Structured Abstract:

Purpose of review:

Utilization of basophil activation in the diagnosis and monitoring of food allergy has gained increasing recognition. An ex vivo functional assay, basophil activation reflects clinical reactivity, thereby providing clinically relevant insights. Moreover, as a biomarker of reactivity and tolerance, basophil activation testing (BAT) may provide a useful tool for management of food allergies. Despite its utility, significant limitations of BAT have prevented widespread use. Addressing these limitations will increase the future application and adoption of BAT in food allergy.

Recent Findings:

A number of clinical trials in the past few years have demonstrated the use of BAT in the diagnosis and treatment of food allergy. Specifically, BAT has been found to be a biomarker of tolerance.

Summary:

Basophil activation testing is an effective biomarker for diagnosis and monitoring of food allergy.

Keywords: Food allergy, basophil activation test

Introduction

Biology of BAT

An innate granulocyte with a surface covered by IgE, basophils play an important biological role at the juncture between innate and adaptive immunity (1). On a more basic level, however, as a rare circulating allergic effector cell, basophils can also serve as an effective surrogate biomarker of IgE-mediated allergic diseases. The high affinity IgE receptor (FcERI), expressed on the surface and mostly bound by IgE, undergoes cross-linking to triggers a signalling cascade, resulting in basophil activation, release of pro-inflammatory mediators and upregulation of activation markers. Non IgE-mediated pathways of basophil activation can act through other effector molecules, to again result in similar upregulation of activation markers.

Factors both intrinsic, or internal, and extrinsic modulate basophil activation. Intrinsic factors include signalling pathways and inhibitory cross-regulation. Extrinsic factors, however, make basophil activation a particularly useful biomarker. These extrinsic factors reflect the circulating antibody milleu. IgE-mediated basophil activation is regulated by multiple characteristics of circulating antibody. The quantity of total circulating IgE, quantity of specific IgE, specific to total IgE ratio, specific IgE affinity, specific IgE diversity, specific IgE clonality, all influence basophil activation in defined and calculable ways(2). For example, surface expression of FcERI on basophils is driven by total circulating IgE, with rapid down-regulation of FcERI when IgE is removed from circulation(3). Furthermore, specific IgE cross-linking on the surface of basophils is driven by allergen-IgE interactions. Cross-linking requires more than one allergen-IgE interaction to take place, and the higher the diversity and clonality of IgE, the increase in likelihood of crosslinking(2). Similarly, higher affinity IgE will have more effective allergen-IgE interactions resulting basophil degranulation(2). Finally, allergen-specific IgG can both prevent these allergen-IgE interactions (4, 5) and activate inhibitory surface FcgRIIA and FcgRIIB receptors(6, 7), to suppress basophil activation. Basophils, in essence, can integrate the complexities of the allergen-specific antibody responses in IgE-mediated allergy to reflect the allergic state within individuals and provide an effective biomarker of allergy.

BAT Methodology

Discovery of CD63

In 1991, Edward Knol and colleagues discovered CD63 as a marker of basophil activation. Using a monoclonal antibody that recognized a tetraspanin known as lysosomal-associated membrane glycoprotein-3 (LAMP-3), they found surface upregulation of CD63 correlated with histamine release in both IgE-mediated and non-IgE mediated basophil activation(8). During degranulation, fusion of cytoplasmic vesicles with the plasma membrane results in CD63 surface translocation as well as the successive release of inflammatory mediators, such as histamine(8). This landmark discovery allowed the development of our modern-day basophil activation test (BAT), which relies on flow cytometry for evaluation of CD63 upregulation to quantify basophil activation, in lieu of more technically challenging measures of basophil degranulation. Since then, BAT has been applied to a wide range of applications within allergy,(9) from drug allergy(10) to food allergy, as reviewed here.

Basophil activation test (BAT) assay

Ex vivo BAT utilizes peripheral blood and stimulates basophils with increasing doses of allergens, to generate an allergen dose-response curve, which has been characterized as a bell-shaped curve(11). Using flow cytometry, basophil can be identified based on expression of specific cell surface markers, including IL-3Rα (CD123), CD193, CD203c, CD294, and/or FcERI. Basophils are identified primarily on the basis of low side scatter (SSClow) CD193+, SSClow CD193+CD203c+, SSClow CD203c+ CD123+HLA-DR−, SSClow CD123+HLA-DR-, SSClow CD203c+ or SSClow CD193+CD123+ (12).

Markers of activation include CD63 and CD203c, the basophil-specific ectoenzyme E-NPP3(13), which have different kinetics. We will focus on CD63 in this review, which is bimodally upregulated in basophil degranulation. The percentage of CD63hi basophils (%CD63) quantifies basophil activation. The CD63 threshold for activated basophils can be determined at the 97.5th percentile of the CD63 distribution in the unstimulated control condition (14).

In addition, using the percentage of CD63hi basophils, two important parameters of basophil activation are derived from the allergen dose-response curve: basophil reactivity and basophil sensitivity(15). Basophil reactivity has been quantified both as the maximum percentage of CD63hi basophils in the dose-response curve (CD63max), or area under the dose-response curve (AUC). Basophil sensitivity has been characterized as the ED50 of the dose-response curve, or inversely as the basophil threshold sensitivity (CD-sens)(16).

However, BAT assays have several limitations. Due to the relatively shorter lifespan of basophils, this functional assay requires completion within a short time frame(17), though some studies have suggested basophil activation can be performed even 1 day post-collection after ambient transport (18). BAT assays are labor intensive, require flow cytometry or mass cytometry, specific expertise, and can have variability in protocols and interpretation. Furthermore, the frequency of basophil non-responders ranges up to 20% in some published studies(19). Finally, commonly used medications, including steroids, can decrease the number of circulating basophils, leading to less reproducible BAT results. These challenges have hampered clinical application of this useful functional assay.

BAT in Diagnostics

Like other diagnostic tests, BAT has been studied as an alternative to the gold standard diagnostic procedure, the oral food challenge (OFC), which is labor intensive, costly, and can raise patient safety concerns. In comparison, the BAT is minimally invasive in its use of less than 1 mL of fresh blood.

Both whole allergen extract and component allergens have been used in diagnostic studies of BAT. In peanut allergy, for instance, BAT using whole peanut extract effectively distinguished children with peanut allergy from those who were sensitized but tolerant, even in individuals with similar IgE levels(20). In practical terms, BAT use could result in a 67% reduction in the need for a diagnostic OFC. Focus on the immunodominant component allergen has also been useful in peanut allergy. BAT with the immunodominant allergy Ara h 2 and a highly similar component Ara h 6 has also been found to be effective in discriminating between allergy and tolerance(21, 22).

Not only can BAT aid in the diagnosis of peanut allergy but may also inform the severity of their peanut allergy(23). Clinical severity of reactions on a standardized oral food challenge correlated with basophil reactivity with peanut-stimulated BAT. On the other hand, the threshold of peanut dose inducing the reaction correlated to basophil sensitivity. These parameters of the dose-response curve, therefore, can provide critical information about an individual patient’s clinical reaction to an allergen.

As milk allergy is frequently outgrown, longitudinal assessment to select an optimal time for milk re-introduction is an essential aspect of management. Indeed, BAT reduced the need for a food challenge in children suspected of IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy (24). Interestingly Ford and colleagues showed that CD63 ratio was significantly higher among patients with milk allergy who reacted to baked milk than among those who tolerated it(25). Rubio, et.al. proposed the use of milk-stimulated BAT in addition to skin prick testing and serum specific IgE assessment to similarly discriminate between tolerant and allergic children(26).

BAT in Monitoring Clinical Outcomes in Immunotherapy

The effectiveness of BAT in aiding diagnosis of food allergy also extends to monitoring of clinical responses to oral immunotherapy. Food allergen immunotherapy to many allergens, including peanut (27–31) and egg(32), have robustly demonstrated longitudinal modulation of basophil activation. Moreover, BAT suppression occurs in all forms of immunotherapy, including oral,(27–31) sublingual,(33–35) and epicutaneous(36) immunotherapy, to a lesser extent. BAT suppression is most pronounced with active allergen-updosing and decreases slightly during regular allergen ingestion(4, 37). The reproducible recurrence of BAT suppression across multiple forms of immunotherapy increases the utility of BAT for clinical monitoring during immunotherapy.

Moreover, basophil suppression has been identified as a biomarker of tolerance in oral immunotherapy (OIT)(4, 38, 39). Distinct parameters of the allergen dose-response curve inform clinical responses to immunotherapy. Basophil reactivity, quantified as the dose-response AUC, mirrors clinical reactivity in a study of peanut oral immunotherapy (OIT), identifying individuals who lost allergenic tolerance post-avoidance after completion of a year of OIT(4). On the other hand, basophil sensitivity, quantified as ED50 to the immunodominant Ara h 2 correlated to sustained unresponsiveness after OIT. In fact, the early change in basophil sensitivity to Ara h 2 within 3 months of OIT predicted future tolerance. Basophil sensitivity to whole peanut extract did not predict tolerance as effectively, suggesting that component allergen-based testing may be superior biomarkers in certain food allergens(4). Similarly, basophil suppression and decreases in specific IgE together have been shown to correlate with tolerance in peanut OIT(38, 39).

Increasingly, clinical trials using adjunctive therapy with biologics targeting Th2 inflammation along with peanut OIT are underway. Omalizumab, a recombinant humanized anti-IgE antibody which reduces basophil reactivity, has been studied as an adjunctive therapy with oral immunotherapy to several food allergens. In a clinical trial where subjects treated with milk OIT underwent a randomized, placebo-controlled trial with omalizumab, high baseline basophil reactivity to milk was identified as a potential biomarker for individuals most likely to benefit from omalizumab therapy(40). Basophil sensitivity has also been used successfully as a monitoring tool in an adaptive clinical trial using omalizumab in peanut OIT to decrease adverse events(41). In summary, baseline basophil reactivity and longitudinal basophil sensitivity are useful biomarkers in food OIT.

Indirect BAT

Given the time-sensitive nature of ex vivo BAT, an alternative test which has been termed indirect BAT has been increasingly utilized. In this assay, basophils from non-allergic donors are stripped of their endogenous surface IgE using lactic acid stripping, followed by loading of IgE by incubating the stripped basophils in serum from allergic donors. The allergen IgE loaded basophils can then be stimulated by allergens, and assayed by flow cytometry for basophil degranulation using activation markers CD63 and CD203c. This strategy has been successfully employed to interrogate the influence of allergen-specific antibodies on basophil activation in in monitoring during OIT for food allergy(4, 6, 42).

Barriers to adopting BAT

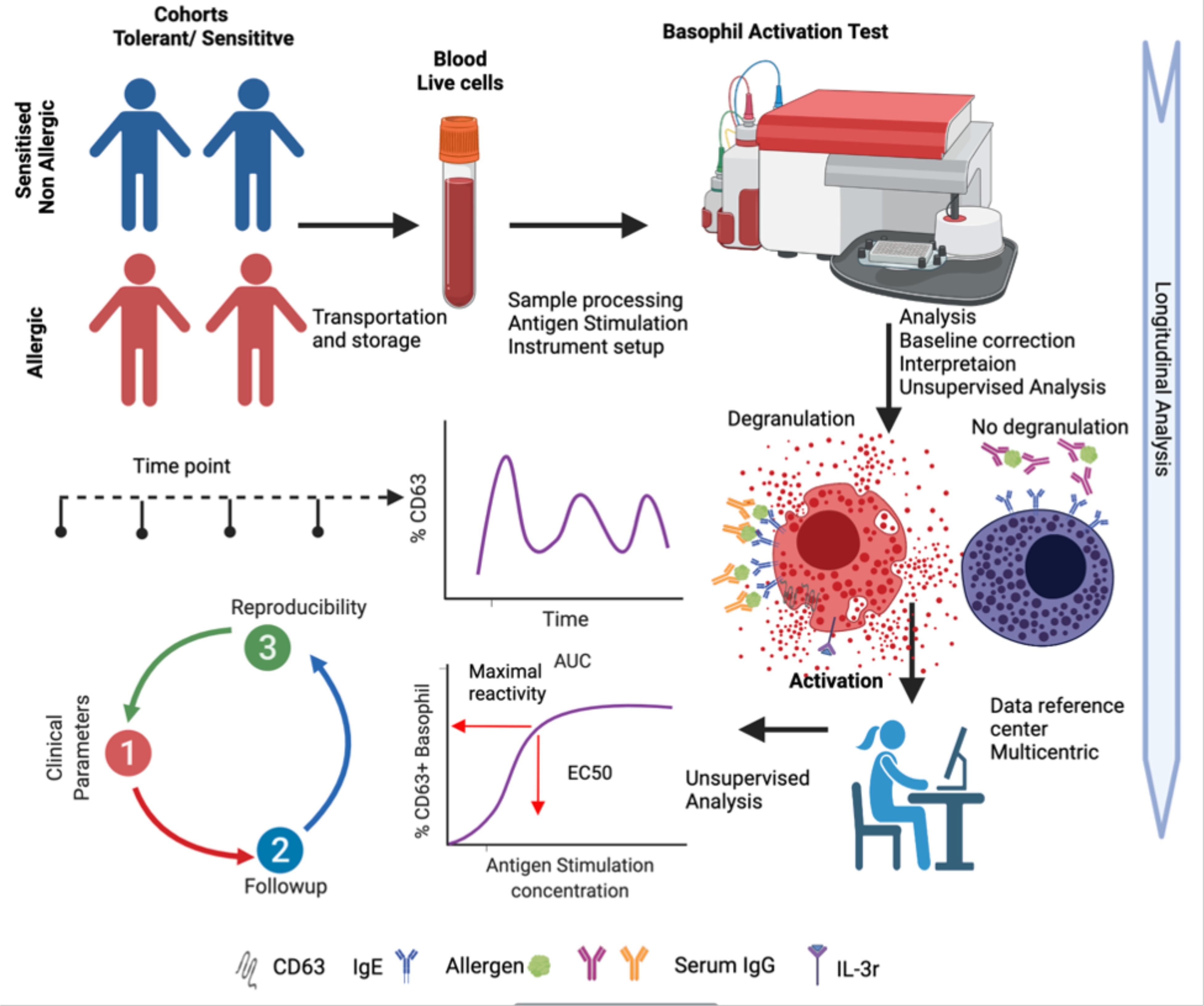

The clinical utility of BAT has significant promise for the diagnosis and management of IgE-mediated food allergies(9). However, the performance of BAT can be influenced by many factors, related to patient populations, study design, laboratory techniques, and analytical techniques. Clinical implementation, and regulatory approval, therefore, requires significant strides in standardization of application, BAT laboratory assays, and interpretation (Fig. 1). Technical aspects of BAT, including anticoagulants used in blood collection, presence of IL-3 in media, stimulation times, allergens (whole or components), antibodies used for staining, erythrocyte cell lysis, and additional washing steps are all variables that can significantly impact measurements of basophil activation. Furthermore, flow cytometry-based interpretation can have variability, from subjective gating to statistical interpretation of the dose-response curve. Application of an automated gating strategy for flow cytometric basophil activation tests may provide transparent, reproducible, and reliable analysis, but are still in development(43). These methods have a distinct advantage, in that they can be used to increase throughput, and therefore clinical application. Finally, positioning the BAT in the context of other clinical and laboratory data including serum allergen-specific IgE and skin prick testing, to maximize its utility in clinical decision making is critical to increasing its utility for practioners. While significant strides in incorporating BAT in clinical decision making have been made, widespread application across different populations requires additional study(44).

Fig 1. Clinical Utility of Basophil Activation Testing (BAT).

Peripheral blood obtained from patients is longitudinally monitored using BAT. Distinct parameters are monitored as predictors of reactivity and tolerance. Standardization of BAT promotes multicentric care and collaboration.

Conclusions

BAT is a surrogate in vitro marker of clinical reactivity and tolerance. Correlation of basophil suppression with clinical tolerance after immunotherapy highlights its utility as a monitoring tool for the value of peanut immunotherapy(9) without subjecting patients to repeat oral challenges. Basophil sensitivity and AUC can not only better inform clinical outcomes than bulk measurements of allergen-specific antibodies but might also provide a surrogate functional measure of the induction of protective antigen-specific antibodies. However, the clinical application of BAT continues to be limited by its technical demands, need for standardized analytical approaches, and study in the context of other measures of allergic sensitization. Concerted efforts to implement standards in this field will promote our ability to more fully realize the potential of BAT as a clinically useful biomarker of allergy and tolerance.

Key points.

BAT can provide mechanistic insights into the biology of food allergy.

BAT is useful biomarker and a clinical tool for management of food allergy.

Standardization will increase applicability of BAT in clinical food allergy management.

Acknowledgments

Financial support and sponsorship

SUP is supported through the following grants: NIH NIAID R01AI155630, R21AI159732.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

- 1.Shah H, Eisenbarth S, Tormey CA, Siddon AJ. Behind the scenes with basophils: an emerging therapeutic target. Immunotherapy Advances. 2021;1(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christensen LH, Holm J, Lund G, Riise E, Lund K. Several distinct properties of the IgE repertoire determine effector cell degranulation in response to allergen challenge. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2008;122(2):298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanase Y, Matsuo Y, Kawaguchi T, Ishii K, Tanaka A, Iwamoto K, et al. Activation of Human Peripheral Basophils in Response to High IgE Antibody Concentrations without Antigens. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;20(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patil SU, Steinbrecher J, Calatroni A, Smith N, Ma A, Ruiter B, et al. Early decrease in basophil sensitivity to Ara h 2 precedes sustained unresponsiveness after peanut oral immunotherapy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2019;144(5):1310–9.e4. ** Demonstrated BAT as a predictive biomarker of tolerance in oral immunotherapy.

- 5. Santos AF, James LK, Kwok M, McKendry RT, Anagnostou K, Clark AT, et al. Peanut oral immunotherapy induces blocking antibodies but does not change the functional characteristics of peanut-specific IgE. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2020;145(1):440–3 e5. ** Demonstrated the utility of BAT as a test of the induction of blocking antibodies in oral immunotherapy.

- 6.Burton OT, Logsdon SL, Zhou JS, Medina-Tamayo J, Abdel-Gadir A, Noval Rivas M, et al. Oral immunotherapy induces IgG antibodies that act through FcgammaRIIb to suppress IgE-mediated hypersensitivity. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014;134(6):1310–7 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burton OT, Tamayo JM, Stranks AJ, Koleoglou KJ, Oettgen HC. Allergen-specific IgG antibody signaling through FcgammaRIIb promotes food tolerance. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2018;141(1):189–201 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knol EF, Mul FP, Jansen H, Calafat J, Roos D. Monitoring human basophil activation via CD63 monoclonal antibody 435. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1991;88(3 Pt 1):328–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann HJ, Santos AF, Mayorga C, Nopp A, Eberlein B, Ferrer M, et al. The clinical utility of basophil activation testing in diagnosis and monitoring of allergic disease. Allergy. 2015;70(11):1393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Giavina-Bianchi P, Galvao VR, Picard M, Caiado J, Castells MC. Basophil Activation Test is a Relevant Biomarker of the Outcome of Rapid Desensitization in Platinum Compounds-Allergy. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice. 2017;5(3):728–36. ** Demonstrated basophil activation as a biomarker of desensitization in drug allergy.

- 11.MacGlashan DW Jr. Basophil activation testing. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2013;132(4):777–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos AF, Alpan O, Hoffmann HJ. Basophil activation test: Mechanisms and considerations for use in clinical trials and clinical practice. Allergy. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buhring HJ, Streble A, Valent P. The basophil-specific ectoenzyme E-NPP3 (CD203c) as a marker for cell activation and allergy diagnosis. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;133(4):317–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.P M, N A, M C, E S, S A, E D, et al. Building confidence in the basophil activation test: standardization and external quality assurance - an EAACI task force.: Allergy; 2020. p. 115–6. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patil SU, Shreffler WG. Immunology in the Clinic Review Series; focus on allergies: basophils as biomarkers for assessing immune modulation. Clin Exp Immunol. 2012;167(1):59–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dahlen B, Nopp A, Johansson SG, Eduards M, Skedinger M, Adedoyin J. Basophil allergen threshold sensitivity, CD-sens, is a measure of allergen sensitivity in asthma. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2011;41(8):1091–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukai K, Gaudenzio N, Gupta S, Vivanco N, Bendall SC, Maecker HT, et al. Assessing basophil activation by using flow cytometry and mass cytometry in blood stored 24 hours before analysis. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2017;139(3):889–99.e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim T, Yu J, Li H, Scarupa M, Wasserman RL, Economides A, et al. Validation of inducible basophil biomarkers: Time, temperature and transportation. Cytometry Part B, Clinical cytometry. 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nguyen KL, Gillis S, MacGlashan DW Jr. A comparative study of releasing and nonreleasing human basophils: nonreleasing basophils lack an early component of the signal transduction pathway that follows IgE cross-linking. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 1990;85(6):1020–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santos AF, Douiri A, Bécares N, Wu SY, Stephens A, Radulovic S, et al. Basophil activation test discriminates between allergy and tolerance in peanut-sensitized children. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014;134(3):645–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glaumann S, Nopp A, Johansson SG, Rudengren M, Borres MP, Nilsson C. Basophil allergen threshold sensitivity, CD-sens, IgE-sensitization and DBPCFC in peanut-sensitized children. Allergy. 2012;67(2):242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Erp FC, Knol EF, Pontoppidan B, Meijer Y, van der Ent CK, Knulst AC. The IgE and basophil responses to Ara h 2 and Ara h 6 are good predictors of peanut allergy in children. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2017;139(1):358–60 e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Santos AF, Du Toit G, Douiri A, Radulovic S, Stephens A, Turcanu V, et al. Distinct parameters of the basophil activation test reflect the severity and threshold of allergic reactions to peanut. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;135(1):179–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruinemans-Koerts J, Schmidt-Hieltjes Y, Jansen A, Savelkoul HFJ, Plaisier A, van Setten P. The Basophil Activation Test reduces the need for a food challenge test in children suspected of IgE-mediated cow’s milk allergy. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2019;49(3):350–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.. Ford LS, Bloom KA, Nowak-Węgrzyn AH, Shreffler WG, Masilamani M, Sampson HA. Basophil reactivity, wheal size, and immunoglobulin levels distinguish degrees of cow’s milk tolerance. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2013;131(1):180–6.e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rubio A, Vivinus-Nébot M, Bourrier T, Saggio B, Albertini M, Bernard A. Benefit of the basophil activation test in deciding when to reintroduce cow’s milk in allergic children. Allergy. 2011;66(1):92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jones SM, Pons L, Roberts JL, Scurlock AM, Perry TT, Kulis M, et al. Clinical efficacy and immune regulation with peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(2):292–300, e1–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Patil SU, Steinbrecher J, Calatroni A, Smith N, Ma A, Ruiter B, et al. Early decrease in basophil sensitivity to Ara h 2 precedes sustained unresponsiveness after peanut oral immunotherapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(5):1310–9 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thyagarajan A, Jones SM, Calatroni A, Pons L, Kulis M, Woo CS, et al. Evidence of pathway-specific basophil anergy induced by peanut oral immunotherapy in peanut-allergic children. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2012;42(8):1197–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varshney P, Jones SM, Scurlock AM, Perry TT, Kemper A, Steele P, et al. A randomized controlled study of peanut oral immunotherapy: clinical desensitization and modulation of the allergic response. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2011;127(3):654–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vickery BP, Scurlock AM, Kulis M, Steele PH, Kamilaris J, Berglund JP, et al. Sustained unresponsiveness to peanut in subjects who have completed peanut oral immunotherapy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2014;133(2):468–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vila L, Moreno A, Gamboa PM, Martinez-Aranguren R, Sanz ML. Decrease in antigen-specific CD63 basophil expression is associated with the development of tolerance to egg by SOTI in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2013;24(5):463–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim EH, Bird JA, Kulis M, Laubach S, Pons L, Shreffler W, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: clinical and immunologic evidence of desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127(3):640–6 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim EH, Yang L, Ye P, Guo R, Li Q, Kulis MD, et al. Long-term sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy in children: Clinical and immunologic evidence of desensitization. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;144(5):1320–6 e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burks AW, Wood RA, Jones SM, Sicherer SH, Fleischer DM, Scurlock AM, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for peanut allergy: Long-term follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2015;135(5):1240–8.e1–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones SM, Sicherer SH, Burks AW, Leung DY, Lindblad RW, Dawson P, et al. Epicutaneous immunotherapy for the treatment of peanut allergy in children and young adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(4):1242–52 e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gorelik M, Narisety SD, Guerrerio AL, Chichester KL, Keet CA, Bieneman AP, et al. Suppression of the immunologic response to peanut during immunotherapy is often transient. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(5):1283–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chinthrajah RS, Purington N, Andorf S, Long A, O’Laughlin KL, Lyu SC, et al. Sustained outcomes in oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy (POISED study): a large, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 study. Lancet. 2019;394(10207):1437–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsai M, Mukai K, Chinthrajah RS, Nadeau KC, Galli SJ. Sustained successful peanut oral immunotherapy associated with low basophil activation and peanut-specific IgE. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2020;145(3):885–96 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frischmeyer-Guerrerio PA, Masilamani M, Gu W, Brittain E, Wood R, Kim J, et al. Mechanistic correlates of clinical responses to omalizumab in the setting of oral immunotherapy for milk allergy. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2017;140(4):1043–53 e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brandstrom J, Vetander M, Sundqvist AC, Lilja G, Johansson SGO, Melen E, et al. Individually dosed omalizumab facilitates peanut oral immunotherapy in peanut allergic adolescents. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2019;49(10):1328–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ocmant A, Mulier S, Hanssens L, Goldman M, Casimir G, Mascart F, et al. Basophil activation tests for the diagnosis of food allergy in children. Clinical and experimental allergy : journal of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2009;39(8):1234–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patil SU, Calatroni A, Schneider M, Steinbrecher J, Smith N, Washburn C, et al. Data-driven programmatic approach to analysis of basophil activation tests. Cytometry Part B, Clinical cytometry. 2018;94(4):667–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chinthrajah RS, Purington N, Andorf S, Rosa JS, Mukai K, Hamilton R, et al. Development of a tool predicting severity of allergic reaction during peanut challenge. Annals of allergy, asthma & immunology : official publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. 2018;121(1):69–76.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]