Abstract

The association between bone mineral density (BMD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) is not fully understood. We evaluated BMD as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease and specifically atrial fibrillation (AF), acute myocardial infarction (AMI), ischemic (IS) and hemorrhagic stroke (HS) and heart failure (HF) in men and women. This prospective population cohort utilized data on 22 857 adults from the second and third surveys of the HUNT Study in Norway free from CVD at baseline. BMD was measured using single and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in the non-dominant distal forearm and T-score was calculated. Hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated from adjusted cox proportional hazards models. The analyses were sex-stratified, and models were adjusted for age, age-squared, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol use, and education level. Additionally, in women, we adjusted for estrogen use and postmenopause. During a mean follow-up of 13.6 ± 5.7 years, 2 928 individuals (12.8%) developed fatal or non-fatal CVD, 1 020 AF (4.5%), 1 172 AMI (5.1%), 1 389 IS (6.1%), 264 HS (1.1%), and 464 HF (2.0%). For every 1 unit decrease in BMD T-score the HR for any CVD was 1.01 (95% CI 0.98 to 1.04) in women and 0.99 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.03) in men. Point estimates for the four cardiovascular outcomes ranged from slightly protective (HR 0.95 for AF in men) to slightly deleterious (HR 1.12 for HS in men). We found no evidence of association of lower distal forearm BMD with CVD, AF, AMI, IS, HS, and HF.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10654-021-00803-y.

Keyword: Bone mineral density, Cardiovascular disease, Atrial fibrillation, Myocardial infarction, Ischemic stroke, Hemorrhagic stroke

Background

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is a major public health problem and the main cause of loss of disability-adjusted life years and premature death globally [1, 2]. Bone remodeling is a continuous lifelong process involving removal of mineralized bone (bone resorption) followed by the formation of bone matrix that becomes mineralized (bone formation) [3]. Calcification of the arterial tissue in atherosclerosis seems to be regulated by mechanisms similar to those involved in bone remodeling [4], while decreased bone mineral density (BMD) has been associated with development of atherosclerosis in elderly individuals [5]. Other factors such as oxidative stress, inflammation, free radicals and lipid metabolism are all involved in both bone [6, 7] and cardiovascular health [8]. In addition, increased blood calcium and parathyroid hormone levels and dysfunction of sympathetic nervous system have been indicated in abnormal bone remodeling, low BMD and pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation (AF) [9–12].

Previous studies have shown that stroke [13, 14] or heart failure (HF) [15] predisposes patients to lower BMD, mainly due to physical inactivity. Recently, some epidemiological studies reported prospective associations between low BMD and higher incidence of stroke [16, 17], HF [18, 19], acute myocardial infarction (AMI) [20], and mortality [21, 22]. However, previous studies did not distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke [16, 17, 23] that have different etiology and risk factors [24]. Also, to the best of our knowledge, the association with AF has not been previously investigated.

The aim of the present study was to evaluate BMD as a risk factor for any CVD, and specifically AF, AMI, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke and HF in a large population-based study of men and women. We hypothesized that low BMD is associated with increased AF and atherosclerosis risk including AMI and ischemic stroke, with potential sex differences.

Methods

Study design and population

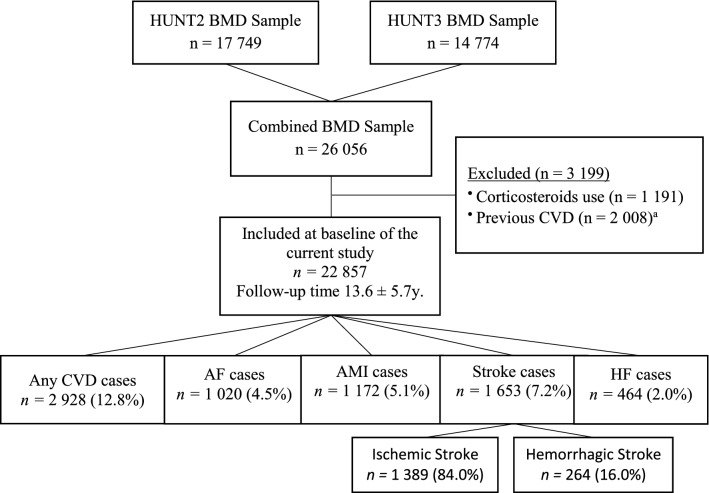

The HUNT Study is the largest Norwegian population-based health study [25]. All adults residing in the northern part of Trøndelag county (n = 94 194 in 1995–1997, n = 93,860 in 2006–2008) were invited to undergo clinical examinations, blood sampling, interviews, and questionnaires in four surveys (HUNT1 1984–86, HUNT2 1995–97,HUNT3 2006–08 and HUNT4 2017–2019) [26]. Bone densitometry was not performed in HUNT1, thus, in the present study, we utilized data from HUNT2 and HUNT3 where a total of 65 215 (69.2% of those invited) and 50 796 (54.1%) individuals participated, respectively. Forearm bone densitometry was performed in 17 749 participants in HUNT2 (21,734 invited; 81.7% participated) and 14 774 participants in HUNT3 (22,490 invited; 65.7% participated) resulting in a total sample of 26 056 adults (Fig. 1). Of the total 26 056 sample, 6 467 individuals (24.8%) participated in both HUNT2 and HUNT3. Participants were selected for bone mineral density measurements in two different ways: 1) a random sample was selected (a 5% random sample from HUNT2 and 10% random sample from HUNT3 among all participants or as part of a 30% random sample from the female birth cohorts or random sample from young-HUNT1 participants) and 2) a symptom sample was selected for the HUNT Lung Study [26], where participants who were asked to participate in spirometry measurements were also asked to participate in bone mineral density measurements. Relevant symptoms included wheezing or breathlessness during the last 12 months at baseline, a history of asthma or ever use of asthma medication. The detailed participant selection process is presented in Figure S1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study population. HUNT (Trøndelag Health Study), BMD (bone mineral density), CVD (cardiovascular disease), AF (atrial fibrillation), AMI (acute myocardial infarction), HF (heart failure). aIncluding a history of AF, AMI, stroke, and HF

Among participants with asthma or COPD we have excluded 1 191 individuals (4.6%) who were current users of inhaled corticosteroids, which could have influenced their BMD measurements [27]. To examine incidence, we excluded subjects with a prior history of cardiovascular diseases including AF, AMI, HF and stroke (n = 2 008, 7.7%), resulting in a total sample of 22,857. Flow chart of participant selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Bone mineral density

In HUNT2, BMD was measured using single-energy X-ray absorptiometry (SXA) (DTX 100, Osteometer Meditech A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark). Daily calibration of the densitometers was performed with equipment-specific phantoms [28]. Measurements were taken in the non-dominant distal forearm, while the dominant arm was used in the case of previous fractures in the non-dominant arm (2.5% of cases). The distal region was 24 mm proximal to the point at which radius and ulna are 8 mm apart [29]. In HUNT3, BMD was measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DTX200, Osteometer Meditech A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) (n = 9 147) and DTX100 (n = 5 627).

BMD was standardized as T-scores. In both sexes separately, we calculated the T-score as observed BMD minus mean BMD from a reference population divided by standard deviation (SD) of reference population. The reference population was a healthy female population (excluded individuals with self-reported osteoporosis, arthritis, hip, or wrist fractures, hyper- or hypothyroidism and use of corticosteroids) aged 20–39 years from the HUNT Study [22]. Further, BMD T-score was categorized according to the WHO criteria as normal (T-score ≥ – 1.0), osteopenia (– 1.0 to – 2.5), and osteoporosis (≤ – 2.5) [30].

Cardiovascular disease ascertainment

Incident cases were ascertained by linking the HUNT data with full hospital records in Nord-Trøndelag County from 1995 to 2015. The diagnoses were based on International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD).

Medical records were manually reviewed by fellow cardiologist and AF was diagnosed based on ICD-10 code I48. The patient was considered as having AF if the electrocardiogram (ECG) could be classified as AF or atrial flutter according to the standard criteria based on the American College of Cardiology consensus guideline [31]. If an ECG scan was not in the digital medical record, the written records were further reviewed for ECG interpretation and, in doubtful cases, the information was evaluated separately by specialist in cardiology and internal medicine, and then discussed in a consensus meeting [32]. In the cases where an ECG was not taken at all, but patients had described irregular heartbeats or periods of fast, irregular pulse, it was not considered AF in our study.

AMI was defined and diagnosed by the caregiving cardiologists and physicians according to the European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology consensus guidelines and consisted of ICD-9 code 410 and ICD-10 codes I21 and I22 [31]. Criteria for AMI included: specific clinical symptoms according to case history information, changes in blood levels of cardiac enzymes, and electrocardiogram changes as defined in the American and European consensus guidelines. If the cardiologists or physicians judged the event to not be a valid AMI, the event was deleted from the registry. A small part of the AMI diagnoses (2%) from medical records have been manually validated [33] and an ongoing validation study (unpublished) found that 92% of the cases (n = 1194) was type 1 AMI.

Ischemic stroke consisted of ICD-9 codes 433 and 434 and ICD-10 code I63 (all positions), while hemorrhagic stroke consisted of ICD-9 codes 430, 431 and 432 and ICD-10 codes I60, I61 and I62. Electronic medical records and diagnostic imaging of hospital admissions for stroke in Norway has been shown to have high sensitivity and positive predictive values in validation studies [34, 35]. HF diagnosis was based on ICD-10 code I50. In addition, we aggregated AMI, any stroke and HF cases into any CVD.

Covariates

A self-administrated questionnaire was used to assess participants’ smoking status (never, former and current), physical activity (inactive, low, medium and high), alcohol use (abstainers, light, moderate and heavy drinkers), education (< 10, 10–12, > 12 years) and medical history of common chronic diseases. A detailed description of the covariates can be found elsewhere [36]. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing body weight (kg) by height (m) squared (kg/m2). Estrogen users were defined as women reporting current or previous use of systemic estrogen pills or patches, while non-users as women reporting “never use” of estrogen. Postmenopausal women were defined as those who self-reported use of estrogen or answered negative to “Do you still menstruate?” question.

Statistical analysis

Baseline characteristics were presented using means (SDs) for continuous variables and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. For the individuals participating at both HUNT2 and HUNT3, HUNT2 was regarded as baseline.

To investigate the prospective association between BMD T-score and outcomes we used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Risk time was calculated from baseline until the first event of interest, death, emigration or end of follow-up (30th November 2015), whichever came first. We used follow-up time as the time scale in our analysis. We tested the proportionality of hazards using log–log curves and Schoenfield's test. We fitted cause-specific models, thus participants with competing events (deaths) were censored at the time of the event. Missing data on covariates were imputed using multiple imputation with chained equations, M = 20.

The non-linearity in the relationship between BMD T-score and outcomes was assessed using the restricted cubic splines with three knots. The number of knots were determined using Akaike (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC). We observed no deviation from linearity by comparing the Cox proportional hazard models with and without cubic spline terms using Wald test and likelihood ratio tests.

We reviewed the literature and performed a Directed Acyclic Graph analysis to select covariates that could cause both BMD and CVD (Figure S2). A minimally adjusted model included age and age-squared (Model 1). The age-squared term was used to account for the possible non-linearity of age influencing the exposure of interest. Further to this, we controlled for BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol use, and education level (Model 2). We additionally adjusted for estrogen and postmenopause in the analysis among women (Model 3). The E-value was calculated to quantify the strength of residual confounding that would require to explain away the estimates [37]. All analyses were prior stratified by sex due to the sex differences in BMD and bone turnover [38].

We performed the data analyses using Stata 13.1 for Windows 10 (StataCorp). The study received ethics approval from the Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics (REK 2015/1462). All study participants gave informed written consent.

Results

A total of 22,857 individuals with BMD data were included in the main analysis. The mean BMD T-score and age were − 1.28 ± 1.82 and 53.25 ± 17.50, respectively for women and 0.002 ± 1.65 and 45.81 ± 15.55, respectively for men. Among women, 3 061 (19.8%) used estrogen and 10,013 (64.7%) were postmenopausal at baseline. Participants categorized as having osteoporosis were more likely to have history of fractures, lower BMI and lower education, be current smokers (men only) and physically inactive (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 22 857 participants stratified by sex

| Characteristic | Female (n = 15 484) | All (− 7.91 to 5.84) (n = 7 373) | Male (n = 7 373) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All (− 9.20 to 3.79) (n = 15 484) | Distal BMD T-score (in categories) | Distal BMD T-score (in categories) | ||||||

| Normal (≥ − 1.0) (n = 7 946) | Osteopenia (− 1.0 to − 2.5) (n = 3 677) | Osteoporosis (≤ − 2.5) (n = 3 861) | Normal (≥ − 1.0) (n = 5 613) | Osteopenia (− 1.0 to − 2.5) (n = 1 346) | Osteoporosis (≤ − 2.5) (n = 414) | |||

| At baseline [mean ± SD or n (%)] | ||||||||

| BMD T-score | − 1.28 ± 1.82 | 0.14 ± 0.80 | − 1.68 ± 0.43 | − 3.8 ± 0.98 | 0.002 ± 1.65 | 0.65 ± 1.21 | − 1.58 ± 0.42 | − 3.63 ± 1.04 |

| BMD | 0.45 ± 0.08 | 0.51 ± 0.04 | 0.43 ± 0.03 | 0.34 ± 0.04 | 0.59 ± 0.07 | 0.62 ± 0.05 | 0.53 ± 0.03 | 0.44 ± 0.05 |

| Fractures | 3 100 (20.0) | 972 (12.2) | 805 (21.9) | 1 323 (34.3) | 1 290 (17.5) | 913 (16.3) | 293 (21.8) | 84 (20.3) |

| Missing | 623 (4.0) | 148 (1.9) | 169 (4.6) | 306 (7.9) | 215 (2.9) | 134 (2.4) | 41 (3.1) | 40 (9.7) |

| Smoking | ||||||||

| Never | 7 443 (48.1) | 3 405 (42.8) | 1 813 (49.3) | 2 225 (57.6) | 2 686 (36.4) | 2 235 (39.8) | 385 (28.6) | 66 (15.9) |

| Former | 3 337 (21.5) | 1 837 (23.1) | 802 (21.8) | 698 (18.1) | 2 205 (29.9) | 1 600 (28.5) | 436 (32.4) | 169 (40.8) |

| Current | 4 350 (28.1) | 2 627 (33.1) | 973 (26.5) | 750 (19.4) | 2 400 (32.6) | 1 728 (30.8) | 504 (37.4) | 168 (40.6) |

| Missing | 354 (2.3) | 77 (1.0) | 89 (2.4) | 188 (4.9) | 82 (1.1) | 50 (0.9) | 21 (1.6) | 11 (2.7) |

| Education | ||||||||

| < 10y | 6 420 (41.5) | 2 186 (27.5) | 1 743 (47.4) | 2 491 (64.5) | 1 940 (26.3) | 1 310 (23.3) | 433 (32.2) | 197 (47.6) |

| 10–12y | 5 466 (35.3) | 3 676 (46.3) | 1 134 (30.8) | 656 (17.0) | 3 870 (52.5) | 3 142 (56.0) | 600 (44.6) | 128 (30.9) |

| > 12y | 2 632 (17.0) | 1 848 (23.3) | 576 (15.7) | 208 (5.4) | 1 349 (18.3) | 1 051 (18.7) | 260 (19.3) | 38 (9.2) |

| Missing | 966 (6.2) | 236 (2.9) | 224 (6.1) | 506 (13.1) | 214 (2.9) | 110 (2.0) | 53 (3.9) | 51 (12.3) |

| Physical activity | ||||||||

| Inactive | 2 838 (18.3) | 1 350 (17.0) | 652 (17.7) | 836 (21.6) | 1 283 (17.4) | 958 (17.1) | 244 (18.0) | 81 (19.6) |

| Low | 4 227 (27.3) | 2 268 (28.5) | 1 059 (28.8) | 900 (23.3) | 1 605 (21.8) | 1 212 (21.6) | 312 (23.2) | 81 (19.6) |

| Medium | 5 208 (33.6) | 3 973 (37.4) | 1 231 (33.5) | 1 004 (26.0) | 2 489 (33.7) | 1 906 (33.9) | 456 (33.9) | 127 (30.7) |

| High | 849 (5.5) | 624 (7.9) | 157 (4.3) | 68 (1.8) | 1 008 (13.7) | 826 (14.7) | 155 (11.5) | 27 (6.5) |

| Missing | 2 362 (15.3) | 731 (9.2) | 578 (15.7) | 1 053 (27.3) | 988 (13.4) | 711 (12.7) | 179 (13.3) | 98 (23.6) |

| Alcohol use | ||||||||

| Abstainers | 7 532 (48.6) | 3 943 (37.0) | 1 931 (52.5) | 2 658 (68.8) | 1 713 (23.2) | 1 179 (21.0) | 357 (26.5) | 177 (42.7) |

| Light | 6 527 (42.2) | 4 239 (53.4) | 1 430 (38.9) | 858 (22.2) | 3 708 (50.3) | 2 895 (51.6) | 656 (48.8) | 157 (37.9) |

| Moderate/Heavy | 982 (6.3) | 666 (8.4) | 209 (5.7) | 107 (2.8) | 1 822 (24.7) | 1 478 (26.3) | 298 (22.1) | 46 (11.3) |

| Missing | 443 (2.9) | 98 (1.2) | 107 (2.9) | 238 (6.2) | 130 (1.8) | 61 (1.1) | 35 (2.6) | 34 (8.1) |

| Age (y) | 53.25 ± 17.50 | 43.04 ± 13.60 | 56.58 ± 15.52 | 71.06 ± 8.61 | 45.81 ± 15.55 | 42.91 ± 13.62 | 51.02 ± 16.94 | 68.12 ± 12.55 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26.71 ± 4.69 | 26.66 ± 4.86 | 26.90 ± 4.75 | 26.64 ± 4.27 | 26.76 ± 3.83 | 27.01 ± 3.77 | 26.10 ± 3.89 | 25.46 ± 3.98 |

| Missing | 63 (0.4) | 18 (0.2) | 14 (0.4) | 31 (0.8) | 18 (0.2) | 7 (0.1) | 6 (0.4) | 5 (1.2) |

| Estrogen usea | 3 061 (19.8) | 1 562 (19.7) | 882 (24.0) | 617 (16.0) | – | – | – | – |

| Missing | 4 050 (26.2) | 2 048 (25.8) | 836 (22.7) | 1 166 (30.2) | – | – | – | – |

| Postmenopausea | 10 013 (64.7) | 3 943 (49.6) | 2 804 (76.3) | 3 266 (84.6) | – | – | – | – |

| Missing | 2 327 (15.0) | 1 530 (19.3) | 383 (10.4) | 414 (10.7) | – | – | – | – |

| At follow-up [n (%)] | ||||||||

| Any CVD | 2 093 (13.5) | 500 (6.3) | 563 (15.3) | 1 030 (26.7) | 835 (11.3) | 523 (9.3) | 214 (15.9) | 98 (23.7) |

| AF | 670 (4.3) | 211 (2.7) | 184 (5.0) | 275 (7.1) | 350 (4.8) | 248 (4.4) | 74 (5.5) | 28 (6.8) |

| Ischemic stroke | 1 042 (6.7) | 232 (2.9) | 293 (8.0) | 517 (13.4) | 347 (4.7) | 211 (3.8) | 90 (6.7) | 46 (11.1) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 192 (1.2) | 46 (0.6) | 51 (1.4) | 95 (2.5) | 72 (1.0) | 41 (0.7) | 19 (1.4) | 12 (2.9) |

| AMI | 772 (5.0) | 196 (2.5) | 198 (5.4) | 378 (9.8) | 400 (5.4) | 254 (4.5) | 102 (7.6) | 44 (10.6) |

| HF | 349 (2.3) | 79 (1.0) | 93 (2.5) | 177 (4.6) | 115 (1.6) | 72 (1.3) | 31 (2.3) | 12 (2.9) |

SD (standard deviation), BMD (bone mineral density), BMI (body mass index), CVD (cardiovascular disease), AF (atrial fibrillation), AMI (acute myocardial infarction), HF (heart failure)

aPercentage expressed among women only

Association of BMD and cardiovascular disease

Among women free of any CVD events at baseline, there were 2 093 incident cases of CVD (13.5%), 670 AF (4.3%), 772 AMI (5.0%), 1 042 ischemic stroke (6.7%), 192 hemorrhagic stroke (1.2%), and 349 HF (2.3%). Among men free of any CVD events at baseline, there were 835 incident cases of CVD (11.3%), 248 AF (4.8%), 400 AMI (5.4%), 347 ischemic stroke (4.7%), 72 hemorrhagic stroke (1.0%), and 115 HF (1.6%).

We found no evidence for association between 1 unit decrease in distal forearm BMD T-score and CVD, AF, AMI, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, and HF in men and women (Table 2). Among women the HRs (95% CI) were 1.01 (0.98–1.04) for CVD, 0.99 (0.94–1.05) for AF, 0.99 (0.94–1.04) for AMI, 1.03 (0.98–1.07) for ischemic stroke, 1.05 (0.95–1.16) for hemorrhagic stroke, and 1.02 (0.94–1.10) for HF (Model 2, Table 2). Similar results were observed in Model 3 (Table 2). Among men the HRs were 0.99 (0.94–1.03) for CVD, 0.95 (0.88–1.02) for AF, 0.96 (0.90–1.03) for AMI, 1.03 (0.96–1.11) for ischemic stroke, 1.12 (0.96–1.32) for hemorrhagic stroke, and 0.97 (0.84–1.11) for HF (Model 2, Table 2).

Table 2.

Associations between distal forearm bone mineral density T-score and the risk of cardiovascular disease stratified by sex

| Any CVD (n = 2928) | AF (n = 1 020) | AMI (n = 1172) | Ischemic stroke (n = 1389) | Hemorrhagic stroke (n = 264) | HF (n = 464) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female (n = 15,484) | ||||||

| No. of cases (%) | 2 093 (13.5) | 670 (4.3) | 772 (5.0) | 1 042 (6.7) | 192 (1.2) | 349 (2.3) |

| Model 1 | 0.99 (0.97–1.03) | 0.96 (0.92–1.02) | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 1.02 (0.97–1.06) | 1.05 (0.96–1.16) | 0.99 (0.92–1.07) |

| Model 2 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) | 1.02 (0.94–1.10) |

| Model 3 | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 0.99 (0.94–1.05) | 0.99 (0.94–1.04) | 1.03 (0.98–1.07) | 1.05 (0.95–1.16) | 1.02 (0.94–1.10) |

| E-value (CI) for Model 3 | 1.09 (1.00) | 1.05 (1.00) | 1.12 (1.00) | 1.19 (1.00) | 1.28 (1.00) | 1.15 (1.00) |

| Male (n = 7 373) | ||||||

| No. of cases (%) | 835 (11.3) | 248 (4.8) | 400 (5.4) | 347 (4.7) | 72 (1.0) | 115 (1.6) |

| Model 1 | 0.99 (0.94–1.03) | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | 1.02 (0.95–1.10) | 1.11 (0.95–1.30) | 0.95 (0.83–1.09) |

| Model 2 | 0.99 (0.94–1.03) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 0.96 (0.90–1.03) | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 1.12 (0.96–1.32) | 0.97 (0.84–1.11) |

| E-value (CI) for Model 2 | 1.13 (1.00) | 1.30 (1.00) | 1.25 (1.00) | 1.21 (1.00) | 1.49 (1.00) | 1.22 (1.00) |

BMD (bone mineral density), BMI (body mass index), CVD (cardiovascular disease), AF (atrial fibrillation), AMI (acute myocardial infarction), HF (heart failure)

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals were derived from Cox proportional hazards models

Model 1 adjusted for age, age-squared

Model 2 adjusted for age, age-squared, BMI, physical activity, smoking status, alcohol use, and education level

Model 3 (female only) adjusted for model 2 and estrogen use and postmenopause

Hazard ratios for 1 unit decrease in distal bone mineral density T-score

Discussion

In this prospective study including 22 857 adults, there was no evidence of an association between BMD and CVD. Specifically, for each CVD end points, we did observe an indication of a small protective effect on atrial fibrillation and actue myocardial infarction in men, and a small increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke in men, however these associations lacked precision.

There is some previous evidence available for an association between BMD and CVD incidence including myocardial infarction or coronary artery disease [20, 39], stroke [16, 17, 23] and HF [18, 19]. A meta-analysis of prospective studies found an association between low BMD and CVD, and death due to CVD, however after adjustment for publication bias the estimates were attenuated [40]. No large-scale population-based studies have been conducted in Europeans. However, regarding more specific CVD outcomes, one small prospective study observed a modest increased risk of AMI for 1 SD decrease in femoral neck and total hip BMD after adjusting for BMI, age, diabetes, hypertension, smoking and hypertriglyceridemia [20]. Additionally, the Cardiovascular Health Study found lower total hip BMD to be associated with 13% higher HF risk in non-black men, but not women [19].

All previous studies that examined stroke incidence did not distinguish between ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke [16, 17, 23]. Although, in line with previous studies, we found a slightly higher risk of overall stroke for every 1 SD decrease in BMD (HR 1.05, 95% CIs 0.98 to 1.12 in men), the increase was not seen when looking at ischemic stroke specifically. Previously, it has been hypothesized that higher stroke risk is due to increased bone demineralization that leads to vascular calcification and accelerated atherosclerosis [4, 5]. Our study suggests that the overall association with stroke might be due to the hemorrhagic type. This is also supported by the observed null or protective association with acute myocardial infarction that shares common atherosclerotic pathways with ischemic stroke.

Hemorrhagic stroke has different risk factors and etiology than the ischemic type [24]. For example, high blood pressure and alcohol use has a more direct linear relationship with hemorrhagic than ischemic stroke. Also, subarachnoid hemorrhage, a subtype of hemorrhagic stroke, is most caused by a head injury. A previous study found that participants who had experienced a hemorrhagic stroke were at a higher hip/femur fracture risk compared with those who had experienced an ischemic stroke [41]. Poor bone health is a major risk factor for falls, while falls itself is the main cause of fractures and traumatic head injuries [42]. Therefore, there might be a link between low BMD and higher risk of stroke due to head injury. In addition, poor bone health in pre-menopause women could indicate fragility and higher risk of slip and falls, whereas low BMD in postmenopausal is more commonly seen due to hormonal changes [43]. Considering that hemorrhagic stroke is associated with poorer outcomes and 1.5-fold higher mortality than ischemic stroke [44, 45], further studies are needed to confirm our findings and clarify potential mechanisms.

To our knowledge, there has been no earlier studies investigating the association between BMD and atrial fibrillation. Abnormal bone remodeling and increased bone resorption can cause excess release of calcium from the bone mass leading to hypercalcemia [46]. Calcium ions play a major role in cellular electrophysiology and high levels are associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease [47]. However, blood calcium levels in relation to AF risk is less known and parathyroid hormones with complex calcium regulatory system play a role [48]. In addition, the use of bisphosphonates, a first-line therapeutic agents for treating osteoporosis, have been found to increase AF risk in a randomized clinical controlled trial [49]. However, a meta-analysis of three RCTs and four observational studies did not find a higher risk of AF in bisphosphonate users [50]. In our study, we did not find any evidence for increased AF risk with lower BMD, while serum calcium levels and bisphosphonate use were not assessed.

Our large population-based study had a long follow-up, information on a wide range of confounders, high participation rate and carefully reviewed hospital and register information.

We identify several limitations of this study. Although, total hip dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is the gold standard for bone mineral density measurement with excellent prediction of hip fractures and future osteoporosis, we have used single and dual X-ray absorptiometry of the distal forearm. Forearm was chosen as a measurement site due to practical reasons such as reduced radiation dose especially for women in fertile age, easy and readily standardized assessment, less expensive equipment and shorted duration of the measurement (no undressing needed), all of which makes it more suitable for large-scale population-based studies [51]. Also, forearm measurements have high accuracy of 2% compared to an accuracy error of 8–10% for spine site [52, 53]. Forearm has high accuracy due to the limited amount of surrounding tissue and the precision of bone mass measurements [54]. In addition, forearm BMD measures have been shown to be highly correlated with whole-body BMD and has same accuracy and predictive ability of generalized osteoporotic bone loss at any site [51, 55]. Also, previous studies showed that forearm BMD is a good predictor of future fractures at any site in women [56] and men [57]. Lastly, by utilizing the non-dominant forearm we reduced potential residual confounding by leisure and work-related physical activity [54]. Overall, forearm is a valid site in assessing whole body BMD and fractures risk within the population.

Secondly, DTX100 (SXA) was used in HUNT2 and DTX200 (DXA) in HUNT3. The agreement between them has been found to be acceptable by a previous validation study within HUNT sample, which found that DXA measured slightly higher BMD value than the SXA with the mean difference of 4.5% per g/cm2 (unpublished). Also, a previous study in Norway found that Root Mean Square Standard Deviation (RMS SD) for SXA and DXA forearm was 4.6 (4.2–5.1) and 6.8 (6.1–7.4), respectively, and the corresponding coefficients of variation was 1.0% and 1.4% [58].

The third limitation is that stroke and AMI cases have been ascertained through hospital recorded ICD codes but, unlike atrial fibrillation, not all cases were manually validated. However, validation studies of stroke and AMI from electronic medical records in Norway reported high sensitivity and positive predictive values [33–35]. Nevertheless, lack of manual review and no validation studies for heart failure diagnosis is a major limitation in this study. In addition, observational studies are generally susceptible to confounding. However, for residual confounding to be influencing our results considerably a potential confounder would have to be strongly associated with both BMD and the outcome and be unrelated to the confounders already included in our models. Finally, for each association we calculated the E value [37], which supported that remaining residual confounding was unlikely to influence our results.

Conclusion

Our findings contribute to the knowledge of bone health and cardiovascular disease. We found no evidence of risk of cardiovascular diseases in women and men with lower distal forearm bone mineral density. Although we did not observe statistically significant associations between BMD and cardiovascular outcomes, our point estimates of hazard ratios may be compatible with a small protective effect on atrial fibrillation and actue myocardial infarction in men, and a small increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke in men. Future studies are needed to replicate these findings.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The HUNT Study is a collaboration between HUNT Research Centre (Faculty of Medicine and Health Science, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trøndelag County Council, Central Norway Health Authority and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health.

Funding

Open access funding provided by NTNU Norwegian University of Science and Technology (incl St. Olavs Hospital - Trondheim University Hospital). This work was supported by Nasjonalforeningen for folkehelsen (Norway National Association for Public Health) [grant number 10705]. LB and BMB works in a research unit funded by the K.G. Jebsen Center for Genetic Epidemiology funded by Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen; Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU; The Liaison Committee for education, research and innovation in Central Norway; and the Joint Research Committee between St. Olavs Hospital and the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, NTNU; The Lung Study got non-demanding funding for bone densitometry by AstraZeneca for HUNT2 and HUNT3. In HUNT2 the Osteoporosis study, performing 1/3 of the measurements got funding by” Norske Kvinners Sanitetsforening”.

Declaration

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Laxmi Bhatta, Email: laxmi.bhatta@ntnu.no.

Ben M. Brumpton, Email: ben.brumpton@ntnu.no

References

- 1.McKay J, Mensah GA, Greenlund K. The atlas of heart disease and stroke. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakshaug S, Selmer RM, Graff-Iversen S. Cardiovascular disease in Norway—Public health report 20142016 18.04.2016.

- 3.Hadjidakis DJ, Androulakis II. Bone remodeling. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1092:385–396. doi: 10.1196/annals.1365.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farhat GN, Cauley JA. The link between osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Clin Cases Min Bone Metab. 2008;5(1):19–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ye C, Xu M, Wang S, et al. Decreased bone mineral density is an independent predictor for the development of atherosclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS ONE. 2016;11(5):e0154740-e. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0154740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domazetovic V, Marcucci G, Iantomasi T, Brandi ML, Vincenzini MT. Oxidative stress in bone remodeling: role of antioxidants. Clin Cases Min Bone Metab. 2017;14(2):209–216. doi: 10.11138/ccmbm/2017.14.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sprini D, Rini GB, Di Stefano L, Cianferotti L, Napoli N. Correlation between osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease. Clin Cases Min Bone Metab. 2014;11(2):117–119. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1685–1695. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.He JY, Jiang LS, Dai LY. The roles of the sympathetic nervous system in osteoporotic diseases: A review of experimental and clinical studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2011;10(2):253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tuchendler D, Bolanowski M. The influence of thyroid dysfunction on bone metabolism. Thyroid Res. 2014;7(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s13044-014-0012-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji-Ye H, Xin-Feng Z, Lei-Sheng J. Autonomic control of bone formation: its clinical relevance. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;117:161–171. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-444-53491-0.00014-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Traube E, Coplan NL. Embolic risk in atrial fibrillation that arises from hyperthyroidism: review of the medical literature. Tex Heart Inst J. 2011;38(3):225–228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kapral MK, Fang J, Alibhai SM, et al. Risk of fractures after stroke: results from the Ontario stroke registry. Neurology. 2017;88(1):57–64. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000003457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jorgensen L, Engstad T, Jacobsen BK. Bone mineral density in acute stroke patients: low bone mineral density may predict first stroke in women. Stroke. 2001;32(1):47–51. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xing W, Lv X, Gao W, et al. Bone mineral density in patients with chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2018;13:343–353. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S154356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nordstrom A, Eriksson M, Stegmayr B, Gustafson Y, Nordstrom P. Low bone mineral density is an independent risk factor for stroke and death. Cerebrovasc Dis (Basel, Switzerland) 2010;29(2):130–136. doi: 10.1159/000262308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou R, Liu D, Li R, et al. Low bone mass is associated with stroke in Chinese postmenopausal women: the Chongqing osteoporosis study. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2015;71(3):1695–1701. doi: 10.1007/s12013-014-0392-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pfister R, Michels G, Sharp SJ, Luben R, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT. Low bone mineral density predicts incident heart failure in men and women: the EPIC (European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition)-Norfolk prospective study. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(4):380–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fohtung RB, Brown DL, Koh WJH, et al. Bone mineral density and risk of heart failure in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3):e004344. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wiklund P, Nordstrom A, Jansson JH, Weinehall L, Nordstrom P. Low bone mineral density is associated with increased risk for myocardial infarction in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2012;23(3):963–970. doi: 10.1007/s00198-011-1631-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauger AV, Bergland A, Holvik K, Ståhle A, Emaus N, Strand BH. Osteoporosis and osteopenia in the distal forearm predict all-cause mortality independent of grip strength: 22-year follow-up in the population-based Tromsø Study. Osteoporos Int. 2018;29(11):2447–2456. doi: 10.1007/s00198-018-4653-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vikjord SAA, Brumpton BM, Mai XM, Bhatta L, Vanfleteren L. Langhammer A (2019) The Association of Bone Mineral Density with mortality in a COPD Cohort The HUNT Study. Norway. Copd. 2019;16(5–6):321–329. doi: 10.1080/15412555.2019.1685482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mussolino ME, Madans JH, Gillum RF. Bone mineral density and stroke. Stroke. 2003;34(5):e20–e22. doi: 10.1161/01.Str.0000065826.23815.A5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boehme AK, Esenwa C, Elkind MS. Stroke risk factors, genetics, and prevention. Circ Res. 2017;120(3):472–495. doi: 10.1161/circresaha.116.308398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Holmen J, Midthjell K, Forsen L, Skjerve K, Gorseth M, Oseland A. A health survey in Nord-Trondelag 1984–86. Participation and comparison of attendants and non-attendants. Tidsskrift for den Norske laegeforening. 1990;110(15):1973–1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krokstad S, Langhammer A, Hveem K, et al. Cohort profile: the HUNT Study, Norway. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(4):968–977. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langhammer A, Norjavaara E, de Verdier MG, Johnsen R, Bjermer L. Use of inhaled corticosteroids and bone mineral density in a population based study: the Nord-Trondelag Health Study (the HUNT Study) Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(8):569–579. doi: 10.1002/pds.941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langhammer A, Forsmo S, Lilleeng S, Johnsen R, Bjermer L. Effect of inhaled corticosteroids on forearm bone mineral density: the HUNT Study. Norway Respir Med. 2007;101(8):1744–1752. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forsmo S, Langhammer A, Forsen L, Schei B. Forearm bone mineral density in an unselected population of 2,779 men and women—The HUNT Study. Norway Osteoporos Int. 2005;16(5):562–567. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1726-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.WHO. WHO Scientific Group on the assessment of osteoporosis at primary health care level 2004 [cited 2017 Nov 21]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chp/topics/Osteoporosis.pdf.

- 31.Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myocardial infarction redefined—a consensus document of The Joint European Society of Cardiology/American College of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36(3):959–969. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(00)00804-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Malmo V, Langhammer A, Bønaa KH, Loennechen JP, Ellekjaer H. Validation of self-reported and hospital-diagnosed atrial fibrillation: the HUNT study. Clin Epidemiol. 2016;8:185–193. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S103346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olson KA, Beatty AL, Heidecker B, et al. Association of growth differentiation factor 11/8, putative anti-ageing factor, with cardiovascular outcomes and overall mortality in humans: analysis of the Heart and Soul and HUNT3 cohorts. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(48):3426–3434. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Øie LR, Madsbu MA, Giannadakis C, et al. Validation of intracranial hemorrhage in the Norwegian Patient Registry. Brain Behav. 2018;8(2):e00900. doi: 10.1002/brb3.900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ellekjaer H, Holmen J, Kruger O, Terent A. Identification of incident stroke in Norway: hospital discharge data compared with a population-based stroke register. Stroke. 1999;30(1):56–60. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.30.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cepelis A, Brumpton BM, Malmo V, et al. Associations of asthma and asthma control with atrial fibrillation risk: results from the nord-trøndelag health study (hunt) JAMA Cardiol. 2018 doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linden A, Mathur MB, VanderWeele TJ. Conducting sensitivity analysis for unmeasured confounding in observational studies using E-values: The evalue package. Stand Genomic Sci. 2020;20(1):162–175. doi: 10.1177/1536867X20909696. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alswat KA. Gender disparities in osteoporosis. J Clin Med Res. 2017;9(5):382–387. doi: 10.14740/jocmr2970w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee HT, Shin J, Min SY, et al. Relationship between bone mineral density and a 10-year risk for coronary artery disease in a healthy Korean population: the Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2008–2010. Coron Artery Dis. 2015;26(1):66–71. doi: 10.1097/mca.0000000000000165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veronese N, Stubbs B, Crepaldi G, et al. Relationship between low bone mineral density and fractures with incident cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Bone Min Res. 2017;32(5):1126–1135. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.3089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pouwels S, Lalmohamed A, Leufkens B, et al. Risk of hip/femur fracture after stroke: a population-based case-control study. Stroke. 2009;40(10):3281–3285. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.109.554055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jager TE, Weiss HB, Coben JH, Pepe PE. Traumatic brain injuries evaluated in U.S. emergency departments, 1992–1994. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7(2):134–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb00515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Finkelstein JS, Brockwell SE, Mehta V, et al. Bone mineral density changes during the menopause transition in a multiethnic cohort of women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(3):861–868. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-1876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Andersen KK, Olsen TS, Dehlendorff C, Kammersgaard LP. Hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes compared: stroke severity, mortality, and risk factors. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2068–2072. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.108.540112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bhalla A, Wang Y, Rudd A, Wolfe CD. Differences in outcome and predictors between ischemic and intracerebral hemorrhage: the South London Stroke Register. Stroke. 2013;44(8):2174–2181. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.113.001263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carroll MF, Schade DS. A practical approach to hypercalcemia. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(9):1959–1966. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolland MJ, Avenell A, Baron JA, et al. Effect of calcium supplements on risk of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular events: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;341:c3691. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Venetucci L, Denegri M, Napolitano C, Priori SG. Inherited calcium channelopathies in the pathophysiology of arrhythmias. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9(10):561–575. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Black DM, Delmas PD, Eastell R, et al. Once-yearly zoledronic acid for treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(18):1809–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa067312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loke YK, Jeevanantham V, Singh S. Bisphosphonates and atrial fibrillation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Saf. 2009;32(3):219–228. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200932030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Augat P, Fuerst T, Genant HK. Quantitative bone mineral assessment at the forearm: a review. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8(4):299–310. doi: 10.1007/s001980050068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosvold Berntsen GK, Fonnebo V, Tollan A, Sogaard AJ, Joakimsen RM, Magnus JH. The Tromso study: determinants of precision in bone densitometry. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1104–1112. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(00)00234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hassager C, Jensen SB, Gotfredsen A, Christiansen C. The impact of measurement errors on the diagnostic value of bone mass measurements: theoretical considerations. Osteoporos Int. 1991;1(4):250–256. doi: 10.1007/bf03187470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Augestad LB, Schei B, Forsmo S, Langhammer A, Flanders WD. The association between physical activity and forearm bone mineral density in healthy premenopausal women. J Womens Health. 2004;13(3):301–313. doi: 10.1089/154099904323016464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rajaei A, Dehghan P, Ariannia S, Ahmadzadeh A, Shakiba M, Sheibani K. Correlating Whole-Body Bone Mineral Densitometry Measurements to Those From Local Anatomical Sites. Iran J Radiol. 2016;13(1):e25609-e. doi: 10.5812/iranjradiol.25609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hui SL, Slemenda CW, Johnston CC., Jr Baseline measurement of bone mass predicts fracture in white women. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111(5):355–361. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-5-355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Melton LJ, 3rd, Atkinson EJ, O'Connor MK, O'Fallon WM, Riggs BL. Bone density and fracture risk in men. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13(12):1915–1923. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.12.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Forsen L, Berntsen GK, Meyer HE, Tell GS, Fonnebo V. Differences in precision in bone mineral density measured by SXA and DXA: the NOREPOS study. Eur J Epidemiol. 2008;23(9):615–624. doi: 10.1007/s10654-008-9271-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.