Abstract

Objective

Italy faced one of the first large clusters of COVID-19 infections worldwide. Home confinement and social distancing could have negatively impacted sleep habits and prevalence of sleep disorders in children, which may be also linked with altered emotional processes. The present study focused on clinical aspects related to sleep, insomnia and emotions in Italian children aged 0-to-12 years during home confinement due to COVID-19 outbreak.

Method

An online survey was systematically distributed in all Italian territories by contacting regional offices of the Italian Ministry of Instruction, University and Research (MIUR) and schools with available contact. All respondents had to be parents of at least one child aged 0 to 12 years old. Information on sociodemographic variables, sleep habits, sleep health behaviors, sleep disorders and mood were collected.

Results

Parents of 2361 children (mean age: 8.1 ± 2.62 years; 1148 females; 1213 males) answered the survey. 1.2% of children was between 0 and 2 years old; 15.3% within 3 to 5 years and 83.3% within 6 and 12 years. In all group ages, late bedtime was observed (most of them after 9 p.m.). 59.4% of all children presented at least one clinical diagnostic criterion for childhood insomnia. Logistic regression model showed that presence of at least one criterion for childhood insomnia was associated to younger age, negative mood, current parental insomnia, being the only child, presence of any other sleep disorder, and sleep hygiene behaviors.

Conclusions

Data indicate an alarming increase of prevalence of insomnia related problems in Italian children during home confinement with respect to previous data. This was found to be associated with poor sleep hygiene and negative mood. Clinical programs targeting insomnia, sleep health behaviors and emotional processes should be implemented in pediatric primary care in order to prevent the development of sleep problems in a post-pandemic situation.

Keywords: sleep, children, COVID-19, insomnia, health, home confinement, sleep hygiene, emotions

Introduction

Sleep is a core health process strictly linked to several physical, psychological and behavioral developmental outcomes (Chaput et al., 2016). Specifically, during childhood, poor sleep is significantly associated with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder (Cortese, Lecendreux, Mouren, Konofal, 2006); impulsive behavior (Lam, Hiscock, Wake, 2003); social interpersonal relationship as peer acceptance, social skills, social engagement, receptive vocabulary, and understanding emotions (Vaughn et al., 2015); anxiety and depression (Alfano, Zakem, Costa, Taylor, Weems, 2009), and academic failure due to cognitive problems and inattention (Gruber et al., 2012). Etiological models highlighted the dynamic interactive role of various factors in explaining children sleep quality (Mindell & Owens, 2015). These factors include genetic and neurobiological characteristics of the child (e.g. genetic vulnerability and underlying medical or psychiatric conditions); parent-child interactive context (including emotional variables, e. g. attachment, parental sensitivity, and family habits, e. g. bedtime interactions, soothing methods for falling asleep, bedtime limit setting behaviors); parental mental health (e.g. presence of parental psychopathology or increased familiar stress); cultural and societal aspects (e.g. cross-cultural difference in social family sleep habits); family support resources (e.g. couple support; babysitter, family support). The majority of childhood sleep problems depends on behavioral dysfunctional familiar habits (Owens, 2008).

Bedtimes, sleep location, bedtime routines, daytime naps, consumption of beverages with caffeine, and use of the bed for daytime activities are all aspects associated with quality of sleep, which are dependent on family’s habits, possibilities, and beliefs. Moreover, previous findings showed that use of electronic devices in the bedroom (Mindell et al., 2009); daily schedule, early school start times, and sociocultural aspects (El‐ Sheikh & Sadeh, 2015) could significantly impact on sleep quality and characteristics.

Diagnostic criteria for childhood insomnia are defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association, 2013) and in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd ed. (ICSD-3, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2005) as subjectively significant difficulty initiating and/or maintaining sleep (≥ 30 minutes), or early morning awakening for both adults and children. Specifically for children, two further criteria are considered: resistance to go to bed and difficulty to initiate or maintain sleep without parental presence. The sleep complaint must be accompanied by distress about poor sleep and/or impairment in the family and occur despite adequate opportunity and adequate circumstances (e.g., safe, dark, quiet environment). A consensus definition of pediatric insomnia was developed and defined insomnia as “repeated difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite age-appropriate time and opportunity for sleep and results in daytime functional impairment for the child and/or family.” (Mindell & Owens, 2015). While DSM-5 and ICSD-3 do not use separate diagnostic criteria for adult and pediatric insomnia, a number of key features for childhood insomnia were considered in the consensus definition, such as symptoms may be reported by the patient or caregiver, and behavioral problems should be interpreted as a manifestation of sleepiness. These features have been incorporated into the updated versions of the DSM-5 and ICSD-3 diagnoses. Parents may present child’s insomnia problem as complaints of “bedtime problems” (bedtime refusal and bedtime stalling) or “night-waking” (children that are unable to recreate the sleep association, requiring parental assistance to return to sleep). Poor sleep and insomnia have been considered as key risk factors for psychopathology in adults (Baglioni et al., 2010; Hertenstein et al., 2019). Similarly, sleep disorders in pediatric populations are highly prevalent and are associated with behavioral and emotional issues (such as depression and anxiety symptomatology, separation distress, and inhibition) in the course of the development (Mindell, Leichman, DuMond, Sadeh, 2017; Hysing, Sivertsen, Garthus-Niegel, Eberhard-Gran, 2016). Correlational and longitudinal studies linked poor sleep or insomnia with symptoms of emotional dysregulation, depression, anxiety, aggressive behavior and low self-esteem ratings in children (Fredriksen, Rhodes, Reddy, & Way, 2004 Gregory, Van der Ende, Willis, & Verhulst, 2008).

Italy faced one of the first, largest and most serious clusters of COVID-19 infections in the world. From 9th March to 4th May 2020, all country was declared “protected area” and strict rules were applied to confine individuals in their homes with the possibility to go out only for reasons of certified necessity such as for food shopping, work needs, purchase of drugs or other health reasons. The north of Italy was particularly affected by COVID-19 pandemic with a higher percentage of infected people compared to the rest of Italy. Kindergarten and schools closed on 9th of March and remained closed until September 2020.

Already before the health emergency, Italian and cross-cultural studies pointed out an alarming prevalence of poor sleep and dysfunctional sleep habits in Italian children. Specifically, previous studies showed that both parents and pediatricians in Italy underestimate the role and the importance of sleep during developmental age (e.g. Wolf, Lozoff, Latz & Paludetto, 1996). Italian children tend to present general shorter sleep duration compared to those recommended by the National Sleep Foundation (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015), long sleep onset latency and wake after sleep onset (Cortesi, Giannotti, Sebastiani, & Vagnoni, 2004; Bacaro et al., 2019). This is particularly important because short sleep duration in children is associated with a higher risk of obesity (Wu et al., 2017), emotion dysregulation, cognition impairment and poor quality of life (Chaput et al., 2016). Furthermore, co-sleeping (sharing a sleeping surface with a family member for all or a portion of the sleep period, Goldberg and Keller 2007) after the first year of life is often used as a response to problematic sleep (10–14% of toddlers and 17% of preschoolers; Giannotti et al., 2005), and it is associated with a higher presence of sleep problems (Bruni et al., 2002; Cortesi et al., 2004; Muratori et al., 2019).

Experts in the field alarmed that sleep in children may be negatively impacted by social deprivation, home confinement, and socioeconomic uncertainty due to COVID-19 outbreak (Altena et al., 2020; Becker & Gregory, 2020). As stated in a recent editorial published in the Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry (Becker & Gregory, 2020), high-quality studies which examine the impact of COVID-19 outbreak on children’s sleep are of utmost importance and urgency. Furthermore, recent literature highlighted the urgent need to provide new strategies and to identify new factors that could help children in the adjustment to this critical situation (Becker & Gregory, 2020). New clinical approaches should be considered to identify children at risk for mental disorders in order to develop specific psychological interventions (Becker & Gregory, 2020). As stated above, sleep is an important precursor of mental disorders and early diagnosis and treatment of behavioral sleep problems in the developmental age may have a potential preventive role for the development of psychopathology.

Thus, with the outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, several factors may be associated with the raising of poor sleep hygiene behaviors and prevalence of sleep disorders, especially childhood insomnia. These factors include lack of social regulators (e.g. school, social relationships with peers, Vaughn et al., 2015), irregular bedtime and changes in pre-bed routines (Buxton et al., 2015), increased active use of the bed (Fuller et al., 2017), increased use of caffeine (Watson et al., 2017), reduced physical activity and conquered time out (Dworak et al., 2008). Poor sleep and childhood insomnia may be further linked with the presence of other sleep problems (e.g. excessive daytime sleepiness, delayed phase syndrome) and altered mood, including the increase of negative emotions and decrease of positive emotions (Mindell et al., 2017).

The present study focused on clinical aspects related to sleep in the Italian children aged 0 to 12 years during home confinement due to COVID-19 outbreak. Whenever available, data on the Italian population before the pandemic were considered to evaluate possible changes strictly associated with the lockdown. Specifically, the following aspects were observed:

Children sleep health-related habits and parental reports of child’s positive and negative emotions;

Prevalence of childhood insomnia and other sleep problems;

Association of childhood insomnia with relevant factors, e. g. sociodemographic variables (e.g. age, family composition, parental insomnia), positive and negative emotions, sleep health-related behaviors, sleep hygiene and comorbidity with other sleep problems.

Method

Procedure

Recruitment started on the 14th of April, about 1 month after the beginning of home confinement, and was completed on the 10th of May 2020, the week in which the lockdown was gradually released. The study was conducted in collaboration between the Department of Human Sciences of the University of Study Guglielmo Marconi of Rome (Italy), the Italian School of Specialization in Cognitive Psychotherapy (SPC, Rome, Italy), and the Sleep Laboratory of the Department of Clinical Psychophysiology/Sleep Medicine of the Centre for Mental Disorders of the University Medical Centre of Freiburg (Germany).

The target population included all children attending Italian schools aged between 0 to 12 years. An online survey was created on Survey Monkey platform, an anonymous database and data repository commonly used in research (e.g. Fox et al., 2003). The survey was systematically distributed in all Italian territory by sending e-mails to all regional offices of the Ministry of Instruction, University and Research (MIUR, website: https://cercalatuascuola.istruzione.it/cercalatuascuola/). Offices which agreed consequently sent the informative email with the link to the survey to the mailing lists of all schools in the Italian territory. In these e-mails, the rationale and aims of the study were explained and the link to the survey was given. Schools were invited, if interested, to forward the link to the survey to all parents of their institution.

All respondents had to be parents of at least one child aged 0 to 12 years old. If more than one child in this age range was present, parents were asked to fill in two separate surveys. The completion of the study was voluntary and anonymous and required an average compilation time of 10 minutes. If participants were interested to participate, they were asked to read accurately the information about the study and to read and fill in a written and informed consent form before starting the survey. Contacts of researchers were given in the informative page and participants could contact them for any doubt or need.

Inclusion criteria for participation in this study were:

to have an Italian residence and to stay in Italy during the quarantine period (from March 9th to May 18th, 2020)

to have good knowledge and understanding of the Italian language (since the survey was in Italian language);

to be a parent (mother or father) of at least one child aged between 0 to 12 years old.

No compensation for participating in the study was provided. All procedures were performed in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments, and the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Psychological Area of the University of Study Survey Guglielmo Marconi of Rome (Italy).

Parents were asked to answer to different type of questions: a first part including questions about general information on the family organization and the impact of pandemic on social relationships and school activities; a second part including questions about information on child’ sleep habits, sleep quality, sleep patterns and emotions. Specifically the following information were requested:

General information: respondent (mother or father); nationality; age; sex; BMI (weight and height); region1 (north; center; south; islands); number of family members (2; 3; 4; ≥5); family composition (single parents; parents with one child; parents with 2 or more children; parents with children and other family members); current parental insomnia (whether the mother or the father currently present or not difficulties falling asleep or waking during the night or early morning awakenings for 3 or more nights a week); past parental insomnia (whether the mother or the father suffered or not of insomnia before home confinement); worry about the pandemic situation (not at all; a little; quite a bit; much; very much); tested positive to the virus (yes; no); school attended (nursery or no school; kindergarten; primary school; first level secondary school; other); school procedures during COVID-19 (video lessons and online homework; only video lessons; only online homework; no online school; other); extra school activities attended (yes; no); extra school activities during COVID-19 (yes; no); physical activity (yes; no); child current medical disorders (yes; no); child use of medical drugs (yes; no).

Information on child’s sleep habits: bedtime (between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m.; between 8 p.m. and 9 p.m.; after 10 p.m.); wake up time (before 6 a.m.; 6 a.m. – 7 a.m.; 7 a.m. – 8 a.m.; 8 a.m. – 9 a.m.; 9 a.m. – 10a.m.; 10 a.m. – 11 a.m.; after 11 a.m.); total sleep time ( < 7h; 7-9 h; 9-11 h; > 11 h); sleep onset latency (< 5 min; 10-20 min; 30-40 min; > 40 min); number of awakenings (0; 1; 2; 3; ≥4); difficulties to wake up (yes; no); sleep place (alone; in the same room with siblings; in the same room of parents; other); falling asleep habit (alone; hold in arms; cradled; with the hand; with the tv; other); number of naps (0; 1; ≥ 2); use of sleep drugs (yes; no); and type of sleep drugs (melatonin; other).

Information on sleep hygiene behaviors: regular sleep times (yes; no); pre-bed routines (never; less than once per week; once or twice per week; all nights); active use of bed during the day (never; less than once per week; once or twice per week; all nights); active use of bed during the evening(never; less than once per week; once or twice per week; all nights); caffeine use (e.g. Coke; tea, chocolate: never; less than once per week; once or twice per week; all nights); active playing in the evening (never; less than once per week; once or twice per week; all nights).

Information on sleep problems symptoms, particularly about childhood insomnia (at least one of the following five criteria: a) difficulties in sleep initiation ≥ 30 minutes; b) difficulties in maintaining sleep resulting in total nocturnal awakening time ≥ 30 minutes; c) nocturnal awakenings more than 2; d) resistance to go to bed; e) active parental intervention for falling asleep); frequency of excessive daytime somnolence; frequency of sleep attacks during the day; circadian disorders (anticipated phase, tendency to be very tired early in the evening and to wake up very early, and delayed phase, difficulty falling asleep in the evening and wakes up very late); snoring; sleepwalking; apprehension and anxiety before going to sleep; worries about sleep; sleep frustration and arousal disorders (night-time fear; confused arousal and easiness to reassure rated by parents). Each of these symptoms was rated by parents on the following scale: never; less than once per week; once or twice per week; all nights. Answers “never” or “less than once per week” were categorized as the absence of the sleep disorder/problem. Answers “once or twice per week” or “all nights” were categorized as the presence of the sleep disorder/problem.

Information on mood: parents were asked to rate on a scale from 1 to 100 how much during the lockdown period their children seemed happy, sad, anxious, angry and calm.

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted from May 10th, 2020, date in which the recruitment was concluded. Data analyses were conducted by a professional biostatistician (MC) and were performed with R (Version 3.5.1.).

Two analysis populations were defined, the enrolled set (ES) which comprised all participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria, and the main analysis set (MAS) which included all participants of the ES for whom sleep-related variables were completely evaluable. Descriptive analysis of sample characteristics did not reveal any substantial differences between the two analysis populations. All further analyses were conducted on the MAS. Results for descriptive statistics were expressed in means ± standard deviations for continuous variables and in absolute and relative frequencies for categorical variables. A logistic multivariable regression model was used to estimate the association between several independent variables considered as predictors and presence or absence of at least one diagnostic criterion for childhood insomnia as an outcome. Predictors included sex (males; females); age; BMI; respondent (mother; father; both); mood ratings (happy; sad; anxious; angry; calm); region (north; other); family composition (parents with two or more children; single parent, parents with one child; parents with children and other family members); current parental insomnia (yes; no); worry about COVID-19 pandemic (not at all; a little; quite a bit; much; very much); family tested positive (yes; no); usual bedtime (after 10 p.m.; between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m.; between 8 p.m. and 9 p.m.; between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m.); falling asleep alone (yes; no); regular sleep times (yes; no); pre-bed routine; active use of the bed in the evening; caffeine; active play in the evening (all nights; never; less than once per week; once or twice per week); the presence of any other sleep disorders (yes; no).

Results

Family characteristics

A total of 2720 individuals gave consent and answered the survey. In table 1 the main sample characteristics are resumed, 2361 participants’ data were used for the main analyses (MAS).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Family characteristics | Total | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent N (%) | |||

| Mother | 2110 (89.4%) | 1030 (89.7%) | 1080 (89.0%) |

| Father | 247 (10.5%) | 117 (10.2%) | 130 (10.7%) |

| Mother and father | 4 (0.2%) | 1 ( 0.1%) | 3 ( 0.2%) |

| Nationality N (%) | |||

| Italian | 2262 (95.8%) | 1106 (96.3%) | 1156 (95.3%) |

| Other | 92 ( 3.9%) | 38 ( 3.3%) | 54 ( 4.5%) |

| Region | |||

| North | 1769 (74.9%) | 863 (75.2%) | 906 (74.7%) |

| Centre | 315 (13.3%) | 152 (13.2%) | 163(13.4%) |

| South | 216 (9.1%) | 101 (8.8%) | 115 (9.5%) |

| Islands | 61 ( 2.6%) | 32 (2.8%) | 29 (2.4%) |

| Family type N (%) | |||

| Single parent | 197 (8.3%) | 91 (7.9%) | 106 (8.7%) |

| Parents with one child | 645 (27.3%) | 331 (28.8%) | 314 (25.9%) |

| Parents with two or more children | 1488 (63.0%) | 710 (61.8%) | 778 (64.1%) |

| Parents with children and other family members | 31 ( 1.3%) | 16 ( 1.4%) | 15 ( 1.2%) |

| Current insomnia N (%) | |||

| Yes | 946 ( 40.1%) | 447 ( 38.9%) | 499 ( 41.1%) |

| No | 1415 ( 59.9%) | 701 ( 61.1%) | 714 ( 58.9%) |

| Past insomnia N (%) | |||

| Yes | 462 ( 19.6%) | 224 ( 19.5%) | 238 ( 19.6%) |

| No | 1899 ( 80.4%) | 924 ( 80.5%) | 975 ( 80.4%) |

| Children characteristics | |||

| Age (Mean ± Sd) | 8.1 ± 2.62 | 8 ± 2.57 | 8.2 ± 2.67 |

| Sex N (%) | 1148 ( 48.6%) | 1213 ( 51.4%) | |

| BMI (Mean ± Sd) | 17.2 ± 3.94 | 17 ± 4.69 | 17.4 ± 3.06 |

| Adopted | |||

| Yes | 22 ( 0.9%) | 6 ( 0.5%) | 16 ( 1.3%) |

| No | 2339 ( 99.1%) | 1142 ( 99.5%) | 1197 ( 98.7%) |

| School N (%) | |||

| Nursery or no school | 29 ( 1.2%) | 17 ( 1.5%) | 12 ( 1.0%) |

| Kindergarten | 421 ( 17.8%) | 219 ( 19.1%) | 202 ( 16.7%) |

| Primary school | 1473 ( 62.4%) | 728 ( 63.4%) | 745 ( 61.4%) |

| First level secondary school | 435 ( 18.4%) | 182 ( 15.9%) | 253 ( 20.9%) |

| Other | 3 ( 0.1%) | 2 ( 0.2%) | 1 ( 0.1%) |

| Extra scholastic activity N (%) | |||

| Yes | 1772 ( 75.1%) | 880 ( 76.7%) | 892 ( 73.5%) |

| No | 589 ( 24.9%) | 268 ( 23.3%) | 321 ( 26.5%) |

| Physical activities N (%) | |||

| Yes | 1589 ( 67.3%) | 745 ( 64.9%) | 844 ( 69.6%) |

| No | 772 ( 32.7%) | 403 ( 35.1%) | 369 ( 30.4%) |

| Medical disorders N (%) | |||

| Yes | 170 ( 7.2%) | 65 ( 5.7%) | 105 ( 8.7%) |

| No | 2191 ( 92.8%) | 1083 ( 94.3%) | 1108 ( 91.3%) |

| Drugs N (%) | |||

| Yes | 153 ( 6.5%) | 61 ( 5.3%) | 92 ( 7.6%) |

| No | 2208 ( 93.5%) | 1087 ( 94.7%) | 1121 ( 92.4%) |

| Variables associated with COVID-19 outbreak | |||

| Worry about COVID-19 N (%) | |||

| Very much | 157 ( 6.6%) | 77 ( 6.7%) | 80 ( 6.6%) |

| Much | 606 ( 25.7%) | 269 ( 23.4%) | 337 ( 27.8%) |

| Quite a bit | 1355 ( 57.4%) | 677 ( 59.0%) | 678 ( 55.9%) |

| A little | 228 ( 9.7%) | 118 ( 10.3%) | 110 ( 9.1%) |

| Not at all | 15 ( 0.6%) | 7 ( 0.6%) | 8 ( 0.7%) |

| Infected N (%) | |||

| Yes | 106 (4.5%) | 50 (4.4%) | 56 (4.6%) |

| No | 2255 ( 95.5%) | 1098 ( 95.6%) | 1157 ( 95.4%) |

| School during COVID-19 N (%) | |||

| Video lessons and online homework | 613 ( 22.5%) | 301 ( 22.3%) | 312 ( 22.7%) |

| Only video lessons | 898 ( 33.0%) | 434 ( 32.2%) | 464 ( 33.8%) |

| Only online homework | 923 ( 33.9%) | 464 ( 34.4%) | 459 ( 33.5%) |

| No online school | 167 ( 6.1%) | 85 ( 6.3%) | 82 ( 6.0%) |

| Other | 119 ( 4.4%) | 64 ( 4.7%) | 55 ( 4.0%) |

| Extra-scholastic activity online | |||

| Yes | 469 ( 19.9%) | 265 ( 23.1%) | 204 ( 16.8%) |

| No | 1642 ( 69.5%) | 764 ( 66.6%) | 878 ( 72.4%) |

In 89.4% of cases, the mother was the respondent, in 10.5% cases the father answered to the questions and in 0.2% cases both parents filled in the survey together. Most participants had Italian nationality (95.8%). Participants were distributed on all Italian territory: the majority of respondents were from North of Italy, including 8 regions (74.9%); 13.3% of respondents were from Centre of Italy; 9.1% from South of Italy, and 2.6% from the Islands. Most respondents were parents in families with only one child (31.5%) or two or more (51.9%) children; 8.3% were single parents. The 40.1% of parents reported suffering of current insomnia and 19.6% of past insomnia. Only the 0.9% were parents of adopted children.

Children characteristics

The mean age of children was 8.1 ± 2.62 years. Most respondents were parents of children aged between 6 to 12 years (83.3%), 15.3% of children between 3 to 5 years and 1.2% of children aged between 0 to 2 years. The sample was composed of 1148 females (48.6%) and 1213 males (51.8%). Average BMI of children aged 0-2 years was 17.7 ± 3.51; for children aged 3-5 years average BMI was 15.5 ± 2.23 and for children aged 6-12 years was 17.6 ± 4.11. Considering all age groups together, 10.1% of children were categorized as “overweight” and 1.3% as “obese” following Italian reference data (Cacciari et al., 2006). “Overweight” and “obesity” was more common in boys (respectively 13.8% and 1.6% of all boys) compared to girls (6.8% and 1.0% of all girls). The 0.9% of children were adopted. Most children attended primary school (62.4%), 1.2% attended nursery or did not attend any daily care, 17.8% attended kindergarten and 18.4% the first level secondary school. Furthermore, 75.1% of children attended extra-scholastic and physical activities (67.3%) before the COVID-19 pandemic. The 7.2% of children were reported to suffer of a medical disorder and 6.5% to take medical drugs.

Variables associated with COVID-19 outbreak

57.4% of parents reported being quite a bit worried about COVID-19, while 25.7% reported being very worried (in a scale from not at all to very much; see instruments, general information section). 4.5% of parents reported that one family member had been infected by COVID-19 infection. 22.7% of children continued to attend video lessons and to do online homework during home confinement, 32.8% did only video lessons and 34.3% only online homework. The 5.9% of children did not attend online school and only 19.9% of children continued to do extra scholastic activities during home confinement.

Sleep health related habits and patterns

Sleep habits of children during COVID-19 pandemic were evaluated and results are resumed in table 2. Results showed that bedtime before 8 p.m. is rare in Italian children (no children aged between 0 – 2 years; 0.6% of children aged 3-5 years; 0.2% of children aged 6-12 years.

Table 2.

Sleep health related habits and patterns

| Sleep patterns | Age 0-2 years | Age 3-5 years | Age 6-12 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bedtime N (%) | |||

| Between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m. | 0 ( 0.0%) | 2 ( 0.6%) | 4 ( 0.2%) |

| Between 8 p.m. and 9 p.m. | 7 ( 20.6%) | 43 ( 11.9%) | 142 ( 7.2%) |

| Between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m. | 14 ( 41.2%) | 182 ( 50.4%) | 884 ( 45.0%) |

| After 10 p.m. | 13 ( 38.2%) | 134 ( 37.1%) | 936 ( 47.6%) |

| Wake up time N (%) | |||

| Before 6 a.m. | 1 ( 2.9%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 6 ( 0.3%) |

| Between 6 a.m. and 7 a.m. | 10 ( 29.4%) | 35 ( 9.7%) | 136 ( 6.9%) |

| Between 7 a.m. and 8 a.m. | 7 ( 20.6%) | 97 ( 26.9%) | 561 ( 28.5%) |

| Between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. | 11 ( 32.4%) | 132 ( 36.6%) | 686 ( 34.9%) |

| Between 9 a.m. and 10 a.m. | 4 ( 11.8%) | 64 ( 17.7%) | 436 ( 22.2%) |

| Between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m. | 1 ( 2.9%) | 31 ( 8.6%) | 114 ( 5.8%) |

| After 11 a.m. | 0 ( 0.0%) | 2 ( 0.6%) | 27 ( 1.4%) |

| Total sleep time N (%) | |||

| < 7 h | 3 ( 8.8%) | 11 ( 3.0%) | 45 ( 2.3%) |

| 7-9 h | 19 ( 55.9%) | 135 ( 37.4%) | 888 ( 45.2%) |

| 9-11 h | 12 ( 35.3%) | 206 ( 57.1%) | 994 ( 50.6%) |

| > 11 h | 0 ( 0.0%) | 9 ( 2.5%) | 39 ( 2.0%) |

| Sleep onset latency N (%) | |||

| < 5 min | 3 ( 8.8%) | 59 ( 16.3%) | 552 ( 28.1%) |

| 10-20 min | 17 ( 50.0%) | 205 ( 56.8%) | 1024 ( 52.1%) |

| 30-40 min | 8 ( 23.5%) | 63 ( 17.5%) | 249 ( 12.7%) |

| > 40 min | 6 ( 17.6%) | 34 ( 9.4%) | 141 ( 7.2%) |

| Number of awakenings N (%) | |||

| 0 | 14 ( 41.2%) | 139 ( 38.5%) | 1333 ( 67.8%) |

| 1 | 6 ( 17.6%) | 151 ( 41.8%) | 463 ( 23.6%) |

| 2 | 8 ( 23.5%) | 47 ( 13.0%) | 128 ( 6.5%) |

| 3 | 6 ( 17.6%) | 20 ( 5.5%) | 32 ( 1.6%) |

| ≥4 | 0 ( 0.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) |

| Sleep habits | |||

| Difficulties to wake up N (%) | |||

| Yes | 5 ( 14.7%) | 72 ( 19.9%) | 613 ( 31.2%) |

| No | 29 ( 85.3%) | 289 ( 80.1%) | 1353 ( 68.8%) |

| Sleep place N (%) | |||

| Alone | 9 ( 26.5%) | 100 ( 27.7%) | 802 ( 40.8%) |

| In the same room with siblings | 13 ( 38.2%) | 104 ( 28.8%) | 817 ( 41.6%) |

| In the same room of the parents | 12 ( 35.3%) | 136 ( 37.7%) | 266 ( 13.5%) |

| Other | 0 ( 0.0%) | 21 ( 5.8%) | 81 ( 4.1%) |

| Falling asleep N (%) | |||

| Alone in his/her bed | 17 ( 50.0%) | 107 ( 29.6%) | 1244 ( 63.3%) |

| Hold in arms | 3 ( 8.8%) | 10 ( 2.8%) | 15 ( 0.8%) |

| Cradled | 1 ( 2.9%) | 8 ( 2.2%) | 13 ( 0.7%) |

| Holding hand | 4 ( 11.8%) | 72 ( 19.9%) | 175 ( 8.9%) |

| In front of the TV | 2 ( 5.9%) | 37 ( 10.2%) | 199 ( 10.1%) |

| Other | 7 ( 20.6%) | 127 ( 35.2%) | 320 ( 16.3%) |

| Number of naps N (%) | |||

| Never | 13 ( 38.2%) | 243 ( 67.3%) | 1912 ( 97.3%) |

| 1 | 19 ( 55.9%) | 118 ( 32.7%) | 54 ( 2.7%) |

| 2 or more | 2 ( 5.9%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) |

| Drugs N (%) | |||

| Yes | 2 ( 5.9%) | 18 ( 5.0%) | 59 ( 3.0%) |

| No | 32 ( 94.1%) | 343 ( 95.0%) | 1907 ( 97.0%) |

| Sleep hygiene | |||

| Regular sleep times N (%) | |||

| Yes | 27 ( 79.4%) | 286 ( 79.2%) | 1616 ( 82.2%) |

| No | 7 ( 20.6%) | 75 ( 20.8%) | 350 ( 17.8%) |

| Pre-bed routines N (%) | |||

| Never | 8 ( 23.5%) | 28 ( 7.8%) | 414 ( 21.1%) |

| Less than once per week | 2 ( 5.9%) | 8 ( 2.2%) | 38 ( 1.9%) |

| Once or twice per week | 0 ( 0.0%) | 16 ( 4.4%) | 88 ( 4.5%) |

| All nights | 24 ( 70.6%) | 309 ( 85.6%) | 1426 ( 72.5%) |

| Active use of bed during the day N (%) | |||

| Never | 19 ( 55.9%) | 192 ( 53.2%) | 1089 ( 55.4%) |

| Less than once per week | 6 ( 17.6%) | 53 ( 14.7%) | 258 ( 13.1%) |

| Once or twice per week | 4 ( 11.8%) | 64 ( 17.7%) | 379 ( 19.3%) |

| Always | 0 ( 0.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) |

| Active use of bed in the evening N (%) | |||

| Never | 23 ( 67.6%) | 234 ( 64.8%) | 1349 ( 68.6%) |

| Less than once per week | 5 ( 14.7%) | 40 ( 11.1%) | 223 ( 11.3%) |

| Once or twice per week | 4 ( 11.8%) | 50 ( 13.9%) | 276 ( 14.0%) |

| All nights | 2 ( 5.9%) | 37 ( 10.2%) | 118 ( 6.0%) |

| Caffeine use N (%) | |||

| Never | 22 ( 64.7%) | 199 ( 55.1%) | 977 ( 49.7%) |

| Less than once per week | 6 ( 17.6%) | 61 ( 16.9%) | 489 ( 24.9%) |

| Once or twice per week | 6 ( 17.6%) | 92 ( 25.5%) | 481 ( 24.5%) |

| Always | 0 ( 0.0%) | 9 ( 2.5%) | 19 ( 1.0%) |

| Active playing in the evening N (%) | |||

| Never | 6 ( 17.6%) | 66 ( 18.3%) | 756 ( 38.5%) |

| Less than once per week | 4 ( 11.8%) | 70 ( 19.4%) | 429 ( 21.8%) |

| Once or twice per week | 12 ( 35.3%) | 116 ( 32.1%) | 556 ( 28.3%) |

| All nights | 12 ( 35.3%) | 109 ( 30.2%) | 225 ( 11.4%) |

Most children in all age ranges went to bed after 9 p.m. (45.7%), or after 10 p.m. (45.9%). Children of all ages mostly woke up between 8 a.m. and 9 a.m. (35.1%) and a small percentage before 7 a.m. (8%).

In the age range 0-2 years, nocturnal sleep lasted on average within 7 and 9 hours (55%). Children aged 3-5 years and 6-12 years had an average duration of nocturnal sleep within 9-11 hours (56.6% and 50.7%) and a small percentage less than 7 hours (respectively 2.6% and 2.2%) or more than 11 hours (2.9% and 2.0%). 55.9% of children aged 0-2 years had 1 nap, while 67.3% of children aged 3-5 years and 97.3% of children aged 6-12 years took no naps.

The majority of children in all age ranges had sleep onset latency ranging from 10 to 20 minutes (52.8%) and most of the children (62.9%) were reported to have 0 awakenings in all age ranges.

Most parents (70.8%) reported no difficulties in waking up in the morning in their children. Furthermore, 35.2% of children aged 0-2 years, 37.7% of children aged 3-5 years and 13.4% of children aged 6-12 years used to sleep in the same room of parents. 50% of children aged 0-2 years, 26.9% of children aged 3-5 years and 63.3% of children aged 6-12 years were able to fall asleep alone in their bed.

A small percentage of children in all age ranges (3.3%) took drugs to sleep. Of the full sample, 2.2% took melatonin.

Regarding sleep hygiene habits, most children in all age ranges had regular sleep times during home confinement (81.7%), pre-bed routines every night (70%), and did not use the bed actively during the day (55.1%) and in the evening (68%).

Finally, 17.6% of children aged 0-2 years, 25.5% of children aged 3-5 years and 24.5% of children aged 6-12 years used caffeine once or twice per week. 35.3% of children aged 0-2 years, 30.2% aged 3-5 years and 11.4% aged 6-12 years played actively during the evening.

Sleep problems and positive and negative emotions

Results are resumed in table 3. 76.5% of children aged 0-2 years, 78.9% of children aged 3-5 years and 55.5% of children aged 6-12 years presented at least one criterion for childhood insomnia (a)difficulties in sleep initiation ≥ 30 minutes; b) difficulties in maintaining sleep resulting in total nocturnal awakening time ≥ 30 minutes; c) nocturnal awakenings more than 2; d) resistance to go to bed; e) active parental intervention for falling asleep). Excessive somnolence all nights was reported for 2.9% of children aged 0-2 years, 0.8% of children aged 3-5 years and 1% of children aged 6-12 years Furthermore, the 2.9% of children aged 0-2 years, the 1.1% of children aged 3-5 years and the 1% of children aged 6-12 years were reported to have sleep attacks during the day. Evaluating circadian disorders, results showed that reporting delayed phase problems all nights was more frequent (14.5%) compared to reporting anticipated phase problems (2.5%) in all age groups children.

Table 3.

Prevalence of sleep disorders

| Sleep disorders | Age 0-2 years | Age 3-5 years | Age 6-12 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Childhood Insomnia N (%) | |||

| Yes | 1586 ( 58.3%) | 789 ( 58.5%) | 797 ( 58.1%) |

| No | 1090 ( 40.1%) | 531 ( 39.4%) | 559 ( 40.7%) |

| Excessive somnolence N (%) | |||

| Never | 20 ( 58.8%) | 238 ( 65.9%) | 1398 ( 71.1%) |

| Less than once per week | 8 ( 23.5%) | 67 ( 18.6%) | 318 ( 16.2%) |

| Once or twice per week | 5 ( 14.7%) | 53 ( 14.7%) | 228 ( 11.6%) |

| All nights | 1 ( 2.9%) | 3 ( 0.8%) | 20 ( 1.0%) |

| Sleep attacks N (%) | |||

| Never | 30 ( 88.2%) | 327 ( 90.6%) | 1864 ( 94.8%) |

| Less than once per week | 3 ( 8.8%) | 30 ( 8.3%) | 82 ( 4.2%) |

| Once or twice per week | 1 ( 2.9%) | 4 ( 1.1%) | 19 ( 1.0%) |

| All nights | 0 ( 0.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) |

| Circadian disorders - Anticipated phase N (%) | |||

| Never | 19 ( 55.9%) | 247 ( 68.4%) | 1574 ( 80.1%) |

| Less than once per week | 7 ( 20.6%) | 63 ( 17.5%) | 240 ( 12.2%) |

| Once or twice per week | 5 ( 14.7%) | 36 ( 10.0%) | 107 ( 5.4%) |

| All nights | 3 ( 8.8%) | 14 ( 3.9%) | 43 ( 2.2%) |

| Circadian disorders - Delayed phase N (%) | |||

| Never | 15 ( 44.1%) | 187 ( 51.8%) | 1022 ( 52.0%) |

| Less than once per week | 11 ( 32.4%) | 68 ( 18.8%) | 346 ( 17.6%) |

| Once or twice per week | 3 ( 8.8%) | 62 ( 17.2%) | 301 ( 15.3%) |

| All nights | 5 ( 14.7%) | 44 ( 12.2%) | 294 ( 15.0%) |

| Disorders of arousal - night-time fear N (%) | |||

| Never | 18 ( 52.9%) | 232 ( 64.3%) | 1570 ( 79.9%) |

| Less than once per week | 5 ( 14.7%) | 78 ( 21.6%) | 256 ( 13.0%) |

| Once or twice per week | 5 ( 14.7%) | 39 ( 10.8%) | 111 ( 5.6%) |

| All nights | 6 ( 17.6%) | 11 ( 3.0%) | 28 ( 1.4%) |

| Disorders of arousal - Confusional arousal N (%) | |||

| Never | 21 ( 61.8%) | 242 ( 67.0%) | 1689 ( 85.9%) |

| Less than once per week | 8 ( 23.5%) | 92 ( 25.5%) | 205 ( 10.4%) |

| Once or twice per week | 3 ( 8.8%) | 22 ( 6.1%) | 63 ( 3.2%) |

| All nights | 2 ( 5.9%) | 5 ( 1.4%) | 9 ( 0.5%) |

| Disorders of arousal - Consolation N (%) | |||

| Never | 17 ( 50.0%) | 233 ( 64.5%) | 1359 ( 69.1%) |

| Less than once per week | 6 ( 17.6%) | 50 ( 13.9%) | 94 ( 4.8%) |

| Once or twice per week | 4 ( 11.8%) | 15 ( 4.2%) | 35 ( 1.8%) |

| All nights | 0 ( 0.0%) | 4 ( 1.1%) | 18 ( 0.9%) |

| Sleep Apnea- Snoring N (%) | |||

| Never | 20 ( 58.8%) | 208 ( 57.6%) | 1210 ( 61.5%) |

| Less than once per week | 10 ( 29.4%) | 68 ( 18.8%) | 397 ( 20.2%) |

| Once or twice per week | 4 ( 11.8%) | 56 ( 15.5%) | 251 ( 12.8%) |

| All nights | 0 ( 0.0%) | 29 ( 8.0%) | 102 ( 5.2%) |

| Parasomnias - Sleep walking N (%) | |||

| Never | 33 ( 97.1%) | 336 ( 93.1%) | 1774 ( 90.2%) |

| Less than once per week | 1 ( 2.9%) | 18 ( 5.0%) | 147 ( 7.5%) |

| Once or twice per week | 0 ( 0.0%) | 5 ( 1.4%) | 37 ( 1.9%) |

| All nights | 0 ( 0.0%) | 1 ( 0.3%) | 5 ( 0.3%) |

| Sleep Anxiety N (%) | |||

| Never | 26 ( 76.5%) | 304 ( 84.2%) | 1527 ( 77.7%) |

| Less than once per week | 4 ( 11.8%) | 20 ( 5.5%) | 200 ( 10.2%) |

| Once or twice per week | 2 ( 5.9%) | 19 ( 5.3%) | 142 ( 7.2%) |

| All nights | 2 ( 5.9%) | 18 ( 5.0%) | 94 ( 4.8%) |

| Sleep Worries N (%) | |||

| Never | 25 ( 73.5%) | 252 ( 69.8%) | 1304 ( 66.3%) |

| Less than once per week | 6 ( 17.6%) | 63 ( 17.5%) | 379 ( 19.3%) |

| Once or twice per week | 3 ( 8.8%) | 29 ( 8.0%) | 201 ( 10.2%) |

| Always | 0 ( 0.0%) | 17 ( 4.7%) | 78 ( 4.0%) |

| Sleep Frustration N (%) | |||

| Never | 18 ( 52.9%) | 283 ( 78.4%) | 1363 ( 69.3%) |

| Less than once per week | 8 ( 23.5%) | 43 ( 11.9%) | 369 ( 18.8%) |

| Once or twice per week | 5 ( 14.7%) | 24 ( 6.6%) | 149 ( 7.6%) |

| All nights | 3 ( 8.8%) | 10 ( 2.8%) | 82 ( 4.2%) |

Night-time fear problems all nights were frequent in children aged 0-2 years (17.6%) compared to other age groups (3% for children aged 3-5 years and 1.4% for children aged 6-12 years). Confused arousal problems all nights were found in 5.9% of children aged 0-2 years; 1.4% of children aged 3-5 years; 0.5% of children aged 6-12 years. Consolation request all nights was scarcely present in all age groups (0% in children aged 0-2 years; 1.1% in children aged 3-5 years and 0.9 in children aged 6-12 years).

The 27.5% of children aged 0-2 years were reported to snore once per week. The 7.7% of children aged 3-5 years and 5% of children aged 6-12 years snored all nights.

Sleepwalking and sleep anxiety problems were not widespread in the sample (respectively 0.3% and 4.8% considering all age ranges together). 4% of children of all age groups presented sleep worries and 4% sleep frustration all nights.

Parents rated the intensity from 0 to 100 how much during the lockdown period their children felt different emotions (see instruments, information on mood section). Children aged 0-2 years compared to other age groups were reported to be happier (0-2 years: 74.5 ± 19.9; 3-5 years: 71.9 ± 25.2; 6-12 years: 68.7 ± 24.8), sadder (0-2 years: 33.9± 31.8; 3-5 years: 27.4 ± 23.8; 6-12 years: 29.3 ± 23.4) and more anxious (0-2 years: 28.9 ± 31.18; 3-5 years: 19.7 ± 24.01; 6-12 years: 23.7 ± 26.23). Mood “Angry” was rated as quite high from parents in all age groups. Children aged 0-2 years presented an average score of 48.6 ± 31.53; children aged 3-5 years presented an average score of 42.1 ± 30.79 and children aged 6-12 years presented an average score of 37.4 ± 29.6. Finally, mood “Calm” was scored quite similarly in all age groups (0-2 years: 67.8 ± 22.65; 3-5 years: 68.9 ± 26.16; 6.12 years: 65.8 ± 27.09).

Associated factors to childhood insomnia

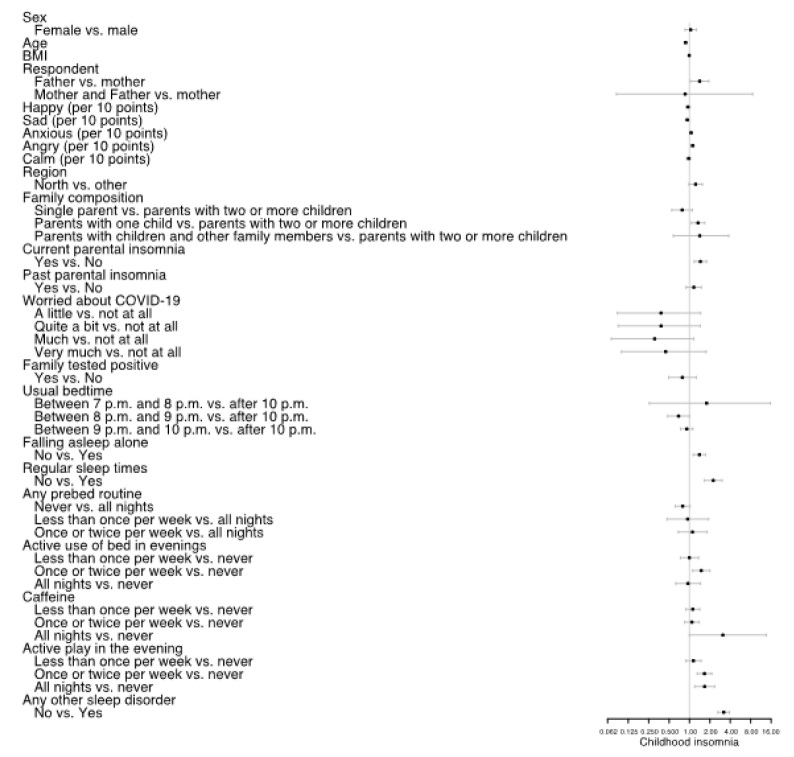

Results of the logistic regression model are resumed in figure 1, while specific results for all investigated covariates are available in Supporting Information, Document S1. Large effects were detected for age (OR= 0.88, 95% CI [0.84; 0.92], p<0.001) showing that younger age is more associated to childhood insomnia. Furthermore, a significant association of negative emotions was found but not with positive emotions. Particularly, mood “Sad” was found to be associated to less childhood insomnia (OR=0.93, 95% CI [0.88, 0.98], p=0.013); “Anxious” and “Angry” were significantly associated to higher prevalence of childhood insomnia (respectively, OR=1.06, 95% CI [1.00, 1.11], p=0.032 and OR=1.11, 95% CI [1.07, 1.17], p<0.001). Results also showed that current parental insomnia compared to the absence of parental insomnia (OR=1.45, 95% CI [0.90, 1.50], p<0.001) and the presence of any other sleep problem than insomnia compared to the absence of this condition (OR=3.20 95% CI [2.62, 3.90], p<0.001) are significantly associated to the presence of childhood insomnia.

Figure 1.

Forest plot of logistic regression model

Document S1.

Logistic regression model

| Logistic regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| MAS | |||

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | Reference | ||

| Female | 1.04 | [0.86, 1.27] | 0.6664 |

| Age | 0.88 | [0.84, 0.92] | <0.001 |

| BMI | 0.99 | [0.96, 1.02] | 0.4999 |

| Respondent | |||

| Mother | Reference | ||

| Father | 1.41 | [1.03, 1.94] | 0.0318 |

| Mother and Father | 0.86 | [0.08, 8.56] | 0.8945 |

| Happy (per 10 points) | 0.95 | [0.89, 1.02] | 0.1557 |

| Sad (per 10 points) | 0.93 | [0.88, 0.98] | 0.0133 |

| Anxious (per 10 points) | 1.06 | [1.00, 1.11] | 0.0326 |

| Angry (per 10 points) | 1.11 | [1.07, 1.17] | <0.001 |

| Calm (per 10 points) | 0.97 | [0.92, 1.03] | 0.3807 |

| Region | |||

| Other | Reference | ||

| North | 1.23 | [0.98, 1.55] | 0.0718 |

| Family composition | |||

| Parents with two or more children | Reference | ||

| Single parent | 0.78 | [0.55, 1.11] | 0.1657 |

| Parents with one child | 1.34 | [1.07, 1.68] | 0.0115 |

| Parents with children and other | |||

| family members | 1.42 | [0.58, 3.80] | 0.4615 |

| Current parental insomnia | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.45 | [1.18, 1.79] | <0.001 |

| Past parental insomnia | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 1.16 | [0.90, 1.50] | 0.2651 |

| Worried about COVID-19 | |||

| Not at all | Reference | ||

| A little | 0.38 | [0.09, 1.47] | 0.1743 |

| Quite a bit | 0.38 | [0.09, 1.44] | 0.1686 |

| Much | 0.31 | [0.07, 1.16] | 0.0928 |

| Very much | 0.45 | [0.10, 1.77] | 0.2652 |

| Family tested positive | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 0.79 | [0.49, 1.26] | 0.3123 |

| Usual bedtime | |||

| After 10 p.m. | Reference | ||

| Between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m. | 1.79 | [0.26, 15.72] | 0.5652 |

| Between 8 p.m. and 9 p.m. | 0.69 | [0.48, 1.00] | 0.0522 |

| Between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m. | 0.91 | [0.74, 1.13] | 0.3982 |

| Falling asleep alone | |||

| Yes | Reference | ||

| No | 1.40 | [1.13, 1.73] | 0.0018 |

| Regular sleep times | |||

| Yes | Reference | ||

| No | 2.24 | [1.67, 3.04] | <0.001 |

| Any prebed routine | |||

| All nights | Reference | ||

| Never | 0.79 | [0.62, 1.02] | 0.0758 |

| Less than once per week | 0.94 | [0.47, 1.92] | 0.8647 |

| Once or twice per week | 1.11 | [0.68, 1.82] | 0.6842 |

| Active use of bed in evenings | |||

| Never | Reference | ||

| Less than once per week | 1.00 | [0.73, 1.36] | 0.9905 |

| Once or twice per week | 1.49 | [1.11, 2.01] | 0.0082 |

| All nights | 0.95 | [0.63, 1.46] | 0.8169 |

| Caffeine | |||

| Never | Reference | ||

| Less than once per week | 1.12 | [0.88, 1.42] | 0.3558 |

| Once or twice per week | 1.09 | [0.85, 1.39] | 0.5038 |

| All nights | 3.11 | [1.00, 13.72] | 0.0792 |

| Active play in the evening | |||

| Never | Reference | ||

| Less than once per week | 1.15 | [0.88, 1.49] | 0.3074 |

| Once or twice per week | 1.66 | [1.30, 2.13] | <0.001 |

| All nights | 1.67 | [1.19, 2.35] | 0.0030 |

| Any other sleep disorder | |||

| No | Reference | ||

| Yes | 3.20 | [2.62, 3.91] | <0.001 |

Family composition, and particularly parents with one child only, was associated with a higher prevalence of childhood insomnia compared to parents with two or more children (OR=1.34, 95% CI [1.07, 1.68], p=0.011). Furthermore, father as respondent, compared to mother as respondent, was associated with a higher prevalence of childhood insomnia (OR=1.41, 95% CI [1.03, 1.94], p=0.031).

Results showed a significant association of inability to fall asleep alone with the presence of childhood insomnia (OR=1.40, 95% CI [1.13, 1.73], p=0.001). Finally, results highlighted a significant role of sleep hygiene behaviors, particularly, regular sleep times compared to irregular sleep times (OR=2.24, 95% CI [1.67, 3.04], p<0.001) and active play in the evening compared to the absence of this habit (OR=1.66, 95% CI [1.30, 2.16], p<0.001) as predictors of childhood insomnia presence. Interesting, though the result did not show statistical significance, a trend emerged for children that were living in the North of Italy compared to living in other parts of Italy (OR=1.23, 95% CI [0.98, 1.55], p=0.071) showing higher rates of childhood insomnia compared to Centre and South. Furthermore, bedtime between 8 p.m. and 9 p.m. (OR=0.69, 95% CI [0.48, 1.00], p=0.052) seems to predict fewer rates of childhood insomnia comparing to bedtime after 10 p.m., though statistical significance was not reached.

Discussion and clinical implications

This was a large survey study aiming at evaluating sleep habits, sleep problems, insomnia symptoms and emotions' intensity in Italian children (aged 0-12 years) during home confinement due to COVID-19 pandemic.

Descriptive results showed data about lifestyles and routines of Italian children during the lockdown, particularly results showed a reduction of school activities and extra-scholastic activities (5.9% of children did not attend online school and only 19.9% of children continued to do extra scholastic activities during home confinement). This is of utmost importance because in Italy measures of home confinement and social distancing were particularly strict and lasted long (school closed on the beginning of March 2020 and reopened in September 2020). For 8 weeks, children could only stay at home with their parents, with limited permission to go outside (within 200 meters from home) and without having contact with other people and/ or familiars. This unprecedented stressful condition, consistently with reviews and editorials alarming for the risk (Altena et al., 2020; Becker & Gregory, 2020), was associated with poor sleep hygiene and prevalence of sleep problems, especially for childhood insomnia. Furthermore, recent literature highlighted that Italian parents, and particularly mothers, seems to be significantly stressed by this situation (Marchetti et al., 2020).

Nevertheless, the presence of insomnia related problems is associated with a higher prevalence of other sleep problems, thus showing vulnerability for all clinical aspects of sleep of Italian children during home confinement. table 4 resumes result from this study comparing them with those available from international and Italian reference data.

Table 4.

Clinical strategies for different age children’ sleep issues

| Age groups | Sleep issues | Clinical strategies | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0-6 months | ✓ | Ability to self-soothe | ✓ | Daily schedule and consistent feeding itmes and sleep itmes; |

| ✓ | Sleep consolidaiton during the night | ✓ | Beditme rouitne and sleep schedule; | |

| ✓ | Sleep onset associaiton | ✓ | Put the child to sleep drowsy but awake | |

| 6-12 months | ✓ | Beditme rouitnes | ✓ | Discourage parental reinforcement of nigh awakenings; |

| ✓ | Night feeding | ✓ | Encourage beditme rouitne and regular beditme. | |

| 1-3 years | ✓ | Nap | ✓ | Single daily nap period; |

| ✓ | Use of electronic device | ✓ | Discourage electronic use at beditme; | |

| ✓ | Parental limit seittng. | |||

| 3-5 years | ✓ | Co-sleeping | ✓ | Encourage obtaining sufficient sleep; |

| ✓ | Sleep schedules | ✓ | Parental limit seittng. | |

| ✓ | Appropriate beditme | ✓ | Discourage electronic use at beditme and encourage no televisions or other electronics in the child's bedroom. | |

| ✓ | Insufficient sleep | |||

| 6-12 years | ✓ | Irregular sleep wake schedules | ✓ | Encourage obtaining sufficient sleep and appropriate bedtime. |

| ✓ | Later beditme | |||

| ✓ | Decreased nighittme sleep | ✓ | Discourage electronic use beditme and encourage no televisions or other electronics in the child's bedroom. | |

| ✓ | Increased caffeine intake | |||

| ✓ | Use of electronic device | ✓ | Discourage caffeine use. | |

| ✓ | Consistent sleep schedule between weekdays and weekends |

Table 5.

A comparison between sleep related data during COVID-19 and international and Italian reference data

| Variables | COVID-19 data | Italian data | Reference data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bedtime | 45.7%: between 9 p.m. and 10 p.m.; | Bacaro et al., 2019: | 7 p.m. and 8 p.m. |

| 45.9% after 10 p.m. | 49% after 10 p.m.; | ||

| Bisogni et al., 2015: | |||

| 40% between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m. | |||

| Total sleep duration | 2.5% < 7 h; | Chindamo et al., 2019: | 11-17 hours |

| 44.1% 7-9 hours; | 9.97 h; | ||

| 51.3% 9-11 hours; | Bacaro et al., 8.6 h; | ||

| 2% > 11 hours | Bruni et al., 2002: 8.3 h; | ||

| Ficca et al., 2011: 9.3 h. | |||

| Insomnia prevalence | 76.5% of children aged 0-2 years; | n/a | 20-30% |

| 78.9% of children aged 3-5 years; | |||

| 55.5% of children aged 6-12 years. |

Results showed the poor presence of adaptive sleep hygiene behaviors, particularly, late bedtime was observed in all age ranges groups. This could be due to the effect of COVID-19 lockdown and consequent closure of schools, thus children during the pandemic could have less strict and rigorous daily and evening times. At the same time, this is in line with previous literature based on sleep aspects of Italian children which stated a delay in children bedtimes (e.g. Bacaro et al., 2019 found that 49% of their sample went to bed after 10 p.m., and Bisogni et al., 2015 found that the 40% of their sample went to bed between 10 p.m. and 11 p.m.). While international guidelines for children sleep recommends bedtimes for children between 7 p.m. and 8 p.m. (e.g. Mindell & Owens, 2015), results of logistic regression indicated a trend for the reduced presence of childhood insomnia symptoms for children going to bed before 9 p.m. compared to children going to bed after 10 p.m. This may have strong clinical and preventive implications. Specifically, previous evidence showed that children’ insomnia problems could be affected by unhealthy sleep hygiene behaviors and that a specific multicomponent program (targeting sleeping difficulties and enabling parents to establish positive sleep education strategies) was effective in significantly decreasing insomnia symptoms in children aged 5-10 years (Schlarb et al., 2011). Thus, better knowledge of sleep clinical and physiological aspects in the developmental age between Italian health professionals and parents seem of utmost importance. Several clinical interventions may be implemented in pediatric care in the post-pandemic context, which could be effective in ameliorating child’s and family’s sleep quality. These strategies include educational and behavioral strategies as the establishment of a regular sleep schedule that consists in estimating the approximate number of hours of sleep for the child (based on the sleep need recommendations) and determine a good bedtime and wake time to be followed each day (even in the weekends). Furthermore, an effective technique is the establishment of regular bedtime routines, this strategy consists in constructing with the child a regular routine to be applied every day in the 30 minutes before bedtime. The pre-bed routine should include calming activities (e.g. dressing for sleep, washing, reading). Moreover, as stated above, parent involvement in children’ sleep is a key factor in sleep hygiene intervention. Indeed, if parents are actively present at the time of sleep onset, the child may learn to fall asleep only if the condition of presence of a parent is satisfied (e.g. being rocked or fed). The child may then require the same conditions during the night after nocturnal awakenings. In the clinical setting, parents are discouraged to respond immediately to signaled inability to fall asleep and offered several strategies to teach their child to self-sooth and fall asleep without active parental involvement.

In table 4 principal sleep hygiene intervention for typical sleep issue in the different age groups are presented (Mindell & Owens, 2015).

In the post-pandemic context sleep hygiene and sleep behaviors of children could be very compromised and this could increase the risk for them to develop future chronic insomnia problems, thus, preventive and interventional programs should be delivered and adapted on this population. Our study showed high prevalence of night terrors in the full sample (22%), and specifically in younger children (0-2 years, 17.6%). This result suggests that life changes due to the pandemic’s outbreak could also enhance the need of parents during nighttime increasing the presence of nightmares or sleep terrors. This is particularly important because previous data reported that night-time fears and nightmares are very common concerns of parents (Mindell & Owens, 2015). Further strategies that could be added to the protocol for insomnia in children in the post-pandemic scenario in order to reduce anxiety around sleep or nightmares could be relaxation techniques and/ or mindfulness techniques (e.g. progressive muscle relaxation before bedtime).

Most of the children aged 0-2 years had total nocturnal sleep duration ranging between 7 and 9 hours; children aged 3-5 years and 6-12 years showed similar results: the most of them slept between 9 and11 hours. Comparing these results to previous Italian data, it emerges that nocturnal total sleep time is generally reduced during COVID-19 pandemic (average nocturnal sleep before the pandemic: more than 9 hours; Chindamo et al., 2019; Bruni et al., 2005, 2009; Ficca et al., 2011). This is particularly alarming considering National Sleep Foundation recommendation (Hirshkowitz et al., 2015), which states that adequate amount of sleep for newborns, infants and toddlers should range from a minimum of 11 hours to a maximum of 17 hours; and within 9 and 13 hours for preschoolers and school-age children. Although our question focused on nocturnal sleep duration, data suggested that most of Italian children of our sample hardly reaches recommended total sleep time, also considering data on daily naps habits (on average 1 hour for infants and toddlers and no naps’ habits in preschoolers and schoolers). Prevalence of childhood insomnia related problems (with at least one problem in sleep initiation, sleep maintenance, nocturnal awakenings, sleep resistance, parental involvement) was extremely high in our sample: in 76.5% of children aged 0-2 years, 78.9% of children aged 3-5 years and 55.5% of children aged 6-12 years. The specific prevalence of insomnia depends on the criteria adopted for assessments, incidence rate varies depending on the developmental stage, and on assessment methods (self-assessment questionnaires, parents’ questionnaires, actigraphy). However, estimates of prevalence rates of insomnia in childhood range between 20% to 30% (Owens & Mindell, 2011), which should alarm for a dramatic increase of insomnia symptomatology during COVID-19 pandemic in Italian children. No significant gender differences emerged from our results and no significant interaction of “sex” variable was found in the regression model. This could be due to the mean age of our sample and confirmed previous literature showing that gender differences start to be evident with the biological and cultural transition that characterize adolescence (Dahl & Lewin, 2002). Indeed, previous findings showed that the main sex differences in sleep arise with the first menstrual cycle, when ovarian function and female hormones increase regulating the sleep-wake cycle (Pengo, Won, Bourjeily, 2018). Furthermore, social and cultural aspects associated with the transition to adolescence may also influence gender differences in sleep quality.

Data of the logistic regression showed several factors which are associated with higher rates of childhood insomnia. Current parental insomnia is strictly associated with child insomnia related problems, which suggests that clinically sleep problems in children should be diagnosed and treated adopting a family perspective and considering dynamic interactions between family members. Presence of childhood insomnia symptomatology is linked with the higher complaint of other sleep disorders, which should always be evaluated and considered in a clinical setting for treatment of insomnia in the developmental age.

Sleep hygiene behaviors play an important role in the maintenance of childhood insomnia (Hall et al., 2019.). Consistently, irregular sleep times and active use of the bed, especially during the evening, were observed to be significant predictors of childhood insomnia symptomatology. The inability to fall asleep alone is strictly associated with higher rates of clinical insomnia in children, which is consistent with previous literature (Mindell & Owens, 2015). Similarly, irregular sleep times were observed to be linked with a higher presence of childhood insomnia symptoms. These results are of utmost importance because previous data pointed out that in Italy there is poor knowledge regarding the importance of sleep during the developmental age (Wolf et al., 1996) and most of parents and pediatricians in Italy are unlikely to discourage excessive active parental presence during the night, and usually do not promote proper sleep hygiene from early childhood (Giannotti et al., 2005). Especially in the post-pandemic phase, in which all efforts should be done to reduce the long-term consequences of the increased stress to which children and their families were exposed, adequate care and treatment for insomnia problems seem to be a health priority.

Younger children seem to be at higher risk for childhood insomnia during this pandemic situation. This result could also reflect rapid changes of sleep processes, which are key factors for brain optimization processes (such as growth, cognition, and behaviors). Particularly, newborns usually sleep most of the day and night and typically 1-year-old children sleep 10–12 h at night with two daily naps (Mindell & Carskadon, 1999). Learning to self-soothe and self-initiate sleep is an important development milestone at this age. Furthermore, lack of self-soothing and sleep consolidation is associated with increased risk for increased parental perceived stress (Marchetti et al., 2020).

Furthermore, to be a single child was also associated with higher rates of insomnia. Presence of siblings during lockdown may have represented a protective factor for children for sleep problems. A trend emerged for more childhood insomnia in the North of Italy, which is logically consistent with the widespread of the virus, which has dramatically interested mainly Lombardy and in general the north of the country. This may have been likely linked with increased stress and fear, which are factors associated with sleep impairment in all ages (Morin, Rodrigue & Ivers, 2003). Negative emotions were observed to be associated with the prevalence of childhood insomnia symptoms, while positive emotions weren’t. Specifically, experiencing intense angry and anxious mood was linked with higher rates of childhood insomnia. Being both sleep and emotion regulation functioning key processes for mental health (Palmer & Alfano, 2017), a clinical psychological intervention targeting both aspects may be particularly effective and worth to be empirically evaluated. Increased sad mood was observed to be linked with reduced rates of childhood insomnia symptomatology. This result is counterintuitive and indicates that much more research focusing on sleep and emotions during childhood is needed. Previous findings highlighted strong connection between insomnia and emotional aspects, particularly with positive and negative emotions (Baglioni et al., 2010). Since, as stated above, sleep problems could act as risk factors for future psychopathologies, complete and focused early diagnosis and early treatment of sleep difficulties are needed. Particularly, preventive sleep focused psychological intervention could ameliorate emotional aspects. Moreover, based on the available literature, combined interventions for sleep and emotion regulation skills in childhood may be very effective in preventing psychopathologies and may be promoted both in clinical care and in prevention contexts (e.g. schools).

Conclusion

The unexpected COVID-19 pandemic and consequent lockdown may have critical long-term consequences such as stress disorders, emotional disturbances and sleep disorders (Mucci et al., 2020). This could be particularly true for pediatric sleep health in Italian children considering literature published before 2020.

This literature already evidenced an alarming prevalence of childhood sleep behavioral difficulties and disorders and suggested to pay more clinical attention to this topic. Our data showed even higher prevalence and report of maladaptive sleep behaviors from families. This suggests that COVID-19 may have further impacted the sleep of Italian children, by worsening averagely quality. Consequently, based on longitudinal available literature, this may be linked to increased risk of psychopathologies during the development.

Primary pediatric care should pay increased attention to healthy sleep development, by implementing routinely diagnostic procedures and developing specific treatment offers. Preventive and interventional programs should be developed nationally as a response to the pandemic impact on psychological variables, considering sleep as a primary process for brain functioning and mental health (Bathory & Tomopoulos, 2017), thus, a key process to clinically assessment.

Considering our knowledge on the impact of poor sleep and insomnia for mental health during childhood, adolescence and adulthood (Armstrong et al., 2014), and the alarming results evidenced from the present study, these programs should be a health priority in Italy to cope with post-pandemic effects on children mental health.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the regional offices responsible and the directors of schools that helped us in spread our study to their contact, as well as all parents who filled in the survey. Furthermore, we would like to thank Mario Sossi who helped us in the research of contacts for scopes of his bachelor final work.

Footnotes

North: Lombardy, Piedmont, Veneto, Liguria, Emilia Romagna, Aosta Valley, Trentino Alto Adige, Friuli Venezia Giulia; Centre: Latium, Tuscany, Marche, Umbria; South: Abruzzo, Molise, Campania, Basilicata, Puglia, Calabria; Islands: Sicily, Sardinia.

References

- Alfano, C. A., Zakem, A. H., Costa, N. M., Taylor, L. K., & Weems, C. F. (2009). Sleep problems and their relation to cognitive factors, anxiety, and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. Depression and Anxiety, 26(6), 503-512. 10.1002/da.20443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altena, E., Baglioni, C., Espie, C. A., Ellis, J., Gavriloff, D., Holzinger, B., Schlarb, A., Frase, L., Jernelöv, S., & Riemann, D. (2020). Dealing with sleep problems during home confinement due to the COVID‐19 outbreak: Practical recommendations from a task force of the European CBT‐I Academy. Journal of Sleep Research, 29(4). 10.1111/jsr.13052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2005). International classification of sleep disorders. Diagnostic and Coding Manual, 51-55. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong, J. M., Ruttle, P. L., Klein, M. H., Essex, M. J., & Benca, R. M. (2014). Associations of child insomnia, sleep movement, and their persistence with mental health symptoms in childhood and adolescence. Sleep, 37(5), 901-909. 10.5665/sleep.3656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacaro, V., Feige, B., Ballesio, A., De Bartolo, P., Johann, A. F., Buonanno, C., Mancini, F., Lombardo, C., Riemann, D., & Baglioni, C. (2019). Considering Sleep, Mood, and Stress in a Family Context: A Preliminary Study. Clocks & Sleep, 1(2), 259–272. 10.3390/clockssleep1020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglioni, C., Spiegelhalder, K., Lombardo, C., & Riemann, D. (2010). Sleep and emotions: a focus on insomnia. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 14(4), 227-238. 10.1016/j.smrv.2009.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baglioni, C., Battagliese, G., Feige, B., Spiegelhalder, K., Nissen, C., Voderholzer, U., Lombardo, C., & Riemann, D. (2011). Insomnia as a predictor of depression: A meta-analytic evaluation of longitudinal epidemiological studies. Journal of Affective Disorders, 135(1–3), 10–19. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bathory, E., & Tomopoulos, S. (2017). Sleep regulation, physiology and development, sleep duration and patterns, and sleep hygiene in infants, toddlers, and preschool-age children. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care, 47(2), 29-42. 10.1016/j.cp-peds.2016.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S. P., & Gregory, A. M. (2020). Editorial Perspective: Perils and promise for child and adolescent sleep and associated psychopathology during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 61(7), 757–759. 10.1111/jcpp.13278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisogni, S., Chiarini, I., Giusti, F., Ciofi, D., Poggi, G. M., & Festini, F. (2015). Impact of hospitalization on the sleep patterns of newborns, infants and toddlers admitted to a pediatric ward: a cross-sectional study. Minerva Pediatrica, 67(3), 209-217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, O., Ferri, R., Miano, S., Verrillo, E., Vittori, E., Della Marca, G., Farina, B., & Mennuni, G. (2002). Sleep cyclic alternating pattern in normal school-age children. Clinical Neurophysiology, 113(11), 1806–1814. 10.1016/s1388-2457(02)00265-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, O., Ferri, R., Miano, S., Verrillo, E., Vittori, E., Farina, B., Smerieri, A., & Terzano, M. G. (2005). Sleep Cyclic Alternating Pattern in Normal Preschool-Aged Children. Sleep, 28(2), 220–232. 10.1093/sleep/28.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruni, O., Novelli, L., Finotti, E., Luchetti, A., Uggeri, G., Aricò, D., & Ferri, R. (2009). All-night EEG power spectral analysis of the cyclic alternating pattern at diferent ages. Clinical Neurophysiology, 120(2), 248–256. 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, O. M., Chang, A. M., Spilsbury, J. C., Bos, T., Emsellem, H., & Knutson, K. L. (2015). Sleep in the modern family: protective family routines for child and adolescent sleep. Sleep Health, 1(1), 15-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cacciari, E., Milani, S., Balsamo, A., Spada, E., Bona, G., Ca-vallo, L., Cerutti, F., Gargantini, L., Greggio, N., Tonini, G., & Cicognani, A. (2006) Italian cross-sectional growth charts for height, weight and BMI (2 to 20 yr). Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, 29(7), 581–593. 10.1007/bf03344156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaput, J.-P., Gray, C. E., Poitras, V. J., Carson, V., Gruber, R., Olds, T., Weiss, S. K., Connor Gorber, S., Kho, M. E., Sampson, M., Belanger, K., Eryuzlu, S., Callender, L., & Tremblay, M. S. (2016). Systematic review of the relationships between sleep duration and health indicators in school-aged children and youth. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 41(6 (Suppl. 3)), S266–S282. 10.1139/apnm-2015-0627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortese, S., Lecendreux, M., Mouren, M. C., & Konofal, E. (2006). ADHD and insomnia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 4(45), 384-385. 10.1097/01.chi.0000199577. 12145. bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortesi, F., Giannotti, F., Sebastiani, T., & Vagnoni, C. (2004). Cosleeping and sleep behavior in Italian school-aged children. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 25(1), 28-33. 10.1097/00004703-200402000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, R. E., & Lewin, D. S. (2002). Pathways to adolescent health sleep regulation and behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health, 31(6), 175–184. 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00506-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworak, M., Wiater, A., Alfer, D., Stephan, E., Hollmann, W., & Strüder, H. K. (2008). Increased slow wave sleep and reduced stage 2 sleep in children depending on exercise intensity. Sleep Medicine, 9(3), 266–272. 10.1016/j.sleep.2007.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El‐Sheikh, M., & Sadeh, A. (2015). I. Sleep and development: Introduction to the monograph. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 80(Serial No. 1), 1–14. 10.1111/mono.12141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ficca, G., Conte, F., De Padova, V., & Zilli, I. (2011). Good and Bad Sleep in Childhood: A Questionnaire Survey amongst School Children in Southern Italy. Sleep Disorders, 2011, 1–8. 10.1155/2011/825981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox, J., Murray, C., & Warm, A. (2003). Conducting research using web-based questionnaires: Practical, methodological, and ethical considerations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 6(2), 167-180. 10.1080/13645570210142883. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen, K., Rhodes, J., Reddy, R., & Way, N. (2004). Sleepless in Chicago: Tracking the Efects of Adolescent Sleep Loss During the Middle School Years. Child Development, 75(1), 84–95. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, C., Lehman, E., Hicks, S., & Novick, M. B. (2017). Bedtime Use of Technology and Associated Sleep Problems in Children. Global Pediatric Health, 4, 2333794X1773697. 10.1177/2333794x17736972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giannotti, F., Cortesi, F., Sebastiani, T., & Vagnoni, C. (2005). Sleeping habits in Italian children and adolescents. Sleep and Biological Rhythms, 3(1), 15-21. 10.1111/j.1479-8425.2005.00155.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, W. A., & Keller, M. A. (2007). Parent-infant co-sleeping: why the interest and concern? Infant and Child Development, 16(4), 331–339. 10.1002/icd.523. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, A. M., Van der Ende, J., Willis, T. A., & Verhulst, F. C. (2008). Parent-reported sleep problems during development and self-reported anxiety/depression, attention problems, and aggressive behavior later in life. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 162, 330–335. 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, R., Michaelsen, S., Bergmame, L., Frenette, S., Bruni, O., Fontil, L., & Carrier, J. (2012). Short sleep duration is associated with teacher-reported inattention and cognitive problems in healthy school-aged children. Nature and Science of Sleep, 4, 33. 10.2147/NSS.S24607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, W. A., & Nethery, E. (2019) What does sleep hygiene have to offer children’s sleep problems?. Paediatric Respiratory Reviews, 31, 64-74. 10.1016/j.prrv.2018.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertenstein, E., Feige, B., Gmeiner, T., Kienzler, C., Spiegelhalder, K., Johann, A., Jansson-Fröjmark, M., Palagini, L., Rücker, G., Riemann, D., & Baglioni, C. (2019). Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 43, 96–105. 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirshkowitz, M., Whiton, K., Albert, S. M., Alessi, C., Bruni, O., DonCarlos, L., Hazen, N., Herman, J., Katz, E. S., Kheirandish-Gozal, L., Neubauer, D. N., O’Donnell, A. E., Ohayon, M., Peever, J., Rawding, R., Sachdeva, R. C., Setters, B., Vitiello, M. V., Ware, J. C., & Adams Hillard, P. J. (2015). National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health, 1(1), 40–43. 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hysing M, Hysing, M., Sivertsen, B., Garthus-Niegel, S., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2016). Pediatric sleep problems and social-emotional problems. A population-based study. Infant Behavior and Development, 42, 111-118. 10.1016/j.infbeh.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczor, M., & Skalski, M. ł. (2016). Prevalence and consequences of insomnia in pediatric population. Psychiatria Polska, 50(3), 555–569. 10.12740/pp/61226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam P, Lam, P., Hiscock, H., & Wake, M. (2003). Outcomes of infant sleep problems: a longitudinal study of sleep, behavior, and maternal well-being. Pediatrics, 111(3), e203-e207. 10.1542/peds.111.3.e203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti, D., Fontanesi, L., Mazza, C., Di Giandomenico, S., Roma, P., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2020). Parenting-related exhaustion during the italian COVID-19 lockdown. Journal of pediatric psychology, 45(10), 1114-1123. 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell, J. A., Owens, J. A., & Carskadon, M. A. (1999). Developmental Features of Sleep. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 8(4), 695–725. 10.1016/s1056-4993(18)30149-4.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell, J. A., Meltzer, L. J., Carskadon, M. A., & Chervin, R. D. (2009). Developmental aspects of sleep hygiene: Findings from the 2004 National Sleep Foundation Sleep in America Poll. Sleep Medicine, 10(7), 771–779. 10.1016/j.sleep.2008.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindell, J. A., & Owens, J. A. (2015). A clinical guide to pediatric sleep: diagnosis and management of sleep problems. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Mindell, J. A., Leichman, E. S., DuMond, C., & Sadeh, A. (2017). Sleep and social-emotional development in infants and toddlers. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 46(2), 236-246. 10.1080/15374416.2016.1188701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin, C. M., Rodrigue, S., & Ivers, H. (2003). Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosomatic Medicine, 65(2), 259-267. 10.1016/s1098-3597(03)90037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratori, P., & Ciacchini, R. (2020). Children and the COV-ID-19 transition: psychological reflections and suggestions on adapting to the emergency. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 131-134. 10.36131/CN20200219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muratori, P., Menicucci, D., Lai, E., Battaglia, F., Bontempelli, L., Chericoni, N., & Gemignani, A. (2019). Linking Sleep to Externalizing Behavioral Difficulties: A Longitudinal Psychometric Survey in a Cohort of Italian School-Age Children. The journal of Primary Prevention, 40(2), 231-241. 10.1007/s10935-019-00547-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucci, F., Mucci, N., & Diolaiuti, F. (2020). Lockdown and isolation: Psychological aspects of COVID-19 pandemic in the general population. Clinical Neuropsychiatry: Journal of Treatment Evaluation, 17(2), 63-64. 10.36131/CN20200205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens, J. (2008). Classification and Epidemiology of Childhood Sleep Disorders. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 35(3), 533–546. 10.1016/j.pop.2008.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens, J. A., & Mindell, J. A. (2011). Pediatric Insomnia. Pediatric Clinics of North America, 58(3), 555–569. 10.1016/j.pcl.2011.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer, C. A., & Alfano, C. A. (2017). Sleep and emotion regulation: An organizing, integrative review. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 31, 6–16. 10.1016/j.smrv.2015.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengo, M. F., Won, C. H., & Bourjeily, G. (2018). Sleep in Women Across the Life Span. Chest, 154(1), 196–206. 10.1016/j.chest.2018.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlarb, A. A., Velten-Schurian, K., Poets, C. F., & Hautzinger, M. (2011). First effects of a multicomponent treatment for sleep disorders in children. Nature and Science of Sleep, 3, 1. 10.2147/NSS.S15254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn, B. E., Elmore-Staton, L., Shin, N., & El-Sheikh, M. (2015). Sleep as a support for social competence, peer relations, and cognitive functioning in preschool children. Behavioral Sleep Medicine, 13(2), 92-106. 10.1080/15402002.2013.845778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, E. J., Banks, S., Coates, A. M., & Kohler, M. J. (2017). The Relationship Between Caffeine, Sleep, and Behavior in Children. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 13(04), 533–543. 10.5664/jcsm.6536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]