Abstract

Background

Fear of falling (FOF) is prevalent among older adults and associated with adverse health outcomes. Over recent years a substantial body of research has emerged on its epidemiology, associated factors, and consequences. This scoping review summarizes the FOF literature published between April 2015 and March 2020 in order to inform current practice and identify gaps in the literature.

Methods

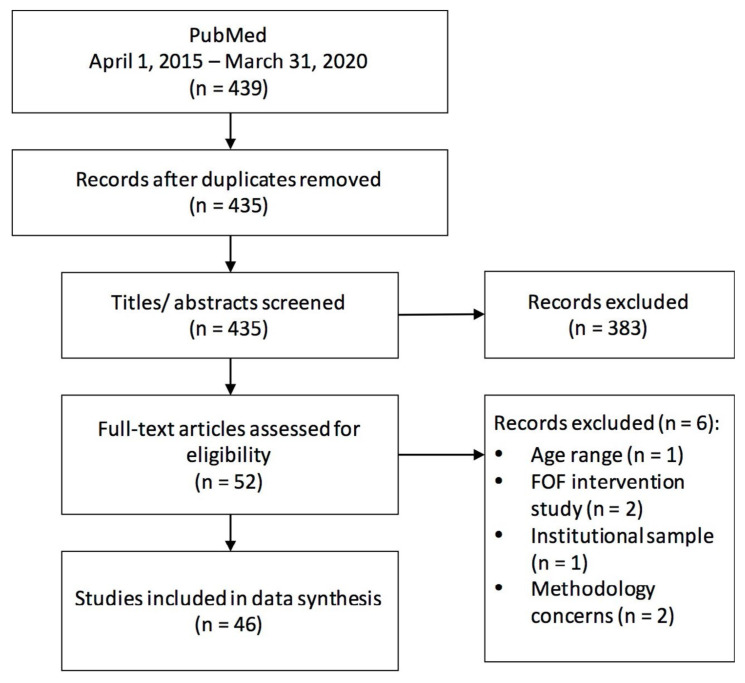

A total of 439 articles related to FOF in older adults were identified, 56 selected for full-text review, and 46 retained for data extraction and synthesis.

Results

The majority of included studies were cross-sectional. Older age, female sex, previous falls, worse physical performance, and depressive symptoms were the factors most consistently associated with FOF. Studies that measured FOF with a single question reported a significantly lower prevalence of FOF than those using the Falls Efficacy Scale, a continuous measure. FOF was associated with higher likelihoods of future falls, short-term mortality, and functional decline.

Conclusions

Comparisons between studies were limited by inconsistent definition and measurement of FOF, falls, and other characteristics. Consensus on how to measure FOF and which participant characteristics to evaluate would address this issue. Gaps in the literature include clarifying the relationships between FOF and cognitive, psychological, social, and environmental factors.

Keywords: fear of falling, falls, older adults, scoping review

INTRODUCTION

In geriatric practice, fear of falling (FOF) was initially defined as a phobic reaction to standing or walking called “ptophobia”.(1) The concept of FOF has since expanded to include reductions in balance self-efficacy,(2,3) fearful anticipation of falling,(4) and/or a deleterious avoidance of activity resulting from FOF.(5) Prevalence estimates among older persons for FOF range from 20 to 39% overall(6) and from 40 to 73% in those who have fallen.(7) The consequences of FOF for older persons include loss of independence, deconditioning from activity restriction, greater risk for subsequent falls, reduced social activity, and lower quality of life.(6,8)

Given its high prevalence and harmful consequences, there is a substantial body of research on identifying factors associated with FOF. Risk factors for FOF include sociodemographic, physical, psychological, and environmental factors.(7–10) FOF has also been studied as a predictor of future falls(11) and declines in cognition,(12) function,(13) and short-term survival.(14) Considerably less work has been done recently to synthesize these emerging findings to inform current practice and future research related to FOF.

Current FOF measures range from asking a single question about FOF (e.g., “Are you afraid of falling?”) to scales examining either FOF during specific activities (e.g., Survey of Activities and Fear of Falling in the Elderly(15)) or perceived self-efficacy in one’s balance and/or ability to avoid falls (e.g., Falls Efficacy Scale(16)). It is unclear what effect these different operational definitions have on the detection and prevalence of FOF in older populations. The lack of a consistent definition for FOF has led to making comparisons between studies difficult.(7,17)

The aim of this scoping review is to examine broad aspects of the FOF literature, including the world-wide epidemiology of FOF, the different approaches used to detect FOF and their impact on prevalence estimates, factors associated with its occurrence and outcomes, and knowledge gaps that future research could address. The most recent systematic review of factors associated with FOF was by Denkinger et al.(18) It was published in 2015. Our intent was also to update this review of FOF and the factors associated with it by examining publications published since 2015. To address these objectives, we performed a scoping review of observational studies on FOF published from April 2015 to March 2020. This methodology(19) was chosen as it best aligned with our desire to: (1) summarize recent FOF research; and, (2) use this data to inform current practice and the need for future research on FOF.

METHODS

Initial Search Strategy

Using the free text term “fear of falling” in late April of 2020, we searched for relevant articles on the PubMed database that were published between April 1, 2015 and March 31, 2020. This search was restricted to publications in English that included adults ≥ 65 years of age. PubMed was utilized as we were interested in published biomedical and life sciences findings.

Selection Process

The selection of papers took place in two steps. First, two independent reviewers (SM, DBH) reviewed all titles and abstracts to select papers for full-text review. Studies were excluded if they did not represent original research (note: we did include any scoping or systematic reviews on FOF published during the time period of interest); were restricted to a specific disease or clinic population (e.g., patients with cerebrovascular disease); dealt solely with interventions for FOF (we wished to avoid confounding by the impact of the intervention); reported solely on associations with performance-based measures (e.g., gait speed); used only qualitative methods to assess FOF; assessed only the impact of FOF on a third party (e.g., caregiver); and/or, sampled only older adults not residing in the community (e.g., institutionalized individuals). Included studies had to: measure and report on FOF; perform quantitative analyses involving FOF (e.g., examining an association between FOF and some other variable); have a study population with a mean participant age ≥ 60; and, not meet any of the exclusionary criteria. Duplicate publications were removed at this stage. Discordant ratings were discussed by the two raters with a final consensus decision reached.

In the second step, full texts of selected articles were retrieved and reviewed using the same criteria by two pairs of independent reviewers. One pair (CH and PE) reviewed articles where the last initial of the lead authors were A–H while the other pair (SM and DBH) reviewed papers where the last initial of the lead authors were I–Z. Papers could be excluded at this stage based on the noted inclusion or exclusion criteria. Any discordant ratings as to whether the paper should be retained were discussed by the two raters with a final consensus decision reached. Articles retained after this review went on to the data extraction and synthesis stage.

Data Extraction

Using a standardized data extraction form, the same two pairs of independent reviewers examined their assigned articles and extracted data on: study population; approach used to detect FOF; prevalence and/or incidence of FOF; factors associated with FOF; and the effect of FOF on all relevant outcomes reported. Data extraction also included comments on study limitations and potential sources of bias present in the selected articles. Any discrepancies in the data extracted were dealt with by review of the source paper. These findings were then collated and analyzed by all the authors with consensus reached on the interpretation of the data and the conclusions reached in this review.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive and inferential statistics were extracted from the papers reviewed. De novo statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 24.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). An independent samples t-test was used to compare mean FOF prevalence values between studies that used single questions compared to those that used the FES to measure FOF. This analysis was two-tailed with significance set at p < .05.

RESULTS

Search Results

A total of 439 articles related to FOF in older adults were identified. Fifty-six were selected by at least one reviewer for full-text review. Agreement on the title and abstract screening was 97.7%. The four articles with discordant results were excluded after discussion. An additional five were excluded at the full-text review stage and one was excluded during data extraction. Forty-six articles were retained for data extraction and synthesis (Table 1). Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the selection process.

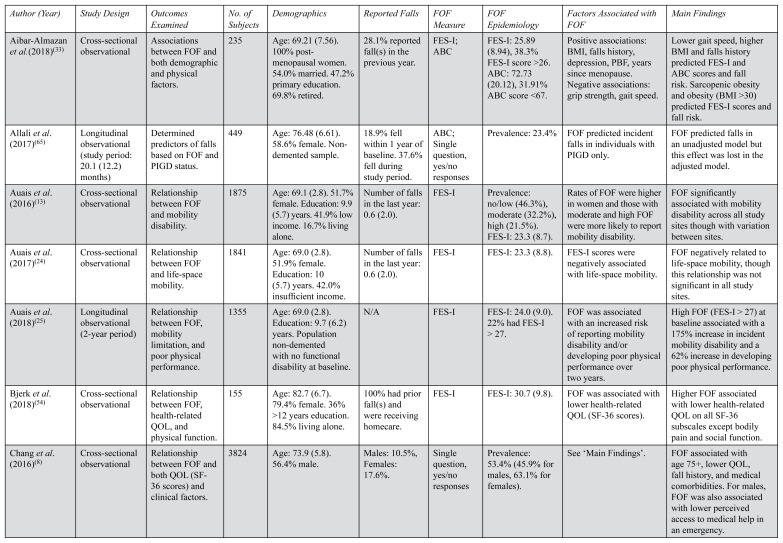

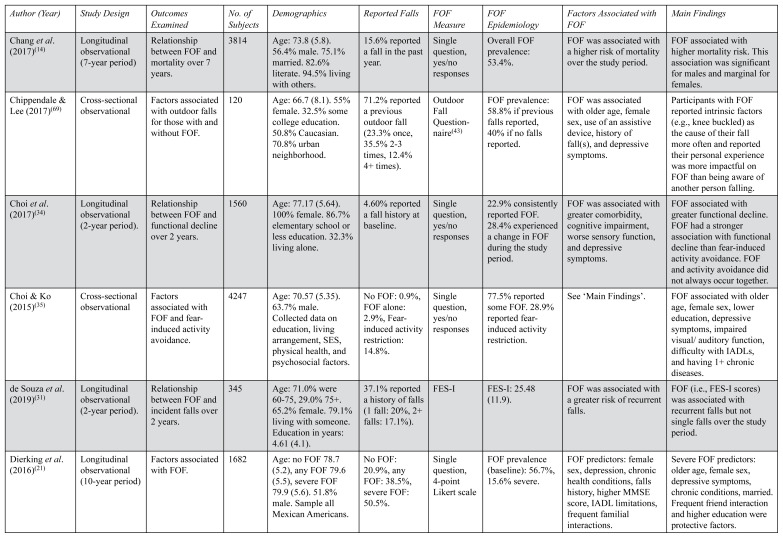

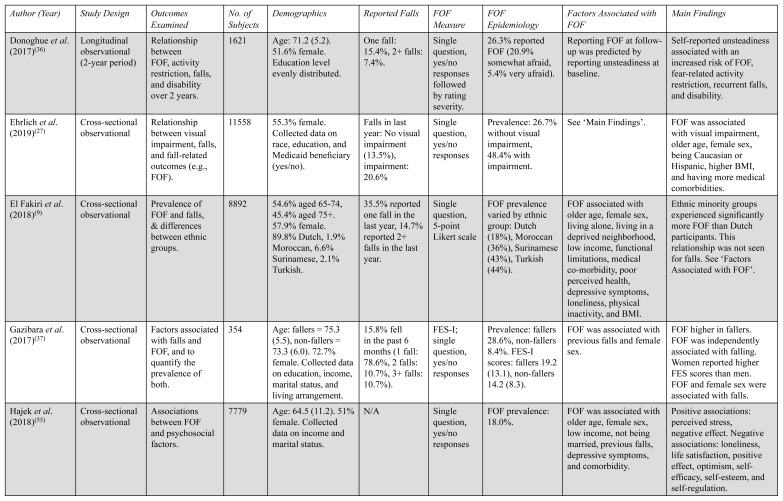

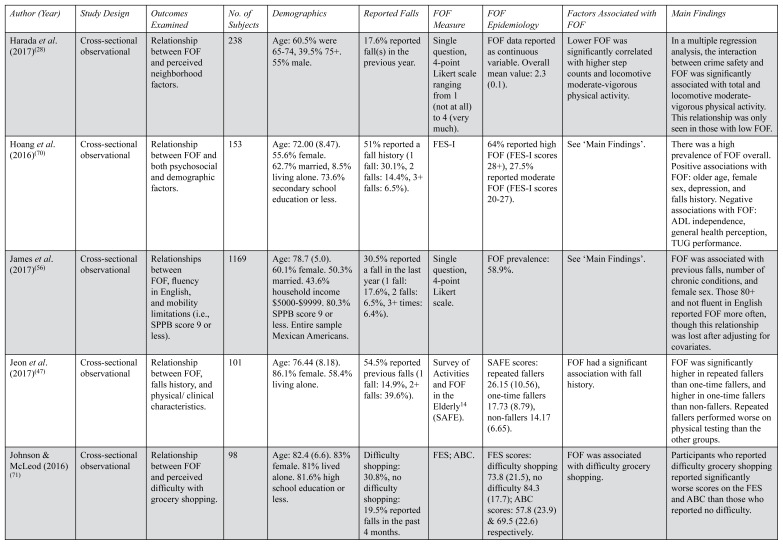

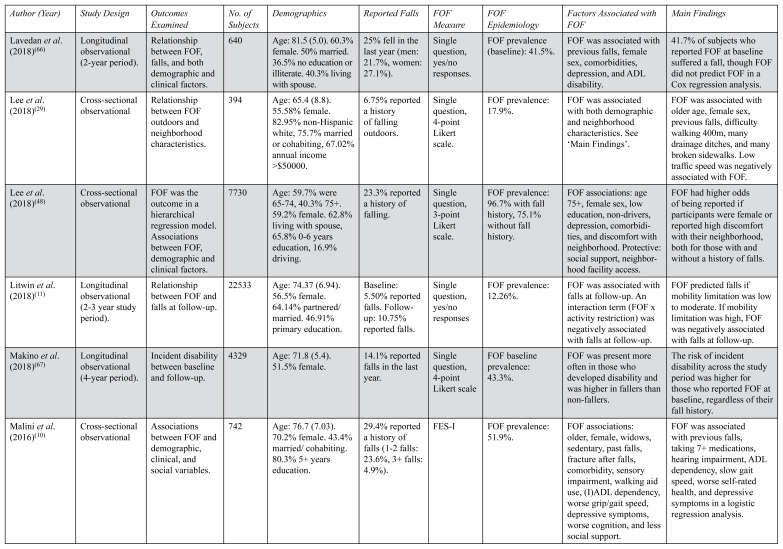

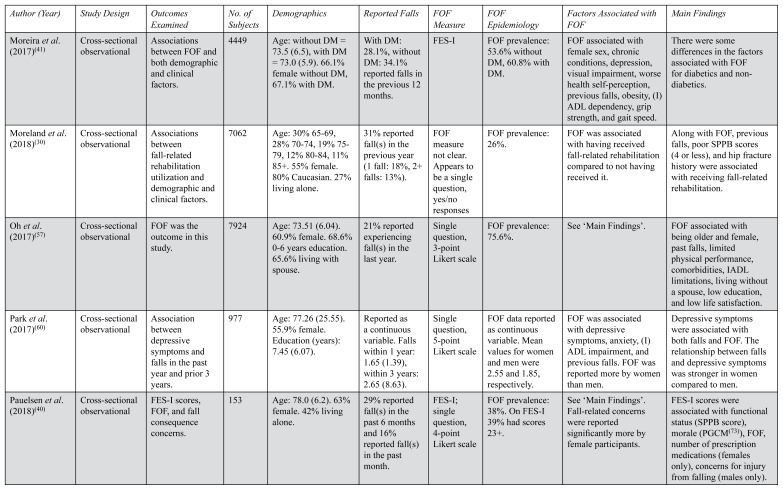

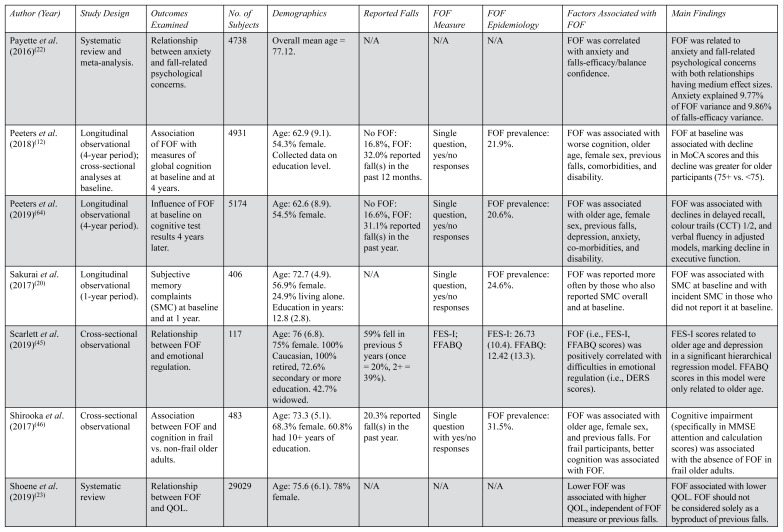

TABLE 1.

Overview of Study Characteristicsa

| Author (Year) | Study Design | Outcomes Examined | No. of Subjects | Demographics | Reported Falls | FOF Measure | FOF Epidemiology | Factors Associated with FOF | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aibar-Almazan et al.(2018)(33) | Cross-sectional observational | Associations between FOF and both demographic and physical factors. | 235 | Age: 69.21 (7.56). 100% post-menopausal women. 54.0% married. 47.2% primary education. 69.8% retired. | 28.1% reported fall(s) in the previous year. | FES-I; ABC | FES-I: 25.89 (8.94), 38.3% FES-I score >26. ABC: 72.73 (20.12), 31.91% ABC score <67. | Positive associations: BMI, falls history, depression, PBF, years since menopause. Negative associations: grip strength, gait speed. | Lower gait speed, higher BMI and falls history predicted FES-I and ABC scores and fall risk. Sarcopenic obesity and obesity (BMI >30) predicted FES-I scores and fall risk. |

| Allali et al. (2017)(65) | Longitudinal observational (study period: 20.1 (12.2) months) | Determined predictors of falls based on FOF and PIGD status. | 449 | Age: 76.48 (6.61). 58.6% female. Non-demented sample. | 18.9% fell within 1 year of baseline. 37.6% fell during study period. | ABC; Single question, yes/no responses | Prevalence: 23.4% | FOF predicted incident falls in individuals with PIGD only. | FOF predicted falls in an unadjusted model but this effect was lost in the adjusted model. |

| Auais et al. (2016)(13) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF and mobility disability. | 1875 | Age: 69.1 (2.8). 51.7% female. Education: 9.9 (5.7) years. 41.9% low income. 16.7% living alone. | Number of falls in the last year: 0.6 (2.0). | FES-I | Prevalence: no/low (46.3%), moderate (32.2%), high (21.5%). FES-I: 23.3 (8.7). | Rates of FOF were higher in women and those with moderate and high FOF were more likely to report mobility disability. | FOF significantly associated with mobility disability across all study sites though with variation between sites. |

| Auais et al. (2017)(24) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF and life-space mobility. | 1841 | Age: 69.0 (2.8). 51.9% female. Education: 10 (5.7) years. 42.0% insufficient income. | Number of falls in the last year: 0.6 (2.0). | FES-I | FES-I: 23.3 (8.8). | FES-I scores were negatively associated with life-space mobility. | FOF negatively related to life-space mobility, though this relationship was not significant in all study sites. |

| Auais et al. (2018)(25) | Longitudinal observational (2-year period) | Relationship between FOF, mobility limitation, and poor physical performance. | 1355 | Age: 69.0 (2.8). Education: 9.7 (6.2) years. Population non-demented with no functional disability at baseline. | N/A | FES-I | FES-I: 24.0 (9.0). 22% had FES-I > 27. | FOF was associated with an increased risk of reporting mobility disability and/or developing poor physical performance over two years. | High FOF (FES-I > 27) at baseline associated with a 175% increase in incident mobility disability and a 62% increase in developing poor physical performance. |

| Bjerk et al. (2018)(54) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF, health-related QOL, and physical function. | 155 | Age: 82.7 (6.7). 79.4% female. 36% >12 years education. 84.5% living alone. | 100% had prior fall(s) and were receiving homecare. | FES-I | FES-I: 30.7 (9.8). | FOF was associated with lower health-related QOL (SF-36 scores). | Higher FOF associated with lower health-related QOL on all SF-36 subscales except bodily pain and social function. |

| Chang et al. (2016)(8) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF and both QOL (SF-36 scores) and clinical factors. | 3824 | Age: 73.9 (5.8). 56.4% male. | Males: 10.5%, Females: 17.6%. | Single question, yes/no responses | Prevalence: 53.4% (45.9% for males, 63.1% for females). | See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF associated with age 75+, lower QOL, fall history, and medical comorbidities. For males, FOF was also associated with lower perceived access to medical help in an emergency. |

| Chang et al. (2017)(14) | Longitudinal observational (7-year period) | Relationship between FOF and mortality over 7 years. | 3814 | Age: 73.8 (5.8). 56.4% male. 75.1% married. 82.6% literate. 94.5% living with others. | 15.6% reported a fall in the past year. | Single question, yes/no responses | Overall FOF prevalence: 53.4%. | FOF was associated with a higher risk of mortality over the study period. | FOF associated with higher mortality risk. This association was significant for males and marginal for females. |

| Chippendale & Lee (2017)(69) | Cross-sectional observational | Factors associated with outdoor falls for those with and without FOF. | 120 | Age: 66.7 (8.1). 55% female. 32.5% some college education. 50.8% Caucasian. 70.8% urban neighborhood. | 71.2% reported a previous outdoor fall (23.3% once, 35.5% 2–3 times, 12.4% 4+ times). | Outdoor Fall Question-naire(43) | FOF prevalence: 58.8% if previous falls reported, 40% if no falls reported. | FOF was associated with older age, female sex, use of an assistive device, history of fall(s), and depressive symptoms. | Participants with FOF reported intrinsic factors (e.g., knee buckled) as the cause of their fall more often and reported their personal experience was more impactful on FOF than being aware of another person falling. |

| Choi et al. (2017)(34) | Longitudinal observational (2-year period). | Relationship between FOF and functional decline over 2 years. | 1560 | Age: 77.17 (5.64). 100% female. 86.7% elementary school or less education. 32.3% living alone. | 4.60% reported a fall history at baseline. | Single question, yes/no responses | 22.9% consistently reported FOF. 28.4% experienced a change in FOF during the study period. | FOF was associated with greater comorbidity, cognitive impairment, worse sensory function, and depressive symptoms. | FOF associated with greater functional decline. FOF had a stronger association with functional decline than fear-induced activity avoidance. FOF and activity avoidance did not always occur together. |

| Choi & Ko (2015)(35) | Cross-sectional observational | Factors associated with FOF and fear-induced activity avoidance. | 4247 | Age: 70.57 (5.35). 63.7% male. Collected data on education, living arrangement, SES, physical health, and psychosocial factors. | No FOF: 0.9%, FOF alone: 2.9%, Fear-induced activity restriction: 14.8%. | Single question, yes/no responses | 77.5% reported some FOF. 28.9% reported fear-induced activity restriction. | See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF associated with older age, female sex, lower education, depressive symptoms, impaired visual/auditory function, difficulty with IADLs, and having 1+ chronic diseases. |

| de Souza et al. (2019)(31) | Longitudinal observational (2-year period). | Relationship between FOF and incident falls over 2 years. | 345 | Age: 71.0% were 60–75, 29.0% 75+. 65.2% female. 79.1% living with someone. Education in years: 4.61 (4.1). | 37.1% reported a history of falls (1 fall: 20%, 2+ falls: 17.1%). | FES-I | FES-I: 25.48 (11.9). | FOF was associated with a greater risk of recurrent falls. | FOF (i.e., FES-I scores) was associated with recurrent falls but not single falls over the study period. |

| Dierking et al. (2016)(21) | Longitudinal observational (10-year period) | Factors associated with FOF. | 1682 | Age: no FOF 78.7 (5.2), any FOF 79.6 (5.5), severe FOF 79.9 (5.6). 51.8% male. Sample all Mexican Americans. | No FOF: 20.9%, any FOF: 38.5%, severe FOF: 50.5%. | Single question, 4-point Likert scale | FOF prevalence (baseline): 56.7%, 15.6% severe. | FOF predictors: female sex, depression, chronic health conditions, falls history, higher MMSE score, IADL limitations, frequent familial interactions. | Severe FOF predictors: older age, female sex, depressive symptoms, chronic conditions, married. Frequent friend interaction and higher education were protective factors. |

| Donoghue et al. (2017)(36) | Longitudinal observational (2-year period) | Relationship between FOF, activity restriction, falls, and disability over 2 years. | 1621 | Age: 71.2 (5.2). 51.6% female. Education level evenly distributed. | One fall: 15.4%, 2+ falls: 7.4%. | Single question, yes/no responses followed by rating severity. | 26.3% reported FOF (20.9% somewhat afraid, 5.4% very afraid). | Reporting FOF at follow-up was predicted by reporting unsteadiness at baseline. | Self-reported unsteadiness associated with an increased risk of FOF, fear-related activity restriction, recurrent falls, and disability. |

| Ehrlich et al. (2019)(27) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between visual impairment, falls, and fall-related outcomes (e.g., FOF). | 11558 | 55.3% female. Collected data on race, education, and Medicaid beneficiary (yes/no). | Falls in last year: No visual impairment (13.5%), impairment: 20.6% | Single question, yes/no responses | Prevalence: 26.7% without visual impairment, 48.4% with impairment. | See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF was associated with visual impairment, older age, female sex, being Caucasian or Hispanic, higher BMI, and having more medical comorbidities. |

| El Fakiri et al. (2018)(9) | Cross-sectional observational | Prevalence of FOF and falls, & differences between ethnic groups. | 8892 | 54.6% aged 65–74, 45.4% aged 75+. 57.9% female. 89.8% Dutch, 1.9% Moroccan, 6.6% Surinamese, 2.1% Turkish. | 35.5% reported one fall in the last year, 14.7% reported 2+ falls in the last year. | Single question, 5-point Likert scale | FOF prevalence varied by ethnic group: Dutch (18%), Moroccan (36%), Surinamese (43%), Turkish (44%). | FOF associated with older age, female sex, living alone, living in a deprived neighborhood, low income, functional limitations, medical co-morbidity, poor perceived health, depressive symptoms, loneliness, physical inactivity, and BMI. | Ethnic minority groups experienced significantly more FOF than Dutch participants. This relationship was not seen for falls. See ‘Factors Associated with FOF’. |

| Gazibara et al. (2017)(37) | Cross-sectional observational | Factors associated with falls and FOF, and to quantify the prevalence of both. | 354 | Age: fallers = 75.3 (5.5), non-fallers = 73.3 (6.0). 72.7% female. Collected data on education, income, marital status, and living arrangement. | 15.8% fell in the past 6 months (1 fall: 78.6%, 2 falls: 10.7%, 3+ falls: 10.7%). | FES-I; single question, yes/no responses | Prevalence: fallers 28.6%, non-fallers 8.4%. FES-I scores: fallers 19.2 (13.1), non-fallers 14.2 (8.3). | FOF was associated with previous falls and female sex. | FOF higher in fallers. FOF was independently associated with falling. Women reported higher FES scores than men. FOF and female sex were associated with falls. |

| Hajek et al. (2018)(55) | Cross-sectional observational | Associations between FOF and psychosocial factors. | 7779 | Age: 64.5 (11.2). 51% female. Collected data on income and marital status. | N/A | Single question, yes/no responses | FOF prevalence: 18.0%. | FOF was associated with older age, female sex, low income, not being married, previous falls, depressive symptoms, and comorbidity. | Positive associations: perceived stress, negative effect. Negative associations: loneliness, life satisfaction, positive effect, optimism, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and self-regulation. |

| Harada et al. (2017)(28) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF and perceived neighborhood factors. | 238 | Age: 60.5% were 65–74, 39.5% 75+. 55% male. | 17.6% reported fall(s) in the previous year. | Single question, 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). | FOF data reported as continuous variable. Overall mean value: 2.3 (0.1). | Lower FOF was significantly correlated with higher step counts and locomotive moderate-vigorous physical activity. | In a multiple regression analysis, the interaction between crime safety and FOF was significantly associated with total and locomotive moderate-vigorous physical activity. This relationship was only seen in those with low FOF. |

| Hoang et al. (2016)(70) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF and both psychosocial and demographic factors. | 153 | Age: 72.00 (8.47). 55.6% female. 62.7% married, 8.5% living alone. 73.6% secondary school education or less. | 51% reported a fall history (1 fall: 30.1%, 2 falls: 14.4%, 3+ falls: 6.5%). | FES-I | 64% reported high FOF (FES-I scores 28+), 27.5% reported moderate FOF (FES-I scores 20–27). | See ‘Main Findings’. | There was a high prevalence of FOF overall. Positive associations with FOF: older age, female sex, depression, and falls history. Negative associations with FOF: ADL independence, general health perception, TUG performance. |

| James et al. (2017)(56) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationships between FOF, fluency in English, and mobility limitations (i.e., SPPB score 9 or less). | 1169 | Age: 78.7 (5.0). 60.1% female. 50.3% married. 43.6% household income $5000–$9999. 80.3% SPPB score 9 or less. Entire sample Mexican Americans. | 30.5% reported a fall in the last year (1 fall: 17.6%, 2 falls: 6.5%, 3+ times: 6.4%). | Single question, 4-point Likert scale. | FOF prevalence: 58.9%. | See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF was associated with previous falls, number of chronic conditions, and female sex. Those 80+ and not fluent in English reported FOF more often, though this relationship was lost after adjusting for covariates. |

| Jeon et al. (2017)(47) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF, falls history, and physical/clinical characteristics. | 101 | Age: 76.44 (8.18). 86.1% female. 58.4% living alone. | 54.5% reported previous falls (1 fall: 14.9%, 2+ falls: 39.6%). | Survey of Activities and FOF in the Elderly14 (SAFE). | SAFE scores: repeated fallers 26.15 (10.56), one-time fallers 17.73 (8.79), non-fallers 14.17 (6.65). | FOF had a significant association with fall history. | FOF was significantly higher in repeated fallers than one-time fallers, and higher in one-time fallers than non-fallers. Repeated fallers performed worse on physical testing than the other groups. |

| Johnson & McLeod (2016)(71) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF and perceived difficulty with grocery shopping. | 98 | Age: 82.4 (6.6). 83% female. 81% lived alone. 81.6% high school education or less. | Difficulty shopping: 30.8%, no difficulty shopping: 19.5% reported falls in the past 4 months. | FES; ABC. | FES scores: difficulty shopping 73.8 (21.5), no difficulty 84.3 (17.7); ABC scores: 57.8 (23.9) & 69.5 (22.6) respectively. | FOF was associated with difficulty grocery shopping. | Participants who reported difficulty grocery shopping reported significantly worse scores on the FES and ABC than those who reported no difficulty. |

| Lavedan et al. (2018)(66) | Longitudinal observational (2-year period). | Relationship between FOF, falls, and both demographic and clinical factors. | 640 | Age: 81.5 (5.0). 60.3% female. 50% married. 36.5% no education or illiterate. 40.3% living with spouse. | 25% fell in the last year (men: 21.7%, women: 27.1%). | Single question, yes/no responses. | FOF prevalence (baseline): 41.5%. | FOF was associated with previous falls, female sex, comorbidities, depression, and ADL disability. | 41.7% of subjects who reported FOF at baseline suffered a fall, though FOF did not predict FOF in a Cox regression analysis. |

| Lee et al. (2018)(29) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF outdoors and neighborhood characteristics. | 394 | Age: 65.4 (8.8). 55.58% female. 82.95% non-Hispanic white, 75.7% married or cohabiting, 67.02% annual income >$50000. | 6.75% reported a history of falling outdoors. | Single question, 4-point Likert scale. | FOF prevalence: 17.9%. | FOF was associated with both demographic and neighborhood characteristics. See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF was associated with older age, female sex, previous falls, difficulty walking 400m, many drainage ditches, and many broken sidewalks. Low traffic speed was negatively associated with FOF. |

| Lee et al. (2018)(48) | Cross-sectional observational | FOF was the outcome in a hierarchical regression model. Associations between FOF, demographic and clinical factors. | 7730 | Age: 59.7% were 65–74, 40.3% 75+. 59.2% female. 62.8% living with spouse, 65.8% 0–6 years education, 16.9% driving. | 23.3% reported a history of falling. | Single question, 3-point Likert scale. | FOF prevalence: 96.7% with fall history, 75.1% without fall history. | FOF associations: age 75+, female sex, low education, non-drivers, depression, comorbidities, and discomfort with neighborhood. Protective: social support, neighborhood facility access. | FOF had higher odds of being reported if participants were female or reported high discomfort with their neighborhood, both for those with and without a history of falls. |

| Litwin et al. (2018)(11) | Longitudinal observational (2–3 year study period). | Relationship between FOF and falls at follow-up. | 22533 | Age: 74.37 (6.94). 56.5% female. 64.14% partnered/married. 46.91% primary education. | Baseline: 5.50% reported falls. Follow-up: 10.75% reported falls. | Single question, yes/no responses | FOF prevalence: 12.26%. | FOF was associated with falls at follow-up. An interaction term (FOF x activity restriction) was negatively associated with falls at follow-up. | FOF predicted falls if mobility limitation was low to moderate. If mobility limitation was high, FOF was negatively associated with falls at follow-up. |

| Makino et al. (2018)(67) | Longitudinal observational (4-year period). | Incident disability between baseline and follow-up. | 4329 | Age: 71.8 (5.4). 51.5% female. | 14.1% reported falls in the last year. | Single question, 4-point Likert scale | FOF baseline prevalence: 43.3%. | FOF was present more often in those who developed disability and was higher in fallers than non-fallers. | The risk of incident disability across the study period was higher for those who reported FOF at baseline, regardless of their fall history. |

| Malini et al. (2016)(10) | Cross-sectional observational | Associations between FOF and demographic, clinical, and social variables. | 742 | Age: 76.7 (7.03). 70.2% female. 43.4% married/cohabiting. 80.3% 5+ years education. | 29.4% reported a history of falls (1–2 falls: 23.6%, 3+ falls: 4.9%). | FES-I | FOF prevalence: 51.9%. | FOF associations: older, female, widows, sedentary, past falls, fracture after falls, comorbidity, sensory impairment, walking aid use, (I)ADL dependency, worse grip/gait speed, depressive symptoms, worse cognition, and less social support. | FOF was associated with previous falls, taking 7+ medications, hearing impairment, ADL dependency, slow gait speed, worse self-rated health, and depressive symptoms in a logistic regression analysis. |

| Moreira et al. (2017)(41) | Cross-sectional observational | Associations between FOF and both demographic and clinical factors. | 4449 | Age: without DM = 73.5 (6.5), with DM = 73.0 (5.9). 66.1% female without DM, 67.1% with DM. | With DM: 28.1%, without DM: 34.1% reported falls in the previous 12 months. | FES-I | FOF prevalence: 53.6% without DM, 60.8% with DM. | FOF associated with female sex, chronic conditions, depression, visual impairment, worse health self-perception, previous falls, obesity, (I)ADL dependency, grip strength, and gait speed. | There were some differences in the factors associated with FOF for diabetics and non-diabetics. |

| Moreland et al. (2018)(30) | Cross-sectional observational | Associations between fall-related rehabilitation utilization and demographic and clinical factors. | 7062 | Age: 30% 65–69, 28% 70–74, 19% 75–79, 12% 80–84, 11% 85+. 55% female. 80% Caucasian. 27% living alone. | 31% reported fall(s) in the previous year (1 fall: 18%, 2+ falls: 13%). | FOF measure not clear. Appears to be a single question, yes/no responses | FOF prevalence: 26%. | FOF was associated with having received fall-related rehabilitation compared to not having received it. | Along with FOF, previous falls, poor SPPB scores (4 or less), and hip fracture history were associated with receiving fall-related rehabilitation. |

| Oh et al. (2017)(57) | Cross-sectional observational | FOF was the outcome in this study. | 7924 | Age: 73.51 (6.04). 60.9% female. 68.6% 0–6 years education. 65.6% living with spouse. | 21% reported experiencing fall(s) in the last year. | Single question, 3-point Likert scale | FOF prevalence: 75.6%. | See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF associated with being older and female, past falls, limited physical performance, comorbidities, IADL limitations, living without a spouse, low education, and low life satisfaction. |

| Park et al. (2017)(60) | Cross-sectional observational | Association between depressive symptoms and falls in the past year and prior 3 years. | 977 | Age: 77.26 (25.55). 55.9% female. Education (years): 7.45 (6.07). | Reported as a continuous variable. Falls within 1 year: 1.65 (1.39), within 3 years: 2.65 (8.63). | Single question, 5-point Likert scale | FOF data reported as continuous variable. Mean values for women and men were 2.55 and 1.85, respectively. | FOF was associated with depressive symptoms, anxiety, (I)ADL impairment, and previous falls. FOF was reported more by women than men. | Depressive symptoms were associated with both falls and FOF. The relationship between falls and depressive symptoms was stronger in women compared to men. |

| Pauelsen et al. (2018)(40) | Cross-sectional observational | FES-I scores, FOF, and fall consequence concerns. | 153 | Age: 78.0 (6.2). 63% female. 42% living alone. | 29% reported fall(s) in the past 6 months and 16% reported fall(s) in the past month. | FES-I; single question, 4-point Likert scale | FOF prevalence: 38%. On FES-I 39% had scores 23+. | See ‘Main Findings’. Fall-related concerns were reported significantly more by female participants. | FES-I scores were associated with functional status (SPPB score), morale (PGCM(73)), FOF, number of prescription medications (females only), concerns for injury from falling (males only). |

| Payette et al. (2016)(22) | Systematic review and meta-analysis. | Relationship between anxiety and fall-related psychological concerns. | 4738 | Overall mean age = 77.12. | N/A | N/A | N/A | FOF was correlated with anxiety and falls-efficacy/balance confidence. | FOF was related to anxiety and fall-related psychological concerns with both relationships having medium effect sizes. Anxiety explained 9.77% of FOF variance and 9.86% of falls-efficacy variance. |

| Peeters et al. (2018)(12) | Longitudinal observational (4-year period); cross-sectional analyses at baseline. | Association of FOF with measures of global cognition at baseline and at 4 years. | 4931 | Age: 62.9 (9.1). 54.3% female. Collected data on education level. | No FOF: 16.8%, FOF: 32.0% reported fall(s) in the past 12 months. | Single question, yes/no responses | FOF prevalence: 21.9%. | FOF was associated with worse cognition, older age, female sex, previous falls, comorbidities, and disability. | FOF at baseline was associated with decline in MoCA scores and this decline was greater for older participants (75+ vs. <75). |

| Peeters et al. (2019)(64) | Longitudinal observational (4-year period). | Influence of FOF at baseline on cognitive test results 4 years later. | 5174 | Age: 62.6 (8.9). 54.5% female. | No FOF: 16.6%, FOF: 31.1% reported fall(s) in the past year. | Single question, yes/no responses | FOF prevalence: 20.6%. | FOF was associated with older age, female sex, previous falls, depression, anxiety, co-morbidities, and disability. | FOF was associated with declines in delayed recall, colour trails (CCT) 1/2, and verbal fluency in adjusted models, marking decline in executive function. |

| Sakurai et al. (2017)(20) | Longitudinal observational (1-year period). | Subjective memory complaints (SMC) at baseline and at 1 year. | 406 | Age: 72.7 (4.9). 56.9% female. 24.9% living alone. Education in years: 12.8 (2.8). | N/A | Single question, yes/no responses | FOF prevalence: 24.6%. | FOF was reported more often by those who also reported SMC overall and at baseline. | FOF was associated with SMC at baseline and with incident SMC in those who did not report it at baseline. |

| Scarlett et al. (2019)(45) | Cross-sectional observational | Relationship between FOF and emotional regulation. | 117 | Age: 76 (6.8). 75% female. 100% Caucasian, 100% retired, 72.6% secondary or more education. 42.7% widowed. | 59% fell in previous 5 years (once = 20%, 2+ = 39%). | FES-I; FFABQ | FES-I: 26.73 (10.4). FFABQ: 12.42 (13.3). | FOF (i.e., FES-I, FFABQ scores) was positively correlated with difficulties in emotional regulation (i.e., DERS scores). | FES-I scores related to older age and depression in a significant hierarchical regression model. FFABQ scores in this model were only related to older age. |

| Shirooka et al. (2017)(46) | Cross-sectional observational | Association between FOF and cognition in frail vs. non-frail older adults. | 483 | Age: 73.3 (5.1). 68.3% female. 60.8% had 10+ years of education. | 20.3% reported fall(s) in the past year. | Single question with yes/no responses | FOF prevalence: 31.5%. | FOF was associated with older age, female sex, and previous falls. For frail participants, better cognition was associated with FOF. | Cognitive impairment (specifically in MMSE attention and calculation scores) was associated with the absence of FOF in frail older adults. |

| Shoene et al. (2019)(23) | Systematic review | Relationship between FOF and QOL. | 29029 | Age: 75.6 (6.1). 78% female. | N/A | N/A | N/A | Lower FOF was associated with higher QOL, independent of FOF measure or previous falls. | FOF associated with lower QOL. FOF should not be considered solely as a byproduct of previous falls. |

| Tomita et al. (2015)(38) | Cross-sectional observational | FOF was the dependent variable in this study. | 278 | Age: 72.6 (5.2). 100% female. | 23% reported fall(s) in the previous year. | Single question, yes/no responses | FOF prevalence: 36.3%. | FOF increased non-significantly with older age (75+ vs. 65–74). See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF associated with worse physical performance (i.e., longer five-time chair stand, TUG, and 6-m walking time, weaker grip strength). |

| Tomita et al. (2018)(72) | Cross-sectional observational | FOF was the dependent variable in this study. | 844 | Age: males = 70.1 (6.4), females = 69.8 (6.1). 58.5% female. | 16% had fall(s) in the previous year (males: 13.7%, females: 17.6%). | Single question, yes/no responses | Prevalence: 26.9% males, 43.3% females. | FOF associated with older age, female sex, previous falls, lumbar and/or knee pain, co-morbidities, worse five-time chair stand. | FOF associated with older age, previous falls, and lumbar and/or knee pain for both males and females. FOF associated with five-times chair stand time for females. |

| Uemura et al. (2015)(39) | Longitudinal observational (15-month period). | Relationship between MCI and the development of FOF over the study period. | 1700 | Age: 70.8 (4.7). 62.1% male. Education, and living arrangement reported by subgroup. | Never FOF: 9.5%, Developed FOF: 26.1% reported fall incidents. | Single question, 4-point Likert scale. | Incidence: 26.5%. | FOF more likely if: older, female, incident falls, low education, low cognition, slower gait and TUG times, depressive symptoms, walking aid use, MCI, and poor self-rated health. | Incident FOF associated with age, female sex, low education, MCI, incident falls, low gait speed, depressive symptoms, and poor self-rated health. |

| Vitorino et al. (2017)(32) | Cross-sectional observational | Association between FOF and both demographic and clinical factors. | 170 | Age: 57.1% were 60–69, 42.9% were 70+. 67.6% female. 90.6% had less than 8 years of education. 54.1% married or with a partner. | 76.5% had fall(s) (1 fall: 20%, 2+ falls: 56.5%). 46.1% of reported falls within last year. | FES-I | FES-I: 29.5 (10.2). 66.5% reported high FOF (i.e., 23+ on the FES-I). | See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF associated with older age, female sex, previous falls, and worse self-assessment of health in a multiple linear regression model. The model explained 37% of FOF variance. |

| Vitorino et al. (2019)(26) | Cross-sectional observational | FOF compared between the two study sites (i.e., Brazil and Portugal). | 340 | Age: 72.00 (7.69), 74.40% female. 48.20% married or with a partner. | 74.7% reported previous fall(s). 38.5% of reported falls within last year. | FES-I | Prevalence (i.e., FES-I score 23+): 72.4%; Portuguese site 78.2%, Brazil site 66.5%. | See ‘Main Findings’. | FOF associations: Brazil = age 76+, female sex; Portugal = daily medication use, previous falls, vision problems. FES-I scores were higher in Portugal than Brazil. |

All values are numerical counts, percentages or means with standard deviations.

FOF = Fear of Falling; FES = Falls Efficacy Scale;(16) ABC = Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale;(42) PBF = percent body fat; SF-36 = Short Form Health Survey;(53) ADL = Activities of Daily Living; TUG = Timed Up and Go Test;(49) SPPB = Short Physical Performance Battery;(50) PGCM = Philadelphia Geriatric Center Morale Scale;(73) MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination;(62) MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment;(63) FFABQ = Fear of Falling Avoidance Behavior Questionnaire;(44) DERS = Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale;(59) MCI = mild cognitive impairment; BMI = body mass index; QOL = quality of life; DM = diabetes mellitus; PIGD = postural instability/gait disturbance

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of article selection process

Study Design

The majority of studies (30/46, 65.2%) used a cross-sectional study design. Longitudinal study designs (14/46, 30.4%) were the next most common approach. These longitudinal studies ranged from one(20) to 10 years(21) in duration. Two systematic reviews (4.3%) were also included.(22,23)

Included studies took place in whole or in part within 20 countries/regions and four continents (Asia, Europe, and both North and South America). The specific locations (listed alphabetically) and the number of studies that took place in each were: Albania (3), Brazil (8), Canada (4), Colombia (3), Europe (2), Germany (1), Hong Kong (1), Ireland (3), Israel (2), Netherlands (1), Norway (1), Portugal (1), Serbia (1), South Korea (6), Spain (2), Sweden (1), Taiwan (2), United Kingdom (1), USA (7), and Vietnam (1). Five studies included participants from multiple countries/regions.(11,13,24–26) The two systematic reviews(22,23) included articles from multiple countries. FOF was commonly found in older populations across the world. In studies that used a single question for detection, its prevalence ranged from 25.89% (SD 10.08) in studies done in Europe to 45.68% (SD 23.34) for those performed in Asia (p = .097).

Sample Characteristics

The 44 primary studies reviewed included a total of 124,841 participants. Sample sizes for these 44 studies ranged from 98 to 22,533 with a mean (SD) value of 3,448 (5643.8). When categorized by size, 10 studies had < 250 participants, 12 had 250–1,000, and 22 had > 1,000 participants. Both systematic reviews(22,23) included data from over 1,000 participants.

Age

An overall mean age could not be calculated as the required information was not provided in seven studies.(9,26–32) Categorized by the mean age of participants, three of the studies predominately included participants aged 60–65, six with those aged 65–70, 16 with participants aged 70–75, 11 with those 75–80, and three with participants > 80.

Biological Sex

Most studies (38/46, 82.6%) had predominantly (>50%) female participants, with three studies(33,34,38) including only women. Six studies(8,14,21,28,36,38) had predominantly male participants. Two studies(22,25) did not report on the overall sex proportions of participants. The influence of gender identity or role was not examined.

Fear of Falling Measurement

Most primary studies (29/44, 65.9%) used a single question, which varied in wording and/or scoring, to detect FOF. Nineteen studies used the wording “Are you afraid of falling?”, while others specified a time period (e.g., “Have you worried about falling in the last four months?”) or environment (e.g., “I am worried about falling when I walk in my neighborhood”). Ten of the studies that used a single question scored FOF on a Likert scale (e.g., never, rarely, sometimes, or often). Five studies(27,34,35,36,37) asked about avoiding certain behaviours/activities as a result of FOF, and one inquired about perceived consequences of falling that could contribute to FOF.(40)

The Falls Efficacy Scale (FES) was used in 15 studies. Scores on this instrument range from 18–64 with higher scores representing greater FOF,(16) though the thresholds used for defining the presence or severity of FOF varied between studies. For example, Auais et al.(13) stated that FES scores of 16–19 indicated no/low FOF, while 20–27 denoted moderate and ≥ 28 a high degree of FOF. Aibar-Almazan et al.(33) stated that values > 26 placed an individual at higher risk of falling. Malini et al.,(10) de Souza Moreira et al.,(41) and Vitorino et al.(26,32) all used a FES score cut-off of 23 to determine FOF. Vitorino et al.(26,32) referred to these scores as indicating a high FOF.

The mean percent prevalence of FOF found in studies was significantly lower if a single question was used (mean ± SD percentage = 37.38 ± 19.53) compared to those that used the FES (mean ± SD percentage = 52.31 ± 22.29; t = −20.39, p <.05).

Other less commonly utilized instruments used to measure FOF included the Activities-Specific Balance Confidence Scale(42) (n = 3), Outdoor Fall Questionnaire(43) (n = 1), Survey of Activities and Fear of Falling in the Elderly(15) (n = 1), and Fear Avoidance Behavior Questionnaire(44) (n = 1). Six studies(33,37,40,45,46,47) used multiple approaches.

Factors Associated with FOF

Table 2 provides a summary of which studies found associations between FOF and the different categories of factors outlined below.

TABLE 2.

Summary of Factors Associated with FOF

| Category | Associated Factor | Articles Reporting on Association (First Author Listed) |

|---|---|---|

| Socio-demographic | Older Age | Chang,(8) Chippendale,(69) Choi,(35) Dierking,(21) Ehrlich,(27) El Fakiri,(9) Hajek,(55) Hoang,(70) James,(56)a Lavedan,(66) a Lee,(29,48) Malini,(10) Oh,(57) Peeters,(12,64) Scarlett,(45) Shirooka,(46) Tomita,(37a,72) Uemura,(39) Vitorino(26,32) |

| Female Sex | Auais,(13) Chang,(8) Chippendale,(69) Choi,(35) Dierking,(21) Ehrlich,(27) El Fakiri,(9) Gazibara,(37) Hajek,(55) Hoang,(70) James,(56) Lavedan,(66) Lee,(29,48) Malini,(10) Moreira,(41) Oh,(57) Park,(60) Pauelsen,(40) Peeters,(12,64) Shirooka,(46) Tomita,(72) Uemura,(39) Vitorino(26,32) | |

| Lower Education | Chang,(8)a Chippendale,(69)a Choi,(35) Dierking,(21)a El Fakiri,(9) Hoang,(70)a Lee,(48) Malini,(10)a Moreira,(41) Oh,(57) Peeters,(12,64) Uemura(39) | |

|

| ||

| Physical Performance | Aibar-Almazan,(33) Bjerk,(54) Chang,(8) Chippendale,(69)a Dierking,(21) El Fakiri,(9) Hajek,(55) Harada,(28) Johnson,(71) Lavedan,(66) Lee,(29) Makino,(67) Malini,(10) Moreira,(41) Oh,(57) Park,(60) Pauelsen,(40) Peeters,(12,64) Tomita,(38,72) Uemura(39) | |

|

| ||

| Health | Comorbidity | Aibar-Almazan,(33) Auais,(13,24,25) Bjerk,(54) Chang,(8) Choi,(34,35) Dierking,(21) Donoghue,(36) Ehrlich,(27) El Fakiri,(9) Hajek,(55) James,(56) Lavedan,(66) Lee,(48) Malini,(10) Moreira,(41) Oh,(57) Peeters,(12,64) Shoene,(23) Tomita,(72) Vitorino(26) |

| Sensory Impairment | Choi,(34) Ehrlich,(27) Gazibara,(37) James,(56) Malini,(10) Oh,(57) Vitorino(26) | |

| Falls | Aibar-Almazan,(33) Allali,(66)a Chang,(8,14) Chippendale,(69) Choi,(34) de Souza,(31) Dierking,(21) Gazibara,(37) Hajek,(55) Hoang,(70) James,(56) Jeon,(47) Lavedan,(66) Lee,(29) Litwin,(11) Malini,(10) Moreira,(41) Oh,(57) Peeters,(12,64) Shirooka,(46)a Tomita,(72)a Uemura,(39) Vitorino(25,31) | |

| Quality of Life | Bjerk,(54) Chang,(8) Shoene(23) | |

|

| ||

| Psychological | Mood/Emotion | Aibar-Almazan,(33) Bjerk,(54) Chang,(8) Chippendale,(69)a Choi,(34,35) Dierking,(21) El Fakiri,(9) Hajek,(55) Hoang,(70) Lavedan,(66) Lee,(48) Malini,(10) Moreira,(41) Park,(60) Pauelsen,(40) Payette,(22) Peeters,(64) Scarlett,(45) Uemura(39) |

| Cognition | Choi,(34) Dierking,(21) Litwin,(11) Malini,(10) Moreira,(41) Peeters,(12,64) Shirooka,(46) Uemura(39) | |

|

| ||

| Social/Environmental | Auais,(24) Dierking,(21) El Fakiri,(9) Harada,(28) Lee,(29,48) Malini(10) | |

Non-significant association.

Sociodemographics

Female sex and older age were consistently associated with FOF. All 26 studies reporting on FOF and female sex found a positive association. Most studies (20/23, 87.0%) reporting on age and FOF found a positive association (note: some dealt with age as a continuous variable while others used age categories). Having lower levels of education was associated with FOF in most studies (8/13, 61.5%) examining this relationship. Associations with other demographic variables such as living alone and/or having a low income,(9) being a non-driver,(48) and being widowed(10) were noted in select studies.

Physical Performance and Disability Measures

Most studies (21/22, 95.5%) reporting on FOF and physical performance and/or disability found positive associations between the presence of worse physical performance and/or greater degrees of disability and FOF. The performance measures examined included the timed up-and-go (TUG),(45) 6-metre walk time, chair stands, grip strength, gait speed, and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).(50) Disability measures included both basic and instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., Katz Index for ADLs,(51) Lawton and Brody Scale for IADLs(52)). The Physical Functioning subscale of the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36)(53) was also used in three studies.(8,54,55) In all three worse scores were associated with FOF.

Health Factors

Comorbidity

All (24/24) studies examining this relationship found an association between medical morbidities and FOF. These studies either looked at the relationship with specific conditions (e.g., hypertension) or the presence of one or more morbidities.(56) Obesity was found to be associated with FOF by two studies(27,41) and one study(33) also found an association between FOF and sarcopenic obesity.

Sensory Impairment

Six studies(10,26,27,37,56,57) found associations between sensory impairment (i.e., hearing, vision) and FOF. One study(34) used a combined measure of sensory abilities and found an association between FOF and worse sensory function.

Falls

Most studies (23/26, 88.5%) providing data found an association between prior or incident falls and FOF.

Quality of Life

Two studies(8,54) found an association between worse quality of life (QOL) measured by the SF-36 and FOF. One systematic review(23) reported that FOF was associated with lower QOL regardless of the FOF measure used or whether there were prior falls.

Psychological and Cognitive Status

Psychological Status

Nearly all studies (19/20, 95.0%) reporting on this found positive associations between FOF and the presence of depression and/or anxiety. The majority of these studies (14/20, 70.0%) examined the relationship with depressive symptoms measured by questionnaires (e.g., the Geriatric Depression Scale(58)). Scarlett et al.(45) used the Difficulties in Emotional Regulation Scale (DERS)(59) and found worse emotional regulation to be associated with FOF. One systematic review and meta-analysis(22) found a significant, positive association between anxiety and both FOF and other fall-related concerns. Park et al.(60) found a positive association between FOF and anxiety as measured by the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI).(61)

Cognitive Status

Twenty-seven studies in our review examined cognition. In the majority of these studies (18/27, 66.7%) cognition was solely used for decisions on whether to include or exclude potential participants. The most commonly used measures were the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE)(62) (n = 18) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA)(63) (n = 3). In six studies,(10–12,34,39,64) FOF was associated with worse cognition, while in two(21,46) it was related to better cognition. One study(41) found FOF to be associated with worse cognition only in participants who had diabetes mellitus.

Other Psychological Factors

Hajek et al.(55) found that greater perceived stress, negative effect, and loneliness had positive associations with FOF, while higher levels of life satisfaction, positive effect, optimism, self-efficacy, self-esteem, and self-regulation showed negative associations. Oh et al.(57) found lower life satisfaction to be associated with FOF. Pauelsen et al.(40) found lower morale to be associated with FOF.

Social and Environmental Relationships

The associations found between social or environmental factors and FOF were generally limited to individual studies. Auais et al.(24) found that FOF was associated with decreased life-space mobility. El Fakiri et al.(9) reported that both living alone and in a deprived neighbourhood were associated with FOF. Harada et al.(28) showed a relationship between FOF and rates of crime in one’s neighbourhood. Lee et al.(29) found that the presence of drainage ditches and broken sidewalks was associated with FOF, while lower traffic speeds were protective. Lee, Oh, and Hong(48) reported that discomfort with one’s neighbourhood was associated with FOF, while more social support and access to neighbourhood facilities were protective. Finally, Malini et al.(10) showed that less social support was associated with FOF, while Dierking et al.(21) found that frequent interaction with friends was protective.

Outcomes Predicted by FOF

Falls

Three prospective longitudinal studies(11,31,65) found that baseline FOF predicted incident falls. Conversely, Lavedan et al.(66) did not find FOF at baseline to significantly predict falls over a two-year study period.

Mortality

Chang et al.(14) reported that FOF was associated with a higher risk of mortality over a seven-year period.

Functional Decline

Auais et al.(25) found that FOF predicted incident mobility disability and the development of worse physical performance. Makino et al.(67) showed that FOF predicted incident disability. Choi et al.(34) demonstrated that FOF predicted greater functional decline.

Impaired Cognition

Peeters et al.(12) found that FOF predicted greater decline in global cognition as measured by the MoCA. In a subsequent paper, Peeters et al.(64) reported that cognitive decline associated with FOF was most evident on the Colour Trails Test (e.g., selective attention, executive functioning), delayed recall (i.e., memory), and verbal fluency (i.e., language, executive functioning). Sakurai et al.(20) found that FOF predicted incident subjective memory complaints.

DISCUSSION

Our scoping review confirmed that FOF is a highly prevalent issue associated with significant adverse outcomes in older adults and added a number of novel observations. The factors most consistently associated with the presence of FOF in this review were older age, female sex, previous falls, worse physical performance, and depressive symptoms. These findings are largely consistent with previous research.(7,18) Many of the cross-sectional studies that identified these risk factors used multivariate regression models to identify the relative significance of individual factors or analyses stratified by sex(8,40) or fall history.(29) These analyses, while valuable, are limited by the cross-sectional methodology used, which restricts the conclusions that can be made about potential causality.

The longitudinal studies in our review reported that essentially the same risk factors for FOF as the cross-sectional studies mentioned were operant,(21) though specific associations with self-reported unsteadiness(36) and mild cognitive impairment(39) were also identified. These studies also reported that FOF predicted adverse outcomes such as future falls(11,31,65) and declines in both physical(34,67) and cognitive(12,64) functioning, demonstrating the potential importance of identifying those at risk of FOF and intervening. Further longitudinal studies investigating FOF are needed for a better understanding of how best to detect FOF and to help develop effective prevention and intervention strategies.

Our review found that studies that measured FOF with a single question had significantly lower FOF prevalence rates than those using the FES. While single-question approaches with yes/no responses have demonstrated good test/retest reliability,(68) they have been criticized for not being able to detect milder—though still clinically important—degrees of concern. This makes delineating the relationship between FOF and activity restriction less clear as a result.(7,17) Some studies using a single question include a Likert scale for responses.(28) Less is known about the reliability of the responses obtained in this manner. The FES focuses on the person’s self-efficacy or confidence in avoiding falls while doing various activities. This measure has similarly shown good test/retest reliability,(16) and its continuous scoring allows for more nuanced results. However, the FES has been criticized for the use of different thresholds in operationally defining FOF, as we saw in our review, as well as the concern that fall self-efficacy does not fully map to the concept of FOF.(7) Previous studies that have compared FOF measures have determined that self-efficacy scales like the FES and ABC are more robust, sensitive measures of FOF.(17,65) Our results are in agreement that the FES is likely more sensitive for detecting FOF than single questions, though further studies comparing the predictive validity of single questions to the FES and other FOF measurements are required.

The current review identified limitations in the FOF research done to date. Alongside the above mentioned relative lack of longitudinal studies, inconsistency in the measures used to detect FOF also presents a challenge in deriving conclusions from the existing literature. The time limits placed on measures of FOF and falls (e.g., “Have you worried about falling in the last four months?”) also present challenges in comparing studies. Consensus on which approach to take in detecting FOF and the scoring used would help in addressing this. Other areas identified for future research would be the influence of gender (in contrast to biological sex) on FOF, and the relationship between FOF and cognition. For the latter, this remains under-investigated despite the known links between cognition and fall risk. Similarly, the relationship between FOF and its management with psychological, social, and environmental factors requires additional research. While the studies reviewed came from North and South America, Asia, and Europe (indicating that FOF is a worldwide issue), no recent papers were identified from either Africa or Australia. An unexplored area of inquiry would be critically searching for differences between regions and cultures in the prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of FOF.

The current review has a number of limitations. We only examined studies conducted between April 2015 and March 2020, and our search was limited to the PubMed database. Studies that focused on FOF interventions or disease-specific populations were excluded. Our findings apply specifically to community-dwelling older adults. This review also did not include formalized quality assessments of the studies included for review, though study limitations, such as the identification of potential sources of bias, were included in the data extraction process.

CONCLUSION

FOF is common among community-dwelling older adults and is associated with adverse health outcomes. This scoping review provides a summary of recent observational studies on FOF that focused on factors associated with FOF, measurements used to quantify FOF, and gaps in the literature that could be addressed in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the Brenda Strafford Centre on Aging for their financial support in covering the article’s processing fee.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that no conflicts of interest exist.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhala RP, O’Donnell J, Thoppil E. Ptophobia: phobic fear of falling and its clinical management. Phys Ther. 1982;62(2):187–90. doi: 10.1093/ptj/62.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Powell L. Fear of falling and low self-efficacy: a cause of dependence in elderly persons. J Gerontol. 1993;48(Spec Issue):35–38. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.Special_Issue.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tinetti ME, Speechley M, Ginter SF. Risk factors for falls among elderly persons living in the community. N England J Med. 1988;319(26):1701–07. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198812293192604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tideiksaar R. Falling in old age: Its prevention and treatment. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tideiksaar R. Falls in older people: Prevention and management. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whipple MO, Hamel AV, Talley KM. Fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults: a scoping review to identify effective evidence-based interventions. Geriatr Nurs. 2018;39(2):170–77. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung D. Fear of falling in older adults: comprehensive review. Asian Nurs Res. 2008;2(4):214–22. doi: 10.1016/S1976-1317(09)60003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang HT, Chen HC, Chou P. Factors associated with fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults in the Shih-Pai study in Taiwan. PloS one. 2016;11(3):e0150612. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Fakiri F, Kegel AA, Schouten GM, et al. Ethnic differences in fall risk among community-dwelling older people in the Netherlands. J Aging Health. 2018;30(3):365–85. doi: 10.1177/0898264316679531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malini FM, Lourenço RA, Lopes CS. Prevalence of fear of falling in older adults, and its associations with clinical, functional and psychosocial factors: the Frailty in Brazilian Older People-Rio de Janeiro Study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(3):336–44. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litwin H, Erlich B, Dunsky A. The complex association between fear of falling and mobility limitation in relation to late-life falls: a SHARE-based analysis. J Aging Health. 2018;30(6):987–1008. doi: 10.1177/0898264317704096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peeters G, Leahy S, Kennelly S, et al. Is fear of falling associated with decline in global cognitive functioning in older adults: Findings from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2018;19(3):248–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auais M, Alvarado BE, Curcio CL, et al. Fear of falling as a risk factor of mobility disability in older people at five diverse sites of the IMIAS study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;66:147–53. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang HT, Chen HC, Chou P. Fear of falling and mortality among community-dwelling older adults in the Shih-Pai study in Taiwan: a longitudinal follow-up study. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(11):2216–23. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lachman ME, Howland J, Tennstedt S, et al. Fear of falling and activity restriction: the survey of activities and fear of falling in the elderly (SAFE) J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1998;53(1):P43–P50. doi: 10.1093/geronb/53B.1.P43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tinetti ME, Richman D, Powell L. Falls efficacy as a measure of fear of falling. J Gerontol. 1990;45(6):P239–P243. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.P239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenberg SA. Analysis of measurement tools of fear of falling for high-risk, community-dwelling older adults. Clin Nurs Res. 2012;21(1):113–30. doi: 10.1177/1054773811433824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Denkinger MD, Lukas A, Nikolaus T, et al. Factors associated with fear of falling and associated activity restriction in community-dwelling older adults: a systematic review. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;23(1):72–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakurai R, Suzuki H, Ogawa S, et al. Fear of falling, but not gait impairment, predicts subjective memory complaints in cognitively intact older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(7):1125–31. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dierking L, Markides K, Al Snih S, et al. Fear of falling in older Mexican Americans: a longitudinal study of incidence and predictive factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2560–65. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Payette MC, Belanger C, Léveillé V, et al. Fall-related psychological concerns and anxiety among community-dwelling older adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS one. 2016;11(4):e0152848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoene D, Heller C, Aung YN, et al. A systematic review on the influence of fear of falling on quality of life in older people: is there a role for falls? Clin Interv Aging. 2019;14:701. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S197857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Auais M, Alvarado B, Guerra R, et al. Fear of falling and its association with life-space mobility of older adults: a cross-sectional analysis using data from five international sites. Age Ageing. 2017;46(3):459–65. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afw239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Auais M, French S, Alvarado B, et al. Fear of falling predicts incidence of functional disability 2 years later: a perspective from an international cohort study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2018;73(9):1212–25. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glx237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vitorino LM, Marques-Vieira C, Low G, et al. Fear of falling among Brazilian and Portuguese older adults. Int J Older People Nurs. 2019;14(2):e12230. doi: 10.1111/opn.12230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ehrlich JR, Hassan SE, Stagg BC. Prevalence of falls and fall-related outcomes in older adults with self-reported vision impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(2):239–45. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harada K, Park H, Lee S, et al. Joint association of neighborhood environment and fear of falling on physical activity among frail older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2017;25(1):140–48. doi: 10.1123/japa.2016-0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee S, Lee C, Ory MG, et al. Fear of outdoor falling among community-dwelling middle-aged and older adults: the role of neighborhood environments. Gerontologist. 2018;58(6):1065–74. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moreland BL, Durbin LL, Kasper JD, et al. Rehabilitation utilization for falls among community-dwelling older adults in the United States in the National Health and Aging Trends Study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2018;99(8):1568–75. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Souza AQ, Pegorari MS, Nascimento JS, et al. Incidence and predictive factors of falls in community-dwelling elderly: a longitudinal study. Cienc Saude Colet. 2019;24(9):3507–16. doi: 10.1590/1413-81232018249.30512017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vitorino LM, Teixeira CA, Boas EL, et al. Fear of falling in older adults living at home: associated factors. Rev Esc Enferm USP. 2017;51 doi: 10.1590/s1980-220x2016223703215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aibar-Almazán A, Martínez-Amat A, Cruz-Díaz D, et al. Sarcopenia and sarcopenic obesity in Spanish community-dwelling middle-aged and older women: association with balance confidence, fear of falling and fall risk. Maturitas. 2018;107:26–32. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Choi K, Jeon GS, Cho SI. Prospective study on the impact of fear of falling on functional decline among community dwelling elderly women. Int J Env Res Pub Health. 2017;14(5):469. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14050469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi K, Ko Y. Characteristics associated with fear of falling and activity restriction in South Korean older adults. J Aging Health. 2015;27(6):1066–83. doi: 10.1177/0898264315573519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Donoghue OA, Setti A, O’Leary N, et al. Self-reported unsteadiness predicts fear of falling, activity restriction, falls, and disability. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2017;18(7):597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gazibara T, Kurtagic I, Kisic-Tepavcevic D, et al. Falls, risk factors and fear of falling among persons older than 65 years of age. Psychogeriatrics. 2017;17(4):215–23. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tomita Y, Arima K, Kanagae M, et al. Association of physical performance and pain with fear of falling among community-dwelling Japanese women aged 65 years and older. Medicine. 2015;94(35) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000001449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uemura K, Shimada H, Makizako H, et al. Effects of mild cognitive impairment on the development of fear of falling in older adults: A prospective cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(12):1104.e9–1104.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pauelsen M, Nyberg L, Röijezon U, et al. Both psychological factors and physical performance are associated with fall-related concerns. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2018 Sep 1;30(9):1079–85. doi: 10.1007/s40520-017-0882-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Souza Moreira B, Sampaio RF, Diz JB, et al. Factors associated with fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults with and without diabetes mellitus: findings from the Frailty in Brazilian Older People Study (FIBRA-BR) Exp Gerontol. 2017;89:103–11. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Powell LE, Myers AM. The activities-specific balance confidence (ABC) scale. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(1):M28–M34. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50A.1.M28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chippendale T, Knight R, An MS, et al. Development and validity of the outdoor falls questionnaire (OFQ) Am J Occup Ther. 2016;70(4 Suppl 1):7011500010p1. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2016.70S1-RP304D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Velozo CA, Peterson EW. Developing meaningful fear of falling measures for community dwelling elderly. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80(9):662–73. doi: 10.1097/00002060-200109000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scarlett L, Baikie E, Chan SW. Fear of falling and emotional regulation in older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(12):1684–90. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2018.1506749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shirooka H, Nishiguchi S, Fukutani N, et al. Cognitive impairment is associated with the absence of fear of falling in community-dwelling frail older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2017;17(2):232–38. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeon M, Gu MO, Yim J. Comparison of walking, muscle strength, balance, and fear of falling between repeated fall group, one-time fall group, and nonfall group of the elderly receiving home care service. Asian Nurs Res. 2017;11(4):290–96. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee S, Oh E, Hong GR. Comparison of factors associated with fear of falling between older adults with and without a fall history. Int J Env Res Pub Health. 2018;15(5):982. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39(2):142–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, et al. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–M94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.M85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katz S, Downs TD, Cash HR, et al. Progress in development of the index of ADL. Gerontologist. 1970;10(1 Part 1):20–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/10.1_Part_1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3 Part 1):179–86. doi: 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stewart AL, Ware JE. Measuring functioning and well-being: the medical outcomes study approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bjerk M, Brovold T, Skelton DA, et al. Associations between health-related quality of life, physical function and fear of falling in older fallers receiving home care. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):253. doi: 10.1186/s12877-018-0945-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hajek A, Bock JO, König HH. Psychological correlates of fear of falling: Findings from the German Aging Survey. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(3):396–406. doi: 10.1111/ggi.13190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.James EG, Conatser P, Karabulut M, et al. Mobility limitations and fear of falling in non-English speaking older Mexican-Americans. Ethnic Health. 2017;22(5):480–89. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2016.1244660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oh E, Hong GR, Lee S, et al. Fear of falling and its predictors among community-living older adults in Korea. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(4):369–78. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1099034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yesavage JA. Geriatric depression scale. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24(4):709–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2004;26(1):41–54. doi: 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Park Y, Paik NJ, Kim KW, et al. Depressive symptoms, falls, and fear of falling in old Korean adults: the Korean Longitudinal Study on Health and Aging (KLoSHA) J Frailty Aging. 2017;6(3):144–47. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2017.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Spielberger CD. State-Trait anxiety inventory. The Corsini Encyclopedia Of Psychology. 2010 Jan;30:1. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Folstein MF, Robins LN, Helzer JE. The mini-mental state examination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40(7):812. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790060110016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peeters G, Feeney J, Carey D, et al. Fear of falling: a manifestation of executive dysfunction? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(8):1275–82. doi: 10.1002/gps.5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Allali G, Ayers EI, Holtzer R, et al. The role of postural instability/gait difficulty and fear of falling in predicting falls in non-demented older adults. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2017;69:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lavedán A, Viladrosa M, Jürschik P, et al. Fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults: a cause of falls, a consequence, or both? PLoS one. 2018;13(3):e0194967. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0194967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Makino K, Makizako H, Doi T, et al. Impact of fear of falling and fall history on disability incidence among older adults: Prospective cohort study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2018;33(4):658–62. doi: 10.1002/gps.4837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Oh-Park M, Xue X, Holtzer R, et al. Transient versus persistent fear of falling in community-dwelling older adults: incidence and risk factors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(7):1225–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03475.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chippendale T, Lee CD. Characteristics and fall experiences of older adults with and without fear of falling outdoors. Aging Ment Health. 2018;22(6):849–55. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2017.1309639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoang OT, Jullamate P, Piphatvanitcha N, et al. Factors related to fear of falling among community-dwelling older adults. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(1–2):68–76. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnson CS, McLeod KM. Relationship between fear of falling and perceived difficulty with grocery shopping. J Frailty Aging. 2017;6:33–36. doi: 10.14283/jfa.2016.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tomita Y, Arima K, Tsujimoto R, et al. Prevalence of fear of falling and associated factors among Japanese community-dwelling older adults. Medicine. 2018;97(4) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000009721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kent D, Kastenbaum R, Sherwood S, et al. Research planning and action for the elderly: the power and potential of social science. New York, NY: Behavioral Publications; 1972. [Google Scholar]