SUMMARY

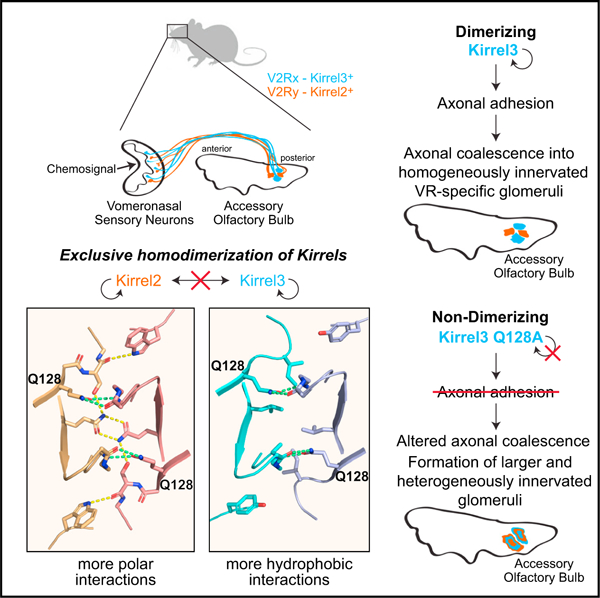

Projections from sensory neurons of olfactory systems coalesce into glomeruli in the brain. The Kirrel receptors are believed to homodimerize via their ectodomains and help separate sensory neuron axons into Kirrel2- or Kirrel3-expressing glomeruli. Here, we present the crystal structures of homodimeric Kirrel receptors and show that the closely related Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 have evolved specific sets of polar and hydrophobic interactions, respectively, disallowing heterodimerization while preserving homodimerization, likely resulting in proper segregation and coalescence of Kirrel-expressing axons into glomeruli. We show that the dimerization interface at the N-terminal immunoglobulin (IG) domains is necessary and sufficient to create homodimers and fail to find evidence for a secondary interaction site in Kirrel ectodomains. Furthermore, we show that abolishing dimerization of Kirrel3 in vivo leads to improper formation of glomeruli in the mouse accessory olfactory bulb as observed in Kirrel3−/− animals. Our results provide evidence for Kirrel3 homodimerization controlling axonal coalescence.

Graphical abstract

In brief

Neuronal surface receptors Kirrels are important for vomeronasal sensory neuron axon identity and coalescence in the brain. Wang et al. report structural and evolutionary origins of exclusive homodimerization of Kirrels. Mice expressing monomeric Kirrel3 show axon coalescence phenotypes, supporting the hypothesis that Kirrel homodimerization underlies axonal coalescence in these neurons.

INTRODUCTION

In the vertebrate olfactory system, olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) expressing the same olfactory receptor project their axons to a limited set of glomeruli in the olfactory bulb (OB), which allows for the creation of a topographic odor map in the OB (Mombaerts et al., 1996). In the mouse olfactory system, each OSN expresses a single olfactory receptor, which drives the expression of a limited number of cell surface receptors (Serizawa et al., 2006). Specifically, the expression of the cell adhesion receptors Kirrel2 or Kirrel3 in OSN populations is dependent on the odorant-induced and spontaneous activity of the olfactory receptors, and their expression patterns are mostly complementary; Kirrel2-expressing OSNs and Kirrel3-expressing OSNs segregate into separate glomeruli (Nakashima et al., 2019; Serizawa et al., 2006).

The accessory olfactory system, which is found in most terrestrial vertebrate lineages and is responsible for the detection of chemosignals that guide social behavior, has a similar structure (Brignall and Cloutier, 2015; Dulac and Torello, 2003), where vomeronasal sensory neurons (VSNs) expressing the same vomeronasal receptor project their axons into a specific set of 6 to 30 glomeruli in the accessory olfactory bulb (AOB) (Belluscio et al., 1999; Del Punta et al., 2002; Rodriguez et al., 1999). The coalescence of VSN axons into glomeruli is also shown to be dependent on Kirrel expression, where loss of VSN activity evoked by chemosignals reduces Kirrel2 expression and increases Kirrel3 expression (Prince et al., 2013). All VSNs expressing a given vomeronasal receptor express similar levels of these two Kirrels. While the two Kirrel paralogs show strong, complementary expression patterns in some VSN axon populations innervating glomeruli of the AOB, other VSNs express both Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 at varying levels (Prince et al., 2013). Ablation of Kirrel2 or Kirrel3 expression in mice leads to improper coalescence of VSN axons, resulting in fewer and larger glomeruli being formed in the posterior region of the AOB, while double knockout mice no longer have recognizable glomeruli (Brignall et al., 2018; Prince et al., 2013).

Members of the Kirrel (Neph) family of cell surface receptors were first identified in fruit flies for controlling axonal pathfinding in the optic chiasm and programmed cell death in retinal cells (Ramos et al., 1993; Wolff and Ready, 1991). These molecules have also been recognized for their role in myoblast function during muscle development and their involvement in building the blood filtration barrier in glomeruli in kidneys (Donoviel et al., 2001; Ruiz-Gómez et al., 2000). The Caenorhabditis elegans homolog SYG-1 has been demonstrated to specify targeting of synapses (Shen and Bargmann, 2003). Outside its function in the olfactory system, mammalian Kirrel3 has been shown to be a synaptic adhesion molecule necessary for the formation of a group of synapses in the hippocampus (Martin et al., 2015; Taylor et al., 2020) and is associated with autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability (Bhalla et al., 2008; De Rubeis et al., 2014; Taylor et al., 2020).

Here, we investigate the molecular basis of Kirrel2- and Kirrel3-mediated glomerulus formation in the AOB. We present the three-dimensional structures of Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 in homodimeric complexes that reveal why Kirrels do not heterodimerize, allowing for proper adhesion and segregation of subsets of sensory axons. We engineer mutations that perturb the homophilic interactions and abolish dimerization and Kirrel-mediated cell adhesion. Finally, we introduce a non-homodimerizing amino acid substitution into the mouse Kirrel3 allele, which leads to alterations in the wiring of the accessory olfactory system that phenocopy defects observed in Kirrel3−/− animals. These results indicate that Kirrel3 function in the control of glomeruli formation depends on ectodomain interactions mediated by Kirrel homodimerization via its first immunoglobulin domain.

RESULTS

Structural characterization of Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 D1 homodimers

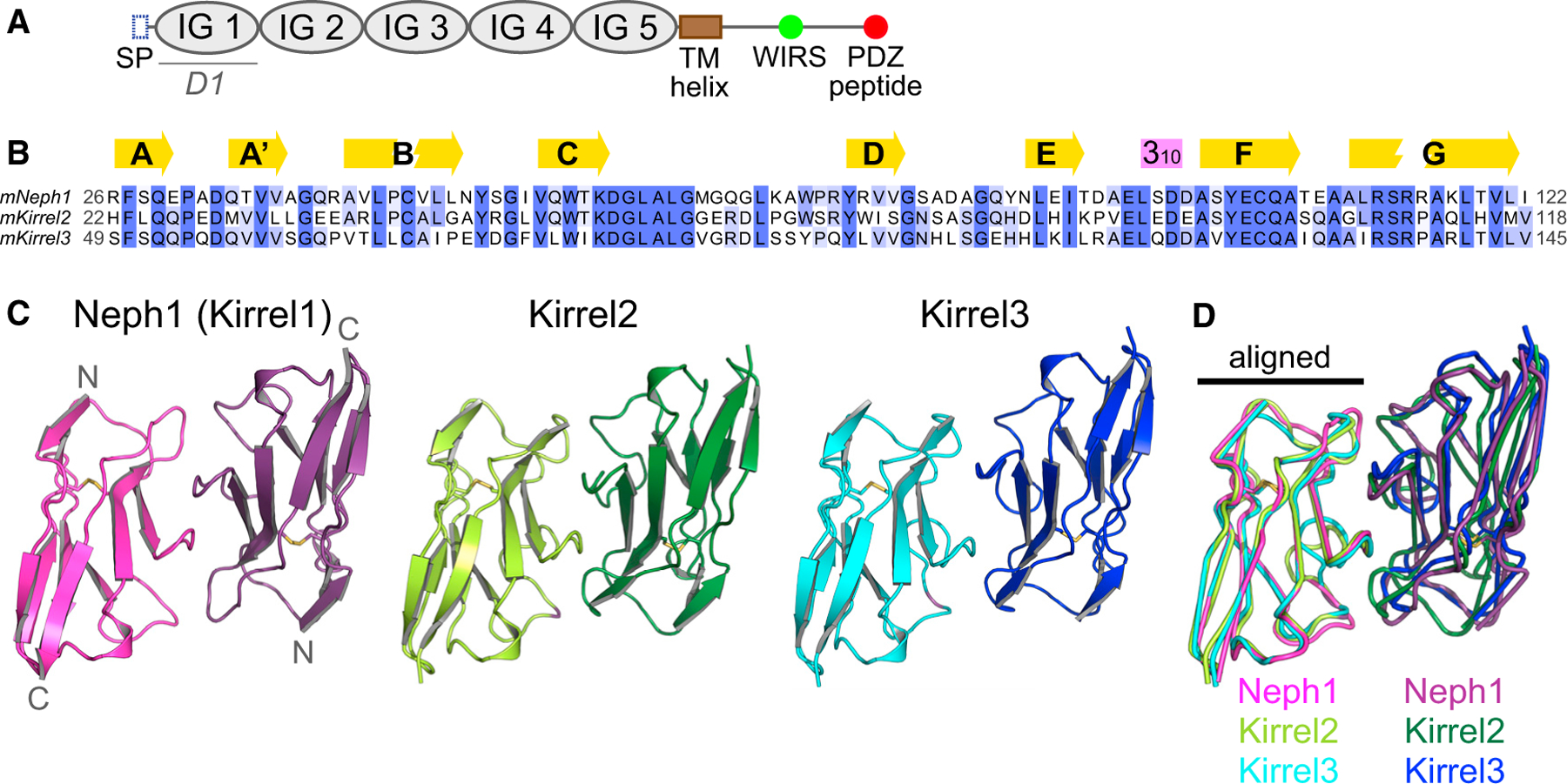

It has been proposed that Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 regulate the coalescence of OSNs and VSNs into glomeruli by homophilic adhesion through their ectodomains (Prince et al., 2013; Serizawa et al., 2006). Vertebrate Kirrel proteins have been shown to form homodimers but not heterodimers (Gerke et al., 2005; Serizawa et al., 2006), which may be important for axonal segregation into distinct glomeruli. Previously, we determined the crystal structure of mouse Kirrel1 (also known as Neph1) at 4-Å resolution covering the first two immunoglobulin domains and showed that homodimerization occurs by an interaction between the first domains (D1) of each monomer (Özkan et al., 2014). Due to limited resolution, however, the Kirrel1 electron density was missing for most side chains, and details of the interaction interface could not be documented. Vertebrate Kirrels are remarkably similar in their extracellular regions, containing five immunoglobulin domains (Figure 1A) with sequence identities of 53 to 56% for D1 among the three mouse Kirrels (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. The three mouse Kirrel D1 homodimers share gross structural features.

(A) The conserved domain structure of Kirrels. SP, signal peptide (N-terminal); TM, transmembrane; WIRS, WAVE regulatory complex-interacting receptor sequence.

(B) A multisequence alignment of the mouse Kirrel D1 domains. Secondary structure elements, β strands (yellow arrows), and a 310 helix (purple box) are shown above the alignment.

(C) The three mKirrel D1 dimers shown in cartoon representation. Neph1 (Kirrel1) homodimer structure is from Özkan et al. (2014) (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 4OFD). See Table S1 for structure determination statistics for Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 structures.

(D) The three mKirrel D1 homodimers are overlayed by aligning the chains shown on the left. Comparisons to structures of fly and worm Kirrel orthologs are provided in Figure S1.

To explain the molecular basis of homophilic interactions in the absence of heterophilic binding between the Kirrel paralogs, we determined the crystal structures of Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 D1 homodimers at 1.8-Å and 2.1-Å resolution, respectively (Figure 1C; Table S1). When superimposed, the Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 D1 domains have root mean square displacements (RMSD) of 1.2 Å to the Kirrel1 D1 domain and align with an RMSD of 1.0 Å to each other (all Cα atoms). Comparison of the three Kirrel D1 homodimers showed that Kirrels dimerize using the same interface, and the dimeric architectures are shared (Figure 1D). The three D1 homodimers align with RMSD values of 1.3 to 1.6 Å. Similar dimers have been observed for homodimeric complexes formed by fruit fly Kirrel homologs, Rst and Kirre (Duf), and the heterodimeric SYG-1-SYG-2 complex, the C. elegans Kirrel homolog bound to nephrin-like SYG-2 (Figure S1) (Özkan et al., 2014). This distinctive interaction architecture uses the curved CFG face of the immunoglobulin (IG) fold to create dimers and was recently identified to be common to a group of cell surface receptors involved in neuronal wiring, including Dprs, DIPs, IGLONs, nectins, and SynCAMs as well as Kirrels and nephrins (Cheng et al., 2019).

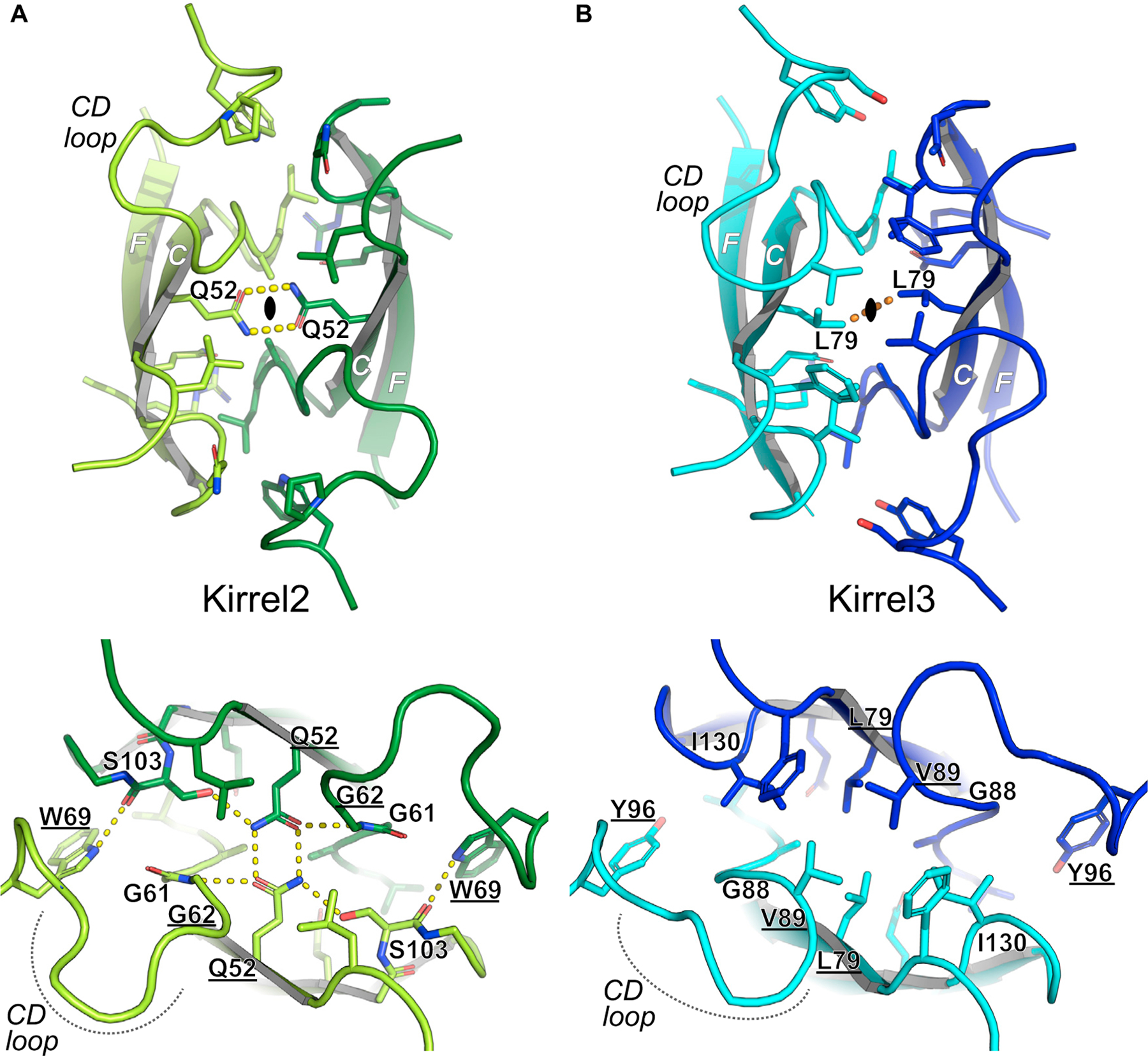

Out of 21 amino acids found in three structures to be at the dimer interface, ten are invariable among the three mouse Kirrels, mostly in the region following the C strand within the sequence KDGLALG and the F and G strands. The conserved Q128 (Kirrel3 numbering) in the F strand makes hydrogen bonds to the main chain of the conserved stretch in the CD loop in all three Kirrel structures (Figure S2). Beyond this similarity, there are stark differences in the Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 interfaces that likely underlie exclusive homodimerization. Kirrel2 has a hydrogen bonding network at the core of the interface, centered at Q52 at the two-fold symmetry axis (Figure 2A), while the hydrogen bonding network is missing in Kirrel3, which has L79 at the symmetry axis instead (Figure 2B). The polar versus hydrophobic interactions at the Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 interfaces, respectively, would preclude heterodimerization of the two Kirrels.

Figure 2. Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 have incompatible chemistries at their dimerization interfaces.

(A) Kirrel2 homodimerization interface. The closed oval represents the two-fold symmetry axis surrounded by the bidentate hydrogen bonding (yellow dashes) of two Q52 residues from Kirrel3 monomers. The interface includes an extensive set of hydrogen bonds.

(B) Kirrel3 homodimerization interface. None of the hydrogen bonds depicted in (A) are present in the Kirrel3 interface. The hydrogen bonds between the Q52 side chains at the Kirrel2 dimer symmetry axis are replaced by van der Waals contacts between the L69 side chains (orange dashes) in Kirrel3. The loop connecting the C and D strands are significantly different between the two Kirrel structures. The parts of the interface with conserved hydrogen bonding between Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 are shown in Figure S2. Underlined amino acids vary among ancestral vertebrate sequences (see Figure 3C) and are strong candidates to be specificity determinants.

Evolutionary origins of vertebrate Kirrels and homodimeric specificity

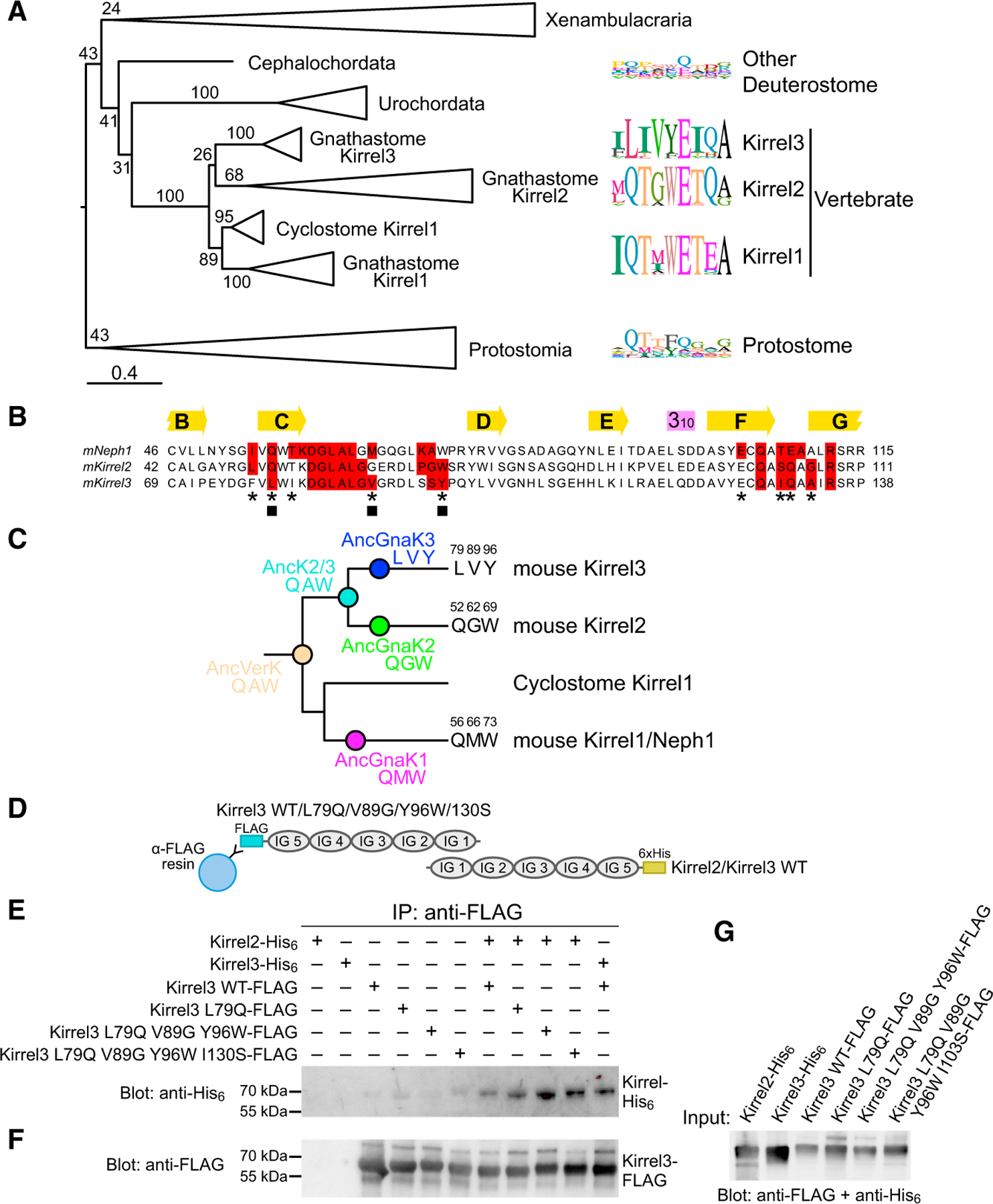

To understand how Kirrel homodimeric specificities arose in vertebrates, we next analyzed the evolutionary histories of Kirrels. All major bilaterian taxa contain Kirrel homologs, which preserve the five-IG domain extracellular region and a cytoplasmic PDZ peptide. We created a maximum likelihood (ML) phylogeny for Kirrels using a multiple sequence alignment of 90 ectodomains (Figure 3A; Data S1). The three vertebrate Kirrels arose as a result of gene duplications and are more closely related to each other than to invertebrate Kirrels. Kirrel duplication in invertebrates is rare, with one notable exception being Drosophila, which has two Kirrels (Rst and Kirre). After gene duplications within vertebrates, there have been several gene losses; this, combined with extensive sequence divergence between vertebrate and invertebrate Kirrels makes it difficult to accurately reconstruct the branching order of vertebrate Kirrels. Nevertheless, we observe strong bootstrap values for cyclostome Kirrel1 forming a single clade with gnathostome Kirrel1 and excluding Kirrel2 and Kirrel3. This strongly implies that Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 arose from a gene duplication within gnathostomes and are more closely related to each other than to Kirrel1 in support of our ML tree.

Figure 3. Phylogenetic analysis of Kirrels.

(A) Maximum likelihood tree for Kirrels. The scale bar below represents 0.4 substitutions per site. Numbers on the tree are bootstrap values supporting the adjacent node. The sequence logos to the right show the prevalence of amino acids in selected positions at the Kirrel dimerization interface for specific taxa, placed next to their branch in the phylogenetic tree. Sequence logos were calculated using 26 vertebrate Kirrel1 sequences, 17 vertebrate Kirrel2 sequences, 22 vertebrate Kirrel3 sequences, 8 other deuterostome sequences, and 17 protostome sequences. See Figure S3 for the uncollapsed tree with bootstrap support values.

(B) Sequence alignment showing all amino acids at the interface; red boxes, 4-Å cutoff used for identifying an interface amino acid. The selected residues used in sequence logos in (A) are marked with an asterisk below. Three positions at the interface that vary among ancestral sequences highlighted in (C) are labeled by closed squares.

(C) The three varying residues among sequence reconstructions of the three ancestral gnathostome Kirrels, the Kirrel2/Kirrel3 ancestor, and the ancestral vertebrate Kirrel are shown on the tree. These positions are underlined in the structural views of the interface in Figure 2. See Figure S3 for complete sequences of inferred ancestral D1 domains.

(D) Schematic for the co-immunoprecipitation assay performed between Kirrel2/Kirrel3 wild-type proteins and Kirrel3 wild-type/specificity mutant proteins. FLAG, FLAG-tag; 6×His, hexahistidine tag. WT, wild-type.

(E) FLAG-tagged wild-type and mutant Kirrel3 ectodomains were used to immunoprecipitate hexahistidine-tagged wild-type Kirrel2 or Kirrel3 ectodomains. Only very low levels of wild-type Kirrel2-His6 can be pulled down with wild-type Kirrel3-FLAG; the pull-down becomes increasingly efficient with the Kirrel3 L79Q mutation and the triple and quadruple mutations. For quantitation of the bands in triplicate, see Figure S3C.

(F) The anti-FLAG blot of the samples eluted with FLAG peptide show similar levels of Kirrel3-FLAG captured on anti-FLAG resin in all samples where Kirrel3 FLAG (wild-type or mutant) were included.

(G) The expression levels of His6- and FLAG-tagged Kirrels observed with anti-FLAG and anti-His6 antibodies.

To understand the evolution of Kirrel interaction specificity, we mapped variable interface residues in separate Kirrel clades (Figures 3A and 3B). The sequence logos show that Kirrel1 and Kirrel2 are more similar at their dimerization interfaces, while Kirrel3 diverged and mutated key positions to non-polar amino acids. Surprisingly, much of the variability observed at these positions in vertebrate Kirrels is also seen in invertebrate Kirrels, suggesting that these sites are permissive for multiple modes and specificities of binding.

Next, we inferred ancestral sequences for Kirrel D1 domains in the vertebrate and gnathostome nodes on the phylogenetic tree (Figure 3C; Figure S3). There are nine variable positions between the common Kirrel2/Kirrel3 ancestor and the ancestral gnathostome Kirrel3. Three of these positions are at the interface (labeled with closed squares in Figure 3B), including two that are part of the hydrogen-bonding network seen in Kirrel2 (Q52 and W69) and one that contributes strongly to the hydrophobic nature of the Kirrel3 interface (V89 in Kirrel3, G62 in Kirrel2) (see underlined amino acids in structures in Figure 2). Overall, these ancestral sequences support our structural observations that the gnathostome Kirrel3 homodimer interface gained non-polar interactions, which resulted in loss of interactions with its Kirrel2 paralogs.

To confirm that these residues we identified through the structural and phylogenetic analyses contribute to dimerization specificity, we tested for the co-immunoprecipitation of wild-type Kirrel2 with mutants of Kirrel3, converting the nonpolar ‘‘specificity’’ residues to their corresponding amino acids in Kirrel2 (Figure 3D). For mutating Kirrel3, we selected the three previously identified residues (L79, V89, and Y96) as well as I130, which in Kirrel2 corresponds to S103 and supports the hydrogen bonding network at the homodimerization interface (Figure 2). We observed that Kirrel2 was pulled down by the single (L79Q), triple (L79Q, V89G, and Y96W), and quadruple (L79Q, V89G, Y96W, and I130S) mutants of Kirrel3 (Figures 3E–3G; Figure S3C), indicating that converting the hydrophobic specificity layer in Kirrel3 to polar, hydrogen-bonding residues likely allows for interactions with Kirrel2.

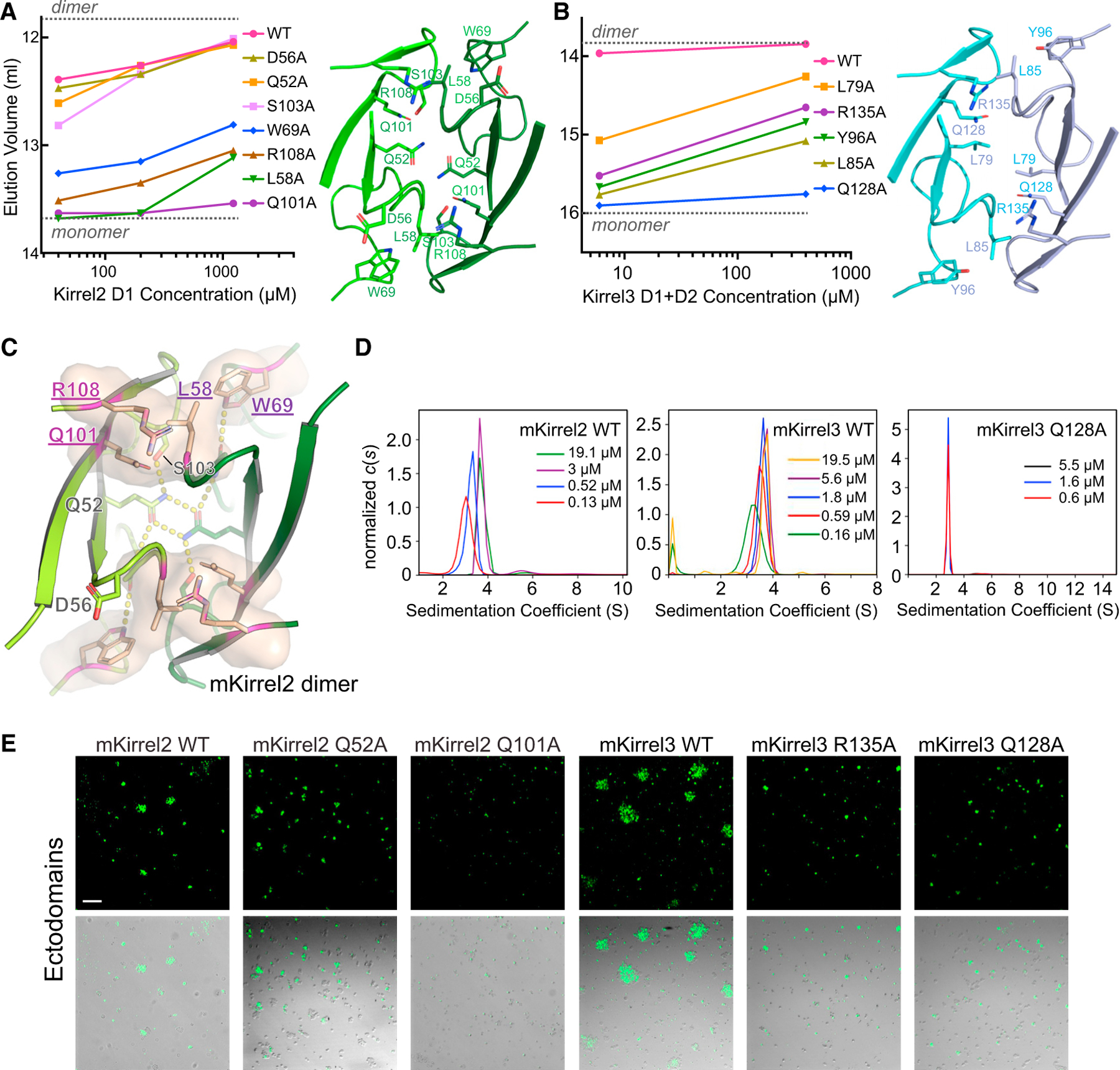

Mutagenesis of the Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 D1 dimerization interfaces

To confirm that the Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 D1 interfaces observed in crystal structures mediate dimerization in solution, we set out to mutate these interfaces and test for loss of dimer formation. In size exclusion chromatography (SEC) experiments, Kirrel2 D1 and Kirrel3 D1+D2 proteins eluted at a volume that roughly corresponds to that of their dimeric sizes (Figures 4A and 4B; Figures S4A–S4F). This dimerization is concentration specific; size exclusion runs with diluted samples eluting at later volumes, indicating a fast equilibrium between dimeric and monomeric forms of Kirrels. Interface mutations of mouse Kirrel2 D1 and Kirrel3 D1+D2 were tested for dimerization at various concentrations based on SEC elution volumes, which allowed us to rank these mutations for their effect to decrease or abolish dimer formation. For both Kirrel2 and Kirrel3, mutation of the same site, Q101 for Kirrel2 and Q128 for Kirrel3, to alanine abolished dimerization (Figures 4A and 4B). Alanine mutations of a set of equivalent positions at the dimerization interface of both Kirrels strongly diminished homodimerization: L58/L85, W69/Y96, and R108/R135 (Kirrel2/Kirrel3 numbering). The energetic hotspot formed by these four residues creates a continuous volume (Figure 4C). Surprisingly, the residue at the dimerization two-fold axis, Q52 for Kirrel2 and L79 for Kirrel3, which we have demonstrated to play a role in specificity, is less crucial for binding energetics. In fact, the variable residues necessary for establishing dimerization specificity appear to cause smaller losses of binding energy when mutated than the conserved residues at the hotspot. Overall, these mutagenesis experiments confirm that the interfaces observed in the crystal structures mediate dimer formation in solution.

Figure 4. Mutational analysis of the Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 homodimerization interfaces.

(A and B) SEC elution volumes for wild-type and mutant Kirrel2 D1 (A) and Kirrel3 D1+D2 (B) loaded at multiple concentrations on the columns. A Superdex 75 10/300 column was used for the Kirrel2 D1 runs (left), and a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column was used for the Kirrel3 D1+D2 runs, both with a column volume of 24 ml. Expected monomeric and dimeric elution volumes are marked by dashed lines on the plots. See Figure S4 for SEC chromatograms. The structural views to the right show the locations of the amino acids mutated.

(C) Four residues observed to be energetically important for Kirrel dimerization mapped onto Kirrel2 structure and shown as a surface (residue names purple and underlined).

(D) Sedimentation velocity results for mouse Kirrel2 wild-type (left), Kirrel3 wild-type (middle), and Kirrel3 Q128A (right) ectodomains performed at several initial protein concentrations showing lack of dimerization for the Q128A mutant. The dissociation constant (KD) for wild-type mKirrel2 and mKirrel3 refine to 0.9 μM (0.2 μM, 3.5 μM) and 0.21 μM (0.11 μM, 0.36 μM) (68.3% confidence intervals are shown in brackets). See Figures S4G and S4H for isotherms and fitting for dissociation constants.

(E) Cell aggregation assay for Kirrel2 and Kirrel3, wild type and mutants, fused to intracellular GFP, performed with S2 cells; scale bar, 100 μm.

Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 homophilic adhesion is dependent on D1

While we have shown that the major dimerization interface for Kirrel homologs is within the N-terminal domain (D1) (Özkan et al., 2014, and above), it is not known if the other four domains can also cause dimerization in vertebrate Kirrels. In support of additional dimerization sites, Gerke et al. (2003) reported evidence that dimerization was not limited to any single domain within Kirrel1 and the related nephrin. Furthermore, many human mutations affecting Kirrel3 function in the ectodomain, but outside D1, have been identified (summarized in Taylor et al., 2020). To test whether Kirrel ectodomains can form dimers using interfaces that we did not identify in our crystal structures, we used analytical ultracentrifugation to quantify dimerization of Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 ectodomains and one D1 interface mutant, Kirrel3 Q128A. We performed sedimentation velocity experiments at several concentrations and observed that both wild-type Kirrel ectodomains exist in a monomer-to-dimer equilibrium, confirming our SEC results (Figure 4D; Figures S4G and S4H). The Kirrel3 ectodomain with the D1 mutation Q128A showed no signs of dimerization at any concentration (Figure 4D), implying that no additional interface mediates dimerization.

Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 have been shown to mediate homophilic cell adhesion, which was suggested as necessary for their function in the regulation of OSN axonal coalescence into glomeruli and synaptic specification in the hippocampus. We therefore examined the effect of non-dimerizing mutations on Kirrel-dependent adhesion using a cell aggregation assay. Suspension S2 cells were transfected with transmembrane constructs containing Kirrel ectodomains and attached to the transmembrane helix of neurexin, followed by a cytoplasmic enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP). We observed strong aggregation in transfected cultures, indicating that Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 form trans-homodimers that aggregate S2 cells (Figure 4E). When the Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 constructs carried mutations that abolish or strongly diminish dimerization through the D1 interface, such as Q128A in Kirrel3, cell aggregation was also abolished. However, an alanine mutation at the ‘‘specificity site’’ Kirrel2 Q52 did not abolish cell aggregation, as the soluble D1+D2 construct with this mutation still behaved as a dimer in SEC (Figure 4A). The analytical ultracentrifugation and cell aggregation experiments demonstrate that the D1 interface we observed in our crystal structures is required for Kirrel homodimerization, and a second interaction site within the ectodomains is either very weak to detect or does not exist.

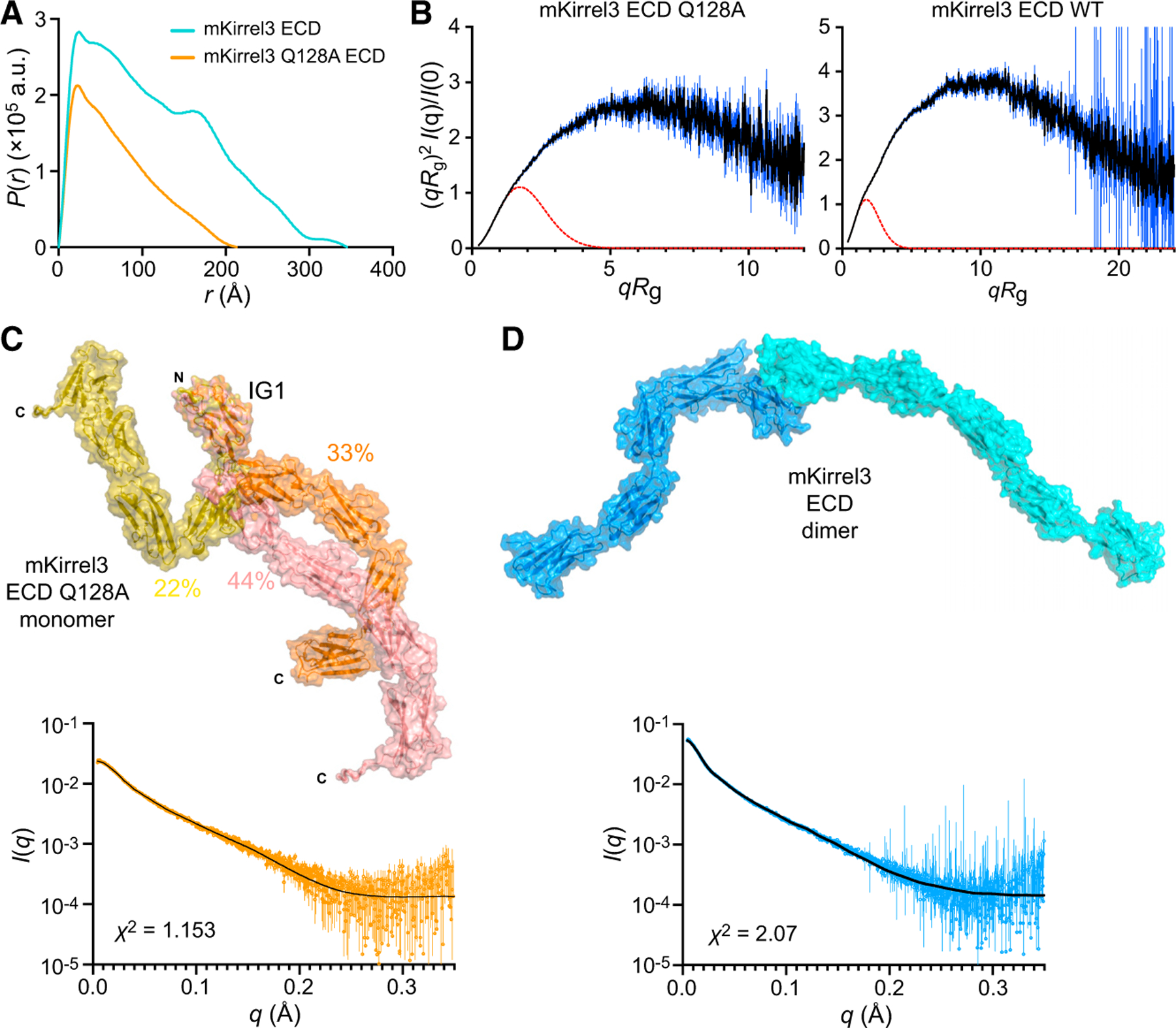

Kirrel ectodomains form elongated homodimers mediated by D1 interactions

As Kirrels are adhesion molecules carrying signaling motifs, the tertiary structure and conformational states of their ectodomains are relevant for their signaling and adhesive properties. To gain insights into the three-dimensional structure of Kirrel ectodomains, we studied Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 ectodomains in solution using an SEC-small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS)-multi-angle light scattering (MALS) setup, including the Kirrel3 Q128A mutant (Figure 5; Figure S5; Table S2). For all ectodomains tested by SAXS, shapes of pair distance distributions, P(r), show strong rod-like character rather than a globular shape or other shapes (Figures 5A and 5B; Figures S5A and S5B). Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 homodimers have maximum dimensions (Dmax) of 39 and 35 nm, respectively, while Kirrel3 Q128A has a Dmax of 21 nm, suggesting that Kirrel dimers are nearly double the length of the monomer. The accompanying MALS data recapitulate our conclusions from pure SEC runs, where concentrated wild-type Kirrels have molar masses matching dimeric sizes, and diluted Kirrel3 samples yield intermediate values between predicted monomer and dimer masses, while Kirrel3 Q128A is a pure monomer (Figure S5C; Table S3). These results agree with our elongated Kirrel model where only D1 domains interact between Kirrel monomers and support a D1-D1, or N-terminal tip-to-tip, interaction model of Kirrel homodimerization.

Figure 5. SAXS analysis of Kirrel ectodomains.

(A) Pair distance distributions, P(r), for mKirrel3 ectodomains, wild type, and Q128A. Wild-type Kirrel3 is a longer molecule than Kirrel3 Q128A because it has a larger Dmax (35 nm versus 21 nm).

(B) Dimensionless Kratky plots for mKirrel3 ectodomains; blue vertical lines are measured errors. Dashed red lines show predicted plots for rigid, globular molecules with the same Rg.

(C) Ensemble model fitting of SAXS data for mKirrel3 Q128A ectodomain using EOM. The three-model ensemble with contributions are indicated as percentages next to the models. The scattering profile predicted from the ensemble model (black) closely matches observed scattering data (orange; measurement errors are indicated by vertical bars).

(D) SASREF model of mKirrel3 wild-type ectodomain dimer and its predicted scattering (black) overlayed on observed SAXS data (blue; measurement errors are indicated by vertical bars). See also Figure S5.

A prominent feature common to Kirrel2, Kirrel3, and Kirrel3 Q128A ectodomains observed in dimensionless Kratky plots for SAXS data (Figure 5B; Figure S5B) is flexibility, likely reflecting significant interdomain movements. While this may complicate low-resolution modeling of the ectodomains, we used DAMMIF (Franke and Svergun, 2009) to create ab initio bead models. Bead models for Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 appear as a thin V with a vertex angle of approximately 115°, while a bead model for Kirrel3 Q128A is a straight rod that is as long as each of the ‘‘wings’’ of the Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 models (Figures S5D and S5E). These conformations agree with our structural models of a fixed angle of Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 dimerization defined by the D1-D1 binding interface.

Next, we attempted to model Kirrel ectodomains using an ensemble representation with EOM from the ATSAS suite (Tria et al., 2015), where flexibility was allowed between five rigid body-defined IG domains, which were available through our high-resolution Kirrel D1 structures or were modeled (domains 2 to 5) based on similar immunoglobulin domain templates. EOM can explain observed SAXS profiles for the monomeric Kirrel3 Q128A using a three-model ensemble that has theoretical scattering matching observed data with high fidelity (χ2 = 1.15) (Figure 5C). While the homodimer also shows strong flexibility based on the Kratky analysis (Figure 5B), ensemble modeling did not yield an equally satisfactory model for explaining wild-type Kirrel3 scattering data, possibly due to the presence of monomeric species in solution and a higher degree of flexibility caused by movements between ten, rather than five, domains. For the dimeric Kirrel3 wild-type SAXS data, we used SASREF from the same package to allow for interdomain flexibility within one model (Petoukhov and Svergun, 2005) (Figure 5D). When the resulting model was aligned to the SAXS bead model from DAMMIF, we observed a strong overlap, supporting the validity of our SAXS bead models as well as our model of Kirrel tip-to-tip dimerization (Figures S5D and S5E). These results further point to a lack of secondary dimerization sites.

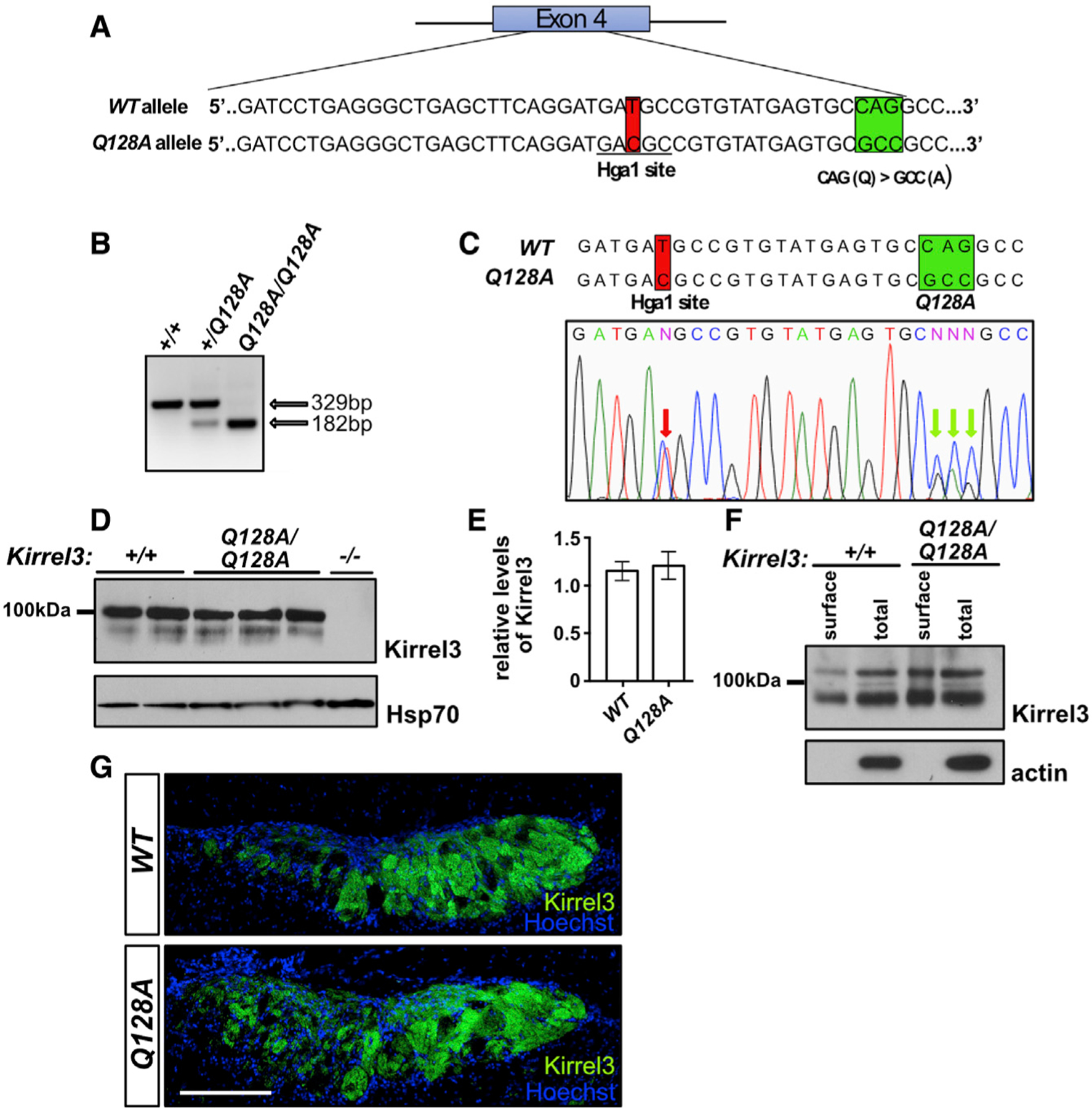

Kirrel3 Q128A mutation causes defects in glomerulus formation in the AOB

To assess whether the Kirrel D1-to-D1 model of homophilic adhesion contributes to Kirrel3 function in wiring the nervous system, we examined the effect of abolishing Kirrel3 dimerization on VSN axon targeting in the AOB. We engineered mice expressing the Kirrel3 Q128A amino acid substitution, which abolishes Kirrel3 dimerization, using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) technology (Figures 6A–6C). An analysis of Kirrel3 protein in lysates extracted from brain samples of wild-type and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice revealed that Kirrel3 Q128A is expressed at comparable levels to the wild-type protein in the brain (Figures 6D and 6E). Additionally, cell surface biotinylation assays on brain slices from control and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice and cell surface staining of HEK293T cells transfected with full-length Kirrel3 Q128A in flow cytometry experiments demonstrated that the mutant protein is properly trafficked to the cell surface (Figure 6F; Figure S6).

Figure 6. Characterization of the Kirrel3 Q128A mouse.

(A) Diagram of the generation of the Kirrel3 Q128A mouse. Mice carrying a modified Kirrel3 allele containing mutations that modify amino acid 128 from a Q to an A, as well as a silent mutation introducing an HgaI restriction enzyme cutting site for genotyping purposes, were generated. Green square: Q to A mutations; red square: mutation creating an HgaI restriction site.

(B and C) Identification of the Kirrel3 Q128A allele by restriction enzyme digest and DNA sequencing. Digestion with HgaI (B) and DNA sequencing (C) of a PCR fragment from exon 4 of the Kirrel3 allele demonstrate the presence of the newly introduced HgaI restriction site. DNA sequencing also reveals the presence of the three nucleotide substitutions resulting in the Q-to-A amino acid substitution in a Kirrel3+/Q128A mouse. The red arrows in the electropherogram in (C) indicate the overlapping peaks caused by the nucleotide substitutions in one of the Kirrel3 alleles.

(D and E) Quantification of Kirrel3 protein by western blot of brain lysate collected from Kirrel3+/+ and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice shows that similar levels of Kirrel3 and Kirrel3 Q128A levels are expressed in the brain of these mice, respectively. Data were analyzed using unpaired t test; n = 3 for Kirrel3+/+ and n = 4 for Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice.

(F) Surface membrane distribution of Kirrel3 Q128A in acute brain slices. Western blots of acute brain slice lysate collected from Kirrel3+/+ and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice following incubation with biotin and isolation of surface proteins by batch streptavidin chromatography. Both Kirrel3 and Kirrel3 Q128A are distributed to the cell surface.

(G) Immunohistochemistry on sagittal sections of the AOB from Kirrel3+/+ and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A adult mice labeled with antibodies against Kirrel3 and Hoechst. The Kirrel3 and Kirrel3 Q128 proteins can be detected in subsets of glomeruli in both the anterior and posterior regions of the AOB in Kirrel3+/+ and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice, respectively. The scale bar represents 200 mm. See also Figure S6.

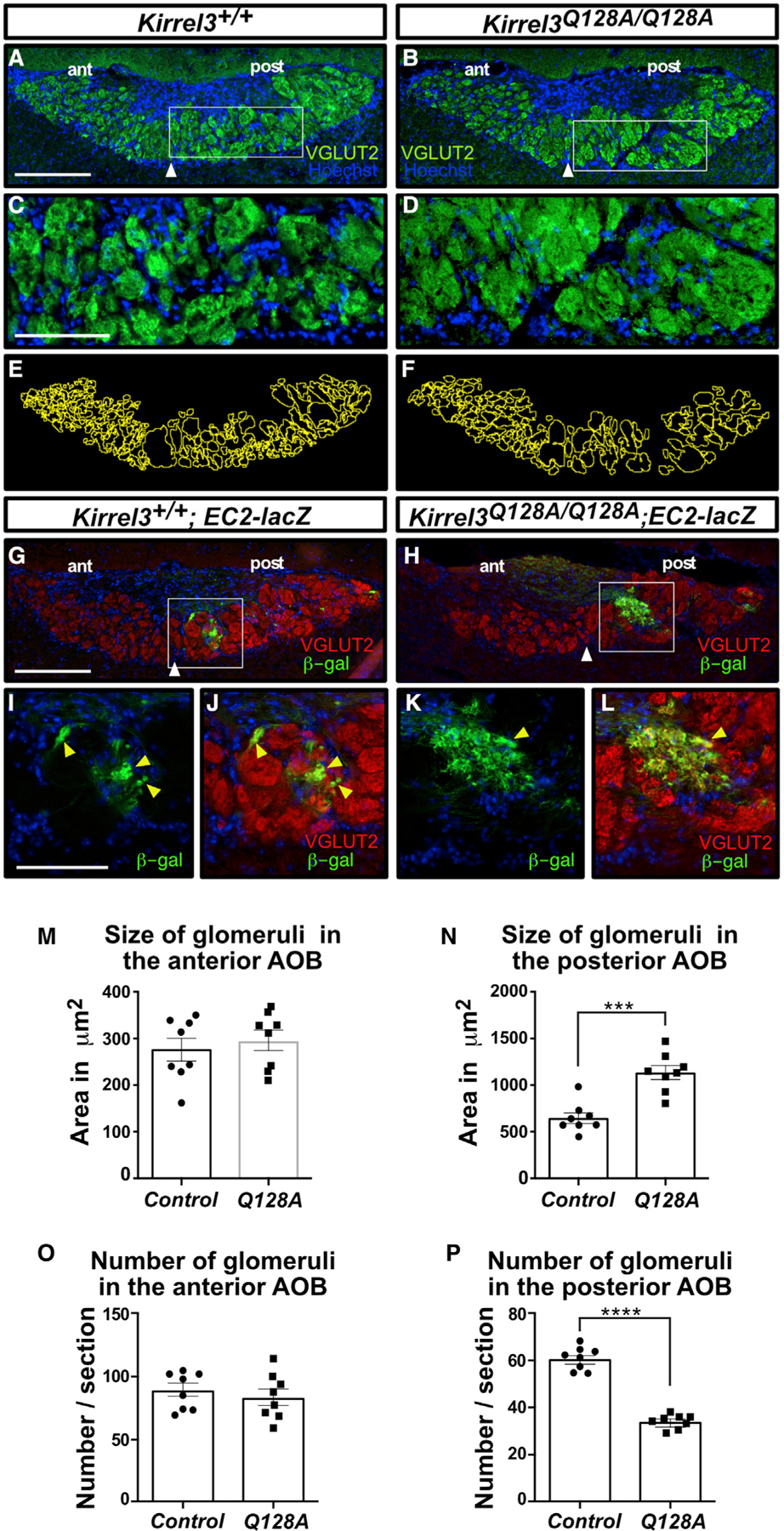

We then investigated the expression patterns of Kirrel3 Q128A on VSN axons innervating the AOB. Kirrel3 is expressed on subsets of VSN axons innervating glomeruli throughout the AOB with a large proportion of glomeruli in the posterior region expressing Kirrel3 (Prince et al., 2013). Sagittal sections of the AOB stained for Kirrel3 demonstrate a clear localization of Kirrel3 in a majority of glomeruli in the posterior region of the AOB in both wild-type and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice (Figure 6G). Since Kirrel3−/− mice show altered glomerulus structure in the posterior region of the AOB (Prince et al., 2013), we next performed a detailed analysis of the glomerular layer in Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice. To visualize and delineate glomeruli, sagittal sections of the AOB of control and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice were stained with anti-VGLUT2, which marks excitatory pre-synaptic terminals in the AOB. As previously observed in Kirrel3−/− mice (Prince et al., 2013), the size and number of glomeruli in the anterior region of the AOB appears unaffected in Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice when compared with control animals (Figures 7A, 7B, 7M, and 7O). In contrast, and as observed in Kirrel3−/− mice, the posterior region of the AOB in Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice contains significantly fewer glomeruli, and the average size of each glomerulus is increased by 76% (Figures 7A–7F, 7N, and 7P), indicating that axonal coalescence is likely affected.

Figure 7. Glomerulus structure is altered in the AOB of Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice.

(A–F) Parasagittal sections of the AOB from adult Kirrel3+/+ (A and C) and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A (B and D) mice labeled with a VGLUT2 antibody and Hoechst (A–D). Higher magnification of outlined regions in (A) and (B) are shown in (C) and (D), respectively. Glomeruli in the posterior region of the AOB in Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice appear significantly larger and less numerous than those in Kirrel3+/+ mice (E and F). White arrowheads denote the boundary between the anterior (ant) and posterior (post) regions of the AOB; n > 8 mice for each genotype.

(G–L) Parasagittal sections of the AOB from adult Kirrel3+/+; EC2-lacZ (G) and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A; EC2-lacZ (H) mice labeled with a VGLUT2 (red) and b-galactosidase (green) antibodies and Hoechst (G–L). Higher magnification of outlined regions in (G) and (H) are shown in (I) and (J) and (D) and (L), respectively. EC2-positive axons coalesce into small and well-defined glomeruli in Kirrel3+/+; EC2-lacZ mice (yellow arrowheads; I and J) but innervate larger heterogenous glomeruli in Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice (yellow arrowheads in K and L); n = 2 mice for each genotype.

(M–P) Quantification of the size and number of glomeruli in the anterior (G and I) and posterior regions (H and J) of the AOB in adult control and Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice. A representation of the glomerulus outlining approach used for quantification using sections in (A) and (B) as examples are shown in (E) and (F), respectively. A significant increase in the size of glomeruli in the posterior (control: 644.0 ± 56.2 μm2; Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A: 1,134.1 ± 74.5 μm2), but not anterior (control: 284.0 ± 19.6 μm2; Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A: 295.6 ± 22.1 μm2), region of the AOB is observed in the Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice (G and H). There is also a decrease in glomerulus numbers in the posterior (control: 61.15 ± 1.75; Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A: 34.27 ± 1.02), but not anterior (control: 87.21 ± 4.92; Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A: 84.22 ± 6.33), region of the AOB in Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice (J). Data were analyzed using unpaired t test; n = 8 mice for each genotype. ****p value < 0.0001 (glomerular counts); ***p value < 0.001 (glomerular size); error bars: ±standard error of the mean (SEM); scale bars, 250 μm in (A) and (B) and 100 μm in (C) and (D).

To examine the targeting and coalescence of VSN axons, we crossed the Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice with mice expressing tau-lacZ in a specific population of VSNs that expresses the vomeronasal receptor EC2 and innervates specifically the posterior region of the AOB (Cloutier et al., 2004). EC2-positive VSNs also express Kirrel3 (Prince et al., 2013). As expected, the segregation of EC2-positive axons to the posterior region of the AOB was unaffected in Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice because this process does not require Kirrel3 expression (Figures 7G and 7H) (Prince et al., 2013). In control animals, coalescing EC2-positive axons form small well-defined glomeruli that are innervated by a single population of VSN axons (Figures 7I and 7J). In contrast, EC2-positive axons coalesce into larger heterogenous glomeruli innervated by additional populations of VSN axons in Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice, as previously observed in Kirrel3−/− mice (Figures 7K and 7L) (Prince et al., 2013). Thus, the Kirrel3 D1-D1 binding interface is necessary for proper coalescence of VSN axons into glomeruli of the AOB.

DISCUSSION

The wiring of the nervous system is guided by a combination of intercellular interactions mediated by cell surface receptors (Sanes and Zipursky, 2020). The interactions can be heterotypic, usually allowing for establishing connectivity between different neuronal types, guiding growth of axons in a gradient field established by cues, or by contacts between processes resulting in attraction or repulsion. Homotypic interactions can also be used to establish synaptic connections (as Kirrel3 is proposed to mediate in the hippocampus) and lead to contact-mediated repulsion or to fasciculation and coalescence of axons. Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 are differentially expressed in sets of sensory neurons whose axons are segregated into separate glomeruli in the accessory and main OBs. This differential expression of Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 likely generates a molecular code of recognition that contributes to the coalescence of axons expressing the same sensory receptor into glomeruli. However, the molecular mechanism through which differential expression of Kirrel family members in populations of sensory axons modulates their segregation into glomeruli remained to be addressed.

Structures presented here show that Kirrel2 has key residues that allow for the formation of a hydrogen-bonding network at the homodimeric interface, while Kirrel3 evolved a hydrophobic interface in lieu of this hydrogen-bonding network. Mutating the Kirrel3 interface to install hydrogen-bonding amino acids allows it to bind Kirrel2. Ancestral vertebrate Kirrel has crucial amino acids compatible with the presence of the hydrogen-network, and this specialization of a non-polar Kirrel3 interface core likely evolved to ensure exclusive homodimerization of the two Kirrels and no heterodimerization, allowing for the segregation of OSN termini into separate Kirrel2- and Kirrel3-expressing glomeruli. Future work should reveal the individual contributions of the proposed substitutions in ancestral Kirrels to binding specificity and affinity. This finding of incompatible interface chemistries is distinct to the vertebrate Kirrels; the two fruit fly Kirrel dimerization interfaces show strong conservation and compatible chemistries that would allow them to create putative complexes (Özkan et al., 2014), and there is evidence that fly Kirrels can form heterodimers (Özkan et al., 2013). We otherwise found that Kirrel duplications outside vertebrates is relatively rare.

The distribution of extant Kirrel proteins we identified in cyclostomes and gnathostomes is consistent with the duplication of Kirrels during the early chordate whole-genome duplication events (Dehal and Boore, 2005). Given that ancestral Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 have chemically incompatible interface sequences similar to mouse Kirrels and that extant jawed fish Kirrel sequences also follow these patterns, Kirrel specialization must have appeared early in gnathostomes and before the rise of distinct accessory olfactory systems and several expansions in olfactory receptor gene families (Bear et al., 2016; Poncelet and Shimeld, 2020). Therefore, it is attractive to speculate that specialization of Kirrels and other cell surface receptors differentially expressed in OSNs and VSNs and duplicated during the whole-genome duplication events may have set the stage for increases in olfactory receptors, OSNs, and glomeruli in main and accessory OBs.

Kirrels have been identified and implicated in numerous functional contexts in the nervous system. Loss of Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 causes disorganization of a subset of glomeruli in the main and accessory OBs (Brignall et al., 2018; Nakashima et al., 2019; Prince et al., 2013; Vaddadi et al., 2019), and Kirrel3-knockout mice show behavioral abnormalities (Hisaoka et al., 2018; Völker et al., 2018), including loss of male-male aggression likely as a result of miswiring in the AOB (Prince et al., 2013). Furthermore, several Kirrel3 mutations in human autism and intellectual disability patients were identified (see Taylor et al., 2020 for a list). To our surprise, none of the missense mutations are in the first domain, including mutations recently reported to affect Kirrel3-mediated cell adhesion (Taylor et al., 2020). We therefore studied the entire Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 ectodomains using a combination of biophysical methods but could not produce evidence that there are secondary binding sites outside the D1-D1 interface. A single alanine mutation at the D1-D1 Kirrel3 dimer interface completely abolishes ectodomain dimerization even at micromolar concentrations. SAXS data suggest highly elongated models for dimerized Kirrels compatible with D1-D1 intermolecular interactions, further rendering other putative binding sites unlikely or very weak. Additional structural studies on liposomes or lipid bilayers may be necessary to refute or confirm secondary cis or trans binding sites within or outside the first domain.

We also showed that the dimerization interface observed in our structures directly contributes to axonal coalescence and glomerulus formation, at least in the case of Kirrel3. Analysis of axonal targeting and glomerular morphology in the AOB of Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice closely resembled those of the Kirrel3 knockout, where glomeruli increase in size and are heterogeneously innervated in the posterior AOB. We have confirmed that the Q128A mutant displays correctly to the cell surface, which implies that the observed AOB phenotype is not due to misfolding or trafficking errors. Although we did not test Kirrel2 loss-of-function mutations in vivo, Kirrel2 shares a closely related structure and evolutionary history with Kirrel3, and it is reasonable to assume that the dimerization interface on Kirrel2 D1 may also control glomerulus formation in a similar manner.

While Kirrel homodimerization is necessary for proper axonal coalescence and glomerulus formation, additional factors also contribute to this process, including vomeronasal and olfactory receptor expression and neuronal activity (Belluscio et al., 1999; Feinstein and Mombaerts, 2004; Feinstein et al., 2004; Movahedi et al., 2016; Nakashima et al., 2019; Rodriguez et al., 1999; Rodriguez-Gil et al., 2015). Furthermore, the combinatorial expression of additional families of cell surface molecules likely adds to the axonal molecular diversity necessary to segregate large populations of axons into glomerular target fields by modulating the adhesion of similar axons or repulsion of dissimilar axons (Ihara et al., 2016; Kaneko-Goto et al., 2008; Mountoufaris et al., 2017; Serizawa et al., 2006). Kirrel3 is expressed in a majority of VSN axons innervating the posterior region of the AOB as well as in subsets of axons innervating the anterior part of the AOB. While glomerular formation is affected in the posterior region of the AOB in both Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A and Kirrel3−/− mice, we could not detect statistically significant changes in glomerulus formation in the anterior AOB in these mice (Figure 7; Prince et al., 2013). This observation suggests that additional families of cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) may be expressed specifically in VSNs innervating the anterior AOB and compensate for the loss of Kirrel3 function in the targeting of these axons to the anterior AOB.

Whether Kirrels function as axonal sorting molecules relies strictly on their adhesive properties to promote coalescence of like axons or also necessitates intracellular signaling that impinges on this process remains to be determined. Nonetheless, multiple lines of evidence support the idea that Kirrels and Kirrel homologs act as more than just ‘‘molecular Velcro’’ in nervous system development. In hippocampal neuron cultures, Kirrel3 homophilic adhesion is required, but not sufficient, for synapse formation, and mutations that occur outside of the D1 binding domains and even in the intracellular domains prevent synapse formation, despite being able to form homodimeric complexes (Taylor et al., 2020). The C. elegans homologs SYG-1 and SYG-2 were shown to be signaling receptors whose functions depend on the exact geometry of ectodomain dimerization also mediated by D1 (Özkan et al., 2014). Finally, Kirrels carry conserved and functional signaling motifs in their cytoplasmic domain, including phosphorylation sites, PDZ motifs, and actin cytoskeleton recruitment sequences (Bulchand et al., 2010; Chia et al., 2014; Gerke et al., 2006; Harita et al., 2008; Huber et al., 2003; Sellin et al., 2003; Yesildag et al., 2015). These findings suggest that Kirrel3 undergoes active signaling once the homodimeric complexes have formed, which may be influenced by the overall flexibility and conformation of the extracellular domains and how tightly Kirrels may pack at the site of a Kirrel-mediated cell adhesion. Future studies assessing a requirement for the Kirrel intracellular domain in selective axonal segregation and synapse specification in the nervous system should help address the contribution of Kirrel signaling to these processes.

Limitations of the study

Our work does not resolve the individual contributions of the identified amino acids to binding affinity and does not attempt to reveal the historical substitutions that led to paralog specificity, which requires biochemical studies of the ancestral proteins. While loss of VSN axonal adhesion likely underlies the improper formation of glomeruli observed in the AOBs of Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A mice, we cannot exclude the possibility that expression of this mutant protein in mitral/tufted cells of the AOB, which project dendrites into these glomeruli, may in part contribute to the disorganized arrangement of AOB glomeruli in these mice (Brignall et al., 2018).

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and materials should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Engin Özkan (eozkan@uchicago.edu).

Materials availability

Plasmids and mice generated in this study will be made available to other researchers via Institutional Material Transfer Agreements.

Data and code availability

Data reported in this manuscript are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request. Atomic coordinates and crystallographic structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession codes PDB: 7LTW and 7LU6 (Table S1). Small-angle X-ray scattering data, models, and their fits to scattering data are deposited in the Small-Angle Scattering Biological Data Bank (SASBDB) with accession codes SASDMN2, SASDMP2 and SASDMQ2.

This study does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Cell lines

D. melanogaster S2 cells were maintained as shaking cultures in Schneider’s media (Lonza, catalog no. 04–351Q) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Sigma-Aldrich, catalog no. F0926) at 27°C. Trichoplusia ni High Five (BTI-Tn-5B1–4) cells were cultured shaking in serum-free Insect-XPRESS (Lonza, catalog no. 12–730Q) at 27°C. HEK293T cells were cultured at 37°C using Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium with high glucose (ThermoFisher, catalog no. 11965092) and detached using a 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA solution (ThermoFisher, catalog no. 25200056).

Animal models

The Kirrel3 Q128A mouse line was generated as follows: sgRNAs were designed using the open access software Breaking-Cas (https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/breakingcas) (Oliveros et al., 2016) and tested for cutting efficiency using a T7 assay as previously described (Sakurai et al., 2014). One-cell stage C57Bl6 mouse zygotes were microinjected with the sgRNA, Cas9 protein, and a donor DNA template to introduce the required DNA mutations in the Kirrel3 allele (see Figure 6A) and were implanted in surrogate female mice. Offsprings were screened for the presence of the target mutations by PCR, restriction enzyme analysis, and DNA sequencing. Three Kirrel3 Q128A founder lines were chosen for further analyses and backcrossed for three generations in the C57Bl6 background to segregate any potential off-target mutations. Analyses of the glomerular structure of the AOB presented in Figure 7 was performed on Kirrel3 Q128A mice derived from a single founder line. Similar analyses were also performed on Kirrel3 Q128A mice derived from two other founder lines and revealed similar phenotypes (data not shown). The EC2-tau-lacZ (Tg(Vmn2r43-lacZ*)#Ddg) mouse line has previously been described (Cloutier et al., 2004). All analyses were performed on three to six month old littermate control and mutant animals of both sexes. All animal procedures have been approved by The Neuro Animal Care Committee and McGill University, in accordance with guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

METHOD DETAILS

Protein expression and purification

For biophysical and structural studies, mouse Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 constructs were expressed in High Five cells (Trichoplusia ni) using the baculovirus expression system. All expression constructs were tagged C-terminally with hexahistidine tags in the baculoviral transfer vector pAcGP67A (BD Biosciences). Proteins were purified using Ni-NTA agarose (QIAGEN) resin first, followed by size-exclusion chromatography with Superdex 75 10/300 or Superdex 200 10/300 Increase columns (GE Healthcare) in 1x HBS (10 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 150 mM NaCl). We observed that some of the Kirrel constructs tend to precipitate at higher concentrations at 4°C; therefore, proteins were purified and stored only for short periods at 16 to 22°C.

Protein crystallization

Purified mKirrel2 D1 was concentrated to 10.6 mg/ml and crystallized using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method in 0.4 M Potassium/Sodium tartrate. Crystals were cryo-protected in 0.5 M Sodium acetate, 30% Ethylene glycol, and vitrified in liquid nitrogen. Complete diffraction dataset was collected at the SSRL beamline 12–2.

Purified mKirrel3 D1 was concentrated to 9.1 mg/ml and crystallized using the sitting-drop vapor-diffusion method in 0.1 M Sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, 1.4 M Sodium acetate. Crystals were cryo-protected in 0.1 M Sodium cacodylate, pH 6.5, 1.4 M Sodium acetate with 30% Ethylene glycol, and vitrified in liquid nitrogen. Complete diffraction dataset was collected at the APS beamline 24-ID-E.

Structure determination by X-ray crystallography

Diffraction data were reduced using HKL2000 (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Structure of mKirrel2 D1 was phased with molecular replacement using mouse Duf/Kirre D1 as model (PDB ID: 4OFI; Özkan et al., 2014) with PHASER (McCoy et al., 2007) as part of the PHENIX suite (Liebschner et al., 2019). For molecular replacement of the mKirrel3 D1 dataset, a partly refined mKirrel2 D1 structure was used. Model building and refinement were done using Coot (Emsley et al., 2010) and phenix.refine (Afonine et al., 2012), respectively. mKirrel3 D1 model was refined with eight TLS groups, one for each chain in the asymmetric unit, while no TLS refinement was used for the mKirrel2 model. Crystal structures and structure factors are deposited with the Protein Data Bank with accession codes 7LTW (mKirrel2 D1) and 7LU6 (mKirrel3 D1). Crystallographic data and refinement statistics are tabulated in Table S1.

Phylogenetics and ancestral sequence reconstructions

Putative Kirrel orthologs were identified using a reciprocal BLAST strategy with the three mouse Kirrels, mouse Nephrin, and D. melanogaster Rst and Kirre. Each sequence hit was confirmed to contain conserved features of Kirrels and Nephrins, specifically five and ten IG/FnIIII domains, respectively, in the extracellular regions, and a membrane helix. A total of 90 Kirrel and 41 Nephrin-like proteins were identified across major protostome and deuterostome taxa; we failed to detect clear Kirrel and Nephrin orthologs in other metazoan groups.

The mature ectodomains of 90 Kirrel sequences were aligned using MUSCLE (version 3.8.425) with default parameters (Edgar, 2004), as the other regions cannot be aligned with high confidence. Parts of the alignment with insertions represented by few sequences were removed, and maximum likelihood phylogenies were inferred using RAxML-NG v1.0.1 (Kozlov et al., 2019) using the best-fit LG+I+G4 evolutionary model determined by MODELTEST-NG (Darriba et al., 2020). Among the three vertebrate Kirrels, Kirrel2 shows faster and heterogenous rates of evolution in gnathostomes. Ancestral sequences were inferred using the marginal reconstruction algorithm in PAML v4.8 (Yang, 2007) using the LG+G4 model and the amino acid frequencies inferred on the ML tree by RAxML v8.2.12 (Stamatakis, 2014).

Sequence logos are calculated in Geneious version 2020.2 (https://www.geneious.com). The list of species from which the sequences are collected are in the legend for Figure S3.

Co-immunoprecipitation assay

Baculoviruses expressing WT and mutant Kirrel3 ectodomains with C-terminal FLAG tags, and WT Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 ectodomains with C-terminal hexahistidine-tags were used to infect High Five cells. Cultures were spun down 60 to 72 hours post-infection, and conditioned media were collected. Hexahistidine-tagged Kirrel cultures were mixed with FLAG-tagged Kirrel cultures at 1:1 volume (total: 1000 µl) and incubated for 3 hours at room temperature with Anti-DYKDDDDK G1 affinity resin (GenScript) to capture WT and mutant Kirrel3-FLAG. Proteins captured on beads were washed twice in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, pH 7.6), eluted using 0.5 mg/ml FLAG peptide in TBS, and mixed with 6x SDS sample loading buffer. Following SDS-PAGE, samples were blotted onto Sequi-Blot PVDF membranes (Bio-Rad), and co-immunoprecipitated Kirrel2-His6 was detected using anti-His antibodies conjugated to iFluor 488 (GenScript). Anti-DYKDDDDK antibodies conjugated to iFluor 488 (GenScript) were also used to detect and confirm expression of FLAG-tagged Kirrel3 constructs captured on resin. Western blot band intensity was measured in Image Lab (BioRad) and adjusted for background. Data were analyzed using the unpaired t test in Prism 8 (GraphPad).

Analytical ultracentrifugation

Analytical ultracentrifugation data was collected at the UT Southwestern Macromolecular Biophysics Resource laboratory. mKirrel2 and mKirrel3 ectodomain samples were placed in 0.3 or 1.2-cm charcoal-filled Epon centerpieces sandwiched between sapphire windows. Cells were placed in an An50-Ti rotor and spun at 20°C at 50,000 rpm for sedimentation velocity experiments. During the spins, concentration profiles were measured using absorbance at 230 nm or using Rayleigh interferometry for the highest concentration samples (blue points in isotherms in Figures S4G and S4H). The data were analyzed using the c(s) methodology in SEDFIT (Schuck, 2000). Partial-specific volume, density, and viscosity were calculated using SEDNTERP (Laue et al., 1992), and the following values were used in data analysis: ε230 = 389,836 (mKirrel2) and 395,466 (mKirrel3) M−1cm−1; εinterferometric = 150,896 (mKirrel2) and 151,329 (mKirrel3) M−1cm−1; ρ(solution) = 1.0052 g/cm3; η(solution) = 0.010249 Poise.

To calculate dissociation constants, GUSSI (Brautigam, 2015) was used to integrate the c(s) distributions, which were assembled into isotherm files that were imported into SEDPHAT, where a monomer-dimer model was imposed (Schuck, 2003) with a fixed s-value for the monomer (2.87 S). All AUC figures were rendered in GUSSI.

The Q128A mutant for the mKirrel3 ectodomain displayed an unmoving peak at all concentrations with a calculated sedimentation coefficient of 2.87 S, which represents the monomer, while the WT mKirrel2 and mKirrel3 ectodomains had c(s) distributions showing increasing sedimentation coefficients with increasing protein concentrations, where dimeric mKIrrel2 and mKirrel3 have refined sedimentation coefficients of 3.9 and 3.8 S, respectively. The single peaks observed in the S versus c(s) plots, in addition to size-exclusion chromatography elution profiles showing single peaks corresponding to intermediate hydrodynamic sizes, strongly suggest fast rates of dimerization kinetics (koff > 10−3 s−1)

Cell aggregation assays

Kirrel ectodomains were cloned in the Drosophila expression plasmid pAWG (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center), and transiently transfected in S2 cells using Effectene (QIAGEN, catalog no. 301425). Cells were collected three days post-transfection, spun down at 250 x g for 5 minutes, washed once with phosphate-buffered saline, and re-suspended in serum-free Schneider’s media (Lonza, catalog no. 04–351Q) at 107/ml cell density before imaging.

SEC-SAXS-MALS

Scattering data was collected for Kirrel ectodomains at the Advanced Photon Source beamline 18-ID using a SEC-SAXS-MALS setup. BioXTAS RAW version 2.0.2 was used for SAXS data collection and data reduction (Hopkins et al., 2017). The RAW interface was also used for Guinier analysis of the scattering data and the indirect Fourier transform methods implemented in GNOM (Svergun, 1992), part of the ATSAS package (Manalastas-Cantos et al., 2021), for pair-distance distribution analysis. Domains 2 to 5 for mKirrel3 were modeled using the I-TASSER server (Roy et al., 2010; Yang and Zhang, 2015). Modeling using the SAXS data was performed using the ATSAS package version 3.0.3 with the ab initio shape determination by bead modeling in DAMMIF (Franke and Svergun, 2009), with the ensemble optimization method implemented in EOM (Tria et al., 2015), and with the simulated annealing protocol for connected domains in SASREF (Petoukhov and Svergun, 2005). Further details about SAXS data collection and analysis are tabulated in Table S2, and scattering data are deposited at the SASBDB.

Light scattering data was collected at the APS 18-ID beamline on a DAWN HELEOS with a T-rEX refractometer (Wyatt Technology) at 25°C, and analyzed in ASTRA version 7.3.2.19. dn/dc values of 0.181 to 0.182 were used to account for predicted glycosylation for molar mass calculations. Further details about MALS data collection and analysis are tabulated in Table S3. Expected molecular masses for Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 WT ectodomain constructs without glycosylation are both 53.0 kDa. With predicted N-linked glycosylation added by the insect cell expression system, we expect molecular masses for Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 WT ectodomain monomers to be 56 to 59 kDa.

Flow cytometry assay for cell surface trafficking

Kirrel3 WT and Q128A cDNA, excluding the signal peptide, were cloned C-terminal to a preprotrypsin leader sequence and a FLAG peptide (DYKDDDDK) under the control of the CMV promoter, and transfected into HEK293T cells using LipoD293 (SignaGen Laboratories, catalog no. SL100668). After 48 h, transfected cells were detached from the cell culture plate by incubating cells in a citric saline solution (135 mM potassium chloride, 50 mM sodium citrate) at 37°C for 5 min, followed by addition of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (Thermo Fisher, catalog no. 11965092) with 10% fetal bovine serum and mechanical suspension of cells. Cells were spun down at 500 g for 5 min washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; Thermo Fisher, catalog no. BP661–50, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 11.9 mM phosphate, pH 7.4), then resuspended in PBS + 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). For staining of Kirrel3 displayed on the cell surface, cells were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma, catalog no. F3165; 1:1000 dilution in PBS with 0.1% BSA) for 30 min at room temperature, washed twice with PBS + 0.1% BSA, then incubated with a secondary donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (Thermo Fisher, catalog no. A-21202; 1:500 dilution in PBS with 0.1% BSA). In preparation for flow cytometry, cells were washed twice and resuspended in PBS + 0.1% BSA. Surface display of the Kirrel3 ectodomains on HEK cells were measured on the Accuri C6 flow cytometer (BD Biosciences) with the 488 nm excitation laser and the 533 nm filter in 10,000 cells per sample.

Immunohistochemistry

Two to three-month-old adult mice were anesthetized and perfused transcardially with 10 mL ice-cold 1x PBS followed by 10 mL 4% paraformaldehyde solution in 1x PBS. Brains were dissected and post-fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 30 min followed by 24 h cryoprotection in 30% sucrose. 20 µm-thick sagittal AOB sections were collected on microscope slides and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: Anti-VGLUT2, 1:500 (Synaptic Systems) or anti-Kirrel3, 1:100 (Neuromab). After rinsing in Tris-Buffered Saline, the appropriate secondary antibody-Alexa 488 conjugate (Molecular Laboratories) was applied at 1:500 dilution to detect the primary antibody and BS lectin at 1:1500 (Vector Laboratories) was applied along with the secondary antibody. Sections were counter-stained with Hoechst at 1:20,000 dilution (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Analysis of glomeruli in the AOB

Analysis of the size and number of glomeruli in AOB sections were performed as previously described (Brignall et al., 2018; Prince et al., 2013). 20 µm-thick sagittal sections of the AOB were obtained from Kirrel3+/+, Kirrel3 +/Q128A, and Kirrel3 Q128A/Q128A mouse brains. A blinded analysis measuring glomerular size and number using Fiji software (Schindelin et al., 2012) was performed on 8 to 10 consecutive sections from both AOBs that contained anterior and posterior regions of similar sizes at comparable medial-lateral level. Each VGLUT2 positive unit surrounded by a region of non-innervated neuropil was defined as a glomerulus and was manually traced on Fiji by an expert. The number of glomeruli and their sizes was measured from each section examined and the average values for each mouse brain was calculated. Since no difference was observed between Kirrel3+/+ and Kirrel3 +/Q128A mice, they were grouped together and designated as Controls. The anterior-posterior AOB border was identified by staining sections with BS lectin (data not shown). Littermates were used for analyses.

Analysis of Kirrel3 protein expression

Whole brain lysates were harvested using 20 mM HEPES, 320 mM sucrose with protease inhibitors (0.1 µg/µl Leupeptin/Aprotinin and 1 mM PMSF). Protein concentration of lysate was determined using the Bio-Rad protein concentration assay and equal amounts of protein were loaded and subjected to SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis followed by transfer to PVDF membranes (Immobilon-P). Membranes were probed with mouse anti-Kirrel3 1:100 (Neuromab Clone N321C/49; catalog no. 75–333) that detects the long and short isoforms of Kirrel3, rat anti-HSC70/HSP73 1:10,000 (Enzo Life Sciences), or rabbit anti-β-actin 1:1,000 (Cell Signaling Technology), followed with appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Blots were developed using SuperSignal West Femto Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Quantification of relative protein levels was performed on scanned immunoblots using Fiji software.

Cell surface biotinylation in acute brain slices

Cell surface biotinylation assay was performed as described (Gabriel et al., 2014). Acute mouse brain slices were prepared from Kirrel3Q128A/Q128A and Kirrel3+/+ mice, placed in ACSF and allowed to recover in a recovery chamber for 1 hour at room temperature. Two slices were incubated in in chilled ACSF containing 1 mg/ml EZ-link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 45 minutes. The biotin was then quenched with two washes of 10 mM Glycine in ACSF at 4°C followed by three washes in ice cold ACSF for 5 min. Slices were then harvested in RIPA buffer (10 mM Tris pH 7.45, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.1% SDS and 1% sodium deoxycholate) supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (100 mM PMSF and PhosSTOP tablet (Roche)). Biotinylated proteins were precipitated with streptavidin-agarose beads (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 4°C overnight, washed, and eluted from beads using SDS-PAGE reducing sample buffer. Equal amounts of protein were then subjected to a Western Blot analysis as described above.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Statistical analysis for coimmunoprecipitation data was performed in Prism 8 (GraphPad Software). Statistical details for all experiments, including value and definition of n, error bars, and significance thresholds can be found in the Figure Legends.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

|

| ||

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Kirrel3; clone N321C/49 | Neuromab | Catalog no. 75–333; RRID: AB_2315857 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-VGLUT2 | Synaptic Systems | Catalog no. 135402; RRID: AB_2187539 |

| Anti-FLAG M2 antibody | Sigma | Catalog no. F3165; RRID: AB_259529 |

| THE™ His tag antibody [iFluor 488] | GenScript | Catalog no. A01800 |

| Secondary donkey anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 | Thermo Fisher | Catalog no. A-21202; RRID: AB_141607 |

| Rat anti-HSC70/HSP73 | Enzo Life Sciences | Catalog no. ADI-SPA-815-D; RRID: AB_2039279 |

| Rabbit anti-β-actin | Cell Signaling Technology | Catalog no. 8457P; RRID: AB_10950489 |

|

| ||

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

|

| ||

| Anti-DYKDDDDK G1 affinity resin | GenScript | Catalog no. L00432 |

| Rhodamine-Griffonia (Bandeiraea) Simplicifolia Lectin I | Vector Laboratories | Catalog no. RL-1102–2 |

| EZ-link Sulfo-NHS-SS-Biotin | Thermo Fisher | Catalog no. 21331 |

| Hoechst 33342 | Thermo Fisher | Catalog no. H3570 |

|

| ||

| Critical commercial assays | ||

|

| ||

| Super Signal Western Femto Kit | Thermo Fisher | Catalog no. 34094 |

|

| ||

| Deposited data | ||

|

| ||

| Crystal structure and structure factors for mKirrel2 D1 | This paper | PDB: 7LTW |

| Crystal structure and structure factors for mKirrel3 D1 | This paper | PDB: 7LU6 |

| Small-angle X-ray scattering data for mKirrel2 ECD | This paper | SASBDB: SASDMN2 |

| Small-angle X-ray scattering data and model for mKirrel3 ECD | This paper | SASBDB: SASDMP2 |

| Small-angle X-ray scattering data and model for mKirrel3 Q128A ECD | This paper | SASBDB: SASDMQ2 |

|

| ||

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

|

| ||

| D. melanogaster S2 cells | Laboratory of K. Christopher Garcia | N/A |

| Trichoplusia ni High Five (BTI-TN-5B1–4) cells | Laboratory of K. Christopher Garcia | Thermo Fisher B85502 |

|

| ||

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

|

| ||

| EC2-tau-lacZ mouse line (Tg(Vmn2r43-lacZ*)#Ddg) | Cloutier et al., 2004 | N/A |

|

| ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

|

| ||

| PCR genotyping WT5′- GATGATGCCGTGTATGAGTGCCAG | This paper | N/A |

| PCR genotyping WT3′- GAAATCCAAAGGTGAGCCTCC (common to WT and Q128A alleles) | This paper | N/A |

| PCR genotyping Q128A5′- GATGACGCCGTGTATGAGTGCGCC | This paper | N/A |

|

| ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

|

| ||

| HKL2000 | Otwinowski and Minor, 1997 | https://hkl-xray.com/ |

| PHASER v. 2.6.0 | McCoy et al., 2007 | https://www.phaser.cimr.cam.ac.uk |

| PHENIX suite v. 1.19.1 | Liebschner et al., 2019 | http://phenix-online.org/ |

| phenix.refine | Afonine et al., 2012 | https://phenix-online.org/documentation/reference/refine_gui.html |

| Coot | Emsley et al., 2010 | https://www2.mrc-lmb.cam.ac.uk/personal/pemsley/coot/ |

| MUSCLE v. 3.8.425 | Edgar, 2004 | https://www.drive5.com/muscle/ |

| RAxML-NG v. 1.0.1 | Kozlov et al., 2019 | https://github.com/amkozlov/raxml-ng |

| RAxML v. 8.2.12 | Stamatakis, 2014 | https://github.com/stamatak/standard-RAxML |

| MODELTEST-NG | Darriba et al., 2020 | https://github.com/ddarriba/modeltest |

| PAML v. 4.8 | Yang, 2007 | http://abacus.gene.ucl.ac.uk/software/paml.html |

| SEDFIT | Schuck, 2000 | http://www.analyticalultracentrifugation.com |

| SEDNTERP | Laue et al., 1992 | http://www.jphilo.mailway.com/download.htm |

| SEDPHAT | Schuck, 2003 | http://www.analyticalultracentrifugation.com |

| GUSSI | Brautigam, 2015. | https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/labs/mbr/software/ |

| I-TASSER | Yang and Zhang, 2015 | https://zhanglab.dcmb.med.umich.edu/I-TASSER/ |

| BioXTAS RAW v. 2.0.2 | Hopkins et al., 2017 | https://bioxtas-raw.readthedocs.io/ |

| GNOM v. 5.0 (r10552) | Svergun, 1992 | https://www.embl-hamburg.de/biosaxs/gnom.html |

| ATSAS 3.0.2 (r12592) | Manalastas-Cantos et al., 2021 | https://www.embl-hamburg.de/biosaxs/software.html |

| DAMMIF r12593 | Franke and Svergun, 2009 | https://www.embl-hamburg.de/biosaxs/dammif.html |

| EOM r12736 | Tria et al., 2015 | https://www.embl-hamburg.de/biosaxs/eom.html |

| SASREF (from ATSAS 3.0.2, r12592) | Petoukhov and Svergun, 2005 | https://www.embl-hamburg.de/biosaxs/sasref.html |

| ASTRA v. 7.3.2.19 | Wyatt Technology | https://www.wyatt.com/products/software/astra.html |

| Breaking-Cas | Oliveros et al., 2016 | https://bioinfogp.cnb.csic.es/tools/breakingcas |

| Fiji | Schindelin et al., 2012 | https://imagej.net/software/fiji/ |

Highlights.

Mouse Kirrel dimer structures are reported

Kirrel2 and Kirrel3 homodimerize exclusively due to mismatch in interface chemistry

Dimerization specificity determinants are revealed and engineered

Coalescence of vomeronasal axons expressing non-dimerizing Kirrel3 is disrupted

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Nathan Canniff for technical support, Davide Comoletti for suggestions and guidance, and the McGill Integrated Core for Animal Modeling supported by the Goodman Cancer Institute for their advice and generation of genetically modified animals. We acknowledge excellent support by Chad Brautigam with analytical ultracentrifugation experiments at the UT Southwestern Macromolecular Biophysics Resource Laboratory and Srinivas Chakravarthy at the Advanced Photon Source (APS) SAXS beamline BioCAT 18-ID. This research used resources of the APS, a US. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under contract number DE-AC02-06CH11357. Work at BioCAT was supported by grant 9P41GM103622 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Pilatus 3 1M detector in BioCAT was provided by grant 1S10OD018090-01 from NIGMS. X-ray diffraction data were collected at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) beamline 12-2 and APS beamline 24-ID-E. Use of the SSRL, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the US DOE, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under contract number DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the NIH, NIGMS (including P41GM103393). Beamline 24-ID-E at the Northeastern Collaborative Access Team is funded by NIGMS, NIH (P30 GM124165). We acknowledge funding support from NIH through grants R01NS097161 (to E.Ö.), R01GM131128 (to J.W.T.), R01GM121931 (to J.W.T.), and R01GM139007 (to J.W.T.), from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-136872), the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada (RGPIN-2017-05208), and from the McGill University–Hebrew University–Institute for Medical Research Israel-Canada Joint Research Program (to J.F.C.), from the Healthy Brain Healthy Lives program of McGill University and Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé (to N.V. and S.Q.). Y.P. was supported by Samsung Scholarship, and J.S.P. was supported by a Steiner Award from the University of Chicago’s Division of Biological Sciences.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109940.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Afonine PV, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Moriarty NW, Mustyakimov M, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, Zwart PH, and Adams PD (2012). Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 68, 352–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear DM, Lassance J-M, Hoekstra HE, and Datta SR (2016). The Evolving Neural and Genetic Architecture of Vertebrate Olfaction. Curr. Biol 26, R1039–R1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belluscio L, Koentges G, Axel R, and Dulac C (1999). A map of pheromone receptor activation in the mammalian brain. Cell 97, 209–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla K, Luo Y, Buchan T, Beachem MA, Guzauskas GF, Ladd S, Bratcher SJ, Schroer RJ, Balsamo J, DuPont BR, et al. (2008). Alterations in CDH15 and KIRREL3 in patients with mild to severe intellectual disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 83, 703–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brautigam CA (2015). Calculations and Publication-Quality Illustrations for Analytical Ultracentrifugation Data. Methods Enzymol. 562, 109–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignall AC, and Cloutier J-F (2015). Neural map formation and sensory coding in the vomeronasal system. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 72, 4697–4709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brignall AC, Raja R, Phen A, Prince JEA, Dumontier E, and Cloutier J-F (2018). Loss of Kirrel family members alters glomerular structure and synapse numbers in the accessory olfactory bulb. Brain Struct. Funct 223, 307–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulchand S, Menon SD, George SE, and Chia W (2010). The intracellular domain of Dumbfounded affects myoblast fusion efficiency and interacts with Rolling pebbles and Loner. PLoS ONE 5, e9374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng S, Park Y, Kurleto JD, Jeon M, Zinn K, Thornton JW, and Özkan E (2019). Family of neural wiring receptors in bilaterians defined by phylogenetic, biochemical, and structural evidence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 9837–9842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chia PH, Chen B, Li P, Rosen MK, and Shen K (2014). Local F-actin network links synapse formation and axon branching. Cell 156, 208–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloutier J-F, Sahay A, Chang EC, Tessier-Lavigne M, Dulac C, Kolodkin AL, and Ginty DD (2004). Differential requirements for semaphorin 3F and Slit-1 in axonal targeting, fasciculation, and segregation of olfactory sensory neuron projections. J. Neurosci 24, 9087–9096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darriba D, Posada D, Kozlov AM, Stamatakis A, Morel B, and Flouri T (2020). ModelTest-NG: A New and Scalable Tool for the Selection of DNA and Protein Evolutionary Models. Mol. Biol. Evol 37, 291–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rubeis S, He X, Goldberg AP, Poultney CS, Samocha K, Cicek AE, Kou Y, Liu L, Fromer M, Walker S, et al. (2014). Synaptic, transcriptional and chromatin genes disrupted in autism. Nature 515, 209–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehal P, and Boore JL (2005). Two rounds of whole genome duplication in the ancestral vertebrate. PLoS Biol 3, e314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Punta K, Puche A, Adams NC, Rodriguez I, and Mombaerts P (2002). A divergent pattern of sensory axonal projections is rendered convergent by second-order neurons in the accessory olfactory bulb. Neuron 35, 1057–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoviel DB, Freed DD, Vogel H, Potter DG, Hawkins E, Barrish JP, Mathur BN, Turner CA, Geske R, Montgomery CA, et al. (2001). Proteinuria and perinatal lethality in mice lacking NEPH1, a novel protein with homology to NEPHRIN. Mol. Cell. Biol 21, 4829–4836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulac C, and Torello AT (2003). Molecular detection of pheromone signals in mammals: from genes to behaviour. Nat. Rev. Neurosci 4, 551–562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res 32, 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, and Cowtan K (2010). Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein P, and Mombaerts P (2004). A contextual model for axonal sorting into glomeruli in the mouse olfactory system. Cell 117, 817–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein P, Bozza T, Rodriguez I, Vassalli A, and Mombaerts P (2004). Axon guidance of mouse olfactory sensory neurons by odorant receptors and the beta2 adrenergic receptor. Cell 117, 833–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franke D, and Svergun DI (2009). DAMMIF, a program for rapid ab-initio shape determination in small-angle scattering. J. Appl. Cryst 42, 342–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel LR, Wu S, and Melikian HE (2014). Brain slice biotinylation: an ex vivo approach to measure region-specific plasma membrane protein trafficking in adult neurons. J. Vis. Exp 86, 51240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerke P, Huber TB, Sellin L, Benzing T, and Walz G (2003). Homodimerization and heterodimerization of the glomerular podocyte proteins nephrin and NEPH1. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 14, 918–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerke P, Sellin L, Kretz O, Petraschka D, Zentgraf H, Benzing T, and Walz G (2005). NEPH2 is located at the glomerular slit diaphragm, interacts with nephrin and is cleaved from podocytes by metalloproteinases. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol 16, 1693–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerke P, Benzing T, Höhne M, Kispert A, Frotscher M, Walz G, and Kretz O (2006). Neuronal expression and interaction with the synaptic protein CASK suggest a role for Neph1 and Neph2 in synaptogenesis. J. Comp. Neurol 498, 466–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harita Y, Kurihara H, Kosako H, Tezuka T, Sekine T, Igarashi T, and Hattori S (2008). Neph1, a component of the kidney slit diaphragm, is tyrosine-phosphorylated by the Src family tyrosine kinase and modulates intracellular signaling by binding to Grb2. J. Biol. Chem 283, 9177–9186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hisaoka T, Komori T, Kitamura T, and Morikawa Y (2018). Abnormal behaviours relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders in Kirrel3-knockout mice. Sci. Rep 8, 1408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins JB, Gillilan RE, and Skou S (2017). BioXTAS RAW: improvements to a free open-source program for small-angle X-ray scattering data reduction and analysis. J. Appl. Cryst 50, 1545–1553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber TB, Schmidts M, Gerke P, Schermer B, Zahn A, Hartleben B, Sellin L, Walz G, and Benzing T (2003). The carboxyl terminus of Neph family members binds to the PDZ domain protein zonula occludens-1. J. Biol. Chem 278, 13417–13421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara N, Nakashima A, Hoshina N, Ikegaya Y, and Takeuchi H (2016). Differential expression of axon-sorting molecules in mouse olfactory sensory neurons. Eur. J. Neurosci 44, 1998–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko-Goto T, Yoshihara S, Miyazaki H, and Yoshihara Y (2008). BIG-2 mediates olfactory axon convergence to target glomeruli. Neuron 57, 834–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]