Abstract

Methane-generating archaea drive the final step in anaerobic organic compound mineralization and dictate the carbon flow of Earth’s diverse anoxic ecosystems in the absence of inorganic electron acceptors. Although such Archaea were presumed to be restricted to life on simple compounds like hydrogen (H2), acetate or methanol, an archaeon, Methermicoccus shengliensis, was recently found to convert methoxylated aromatic compounds to methane. Methoxylated aromatic compounds are important components of lignin and coal, and are present in most subsurface sediments. Despite the novelty of such a methoxydotrophic archaeon its metabolism has not yet been explored. In this study, transcriptomics and proteomics reveal that under methoxydotrophic growth M. shengliensis expresses an O-demethylation/methyltransferase system related to the one used by acetogenic bacteria. Enzymatic assays provide evidence for a two step-mechanisms in which the methyl-group from the methoxy compound is (1) transferred on cobalamin and (2) further transferred on the C1-carrier tetrahydromethanopterin, a mechanism distinct from conventional methanogenic methyl-transfer systems which use coenzyme M as final acceptor. We further hypothesize that this likely leads to an atypical use of the methanogenesis pathway that derives cellular energy from methyl transfer (Mtr) rather than electron transfer (F420H2 re-oxidation) as found for methylotrophic methanogenesis.

Subject terms: Archaeal physiology, Soil microbiology, Proteomics

Introduction

Methanogenesis evolved more than 3.46 Gyr ago and has profoundly contributed to Earth’s climate [1, 2]. About 70% of the emitted methane (CH4) is produced by methane-generating archaea (methanogens; [3]) underlining the importance of methanogenesis for the global carbon cycle. Methanogens are known to produce methane from one- to two-carbon substrates (i.e., carbon dioxide [CO2], acetate, and methylated compounds), often using (in)organic compounds as electron donors (e.g., hydrogen [H2] and formate). Three major pathways of methanogenesis are known. In the hydrogenotrophic pathway, H2 (or formate) are used as electron donors with carbon dioxide as electron acceptor. In the methylotrophic pathway, small methylated carbon compounds are converted to methane and carbon dioxide. In the aceticlastic pathway, acetate is cleaved to methane and carbon dioxide [4]. Beyond this, a thermophilic methanogen isolated from a deep subsurface environment [5], Methermicoccus shengliensis, was recently discovered to directly generate methane from a variety of methoxylated aromatic compounds (ArOCH3) [6]. Methoxylated aromatic compounds are derived from lignin and occur in large quantities on Earth [7]. The environmental abundance of methoxylated aromatics indicates that methoxydotrophic archaea might play a so far unrecognized and underestimated role in methane formation and carbon cycling of coal, lignin, and other humic substances, especially in the subsurface [8]. Aromatic compounds are a major component of crude oil with about 20–43% [9, 10], and it is quite likely that methoxylated aromatic compounds in oil might be degraded by methoxydotrophic organisms. As M. shengliensis has been isolated from oil production water [5], the organism might play a role in the degradation of methoxy compounds in oil reservoirs. Next to oil, methoxylated aromatic compounds are components of coal. Although conversion of coal compounds to methane has been thought to require metabolic interactions [11], Methermicoccus’ ability to accomplish this alone might have significant implications for coalbed methane formation (7% of global annual methane formation [12]), including enhanced methane recovery [13]. Therefore, it is important to understand the unique methoxy compound-degrading methane-forming metabolism of M. shengliensis.

The discovery of the methoxydotrophic ability of M. shengliensis revealed that the capacity to degrade methoxylated aromatic compounds is not confined to bacteria as previously thought, yet how M. shengliensis (and thus archaea) accomplish methoxydotrophic methanogenesis remains unknown. The organism is also capable of and possesses the necessary genes for methylotrophic methanogenesis [6], in which a methylated substrate (e.g., methanol) is disproportionated to ¾ CH4 and ¼ CO2. In principle, degradation of methoxy groups could follow a similar pathway, given that methyl and methoxy groups have the same oxidation state. However, isotope-based investigation showed that methoxydotrophic methanogenesis unprecedentedly entails both methyl disproportionation and CO2 reduction to CH4 [6], suggesting the involvement of a novel methanogenic pathway. In this study, integration of genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics reveals that M. shengliensis methoxydotrophy employs a novel methyltransferase system for ArOCH3 O-demethylation. While known methanogens transfer methyl compounds using coenzyme M (CoM) as a C1 carrier [14], we suggest that the M. shengliensis ArOCH3 methyltransferase rather uses tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT) as final C1 carrier. The different entry point into methanogenesis (i.e., as CH3-H4MPT rather than CH3-CoM) putatively prompts changes in energetics, thermodynamics, and kinetics that might involve an idiosyncratic C1 catabolism cycling between oxidation and reduction.

Materials and methods

Genome analysis

The functions of individual proteins were predicted using homology, phylogeny, and domain identification. Homology of M. shengliensis proteins with proteins in reference genomes was calculated using NCBI blastp. For each protein, phylogenetic analysis was performed by collecting homologues from the SwissProt and UniProt databases [15], protein sequence alignment using MAFFT v7.394 [16], and phylogenetic tree construction using RAxML-NG v0.5.1b [17] or FastTree v 2.2.11 [18]. Annotations were verified using domain-based function annotation involving NCBI CD-SEARCH/CDD v3.18 (10.1093/nar/gku1221), InterProScan v5 [19], SignalP 4.1 [20], and Prosite (https://prosite.expasy.org).

Cultivation of Methermicoccus shengliensis

M. shengliensis AmaM was cultivated as described previously [6]. The following medium was used for the AmaM cultures: a bicarbonate-buffered mineral medium (pH 7.0) [21] containing 0.15 g l−1 KH2PO4, 0.5 g l−1 NH4Cl, 0.2 g l−1 MgCl2·6H2O, 0.15 g l−1 CaCl2·2H2Og, 2.5 g l−1 NaHCO3, 0.3 g l−1 cysteine·HCl, 0.3 g l−1 Na2S·9H2O, 20.5 g l−1 NaCl, 1 ml trace elements solution (DSMZ medium 318 with slight modifications: NaCl was eliminated, and 3 mg l−1 of Na2WO4·2H2O and 2 mg l−1 of Na2SeO3 were added), 1 ml vitamin solution (DSMZ medium 141 with a slight modification: all components were mixed at a concentration of 20 μmol l−1), and 1 ml resazurin solution (1 mg ml−1). As an energy source, cultures were grown with either methanol (MeOH) (10 mM), trimethylamine (10 mM), 2-methoxybenzoate (10 mM), or 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoate (TMB) (10 mM). A 0.5 M stock solution of TMB was produced by dissolving 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoic acid in water and adjusting the pH to 7 with NaOH.

Methermicoccus shengliensis ZC-1 (DSM 18856) was obtained from the DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany) and cultivated in modified DSM medium 1084. Sludge fluid was replaced by trace element solution (100 x trace element solution: 1.5 g l−1 nitrilotriacetic acid, 3 g l−1 MgSO4·7 H2O, 0.45 g l−1 MnSO4·2 H2O, 1 g l−1 NaCl, 0.1 g l−1 FeSO4·7 H2O, 0.18 g l−1 CoSO4·6 H2O, 0.1 g l−1 CaCl2·2 H2O, 0.18 g l−1 ZnSO4·7 H2O, 0.01 g l−1 CuSO4·5 H2O, 0.02 g l−1 KAl(SO4)2·12 H2O, 0.01 g l−1 H3BO3, 0.01 g l−1 Na2WO4·2 H2O, 0.01 g l−1 Na2MoO4·2 H2O, 0.025 g l−1 NiCl2·6 H2O, 0.01 g l−1 Na2SeO3) and vitamin solution (1000 x vitamin solution: 20 mg l−1 biotin, 20 mg l−1 folic acid, 100 mg l−1 pyridoxine-HCl, 50 mg l−1 thiamin-HCl·2 H2O, 50 mg l−1 riboflavin, 50 mg l−1 nicotinic acid, 50 mg l−1 D-Ca-pantothenate, 2 mg l−1 vitamin B12, 50 mg l−1 p-aminobenzoic acid, 50 mg l−1 lipoic acid). The amount of supplied coenzyme M was reduced 20-fold (0.13 g l−1) and 2.5 g l−1 NaHCO3 instead of 1 g l−1 Na2CO3 was used. The medium was sparged with N2:CO2 in a 80:20 ratio before autoclaving. As substrate either 150 mM MeOH or 10 mM TMB were used. The cultures were incubated at 65 °C. Identity of the organism was checked by 16 S rRNA gene sequencing of DNA from TMB grown cell with primers Arch349F (5′-GYGCAGCAGGCGCGAAA-3′) and Arch806R (5′-GGACTACVSGGGTATCTAAT-3′) [22].

RNA isolation from M. shengliensis cells and sequencing

For transcriptomics, M. shengliensis AmaM was cultivated in 130-ml serum vials containing 50 ml of the medium with 10 mM MeOH, 2-methoxybenzoate, trimethylamine, or TMB as the sole organic carbon substrate. Total RNA was extracted from the cells harvested in the exponential growth phase through brief centrifugation (3 min at 9000 × g at room temperature) using methods described by Schmidt et al. [23] with slight modifications. In brief, after adding extraction buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl, 0.1 M ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.75 M sucrose), cells were enzymatically and chemically lysed by lysozyme (1 mg ml−1), achromopeptidase (0.01 mg ml−1), proteinase K (0.1 mg ml−1), and sodium dodecyl sulfate (1% [w/v]). The nucleic acid fraction was extracted using cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (1% [w/v]) and chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1). Extracted nucleic acids were precipitated with isopropanol and washed with ethanol, and then fractionated into DNA and RNA by ALLPrep DNA/RNA mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA samples were treated with DNase to remove DNA contaminants. Removal of DNA contamination from the samples was confirmed by PCR amplification. RNA concentrations were measured using a Nanodrop 2000c and Qubit Fluorometer using Qubit RNA HS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA).

The resulting cDNA was fragmented using Bioruptor (Diagenode, Inc., Denville, NJ USA), profiled using Agilent Tapestation, and subjected to Beckman Biomek FXp (Biomek 6000, Beckman Coulter) fully automatic workstation and a Beckman HT library kit (SPRIworks HT, Beckman Coulter, Inc. CA USA; PN B09855AA) to generate fragment libraries. The instructions were strictly followed to perform library construction. Briefly, after fragmentation the ends were repaired and the fragments were subsequently adenylated. Adapters were then ligated to both ends. The adaptor-ligated templates were further purified using Agencourt AMPure SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter, Inc. CA USA). The adaptor-ligated library was amplified by ligation-mediated PCR which consisted of 11 cycles of amplification, and the PCR product was purified using Agencourt AMPure SPRI beads again. After the library construction procedure was completed, QC was performed using Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Scientific, USA) and an Agilent TapeStation (Agilent, USA) to ensure the library quality and quantity. Alternatively, cDNA was profiled using Agilent Bioanalyzer, and subjected to library preparation using NEBNext reagents (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA USA, catalog# E6040). The quality and quantity and size distribution of the libraries were determined using an Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100.

Sequencing was performed on the HiSeq 2500 (Rapid run, Illumina, CA USA) with chemistry v3.0 and using the 2 × 100 bp paired-end read mode and original chemistry from Illumina according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The initial data analysis was started directly on the HiSeq 2500 System during the run. The HiSeq Control Software 2.0.5 in combination with RTA 1.17.20.0 (real-time analysis) performed the initial image analysis and base calling. In addition, CASAVA-1.8.2 generated and reported run statistics and the final FASTQ files comprising the sequence information which was used for all subsequent bioinformatics analyses. Sequences were de-multiplexed according to the 6 bp index code with 1 mismatch allowed. Alternatively, the libraries were then submitted for Illumina HiSeq2000 sequencing according to the standard operation. Paired-end 90 or 100 nucleotide (nt) reads were generated, checked for data quality using FASTQC (Babraham Institute, Cambridge, UK).

For M. shengliensis ZC-1, cells were harvested in the exponential phase (MeOH grown cells: OD600 0.150 to 0.240 and TMB grown cells: OD600 0.110 to 0.180) at 10,000 × g, 25 min and 4 °C. The pellet was frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until RNA isolation. RNA isolation was performed with the RiboPure-Bacteria Kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Quantity and quality of RNA from MeOH and TMB grown cells (in triplicates) was checked with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and the RNA Integrity Number was between 7.2 and 8.2.

For library preparation the TruSeq Stranded mRNA Library Prep protocol (Illumina, San Diego, California USA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was used for library preparation. The library concentration measured with a Qubit fluorometer and the average fragment size obtained with the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer were used to calculate the correct dilution factor required for normalization of the library. After dilution to 4 nM and denaturation using the Denature and Dilute Libraries Guide (Illumina, San Diego, CA), the library was sequenced using a MiSeq machine (Illumina, San Diego, CA) to generate 150 bp single-end reads.

To analyze the AmaM and ZC-1 transcriptomic data, raw reads from the MiSeq platform were trimmed using Trimmomatic v0.36 (SLIDINGWINDOW:6:30 MINLEN:50 LEADING:3 TRAILING:3) [24] and mapped to the respective genomes (AmaM – JGI IMG/M ID 2516653088; ZC-1 – GenBank accession number NZ_JONQ00000000.1) using BBMap v38.26 (semiperfectmode = t) (https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/).

Analysis of M. shengliensis ZC-1 whole cell proteome

After cultivation of M. shengliensis in medium with either MeOH or TMB as substrate cells were harvested anaerobically (13,000 × g, 25 min) in the exponential phase (OD600nm 0.2–0.4), pellets were frozen in liquid nitrogen and freeze-dried before they were stored at −80 °C in quadruplicates.

After adding 400 µL ammonium bicarbonate (100 mM, pH 8) and resuspending, the samples were transferred together with 300 µL TEAB resuspension buffer (50 mM triethylammonium bicarbonate, 1% (w/w) sodium deoxycholate, pH 8.0) and 300 µL B-PER reagent (Thermo Fisher) to 200 mg glass beads in shock resistant 2 mL tubes. Bead beating was performed using Precellys 24 (Bertin Technologies, France) at 6000 rpm for 20 s with a 30 s break for three cycles. After centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, supernatant was transferred to a 1.5 mL Eppendorf tube.

To precipitate the proteins one volume 100% TCA was added to four volumes of protein extract. After incubation at 4 °C for 10 min, the supernatant was removed and the pellet washed two times with 200 µL ice cold acetone (centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C). The pellet was dried at 95 °C for 5 min and resuspended in 50 µL ammonium bicarbonate (100 mM, pH 8). Protein concentration was estimated using Qubit Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

In solution digestion was performed by adding one volume TEAB resuspension buffer to the protein extracts followed by incubation at 99 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, samples were reduced using 1 µg TCEP per 25 µg protein and incubation at 37 °C for 30 min, and alkylated with 1 µg Iodoacetamide per 10 µg protein followed by incubation at 37 °C for 20 min in the dark. Digestion was performed using 1 µg trypsin per 50 µg protein and incubation at 37 °C for 16 h. A final concentration of 2% formic acid was added to the samples and after 5 min incubation at room temperature, the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred into a new tube.

Samples were desalted using a modified StageTIP protocol [25] and subsequently lyophilised in a SpeedVac centrifuge. Peptides were reconstituted in 2% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid prior to analysis.

LC-MS/MS analysis of the samples was performed using an Easy-nLC 1200 system (Thermo Scientific) coupled to a Q Exactive HF mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) through a Nanospray Flex ion source (Thermo Scientific). Peptides were loaded onto an Acclaim PepMap 100 (100 μm × 2 cm, NanoViper, C18, 5 μm, 100 A) (Thermo Scientific) trap column and separated on an analytical column at a flow rate of 300 nL min−1, during a 40 min linear gradient, ranging from 0 to 100% of a mobile phase containing acetonitrile.

Mass spectrometry was performed in positive mode only, fragmenting precursors with an assigned charge of ≥2. An isolation window of 1.2 m/z was used and survey scans were acquired at 400–1200 m/z at resolution 60,000 at m/z 200, and fragmentation spectra were captured at 15,000 at m/z 200. Maximum ion injection time was set to 50 ms for MS and 45 ms for MS/MS scans. Automatic gain for survey scans was set to 1e6 ions and 1e5 ions for fragmentation scans. The apex trigger was not set, the intensity threshold was set to 4.4e4 ions and dynamic exclusion of 30 s was applied. Normalized Collision Energy was set to 28, “peptide match” was set to “preferred” and “exclude isotopes” was enabled.

Q-exactive RAW data files were processed using MaxQuant (v1.6.3.4) [26], with carbamidomethylation set as a fixed modification and methionine oxidation as a variable modification, a protein, and peptide false discovery rate (FDR) of 1% and label-free quantification (LFQ) as implemented in MaxQuant. Data were searched against a database consisting of the predicted open reading frames (ORFs) of the draft genome of M. shengliensis ZC-1 (NZ_JONQ00000000.1), as well as the ORFs of closely related organisms Methanothrix thermoacetophila (UP000000674), Methanothrix harundinacea (UP000005877), Methanosarcina barkeri (UP000033066), Methanolacinia petrolearia (UP000006565) and Methanomethylovorans hollandica (UP000010866), downloaded from UniProt on 18-01-2019.

Data analysis was performed using Perseus (v1.6.2.3) [27]. Student’s t test was performed using a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 and permutation-based FDR at 5%. The relative protein abundances were represented as Log2-transformed LFQ values. Fold change was expressed as the ratio of averaged LFQ value of a protein across all replications of M. shengliensis fed with TMB divided by the averaged LFQ value of those fed with methanol.

Native purification of MtoA and MtoB from M. shengliensis

All steps were performed under an anaerobic atmosphere and all buffers were prepared anaerobically. About 6 g (wet weight) of M. shengliensis ZC-1 cells harvested in the late exponential phase were defrosted while gassing for 10 min with N2 gas and passed in an anaerobic tent containing an atmosphere of N2/CO2 at a ratio of 90:10%. Afterwards, cells were resuspended in 20 mL anaerobic IECA buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 8, 2 mM dithiothreitol abbreviated as DTT), sonicated (Bandelin sonopuls 6 × 50 % power for 10 s with 20 s break) and centrifuged (13,000 × g, 30 min at room temperature) to remove cell debris. The supernatant was collected and the pellets were resuspended in 10 ml anaerobic IECA buffer, sonicated (5 × 50 % power for 10 s with 20 s break), centrifuged (13,000 × g, 30 min) and the supernatant combined with the supernatant from the previous step. The supernatant was anaerobically transferred to a Coy tent containing a gas atmosphere of N2/H2 at a ratio of 97:3% and was then diluted fourfold with IECA buffer, filtered through 0.2 μm filters (Sartorius), and loaded on a 20 ml DEAE FF column equilibrated with IECA buffer (GE healthcare). Proteins were eluted by applying a 0 to 40% gradient of 1 M NaCl by using IECB buffer (50 mM Tris/HCl pH 8, 2 mM DTT, 1 M NaCl), over 150 min at a flow rate of 2 ml/min collecting 4 ml fractions. MtoA and MtoB containing fractions were pooled based on sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS PAGE) profile. MtoA eluted between 130 and 171 mM NaCl and MtoB between 171 and 200 mM NaCl. Those two pools were diluted 4-fold with HICB (25 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6, 2 mM DTT, and 2 M (NH4)2SO4), filtered through 0.2 μm filters, and loaded on a 5 ml Phenyl sepharose HP column, separately (GE healthcare). Proteins were eluted by applying a 60 to 0% gradient of 2 M (NH4)2SO4 by using HICA buffer (HICA: 25 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6, 2 mM DTT) over 60 min at a flow of 1 ml/min collecting 2 ml fractions. MtoA eluted in the range of 1.13 and 0.74 M (NH4)2SO4 and MtoB eluted in the range of 0.45 and 0.10 M (NH4)2SO4. Pooled fractions were diluted 4-fold with HICB, filtered through 0.2 μm filters, and loaded on a Source 15 Phe 4.6/100 PE column (GE healthcare), separately. Proteins were eluted by applying a 70 to 0% gradient of 2 M (NH4)2SO4 by using HICA buffer over 60 min with a flow rate of 1 ml/min collecting 2 ml fractions. Under these conditions MtoA eluted in the range of 1.44 and 1.18 M (NH4)2SO4 and MtoB eluted in the range of 1.27 and 1.09 M (NH4)2SO4. Buffer was exchanged to storage buffer (25 mM Tris/HCl pH 7.6, 10% v/v glycerol, and 2 mM DTT) by a 100–fold dilution using a 15 ml Millipore Ultra-10 centrifugal filter units (Merck; 10 kDa cut-off). Protein concentration was measured by Bradford Protein Assay (Bio-Rad) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

MtoA and MtoB were identified with help of matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) which was performed as explained in the following. Protein bands were cut into small pieces (about 3 × 3 mm) and transferred into an Eppendorf tube. For destaining of the gel pieces, the following solvents/buffers were added successively: 20 µl acetonitrile, 20 µl 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate (ABC) buffer, 50% acetonitrile in ABC buffer and 20 µl acetonitrile. After each addition, samples were swirled and incubated for 10 min at room temperature followed by removing the liquid from the sample. Those steps were repeated, starting from the addition of ABC buffer, until the gel pieces were completely destained. For reduction and alkylation, samples were incubated in 20 µl 10 mM dithiothreitol at 56 °C for 30 min and after removing the liquid from the samples the following solvents/buffers were added successively: 20 µl acetonitrile, 20 µl 50 mM 2-chloroacetamide in 50 mM ABC buffer, 20 µl acetonitrile, 20 µl ABC buffer, 20 µl acetonitrile and 20 µl ABC buffer. After each addition, samples were swirled and incubated for 10 min at room temperature followed by removing the liquid from the sample. For trypsin digestion, 10 µl of 5 ng/µl trypsin in ABC buffer were added to the gel pieces followed by 30 min incubation at room temperature. Afterwards 20 µl ABC buffer were added and the samples were incubated over-night at 37 °C. The samples were sonicated for 20 s in a Branson 2510 sonication bath (Branson, U.S.). Twenty microliters of 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid were added. The samples were swirled and incubated for 20 min at room temperature before the extract liquid was transferred to a new tube. Twenty microliters of acetonitrile were added to the remaining trypsin digest, the samples were swirled and incubated for 30 min at room temperature before the extract liquid was combined with the extract liquid from before. The samples were then dried in a Sanvant ISS110 speedVac (Thermo Scientific) until ~5 µl remain. 0.5 µl of the extracted peptides was pipetted on a MALDI-TOF sample plate and directly mixed with an equal volume of matrix solution containing 10 mg/ml α-cyano-4-hydroxy-α-cyanocinnamic acid in 50% acetonitrile/0.05% trifluoroacetic acid. After drying of the sample this process was repeated once more. A spectrum in the range of 600–3000 m/z was recorded using a Microflex LRF MALDI-TOF (Bruker). The Biotools software (Bruker Life Sciences) was used to perform a MASCOT search (Matrix Science Ltd, London, UK) by using the M. shengliensis protein database (GenBank accession number NZ_JONQ00000000.1). Search parameters allowed a mass deviation of 0.3 Da, one miscleavage, a variable modification of oxidized methionines and a fixed modification of carbamidomethylated cysteines. For MtoA the molecular weight search (MOWSE) score was 115 and the coverage 41% and for MtoB the MOWSE score was 70 and the coverage 34%.

Heterologous protein production of MtoC and MtoD

The gene encoding the corrinoid protein MtoC (BP07_RS03260) and the corrinoid activating enzyme (BP07_RS03235) were amplified from genomic M. shengliensis DNA with primers 3235fw/3235Srev (CTCATATGAGCGTCAGAGTAACGTTCGAGC, CTGCGGCCGCTTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAGCTAGCTGAAGAGAGTTTTTCTCC) and 3260fw/3260Srev (CTCATATGACGGACGTAAGAGAAGAGCTC/CTGCGGCCGCTTATTTTTCGAACTGCGGGTGGCTCCAGCTAGCCTCCACCCCCACCAGAGC) for cloning in expression vector pET-30a inserting an N-terminal Strep tag via the reverse primer. For cloning of the above mentioned genes into pET-30a (Novagen), primers included NdeI and NotI restriction sites to insert the digested PCR products into the plasmid. PCR was performed with Phusion polymerase (NEB) according to manufacturer’s instructions. For restriction, digest fast digest enzymes (Thermo) were used and for ligation T4-DNA ligase (Promega). E. coli DH5α (NEB) was used for plasmid transformation.

For production of the corrinoid protein MtoC (BP07_RS03260) and the corrinoid activating enzyme (BP07_RS03235) the plasmids pET-30a_BP07_RS03260 and pET-30a_BP07_RS03235 were used for transformation into E. coli Bl21 (DE3). For protein overexpression, one colony was inoculated in 600 ml LB-medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and incubated at 37 °C and 180 rpm for 16 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (15,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C). All further steps were performed anaerobically in an anaerobic hood with anoxic buffers and solutions. Pelleted cells were resuspended in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer pH 8 containing 150 mM NaCl and lysed by sonication (1 s pulse, 5 s pause, 40% amplitude; 5 min). After removal of insoluble cell material by centrifugation (20,000 × g for 25 min at 4 °C) proteins were purified by Strep-Tactin XT high capacity affinity chromatography according to the manufacturer’s instructions (IBA, Göttingen, Germany). For assessment of purity, sodium dodecyl sulfate-poly-acrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) was performed.

The protocol for reconstitution of MtoC with cobalamin was adapted from Schilhabel et al. [28]. 1.5 ml (40 mg) anaerobic protein solution was added to 65 ml refolding solution and 650 µl 1 M DTT in a 120 ml glass bottle with a stirrer bar, closed with a rubber stopper (all solutions were made anaerobic by sparging 10 min with nitrogen gas). The refolding solution contained 50 mM Tris, 3.5 M betaine HCl and 1 mM hydroxocobalamin HCl, and pH was adjusted to 7.5. The protein solution then was incubated for 16 h at 4 °C in the dark during slight stirring. Afterwards the buffer was exchanged by Tris HCl pH 7.5 and 1 mM DTT by use of 5 kDa concentration units (Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugal Filter Units, Merck) several times, until the cobalt containing permeate appeared visibly clear instead of red. Protein was stored anaerobically in 2 ml glass vials closed with air-tight rubber stoppers.

Enzyme activity assays

Enzyme activity assays were performed in anaerobic 400 µl Quartz cuvettes (number 115-10-40, Hellma) which were closed with a rubber stopper and gassed with N2. Cuvettes were heated up to 60 °C before starting the measurements. All measurements were at least performed in triplicates. Anoxic buffers and solutions were added with gas-tight glass syringes (Hamilton, Reno, NE). MtoB activity was determined in a total volume of 300 µl containing a 35 mM Tris HCl, 70 mM KCl, pH 7.5 buffer. Firstly, reconstituted Co(II)-MtoC at 1.2 mg/ml final concentration (about 55 µM) was activated by adding 12 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM Ti(III)citrate (freshly prepared), 2.3 mM ATP and 0.08 mg/ml MtoD. The conversion to Co(I)-MtoC was followed by the change in absorbance at 387 nm on a Cary 60 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, USA) (∆ε386 = 21 mM−1 cm−1 [29] was used for our calculations). The reaction was started by the addition of 2.3 mM 2-methoxybenzoate or TMB and MtoB at a final concentration of 0.015 mg/ml. Fifty microliters of sample were removed before addition of MtoB and after the activity assay for analysis of methoxy compounds by HPLC (see below). Formation of CH3-Co(III)-MtoC from Co(I)-MtoC results in a decrease in absorption at 387 nm which was followed with a Cary 60 UV–Vis spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies, USA). Activity was at least measured in triplicates per substrate. As negative control 2.3 mM methanol or trimethylamine were used.

MtoA activity was determined in a total volume of 300 µl containing a 35 mM Tris/HCl, 70 mM KCl, pH 7.5 buffer. Reconstituted Co(II)-MtoC at 0.4 mg/ml final concentration was activated by adding 0.5 mM Ti(III)citrate (freshly prepared), 2.3 mM ATP and 0.08 mg/ml MtoD. Afterwards 2.3 mM 2-methoxybenzoate and 0.4 mg/ml MtoB were added. As potential methyl group acceptor either 0.8 mM H4F (Schircks Laboratories, Switzerland) or 1.7 mM CoM were used. The activity assay was started by addition of 0.03 mg/ml MtoA. Formation of Co(I)-MtoC from CH3-Co(III)-MtoC results in a decrease in absorption at 520 nm which was followed with the UV–vis-spectrophotometer.

For illustration of the whole O-demethylation/methyl transfer process, UV–vis spectra were recorded from 250–650 nm under the latter described conditions after the sequential addition of MtoC, MtoD plus Ti(III) citrate plus ATP, 2-methoxybenzoate plus MtoB, H4F and MtoA.

To measure concentrations of 2-methoxybenzoate and TMB by HPLC an Agilent 1100 HPLC system equipped with a diode array detector (detecting wavelength 230 nm) and a Merck C-18e column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm particle size) was used. The flow rate was 0.75 ml/min and a linear gradient was applied: 75% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA; 0.1% in water), 25% acetonitrile to 50% TFA (0.1% in water), 50% acetonitrile in 15 min. Solutions of TMB, 3-OH-4,5-dimethoxybenzoate, 4-OH-3,5-dimethoxybenzoate, 2-methoxybenzoate and 2-hydroxybenzoate in water (0.1 mg/ml) were used as standards. Twenty microliters of sample was used for injection.

Thermodynamics analyses

Gibbs free energy yield (∆G) was calculated assuming a temperature of 60 °C, pH of 7, CO2(g) of 0.2 bar, CH4(g) of 0.2 bar, 1 mM NH4+, and 10 mM for all other compounds. Temperature adjustments were made as described previously [30]. For methoxylated compounds (2-methoxybenzoate and 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoate), Gibbs free energy of formation (∆Gf) and enthalpy of formation (∆Hf) were first estimated for the acid form using the Joback group contribution method [31]. After calculating the ∆Gf at 60 °C using the Van’t Hoff equation, the ∆Gf of the carboxylate forms at 60 °C were then calculated using pKa estimated by ChemAxon Marvin (https://chemaxon.com/products/marvin). The ∆Hf of the carboxylate forms were estimated using ∆Gf at 25 and 60 °C and the Van’t Hoff equation. The ∆G for methyl transfer from 2-methoxybenzoate, methanol, and methylamine to tetrahydromethanopterin or coenzyme M was calculated by subtracting the ∆G of individual reactions in the methanogenesis pathway from the net reaction. ∆G for most steps were available from the literature [32–37]. For methylene-tetrahydromethanopterin reduction with F420H2, the ∆G was estimated by adding the values for F420H2 reduction of H+ [38] and H2-driven reduction of methylene-tetrahydromethanopterin [39]. Using these ∆G values, reduction potentials of −143, −385, and −520 mV for coenzyme M/B disulfide, F420 and ferredoxin respectively [38, 40, 41], ATP hydrolysis ∆G of −60 kJ mol−1, transmembrane H+ and Na+ transport ∆G of −20 kJ mol−1, limit (quasi-equilibrium) metabolite concentrations were calculated as described by González-Cabaleiro et al. [42].

Resting cell experiment with M. shengliensis ZC-1

M. shengliensis ZC-1 cells grown in 50 mL medium (see above) with 10 mM TMB as substrate were harvested under anoxic conditions in the exponential phase and washed with stabilization buffer (2 mM KH2PO4/K2HPO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 400 mM NaCl, 200 mM sucrose, pH 6.8). The cell pellets were resuspended in 40 ml stabilization buffer (see above) and transferred into 120 ml anaerobic glass bottles (OD 0.1). The cultures were incubated for 30 min at 65 °C. Afterwards, TMB was added to a final concentration of 10 mM and the cultures were incubated for 6 h at 65 °C. The CH4 and CO2 gas produced by the cultures was analyzed every hour by injecting 50 μL headspace volume with a gas-tight glass syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NE) into an Agilent 6890 series gas chromatograph coupled to a mass spectrometer (GC-MS) (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a Porapak Q column heated at 80 °C. For calculating the percentage of CH4 and CO2 in the culture headspace a calibration curve was generated by injecting different volumes of calibration gas (Linde Gas Benelux) that contained 1% CO2 and 1% CH4 into the GC-MS. The CO2 values (in %) were corrected for the CO2 in the medium in form of HCO3− by measuring the headspace CO2 in 40 ml buffer before and after acidification with HCl. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

[13C] labeled bicarbonate experiment

M. shengliensis ZC-1 cells were incubated in 50 mL medium (see above; instead of [12C] bicarbonate, [13C] bicarbonate was used) with 10 mM TMB or 75 mM MeOH as substrate at 65 °C in quadruplicates. This experiment has to be interpreted in a qualitative and not a quantitative way as not all of the CO2 present in the cultures is [13C] CO2. The medium was sparged with N2:CO2 (80:20) and the CO2 in the gas was not [13C] labeled. The carbonate buffering system is required for growth of those cultures. The [12C]- and [13C]-CH4 and CO2 gas produced by the cultures was analyzed every day for a period of 7 days by injecting 50 μL headspace volume into a GC-MS (see above). The ratio of [12C] and [13C] CH4 was calculated for all cultures to different time points (day 4 to 7). The 1% [13C]-CH4 naturally present in CH4 was subtracted from the [13C]-CH4 values.

Results and discussion

Genomic analysis

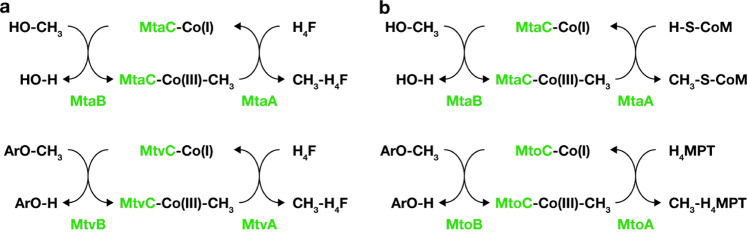

Anaerobic degradation of methyl compounds in both Archaea and Bacteria begins with the transfer of the methyl group to a physiological C1 carrier. In both systems, a substrate-specific methyltransferase (MT1; Eq. 1) transfers the methyl group to a corrinoid protein (CP) and another methyltransferase (MT2 Eq. 2) performs a subsequent transfer to a physiological C1 carrier—coenzyme M (CoM) for Archaea and tetrahydrofolate (H4F) for Bacteria [14, 43]. Both require two methyltransferases, one CP, and an activating enzyme to recycle adventitiously oxidized CPs [44, 45].

| 1 |

| 2 |

Y = CoM or H4F

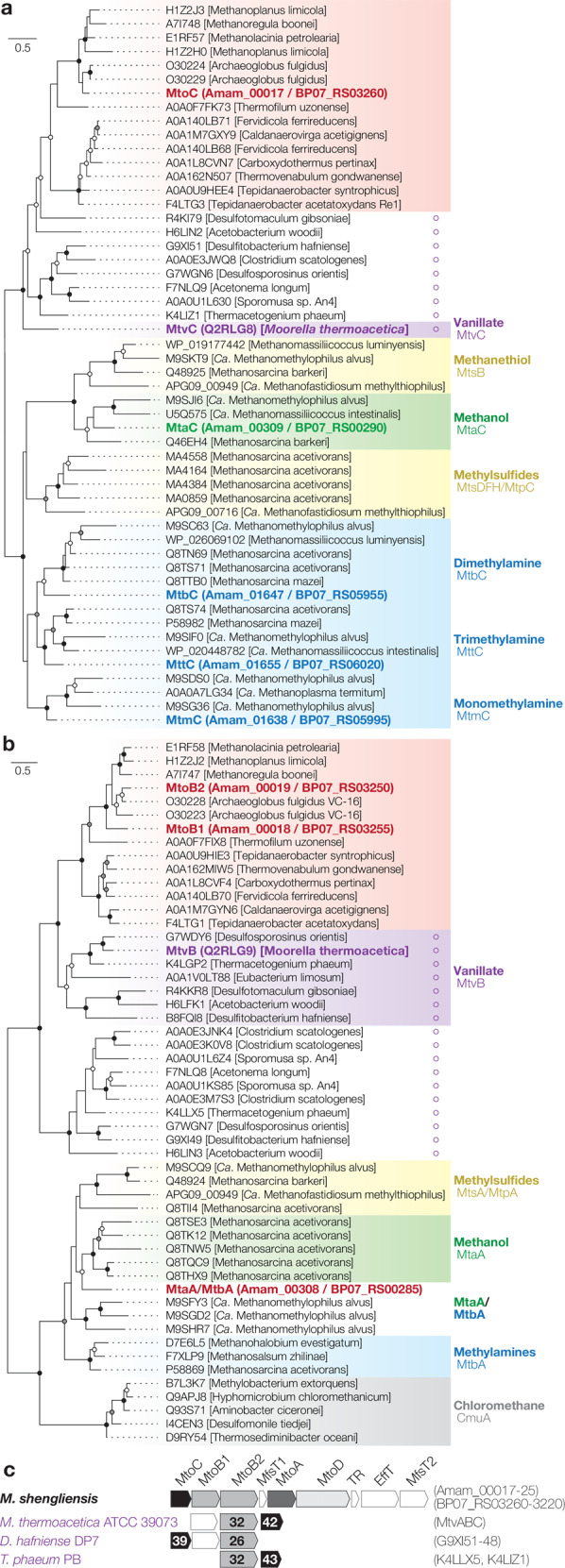

M. shengliensis can metabolize MeOH and mono-, di-, and tri-methylamines and encodes the necessary substrate-specific CPs, MT1s, and MT2s (Fig. 1a, b; Supplementary Table S1). However, with help of an extensive genome analysis we identified an operon in the M. shengliensis AmaM and ZC-1 genomes encoding a putative methyltransferase complex of unknown specificity that has previously been overlooked. This operon includes a CP (Amam_00017; BP07_RS03260), three methyltransferases (Amam_00018, Amam_00019, and Amam_00021; BP07_03250, BP07_03255, and BP07_RS03240), and a corrinoid activator protein (Amam_00022; BP07_RS03235) distantly related to known methanogen methyltransferase components (Fig. 1a–c, and Supplementary Fig. S1).

Fig. 1. M. shengliensis AmaM and ZC-1 corrinoid protein and methyltransferase phylogeny.

a A phylogenetic tree of AmaM methyltransferase corrinoid proteins (red and bolded) and homologs were generated through sequenced alignment via MAFFT v7.394 and tree calculation via RAxML-NG v0.5.1b. The homologs include those specific to vanillate (MtvC; purple), MeOH (e.g., MtaC; green), methylated thiols (e.g., MtsB; yellow), and methylamines (e.g., MtmC; blue). For methyltransferase corrinoid proteins fused with their partner methyltransferase, only the cobalamin-binding region was extracted for this alignment. In addition, a novel cluster of bacterial methyltransferases is shown, including those from ArOCH3-metabolizing anaerobes (indicated with purple circles). Bootstrap values are shown for 200 iterations (>90% black, >70% gray, >50% white). b Phylogenetic tree of MtaA/CmuA family (TIGR01463, cd03307, and IPR006360) and MtvB-related methyltransferases, including those from M. shengliensis (red and bolded) and M. thermoacetica (purple and bolded). MT2 for MeOH (e.g., MtaA; green), methylamine (e.g., MtbA; blue), and MeOH/methylamine bifunctionally; bifunctional MT1/MT2 for methylated thiols (e.g., MtsA; yellow); and MT1 for chloromethane (gray) are shown. Methyltransferases affiliated with ArOCH3-metabolizing anaerobes (purple circles) form a novel cluster. c The operon encoding the novel corrinoid protein (MtoC) with methyltransferases (MtoB1, MtoB2, and MtoA) and corrinoid protein activase (MtoD) along with potential aromatic compound transporters (MfsT MFS transporter, EffT Efflux transporter) and a transcriptional regulator (TR). Operons identified in bacterial ArOCH3 metabolizers are also shown with amino acid sequence percent identity with MtoC and MtoB2.

Although an archaeal O-demethylase/methyltransferase system for methoxylated aromatic compounds has not been described previously, some genes identified in this study and mentioned above show homology with counterparts in the bacterial Mtv O-demethylation system present in the homoacetogenic bacterium Moorella thermoacetica (Pierce et al. [60]; Fig. 1a, b; Supplementary Table S1). Amam_00017 (BP07_RS03260) and Amam_00018/19 (BP07_RS03255/50) are closely related to the CP (MtvC) and vanillate-specific MT1 (MtvB) of the three-component Moorella thermoacetica vanillate O-demethylase system MtvABC [46], indicating involvement of the operon in ArOCH3 demethylation. We also found Amam_00017, 18, and 19 homologs in the genomes of other ArOCH3-catabolizing bacterial anaerobes whose methyltransferases have yet to be identified (Fig. 1c) [47–51]. Based on phylogenetic comparison of the archaeal and bacterial systems, Archaea likely acquired the O-demethylase (MtvB) and corresponding CP (MtvC) for methoxylated aromatic compound metabolism through horizontal gene transfer from Bacteria (Fig. 1a, b). The genes putatively involved in methoxydotrophic growth are also present in other archaea like Archaeoglobus fulgidus and the hydrogenotrophic methanogens Methanolacinia petrolearia and Methanothermobacter tenebrarum (Fig. 1a, b), indicating that the trait for methoxydotrophic growth might be more prevalent among archaea than previously thought.

As the above methyltransferases and CP are cytosolic, M. shengliensis requires transporters for the uptake of methoxylated aromatic compounds. Although specific transporters for aromatic compounds have not been found for methanogens, previous studies have characterized several bacterial aromatic acid:H+ symporters belonging to the major facilitator superfamily (MFS) [52]. This includes PcaK from Pseudomonas putida [53], TfdK from Ralstonia eutropha [54], BenK, VanK, PcaK, and MucK from Acinetobacter sp. ADP1 [55–57] and MhpT from Escherichia coli [58]. We also identified genes encoding MFS transporters adjacent to the aforementioned methyltransferases (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table S1) and suspect that they drive aromatic compound transport for M. shengliensis.

Novel demethoxylation pathway involves methyl transfer to tetrahydromethanopterin

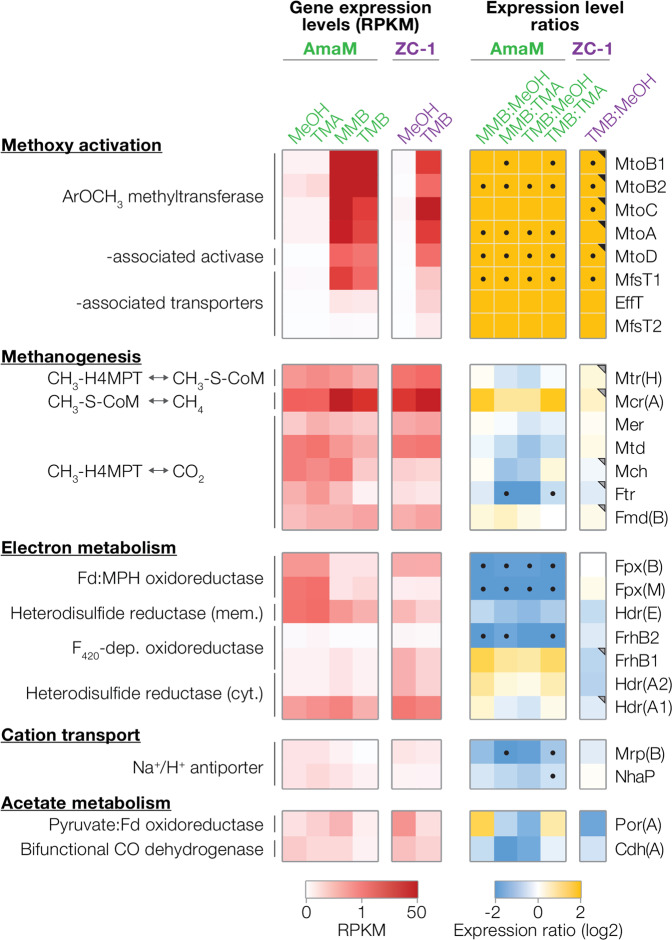

To verify involvement of the aforementioned gene cluster in ArOCH3 metabolism, we compared AmaM transcriptomes during methanogenesis from ArOCH3 (i.e., p-methoxy-benzoate [MB] and 3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoate [TMB]) and methyl compounds (i.e., MeOH and trimethylamine) as well as the ZC-1 transcriptomes and proteomes of ArOCH3 (i.e., TMB)—and cells grown on methyl compounds (i.e., MeOH). For AmaM, the MtvB-related methyltransferase MtoB2, another methyltransferase designated MtoA, reductive activase MtoD, and an MFS transporter MfsT1 were consistently strongly upregulated during growth on methoxylated aromatic compounds (p value < 0.05; Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Similarly, ZC-1 upregulated MtoB1, MtoB2, CP MtoC, reductive activase MtoD, and MfsT1 in the transcriptomes and or proteomes (p value < 0.05; Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1). The novel M. shengliensis methyltransferase genes displayed one of the highest increases in expression among all genes (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table S1), up to 90-fold. We propose that Amam_00017~22/BP07_RS03235~60 collectively function as a novel ArOCH3-specific O-demethylase/methyltransferase system, tentatively termed the Mto system based on the nomenclature used by Sauer and Thauer for methanogenic methyltransferases [59], and the adjacent transporters as ArOCH3 uptake or byproduct aromatic compound efflux proteins. We further propose that Amam_00018/BP07_RS03255 and Amam_00019/BP07_RS03250 function as ArOCH3-specific MT1 (MtoB1 and MtoB2 respectively) and Amam_00017/BP07_RS03260 as the corresponding methyl-carrying CP (MtoC), based on the aforementioned similarity with Moorella thermoacetica MtvB and MtvC (Fig. 1). Together, MtoB(1/2) and MtoC likely accomplish the first step in ArOCH3 O-demethylation (Eq. 3).

| 3 |

Fig. 2. Comparison of gene expression during growth on methylated and methoxylated substrates.

(left) Gene expression of the novel AmaM/ZC-1 corrinoid protein and methyltransferase operon, methanogenesis pathways, and electron transduction (see Supplementary Table S1 for abbreviations). RPKM (reads per kilobase transcript per million mapped reads) values are normalized to the average ribosomal protein RPKM under methanogenesis from MeOH, trimethylamine (TMA), 2-methoxybenzoate (MB), and trimethyoxybenzoate (TMB). (right) The ratios of gene expression between ArOCH3- and methylated compound-fed conditions are shown (p value < 0.05 marked with dot). For ZC-1, dots are shown if at least two TMB-grown cultures show significantly different RNA expression levels (p value < 0.05) from the MeOH-grown cultures (see Supplementary Table S1). Similarly, triangles are shown if significant differences in protein expression levels were observed (p value < 0.05). For entries spanning multiple genes, expression levels of specific subunits are shown as indicated on the right-hand side.

As described before, M. shengliensis can use a broad range of different methoxylated aromatics for growth [6]. The O-demethylase proteins MtoB1 (Amam_00018/BP07_RS03255; 48 kDa) and MtoB2 (Amam_00019/BP07_RS03250; 47 kDa) have a sequence similarity of 57% to each other (NCBI BLASTp). This dissimilarity might hint towards different substrate affinities of the two proteins. In the first step of methoxydotrophic methanogenesis, through O-demethylation via the MtoB proteins, the methyl group is most likely transferred to the cobalt containing CP MtoC (22 kDa; N-terminal Coenzyme B12 binding site [Prosite: https://prosite.expasy.org]). MtoD (Amam_00019/BP07_RS03235; 68 kDa) is predicted to perform activation of the CP, a process necessary for catalytic activity of the CP in both acetogens and methanogens. This corrinoid activation protein MtoD harbors an N-terminal 2Fe-2S binding site (Prosite: https://prosite.expasy.org), a feature more similar to those of acetogens than methanogens (two C-terminal 4Fe-4S clusters) [28].

The next step is methyl transfer from CH3-MtoC to a physiological C1 carrier by a methyl transferase (MT2). In methylotrophic methanogens, the methyl group is transferred from the CP to CoM via the methyl transferase MtaA when grown on methanol (Fig. 3). In the acetogen Moorella thermoacetica the methyl transferase MtvA transports the methyl group from the CP to H4F [46]. M. shengliensis does not encode an mtvA-like gene and mtaA is neither upregulated under growth on methoxylated compounds nor part of the identified methoxydotrophy gene cluster. Instead, an mtrH-like gene (Amam_00021/BP07_RS03240) is part of the aforementioned operon and is highly upregulated under methoxydotrophic growth in M. shengliensis. This gene is not homologous to any known MT2 and rather relates to methyltransferase family PF02007: methyl-tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT):CoM methyltransferase (Mtr) subunit H (MtrH; 41% peptide similarity to that of Methanosarcina barkeri) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Although MtrH (subgroup I) is part of the membrane-bound Mtr complex found in methanogens, the identified M. shengliensis MtrH homolog Amam_00021/BP07_RS03240 relates more to MtrH-related proteins (e.g., subgroup III) that do not form such a complex and are found in non-methanogenic archaea (e.g., Archaeoglobus fulgidus) and methylotrophic bacteria Desulfitobacterium hafniense or Acetobacterium woodii [61] (i.e., organisms that neither synthesize nor utilize CoM). MtrH in Desulfitobacterium hafniense has been described as a methylcorrinoid:tetrahydrofolate methyltransferase [62]. As Amam_00021/BP07_RS03240 is upregulated together with the neighboring MtoC, MtoB1, and MtoB2 during ArOCH3 metabolism, we hypothesize that the gene product serves as an CH3-(CoIII)-MtoC:H4MPT methyltransferase (Eq. 4), tentatively named MtoA. Together MtoAB(1/2)C might catalyze complete methyl transfer from ArOCH3 to H4MPT (Eq. 5) and MtoD is a corresponding corrinoid activation protein required for sustained methyltransferase activity (Eq. 6):

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

Fig. 3. Demethylation and demethoxylation pathways in acetogenic bacteria and methanogenic archaea.

a Demethylation and demethoxylation pathways as described for the acetogenic bacterium Moorella thermoacetica, modified from Pierce et al. [60]. b Demethylation and tentative demethoxylation pathways in methanogenic archaea. Co(I/III): oxidation state of the cobalamin carried by the cobalamin binding protein MtoC, H4MPT: tetrahydromethanopterin.

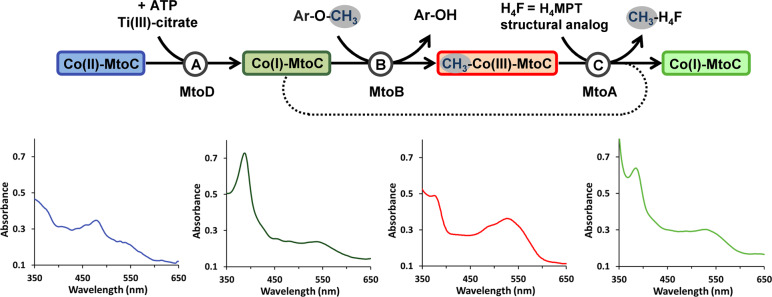

To verify the function of the Mto proteins from M. shengliensis in O-demethylation and methyl transfer, we purified the Mto proteins and analyzed them by UV–vis spectroscopy and enzyme activity assays (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. S2).

Fig. 4. O-demethylation and methyl transfer conducted by Mto proteins.

Reaction A: MtoD, ATP and titanium (III) citrate are required for activation of MtoC from the Co(II) state (blue) to the active Co(I) state (dark green). Reaction B: MtoB transfers the methyl group of the methoxy compound (Ar-O-CH3) to Co(I)-MtoC resulting in methylated Co(III)-MtoC (red). The MtoB activities with 2-methoxybenzoate (MB) and TMB are shown in Fig. S2A. With methanol or trimethylamine as substrate no activity could be observed. Conversion of TMB to 3-OH-4,5-dimethoxybenzoate was confirmed by HPLC (Fig. S3). Reaction C: For measuring MtoA activity, the H4MPT structural analog H4F was used. We got strong evidence that MtoA transfers the methyl group from methylated Co(III)-MtoC (red) to H4F thereby producing Co(I)-MtoC (light green). The activity is shown in Fig. S2B. In M. shengliensis H4MPT and not H4F is most likely the methyl group acceptor as M. shengliensis does not have the genomic capacity to synthesize H4F. Also, the methyl-transfer reaction is not occurring if CoM is used instead of H4F (Fig. S2B). All bottom panels correspond to UV/visible spectra measured after each reaction reflecting the different states of the cobalamin carried by MtoC.

MtoC exhibits different UV–vis spectroscopic features depending on the oxidation state of its cobalamin cofactor. In the inactive Co(II) state, the UV–vis spectrum shows a peak at around 480 nm (Fig. 4, before reaction A). The corrinoid activator MtoD can reactivate the Co(II) state of MtoC by reducing the cobalamin to the active Co(I) state with the use of ATP and titanium (III) citrate (Fig. 4, reaction A). The active Co(I) state exhibits a peak at around 390 nm (gamma band). When MtoB and the methoxylated aromatic compound are added to the enzyme assay mixture the methyl group is transferred to the cobalamin (Fig. 4, reaction B), as also shown by HPLC (Supplementary Fig. S3). The formation of methyl-Co(III) provokes the disappearance of the peak at 390 nm and the appearance of a new peak at 520 nm. The demethylation of MtoC by MtoA was observed when tetrahydrofolate (H4F), a C1-carrier analogous to H4MPT, was added (Fig. 4, reaction C). This reaction can be followed by the decrease of absorbance at 520 nm and the increase of absorbance at 390 nm, which is explained by a switch back to the Co(I) state. As H4F instead of the native methyl acceptor H4MPT is used in the assay no specific activity value for MtoA could be accurately determined. By HPLC analysis of the methoxy compounds and their hydroxylated derivatives we observed that roughly 2.2% of the methoxy compound is converted (i.e., about 51 µM of the initial 2.3 mM TMB; Supplementary Fig. S3), which agrees with the concentration of the methyl-acceptor MtoC in the assay mixture (~55 µM). The MtoB activity with 2-methoxybenzoate (MB) was found to be 0.87 ± 0.04 µmol Co(III) formed per min and per mg of MtoB and with TMB 0.76 ± 0.04 µmol of Co(III) formed per min and per mg of MtoB (see also Supplementary Fig. S2A). The specific activity values of the O-demethylase of Acetobacterium dehalogenans measured with vanillate and isovanillate are 0.43 and 0.65 µmol Co(III) formed per min and per mg MT1 respectively, for example [28].

With those experiments we showed that the O-demethylation and methyl transfer reaction are indeed catalyzed by the Mto proteins and that this system works in a similar way as shown for methoxydotrophic bacteria such as Moorella thermoacetica [46] or A. dehalogenans [28]. We could identify MtoB (WP_042685515.1) as the O-demethylase catalysing the methyl transfer from the methoxy compound to Co(I)-MtoC. After accepting the methyl group from MtoB, MtoC could not be demethylated by MtoA in the presence of HS-CoM, the conventional methyl-acceptor for methylotrophic methanogenenesis. On the other hand, MtoC demethylation by MtoA could be observed when the H4MPT structural analog H4F was present. Given that M. shengliensis can only synthesize H4MPT and not H4F (e.g., absence of bacterial dihydrofolate reductase), this gives us strong evidence that H4MPT, rather than HS-CoM, should accept the methyl group from CH3-Co(III)-MtoC in M. shengliensis.

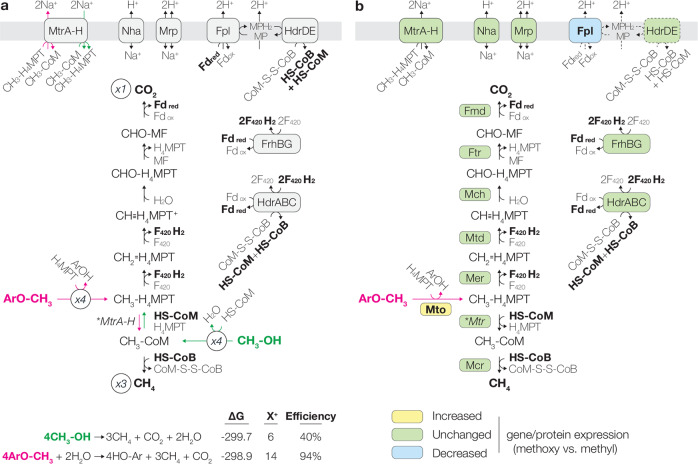

Such a H4MPT-dependent methyl transfer would be the first of its kind though, in some aspects, comparable to other pterin-dependent methyl activation pathways—H4MPT/H4F-dependent acetyl-CoA decarbonylation and H4F-dependent acetogenic methyl transfer pathway [63]. If the Methermicoccus methyltransferase system is indeed dependent on the archaeal equivalent of H4F, this may be because the archaeal ability to degrade methoxylated aromatic compounds likely originated in C1-metabolizing Firmicutes, based on the topology of the MtoB and MtoC phylogenetic trees (Fig. 1a, b). The proposed transfer of the ArOCH3-derived methyl group to H4MPT rather than CoM would significantly influence the energetics of methanogenesis. Based on thermodynamic calculations we suggest the following hypotheses regarding the energy metabolism of methoxydotrophic methanogens: typical methylotrophic methanogenesis disproportionates CH3-S-CoM to ¼ CO2 and ¾ CH4. In this pathway (4CH3X + 2H2O → CO2 + 3CH4 + 4HX), CH3-S-CoM oxidation to CO2 requires an energy input (~2Na+ transported in for transferring the methyl group from CoM to H4MPT; Fig. 5) but electron transfer from this oxidation to reduction of CH3-S-CoM to CH4 allows energy recovery (~8H+ transported out, assuming all F420H2 is re-oxidized via Fpo-related Fd:methanophenazine (Mp) oxidoreductase (Fpl); Fig. 5). Assuming each H+/Na+ transported across the membrane stores 20 kJ per mol, this yields a net energy gain of 120 kJ per four mol methyl substrate. If methoxydotrophic methanogenesis follows an analogous pathway with an entry point at CH3-H4MPT (CH3-H4MPT disproportionation to ¼ CO2 and ¾ CH4), oxidation of CH3-H4MPT to CO2 would not incur any energetic cost, while reduction of CH3-H4MPT to CH4 would generate energy (~6Na+ transported out; Fig. 5). Combined with the energy gain from electron transfer (~8H+ transported out), such metabolism would yield a net energy gain of 280 kJ per four mol methoxylated substrate. Based on such energetics, M. shengliensis methylotrophic and methoxydotrophic methanogenesis would, in theory, respectively reach roughly 40% and 94% thermodynamic efficiency (e.g., 40.0, 41.2, and 93.7% for MeOH [−299.7 kJ], monomethylamine [−291.0 kJ], and 2-methoxybenzoate [−298.9 kJ] correspondingly at 60 °C, pH 7, 0.2 atm CO2, 0.2 atm CH4, 1 mM NH4+, and 10 mM for all other compounds; see also Supplementary Table S3). However, most anaerobes work at efficiencies around 25–50% and efficiencies above 80% are highly improbable [64], suggesting that methoxydotrophic methanogenesis through such a pathway would be impossible. To operate at an energetic efficiency that organisms can physicochemically achieve, methoxydotrophic methanogenesis most likely takes an alternative route that recovers a lesser amount of energy. As an analogous phenomenon of trading off energy yield for thermodynamic driving force, one can look at glycolysis—compared to the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas pathway, the Entner-Douduroff pathway sacrifices half of the ATP yield partly to minimize thermodynamic bottlenecks and prioritize thermodynamic feasibility [65, 66]

Fig. 5. Comparison of CH3-CoM- and hypothetical CH3-H4MPT-disproportionating methanogenesis based on (a) energetics and (b) expression.

a Reactions and reaction directions unique to MeOH (green) or 2-methoxybenzoate (pink) decomposition are shown. Below are the estimated Gibbs free energy (∆G) and the predicted energy yield (in terms of H+/Na+ extruded across the membrane, assuming the typical scheme of methylotrophic methanogenesis is followed) and thermodynamic efficiency of the shown methanogenesis pathways. ∆G was calculated assuming 60 °C, pH 7, 0.2 atm CO2, 0.2 atm CH4, 1 mM NH4+, and 10 mM for all other compounds. b Comparison of gene/protein expression of M. shengliensis grown on methoxylated aromatic compounds and methylated compounds. Yellow: genes/proteins for which both strains showed significantly increased expression during methoxydotrophic methanogenesis. Green: genes/proteins for which either (i) expression levels were not significantly different for both strains or (ii) consistent trends were not observed in both strains. Blue: genes/proteins for which both strains showed significantly decreased expression during methoxydotrophic methanogenesis. Arrows involving Fpl and HdrDE are dotted as Fpl was downregulated during methoxydotrophic methanogenesis and, with decreased Fpl activity, HdrDE’s activity would consequently decrease as well. H4MPT tetrahydromethanopterin, MF methanofuran.

Supporting the possibility of an alternative route (i.e., not simple disproportionation to CO2 and CH4), we obtained evidence that methylotrophic and methoxydotrophic methanogenesis behave differently metabolically—while nearly all CH4 (96.4%) produced from strain AmaM methylotrophic methanogenesis originated from the methylated substrate (as was also observed for Methanosarcina barkeri [98-99% CH4 from methanol; [67]), CH4 from strain AmaM methoxydotrophic methanogenesis originated from both the methoxylated substrate (2/3) and CO2 (1/3) [6]. We also compared the growth of strain ZC-1 on TMB and MeOH and, in agreement, found that the former consumes more CO2 for methanogenesis: in a qualitative experiment with [13C] bicarbonate we found that ZC-1 cells grown on TMB produced roughly 10 times more [13C]-CH4 from [13C]-bicarbonate-derived CO2 than those grown on MeOH. Thus, both strains seem to display the same atypical behavior when degrading methoxylated compounds. Given that both strains lack genes for any alternative C1 metabolism (e.g., aerobe-like aldehyde-based or anaerobic bacterial H4F-based metabolism), H4MPT-dependent C1 metabolism is presumably responsible for running both CO2 and CH4 generation from ArOCH3 as well as CH4 generation from CO2. In search of a metabolic route that provides a rationale for this anomalous behavior and thermodynamic efficiency, we further compare the gene expression of M. shengliensis when degrading methylated compounds and ArOCH3 to gain insight into how the pathways may differ regarding electron transport and energy recovery.

During methylotrophic growth, AmaM and ZC-1 express the corresponding methyltransferase system and the complete methanogenesis pathway (i.e., CH3-S-CoM disproportionation to CO2 and CH4). To transfer electrons from the oxidative to reductive pathway, the two strains express two putative ferredoxin (Fd)-dependent F420:CoB-S-S-CoM oxidoreductases (HdrA1B1C1 or FrhBG-HdrA2B2C2; Eq. 7) [40], a putative Fpo-related Fd:methanophenazine (Mp) oxidoreductase (FplABCDHIJKLMNO; Eq. 8; see Supplementary Table S1) [68, 69], and a Mp-oxidizing membrane-bound heterodisulfide reductase (HdrDE; Eq. 9).

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

Combined together, these complexes can facilitate complete electron transfer for CH3-S-CoM disproportionation (Eq. 7 + 2x Eq. 8 + 2x Eq. 9; Fig. 5). However, during methoxydotrophic growth, we observe significant decreases in the expression of Fpl compared to methylotrophy (Supplementary Table S1): 3.8–10.1 fold decrease for FplBIMN in AmaM transcriptomes (p < 0.043) and 3.2 fold decrease for FplD in ZC-1 proteomes (p = 0.0027). Although decreases in all Fpl subunits were not observed, the downregulated subunits play critical roles in the activity of the Fpl complex – FplBI and FplD are predicted to mediate Fdred oxidation [68] and interaction with the transmembrane subunits, respectively. Thus, both AmaM and ZC-1 might decrease electron transfer via Fpl and then would have to redirect intracellular electron flow through an alternative pathway. Interestingly, Fpl is central to energy generation from electron transfer (Eqs. 7 and 8), suggesting that M. shengliensis switches to an energy acquisition scheme distinct from that of methylotrophic methanogenesis. In other words, while methylotrophic methanogenesis gains energy purely from electron transfer (F420H2 re-oxidation), methoxydotrophic methanogenesis may forgo such energy metabolism and rather gain energy from methyl transfer (CH3-H4MPT to CH3-S-CoM).

Based on the annotatable genes for methanogenesis and energy metabolism expressed by M. shengliensis, the above electron transfer/energy acquisition scheme cannot accomplish complete electron transfer from CH3-H4MPT oxidation to CH3-H4MPT reduction (Fig. S4; see Supplementary Material “Electron transfer metabolism” including Figs. S5 and S6). There is a possibility that M. shengliensis possesses genes that encode a novel electron transfer metabolism, but, assuming that this is not the case, ArOCH3 disproportionation would result in accumulation of reducing power distributed among multiple electron carriers (e.g., through activity of a ferredoxin:F420 oxidoreductase and HdrABC). Given that methoxydotrophic methanogenesis was observed to reduce CO2 to CH4, switching to CO2-reducing methanogenesis may allow cells to re-oxidize excess reducing power. Based on a thermokinetic model (see Supplementary Material; Fig. S7), cells could potentially passively alternate between oxidative (ArOCH3 disproportionation) and reductive (CO2-reducing methanogenesis) metabolism as the cells respectively approach thermodynamic and kinetic limits through accumulation or consumption of cellular reducing power. Although not found in methanogens yet, such repeated intracellularly triggered reversals in metabolism (“metabolic oscillation” or “intracellular feedback loops”) involving fluctuation of reducing power (i.e., NADH) have been observed in various organisms, including Klebsiella sp. (succinate or glycerol metabolism) [70, 71] and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (glucose) [72]. These oscillations occur on the scale of seconds to hours and concomitantly perform repeated cycles of production and consumption of metabolic end-products (e.g., CO2, H2, ethanol, or acetate) [71, 73] and intermediates (e.g., ATP) [74]. The proposed theoretical oscillation between oxidative CO2-/CH4-liberating CH3-H4MPT disproportionation and CO2-reducing methanogenesis is in line with the predicted need for an alternative electron transfer route (i.e., forgoing energy gain via Fpl and Hdr) and concomitant CO2 generation/consumption during methoxydotrophic methanogenesis, but certainly requires verification.

Conclusion

In this study, we analysed the growth of the demethoxylating methanogen M. shengliensis on methoxylated aromatic compounds and showed that this archaeon uses a demethoxylation system (Mto) similar to those found in acetogenic bacteria. In contrast to the methylotrophic pathway of methanogenic archaea, the methyl group derived from the methoxylated compound is most likely transferred to H4MPT instead of CoM. In theory, such activation would thermodynamically require that methoxydotrophic methanogenesis takes an energy acquisition strategy distinct from that of methylotrophic methanogenesis. This hypothesis can be supported by the finding that, during methoxydotrophy, M. shengliensis downregulates genes involved in energy-generating electron transfer metabolism that is essential for methylotrophy. Clearly, methoxydotrophic methanogenesis exhibits several interesting features that differ from methylotrophic methanogenesis and requires further investigation to verify the biochemistry of methoxylated aromatic compound activation and downstream energy metabolism.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

JMK was supported by the Deutsche Forschungs Gesellschafts (DFG) Grant KU 3768/1-1. MKN, HT, DM, SS, and YK were supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 18H03367, 18H05295, 17H03800/16KK0154/20H00366, 18H02426/26710012, and 17H01363. CUW was supported by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek through Grant ALWOP.293. CUW, JMK, and MSMJ were supported by the Nederlandse Organisatie voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek through the Soehngen Institute of Anaerobic Microbiology Gravitation Grant 024.002.002 and the Netherlands Earth System Science Center Gravitation Grant 024.002.001. MSMJ was supported by the European Research Council Advanced Grant Ecology of Anaerobic Methane Oxidizing Microbes 339880. NdJ and JLN were supported by a grant from Novo Nordisk Foundation (Grant no. NNF16OC0021818). TW was supported by the Max-Planck-Gesellschaft. We thank Theo van Alen, Geert Cremers, Rob de Graaf and Henrik Kjeldal for technical assistance and Huub Op den Camp for helping with MALDI-TOF MS. We also thank Prof. Joseph Krzycki, Ohio State University, for useful discussion on corrinoid protein biochemistry. We thank Ramona Appel and Christina Probian for their technical assistance in the Microbial Metabolism laboratory and the Max Planck Institute for Marine Metabolism for continuous support.

Author contributions

MKN, JMK and CUW conceived and designed the study. JMK carried out all experiments performed with M. shengliensis ZC-1. JMK and MKN performed omics analyses. JMK, MKN, and CUW interpreted the omics data. TW and JMK designed and conducted the protein purification and biochemical characterization. MKN performed metabolic/thermodynamic reconstruction. NdJ performed initial proteomics analysis with guidance of JLN. SB did the initial culturing of M. shengliensis ZC-1. JMK and MKN took lead in writing the manuscript. JMK, MKN, and CUW integrated feedback from all authors into the manuscript. KY and JLN supported experimental work. DM, HT, SS, YK, MSMJ provided critical feedback. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Data availability

The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [75] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD018934. The transcriptomics data have been deposited under GenBank SRR11935466-SRR11935483.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Julia M. Kurth, Masaru K. Nobu

Contributor Information

Masaru K. Nobu, Email: m.nobu@aist.go.jp

Cornelia U. Welte, Email: c.welte@science.ru.nl

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41396-021-01025-6.

References

- 1.Ueno Y, Yamada K, Yoshida N, Maruyama S, Isozaki Y. Evidence from fluid inclusions for microbial methanogenesis in the early Archaean era. Nature. 2006;440:516–9. doi: 10.1038/nature04584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thauer RK, Kaster A-K, Seedorf H, Buckel W, Hedderich R. Methanogenic archaea: ecologically relevant differences in energy conservation. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:579–91. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conrad R. The global methane cycle: recent advances in understanding the microbial processes involved. Environ Microbiol Rep. 2009;1:285–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deppenmeier U, Mueller V, Gottschalk G. Pathways of energy conservation in methanogenic archaea. Arch Microbiol. 1996;165:149–63. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng L, Qiu TL, Yin XB, Wu XL, Hu GQ, Deng Y, et al. Methermicoccus shengliensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a thermophilic, methylotrophc methanogen isolated from oil-production water, and proposal of Methermicoccaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:2964–9. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mayumi D, Mochimaru H, Tamaki H, Yamamoto K, Yoshioka H, Suzuki Y, et al. Methane production from coal by a single methanogen. Science. 2016;354:222–5. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf8821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Leeuw JW, Largeau C. A review of macromolecular organic compounds that comprise living organisms and their role in kerogen, coal, and petroleum formation. Organic Geochem. 1993;11:23–72. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Welte CU. A microbial route from coal to gas. Science. 2016;354:184–184. doi: 10.1126/science.aai8101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Libes SM. The origin of petroleum in the marine environment. Introduction to marine biogeochemistry. Cynar F, Bugeau P, Kelleher L, Versteeg L. editors. Ch. 26. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science, 2009. pp 1–33.

- 10.Meslé M, Dromart G, Oger P. Microbial methanogenesis in subsurface oil and coal. Res Microbiol. 2013;164:959–72. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gruendger F, Jiménez N, Thielemann T, Straaten N, Lueders T, Richnow H-H, et al. Microbial methane formation in deep aquifers of a coal-bearing sedimentary basin, Germany. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:1–17. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krüger M, Beckmann S, Engelen B, Thielemann T, Cramer B, Schippers A, et al. Microbial methane formation from hard coal and timber in an abandoned coal mine. Geomicrobiol J. 2008;25:315–21. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritter D, Vinson D, Barnhart E, Akob DM, Fields MW, Cunningham AB, et al. Enhanced microbial coalbed methane generation: a review of research, commercial activity, and remaining challenges. Int J Coal Geol. 2015;146:28–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferguson DJ, Krzycki JA, Grahame DA. Specific roles of methylcobamide:coenzyme M methyltransferase isozymes in metabolism of methanol and methylamines in Methanosarcina barkeri. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5189–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.9.5189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boutet E, Lieberherr D, Tognolli M, Schneider M, Bairoch A. UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot: the manually annotated section of the UniProt KnowledgeBase. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;406:89–112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katoh K, Standley DM. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:772–80. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kozlov AM, Darriba D, Flouri T, Morel B, Stamatakis A. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 2019;35:4453–5. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. FastTree 2 - Approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, et al. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1236–40. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Petersen TN, Brunak S, Von Heijne G, Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat Methods. 2011;8:785–6. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sekiguchi Y, Kamagata Y, Nakamura K, Ohashi A, Harada H. Syntrophothermus lipocalidus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel thermophilic, syntrophic, fatty-acid-oxidizing anaerobe which utilizes isobutyrate. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:771–9. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-2-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takai K, Horikoshi K, Takai KEN. Rapid detection and quantification of members of the archaeal community by quantitative PCR using fluorogenic probes rapid detection and quantification of members of the archaeal community by quantitative PCR using fluorogenic probes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5066–72. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.11.5066-5072.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schmidt TM, DeLong EF, Pace NR. Analysis of a marine picoplankton community by 16S rRNA gene cloning and sequencing. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4371–8. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.14.4371-4378.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu Y, Smith M, Pieper R. A spinnable and automatable StageTip for high throughput peptide desalting and proteomics. Protoc Exch. 2014; 10.1038/protex.2014.033.

- 26.Tyanova S, Temu T, Cox J. The MaxQuant computational platform for mass spectrometry-based shotgun proteomics. Nat Protoc. 2016;11:2301–19. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2016.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyanova S, Temu T, Sinitcyn P, Carlson A, Hein MY, Geiger T, et al. The Perseus computational platform for comprehensive analysis of (prote)omics data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:731–40. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schilhabel A, Studenik S, Voedischo M, Kreher S, Schlott B, Pierik AY, et al. The ether-cleaving methyltransferase system of the strict anaerobe Acetobacterium dehalogenans: analysis and expression of the encoding genes. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:588–99. doi: 10.1128/JB.01104-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siebert A, Schubert T, Engelmann T, Studenik S, Diekert G. Veratrol-O-demethylase of Acetobacterium dehalogenans: ATP-dependent reduction of the corrinoid protein. Arch Microbiol. 2005;183:378–84. doi: 10.1007/s00203-005-0001-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Preiner M, Igarashi K, Muchowska KB, Yu M, Varma SJ, Kleinermanns K, et al. A hydrogen-dependent geochemical analogue of primordial carbon and energy metabolism. Nat Ecol Evol. 2020;4:534–42. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joback KG, Reid RC. Estimation of pure-component properties from group-contributions. Chem Eng Commun. 1987;57:233–43. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bertram PA, Karrasch M, Schmitz RA, Boecher R, Albracht SPJ, Thauer RK. Formylmethanofuran dehydrogenases from methanogenic archaea. Substrate specificity, EPR properties and reversible inactivation by cyanide of the molybdenum or tungsten iron‐sulfur proteins. Eur J Biochem. 1994;220:477–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thauer RK. Energy metabolism of methanogenic bacteria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1018:256–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Donnelly MI, Escalante-Semerena JC, Rinehart K, Wolfe R. Methenyl-tetrahydromethanopterin cyclohydrolase in cell extracts of Methanobacterium. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1995;242:430–9. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Escalante-Semerena JC, Rinehart KL, Wolfe RS. Tetrahydromethanopterin, a carbon carrier in methanogenesis. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:9447–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daniels L. Biochemistry of methanogenesis. New comprehensive biochemistry. Kates M, Kushner DJ, Matheson AT. editors. Amsterdam: Elsevier: 1993. pp 41–112.

- 37.Gärtner P, Weiss DS, Harms U, Thauer RK. N5‐methyltetrahydromethanopterin:coenzyme M methyltransferase from Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. Catalytic mechanism andsodium ion dependence. Eur J Biochem. 1994;226:465–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20071.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.de Poorter LMI, Geerts WJ, Keltjens JT. Hydrogen concentrations in methane-forming cells probed by the ratios of reduced and oxidized coenzyme F420. Microbiology. 2005;151:1697–705. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27679-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keltjens JT, van der Drift C. Electron transfer reactions in methanogens. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1986;39:259–303. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yan Z, Wang M, Ferry JG. A ferredoxin- and F420H2-dependent, electron-bifurcating, heterodisulfide reductase with homologs in the domains bacteria and archaea. MBio. 2017;8:1–15. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02285-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tietze M, Beuchle A, Lamla I, Orth N, Dehler M, Greiner G, et al. Redox potentials of methanophenazine and CoB-S-S-CoM, factors involved in electron transport in methanogenic archaea. ChemBioChem. 2003;4:333–5. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200390053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.González-Cabaleiro R, Lema JM, Rodriguez J, Kleerebezem R. Linking thermodynamics and kinetics to assess pathway reversibility in anaerobic bioprocesses. Energy Environ Sci. 2013;6:3780–9. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sauer K, Harms U, Thauer RK. Methanol:Coenzyme M methyltransferase from Methanosarcina barkeri purification, properties and encoding genes of the corrinoid protein MT1. Eur J Biochem. 1997;243:670–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1997.t01-1-00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaufmann F, Wohlfarth G, Diekert G. Isolation of O-demethylase, an ether-cleaving enzyme system of the homoacetogenic strain MC. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:136–42. doi: 10.1007/s002030050479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oelgeschläger E, Rother M. Influence of carbon monoxide on metabolite formation in Methanosarcina acetivorans. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;292:254–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Naidu D, Ragsdale SW. Characterization of a three-component vanillate O-demethylase from Moorella thermoacetica. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:3276–81. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.11.3276-3281.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sharak Genthner BR, Bryant MP. Additional characteristics of one-carbon-compound utilization by Eubacterium limosum and Acetobacterium woodii. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:471–6. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.3.471-476.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kane MD, Breznak JA. Acetonema longum gen. nov. sp. nov., an H2/CO2 acetogenic bacterium from the termite, Pterotermes occidentis. Arch Microbiol. 1991;156:91–8. doi: 10.1007/BF00290979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hattori S, Kamagata Y, Hanada S, Shoun H. Thermacetogenium phaeum gen. nov., sp. nov., a strictly anaerobic, thermophilic, syntrophic acetate-oxidizing bacterium. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1601–9. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-4-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kuesel K, Dorsch T, Acker G, Stackebrandt E, Drake HL. Clostridium scatologenes strain SL1 isolated as an acetogenic bacterium from acidic sediments. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:537–46. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-2-537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Studenik S, Vogel M, Diekert G. Characterization of an O-Demethylase of Desulfitobacterium hafniense DCB-2. J Bacteriol. 2012;194:3317–26. doi: 10.1128/JB.00146-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saier MH, Beatty JT, Goffeau A, Harley KT, Heijne WHM, Huang S, et al. The major facilitator superfamily. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;1:257–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nichols NN, Harwood CS. PcaK, a high-affinity permease for the aromatic compounds 4-hydroxybenzoate and protocatechuate from Pseudomonas putida. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5056–61. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.16.5056-5061.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Leveau JHJ, Zehnder AJB, van der Meer JR. The tfdK gene product facilitates uptake of 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetate by Ralstonia eutropha JMP134(pJP4) J Bacteriol. 1998;180:2237–43. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.8.2237-2243.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Collier LS, Nichols NN, Neidle EL. benK encodes a hydrophobic permease-like protein involved in benzoate degradation by Acinetobacter sp. Strain ADP1. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5943–6. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5943-5946.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams PA, Shaw LE. mucK, a gene in Acinetobacter calcoaceticus ADP1 (BD413), encodes the ability to grow onexogenous cis,cis-muconate as the sole carbon source. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5935–42. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.18.5935-5942.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.D’Argenio DA, Segura ANA, Coco WM, Buenz PV, Ornston LN. The physiological contribution of Acinetobacter PcaK, a transport system that acts upon protocatechuate, can be masked by the overlapping specificity of VanK. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:3505–15. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.11.3505-3515.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xu Y, Chen B, Chao H, Zhou N. mhpT encodes an active transporter involved in 3-(3-hydroxyphenyl)propionate catabolism by Escherichia coli K-12. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:6362–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02110-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]