Abstract

Skeletal muscle can regenerate from damage but is overwhelmed with extreme tissue loss, known as volumetric muscle loss (VML). Patients suffering from VML do not fully recover force output in the affected limb. Recent studies show that replacement tissue (i.e., autograph) into the VML defect site plus physical activity show promise for optimizing force recovery post-VML. The purpose of this study was to measure the effects of autologous repair and voluntary wheel running on force recovery post-VML. Thirty-two male Sprague–Dawley rats had 20% of their left tibialis anterior (LTA) excised then replaced and sutured into the intact muscle (autologous repair). The right tibialis anterior (RTA) acted as the contralateral control. Sixteen rats were given free access to a running wheel (Wheel) whereas the other 16 remained in a cage with the running wheel locked (Sed). At 2 and 8 weeks post-VML, the LTA underwent force testing; then the muscle was removed and morphological and gene expression analysis was conducted. At 2 weeks post-injury, normalized LTA force was 58% greater in the Wheel group compared to the Sed group. At 8 weeks post-VML, LTA force was similar between the Wheel and Sed groups but was still lower than the uninjured RTA. Gene expression analysis at 2 weeks post-VML showed the wheel groups had lower mRNA content of interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6 and tumour necrosis factor α compared to the Sed group. Overall, voluntary wheel running promoted early force recovery, but was not sufficient to fully restore force. The accentuated early force recovery is possibly due to a more pro-regenerative microenvironment.

Keywords: exercise, inflammation, regenerative medicine, rehabilitative medicine, VML

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Skeletal muscle is a highly plastic and regenerative tissue capable of self-repair following minor injuries such as strains and contusions. Repair of skeletal muscle involves the complex but coordinated processes of satellite cell activation and proliferation, myoblast proliferation and differentiation, inflammation, and extracellular matrix remodelling (Tidball, 2011). However, following large traumatic loss of muscle tissue, or volumetric muscle loss (VML), the endogenous repair mechanisms of skeletal muscle are overwhelmed, often leading to overt fibrosis and chronic inflammation at the site of injury (Kim et al., 2020). VML results in permanent functional deficits as well as cosmetic deficits (Grogan & Hsu, 2011; Terada et al., 2001). Skeletal muscle regeneration is a process that is highly regulated and involves coordination of the inflammatory response, fibrotic response and myogenesis for optimal growth and repair. Chronic inflammation is associated with VML (Nuutila et al., 2017) and increased gene expression of inflammatory modulators have been reported at various time points following VML (Corona et al. 2018). Our laboratory has demonstrated elevated expression of inflammatory cytokines TGF-β and interleukin (IL)-1β following VML (Kim et al., 2020). Persistent inflammation inhibits myogenesis and enhances the fibrotic response, which inhibits recovery of skeletal muscle (Perandini et al., 2018).

There is currently no standard of care for VML that restores function to the injured skeletal muscle. Recently, research groups developing regenerative therapies have investigated the use of biological scaffolds, decellularized tissue and autologous tissue implantation in order to promote satellite cell migration into the defect site (Corona et al., 2013a; Das et al., 2020; Garg et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2020). Despite these efforts, it appears implantation alone is insufficient to elicit a robust regenerative response possibly due to lack of a proper stimulus to promote cell migration and growth factor release. Therefore, recent studies have employed physical activity as part of VML treatment in order to provide the necessary stimulus to promote and mediate proper regeneration in small animal VML models (Nakayama et al., 2018; Quarta et al., 2017). These studies demonstrated that exercise along with implantation of bioconstructs increased innervation and accelerated myogenesis and force recovery following VML (Nakayama et al., 2018; Quarta et al., 2017).

Rehabilitation and physical activity currently are the main therapeutic strategy for VML management for both military and civilian populations and have shown encouraging results in terms of limb functional recovery (Aurora et al., 2014). However, the observed functional improvements are most likely due to an exercise-induced adaptation allowing for improved force transmission across the injury site and not because of de novo tissue contribution. Similar results have been observed in small animal models where voluntary wheel running has been demonstrated to promote innervation, increase isometric torque output, and increase myofibre cross-sectional area (Nakayama et al., 2018; Quarta et al., 2017). Exercise has also been shown to reduce collagen cross-linking, allowing for improved mechanotransduction across the scar region and to resident satellite cells, and to increase satellite cell proliferation and differentiation (Carroll et al., 2015). Interestingly, these beneficial effects appear to be sensitive to VML repair as demonstrated by several reports using different scaffold and implant modalities with the most encouraging results produced by muscle autograft treatment (Kasukonis et al., 2016). We define VML repair specifically as the replacement of lost muscle tissue with another substance (i.e., autologous muscle tissue).

Still unanswered is whether exercise following VML repair will positively affect recovery via attenuation of the chronic inflammatory response. To that end, a rat model of VML familiar to our group was used to investigate the effect of exercise in the form of voluntary wheel running following VML repair using an autograft muscle plug. Exercise transiently increases a variety of factors such as muscle perfusion, nutrient supply to the injury site and myokine release from skeletal muscle, creating a pro-regenerative microenvironment. Chronic inflammation can serve to depress this pro-regenerative microenvironment. The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that voluntary wheel running following autologous repair of VML will hasten functional recovery by attenuating inflammation and ultimately creating an environment that is more pro-regenerative than what would be present in scaffold-alone strategies.

2 ∣. METHODS

2.1 ∣. Animals and experimental design

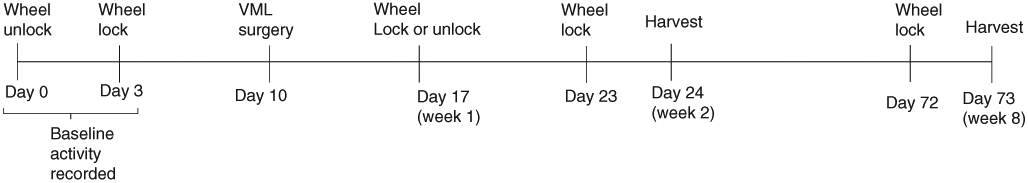

Male, Sprague-Dawley rats (3-4 months old) were purchased from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN, USA) and used for this study. Rats were allowed ad libitum access to normal chow and water throughout the duration of the study. They were individually housed in cages that contained running wheels that remained locked and kept in a climate-controlled room with automatic 12–12 h light-dark cycle. Animals were housed in a room maintained between 20 and 26°C with relative humidity of 30–70% as per American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines. The experimental design can be seen in Figure 1. Once rats reached the desired weight of 300 g, running wheels were unlocked, and rats were allowed ad libitum wheel access for 72 h to assess baseline running distance. Baseline activity was recorded as the average distance during the last 24 h of the 3 day period of wheel access. At the conclusion of the 72 h of wheel access, wheels were locked. Seven days following wheel lock, VML surgery was performed on the left tibialis anterior (LTA) of all rats. One week post-surgery, wheels either remained locked (Sedentary, Sed) or unlocked (voluntary wheel running, Wheel) for a period of either 1 week or 7 weeks. Two weeks post-surgery, tissue harvest was conducted on 16 rats (n = 8 Sed, n = 8 Wheel). Eight weeks post-surgery, tissue harvest was conducted on 16 rats (n = 8 Sed, n = 8 Wheel). Twenty-four hours before tissue harvest, wheels were locked on the Wheel rats in order to avoid acute variations in voluntary wheel running between rats. All animal care and use within this protocol was approved by the University of Arkansas Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol no. 17075).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the experimental design

2.2 ∣. VML surgery

VML surgery was performed as previously described (Kim et al., 2016). Rats were anaesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane (2% in oxygen) during surgery. The lower left hindlimb was shaved and sterilized using three rotations of alcohol and betadine. A 1–2 cm longitudinal incision was made over the belly of the LTA (VML) cutting through the deep fascia to expose the belly of the LTA. A surgical marker was used to draw a line along the length of the medial one-third of the LTA. Next, a muscle biopsy punch (approximately 8 mm × 3 mm) was used to cause a defect equalling approximately 20% of the LTA by weight. There were no differences in the defect tissue weight among all four groups. The defect tissue averaged ~101.7 mg and was approximately 18% of the LTA weight at time of harvest. Once the defect was removed, it was weighed and replaced in the defect site properly aligning with the line made from the surgical marker. The contralateral limb (right tibialis anterior, RTA; Con) served as an internal control for comparison. Polypropylene sutures were used to anchor the defect to the intact LTA tissue using two sutures on both the distal and proximal ends of the defect. Vicryl thread was used to suture the fascia and then the cutaneous layers together to completely close the wound. Immediately post-surgery, 24 h after surgery, and 48 h after surgery, rats received a 0.1 ml subcutaneous injection of 0.3 g/ml buprenorphine to reduce pain-associated distress. Additionally, rats were also given carprofen in the form of either Rodent MD’s Rimadyl tablets (2 mg/tablet) (Bio Serv, MD150-2, Flemington, NJ) or Medigel CPF packs (ClearH2O, 74-05-5022, Portland, ME) for additional pain management post-surgery. Animals were euthanized 2 weeks or 8 weeks post-VML surgery.

2.3 ∣. In Vivo contractile torque measurement

Contractile torque measurement was performed as previously described (Kim et al., 2016). Rats were anaesthetized by inhalation of isoflurane (2% in oxygen). The legs were shaved and sterilized with three rotations of betadine and alcohol wipes. A transverse incision was made on the distal, anterior lower limb to expose the distal tendons of the TA, extensor digitalis longus (EDL) and extensor hallucis longus (EHL). Tenotomy of the EDL and EHL tendons was conducted leaving the TA tendon intact and isolated. The rat was positioned so the knee was at a 90° angle, and the leg running parallel with the force platform. The ankle and pad of the foot were secured onto the platform of the electrophysiology machine using surgical tape. Percutaneous needle electrodes were inserted in the anterior compartment of the TA and the peroneal nerve was stimulated. Optimal voltage (2–5 V) was determined using a series of tetanic contractions (100 Hz, 0.1 ms pulse width, 400 ms train). Average peak tetanic force for each animal was determined from the average of five contractions. Torque was then determined from the force measurement by using the length of the standard lever arm, which gives the voltage scale factor. The length of the lever arm was 40 mm. To minimize muscle fatigue, 60 s rest periods were taken between contraction cycles.

2.4 ∣. Tissue harvest

Following in vivo contractile torque measurement, the TA and EDL were extracted from each leg and weighed. Following muscle extraction, animals were killed by removal of the heart. The LTA (VML) had a complete transverse cut effectively dividing the defect area into two equal halves and subsequently the TA was sectioned into three parts: (1) the distal half of the TA containing half of the defect site (later used for histology), (2) the isolated defect site from the proximal TA, and (3) the remaining proximal TA tissue without the defect. The proximal half of the TA (including the proximal half of the defect) was immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. The distal half of the TA (used for histology) was immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane the stored at −80°C. The proximal, isolated defect and proximal TA were used for gene expression. Rats were killed by exsanguination by removal of the heart. All collected tissue was stored at −80°C until processed for analysis.

2.5 ∣. RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR

RNA was extracted from the RTA and defect tissue of the LTA with Trizol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) as previously described (Perry et al., 2016). Total RNA was isolated using the Purelink mRNA mini kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was reversed transcribed from 1 μg of total RNA using the Superscript Vilo cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for a final result of a 1:20 ratio of RNA to total volume. This final volume was then brought to a 1:100 dilution factor. Real-time PCR was performed, and results analysed by using the StepOne Real-Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). cDNA was amplified in a 25 μl reaction containing appropriate probes for Ki67, MyoD, Myogenin, CyclinD1, Pax7, IGF-1, CD68, Arginase-1, IFNγ, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1β and Myostatin, and Taqman Gene Expression Mastermix (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were incubated at 95°C for 4 min, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation, annealing and extension at 95, 55 and 72°C, respectively. TaqMan fluorescence was measured at the end of the extension step of each cycle. Cycle threshold (Ct) was determined, and the ΔCt value was calculated as the difference between the Ct value and the 18s Ct value. Final quantification of gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method Ct = [ΔCt (calibrator) – ΔCt (sample)]. Relative quantification was calculated as 2−ΔΔCt.

2.6 ∣. Statistical analysis

All data were analysed using SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Results were reported as means ± SD. For torque output and body mass, a two-way ANOVA was performed to analyse main effects of voluntary wheel running and time and whether there were any interactions between the independent variables. When a significant interaction was detected, differences among individual means were assessed using Tukey’s post hoc analysis. This was done for both the uninjured and injured limbs. For all other variables, a two-way ANOVA was performed to analyse main effects of injury and voluntary wheel running and to detect any interactions between the independent variables. When a significant interaction was detected, differences among individual means were assessed using Tukey’s post hoc analysis. A preplanned comparison between the 2 and 8-week control groups was performed with Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was set at P ≤ 0.05.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. Body and muscle mass

All body mass and muscle mass data can be found in Table 1. Body mass was greater at 8-weeks compared to 2-weeks independent of treatment (P ≤ 0.05). Body mass was lower in the wheel running groups compared to the sedentary groups independent of time (P ≤ 0.05). At 2 and 8 weeks post-VML, TA muscle mass was lower in the injured LTA compared to the uninjured RTA independent of exercise (P ≤ 0.05).

TABLE 1.

Body mass and tibialis anterior muscle mass 2 and 8 weeks post-volumetric muscle loss injury

| 2 Week |

8 Week |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sedentary | Wheel | Sedentary | Wheel | |

| Body mass (g)a | 367.0 ± 16.4 | 344.8 ± 13.8 | 394.8 ± 16.9 | 375.3 ± 20.9 |

| RTA (uninjured) mass (mg) | 642.2 ± 37.5 | 606.9 ± 42.5 | 677.8 ± 87.2 | 712.1 ± 40.5 |

| LTA (injured) mass (mg)b | 564.1 ± 100.6 | 547.7 ± 97.2 | 571.8 ± 60.3 | 551.5 ± 153.6 |

| TA defect (mg) | 103.5 ± 14.2 | 101.1 ± 17.5 | 104.1 ± 12.2 | 98.6 ± 8.5 |

Values are means ± SD. LTA, left tibialis anterior (injured); RTA, right tibialis anterior (uninjured); TA, tibialis anterior.

Main effects of time, exercise

main effect of injury; P ≤ 0.05.

3.2 ∣. Wheel running data

At the conclusion of the three-day baseline testing, rats averaged of 726 ± 73 m/day. At 2 weeks post-injury, rats averaged of 763 ± 87 m/day. At 8 weeks post-injury, rats averaged a significantly higher distance of 1023 ± 104 m/day (P ≤ 0.05). Regardless of the time point, rats followed the typical nocturnal activity pattern observed in previous studies.

3.3 ∣. In vivo peak tetanic contractile torque

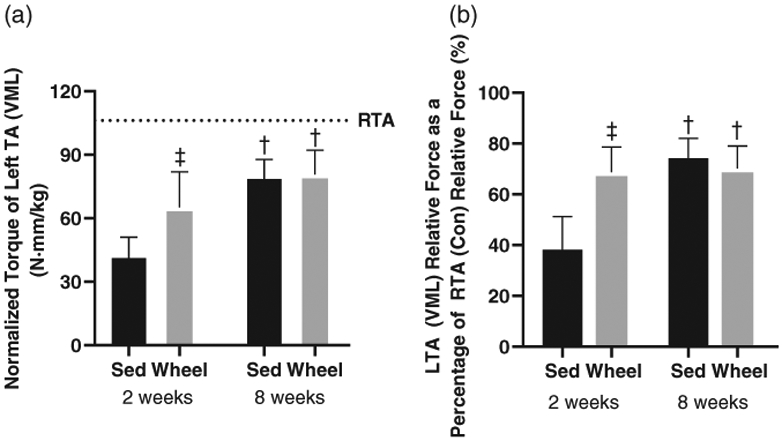

At 2 weeks or 8 weeks post-VML, there were no differences in normalized torque output (N mm/kg body mass) in the uninjured RTA between the sedentary and wheel running groups. Two weeks post-VML, the injured LTA in the wheel running group produced 58.3% more normalized torque than the injured LTA in the sedentary group (Figure 2a, P ≤ 0.05). At 2 weeks post-VML, the injured LTA normalized torque as a percentage of uninjured RTA normalized torque was 62% higher in the wheel running group compared to the sedentary group (Figure 2b, P ≤ 0.05). At 8 weeks, there were no differences in injured LTA normalized torque between the sedentary and wheel running groups (Figure 2a). At 8 weeks post-VML, normalized torque of the injured LTA as a percentage of the uninjured RTA was not different between the sedentary and wheel running groups (Figure 2b). Normalized torque output at 8 weeks was greater than normalized torque output at 2 weeks independent of wheel running (Figure 2a; P ≤ 0.05).

FIGURE 2.

In vivo isometric peak torque measurements of the LTA at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML. (a) Peak isometric torque of the LTA normalized to body mass 2 and 8 weeks post-VML in sedentary (Sed) and voluntary wheel running (Wheel) animals. (b) Peak isometric torque of the injured LTA normalized to the uninjured RTA at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML in sedentary (Sed) and voluntary wheel running (Wheel) animals. Dashed line is a reference point for uninjured right tibialis anterior (RTA). Data are means ± SD. †Difference between Control or VML limbs; ‡difference between sedentary or wheel running groups. P < 0.05. n = 3–8 per group

3.4 ∣. Cell cycle regulators

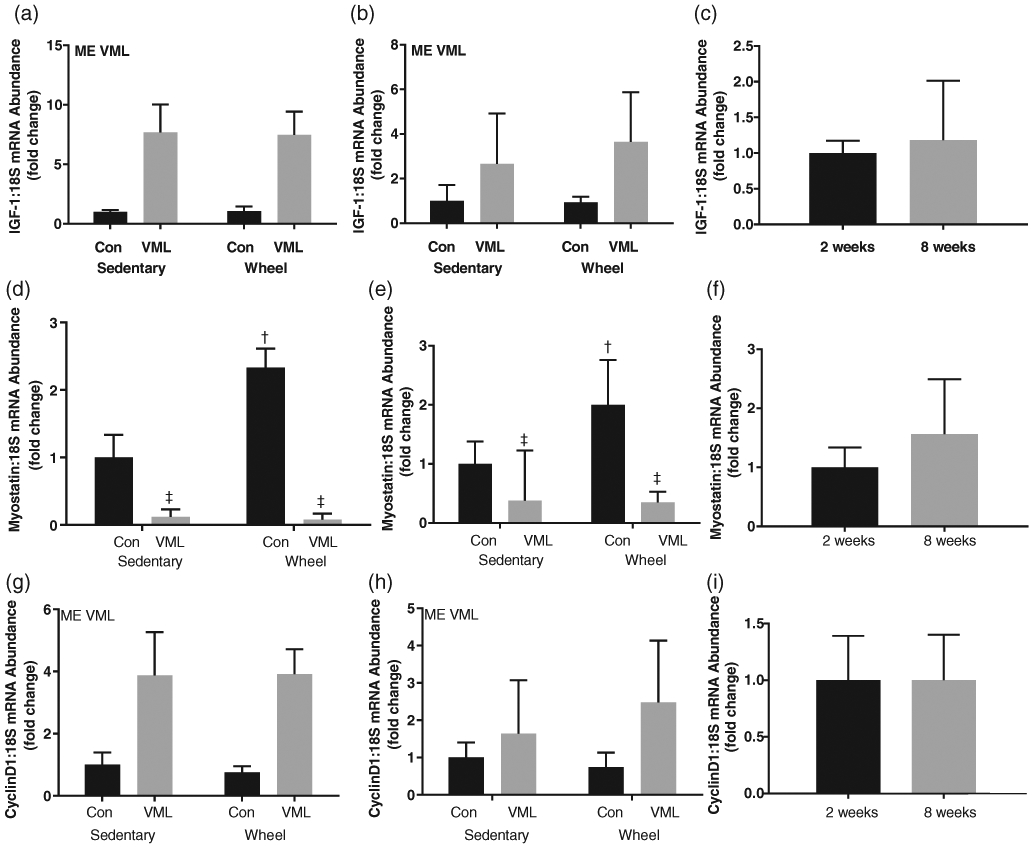

There were no differences in the uninjured RTA gene expression of IGF-1, Myostatin and CyclinD1 between the 2- and 8-week time points (Figure 3c, f, i). At both 2 and 8 weeks post-VML, the injured LTA had greater IGF-1 (Figure 3a, b; P < 0.05) and CyclinD1 (Figure 3g, h; P ≤ 0.05) mRNA abundance than the uninjured RTA independent of wheel running. At both 2 and 8 weeks post-VML, the injured LTA had lower Myostatin mRNA abundance than the uninjured RTA independent of wheel running (Figure 3d, e; P ≤ 0.05).

FIGURE 3.

mRNA abundance, normalized to 18S, of cell cycle regulators. (a) IGF-1 mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (b) IGF-1 mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (c) IGF-1 mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML); (d) Myostatin mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (e) Myostatin mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (f) Myostatin mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML); (g) CyclinD1 mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; H) CyclinD1 mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (i) CyclinD1 mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML). Data are means ± SD. n = 3–8 per group. ME, main effect; †difference between Control or VML limbs; ‡difference between sedentary or wheel running groups; P < 0.05

3.5 ∣. Satellite cell markers

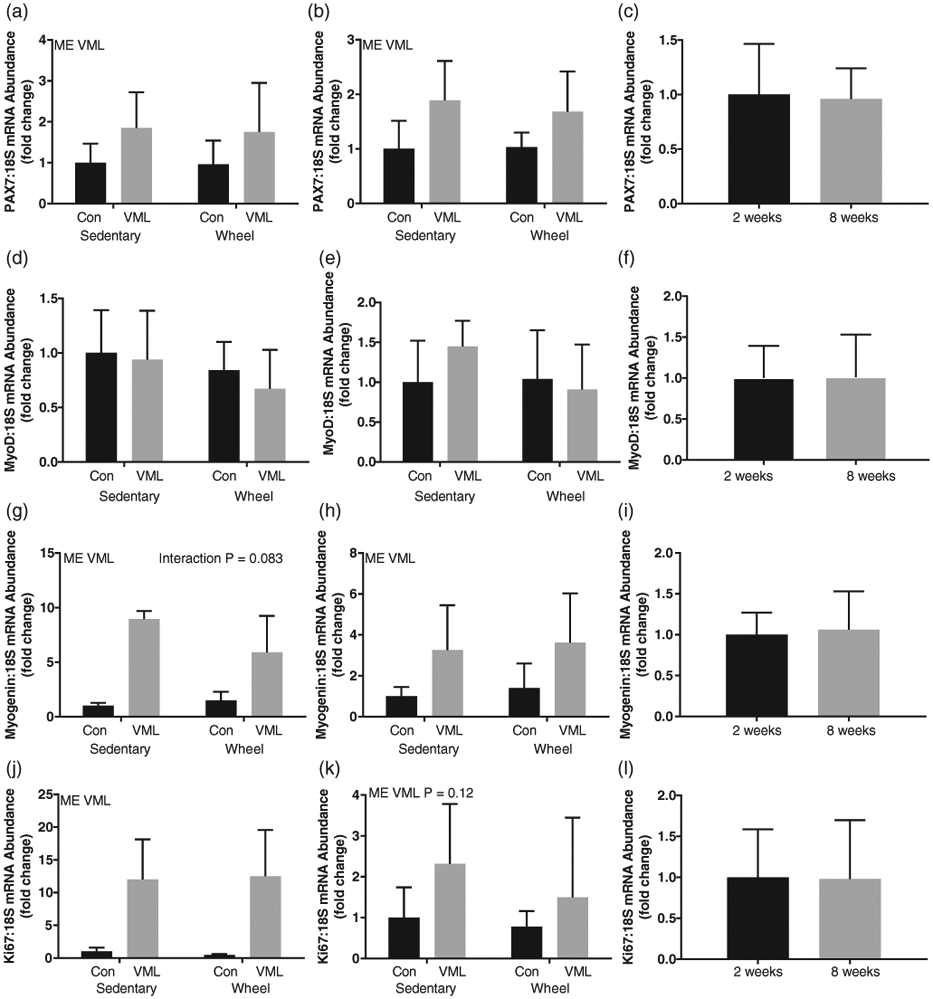

There were no differences in the uninjured RTA gene expression of Pax7, MyoD, MyoG, and Ki67 between the 2- and 8-week time points (Figure 4c, f, i, l). At both 2 and 8 weeks post-VML, the injured LTA had greater Pax7 (Figure 4a, b; P ≤ 0.05) and MyoG (Figure 4g, h; P ≤ 0.05) mRNA abundance than the uninjured RTA independent of wheel running. No differences in MyoD gene expression were observed between the RTA and LTA at either time point (Figure 4d, e). At 2 weeks post-VML, the injured LTA had greater Ki67 mRNA abundance than the uninjured RTA independent of wheel running (Figure 4j; P ≤ 0.05). There were no differences in mRNA abundance of Ki67 between the uninjured RTA and injured LTA at 8 weeks post-VML (Figure 4k).

FIGURE 4.

mRNA abundance, normalized to 18S, of satellite cell markers. (a) Pax7 mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (b) Pax7 mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (c) Pax7 mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML); (d) MyoD mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (e) MyoD mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (f) MyoD mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML); (g) Myogenin mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (h) Myogenin mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (i) Myogenin mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML; (j) Ki67 mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (k) Ki67 mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (l) Ki67 mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML). Data are means ± SD. n = 3–8 per group. ME, main effect; †difference between Control or VML limbs; ‡difference within Sedentary or Wheel groups; P < 0.05

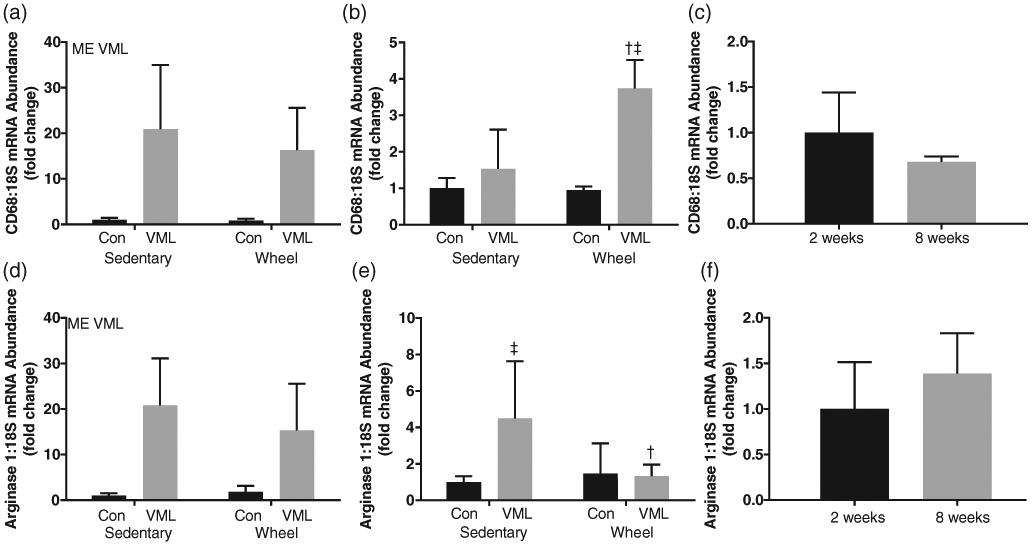

3.6 ∣. Macrophage markers

There were no differences in the uninjured RTA gene expression of CD68 and Arginase-1 between the 2- and 8-week time points (Figure 5c, f, i). At 2 weeks post-VML, the injured LTA had greater CD68 mRNA abundance than the uninjured RTA independent of wheel running (Figure 5a; P ≤ 0.05). At 8 weeks, there was an interaction between injury and wheel running on CD68 mRNA abundance. Though no differences were detected within the sedentary group, CD68 mRNA abundance was ~3.5-fold higher in the injured LTA compared to the uninjured RTA of the wheel running group (Figure 5b, P ≤ 0.05). CD68 mRNA abundance was ~2.2-fold higher in the injured LTA of the wheel running group compared to the injured LTA in the sedentary group (Figure 5b, P ≤ 0.05).

FIGURE 5.

mRNA abundance, normalized to 18S, of macrophage markers. (a) CD68 mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (b) CD68 mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (c) CD68 mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML); (d) Arginase 1 mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (e) Arginase mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (f) Arginase 1 mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML). Data are means ± SD. n = 3–8 per group. ME, main effect; †difference between Control or VML limbs; ‡difference within Sedentary or Wheel groups; P < 0.05

At 2 weeks post-VML, the injured LTA had greater Arginase-1 mRNA abundance than the uninjured RTA independent of wheel running (Figure 5d; P ≤ 0.05). At 8 weeks, there was an interaction between injury and wheel running on Arginase-1 mRNA abundance. Arginase-1 mRNA abundance was ~4-fold higher in the injured LTA compared to the uninjured RTA of the sedentary group (Figure 5d, P ≤ 0.05). There was no difference in Arginase-1 mRNA abundance in the wheel running group. Arginase-1 mRNA abundance was ~4-fold higher in the injured LTA of the sedentary group compared to the injured LTA of the wheel running group (Figure 5e, P ≤ 0.05).

3.7 ∣. Inflammatory response markers

There were no differences in the uninjured RTA gene expression of IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6, and IFNγ between the 2- and 8-week time points (Figure 6c, f, i, n). At 2 weeks, there was an interaction between injury and exercise on IL-1β mRNA abundance. In the sedentary group, IL-1β mRNA abundance was ~4-fold higher in the injured LTA compared to the uninjured RTA (Figure 6a, P ≤ 0.05). There was no difference in IL-1β mRNA abundance in the wheel running group. IL-1β mRNA abundance was ~1.5-fold higher in the injured LTA of the sedentary group compared to the injured LTA of the wheel running group (Figure 6a, P ≤ 0.05). Differences in IL-1β mRNA abundance were not detected at the 8-week time point.

FIGURE 6.

mRNA abundance, normalized to 18S, of inflammatory response markers. (a) IL-1β mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (b) IL-1β mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (c) IL-1β mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML); (d) TNF-α mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (e) TNF-α mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (f) TNF-α mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML); (g) IL-6 mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (h) IL-6 mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (i) IL-6 mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML; (j) IFNγ mRNA abundance 2 weeks post-VML; (k) IFNγ mRNA abundance 8 weeks post-VML; (l) IFNγ mRNA abundance control comparison (control limb of sedentary group at 2 and 8 weeks post-VML). Data are means ± SD. n = 3–8 per group. ME, main effect; †difference within Control or VML limbs; ‡difference within Sedentary or Wheel groups; P < 0.05

At 2 weeks, there was an interaction between injury and wheel running on TNF-α mRNA abundance. Though no differences were detected within the wheel running group, TNF-α mRNA abundance was ~4-fold higher in the injured LTA compared to the uninjured RTA of the sedentary group (Figure 6d, P ≤ 0.05). TNF-α mRNA abundance was ~4-fold higher in the injured LTA of the sedentary group compared to the injured LTA of the exercise group (Figure 6d, P ≤ 0.05). There were no differences in TNF-α mRNA abundance detected at the 8-week time point between any groups (Figure 6e).

At 2 weeks, there was an interaction between injury and wheel running on IL-6 mRNA abundance. IL-6 mRNA abundance was 19-fold higher in the injured LTA compared to the uninjured RTA (Figure 6g, P ≤ 0.05). There was no difference in IL-6 mRNA abundance between the uninjured RTA and injured LTA in the wheel running group (Figure 6g). At 8 weeks, there was no differences in IL-6 mRNA abundance between any groups (Figure 6h). At 2 and 8 weeks post-VML, the injured LTA had greater IFNγ mRNA abundance than the uninjured RTA independent of wheel running (Figure 6l, m, P ≤ 0.05).

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

Our research explored whether exercise following VML repair will positively affect torque recovery via attenuation of the chronic inflammatory response. We are the first to demonstrate that combined regenerative and rehabilitative techniques resulted in an accentuated recovery of torque 2 weeks post-VML. Coinciding with this accelerated torque recovery, we observed a reduced inflammatory response post-VML. This study is one of very few to utilize complete autologous repair along with exercise in the form of voluntary wheel running to promote torque recovery in a rat model of VML. The accentuated torque recovery at 2 weeks post-VML was transient and by 8 weeks post-VML the difference in torque recovery between the exercise and sedentary groups was lost. Exercise was not associated with accentuated satellite cell activity or de novo tissue formation suggesting the accelerated torque recovery occurred independent of these processes. Taken together, these results demonstrate that while autologous repair and exercise did not increase the overall torque production compared to sedentary controls it did accelerate the recovery process. This could have meaningful clinical implications.

We were successful in removing the same size TA defect from each animal. With TA defect size not being different between groups, this suggests the injury was similar between groups. VML is associated with a decrease in muscle mass. We have demonstrated thatTA muscle mass does not return to normal 8 weeks post-VML (Kim et al., 2020). Our data here are consistent with the data from that study. We did notice a transient hypertrophy of the EDL muscle at the 2-week time point. This is due possibly to the EDL compensating for the loss of function from the TA muscle. From the muscle mass data, it does not appear the accentuation in muscle torque at 2 weeks was due to an increase in muscle mass in the exercise group.

VML studies have consistently observed a chronic, dysregulated inflammatory response in the injury site undergoing muscle regeneration (Corona et al., 2018). Our data are consistent with these observations, in that at 2 weeks post-VML we demonstrate elevated gene expression of the classic pro-inflammatory cytokines tumour necrosis factor α (TNF-α), IL-6 and IL-1β. Chronic inflammation has been shown to preclude proper muscle regeneration and promote a pro-fibrotic environment (Perandini et al., 2018). We observed at 2 weeks post-VML that access to wheel training attenuated the pro-inflammatory response as indicated by a reduction in the expression of the pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β. It is well established that exercise promotes a reduction in the inflammatory environment within skeletal muscle (Gleeson et al., 2011). These early modifications to the inflammatory response may partially explain the observed torque recovery in the wheel running group as a pro-inflammatory environment has been correlated with a decrease in skeletal muscle contractile output (McNicol et al., 2010).

Macrophages can be classified as M1, which are present during the inflammatory stage of skeletal muscle regeneration, or M2, which accumulate at the site of injury once necrotic tissue has been removed and participate in the regeneration and remodelling response (Martins et al., 2020). There were differential responses in our markers of macrophage polarization at the 8-week time point. Interestingly, the sedentary group exhibited high expression levels of arginase-1, a marker of M2 macrophages, while expression of CD68, a marker of M1 macrophages, was not different from control. However, the wheel running group had the opposite response with an increase in CD68 gene expression post-VML and no change in arginase-1 gene expression post-VML. This observation could explain why torque recovery did not continue in the wheel running group. By 8 weeks post-VML we would expect the macrophages present to be primarily of the M2 type which aids in the regenerative response. Instead M1 macrophages were most likely present at the site of injury.

Wheel running has been demonstrated to increase satellite cell number as well as myonuclei per fibre without causing hypertrophy (Brooks et al., 2018 ; Kurosaka et al., 2009). Pax7 is a common satellite cell marker and Ki67 is a proliferation marker. We demonstrate increases in these markers post-VML, which is consistent with other studies (Aguilar et al., 2018). Wheel running appeared to have no effect on the expression of genes related to satellite cell activity even though torque recovery was observed. This observation leads to two possible explanations: (1) physical activity promotes torque recovery via the strengthening of the muscle surrounding the injury site, and/or (2) physical activity affects elements of torque recovery within the defect area other than satellite cell activity. In a similar VML model using autologous minced muscle grafts, wheel running was demonstrated to improve the muscle surrounding the VML injury site, which resulted in significantly increased torque recovery (Corona et al., 2013a). Regarding the former, it has been well established that VML injuries impact not only the regenerative capacity of the muscle but also several other key events involved in normal muscle regeneration including fibrosis, inflammation and innervation (Aurora et al., 2014; Corona et al., 2016; Corona et al., 2013b).

Future research employing this model for VML treatment will want to consider the fact that the tibialis anterior muscle is not the primary mover in wheel running. Therefore, wheel running may not be sufficient in eliciting satellite cell activity though it does promote torque recovery following VML injury, especially in the early stages of recovery. We did not have a wheel-running-only group and thus this study cannot draw the conclusion that the combined autologous repair and wheel running is superior to wheel running alone. Additionally, VML has potent effects on the extracellular matrix of skeletal muscle. While not a focus of the current study, examining the ECM during recovery from VML and how voluntary wheel running impacts it warrants further consideration. Physical activity that minimizes the usage of the injured muscle may be advantageous as exercise-induced damage could potentially overwhelm the recovery process. Also, of interest is possibly a transition into a mixed exercise model utilizing both aerobic and resistance exercise. As observed in this study, aerobic activity elicited significant recovery to torque output early on but then plateaued at the later time point. Incorporation of a hypertrophic exercise regime may help augment torque production with continued recovery extending into the late stages of healing.

4.1 ∣. Conclusion

In summary, this is the first study to incorporate complete autologous graft repair with voluntary wheel running to promote functional recovery in a rat model of VML. Access to wheel running appeared to promote early-phase recovery of torque production, but the effect was lost by 8 weeks post-injury. Wheel running caused a delay in the inflammatory response early on allowing for robust functional recovery but was ultimately susceptible to the pro-inflammatory response by 8 weeks. Taken together the data suggest that physical activity may be a viable early phase adjunct to autologous repair of VML for aiding torque recovery.

New Findings.

• What is the central question of this study?

Following large traumatic loss of muscle tissue (volumetric muscle loss; VML), permanent functional and cosmetic deficits present themselves and regenerative therapies alone have not been able to generate a robust regenerative response: how does the addition of rehabilitative therapies affects the regenerative response?

• What is the main finding and its importance?

Using exercise along with autologous muscle repair, we demonstrated accelerated muscle force recovery response post-VML. The accentuated force recovery 2 weeks post-VML would allow patients to return home sooner than allowed with current therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Exercise Science Research Center staff for administrative contributions as well as Katarina Bejarano for her technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15AR064481 as well as the Arkansas Biosciences Institute.

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (T.A.W.) upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- Aguilar CA, Greising SM, Watts A, Goldman SM, Peragallo C, Zook C, Larouche J, & Corona BT (2018). Multiscale analysis of a regenerative therapy for treatment of volumetric muscle loss injury. Cell Death Discovery, 4(1), 33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurora A, Garg K, Corona BT, & Walters TJ (2014). Physical rehabilitation improves muscle function following volumetric muscle loss injury. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 6(1), 41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks MJ, Hajira A, Mohamed JS, & Alway SE (2018). Voluntary wheel running increases satellite cell abundance and improves recovery from disuse in gastrocnemius muscles from mice. Journal of Applied Physiology, 124(6), 1616–1628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll CC, Martineau K, Arthur KA, Huynh RT, Volper BD, & Broderick TL (2015). The effect of chronic treadmill exercise and acetaminophen on collagen and cross-linking in rat skeletal muscle and heart. American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 308(4), R294–R299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona BT, Garg K, Ward CL, McDaniel JS, Walters TJ, & Rathbone CR (2013a). Autologous minced muscle grafts: A tissue engineering therapy for the volumetric loss of skeletal muscle. American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology, 305(7), C761–C775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona BT, Rivera JC, & Greising SM(2018). Inflammatory and physiological consequences of debridement of fibrous tissue after volumetric muscle loss injury. Clinical and Translational Science, 11(2), 208–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona BT, Wenke JC, & Ward CL (2016). Pathophysiology of volumetric muscle loss injury. Cells, Tissues, Organs, 202(3–4), 180–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corona BT, Wu X, Ward CL, McDaniel JS, Rathbone CR, & Walters TJ (2013b). The promotion of a functional fibrosis in skeletal muscle with volumetric muscle loss injury following the transplantation of muscle-ECM. Biomaterials, 34(13), 3324–3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Browne KD, Laimo FA, Maggiore JC, Hilman MC, Kaisaier H, Aguilar CA, Ali ZS, Mourkioti F, & Cullen DK (2020). Pre-innervated tissue-engineered muscle promotes a pro-regenerative microenvironment following volumetric muscle loss. Communication Biology, 3(1), 330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garg K, Ward CL, & Corona BT (2014). Asynchronous inflammation and myogenic cell migration limit muscle tissue regeneration mediated by a cellular scaffolds. Inflammation and Cell Signaling, 1(4), e530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson M, Bishop NC, Stensel DJ, Lindley MR, Mastana SS, & Nimmo MA (2011). The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: Mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nature Reviews. Immunology, 11(9), 607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grogan BF, & Hsu JR (2011). Volumetric muscle loss. Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, 19(Suppl 1), S35–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasukonis B, Kim J, Brown L, Jones J, Ahmadi S, Washington T, & Wolchok J (2016). Codelivery of infusion decellularized skeletal muscle with minced muscle autografts improved recovery from volumetric muscle loss injury in a rat model. Tissue Engineering Part A, 22(19–20), 1151–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JT, Kasukonis BM, Brown LA, Washington TA, & Wolchok JC (2016). Recovery from volumetric muscle loss injury: A comparison between young and aged rats. Experimental Gerontology, 83, 37–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JT, Kasukonis B, Dunlap G, Perry R, Washington T, & Wolchok JC (2020). Regenerative repair of volumetric muscle loss injury is sensitive to age. Tissue Engineering Part A, 26(1–2), 3–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaka M, Naito H, Ogura Y, Kojima A, Goto K, & Katamoto S (2009). Effects of voluntary wheel running on satellite cells in the rat plantaris muscle. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine, 8(1), 51–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins L, Gallo CC, Honda TSB, Alves PT, Stilhano RS, Rosa DS, Koh TJ, & Han SW (2020). Skeletal muscle healing by M1-like macrophages produced by transient expression of exogenous GM-CSF. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 11(1), 473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNicol FJ, Hoyland JA, Cooper RG, & Carlson GL (2010). Skeletal muscle contractile properties and proinflammatory cytokine gene expression in human endotoxaemia. British Journal of Surgery, 97(3), 434–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama KH, Alcazar C, Yang G, Quarta M, Paine P, Doan L, Davies A, Rando TA, & Huang NF (2018). Rehabilitative exercise and spatially patterned nanofibrillar scaffolds enhance vascularization and innervation following volumetric muscle loss. NPJ Regenerative Medicine, 3, 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuutila K, Sakthivel D, Kruse C, Tran P, Giatsidis G, & Sinha I (2017). Gene expression profiling of skeletal muscle after volumetric muscle loss. Wound Repair and Regeneration, 25(3), 408–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perandini LA, Chimin P, Lutkemeyer DDS, & Camara NOS (2018). Chronic inflammation in skeletal muscle impairs satellite cells function during regeneration: Can physical exercise restore the satellite cell niche? FEBS Journal, 285(11), 1973–1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry RA Jr., Brown LA, Lee DE, Brown JL, Baum JI, Greene NP, & Washington TA (2016). Differential effects of leucine supplementation in young and aged mice at the onset of skeletal muscle regeneration. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 157, 7–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quarta M, Cromie M, Chacon R, Blonigan J, Garcia V, Akimenko I, Hamer M, Paine P, Stok M, Shrager JB, & Rando TA (2017). Bioengineered constructs combined with exercise enhance stem cell-mediated treatment of volumetric muscle loss. Nature Communications, 8, 15613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada N, Takayama S, Yamada H, & Seki T (2001). Muscle repair after a transsection injury with development of a gap: An experimental study in rats. Scandinavian Journal of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery and Hand Surgery, 35(3), 233–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidball JG (2011). Mechanisms of muscle injury, repair, and regeneration. Comprehensive Physiology, 1(4), 2029–2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (T.A.W.) upon reasonable request.