Abstract

Organoids are miniature models of organs to recapitulate spatiotemporal cellular organization and tissue functionality. The production of organoids has revolutionized the field of developmental biology, providing the possibility to study and guide human development and diseases in a dish. More recently, novel biomaterial-based culture systems demonstrated the feasibility and versatility to engineer and produce the organoids in a consistent and reproducible manner. By engineering proper tissue microenvironment, functional organoids have been able to exhibit spatial-distinct tissue patterning and morphogenesis. This review will focus on enabling technologies in the field of organoid engineering, including the control of biochemical and biophysical cues via hydrogels, as well as size and geometry control via microwell and microfabrication techniques. In addition, this review discusses the enhancement of organoid systems for therapeutic applications using biofabrication and organoid-on-chip platforms, which facilitate the assembly of complex organoid systems for in vitro modeling of development and diseases.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Organoids are a class of engineered three-dimensional (3D) tissues that manifest the biological characteristics similar to their in vivo counterparts. Traditional 2D cultures represent simple and efficient culture techniques, but do not represent the natural 3D feature and biological complexity of organs and tissues. 3D models, organoids in particular, provide numerous opportunities to engineer culture systems that bridge the gap between the limitations of 2D tissue culture and in vivo organisms of whole animal or human subjects. Though the term “organoid” has been applied to a wide range of in vitro tissue culture systems, many publications have generalized organoids into the entirety of 3D tissue models. Over the past decade, the concept of organoids has been refined to consist of multi-cellular tissues that develop from stem cells or progenitor cells, which self-organize into spatially restricted lineages, similar to in vivo developmental events [1,2]. In comparison with stem cell-derived organoids, cancer organoids are generally generated from cancerous cell lines or derived from patient tumor biopsies. Though both these organoids systems are widely used for the purpose of disease modeling, cancer organoids are specifically used for translational cancer research, whereas stem cell-derived organoids are generally used to model tissue pathology and developmental defects [3–5]. The approaches to engineer stem cell-based organoid systems have to take into consideration of the differentiation and self-organization potentials of differentiating cells [6,7], which are highly dependent on the cell state and their current developmental stage. Stem cells are an invaluable tool for organoid engineering because of their ability to differentiate and organize within an organ-specific niche. In addition, stem cell biology can be viewed as a parallel to developmental biology [8], which can be integrated with tissue engineering fundamentals to mimic organ formation and functionality in vitro. By controlling the stem cell microenvironment, it is possible to provide a better understanding of how cell behavior and differentiation can be directed along specific tissue lineages.

The earliest intestinal organoid models involved primary intestinal stem cells [9], which are multipotent adult stem cells pre-programmed to follow a specific tissue lineage based on their tissue source niches. The organoids generated from primary tissue stem cells were better for recapitulating the homeostatic conditions and regenerative processes of the corresponding tissues, resulting in cellular compositions and structures closer to that of adult tissues [2,6]. In contrast, organoids are also commonly derived from pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), such as human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) and induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs). Since PSCs are not tissue specific, they heavily rely on the supply of signaling factors at the appropriate sequential time point in order to achieve the tissue lineage of interest. PSCs allow flexibility in controlling cell differentiation into primary germ layers, which further allows coordinated differentiation of multiple cell types. This often results in the co-differentiation of several cell types that occur during multi-organ development, as seen in numerous cases of gut, liver, and lung organoids [10–13]. Furthermore, this co-emergent tissue development into multi-lineage organoids can exploit cellular communication networks, which allows us to better understand tissue-tissue interactions that facilitate spatial organization and tissue maturation.

Design principles of organoid engineering

Generation of tissue-specific organoids is built upon the biological principles of organ development, wherein stem cells are regulated to differentiate and self-assemble into functional tissues and organs. Recapitulating these characteristics to optimize stem cell organoid generation requires appropriate external stimuli from cell and tissue microenvironment. The cell fate decisions and tissue organization that drive organogenesis are facilitated by a combination of biochemical factors and biophysical restraints from extracellular environment and surrounding cells [14]. For instance, in the earliest stages of embryogenesis, the fertilized embryo rapidly cleaves into multiple cells within a constrained space until the cells reorganize to form the embryonic cavities. During this time, a single fertilized oocyte divides into multiple cells with little change in overall size. As a result, the cells become smaller and compacted until the blastocyst forms. Furthermore, cell polarization is facilitated by paracrine signaling and mechanical forces exerted from neighboring cells, which eventually leads to the formation of the three primary germ layers and subsequent tissue patterning [15]. These developmental principles are the foundation of organoid engineering designs, which primarily involve the control of cell aggregate size and appropriately timed morphogen input.

By harnessing principles of tissue and organ development for organoid engineering, research has demonstrated the advancement of highly sophisticated systems to generate, engineer and characterize the organoids for a wide range of applications, including disease modeling, drug screening, and tissue repair. The design principles of these engineering systems are formulated to optimize the generation of organoids depending on their in vivo organ counterparts. Regarding engineering designs, these advanced organoid systems can be classified into four major types: hydrogel-based technology, microfabrication-based technology, biofabrication in organoid assembly, and organoid-on-chip technology. In this review, we will discuss the design principles of these organoid systems and elaborate their applications in modeling the tissue development and disease pathogenesis. 3D hydrogel systems involve the formation and differentiation of cell aggregates and spheroids under suspension culture conditions. Microfabrication-based techniques rely on the control of cell colony to drive the assembly of 3D organoids from 2D culture. Biofabrication techniques can be used to build-up organoid complexity for scale-up and manufacturing applications. Organoid-on-chip platforms integrate organoids with organ-on-chip technologies to better model the biophysical and biochemical complexities in the body.

3D Hydrogels

Matrigel-based organoid systems

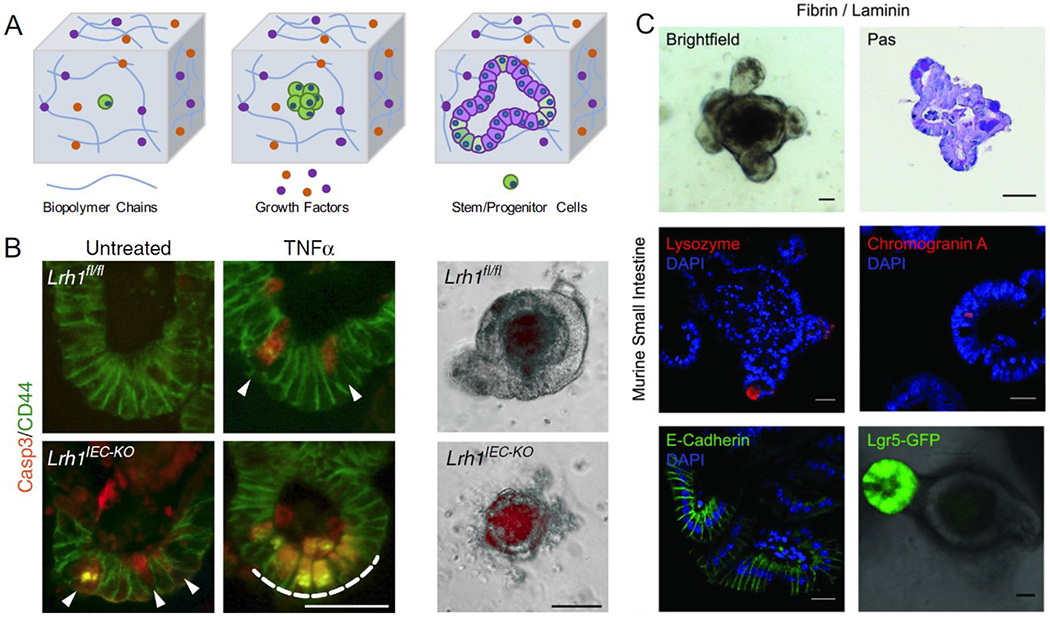

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a network of extracellular molecules that not only provide structural support, but also biochemical support to cells [16]. As a class of ECM, hydrogels, in particular, showed great compatibility to organoid generation, since the cells can be embedded in hydrogel matrices for 3D suspension and aggregation (Fig. 1A). One of the most commonly used hydrogels are basement membrane protein mixtures excreted from EHS mouse sarcoma cells, commercialized as Matrigel, which forms a gelatinous scaffold suitable for cell attachment, encapsulation, and proliferation [17]. Numerous organoids that have been developed to date are heavily relied on Matrigel-based scaffolds. As the first examples of organoids, mouse LGR5+ intestinal stem cells embedded in Matrigel ECM formed tissue structures with a monolayer of epithelial cells, luminal structures, and intestinal crypts [18]. Progenitor cells within the intestinal crypts proliferate and differentiate to form the epithelium composing the villus. This work demonstrated that the combination of cells grown within a Matrigel matrix supplemented with the appropriate growth medium was enough to permit single intestinal stem cells to form functional organoids.

Figure 1. Hydrogel-based organoid engineering.

A) Hydrogels for organoid engineering require the appropriate chemical compositions to generate the organoid of interest. These components include the appropriate type of biopolymer, morphogens, growth factors and cells. B) Matrigel-based hydrogel has been used as the gold standard culture system for intestinal organoids, allowing for modeling of intestinal buds and crypts hallmark to intestinal tissue and further modeling of inflammatory bowel disease (Reproduced from J.R. Bayrer et al. 2018). C) Hydrogels with defined compositions can be engineered to generate intestinal organoids with comparable phenotypes as organoids cultured in Matrigel, thus overcoming limitations of harvested basement membrane matrices (Reproduced from Broguiere et al. Copyright 2018 © John Wiley and Sons).

To this date, Matrigel-based intestinal organoid systems have been further optimized to promote tissue maturation [19], screen drug toxicity [20], and model various types of gut diseases [21]. Bayrer and colleagues generated gut organoids exhibiting pathology of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) using the crypt cells from LRH-1 knockout mice, as well as human crypt cells harvested from IBD patients [22] (Fig. 1B). These organoids exhibited increased apoptotic activity, as well as higher degrees of epithelial damage. Knockout organoids specifically exhibited an increase in Caspase 3 activity within the organoid crypts, illustrating the failure of epithelial barriers. Moreover, therapeutic applicability was demonstrated by showing that human LRH-1 could restore the epithelial integrity for knockout organoids. Through vector transduction, the knockout organoids expressing LRH-1 were able to rescue the inflammatory response of epithelial cells and maintain the cell viability. By embedding the intestinal spheroids with neural crest cells in the Matrigel, intestinal organoids were generated with a functional enteric nervous system [23]. This system was used to investigate cellular and molecular mechanisms of Hirschsprung’s disease with PHOX2B mutation, resulting in a congenital abnormality of missing nerve cells in the gut [24]. PHOX2B mutated organoids displayed a reduction in the expression of neural crest markers and poor development of smooth muscle, which are necessary for enteric contraction. Overall, these works demonstrate the clinical applicability of studying disease and molecular mechanisms involved thereof.

In addition to intestinal organoids, Matrigel has also proven to be valuable asset for brain/cerebral organoid development, which normally require a long culture time to reach biological and functional maturation. Early work by Lancaster and colleagues demonstrated that neural progenitor cells can be embedded in Matrigel droplets and differentiated into brain organoids that can be cultured for at least 10 months. The cerebral organoids exhibited outgrowth of neural buds that formed specific brain regions reminiscent of cerebral cortex, choroid plexus, retina and meninges. The generation of brain organoids based on Matrigel systems has been further advanced to more sophisticated models that can capture region-specific features of the human brain. For instance, cerebral organoids were developed to recapitulate guided cortical plate formation [25–27], as well as forebrain, midbrain and hypothalamic development [28,29], providing versatile in vitro platforms that can be used to reconstruct the brain complexity and model neurological diseases.

Matrigel droplets have become standardized for numerous brain organoid disease models. To model microcephaly, a birth defect caused by a CDK5RAP2 mutation, brain organoids were generated from patient specific hiPSCs [30]. The diseased organoids showed premature neuronal differentiation, leading to smaller neural tissues that are reminiscent of microcephaly. During the worldwide health emergency caused by the Zika epidemic, brain organoids gained considerable attention for modeling virus-induced microcephaly [28,31–33]. Viral exposure to the brain organoids showed that the viral infection induced the cell apoptosis and impaired the neural proliferation, resulting in a decrease in the brain volume, a signature characteristic of microcephaly. Forebrain organoids have also been applied to model lissencephaly, revealing significant defects in the progenitor cells, such as cell division timing and abnormal Wnt signaling [34,35]. The brain organoids modeling Alzheimer’s disease displayed hyperactive neuronal activity and decreased activity of inhibitory neurons, which supported current evidence of neurodegeneration mechanisms involved in this disease [36,37]. The midbrain organoids have been used to model Parkinson’s disease derived from patients or mutant hiPSC lines carrying the LRRK2-G2019S mutation. Defects in dopaminergic neurons were expressed as significantly reduced dendrite bifurcation points and decreased neural branching, indicating loss of neural complexity in the Parkinson’s disease systems [38–40]. These results illustrate an easily accessible model to study human brain development, disease progression, and potential therapeutics using tailored patient-specific organoids.

However, Matrigel, the derivative of murine cancer cell lines, has limitations that can hinder the progression in organoid development for many downstream applications and clinical translation. Furthermore, the constituents of Matrigel are not chemically defined, leading to compositional variability and inconsistency, especially for high-throughput and large-scale organoid production. To overcome this limitation, organoids have been produced using singular ECM components. For instance, collagen I-based scaffolds have been applied to generate endometrial [41], gastrointestinal tract [42] and various intestinal organoids [43]. In order to better recapitulate the complexity of native ECM, researchers have demonstrated different ways to incorporate additional biopolymer components, such as special-designed matrices composed of mixtures of collagen, laminin, fibrin etc. [44,45]. These approaches aim to not only recapitulate the natural cellular microenvironment, but also allow for better precision in controlling the biophysical and biochemical properties of biologically derived hydrogels.

Chemically defined hydrogels

To ensure consistency and reproducibility, the culture conditions for organoids should have defined compositions for future clinical applications. Over the last decade, organoid culture techniques have evolved from purely Matrigel based to biohybrid or fully synthetic hydrogels [46]. Although biohybrid and fully synthetic models do not have the same biological and bioactive complexity as Matrigel-like ECMs, they have proven to produce comparable organoids through appropriate functionalization and flexible tunability [44]. Bioinspired synthetic hydrogels have been developed to produce intestinal organoids based on naturally occurring biopolymers, such as alginate [47] and fibrin (Fig. 1C) [48]. Tunable recombinant protein ECMs, consisting of cell adhesive RGD sequences on an elastin-like polypeptides structural backbone, also produced intestinal organoids that were comparable to those grown in collagen [49]. The main advantage of this recombinant protein system was the tunable capability that cannot be achieved using collagen systems. The tunability of hydrogel mechanical properties permitted higher control over the enzymatic remodeling of the matrix to support the changes in organoid structure as it developed in culture. Gjorevski et al demonstrated modular hydrogel designs that can support different stages of intestinal organoid development using polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogel bases. PEG hydrogels are easily modifiable and enriched with key ECM biopolymers (fibronectin, laminin, collagen etc.). To enhance biological functionality, PEG was functionalized with RGD peptide, which supported both PSC expansion and organoid formation. In addition, the mechanical properties of PEG hydrogels can be altered, allowing for dynamic modulation of tissue microenvironment for organoid formation and differentiation. Specifically, RGD-functionalized stiffer matrices promoted initial intestinal stem cell expansion, while the transition into softer PEG-laminin hydrogels was required for intestinal organoid morphogenesis [44]. Not only these chemical-defined matrices can maintain organoid culture, they can also be modified to accommodate for dynamic microenvironmental changes that was required during different stages of organoid development.

Chemically defined hydrogels offer tunability to dynamically alter their mechanical properties, allowing for controlled differentiation and regulation of cellular activities [50]. PEG was functionalized with maleimide groups (PEG-4MAL) and crosslinked with additional functional peptides (RGD, AG73, GFOGER, RDG, and GPQ-W) which produced fully synthetic hydrogels with high bio-functionality and void of bioactive components isolated from animal and human sources. By tuning the mechanical properties to match with Matrigel, these hydrogels not only supported, but also controlled the differentiation and spatial patterning of human intestinal organoids. In addition, the PEG-4MAL hydrogels served as a suitable vehicle for in vivo intestinal organoid delivery. When transplanted to mice colon, the organoids were shown to be viable and able to heal colonic wounds, demonstrating superior biocompatibility and regenerative potentials. With the design flexibility of synthetic hydrogels, the compositional variability of ECM no longer hinders organoid scale-up production or clinical translation. Furthermore, the modular designs of these hydrogels offer tunability to control material properties for sustained culture, controllable differentiation and in vivo transplantation [51].

Hydrogels have provided very powerful ways to support the growth and differentiation of stem cells, enabling the creation of functional in vitro organoid models. Matrigel, in particular, has established the foundation of this field, demonstrating remarkable success in supporting the formation of a multitude of organoids that resembling corresponding in vivo counterparts. For instance, intestinal organoids, one of the earliest and most well-established organoid models, thrive in the natural ECM constituents of Matrigel, including the biopolymer macromolecules, growth factors and bioactive factors that are present in ECM-rich tissues. However, in order to advance these engineered organoids to the stage for human therapeutics, culture conditions can no longer rely on animal derived ECMs. Therefore, biocompatible hydrogels for organoid cultures have been transitioned to a fully defined and reproducible fashion, aiming to mimic the biomechanical and biochemical properties of natural ECMs. Tremendous progress has been made in synthetic hydrogels, which have illustrated versatility in regard to both hydrogel functionalization and tunability to meet the physiological needs of various organoid systems.

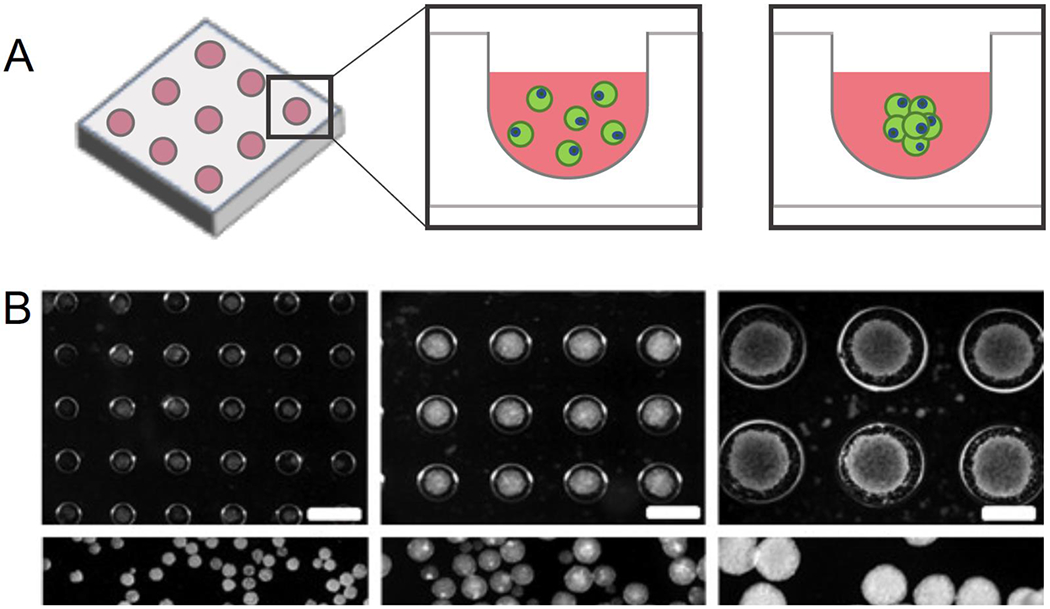

Hydrogel-based microwell technology for organoid size control

Hydrogels offer a physical support to embed, assemble and culture fully 3D organoids. These methods often result in spherical organoid structures, but often lack size control necessary for consistent and efficient organoid production. Thus, microwell-based cell culture systems have been widely applied to engineer these parameters across multiple organoid culture systems (Fig. 2A). Many studies, in fact, have indicated the important role of mechanotransduction in 3D tissues, which are correlated to the aggregate size density [6]. These include, but are not limited to embryoid bodies (Fig. 2B) [52], gastruloids [53] and brain [25]. One of the biggest advantages of microwell-based organoid engineering is the ability to control stem cell aggregate size, which has been demonstrated to be an important differentiation factor. Early studies showed that aggregate size of mouse ESCs significantly influenced the cardiomyogenic induction. Microwells were molded using PEG hydrogels in diameters ranging from 150-450 μm. Cardiogenic differentiation of microwell-controlled EBs showed greater efficiency in larger EB sizes, demonstrated as high expression of cardiomyogenic transcription factors Nkx2.5 and GATA4. In contrast, endothelial cell differentiation was enhanced in smaller EBs. This size-dependent fate specification was regulated by different noncanonical WNT signaling, in which WNT11 favored cardiogenic differentiation while WNT5a favored endothelial differentiation [54].

Figure 2. Microwells for organoid aggregate size control.

A) Microwells are a high-throughput method to consistently produce aggregates with controlled size for array-based scale-up processes. B) Controlling the aggregate size of mouse embryoid body using microwells was shown to significantly influence cardiogenesis and neurogenesis. (Reproduced from Choi et al. Copyright 2010 © Elsevier). C) A Milliwell system composed of a biomimetic hydrogel was able to differentiate retinal organoids with >90% efficiency. (Reproduced from Decembrini et al. 2020).

In the case of brain organoids, Lancaster et al. showed that that surface-to-volume ratio of the embryoid bodies influenced neuroectoderm development and organoid complexity [25]. To control the surface-to-volume ratio, microfilaments were synthesized from poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLGA) and individually placed into microwells to create a floating scaffold for EB attachment. The architecture of the microfilament scaffolds was manipulated to allow for a change in surface area for stem cell attachment. This provided the precise control of EB aggregate size and 3D architecture, in particular to study how elongation affected the development of cerebral organoids. After the microfilament-based EBs were formed, they were differentiated into the progenitor neuroectoderm and embedded into Matrigel droplets for the later differentiation stages. These microfilament-engineered cerebral organoids (enCORs) displayed enhanced neuroectoderm and cortical plate formation. Specifically, in relation to spheroid-based organoid generation, enCORs developed increased forebrain signatures, such as more defined brain tissue lobes, as well as higher gene ontology (GO) enrichment scores for “neurological system process” and “nervous system development”. This study demonstrated how microwell-based organoid engineering can be integrated with biomaterials to improve organoid tissue architectures. In many cases, however, microwells are simply used to control the initial aggregate geometry before embedding into hydrogels. For example, a recent study produced midbrain cerebral organoids by seeding neuronal progenitor cells into ultralow adhesion 96 well plates to define the size and geometries of 3D aggregates prior to embedding into Geltrex droplets [40]. This was also the case for most, if not all the brain organoid systems previously discussed.

Microwells can be used as standalone high-throughput tissue culture plates, or they can be fabricated via replica molding of hydrogels on silicone templates [54,55]. Replica-molded hydrogels have shown to support 3D aggregate culture of cells derived from multiple lineages, including 3D aggregates of hiPSC derived hepatocytes, cardiomyocytes, and neurons [56]. One study focusing on pancreatic organoids involved a novel hydrogel system termed Amikagel, which was a PEG-based hydrogel crosslinked with an antibiotic, amikacin hydrate [57]. Amikacin offered an easy approach to tune the physical and chemical properties of the gel by simply modulating the monomer mole ratio, and presented hydroxyl and amine sugar groups, resulting in a hydrophilic and biocompatible hydrogel system. Compared to the Matrigel controls, organoids grown in the Amikagel microwells exhibited enhanced pancreatic islet phenotypes, including the co-expression of PDX1 and NKX6.1, as well as enhanced endocrine functions. The authors envisioned that pancreatic organoids based on this novel hydrogel system had therapeutic potential in diabetes-related drug discovery, as well as for islet transplantation for type-1 diabetes treatment. Rivron and colleagues produced embryonic organoids with blastocyst-like structures using agarose microwells molded from poly(dimethyl siloxane) (PDMS). This method produced the embryonic organoids with blastocyst-like structures formed from ESC and trophoblast stem cell aggregates. When implanted in utero, these organoids induced deciduae formation, demonstrating the capability for in vivo organoid integration [58].

Microwells also allow for high-throughput organoid generation, as they can be fabricated into arrays of hundreds of individual wells or microcavities to meet scalability and standardization needs of drug development and diagnostics [59]. In a study of kidney organoid production, 384-well plates were used as the microwell arrays to seed and differentiate kidney organoids [60]. This system allowed for high-throughput production and phenotypic screening for nephrogenic toxicity and kidney disease. For instance, this platform illustrated apoptotic toxicity as a result of dose-dependent exposure to cisplatin. Alternatively, gene edited kidney organoids with mutations in polycystin (PKD1 or PKD2) exhibited cyst-like structures from kidney tubules, resembling polycystic kidney disease. For retinal organoid engineering, these systems still suffer from variable differentiation efficiency and low reproducibility [61]. For retinal organoid production, milliwells were constructed from PEG hydrogel to assemble aggregates of approximately 3000 cells. To further scale-up the production, 7 milliwells were individually placed into “macrowells” of a 24-well plate. Retinal organoids rapidly formed with 93% exhibiting retina-like structures, including optic vesicle-like and optic cup-like structures (Fig. 2C) [62]. The same group employed a similar method to fabricate microcavities at higher scale to generate gastrointestinal organoids. Each microcavity acts as a partition to trap individual organoids and created an organoid array [59]. This made it possible to screen for anti-cancer drug agents using colorectal cancer organoid models. These devices illustrate the great potentials of engineered microwells to scale-up, standardize, and automate organoid production and downstream analyses.

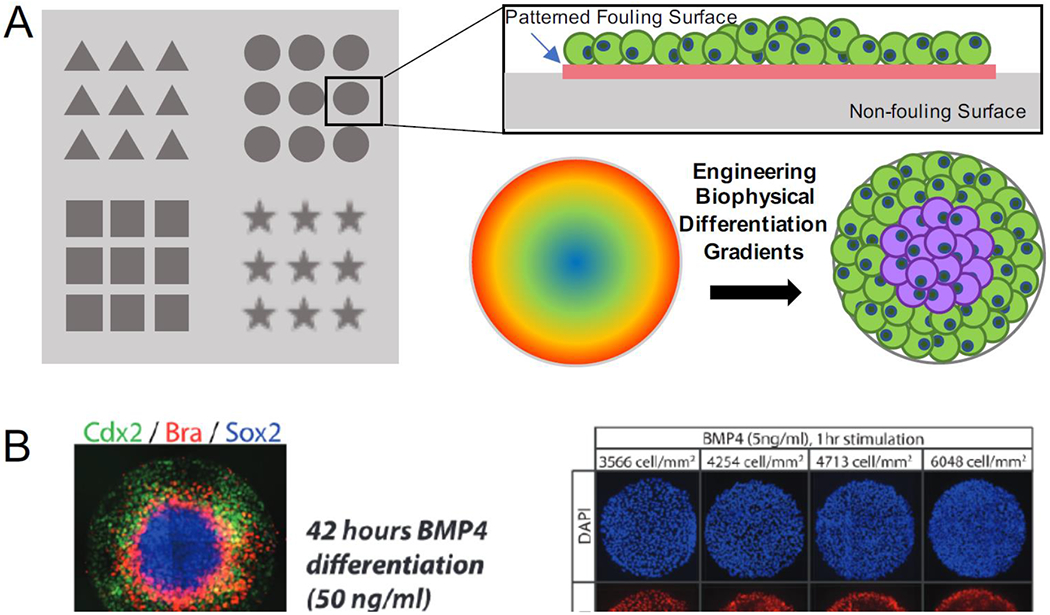

Micropatterning-based organoid platforms

Micropatterning approaches aim to present biophysical confinement to the cell colonies and create biophysical gradients across the patterns (Fig. 3A). These techniques involve selective surface patterning through photolithography and soft lithography. Micropatterned cells are fully confined within specific geometry, where cell outgrowth is impeded by the non-fouling biomaterials. Early studies showed that micropatterning via microcontact printing could be used to generate 3D stem cell aggregates with controlled sizes. Aggregate size influenced the ratio of primary precursor cells in mesoderm and cardiac induction efficiency, which resulted in varied efficiency of cardiac differentiation [63,64]. However, most current works take advantage of 2D nature of micropatterning to study cellular self-organization and tissue patterning under biophysical cues that spatiotemporally control cell differentiation. Kidney organoids generated by micropatterning techniques were used to model tubulogenesis within kidney [65], demonstrating comparable physiological formation of a vascular lumen surrounded by kidney epithelial cells. Micropatterns have also shown to influence various cell behaviors and cell differentiation due to differential cellular contact with pattern edges [66]. Surface micropatterning techniques has been shown to direct mesenchymal stem cell differentiation to either adipogenic or osteogenic lineage [67,68]. More recent work on micropatterning of PSCs also showed that cells along pattern perimeters experienced direct biophysical constraint, leading to spatial differentiation gradients across the patterns [69–71]. This infers that cell differentiation along the perimeter is heavily driven by biophysical cues, while cell differentiation at the pattern center is driven by cell-cell interactions. Various works have demonstrated spatial differentiation and self-organization of cell types promoted by the micropatterning technology, which thereby can be used as a suitable platform for controlling spatiotemporal cell organization within the organoids.

Figure 3. Cell micropatterning to control organoid spatiotemporal organization.

A) Micropatterning can be used to supply surface constraint by culturing stem cells in specific geometries, therefore creating biophysical differentiation gradients. B) Micropatterns induced fate specification into differential cell gradients across the entire patterns to model events similar to gastrulation (Reproduced from Etoc et al. Copyright 2016 © Elsevier). C) The biophysical gradients induced spatial organization of hiPSCs at early stages, which further differentiated into cardiac lineages with spatial tissue patterning of cardiomyocytes and smooth muscle-like cells (Reproduced from Ma et al. 2015).

Micropatterning, in particular, has shown to be a popular choice for modeling early embryogenesis. In the processes of blastulation and gastrulation, germ layer specification and pattern formation are under the influence of signaling and external mechanical properties. During this developmental milestone, cells divide and differentiate within the embryo under biophysical confinement, since the embryo itself does not grow significantly in size. Manipulating PSC colony size and shape has shown to direct cells into different embryonic lineages, depending on the geometry [72]. Hence, embryonic organoids, termed as gastruloids or embryoids, have emerged as in vitro models to explore complex embryological events [73,74]. By confining hESCs into circular patterns and inducing differentiation with bone morphogenic protein (BMP), cell colonies differentiated and organized into concentric ring-like pattern formation of ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm, and trophectoderm layers (Fig. 3B) [69,70,75]. Not only did patterning itself coordinate the cellular differentiation and spatial arrangement, but micropattern size had also shown to dictate specific developmental pathway that cells will favor. The ability of micropatterns to model embryogenesis and gastrulation has led questions of whether this technique can foster self-assembly of organoids resembling developmental processes beyond gastrulation. The cardiac organoids generated from micropatterned hiPSCs showed tissue self-assembly into a 3D dome-like structure after cardiac differentiation (Fig. 3C) [71,76]. Ma and colleagues demonstrated that cell condensation within the micropatterns in the early differentiation stages produced differential cell lineage gradients in the form of epithelial-like cells at the pattern perimeter and mesenchymal cells at the center. The formation of cardiac organoids showed bulk contracting cardiomyocytes towards the pattern center, while the stromal cells, identified by positive expression of smooth muscle markers, were found to be populated the radial perimeter of the micropatterns.

More recent work to model neurulation has implemented hESC micropatterning to generate neural organoids, called neuruloids [77]. Neural induction of micropatterned hESCs accelerated the formation of neural rosettes, which is a key feature of neural progenitor development. Further morphogen induction produced all four ectodermal lineages, including neural tube (PAX6+), neural crest (SOX10+), sensory placodes (SIX1+), and epidermis (TFAP2A+), which were spatially organized across multiple tissue-specific layers. As a disease model, the authors explored if neuruloids can model developmental neurogenesis disease. Neuruloids with the Huntington’s disease mutations (HTT−/− and CAG repeat expansions) showed early defects within the neural rosettes, such as loss of radial symmetry and reduction in lumen size. These morphological defects were also prominent in the PAX6 domain, indicating early effects in neural morphogenesis. Given the difficulty of studying brain developmental disorders in humans, this system serves as a promising alternative to characterize human ectodermal development and identify morphological factors involved in developmental neural diseases.

Micropatterns have proved that cells can sense their surroundings and alter their differentiation trajectories based on the different biophysical cues that each cell experiences. In particular, micropatterns facilitate cell assembly and self-organization of organoid through lineage specification, which are manifested based on the gradient of biochemical morphogens and biophysical confinement across the micropatterns [78]. The major limitation of micropatterning techniques is that geometrical constraints of these systems are primarily 2D on the bottom the cell culture plate. After the formation of 3D tissues, no constraint is provided to the organoids beyond the substrate, only resulting in a partial 3D model. Despite this limitation, manipulating the biomechanics by varying pattern geometry provides the opportunity to induce changes in mechanotransduction signaling, which allows us to better understand the biophysical principles involved in tissue self-organization mechanisms.

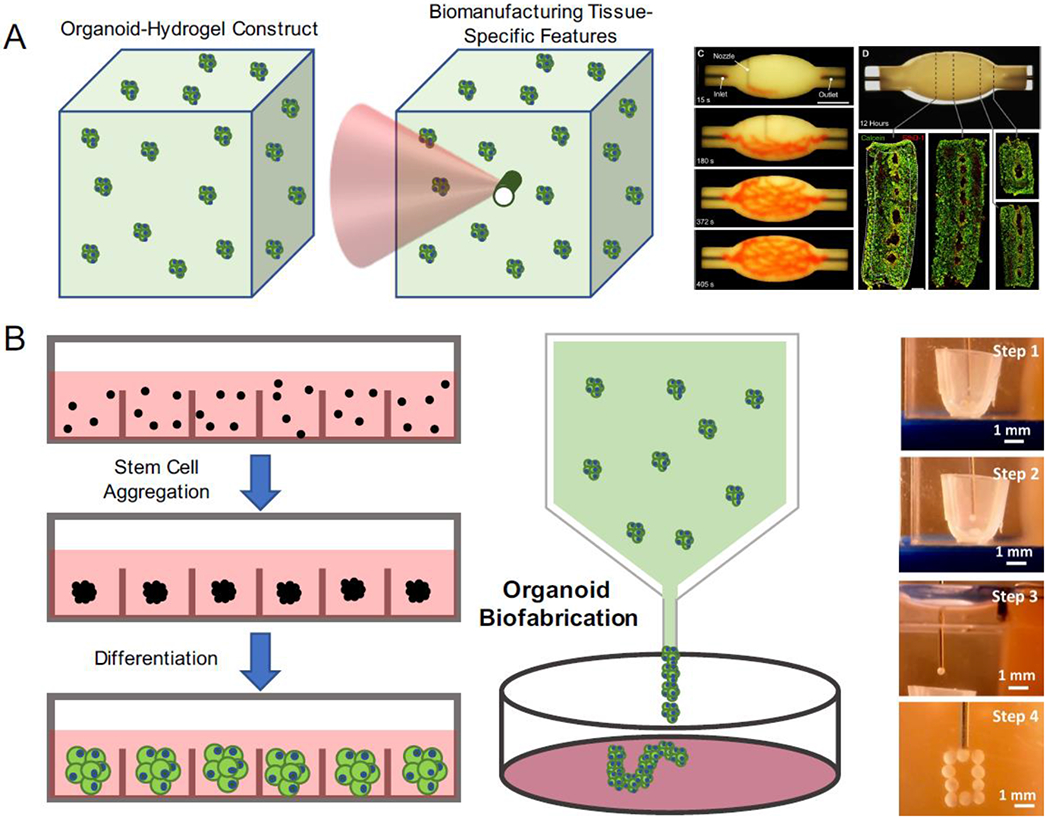

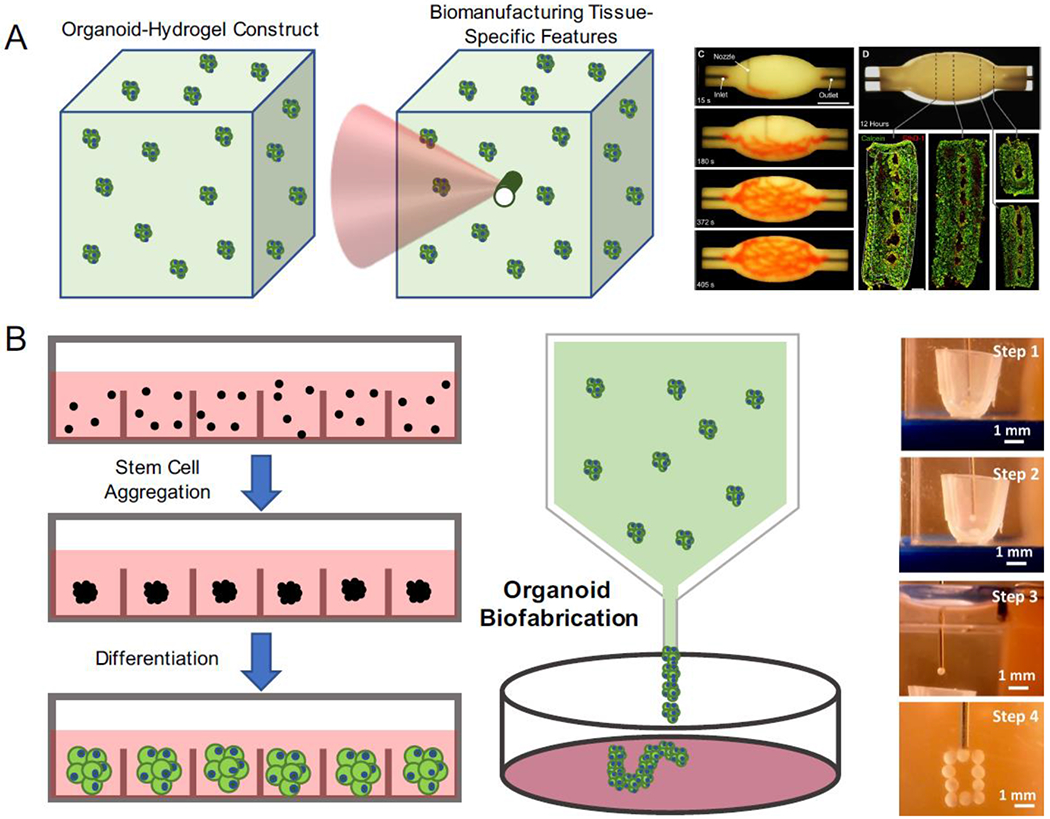

Biofabrication in organoid assembly

A challenge facing organoid engineering is their microscale nature, which does not fully recapitulate the formation and morphogenesis of macroscopic tissue architectures. Biofabrication techniques that build biological tissues and constructs with cells and biomaterials at a complex scale could further advance translational applications of organoid engineering. By converging organoid and biofabrication technologies, it provides great potential to engineer organoids with higher degrees of complexity, size and architecture to better resemble the organ of interest. In contrast to the view of individual organoids as miniature organs, organoids can also serve as modular building blocks for the assembly of large-scale tissue structures via organoid fusion (Fig. 4A) [43,79,80]. This technique is often termed as “bioassembly”, which can be easily incorporated with biomanufacturing technologies to produce large tissues at therapeutically relevant scales. Cell spheroids have been bioprinted into tissues using extrusion-based spheroid assembly in the hydrogel constructs. Implementing biological tissues as inks, aggregates were loaded and dispensed into an anchoring scaffold and built into desired biological structures, such as tubular structures to mimic vasculature. For example, cardiac and endothelial spheroids were printed into a tubular structure, which exhibited synchronous beating and lining of endothelial cells along hollow acellular regions [81]. The underlying principle behind these techniques is that fusion of spheroids achieves large tissue assembly [82]. More recently, freeform approaches took advantage of aspiration-assistance to build uniquely shaped stem cell spheroid constructs by transferring spheroids from media into a yield stress gel (Fig. 4B) [83,84]. In this technique, stem cell aggregates were transferred from a cell media reservoir into a support gel using aspiration force to reduce the spheroid damage and premature assembly that was often seen in the traditional extrusion bioprinting. This method was suitable for generating a wide variety of constructs, including tubular and circular structures, which were printed to successfully create cartilage and bone tissues.

Figure 4. Organoids as building blocks for tissue fabrication.

A) Organoids can also be used as building blocks to construct bulk tissues with specific features with biofabrication techniques. B) By molding organoids into a tissue construct, vasculature was bioprinted within the construct using sacrificial inks (Reproduced from Skylar-Scott et al. 2019). C) By taking advantage of high-throughput organoid production techniques, organoids can be harnessed as single units to manufacture and assemble large-scale tissues. Using “bioassembly” technique, organoids can be deposited and constructed into desired architectures (Reproduced from Ay an et al. 2020).

Bioassembled organoids can also offer a scaffold-free approach by direct assembling of aggregates and spheroids into complex tissues without the support of biomaterial scaffolds. These techniques facilitate the investigation of cell interactions during the assembly process, which can be advantageous in understanding inter-tissue and inter-organ crosstalk during tissue development [85]. These scaffold-free organoid-based building blocks are especially useful in studying the disease progression from a healthy tissue into a diseased tissue, as well as multi-organ synergy between the organs of close proximity. A modular organoid construct was developed by assembling dorsal- and ventral-specific forebrain organoids to model the interneuron migration across cerebral domains seen in human brain development [86]. This system was then used to model Timothy Syndrome (TS), a genetic neurodevelopmental disorder caused by a mutation in the CaV1.2 channel, resulting in gain-of-function neuronal excitation and defective neuron migration that can cause autism spectrum disorder and epilepsy. From this disease model, abnormal and less efficient interneuron migration was observed. This migration defect was caused by increased saltation frequency and decreased saltation length in these neurons, which could be rescued using L-type calcium channel blockers. This work, therefore illustrated that organoid bioassembly can be a useful tool in identifying molecular mechanisms and disease processes in the tissues, when their accessibility and availability is limited.

Organoid bioprinting using cell-laden bioinks makes it possible for precision engineering of organoid assembly to resemble tissues with structural complexity and regional specificity. A recent study showed that bioassembled organoids displayed self-healing ability, which allowed printing of sacrificial inks within the living tissues to create vasculature without causing defects in the tissue matrix [80]. Laser ablation was used to precisely bioprint the crypts and cavities that are signature of intestinal organoids [87]. Microchannels in this system were fabricated with microcavities that resembled intestinal crypts using laser ablation technique. These crypts can be easily perfused and colonized with intestinal stem cells to form intestinal epithelium. In addition to printing features within hydrogel scaffolds, Brassard and colleagues demonstrated that direct printing and depositing of stem cells within ECM scaffolds was able to control organoid shape and differentiation [88]. This allowed for precise control of cellular aggregate density and geometry, which is critical in organoid morphological development. As discussed earlier, morphogen gradients have shown to be critical in spatial patterning, regional specification and polarization of brain organoids. Precise organoid positioning was used to locally deposit cells programmed to release a SHH protein gradient to 3D constructed brain organoids [89]. This demonstrated that aggregate and organoid positioning is critical to optimize biological features of organoids. The precision can further be enhanced using bioprinting, which can engineer organizer regions to enable self-organization. The combination of organoids with 3D bioprinting techniques will further advance the development of organoids for accurate 3D organ modeling, enabling tailored engineering designs and optimized organoid production.

Organoid-on-Chip platforms

As organoid technologies continue to advance, there is a growing necessity for novel methods to enhance the precision, consistency and production of the organoids for greater degrees of mimicry native developing organs. Organ-on-chip platforms are engineered and constructed to incorporate key features, such as cell type, organization, and most importantly, the appropriate dynamic cellular microenvironment to mimic native tissue and organ. Although both organoids and organ-on-chip platforms represent the same goal of recapitulating native organ structure and function, they differ fundamentally in their experimental design approaches. For instance, organ-on-chips, traditionally based on microfluidic devices, are built upon fundamental biological knowledge of specific tissue structure and function to engineer adult-like tissue constructs using a top-down approach. In contrast, organoids rely on the self-organization properties of differentiating stem cells to generate developing tissues from a bottom-up perspective. A major limitation of organoid systems is the lack of biomechanical and biochemical control of the microenvironment due to the relative simplicity of current static culture conditions. In contrast, organ-on-chip devices have extensively demonstrated the influence of dynamic microenvironment on cellular and tissue organization [90,91]. By integrating these two approaches, organoid-on-chip platforms have the advantages of both organoids and organ-on-chips to create powerful tools to better mimic organogenesis in vitro (Fig. 5A) [92,93]. Combination of these two approaches allows us to control the microenvironment to regulate the organoid development, which can offer great potentials in biomedical research.

Figure 5. Organoid-on-chip platforms for biomimetic applications.

A) Chip platforms can serve to enhance current organoid systems by careful design of microfluidic networks. These networks can support intricate complex biomimetic processes, such as nutrient perfusion, biochemical gradients, and multi-organoid interactions. B) Microfluidic devices can be designed to supply morphogen gradients to induce essential tissue patterning, such as the polarization seen in neural tube patterning (Reproduced from Demers et al. 2016). C) Retina-on-chip organoids with active perfusions promotes the spatiotemporal organization of retinal epithelium and photoreceptors (Reproduced from Achberger et al. 2018).

Spatiotemporal control of organoid microenvironment

One major challenge in organoid engineering is the 3D depth of the tissues, which can affect the homogeneity of nutrient and oxygen diffusion across the entire tissue. Cerebral organoids, especially, have been shown to suffer from the lack of oxygen and nutrients to the tissue cores, resulting in large void regions of necrotic tissue [94]. Optimization of oxygen supply to enhance cerebral organoid viability and neuronal survival has been achieved by culturing the organoids at the air-liquid interface [95]. Using a slice-culture protocol, mature brain organoids were embedded in agarose and cut into 300 μm tissue sections at the culture medium surface. Brain organoid morphology has also been manipulated by using chip devices designed to constrain the tissue thickness, thus subsequent tissue growth was only permitted along specific axis, which increased the tissue surface area. This design, therefore maximized media and nutrient exposure to the tissues, which promoted tissue folding and convolution seen in the brain tissue [96,97]. Both of these works demonstrated the need to optimize essential nutrient exposure to produce organoids with high survival and reproducibility, as well as promote tissue morphogenesis into biologically relevant features. Furthermore, microfluidic culture systems can be designed to accommodate more complex and integrated nutritional needs of organoids as they develop in culture. The designs to mimic blood perfusion within microfluidic organ chips allow for efficient nutrient supply from fresh media to the organoids as they mature [98–100]. The integration of microfluidic-based media perfusion was shown to reduce the extent of necrosis at the cerebral organoid core and elevate neural differentiation from metabolic maturation [94]. By incorporating organoids to a chip platform, there is promising evidence for improving organoid quality while also enhancing biological mimicry.

Another challenge in organoid engineering is the need to simulate biochemical gradients. In traditional organoid culture, appropriate signaling cascades are activated by supplying morphogens directly to the cells at defined time points [101]. However, this does not simulate gradual morphogen distribution that is critical for in vivo tissue patterning [102]. Biochemical gradient control has been demonstrated to direct neural tube development from ESCs within a device with microchannels to diffuse morphogens through cell-laden hydrogel constructs (Fig. 5B) [103]. To create developmentally complex neural tissues, a microfluidic device was used to produce a concentration gradient of GSK3 inhibitor to activate WNT signaling gradient for spatial neural axis patterning. This method produced caudal organized neural tissues with pattern formation of forebrain, midbrain, and hindbrain regions [104]. Similarly, by controlling Hedgehog and BMP4 signaling gradients, neural tube patterning, such as spatial narrowing of motor neuron regions, occurred within the microchannel device. To model embryogenesis, microfluidic devices was constructed with three channels consisting of a central gel channel, a cell loading channel, and a chemical-induction channel [105]. Chemical diffusion was achieved by supplying differential induction factors across each channel. This system recapitulated landmark embryogenic events, including lumenogenesis of epiblast, formation of an amniotic cavity and induction of primitive streak cells.

In addition to morphogen and nutrient diffusion, the microfluidics-based platforms can be designed to provide various biomechanical stimuli, such as fluid shear stress and mechanical stress, thus promote the biomechanical and biochemical synergism required to regulate organ development [101,106]. For example, retinal organoids suffer from lack of vascularization, which is essential for photoreception of eye functions. Retinal organoids integrated within a perfusion microfluidic chip showed enhanced physiological processes through the maturation and polarization of the retinal pigment epithelium. This system also demonstrated applicability for drug toxicity testing, where the apoptosis of retinopathic cell occurred under the treatment of chloroquine and gentamicin (Fig. 5C) [93]. Similarly, shear stress on renal organoid-on-chips has been able to enhance the vascularization and maturation of renal features, including more mature podocytes and tubular compartments. Under flow conditions, the epithelium of renal organoids had upregulated expression of transcription factors (BNC2, NPAS2, TRPS1) seen in mature proximal tubules. Angiogenesis was also prevalent, as indicated by positive expression and organization of KDR and PECAM1 over time [107]. Furthermore, integration of stomach organoids into the microfluidic chips not only provided fluid flow, but also created rhythmic stretching through peristaltic pumps to mimic stomach contraction [108]. The resulting stomach organoids displayed peristaltic activity that can be controlled by adjusting the speed of the pump. Most importantly, the stomach organoids subjected to the peristaltic forces retained gastric-like features of luminal spaces.

Development of multi-tissue organoid systems

Despite the complexity of organoids on their own, organ development and proper tissue formation is facilitated by paracrine signaling from neighboring cells and tissues. This has been shown extensively in the organoid systems with incorporation of mesenchymal stromal cells to model mesenchymal-epithelial interactions [109]. Lung organoids with incorporation of mesenchymal stem cells were also shown to enhance alveolar differentiation [110]. In the intestinal organoids, a mesenchymal niche that could facilitate the mesenchymal-epithelial crosstalk was found to support gut growth and development [111]. A recent report identified that neuregulin 1 (NRG1) as a growth factor secreted by the mesenchymal stromal cells not only sustained intestinal tissue growth, but also induced tissue repair after injury. The deletion of the NRG1 gene resulted in lower proliferation, while supplement with recombinant NRG1 growth factor was able to recover proliferation and stimulate organoid growth [112]. This work, and many others, illustrate the need cell and tissue heterogeneity in the organoid systems.

Integration of organoids with organ-on-chip platforms provided us the capability to model multi-organ development. During development, organs develop concurrently and rely on signaling from the neighboring organs for proper organogenesis. Sophisticated design of microfluidic devices can permit the co-culture of multiple organoids in a compartmentalized manner but communicate via media flow between chambers. In the work of liver-intestine-stomach, vascularized liver organoids were first produced by co-culturing hepatic cells with endothelial cells under optimized flow conditions [113]. The liver organoids were then integrated with intestinal and stomach organoids, creating a multi-organoid model. Individual organoids were placed within separated chambers of a microplate array. The chambers were connected via microchannels, permitting medium exchange between organoids using a rocking motion. Inter-organ interaction was modelled using this system by monitoring the expression level of a bile synthesizing enzyme CYP7A1 in liver organoids. The single culture of liver organoids maintained a consistent level of CYP7A1, which was then downregulated by bile acid supplied by the intestinal organoids in the multi-organ co-culture condition.

In a heart-lung-liver multi-organoid system, individual microfluidic micro-reactor units were created to house one type of organoids [114]. The organoid chambers were connected via a central fluid routing reservoir and computer-controlled pump. To model multi-organ interaction, liver metabolism of cardiac functioning drugs was assessed. Propranolol to individual cardiac organoids resulted in a significant decrease in beat rate, whereas no effect was observed in heart-liver integrated organoid system. Similarly, epinephrine significantly increased beat rate in the cardiac-only systems, but less effective in the cardiac-liver system. In the triple organoid system, cardiotoxicity was observed in the presence of bleomycin, which did not result in cardiotoxicity in the cardiac only organoid system. Bleomycin exposure to the lung organoids resulted in the release of inflammatory factor IL-8, which induced the cardiotoxicity effect. Extension of this work by the same lab expanded the multi-organoid system consisting of liver, heart, lung, vascular, testis, colon, and brain compartment modules. The authors demonstrated drug metabolism in this system by supplying an anti-cancer drug with and without the liver module. Capecitabine and cyclophosphamide were both anti-cancer agents that required liver to metabolize the drugs into their active compounds. In the systems where liver organoids were absent, no cytotoxic effects were observed in the remaining modules. The addition of the liver module resulted in the metabolism of the active, but cytotoxic, compounds that resulted in increased cell death, especially in the heart and lung modules [115]. The multi-organoid systems can have high biomimetic potentials, especially for the applications of drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, because the inter-organ communication can better model complex physiological responses across multiple organs.

Conclusions and perspectives

Organoids provide an invaluable opportunity to study organ development and tissue patterning. These systems range in complexity, from simple hydrogel scaffolds to sophisticated and intricate designs to control multiple aspects of cellular microenvironment concurrently. Though each organoid system is tailored to optimize the development of the organ of interest, we have developed new tools to control organoid maturation and function, such as hydrogel properties, micropattern geometries, microfluidic morphogen supplies and combinations thereof. Despite the accomplishments over the past decade, there are still many challenges to be overcome before organoids can be adopted as a clinically relevant model system, especially for the heavy dependence on Matrigel to support organoid growth and differentiation. Disease modeling, specifically, has only been extensively applied to Matrigel-based ECMs, since they are well-established and accepted as a “gold standard” ECMs for organoid production. Further refinement of synthetic biomaterials will be necessary for future clinical translation and scale-up manufacturing purposes.

Organoid development has come a long way over the past decade, demonstrating capabilities to model disease, development and drug toxicity. Although each organoid system is unique, they all emerge from design principles of in vivo organ-mimicking by supplying a biophysically and biochemically appropriate culture systems. Advanced organoid culture systems should focus on controlling the emergence of biological characteristics. Current models lack the developmental aspect and spatial patterning of each individual organoid through differentiation. For instance, the multi-organoid models with preassembled organoids located inside their respective chambers only focused on the effect of paracrine signaling on neighboring organoid functions. Though these systems illustrated promising potential to study multi-organ interactions, they can be further tailored to accommodate organoid production. This advancement will be extremely valuable to not only study the multi-lineage cell specification within specific organs dependent on cell-cell communication, but also recapture the organ development influenced by the signaling from neighboring organs. Overall, precision organoid engineering will require intricate designs that balance the stem cell self-patterning, while also providing and adjusting constraints to meet developmental needs of organoids at different stages of their development.

On a biomaterial perspective on organoid engineering, smart biomaterials have been emerging as suitable materials to model dynamic changes occurring in living systems. Stimuli-responsive biomaterials have the ability to alter physical and biochemical environment triggered by exposing to an external stimulus [116]. These smart biomaterials have been used in numerous applications, such as on-demand drug delivery, actuation and dynamic mechanobiology [116–118]. These biomaterials have been used to stimulate the differentiation of stem cells through the dynamic changes in the mechanical properties or controlled release of biomolecules [119–122]. During the developmental stages, organoids require dynamic changes in their microenvironmental inputs due to the evolution of biological properties. Needless to say, stimuli-responsive biomaterials can also be applied to organoid systems, providing an additional level of complexity to the system. As described by Gjorevski et al., intestinal organoid development and colony survival at differentiation stages could be optimized in the hydrogels with varying material properties. A recent study by Hushka and colleagues explored scaffold softening using a photodegradable scaffold and study crypt formation as a function of matrix softening [123]. This study demonstrated the importance and dependence of intestinal organoid architecture on the dynamic mechanical environment.

Aside from modeling tissue development and morphogenesis, organoids also provide an invaluable opportunity to study inherited developmental diseases that are extremely challenging to study in humans. With advances in hiPSC technology, patient-specific or gene-edited diseased cell lines allow for modeling disease initiation and progression using organoid systems. Taking the advantages of gene-edited mutated hiPSCs with “isogenic” controls, it provides much more reliable model to elucidate the disease mechanisms resulted from targeted genetic mutation [39,124]. On the other side, the genetic mutations in patient-specific hiPSC-derived organoids can be corrected by CRISPR-Cas9 technique, in order to reverse the disease phenotypes. Beyond gene editing, advanced CRSIPR-Cas9 technologies, combined with high throughput organoid production, can rapidly identify key disease mutations, downstream biological processes, and drug pathway targets. Genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 library screening has been used in the tumor organoids to identify specific cancer targets as well as genes involved in cancer progression [125–127]. These screens can be applied to a wide variety of organoid systems to discover disease-contributing genes. Thereby, integration of organoid platforms and CRISPR-based toolkits (e.g., CRISPRa and CRISPRi) provide a powerful opportunity to rapidly assess disease mechanisms and advance therapeutic development and drug discovery. Advanced biotechnologies are also easily implemented to the organoid systems to improve our understanding of human organ development. A popular toolkit that has gained notable popularity to analyze organoids is next generation sequencing technologies. By characterizing organoids using transcriptome profiling, such as single-cell RNA sequencing, we can gain insight on their compositional profile at single cell scale. Single-cell genomic atlases have recently become a popular approach to assess the cellular complexity of organoids [128–130]. Knowing the complexity of cell compositions, as well as cell regulatory states, makes it possible to study the organoid developmental parallelism to human organogenesis, and discover new mechanisms driving organoid spatial patterning and cellular diversity. Recent reports have utilized cell atlases and genomic profiling to uncover multi-lineage fate specification, including co-development of the heart and gut, as well as communication networks between the epithelium and mesenchyme [13,131]. Single-cell genomic atlases, therefore, provide a powerful and comprehensive blueprint for evaluating organoids as suitable models for multi-lineage cell specification and even multi-organ development.

Statement of Significance.

The stem cell organoids have revolutionized the fields of developmental biology and tissue engineering, providing the opportunity to study human organ development and disease progression in vitro. Various works have demonstrated that organoids can be generated using a wide variety of engineering tools, materials, and systems. Specific culture microenvironment is tailored to support the formation, function, and physiology of the organ of interest. This review highlights the importance of the cellular microenvironment in organoid culture, the versatility of organoid engineering techniques, and future perspectives in the organoid field to build better organoid systems.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH NICHD (R01HD101130), NSF (CBET-1804875 and CBET-1943798), and SU intramural CUSE grant and Gerber auditory research grant. P.H. acknowledges support from the American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship (AHA 19PRE34380591).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- [1].Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA, Organogenesis in a dish: Modeling development and disease using organoid technologies, Science (80-,). 345 (2014) 1247125–1247125. 10.1126/science.1247125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Clevers H, Modeling Development and Disease with Organoids, Cell. 165 (2016) 1586–1597. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kim J, Koo BK, Knoblich JA, Human organoids: model systems for human biology and medicine, Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 21 (2020) 571–584. 10.1038/s41580-020-0259-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Fujii M, Sato T, Somatic cell-derived organoids as prototypes of human epithelial tissues and diseases, Nat. Mater (2020). 10.1038/s41563-020-0754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Fan H, Demirci U, Chen P, Emerging organoid models: Leaping forward in cancer research, J. Hematol. Oncol 12(2019) 1–10. 10.1186/sl3045-019-0832-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Brassard JA, Lutolf MP, Engineering Stem Cell Self-organization to Build Better Organoids, Cell Stem Cell. 24 (2019) 860–876. 10.1016/j.stem.2019.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sthijns MMJPE, Lapointe VLS, Van Blitterswijk CA, Building Complex Life through Self-Organization, Tissue Eng. - Part A. 25 (2019) 1341–1346. 10.1089/ten.tea.2019.0208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Wobus AM, Boheler KR, Embryonic stem cells: Prospects for developmental biology and cell therapy, Physiol. Rev 85 (2005) 635–678. 10.1152/physrev.00054.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Date S, Sato T, Mini-Gut Organoids: Reconstitution of the Stem Cell Niche, Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 31 (2015) 269–289. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100814-125218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Spence JR, Mayhew CN, Rankin SA, Kuhar MF, Vallance JE, Tolle K, Hoskins EE, Kalinichenko VV, Wells SI, Zorn AM, Shroyer NF, Wells JM, Directed differentiation of human pluripotent stem cells into intestinal tissue in vitro, Nature. 470 (2011) 105–110. 10.1038/nature09691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].McCracken KW, Catá EM, Crawford CM, Sinagoga KL, Schumacher M, Rockich BE, Tsai YH, Mayhew CN, Spence JR, Zavros Y, Wells JM, Modelling human development and disease in pluripotent stem-cell-derived gastric organoids, Nature. 516 (2014) 400–404. 10.1038/naturel3863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Dye BR, Hill DR, Ferguson MA, Tsai YH, Nagy MS, Dyal R, Wells JM, Mayhew CN, Nattiv R, Klein OD, White ES, Deutsch GH, Spence JR, In vitro generation of human pluripotent stem cell derived lung organoids, Elife. 2015 (2015) 1–25. 10.7554/eLife.05098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Silva AC, Matthys OB, Joy DA, Kauss MA, Natarajan V, Lai MH, Turaga D, Alexanian M, Bruneau BG, McDevitt TC, Developmental co-emergence of cardiac and gut tissues modeled by human iPSC-derived organoids, BioRxiv. (2020) 2020.04.30.071472. 10.1101/2020.04.30.071472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Vogt N, Human embryogenesis in a dish, Nat. Methods 17 (2020) 125. 10.1038/s41592-020-0740-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Shahbazi MN, Mechanisms of human embryo development: from cell fate to tissue shape and back, Development. 147 (2020). 10.1242/dev.190629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hussey GS, Dziki JL, Badylak SF, Extracellular matrix-based materials for regenerative medicine, Nat. Rev. Mater 3 (2018) 159–173. 10.1038/s41578-018-0023-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Hughes CS, Postovit LM, Lajoie GA, Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture., Proteomics. 10 (2010) 1886–1890. 10.1002/pmic.200900758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sato T, Vries RG, Snippert HJ, Van De Wetering M, Barker N, Stange DE, Van Es JH, Abo A, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H, Single Lgr5 stem cells build crypt-villus structures in vitro without a mesenchymal niche, Nature. 459 (2009) 262–265. 10.1038/nature07935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Poling HM, Wu D, Brown N, Baker M, Hausfeld TA, Huynh N, Chaffron S, Dunn JCY, Hogan SP, Wells JM, Helmrath MA, Mahe MM, Mechanically induced development and maturation of human intestinal organoids in vivo /692/4020/2741/520/1584, Nat. Biomed. Eng 2 (2018) 429–442. 10.1038/s41551-018-0243-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yoshida S, Miwa H, Kawachi T, Kume S, Takahashi K, Generation of intestinal organoids derived from human pluripotent stem cells for drug testing, Sci. Rep 10 (2020) 1–11. 10.1038/s41598-020-63151-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].McCauley HA, Wells JM, Pluripotent stem cell-derived organoids: using principles of developmental biology to grow human tissues in a dish, Development. 144 (2017) 958–962. 10.1242/dev.140731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Bayrer JR, Wang H, Nattiv R, Suzawa M, Escusa HS, Fletterick RJ, Klein OD, Moore DD, Ingraham HA, LRH-1 mitigates intestinal inflammatory disease by maintaining epithelial homeostasis and cell survival, Nat. Commun 9 (2018) 1–10. 10.1038/s41467-018-06137-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Workman MJ, Mahe MM, Trisno S, Poling HM, Watson CL, Sundaram N, Chang CF, Schiesser J, Aubert P, Stanley EG, Elefanty AG, Miyaoka Y, Mandegar MA, Conklin BR, Neunlist M, Brugmann SA, Helmrath MA, Wells JM, Engineered human pluripotent-stem-cell-derived intestinal tissues with a functional enteric nervous system, Nat. Med 23 (2017) 49–59. 10.1038/nm.4233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Heuckeroth RO, Hirschsprung disease — integrating basic science and clinical medicine to improve outcomes, Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 15 (2018) 152–167. 10.1038/nrgastro.2017.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lancaster MA, Corsini NS, Wolfinger S, Gustafson EH, Phillips AW, Burkard TR, Otani T, Livesey FJ, Knoblich JA, Guided self-organization and cortical plate formation in human brain organoids, Nat. Biotechnol 35 (2017) 659–666. 10.1038/nbt.3906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lancaster MA, Knoblich JA, Generation of cerebral organoids from human pluripotent stem cells, Nat. Protoc 9 (2014) 2329–2340. 10.1038/nprot.2014.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Camp JG, Badsha F, Florio M, Kanton S, Gerber T, Wilsch-Bräuninger M, Lewitus E, Sykes A, Hevers W, Lancaster M, Knoblich JA, Lachmann R, Pääbo S, Huttner WB, Treutlein B, Human cerebral organoids recapitulate gene expression programs of fetal neocortex development, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 112 (2015) 201520760. 10.1073/pnas.1520760112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Qian X, Nguyen HN, Song MM, Hadiono C, Ogden SC, Hammack C, Yao B, Hamersky GR, Jacob F, Zhong C, Yoon KJ, Jeang W, Lin L, Li Y, Thakor J, Berg DA, Zhang C, Kang E, Chickering M, Nauen D, Ho CY, Wen Z, Christian KM, Shi PY, Maher BJ, Wu H, Jin P, Tang H, Song H, Ming GL, Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure, Cell. 165 (2016) 1238–1254. 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Qian X, Jacob F, Song MM, Nguyen HN, Song H, Ming G, Generation of human brain region–specific organoids using a miniaturized spinning bioreactor, Nat. Protoc 13 (2018) 565–580. 10.1038/nprot.2017.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Lancaster MA, Renner M, Martin C-A, Wenzel D, Bicknell LS, Hurles ME, Homfray T, Penninger JM, Jackson AP, Knoblich JA, Cerebral organoids model human brain development and microcephaly, Nature. 501 (2013) 373–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Cugola FR, Fernandes IR, Russo FB, Freitas BC, Dias JLM, Guimarães KP, Benazzato C, Almeida N, Pignatari GC, Romero S, Polonio CM, Cunha I, Freitas CL, Brandaõ WN, Rossato C, Andrade DG, Faria DDP, Garcez AT, Buchpigel CA, Braconi CT, Mendes E, Sail AA, Zanotto PMDA, Peron JPS, Muotri AR, Beltrao-Braga PCBB, The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models, Nature. 534 (2016) 267–271. 10.1038/naturel8296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Dang J, Tiwari SK, Lichinchi G, Qin Y, Patil VS, Eroshkin AM, Rana TM, Zika Virus Depletes Neural Progenitors in Human Cerebral Organoids through Activation of the Innate Immune Receptor TLR3, Cell Stem Cell. 19 (2016) 258–265. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Garcez PP, Loiola EC, Da Costa RM, Higa LM, Trindade P, Delvecchio R, Nascimento JM, Brindeiro R, Tanuri A, Rehen SK, Zika virus: Zika virus impairs growth in human neurospheres and brain organoids, Science (80-,). 352 (2016) 816–818. 10.1126/science.aaf6116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bershteyn M, Nowakowski TJ, Pollen AA, Di Lullo E, Nene A, Wynshaw-Boris A, Kriegstein AR, Human iPSC-Derived Cerebral Organoids Model Cellular Features of Lissencephaly and Reveal Prolonged Mitosis of Outer Radial Glia, Cell Stem Cell. 20 (2017) 435–449.e4. 10.1016/j.stem.2016.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Iefremova V, Manikakis G, Krefft O, Jabali A, Weynans K, Wilkens R, Marsoner F, Brandi B, Muller FJ, Koch P, Ladewig J, An Organoid-Based Model of Cortical Development Identifies Non-Cell-Autonomous Defects in Wnt Signaling Contributing to Miller-Dieker Syndrome, Cell Rep. 19 (2017) 50–59. 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Fan W, Sun Y, Shi Z, Wang H, Deng J, Mouse induced pluripotent stem cells-derived Alzheimer’s disease cerebral organoid culture and neural differentiation disorders, Neurosci. Lett 711 (2019). 10.1016/j.neulet.2019.134433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ghatak S, Dolatabadi N, Trudler D, Zhang X, Wu Y, Mohata M, Ambasudhan R, Talantova M, Lipton SA, Mechanisms of hyperexcitability in alzheimer’s disease hiPSC-derived neurons and cerebral organoids vs. Isogenic control, Elife. 8 (2019) 1–22. 10.7554/eLife.50333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Smits LM, Reinhardt L, Reinhardt P, Glatza M, Monzel AS, Stanslowsky N, Rosato-Siri MD, Zanon A, Antony PM, Bellmann J, Nicklas SM, Hemmer K, Qing X, Berger E, Kalmbach N, Ehrlich M, Bolognin S, Hicks AA, Wegner F, Stemeckert JL, Schwamborn JC, Modeling Parkinson’s disease in midbrain-like organoids, Npj Park. Dis 5 (2019). 10.1038/s41531-019-0078-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kim H, Park HJ, Choi H, Chang Y, Park H, Shin J, Kim J, Lengner CJ, Lee YK, Kim J, Modeling G2019S-LRRK2 Sporadic Parkinson’s Disease in 3D Midbrain Organoids, Stem Cell Reports. 12 (2019) 518–531. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Nickels SL, Modamio J, Mendes-Pinheiro B, Monzel AS, Betsou F, Schwamborn JC, Reproducible generation of human midbrain organoids for in vitro modeling of Parkinson’s disease, Stem Cell Res. 46 (2020). 10.1016/j.scr.2020.101870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Abbas Y, Brunei LG, Hollinshead MS, Fernando RC, Gardner L, Duncan I, Moffett A, Best S, Turco MY, Burton GJ, Cameron RE, Generation of a three-dimensional collagen scaffold-based model of the human endometrium, Interface Focus. 10 (2020). 10.1098/rsfs.2019.0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Jee JH, Lee DH, Ko J, Hahn S, Jeong SY, Kim HK, Park E, Choi SY, Jeong S, Lee JW, Cho HJ, Kwon MS, Yoo J, Development of Collagen-Based 3D Matrix for Gastrointestinal Tract-Derived Organoid Culture, Stem Cells Int. 2019 (2019). 10.1155/2019/8472712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Sachs N, Tsukamoto Y, Kujala P, Peters PJ, Clevers H, Intestinal epithelial organoids fuse to form self-organizing tubes in floating collagen gels, Dev 144 (2017) 1107–1112. 10.1242/dev.143933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Gjorevski N, Sachs N, Manfrin A, Giger S, Bragina ME, Ordóñez-Morán P, Clevers H, Lutolf MP, Designer matrices for intestinal stem cell and organoid culture, Nat. Publ. Gr 539 (2016) 560–564. 10.1038/nature20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Gjorevski N, Lutolf MP, Synthesis and characterization of well-defined hydrogel matrices and their application to intestinal stem cell and organoid culture, Nat. Protoc 12 (2017) 2263–2274. 10.1038/nprot.2017.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Magno V, Meinhardt A, Wemer C, Polymer Hydrogels to Guide Organotypic and Organoid Cultures, Adv. Funct. Mater 2000097 (2020). 10.1002/adfm.202000097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Capeling MM, Czerwinski M, Huang S, Tsai YH, Wu A, Nagy MS, Juliar B, Sundaram N, Song Y, Han WM, Takayama S, Alsberg E, Garcia AJ, Helmrath M, Putnam AJ, Spence JR, Nonadhesive Alginate Hydrogels Support Growth of Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Intestinal Organoids, Stem Cell Reports. 12 (2019) 381–394. 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Broguiere N, Isenmann L, Hirt C, Ringel T, Placzek S, Cavalli E, Ringnalda F, Villiger L, Züllig R, Lehmann R, Rogler G, Heim MH, Schüler J, Zenobi-Wong M, Schwank G, Growth of Epithelial Organoids in a Defined Hydrogel, Adv. Mater 30 (2018). 10.1002/adma.201801621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].DiMarco RL, Dewi RE, Bernal G, Kuo C, Heilshorn SC, Protein-engineered scaffolds for in vitro 3D culture of primary adult intestinal organoids, Biomater. Sci 3 (2015) 1376–1385. 10.1039/C5BM00108K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chaudhuri O, Gu L, Klumpers D, Darnell M, Bencherif SA, Weaver JC, Huebsch N, Lee HP, Lippens E, Duda GN, Mooney DJ, Hydrogels with tunable stress relaxation regulate stem cell fate and activity, Nat. Mater 15 (2016) 326–334. 10.1038/nmat4489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Cruz-Acuña R, Quires M, Farkas AE, Dedhia PH, Huang S, Siuda D, García-Hernández V, Miller AJ, Spence JR, Nusrat A, García AJ, Synthetic hydrogels for human intestinal organoid generation and colonic wound repair, Nat. Cell Biol 19 (2017) 1326–1335. 10.1038/ncb3632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Choi YY, Chung BG, Lee DH, Khademhosseini A, Kim J-H, Lee S-H, Controlled-size embryoid body formation in concave microwell arrays, Biomaterials. 31 (2010) 4296–4303. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.01.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Van Den Brink SC, Baillie-Johnson P, Balayo T, Hadjantonakis AK, Nowotschin S, Turner DA, Arias AM, Symmetry breaking, germ layer specification and axial organisation in aggregates of mouse embryonic stem cells, Dev 141 (2014) 4231–4242. 10.1242/dev.113001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Hwang YS, Bong GC, Ortmann D, Hattori N, Moeller HC, Khademhosseinia A, Microwell-mediated control of embryoid body size regulates embryonic stem cell fate via differential expression of WNT5a and WNT11, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106 (2009) 16978–16983. 10.1073/pnas.0905550106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Vrij EJ, Espinoza S, Heilig M, Kolew A, Schneider M, Van Blitterswijk CA, Truckenmüller RK, Rivron NC, 3D high throughput screening and profiling of embryoid bodies in thermoformed microwell plates, Lab Chip. 16 (2016) 734–742. 10.1039/c5lc01499a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Hookway TA, Butts JC, Lee E, Tang H, McDevitt TC, Aggregate formation and suspension culture of human pluripotent stem cells and differentiated progeny, Methods 101 (2016) 11–20. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Candiello J, Grandhi TSP, Goh SK, Vaidya V, Lemmon-Kishi M, Eliato KR, Ros R, Kumta PN, Rege K, Banerjee I, 3D heterogeneous islet organoid generation from human embryonic stem cells using a novel engineered hydrogel platform, Biomaterials. 177 (2018) 27–39. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Rivron NC, Frias-Aldeguer J, Vrij EJ, Boisset JC, Korving J, Vivié J, Truckenmüller RK, Van Oudenaarden A, Van Blitterswijk CA, Geijsen N, Blastocyst-like structures generated solely from stem cells, Nature. 557 (2018) 106–111. 10.1038/s41586-018-0051-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Brandenberg N, Hoehnel S, Kuttler F, Homicsko K, Ceroni C, Ringel T, Gjorevski N, Schwank G, Coukos G, Turcatti G, Lutolf MP, High-throughput automated organoid culture via stem-cell aggregation in microcavity arrays, Nat. Biomed. Eng 4 (2020). 10.1038/s41551-020-0565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Czerniecki SM, Cruz NM, Harder JL, Menon R, Annis J, Otto EA, Gulieva RE, Islas LV, Kim YK, Tran LM, Martins TJ, Pippin JW, Fu H, Kretzler M, Shankland SJ, Himmelfarb J, Moon RT, Paragas N, Freedman BS, High-Throughput Screening Enhances Kidney Organoid Differentiation from Human Pluripotent Stem Cells and Enables Automated Multidimensional Phenotyping, Cell Stem Cell. 22 (2018) 929–940.e4. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Ovando-Roche P, Georgiadis A, Smith AJ, Pearson RA, Ali RR, Harnessing the Potential of Human Pluripotent Stem Cells and Gene Editing for the Treatment of Retinal Degeneration, Curr. Stem Cell Reports 3 (2017) 112–123. 10.1007/s40778-017-0078-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Decembrini S, Hoehnel S, Brandenberg N, Arsenijevic Y, Lutolf MP, Hydrogel-based milliwell arrays for standardized and scalable retinal organoid cultures, Sci. Rep 10 (2020) 1–10. 10.1038/s41598-020-67012-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bauwens CL, Peerani R, Niebruegge S, Woodhouse KA, Kumacheva E, Husain M, Zandstra PW, Control of Human Embryonic Stem Cell Colony and Aggregate Size Heterogeneity Influences Differentiation Trajectories, Stem Cells. 26 (2008) 2300–2310. 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]