont) 2020;27(3):159–162. doi: 10.3747/co.27.6529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He C, Li Y. How should colorectal surgeons practice during the COVID-19 epidemic? A retrospective single-centre analysis based on real-world data from China. 2020;90(7–8):1310–1315. doi: 10.1111/ans.16057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huddy JR, Freeman Z, Crockett M, Hadjievangelou N, Barber N, Gerrard D, et al. Establishing a "cold" elective unit for robotic colorectal and urological cancer surgery and regional vascular surgery following the initial COVID-19 surge. Colorectal disease: the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2020;107(11):e466–e467. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Singh HK, Patil V, Chaitanya G, Nair D. Preparedness of the cancer hospitals and changes in oncosurgical practices during COVID-19 pandemic in India: a cross-sectional study. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122(7):1276–1287. doi: 10.1002/jso.26174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearce L, Braude P, Vilches-Moraga A, Hewitt J, Carter B, London JW, et al. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer-related patient encounters. Colorectal disease: the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2020;4:657–665. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ferrara G, De Vincentiis L, Ambrosini-Spaltro A, Barbareschi M, Bertolini V, Contato E, et al. Cancer diagnostic delay in Northern and Central Italy during the 2020 lockdown due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Clin Pathol. 2021;155(1):64–68. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/aqaa177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Buscarini E, Benedetti A, Monica F, Pasquale L, Buttitta F, Cameletti M, et al. Changes in digestive cancer diagnosis during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in Italy: a nationwide survey. Digestive and liver disease: official journal of the Italian Society of Gastroenterology and the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Samani S, Mir N, Naumann DN. COVID-19 and endoscopic services: the impact of delays in therapeutic colonoscopies on patients. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Lo Secco G, Velluti F, De Paolis P, Arolfo S, Morino M, Kamposioras K, et al. The impact of changes in service delivery in patients with colorectal cancer during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Updates in surgery. 2020.

- 53.Rafiemanesh H, Mohammadian-Hafshejani A, Ghoncheh M, Sepehri Z, Shamlou R, Salehiniya H, et al. Incidence and mortality of colorectal cancer and relationships with the human development index across the world. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2016;17(5):2465–2473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alkatout I, Biebl M, Momenimovahed Z, Giovannucci E, Hadavandsiri F, Salehiniya H, et al. Has COVID-19 affected cancer screening programs? A systematic review. Front Oncol. 2021;11:675038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.De Felice F, Petrucciani N. Treatment approach in locally advanced rectal cancer during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic: long course or short course? Colorectal disease: the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland. 2020;22(6):642–643. doi: 10.1111/codi.15058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

NA.