Abstract

Objective:

Cerebral spatiotemporal dynamics of visual naming were investigated in epilepsy patients undergoing stereo-electroencephalography (SEEG) monitoring.

Methods:

Brain networks were defined by Parcel-Activation-Resection-Symptom matching (PARS) approach by matching high-gamma (50–150 Hz) modulations (HGM) in neuroanatomic parcels during visual naming, with neuropsychological outcomes after resection/ablation of those parcels. Brain parcels with >50% electrode contacts simultaneously showing significant HGM were aligned, to delineate spatiotemporal course of naming-related HGM.

Results:

In 41 epilepsy patients, neuroanatomic parcels showed sequential yet temporally overlapping HGM course during visual naming. From bilateral occipital lobes, HGM became increasingly left lateralized, coursing through limbic system. Bilateral superior temporal HGM was noted around response time, and right frontal HGM thereafter. Correlations between resected/ablated parcels, and post-surgical neuropsychological outcomes showed specific regional groupings.

Conclusions:

Convergence of data from spatiotemporal course of HGM during visual naming, and functional role of specific parcels inferred from neuropsychological deficits after resection/ablation of those parcels, support a model with six cognitive subcomponents of visual naming having overlapping temporal profiles.

Significance:

Cerebral substrates supporting visual naming are bilaterally distributed with relative hemispheric contribution dependent on cognitive demands at a specific time. PARS approach can be extended to study other cognitive and functional brain networks.

Keywords: Functional brain mapping, Brain networks, Intracranial electrodes, Epilepsy surgery, Cortical localization

(1). INTRODUCTION

Humans acquire verbal language by associating semantic concepts encoded in environmental objects with sequences of phonemes represented as words. This ability is tested by visual naming, which is commonly used for pre-surgical language mapping in patients with drug-resistant epilepsy (DRE) (Hamberger, 2015). However, the cerebral network dynamics supporting visual naming remains poorly characterized.

High-gamma modulation (HGM) during visual naming has been shown to be a specific and accurate biomarker for speech/language sites ascertained by electrical stimulation mapping (ESM) with both subdural electrodes and stereo-electroencephalography (SEEG) (Arya et al., 2017, Babajani-Feremi et al., 2016, Ervin et al., 2020, Ogawa et al., 2017, Sinai et al., 2005), and has been harnessed to study spatiotemporal dynamics of cortical activation to define functional networks. Different components of cortical language networks were activated with different temporal envelopes, having cascading spatial-temporal patterns, in a study including 7 patients (Wang et al., 2016). In another study, naming-associated HGM involved widespread neocortical networks with left hemisphere predominance (Nakai et al., 2019). HGM in left posterior temporal lobe medial to inferior temporal gyrus (ITG), and high-gamma suppression followed by augmentation in left prefrontal regions, were seen several hundred milliseconds before response onset (Nakai et al., 2019). Converging data from functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and HGM also revealed coincident activity in fusiform gyrus, intraparietal sulcus, and inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) preceding articulation (Forseth et al., 2018). These studies on spatiotemporal course of HGM, have led to empiric models of cerebral networks supporting visual naming (Arya et al., 2019a, Collard et al., 2016, Forseth et al., 2018). However, these models have not been validated with neurosurgical resections and deficits ascertained with post-operative neuropsychological evaluation (NPE), the functional significance of site(s) showing HGM being often inferred arbitrarily. Secondly, HGM recordings have been performed predominantly with subdural electrodes with limited or no access to deeper structures such as insula or cingulate gyri offered by SEEG, such that there is a dearth of information about their role in visual naming.

We have developed a novel approach for studying functional brain networks by matching the temporal profiles of HGM in neuroanatomic parcels, the extent to which these parcels were surgically resected/ablated, and post-operative neuropsychological outcomes. We have utilized this parcel-activation-resection-symptom matching (PARS) approach to study cerebral dynamics of visual naming in DRE patients who underwent neurosurgery after SEEG monitoring. We hypothesized that sequential HGM in neuroanatomic regions will reflect spatiotemporally separable cognitive subcomponents underlying visual naming, and that post-surgical NPE deficits will inform the subcomponent executed by the resected region.

(2). METHODS

(2.1). Patients and SEEG acquisition.

All DRE patients undergoing SEEG monitoring at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital able to participate in visual naming were eligible, unless malformation(s) or encephaloclastic lesion(s) distorted the neuroanatomy.

SEEG monitoring was performed with depth electrodes having 0.86mm diameter and 2.41mm contacts. SEEG signals were sampled at 2048 Hz with Natus Quantum amplifier using Neuroworks 8.5 software (Natus Neuro, Middleton WI). SEEG was recorded for study purposes using a referential montage, with the electrode contact farthest from the presumptive seizure-onset zone and not showing significant naming-related HGM was chosen as the reference. The study was approved by the institutional review board. Informed consent from patients ≥18 years-of-age and parental permission in others were obtained.

(2.2). Visual naming task.

Forty pictures were serially displayed on a monitor using E-Prime 3.0 (Psychology Software Tools, Sharpsburg PA), for 2–3s based on individual patient’s comfort, with 1s inter-stimulus interval. Patients were requested to name the picture aloud, immediately after the display. A trial run was performed to eliminate pictures that the patient was unable to name, and the order of pictures was randomized before recording. Patient’s audio output was collected with a microphone and routed through a digital trigger box to record the onset and termination of patient’s voice on a separate channel synchronized to the SEEG data. To ignore filler words (e.g. “umm”), outliers (response onsets with −2≥ z-score ≥2) were rejected. Average of the remaining response onsets was considered the patient’s mean response time.

(2.3). HGM analysis.

Clusters of high-gamma power change in time-frequency space were derived for each SEEG electrode contact using previously published methods (Ervin et al., 2020). Briefly, after rejection of artifactual channels, the remaining channels were notch filtered at 60 Hz intervals from 60–240 Hz (zero phase, finite impulse response, 13517 samples, 6.6s). SEEG data was subsequently band-pass filtered between 50–150 Hz (zero phase, finite impulse response, 6759 samples, 3.3s). The visual naming trial epochs were aligned such that t=0 coincides with picture display, and the analysis epoch included 1s baseline from the end of the previous trial (except the first trial).. Epochs without a patient response or with noise during intertrial periods were omitted, and the mean of baseline SEEG time-series was subtracted from each epoch.

Subsequently, time-frequency representations (TFRs) for 50–150 Hz frequencies with 1 Hz step were calculated using Morelet wavelets (cycles/wavelet = frequency/5, time decimation = 3x). After log-transformation of data, power modulations were calculated for each 1 Hz bin by normalizing trial epochs with respect to the inter-trial baseline. TFRs of these power modulations were subjected to a non-parametric permutation-based clustering using 2000 iterations, regular 2D lattice connectivity, time decimation factor of 8, frequency decimation factor of 2, resulting in 50×256 matrix for each channel (0.5 samples/Hz across 50–150 Hz, 85.3 samples/s x 3s) (Maris and Oostenveld, 2007). This required randomly resampling the intertrial baseline with replacement across time and epoch for each channel and each frequency bin. For each channel, HGM was assigned a p-value based on the distribution of the largest cluster across iterations being obtained from the baseline data. Signal processing was implemented in Python 3.8 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Analysis for high-gamma modulation.

(A) A single-channel example of notch- and bandpass-filtered SEEG data, with image display (red) and patient microphone (blue) inputs. (B) Epoched SEEG data from (A) aligned to image onset, preceded by 1000 ms intertrial baseline. Image display and patient microphone channels for a single response are also shown. (C) TFR using wavelet transform. Image onset at time=0, mean patient response time indicated by vertical line. (D) TFR of z-scores using the intertrial distribution within each frequency bin. (E) Clusters of high-gamma modulation in the time-frequency space. Values are equivalent to z-scores. (F) Time-axis linearly scaled to align mean response time to 1000 ms.

Abbreviations: TFR: time-frequency representation; SEEG: stereotactic electroencephalography.

(2.4). Image processing.

Pre-operative T1-Weighted MRI and post-operative computed tomographic (CT) scan were co-registered to the pre-operative fluid-attenuated inversion recovery MRI using 6-parameter rigid body transformation. MRI images were simultaneously nonlinearly warped into the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space using multi-channel segmentation. The same warping was then applied to the CT data already co-registered to the MRI, using SPM12 toolbox in MATLAB. Then, electrode contacts were identified and labeled from the normalized CT scan, and assigned to a parcel within the Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) 2012 atlas, using the FASCILE software (Ervin et al., 2021).

(2.5). Spatiotemporal course of HGM.

Time courses of HGMs were mapped onto fused brain images for each patient. A parcel-time matrix MA was created, where HGM in each parcel was represented as a time series. Each HGM cluster c had a corresponding parcel d, TFR r, and p-value p. TFR r was averaged across 50–150 Hz to obtain a time series , and p was passed through an exponential decay activation function, so that the clusters least likely to arise from the inter-trial distribution were valued near 1, and those most likely were valued near 0, to obtain . The sign of the time series multiplied by the decayed p-value was then added to the matrix MA. A second matrix MP kept track of the number of electrode contacts in each parcel. This process was repeated for each cluster across all contacts, to obtain an HGM “involvement” matrix MI = MA ⊘ Mp, where ⊘ represents elementwise division.

Because response times varied across patients, MA and MP matrices were scaled by the mean response times of individual patients. Essentially, time was linearly scaled such that the mean response time for each patient aligned to 1 second after picture display (Figure 1). Then, the combined involvement map across all patients, at a time step s was obtained by finding the sum of the activation matrices across n patients at times , , where for patient m having mean response time Tm. Similarly, an electrode contact activation density matrix was obtained from , so that . This combined temporal HGM involvement map contained all 136 parcels from the MICCAI atlas. However, we removed brain stem, ventricles, blood vessels, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and optic chiasm, because these were not sampled by SEEG. To ensure that HGM were well sampled, we also removed parcels with <3 electrode contacts, and white matter (WM), because MICCAI does not regionally subdivide WM. After obtaining a combined temporal HGM involvement map across all patients, assigning an order to HGM course required a threshold, such that parcels with electrode contacts showing significant HGM above that threshold will be considered “active”. This was arbitrarily set as 50%, so that parcels were sorted by the earliest incidence of ≥50% HGM involvement.

(2.6). Quantifying resection/ablation volumes.

To quantify resection volumes, post-operative MRI was co-registered to the pre-operative MRI, and a multi-channel segmentation was performed to classify each voxel in the fused image as gray matter (GM), WM, CSF, bone, or other tissue. Corresponding GM and WM voxels were combined, and a difference image between post- and pre-operative MRIs was obtained. In addition to true resection volume, this difference image was expected to contain some noise, which was mitigated by multi-step image opening procedure. The resulting image, providing an approximation of resection volume, was normalized to the MNI space using the aforementioned warping matrix, and intersected with the MICCAI atlas. Hence, the number of voxels in each parcels which were resected divided by the total number of voxels in the same parcel, provided the percentage of the parcel that was resected.

For laser ablations, the radii of the thermal damage zones (TDZs) were approximated. The software used with Visualase (Medtronic Inc. Minneapolis MN) outputs .gif files showing real-time thermography and permanent TDZs in two orientations. We isolated .gif frames when the laser was turned off. Ellipses were fit to these images, and major and minor axes were calculated. The radius of TDZ was conservatively estimated as mean of the minor axes across the orientations. A 3D image of TDZ was then constructed in the MNI space as a sphere of these radii for all laser activations for a given patient, intersected with MICCAI atlas, and the percentage of each parcel ablated was obtained.

(2.7). Neuropsychological Outcomes.

NPE was performed before and 1-year after surgery by a pediatric neuropsychologist (AWB). Following measures were analyzed: Verbal Comprehension, Perceptual Reasoning, Working Memory, and Processing Speed indices from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th/5th edition) or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (4th edition); Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 4th/5th edition (PPVT); Story Memory and Verbal Learning subtests from Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning II; Letter-Word Identification, Spelling, Calculation, and Passage Comprehension domains from Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement (3/4); Beery-Buktenika Test of Visuomotor Integration (6th edition); and Boston Naming Test (BNT). Full-scale intelligence quotient was not analyzed independently because it is derived from index scores. For BNT, z-scores were obtained from age-appropriate norms, while other measures provide standard scores with a mean of 100 and SD of 15 (Sakpichaisakul et al., 2020).

(2.8). Correlation Analysis.

A correlation matrix was computed between the proportion of resected/ablated parcels and NPE difference scores (post-operative – pre-operative). False discovery rate control with Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was used to control for multiple comparisons. Patients who did not have post-operative NPE/MRI or did not undergo surgery after SEEG monitoring could not be included in the resection-symptom matching.

To summarize, we mapped temporal course of HGM during visual naming to neuroanatomic parcels, computed the proportion of parcels that were resected/ablated, and ascribed them functional connotation based on correlation with post-surgical neuropsychological outcomes (PARS paradigm).

(3). RESULTS

Forty-one patients (14 females) were included, aged 3.9–21.2 years, implanted with 4–20 electrodes, having 93±113 electrode contacts/parcel (total 5530 electrode contacts, Figure 2) for parcel-activation matching. Respectively 16, 15, and 10 patients had left hemisphere, right hemisphere, and bilateral implants. Functional MRI showed left language dominance in 20 patients, and bilateral pattern in 3 patients (whose participation in functional MRI was limited). Eighteen patients did not undergo functional MRI but were right-handed and did not have left hemispheric malformation, therefore consistent with left lateralized language (Nakai et al., 2017). For resection-symptom matching, complete data including pre/post-operative MRIs and pre/post-operative NPE was available for only 11 patients (6 females), aged 4.8–20.8 years. Details are provided in Table 1.

Figure 2. Number of stereo electrode contacts in neuroanatomic parcels.

[Whole brain parcellation according to Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) atlas.]

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Clinical Information

| HGM course across neuroanatomic parcels | |

| Number of patients | 41 |

| Age (mean ± SD, range, in years) | 13.0 ± 4.4 (3.9, 21.2) |

| Sex (F, M) | 14, 27 |

| Number of SEEG electrodes per patient (mean ± SD, range) | 12 ± 3 (4, 20) |

| Number of electrode contacts per patient (mean ± SD, range) | 135 ± 44 (42, 253) |

| Implanted hemisphere (left, right, both) | 16, 15, 10 |

| Language Dominance (left, bilateral) | 38, 3 |

| Full scale intelligence quotient (mean ± SD) | 77.4 ± 19.4 |

| Correlation between resection/ablation and neuropsychological outcomes | |

| Number of patients | 11 |

| Age (mean ± SD, range, in years) | 13.1 ± 4.7 (4.8, 20.8) |

| Sex (F, M) | 6, 5 |

| Number of SEEG electrodes per patient (mean ± SD, range) | 10 ± 3 (5, 13) |

| Number of electrode contacts per patient (mean ± SD, range) | 104 ± 24 (62, 154) |

| Implanted hemisphere (left, right, both) | 7, 4, 0 |

| Language Dominance (left, atypical) | 11, 0 |

| Full scale intelligence quotient (mean ± SD) | 91.7 ± 17.0 |

| Surgical Procedures 1 | 4 (laser ablations), 7 (resections) |

| Brain MRI findings in all 41 patients | |

| Normal | 15 |

| Gliosis/encephalomalacia from prior insult/peri-natal injury | Left 4*, Right 5, Bilateral 5 |

| Hippocampal sclerosis | 2 (both left sided) |

| Cortical dysplasia | 2 (left temporal), 1 (left frontal), 1 (left parietal), 1 (right temporo-parietal) |

| Tuberous sclerosis | 2 |

| Malformations of cortical development | 1 (peri-ventricular heterotopia), 1 (right peri-Rolandic PMG), 1 (bilateral PMG) |

HGM: High-gamma modulation; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PMG: polymicrogyria; SD: standard deviation; SEEG: stereo-electroencephalography.

Laser ablations: right insula, right supramarginal gyrus, left hippocampus head and body, left amygdala and anterior hippocampus. Resections: right frontal; right parietal; right multilobar (including frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and insula); left anterior temporal lobectomy; left anterior temporal lobectomy with resection of adjacent basal inferior temporal gyrus; left posterior temporal; left inferior post-central gyrus.

1 patient had additional left hippocampal sclerosis.

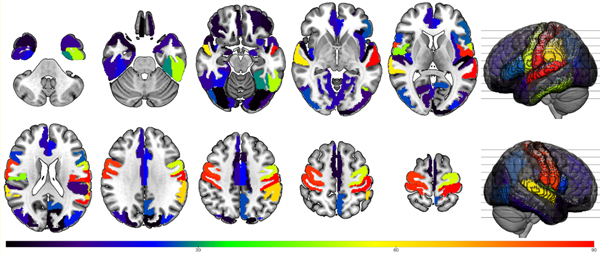

(3.1). Spatiotemporal course of HGM.

During visual naming, the neuroanatomic parcels showed sequential yet temporally overlapping HGM cascade (Figure 3, n=41). In first 100ms, predominant HGM was seen in bilateral occipital lobes. From 100–700ms, the HGM became increasingly left lateralized, with frontotemporal localization during 100–500ms, and temporo-insular localization during 500–700ms. HGM involved many of the limbic structures from 100–800ms in temporal, frontal, insular, and opercular cortices. From 700–900ms, a left>right frontotemporal HGM was seen, most prominently in left IFG pars opercularis and triangularis (canonical Broca’s area). Around the response time (1±0.1s), left>right temporal HGM was seen, prominently including bilateral superior temporal gyri (STG). After 1.1s, HGM was mostly limited to right frontal lobe.

Figure 3. Spatiotemporal course of high-gamma modulation during visual naming (Parcel Activation Matching).

Statistically significant increase (red) or decrease (blue) in 50–150 Hz power during visual naming is shown in different neuroanatomic parcels (y-axis) at every 100 ms (x-axis). Time was linearly scaled such that mean response time for each patient aligns at 1000 ms.

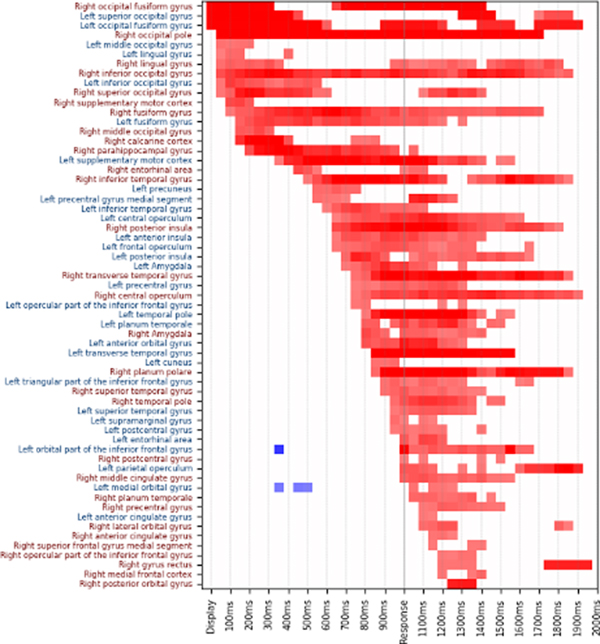

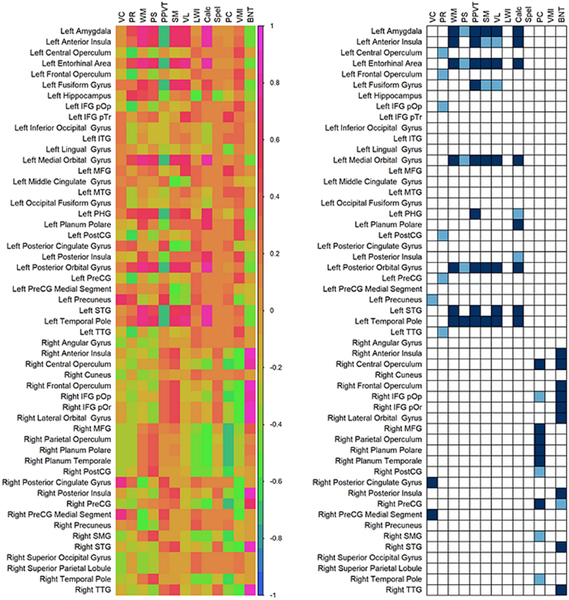

(3.2). Resections and NPE.

Significant correlations between NPE difference scores and volumes of resected/ablated parcels showed lateralization-based groupings (Figure 4, n=11). Resections of left-hemispheric parcels mostly in the limbic system, including amygdala, para-hippocampal gyrus, entorhinal cortex, temporal pole, orbitofrontal cortex, and anterior insula were associated with changes in working memory, PPVT, story memory, verbal learning, processing speed, and calculation indices. Deficits in working memory, PPVT, verbal learning, and calculation were also seen with resections including left STG, while those including left fusiform gyrus showed a decline in PPVT. Significant decrease in BNT was seen with resections including right insular-opercular cortices, transverse temporal gyrus (TTG), STG, orbitofrontal cortex, and IFG, whereas deficits in passage comprehension were seen with resections including right opercular cortices, temporal plane, middle frontal gyrus (MFG), and precentral gyrus. Resections of right posterior cingulate and medial segment of precentral gyri were associated with a decrease in verbal comprehension.

Figure 4. Correlation between the proportions of parcels resected and neuropsychological outcomes (Resection Symptom Matching).

Left panel shows Pearson correlation coefficient between the proportions of the parcel volumes that were resected/ablated and the neuropsychological difference scores (post-operative – pre-operative). Right panel shows the p-values for these correlation coefficients after false discovery rate correction (deep blue: pcorrected<0.05, sky blue: 0.05<pcorrected<0.1).

Abbreviations: VC: Verbal Comprehension; PR: Perceptual Reasoning; WM: Working Memory; PS: Processing Speed (these 4 are subtests of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children 4th/5th edition, or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale 4th edition); PPVT: Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test 4th/5th edition; SM: Story Memory; VL: Verbal Learning (these 2 are subtests from Wide Range Assessment of Memory and Learning II); LWI: Letter-Word Identification; Calc: Calculation; Spel: Spelling; PC: Passage Comprehension (these 4 domains are from Woodcock-Johnson Tests of Achievement 3rd/4th edition); VMI: Visuomotor Integration (Beery-Buktenika Test 6th edition); BNT: Boston Naming Test; IFG: Inferior Frontal Gyrus; ITG: Inferior Temporal Gyrus; MFG: Middle Frontal Gyrus; MTG: Middle Temporal Gyrus; PHG: Para-hippocampal Gyrus; pOp: pars opercularis; PostCG: Postcentral Gyrus; PreCG: Precentral Gyrus; pTr: pars triangularis; SMG: Supramarginal Gyrus; STG: Superior Temporal Gyrus; TTG: Transverse Temporal Gyrus.

(4). DISCUSSION

(4.1). Model for Visual Naming.

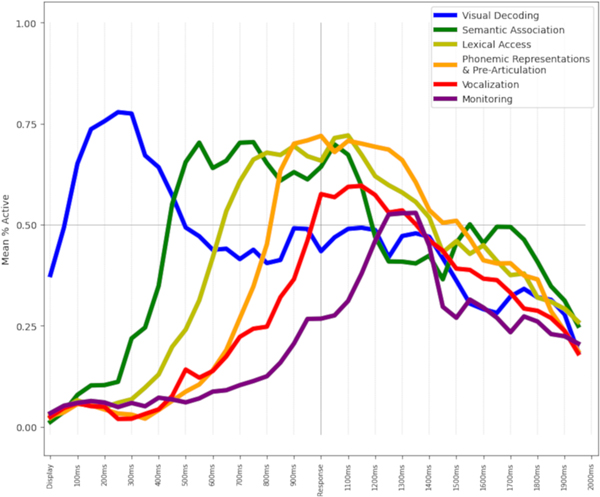

Spatiotemporal course of HGM and correlations between resection/ablation volumes and neuropsychological outcomes (PARS approach) allow us to obtain a model for cerebral dynamics during visual naming (Video). We postulate that the cortical activation dynamics during visual naming can be divided into six phases, representing a continuum with overlapping temporal boundaries (Figure 5, n=41).

Figure 5. Time-courses of high-gamma modulation during proposed cognitive phases of visual naming.

Y-axis represents the mean percentage of electrode contacts showing statistically significant high-gamma modulation across all neuroanatomic parcels included in a cognitive phase. Sequential yet overlapping temporal pattern is evident with visual decoding parcels peaking earlier, while those involved in semantic, lexical, and phonemic aspects enduring till after the response. Time (x-axis) was scaled such that mean response time for each patient was aligned at 1000 ms.

(4.1.1). Visual Decoding.

During first 100–150ms after picture display, bilateral occipital HGM was seen, starting from fusiform gyri and propagating dorsolaterally and anteriorly. This probably represents extraction of visual information from pictorial display and early contextual interpretation. Although these areas were mostly spared during surgery, left fusiform gyrus resections were associated with deficits in PPVT, story memory, and verbal learning. Visual sensations of shapes, color, flashing/shimmering, or distortions in visual perception have been reported with electrical stimulation of bilateral fusiform, inferior occipital, middle occipital, left lingual, and right para-hippocampal gyri, right calcarine cortex, and left occipital pole, which showed HGM during this period (Allison et al., 1993, Lee et al., 2000, Penfield and Perot, 1963). Interference with picture naming, reading comprehension, and token test have been also described with left fusiform stimulation, with global aphasia, alexia, and agraphia seen on stimulation of left anterior fusiform gyrus (visual word form area) which is continuous with basal language area (Luders et al., 1986). An important extra-occipital HGM during first 100ms involved right supplementary sensorimotor area (SSMA), whose stimulation can produce ideational manifestations (Fried et al., 1991). Also, recall of past visual experiences have been described with right para-hippocampal stimulation (Penfield and Perot, 1963). Functional MRI studies suggest that regions involved in visual processing of objects may also support extraction of the semantic content encoded by the names of those objects (Skipper and Small, 2006). Therefore, HGM in these two structures probably represents transition to the next phase.

(4.1.2). Semantic Association.

From 100–600ms after picture display, HGM involved bilateral frontotemporal parcels including the limbic system, similar to that reported by Nakai et al., 2019. HGM in left SSMA occurred approximately 100ms after right SSMA, followed by right entorhinal area, right ITG, and left precuneus. While these parcels were mostly spared from surgery, resections including left precuneus were associated with decline in verbal comprehension. Electrical stimulations of these structures are associated with visual phenomena linked to cognitive and linguistic manifestations, suggesting semantic mapping of the visual information. Stimulation of right entorhinal cortex and right ITG are associated with visual sensations related to past memories, sensation of familiarity, and impairments in visual naming and auditory comprehension (Barbeau et al., 2005, Bhatnagar et al., 2000, Mahl et al., 1964). Stimulations in left precuneus, medial segment of left precentral gyrus, and left ITG are associated with a feeling of being cognitively occupied, depersonalization, being “emotional”, along with naming errors and distortions of visual perception (Allison et al., 1993, Kahane et al., 2003, Penfield and Perot, 1963, Schwartz et al., 1999). Temporal lobe parcels activated in this phase belong to the ventral pathway of auditory processing, known to support semantic verbal memory and retrieval (Chang et al., 2015, Skipper and Small, 2006).

(4.1.3). Lexical Access.

During 500–800ms, HGM is predominantly left lateralized and involves temporal and opercular-insular structures. After left ITG, HGM propagates to left inferior peri-Rolandic (opercular) cortex, anterior followed by posterior insula, amygdala, and precentral gyrus. Right-sided HGM is seen only in posterior insula (≈625ms) and TTG (≈700ms). We think this represents access to internal lexicon after having extracted semantic information, and begins to map lexical representations onto phonemic sequences. Surgical resections including these parcels resulted in higher-order cognitive deficits supporting visual-linguistic function. Resections including left amygdala and left insula were associated with deficits in working memory, processing speed, PPVT, story memory, verbal learning, and calculation, while those including left opercular cortex or encroaching on left precentral gyrus were associated with deficits in perceptual reasoning. Resections including right posterior insula and right TTG were associated with a decline in BNT. Electrical stimulation of left amygdala has been associated with vivid and complex visual or multisensory hallucinations related to emotionally significant past experience(s), and direct interference with verbal memory recall (Fish et al., 1993, Selimbeyoglu and Parvizi, 2010). Also, auditory manifestations, dysarthria, and modulation of voice intensity have been described with electrical stimulation of both insular cortices (Afif et al., 2010, Mazzola et al., 2019). This, together with HGM in right TTG which is involved in auditory and audiovisual processing, suggests beginning search for phonemic sequences, while HGM in left inferior peri-Rolandic cortex and precentral gyrus represents early motor planning (Kombos and Suss, 2009, Suzuki et al., 2018, Woods et al., 2009).

(4.1.4). Phonemic Representations and Pre-articulation.

Between 700–900ms, prominent HGM occurs in left IFG pars opercularis (transient) and triangularis (sustained), constituting the canonical Broca’s area. Also seen is HGM involving superior surface of left temporal lobe from TTG up to temporal pole, left orbitofrontal cortex, left cuneus, right amygdala, right inferior peri-Rolandic cortex, and right temporal pole. In this phase, HGM involves some right-hemispheric homologs of left-sided parcels activated during the lexical phase, however, HGM involving the Broca’s area is distinctive. Resections encroaching left IFG pars opercularis, and including left TTG were associated with deficits in perceptual reasoning. Whereas, left temporal polar resections were associated with decline in working memory, processing speed, PPVT, story memory, verbal learning, and calculation; and those including right opercular cortex and planum polare were associated with deficits in passage comprehension and BNT. Electrical stimulation of left IFG (pars opercularis and triangularis) is associated with multiple linguistic phenomena attesting to its preeminent role in pre-articulatory processing, including impaired recitation, errors of naming and syntax, speech arrest, anomia, and sometimes comprehension deficits (Bhatnagar et al., 2000, Lesser et al., 1984, Schaffler et al., 1993). Also, stimulation of temporal poles, particularly left temporo-polar cortex, is associated with visual and auditory hallucinations (human voices), and impaired recall of word representations (Hamberger et al., 2001, Penfield and Perot, 1963, Selimbeyoglu and Parvizi, 2010). Structures activated during this phase represent the dorsal pathway of auditory processing, involved in mapping sound to motor-based representations (Skipper and Small, 2006). Functional MRI studies have shown that speech perception overlaps the production of similar sounds in these regions (Skipper and Small, 2006). Particularly, Broca’s area is now regarded as a pre-articulatory region based on activation of IFG pars opercularis by tasks requiring access to verbal working memory for maintenance of phonological information, and activation of IFG pars triangularis by semantic and syntactic tasks (Burton et al., 2000, Wise et al., 1999). Hence, we think that this phase maps the lexical representations onto specific phonemic sequences and their motor plans in preparation for verbal response.

(4.1.5). Vocalization.

Around ±100ms of verbal response, significant HGM was seen in left>right temporal and adjacent parietal lobes, involving bilateral STG, bilateral postcentral gyri, left SMG, left entorhinal area and right planum temporale including temporal pole. Bilateral STG are known to participate in converging visual and auditory inputs into the language network for response execution. Stimulations of right STG have been associated with speech arrest during visual naming, visual and auditory sensations linked to experiential memory, and change in pitch of the voice (Andy and Bhatnagar, 1984, Penfield and Perot, 1963), while left STG stimulations have been associated with alexia, errors in naming and syntax, phonemic paraphasia, conduction aphasia, phoneme identification and comprehension errors, and audiovisual hallucinations related to past experiences (Arya et al., 2019b, Bhatnagar et al., 2000, Boatman et al., 1995, Penfield and Perot, 1963). Interference with visual naming including speech arrests are also seen with stimulations in left SMG and post-central gyri (Duffau et al., 2002, Selimbeyoglu and Parvizi, 2010). Resections including left STG were associated with decrease in working memory, PPVT, verbal learning, and calculation, while those involving right STG were associated with decline in BNT. Resections in left postcentral gyrus were associated with deficits in processing speed, while those in right postcentral gyrus and temporal pole were associated with deficits in passage comprehension. We believe that these deficits represent the convergence of distributed cognitive processes that occur at the time of verbal response. Many of the structures activated in this phase belong to temporo-parietal arm of the dorsal auditory pathway, and have specific role in integration of multisensory inputs with speech motor representations (Skipper and Small, 2006). Because bilateral STG showed HGM exclusively around the vocalization (Figures 3,5), we speculate that STG may participate in transference of converged multisensory inputs to motor programs, perhaps acting as a “switch” for vocalization (Nakai et al., 2019). Notably, HGM in canonical language motor areas including left precentral gyrus occurred earlier than the observed vocalization.

(4.1.6). Monitoring.

After 1s, relatively poorly sustained HGM were seen predominantly in right frontal lobe, including cingulate gyrus, precentral gyrus, orbitofrontal cortex, medial surface, and IFG pars opercularis. In addition, right lingual gyrus and left cingulate gyrus HGM were also seen. Resections including these areas, particularly right posterior cingulate and medial precentral gyri were associated with deficits in verbal comprehension. Whereas, stimulations of cingulate gyri, particularly right cingulate gyrus are associated with monitoring of the visual field for target object(s) (Richer et al., 1993, Selimbeyoglu and Parvizi, 2010). Anatomic studies in non-human primates have shown that occipitofrontal pathways connecting visual association areas to frontal lobe serve the visuospatial component of the so-called diffuse attention system (Colby, 1991). Additionally, functional MRI studies with attention tasks have shown preeminent role of cingulate gyri in target monitoring and conflict resolution subsystems, with right lateralization of the spatial attention subsystem (Filley, 2002, Raz, 2004). Therefore, this phase involves verifying the verbal response against the visual stimulus and internal lexicon.

(4.2). Neurophysiologic Implications.

Our observations suggest that cortical dynamics of visual naming are bilaterally distributed with differential lateralization during different phases (Figure 3). HGM is bilateral during the visual phase, becomes progressively left lateralized until the lexical and phonemic phases, and finally becomes right lateralized during post-verbal monitoring. Hence, the traditional concept of a static language lateralization may be rather simplistic, because the relative hemispheric contributions vary depending on the cognitive demands of a specific phase. We also showed that visual perception, cognitive processing, and speech production are not strictly functionally separable in terms of their neuroanatomic substrates, and instead lie on a continuum. This suggests an overlap among cerebral regions supporting higher-level (semantic and lexical) and lower-level (speech sounds) processes, suggesting that cerebral encoding of language is unlikely to be distinctive for visual, semantic, phonemic, syntactic, or pragmatic processes (Hickok and Poeppel, 2007, Skipper and Small, 2006). Spatiotemporal course of HGM does not imply propagation through recognized WM tracts, our study offers a temporal sequence of HGM across neuroanatomic parcels during visual naming, but not the underlying mechanism. Also, HGM course is likely task-dependent, and hence, relative contributions of the two cerebral hemispheres will depend on the task used to evaluate language function. Our PARS approach can be easily extended to other cognitive or sensorimotor functions, although the computational analysis will depend on the design features of the specific task.

Convergence of data from HGM course, post-operative neuropsychological outcomes, and previous ESM and functional MRI studies suggests that same cerebral regions support both linguistic and non-linguistic processes. Hence, it is likely that language evolved in humans from existing cerebral processing mechanisms, integrated with other cognitive networks, and not as a dedicated process as envisaged by classical hierarchical/modular concept of brain-language relationships (Chang et al., 2015, Skeide and Friederici, 2016, Skipper and Small, 2006).

(4.3). Clinical Implications.

Our study reaffirms that language network is exceedingly complex and performing ESM with a single task, is insufficient to prevent post-operative neuropsychological deficits, particularly in higher cognitive constructs beyond mere naming ability. A recent study including 89 patients aged 6–24 years, found that language ESM with subdural electrodes using a visual naming task was associated with improvement in post-operative cognitive performance (Sakpichaisakul et al., 2020). However, when ESM was deemed clinically unnecessary, particularly in patients with right hemispheric seizure-onset zone, a significant decline in NPE scores was noted, particularly in memory (Sakpichaisakul et al., 2020). The present study also showed decline in BNT predominantly with resection of right hemispheric parcels, probably due to the practice of diligently preserving ESM naming sites in the left hemisphere. Another study including 17 patients, showed that resection of subdural electrodes showing significant visual naming-associated HGM, but no ESM speech/language interference, was associated with a post-operative deficit in verbal working memory (Arya et al., 2019c). Our study extends these observations, that post-operative neuropsychological deficits associated with resection of HGM+ electrodes are driven by spatiotemporal position of resected parcels in the context of HGM propagation during a particular language task. Therefore, it is desirable to perform presurgical language mapping using multiple tasks, which is more feasible with HGM that allows simultaneous recording of all electrodes versus prolonged pairwise ESM (Wellmer et al., 2009). In near future, it may be possible to derive a predictive model based on HGM during multiple language tasks, and proposed cerebral resection, to counsel families/patients regarding potential neuropsychological deficits.

(4.4). Limitations.

Our study included fewer patients for correlating resection/ablation volumes and NPE scores, because many patients did not undergo post-operative MRI/NPE due to lack of clinical need or loss to follow-up. Hence, the resection-symptom matching part of our study should be regarded as preliminary.

The mapping from time-course of HGMs in different parcels and their functional role in visual naming based on NPE is not one-to-one, because many parcels were never resected. In addition to correlation between resections/ablations and NPE outcomes, we discussed functional role of brain parcels based on ESM and functional MRI findings from published literature. Although we performed ESM in many of patients included here, we did not have the diversity of language responses to make inferences about specific functions. This is because different components of ESM-induced speech arrest, including aphasic, sensorimotor, or amnestic contributions, often cannot be parsed in children. Like any other study of pediatric epilepsy, we had heterogeneous ages and phenotypes in our study. However, HGM analysis has been well-validated across this age-range (Arya et al., 2017, Nakai et al., 2019, Sinai et al., 2005), and NPE scores are age-standardized, supporting group-level analysis. Finally, our study based on DRE patients may not be fully applicable to neurologically healthy children, however, to improve generalizability we excluded patients with extensive lesions altering the neuroanatomic landmarks and atypical language dominance.

(5). Conclusions and Outlook.

Our study develops a data-driven model with high-spatiotemporal resolution for cerebral dynamics underlying visual naming, using reproducible whole-brain parcellation (Forseth et al., 2018, Nakai et al., 2019, Wang et al., 2016). We also scaled the temporal course of HGM such that each patient’s mean response time aligned at 1s. We derived functional significance of neuroanatomic parcels activated during a time interval from correlations between resected/ablated volumes of parcels, and resultant neuropsychological outcomes. Our study highlights that the neuroanatomic substrates supporting visual naming are bilaterally distributed with time-specific lateralization and localization indicative of cognitive subcomponents involved during that interval. Hence, cognitive networks underlying linguistic functions likely have task-specific organization which may be exceedingly complex. Therefore, presurgical language mapping should be performed with multiple tasks and task-related HGMs should be interpreted in the context of planned neurosurgical resection. The PARS paradigm used here to elucidate cerebral dynamics of visual naming, can be easily extended to other language or cognitive tasks to expand our understanding of functional neuroanatomy.

Supplementary Material

Video showing sequential activation of parcels, where at least 50% of the electrode contacts across all patients showed statistically significant high-gamma modulation, every 50 ms starting from picture display during the visual naming task. Time is linearly scaled such that the mean response time for each patient aligns to 1 second after picture display.

HIGHLIGHTS.

During visual naming, high-gamma modulation occurs in a posteroanterior sequential pattern with overlapping temporal profiles.

Cortical activations during visual naming represent cognitive sub-components with different relative contributions from the left and right cerebral hemispheres.

Post-surgical neuropsychological deficits correlated with the location of resected parcels within the visual naming network.

Funding

Research presented in this manuscript was funded by NIH (NINDS) R01 NS115929, Procter Foundation (Procter Scholar Award), and the Division of Neurology at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Funding sources had no role in study design, conduct of the study, writing the manuscript, and the decision to submit for publication.

Disclosures

All commercial software used in this research were covered under appropriate end-user licenses. Python 3.x (Anaconda distribution) and R (version 4.x) are open-source programming languages. The methodology of using nonparametric clustering of high-gamma activations for functional brain mapping with intracranial EEG is patent pending. RA receives research support from NIH (NINDS) R01 NS115929 and Procter Foundation. None of the other authors have any relevant disclosures.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Afif A, Minotti L, Kahane P, Hoffmann D. Middle short gyrus of the insula implicated in speech production: intracerebral electric stimulation of patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia 2010;51(2):206–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allison T, Begleiter A, McCarthy G, Roessler E, Nobre AC, Spencer DD. Electrophysiological studies of color processing in human visual cortex. EEG Clin Neurophysiol 1993;88(5):343–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andy OJ, Bhatnagar SC. Right-hemispheric language evidence from cortical stimulation. Brain Lang 1984;23(1):159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya R, Babajani-Feremi A, Byars AW, Vannest J, Greiner HM, Wheless JW, et al. A model for visual naming based on spatiotemporal dynamics of ECoG high-gamma modulation. Epilepsy Behav 2019a;99:106455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya R, Ervin B, Dudley J, Buroker J, Rozhkov L, Scholle C, et al. Electrical stimulation mapping of language with stereo-EEG. Epilepsy Behav 2019b;99:106395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya R, Roth C, Leach JL, Middeler D, Wilson JA, Vannest J, et al. Neuropsychological outcomes after resection of cortical sites with visual naming associated electrocorticographic high-gamma modulation. Epilepsy Res 2019c;151:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arya R, Wilson JA, Fujiwara H, Rozhkov L, Leach JL, Byars AW, et al. Presurgical language localization with visual naming associated ECoG high- gamma modulation in pediatric drug-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsia 2017;58(4):663–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babajani-Feremi A, Narayana S, Rezaie R, Choudhri AF, Fulton SP, Boop FA, et al. Language mapping using high gamma electrocorticography, fMRI, and TMS versus electrocortical stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol 2016;127(3):1822–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbeau E, Wendling F, Regis J, Duncan R, Poncet M, Chauvel P, et al. Recollection of vivid memories after perirhinal region stimulations: synchronization in the theta range of spatially distributed brain areas. Neuropsychologia 2005;43(9):1329–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar SC, Mandybur GT, Buckingham HW, Andy OJ. Language representation in the human brain: evidence from cortical mapping. Brain Lang 2000;74(2):238–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boatman D, Lesser RP, Gordon B. Auditory speech processing in the left temporal lobe: an electrical interference study. Brain Lang 1995;51(2):269–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton MW, Small SL, Blumstein SE. The role of segmentation in phonological processing: an fMRI investigation. J Cogn Neurosci 2000;12(4):679–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang EF, Raygor KP, Berger MS. Contemporary model of language organization: an overview for neurosurgeons. J Neurosurg 2015;122(2):250–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colby CL. The neuroanatomy and neurophysiology of attention. J Child Neurol 1991;6 Suppl:S90–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collard MJ, Fifer MS, Benz HL, McMullen DP, Wang Y, Milsap GW, et al. Cortical subnetwork dynamics during human language tasks. NeuroImage 2016;135:261–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffau H, Capelle L, Sichez N, Denvil D, Lopes M, Sichez JP, et al. Intraoperative mapping of the subcortical language pathways using direct stimulations. An anatomo-functional study. Brain 2002;125(Pt 1):199–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervin B, Buroker J, Rozhkov L, Holloway T, Horn PS, Scholle C, et al. High-gamma modulation language mapping with stereo-EEG: A novel analytic approach and diagnostic validation. Clin Neurophysiol 2020;131(12):2851–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ervin B, Rozhkov L, Buroker J, Leach JL, Mangano FT, Greiner HM, et al. Fast Automated Stereo-EEG Electrode Contact Identification and Labeling Ensemble. Stereotac Func Neurosurg 2021:1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filley CM. The neuroanatomy of attention. Semin Speech Lang 2002;23(2):89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish DR, Gloor P, Quesney FL, Olivier A. Clinical responses to electrical brain stimulation of the temporal and frontal lobes in patients with epilepsy. Pathophysiological implications. Brain 1993;116 (Pt 2):397–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forseth KJ, Kadipasaoglu CM, Conner CR, Hickok G, Knight RT, Tandon N. A lexical semantic hub for heteromodal naming in middle fusiform gyrus. Brain 2018;141(7):2112–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried I, Katz A, McCarthy G, Sass KJ, Williamson P, Spencer SS, et al. Functional organization of human supplementary motor cortex studied by electrical stimulation. J Neurosci 1991;11(11):3656–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger MJ. Object naming in epilepsy and epilepsy surgery. Epilepsy Behav 2015;46:27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamberger MJ, Goodman RR, Perrine K, Tamny T. Anatomic dissociation of auditory and visual naming in the lateral temporal cortex. Neurology 2001;56(1):56–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickok G, Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat Rev Neurosci 2007;8(5):393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahane P, Hoffmann D, Minotti L, Berthoz A. Reappraisal of the human vestibular cortex by cortical electrical stimulation study. Ann Neurol 2003;54(5):615–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kombos T, Suss O. Neurophysiological basis of direct cortical stimulation and applied neuroanatomy of the motor cortex: a review. Neurosurg Focus 2009;27(4):E3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HW, Hong SB, Seo DW, Tae WS, Hong SC. Mapping of functional organization in human visual cortex: electrical cortical stimulation. Neurology 2000;54(4):849–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser RP, Lueders H, Dinner DS, Hahn J, Cohen L. The location of speech and writing functions in the frontal language area. Results of extraoperative cortical stimulation. Brain 1984;107 ( Pt 1):275–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luders H, Lesser RP, Hahn J, Dinner DS, Morris H, Resor S, et al. Basal temporal language area demonstrated by electrical stimulation. Neurology 1986;36(4):505–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahl GF, Rothenberg A, Delgado JM, Hamlin H. Psychological Responses in the Human to Intracerebral Electrical Stimulation. Psychosom Med 1964;26:337–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maris E, Oostenveld R. Nonparametric statistical testing of EEG- and MEG-data. J Neurosci Methods 2007;164(1):177–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzola L, Mauguiere F, Isnard J. Functional mapping of the human insula: Data from electrical stimulations. Rev Neurol 2019;175(3):150–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai Y, Jeong JW, Brown EC, Rothermel R, Kojima K, Kambara T, et al. Three- and four-dimensional mapping of speech and language in patients with epilepsy. Brain 2017;140(5):1351–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakai Y, Sugiura A, Brown EC, Sonoda M, Jeong JW, Rothermel R, et al. Four-dimensional functional cortical maps of visual and auditory language: Intracranial recording. Epilepsia 2019;60(2):255–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa H, Kamada K, Kapeller C, Prueckl R, Takeuchi F, Hiroshima S, et al. Clinical Impact and Implication of Real-Time Oscillation Analysis for Language Mapping. World Neurosurg 2017;97:123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penfield W, Perot P. The Brain’s Record of Auditory and Visual Experience. A Final Summary and Discussion. Brain 1963;86:595–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raz A Anatomy of attentional networks. Anat Rec B New Anat 2004;281(1):21–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richer F, Martinez M, Robert M, Bouvier G, Saint-Hilaire JM. Stimulation of human somatosensory cortex: tactile and body displacement perceptions in medial regions. Exp Brain Res 1993;93(1):173–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakpichaisakul K, Byars AW, Horn PS, Aungaroon G, Greiner HM, Mangano FT, et al. Neuropsychological outcomes after pediatric epilepsy surgery: Role of electrical stimulation language mapping. Seizure 2020;80:183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffler L, Luders HO, Dinner DS, Lesser RP, Chelune GJ. Comprehension deficits elicited by electrical stimulation of Broca’s area. Brain 1993;116 ( Pt 3):695–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz TH, Devinsky O, Doyle W, Perrine K. Function-specific high-probability “nodes” identified in posterior language cortex. Epilepsia 1999;40(5):575–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selimbeyoglu A, Parvizi J. Electrical stimulation of the human brain: perceptual and behavioral phenomena reported in the old and new literature. Front Hum Neurosci 2010;4:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinai A, Bowers CW, Crainiceanu CM, Boatman D, Gordon B, Lesser RP, et al. Electrocorticographic high gamma activity versus electrical cortical stimulation mapping of naming. Brain 2005;128(Pt 7):1556–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skeide MA, Friederici AD. The ontogeny of the cortical language network. Nat Rev Neurosci 2016;17(5):323–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skipper JI, Small SL. fMRI studies of language. Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics: Elsevier Ltd; 2006. p. 496–511. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Enatsu R, Kanno A, Ochi S, Mikuni N. The auditory cortex network in the posterior superior temporal area. Clin Neurophysiol 2018;129(10):2132–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Fifer MS, Flinker A, Korzeniewska A, Cervenka MC, Anderson WS, et al. Spatial-temporal functional mapping of language at the bedside with electrocorticography. Neurology 2016;86(13):1181–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wellmer J, Weber C, Mende M, von der Groeben F, Urbach H, Clusmann H, et al. Multitask electrical stimulation for cortical language mapping: hints for necessity and economic mode of application. Epilepsia 2009;50(10):2267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RJ, Greene J, Buchel C, Scott SK. Brain regions involved in articulation. Lancet 1999;353(9158):1057–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods DL, Stecker GC, Rinne T, Herron TJ, Cate AD, Yund EW, et al. Functional maps of human auditory cortex: effects of acoustic features and attention. PloS One 2009;4(4):e5183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video showing sequential activation of parcels, where at least 50% of the electrode contacts across all patients showed statistically significant high-gamma modulation, every 50 ms starting from picture display during the visual naming task. Time is linearly scaled such that the mean response time for each patient aligns to 1 second after picture display.