Abstract

Background:

Low birth weight and prematurity are important risk factors for death and disability, and may be affected by prenatal exposure to household air pollution (HAP).

Methods:

We investigate associations between maternal exposure to carbon monoxide (CO) during pregnancy and birth outcomes (birth weight, birth length, head circumference, gestational age, low birth weight, small for gestational age, and preterm birth) among 1288 live-born infants in the Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study (GRAPHS). We evaluate whether evidence of malaria during pregnancy, as determined by placental histopathology, modifies these associations.

Results:

We observed effects of CO on birth weight, birth length, and gestational age that were modified by placental malarial status. Among infants from pregnancies without evidence of placental malaria, each 1ppm increase in CO was associated with reduced birth weight (−53.4 g [95% CI: −84.8, −21.9 g]), birth length (−0.3cm [−0.6, −0.1 cm]), gestational age (−1.0 days [−1.8, −0.2 days]), and weight-for-age Z score (−0.08 standard deviations [−0.16, −0.01 standard deviations]). These associations were not observed in pregnancies with evidence of placental malaria. Each 1ppm increase in maternal exposure to CO was associated with elevated odds of low birth weight (LBW, OR 1.14 [0.97, 1.33]) and small for gestational age (SGA, OR 1.14 [0.98, 1.32]) among all infants.

Conclusions:

Even modest reductions in exposure to HAP among pregnant women could yield substantial public health benefits, underscoring a need for interventions to effectively reduce exposure. Adverse associations with HAP were discernible only among those without evidence of placental malaria, a key driver of impaired fetal growth in this malaria-endemic area.

Introduction

Nearly two million deaths each year are attributable to infants born either low birth weight or preterm according to the most recent global burden of disease (GBD) estimates from 2019 (G. B. D. Risk Factors Collaborators 2020). Low birth weight (LBW) and preterm birth (PTB) increase the risk for childhood stunting and chronic disease later in life (McCormick 1985; Barker 1995; Christian et al. 2013), and rank among the top ten risk factors for lifelong death and disability, accounting globally for 178 million disability adjusted life years (DALYs) and 13% of all DALYs in sub-Saharan Africa (GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators 2017). While there has been progress over the past decade in reducing the rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes, the burden of disease remains unacceptably high and highlights a priority area for concerted public health efforts. As more than 91% of these deliveries with adverse outcomes occur in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Blencowe et al. 2019), it is critical to identify LMIC-relevant modifiable risk factors for impaired fetal growth and preterm birth.

Household air pollution (HAP) generated from the use of solid fuels has been associated with reductions in both birth weight and gestational length (Amegah, Quansah, and Jaakkola 2014; Haider et al. 2016; Khan et al. 2017; Suryadhi et al. 2019; Milanzi and Namacha 2017). With almost 3 billion people worldwide reliant on the use of solid biomass fuels to meet their daily cooking or heating needs (International Energy Agency et al. 2020), decreasing exposure to cooking smoke during pregnancy is an important public health goal that may translate into improved birth outcomes. Previous efforts to quantify the potential benefits from reduced prenatal cook smoke exposure have been limited by reliance on questionnaire data to classify exposure to biomass fuels in most prior publications. Few previous studies have incorporated exposure measurements to specific air pollutants and those that did were limited by relying on only a single measurement during pregnancy (Wylie et al. 2017), a small sample size (Thompson et al. 2011; Wylie et al. 2017; Alexander DA 2018), or use of kitchen area, rather than personal exposure, air pollution measurements (Balakrishnan et al. 2018; Chen et al. 2020). Many previous investigations also based outcome measurements like birth weight or gestational age on maternal self-report.

The analyses presented here are the results of pre-planned secondary analyses of the Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study (GRAPHS) trial (Jack et al. 2015), a randomized controlled trial of a prenatal cookstove intervention conducted in rural Ghana with repeated personal exposure assessments. Our primary objective in these analyses was to provide more accurate estimates of the risks associated with household air pollution during pregnancy on birth outcomes. We conducted exposure-response analyses quantifying the association of household air pollutants with birth outcomes: birth weight, birth length, head circumference, and gestational age. We also assessed associations with the dichotomized outcomes of low birth weight (LBW, <2,500 grams) preterm birth (PTB, <37 weeks), and small for gestational age (SGA, birth weight <10th percentile). We hypothesized that malarial infection during pregnancy might obscure the effects of prenatal household air pollution on birth outcomes given that malaria is endemic in the study area and such a strong risk factor for impaired fetal growth and preterm birth (Asante et al. 2013); therefore, we investigated malaria as a potential effect modifier of the exposure-response relationships. Our findings may inform policymakers of the potential public health benefits that might result from strategies to reduce prenatal air pollution exposure.

Methods

Study Participants

Participants were pregnant women enrolled in GRAPHS, a cluster-randomized cookstove intervention trial of an improved cookstove intervention (liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) stove or improved biomass stove) versus control in rural Ghana, that has been described previously (Jack et al. 2015). A total of 1,414 nonsmoking, pregnant women at or below 24 weeks’ gestation as determined by ultrasound were enrolled from communities in the Kintampo North Municipality and Kintampo South District of Ghana between June 2013 and June 2015. In addition to the randomized cookstove intervention, all women were provided with health insurance and insecticide-treated bednets upon enrollment. Procedures were approved by the Kintampo Health Research Centre Institutional Ethics Committee, the Ghana Health Service Ethics Review Committee, and Institutional Review Boards at Columbia University and Massachusetts General Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all pregnant women at study enrollment. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses from the GRAPHS trial did not show an impact of the improved cookstoves on birth outcomes (Jack et al., 2021); the results presented in this paper focus on a planned secondary exposure-response analysis of birth outcomes among the live births in this cohort.

Prenatal HAP Exposure

Exposure monitoring procedures have been described previously (Lee et al. 2018; Chillrud et al. 2021). Carbon monoxide was the primary air pollutant measured in GRAPHS. Briefly, pregnant women participated in four prenatal 72-hour personal CO monitoring sessions using a Lascar EL-CO-USB Data Logger (Erie, PA). The first monitoring session occurred at enrollment, prior to intervention, and was followed by three additional sessions after intervention evenly spaced over the remainder of each pregnancy. This measurement protocol was designed to provide the best possible estimate of long-term exposure to CO in pregnancy, within the constraints of budget and feasibility, see (Clark, Peel, et al. 2013). In a subset of GRAPHS participants (N=769), personal exposure to PM2.5 was collected during a single 72-hour exposure monitoring session during pregnancy (methods detailed in Supplemental Material). Data that did not pass quality assurance/quality control checks (see (Chillrud et al. 2021)) were considered missing.

As previously reported (Lee et al. 2018; Carrión et al. 2019), composite measures of exposure over pregnancy were developed using a linear interpolation approach. First, since only 47% of CO exposure deployments reached the targeted 72 hours but more than 90% reached 48 hours, each monitoring session was truncated at 48 hours to ensure that two complete daily cycles of cooking were captured. From each monitoring session, we calculated a summary measure (48-hour mean, see Supplemental Material for details). As four CO sessions occurred prenatally, this resulted in a series of 48-hour-average CO measurements at four different points in pregnancy. D aily average CO exposure during pregnancy was calculated using linear interpolation, wherein each day of pregnancy was assigned a putative CO exposure. The first day of pregnancy was back-calculated using ultrasound established dates at participant enrollment (see (Boamah et al. 2014b)). Any day in pregnancy that occurred prior to the first CO monitoring session was assigned the mean value from the first (baseline) CO monitoring session. CO exposures for the days between the first and second monitoring sessions were assigned by linearly interpolating between the two measured values. For example, if the 48-hour-mean on May 1 was measured at 2.0 ppm and on May 11 at 3.0 ppm, each of the ten days separating these two measurements would be assigned an estimate that was an additional 1/10 of the difference between the two measured values each day; thus, CO exposure on May 2 would be assigned a value of 2.1ppm, May 3 would be assigned 2.2 ppm, and so forth. A similar procedure was followed to assign CO exposures to the remaining days of pregnancy, with any days following the last monitoring session in pregnancy assigned the mean value from the latest monitoring session in pregnancy. This process yielded a time series of estimated CO exposure for each day of pregnancy, from which we computed an average prenatal exposure measure covering the entirety of the pregnancy.

Birth Outcomes

Maternal characteristics were collected by research personnel at GRAPHS enrollment (details in (Jack et al. 2015). Birth anthropometrics were recorded within 72 hours of delivery by community-based field workers even for home births, as previously described (Jack et al., 2021). Birth weight was measured to the nearest 0.01 kilogram (kg) using the Tanita BD 585 digital baby scale (Tokyo, Japan). Newborn length and head circumference were measured to the nearest 0.1 centimeter (cm) using the Ayrton Infantometer Model M-200 (Ayrton Corp, MN, USA) and a Lasso-o™ (Child Growth Foundation, UK), respectively. Gestational age at delivery was calculated by using the ultrasound estimated gestational age at enrollment, as described previously (Boamah et al. 2014a). LBW was defined as less than 2500g and PTB as delivery prior to 37 weeks of gestation. An infant was considered small for gestational age if born alive with a birth weight less than the 10th percentile for the specific gestational week at delivery after creating a Ghanaian specific curve using methodology described by the World Health Organization (Mikolajczyk et al. 2011). Weight-for-age Z scores were calculated according to the international newborn size standards developed by the International Fetal and Newborn Growth Consortium for the 21st Century (INTERGROWTH-21) (Villar et al. 2014). Any birth occurring prior to 28 weeks gestation was considered to be a miscarriage for the purposes of this study and was not included in the present analysis; any birth weight not measured within 72 hours of birth was also considered missing. Births occurring during the months of April, May, June, September, or October were classified as taking place during the high malaria transmission season (Asante et al. 2013). Malaria during pregnancy was determined by placental histopathology with both acute and chronic infections considered as evidence of prenatal infection.

Statistical Modeling

Model building for associations with CO (the primary pollutant measured in GRAPHS) and PM2.5 (measured in a subset of 769 women, with results reported in Supplemental Material) followed the same procedure. Associations between birth outcomes and the two exposure variables (CO and PM2.5) were separately modeled using linear regression for the continuous outcomes of birth weight, birth weight-for-age, birth length, head circumference, and gestational age at birth; and using logistic regression models for the binary outcomes of LBW, SGA, and PTB. Cluster-robust standard errors were calculated for all models using a sandwich estimator to account for the cluster-randomized nature of the GRAPHS trial.

Possible non-linear relationships between the exposures and the continuous outcomes were explored visually with generalized additive models (GAMs) using thin plate regression splines with 3 degrees of freedom to model smooth functions of exposure. Although exploration of these relationships suggested some deviations from linearity at high levels of exposure, few data points were collected at these higher levels of exposure and corresponding confidence intervals were wide. As the relationships at exposures representing over 95% of the data were largely linear (< 3.1ppm for CO and <209μg/m3 for PM2.5), we report our main results using linear and logistic regression models. We nonetheless present visualizations of exposure-response functions generated from the GAMs in Figures and the Supplemental Material.

Covariates for adjusted models were chosen a priori based on their known or hypothesized associations with the exposures and/or birth outcomes. These variables included maternal age, parity, maternal body mass index (at enrollment), maternal ethnicity, adequacy of antenatal care (ANC) visits (4 or more visits versus fewer), infant sex, and placental malaria. Questionnaires were used to assess household characteristics which were enumerated as counts (e.g., number of livestock) and used calculate the asset index, a socioeconomic status measure relative to other enrolled households (O’Donnell et al. 2008). Placental malaria and infant sex were also investigated as effect modifiers. Sensitivity analyses further adjusted for season of delivery (high vs. low malaria transmission season), the presence of a smoker in the household or compound, and history of maternal hypertension.

We tested for interaction on the additive scale in linear models by including interaction terms between CO/PM2.5 exposure and the variables of infant sex and placental malaria in adjusted models. For logistic models, we calculated the relative excess risk due to interaction (RERI, see (Knol et al. 2007)). Because we observed evidence of an interaction between placental malaria and CO exposure on birth weight and gestational age (see Results), we present all associations with CO both overall and stratified by placental malaria status.

Of the covariates included in adjusted models, placental malaria status was available for 1158 births, or 89.9% of the total (See Table 1). Primary reasons for missingness were the mother or health facility not saving the placenta (55 births) or identification of the birth more than 24 hours following delivery (51 births). Other covariates had small amounts of missingness (Table 1). As a sensitivity analysis we employed the Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) algorithm to generate 10 imputed datasets and compared the results from the multiple imputation to the complete case analysis (see Supplemental Material for further detail).

Table 1:

Baseline Characteristics of GRAPHS women

| All live births with available CO data (n = 1288) | Live births with available CO data and Placental Malaria status (n = 1158) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Placental Malaria Negative (n=878) | Placental Malaria Positive (n=280) | ||

| Age | |||

| Mean (SDa) | 27.6 (7.2) | 29.1 (6.8) | 23.2 (6.3) |

| Range | 14.0 – 48.0 | 15.0 – 48.0 | 14.0 – 41.0 |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| BMI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 23.3 (3.2) | 23.4 (3.3) | 22.9 (3.0) |

| Range | 14.1 – 38.5 | 14.1 – 38.5 | 16.4 – 35.2 |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Parity | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.7 (2.2) | 3.2 (2.1) | 1.3 (1.7) |

| Range | 0.0 – 13.0 | 0.0 – 13.0 | 0.0 – 9.0 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asset Index | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.0 (2.0) | 0.0 (2.0) | 0.1 (2.0) |

| Range | -3.0 - 13.1 | -3.0 - 13.1 | -2.8 - 11.4 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gestational Age at Enrollment (weeks) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 15.7 (4.3) | 15.7 (4.4) | 16.0 (4.3) |

| Range | 6.0 - 26.0 | 6.0 - 24.0 | 6.0 - 25.0 |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Smoker in Household or Compound | |||

| Yes | 269 (20.9%) | 174 (19.8%) | 62 (22.1%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| History of Anaemia | |||

| Yes | 28 (2.2%) | 22 (2.5%) | 3 (1.1%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| History of Hypertension | |||

| Yes | 17 (1.3%) | 13 (1.5%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| History of Diabetes | |||

| Yes | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| History of HIV | |||

| Yes | 1 (0.1%) | 1 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Completed Primary Education | |||

| Yes | 765 (59.4%) | 474 (54.0%) | 202 (72.1%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Is Married | |||

| Yes | 718 (55.7%) | 546 (62.2%) | 107 (38.2%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4+ ANC Visits | |||

| Yes | 896 (69.9%) | 599 (68.6%) | 201 (72.0%) |

| Missing | 7 | 5 | 1 |

| Ethnicity b | |||

| 1 | 220 (17.1%) | 159 (18.1%) | 36 (12.9%) |

| 2 | 169 (13.1%) | 102 (11.6%) | 44 (15.7%) |

| 3 | 842 (65.4%) | 577 (65.7%) | 191 (68.2%) |

| 4 | 57 (4.4%) | 40 (4.6%) | 9 (3.2%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prenatal CO exposure (ppm) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.9) |

| Median | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Range | 0.0 - 6.7 | 0.0 - 6.6 | 0.1 - 6.7 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Prenatal PM exposure (μg/m3) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 85.5 (58.8) | 84.2 (56.6) | 87.8 (63.1) |

| Median | 69.1 | 67.6 | 75.1 |

| Range | 6.4 - 414.2 | 6.4 - 328.2 | 14.0 - 414.2 |

| Missing | 544 | 366 | 129 |

SD = standard deviation

Ethnicity groups are coded as dummy variables to preserve participant anonymity

All statistical modeling was conducted using R version 3.5.1. GAMs were constructed with the “mcgv” package (Wood 2017) and multiple imputation was conducted using the “mice” package (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn 2011).

Results

Participant Characteristics

There were 1306 live births at 28+ weeks of gestation among the 1414 enrolled GRAPHS women. Of these, the 1288 with valid maternal prenatal CO exposure data comprise our analytic population (Table 1). The average age of women in this cohort was 27.6 years, with 2.7 prior births on average. Average gestational age at enrollment was 15.7 weeks (range: 6.0 – 26.0 weeks). Just over half of the women (718, 55.7%) were married, and 765 (59.4%) had completed at least primary education. Just over 20% reported that a smoker lived in their household or compound. Few participants reported a history of anemia (2.2%), hypertension (1.3%), diabetes (0.1%), or HIV (0.1%) at the time of enrollment. Over two-thirds (69.9%) of the women reported attending at least 4 antenatal visits during pregnancy.

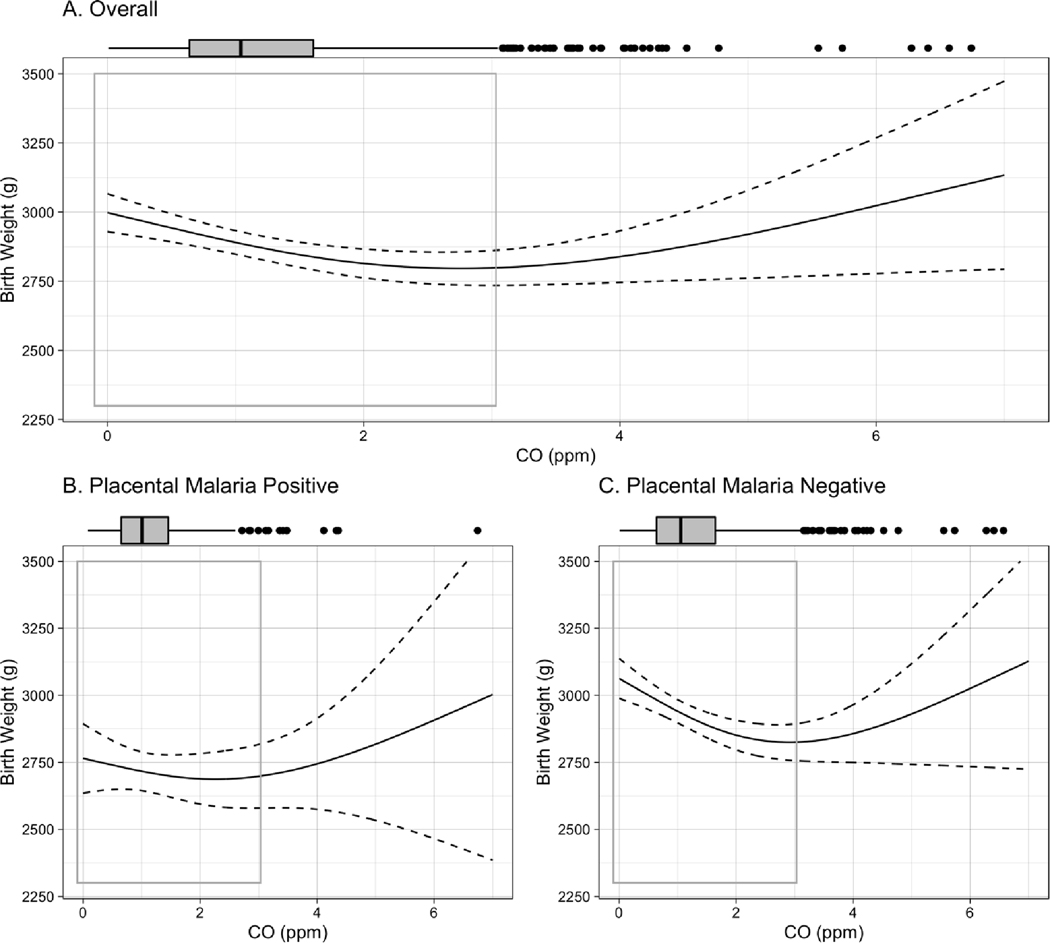

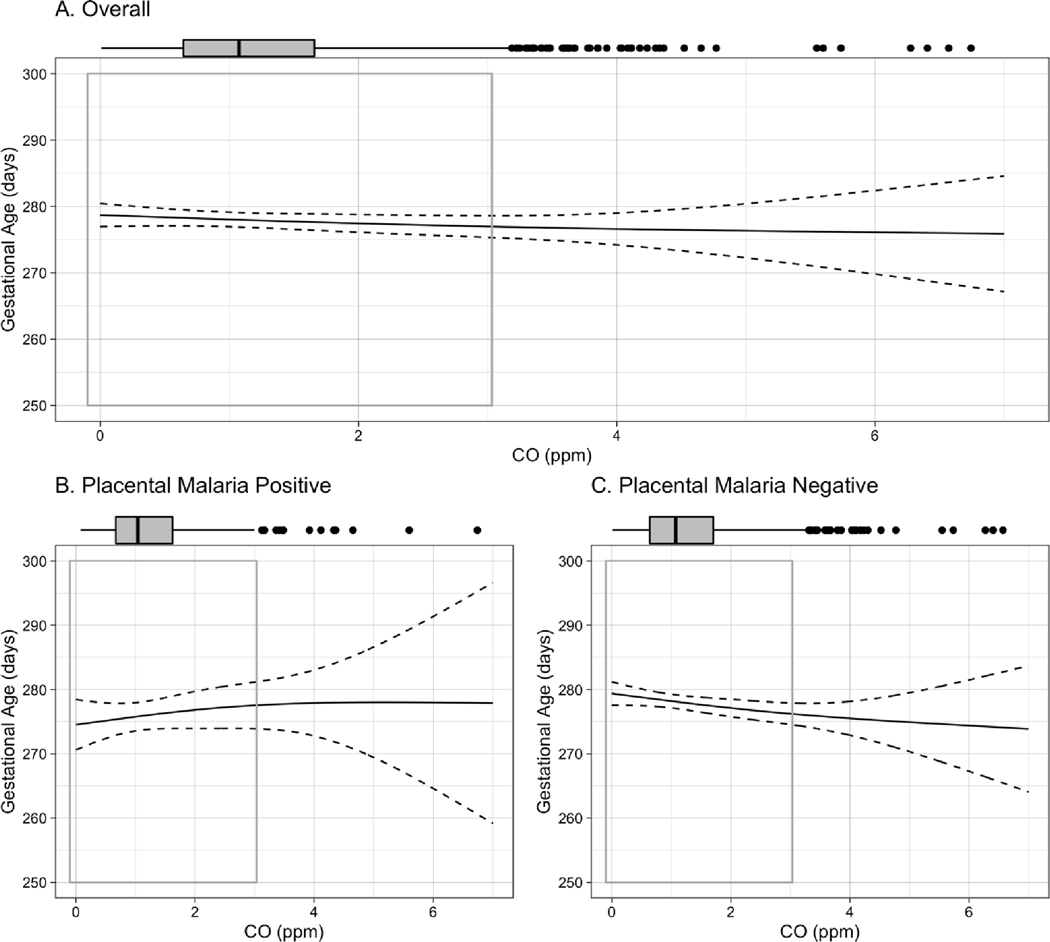

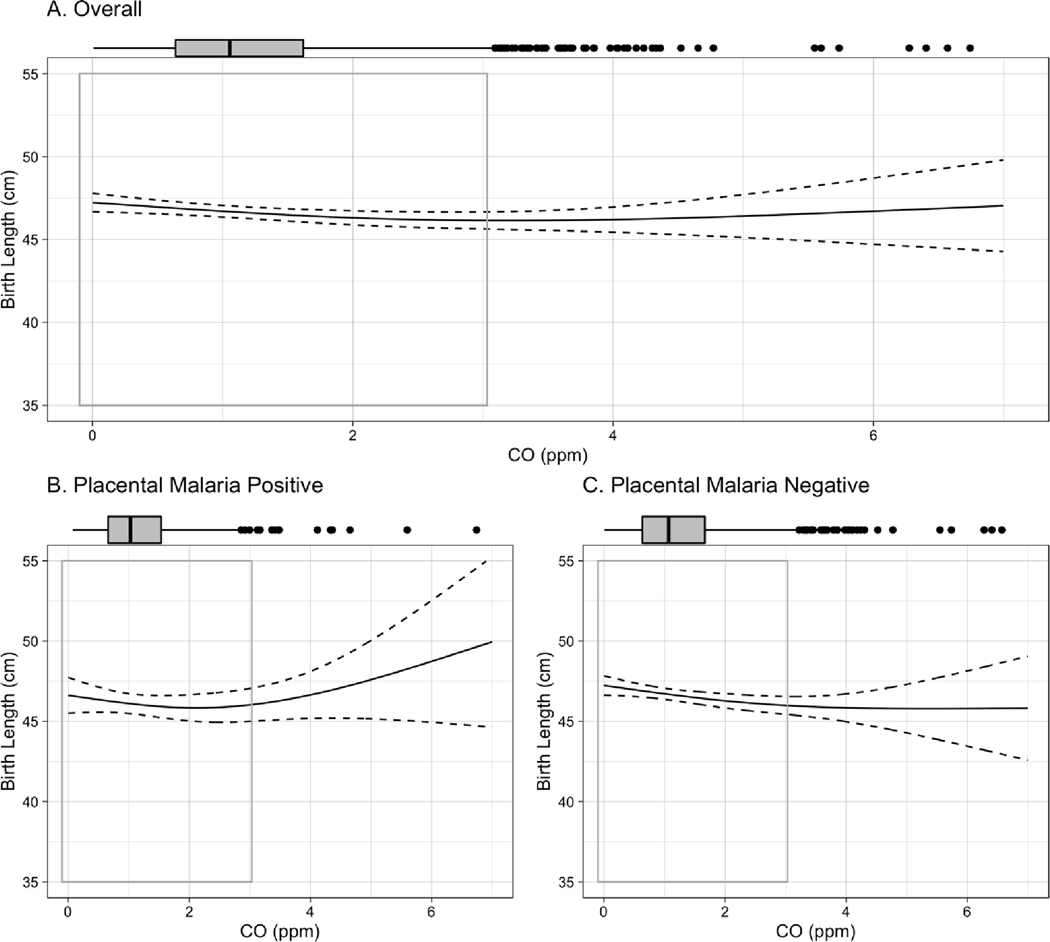

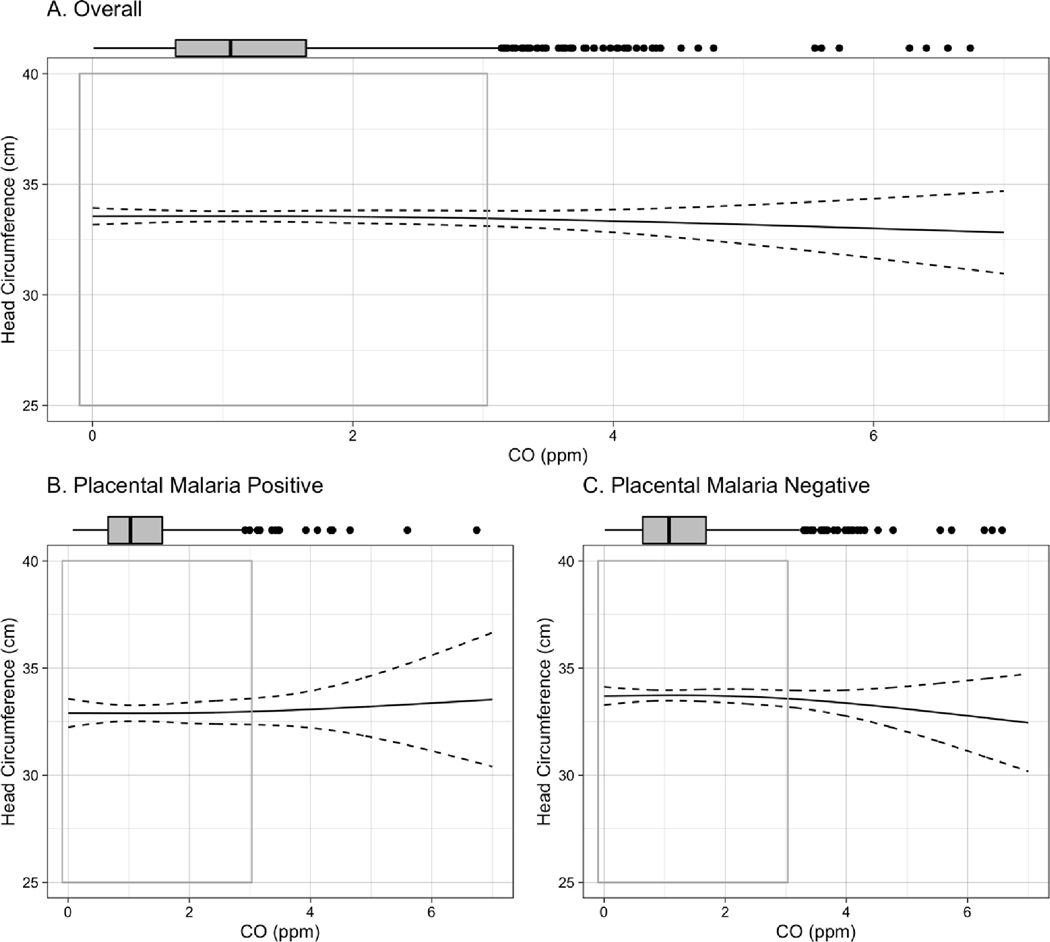

CO and PM2.5 exposure during pregnancy

Distributions of CO and PM2.5 indicate that 95% of women averaged exposure to CO below 3.1 ppm and to PM2.5 below 209μg/m3. A small number had substantially higher exposures (see boxplots in Figures 1–4 and S1–S4). Mean (standard deviation; SD) prenatal exposure was 1.3 (0.9) ppm for CO and 85.5 (58.8) μg/m3 for PM2.5 (Table 1). Prenatal CO and PM2.5 were weakly correlated (r = 0.23, p < 0.01). Based on analysis of regression diagnostics, we set four extreme CO outliers (> 8ppm) to missing. These points were more than six times the interquartile range from the 75th percentile of the overall distribution of CO data, and three of these points were also causing undue influence on the model results. Prenatal exposure to CO was similar among those with and without placental malaria (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Exposure-response curve for CO-birth weight association among A. all live births, B. live births to women testing positive for placental malaria, C., live births to women testing negative for placental malaria. Curves are built from generalized additive models (GAMs) using thin plate regression splines with 3 degrees of freedom, adjusted for maternal BMI, age, parity, asset index, ANC visits, ethnicity, and infant sex. Boxplots demonstrate the distribution of exposure, while gray-outlined boxes demarcate the exposure range covering 95% of the data. P-value for interaction between CO and placental malaria: 0.02.

Figure 4.

Exposure-response curve for CO-gestational age association among A. all live births, B. live births to women testing positive for placental malaria, C., live births to women testing negative for placental malaria. Curves are built from generalized additive models (GAMs) using thin plate regression splines with 3 degrees of freedom, adjusted for maternal BMI, age, parity, asset index, ANC visits, ethnicity, and infant sex. Boxplots demonstrate the distribution of exposure, while gray-outlined boxes demarcate the exposure range covering 95% of the data. P-value for interaction between CO and placental malaria: <0.001.

Birth Outcomes

The mean (SD) birth weight in this cohort was 2892.0 (455.1) g, average birth length was 46.6 (3.6) cm, and average head circumference was 33.5 (2.5) cm (Table 2). The mean gestational age at delivery was 39.6 (1.6) weeks. 3.9% of the births were classified as preterm, 17.0% as LBW, and 22.4% as SGA. As expected, infants born to women with evidence of placental malaria (280 out of 1158 women, or 24.2%) were on average lighter and smaller at delivery, and gestation slightly shorter, than those born to women with no evidence of placental malaria (Table 2). Accordingly, a higher proportion of infants born to women testing positive for malaria were classified as LBW, SGA, and PTB. These infants were also more likely to be born during the high malaria transmission season.

Table 2.

Birth Outcomes

| All live births with available CO data (n = 1288) | Live births with available CO data and Placental Malaria Status (n = 1158) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Placental Malaria Negative (n=878) | Placental Malaria Positive (n=280) | ||

| Birthweight (grams) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2892.0 (455.1) | 2933.4 (450.0) | 2764.4 (449.8) |

| IQR | 560.0 | 527.5 | 540.0 |

| Missing | 39 | 0 | 2 |

| Birth Length (cm) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 46.6 (3.6) | 46.6 (3.5) | 46.0 (3.6) |

| IQR | 4.3 | 4.0 | 4.7 |

| Missing | 24 | 11 | 4 |

| Head Circumference (cm) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 33.5 (2.5) | 33.6 (2.5) | 33.0 (2.2) |

| IQR | 3.0 | 3.0 | 2.5 |

| Missing | 36 | 18 | 8 |

| Gestational Age at Delivery (weeks) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 39.6 (1.6) | 39.7 (1.5) | 39.3 (1.8) |

| IQR | 1.7 | 1.7 | 1.9 |

| Missing | 15 | 9 | 5 |

| Weight-for-age Z Score (standard deviations) | |||

| Mean (SD) | -0.9 (1.0) | -0.8 (1.0) | -1.1 (1.1) |

| IQR | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Missing | 66 | 19 | 8 |

| Preterm Birth | |||

| Yes | 50 (3.9%) | 28 (3.2%) | 17 (6.1%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Low Birth Weight | |||

| Yes | 212 (17.0%) | 125 (14.2%) | 67 (24.1%) |

| Missing | 39 | 0 | 2 |

| Small for Gestational Age | |||

| Yes | 277 (22.4%) | 168 (19.3%) | 84 (30.8%) |

| Missing | 54 | 9 | 7 |

| Delivery during high malaria transmission season | |||

| Yes | 562 (43.6%) | 358 (40.8%) | 138 (49.3%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Male Sex | |||

| Yes | 655 (50.9%) | 453 (51.6%) | 131 (46.8%) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Effects of prenatal CO on Birth Outcomes

We observed a statistically significant interaction between CO exposure and placental malaria for two continuous outcomes: birth weight (p-value for interaction 0.02) and gestational age (p-value for interaction <0.001). Although results were suggestive of similar trends for the other birth outcomes, p-values for these interactions were not significant (all p-values > 0.1). Nonetheless, due to the strong effect of placental malaria on all the studied outcomes, and the relationship of birth weight and/or gestational length with other categorical birth outcomes of interest, we present all results in two ways: among all infants, and stratified by placental malaria. There was no evidence of effect modification by infant sex.

In the overall cohort, each 1ppm increase in maternal exposure to CO during pregnancy was associated with a mean [95% CI] reduction of −38.7 [−66.2, −11.1] g in birth weight, −0.3 [−0.5, −0.02] cm in birth length, −0.5 [−1.3, 0.2] days of gestational age, and −0.07 [−0.1, −0.01] standard deviation of weight-for-age Z score (Table 3) in adjusted analyses. Notably, results stratified by placental malaria demonstrate that all of these associations were stronger among infants born to placental malaria-negative women. In the placental malaria-negative group, each 1ppm increase in maternal exposure to CO was associated with a mean [95% CI] reduction of −53.4 [−84.8, −21.9] g in birth weight; −0.3 [−0.6, −0.1] cm in birth length; −1.0 [−1.8, −0.2] days of gestational age; and −0.08 [−0.16, −0.01] standard deviations of weight-for age Z score. The stratified results do not demonstrate associations between CO and these outcomes among infants born to women with placental malaria. No association between CO exposure and newborn head circumference was observed in either overall or stratified analysis.

Table 3.

Associations of prenatal CO exposure with birth outcomes

| Overall Adjusted Modela | Stratified by Placental Malaria Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient per 1ppm CO | 95% CI | Placental Malaria Status | Coefficient per 1ppm CO | 95% CI | N | |

| Birth Weight (g) | -38.7 | (−66.2, −11.1) | Negative | -53.4 | (−84.8, −21.9) | 1147 |

| Positive | 8.0 | (−47.8, 63.9) | ||||

| Birth Length (cm) | -0.3 | (−0.5, −0.02) | Negative | -0.3 | (−0.6, −0.1) | 1135 |

| Positive | 0.04 | (−0.4, 0.5) | ||||

| Head Circumference (cm) | -0.05 | (−0.2, 0.1) | Negative | -0.1 | (−0.3, 0.1) | 1124 |

| Positive | 0.05 | (−0.3, 0.4) | ||||

| Gestational age (days) | -0.5 | (−1.3, 0.2) | Negative | -1.0 | (−1.8, −0.2) | 1136 |

| Positive | 1.0 | (−0.4, 2.4) | ||||

| Weight-for-age Z score (standard deviations) | -0.07 | (−0.1, −0.01) | Negative | -0.08 | (−0.16, −0.01) | 1123 |

| Positive | -0.04 | (−0.17, 0.09) | ||||

| Odds ratio (OR) per 1ppm CO | 95% CI | Placental Malaria Status | OR per 1ppm CO | 95% CI | N | |

| Low Birth Weight | 1.14 | (0.97, 1.33) | Negative | 1.16 | (0.96, 1.41) | 1147 |

| Positive | 1.08 | (0.80, 1.46) | ||||

| Small for Gestational Age | 1.14 | (0.98, 1.32) | Negative | 1.09 | (0.91, 1.30) | 1134 |

| Positive | 1.28 | (0.97, 1.68) | ||||

| Preterm Birth | 0.92 | (0.71, 1.2) | Negative | 1.13 | (0.77, 1.66) | 1149 |

| Positive | 0.52 | (0.23, 1.20) | ||||

Covariates included in adjusted models: maternal BMI, maternal age, parity, infant sex, ANC visits, ethnicity, asset index, and placental malaria.

Exposure-response curves for birth weight, birth length, head circumference, and gestational age, stratified by placental malaria, can be seen in Figures 1–4. Most of the distribution of exposure in GRAPHS women is at the lower end of the exposure range, with 95% of values < 3.1ppm. In this CO range, the near-linear reductions associated with CO are most clearly visible, as are the interactions by placental malaria. The shape of the curves above 3.1ppm CO should be interpreted with caution as they represent only 5% of the observed data and confidence intervals are wide.

Results for the dichotomized outcomes of LBW, SGA, and PTB suggested that the effects of CO on birth weight and gestational age translated to higher odds of LBW and SGA. Among all infants, the odds were 14% [95% CI: −3%, 33%] higher for LBW and 14% [−2%, 32%] higher for SGA, per 1ppm increase in prenatal maternal CO exposure (Table 3). Stratified results suggest that the effect for LBW may be stronger among infants born to pregnant women without histologic evidence of placental malaria. Few infants (50, or 3.9% of the total) were classified as preterm in this cohort, and no discernable association was observed between CO and PTB (OR 0.92 [95% CI: 0.71, 1.20]). Results stratified by placental malaria nonetheless suggest that the odds of this outcome were greater among infants born to women testing negative for placental malaria than in those testing positive (OR 1.13 [95% CI 0.77, 1.66] for those in the malaria-negative group versus 0.52 [95% CI 0.23, 1.20] for the placental malaria-positive).

Secondary Analyses

Results from adjusted models including an expanded set of covariates (malaria transmission season, smoker in household or compound, history of hypertension) did not result in substantially different effect estimates (results not shown). Likewise, the results of pooled analysis of 10 multiply-imputed datasets using available covariates to predict missing values across our data were similar to the results of the complete-case analysis. The results of the analysis with multiply imputed data can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Associations were also explored in the smaller subset of infants whose mothers had prenatal PM2.5 monitoring (n ~ 667 in adjusted analyses). We did not observe associations between prenatal PM2.5 and any of the continuous outcomes; we also did not observe evidence of interaction by placental malaria status in this subset. Results for these analyses are shown in the Supplemental Material.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest that reducing CO exposure could yield important health benefits beginning in utero. Notably, a 1 ppm reduction in prenatal CO exposure in women not affected by placental malaria was associated with an increase in birth weight of over 50 grams, a clinically significant increase that could have positive implications for health over the life course. We observed that the negative effect of CO on birth weight was accompanied by small effects on birth length and gestational age. The fact that weight-for-age Z score, which takes into account infant sex and gestational age at delivery in relation to the birth weight, was also associated with CO exposure suggests that the reduction in birth weight that we observed to be associated with CO was not driven entirely by births at an earlier gestational age. Rather, it suggests that CO exposure may be implicated not only in the length of gestation but also in other, as yet unknown, factors affecting fetal growth in utero. The fact that these associations were observed only among the group testing negative for placental malaria suggests that malaria during pregnancy may obscure the effects of HAP on birth outcomes.

In this cohort, 73% of women reported a primary cooking location that was fully outside, see (Chillrud et al. 2021). Our findings therefore suggest that reductions in HAP can have important health benefits even in settings where exposures are moderate due to the prevalence of outdoor cooking. At baseline, personal exposure to CO in this cohort was 1.6ppm (Quinn et al. 2016); after half of the women were randomized to intervention, overall CO exposure over pregnancy dropped to 1.3 ppm. These values are slightly lower than the estimates from a meta-analysis of eight studies of cookstove interventions on personal exposure to CO, where the pooled pre-intervention mean personal exposure to CO was 3.4ppm, falling to 1.6ppm post-intervention (Pope et al. 2017). Several previously published interventional studies, however, have reported similar CO exposures to those reported here: a study in rural Kenya reported mean 48-hour personal CO exposure of 1.3 ppm among women using traditional stoves and improved stoves (Yip et al. 2017); and a study in Nicaragua reported pre- and post-intervention exposures of 2.1ppm and 0.8ppm, respectively (Clark, Bachand, et al. 2013).

Only two prior studies have published exposure-response results for birth outcomes in relation to HAP exposure. In a cohort of 239 pregnant women in Tanzania, there was a negative association between CO exposure and newborn birth weight, but results were not statistically significant (Wylie et al. 2017). This study also reported a 150g [95% CI: −300, 0g] reduction in birth weight per 23.0 μg/m3 increase in PM2.5. The second study, among 1285 women in the Tamil Nadu region of India, reported a 4 g (95% CI: 1.08, 6.76) decrease in birth weight and 2% increase in the prevalence of LBW (95%CI: 0.05%, 4.1%) for each 10 μg/m3 increase in kitchen area PM2.5 measured during pregnancy (Balakrishnan et al. 2018). This study did not assess personal exposure to PM2.5 and did not measure CO. In the present study, our measurements of PM2.5 during pregnancy were limited, as this exposure was measured only once during gestation and only in a subset of women. The fact that we did not find associations between PM2.5 exposure and newborn size here may be driven by these factors; we suggest these findings be interpreted with caution. As the research discussed above suggests, there are reasons to believe that reducing PM2.5 exposure during pregnancy may have beneficial effects for newborn size and health. Although there may be mechanistic reasons why CO may impact fetal growth independently of PM2.5, HAP is a complex mixture comprised of multiple particulate and gaseous pollutants. At the present time it is difficult to determine which constituents of HAP are the most deleterious to health, as many of them remain difficult to measure and track under real-world conditions. Luckily, cleaner cooking interventions that reduce exposure to the products of incomplete combustion will reduce exposure to all these noxious air pollutants simultaneously. If effective, these interventions have the potential to greatly improve newborn health even as further research is needed to determine the specific biochemical mechanisms underlying the effects.

The results presented here demonstrate exposure-response effects of reduced HAP on important birth outcomes and provide additional depth to the findings of the GRAPHS trial. In intention-to-treat analyses of the GRAPHS trial’s cookstove interventions, infants born in the LPG arm and the improved biomass arm had statistically indistinguishable birth weights as compared to those in the control arm on average, see (Jack et al., 2021). Other trials of cookstove interventions to improve birth outcomes have had mixed outcomes: an improved biomass cookstove in a cohort of 174 infants in Guatemala was associated with 89 g higher birth weight [95% CI: –27, 204 g] among 174 infants in adjusted analysis (Thompson et al. 2011), and a clean-burning ethanol stove intervention in Nigeria was associated with 128 g higher birth weight [95% CI: 20, 236 g] among 258 infants in adjusted analysis (Alexander DA 2018). Meanwhile, neither an improved biomass nor an LPG stove improved birth outcomes in two linked trials together covering almost 3000 individuals in southern Nepal (Katz et al. 2020).

In GRAPHS, we hypothesize that the stove interventions, by themselves, did not reduce exposures reliably enough for the intervention groups to realize group-wise benefits to birth outcomes. Only the LPG arm demonstrated a groupwise reduction in CO of 47% (95% CI: 36%, 56%) as compared to control, while the improved biomass arm did not differ from controls in terms of CO exposure (Chillrud et al. 2021). Still, the large majority (82%) of post-intervention mean 48-hour PM2.5 exposures exceeded the World Health Organization (WHO) interim-1 guideline of 35 μg/m3 even among the LPG arm (67%). Other trials that have provided individuals with clean cookstoves have also reported smaller than expected exposure reductions, e.g., no significant differences in PM2.5 exposure between the ethanol and control arms in Nigeria (Alexander DA 2018), and pollution levels much higher than WHO standards in intervention households in Nepal (Katz et al. 2020). It is possible that more comprehensive, community-level approaches may be required to reliably reduce exposure in settings where cooking with biomass fuels is commonplace. It is also possible that the timing of the intervention during pregnancy matters. In GRAPHS, women were midway through gestation when the intervention was delivered. More research is needed on potentially sensitive windows for the effect of HAP on fetal development to determine if interventions earlier in gestation are important to achieving health results.

In this malaria-endemic setting in Ghana, evidence of malaria was detected in the placentas of 24.2% of women (279 births), slightly lower than the 38% reported in a prior study of pregnant women in this region (Asante et al. 2013). Placental malaria is known to be a primary risk factor for reduced birth weight (Guyatt and Snow 2001, 2004), and found to be responsible for 19% (lower to upper quartile: 14–25%) of LBW cases in a review of studies in sub-Saharan African settings (Guyatt and Snow 2004). Despite this, few previous studies of the effect of HAP on birth weight have taken place in settings with high malaria enemicity, and to our knowledge none has assessed placental malaria. We found that the effects of exposure to CO on birth weight, birth length, and gestational length was observable only among women who did not have evidence of placental malaria (with similar trends observed in stratified results for the other birth outcomes). We hypothesize that the negative consequences of placental malaria on fetal growth may overwhelm the effect of exposure to HAP in the women who had evidence of placental malaria. This suggests that the benefits of reducing HAP exposure on birth outcomes may only be observable in the absence of the competing effects of malaria. Our findings of effect modification of HAP by placental malaria status underscore the importance of accounting for malaria in studies of HAP and health outcomes in settings where malaria is endemic, as associations may be masked or attenuated if this effect is not assessed.

Our study has many strengths. These include the large sample size of 1288 mother-infant dyads and the parent study’s randomization of cookstove interventions, with its accompanying detailed protocols to precisely measure exposure, outcomes, and covariates. This study also benefitted from ultrasound assessment of gestational age; the use of state-of-the-science personal exposure monitoring methods, including repeated personal CO measurements during pregnancy and filter-calibrated PM2.5 monitors; and histopathologic assessment of malaria in placental samples.

Limitations of the study include imperfect assessment of HAP exposure over pregnancy, particularly in its earliest weeks of pregnancy. As study enrollment occurred around the time of antenatal care establishment at 10+ weeks of gestation, HAP exposure measures early in pregnancy were not available. PM2.5 exposure assessment was further limited to a single 72-hour monitoring campaign in a subset of enrolled women and this may account for our null findings with PM2.5. Despite these limitations, to our knowledge this is the most thorough assessment of HAP exposure (a planned 4 measurements of CO per participant) during pregnancy yet reported, and one of the only extant studies to publish exposure-response results for HAP constituents in relation to birth outcomes.

Conclusions

In this study, exposure to carbon monoxide during pregnancy in a cohort of rural, nonsmoking Ghanaian women was associated with adverse impacts on infant weight, length, and gestational age at birth, with evidence that associations were stronger in the absence of placental malaria. These findings strongly suggest that reductions in air pollution exposure in pregnancy could improve birth outcomes in low- and middle-income countries, where cooking with biomass fuels is common.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Exposure-response curve for CO-birth length association among A. all live births, B. live births to women testing positive for placental malaria, C., live births to women testing negative for placental malaria. Curves are built from generalized additive models (GAMs) using thin plate regression splines with 3 degrees of freedom, adjusted for maternal BMI, age, parity, asset index, ANC visits, ethnicity, and infant sex. Boxplots demonstrate the distribution of exposure, while gray-outlined boxes demarcate the exposure range covering 95% of the data. P-value for interaction between CO and placental malaria: 0.14.

Figure 3.

Exposure-response curve for CO-head circumference association among A. all live births, B. live births to women testing positive for placental malaria, C., live births to women testing negative for placental malaria. Curves are built from generalized additive models (GAMs) using thin plate regression splines with 3 degrees of freedom, adjusted for maternal BMI, age, parity, asset index, ANC visits, ethnicity, and infant sex. Boxplots demonstrate the distribution of exposure, while gray-outlined boxes demarcate the exposure range covering 95% of the data. P-value for interaction between CO and placental malaria: 0.33.

Highlights:

Household air pollution exposure during pregnancy affects birth outcomes in Ghana.

Effects are strongest in pregnancies unaffected by placental malaria.

Carbon monoxide during pregnancy is associated with reduced fetal growth.

Carbon monoxide during pregnancy is also associated with shorter gestational age.

Malaria during pregnancy may obscure the effects of air pollution on fetal growth.

Acknowledgments

Funding: GRAPHS was supported by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) Grants R01 ES019547 and P30 ES009089, Thrasher Research Fund, and the Global Alliance for Clean Cookstoves. BJW was additionally supported by the NIEHS K23 ES021471 and R01 ES028688. AGL was additionally supported by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute K23 HL135349 and R01MD013310. CFG received support from NIEHS grants T32 ES023770 and F31 ES03183. DC is supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development T32HD049311.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. National Institutes of Health or Department of Health and Human Services.

Author statement

| Author r Order | First name | Last name | Contributions | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ashlinn | Quinn | Data curation, formal analysis, methodology, writing-original draft | |

| 2 | Irene Apewe | Adjei | Investigation | |

| 3 | Kenneth | Ae-Ngibise | Investigation, supervision | |

| 4 | Oscar | Agyei | Data curation | |

| 5 | Ellen | Boamah | Investigation | |

| 6 | Katrin | Burkhart | Data curation, visualization, writing – review & editing | |

| 7 | Daniel | Carrión | Methodology, writing – review & editing | |

| 8 | Steven | Chillrud | Methodology, supervision, writing – review & editing | |

| 9 | Carlos | Gould | Data curation, writing – review & editing | |

| 10 | Stephaney | Gyaase | Data curation | |

| 11 | Darby | Jack | Conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing – review & editing | |

| 12 | Seyram | Kaali | Investigation, Writing – review & editing | |

| 13 | Patrick | Kinney | Conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, methodology, writing – review & editing | |

| 14 | Alison | Lee | Writing – review & editing | |

| 15 | Mohammed | Mujtaba | Investigation, supervision | |

| 16 | Felix | Oppong | Investigation | |

| 17 | Seth | Owusu-Agyei | Conceptualization | |

| 18 | Abena | Yawson | Investigation | |

| 19 | Blair | Wylie* | Conceptualization, methodology, writing – review & editing, supervision | |

| 20 | Kwaku Poku | Asante* | Conceptualization, methodology, writing – review & editing, supervision, project administration |

Declaration of interests

☒ The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alexander DA, et al. 2018. “Pregnancy outcomes and ethanol cook stove intervention: A randomized-controlled trial in Ibadan, Nigeria. - PubMed - NCBI.” Environ Int 111:152–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amegah AK, Quansah R, and Jaakkola JJK 2014. “Household Air Pollution from Solid Fuel Use and Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Empirical Evidence.” PLoS One 9 (12):e113920. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante Kwaku Poku, Seth Owusu-Agyei Matthew Cairns, Dodoo Daniel, Ellen Abrafi Boamah Richard Gyasi, Adjei George, Gyan Ben, Akua Agyeman-Budu Theophilus Dodoo, Mahama Emmanuel, Amoako Nicholas, David Kwame Dosoo Kwadwo Koram, Greenwood Brian, and Chandramohan Daniel. 2013. “Placental malaria and the risk of malaria in infants in a high malaria transmission area in ghana: a prospective cohort study.” The Journal of infectious diseases 208 (9):1504–1513. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakrishnan Kalpana, Ghosh Santu, Thangavel Gurusamy, Sambandam Sankar, Mukhopadhyay Krishnendu, Puttaswamy Naveen, Sadasivam Arulselvan, Ramaswamy Padmavathi, Johnson Priscilla, Kuppuswamy Rajarajeswari, Natesan Durairaj, Maheshwari Uma, Natarajan Amudha, Rajendran Gayathri, Ramasami Rengaraj, Madhav Sathish, Manivannan Saraswathy, Nargunanadan Srinivasan, Natarajan Srinivasan, Saidam Sudhakar, Chakraborty Moumita, Balakrishnan Lingeswari, and Thanasekaraan Vijayalakshmi. 2018. “Exposures to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and birthweight in a rural-urban, mother-child cohort in Tamil Nadu, India.” Environmental Research 161:524–531. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. 1995. “Fetal Origins of Coronary Heart Disease.” BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 311 (6998). doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.6998.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blencowe H, Krasevec J, de Onis M, Black RE, An X, Stevens GA, Borghi E, Hayashi C, Estevez D, Cegolon L, Shiekh S, Ponce Hardy V, Lawn JE, and Cousens S. 2019. “National, regional, and worldwide estimates of low birthweight in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis.” The Lancet. Global health 7 (7). doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30565-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boamah EA, Asante K, Ae-Ngibise K, Kinney PL, Jack DW, Manu G, Azindow IT, Owusu-Agyei S, and Wylie BJ. 2014a. “Gestational Age Assessment in the Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study (GRAPHS):... - Abstract - Europe PMC.” JMIR Res Protoc 3 (4):e77. doi: http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC4376157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boamah EA, Asante K, Ae-Ngibise K, Kinney PL, Jack DW, Manu G, Azindow IT, Owusu-Agyei S, and Wylie BJ. 2014b. “Gestational Age Assessment in the Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study (GRAPHS): Ultrasound Capacity Building, Fetal Biometry Protocol Development, and Ongoing Quality Control.” JMIR Res Protoc 3 (4):e77. doi: http://europepmc.org/articles/PMC4376157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrión Daniel, Kaali Seyram, Kinney Patrick L., Seth Owusu-Agyei Steven Chillrud, Yawson Abena K., Quinn Ashlinn, Wylie Blair, Kenneth Ae-Ngibise Alison G. Lee, Tokarz Rafal, Iddrisu Luisa, Jack Darby W., and Asante Kwaku Poku. 2019. “Examining the relationship between household air pollution and infant microbial nasal carriage in a Ghanaian cohort.” Environment International 133:105150. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Chen, Zeger Scott, Breysse Patrick, Katz Joanne, Checkley William, Curriero Frank C., and Tielsch James M. 2020. “Estimating Indoor PM2.5 and CO Concentrations in Households in Southern Nepal: The Nepal Cookstove Intervention Trials.” doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chillrud, Steven N, Kenneth Ayuurebobi Ae-Ngibise, Gould Carlos F., Owusu-Agyei Seth, Mujtaba Mohammed, Manu Grace, Burkart Katrin, Kinney Patrick L., Quinn Ashlinn, Jack Darby W., and Asante Kwaku Poku. 2021. “The effect of clean cooking interventions on mother and child personal exposure to air pollution: results from the Ghana Randomized Air Pollution and Health Study (GRAPHS).” J Expo Sci Environ Epidemiol. doi: 10.1038/s41370021-00309-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian P, Lee SE, Donahue Angel M, Adair LS, Arifeen SE, Ashorn P, Barros FC, Fall CH, Fawzi WW, Hao W, Hu G, Humphrey JH, Huybregts L, Joglekar CV, Kariuki SK, Kolsteren P, Krishnaveni GV, Liu E, Martorell R, Osrin D, Persson LA, Ramakrishnan U, Richter L, Roberfroid D, Sania A, Kuile FO, Tielsch J, Victora CG, Yajnik CS, Yan H, Zeng L, and Black RE. 2013. “Risk of Childhood Undernutrition Related to Small-For-Gestational Age and Preterm Birth in Low- And Middle-Income Countries.” International journal of epidemiology 42 (5). doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Bachand AM, Heiderscheidt JM, Yoder SA, Luna B, Volckens J, Koehler KA, Conway S, Reynolds SJ, and Peel JL 2013. “Impact of a cleaner-burning cookstove intervention on blood pressure in Nicaraguan women.” Indoor Air 23 (2):105–14. doi: 10.1111/ina.12003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark ML, Peel JL, Balakrishnan K, Breysse PN, Chillrud SN, Naeher LP, Rodes CE, Vette AF, and Balbus JM 2013. “Health and household air pollution from solid fuel use: the need for improved exposure assessment.” Environ Health Perspect 121 (10):1120–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1206429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- G. B. D. Risk Factors Collaborators. 2020. “Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.” Lancet 396 (10258):1223–1249. doi: 10.1016/S01406736(20)30752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2016 Risk Factors Collaborators. 2017. “Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 - The Lancet.” The Lancet 390 (10100):1345–1422. doi: doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32366-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt Helen L., and Snow Robert W. 2001. “Malaria in pregnancy as an indirect cause of infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa.” Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 95 (6):569–576. doi: 10.1016/s00359203(01)90082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt Helen L., and Snow Robert W. 2004. “Impact of Malaria during Pregnancy on Low Birth Weight in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 17 (4):760–769. doi: 10.1128/cmr.17.4.760-769.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haider Mohammad Rifat, Rahman Mohammad Masudur, Islam Farahnaz, and Khan M. Mahmud. 2016. “Association of Low Birthweight and Indoor Air Pollution: Biomass Fuel Use in Bangladesh.” Journal of Health & Pollution 6:18–25. doi: 10.5696/2156-9614-6-11.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency, International Renewable Energy Agency, United Nations Statistics Division, World Bank, and World Health Organization. 2020. Tracking SDG 7 : The Energy Progress Report 2020. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Jack DW, Asante KP, Wylie BJ, Chillrud SN, Whyatt RM, Ae-Ngibise KA, Quinn AK, Yawson AK, Boamah EA, Agyei O, Mujtaba M, Kaali S, Kinney P, and Owusu-Agyei S. 2015. “Ghana randomized air pollution and health study (GRAPHS): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial.” Trials 16:420. doi: 10.1186/s13063-015-0930-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack DW, Ae-Ngibise KA, Gould CF, Boamah-Kaali E, Lee AG, Mujtaba MN, Chillrud C, Kaali S, Quinn AK, Gyaase S, Oppong FB, Carrión D, Agyei O, Burkhart K, Ana-aro JA, Liu X, Berko YA, Wylie BJ, Etego SA, Whyatt R, Owusu-Agyei S, Kinney P, Asante KP, 2021. A cluster randomised trial of cookstove interventions to improve infant health in Ghana. BMJ Glob. Health 6, e005599. 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-005599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz Joanne, Tielsch James M., Khatry Subarna K., Shrestha Laxman, Breysse Patrick, Zeger Scott L., Kozuki Naoko, Checkley William, LeClerq Steven C., and Mullany Luke C. 2020. “Impact of Improved Biomass and Liquid Petroleum Gas Stoves on Birth Outcomes in Rural Nepal: Results of 2 Randomized Trials.” Global Health: Science and Practice 8 (3):372–382. doi: 10.9745/ghsp-d-2000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan MN, Nurs CZ B, Mofizul Islam M, Islam MR, and Rahman MM 2017. “Household air pollution from cooking and risk of adverse health and birth outcomes in Bangladesh: a nationwide population-based study.” Environ Health 16 (1):57. doi: 10.1186/s12940-017-0272-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knol Mirjam J, van der Tweel Ingeborg, Grobbee Diederick E, Numans Mattijs E, and Geerlings Mirjam I. 2007. “Estimating interaction on an additive scale between continuous determinants in a logistic regression model.” International Journal of Epidemiology 36 (5):1111–1118. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee AG, Kaali S, Quinn A, Delimini R, Burkart K, Opoku-Mensah J, Wylie BJ, Yawson AK, Kinney PL, Ae-Ngibise KA, Chillrud S, Jack D, and Asante KP 2018. “Prenatal Household Air Pollution is Associated with Impaired Infant Lung Function with Sex-Specific Effects: Evidence from GRAPHS, a Cluster Randomized Cookstove Intervention Trial.” Am J Respir Crit Care Med 199 (6):738–746. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0694OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick MC. 1985. “The Contribution of Low Birth Weight to Infant Mortality and Childhood Morbidity.” The New England journal of medicine 312 (2). doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501103120204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczyk RT, Zhang J, Betran AP, Souza JP, Mori R, Gulmezoglu AM, and Merialdi M. 2011. “A global reference for fetal-weight and birthweight percentiles.” Lancet 377 (9780):1855–61. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)60364-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milanzi EB, and Namacha NM 2017. “Maternal biomass smoke exposure and birth weight in Malawi: Analysis of data from the 2010 Malawi Demographic and Health Survey.” Malawi Med J 29 (2):160–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell Owen, van Doorslaer Eddy, Wagstaff Adam, and Lindelow Magnus. 2008. Analyzing Health Equity Using Household Survey Data : A Guide to Techniques and Their Implementation. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Pope Daniel, Bruce Nigel, Dherani Mukesh, Jagoe Kirstie, and Rehfuess Eva. 2017. “Real-life effectiveness of ‘improved’ stoves and clean fuels in reducing PM2.5 and CO: Systematic review and meta-analysis.” Environment International 101:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn AK, Ae-Ngibise KA, Jack DW, Boamah EA, Enuameh Y, Mujtaba MN, Chillrud SN, Wylie BJ, Owusu-Agyei S, Kinney PL, and Asante KP 2016. “Association of Carbon Monoxide exposure with blood pressure among pregnant women in rural Ghana: Evidence from GRAPHS.” Int J Hyg Environ Health 219 (2):176–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2015.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suryadhi MAH, Abudureyimu K, Kashima S, and Yorifuji T. 2019. “Effects of Household Air Pollution From Solid Fuel Use and Environmental Tobacco Smoke on Child Health Outcomes in Indonesia.” J Occup Environ Med 61 (4):335–339. doi: 10.1097/jom.0000000000001554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson LM, Bruce N, Eskenazi B, Diaz A, Pope D, and Smith KR 2011. “Impact of reduced maternal exposures to wood smoke from an introduced chimney stove on newborn birth weight in rural Guatemala.” Environ Health Perspect 119 (10):1489–94. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1002928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Buuren Stef, and Groothuis-Oudshoorn Karin. 2011. “mice: Multivariate Imputation by Chained Equations in R.” 2011 45 (3):67. doi: 10.18637/jss.v045.i03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Villar J, Ismail L Cheikh, Victora CG, Ohuma EO, Bertino E, Altman DG, Lambert A, Papageorghiou AT, Carvalho M, Jaffer YA, Gravett MG, Purwar M, Frederick IO, Noble AJ, Pang R, Barros FC, Chumlea C, Bhutta ZA, and Kennedy SH. 2014. “International standards for newborn weight, length, and head circumference by gestational age and sex: the Newborn Cross-Sectional Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project.” Lancet (London, England) 384 (9946). doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60932-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood Simon N. 2017. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R (2nd edition). Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC. [Google Scholar]

- Wylie BJ, Kishashu Y, Matechi E, Zhou Z, Coull B, Abioye AI, Dionisio KL, Mugusi F, Premji Z, Fawzi W, Hauser R, and Ezzati M. 2017. “Maternal exposure to carbon monoxide and fine particulate matter during pregnancy in an urban Tanzanian cohort.” Indoor Air 27 (1):136–146. doi: 10.1111/ina.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yip F, Christensen B, Sircar K, Naeher L, Bruce N, Pennise D, Lozier M, Pilishvili T, Loo Farrar J, Stanistreet D, Nyagol R, Muoki J, de Beer L, Sage M, and Kapil V. 2017. “Assessment of traditional and improved stove use on household air pollution and personal exposures in rural western Kenya.” Environment international 99. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.