Abstract

Background

Diagnostic delay of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) exceeds 1 year, contributing to higher mortality. Health economic consequences of late CTEPH diagnosis are unknown. We aimed to develop a model for quantifying the impact of diagnosing CTEPH earlier on survival, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and healthcare costs.

Material and methods

A Markov model was developed to estimate lifelong outcomes, depending on the degree of delay. Data on survival and quality of life were obtained from published literature. Hospital costs were assessed from patient records (n=498) at the Amsterdam UMC – VUmc, which is a Dutch CTEPH referral center. Medication costs were based on a mix of standard medication regimens.

Results

For 63-year-old CTEPH patients with a 14-month diagnostic delay of CTEPH (median age and delay of patients in the European CTEPH Registry), lifelong healthcare costs were estimated at EUR 117 100 for a mix of treatment options. In a hypothetical scenario of maximal reduction of current delay, improved survival was estimated at a gain of 3.01 life-years and 2.04 QALYs. The associated cost increase was EUR 44 654, of which 87% was due to prolonged medication use. This accounts for an incremental cost–utility ratio of EUR 21 900/QALY.

Conclusion

Our constructed model based on the Dutch healthcare setting demonstrates a substantial health gain when CTEPH is diagnosed earlier. According to Dutch health economic standards, additional costs remain below the deemed acceptable limit of EUR 50 000/QALY for the particular disease burden. This model can be used for evaluating cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies aimed at reducing the diagnostic delay.

Short abstract

This constructed model based on the Dutch healthcare setting can be used for evaluating cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies aimed at reducing the diagnostic delay of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension https://bit.ly/35yXPM3

Introduction

Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) is a debilitating and potentially life-threating condition which is mostly established as a consequence of acute pulmonary embolism [1–4]. The steady progression of symptoms, including exertional dyspnoea, negatively impacts functional status of CTEPH patients as well as the daily lives of their relatives [5, 6]. Appropriate treatment modalities comprise pulmonary endarterectomy, balloon pulmonary angiography and pulmonary hypertension (PH)-targeted therapy.

It has been demonstrated that CTEPH is often diagnosed after a considerable diagnostic delay that contributes to higher pulmonary artery pressures at diagnosis and impaired survival [7–9]. Nevertheless, strategies for earlier diagnosis of CTEPH are usually not part of routine care for patients diagnosed with pulmonary embolism, although persistent symptoms merit follow-up according to existing guidelines. Recently, the 2019 European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) Guidelines on pulmonary embolism have proposed an echocardiography-based algorithm in patients with persistent dyspnoea or predisposing conditions for CTEPH 3–6 months after pulmonary embolism [10]. Alternatively, the InShape II algorithm aimed at early exclusion of CTEPH following an acute pulmonary embolism while limiting the number of required echocardiograms and has been evaluated in a prospective management study [11–14]. The diagnostic yield of strategies for early CTEPH diagnosis remains unclear as prospective management studies are currently lacking [15]. Moreover, the economic consequences of clinical algorithms for early CTEPH diagnosis after acute pulmonary embolism are unknown, even though such knowledge is urgently needed to guide policy makers to decide on optimal and cost-effective follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism.

In this study, a model for evaluation of cost-effectiveness depending on the degree of diagnostic delay of CTEPH was constructed and presented allowing evaluation of lifelong outcomes in CTEPH patients. The use of this model is illustrated by comparing two scenarios: the current diagnostic delay as reported in the International CTEPH registry [7, 16] and a hypothetical scenario of no delay.

Methods

Cost-effectiveness model

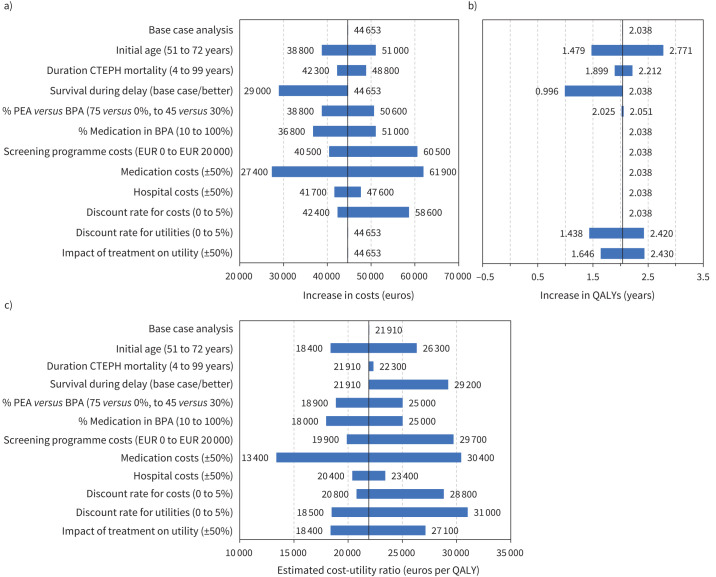

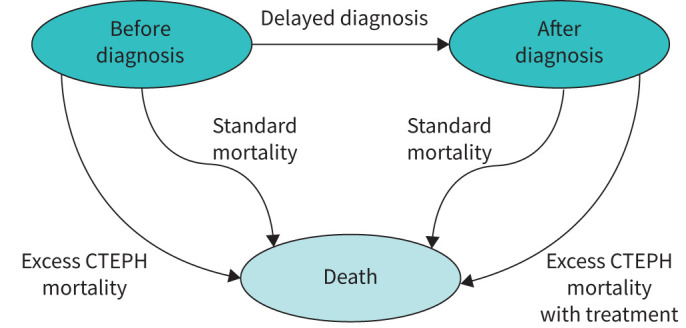

A Markov model was developed to predict lifelong outcomes of CTEPH patients, depending on the (hypothetical) degree of diagnostic delay for a CTEPH diagnosis (figure 1). Four types of treatment groups were taken into account, i.e. pulmonary endarterectomy (PEA), balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA), pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) targeted therapy and a no-treatment group. For each separate treatment group, life expectancy, quality of life and healthcare costs were estimated, distinguishing the pre- and post-treatment situation if appropriate, as described in more detail below. The Markov model was built up from weekly cycles with a 100-year time horizon, thus evaluating lifelong outcome for a predetermined delay range of 0 to 3.0 years until diagnosis. Consistent with Dutch guidelines for economic evaluations in healthcare, long-term outcomes were given less weight by discounting costs at 4.0% and quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) at 1.5% [17]. Subsequently, a cost–utility analysis was performed in which the incremental cost–utility ratio (ICUR) was calculated as follows:

|

which relates the change in costs to the change in outcome in terms of QALYs.

FIGURE 1.

States and transitions in the Markov model. The state “After diagnosis” is also split up by type of treatment (pulmonary endarterectomy, balloon pulmonary angioplasty, pulmonary arterial hypertension-targeted and no treatment). Utilities and costs are modelled depending on health state, treatment and time since diagnosis. CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

To reflect the current care situation, the base-case model assesses a “typical CTEPH patient” who is male in 50% of cases, has a fixed age at diagnosis of 63 years and a fixed diagnostic delay of 1.2 years in accordance with the International Prospective CTEPH Registry comprising 27 European centres [7]. In this base case grounded on a Dutch healthcare perspective, we have assumed a 60% proportion of cases undergoing PEA, whereas performing BPA was set at 15% [7, 18, 19]. The PAH-targeted therapy group comprised 15% of total, and the remaining 10% received no treatment [7, 18].

Data on life expectancy

All-cause mortality rates after a CTEPH diagnosis were derived from published literature. Data for the PEA, PAH-targeted therapy and no-treatment groups were based on the International Prospective CTEPH Registry comprising patients diagnosed with CTEPH between 2007 and 2009, i.e. before the BPA era [7, 13, 16]. Survival data for patients treated with BPA were derived from the French Pulmonary Hypertension Network Registry, who were diagnosed between 2013 and 2016 [20]. Given the absence of data on life expectancy in the period before CTEPH patients have been diagnosed correctly (“survival during the diagnostic delay”), survival before diagnosis for all treatment groups was assumed to coincide with survival of the untreated patient group [7]. Excess CTEPH mortality was modelled by subtracting standard Dutch mortality from the mortality reported in these studies, then fitting a two-group mixed-exponential model and extrapolating that model for 10 years [21]. In addition, non-CTEPH mortality was modelled by standard Dutch life-tables obtained from the “Central Agency for Statistics” (www.cbs.nl, accessed at February 1, 2021) [22].

Data on health-related quality of life

Utility values based on the EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D), and the Short Form Health (SF-36) Survey retrieved from published literature were used in the model to determine quality-adjusted life expectancy (table 1). Pre-treatment utility of patients in the PEA and PAH-targeted therapy groups were based on the value of CTEPH patients before undergoing a PEA approximating an equivalent baseline situation [23]. For the BPA group, comparable pre-treatment utility values were available [24]. Post-treatment values were incorporated in the model for each particular group to best match potential changes in quality of life [5, 23–25]. We assumed a stable utility for the no-treatment group equal to the pre-treatment value of the PEA group. Utility values derived from the SF-36 questionnaire were converted to EQ-5D values for all treatment groups following the method reported by Rowen et al. [26].

TABLE 1.

EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D) utility values for each health state in the Markov model

| Utilities | PEA group | BPA group | PAH-targeted therapy group | No-treatment group |

| Pre-treatment | 0.504 [23]# | 0.504 [23]# | 0.504 [23]# | 0.504 [23]# |

| Post-treatment | 0.743 [23, 25]# | 0.705 [25]# | 0.73 [5] | 0.504¶ |

PES: pulmonary endarterectemy; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension. #: after transforming the known utility values derived from the SF-36 questionnaire to estimated EuroQol five dimensions (EQ-5D) values following the method reported by Rowen et al. [25]. ¶: identical to pre-treatment utility in PEA group.

Estimation of hospital, intervention and medication costs

Focusing on the Dutch healthcare setting, healthcare use was retrospectively assessed for all CTEPH patients diagnosed by right heart catheterisation (n=498) between January 2012 and January 2019 at the VU Medical Center, which is a Dutch referral center for CTEPH. CTEPH-related hospital and intervention costs were assessed from a third-party payer perspective, using prices reported by the “Dutch Healthcare Authority” (www.opendisdata.nl, accessed at February 1, 2021) [27]. These prices include costs of hospital and medical specialist care and are established by agreements between health insurers and healthcare providers. Medication costs of PAH-targeted therapy were derived from “Zorginstituut Nederland” (www.medicijnkosten.nl, accessed at February 1, 2021) averaging a mix of standard medication regimens (supplementary appendix A) [28]. Costs in the PEA group comprised those of one-off surgical intervention and outpatient care. In addition, 25% of patients were assumed to benefit from lifelong PAH-targeted therapy because of residual PH after surgery (modelled from 1 year after diagnosis). Residual PH has been described to occur in 5–35% of patients 3 months after their PEA [29–34]. Although the most recent study has observed that residual PH prompted subsequent PAH-targeted therapy in only a quarter, we have conservatively estimated that all patients with residual PH received a combined therapeutic approach [30].

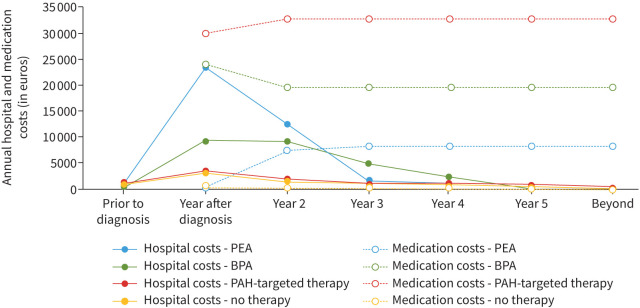

Expenses in the BPA group consisted of costs for endovascular interventions, outpatient care, bridging therapy (modelled from 0.5 year after diagnosis) and in 60% lifelong PAH-targeted therapy [20]. In the patient group treated with PAH-targeted therapy only, lifelong PAH-targeted therapy and outpatient care were taken into account. Double therapy (riociguat and an endothelin receptor blocker) was considered relevant in 8% of patients based on available literature, healthcare use in the VU Medical Center and expert opinion [35, 36]. For patients in the no-treatment group, only outpatient care was included. Observed hospital and medication costs over time, weighted for the four treatment groups, are plotted in figure 2, and all seem to stabilise after 3 to 5 years after diagnosis. Costs are reported in euros, at Dutch price level 2020 (where EUR 1≈USD 1.27 according to purchasing power parity).

FIGURE 2.

Average healthcare expenses per treatment group in years before and after chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) diagnosis for the base case analysis, distinguishing hospital and medication costs. PEA: pulmonary endarterectemy; BPA: balloon pulmonary angioplasty; PAH: pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Concerning early surveillance, we assumed that 33 echocardiograms are required per CTEPH case given the CTEPH incidence of ∼3%. Therefore, screening programme costs were estimated to be EUR 4125 per CTEPH case, based on a maximum price of EUR 125 per echocardiography.

Sensitivity analyses

A range of univariate sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the model to variations of chosen parameter values. Age at diagnosis was varied over the reported age range derived from the International Prospective CTEPH Registry (51 to 72 years, base case was 63). We analysed the impact of the duration of excess CTEPH mortality (base case 10 years) by varying it from a shorter 4-year duration to a lifetime duration (modelled as 99 years). Survival during delay is evaluated for an alternative more optimistic scenario, i.e. by ignoring the observed initial high mortality in the first 6 months of the no-treatment group (better survival versus base-case survival). Given the variations in treatment choices worldwide and the emerging role of BPA as an alternative interventional treatment for CTEPH, the proportion of PEA and BPA treatment was varied (ratio 75% versus 45% to 0% versus 30%, respectively). Moreover, the percentage of patients in the BPA group using PAH-targeted medication is now diverged from 10% to 100% [7, 20, 37, 38]. Since our model does not include diagnostic costs of pursuing an earlier diagnosis, fictitious costs of a potential strategy aimed at reducing the diagnostic delay were here taken into account ranging from the base case of EUR 0 to EUR 20 000. The change in utility due to treatment, the medication costs and the hospital costs were increased and decreased by 50%, and the discount rates for costs and QALYs were varied from 0% to 5% (base case was 4.0% and 1.5%, respectively).

Results

Survival analysis and QALYs

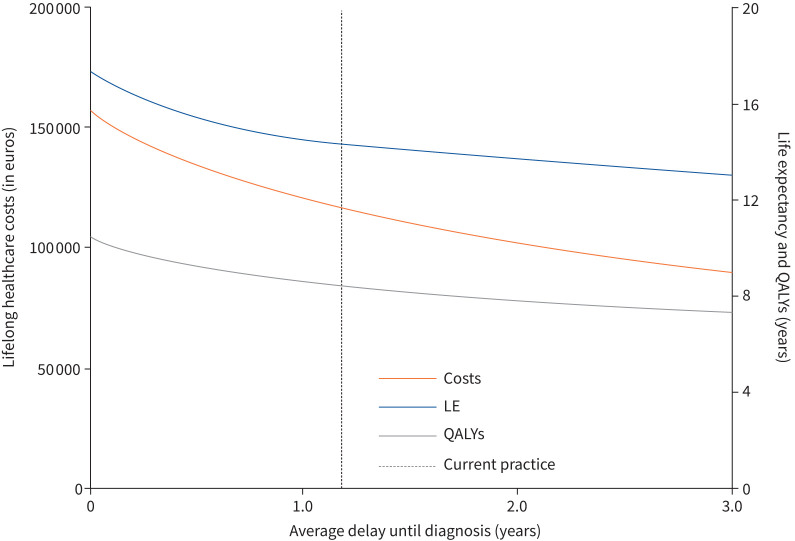

For CTEPH patients diagnosed at an age of 63 years in the base-case analysis, representing current care, our model estimates a life expectancy of 14.3 years and 8.42 QALYs (table 2). The health benefit of a hypothetically optimal situation of no delay between first symptoms and CTEPH diagnosis is represented by an estimated gain in life expectancy of 3.01 years with an associated increase of 2.04 QALYs. Of this increase in QALYs, 0.28 is due to improvement in quality of life during delay, and the remaining 1.76 because of improved life expectancy. The estimated 2-year survival after the first onset of symptoms would increase from 74% for the current delay to 88% without diagnostic delay. Figure 3 shows the estimated (quality-adjusted) life-years, depending on the duration of the delay.

TABLE 2.

Estimated average lifelong healthcare costs (euros) and effectiveness

| Base case (i.e. current care) | No delay | Difference | |

| Screening programme costs | - | 4125 | - |

| Hospital costs | 21 493 | 27 472 | 5979 |

| Medication costs (weighted per treatment group) | |||

| PEA (60%) | 40 297 | 55 094 | 14 797 |

| BPA (15%) | 27 636 | 37 619 | 9983 |

| PAH-targeted therapy (15%) | 27 679 | 37 449 | 9770 |

| No treatment (5%) | - | - | - |

| Total lifelong costs | 117 105 | 161 759 | 44 654 |

| Life expectancy years | 14.3 | 17.3 | 3.01 |

| QALYs years | 8.42 | 10.45 | 2.04 |

| Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio | 14 853 per life-year gained | ||

| Incremental cost–utility ratio | 21 910 per QALY gained | ||

PEA: pulmonary endarterectomy; BPA: balloon pulmonary angioplasty; PH: pulmonary hypertension; QALY: quality-adjusted life-year.

FIGURE 3.

Estimated life expectancy, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and lifelong healthcare costs plotted against diagnostic delay of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. LE: life expectancy.

Costs and cost-effectiveness analysis

Total lifelong healthcare costs are estimated at EUR 117 105 in the base case for a mix of treatment options (table 2). Reducing the delay from the base case 1.2 years to nil, the model predicts that these total costs would increase to EUR 161 759. This excess in costs of EUR 44 654 represents an increase in healthcare use, of which EUR 38 675 (87%) is attributable to costs of medication use. The ICUR (i.e. costs-per-QALY gained) was EUR 21 910 per QALY.

In a plausible situation of decreasing the current delay to 0.5 year, estimated life expectancy and QALYs would increase by 1.08 and 0.76 years, respectively, compared to the current situation. This profit is achieved at the expense of total additional costs with an ICUR of EUR 27 199 (figure 3).

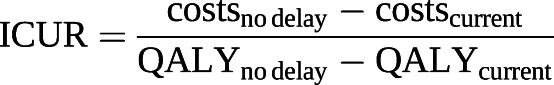

Sensitivity analyses

The sensitivity analyses show that costs are most affected by the difference in overall medication costs, rather than by hospital costs (figure 4), as medication forms the largest share (83%) of the total costs. Increasing these medication costs by 50% increases the estimated ICUR to EUR 30 400/QALY. Assuming a higher proportion of patients in the BPA group treated with medical therapy could increase the ICUR to EUR 25 000/QALY. A more equal ratio of PEA to BPA treatments affects the ICUR even more since this would lead to a greater increase in medication use. Better survival during the delay resulted in a smaller QALY difference and an ICUR of EUR 29 200/QALY. If the excess CTEPH mortality lasted a lifetime, this would only have a limited impact on both healthcare costs and QALYs. A younger age at diagnosis is beneficial for the life expectancy, lowering the ICUR to EUR 18 400/QALY. Moreover, if we model a more positive impact of treatment on utility, the ICUR would also decrease. If we increase the screening programme costs associated with a fictitious strategy to establish the reduced delay to EUR 20 000, that would increase the ICUR to EUR 29 700/QALY. Finally, if discount rates of costs and utilities had a greater influence, the estimated ICUR would increase at most to EUR 31 000/QALY.

FIGURE 4.

Tornado diagram showing the impact of maximal reduction of delay on a) costs, b) quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and c) costs-per-QALY, depending on model assumptions (compared to current delay). CTEPH: chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension; PEA: pulmonary endarterectomy; BPA: balloon pulmonary angioplasty.

Discussion

Our study presents the first Markov model for quantifying the impact of reducing the diagnostic delay of CTEPH on lifelong costs and QALYs without shaping strategies aimed at earlier CTEPH diagnosis itself. Considering the “typical CTEPH patient”, a maximal reduction of delay compared to the current diagnostic delay of 1.2 years was shown to result in 2.04 more QALYs against an ICUR of EUR 21 900 per QALY. The additional healthcare expenses primarily consisted of a substantial increase in medication rather than hospital costs: forwarding surgery does not alter the associated costs, whereas forwarding the start of medication treatment does. By performing sensitivity analyses on key parameters of the model, ICUR was demonstrated to be at most EUR 31 000 per QALY. This compares favourably to the willingness-to-pay threshold of EUR 50 000 per QALY that applies to CTEPH care according to Dutch health economic standards [39].

This cost-effectiveness analysis provides relevant information on the potential value of strategies for earlier diagnosis of CTEPH, which has been addressed in the recommendations on follow-up of patients with acute pulmonary embolism in the 2019 ESC/ERS Guidelines [10]. Although CTEPH greatly affects quality of life and is potentially curable, only few screening approaches have been studied [10, 14, 40, 41]. Of note, we deliberately have constructed the base-case model without regard to the costs of algorithms for earlier CTEPH diagnosis, so the estimated cost-effectiveness ratio applies if – hypothetically – the decrease in delay would be realised without additional costs. Diagnostic strategies to actually reduce delay may require additional costs not yet included in our base-case model, depending on the nature of the strategies and the test characteristics of the chosen clinical algorithm, i.e. both costs associated with the strategy itself and those with false positive and false negative test results. However, if signs of CTEPH are sought for as part of state-of-the-art outpatient care in the course after an acute pulmonary embolism, additional diagnostic costs may even be negligible. Based on our sensitivity analyses, we argue that a screening approach that reduces the diagnostic delay to nil is allowed to comprise up to EUR 20 000 per patient.

Our model estimates that 2-year survival improves by reducing the diagnostic delay of CTEPH, suggesting that premature deaths from undiagnosed patients can be prevented. This was shown to be associated with higher costs, which may seem contradictory. These higher costs are caused by an increase in PAH-targeted medication use. In view of the societal context this excess in costs is counterbalanced by a presumable cost reduction due to increased productivity. Although this has been illustrated by some studies among venous thromboembolism patients, we have disregarded this in our analysis, since no data specifically on labour productivity among CTEPH patients have been published [42, 43]. Of note, the impact of disease burden on caregivers has not been taken into account either and might further favour health benefits [44].

We acknowledge that our model is based on a Dutch perspective, and that patient characteristics and standard clinical practice may differ internationally. Although Western countries and Japan all recommend PEA as the first-line treatment in patients with operable CTEPH [45–47], it has been argued that BPA treatment in Japan results in better outcomes compared to Western countries [2, 48]. In fact, BPA is an emerging treatment modality worldwide which will likely influence the cost-effectiveness analysis over time towards increased costs [2]. As such, after increasing the proportion of patients treated with BPA in our sensitivity analysis to 30% while lowering the proportion of PEA treatment to 45%, we found a marginal increase in ICUR of EUR 3091. Besides, medication costs in particular have a great impact on the ICUR and may vary between regions. Even if these costs were 50% higher than in the base case analysis, the ICUR would still remain below EUR 30 400 per QALY, which is deemed highly acceptable for pursuing delay reduction in CTEPH patients. Our data need to be confirmed for healthcare systems outside of the Netherlands and will also need to be complemented, in the future, by prospective data showing the impact of early diagnosis on quality of life. Also, in future cost-effectiveness studies, data on survival, adverse events and corresponding costs from randomised controlled trials comparing different treatment strategies for CTEPH are required to elucidate the most optimal treatment strategy.

Our model has limitations, firstly because we had to make several modelling assumptions. For instance, data on quality of life and non-CTEPH-related healthcare costs were not sufficiently available in published data for all specific treatment groups. Also, our model was constructed for a “typical CTEPH patient”, relying on average parameter values. Our analysis does not provide sufficient information on the impact of earlier diagnosis in specific subgroups. Second, costs related to BPA are inherent to the number of interventional sessions, which may vary widely. A median of four sessions per patient was reported in a meta-analysis including 17 studies on BPA, but with a wide range of 1.8 to 18.6 sessions [49]. In Dutch CTEPH expert centres, a mean± sd of 4.5±13 BPA sessions per patient are carried out, which likely applies to input data of the model [50]. Also, lifelong anticoagulant therapy is an essential part of treatment in all CTEPH patients, which will be initiated earlier if CTEPH is diagnosed earlier. However, a large proportion of pulmonary embolism patients in whom CTEPH is ruled out will also have these expenses related to increased anticoagulation prescriptions, and, thus, this will likely result in only a limited increase in total costs. Third, in our analysis, gains in survival especially result from curtailing the assumed high mortality before diagnosis. Although many studies have reported mortality data on CTEPH patients, the mortality rate among CTEPH patients who are not yet diagnosed remains unknown. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that patients with the highest delays are associated with worse pulmonary artery pressures and higher mortality [9]. As such, given the lack of data we might have underestimated the positive impact of an earlier diagnosis on progression of disease, and thus the mortality during delay. In contrast, the degree of delay was shown not to affect operability, i.e. treatment choice, nor New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, which strongly relates to quality of life [9]. Fourth, the survival data were extracted from two different studies performed in different years, i.e. the International CTEPH Registry and the French Pulmonary Hypertension Network Registry, which may not be fully comparable [16, 20]. Of note, the decision to use both mortality rates without adjustment in our model is supported by several similarities between the study cohorts: age, sex and median diagnostic delay. We may even have underestimated the survival in the different treatment groups given the increased experience with PEA and BPA and its technical improvements in the years after publication of the aforementioned studies. Finally, excess CTEPH mortality was assumed to end 10 years after the diagnosis. Large studies report data of up to 4 years only; however, in our model we observed a stabilised survival curve after 10 years. This pattern is supported by a recent study including 100 operated CTEPH patients who were followed up for a median of 7.2 years and maximum of 22 years [51]. A limited impact of longer CTEPH excess mortality has been confirmed in our sensitivity analysis.

In conclusion, this cost-effectiveness analysis based on a Dutch healthcare perspective is the first major effort to start focusing on quantitative assessment of the economic burden of reducing the diagnostic delay of CTEPH versus the benefits for healthcare systems and, thus, for society as a whole. Our results indicate beneficial lifelong patient-relevant outcomes against acceptable additional costs after accomplishing an earlier CTEPH diagnosis. Our model can be used for evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of strategies for earlier CTEPH diagnosis, by taking into account the costs associated with reducing the diagnostic delay.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00719-2020.SUPPLEMENT (261.9KB, pdf)

Model 00719-2020.model (20.8MB, xlsm)

Footnotes

Provenance: Submitted article, peer reviewed.

This article has supplementary material available from openres.ersjournals.com

Data availability: The Markov model as well as the raw data used to support the findings of this study are available. We hope to publish the model itself (in an Excel sheet) along with the manuscript, allowing for easy adjustments based on local circumstances in different countries and settings Data will be available immediately following article publication, ending 36 months following publication, to investigators who provide a methodologically sound proposal, to achieve aims in the approved proposal. Proposals should be directed to f.a.klok@lumc.nl. To gain access, data requestors will need to sign a data access agreement.

Conflict of interest: G.J.A.M. Boon reports grants from the Dutch Heart Foundation and Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: W.B. van den Hout reports grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) and National Health Care Institute (Zorginstituut Nederland) outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: S. Barco has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: H.J. Bogaard has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M. Delcroix has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: M.V. Huisman reports grants from the ZonMW Dutch Healthcare Fund, grants and personal fees from Pfizer–BMS, Bayer Health Care and Daiichi-Sankyo, and grants from Leo Pharma, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: S.V. Konstantinides has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: L.J. Meijboom has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: E.J. Nossent has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: P. Symersky has nothing to disclose.

Conflict of interest: A. Vonk Noordegraaf reports grants from the Netherlands CardioVascular Research Initiative and Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, other support from Johnson & Johnson and Ferrer in the past 3 years, and nonfinancial support as a member of a scientific advisory board of Morphogen-XI, outside the submitted work.

Conflict of interest: F.A. Klok reports grants from Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi Sankyo, MSD, Actelion, the Netherlands Thrombosis Foundation and the Dutch Heart Foundation outside the submitted work.

Support statement: This work was supported by unrestricted grants from Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd. F.A. Klok and G.J.A.M. Boon were supported by the Dutch Heart Foundation (2017T064). Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

References

- 1.Delcroix M, Torbicki A, Gopalan D, et al. ERS statement on chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2020; 57: 2002828. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02828-2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim NH, Delcroix M, Jais X, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2019; 53: 1801915. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01915-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huisman MV, Barco S, Cannegieter SC, et al. Pulmonary embolism. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2018; 4: 18028. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ende-Verhaar YM, Cannegieter SC, Vonk Noordegraaf A, et al. Incidence of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism: a contemporary view of the published literature. Eur Respir J 2017; 49: 1601792. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01792-2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ivarsson B, Hesselstrand R, Radegran G, et al. Health-related quality of life, treatment adherence and psychosocial support in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Chron Respir Dis 2019; 16: 1479972318787906. doi: 10.1177/1479972318787906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mathai SC, Ghofrani HA, Mayer E, et al. Quality of life in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2016; 48: 526–537. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01626-2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pepke-Zaba J, Delcroix M, Lang I, et al. Chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH): results from an international prospective registry. Circulation 2011; 124: 1973–1981. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.015008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ende-Verhaar YM, van den Hout WB, Bogaard HJ, et al. Healthcare utilization in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism. J Thromb Haemost 2018; 16: 2168–2174. doi: 10.1111/jth.14266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klok FA, Barco S, Konstantinides SV, et al. Determinants of diagnostic delay in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: results from the European CTEPH Registry. Eur Respir J 2018; 52: 1801687. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01687-2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Konstantinides SV, Meyer G, Becattini C, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acute pulmonary embolism developed in collaboration with the European Respiratory Society (ERS). Eur Respir J 2019; 54: 1901647. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01647-2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ende-Verhaar YM, Huisman MV, Klok FA. To screen or not to screen for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism. Thromb Res 2017; 151: 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2016.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ende-Verhaar YM, Ruigrok D, Bogaard HJ, et al. Sensitivity of a simple noninvasive screening algorithm for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism. TH Open 2018; 2: e89–e95. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1636537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boon GJAM, Bogaard HJ, Klok FA. Essential aspects of the follow-up after acute pulmonary embolism: an illustrated review. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2020; 4: 958–968. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boon Gudula JAM, Ende-Verhaar Yvonne M, Bavalia Roisin, et al. Non-invasive early exclusion of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism: the InShape II study. Thorax. 2021: thoraxjnl-2020-216324. 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-216324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boon GJAM, Huisman MV, Klok FA. Why, whom, and how to screen for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension after acute pulmonary embolism. Semin Thromb Hemost 2020; in press [doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1718925]. 10.1055/s-0040-1718925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delcroix M, Lang I, Pepke-Zaba J, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: results from an international prospective registry. Circulation 2016; 133: 859–871. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zorginstituut Nederland . Richtlijn voor het uitvoeren van economische evaluaties in de gezondheidszorg. 2016. www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publicaties/publicatie/2016/02/29/richtlijn-voor-het-uitvoeren-van-economische-evaluaties-in-de-gezondheidszorg Date last accessed: 1 February 2021.

- 18.Hurdman J, Condliffe R, Elliot CA, et al. ASPIRE registry: assessing the Spectrum of Pulmonary hypertension Identified at a REferral centre. Eur Respir J 2012; 39: 945–955. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00078411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quadery SR, Swift AJ, Billings CG, et al. The impact of patient choice on survival in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 2018; 52: 1800589. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00589-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taniguchi Y, Jais X, Jevnikar M, et al. Predictors of survival in patients with not-operated chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. J Heart Lung Transplant 2019; 38: 833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2019.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Hout WB. The GAME estimate of reduced life expectancy. Med Decis Making 2004; 24: 80–88. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03261564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek. Life tables. 2012. www.cbs.nl/en-gb/our-services/methods/statistical-methods/output/output/life-tables Date last accessed: 1 February 2021.

- 23.Kamenskaya O, Klinkova A, Loginova I, et al. Determinants of health-related quality of life 1 year after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy. Ann Vasc Surg 2018; 51: 254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2018.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Darocha S, Pietura R, Pietrasik A, et al. Improvement in quality of life and hemodynamics in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension treated with balloon pulmonary angioplasty. Circ J 2017; 81: 552–557. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamenskaya O, Klinkova A, Chernyavskiy A, et al. Long-term health-related quality of life after surgery in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Qual Life Res 2020; 29: 2111–2118. doi: 10.1007/s11136-11020-02471-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rowen D, Brazier J, Roberts J. Mapping SF-36 onto the EQ-5D index: how reliable is the relationship? Health Qual Life Outcomes 2009; 7: 27. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-7-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Open data van de Nederlandse Zorgautoriteit. Dbc-zorgproducten. 2020. www.opendisdata.nl/msz/zorgproduct

- 28.Zorginstituut Nederland . March 2020. www.medicijnkosten.nl/ Date last accessed: 1 February 2021.

- 29.Auger WR. Surgical and percutaneous interventions for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Cardiol Clin 2020; 38: 257–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2020.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freed DH, Thomson BM, Berman M, et al. Survival after pulmonary thromboendarterectomy: effect of residual pulmonary hypertension. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2011; 141: 383–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.12.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jais X, D'Armini AM, Jansa P, et al. Bosentan for treatment of inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: BENEFiT (Bosentan Effects in iNopErable Forms of chronIc Thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension), a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 52: 2127–2134. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.08.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Gibbs JS, et al. Improved outcomes in medically and surgically treated chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008; 177: 1122–1127. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200712-1841OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suntharalingam J, Treacy CM, Doughty NJ, et al. Long-term use of sildenafil in inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Chest 2008; 134: 229–236. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-2681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonderman D, Skoro-Sajer N, Jakowitsch J, et al. Predictors of outcome in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 2007; 115: 2153–2158. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.661041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McLaughlin VV, Jansa P, Nielsen-Kudsk JE, et al. Riociguat in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: results from an early access study. BMC Pulm Med 2017; 17: 216. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0563-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amsallem M, Guihaire J, Arthur Ataam J, et al. Impact of the initiation of balloon pulmonary angioplasty program on referral of patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension to surgery. J Heart Lung Transplant 2018; 37: 1102–1110. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2018.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogawa A, Satoh T, Fukuda T, et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: results of a multicenter registry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2017; 10: e004029. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.117.004029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mizoguchi H, Ogawa A, Munemasa M, et al. Refined balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2012; 5: 748–755. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.971077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zorginstituut Nederland . Ziektelast in de praktijk - De theorie en praktijk van het berekenen van ziektelast bij pakketbeoordelingen. 2018. www.zorginstituutnederland.nl/publicaties/rapport/2018/05/07/ziektelast-in-de-praktijk Date last accessed: 1 February 2021.

- 40.Held M, Hesse A, Gott F, et al. A symptom-related monitoring program following pulmonary embolism for the early detection of CTEPH: a prospective observational registry study. BMC Pulm Med 2014; 14: 141. doi: 10.1186/1471-2466-14-141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coquoz N, Weilenmann D, Stolz D, et al. Multicentre observational screening survey for the detection of CTEPH following pulmonary embolism. Eur Respir J 2018; 51: 1702505. doi: 10.1183/13993003.02505-2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Page RL, 2nd, Ghushchyan V, Gifford B, et al. Hidden costs associated with venous thromboembolism: impact of lost productivity on employers and employees. J Occup Environ Med 2014; 56: 979–985. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Barco S, Woersching AL, Spyropoulos AC, et al. European Union-28: an annualised cost-of-illness model for venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost 2016; 115: 800–808. doi: 10.1160/TH15-08-0670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ivarsson B, Sjoberg T, Hesselstrand R, et al. Everyday life experiences of spouses of patients who suffer from pulmonary arterial hypertension or chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. ERJ Open Res 2019; 5: 00218-2018. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00218-2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Galie N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Heart J 2016; 69: 177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, et al. ACCF/AHA 2009 expert consensus document on pulmonary hypertension: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Expert Consensus Documents and the American Heart Association: developed in collaboration with the American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, Inc., and the Pulmonary Hypertension Association. Circulation 2009; 119: 2250-2294. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fukuda K, Date H, Doi S, et al. Guidelines for the Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension (JCS 2017/JPCPHS 2017). Circ J 2019; 83: 842–945. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-66-0158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanabe N, Kawakami T, Satoh T, et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a systematic review. Respir Investig 2018; 56: 332–341. doi: 10.1016/j.resinv.2018.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Khan MS, Amin E, Memon MM, et al. Meta-analysis of use of balloon pulmonary angioplasty in patients with inoperable chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Int J Cardiol 2019; 291: 134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2019.02.051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van Thor MCJ, Lely RJ, Braams NJ, et al. Safety and efficacy of balloon pulmonary angioplasty in chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in the Netherlands. Netherlands Heart J 2020; 28: 81–88. doi: 10.1007/s12471-019-01352-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kallonen J, Glaser N, Bredin F, et al. Life expectancy after pulmonary endarterectomy for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension: a Swedish single-center study. Pulm Circ 2020; 10: 2045894020918520. doi: 10.1177/2045894020918520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Supplementary material 00719-2020.SUPPLEMENT (261.9KB, pdf)

Model 00719-2020.model (20.8MB, xlsm)