Abstract

In this article a new reaction mode of palladium/norbornene (Pd/NBE) cooperative catalysis is reported involving the selective coupling of two different carbon-based electrophiles for vicinal double C−H functionalization of five-membered heteroarenes in a site-selective and redox-neutral manner. The key is to use alkynyl bromides as the second electrophile, which allows vicinal difunctionalization of a wide range of heteroarenes including pyrroles, thiophenes and furans at their C4 and C5 positions. One- or two-step tetrafunctionalizations of simple pyrrole and thiophene have also been realized. The C2-substituted NBEs prove most effective in these reactions, and the mechanistic exploration discloses the origin of the high selectivity of this transformation. Synthetic utility of this method has been exemplified in the concise preparations of thiophene-containing organic materials and a protein kinase inhibitor analogue. Preliminary success has also been achieved in a direct annulation event, using a tethered ketone as the second electrophile.

Keywords: palladium, norbornene, difunctionalization, heteroarene, redox-neutral

Graphical Abstract

A new reaction mode of the Pd/NBE cooperative catalysis is developed involving coupling of two different carbon-based electrophiles for vicinal difunctionalization of five-membered heteroarenes. The reaction is site-selective and redox-neutral, tolarating air, moisture and a broad scope of functional groups, which makes this method attractive for modular synthesis of complex heteroarene-containing molecules.

Introduction

Arenes and heteroarenes with multiple different substituents are prevalent in functional molecules, such as drugs and organic materials (Figure 1).[1] While various arene-functionalization approaches have been established, direct site-selective installation of multiple different functional groups (FGs) via sequential C−H activation,[2] which is arguably one of the most straightforward approaches, remains a formidable challenge.[3] Recently, the palladium/norbornene (Pd/NBE) cooperative catalysis, originally discovered by Catellani,[4] has emerged as an increasingly useful method for introducing vicinal FGs to aromatic rings in one step.[5] In a typical Catellani reaction, through forming a unique aryl-norbornyl-palladacycle (ANP) intermediate, an electrophile and a nucleophile (including olefins) are coupled regioselectively at the arene ortho and ipso positions, respectively (Scheme 1A). This is because the original ortho position in the ANP intermediate is more electron-rich, therefore more reactive with electrophiles, whereas the original ipso carbon tends to undergo regular cross-couplings with nucleophiles in the reaction.[5j] However, the need of both electrophilic and nucleophilic reactants present in the same reaction vessel has inevitably raised concerns of compatibility, which further limits the type of FGs that can be tolerated. In addition, the presence of nucleophiles can also render regular cross couplings to compete with the Catellani process.

Figure 1.

Examples of polysubstituted heterocycles.

Scheme 1.

Vicinal functionalizations via the Pd/NBE cooperative catalysis.

On the other hand, the nucleophile-free Pd/NBE catalysis has been developed through a Pd(II)-initiated N−H palladation[6], C−H activation[7] or transmetallation[8] processes, in which protodepalladation takes place at the arene ipso position to regenerate the Pd(II) catalyst, though only one type of FGs can be introduced at once in these reactions. Thus, one intriguing question is whether two different aprotic electrophiles could be coupled site-selectively through the Pd/NBE-catalyzed vicinal double C−H functionalization, which, to our knowledge, has not yet been established (Scheme 1B). In 2009, Lautens reported the first example of terminating the arene ipso position with a tethered carbonyl electrophile based on aryl iodide substrates (Scheme 1C), whereas additional reductant was added for Pd(0) reformation.[9a] In 2019, a direct ortho arylation/ipso Heck reaction of thiophenes was developed by us (Scheme 1D);[2h] given that the catalytic cycle is closed by reacting with an olefin, an oxidative process is required to regenerate the Pd(II) catalyst. More recently, elegant work by Luan showed two different electrophiles can be coupled in a sequential manner at both ortho positions (Scheme 1E), in which nucleophiles are still needed for the ipso quench.[10] In this full article, we describe the development of a new reaction mode in the Pd/NBE catalysis, involving direct coupling of two different carbon electrophiles with various five-membered heteroarenes, including pyrroles, furans and thiophenes, at their C4 and C5 positions (Scheme 1F). This transformation provides complementary reactivity and allows streamlined synthesis of polysubstituted heteroarenes in a redox-neutral manner.

In comparison to the conventional Catellani processes, substantial challenges associated with this double-electrophile coupling could be envisioned (Scheme 2). First, it is nontrivial to differentiate the reactivity between two electrophiles[10] in this reaction. In particular, success of this transformation requires one electrophile to selectively react with the ANP and the other one to react with the aryl-Pd(II)-X (X: anionic ligand) intermediate after NBE extrusion (Step C vs Step F). By contrast, the prior ipso protonation reactions do not have such a selectivity issue as the competing reaction between the ANP and proton will generate the previous intermediate instead of leading to a side-reaction. Second, success of this double-electrophile coupling requires facile ipso C−H palladation to initiate the reaction (step A); from the microscopic reversibility viewpoint, the reverse ipso protodepalladation should also have a low kinetic barrier.[11] As a result, the ipso protonation can compete with the second electrophile to give mono-ortho-functionalized side-products (Step G vs Step D). Third, given that the second electrophile needs to efficiently react with the aryl-Pd(II)-X intermediate, it thus can compete with the NBE insertion for the direct mono-ipso-functionalized side-product (Step E vs Step B). Therefore, to realize the proposed double C−H functionalization with dual electrophiles, the following three criteria must be met: a) the first electrophile needs to be more reactive than the second one when reacting with the ANP; b) the second electrophile should prefer to react with the aryl-Pd(II)-X intermediates, instead of the ANP; c) the aryl-Pd(II)-X intermediate should undergo faster NBE insertion than its reaction with the second electrophile.

Scheme 2.

Potential challenges associated with the proposed reaction.

Results and Discussion

Reaction discovery and optimization:

We hypothesized one key for the success of this transformation would be the choice of the second electrophile, which should react in a different mode from the first electrophile. Given that linear aryl-Pd(II)-X intermediates are generally less electron-rich and less rigid than the corresponding five-membered ANP, they are expected to undergo faster migratory insertion with alkenes or alkynes than the ANP.[12] Hence, π-type electrophiles could be most suitable as the second electrophile, as they would react faster with the aryl-Pd(II)-X than the ANP via 2π-insertion. In addition, structurally modified NBEs that give faster migratory insertion could be beneficial to minimize premature ipso functionalization.[5k]

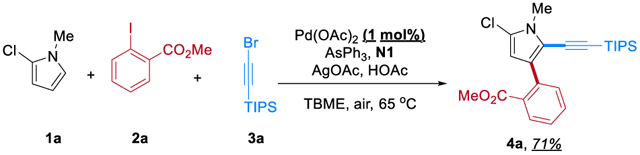

To test the hypothesis, alkynyl bromide 3a,[13] known to react with aryl-Pd(II)-X species through 2π-insertion followed by a unique trans β-bromide elimination,[13e,14] was employed as the second electrophile. Methyl 2-iodobenzoate (2a) was chosen as the first electrophile, as the coordinating ester moiety should promote the selective reaction with the ANP.[2h,7b] The reaction was first explored with 2-chloro-1-methylpyrrole (1a) as the model substrate (Table 1). After careful evaluation of various reaction parameters, the desired direct ortho arylation/ipso alkynylation product 4a was ultimately isolated in 78% yield (entry 1). First, the Pd(OAc)2/AsPh3 combination proved to be optimal;[2h,7b,8a] no desired product was observed in the absence of Pd or the ligand (entries 2 and 3). Phosphine-based ligands were much less effective (entries 4 and 5). NBE also proved to be essential (entry 6). The C2 trifluoroethyl amide-substituted NBE (N1) was found most efficient and most selective for the model reaction (entry 7). While other C2-substiuted NBEs[15] also gave relatively good yields, their selectivity was worse with more direct ipso alkynylation and other side-products. This is consistent with our prior mechanistic study, which suggested that C2-amide NBEs exhibit lower migratory insertion barriers.[16] In contrast, much reduced reactivity was observed with C1-substituted NBEs (N7 and N8),[17] likely due to their increased steric hindrance. The C5-substituted N9[18] and C5,C6-disubstituted N10[19] also gave inferior results. Although simple NBE (N11) appears to produce the desired product in good yield with minimal side-product 4a’, it nevertheless generated a notably amount of multi-alkynylation side-products (7%), which indicates poorer selectivity than N1. The silver salt was beneficial, likely serving as a halide scavenger to promote the oxidative addition of aryl iodide 2a and/or the coupling with alkynyl bromide 3a (entry 8).[20] Reducing the loading of 2a and AgOAc to one equivalent in a 1:1 ratio can afford 57% yield (entry 9) and replacing AgOAc with CsOAc under an N2 atmosphere still provided 18% yield (entry 10), suggesting that the role of AgOAc is unlikely to be an oxidant. Finally, the addition of 5 equivalents of HOAc improved the yield (entry 11) possibly through promoting the initial C−H palladation on the substrate.[21] It is noteworthy that the reaction is not sensitive to air or water. To exclude the role of air, the reaction operated under carefully degassed conditions provided nearly identical results (entry 12). Thus, this reaction system is redox neutral, which is distinct from the prior oxidative difunctionalization (vide supra, Scheme 1D).

Table 1.

Control experiments.

|

The reaction was run with 0.1 mmol 1a, 0.2 mmol 2a, 0.18 mmol 3a, Pd(OAc)2 (0.01 mmol), N1 (0.15 mmol), AsPh3 (0.025 mmol), AgOAc (0.3 mmol), and HOAc (0.5 mmol) in 0.5 mL TBME for 72 h. Yields were determined by 1H NMR analysis using dibromomethane as the internal standard.

The reaction was set up under N2.

The reaction time was 96 h. TBME, tert-butyl methyl ether; OAc, acetate; TFP, tri(2-furyl)phosphine; Cy, cyclohexyl; TIPS, triisopropylsilyl.

Substrate scope:

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, the scope with respect to aryl iodides was examined first (Table 2). Generally speaking, aryl iodides with an ortho electron-withdrawing group (EWG) were most efficient, which should benefit from their selective oxidative addition with the ANP.[22] A series of FGs, including ester (4a-4e), aryl halides (4c-4e), nitro (4f), ketone (4j), amide (4l) groups, were all well tolerated in this dual-electrophile-coupling reaction. Notably, a second iodide moiety (4e) not ortho to the EWG was compatible, which can serve as a handle for future derivatization. The reaction is not limited to the use of ortho-substituted aryl iodides; ortho-unsubstituted aryl iodides (4g-4i), including simple phenyl iodide (4h) and the one containing a methoxy group (4i), can still be employed as the first electrophile, albeit with diminished yield.

Table 2.

Substrates scope[a].

|

Unless otherwise noted all reactions were run with 0.2 mmol 1, 0.4 mmol 2, 0.36 mmol 3a and 0.3 mmol N1 in 1.0 mL TBME for 72 h. See Supporting Information for specific reaction conditions of each type of heteroarenes.

N10 was used instead of N1.

N6 and ethyl acetate was used instead of N1 and TBME.

Pd(acac)2, N3, and ethyl acetate were used instead of Pd(OAc)2, N1 and TBME. TBS, t-butyldimethylsilyl; Bn, benzyl.

Besides pyrroles, thiophenes and furans are also excellent substrates. A range of thiophenes with various substituents at the C2 position, including protected primary alcohols (5a-5c), methoxy (5d), halogens (5e and 5f), alkyl groups (5g and 5h) and substituted aryl moieties (5i and 5j), were all compatible in this transformation. In particular, both electron-rich (5d and 5i) and electron-deficient (5k) thiophenes can deliver the corresponding products in moderate to good yields. The C2 and C3 disubstituted thiophenes (5l-5o) also proved to be suitable substrates, giving fully substituted products that are nontrivial to be prepared via conventional approaches. Reactions with duloxetine (5v) and estrone (5w) derivatives worked smoothly to afford the desired difunctionalized products in good yields, indicating the potential synthetic utility of this method toward the late-stage functionalization of bioactive compounds. The pyrrole with a moderate EWG (5p) was also compatible. In addition, a series of furans with alkyl (5u) and aryl (5q-5t)[23] substituents at the C2 position were also competent substrates.

Regarding the scope of the second electrophile, besides the commonly used TIPS-substituted alkynyl bromide (3a), a number of bulky bromopropargyl silyl ethers were also reactive. Encouragingly, more complex alkyne coupling partners derived from camphor (6b) and β-cholestanol (6c) were also coupled at the pyrrole C5 position in moderate yields. Given the good substrate scope, it becomes evident that high complexity can be quickly introduced to the products through this three-component-coupling strategy.

Beyond using aryl iodides as the first electrophile, preliminary success on employing methyl iodide as the first electrophile was also achieved. When 2-chloro-1-methylpyrrole (1a) was subjected to the standard reaction conditions with 1.5 equiv of N2, the desired C4 methylated/C5-alkynylated pyrrole (8) was isolated in 34% yield (Eq. 1). Further optimization of the reaction is underway in our laboratory.

|

(1) |

Exploration of the reaction pathway:

To gain some mechanistic insights of this reaction, a number of control experiments were carried out (Scheme 3). First, in the absence of the second electrophile (3a), the C4-arylated product 9 was isolated in 64% yield under the standard conditions (with 50 mol% N1), suggesting that ipso protodepalladation can indeed occur when only aryl iodide 2a was used as the electrophile (Eq. 2). Using alkynyl bromide 3a alone as the electrophile, the direct mono-ipso-alkynylation product (4a’) was dominant even in the presence of NBE N1, along with minor multi-alkynylation products 10 (Eq. 3). For comparison, with both electrophiles 2a and 3a in the reaction, side-products 4a’ and 10 were only formed in very small amounts (Eq. 4). These results indicate that: (i) NBE must react faster with the Ar-Pd-X species than alkynyl bromide 3a; otherwise, direction ipso alkynylation would dominate in Eq. 4. (ii) NBE insertion with the metalated pyrrole (or the ANP formation) should be reversible under the reaction conditions; otherwise, ipso alkynylation product 4a’ cannot be the major product in Eq. 3. (iii) Unlike aryl iodide 2a, alkynyl bromide 3a favors ipso functionalization instead of reacting with the ANP, probably through Ar-Pd-X migratory insertion followed by β-bromide elimination based on the prior computational study.[14b]

Scheme 3.

Control experiments.

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Considering that ipso protonation can also occur under the reaction conditions (Eq. 2), one interesting question is whether the protodepalladation is faster than the coupling with the alkynyl bromide at the ipso position, especially when the reaction contains excess HOAc. If the ipso protonation is faster under the standard conditions, one could imagine that the C4-arylated product (9) should accumulate at the early stage of the reaction and gradually be converted to the difunctionalized product (4a). To explore this question, the kinetic profile of the model reaction was measured (see Figure S1, Supporting Information), which shows that the desired product 4a was formed rapidly at the beginning of the reaction and the concentration of side-product 9 was low throughout the whole reaction. The lack of buildup of intermediate 9 suggests that 9 is not the kinetic product and the Ar-Pd-X intermediate after the C4 arylation/NBE extrusion reacts faster with the alkynyl bromide than with the acid. In addition, the competition experiment between a simple thiophene substrate and the C4-arylated intermediate also indicated that the coupled difunctionalization pathway is more favorable (see Supporting Information).

Altogether, the control experiments and the kinetic profile of the reaction imply that the origin of the high selectivity of this dual electrophile coupling reaction is due to the unique reactivity of alkynyl bromides. First, they undergo slower migratory insertion than NBE, thus allowing smooth formation of the ANP intermediate. Second, alkynyl bromides react much slower with the ANP than aryl iodides do, thereby permitting selective arylation at the C4 position. Third, alkynyl bromides react faster with the Ar-Pd-X intermediate after NBE extrusion than protons and aryl iodides do; as such, the C5 protonation or arylation can be suppressed or minimized.

Synthetic utility:

The synthetic utility of this method was then explored. From the scalability prospect, it is encouraging that the reaction appears to be robust. On a gram scale, excellent yield can be obtained with an open-flask setup and untreated solvent (Eq. 5). In addition, reduction of the Pd loading to 1 mol% only slightly diminished the yield (Eq. 6).

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

Owing to the versatility of the alkyne moiety, the difunctionalized product can be readily converted to various other structural motifs (Scheme 4A). First, the silyl group on the alkyne can be easily removed under mild conditions with tetrabutylammonium fluoride (TBAF). The resulting terminal alkyne (11a) can then serve as a convenient handle to install other FGs to the heteroarene. For example, hydrogenation of the triple bond provided the alkyl moiety (11d), and hydration gave the ketone product (11e). In addition, the copper-catalyzed “click” reaction generated the biaryl linkage through the triazole formation (11b). Moreover, internal alkynes (11c) can be constructed by a Sonogashira coupling.

Scheme 4.

Product derivatizations. CuTC, copper(I)-thiophene-2-carboxylate.

On the other hand, starting from simple thiophene, two sequential double-electrophile couplings can be operated, resulting in a tetra-substituted thiophene (Scheme 4B). Compared to the previous route, our method does not rely on highly pre-functionalized thiophene,[24] and different substituents can be easily installed. Besides using thiophene, simple N-methylpyrrole (17) can undergo the direct tetra C−H-functionalization smoothly, affording fully substituted pyrrole 18 in 45% yield in one step (Scheme 4C). In addition, four different FGs can be easily installed in two steps by combining our previously developed oxidative difunctionalization method[2h] and this redox-neutral method (Scheme 4D). Interestingly, due to restricted rotation of the two aryl substituents, the products (14, 18 and 20) were isolated as a pair of diastereomers.

Taking advantage of the high site-selectivity and FG tolerance, the ortho arylation/ipso alkynylation of two thiophen substrates (21 and 1b) gave the Br- and I-substituted products, respectively (Scheme 5A). The Br-substituent was then converted to the corresponding pinacolboronate (22) via the Miyaura borylation, which further coupled with the I-substituted product (23) to give a rigid linear compound (24) in good yield. Product 24 could be regarded as an ETAr [4,4’-bis(2-ethynyl-3-thienyl)biphenyl] spacer that is a peptide-inspired and easily tunable spacer consisting of 4,4’-biphenyl axis and 3-thienyl moieties at both ends of the axis.[25] Comparing to the previous route, this approach is modular and provides more-substituted and unsymmetrical ETAr compounds. This three-component coupling reaction can also be employed in the synthesis of an inhibitor analogue for P38α mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK).[26] Besides the TIPS- and TBS-protected tertiary alcohol-derived alkynyl bromides, a new type of alkynyl bromide (29) with a tertiary alkyl substituent was found to be suitable for this double-electrophile coupling, resulting in the desired tetrasubstituted thiophene (30) in 71% yield (Scheme 5B).[27] The bromo moiety in 30 then underwent smooth Suzuki−Miyaura coupling with boronic acid 31. After deprotection of the silyl group, the P38α MAPK inhibitor analogue (32) was isolated in good overall yield.

Scheme 5.

Synthetic applications. pin, pinacolate.

Further extension:

Besides using alkynyl bromides as the second electrophile, preliminary success has also been obtained in realizing an ipso termination with a tethered carbonyl electrophile under the redox-neutral condition. Inspired by Lautens’[9a] and Zhou’s[9b] prior work, a trifluoromethyl acyl-substituted aryl iodide (2n) was found to be a suitable bifunctional electrophile (Table 3). Under slightly modified reaction conditions, the desired cyclization products were isolated in good yields without the need of reductants. Both pyrroles (34a-34d) and thiophene (34e) proved to be suitable heteroarene substrates. Note that the tricyclic products all contain a trisubstituted α-trifluoromethyl aryl alcohol moiety that could serve as useful building blocks in drug discovery.[28] Efforts on improving the scope and mechanistic understanding of this cyclization are ongoing in our labratory.

Table 3.

Annulation with the tethered electrophile [a].

|

Unless otherwise noted all reactions were run with 0.2 mmol 1, 0.3 mmol 2n and 0.2 mmol N1 in 1.0 mL TBME for 24 h.

0.3 mmol 1c and 0.2 mmol 2n were used.

0.2 mmol N6 and ethyl acetate (1.0 mL) were used.

Conclusion

In summary, a direct and site-selective vicinal difunctionalization of five-membered heteroarenes with two different electrophiles has been developed through the Pd/NBE cooperative catalysis. As the typical Catellani-type reactions involve coupling of one electrophile and one nucleophile, the transformation discovered here represents a new reaction mode. Capitalizing on the unique reactivity of alkynyl bromides, the three-component coupling reaction proceeds with complete regio- and site-selectivity. In addition, the reaction conditions are mild and robust with tolerance of air, moisture, and a broad scope of FGs. Thus, this method could be attractive for late-stage modification and modular synthesis of complex heteroarene-containing molecules. It is anticipated that the mechanistic insights gained in this study could provide useful implications for developing other Pd/NBE-catalyzed double-electrophile-coupling reactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Financial supports from the University of Chicago and NIGMS (1R01GM124414-01A1) are acknowledged. L.R. is supported by George Van Dyke Tiers Fellowship for Small Molecule Research. We thank Dr. Xin Liu and Mr. Shusuke Ochi for X-ray crystallography. Dr. Yun Zhou and Mr. Daniel Pyle are thanked for substrates preparation. Dr. Alexander Rago is thanked for checking the experimental procedure.

References

- [1].(a) Joule JA, Mills K, Heterocyclic Chemistry, Wiley: Weinheim, 2013; [Google Scholar]; (b) Taylor RD, MacCoss M, Lawson ADG, J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 5845–5859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].(a) Okazawa T, Satoh T, Miura M, Nomura M, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 5286–5287; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Goikhman R, Jacques TL, Sames D, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 3042–3048; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Yanagisawa S, Ueda K, Sekizawa H, Itami K, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14622–14623; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Joo JM, Touré BB, Sames D, J. Org. Chem. 2010, 75, 4911–4920; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Iaroshenko VO, Gevorgyan A, Davydova O, Villinger A, Langer P, J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 2906–2915; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Kim HT, Ha H, Kang G, Kim OS, Ryu H, Biswas AK, Lim SM, Baik M-H, Joo JM, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16262–16266; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Ghosh I, Khamrai J, Savateev A, Shlapakov N, Antonietti M, König B, Science 2019, 365, 360–366; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Li R, Zhou Y, Xu X, Dong G, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 18958–18963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].(a) Mkhalid IAI, Barnard JH, Marder TB, Murphy JM, Hartwig JF, Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 890–931; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lyons TW, Sanford MS, Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 1147–1169; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Toste FD, Sigman MS, Miller SJ, Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 609–615; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Rouquet G, Chatani N, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 11726–11743; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Huang Z, Dong G, Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 465–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Catellani M, Frignani F, Rangoni A, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1997, 36, 119–122. [Google Scholar]

- [5].(a) Catellani M, Top. Organomet. Chem. 2005, 14, 21–53; [Google Scholar]; (b) Catellani M, Motti E, Della Ca N’, Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1512–1522; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Martins A, Mariampillai B, Lautens M, Top. Curr. Chem. 2009, 292, 1–33; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Ye J, Lautens M, Nat. Chem. 2015, 7, 863; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Della Ca N’, Fontana M, Motti E, Catellani M, Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 1389–1400; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wegmann M, Henkel M, Bach T, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2018, 16, 5376–5385; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Liu Z-S, Gao Q, Cheng H-G, Zhou Q, Chem. Eur. J. 2018, 24, 15461–15476; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Zhao K, Ding L, Gu Z, Synlett 2019, 30, 129–140; [Google Scholar]; (i) Cheng H-G, Chen S, Chen R, Zhou Q, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5832–5844; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Wang J, Dong G, Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 7478–7528; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (k) Li R, Dong G, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 17859–17875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].(a) Jiao L, Bach T, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12990–12993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jiao L, Herdtweck E, Bach T, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 14563–14572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].(a) Wang X-C, Gong W, Fang L-Z, Zhu R-Y, Li S, Engle KM, Yu J-Q, Nature 2015, 519, 334–338; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dong Z, Wang J, Dong G, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 5887–5890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].(a) Li R, Liu F, Dong G, Chem 2019, 5, 929–939; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen S, Wang P, Cheng H-G, Yang C, Zhou Q, Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 8384–8389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].(a) Zhao Y-B, Mariampillai B, Candito DA, Laleu B, Li M, Lautens M, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 1849–1852; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) For an asymmetric version, see: Liu Z-S, Hua Y, Gao Q, Ma Y, Tang H, Shang Y, Cheng H-G, Zhou Q, Nat. Catal. 2020, 3, 727–733. [Google Scholar]

- [10].(a) Wang J, Qin C, Lumb J-P, Luan X, Chem 2020, 6, 2097–2109; [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang J, Wang H, Wang Z, Li L, Qin C, Luan X, Chin. J. Chem. 2021, 39, 2659–2667. [Google Scholar]

- [11].O’Duill ML, Engle KM, Synthesis 2018, 50, 4699–4714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rago AJ, Dong G, Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 3770–3774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].(a) Seregin IV, Ryabova V, Gevorgyan V, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 7742–7743; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dudnik AS, Gevorgyan V, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 2096–2098; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Dorel R, Echavarren AM, Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 9028–9072; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tan E, Quinonero O, Elena de Orbe M, Echavarren AM, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 2166–2172; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Tobisu M, Ano Y, Chatani N, Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 3250–3252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].(a) Tan E, Konovalov AI, Fernández GA, Dorel R, Echavarren AM, Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 5561–5564; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Usui K, Haines BE, Musaev DG, Sarpong R, ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4516–4527. [Google Scholar]

- [15].(a) Shen P-X, Wang X-C, Wang P, Zhu R-Y, Yu J-Q, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11574–11577; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Li R, Dong G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 1697–1701; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Liu L-Y, Qiao JX, Yeung K-S, Ewing WR, Yu J-Q, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 13831–13835; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Wang J, Dong Z, Yang C, Dong G, Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 1106–1112; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Li R, Zhou Y, Yoon K-Y, Dong Z, Dong G, Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3555; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Li R, Liu F, Dong G, Org. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 3108–3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wang J, Zhou Y, Xu X, Liu P, Dong G, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3050–3059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang J, Li R, Dong Z, Liu P, Dong G, Nat. Chem. 2018, 10, 866–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Dong Z, Wang J, Ren Z, Dong G, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 12664–12668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang P, Chen S, Zhou Z, Cheng H-G, Zhou Q, Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3323–3327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Porey S, Zhang X, Bhowmick S, Kumar Singh V, Guin S, Paton RS, Maiti D, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 3762–3774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Gorsline BJ, Wang L, Ren P, Carrow BP, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 9605–9614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Cárdenas DJ, Martín-Matute B, Echavarren AM, J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 5033–5040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].CCDC 2085271 (5q) contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre.

- [24].Saini KM, Saunthwal RK, Verma AK, Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017, 15, 10289–10298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Toyota K, Okada K, Katsuta H, Morita N, Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 145–151. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Vinh NB, Devine SM, Munoz L, Ryan RM, Wang BH, Krum H, Chalmers DK, Simpson JS, Scammells PJ, ChemistryOpen 2015, 4, 56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].The alkynyl bromide without the gem dimethyl groups was not suitable for this coupling under the current conditions likely due to the isomerization of the triple bond.

- [28].Mizuta S, Shibata N, Akiti S, Fujimoto H, Nakamura S, Toru T, Org. Lett. 2007, 9, 3707–3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.