Abstract

Despite clinicians consistently advising against vaginal douching, 29–92% of women worldwide report douching. This review documents women’s douching practices, motivations for douching, and specific associations (or absence of associations) between vaginal douche use and vaginal outcomes thought to be associated with douching. Understanding women’s existing douching behaviors and vaginal health outcomes is critical for developing a safe vaginal microbicide douche that can be used as HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). A vaginal douche as PrEP could help prevent new HIV infections, since emerging evidence shows some women discontinue oral PrEP. We performed a systematic review of the literature using the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). Articles included in the analysis (N=48) were published 2009–2019 in English and focused on women’s experiences with douching. Two trained independent reviewers assessed these articles for content on vaginal douching, including racial/ethnic focus of studies, study design, sampling, women’s reasons for douching, contents of douche solutions, and associations between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes. Several studies focused on Black women (N=12 studies) or had no racial/ethnic focus (N=12). Just over half of all studies (N=24) were cross-sectional and involved a self-reported questionnaire and lab samples. Studies sampled women from health clinics where they were (N=13) or were not (N=14) presenting for vaginal health complaints. Women’s primary motivation for douching was for “general cleanliness” (N=13), and most douche solutions contained water (N=12). There was little empirical agreement between vaginal douche use and most vaginal health outcomes. Future studies of PrEP vaginal douches should be well controlled and prioritize safety to ensure positive vaginal health outcomes.

Introduction

Globally, slightly more than half of all adult people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) are women (1, 2). Though access to systemic HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), e.g., oral tenofovir disoproxil fumarate/emtricitabine (F/TDF; Truvada™) is growing (3–5), emerging evidence suggests that some women who start this medication later suspend their usage of it, across cultural and demographic groups. For example, in one study of cisgender women (e.g., women who were assigned female at birth and identify as women) who were prescribed PrEP, around 62.5% terminated use at six months (6). In a study in Kenya, only 38% of women who started PrEP continued to use it at one month (7). For women who do not want to use HIV prevention medication continuously, on-demand topical HIV prevention modalities that are behaviorally congruent with existing vaginal cleansing and/or sexual routines could be an attractive alternative. Vaginal douches that include a PrEP formulation could be one of these alternatives, since vaginal douching is prevalent worldwide (29%−92% of women reported douching in the past 90 days (8, 9)). In our subsequent review, we define “vaginal douching” as it is understood by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office on Women’s Health: “Douching is washing or cleaning out the vagina with water or other mixtures of fluids” (10). Women could use PrEP vaginal douches prior to sexual encounters in which they believe they cannot or will not use other HIV prevention strategies (e.g., condoms). However, it is critical that concerns for PrEP vaginal douche safety are central to the development of this product. Clinicians and other women’s health experts consistently advise against vaginal douching (11, 12), since some literature shows that this could increase one’s risk for vaginitis and HIV acquisition (13).

Understanding the nuance of women’s varied vaginal douching practices and potential health outcomes would allow product developers to create a PrEP vaginal douche that is safe and most consistent with women’s current douching behavior. At present, however, we know little about specific vaginal douching behaviors or trends on how douching practices might influence vaginal health outcomes. That is, we are not aware of any recent studies that have provided a review of the literature to document women’s douching practices, motivations for douching, and specific associations (or absence of associations) between vaginal douche use and vaginal outcomes thought to be associated with douching behavior (e.g., bacterial vaginosis [BV], pelvic inflammatory disease [PID], candida). Understanding the broad context of these vaginal douching variables critically informs the development of a microbicide formulated as a vaginal douche for HIV prevention.

Despite clinical recommendations against vaginal douching (10–17), the existing literature shows that women continue to do so for a variety of reasons. Most commonly, women use vaginal douches because they believe they contribute to overall cleanliness, will prevent or treat vaginal odor or infections, and/or facilitate greater cleanliness associated with sex (8, 18, 19). Globally, researchers have reported wide-ranging prevalance (from 29%−92%) for vaginal douching in the past 90 days (8, 9). This wide range can be explained by a number of factors, including professional occupation (e.g., female sex workers may use vaginal douches more frequently than other women) (20, 21), sociocultural norms (e.g., in some social and cultural contexts, vaginal douching is believed to be a routine part of feminine hygiene) (18, 22), and sociodemographic factors (e.g., women living in comparatively low-income settings are more likely to use vaginal douches than higher-income women) (23).

Preliminary studies show that rectal douches (also called enemas) could have an HIV-preventive effect for anorectal exposures (24–27) and are acceptable by potential end-users (28, 29); these medications could potentially be reformulated for vaginal use. Specifically, administration of tenofovir via a rectal douche results in faster and higher drug concentration in the rectal mucosa than oral administration in clinical studies without toxicity (30). Further, the same tenofovir douche provides greater protection than oral F/TDF in macaque rectal SHIV challenge studies (31). Though vaginal tissue and flora are different from those of the rectum, it is possible that this strategy could be modified for vaginal application. This could be especially useful for women who already douche, as this HIV prevention strategy is congruent with their existing sexual or cleansing routines.

We sought a better understanding of the relationships between vaginal douche use and vaginal health; in turn, this could broaden researchers’ HIV prevention toolkit to consider a novel, potentially viable, female-centric, behaviorally congruent, non-systemic biomedical HIV prevention strategy that may have otherwise been dismissed. With this in mind, we set out to systematically review the scientific literature to identify (1) women’s motivations to use vaginal douches, (2) which vaginal douching products women use, (3) relationships between vaginal douche use and vaginal health outcomes, and (4) characteristics of studies that examine douching and vaginal health outcomes (e.g., study design, sample recruitment). This article reviews the literature published between 2009 and 2019 on cisgender women’s vaginal douching practices globally.

Methods

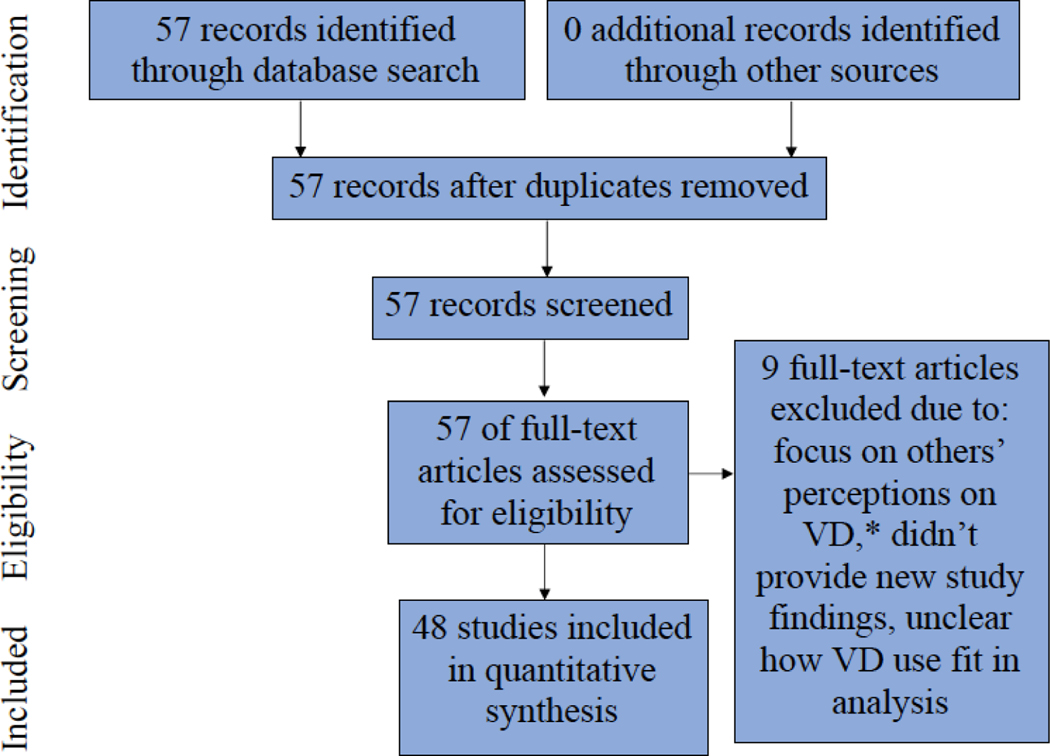

We performed a systematic review of the literature using the guidelines for Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) (32). Figure 1 shows the flow of information through our scientific review, consistent with PRISMA principles. The primary author (CR) and a research assistant (DD) searched scientific databases including Google Scholar, PubMed, and the primary author’s university library (Columbia University) for the following terms: vaginal douching, intravaginal washing, and intravaginal cleansing. Additionally, we searched the “gray literature” (e.g., Google) for these terms. Any duplicates identified in the various databases/search mechanisms were deleted. Studies included in the current review were, (1) focused on women, women’s experiences, and vaginal outcomes associated with douching, and (2) published in peer-reviewed, English-language journals between 2009 and 2019. Studies on men’s perceptions of vaginal douching or articles focused on holistic healthcare practitioners’ (or vendors who sell holistic healthcare products) relationships to douching were excluded.

Figure 1:

Flow of Information through Different Phases of a Scientific Review

* For the purpose of this table, VD=vaginal douching

CR conducted the initial search to identify articles that fit the above criteria to include in the review. Then, DD independently completed a second review of the selected articles to corroborate these inclusions. CR and DD met to discuss disagreements and determine a finalized selection of texts. Then, DD acted as lead reviewer of article content. Data abstraction tables were developed to retrieve study characteristics and the major findings of the reviewed studies. The study characteristics included: (1) Study-related factors, including the demographic focus of the study sample (e.g., specific racial or ethnic populations studied), the study design (e.g., cross-sectional self-report, observational study, randomized controlled trial), and the sub-samples of women who were considered for each study (e.g., recruited women presenting for vaginal symptoms or a sexually transmitted disease (STI) at a clinic, women seeking pregnancy care, or sex workers); (2) women’s reasons for douching and contents of douche solutions; and (3) conditions (e.g., BV, PID, HPV, candida, and several others) found to be negatively associated or not negatively associated (e.g., the hypothesized negative relationship was not detected in statistical models) with douching. The presence or lack of a negative relationship was abstracted from the Results section text and/or tables in the manuscripts included in this review. Using a quantitative synthesis process that focused on carefully assessing descriptive data and regression results to identify the study-related factors described above, DD coded articles to fit the abstraction tables with count data to show the number of articles that met the above study characteristics. Then, CR independently coded these articles using the same abstraction tables and quantitative synthesis process; DD and CR met to discuss disagreements until consensus and finalize the tables.

Results

In total, 57 articles were identified through the scholarly databases mentioned above and assessed for eligibility; we did not identify any unique peer-reviewed articles in the “gray literature.” Nine manuscripts were excluded from the final analysis, resulting in N=48 articles in the final review (8, 18–23, 33–72). Reasons for excluding articles included: they focused on other peoples’ perceptions of douching (e.g., men, holistic health practitioners or vendors) (73, 74), they summarized the findings of prior vaginal douche-related research and didn’t provide new study findings (13, 75–79), or it was unclear how douching fit into the authors’ models for analysis (e.g., the statistical models did not explicitly define how douching was considered) (80).

Tables 1–4 show the specific studies associated with each finding or category. To avoid duplication, we do not present these results in the article text. Table 1 provides the racial and demographic foci, study design information, and participant samples recruited in the 48 articles. Several studies focused on Black women (N=12), Asian women (N=12), or had no ethnic focus (N=11). Just over half of all included studies (N=24) were cross-sectional in design and involved a self-reported questionnaire and lab samples. Almost another one-third (N=16) were cross-sectional and only utilized self-reported questionnaires. Over one-quarter of the articles sampled (N=14) recruited participants from health facilities where they were not presenting for vaginal health concerns or the reason for their visit was not reported; another quarter (N=13) sampled populations of women who were presenting for vaginal complaints, and N=8 studies sampled sex workers.

Table 1:

Racial Demographic Focus, Study Design, and the Sample from which Human Subjects Participants were Recruited

| Racial Demographic Focus | Study Design | Sample from which Human Subjects Participants were Recruited* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Racial Category | # Articles | Study Design | # Articles | Human Subjects Sample | # Articles |

| Black women • US-based population (8, 55) • Africa-based population (18, 20, 34, 38, 43, 45, 56, 59, 72) • Caribbean Islands-based population (19) |

12 | Cross-Sectional: self-reported questionnaire and lab samples taken (20, 21, 23, 34, 36, 37, 39, 40, 43, 45, 48, 51, 53, 54, 59, 60, 62, 64, 66, 67, 69, 70, 72, 95) | 24 | Health facility (not presenting for vaginal or STI complaints, or reason for visit unreported) (8, 23, 33, 43, 44, 49, 51, 52, 57, 58, 60, 62, 66, 68) | 14 |

| No Racial/Ethnic Focus (22, 35, 37, 41, 47, 50, 52, 54, 60, 65, 70, 95) | 12 | Cross-Sectional: self-reported questionnaire only (no laboratory samples taken) (8, 18, 19, 22, 33, 37, 38, 41, 42, 44, 47, 49, 57, 58, 63, 68) | 16 | ||

| Asian women; all studies were conducted with women based in Asia (18, 21, 36, 39, 40, 51, 53, 62, 67, 69, 71) | 11 | Observational or longitudinal study (40, 52, 56, 65) | 4 | Health facility (presenting for vaginal complaints (e.g., odor, itching, burning, abnormal discharge), or STI) (19, 23, 34, 39, 45, 48, 50, 59, 64, 69–71, 95) | 13 |

| Latinx/Hispanic women (42, 57, 58, 61, 63, 66) • US-based population (42, 57, 58, 63) • Latin America-based population (61, 66) |

6 | Sex workers (20, 21, 36, 53, 56, 61, 67, 72) | 8 | ||

| Turkish women; all studies were conducted with women based in Turkey (23, 33, 44, 48, 49, 68) | 6 | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) (50, 55, 61) | 3 | Pregnant women (54) | 1 |

| Other (e.g., non human subjects research) (46, 64) | 2 | Other (35, 46) | 2 | Other (18, 22, 35, 37, 38, 40–42, 47, 63, 65) | 11 |

Category does not add up to 49, since two studies in this review did not conduct human subjects research

Note that Racial Demographic Focus, Study Design, and Sample from which Human Subjects Participants were Recruited are distinct categories from one another; side-by-side presentation of these results does NOT indicate stratification.

Table 4:

Summary of literature review

| Authors (year) | Racial - demographic focus | Population | Study Design; Outcome type for key associations | Reasons for douching | Contents of douche solution | Key associations between VAGINAL DOUCHING and vaginal health outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcaide et. al. (2017) | No racial/ethnic focus | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | Water; water + soap commercially prepared; water + vinegar | Positive association between vaginal douching and changed vaginal flora |

| Arbour et. al. (2009) | No racial/ethnic focus | Other | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | None given | None given | Article does not assess relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes |

| Arfiputri et. al. (2018) | Asian women | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Other | None given | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and candida |

| Arslantas et. al. (2010) | Turkish women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | Prevent or treat odor; prevent pregnancy; other (religious duty, traditional habit, vaginal drying/tightening) | Water; water + soap; water + vinegar; other or multiple agents | Positive association between vaginal douching and pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) |

| Aubyn et. al. (2013) | Black women | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Article does not assess clear relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes |

| Brotman et. al. (2010) | No racial/ethnic focus | Other | Other; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with bacterial vaginosis (BV) |

| Bui et. al. (2016) | No racial/ethnic focus | Other | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was found to be positively associated with human papilloma virus (HPV) |

| Bui et. al. (2018) | Asian women | Sex workers | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with HPV |

| Carter et. al. (2013) | Black women | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | General cleanliness; sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex); prevent or treat infection; other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening | Water; water + soap | Study found that there was both the presence of a positive association between vaginal douching and vaginal discomfort, and the absence of a positive association between vaginal douching and this vaginal health outcome |

| Chu et. al. (2011) | Asian women | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | Water; other or multiple agents | Positive association between vaginal douching and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) |

| Chu et. al. (2013) | Asian women | Other | Observational or longitudinal study; Biological outcome data | None given | Water; commercially prepared | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with HPV |

| Crann et. al. (2018) | No racial/ethnic focus | Other | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | None given | Commercially prepared | Positive association between vaginal douching and BV, candida, and urinary tract infection (UTI). Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with current or past STI status (including HIV) |

| De La Cruz et. al. (2009) | Latinx/Hispanic women | Other | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | General cleanliness; prevent or treat odor | Commercially prepared | Positive association between vaginal douching and BV, and current or past STI status (including HIV) (specifically, VAGINAL DOUCHING was positively associated with gonorrhea). Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with PID, UTI, or current or past STI status (including HIV) (specifically, VAGINAL DOUCHING was not positively associated with chlamydia) |

| DiClemente et. al. (2012) | Black women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal or STI complaints, (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | General cleanliness; prevent or treat odor; prevent or treat infection; Other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening | Water; commercially prepared; water + vinegar | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with current or past STI status (including HIV) |

| Donders et. al. (2016) | Black women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with changed vaginal pH |

| Ekpenyong et. al. (2014) | Black women | Other | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | General cleanliness; Sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex); prevent or treat infection; cleaning after menses; prevent pregnancy; Other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening | Water + soap | Article does not assess relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes |

| Erbil et. al. (2012) | Turkish women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with preterm birth and vaginal discomfort |

| Esber et. al. (2016) | Black women | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | Water + soap; Other or multiple agents | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with BV, HPV, or herpes simplex 2 |

| Esim et. al. (2010) | No Racial/Ethnic focus | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with BV, candida, current or past STI status (including HIV), or vaginal discomfort |

| Fashemi et. al. (2013) | Other (e.g., non human subjects research) | Non-human subjects research | Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with changed vaginal flora |

| Gonzalez et. al. (2016) | No Racial/Ethnic focus | Other | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | None given | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and ovarian cancer |

| Güzel et. al. (2011) | Turkish women | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | General cleanliness; Other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening | Water + soap | Positive association between vaginal douching and vaginal discomfort |

| Hacialioglu et. al. (2009) | Turkish women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | General cleanliness; Sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex); prevent pregnancy; Other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening | Water; water + soap; other or multiple agents | Positive association between vaginal douching and vaginal discomfort |

| Hassan et. al. (2011) | No Racial/Ethnic focus | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT); Biological outcome data | None given | Commercially prepared | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with odor |

| Heng et. al. (2010) | Asian women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and vaginal discomfort |

| Klebanoff et. al. (2010) | No Racial/Ethnic focus | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal or STI complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Observational or longitudinal study; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and BV |

| Li et. al. (2015) | Asian women | Sex workers | Cross-Sectional: Biological outcome data | Prevent or treat infection | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and current or past STI status (including HIV), and vaginal discomfort |

| Low et. al. (2010) | Black women | Sex workers | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with HPV |

| Luo et. al. (2016) | Asian women | Sex workers | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | General cleanliness; prevent or treat odor; prevent or treat infection; cleaning after menses; prevent pregnancy; Other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening | Water; water + vinegar; other or multiple agents | Positive association between vaginal douching and herpes simplex 2, and current or past STI status (including HIV) (specifically, vaginal douching was positively associated with HIV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia). Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with trich, and current or past STI status (including HIV) (specifically, vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with syphilis) |

| Luong et. al. (2010) | No Racial/Ethnic focus | Pregnant women | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with preterm birth |

| Mairiga et. al. (2010) | Black women | Sex workers | Cross-Sectional: Self-reported data | Prevent or treat odor; sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex); prevent or treat infection; prevent pregnancy | Water + lemon or lime juice | Positive association between vaginal douching and BV, candida, trich and current or past STI status (including HIV) |

| Mark et. al. (2010) | Black women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | General cleanliness; sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex); cleaning after menses | None given | Article does not assess relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes |

| Martin-Hilber et. al. (2010) | Black women | Other | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | Prevent or treat odor; sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex) | None given | Article does not assess relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes |

| Masese et. al. (2013) | Black women | Sex workers | Observational or longitudinal study; Self-reported data | Prevent or treat odor; prevent or treat infection; cleaning after menses; other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening | Water; water + soap; other or multiple agents | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with BV or changed vaginal flora |

| McKee et. al. (2009) | Latinx/Hispanic women | Health facility _ not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | General cleanliness; prevent or treat odor; sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex); prevent or treat infection; cleaning after menses | Commercially prepared; water + vinegar; other or multiple agents | Article does not assess relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes |

| McKee et. al. (2009) | Latinx/Hispanic women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | General cleanliness; sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex) | Commercially prepared; water + vinegar; other or multiple agents | Article does not assess relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes |

| Nwadioha et. al. (2011) | Black women | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | Water; water + soap; other or multiple agents | Positive relationship between vaginal douching and BV. |

| Ott et. al. (2009) | No Racial/Ethnic focus | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with current or past STI status |

| Pines et. al. (2018) | Latinx/Hispanic women | Sex workers | Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT); Biological outcome data | General cleanliness; prevent or treat odor; sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex); prevent or treat infection | Water + soap; commercially prepared; water + vinegar; water + lemon or lime juice; water + perfumes or herbs | Article does not assess relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes |

| Ranjit et. al. (2018) | Asian women | Health facility- not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and BV |

| Redding et. al. (2010) | Latinx/Hispanic women | Other | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | None given | None given | Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with current or past STI status |

| Shaaban et. al. (2015) | Other (e.g., non human subjects research) | Samples taken from tissue of women who had accessed a health facility (presenting for vaginal complaints (e.g., odor, itching, burning, abnormal discharge), or STI) | Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and PID Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with candida, preterm birth, or ectopic pregnancy |

| Sunay et. al. (2011) | Turkish women | Samples taken from both populations reporting to a health facility | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | General cleanliness; prevent or treat odor | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and vaginal discomfort |

| Tsai et. al. (2009) | No Racial/Ethnic focus | Other | Observational or longitudinal study; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and current or past STI status (including HIV) |

| von Glehn et. al. (2017) | Latinx/Hispanic women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | Water; other multiple agents | Positive relationship between vaginal douching and changed vaginal pH |

| Wang et. al. (2009) | Asian women | Sex workers | Cross-Sectional: Biological outcome data | None given | Water; water + soap; other or multiple agents | Vaginal douching was positively associated with HIV in high risk sex work venues, but was not positively associated with HIV in low-risk sex work venues |

| Yanikkerem et. al. (2016) | Turkish women | Health facility - not presenting for vaginal complaints (or reason for visit unreported) | Cross-Sectional; Self-reported data | General cleanliness; prevent or treat odor; sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex); prevent or treat infection; cleaning after menses; prevent pregnancy; other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and candida, vaginal discomfort, and odor Vaginal douching was not found to be positively associated with preterm birth or ectopic pregnancy |

| Zeng et. al. (2018) | Asian women | Health facility - presenting for vaginal complaints | Cross-Sectional; Biological outcome data | None given | None given | Positive association between vaginal douching and candida |

Women’s reasons for vaginal douching and the reported contents of their douche solutions are presented in Table 2. Slightly more than a quarter of the articles (N=13) reported that women used vaginal douches for general cleanliness. Nearly a quarter (N=11) douched to prevent or treat vaginal odor, for sex-related hygiene (N=10), or to prevent or treat infection (N=10). Almost a quarter of the manuscripts (N=12) reported that douche solutions contained plain water, water and soap (N=11), or other or multiple agents (e.g., disinfectants; N=11).

Table 2:

Women’s Reasons for Douching and Contents of Douche Solution*

| Reasons for Douching | # Articles |

|---|---|

| General cleanliness (8, 19, 21, 23, 38, 42, 48, 49, 55, 57, 58, 61, 68) | 13 |

| Prevent or treat odor (8, 18, 20, 21, 23, 33, 42, 56, 58, 61, 68) | 11 |

| Sex-related hygiene (e.g., cleaning before or after sex) (18–20, 38, 49, 55, 57, 58, 61, 68) | 10 |

| Prevent or treat infection (8, 19–21, 38, 53, 56, 58, 61, 68) | 10 |

| Cleaning after menses (21, 38, 55, 56, 58, 68) | 6 |

| Prevent pregnancy (20, 21, 33, 38, 49, 68) | 6 |

| Other (religious duty, traditional habit), vaginal drying/tightening (8, 19, 21, 33, 38, 48, 49, 56, 68) | 9 |

| Contents of Douche Solution | # Articles |

| Water (8, 19, 21, 33, 39, 40, 49, 56, 59, 66, 67, 70) | 12 |

| Water + soap (19, 33, 38, 45, 48, 49, 56, 59, 61, 67, 70) | 11 |

| Commercially prepared (8, 40–42, 50, 57, 58, 61, 70) | 9 |

| Water + vinegar (8, 21, 33, 57, 58, 61, 70) | 7 |

| Water + lemon or lime juice (20, 61) | 2 |

| Water + perfumes or herbs (61) | 1 |

| Other or multiple agents (21, 33, 39, 45, 49, 56–59, 66, 67) | 11 |

Categories do not add up to 49, since categories in this table were not mutually exclusive

Table 3 summarizes the vaginal health conditions that the studies found to be negatively associated with douching, as well as the vaginal health outcomes that were found to have positive or no associations with vaginal douching. Most vaginal health conditions had mixed results or results that were not replicated. For example, six studies found that using vaginal douches was negatively associated with BV, while four studies found that it was not. Additionally, six studies found that vaginal douching was negatively associated with current or past STI status (including HIV), while eight studies found that it was not. Results were also mixed for human papilloma virus (HPV; one study found a negative association, three found no negative association) and candida (negative association in six studies, no negative association in two studies). Trichomoniasis, ovarian cancer, and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) were found to be negatively associated with vaginal douching in a single report for each outcome. However, these results were not replicated in other studies in this review. On the other hand, there was no negative association detected between vaginal douching and preterm birth (N=4) or ectopic pregnancy (N=2); these results were not contradicted. Other relationships between vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes [e.g., pelvic inflammatory disorder (PID), changed vaginal flora, changed vaginal pH, herpes simplex 2, vaginal odor, and urinary tract infection (UTI)] were represented in both the associated and not associated categories, one to two times each. No articles included in this review examined vaginal douching’s relationship with vaginitis, cervical cancer, or reduced fertility.

Table 3:

Vaginal douching and Association with Specific Vaginal Health Outcomes

| Vaginal Health Outcomes Found to be Positively* Associated with Douching | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BV (20, 41, 42, 52, 59, 62) | PID (33, 64) | HPV (37) | Candida (20, 41, 68, 69, 71, 96) | Trich (20) | Ovarian Cancer (47) | Preterm Birth | Changed Vag Flora (70) | Changed Vag pH (66) | Current or Past STI status (including HIV) (20, 21, 42, 53, 65, 67) | Ectopic preg | Vaginal discomf (19, 23, 48, 49, 51, 53, 68) | Herpes 2 (21) | Odor (68) | LSIL (39) | UTI (41) |

| 6 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Vaginal Health Outcomes NOT Found to be Positively Associated with Douching | |||||||||||||||

| BV (35, 45, 56, 95) | PID (42) | HPV (36, 40, 45, 72) | Candida (64, 95) | Trich (21) | Ovarian Cancer | Preterm Birth (44, 54, 64, 68) | Changed Vag Flora (46, 56) | Changed Vag pH (43) | Current or Past STI status (including HIV) (8, 21, 41, 42, 60, 63, 67, 95) | Ectopic preg (64, 68) | Vaginal discomf (19, 44, 95) | Herpes 2 (45) | Odor (50) | LSIL | UTI (42) |

| 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

Positively means vaginal douching was found to be at least partially responsible for the given vaginal health outcome

Table 4 presents an overall summary of each article and its findings, relative to the goals of this review.

Discussion

Women engage in douching behaviors across sociocultural and geographic settings. From the current literature review, there is little empirical agreement between vaginal douche use and most vaginal health outcomes. Specifically, this means that some associations are found in only one study, or are mixed (e.g., some studies find an association between vaginal douche use and a negative health outcome, while others do not). This is likely due to three things that have a high likelihood of introducing bias, including, 1) a lack of consistent attention to potential confounders, including the contents of douching solutions and douching frequency, 2) less than ideal sampling conditions (e.g., recruiting participants from populations that already report negative vaginal health outcomes or are at increased risk for negative vaginal health outcomes), and 3) reliance on a cross-sectional design or self-reported data.

Thus, the literature around vaginal douching behavior and vaginal health outcomes is conflicting. This is problematic, since potential new microbicide rectal douches that are currently in clinical trials could feasibly be reformulated for vaginal use. Specifically, these products could provide cisgender women who are unable or unwilling to use systemic HIV prevention medications with a short-term, female-controlled, safe, and behaviorally congruent biomedical HIV prevention strategy. However, current messaging around douching could negatively affect both scientific and community interest in developing such products, as well as end-users’ willingness to use them.

It is possible that using a vaginal douche that is clinically developed to rigorously demonstrate safety and efficacy, rather than one purchased over-the-counter or using homemade ingredients, could have fewer or no negative vaginal health outcomes and could curtail viremia. In a study published in 2006, researchers found that douching with a clinically developed stainless steel device and tap water did not change the vaginal ecology (as observed by Lactobacilli scores from Nugent slides and vaginal pH determination) (81). Additionally, among women who complained of perceived vaginal odor, douching with the stainless steel device/tap water was successful in ameliorating the issue (50, 81). Another randomized controlled trial that used the same device to evaluate its effectiveness for treating perceived vaginal odor with no infectious cause of vaginitis, found that this vaginal douche was able to effectively treat perceived odor without changing Nugent and Lactobacillus scores (50). Other studies have found that douching after intercourse could reduce the infectious load of sexually transmitted pathogens, such as HPV (40, 82), which has implications for an HIV prevention microbicide douche. Studies examining other delivery modalities of topical microbicides (e.g., ring, gels) have shown that these products are safe for vaginal use with respect to potential adverse events (83–85). Though these studies may open the door to the possibility of vaginal microbicide douches, future research on these products should ensure that the devices and douching liquids used are carefully controlled and tested.

Carefully controlling vaginal douche devices and liquids used for PrEP would address some of these issues identified in our research. Additionally, future studies should attempt to control an important potential key confounder: douching frequency. In current studies, rectal tissue TVF-DP concentrations exceed four oral dose/week concentrations for three days. Though we can only speculate, as vaginal douches for PrEP (excluding gels (86), which are a distinct product) are not yet in development, it is feasible that vaginal douche products could have a similar duration. Nonhuman primate studies have demonstrated that vaginal tenofovir douches achieve concentrations associated with vaginal protection from SHIV challenge (25) Given that vaginal and rectal tissue are distinct from one another, it is critical that researchers consider this when reformulating rectal douches for vaginal use. This is particularly true, given that we are only beginning to understand how the vaginal microbiome may interact with PrEP medications. Furthermore, existing literature on internally applied products for PrEP (e.g., gels, rings) may offer some insight into considerations for PrEP vaginal douches. These include ensuring that the application process is easy, that medications and the douching device do not cause discomfort during or after application, that dosing regimens are realistic and simple to follow, and that the product does not negatively impact sex (e.g., does not cause painful or uncomfortable intercourse) (87). Products that are perceived as incompatible with menses or that enable partners to detect that the product has been used would pose additional barriers to consistent use (88).

Regardless, researchers should ensure that participants in trials are clear on how often they should use vaginal douche PrEP products, and ensure that the timing of douching delivery protocols are as consistent as possible with women’s existing douching preferences. Specifically, to create a douching product that is behaviorally congruent with women’s existing preferences, it will be necessary to develop a product to deliver protective concentrations of PrEP drugs when dosed in a variety of ways. Furthermore, given women’s frequency of douching and motivations to douche, it will be critical to find a non-toxic and safe drug designed for continuous vaginal douche use.

Vaginal douche users often use these products for their perceived cleansing properties (e.g., for general cleanliness, prevention or treatment of odor, cleaning after sex). This theme is further reflected in the contents of douche solutions, which often include water mixed with other cleaning agents (e.g., soap, vinegar). Existing research on hair loss and acne shows that potential end-users could be especially willing to use medications when they have a positive effect on appearance (89, 90). Given this, potential messaging around PrEP vaginal douches could highlight this product’s vaginal cleansing effects and its perceived positive impact on vaginal presentation, in addition to its HIV prevention properties, to generate greater appeal.

Future studies of vaginal douches for PrEP should follow protocols similar to rigorously designed and conducted vaginal microbicide development studies. Specifically, these studies should use a prospective, randomized controlled trials design. It appears that much of the literature around vaginal douche use relies excessively on self-report and cross-sectional designs, which introduces bias. Furthermore, participants in PrEP vaginal douching studies should be drawn from samples similar to those used in other PrEP trials. In particular, these participants should include healthy, non-pregnant women who have been treated for vaginal concerns or other STIs prior to enrollment; this would help to minimize the effect of sampling bias, since women in other studies on vaginal douches are frequently recruited from groups that already have or are more likely to have existing vaginal complaints.

Vaginal microbicide douches have the potential to offer a behaviorally congruent HIV prevention option to women across multiple socialcultural and geographic contexts. Previous studies have found that intravaginal product use, including douches, is common in settings on the African continent (91). In sub-Saharan Africa, where more than 70% of the world’s HIV infections are concentrated (92) and 56% of new adult HIV infections are diagnosed in women (93), this potential future product may be especially impactful. Future studies on this topic should consider the perspectives and preferences of women living in high HIV prevalence settings in sub-SaharanAfrica.

Lastly, future researchers could consider sex workers as a “special population” related to douching. Though we can only speculate because it is beyond the scope of the review, it is possible that sex workers may have different douching needs, preferences, and practices. This could necessitate the development of a douche formulation that is specifically designed to be used within the context of sex work or high-risk intercourse. For example, it may be necessary to formulate a douching product for sex workers that provides a higher TFV-DP concentration, saturates vaginal tissue with protective medication more quickly, and can be used on a more frequent basis.

Conclusions

Despite perceptions in the medical community that douching results in negative vaginal health outcomes, the relationship between vaginal douche use and vaginal health may be more complex. The existing research has mostly failed to consider important potential confounders of this relationship, including douching frequency and the contents of douching liquids. Additional bias has been introduced to existing research through poor sampling practices (e.g., sampling participants from populations who already have or are more likely to have vaginal complaints), as well as a reliance on a cross-sectional designs and/or on self-reported data. Taken together, these issues have prevented researchers from achieving consensus with regard to vaginal douching and vaginal health outcomes. Thus, much of what we think we know about vaginal douche use is based on science conducted under less than ideal conditions.

On the other hand, well controlled studies of vaginal douching and vaginal health have shown that douching, in some contexts, has favorable outcomes (81). Given this, it is worthwhile to consider the possibility of a vaginal microbicide douche for HIV prevention, since this product could be used on-demand when women are experiencing risk (e.g., rather than taking medication continuously), is topical (e.g., as this is not systemic, it could reduce drug exposure and systemic symptoms), and is behaviorally congruent with existing vaginal/sexual practices (e.g., it would not require a behavior change – only a minor variation in the specific product used). Other topical vaginal products (e.g., rings) are effective at preventing HIV when used as directed and have acceptable safety profiles (84, 85, 94). Thus, it is possible that other vaginally delivered topical microbicides, such as a douche, could be similarly effective. In light of current work with rectal microbicide enemas, a pharmaceutical grade vaginal PrEP douche with a rigorously demonstrated safety and efficacy profile, could be vastly different than douching with unregulated products. As such, future studies should consider developing this topical, on-demand, female-controlled, non-systemic, behaviorally congruent HIV prevention strategy

Acknowledgments

Declarations

Funding

The first author is supported by a K01 Award (K01 MH115785; Principle Investigator: Christine Rael, Ph.D.) from the National Institute of Mental Health at the HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies at the NY State Psychiatric Institute and Columbia University (P30 MH43520; Center Principle Investigator: Robert Remien, Ph.D.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health or the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests

Dr. Craig Hendrix has received financial support for clinical research from Gilead, Merck, and ViiV/GSK. He has also served in the past on scientific advisory boards for Gilead, Merck, ViiV/GSK, and Population Council. Dr. Rachel Scott has received funds to complete investigator-sponsored research from Gilead. The remaining authors have no conflicts to declare.

Footnotes

Ethics approval

Not applicable

Consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Available of data and material

Not applicable

Code availability

Not applicable

References

- 1.UNAIDS. Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Geneva; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Ending AIDS: Progress towards the 90–90-90 targets. Geneva; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3.US Department of Health and Human Services: Ready, Set, PrEP expands access to medication to prevent HIV [press release]. Washington, D.C.2019. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Expanding access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for adolescents and young adults: Models for addressing consent, confidentiality, and payment barriers [press release]. Washington, D.C.2019.

- 5.Cairns G. PrEP spreads across Africa - slowly. England, UK: https://www.aidsmap.com/news/aug-2018/prep-spreads-across-africa-slowly; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blackstock OJ, Patel VV, Felsen U, Park C, Jain S. Pre-exposure prophylaxis prescribing and retention in care among heterosexual women at a community-based comprehensive sexual health clinic. AIDS Care. 2017;29(7):866–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinuthia J, Pintye J, Abuna F, Mugwanya KK, Lagat H, Onyango D, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis uptake and early continuation among pregnant and post-partum women within maternal and child health clinics in Kenya: results from an implementation programme. The Lancet HIV. 2020;7(1):e38–e48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diclemente RJ, Young AM, Painter JL, Wingood GM, Rose E, Sales JM. Prevalence and correlates of recent vaginal douching among African American adolescent females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25(1):48–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hull T, Hilber AM, Chersich MF, Bagnol B, Prohmmo A, Smit JA, et al. Prevalence, motivations, and adverse effects of vaginal practices in Africa and Asia: findings from a multicountry household survey. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(7):1097–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DHHS. Douching Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2020. [Available from: https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/douching ]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.ACOG. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) 2020. [Available from: https://www.acog.org ].

- 12.AAFP. American Academy of Family Physicians 2020. [Available from: https://www.aafp.org/home.html ].

- 13.Cottrell BH. An Updated Review of of Evidence to Discourage Douching. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2010;3(2):102–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Thomas G, Leybovich E. Vaginal douching and adverse health effects: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 1997;87(7):1207–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martino JL, Vermund SH. Vaginal douching: evidence for risks or benefits to women’s health. Epidemiol Rev. 2002;24(2):109–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wølner-Hanssen P, Eschenbach DA, Paavonen J, Stevens CE, Kiviat NB, Critchlow C, et al. Association between vaginal douching and acute pelvic inflammatory disease. JAMA. 1990;263(14):1936–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.OWH. Office on Women’s Health: Douching 2020. [Available from: https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/douching ].

- 18.Martin Hilber A, Hull TH, Preston-Whyte E, Bagnol B, Smit J, Wacharasin C, et al. A cross cultural study of vaginal practices and sexuality: implications for sexual health. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(3):392–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carter M, Gallo M, Anderson C, Snead MC, Wiener J, Bailey A, et al. Intravaginal Cleansing among women attending a STI Clinic in Kingston, Jamaica. West Indian Med J. 2013;62(1):56–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mairiga AG, Kullima AA, Kawuwa MB. Social and health reasons for lime juice vaginal douching among female sex workers in Borno State, nigeria. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Family Medicine. 2010;2(1):125–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Luo L, Xu JJ, Wang GX, Ding GW, Wang N, Wang HB. Vaginal douching and association with sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers in a prefecture of Yunnan Province, China. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27(7):560–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arbour M, Corwin EJ, Salsberry P. Douching patterns in women related to socioeconomic and racial:ethnic characteristics. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 2009;38:577–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sunay D, Kaya E, Ergun Y. Vaginal douching behavior of women and relationship among vaginal douching and vaginal discharge and demographic factors. Journal of Turkish Society of Obstetric and Gynecology. 2011;8(4):264–71. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leyva FJ, Bakshi RP, Fuchs EJ, Li L, Caffo BS, Goldsmith AJ, et al. Isoosmolar enemas demonstrate preferential gastrointestinal distribution, safety, and acceptability compared with hyperosmolar and hypoosmolar enemas as a potential delivery vehicle for rectal microbicides. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2013;29(11):1487–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao P, Gumber S, Marzinke M, Date AA, Hoang T, Hanes J, et al. Hypo-osmolar formulation of tenofovir (TFV) enema promotes uptake and metabolism of TFV in tissues, leading ot prevention of SHIV/SIV infection. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 2018;62(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoang T, Date AA, Ortiz JO, Young TW, Bensouda S, Xiao P, et al. Development of rectal enema as microbicide (DREAM): Preclinical progressive selection of a tenofovir prodrug enema. Eur J Pharm Biopharm. 2019;138:23–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fernandez Romero JA, Paglini MG, Zydowsky TM. Topical focmulations to prevent sexually transmitted infections: Are we on track? Future Virology. 2019;14(8):503–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carballo-Dieguez A, Bauermeister JA, Ventuneac A, Dolezal C, Balan I, Remien RH. The use of rectal douches among HIV-uninfected and infected men who have unprotected receptive anal intercourse: implications for rectal microbicides. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(6):860–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tingler RC, Connochie D, Bauermeister JA. Rectal Douching and Microbicide Acceptability among Young Men who Have Sex with Men. AIDS Behav. 2020;24(5):1414–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weld E, Fuchs EJ, Marzinke M, Anton P, Bakshi R, Engstrom J, et al. Tenofovir douche for PrEP: on-demand, behaviorally-congruent douche rapidly achieves colon tissue concentration targets (DREAM 01 Study). HIV Research for Prevention (HIVR4P); October 2018; Madrid, Spain2018. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao P, Gumber S, Marzinke MA, Date A, Hoang T, Hanes J, et al. Hypo-osmolar rectal douche delivered TFV distributes TFV differently than oral PrEP. CROI; Boston, USA: 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(4):264–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arslantas D, Karabagli H, Koc F. Vaginal douching practice in Eskisehir in Turkey. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology. 2010;2(9):245–50. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aubyn GB, Tagoe DNA. Prevalence of vaginal infections and associated lifestyles of students in the university of Cape Coast, Ghana. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease. 2013;3(4):267–70. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brotman RM, Ravel J, Cone RA, Zenilman JM. Rapid fluctuation of the vaginal microbiota measured by Gram stain analysis. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(4):297–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bui TC, Scheurer ME, Pham VTT, Tran LTH, Hor LB, Vidrine DJ, et al. Intravaginal practices and genital human papillomavirus infection among female sex workers in Cambodia. Journal of Medical Virology. 2018;90(11):1765–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bui TC, Thai TN, Tran LT, Shete SS, Ramondetta LM, Basen-Engquist KM. Association Between Vaginal Douching and Genital Human Papillomavirus Infection Among Women in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2016;214(9):1370–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ekpenyong CE, Nyebuk ED, E EA. Vaginal douching behavior among young adult women and the perceived adverse health effects. Journal of Public Health and Epidemiology. 2014;6(5):182–91. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu T-Y, Hsiung CA, Chen C-A, Chou H-H, Ho C-M, Chien T-Y, et al. Post-coital vaginal douching is risky for non-regression of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion of the cervix. Gynecologic Oncology. 2011;120(3):449–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chu TY, Chang YC, Ding DC. Cervicovaginal secretions protect from human papillomavirus infection: effects of vaginal douching. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2013;52(2):241–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Crann SE, Cunningham S, Albert A, Money DM, O’Doherty KC. Vaginal health and hygiene practices and product use in Canada: a national cross-sectional survey. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18(1):52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De La Cruz N, Cornish DL, McCree-Hale R, Annang L, Grimley DM. Attitudes and Sociocultural Factors Influencing Vaginal Douching Behavior Among English-Speaking Latinas. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2009;33(4):558–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Donders GG, Gonzaga A, Marconi C, Donders F, Michiels T, Eggermont N, et al. Increased vaginal pH in Ugandan women: what does it indicate? Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2016;35(8):1297–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Erbil N, Alisarli A, Terzi HC, Ozdemir K, Kus Y. Vaginal douching practices among Turkish married women. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2012;73(2):152–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Esber A, Rao N, Norris A, Carr Reese P, Kandodo J, Nampandeni P, et al. Intravaginal Practices and Prevalence of Sexual and Reproductive Tract Infections Among Women in Rural Malawi. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 2016;43(12):750–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fashemi B, Delaney ML, Onderdonk AB, Fichorova RN. Effects of feminine hygiene products on the vaginal mucosal biome. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2013;24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gonzalez NL, O’Brien KM, D’Aloisio AA, Sandler DP, Weinberg CR. Douching, Talc Use, and Risk of Ovarian Cancer. Epidemiology. 2016;27(6):797–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guzel AI, Kuyumcuoglu U, Celik Y. Vaginal douching practice and related symptoms in a rural area of Turkey. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2011;284(5):1153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hacialioglu N, Nazik E, Kihc M. A descriptive study of douching practices in Turkish women. International Journal of Nursing Practice. 2009;15:57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hassan S, Chatwani AJ, Brovender H, Zane R, Valaoras T, Sobel JD. Douching for perceived vaginal odor with no infectious cause of vaginitis: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 2011;15(2):128–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Heng LS, Yatsuya H, Morita S, Sakamoto J. Vaginal douching in Cambodian women: its prevalence and association with vaginal candidiasis. J Epidemiol. 2010;20(1):70–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Klebanoff MA, Nansel TR, Brotman RM, Zhang J, Yu KF, Schwebke JR, et al. Personal hygienic behaviors and bacterial vaginosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(2):94–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li J, Jiang N, Yue X, Gong X. Vaginal douching and sexually transmitted infections among female sex workers: a cross-sectional study in three provinces in China. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(6):420–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Luong M-L, Libman M, Dahhou M, Chen MF, Kahn SR, Goulet L, et al. Vaginal douching, bacterial vaginosis, and spontaneous preterm birth. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2010;32(4):313–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mark H, Sherman SG, Nanda J, Chambers-Thomas T, Barnes M, Rompalo A. Populations at Risk Across the Lifespan: Case Studies: What has Changed about Vaginal Douching among African American Mothers and Daughters? Public Health Nursing. 2010;27(5):418–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Masese L, McClelland RS, Gitau R, Wanje G, Shafi J, Kashonga F, et al. A pilot study of the feasibility of a vaginal washing cessation intervention among Kenyan female sex workers. Sex Transm Infect. 2013;89(3):217–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McKee MD, Baquero M, Anderson MR, Alvarez A, Karasz A. Vaginal douching among Latinas: practices and meaning. Matern Child Health J. 2009;13(1):98–106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McKee MD, Baquero M, Fletcher J. Vaginal hygiene practices and perceptions among women in the urban Northeast. Women Health. 2009;49(4):321–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nwadioha S, Egah D, Banwat E, Egesie J, Onwuezobe I. Prevalence of bacterial vaginosis and its risk factors in HIV/AIDS patients with abnormal vaginal discharge. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. 2011;4(2):156–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ott MA, Ofner S, Fortenberry JD. Beyond Douching- Use of feminine hygiene products and STI risk among young women. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2009;6:1335–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pines HA, Semple SJ, Strathdee SA, Hendrix CW, Harvey-Vera A, Gorbach PM, et al. Vaginal washing and lubrication among female sex workers in the Mexico-US border region: implications for the development of vaginal PrEP for HIV prevention. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ranjit E, Raghubanshi BR, Maskey S, Parajuli P. Prevalence of Bacterial Vaginosis and Its Association with Risk Factors among Nonpregnant Women: A Hospital Based Study. Int J Microbiol. 2018;2018:8349601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Redding KS, Funkhouser E, Garces-Palacio IC, Person SD, Kempf MC, Scarinci IC. Vaginal douching among Latina immigrants. Matern Child Health J. 2010;14(2):274–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shaaban OM, Abbas AM, Moharram AM, Farhan MM, Hassanen IH. Does vaginal douching affect the type of candidal vulvovaginal infection? Med Mycol. 2015;53(8):817–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsai CS, Shepherd BE, Vermund SH. Does douching increase risk for sexually transmitted infections? A prospective study in high-risk adolescents. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200(1):38 e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.von Glehn MP, Sidon LU, Machado ER. Gynecological complaints and their associated factors among women in a family health-care clinic. J Family Med Prim Care. 2017;6(1):88–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang H, Chen RY, Ding G, Ma Y, Ma J, Jiao JH, et al. Prevalence and predictors of HIV infection among female sex workers in Kaiyuan City, Yunnan Province, China. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(2):162–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yanikkerem E, Yasayan A. Vaginal douching practice- Frequency, associated factors and relationship with vulvovaginal symptoms. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(4):387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zeng X, Zhang Y, Zhang T, Xue Y, Xu H, An R. Risk Factors of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis among Women of Reproductive Age in Xi’an: A Cross-Sectional Study. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9703754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Alcaide ML, Rodriguez VJ, Brown MR, Pallikkuth S, Arheart K, Martinez O, et al. High Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines in the Reproductive Tract of Women with BV and Engaging in Intravaginal Douching: A Cross-Sectional Study of Participants in the Women Interagency HIV Study. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2017;33(4):309–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Arfiputri DS, Hidayati AN, Handayani S, Ervianti E. Risk Factors of Vulvovaginal Candidiasis in Dermato-Venereology Outpatients Clinic of Soetomo General Hospital, Surabaya, Indonesia. Afr J Infect Dis. 2018;12(1 Suppl):90–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Low A, Didelot-Rousseau MN, Nagot N, Ouedraougo A, Clayton T, Konate I, et al. Cervical infection with human papillomavirus (HPV) 6 or 11 in high-risk women in Burkina Faso. Sex Transm Infect. 2010;86(5):342–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.McKee D, Baquero M, Anderson M, Karasz A. Vaginal hygiene and douching: perspectives of Hispanic men. Cult Health Sex. 2009;11(2):159–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anderson MR, McKee D, Yukes J, Alvarez A, Karasz A. An investigation of douching practices in the botanicas of the Bronx. Cult Health Sex. 2008;10(1):1–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brotman RM. Vaginal microbiome and sexually transmitted infections: an epidemiologic perspective. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(12):4610–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chen Y, Bruning E, Rubino J, Eder SE. Role of female intimate hygiene in vulvovaginal health: Global hygiene practives and product usage. Women’s Health. 2017;13(3):58–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Han L, Lv F, Xu P, Zhang G, Juniper NS, Wu Z. Microbicide acceptability among female sex workers in Beijing: Results from a pilot study. Journal of Women’s Health. 2009;18(9):1377–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hilber AM, Francis SC, Chersich M, Scott P, Redmond S, Bender N, et al. Intravaginal practices, vaginal infections and HIV acquisition: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2010;5(2):e9119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mandal G, Raina D, Balodi G. Vaginal douching - methods, practices, and health risks. Health Sciences Research. 2014;1(4):50–7. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nwadioha SI, Egah DZ, Alao OO, Iheanacho E. Risk factors for vaginal candidiasis among women attending primary health care centers of Jos, Nigeria. Journal of Clinical Medicine and Research. 2010;2(7):110–3. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Chatwani AJ, Hassan S, Rahimi S, Jeronis S, Dandolu V. Douching with Water Works device for perceived vaginal odor with or without complaints of discharge in women with no infectious cause of vaginitis: a pilot study. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2006;2006:95618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Roberts JN, Buck CB, Thompson CD, Kines R, Bernardo M, Choyke PL, et al. Genital transmission of HPV in a mouse model is potentiated by nonoxynol-9 and inhibited by carrageenan. Nat Med. 2007;13(7):857–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peterson L, Nanda K, Opoku BK, Ampofo WK, Owusu-Amoako M, Boakye AY, et al. SAVVY (C31G) gel for prevention of HIV infection in women: a Phase 3, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in Ghana. PLoS One. 2007;2(12):e1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nel A, Bekker LG, Bukusi E, Hellstrm E, Kotze P, Louw C, et al. Safety, Acceptability and Adherence of Dapivirine Vaginal Ring in a Microbicide Clinical Trial Conducted in Multiple Countries in Sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2016;11(3):e0147743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Nel A, Haazen W, Nuttall J, Romano J, Rosenberg Z, van Niekerk N. A safety and pharmacokinetic trial assessing delivery of dapivirine from a vaginal ring in healthy women. AIDS. 2014;28(10):1479–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.McConville C, Boyd P, Major I. Efficacy of Tenofovir 1% Vaginal Gel in Reducing the Risk of HIV-1 and HSV-2 Infection. Clin Med Insights Womens Health. 2014;7:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Giguere R, Rael CT, Sheinfil A, Balan IC, Brown W 3rd, Ho T, et al. Factors Supporting and Hindering Adherence to Rectal Microbicide Gel Use with Receptive Anal Intercourse in a Phase 2 Trial. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(2):388–401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Montgomery ET, Stadler J, Naidoo S, Katz AW, Laborde N, Garcia M, et al. Reasons for non-adherence to the dapivirine vaginal ring: Results of the MTN-032/AHA study. AIDS. 2018;32(11):1517–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Leyden JL, Dunlap F, Miller B, Winters P, Lebwohl M, Hecker D, et al. Finasteride in the treatment of men with frontal male pattern hair loss. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1999;40(6):930–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Williams HC, Dellavalle RP, Garner S. Acne vulgaris. The Lancet. 2012;379(9813):361–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ziba FA, Yakong VN, Asore RA, Frederickson K, Flynch M. Douching practices among women in the Bolgatanga municipality of the upper east region of Ghana. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kharsany ABM, Karim QA. HIV infection and AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: Current status, challenges and opportunities. The Open AIDS Journal. 2016;2016(10):34–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.U.N. Facts and figures - HIV and AIDS Geneva, Switzerland: UN Women; 2016. [Available from: http://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/hiv-and-aids/facts-and-figures. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Nel A, van Niekerk N, Kapiga S, Bekker LG, Gama C, Gill K, et al. Safety and Efficacy of a Dapivirine Vaginal Ring for HIV Prevention in Women. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2133–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Esim Buyukbayrak E, Kars B, Karsidag AY, Karadeniz BI, Kaymaz O, Gencer S, et al. Diagnosis of vulvovaginitis: comparison of clinical and microbiological diagnosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2010;282(5):515–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.D’Cruz OJ, Uckun FM. Vaginal microbicides and their delivery platforms. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2014;11(5):723–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]