Abstract

Most bacteria are quiescent, typically as a result of nutrient limitation. In order to minimize energy consumption during this potentially prolonged state, quiescent bacteria substantially attenuate protein synthesis, the most energetically costly cellular process. Ribosomes in quiescent bacteria are present as dimers of two 70S ribosomes. Dimerization is dependent on a single protein, Hibernation Promoting Factor (HPF), that binds the ribosome in the mRNA channel. This interaction indicates that dimers are inactive, suggesting that HPF inhibits translation. However, we observe that HPF does not significantly affect protein synthesis in vivo suggesting that dimerization is a consequence of inactivity, not the cause. The HPF-dimer interaction further implies that re-initiation of translation when the bacteria exit quiescence requires dimer resolution. We show that ribosome dimers quickly resolve in the presence of nutrients, and this resolution is dependent on transcription, indicating that mRNA synthesis is required for dimer resolution. Finally, we observe that ectopic HPF expression in growing cells where mRNA is abundant does not significantly effect protein synthesis despite stimulating dimer formation, suggesting that dimerization is dynamic. Thus, the extensive transcription that occurs in response to nutrient availability rapidly re-activates the translational apparatus of a quiescent cell and induces dimer resolution.

Keywords: protein synthesis, translation, stationary phase, ribosome hibernation

Introduction

Many microbes exist in a non-proliferating quiescent state that facilitates survival during the periods of nutrient limitation that characterize many environments (Lennon & Jones, 2011, Rittershaus et al., 2013). A major challenge facing quiescent cells is how to minimize energy consumption so as to maximize the limited available resources over a potentially extended time (Bergkessel et al., 2016). The most energy intensive metabolic process in a bacterial cell is protein synthesis, accounting for as much as ~70% of total energy consumption (Russell & Cook, 1995). Consistently, bacteria such as Bacillus subtilis substantially reduce protein synthesis when they exit exponential growth (Diez et al., 2020, Bernhardt et al., 2003). The ribosome is itself the most energetically costly macromolecular machine to synthesize, and it must be protected from degradation during this period of limited de novo ribosome synthesis. Importantly, this protection must be compatible with efficient re-initiation of protein synthesis when conditions improve (Remigi et al., 2019).

During active growth, cells contain 70S ribosomes engaged with mRNA, as well as free small (30S) and large (50S) ribosomal subunits (Green & Noller, 1997, Voorhees & Ramakrishnan, 2013). However, when bacteria enter stationary phase, two 70S ribosomes interact to form a 100S ribosome dimer as observed by ultracentrifugation of bacterial lysates on a sucrose gradient (Tissieres & Watson, 1958, Wada et al., 1990) or in situ by cryo-electron tomography (Ortiz et al., 2010). In phylogenetically diverse bacteria, 100S ribosome dimers are the predominant ribosome configuration in stationary phase (Ortiz et al., 2010, Prossliner et al., 2018) and ribosome dimerization is important for re-growth after stress and starvation (Puri et al., 2014, Akanuma et al., 2016) and for pathogenesis (Kline et al., 2015, McKay & Portnoy, 2015, Fazzino et al., 2015). Dimerization is mediated by a member of the ubiquitous Hibernation Promoting Factor (HPF) protein family that are typically expressed during post-exponential growth or stationary phase. Gamma-proteobacteria such as Escherichia coli encode a short form of HPF that, along with the small protein RMF, binds the ribosome to form the 100S dimer (Wada et al., 1990, Wada et al., 2000, Wada et al., 1995). Gram-positive bacteria, such as B. subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus, do not contain an RMF homolog, but instead encode a long form of HPF with two domains separated by a sequence with an as yet undetermined structure (Matzov et al., 2019). Loss of function mutations in HPF lead to increased ribosome degradation in species including Mycobacterium smegmatis (Trauner et al., 2012), S. aureus (Basu & Yap, 2016) and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. (Akiyama et al., 2017).

The C-terminal domain of each long-form HPF monomer mediates dimerization (Beckert et al., 2017, Franken et al., 2017). We recently demonstrated that in B. subtilis, the absence of HPF leads to loss of the essential ribosomal protein S2, which is the point of contact of the C-terminal domain (Feaga et al., 2020). Similar to HPF proteins from diverse species, the N-terminal domain of B. subtilis HPF binds the 70S ribosome at a site that overlaps both the A- and P- tRNA binding sites and the mRNA channel (Beckert et al., 2017). Therefore, HPF-bound ribosome dimers are incompatible with active translation, leading to the hypothesis that the role of HPF is to attenuate protein synthesis under physiological conditions (Prossliner et al., 2018).

Here, we show that contrary to the prediction of this model, dimerization is most likely a consequence of translation inactivity, not the cause. The structure of HPF-bound ribosome dimers implies that dimers must be quickly resolved in the presence of nutrient-replete conditions so that the cell can resume protein synthesis. We observe that dimers are indeed quickly resolved upon dilution of stationary phase cells into fresh medium. We further demonstrate that this resolution is blocked by the addition of an inhibitor of mRNA synthesis, suggesting that conversion of inactive dimers to active ribosomes is mediated by transcription. Finally, ectopic HPF expression in growing cells has no measurable effect on protein synthesis despite stimulating substantial dimer formation, indicating that dimers may be transient in vivo with the implication that dimerization is more dynamic than previously appreciated.

Results

HPF does not affect protein synthesis in vivo.

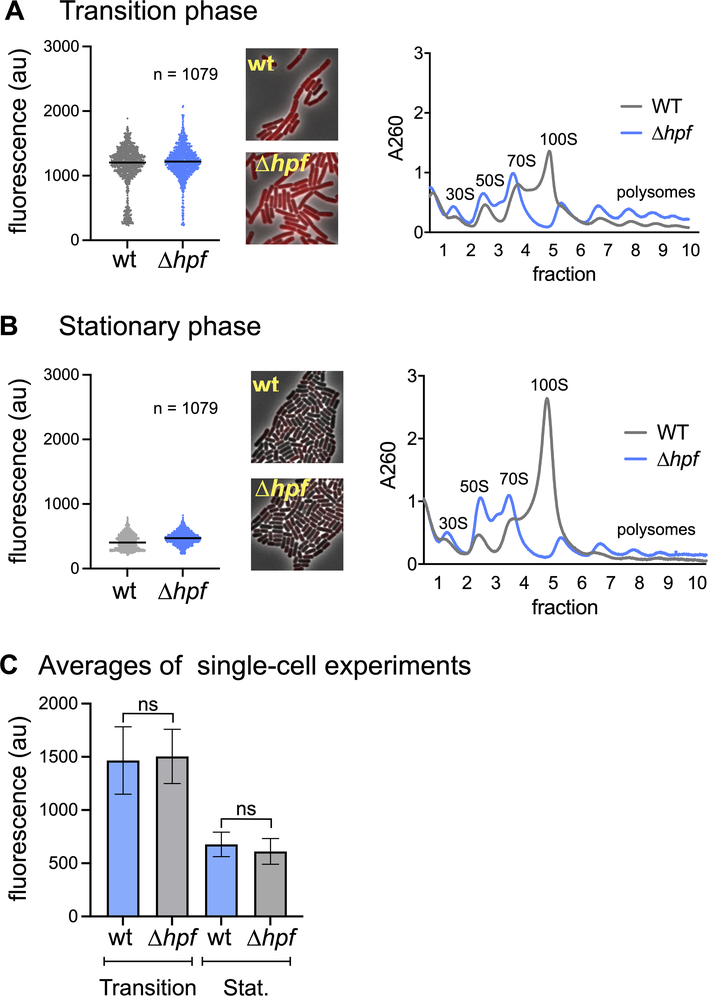

We compared protein synthesis in wild-type and Δhpf strains by monitoring incorporation of an alkyne-modified derivative of puromycin (OPP) that is subsequently linked to an azide-modified fluorescent dye by click chemistry (Liu et al., 2012). Puromycin is a tRNA analog that is covalently linked the C-terminus of nascent peptides as they are being synthesized by the ribosome. OPP-labeling enables the quantitation of protein synthesis in single cells under amino acid replete conditions (Diez et al., 2020). We labeled cultures of wild-type and Δhpf cells with OPP under conditions where B. subtilis HPF is expressed (Feaga et al., 2020, Drzewiecki et al., 1998). At the departure from exponential growth when cells enter transition phase (OD600 = 2.5), dimers are observed in the wild-type (Fig. 1A), but the incorporation of OPP by wild-type or Δhpf cells was not significantly different between biological replicates of the experiment (p>0.1, unpaired, two-tailed t-test) (Fig. 1C). As expected, cells from a wild-type culture exhibited less protein synthesis at a stationary phase time point (OD600 = 6.0) (Fig. 1B) as compared to the transition phase time point (Fig. 1A). However, the Δhpf strain also exhibited a similar decrease, indicating that the reduction in protein synthesis was not dependent on HPF. Three biological replicates of this experiment were performed on different days (Fig. S1A). The averages of these experiments are shown (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1. HPF does not affect protein synthesis in vivo.

(Left) Wild-type or Δhpf single cells were assayed for protein synthesis during transition phase (OD600~2.5) (A) and during stationary phase (OD600~6.0) (B) by OPP incorporation. Three biological replicates were performed and a representative experiment (1079 cells) is shown, along with representative microscope images. (Right) An aliquot of cells was harvested in parallel to assay the presence of dimers by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. All biological replicates are included in Fig. S1. (C) Averages of these three biological replicates are shown. Not-significant (ns) indicates a p-value >0.1. Error bars indicate standard deviation.

OPP-incorporation measures abundance of nascent polypeptides in the P-site of the ribosome. 35S-methionine incorporation monitors peptidyl transfer. To confirm these measurements of protein synthesis by a different method, we grew cells to stationary phase in S7 minimal media (OD600 of ~6.0), and then added 35S-methionine to radiolabel newly synthesized proteins. Following cell lysis, proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography (Fig. S1B). Again, we did not detect a significant difference in levels of protein synthesis in the wild-type parent in comparison with the Δhpf mutant strain (Fig. S1B) (unpaired two-tailed T-test). Thus, even though the abundance of ribosome dimers increased in the wild-type strain in stationary phase as compared to transition phase, correlating with a reduction in protein synthesis (Fig. 1A and B), these two different assays of protein synthesis suggest that dimer formation, per se, does not affect global protein synthesis.

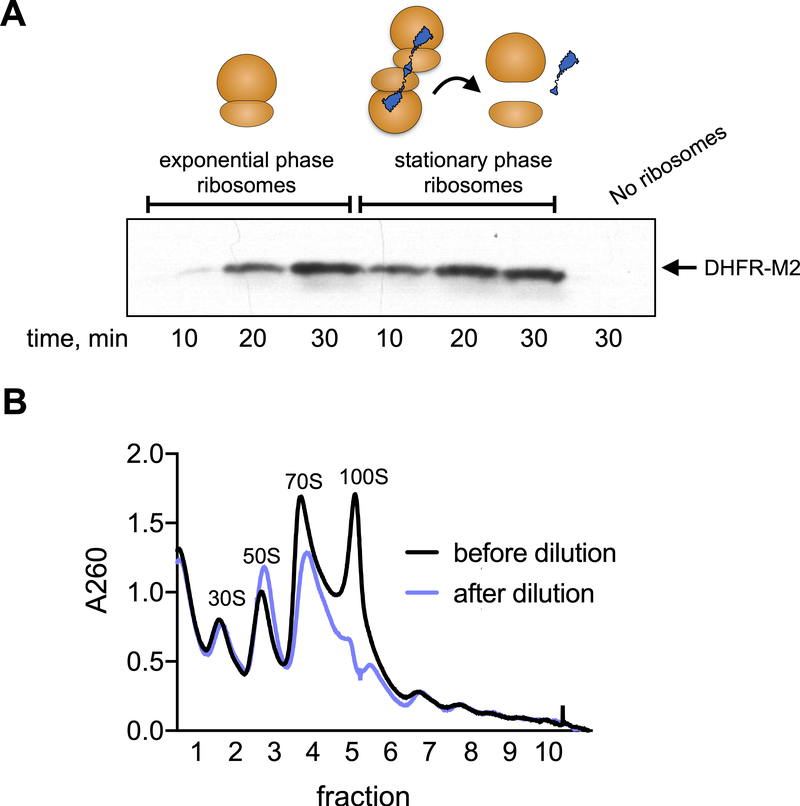

Ribosome dimers resolve within minutes of entry into fresh media

One explanation for a lack of an effect of HPF-dependent ribosome dimer formation on protein synthesis in vivo is that 100S dimers are quickly resolved into translationally competent complexes free of HPF. Consistently, addition of HPF-bound ribosome dimers to a purified ribosome-free in vitro system stimulated protein synthesis within minutes (Fig 2A, (Feaga et al., 2020)) suggesting that 100S dimers are efficiently resolved in a purified system. Therefore, we also examined the dynamics of dimer resolution in vivo by growing B. subtilis to stationary phase and then transferring an aliquot of this culture into fresh media. After five minutes in fresh media with aeration, cells were harvested, lysed, and ribosomes from both the stationary phase culture and the newly diluted culture were analyzed. Ribosomes from the stationary phase culture were present in the dimer conformation, as expected, whereas ribosomes from cells that had been transferred into fresh media were present as 30S, 50S, and 70S assemblies, with very few ribosome dimers observed (Fig. 2B). This observation demonstrates that, similar to E. coli (Aiso et al., 2005), ribosome dimers in B. subtilis are rapidly resolved upon entry into fresh media.

Fig. 2. Ribosome dimers resolve within minutes of dilution into fresh media.

(A) Ribosomes purified from exponential phase or stationary phase cells were added to a ribosome-free PURE system. Exponential phase ribosomes were present in 30S, 50S and 70S configurations. Stationary phase ribosomes were present as dimers when added to the reaction. Production of DHFR-M2 was monitored by western blot using an anti-M2 antibody. A ribosome-free reaction is shown as a negative control. (B) Wild-type (JDB1772) cells were grown to stationary phase in LB (OD600 ~6). An aliquot of this culture was diluted 1:4 in fresh LB medium and aerated at 37˚C for 5 min. The stationary phase culture (black, ‘before dilution’) and the diluted culture (blue, ‘after dilution’) were harvested, lysed, and resolved on a 10%−40% sucrose density gradient.

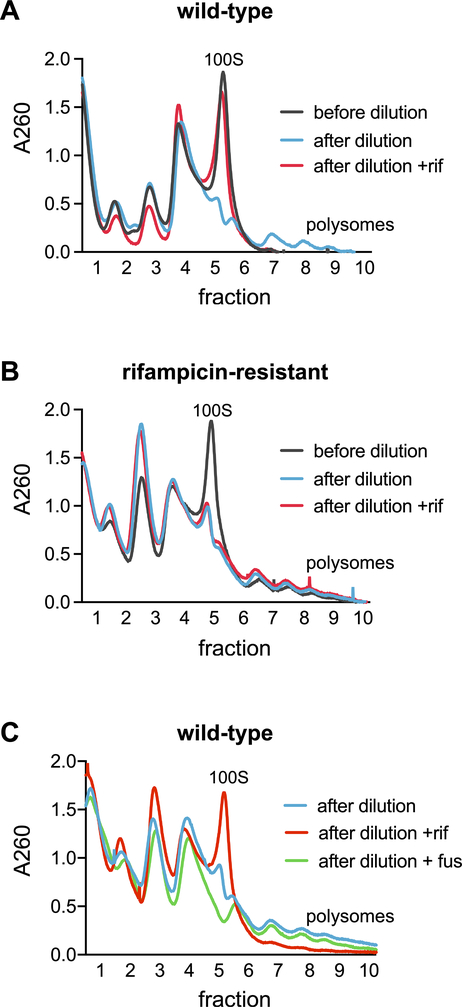

Inhibiting transcription inhibits resolution of ribosome dimers

What mechanism might account for the rapid resolution of ribosome dimers? HPF binds the 70S ribosome at a site overlapping the mRNA channel (Beckert et al., 2017 ) suggesting that mRNA and HPF are competitive for binding. Thus, mRNA produced when cells resume growth could outcompete HPF for ribosome binding, and therefore decrease ribosome dimerization. To test whether transcription is necessary for the resolution of ribosome dimers, we transferred a portion of a stationary phase culture to fresh media in the presence or absence of the transcription inhibitor rifampicin. After 5 minutes, the cultures were harvested, and lysates were resolved by sucrose density gradient centrifugation. When the culture was transferred to fresh media without rifampicin, dimers were resolved as observed previously. In contrast, when the culture was transferred to fresh media containing rifampicin, ribosome dimer abundance was similar to that observed in the parent stationary phase culture (Fig. 3A). This effect was not observed in a strain carrying a mutation in rpoB that renders the strain resistant to rifampicin (Fig. 3B), confirming that the observed effect on dimer abundance was dependent on the ability of rifampicin to directly inhibit transcription. To confirm that the effect of rifampicin was not due to the indirect reduction of protein synthesis that occurs when transcription is inhibited, we tested whether the translation inhibitor fusidic acid (Zhang et al., 2015) affects dimer resolution in vivo. Cultures were grown to stationary phase, and then diluted into fresh LB media containing rifampicin, fusidic acid, or no drug. In contrast to rifampicin, fusidic acid did not prevent the resolution of ribosome dimers (Fig. 3C), demonstrating that rifampicin was preventing dimer resolution by inhibiting the synthesis of mRNA and that protein synthesis, including that required for ribosome biogenesis, is not necessary.

Figure 3. Rifampicin treatment prevents resolution of ribosome dimers.

(A) Wild-type (JDB1772) cells were grown to stationary phase (OD600 ~6) and diluted 1:4 in fresh media with or without 5 μg/mL rifampicin. (B) Rifampicin resistant cells (JDB4420) were grown to stationary phase (black, ‘before dilution’) and diluted 1:4 in fresh media (blue, ‘after dilution’) or with rifampicin. (red; ‘after dilution +rif’) (C) Wild-type (JDB1772) cells were grown to stationary phase and diluted 1:4 in fresh media containing no drug (blue, ‘after dilution’), rifampicin (red, ‘after dilution +rif’), or fusidic acid (green, ‘after dilution +fus’).

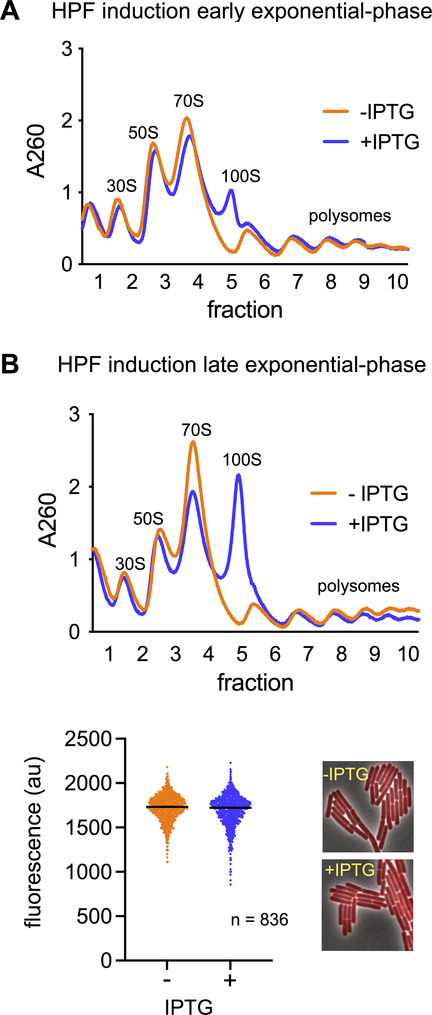

Ectopic expression of HPF does not attenuate protein synthesis during exponential phase

Together, our observations that dimers are quickly resolved under nutrient-replete conditions (Fig. 2B) and that dimer resolution depends on transcription (Fig. 3A) suggest that ectopic expression of HPF in transcriptionally active cells would not affect protein synthesis. To examine this possibility, we constructed a strain expressing HPF under the control of an inducible promoter. The ectopically expressed HPF was functional, as revealed by a 100S peak in density fractionated lysate derived from the induced culture (Fig. 4A and B). This strain contains an Δhpf deletion at the endogenous locus so only the effect of ectopically expressed HPF is assayed. Fewer dimers were produced if HPF was induced in early log phase (OD600 0.45) (Fig. 4A) than in late log phase (OD600 0.8) (Fig. 4B), consistent with our observation that rapidly growing cells produce fewer dimers (Fig. 3). We assayed OPP incorporation in cells induced in late log phase (Fig. 4B), since this condition produced the most ribosome dimers. We also determined that the ectopically expressed HPF was expressed to a level similar to that observed during stationary phase (Fig. S2A). As above, we also assayed protein synthesis using both 35S-methionine incorporation (Fig. S2B). Both methods revealed that induction of HPF did not exert a statistically significant effect over biological replicates (Fig. 4B, S2B) (unpaired, two-tailed T-test). Thus, ectopic expression of HPF in exponential phase has no measurable effect on protein synthesis in these assays.

Figure 4. Ectopic expression of HPF does not significantly affect protein synthesis.

(A) Cells from strain JDB4228 (Δhpf amyE::Phyperspank-hpf) were grown in LB to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.45) and induced with IPTG for 20 minutes. Cell lysate was harvested and resolved on a 10%−40% sucrose gradient. (B) Cells from strain JDB4228 were grown in LB to OD600 ~0.8, induced with IPTG for 20 min and labeled with OPP. Cells were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. A representative of two independent experiments is shown (836 cells measured). An aliquot of cells from this experiment grown in the presence (blue) or absence (orange) of IPTG were harvested and the abundance of ribosome dimers was assayed by sucrose density gradient centrifugation.

Discussion

Structures of 100S ribosome dimers show that HPF binding overlaps with the binding sites of essential translation factors (Matzov et al., 2019, Beckert et al., 2017, Polikanov et al., 2012, Franken et al., 2017). For example, the position of B. subtilis HPF on the 100S ribosome dimer overlaps the mRNA channel and the A and P tRNA binding sites (Beckert et al., 2017). HPF binding would sterically hinder these interactions and therefore it has been hypothesized that HPF inhibits translation. However, we find that wild-type and Δhpf strains exhibit similar protein synthesis activities (Fig. 1A, B) and ectopic expression of HPF does not inhibit protein synthesis even though it stimulates dimer formation (Fig. 4A, B). How can these results be reconciled with the structural data clearly suggesting that dimers are translationally inactive? Our observations that ribosome dimers are resolved quickly in vivo upon increased nutrient availability (Fig. 2B) and that in vitro translation is not affected by the addition of purified ribosome dimers, which are bound to HPF upon addition to the reaction (Fig. 2A), suggests that dimers in cells are rapidly converted into active 70S monomers free of HPF. Such behavior would reconcile our in vivo protein synthesis data with the 100S dimer structure, and suggests that dimerization is a consequence of translation inhibition. Our observation that inhibition of mRNA synthesis blocks this resolution (Fig. 3A) suggests that HPF binds the ribosome when the mRNA:HPF ratio is favorable. This situation is present under post-exponential conditions where HPF is expressed and transcription is attenuated (Planson et al., 2020). In cells that are transcriptionally active, HPF does not compete with mRNA sufficiently to inhibit translation. Thus, resolution of inactive 100S ribosome dimers to active 70S ribosomes upon nutrient availability is a direct consequence of the rapid increase in transcription that occurs during this transition (Planson et al., 2020).

Rapid dimer resolution in vivo implies that inactive (dimer) and active ribosome configurations (70S/50S/30S) exist in a dynamic equilibrium in cells, and that dimer disassembly is likely a passive process in B. subtilis. We propose that the relative stoichiometry of mRNA::HPF shifts this equilibrium either towards inactive dimers or toward active ribosomes. Several aspects of this speculative mechanism including its in vivo or in vitro kinetics and the specific pathway in vivo of dimer resolution are not clear. For example, does the 100S dimer initially resolve into two inactive 70S monomers or into a dimer of 30S subunits still bound by HPF? Given the absence of techniques to quantitatively analyze the dynamics of ribosome dimer assembly in vivo, answers to these questions await future technological development.

Presumably, competition between mRNA and HPF for binding to the mRNA channel would result in such an equilibrium. How might this competition take place? During initiation, the 30S Initiation Complex (30S IC) forms when the mRNA, the initiator N-formyl-methionyl-transfer RNA (fMet-tRNAfMet) and the 30S subunit are brought together by the Initiation Factors IF1, IF2 and IF3 (Gualerzi & Pon, 2015). Thus, the HPF::mRNA stoichiometry would directly affect both initiation of translation and inversely ribosome dimerization. The E.coli pY protein, which is structurally homologous to the N-terminal domain of HPF, also binds the mRNA channel and pY competes with the binding of fMet-tRNAfMet to the ribosome (Vila-Sanjurjo et al., 2004). Interestingly, Nsp1 of SARS-Cov2, which is important for down-regulating host protein synthesis during infection, similarly binds the mRNA channel of the eukaryotic ribosome. Nsp1 competes with RNA downstream of the start codon to bind the 40S subunit and the protein is unable to associate rapidly with 80S ribosomes assembled on an mRNA (Lapointe et al., 2020). Nsp1 also induces endonucleolytic cleavage of host mRNAs (Kamitani et al., 2006), a mechanism that would similarly favor Nsp1 binding as our experiments that used an inhibitor of transcription to favor HPF in the HPF:mRNA stoichiometry, thereby stabilizing dimers (Fig. 3).

If HPF binding is a consequence of the attenuation of transcription, the competition between HPF and mRNA implies that HPF is preferentially associating with ribosomes that are inactive. Consistently, we observed a 100S ribosome dimer peak in exponentially growing cells expressing HPF even though there was no measurable decrease in protein synthesis (Fig. 4A, B). This observation suggests that a substantial pool of non-translating ribosomes exists in actively growing cells as has been proposed (Remigi et al., 2019, Dai et al., 2016, Li et al., 2018). One way to increase the fraction of inactive ribosomes is by inhibiting translation initiation. We and others have shown that the alarmone (p)ppGpp, which is produced during post-exponential growth, inhibits IF2 (Milon et al., 2006, Vinogradova et al., 2020, Diez et al., 2020). Since IF2 mediates the isomerization of the 30S pre-initiation complex and promotes the subsequent association of the large 50S subunit (Caban et al., 2017), inhibition of IF2 by (p)ppGpp would likely increase the abundance free 30S subunits that are capable of association with HPF (Wishnia et al., 1975).

(p)ppGpp also regulates the expression of HPF in both B. subtilis and E.coli suggesting that HPF expression and dimer formation may be directly coupled to conditions that do not favor active translation such as high (p)ppGpp synthetic activity (Diez et al., 2020). In Gram-positive bacteria such as B. subtilis, (p)ppGpp synthesis is mediated by the dual function (p)ppGpp synthase/hydrolase RelA, which associates with the ribosome, and two non-ribosome associated synthases, SasA (RelP) and SasB (RelQ) that predominantly synthesize pGpp and ppGpp, respectively (Gaca et al., 2015, Irving & Corrigan, 2018, Yang et al., 2020). SasB is allosterically activated by pppGpp (Steinchen et al., 2015), and this allosteric activation is inhibited by mRNA (Beljantseva et al., 2017). Thus, increases in transcription would reduce synthesis of ppGpp, a known inhibitor of translation (Diez et al., 2020), and stimulate ribosome dimer resolution (Fig. 5). Although recent evidence suggests that transcription and translation in B. subtilis are not directly coupled during active growth (Johnson et al., 2020), our experiments are consistent with a functional coupling at least under nutrient limitation, as has been suggested for E. coli synthesizing (p)ppGpp (Chen & Fredrick, 2020). Thus, when transcription is attenuated and HPF is expressed during nutrient limitation, the equilibrium between HPF and mRNA would favor 100S dimer formation (Fig. 5A). In the presence of sufficient nutrients, increases in transcription would shift this equilibrium to favor 70S ribosomes and thereby stimulate translation (Fig. 5B).

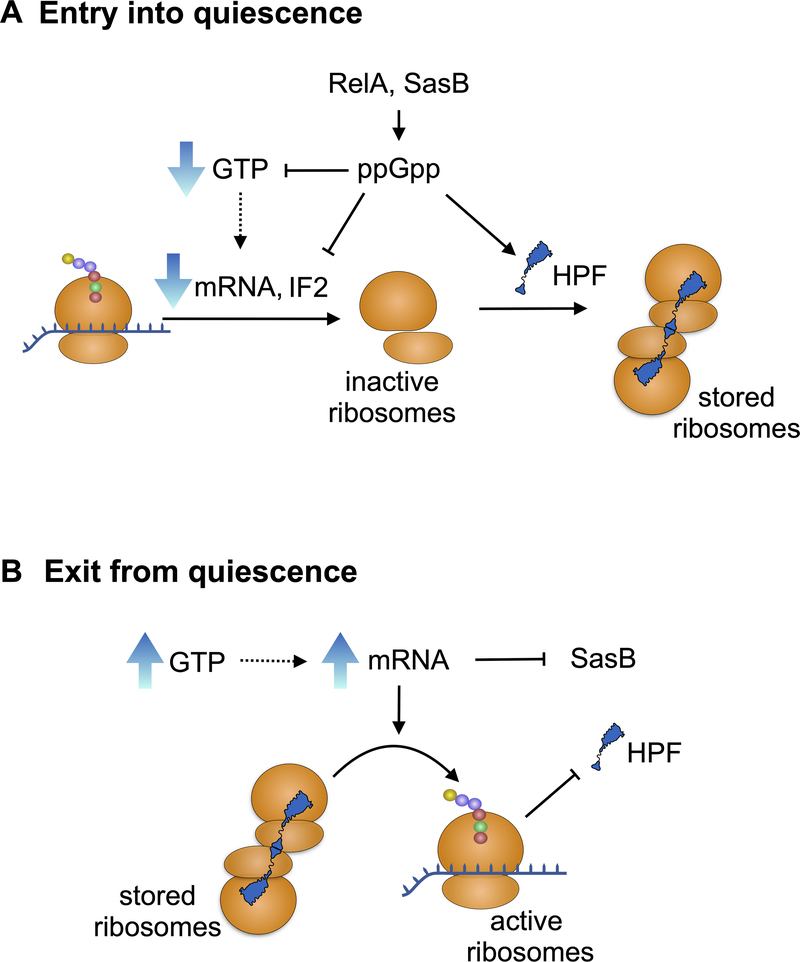

Fig. 5. Transcriptional regulation of ribosome dimer formation during entry into and exit from quiescence.

Entry into quiescence (top): Following departure from exponential growth, the (p)ppGpp synthases RelA and SasB become activated and expressed, respectively, resulting in an increase in [ppGpp] (Nanamiya et al., 2008). ppGpp attenuates translation, by inhibiting IF2 (Diez et al., 2020), and attenuates transcription (Krasny & Gourse, 2004, Gourse et al., 2018) by causing a decrease in [GTP] (Anderson et al., 2020). Therefore, the rise in [ppGpp] results in increased abundance of 30S and 50S subunits that can form empty 70S ribosomes. In addition, ppGpp induces the expression of HPF (Tagami et al., 2012), which forms 100S ribosome dimers from the empty 70S ribosomes. Exit from quiescence (bottom): In the presence of sufficient nutrients [GTP] increases (Planson et al., 2020, Lopez, 1982), stimulating transcription (Krasny & Gourse, 2004, Gourse et al., 2018). mRNA production also inhibits SasB (Beljantseva et al., 2017), preventing its synthesis of ppGpp and thereby facilitating the rise in [GTP] that promotes further transcription. The increased transcription alters the mRNA:HPF stoichiometry, leading to the resolution of the 100S dimers to active 70S monosomes. This could be a consequence of shifting the equilibrium of monomer::dimer as the result of increased 30SIC formation in the presence of mRNA.

Several other candidate mechanisms have been proposed for dimer resolution. For example, the GTPase HflX dissociates 100S dimers in vitro (Basu & Yap, 2017). However, the effect of HflX is not necessary for dimer resolution as an in vitro system lacking HflX is capable of mediating the resolution of ribosome dimers (Fig. 2A) and strains lacking hflX do not exhibit substantially increased dimer abundance in vivo (Basu & Yap, 2017). Alternatively, in S. aureus, ribosome-recycling factor (RRF) and the GTPase EF-G, which together act to recycle 70S ribosomes in post-termination complex, also resolve 100S ribosomes in a GTP-dependent fashion (Basu et al., 2020). Interestingly, HPF is expressed in S. aureus during exponential growth (Basu & Yap, 2016, Ueta et al., 2010), so EF-G and RRF may resolve ribosome dimers that are subsequently prevented from re-forming because of the presence of mRNA. In contrast, B. subtilis EF-G does not appear to be required for dimer splitting since addition of fusidic acid did not prevent dimer resolution during re-growth (Fig. 3C). However, EF-G catalyzes both elongation and ribosome recycling during translation, and the inhibitory effect of fusidic acid on elongation is stronger (Zhang et al., 2015). Since fusidic acid stalls ribosomes on mRNA, the effect of fusidic acid on dimer recycling could be masked by an increase in stalled ribosomes. In either case, these results support a model in which mRNA is sufficient to block HPF binding and dimer formation.

Our experiments suggest that resolution of ribosome dimers involves a competition between HPF and mRNA for ribosome binding, presumably mediated by the N-terminal domain of HPF that contacts the mRNA channel of the ribosome. An unresolved question is the role of the C-terminal domain of HPF in dimer resolution. This domain mediates dimerization and interacts with ribosomal protein S2 (Kato et al., 2010, Beckert et al., 2017). Intriguingly, S2 is also a point of direct interaction between the ribosome and RNA polymerase ω subunit in the so-called expressome (Kohler et al., 2017, Demo et al., 2017, Webster et al., 2020). Alternatively, the transcription factor NusA may mediate this interaction, since it contacts both S2 and the RNAP β’ subunit in E. coli (Wang et al., 2020) and M. pneumoniae (O’Reilly et al., 2020). Thus, given our demonstration that transcription is necessary for dimer resolution (Fig. 3A), a subject for future research is investigating how direct interaction with RNAP affects ribosome dimer resolution.

Recent work from our laboratory demonstrates that the absence of HPF results in the loss of essential proteins S2 and S3 from the ribosome during incubation in stationary phase (Feaga et al., 2020). The HPF-dependent protection is due to dimerization mediated by the C-terminal domain as mutant forms of HPF that still bind the ribosome via their N-terminal domain do not prevent the loss of S2/S3 (Feaga et al., 2020). Based on experiments presented here, we propose that the function of the N-terminal domain is to act as a sensor for mRNA. Thus, resolution of ribosome dimers is coupled to the presence of mRNA, the ribosome substrate (Fig. 5B), and, in the absence of mRNA, HPF protects the ribosome from degradation. Altogether, these results suggest that Bacillus subtilis HPF is responsible for ribosome storage during conditions of nutrient limitation where mRNA synthesis is attenuated and that this mechanism can be quickly reversed in the presence of growth promoting conditions as signaled by active transcription.

Materials and Methods

Strains and media.

Strains were derived from B. subtilis 168 trpC2. To construct JDB4228 (Δhpf amyE::Phyperspank-hpf) for exogenous expression of HPF, genomic DNA was amplified with primers HF152 (ATATAAGCTTAGGGAGGCGTTCTTTGATGAAC) and HF177 (CCGGGCTAGCTCATTATT CAGTCGGTTCAATTAAGCCAT) in order to amplify HPF and its native ribosome binding site. The resulting PCR product was cut with NheI and HindIII and cloned into the same sites of pDR111. pDR111-HPF was linearized and transformed into the Δhpf background and double cross-overs were selected on plates containing spectinomycin. Expression of inducible HPF was confirmed by western blot. Cells were grown in LB or S7 minimal media containing glycerol as a carbon source for radiolabeling experiments. For experiments with antibiotics, rifampicin was used at 5 μg/mL (10X MIC) and fusidic acid was used at 3.8 μg/mL (10X MIC).

Assay for translation by 35S-methionine incorporation.

To assay wild-type or Δhpf cells in stationary phase, cells were grown in S7 minimal media to OD600 ~7.0. To assay the effect of endogenous HPF induction cells were grown in S7 minimal media containing glycerol as the carbon source to OD600 = 0.8 and induced with 1 mM IPTG for 20 min. Next, 1 mL of cells was transferred to a new tube and 4 μL of 35S-methionine was added. Cells were incubated at 37˚C and aliquots removed after 10, 20, and 30 min, quenched with cold methionine, and placed on ice. Cells were lysed with 50 mM EDTA+ 1mg/mL lysozyme. Protein was resolved on by SDS-PAGE and viewed by autoradiogram.

Detection of protein synthesis in vivo using click chemistry.

As described (Atwal et al., 2020), 300 μL of cells were transferred to a 5 mL glass tube and 0.25 μL of 20 mM Click-IT OPP reagent (Thermofisher) was added. Cells were placed on a roller drum at 37˚C for 10 min to allow OPP incorporation, after which the reaction was quenched and cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Preparation of cells for microscopy proceeded with minor deviations from the manufacturer’s instructions as described (Diez et al., 2020). For analysis of WT vs. Δhpf cells, cells were grown to transition phase (OD600~2.5) and stationary phase (OD600~6.0) and labeled with the Click-IT reagent. Three biological replicates were performed on three separate days (Fig S1). A representative experiment is shown in both Figure 1 and Figure S1. For the HPF induction experiment, two biological replicates were performed on separate days, and a representative experiment is shown in Figure 4.

Microscopy and image analysis

Cells were spotted on agar pads containing 1% agarose in PBS and imaged with a Nikon 90i microscope using 100x phase contrast. Exposure times were 30 msec for phase contrast, and 20 msec for mCherry. Fluorescence intensity of ~500 single cells per experiment was determined using ImageJ and plotted with Prism.

Sucrose gradient density centrifugation

Harvested cells were lysed using a Fast Prep machine in ribosome gradient buffer (20 mM Tris-acetate [pH4˚C 7.4], 60 mM ammonium chloride, 7.5 mM magnesium acetate, 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 0.5 mM EDTA). Lysate was cleared of debris by centrifugation at 4˚C at 20,000 rcf for 20 min. Ribosomes were purified by sucrose cushion (37.7% sucrose in ribosome gradient buffer). A260 for lysates or purified ribosomes was determined by Nanodrop, and 100 μL of normalized lysate or ribosomes (as indicated in figure legends) was loaded on a 10% to 40% sucrose gradient in ribosome gradient buffer. Gradients were run for 3 hours at 30,000 rpm in a Beckman SW41 rotor. Samples were collected with a BioComp gradient station and a BioComp TRiAX flow cell monitoring continuous absorbance at 260 nm.

In vitro translation

Ribosomes were purified from exponential (OD600 = 0.9) and stationary phase (OD600 ~6) cultures as described (Feaga et al., 2020). Ribosome concentrations were quantified by measuring A260 of dissociated subunits and further confirmed by visualizing rRNA by agarose gel electrophoresis. Ribosomes were added to the ribosome-free PURExpress system (New England Biolabs) (Tuckey et al., 2014) to a final concentration of 100 nM. 125 ng of DNA template encoding M2-tagged DHFR (MW = ~20kDa) was added and the reaction incubated at 37˚C. The reaction was stopped after 10, 20 and 30 min by addition of SDS-PAGE sample buffer. Synthesis of the resulting M2-tagged DHFR was assayed by western blot using a commercial M2-antibody.

Western Blot

HPF expression was monitored by western blot using an aliquot of culture harvested after 20 min in the presence or absence of IPTG, or from wild-type cells grown to stationary phase (OD600 ~6). Cultures were normalized by OD, pelleted, and resuspended in SDS-PAGE buffer. Lysate was resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with anti-HPF antibody (Feaga et al., 2020) followed by HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit secondary (Sigma). Samples for western blot of in vitro translation reactions were resolved by SDS-PAGE and probed with HRP-conjugated anti-M2 antibody (1:20,000; Sigma).

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Bacterial Strains and Plasmids

| Strain | Relevant genotype | Description | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| JDB1772 | trpC2 | B. subtilis parent | (Gaidenko et al., 2002) |

| JDB4221 | trpC2 ∆hpf::tet | hpf deletion | (Feaga et al., 2020) |

| JDB4228 | trpC2∆hpf::tet Phyperspank-hpf | Ectopic expression of HPF | This study |

| JDB4420 | trpC2 rpoB500 | Rifampicin resistant | (Sonenshein et al., 1974) |

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of our lab for helpful discussions and comments on the manuscript. We thank Luke Berchowitz for generously sharing his gradient analyzer. HF was supported by NIH F32GM122266. JD was supported by R35GM141953, R21AI135427, and is a Burroughs-Welcome Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease.

References

- Aiso T, Yoshida H, Wada A, and Ohki R (2005) Modulation of mRNA stability participates in stationary-phase-specific expression of ribosome modulation factor. J Bacteriol 187: 1951–1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akanuma G, Kazo Y, Tagami K, Hiraoka H, Yano K, Suzuki S, Hanai R, Nanamiya H, Kato-Yamada Y, and Kawamura F (2016) Ribosome dimerization is essential for the efficient regrowth of Bacillus subtilis. Microbiology 162: 448–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Williamson KS, Schaefer R, Pratt S, Chang CB, and Franklin MJ (2017) Resuscitation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa from dormancy requires hibernation promoting factor (PA4463) for ribosome preservation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114: 3204–3209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BW, Schumacher MA, Yang J, Turdiev A, Turdiev H, He Q, Lee VT, Brennan RG, and Wang JD (2020) The nucleotide messenger (p)ppGpp is a co-repressor of the purine synthesis transcription regulator PurR in Firmicutes. bioRxiv: 2020.2012.2002.409011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atwal S, Giengkam S, Jaiyen Y, Feaga HA, Dworkin J, and Salje J (2020) Clickable methionine as a universal probe for labelling intracellular bacteria. J Microbiol Methods 169: 105812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, Shields KE, and Yap MF (2020) The hibernating 100S complex is a target of ribosome-recycling factor and elongation factor G in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem 295: 6053–6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, and Yap MN (2016) Ribosome hibernation factor promotes Staphylococcal survival and differentially represses translation. Nucleic Acids Res 44: 4881–4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu A, and Yap MN (2017) Disassembly of the Staphylococcus aureus hibernating 100S ribosome by an evolutionarily conserved GTPase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114: E8165–E8173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckert B, Abdelshahid M, Schafer H, Steinchen W, Arenz S, Berninghausen O, Beckmann R, Bange G, Turgay K, and Wilson DN (2017) Structure of the Bacillus subtilis hibernating 100S ribosome reveals the basis for 70S dimerization. EMBO J 36: 2061–2072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beljantseva J, Kudrin P, Andresen L, Shingler V, Atkinson GC, Tenson T, and Hauryliuk V (2017) Negative allosteric regulation of Enterococcus faecalis small alarmone synthetase RelQ by single-stranded RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 114: 3726–3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergkessel M, Basta DW, and Newman DK (2016) The physiology of growth arrest: uniting molecular and environmental microbiology. Nat Rev Microbiol 14: 549–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhardt J, Weibezahn J, Scharf C, and Hecker M (2003) Bacillus subtilis during feast and famine: visualization of the overall regulation of protein synthesis during glucose starvation by proteome analysis. Genome Res 13: 224–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caban K, Pavlov M, Ehrenberg M, and Gonzalez RL Jr. (2017) A conformational switch in initiation factor 2 controls the fidelity of translation initiation in bacteria. Nat Commun 8: 1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, and Fredrick K (2020) RNA Polymerase’s Relationship with the Ribosome: Not So Physical, Most of the Time. Journal of molecular biology 432: 3981–3986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Zhu M, Warren M, Balakrishnan R, Patsalo V, Okano H, Williamson JR, Fredrick K, Wang YP, and Hwa T (2016) Reduction of translating ribosomes enables Escherichia coli to maintain elongation rates during slow growth. Nat Microbiol 2: 16231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demo G, Rasouly A, Vasilyev N, Svetlov V, Loveland AB, Diaz-Avalos R, Grigorieff N, Nudler E, and Korostelev AA (2017) Structure of RNA polymerase bound to ribosomal 30S subunit. Elife 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez S, Ryu J, Caban K, Gonzalez RL Jr., and Dworkin J (2020) The alarmones (p)ppGpp directly regulate translation initiation during entry into quiescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117: 15565–15572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drzewiecki K, Eymann C, Mittenhuber G, and Hecker M (1998) The yvyD gene of Bacillus subtilis is under dual control of sigmaB and sigmaH. J Bacteriol 180: 6674–6680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazzino L, Tilly K, Dulebohn DP, and Rosa PA (2015) Long-term survival of Borrelia burgdorferi lacking the hibernation promotion factor homolog in the unfed tick vector. Infect Immun 83: 4800–4810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feaga HA, Kopylov M, Kim JK, Jovanovic M, and Dworkin J (2020) Ribosome Dimerization Protects the Small Subunit. J Bacteriol 202: e00009–00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franken LE, Oostergetel GT, Pijning T, Puri P, Arkhipova V, Boekema EJ, Poolman B, and Guskov A (2017) A general mechanism of ribosome dimerization revealed by single-particle cryo-electron microscopy. Nat Commun 8: 722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaca AO, Kudrin P, Colomer-Winter C, Beljantseva J, Liu K, Anderson B, Wang JD, Rejman D, Potrykus K, Cashel M, Hauryliuk V, and Lemos JA (2015) From (p)ppGpp to (pp)pGpp: Characterization of Regulatory Effects of pGpp Synthesized by the Small Alarmone Synthetase of Enterococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol 197: 2908–2919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidenko TA, Kim TJ, and Price CW (2002) The PrpC serine-threonine phosphatase and PrkC kinase have opposing physiological roles in stationary-phase Bacillus subtilis cells. J Bacteriol 184: 6109–6114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourse RL, Chen AY, Gopalkrishnan S, Sanchez-Vazquez P, Myers A, and Ross W (2018) Transcriptional Responses to ppGpp and DksA. Annu Rev Microbiol 72: 163–184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green R, and Noller HF (1997) Ribosomes and translation. Annual review of biochemistry 66: 679–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gualerzi CO, and Pon CL (2015) Initiation of mRNA translation in bacteria: structural and dynamic aspects. Cell Mol Life Sci 72: 4341–4367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irving SE, and Corrigan RM (2018) Triggering the stringent response: signals responsible for activating (p)ppGpp synthesis in bacteria. Microbiology 164: 268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson GE, Lalanne JB, Peters ML, and Li GW (2020) Functionally uncoupled transcription-translation in Bacillus subtilis. Nature 585: 124–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamitani W, Narayanan K, Huang C, Lokugamage K, Ikegami T, Ito N, Kubo H, and Makino S (2006) Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus nsp1 protein suppresses host gene expression by promoting host mRNA degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 12885–12890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato T, Yoshida H, Miyata T, Maki Y, Wada A, and Namba K (2010) Structure of the 100S ribosome in the hibernation stage revealed by electron cryomicroscopy. Structure 18: 719–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline BC, McKay SL, Tang WW, and Portnoy DA (2015) The Listeria monocytogenes hibernation-promoting factor is required for the formation of 100S ribosomes, optimal fitness, and pathogenesis. J Bacteriol 197: 581–591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler R, Mooney RA, Mills DJ, Landick R, and Cramer P (2017) Architecture of a transcribing-translating expressome. Science 356: 194–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasny L, and Gourse RL (2004) An alternative strategy for bacterial ribosome synthesis: Bacillus subtilis rRNA transcription regulation. EMBO J 23: 4473–4483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapointe CP, Grosely R, Johnson AG, Wang J, Fernández IS, and Puglisi JD (2020) Dynamic competition between SARS-CoV-2 NSP1 and mRNA on the human ribosome inhibits translation initiation. bioRxiv: 2020.2008.2020.259770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennon JT, and Jones SE (2011) Microbial seed banks: the ecological and evolutionary implications of dormancy. Nat Rev Microbiol 9: 119–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li SH, Li Z, Park JO, King CG, Rabinowitz JD, Wingreen NS, and Gitai Z (2018) Escherichia coli translation strategies differ across carbon, nitrogen and phosphorus limitation conditions. Nat Microbiol 3: 939–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Xu Y, Stoleru D, and Salic A (2012) Imaging protein synthesis in cells and tissues with an alkyne analog of puromycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109: 413–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez JM (1982) GTP pool expansion is necessary for the growth rate increase occurring in Bacillus subtilis after amino acids shift-up. Arch Microbiol 131: 247–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzov D, Bashan A, Yap MF, and Yonath A (2019) Stress response as implemented by hibernating ribosomes: a structural overview. FEBS J 286: 3558–3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay SL, and Portnoy DA (2015) Ribosome hibernation facilitates tolerance of stationary-phase bacteria to aminoglycosides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59: 6992–6999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milon P, Tischenko E, Tomsic J, Caserta E, Folkers G, La Teana A, Rodnina MV, Pon CL, Boelens R, and Gualerzi CO (2006) The nucleotide-binding site of bacterial translation initiation factor 2 (IF2) as a metabolic sensor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 13962–13967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanamiya H, Kasai K, Nozawa A, Yun CS, Narisawa T, Murakami K, Natori Y, Kawamura F, and Tozawa Y (2008) Identification and functional analysis of novel (p)ppGpp synthetase genes in Bacillus subtilis. Molecular microbiology 67: 291–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly FJ, Xue L, Graziadei A, Sinn L, Lenz S, Tegunov D, Blotz C, Singh N, Hagen WJH, Cramer P, Stulke J, Mahamid J, and Rappsilber J (2020) In-cell architecture of an actively transcribing-translating expressome. Science 369: 554–557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz JO, Brandt F, Matias VR, Sennels L, Rappsilber J, Scheres SH, Eibauer M, Hartl FU, and Baumeister W (2010) Structure of hibernating ribosomes studied by cryoelectron tomography in vitro and in situ. J Cell Biol 190: 613–621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Planson AG, Sauveplane V, Dervyn E, and Jules M (2020) Bacterial growth physiology and RNA metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta Gene Regul Mech 1863: 194502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polikanov YS, Blaha GM, and Steitz TA (2012) How hibernation factors RMF, HPF, and YfiA turn off protein synthesis. Science 336: 915–918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prossliner T, Skovbo Winther K, Sorensen MA, and Gerdes K (2018) Ribosome Hibernation. Annu Rev Genet 52: 321–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puri P, Eckhardt TH, Franken LE, Fusetti F, Stuart MC, Boekema EJ, Kuipers OP, Kok J, and Poolman B (2014) Lactococcus lactis YfiA is necessary and sufficient for ribosome dimerization. Molecular microbiology 91: 394–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remigi P, Ferguson GC, McConnell E, De Monte S, Rogers DW, and Rainey PB (2019) Ribosome Provisioning Activates a Bistable Switch Coupled to Fast Exit from Stationary Phase. Mol Biol Evol 36: 1056–1070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rittershaus ES, Baek SH, and Sassetti CM (2013) The normalcy of dormancy: common themes in microbial quiescence. Cell Host Microbe 13: 643–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell JB, and Cook GM (1995) Energetics of bacterial growth: balance of anabolic and catabolic reactions. Microbiological reviews 59: 48–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonenshein AL, Cami B, Brevet J, and Cote R (1974) Isolation and characterization of rifampin-resistant and streptolydigin-resistant mutants of Bacillus subtilis with altered sporulation properties. J Bacteriol 120: 253–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinchen W, Schuhmacher JS, Altegoer F, Fage CD, Srinivasan V, Linne U, Marahiel MA, and Bange G (2015) Catalytic mechanism and allosteric regulation of an oligomeric (p)ppGpp synthetase by an alarmone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112: 13348–13353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami K, Nanamiya H, Kazo Y, Maehashi M, Suzuki S, Namba E, Hoshiya M, Hanai R, Tozawa Y, Morimoto T, Ogasawara N, Kageyama Y, Ara K, Ozaki K, Yoshida M, Kuroiwa H, Kuroiwa T, Ohashi Y, and Kawamura F (2012) Expression of a small (p)ppGpp synthetase, YwaC, in the (p)ppGpp(0) mutant of Bacillus subtilis triggers YvyD-dependent dimerization of ribosome. MicrobiologyOpen 1: 115–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tissieres A, and Watson JD (1958) Ribonucleoprotein particles from Escherichia coli. Nature 182: 778–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trauner A, Lougheed KE, Bennett MH, Hingley-Wilson SM, and Williams HD (2012) The dormancy regulator DosR controls ribosome stability in hypoxic mycobacteria. J Biol Chem 287: 24053–24063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckey C, Asahara H, Zhou Y, and Chong S (2014) Protein synthesis using a reconstituted cell-free system. Curr Protoc Mol Biol 108: 16 31 11–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueta M, Wada C, and Wada A (2010) Formation of 100S ribosomes in Staphylococcus aureus by the hibernation promoting factor homolog SaHPF. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms 15: 43–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Sanjurjo A, Schuwirth BS, Hau CW, and Cate JH (2004) Structural basis for the control of translation initiation during stress. Nat Struct Mol Biol 11: 1054–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinogradova DS, Zegarra V, Maksimova E, Nakamoto JA, Kasatsky P, Paleskava A, Konevega AL, and Milon P (2020) How the initiating ribosome copes with ppGpp to translate mRNAs. PLoS Biol 18: e3000593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voorhees RM, and Ramakrishnan V (2013) Structural basis of the translational elongation cycle. Annual review of biochemistry 82: 203–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada A, Igarashi K, Yoshimura S, Aimoto S, and Ishihama A (1995) Ribosome modulation factor: stationary growth phase-specific inhibitor of ribosome functions from Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 214: 410–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada A, Mikkola R, Kurland CG, and Ishihama A (2000) Growth phase-coupled changes of the ribosome profile in natural isolates and laboratory strains of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol 182: 2893–2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada A, Yamazaki Y, Fujita N, and Ishihama A (1990) Structure and probable genetic location of a “ribosome modulation factor” associated with 100S ribosomes in stationary-phase Escherichia coli cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 87: 2657–2661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Molodtsov V, Firlar E, Kaelber JT, Blaha G, Su M, and Ebright RH (2020) Structural basis of transcription-translation coupling. Science 369: 1359–1365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster MW, Takacs M, Zhu C, Vidmar V, Eduljee A, Abdelkareem M, and Weixlbaumer A (2020) Structural basis of transcription-translation coupling and collision in bacteria. Science 369: 1355–1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wishnia A, Boussert A, Graffe M, Dessen PH, and Grunberg-Manago M (1975) Kinetics of the reversible association of ribosomal subunits: stopped-flow studies of the rate law and of the effect of Mg2+. Journal of molecular biology 93: 499–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Anderson BW, Turdiev A, Turdiev H, Stevenson DM, Amador-Noguez D, Lee VT, and Wang JD (2020) The nucleotide pGpp acts as a third alarmone in Bacillus, with functions distinct from those of (p) ppGpp. Nat Commun 11: 5388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D, Yan K, Zhang Y, Liu G, Cao X, Song G, Xie Q, Gao N, and Qin Y (2015) New insights into the enzymatic role of EF-G in ribosome recycling. Nucleic Acids Res 43: 10525–10533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.