Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused huge disruptions worldwide affecting most people including university students. The impact of the pandemic lockdown on pharmacy students’ stress levels and quality of life (QoL) is not well studied. This study assessed the impact of COVID-19 lockdown on perceived stress levels and QoL among final-year undergraduate pharmacy students at Ajman University, United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Methods

A cross-sectional electronic survey was conducted among final-year Bachelor of Pharmacy students at Ajman University during the COVID-19 lockdown period. The perceived stress scale and World Health Organization Quality of Life Instrument (WHOQOL-BREF) were administered through Google Forms. The filled responses were exported to IBM SPSS statistics, Version 26, scored as per the standard scoring procedures, and analyzed to answer the study objectives. Since the data were not distributed normally (p=0.000, Kolmogorov–Smirnov test), non-parametric tests (Mann–Whitney test and Kruskal–Wallis test) were performed to compare the median (IQR) scores with demographic parameters at an alpha value of 0.05.

Results

Of the eligible 94 students, 81 (male=16, 19.8%, female = 65, 80.2%) responded. The perceived stress level due to COVID-19 among the participants of a score of 24 suggests that the students suffered a “moderate” level of stress with no statistical significance between genders regardless of the place of residence in the seven Emirates (p=0.371) of the UAE. During the previous month of conducting the survey, 40.7% (n=33) of the respondents “very often” felt nervous and 22% (n=18) “fairly often” felt nervous with a median (IQR) score 3 (2–4); 3 denotes ‘sometimes’. Of the respondents, 6.2% (n=14) “very often” and 21% (n=17) “fairly often” felt that things were going their own way. Regarding the QoL statements, a median (IQR) score of 3 (3–4) was obtained for the question on “How much do you enjoy life?”, and the median scores were “4 (very much)” for more than half of the statements overall denoting a better QoL. The study reported females to have more physical pain, which may prevent them from carrying out their daily activities, than males (p=0.001) reflecting a better QoL among males over females during the lockdown. It also reflects a higher need for medications among females compared to males (p=0.014). All participants showed negative feelings, which is more apparent among male participants (4, 3–4.5) when compared to female participants (3, 2–3) (P = 0.001).

Conclusion

The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on perceived stress and self-reported QoL is minimum. Age, gender and other demographic factors had little or no effect on stress levels, but gender influenced “experience of physical pain” and “requirement for medications”, with more likelihood in females. Student friendly educational approaches and proper implementation of educational reforms can help minimizing student stress and improving QoL during vulnerable times like lockdowns.

Keywords: COVID-19, stress level, pharmacy, students, quality of life

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19), pandemic has affected everyone with no exception to university students. As of 21st of November 2021, there were 257,502,647 reported COVID-19 cases and 5,165,730 deaths.1 The COVID-19 outbreak was considered stressful among people, worldwide, which led to fear and anxiety.2,3 Healthcare members, in particular the frontline workers dealing with the pandemic, felt even more stress due to fear of catching the disease from patients, overwhelming number of admitted patients, shortage of personal protective equipment, etc.4 Many countries worldwide responded to this crisis quickly and implemented extreme measures such as complete lockdown and allocating more resources to handle the pandemic. Lockdowns caused more disruptions to the world, which was already reeling from the pandemic. Universities, in particular, face multiple challenges as they provide not just teaching, but often additional sanctuary to students.5 The first and foremost concern for higher education authorities during the crisis was to focus on the welfare and safety of the faculty, staff, and students.6 In the process, academic institutions had to shut down campuses and shift from traditional teaching/learning process to newly acquainted virtual/online modes. Universities adopted different types of digital virtual tools for their staff and students to perform their activities and assessments.7,8

Although these measures and efforts have yielded positive outcomes, isolating people at their home for a long time and closure of schools and universities might have had negative effects on students’ physical and mental health.9 Students are more vulnerable as they have lost access to their friends, their campus communities, and the structure and rhythm of the academic year. Many students might experience additional worries, including how to help their families financially and how to completely transition to online education, sometimes in regions with poor internet access. In addition to being worried about the disease and their families and loved ones being at risk, it is worth mentioning the stress of paying tuition fees due to parents’ job loss, business shutdowns, etc.10 Student plans changed drastically during the lockdown and cutoff of their peers and mentors. These factors collectively are expected to impact their QoL. Subsequently, recording the full impact of the pandemic on education is fundamental as it provides useful insights on existing problems and offers recommendations.11

Like other universities, as the COVID-19 situation continued to change rapidly, Ajman University (AU) moved the teaching and assessment processes to online considering students and staff’s health as its first priority and to limit the spread of COVID-19. Prior to the implementation of the lockdown period, the final-year undergraduate pharmacy students were undergoing experiential learning at hospitals and community pharmacies as part of the Spring-2020 academic semester. As the pandemic worsened, lockdown was implemented in the country, and students were forced to halt training and undergo virtual training sessions. The final-year students are considered especially vulnerable to stress and more worried due to the fact that they are graduating soon and looking for job options. Furthermore, there were doubts and uncertainties surrounding virtual sessions as they felt online sessions were inferior and not as strong as face-to-face sessions. They were also worried about their possible delay in pharmacist licensing and admission to higher studies, etc. All these negative factors posed by the lockdown collectively could have had a negative impact on the mental health wellbeing of the students. In such a situation, it would be important to study the negative impact of the lockdown on students’ stress levels and QoL, which could have been compromised. Hence, the present study was undertaken to assess the perceived stress and QoL among the final-year pharmacy students during COVID-19 lockdown and to correlate their stress levels and QoL with selected demographic variables of the student respondents.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

A cross-sectional, descriptive, electronically administered, questionnaire-based study assessing final-year students’ responses on their perceived stress and QoL due to COVID-19 lockdown.

Ethical Considerations

The Research Ethics Committee of Ajman University, Ajman, UAE approved this research, with the approval number P-H-F-2020-04-30. Written consent was obtained from the respondents electronically prior to administering the survey. Participants were informed about the purpose of the study and were given the option to either participate or not participate in the study. They were told participating in the study was solely a decision by the participants. Throughout the study, anonymity was maintained among the respondents, and all ethical principles laid down by the approving body were followed during the research.

Study Subjects

Final-year B. Pharm students of the Ajman University, who were registered for the Clinical Pharmacy and First Aid course, were undergoing the experiential learning until the implementation of lockdown. The final-year students, who were graduating soon and whose experiential learning in hospitals and community pharmacy, was converted to virtual sessions were most affected due to lockdown and hence were the focus population for the study. These students were also the ones entering jobs and higher studies, and hence it was considered crucial to assess their stress levels and QoL.

Study Timeline

This study was conducted between 26th April and 9th May, 2020, while the respondents were under COVID-19 lockdown for the past one month and were taking their didactic and experiential learning courses virtually. There were no course-related assessments scheduled to be conducted over the next two weeks of the study period in order to avoid potential bias.

Sample Selection

In this study, researchers approached 94 final-year students registered for Clinical Pharmacy and First Aid course. A purposive-non-probability sampling method was used wherein all the students would have an equal opportunity to respond to the survey.12 However, 81 out of 94 (86.1%) of them responded to the survey questionnaire.

Study Tools

The study tool of this research comprised of three parts: Part 1 consisted of demographic variables, such as gender, country of origin, the Emirate, they were currently living in within the UAE, age, and reasons for choosing pharmacy education, Part B consisted of perceived stress scale13 and Part III had WHOQOL-BREF.14 Both the questionnaires were administered in English with no translations involved. Since both the questionnaires are validated ones, the authors did not perform a pilot study. However, the internal consistency was assured by measuring the Cronbach's alpha after obtaining the responses from all the 81 respondents, and the alpha value was 0.83.

Perceived Stress Scale

This questionnaire was developed in 1983, and helps understand how different situations affect an individual’s perceived stress and feelings. It has a total of 10 5-point Likert-type questions and analyzes the feelings and thoughts (stress perceived) of the respondents during the past month. The responses on the scale vary from 0 to 4 and the total score ranges from 0 to 40 (the higher the scores, the higher the perceived stress). Items 4, 5, 7 and 8 on the scale are positively worded indicating reverse scoring. Scores ranging from 0 to 13 were considered “low stress”, 14–26 “moderate stress” and 27–40 “high stress”.13

WHOQOL-BREF Questionnaire

For assessing the students’ QoL, the WHO Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF) shorter version was chosen.14 This questionnaire consists of 26, 5-point Likert-type questions measuring four domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships and environmental health. Among these questions, one of them was related to “sexual satisfaction” and was deleted based on a consensus arrived at by the research team, thus making a total of 25 questions.

Method of Data Collection

The survey questionnaire was administered to final-year B. Pharm students through Google Forms, and students were given time to complete them electronically. The completed questionnaires were analyzed as per the study objectives.

Data Analysis

IBM SPSS statistics, Version 26 was used to analyze the data. The demographic characteristics were analyzed descriptively. The survey responses were checked for normality distribution using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and were found not to be distributed normally (p=0.000). The perceived stress level was assessed by calculating the median (IQR) scores of the individual statements, analyzing the individual statements with any existing association between demographic parameters and individual statement scores. The median (IQR) scores were calculated by scoring individual statements such as 0 = Never 1 = Almost Never 2 = Sometimes 3 = Fairly Often 4 = Very Often.

For the QoL, the first four questions were analyzed individually, and the statistical significances were performed using Mann Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests to test for dichotomous and variables with more than three responses, respectively. Questions 1–2 were broad and about overall satisfaction and overall health and hence presented separately rather than presenting with median (IQR) scores. Questions 3–4 were negatively scored one means “Not at all” is scored 5 and “an extreme amount” is scored 1. Hence, these two questions were presented separately rather than reverse scoring. The questions number 5 to 24 were analyzed together and presented in a separate table with median (IQR) scores of individual statements. The median (IQR) scores were calculated by scoring individual statements such as 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = 1 moderate amount, 4 = very much, 5 = an extreme amount. The statistical significance was tested at alpha = 0.05.

Results

Demographic Characteristics of the Student Respondents

A total number of 81 (male = 16, 19.8%, female = 65, 80.2%) 4th year undergraduate pharmacy students were involved in this study. Most participants were from Arab countries except three students (1 Indian, 1 Nigerian and 1 from the USA). The mean±SD age for all participants was 22.1 ±3.09 years. As the UAE is made up of seven Emirates, during the COVID-19 pandemic each Emirate had particular regulations and restrictions specific to that Emirate to control the spread of the virus. Participants were from all Emirates, which made their level of lockdown slightly different; Sharjah (n=34, 42%), Ajman (n=29, 35%), Dubai (n=7, 8.6%), Abu Dhabi (n=7, 8.6), Um-Al-Quwain (n=2, 2.5%), RAK (n=1, 1.2%), Fujairah (n=1, 1.2%). Only three of the female participants and none of the male participants were married.

In this study, 79% (n=65) of the participants willingly chose pharmacy as their study major, 11.1% (n=9) were forced by family to study pharmacy and 9.9% (n=8) was due to the influence of friends or seniors.

Students’ Perceived Stress Due to COVID-19

The perceived stress scale had 10 questions, which evaluated stress levels among 81 participants during the lockdown due to COVID-19; a summary of responses is provided in Table 1. During the last month, it seems that most students leaned towards very often 33 (40.7%) when they were asked about nervousness and stress level. The median score for the statement was 3 (2–4). Regarding feelings of anger, many participants choose fairly often and very often 37 (45.7%). The median of the total score of perceived stress level is 24 (22–27) with the curve positively skewed towards the higher level. The total score of 24 suggests the students suffered a “moderate” level of stress. There was no statistically significant difference between male 23 (20–26.75) and female 25 (22–28) participants when the median of stress perceived level was compared (P value: 0.067).

Table 1.

Perceived Stress Among Students Determined Using the Perceived Stress Scale*

| Questions | Never N (%) | Almost Never N (%) | Sometimes N (%) | Fairly Often N (%) | Very Often N (%) | Median (IQR) Score** |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly? | 1 (1.2%) | 6 (7.4%) | 38 (46.9%) | 21 (25.9%) | 15 (18.5%) | 2 (2–3) |

| 2. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life? | 0 | 6 (7.4%) | 40 (49.4%) | 16 (19.8%) | 19(23.5%) | 2 (2–3) |

| 3. In the last month, how often have you felt nervous and “stressed”? | 1 (1.2%) | 3 (3.7%) | 26 (32.1%) | 18 (22.2%) | 33(40.7%) | 3 (2–4) |

| 4. In the last month, how often have you felt confident about your ability to handle your personal problems? | 0 | 3 (3.7%) | 43 (53.1%) | 22 (27.2%) | 13 (16%) | 2 (2–3) |

| 5. In the last month, how often have you felt that things were going your way? | 1 (1.2%) | 9 (11.1%) | 49 (60.5%) | 17 (21%) | 14 (6.2%) | 2 (2–3) |

| 6. In the last month, how often have you found that you could not cope with all the things that you had to do? | 1 (1.2%) | 10 (12.3%) | 37 (45.7%) | 23 (25.9%) | 12 (14.8%) | 2 (2–3) |

| 7. In the last month, how often have you been able to control irritations in your life? | 1 (1.2%) | 8 (9.9%) | 43 (53.1%) | 20 (25.9%) | 8 (9.9%) | 2 (2–3) |

| 8. In the last month, how often have you felt that you were on top of things? | 4 (4.9%) | 15 (18.5%) | 38 (46.9%) | 18 (22.2%) | 6 (7.4%) | 2 (2–3) |

| 9. In the last month, how often have you been angered because of things that were outside of your control? | 2 (2.5%) | 10 (12.3%) | 32 (39.5%) | 15 (19.8%) | 21 (25.9%) | 2 (2–4) |

| 10. In the last month, how often have you felt difficulties were piling up so high that you could not overcome them? | 0 | 11 (13.6%) | 39 (48.1%) | 20 (25.9%) | 9 (12.3%) | 2 (2–3) |

Notes: **The median (IQR score) is calculated by scoring individual statements as stated in “Data analysis” section. The maximum possible score for a statement can be ‘4ʹ and minimum score can be ‘0ʹ. *The Perceived Stress Scale is reprinted with permission of the American Sociological Association from: Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):385–396.13 Journal of Health and Social Behavior © 1983 American Sociological Association.

Residing in different Emirates had no impact on the median of the total score, which shows no effect of location on stress level (P value 0.371): Dubai 22 (16–27), Abu Dhabi 23 (22–25), Sharjah 25 (20–27) and Ajman 25 (22–28). Even though there are differences in the reasons for studying pharmacy among participants, there is no statistically significant difference in the stress level among them (p value 0.943): Forced by family 25 (21–28), influence of friends or seniors 25.5 (22.25–27.75), own inclination 24 (22–27). This indicates that COVID-19 might be an independent factor of stress among all participants.

Quality of Life During COVID-19 Lockdown

Based on the participants' self-evaluation of their overall quality of life, most of them answered good and very good (46, 56.8% and 12, 14.8% respectively). Only 7.4% (n=6) chose poor quality of life during the lockdown, 21% (n=17) chose neither poor nor good during the COVID-19 period, while they were all studying virtually from home. The median for self-evaluated quality of life was 3–4 with a percentile of 25–75; female 2 (2–3) and male 2 (2–3.5); p=0.625.

As regard to health satisfaction, most participants were satisfied and very satisfied (49.4% (n=40) and 19.8% (n=16)). Only 1.2% (n=1) were very dissatisfied, 6.2% (n=5) were dissatisfied and 23.5% (n=19) were neither satisfied nor dissatisfied.

Most participants did not think that they had enough physical pain to prevent them from doing their daily activities; those who thought they had a moderate impact of pain were 34.6% (n=28), a little impact was 25.9% (n=21) and those who chose not at all were 17.3% (n=14). On the other hand, those who chose “physical pain could affect their daily activities very much” were 18.5% (n=15) and those with an extreme amount of pain, which stopped them from doing their activities were 3.7% (n=3). This study shows that females had more physical pain than males, which may prevent them from doing what they need to do (median = 3 (2–4) and median = 4 (4–5) respectively), P value = 0.001. When medical treatment was assessed, most participants chose moderate amount, little or not at all (24.7%) (n=20), 37% (n=30) and 34.6% (n=28) respectively. In regard to medication needed to carry out daily activities, a statistically significant difference between genders was noted (P value = 0.014). Table 2 shows different attitudes of the most common daily activities among participants during COVID-19 lockdown.

Table 2.

Student Responses on QoL Determined Using WHOQOL-BREF Questionnaire*

| QoL Statements | Median (IQR) Score** |

|---|---|

| How much do you enjoy life? | 3 (3–4) |

| To what extent do you feel your life to be meaningful? | 4 (3–4) |

| How well are you able to concentrate? | 3 (3–4) |

| How safe do you feel in your daily life? | 4 (3–4) |

| How healthy is your physical environment? | 3 (3–4) |

| Do you have enough energy for everyday life? | 3 (3–4) |

| Are you able to accept your bodily appearance? | 4 (3–5) |

| Have you enough money to meet your needs? | 4 (3–4) |

| How available to you is the information that you need in your day-to-day life? | 4 (3–4) |

| To what extent do you have the opportunity for leisure activities? | 3 (2–4) |

| How well are you able to get around? | 3 (3–4) |

| How satisfied are you with your sleep? | 3 (3–4) |

| How satisfied are you with your ability to perform your daily living activities? | 3 (3–4) |

| How satisfied are you with your capacity for work? | 3 (2–4) |

| How satisfied are you with yourself? | 4 (3–4) |

| How satisfied are you with your personal relationships? | 4 (3–4) |

| How satisfied are you with the support you get from your friends? | 4 (3–4) |

| How satisfied are you with the conditions of your living place? | 4 (3–4) |

| How satisfied are you with your access to health services? | 4 (3–4) |

| How satisfied are you with your transport? | 4 (3–4) |

Notes: **The median (IQR score) is calculated by scoring individual questions as stated in “Data analysis” section. The maximum possible score for a question can be ‘5ʹ and minimum score can be ‘1ʹ. *The WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire is reproduced with permission from: S[No authors listed]. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–558.14 © 1998 Cambridge University Press. WHO does not endorse any specific companies, products or services.

Gender had no impact on the total score of quality of life among all participants (P = 0.726). A similar observation was noticed with total score and other demographic characteristics.

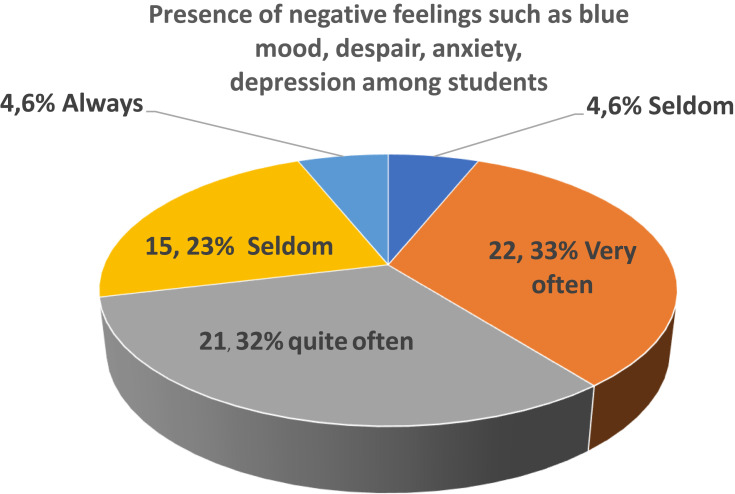

Presence of Negative Feelings Such as Blue Mood, Despair, Anxiety and Depression Among Students

Figure 1 shows the presence of negative feelings among student respondents. Further analysis showed negative feelings were more common among male participants (4, 3–4.5) when compared to female participants (3, 2–3) (P = 0.001).

Figure 1.

Presence of negative feeling among students during COVID-19 lockdown days.

Discussion

Stress is a common problem in everyone’s day-to-day life and the nature of stressors varies between individuals and their environments. The COVID-19 pandemic had further catalyzed the existing stress levels, as an outcome of health, economic and other indirect consequences, and did not spare anyone, including students.15,16 Stress, a causative factor for multiple health conditions, is also known to play a significant role in determining the QoL of an individual.17 This research is the first one to evaluate pharmacy students’ perceived stress and QoL during the COVID-19 lockdown. Pharmacy students surveyed under this research were the senior students preparing for the job market in the months to come and were unsure of the course of damages likely to be caused by COVID-19. High perceived stress among students can largely negatively influence their QoL, leading to poor learning experiences, lower examination performances and failure to achieve future goals. Generally, on occasions other the COVID-19 situation, stress in student life is related to examination, examination results, studying for exams, and too many tasks to be completed etc.18

In the current research, students reported a moderate level of stress at a time when they were not attending regular classes and were taking virtual sessions for both didactics and experiential trainings. The level of students’ stress reported in the current research is much lower than that reported among frontline health professionals involved in caring for COVID-19 patients, who had higher risk of mental disorders.19 This stress suggests a clear demarcation existing between actual practitioners and future practitioners. Though one would expect a high level of stress among these students considering the timing of the research, in reality that was not the case, the reason for that may be because of the support of the university and parents. Although current research reported slightly higher median scores for females, no statistically significant difference existed between genders, suggesting the existing level of stress being uniformly present between student genders. Of the previously reported studies examining pharmacy students stress, two reported females to have high stress levels,20,21 whereas the current one and three others found no gender variations.22–24 Not having a gender influence can be attributed to the fact that any factors that could potentially lead to stress are beyond gender or have uniformly affected both the genders.

The low stress level among senior pharmacy students reported in the current study could be attributed to the fact that the virtual education was well implemented and accepted by the students. The university had set up a student counseling center to help students to cope with stress related to COVID-19 and also implemented virtual learning in a student-centered and student-friendly manner. Both could have further contributed to a reduced stress level. Similarly, it can also be viewed that students lived with their parents during lockdown, which could have probably helped in adapting to the lockdown situations. This finding is supported by another study from China that recommended extended family and professional support for health professional students during the time of COVID-19.

At this point in time, it is worth examining the unique culture of UAE students compared to their counterparts in other countries, which could probably be the reason behind the surprising results noticed in this research. In Middle Eastern countries, students spend more time with family members and only a small percentage of them generally live in hostels. Staying with parents could thus lessen the negative impacts of lockdown considering the lockdown enabled them to spend more time with their family members. Family size in Middle Eastern countries is also generally bigger, and a circumstance like COVID-19 lockdown although it limited them to meeting friends, provided them with more time and opportunity to interact with family members, thus defeating loneliness. Most of the student respondents in this research are foreign nationals whose parents were employed or running a business in the country giving students an opportunity to stay with them. The university support is also important as students can reach out to their faculty mentors anytime during the day using emails, phone calls and even social media.

An attempt was made to study the possible influence of place of residence in attributing to stress level, as all seven Emirates in the UAE had different time durations and levels of lockdown implemented. For instance, Dubai and Abu Dhabi had a stricter lockdown compared to other Emirates. However, the findings showed no significant difference between the place and the perceived stress level. While the location was assessed, this research did not assess the living arrangements of the students, as living arrangements (students living independently versus those living at home) could be a contributing factor to stress.26

COVID-19 had caused multiple problems including travel, meeting friends, and recreation facilities, such as movies and thus undoubtedly affecting the QoL of most people, if not everyone’s. In the wake of the current pandemic, healthcare students in some countries were asked to graduate and serve the community as health professionals without any delay, thus making them more stressed.27,28 However, such a decision was not taken in the UAE.

In the present study, the senior pharmacy students, who were nearing graduation and taking the final part of their academic courses, had good self-reported QoL. In a previous study from the US, 3rd-year PharmD students had a low health-related QoL.21 However, the impact posed by COVID-19 is not well assessable in the current study as there were no comparisons available in the same or nearly same population. The findings from the current research imply that QoL was not affected much due to the COVID-19, which could be due to the students living with their parents at home. Similar to stress levels reported in the current research, the QoL was also better among the students, which further reiterates the proactiveness of the university and college in handling the teaching learning processes at the time of pandemic.

In a previous study from Thailand among pharmacy students, the QoL was significantly impacted by factors, such as the number of siblings and factors related to study, such as the year and accommodation type.29 On the contrary, the current study reported no influence of gender or other demographic parameters on the students’ QoL.

It was noticed that females had more physical pain than males as reflected with a high median score for the QoL statement on physical pain in the WHOQOL-BREF. This had the potential to prevent them from doing what they needed to do, and could have a negative impact on their studies. In the current research, as regard to medication needed for daily activities, a gender gap was noted with females requiring more medications. Again, the nature of medicines used was not studied. In a broader preview of student responses, students had better QoL on various aspects, such as “enjoyment in life”, “meaningfulness of life”, “ability to concentrate”, “feeling of safety”, “physical environment”, “energy for everyday life”, “bodily appearance”, and so on, assessed using the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire (Table 2). Further assessments revealed students had experiences of blue mood, despair, anxiety and depression during the lockdown days, and those negative feelings were more common among male participants when compared to female participants, an observation requiring further introspection.

The study had few limitations. This survey was conducted only among senior pharmacy students considering that this student group is more vulnerable to stress and impaired QoL. However, involving more students, preferably across various study programs from more universities could have provided more insights. Moreover, the researchers were also course instructors for the respondent students who could have possibly had a potential bias in the nature of the responses. This study is a cross-sectional study, and a pre-post study or a study comparing students from different pharmacy schools could have provided more insights on the actual impact of lockdown in terms of perceived students stress and QoL.

The research findings had few potential implications. Similar studies can be done to explore the stress levels and QoL among students during other stressful situations, such as examinations, failures in academic progression and so on. The findings also provide an opportunity to identify vulnerable student groups and offer counselling services. Similar studies conducted at regular intervals can be valuable in measuring the long-term impact of COVID-19 on students’ stress levels and QoL.

Conclusions

Though the COVID-19 lockdown impaired students’ normal living, its impact on their perceived stress and self-reported QoL is minimum. Age, gender and other demographic factors studied had little or no effect on stress levels, but gender had an influence on “experience of physical pain” and “requirement for medications”, with more likelihood in females. On the contrary, negative feelings were more common among male students. The research findings can be used by other academic institutions in handling any future situations like COVID-19 lockdowns. Future research can be conducted to identify vulnerable student populations and provide more counseling and social support. Smooth implementation of online educations, flexible academic approaches, ease of approachability of faculty mentors, better student orientation and offering social support to students are proven valuable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge all the students for spending their valuable time in filling the questionnaires. A special thanks to Yassin Alhariri, Lecturer, Department of Clinical Sciences College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences, Ajman University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates for the help in filling the Ethical approval form. The authors would also like to acknowledge Claire Caroline Strauch, UK, for proof-reading the revised version of the manuscript. The authors would like to thank Ajman University for providing a 50% article processing fee for this manuscript.

Funding Statement

There is no funding to report.

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in this work nor associated with this manuscript and advise that financial disclosures are not applicable.

References

- 1.Worldometer. Available from: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/. Accessed November 21, 2021.

- 2.Singh P, Singh S, Sohal M, Dwivedi YK, Kahlon KS, Sawhney RS. Psychological fear and anxiety caused by COVID-19: insights from Twitter analytics. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102280. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Loan LT, Doanh DC, Thang HN, Viet Nga NT, Van PT, Hoa PT. Entrepreneurial behaviour: the effects of fear and anxiety of Covid-19 and business opportunity recognition. Entrepren Bus Econ Rev. 2021;9(3):7–23. doi: 10.15678/EBER.2021.090301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Env Res Pub. 2020;17(5):1729. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gill J. Coronavirus: a message to our global community. Available from: https://timeshighereducation.com/coronavirus-message-our-global-community. Accessed April 4, 2021.

- 6.Fernandez AA, Shaw GP. Academic leadership in a time of crisis: the Coronavirus and COVID‐19. J Leadersh Stud. 2020;14(1):39–45. doi: 10.1002/jls.21684 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhawan S. Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J Educ Technol Syst. 2020;49(1):5–22. doi: 10.1177/0047239520934018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ting DS, Carin L, Dzau V, Wong TY. Digital technology and COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26(4):459–461. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0824-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang Y, Di Y, Ye J, Wei W. Study on the public psychological states and its related factors during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in some regions of China. Psychol Health Med. 2020;26:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall R. Covid-19 and the hopeless university at the end of the end of history. Postdigit Sci Educ. 2020;2:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose S. Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(21):2131–2132. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.5227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galloway A. Non-probability sampling. Encyclopedia of social measurement. Kimberly Kempf-Leonard. 2005;2:859–864. doi: 10.1016/B0-12-369398-5/00382-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. JHSB. 1983;24:386–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.[No authors listed]. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–558. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res. 2020;287:112934. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang L, Rong Liu H. Emotional responses and coping strategies of nurses and nursing college students during COVID-19 outbreak. MedRxiv. 2020;1–17. doi: 10.1101/2020.03.05.20031898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ribeiro ÍJ, Pereira R, Freire IV, de Oliveira BG, Casotti CA, Boery EN. Stress and quality of life among university students: a systematic literature review. Health Prof Educ. 2018;4(2):70–77. doi: 10.1016/j.hpe.2017.03.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abouserie R. Sources and levels of stress in relation to locus of control and self-esteem in university students. J Educ Psychol. 1994;14(3):323–330. doi: 10.1080/0144341940140306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netwk Open. 2020;3(3):e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupchup G, Borrego M, Konduri N. The impact of student life stress on health-related quality of life among doctor of pharmacy students. Coll Stud J. 2004;38(2):292–302. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marshall LL, Allison AA, Nykamp D, Lanke S. Perceived stress and quality of life among doctor of pharmacy students. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008;72(6):137. doi: 10.5688/aj7206137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Axon DR, Hernandez C, Lee J, Slack M. An exploratory study of student pharmacists’ self-reported pain, management strategies, outcomes, and implications for pharmacy education. Pharmacy. 2018;6(1):11. doi: 10.3390/pharmacy6010011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landow MV. Stress and Mental Health of College Students. Nova Science Publishers; 2006:1–28. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the imposter phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):456–464. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00234.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Y, Wang Y, Jiang J, et al. Psychological distress among health professional students during the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychol Med. 2020;51:1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bal IA, Arslan O, Budhrani K, Mao Z, Novak K, Muljana PS. The balance of roles: graduate student perspectives during the COVID-19 pandemic. TechTrends. 2020;64(6):796–798. doi: 10.1007/s11528-020-00534-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.An option to serve in COVID-19 fight. Available from: https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/03/med-students-offered-early-degree-option-to-help-in-covid-19-fight/. Accessed April 4, 2021.

- 28.Medical students graduates fight coronavirus COVID 19. Available from: https://theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/20/final-year-medical-students-graduate-early-fight-coronavirus-covid-19. Accessed April 4, 2021.

- 29.Narakornwit W, Pongmesa T, Srisuwan C, Srimai N, Pinphet P, Sakdikul S. Quality of life and student life satisfaction among undergraduate pharmacy students at a public university in Central Thailand. Science, Engineering and Health Studies. 2019;13(1):8–19. doi: 10.14456/sehs.2019.2 [DOI]