Abstract

Sexual minority stressors (e.g., stigma consciousness, internalized homophobia, discrimination) are posited to contribute to higher prevalence of overeating and binge eating among sexual minority women (SMW) relative to heterosexual women. Few studies have examined psychosocial mediators of the associations of minority stressors with overeating and binge eating in SMW. Using data from a diverse, community-based sample of SMW, we examined these associations, including the potential mediating effects of past-year depression. We also conducted exploratory analyses to determine if the associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating differed by sexual identity or by race and ethnicity.

The sample included 607 SMW (38.2% White, 37.1% African American; 24.7% Latina) with a mean age of 39.7 years. Approximately 17% and 9% of SMW reported overeating and binge eating, respectively, in the past 3 months. Greater stigma consciousness was associated with higher odds of overeating (AOR 1.31, 95% CI = 1.03–1.66). We found no significant associations between minority stressors and binge eating. Past-year depression did not mediate associations between minority stressors and overeating or binge eating. Although we found no sexual identity differences, stigma consciousness among Latina SMW was associated with higher odds of overeating relative to White SMW (AOR 1.95, 95% CI = 1.21–3.12) and African American SMW (AOR 1.99, 95% CI = 1.19–3.31).

Findings highlight the importance of screening SMW for stigma consciousness as a correlate of overeating and considering racial and ethnic differences in overeating and binge eating in this population.

Keywords: Sexual minority, binge eating, overeating, minority stress, depression, mediation

Introduction

Overeating and binge eating are important public health concerns as people who engage in these behaviors are at increased risk for negative health outcomes. Overeating is defined as the consumption of a large quantity of food within a two-hour time period.1 Binge eating is characterized by the recurrent consumption of a large quantity of food (i.e., overeating) with loss of control (LOC) over eating.1,2 Individuals who overeat and/or binge eat have a higher risk of developing chronic health conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, and obesity.3–5 Among those who binge eat, the experience of LOC is considered more significant than the amount of food consumed.6 Individuals who engage in binge eating experience significant distress,7 impairment,8 and negative psychological outcomes,9 independent of overeating without LOC, highlighting differences in health outcomes severity between overeating and binge eating.10 However, in a longitudinal study of young adults, participants who reported both overeating and binge eating in adolescence were more likely to use marijuana and other substances than those who did not—indicating the importance of examining both overeating and binge eating simultaneously.11

Compared to men, women report greater eating-disorder symptomology (including dietary restraint, eating concern, shape concern, and weight concern) and depressive symptoms.12 Because of this, an examination of the associations of sexual minority stressors and past-year depression with overeating and binge eating among women is warranted. Overeating and binge eating are not uncommon among women in the general population. A study conducted in the United States (N = 3,714 women) found that 18% of women reported overeating, and 10% reported binge eating at least once/week.13 In a large (N = 589), diverse, community-based sample of middle-aged women, 11% reported binge eating at least two to three times per month.14

Studies have found that sexual minority women (SMW; e.g., lesbian, bisexual or other non-heterosexual women) have a higher prevalence of eating disorders than heterosexual adults.15,16 For example, a recent meta-analysis of 21 studies found that lesbian and “mostly heterosexual” women were more likely than heterosexual women to binge eat.17 Similarly, Laska and colleagues found that lesbian and bisexual college students were more likely than their heterosexual counterparts to report past-year binge eating.18 Research shows that binge eating is associated with overweight and obesity among lesbian women in particular.19 However, few studies have examined correlates of overeating and binge eating among SMW.

Minority stress theory is the prevailing explanation for sexual orientation-related health disparities. It is hypothesized that minority stress (i.e., excess stress experienced by individuals from stigmatized social groups) contributes to the higher prevalence of binge eating among SMW.20–23 Sexual minority stressors exist at the individual (e.g., stigma consciousness, internalized homophobia), interpersonal (e.g., discrimination), and structural (e.g., policies that restrict the rights of sexual minorities) levels.24 Researchers have found that stigma consciousness (i.e., the anticipation of being stereotyped and rejected by others)25 is associated with binge eating among SMW.26 Similarly, internalized homophobia24 has been linked to binge eating and risk factors for binge eating, such as body dissatisfaction.21,27,28 At the interpersonal level, exposure to sexual orientation-based discrimination has been positively associated with binge eating among SMW.26 Overeating has been studied much less than binge eating among SMW. However, one study found that sexual orientation concealment (another interpersonal minority stressor) was positively associated with the number of overeating episodes within a 5-day period among SMW.29

Minority stress may also help explain why sexual minority adults are more likely than heterosexual adults to have had a mental health diagnosis prior to the development of an eating disorder.30 A recent systematic review found a statistically significant direct association between depression and binge eating among SMW.27 In a sample of SMW living in New York City (n = 195), investigators found that lifetime diagnosis of depression was associated with lifetime diagnosis of an eating disorder. However, data were not disaggregated by specific eating disorders (e.g., binge eating disorder, anorexia nervosa).30 Similarly, data from a longitudinal study of sexual minority young adults (n = 1,461) found that depressive symptoms were associated with binge eating among young lesbian women.31 Overeating was not assessed.

The affect regulation model can guide examination of associations between overeating and binge eating with mental health. The model posits that individuals engage in these behaviors in response to negative affect (e.g., depressive symptoms).32,33 Research suggests that SMW who engage in binge eating have an urge to eat that is strongly associated with depression, anxiety, and anger.34 Recent findings of the relationship between negative affect and binge eating among lesbian women also support these associations.26,35 However, to our knowledge, no study has examined negative affect and overeating among SMW.

Studies examining depression as a potential mediator of the associations between sexual minority stressors and binge eating in SMW have produced inconsistent findings. Mason and Lewis found that individual-level sexual minority stressors were indirectly associated with binge eating via negative affect (i.e., depression and anxiety) in a sample of 164 SMW.26 In contrast, another study of SMW (n = 138) found that depression did not mediate the relationship between internalized homophobia and binge eating.36

Most research on eating behaviors in SMW has been conducted with small samples of primarily young, White SMW. Few studies have examined overeating (vs. binge eating) in SMW, and even fewer have examined sexual identity (lesbian vs. bisexual) and racial and ethnic differences in the associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating.18,26,27,35–38 Findings related to sexual identity differences are mixed. For instance, Von Schell and colleagues found a higher prevalence of binge eating in bisexual women than their lesbian peers,39 whereas Bayer and colleagues found no difference in the proportions of lesbian and bisexual women who reported binge eating.36 Although researchers have not previously described racial and ethnic differences in overeating and binge eating among SMW, there is evidence that African American40 and Latina women41 in the general population engage in overeating and binge eating at higher rates than their White counterparts.

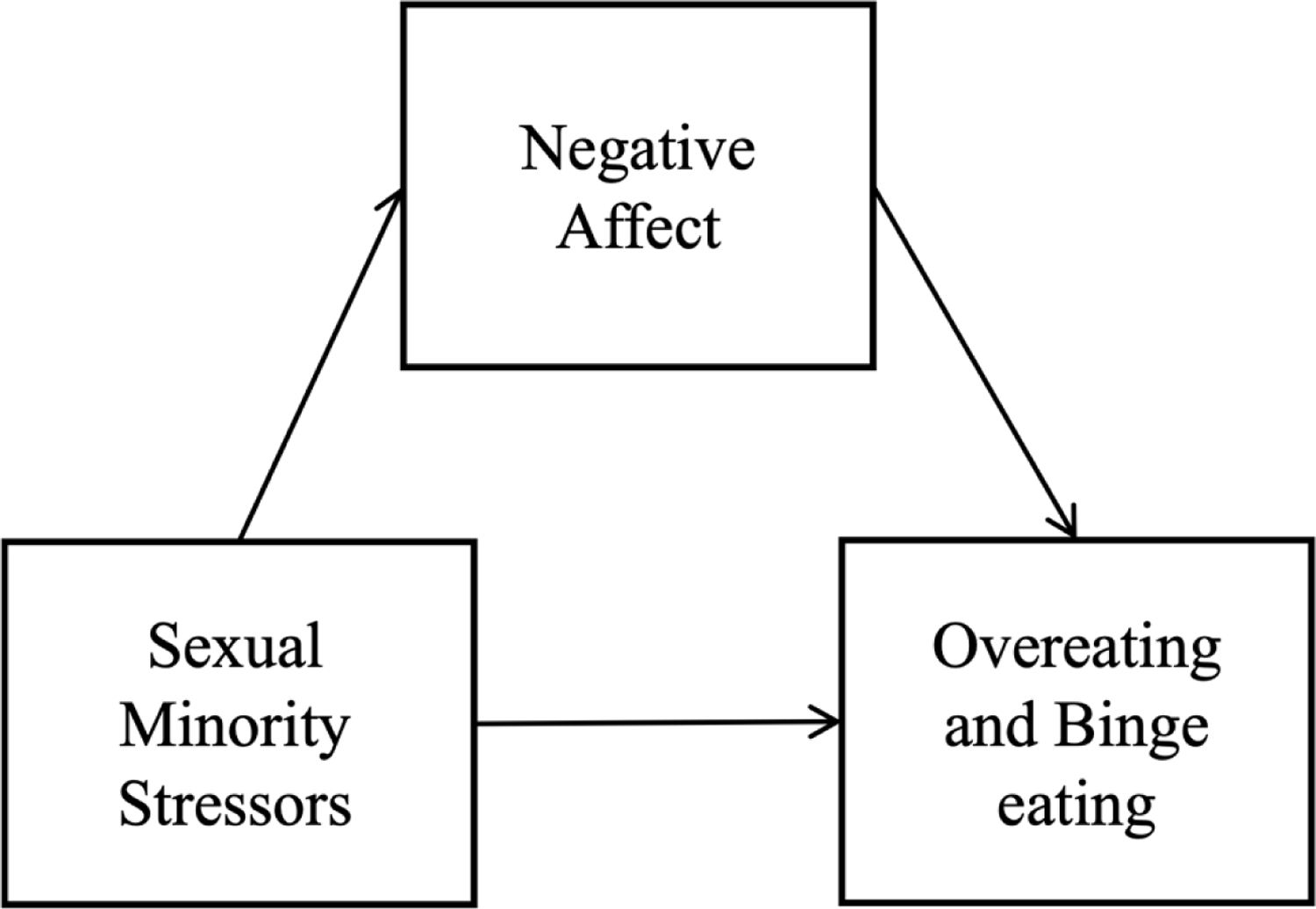

Informed by the minority stress theory and the affect regulation model (Figure 1),22,23,33 we sought to address knowledge gaps by examining the associations of individual-level (i.e., stigma consciousness and internalized homophobia) and interpersonal-level (i.e., experiences of discrimination) sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating among SMW. We also investigated whether these associations were mediated by past-year depression. Although overeating and binge eating behaviors differ in severity,10 given that both are linked to weight-related health outcomes10 and SMW are more likely to have a body mass index (BMI) above 25 kg/m2 (i.e., be overweight) compared to their heterosexual counterparts,42–45 we examined both outcomes. We hypothesized that (1) sexual minority stressors would be positively associated with overeating and binge eating, and (2) past-year depression would partially mediate these associations. To address gaps in the literature, we also conducted exploratory analyses of potential sexual identity and racial and ethnic differences.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the independent (i.e., sexual minority stressors: stigma consciousness, internalized homophobia, sexual orientation-based discrimination), dependent (i.e., overeating and binge eating), and mediator (i.e., depression) variables.

Methods

Sample

The Chicago Health and Life Experiences of Women study (CHLEW; N = 723) is a 20-year longitudinal study of cisgender SMW’s health. Since 2000, four waves of data have been collected from a non-probability, community-based sample. Wave 1 included 447 lesbian women ages 18 or older recruited from the Chicago metropolitan area. In Wave 3 (2010–2012), 353 women (79%) from Wave 1 were retained, and a supplemental sample of 373 women was added to increase the number of bisexual women, African American and Latina SMW, and younger SMW (ages 18–25). In Waves 1–3, structured interviews were conducted in person. Recruitment methods are described elsewhere.46,47 The current study used Wave 3 data because this was the only wave that included measures of overeating and binge eating.

Although only women who identified as lesbian (in Wave 1 and Wave 3) or bisexual (Wave 3) were eligible to participate in the study, over time some participants reported different sexual identities. Given their small sample sizes, we excluded women who (in Wave 3) identified as mostly heterosexual (n = 8), only heterosexual (n = 6), or “other” (n = 14). An additional 67 women were excluded because they responded “don’t know” or “refused” to questions about stigma consciousness (n = 16), internalized homophobia (n = 8), past-year discrimination (n = 15), body dissatisfaction (n = 5), childhood trauma (n = 14), BMI (kg/m2) (n = 7), overeating (n = 1), or binge eating (n = 1). We also excluded 21 women who identified their race and ethnicity as something other than African American, Latina, or White, again due to small sample sizes. The final sample included 607 cisgender SMW who identified as lesbian or bisexual.

Measures

Sexual minority stressors.

Stigma consciousness

Stigma consciousness was assessed using a validated scale that measured participants’ awareness of and sensitivity to stigma.25 This scale has been found to be reliable in prior research with SMW (Cronbach’s ɑ = 0.76).48 Given previous research suggesting that lesbian and bisexual women have different experiences of stigma, separate but parallel measures specific to the participant’s sexual identity were used for lesbian and bisexual participants. Lesbian and bisexual women were asked the same 10 items with the wording of each item corresponding to a participant’s sexual identity. Response options were on a Likert scale of 1 = “strongly agree;” 5 = “strongly disagree.” Example items are “Stereotypes about lesbians/bisexuals have not affected me personally” and “My being lesbian/bisexual does not influence how people act with me.” Bisexual women were also asked an additional 11th item: “I feel others view my bisexual identity as ‘untrue’ or not a real identity.” Several items were reverse coded so that higher scores reflect higher stigma consciousness. To account for the different number of items asked of lesbian and bisexual women, the scale scores were standardized and used in all regression analyses. Cronbach’s alphas for lesbian (ɑ = 0.85) and bisexual women (ɑ = 0.84) in the present sample were good.

Internalized homophobia

Internalized homophobia was assessed using a measure tested in previous work with sexual minority men and women (ɑ = 0.71–0.83).49–51 In the present study, women were asked to indicate on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “strongly disagree;” 5 = “strongly agree”) their level of agreement with 10 statements about their sexual identity (e.g., “I have no regrets about being lesbian/gay/bisexual” and “I tried to stop being attracted to women in general”).52 Positive statements were reverse-coded, and responses were summed so that higher scores indicate greater internalized homophobia (ɑ = 0.80).

Past-year sexual orientation discrimination

Past-year sexual orientation discrimination was assessed by asking participants whether they experienced six types of sexual orientation-based discrimination in the past 12 months (e.g., in public, when accessing healthcare).53 The types reported were summed to create a count measure (0–6). Cronbach’s alpha in the present sample was 0.69, which is consistent with previous work.53

Negative affect.

Past-year depression

Past-year depression was assessed using questions that reflect diagnostic criteria of the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule.54 Depressive episodes were defined as 1) feeling sad, blue, or depressed for greater than two weeks, and 2) co-occurring persistence of three or more symptoms of depression (e.g., feelings of worthlessness, diminished ability to think or concentrate) for at least two weeks. Women who reported at least one depressive episode within one year of their interview date were categorized as having had past-year depression (Yes/No).

Overeating and binge eating

Overeating and binge eating were assessed using items adapted from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)1 that are described in the diagnostic criteria for bulimia nervosa. To assess overeating, participants were asked whether in the past three months they had eaten what other people would consider an unusually large amount of food in a short period of time, such as within two hours (Yes/No; from DSM-IV Criterion 1a). To assess binge eating, women who responded affirmatively to the overeating question were asked a follow-up question: “Did you experience loss of control over your eating at the time? (Yes/No; adapted from DSM-IV Criterion 1b).

Covariates.

Studies have shown than SMW who report childhood trauma (e.g., sexual and physical abuse) are more likely to report higher odds of overeating 55 There is also a large body of evidence that body dissatisfaction is positively associated with binge eating in SMW.20,21,27,28,56,57 We selected these and other covariates based on prior findings of significant relationships with overeating or binge eating in women.18,20,21,27,28,40,41,55–58

Sexual identity

Sexual identity was assessed with a single item: “How do you define your sexual identity? Would you say that you are…” only lesbian, mostly lesbian, bisexual, mostly heterosexual, or only heterosexual. As mentioned above, women who identified as only lesbian, mostly lesbian, or bisexual were included in the present study. We also assessed age (in years), race and ethnicity (African American; Latina; White), education (less than high school; high school or GED; some college; Bachelor’s degree; graduate degree), and self-reported height and weight (to calculate BMI).

Body dissatisfaction

Body dissatisfaction was assessed using the 9-item version of the body dissatisfaction sub-scale of the Eating Disorders Inventory-3. This scale has been shown to be reliable in women with and without eating disorders, both in the general population and among SMW (Cronbach’s ɑ > 0.90).59,60 Women were asked to respond to 9 statements using a 6-point Likert scale (1 = “never” to 6 = “always”). Sample items included “I think that my stomach is too big” and “I feel satisfied with the shape of my body.” Positive statements were reverse scored so that higher scores reflect greater body dissatisfaction (ɑ = 0.87). Childhood trauma asked about experiences before the participant was age 18. Childhood sexual abuse was measured using established criteria61 and coded dichotomously (Yes/No). Childhood physical abuse was assessed by asking “Do you feel that you were physically abused by your parents or other family members when you were growing up?” (Yes/No), and parental neglect was assessed by asking participants if they felt their parents neglected their basic needs when they were growing up (Yes/No). We summed responses to these three items (range 0–3)—a method that has been used in previous CHLEW research.55,62

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were conducted using MPlus Version 7.4. Because we identified no differences in key variables between lesbian and mostly lesbian women in preliminary analyses, these groups were combined in comparisons with bisexual women. We examined sexual identity and racial and ethnic differences using Chi-square for categorical variables and independent sample t-test for continuous variables. For bivariate analyses, we used a Bonferroni correction to select an a priori p-value of < 0.001 to account for multiple comparisons.

To test our two main hypotheses that: (1) sexual minority stressors (i.e., stigma consciousness, internalized homophobia, and sexual orientation-based discrimination) would be positively associated with overeating and binge eating; and (2) past-year depression would partially mediate these associations, we used path analyses to obtain the direct, indirect (mediated), and total associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating. Analyses were adjusted for age, sexual identity, race and ethnicity, education, body dissatisfaction, childhood trauma, and BMI. Bootstrapping was used to obtain robust standard errors and confidence intervals for indirect paths, which permitted significance testing of the indirect paths of sexual minority stressors on overeating and binge eating.63,64 Using bias-corrected bootstrapping, 1,000 bootstraps were used to generate confidence intervals for these indirect paths.64,65

We also conducted exploratory analyses to determine whether associations between sexual minority stressors and overeating and binge eating differed by sexual identity or by race and ethnicity. These models were adjusted for age, education, body dissatisfaction, childhood trauma, and BMI. We first added interaction terms to the previously described models to test for interactions between each sexual minority stressor and sexual identity (lesbian [referent] vs. bisexual). In separate models, we added interaction terms to test for interactions between each sexual minority stressor and race and ethnicity to compare White women [referent] to African American and Latina women, separately. We also compared African American [referent] to Latina women.

Results

The final sample included 607 SMW (mean age 39.7 years; SD = 14.2); 74.6% identified as lesbian and 25.4% as bisexual. Table 1 presents racial and ethnic and sexual identity differences across study variables. The sample was racially and ethnically diverse (38.2% White, 37.1% African American; 24.7% Latina). Approximately 48% of the sample reported having a college education or higher. Nearly a third (30.8%) of SMW met criteria for past-year depression, and 79% reported at least one type of childhood trauma (i.e., sexual or physical abuse or neglect). Lesbian women had lower internalized homophobia scores than bisexual women (p < 0.001). More than one-third of the sample reported at least one type of sexual orientation-based discrimination in the past year. Overeating in the previous 3 months was reported by 17.5% of SMW, whereas only 9.2% endorsed an episode of binge eating within that timeframe.

Table 1.

Racial and ethnic and sexual identity differences across study variables (N = 607).

| Race and ethnicity | Sexual identity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| Total Sample (N = 607) | White (n = 232) | African American (n = 225) | White vs. African American | Latina (n = 150) | White vs. Latina | Lesbian (n = 453) | Bisexual (n = 154) | Lesbian vs. Bisexual | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| Mean (SD)/N (%) | p-value | Mean (SD)/N (%) | p-value | Mean (SD)/N (%) | p-value | ||||

| Demographic/clinical characteristics | |||||||||

| Age (range 18–82) | 39.7 (14.2) | 42.9 (16.0) | 39.4 (13.1) | 0.01 | 35.3 (11.2) | <0.001* | 41.6 (14.2) | 34.1 (12.4) | <0.001* |

| Sexual identity | 0.53 | 0.30 | – | – | – | ||||

| Lesbian | 453 (74.6) | 178 (76.7) | 167 (74.2) | 108 (72.0) | |||||

| Bisexual | 154 (25.4) | 54 (23.3) | 59 (25.8) | 42 (28.0) | |||||

| Race and ethnicity | 0.58 | ||||||||

| White | 232 (38.2) | – | – | – | – | – | 178 (39.3) | 54 (35.0) | |

| African American | 225 (37.1) | 167 (36.9) | 58 (37.7) | ||||||

| Latina | 150 (24.7) | 108 (23.8) | 42 (27.3) | ||||||

| Education | <0.001* | <0.001* | <0.01 | ||||||

| High school or less | 122 (20.1) | 9 (3.9) | 77 (34.2) | 36 (24.0) | 76 (16.7) | 46 (29.9) | |||

| Some college | 196 (32.3) | 55 (23.7) | 87 (38.7) | 54 (36.0) | 148 (32.7) | 48 (31.2) | |||

| Bachelor’s degree | 128 (21.1) | 66 (28.5) | 34 (15.1) | 28 (18.7) | 101 (22.3) | 27 (17.5) | |||

| Graduate degree | 161 (26.5) | 102 (43.9) | 27 (12.0) | 32 (21.3) | 128 (28.3) | 33 (21.4) | |||

| Body mass index (range 16.3–58.2 kg/m2) | 29.1 (7.6) | 27.1 (7.4) | 31.8 (7.9) | <0.001* | 28.1 (6.3) | 0.19 | 29.3 (7.9) | 28.3 (6.8) | 0.18 |

| Psychosocial factors | |||||||||

| Past-year depression | 187 (30.8) | 72 (31.0) | 67 (29.8) | 0.77 | 48 (32.0) | 0.84 | 140 (30.9) | 47 (30.5) | 0.93 |

| Body dissatisfaction (range 0–36) | 13.3 (8.9) | 13.4 (9.7) | 13.5 (8.3) | 0.88 | 12.6 (8.2) | 0.37 | 13.3 (8.9) | 13.1 (8.8) | 0.74 |

| Count of types of childhood trauma | <0.001* | 0.02 | 0.24 | ||||||

| 0 | 129 (21.3) | 74 (31.9) | 24 (10.7) | 31 (20.7) | 91 (20.1) | 38 (24.7) | |||

| 1 | 231 (38.0) | 88 (37.9) | 85 (37.8) | 58 (38.7) | 169 (37.3) | 62 (40.3) | |||

| 2 | 207 (34.1) | 51 (22.0) | 105 (46.7) | 51 (34.0) | 159 (35.1) | 48 (31.1) | |||

| 3 | 40 (6.6) | 19 (8.2) | 11 (4.8) | 10 (6.6) | 34 (7.5) | 6 (3.9) | |||

| Sexual minority stressors | |||||||||

| Stigma consciousness in lesbian women (range 12–48) | 28.1 (5.9) | 28.6 (5.4) | 28.5 (6.0) | 0.93 | 26.9 (6.6) | 0.02 | – | – | – |

| Stigma consciousness in bisexual women (range 11–51) | 27.7 (8.6) | 29.1 (8.7) | 27.7 (7.8) | 0.42 | 26.1 (9.5) | 0.11 | – | – | – |

| Internalized homophobia (range 10–38) | 14.7 (5.4) | 13.9 (4.6) | 15.1 (5.6) | 0.02 | 15.2 (6.0) | 0.02 | 13.7 (4.7) | 17.3 (6.1) | <0.001* |

| Sexual orientation-based discrimination | 0.80 | 0.20 | 0.42 | ||||||

| 0 | 392 (64.6) | 145 (62.5) | 147 (65.3) | 100 (66.7) | 285 (62.9) | 107 (69.5) | |||

| 1–2 | 169 (27.7) | 65 (28.0) | 60 (26.7) | 44 (29.3) | 130 (28.7) | 39 (25.3) | |||

| 3–4 | 39 (6.4) | 19 (8.2) | 14 (6.2) | 6 (4.0) | 32 (7.1) | 7 (4.6) | |||

| 5–6 | 7 (1.1) | 3 (1.3) | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.3) | 1 (0.6) | |||

| Eating behaviors | |||||||||

| Overeating | 106 (17.5) | 39 (16.8) | 38 (16.9) | 0.98 | 29 (19.3) | 0.53 | 77 (17.0) | 29 (18.8) | 0.61 |

| Binge eating | 56 (9.2) | 27 (11.6) | 16 (7.1) | 0.10 | 13 (8.7) | 0.35 | 42 (9.3) | 14 (9.1) | 0.95 |

Note. Stigma consciousness for lesbian and bisexual women were measured with separate scales with a different number of items. Unstandardized stigma consciousness scores are presented for lesbian and bisexual women.

p < 0.001.

Table 2 presents results of the path analysis examining the direct, indirect, and total associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating. Regarding covariates, SMW who reported higher body dissatisfaction (AOR 1.04, 95% CI = 1.01–1.07) and a higher count of types of childhood trauma (AOR 1.55, 95% CI = 1.17–2.05) had higher odds of overeating. The direct, indirect, and total associations of internalized homophobia and sexual orientation-based discrimination with overeating were not significant. However, the direct (AOR 1.31, 95% CI = 1.03–1.66) and total (AOR 1.32, 95% CI = 1.04–1.67) associations of stigma consciousness were associated with higher odds of overeating.

Table 2.

Direct, indirect, and total associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating in SMW (N = 607).

| Paths | Overeating |

Binge eating |

|---|---|---|

| AOR (99% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Direct associations | ||

| Stigma consciousness | 1.31 (1.03‒1.66)* | 1.22 (0.87‒1.70) |

| Internalized homophobia | 1.02 (0.97‒1.06) | 1.01 (0.96‒1.08) |

| Sexual orientation-based discrimination | 1.05 (0.85‒1.30) | 0.86 (0.60‒1.24) |

| Sexual identity | ||

| Lesbian | Ref | Ref |

| Bisexual | 0.91 (051‒1.63) | 0.96 (0.14‒2.09) |

| Age | 0.96 (0.94–098)** | 0.98 (0.96‒1.01) |

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| White | Ref | Ref |

| African American | 0.58 (0.30‒1.10) | 0.33 (0.14‒0.78)* |

| Latina | 0.83 (0.45‒1.55) | 0.52 (0.17‒1.25) |

| Education | 0.84 (0.68‒1.04) | 0.87 (0.64‒1.19) |

| Body mass index | 1.02 (0.98‒1.06) | 1.03 (0.99‒1.07) |

| Body dissatisfaction | 1.04 (1.01‒1.07)** | 1.06 (1.03‒1.10)*** |

| Childhood trauma | 1.55 (1.17‒2.05)** | 1.58 (1.10‒2.28)* |

| Past-year depression | 1.57 (0.96‒2.56) | 3.04 (1.61‒5.74)** |

| Indirect associations | ||

| Past-year depression | ||

| Stigma consciousness → depression | 1.01 (0.98‒1.03) | 1.02 (0.97‒1.07) |

| Internalized homophobia → depression | 1.00 (0.99‒1.01) | 1.00 (0.99‒1.02) |

| Past-year discrimination → depression | 1.02 (0.99‒1.05) | 1.04 (0.99‒1.10) |

| Total associations | ||

| Stigma consciousness | 1.32 (1.04‒1.67)* | 1.24 (0.89‒1.73) |

| Internalized homophobia | 1.02 (0.98‒1.06) | 1.02 (0.96‒1.09) |

| Count of past-year discrimination type | 1.07 (0.87–1.32) | 0.90 (0.62‒1.32) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratios. All models adjusted for age, sexual identity, race and ethnicity, education, body dissatisfaction, childhood trauma, and BMI. Stigma consciousness scores were standardized to account for the different number of items asked to lesbian- and bisexual-Identified women.

p < 0.05.

p < 0.01.

p < 0.001.

Regarding covariates, SMW who reported higher body dissatisfaction (AOR 1.06, 95% CI = 1.03–1.10), a higher count of types of childhood trauma (AOR 1.58, 95% CI = 1.10–2.28), and past-year depression (AOR 3.04, 95% CI = 1.61–5.74) had higher odds of binge eating. We found no direct associations between sexual minority stressors and binge eating. Also, past-year depression did not mediate the association of any of the sexual minority stressors with overeating or binge eating.

Results of exploratory analyses indicated there were no significant sexual identity differences in the direct or indirect associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating or binge eating (data not shown). Similarly, there were no significant differences in the associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating between African American and White SMW. However, the association of stigma consciousness with overeating was stronger among Latina than White SMW (AOR 1.95, 95% CI = 1.21–3.12, p = 0.01) and African American SMW (AOR 1.99, 95% CI = 1.19–3.31, p = 0.01).

Discussion

In this diverse sample of SMW, we found that higher levels of stigma consciousness were associated with higher odds of overeating. Internalized homophobia and sexual orientation-based discrimination were not associated with overeating, and no sexual minority stressor was significantly associated with binge eating. Past-year depression did not mediate associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating or binge eating. We found no sexual identity differences in associations between minority stressors and overeating or binge eating. We did, however, find that greater stigma consciousness was associated with higher odds of overeating in Latina SMW relative to both White and African American SMW.

This is one of few studies to document stigma consciousness, or one’s awareness of and sensitivity to stigma, as a minority stressor associated with overeating in SMW. Our findings of a significant relationship between overeating and stigma consciousness, but not internalized homophobia, may be explained in part by nature of the sample. Women who volunteered to participate in the CHLEW study were likely more comfortable with their sexual identity than those who did not. Indeed, levels of internalized homophobia were quite low in our sample. In addition, although a good deal of research with sexual minority people has included measurement of internalized homophobia, most of this research has focused on sexual minority men, and findings have been mixed.66,67 Our internalized homophobia measure was adapted from a version most commonly used with men. On the other hand, stigma consciousness has been investigated in a broad range of samples, including many studies of women (see e.g., Pinel, 1999). Stigma consciousness can be thought of as sensitivity to social rejection, or the expectation of being stereotyped or stigmatized. It is a form of anticipatory anxiety (or dread) about an event that will or may happen in the future. Story and colleagues (2014) illustrated how the anticipation or dread of pain can be as uncomfortable as the experience of pain itself.68 The anticipation of being stereotyped or stigmatized may be a more potent stressor than internalized homophobia—and may result in overeating as a means of coping.

Further, prior research has linked anticipated weight stigma (i.e., heightened awareness of the threat of mistreatment due to weight)69 with overeating and binge eating.70,71 This anticipation of stigma (in relation to both sexual minority status and weight) may be a driver of the significant associations between stigma consciousness and overeating in our study.72,73. Lastly, it is possible that past-year sexual orientation-based discrimination may be too distal to affect day-to-day eating behaviors among SMW, as this minority stressor was not associated with either outcome in this study.

Previous studies have focused on the link between stigma consciousness (among other sexual minority stressors) and binge eating,26,27 but not overeating. Given that overeating is a component of binge eating and a significant health concern as it contributes to overweight and obesity, considering how aspects of minority stress may be associated with overeating in SMW is warranted. Contrary to our hypotheses, we did not find any associations between stigma consciousness, internalized homophobia, and past-year discrimination and binge eating, which was operationalized as at least one episode of overeating with LOC of eating during the last three months. One potential explanation for these unexpected null findings is that binge eating in this sample was low, with only 9.2% of the sample (or 56 women) reporting a binge episode in the last three months, relative to the rate of overeating, which was higher at 17.5% of the sample (106 women). Therefore, it is possible that we were underpowered to detect binge eating effects. Other studies among younger SMW have reporting binge eating rates of 15.0–21.2%,26,36,39 and in one study, the rate of past-month overeating was 25.0% for lesbian women and 38.1% for bisexual women.39 In a recent literature review, authors found that the prevalence of eating disorders was lower in middle and older age women than in younger women.74 Further, SMW in our study were older (mean age = 39.7 years) compared to most studies that focus on binge eating in young SMW.26,36,39 This could account for the discrepancy in the rates of overeating and binge eating and help explain our null findings related to associations between minority stressors and binge eating. Lastly, because White women are more likely to engage in binge eating than Latina and African American women,75 the fact that only 38% of our sample is White may have also contributed to null findings.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to document higher odds of overeating associated with stigma consciousness in Latina SMW. However, previous studies have identified psychosocial factors associated with overeating and binge eating in Latino/a adults in the general population. Acculturative stress (i.e., stress related to differences between one’s culture of origin and host culture) has been associated with eating disorder symptoms among Latina female undergraduates76 and emotional eating among Latino adolescents.77 This is of note because analyses of representative data from the Latino Health and Wellbeing Study found that among Latino/a adults, emotional eating was associated with higher odds of overeating, operationalized as eating 500 calories over one’s daily caloric needs.78 Further, in another study, Alegria and colleagues found that Latino adults with higher acculturation and those with lower educational attainment were more likely to report binge eating at least twice a week for at least several months.79 Acculturative stress, through its relation to emotional eating, may help explain why the association between stigma consciousness and overeating was stronger among Latina SMW compared to White and African American SMW in our study. It is also important to note that neither the Latino Health and Wellbeing Study nor Alegria and colleagues’ study disaggregated data for Latino adults by sex or sexual identity, and hence minority stressors like stigma consciousness were not measured.78,79 Future studies should examine the differential impacts of multiple psychosocial factors (e.g., acculturative stress) on overeating and binge eating by sex and sexual identity.

Our finding that negative affect, in the form of past-year depression, did not mediate the relationships between sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating in SMW is consistent with the work of Bayer and colleagues.36 In contrast, Mason and Lewis found that individual-level sexual minority stressors were indirectly associated with binge eating via negative affect among SMW.26 There are several potential explanations for these inconsistencies. First, Mason and Lewis used a composite measure that captured multiple dimensions of negative affect as their mediator.26 This could account for greater variance than depression alone, thereby potentially contributing to their statistically significant finding.26 In addition, Mason and Lewis used a more recent (past 4 weeks) timeframe for negative affect than the past-year timeframe that we and Bayer and colleagues36 used. Mason and Lewis’ sample was also predominately White and included SMW between the ages of 18–40;26 our sample was more diverse in race and ethnicity and age. Future work should examine whether theoretical models tested among predominately young, White samples of SMW are appropriate for older and racial and ethnic minority samples. An intersectionality lens, taking into account stressors related to multiple marginalized identities, would improve future research on racial and ethnic differences in overeating and binge eating among SMW.80,81

Our findings have important implications for clinical practice. Greater body dissatisfaction and childhood trauma histories were associated with higher odds of overeating and binge eating in SMW. In addition, we found that approximately 79% of SMW reported at least one type of childhood trauma, a finding that is consistent with previous work.82–84 Primary care and mental health clinicians should regularly screen for childhood trauma, depression, and body dissatisfaction, as well as sexual minority stressors (particularly stigma consciousness), to help identify SMW who are at risk for overeating and binge eating. Educating SMW about healthy coping strategies to deal with stigma consciousness may help reduce their risk of engagement in overeating in particular.

Limitations

Despite its strengths, this study has several limitations. Although the CHLEW is a longitudinal study, we used cross-sectional data from the only study wave (Wave 3) in which overeating and binge eating were assessed. Prospective studies are needed to better understand predictors and consequences of overeating and binge eating in SMW. In contrast to the discrimination measure that assessed past-year exposure, measures of stigma consciousness and internalized homophobia were not anchored to a specific timeframe. Our analyses did not include a measure of sexual identity disclosure, which may have affected the minority stress experiences of women in the study.85,86 Moreover, our measure of BMI was self-reported, which is common,87 but may have introduced measurement error. Future studies should investigate these associations using objectively-measured BMI. Our use of single-item measures to assess overeating and binge eating is also a limitation. Multi-item scales to assess overeating and binge eating may more adequately capture nuances between overeating, LOC, and binge eating.26,35,88 Future research using validated scales to assess overeating and binge eating specifically among SMW is needed. Lastly, our study did not include sufficient numbers of women who identify as something other than lesbian or bisexual to include them in analyses. The CHLEW also included too few SMW from racial and ethnic groups other than African American, Latina, or White to permit even exploratory analyses. Given the limited research on binge eating in SMW of color, future studies should include larger numbers of Asian and other SMW of color.

Conclusions

In a diverse sample of SMW, we found that stigma consciousness was positively associated with overeating. Past-year depression did not mediate the associations of sexual minority stressors with overeating and binge eating. Exploratory analyses revealed the association of stigma consciousness with overeating was stronger among Latina SMW compared to White and African American SMW. These findings emphasize the need to further examine psychosocial correlates of overeating and binge eating among SMW. Future research should use an intersectionality lens to focus on minority stressors that may be specific to multiple marginalized identities, as well as other psychosocial factors that may contribute to overeating and binge eating.

Highlights.

Our study included a diverse, community-based sample of sexual minority women (SMW)

Stigma consciousness in Latina SMW was associated with higher odds of overeating

Links between stigma consciousness with overeating were not explained by depression

Discrimination was not linked with overeating or binge eating

Internalized homophobia was not linked with overeating or binge eating

Acknowledgments

Funding

Ms. Ancheta’s work was supported by an Individual Predoctoral Fellowship funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research (F31NR019432) and the Jonas Scholars Program of Jonas Philanthropies (Jonas Scholar 2018-2020). Dr. Caceres’ work was supported by a Mentored Research Scientist Career Development Award by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (K01HL146965). Dr. Veldhuis’ work was supported by a National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA)/National Institutes of Health (NIH) Ruth Kirschstein Postdoctoral Individual National Research Service Award (F32AA025816) and an NIH/NIAAA Pathway to Independence Award (K99AA028049). The CHLEW study (Dr. Hughes’ work) was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01AA0013328-14).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

April J. Ancheta, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 W 168th St, New York, NY 10032.

Billy A. Caceres, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 W 168th St, New York, NY 10032.

Sarah S. Zollweg, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 W 168th St, New York, NY 10032.

Kristin E. Heron, Department of Psychology, Old Dominion University, Virginia Consortium Program in Clinical Psychology, 250 Mills Godwin Building, Norfolk, VA 23529.

Cindy B. Veldhuis, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 W 168th St, New York, NY 10032.

Nicole VanKim, Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Public Health and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts Amherst, 406 Arnold House, Amherst, MA 01003.

Tonda L. Hughes, Columbia University School of Nursing, 560 W 168th St, New York, NY 10032.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-IV) 4th ed. Washington, D.C. 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, et al. Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Mental Health. Eating disorders: About more than food National Institutes of Health; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, Kessler RC. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication. Biol Psychiatry 2007;61(3):348–358. 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Coit CE, et al. Longitudinal study of the diagnosis of components of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with binge-eating disorder. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2010;91(6):1568–1573. 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Telch CF, Pratt EM, Niego SH. Obese women with binge eating disorder define the term binge. Int J Eat Disord 1998;24(3):313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldschmidt AB, Engel SG, Wonderlich SA, et al. Momentary affect surrounding loss of control and overeating in obese adults with and without binge eating disorder. Obesity 2012;20(6):1206–1211. 10.1038/oby.2011.286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins PE, Conley CS, Rienecke Hoste R, Meyer C, Blissett JM. Perception of control during episodes of eating: Relationships with quality of life and eating psychopathology. Int J Eat Disord 2012;45(1):115–119. 10.1002/eat.20913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tanofsky-Kraff M, Shomaker LB, Olsen C, et al. A prospective study of pediatric loss of control eating and psychological outcomes. J Abnorm Psychol 2011;120(1):108. 10.1037/a0021406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldschmidt AB, Loth KA, MacLehose RF, Pisetsky EM, Berge JM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Overeating with and without loss of control: Associations with weight status, weight-related characteristics, and psychosocial health. Int J Eat Disord 2015;48(8):1150–1157. 10.1002/eat.22465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sonneville KR, Horton NJ, Micali N, et al. Longitudinal associations between binge eating and overeating and adverse outcomes among adolescents and young adults: Does loss of control matter? JAMA pediatrics 2013;167(2):149–155. 10.1001/2013.jamapediatrics.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lydecker JA, Grilo CM. Comparing men and women with binge-eating disorder and comorbid obesity. Int J Eat Disord 2018;51(5):411–417. 10.1002/eat.22847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Striegel-Moore RH, Rosselli F, Perrin N, et al. Gender difference in the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms. Int J Eat Disord 2009;42(5):471–474. 10.1002/eat.20625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcus MD, Bromberger JT, Wei HL, Brown C, Kravitz HM. Prevalence and selected correlates of eating disorder symptoms among a multiethnic community sample of midlife women. Ann Behav Med 2007;33(3):269–277. 10.1007/bf02879909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Calzo JP, Blashill AJ, Brown TA, Argenal RL. Eating disorders and disordered weight and shape control behaviors in sexual minority populations. Current psychiatry reports 2017;19(8):49. 10.1007/s11920-017-0801-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bankoff SM, Pantalone DW. Patterns of disordered eating behavior in women by sexual orientation: A review of the literature. Eating disorders 2014;22(3):261–274. 10.1080/10640266.2014.890458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dotan A, Bachner-Melman R, Dahlenburg SC. Sexual orientation and disordered eating in women: A meta-analysis. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 2019:1–13. 10.1007/s40519-019-00824-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laska MN, VanKim NA, Erickson DJ, Lust K, Eisenberg ME, Rosser BS. Disparities in weight and weight behaviors by sexual orientation in college students. Am J Public Health 2015;105(1):111–121. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mason TB. Binge eating and overweight and obesity among young adult lesbians. LGBT health 2016;3(6):472–476. 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beren SE, Hayden HA, Wilfley DE, Grilo CM. The influence of sexual orientation on body dissatisfaction in adult men and women. Int J Eat Disord 1996;20(2):135–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pitman GE. Body image, compulsory heterosexuality, and internalized homophobia. Journal of Lesbian Studies 1999;3(4):129–139. 10.1300/J155v03n04_17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meyer. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull 2003;129(5):674–697. 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks VR. Minority stress and lesbian women Lexington, Massachusetts: Lexington Books; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hatzenbuehler ML, Pachankis JE. Stigma and minority stress as social determinants of health among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: Research evidence and clinical implications. Pediatr Clin North Am 2016;63(6):985–997. 10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pinel EC. Stigma consciousness: The psychological legacy of social stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol 1999;76(1):114. 10.1037/0022-3514.76.1.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mason TB, Lewis RJ. Minority stress and binge eating among lesbian and bisexual women. J Homosex 2015;62(7):971–992. 10.1080/00918369.2015.1008285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mason TB, Lewis RJ, Heron KE. Disordered eating and body image concerns among sexual minority women: A systematic review and testable model. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2018;5(4):397. 10.1037/sgd0000293 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meneguzzo P, Collantoni E, Gallicchio D, et al. Eating disorders symptoms in sexual minority women: A systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review 2018;26(4):275–292. 10.1002/erv.2601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Panza E, Fehling KB, Pantalone DW, Dodson S, Selby EA. Multiply marginalized: Linking minority stress due to sexual orientation, gender, and weight to dysregulated eating among sexual minority women of higher body weight. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2020;Advance online publication. 10.1037/sgd0000431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Feldman MB, Meyer IH. Comorbidity and age of onset of eating disorders in gay men, lesbians, and bisexuals. Psychiatry Res 2010;180(2–3):126–131. 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katz-Wise SL, Scherer EA, Calzo JP, et al. Sexual minority stressors, internalizing symptoms, and unhealthy eating behaviors in sexual minority youth. Ann Behav Med 2015;49(6):839–852. 10.1007/s12160-015-9718-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polivy J, Herman CP. Etiology of binge eating: Psychological mechanisms. In: Fairburn CG & Wilson GT, ed. Binge eating: Nature, assessment, and treatment New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993:pp. 173–205. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haedt-Matt AA, Keel PK. Revisiting the affect regulation model of binge eating: A meta-analysis of studies using ecological momentary assessment. Psychol Bull 2011;137(4):660. 10.1037/a0023660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heffernan K Binge eating, substance use, and coping styles in a lesbian sample [Doctoral dissertation], Rutgers University; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mason TB, Lewis RJ. Minority stress, body shame, and binge eating among lesbian women: Social anxiety as a linking mechanism. Psychol Women Q 2016;40(3):428–440. 10.1177/0361684316635529 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bayer V, Robert-McComb JJ, Clopton JR, Reich DA. Investigating the influence of shame, depression, and distress tolerance on the relationship between internalized homophobia and binge eating in lesbian and bisexual women. Eating behaviors 2017;24:39–44. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bell K, Rieger E, Hirsch JK. Eating disorder symptoms and proneness in gay men, lesbian women, and transgender and gender non-conforming adults: Comparative levels and a proposed mediational model. Front Psychol 2019;9:2692. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mason TB, Lewis RJ. Clustered patterns of behavioral and health-related variables among young lesbian women. Behav Ther 2019;50(4):683–695. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Von Schell A, Ohrt TK, Bruening AB, Perez M. Rates of disordered eating behaviors across sexual minority undergraduate men and women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2018;5(3):352. 10.1037/sgd0000278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Connolly MK. Overeating among black american women: The role of racism, racial socialization, and stress [Doctoral dissertation], Boston College; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borghese AE. Acculturative stress, discrimination, ethnic identity, and binge eating among latina college students [Doctoral dissertation], Fordham University; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azagba S, Shan L, Latham K. Overweight and obesity among sexual minority adults in the United States. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16(10). 10.3390/ijerph16101828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eliason MJ, Ingraham N, Fogel SC, et al. A systematic review of the literature on weight in sexual minority women. Womens Health Issues 2015;25(2):162–175. 10.1016/j.whi.2014.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caceres BA, Brody A, Luscombe RE, et al. A systematic review of cardiovascular disease in sexual minorities. Am J Public Health 2017;107(4):e13–e21. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Caceres BA, Streed CG Jr, Corliss HL, et al. Assessing and addressing cardiovascular health in LGBTQ adults: A scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Martin K, Johnson TP, Hughes TL. Using respondent driven sampling to recruit sexual minority women. Survey practice 2015;8(2). 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181b0f311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hughes T, Wilsnack S, Martin K, Matthews A, Johnson T. Alcohol use among sexual minority women: Methods used and lessons learned in the 20-year chicago health and life experiences of women study. The International Journal of Alcohol and Drug Research 2021;9(1):30–42. 10.7895/ijadr.289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lewis RJ, Winstead BA, Mason TB, Lau-Barraco C. Social factors linking stigma-related stress with alcohol use among lesbians. J Soc Issues 2017;73(3):545–562. 10.1111/josi.12231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Martin JL, Dean L. Summary of measures: Mental health effects of aids on at-risk homosexual men Unpublished manuscript. 1987.

- 50.Herek GM, Cogan JC, Gillis JR, Glunt EK. Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. J Gay Lesbian Med Assoc 1998;2:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyer IH. Minority stress and mental health in gay men. J Health Soc Behav 1995:38–56. https://doi.org/https://www.jstor.org/stable/2137286 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC, Glunt EK. Hate crime victimization among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults: Prevalence, psychological correlates, and methodological issues. Journal of interpersonal violence 1997;12(2):195–215. 10.1177/088626097012002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krieger N, Smith K, Naishadham D, Hartman C, Barbeau EM. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Soc Sci Med 2005;61(7):1576–1596. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robins LN, Helzer JE, Croughan J, Ratcliff KS. National institute of mental health diagnostic interview schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38(4):381–389. 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caceres BA, Veldhuis CB, Hickey KT, Hughes TL. Lifetime trauma and cardiometabolic risk in sexual minority women. J Womens Health 2019;28(9):1200–1217. 10.1089/jwh.2018.7381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pennesi J-L, Wade TD. A systematic review of the existing models of disordered eating: Do they inform the development of effective interventions? Clin Psychol Rev 2016;43:175–192. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stice E, Shaw HE. Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings. J Psychosom Res 2002;53(5):985–993. 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Feldman MB, Meyer IH. Childhood abuse and eating disorders in gay and bisexual men. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40(5):418–423. 10.1002/eat.20378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Garner DM, Olmstead MP, Polivy J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 1983;2(2):15–34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alvy LM. Do lesbian women have a better body image? Comparisons with heterosexual women and model of lesbian-specific factors. Body Image 2013;10(4):524–534. 10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wyatt GE. The sexual abuse of afro-american and white-american women in childhood. Child Abuse Negl 1985;9(4):507–519. 10.1016/0145-2134(85)90060-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Andersen JP, Hughes TL, Zou C, Wilsnack SC. Lifetime victimization and physical health outcomes among lesbian and heterosexual women. PLoS One 2014;9(7). 10.1371/journal.pone.0101939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hayes AF. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach Guilford publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008;40(3):879–891. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shrout PE, Bolger N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods 2002;7(4):422. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berg RC, Munthe-Kaas HM, Ross MW. Internalized homonegativity: A systematic mapping review of empirical research. J Homosex 2016;63(4):541–558. 10.1080/00918369.2015.1083788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Puckett JA, Newcomb ME, Ryan DT, Swann G, Garofalo R, Mustanski B. Internalized homophobia and perceived stigma: A validation study of stigma measures in a sample of young men who have sex with men. Sexuality Research and Social Policy 2017;14(1):1–16. 10.1007/s13178-016-0258-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Story GW, Vlaev I, Seymour B, Winston JS, Darzi A, Dolan RJ. Dread and the disvalue of future pain. PLoS Comput Biol 2013;9(11):e1003335. 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1003335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Major B, Eliezer D, Rieck H. The psychological weight of weight stigma. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2012;3(6):651–658. 10.1177/1948550611434400 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wu YK, Berry DC. Impact of weight stigma on physiological and psychological health outcomes for overweight and obese adults: A systematic review. J Adv Nurs 2018;74(5):1030–1042. 10.1111/jan.13511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Carels R, Wott C, Young K, Gumble A, Koball A, Oehlhof M. Implicit, explicit, and internalized weight bias and psychosocial maladjustment among treatment-seeking adults. Eating behaviors 2010;11(3):180–185. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Romano E, Haynes A, Robinson E. Weight perception, weight stigma concerns, and overeating. Obesity 2018;26(8):1365–1371. 10.1002/oby.22224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Schvey NA, Puhl RM, Brownell KD. The impact of weight stigma on caloric consumption. Obesity 2011;19(10):1957–1962. 10.1038/oby.2011.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mangweth-Matzek B, Hoek HW. Epidemiology and treatment of eating disorders in men and women of middle and older age. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2017;30(6):446–451. 10.1097/yco.0000000000000356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Downes B, Resnick M, Blum R. Ethnic differences in psychosocial and health behavior correlates of dieting, purging, and binge eating in a population-based sample of adolescent females. Int J Eat Disord 1997;22(3):315–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Claudat K, White EK, Warren CS. Acculturative stress, self-esteem, and eating pathology in latina and asian american female college students. J Clin Psychol 2016;72(1):88–100. 10.1002/jclp.22234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simmons S, Limbers CA. Acculturative stress and emotional eating in latino adolescents. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 2019;24(5):905–914. 10.1007/s40519-018-0602-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lopez-Cepero A, Frisard CF, Lemon SC, Rosal MC. Association between emotional eating, energy-dense foods and overeating in latinos. Eating behaviors 2019;33:40–43. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Alegria M, Woo M, Cao Z, Torres M, Meng Xl, Striegel-Moore R. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in latinos in the United States. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40(S3):S15–S21. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Bowleg L When black+ lesbian+ woman≠ black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles 2008;59(5):312–325. 10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Crenshaw K Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stan L Rev 1990;43:1241. 10.2307/1229039 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Guadamuz TE, et al. A meta-analysis of disparities in childhood sexual abuse, parental physical abuse, and peer victimization among sexual minority and sexual nonminority individuals. Am J Public Health 2011;101(8):1481–1494. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.190009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zou C, Andersen JP. Comparing the rates of early childhood victimization across sexual orientations: Heterosexual, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and mostly heterosexual. PLoS One 2015;10(10):e0139198. 10.1371/journal.pone.0139198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Caceres BA, Markovic N, Edmondson D, Hughes TL. Sexual identity, adverse life experiences, and cardiovascular health in women. The Journal of cardiovascular nursing 2019;34(5):380. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Everett BG, Talley AE, Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Johnson TP. Sexual identity mobility and depressive symptoms: A longitudinal analysis of moderating factors among sexual minority women. Arch Sex Behav 2016;45(7):1731–1744. 10.1007/s10508-016-0755-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Everett BG, Wall M, Shea E, Hughes TL. Mortality risk among a sample of sexual minority women: A focus on the role of sexual identity disclosure. Soc Sci Med 2021;272:113731. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Elgar FJ, Stewart JM. Validity of self-report screening for overweight and obesity. Canadian Journal of Public Health 2008;99(5):423–427. 10.1007/BF03405254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mason TB, Lewis RJ, Heron KE. Indirect pathways connecting sexual orientation and weight discrimination to disordered eating among young adult lesbians. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 2017;4(2):193. 10.1037/sgd0000220 [DOI] [Google Scholar]