Abstract

Introduction

Modified risk tobacco product (MRTP) claims for heated tobacco products (HTPs) that convey reduced exposure compared with conventional cigarettes may promote product initiation and transition among young people. We assessed the effects of a hypothetical MRTP claim for HTPs on young adults’ intention and perceptions of using HTPs and whether these effects differed by their current cigarette and e-cigarette use.

Methods

We embedded a randomised between- subjects experiment into a web-based survey administered among a cohort of 2354 Southern California young adults (aged 20–23) in 2020. Participants viewed depictions of HTPs with an MRTP claim (n=1190) or no claim (n=1164). HTP use intention and HTP-related harm and use perceptions relative to cigarettes and e-cigarettes were assessed.

Results

Overall, participants who viewed versus did not view the claim did not differ in HTP use intention (28.5% vs 28.7%) but were more likely to perceive HTPs as less harmful than cigarettes (11.4% vs 7.0%; p<0.001). The experimental effect on HTP use intention did not differ among past 30-day cigarette smokers versus non-smokers (interaction adjusted OR (AOR)=0.78, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.76) but differed among past 30-day e-cigarette users versus non-users (interaction AOR=1.67, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.68).

Discussion

The hypothetical MRTP claim may lower young adults’ HTP harm perceptions compared with cigarettes but may not change HTP use intention overall or differentially for cigarette smokers. The larger effect on HTP use intention among e-cigarette users than non-users raises the question of whether MRTP claims may promote HTP use or HTP and e-cigarette dual use among young e-cigarette users.

INTRODUCTION

Heated tobacco products (HTPs) are an emerging type of tobacco product engineered differently from conventional cigarettes and electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes).1 HTPs use battery power to heat processed tobacco leaves to a temperature intended to emit aerosol without combustion.1 The current most widely available HTP brand is Philip Morris International (PMI)’s IQOS, which was first launched in Japan, Italy, and Switzerland in 2014 and is currently sold in over 50 countries.2 3 More recently, sales of HTPs have begun to increase globally, often marketed as less harmful and reduced-risk alternatives to cigarette smoking.4 For example, in Japan, HTP use prevalence (among those aged 15–69 years) increased from 0.2% in 2015 to 11.3% in 2019, reaching 30% among cigarette smokers in 2019.5

In April 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorised the sale of the first HTP product—IQOS tobacco heating system, along with the tobacco-containing ‘Heatsticks,’ which included the tobacco, paper and filter inserted into the IQOS device.6 Although the overall prevalence of ever HTP use remains low among US adults (2%–5%),2 7 awareness of and interest in using HTPs is significantly higher among young adults versus adults of older age groups3 7 and cigarette smokers versus non-smokers.2 7 8 In July 2020, the FDA announced further authorisation for the marketing of IQOS as ‘modified risk tobacco products (MRTPs).9 The MRTP status allows companies to make marketing claims about their products as being reduced risk or reduced exposure relative to existing products on the market (eg, combustible cigarettes). In the case of IQOS, FDA authorised the ‘reduced exposure’ marketing claim, indicating the use of the product results in reduced exposure to harmful and potential harmful toxicants relative to cigarettes.9 The ‘reduced risk’ claim was not authorised because the product was not found to significantly reduce the harm and/or risk of tobacco-related diseases or provide population-level benefits for both users and non-users of tobacco products.10 A possible public health benefit of MRTP authorisation is to encourage long-term smokers to transition from cigarettes to HTPs as a reduced-exposure alternative.9

Policy-makers and public health researchers in the USA and other countries have emphasised the need to evaluate the influence of HTP-related claims that convey reduced risk, harm or exposure compared with cigarettes and other traditional tobacco products.9 11-16 It is critical to understand whether such marketing claims for HTPs may impact HTP use transition and uptake among the general population and conventional cigarette smokers. Additionally, given that the relative harm of e-cigarettes and HTPs is largely unknown, evidence that HTP MRTP claims may encourage the uptake of HTPs in e-cigarette users should be factored into regulatory decision making. Due to the recency of HTP MRTP authorisation, very limited research17 18 has been conducted to examine the potential effect of MRTP claims. These studies, however, did not examine HTP behavioural intentions among the overall study sample or HTP-related perceptions by participants’ tobacco use status. Research addressing these gaps is critically needed to inform FDA’s continued efforts of monitoring the impact of HTP MRTP authorisation on population health.9

Therefore, we implemented a randomised between-subjects experiment to examine the effect of exposure to a hypothetical HTP MRTP claim (a ‘reduced exposure’ claim) on the perceptions and use intention of HTPs among young adults. Young adults are a critical population to assess the effect of the HTP MRTP claim due to this group’s growing awareness and interest in using HTPs3 8 19 and vulnerability to tobacco marketing messages.20-22 Additionally, there are substantial societal benefits of cigarette smoking cessation during young adulthood before becoming vulnerable to the severe health effects of long-term cigarette smoking.23 24 In addition to examining the effect of the MRTP claim in the overall young adult sample, we examined whether the effect of MRTP claim exposure on HTP use intention and perception was moderated by current cigarette and e-cigarette use status.

METHODS

Study setting and design

Data were gathered from an ongoing prospective cohort study on behavioural health among a general population of young people living in southern California.25 The cohort was originally recruited from 10 high schools in Los Angeles, California, USA, beginning in Fall 2013, when students were in ninth grade (mean age: 14.1 years; N=3396). Participants were subsequently surveyed approximately every 6 months. The current study sample includes participants who completed the most recent wave administered via the Internet from May to October 2020 (mean age: 21.2 years; N=2354). After completing demographic characteristic and tobacco use measures, participants were randomly assigned to view the HTP messages with an MRTP claim (experimental group, n=1190) or without the claim (control group; n=1164). Both groups then completed identical measures of HTP use intention and relative perceptions of HTPs compared with cigarettes and e-cigarettes (see measures below). All participants completed informed consent prior to data collection.

HTP stimuli and MRTP claim exposure manipulation

During the survey, all participants were introduced to a set of stimuli depicting HTPs (figure 1). This included a text description about what HTPs are, an embedded short Graphics Interchange Format (GIF) video of someone using IQOS, and an advertisement for IQOS HEETS based on PMI’s marketing showing the product packaging with various flavours PMI markets globally. The stimuli in two experimental conditions were identical with the exception that those randomised to the experimental group were additionally shown a hypothetical MRTP claim immediately following the text about HTPs: ‘Since there is no burning, the levels of harmful chemicals are significantly reduced compared with cigarette smoke.’ The claim was constructed based on HTP marketing messages appearing on PMI’s official website26 which indicate the reduced exposure of using HTPs compared with conventional cigarette smoking. As the data collection for this study was implemented prior to FDA approval of IQOS as an MRTP, the ‘reduced exposure’ claim used in this experiment was slightly different than the FDA-approved MRTP claim which also stated that ‘complete switching’ from conventional cigarette smoking to HTP use may reduce exposure to harmful chemicals.9 Since the messages and advertisements used for constructing the stimuli were based on actual HTP product marketing materials, the stimuli were not pretested for understandability or readability. Immediately after viewing the HTP-related stimuli, participants were asked to answer a series of questions about their intention and perceptions of using HTPs.

Figure 1.

Messages of HTPs and HTP MRTP claim embedded in the survey. The bolded italicised text was the hypothetical MRTP claim only viewed by participants in the experimental group. HTPs, heated tobacco products; MRTP, modified risk tobacco product.

Measures of past 30-day tobacco product use

Before the MRTP exposure manipulation, participants completed past 30-day cigarette and e-cigarette use questions, including ‘In the past 30 days, how many total days have you used cigarettes?’ Those who reported using these products one or more days were considered past 30-day cigarette smokers (Yes/No). Similar questions were asked about three types of e-cigarettes products (ie, e-cigarettes with nicotine, e-cigarettes without nicotine or hash oil and other electronic vaping devices) and those who reported using any of those products in the past 30 days were considered as past 30-day e-cigarette users (yes/no). Additionally, past 30-day use of HTPs (Yes/No) was measured with the item stem ‘IQOS or other heated tobacco devices?’

Post-exposure measures of HTP outcomes

The intention of using HTPs was measured by the question, ‘If you had an opportunity to use a HTP, would you use it?’ Based on prior research studies that dichotomised tobacco use intention measures,27 28 we treated ‘Definitely no’ as having no intention to use HTPs. Those who answered, ‘probably not,’ ‘probably yes,’ and ‘definitely yes’ were considered to have HTP use intention.

Perceived relative harm of HTPs compared with cigarettes and e-cigarettes was measured by two separate survey items,29 30 ‘Do you think HTPs are more or less harmful than smoking cigarettes (OR using e-cigarettes)?’ The response options for both questions were ‘more harmful,’ ‘about the same,’ ‘less harmful,’ and ‘not sure.’ The responses to those questions were dichotomised into categories of Perceiving HTPs less harmful than cigarettes/e--cigarettes versus Other (including HTPs more harmful/about the same/not sure).

Perceived relative use of HTPs compared with cigarettes and e-cigarettes was measured by survey items,2 31 ‘Would you be more or less likely to use a HTP versus smoke cigarettes OR use e-cigarettes?’ The possible responses were ‘More likely to use a HTP’ ‘equally likely,’ ‘less likely to use a HTP,’ and ‘not sure.’ The responses to those questions were dichotomised into categories of perceiving a higher likelihood of using HTPs than cigarettes/e-cigarettes versus other (including less likely to use HTPs/equally likely/not sure).

Participant characteristics

Participants completed sociodemographic measures, including gender (male, female and other), sexual orientation (straight and other), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Asian, non-Hispanic other, Hispanic White, Hispanic other, Hispanic multiracial), highest education attainment (high school degree and lower, some college and associated degree and higher) and subjective financial situation (live comfortably and other).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was set to 0.05 (two tailed). Data were analysed using Stata V.16.0. First, participant characteristics were examined among the overall sample, by experimental condition and past 30-day cigarette and e-cigarette use status. Pearson χ2 tests were implemented to examine the differences between participant characteristics, experimental condition and cigarette and e-cigarette use status. Second, percentages of HTP use intention by experimental condition and past 30-day cigarette and e-cigarette use status were estimated. Pearson χ2 tests were implemented to assess the difference between HTP use intention by experimental condition among the overall sample and the samples stratified by past 30-day cigarette and e-cigarette use status. Third, five unadjusted logistic regressions were implemented to assess the associations between experimental condition and each postexposure HTP outcome (use intention, two relative harm perceptions and two relative use perceptions). Lastly, five multivariable logistic regressions were used to examine the associations between experimental condition, past 30-day cigarette and e-cigarette use, interactions of experimental condition with past 30-day cigarette and e-cigarette use and each post-exposure HTP outcome. A sensitivity analysis was conducted using the same regression models after excluding past 30-day HTP users (n=7) from the sample. Listwise deletion was used for analysis since participants missing at least one variable were minimal among the overall sample (<1%).

RESULTS

Participant characteristics and experimental condition

The analytical sample was 57.5% female, and the mean age was 21.2 years (age range=20.2–23.0 years; SD=0.4). Overall, 18.6%, 6.6% and 0.3% of the participants used e-cigarettes, cigarettes and HTPs in the past 30 days, respectively. χ2 tests showed that current cigarette smokers were more likely to be male than female (χ2=25.2; p<0.001) and heterosexual than other (χ2=23.5; p<0.001); similarly, current e-cigarette users were more likely to be male than female (χ2=15.7; p<0.001) and heterosexual than other (χ2=3.9; p<0.05). None of the participant characteristics differed meaningfully between the two experimental conditions (table 1).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and experimental conditions

| All Participants |

Experimental group |

Control group |

P value for test of group difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Age | 0.232 | |||

| <21 | 767 (32.6) | 374 (31.5) | 393 (33.8) | |

| ≥21 | 1586 (67.4) | 815 (68.5) | 771 (66.2) | |

| Gender | 0.488 | |||

| Female | 1351 (57.5) | 672 (56.2) | 679 (58.5) | |

| Male | 930 (39.5) | 479 (56.5) | 451 (38.9) | |

| Other | 70 (3.0) | 39 (3.3) | 31 (2.6) | |

| Sexual orientation | 0.573 | |||

| Heterosexual | 1818 (77.6) | 924 (78.1) | 894 (77.1) | |

| Other | 524 (22.4) | 259 (21.9) | 265 (22.9) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 0.370 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 360 (15.3) | 191 (16.1) | 169 (14.6) | |

| Hispanic white | 291 (12.4) | 133 (11.7) | 152 (13.1) | |

| Hispanic multiracial | 255 (10.9) | 133 (11.2) | 122 (10.5) | |

| Hispanic other | 754 (32.1) | 380 (32.0) | 374 (32.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 513 (21.8) | 268 (22.5) | 245 (21.1) | |

| Non-Hispanic other | 176 (7.5) | 78 (6.6) | 98 (8.5) | |

| Education | 0.754 | |||

| ≤High school | 636 (27.2) | 319 (27.0) | 317 (27.4) | |

| Some college | 1276 (54.6) | 650 (55.0) | 626 (54.2) | |

| ≥Associated degree | 427 (18.2) | 214 (18.0) | 213 (18.4) | |

| Subjective financial situation | 0.928 | |||

| Living comfortably | 1047 (44.8) | 526 (44.5) | 521 (45.1) | |

| Other | 1291 (55.2) | 657 (55.5) | 634 (54.9) | |

| Past 30-day e-cigarette use | 0.551 | |||

| No | 1920 (81.6) | 965 (81.1) | 955 (82.0) | |

| Yes | 434 (18.4) | 225 (18.9) | 209 (18.0) | |

| Past 30-day cigarette smoking | 0.291 | |||

| No | 2199 (93.4) | 1118 (94.0) | 1081 (92.9) | |

| Yes | 155 (6.6) | 72 (6.0) | 83 (7.1) | |

| Past 30-day heated tobacco product use | 0.269 | |||

| No | 2347 (99.7) | 1185 (99.6) | 1162 (99.8) | |

| Yes | 7 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 2 (0.2) |

Other’ category for subjective financial situation includes met needs with a little left, just meet basic expenses and don’t meet basic expenses.

‘Other’ category for sexual orientation includes asexual, bisexual, gay, lesbian, pansexual, queer, questioning or unsure, and other identities.

‘Other’ category for race/ethnicity includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islanders.

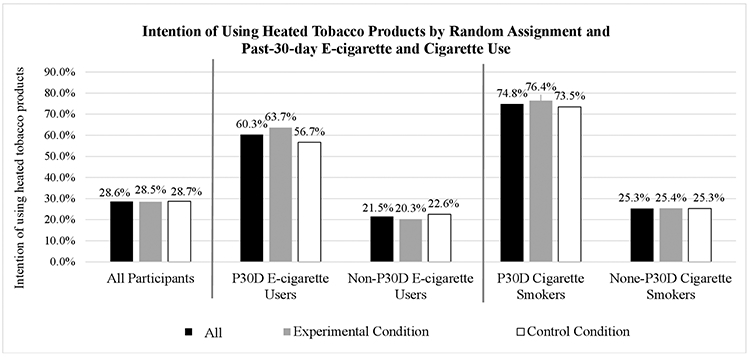

HTP use intentions by experimental condition and tobacco use status

Reported HTP use intention (figure 2) was more common among past 30-day users of cigarettes (74.8%) and e-cigarettes (60.3%) than among participants overall (28.6%). χ2 tests showed that HTP use intention was not statistically different by experimental condition among the overall sample or by current cigarette smoking or e-cigarette use status.

Figure 2.

Intention of using HTPs by experimental condition and past 30-day e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking status. HTPs, heated tobacco products.

Effect of claim exposure on HTP outcomes

Unadjusted logistic regression results (table 2) showed that exposure to the MRTP claim did not alter the intention of using HTPs in the overall sample (p=0.896). However, exposure to the MRTP claim was associated with perceiving HTPs less harmful than cigarettes versus other (OR=1.71; 95% CI 0.42 to 0.57; p<0.001); and exposure to the MRTP claim was associated with perceiving a higher likelihood of using HTPs than cigarettes versus other (OR=1.31; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.64; p<0.05).

Table 2.

The associations between experimental condition and postexposure HTP outcomes

| Associations between experimental condition and postexposure HTP outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All participants |

Experimental group |

Control group |

Unadjusted logistic regression results |

||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| HTP use intention | |||||

| No | 1672 (71.4) | 846 (71.5) | 826 (71.3) | Reference | |

| Yes | 670 (28.6) | 337 (28.5) | 333 (28.7) | 0.99 (0.83 to 1.18) | 0.896 |

| Relative harm of HTPs versus cigarettes | |||||

| HTPs more harmful/about the same/not sure | 2126 (90.8) | 1049 (88.6) | 1077 (93.0) | Reference | |

| HTPs less harmful | 216 (9.2) | 135 (11.4) | 81 (7.0) | 1.71 (1.28 to 2.82) | 0.000 |

| Relative harm of HTPs versus e-cigarettes | |||||

| HTPs more harmful/about the same/not sure | 2271 (97.2) | 1147 (97.0) | 1124 (97.3) | Reference | |

| HTPs less harmful | 66 (2.8) | 35 (3.0) | 31 (2.7) | 1.11 (0.68 to 1.81) | 0.686 |

| Relative use of HTPs versus cigarettes | |||||

| Less likely to use HTPs/equally likely/not sure | 1190 (85.1) | 980 (83.4) | 1004 (86.8) | Reference | |

| More likely to use HTPs | 348 (14.9) | 195 (16.6) | 153 (13.2) | 1.31 (1.03 to 1.64) | 0.023 |

| Relative use of HTPs versus e-cigarettes | |||||

| Less likely to use HTPs/equally likely/not sure | 2231 (95.5) | 1119 (95.1) | 1112 (95.9) | Reference | |

| More likely to use HTPs | 105 (4.5) | 58 (4.9) | 47 (4.1) | 1.23 (0.83 to 1.82) | 0.310 |

The results are from five unadjusted logistic regression models estimating the associations between experimental condition and postexposure HTP outcomes.

Bolded p values are statically significant (p<0.05).

HTPs, heated tobacco products.

Differential effect of claim exposure on HTP outcomes by tobacco use status

The multivariable logistic regression model (table 3) showed that past 30-day cigarette smoking (adjusted OR (AOR)=4.97, 95% CI 2.91 to 8.49, p<0.001), past 30-day e-cigarette use (AOR=3.35, 95% CI 2.40 to 4.68, p<0.001), and the interaction effect of past 30-day e-cigarette use with experimental condition (AOR=1.67, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.68, p<0.05) were associated with HTP use intention. The significant interaction suggested that the experimental effect on HTP use intention was different among past 30-day e-cigarette users (63.7% vs 56.7% for experimental and control groups) compared with non-users (20.3% vs 22.6% for experimental and control groups). The main experimental effect on HTP intention (AOR=0.90, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.13, p=0.375) or the interaction between experimental effect and past 30-day cigarette smoking (AOR=0.78, 95% CI 0.36 to 1.76, p=0.550) was not significant.

Table 3.

Experimental effect, tobacco use status and interaction effect between experimental condition and past 30-day tobacco use status

| Experimental effect, tobacco use status and Interaction effect between experimental condition and tobacco use status | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental condition main effect (ref. control group) |

Past 30-day cigarette smoking (ref. non-smoking) |

Past 30-day e-cigarette use (ref. non-e- cigarette use) |

Experimental condition X past 30-day cigarette smoking (ref. control group and non-smoking) |

Experimental condition X past 30-day e-cigarette use (ref. control group and non-e-cigarette use |

|||||||||||

| AOR | 95% CI | P value | AOR | 95% CI | P value | AOR | 95% CI | P value | AOR | 95% CI | P value | AOR | 95% CI | P value | |

| HTP use intention | |||||||||||||||

| No | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.90 | 0.72 to 1.13 | 0.375 | 4.97 | 2.91 to 8.49 | 0.000 | 3.35 | 2.40 to 4.68 | 0.000 | 0.78 | 0.36 to 1.76 | 0.550 | 1.67 | 1.02 to 2.68 | 0.046 |

| Relative harm of HTPs versus cigarettes | |||||||||||||||

| HTP more harmful/ same/not sure |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| HTP less harmful |

1.94 | 1.38 to 2.72 | 0.000 | 1.41 | 0.66 to 3.02 | 0.380 | 1.91 | 1.10 to 3.28 | 0.020 | 0.56 | 0.19 to 1.70 | 0.302 | 0.73 | 0.36 to 1.50 | 0.396 |

| Relative harm of HTPs versus e-cigarettes | |||||||||||||||

| HTP more harmful/ same/not sure |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| HTP less harmful |

1.14 | 0.65 to 2.01 | 0.640 | 0.30 | 0.04 to 2.31 | 0.246 | 1.96 | 0.85 to 4.56 | 0.117 | 2.67 | 0.20 to 15.21 | 0.455 | 0.69 | 0.21 to 2.30 | 0.544 |

| Relative use of HTPs versus cigarettes | |||||||||||||||

| Less likely to use HTP/ same/not sure |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| More likely to use HTP |

1.26 | 0.97 to 1.63 | 0.083 | 0.25 | 0.09 to 0.73 | 0.011 | 1.49 | 0.95 to 2.32 | 0.079 | 1.61 | 0.42 to 6.18 | 0.489 | 1.05 | 0.58 to 1.90 | 0.875 |

| Relative use of HTPs versus e-cigarettes | |||||||||||||||

| Less likely to use HTP/ same/not sure |

Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||||||||||

| More likely to use HTP |

1.26 | 0.83 to 1.92 | 0.285 | 0.66 | 0.15 to 2.97 | 0.592 | 0.72 | 0.29 to 1.78 | 0.478 | 2.15 | 0.29 to 15.76 | 0.450 | 0.61 | 0.16 to 2.26 | 0.457 |

The results are from five multivariable logistic regression models estimating the effects of experimental conditions, past 30-day cigarette smoking, past 30-day e-cigarette use, and two interaction terms on five postexposure HTP outcomes.

Bolded p values are statically significant (p<0.05).

AOR, adjusted OR; ; HTP, heated tobacco product.

The experimental effect and the current use of e-cigarettes remained statistically significant in the model for the outcome of perceiving HTPs less harmful than cigarettes versus other (AOR=1.94, 95% CI 1.38 to 2.72, p<0.001; and AOR=1.91, 95% CI 1.10 to 3.28, p<0.05). The experimental effect was not significant for other relative perception outcomes. No significant interactions of experimental condition with current cigarette smoking or e-cigarette use status were observed for the four relative perception outcomes. Current cigarette smokers had lower odds of being more likely to use HTPs than cigarettes versus other (AOR=0.25, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.73, p<0.05). Sensitivity analysis showed that after excluding past 30-day HTP users (n=7) from the overall sample, results were largely unchanged.

DISCUSSION

This randomised between-subjects experiment is one of the first to assess the effect of a hypothetical MRTP claim on young adults’ intention to use HTPs and their perceptions of HTPs compared with cigarettes and e-cigarettes. Although there was no association of MRTP claim exposure with intention to use HTPs overall, exposure to the claim may cause participants to develop lower harm perceptions of HTPs compared with cigarettes, which might lead to future HTP use intention and trial. Furthermore, the exposure to the claim did not lead to a higher HTP use intention among current cigarette smokers, for whom HTP use may be most beneficial. However, the effect of claim exposure on HTP use intention differed among past 30-day e-cigarette users versus non-users.

Our study demonstrated that although the absolute percentage of participants who perceived HTP as less harmful than cigarettes was small, those exposed to the MRTP claim had a higher likelihood of reporting such relative perception than those not exposed. This result is consistent with previous studies that found significant effects of viewing comparative risk messages and warning labels on relative harm and risks perceptions of tobacco product use.17 32-34 Young adults may increasingly develop the perceptions that HTPs are less harmful than cigarettes through repeated exposure to such claims in the real world. This may be concerning since a well-established body of evidence has also shown that low absolute or relative harm perceptions towards a tobacco product are associated with tobacco product initiation and regular use among young people.17 35 36 Consequently, such relative perceptions may prompt future HTP experimentation and regular use among those who would not otherwise smoke cigarettes or other forms of tobacco products, resulting in exacerbated adverse population health outcomes. More research is needed to elucidate how HTP MRTP claims are perceived and linked to relative harm of and intentions to use HTPs compared with cigarettes and how those perceptions may lead to HTP product use among young adults in general and by their risks of smoking cigarettes and using other tobacco.

The effect of the MRTP claim exposure on HTP use intention was not significant among current cigarette smokers and did not differ among cigarette smokers versus non-smokers. It is possible that young adult cigarette smokers do not perceive the ‘reduced exposure’ outcomes of using HTPs as an important reason for trying HTPs. It is also possible that simply through viewing the text describing HTPs and its use, HTP packaging with various flavours, and an actor using an HTP (shown in figure 1), young adult cigarette smokers in our study have already developed an interest in trying the product, as 74.8% of them endorsed possible HTP use intention. Therefore, additionally viewing the claim may be unlikely to further increase cigarette smokers’ interest in using the product. This finding may not support the FDA’s original intent of HTP MRTP authorisation to help adult cigarette smokers completely transition away from smoking conventional cigarettes through using HTPs.9 The FDA may need to further evaluate the appeal of HTP MRTP claims in adult cigarette smokers and determine whether such claims may increase smokers’ complete switching to HTPs, a behavioural change that may benefit the overall population health.

On the other hand, our finding suggested that the effect of the MRTP claim on HTP use intention differed among young adult e-cigarette users versus non-users. Specifically, among current e-cigarette users, those who viewed the MRTP claim had a higher (but not significantly different) intention of using HTPs than those who did not view the claim; however, among non-e-cigarette users, young adults from two experimental conditions had an equivalent level of HTP use intention. We suspect that this may be because young adult e-cigarette users viewed HTPs’ feature of reduced toxin exposure similar to that of e-cigarette products and therefore developed an interest in trying the HTP product. This group may also be influenced by the ‘halo effect’ of viewing MRTP claims,37 thereby making an unintended generalisation about the absolute harm of using HTPs.

Since the US FDA approved MRTP authorisation for HTPs by evaluating the evidence comparing HTPs with combustible cigarettes,9 12 its potential harm relative to e-cigarette products remains unclear. It is plausible that HTPs are more harmful than e-cigarettes since recent research has shown that HTP use produces many of the same harmful constituents of conventional tobacco cigarette smoking38 and has higher toxic effects of inhaling emissions than e-cigarette use.39 Additionally, evidence has shown that HTPs may contain nicotine levels close to those of conventional cigarettes,40 indicating HTPs’ strong addictive potential and abuse liability if used among tobacco-naive individuals. Therefore, if HTPs do indeed pose more harm than e-cigarettes, our finding suggesting that HTP MRTP claims might disproportionately increase use intention among young adult e-cigarette users is concerning. Possible transition to using HTPs and long-term dual use of both HTPs and e-cigarettes may result in increased harm to the population of young adult e-cigarette users and could raise concerns about authorising MRTP claims for this group. Regardless, when assessing the population health impact of HTP use, it is critical to evaluate the harm and risks of HTP use compared with e-cigarette use, along with the possibility of product transition from e-cigarettes to HTPs and long-term dual use of both products.

This study should be considered with the following limitations. First, how the officially FDA-approved MRTP claim indicating ‘complete switching’ is perceived among young adults may be different than the claim used in our study. Second, the HTP advertisement embedded in this experiment featured HEETS products which are marketed as Marlboro Heatsticks in the USA. This advertisement also featured various non-tobacco and non-menthol flavours not currently available in the US market. Given flavours’ appeal to young adults,41 42 HTP use intention reported in the current sample might be higher than the intention reported in a sample exposed to the advertisements available in the USA. where only tobacco and menthol flavours are marketed. Third, the MRTP claim was only viewed once (in a plain text format) by the experimental group. In the real world, young adults may be exposed repeatedly to MRTP claims through various sources, including retailers and the internet/social media. The real-world exposure may potentially increase the appeal and recall of the claims, exacerbating its influence on HTP-related perceptions and behaviour. Finally, future research should investigate how viewing HTP MRTP claims may influence the transition or switching to using HTPs among dual users of e-cigarettes and cigarettes as this group may be exposed to higher levels of toxins than cigarette and e-cigarette only users.43 44

Given the uncertain impact of HTPs on individual-level and population-level health, timely evidence is critically needed to assess how FDA-approved MRTP claims may alter the public’s perceptions and use of HTPs. If future evidence shows that MRTP claims fail to increase HTP uptake among cigarette smokers and that relative lower harm perceptions of HTPs and higher intentions of using HTPs compared with cigarettes lead to HTP uptake among non-cigarette-smoking individuals, then the FDA should re-evaluate the authorisation of MRTP status for HTPs. Additionally, more evidence comparing the harm and risks of using HTPs with e-cigarettes is greatly needed since, with the appeal of MRTP messages, it is likely that young adult e-cigarette users will initiate and use HTPs.

CONCLUSION

The results from this randomised experiment indicated that HTP MRTP claims may lead to reduced HTP harm perceptions compared with cigarettes among young adults in general while fail to change or increase HTP use intention among cigarette smokers, potentially contradicting the FDA’s original intent of authorising MRTP claims for HTPs. The results also suggested that MRTP claim exposure may be associated with a larger effect on HTP use intention among young adult e-cigarette users than non-users, possibly leading to young adult e-cigarette users’ transition to a more harmful tobacco product. Taken together, these results may be troubling when considering the overall population health impact of HTP MRTP claims on tobacco product initiation and transition. Tobacco product regulators may need to further evaluate the appeal and effect of MRTP claims among young adults in general and by tobacco use status for all products, not only cigarettes.

What this paper adds.

Tobacco marketing messages conveying lower harm or risks from using the product may encourage product use intention and transition.

Few studies are available assessing the effect of ‘modified risk tobacco product (MRTP)’ claims on heated tobacco product (HTP) use intention and perceptions among young people.

The results from this randomised experiment showed young adults who viewed versus did not view the MRTP claim did not differ in HTP use intention but were more likely to perceive HTP less harmful than cigarettes.

The effect of the MRTP claim exposure on HTP use intention significantly differed for e-cigarette users versus non-users; no differential effect by cigarette smoking status was observed.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant numbers U54CA180905, U54HL147127, R01CA229617, K24DA048160, K99CA242589 and K01DA042950. JCC-S is also supported by the Division of Intramural Research, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Comments and opinions expressed belong to the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the US Government, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities or the FDA.

Footnotes

Competing interests No, there are no competing interests.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval The University of Southern California Institutional Review Board approved this study (IRB identification number: HS-12-00180).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

REFERENCES

- 1.O’Connell G, Wilkinson P, Burseg KMM. Heated tobacco products create side-stream emissions: implications for regulation. J Env Anal Chem 2015;2:163. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunbar MS, Seelam R, Tucker JS, et al. Correlates of awareness and use of heated tobacco products in a sample of US young adults in 2018-2019. Nicotine Tob Res 2020;22:2178–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marynak KL, Wang TW, King BA, et al. Awareness and ever use of "heat-not-burn" tobacco products among U.S. adults, 2017. Am J Prev Med 2018;55:551–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elias J, Dutra LM, St Helen G, et al. Revolution or redux? assessing IQOS through a precursor product. Tob Control 2018;27:s102–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hori A, Tabuchi T, Kunugita N. Rapid increase in heated tobacco product (HTP) use from 2015 to 2019: from the Japan ‘Society and New Tobacco’ Internet Survey (JASTIS). Tob Control 2020. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055652. [Epub ahead of print: 05 Jun 2020] (Published Online First: 05 June 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Fda permits sale of IQOS tobacco heating system through premarket tobacco product application pathway, 2019. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-permits-sale-iqos-tobacco-heating-system-through-premarket-tobacco-product-application-pathway

- 7.Nyman AL, Weaver SR, Popova L, et al. Awareness and use of heated tobacco products among US adults, 2016-2017. Tob Control 2018;27:s55–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Phan L, Strasser AA, Johnson AC, et al. Young adult correlates of IQOS curiosity, interest, and likelihood of use. tob regul sci 2020;6:81–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.The U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA authorizes marketing of IQOS Tobacco heating system with ‘reduced exposure’ information, 2020. Available: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-marketing-iqos-tobacco-heating-system-reduced-exposure-information

- 10.The U.S. Congress. Family Smoking and Prevention Tobacco Control Act. 21 U.S.C. § 387p(a)(2),(B) (2013) 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lempert L, Kim M, Chaffee BW FDA should not authorize Philip Morris international to market IQOS with claims of reduced risk or reduced exposure, 2020. Available: https://tobacco.ucsf.edu/fda-should-not-authorize-philip-morris-international-market-iqos-claims-reduced-risk-or-reduced-exposure

- 12.St Helen G, Jacob lii P, Nardone N, et al. IQOS: examination of Philip Morris international’s claim of reduced exposure. Tob Control 2018;27:s30–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McKelvey K, Popova L, Kim M, et al. IQOS labelling will mislead consumers. Tob Control 2018;27:s48–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lempert LK, Glantz S Analysis of FDA’s IQOS marketing authorisation and its policy impacts. Tob Control 2020. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055585. [Epub ahead of print: 29 Jun 2020] (Published Online First: 29 June 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halpern-Felsher B, Henigan D, Riordan M, et al. The importance of including youth research in premarket tobacco product and modified risk tobacco product applications to the food and drug administration. J Adolesc Health 2020;67:331–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Orgnization (WHO). Heated tobacco products (HTPs) market monitoring information sheet, 2021. Available: http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/prod_regulation/htps-marketing-monitoring/en/

- 17.McKelvey K, Baiocchi M, Halpern-Felsher B Pmi’s heated tobacco products marketing claims of reduced risk and reduced exposure may entice youth to try and continue using these products. Tob Control 2020;29:e18–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wackowski OA, O’Connor RJ, Pearson JL Smokers’ Exposure to Perceived Modified Risk Claims for E-Cigarettes, Snus, and Smokeless Tobacco in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res 2021;23:605–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim M, Watkins SL, Koester KA, et al. Unboxed: US young adult tobacco users’ responses to a new heated tobacco product. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:8108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilpin EA, Pierce JP, Rosbrook B Are adolescents receptive to current sales promotion practices of the tobacco industry? Prev Med 1997;26:14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feighery E, Borzekowski DL, Schooler C, et al. Seeing, wanting, owning: the relationship between receptivity to tobacco marketing and smoking susceptibility in young people. Tob Control 1998;7:123–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biener L, Albers AB Young adults: vulnerable new targets of tobacco marketing. Am J Public Health 2004;94:326–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor DH, Hasselblad V, Henley SJ, et al. Benefits of smoking cessation for longevity. Am J Public Health 2002;92:990–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doll R, Peto R, Boreham J, et al. Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors. BMJ 2004:328:1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cwalina SN, Braymiller JL, Leventhal AM, et al. Prevalence of young adult vaping, substance vaped, and purchase location across 5 categories of vaping devices. Nicotine Tob Res 2020:ntaa232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Philip Morris International. What is IQOS? 2021. Available: https://www.pmi.com/faq-section/faq/what-is-iqos

- 27.Wills TA, Sargent JD, Knight R, et al. E-Cigarette use and willingness to smoke: a sample of adolescent non-smokers. Tob Control 2016;25:e52–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen-Sankey JC, Unger JB, Bansal-Travers M, et al. E-Cigarette marketing exposure and subsequent experimentation among youth and young adults. Pediatrics 2019;144:e20191119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ambrose BK, Rostron BL, Johnson SE, et al. Perceptions of the relative harm of cigarettes and e-cigarettes among U.S. youth. Am J Prev Med 2014;47:S53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brose LS, Brown J, Hitchman SC, et al. Perceived relative harm of electronic cigarettes over time and impact on subsequent use. A survey with 1-year and 2-year follow-ups. Drug Alcohol Depend 2015;157:106–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fong GT, Elton-Marshall T, Driezen P, et al. U.S. adult perceptions of the harmfulness of tobacco products: descriptive findings from the 2013-14 baseline wave 1 of the path study. Addict Behav 2019;91:180–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang B, Owusu D, Popova L Testing messages about comparative risk of electronic cigarettes and combusted cigarettes. Tob Control 2019;28:440–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Andrews JC, Netemeyer RG, Burton S, et al. Effects of plain package branding and graphic health warnings on adolescent smokers in the USA, Spain and France. Tob Control 2016;25:e120–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimber C, Frings D, Cox S, et al. Communicating the relative health risks of e-cigarettes: an online experimental study exploring the effects of a comparative health message versus the EU nicotine addiction warnings on smokers’ and non-smokers’ risk perceptions and behavioural intentions. Addict Behav 2020;101:106177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parker MA, Villanti AC, Quisenberry AJ, et al. Tobacco product harm perceptions and new use. Pediatrics 2018;142:e20181505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Strong DR, Leas E, Elton-Marshall T, et al. Harm perceptions and tobacco use initiation among youth in wave 1 and 2 of the population assessment of tobacco and health (path) study. Prev Med 2019;123:185–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seidenberg AB, Popova L, Ashley DL, et al. Inferences beyond a claim: a typology of potential halo effects related to modified risk tobacco product claims. Tob Control 2020. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2019-055560. [Epub ahead of print: 12 Oct 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Auer R, Concha-Lozano N, Jacot-Sadowski I, et al. Heat-not-burn tobacco cigarettes: smoke by any other name. JAMA Intern Med 2017;177:1050–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leigh NJ, Tran PL, O’Connor RJ, et al. Cytotoxic effects of heated tobacco products (HTP) on human bronchial epithelial cells. Tob Control 2018;27:s26–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salman R, Talih S, El-Hage R, et al. Free-base and total nicotine, reactive oxygen species, and carbonyl emissions from IQOS, a heated tobacco product. Nicotine Tob Res 2019;21:1285–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Villanti AC, Richardson A, Vallone DM, et al. Flavored tobacco product use among U.S. young adults. Am J Prev Med 2013;44:388–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harrell MB, Loukas A, Jackson CD, et al. Flavored Tobacco Product Use among Youth and Young Adults: What if Flavors Didn’t Exist? Tob Regul Sci 2017;3:168–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goniewicz ML, Smith DM, Edwards KC, et al. Comparison of nicotine and toxicant exposure in users of electronic cigarettes and combustible cigarettes. JAMA Netw Open 2018;1:e185937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wang JB, Olgin JE, Nah G, et al. Cigarette and e-cigarette dual use and risk of cardiopulmonary symptoms in the health eHeart study. PLoS One 2018;13:e0198681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]