Abstract

A new highly diastereoselective synthesis of the polyhydroxylated pyrrolidine alkaloid (±)-codonopsinol B and its N-nor-methyl analogue, starting from achiral materials, is presented. The strategy relies on the trans-stereoselective epoxidation of 2,3-dihydroisoxazole with in situ-generated DMDO, the syn-selective α-chelation-controlled addition of vinyl-MgBr/CeCl3 to the isoxazolidine-4,5-diol intermediate, and the substrate-directed epoxidation of the terminal double bond of the corresponding γ-amino-α,β-diol with aqueous hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by phosphotungstic heteropoly acid. Each of the key reactions proceeded with an excellent diastereoselectivity (dr > 95:5). (±)-Codonopsinol B was prepared in 10 steps with overall 8.4% yield. The antiproliferative effect of (±)-codonopsinol B and its N-nor-methyl analogue was evaluated using several cell line models.

Keywords: alkaloids, antiproliferative effect, codonopsinol B, diastereoselectivity, pyrrolidines

Introduction

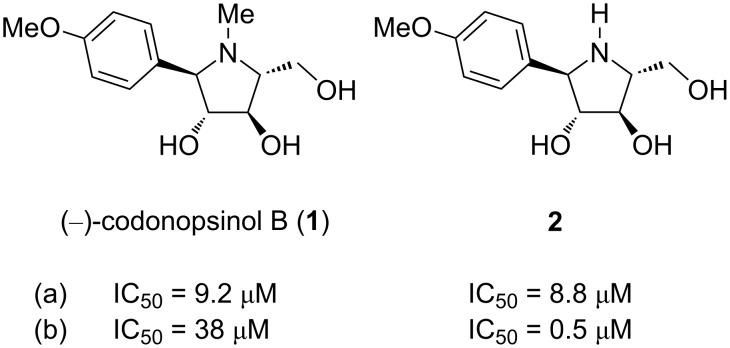

Codonopsinol B (1) is a polyhydroxylated pyrrolidine alkaloid isolated from the roots of the plant Codonopsis pilosula (Figure 1) [1]. This compound was first prepared synthetically before its isolation from natural crude material, employing a stereoselective addition of an aryl Grignard reagent to a five-membered chiral cyclic nitrone derived from ᴅ-arabinose [2]. Its analytical data were consistent with those for the later isolated natural product. Codonopsinol B, together with its N-nor-methyl analogue 2, proved to be a potent α-glucosidase inhibitor (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

(−)-Codonopsinol B (1) and its N-nor-methyl analogue 2; known inhibition activities against α-glucosidases from: (a) Bacillus stearothermophilus lyoph., (b) yeast [2].

The potency it showed is higher than that of the known natural alkaloids such as radicamines A and B [3–4], and codonopsinol [5]. In contrast, the unnatural enantiomers of 1 and radicamine A were inactive towards the examined α-glucosidases. The enantiomer of 2 was the only one that still exhibited inhibitory activity against yeast α-glucosidase [2]. To our knowledge, the sole total synthesis of (−)-codonopsinol B and similar hydroxylated pyrrolidines to date was reported in the above mentioned work. Pyrrolidine 2 has been prepared before, however, it was not tested against glycosidases [6]. In addition, a very limited number of related 2-aryl-substituted hydroxylated pyrrolidines with a hydroxymethyl substituent at C-5 have been synthesized [7].

Along with (−)-codonopsinol B, five other pyrrolidine alkaloids, namely codonopsinol A and C, codonopiloside A, codonopyrrolidium B, and radicamine A, have been isolated from C. pilosula [1]. Its fresh or dried roots are generally considered as famous herbal medicines and are a part of Radix Codonopsis (together with C. pilosula var. modesta and C. tangshen). This crude drug is called Dangshen in Chinese and Tojin in Japanese and has been used as traditional Chinese medicine with numerous beneficial pharmacological activities to treat multiple diseases [8–9], including cancer [10–13]. It is assumed that polyacetylenes, phenylpropanoids, triterpenoids, polysaccharides, and alkaloids are responsible for the majority of the activities found in Codonopsis species. Although the polyhydroxylated pyrrolidine alkaloids from C. pilosula possess glycosidase inhibitory activities and they are considered to be anticancer species, their activity against human cancer cell lines has never been described.

In view of this, we have developed an efficient and highly diastereoselective approach towards codonopsinol B (1) and its N-nor-methyl analogue 2 from achiral starting materials and evaluated their anticancer activity using four different cancer cell lines U87-MG, HepG2, JEG-3 and MOLM-13 (AML cell line) as well as immortalized proximal tubular cells HK2. We have very recently found out that even enantiomerically pure polyhydroxylated pyrrolizidine alkaloids with proven antiglycosidase activities may not exhibit antiproliferative effects against cancer cell lines [14]. For this reason, the compounds 1 and 2 were prepared first in their racemic form to begin the initial biological studies.

Results and Discussion

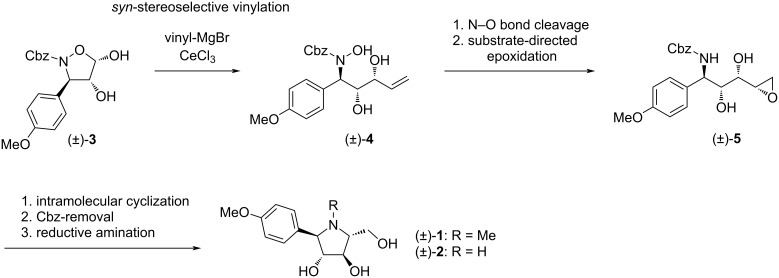

The starting isoxazolidine-4,5-diol 3, possessing the desired 3,4-trans configuration (Scheme 1), will be prepared by using our methodology based on the trans-stereoselective epoxidation reaction of 2,3-dihydroisoxazoles followed by the regioselective hydrolysis of the corresponding isoxazolidinyl epoxide [15–16]. Very recently, we have reported the synthesis of γ-(hydroxyamino)-α,β-diols by the addition of Grignard reagents to isoxazolidine-4,5-diols in the presence of anhydrous cerium chloride [17], which proceeded in a highly syn-diastereoselective manner due to the presence of the unprotected hydroxy group in the α-position. Accordingly, the diol 3 will be examined in the reaction with vinylmagnesium bromide with an emphasis on the expected high syn diol diastereoselectivity (Scheme 1). The obtained anti,syn-(hydroxyamino)alkenol 4 will be then subjected to reductive cleavage of the N–O bond. Next, a key intermediate epoxide 5 with the desired syn (threo) configuration between the hydroxy group and the epoxide oxygen could be prepared by substrate-directed epoxidation. A subsequent SN2 intramolecular epoxide ring-opening cyclization could provide an N-Cbz-protected pyrrolidine derivative with a hydroxymethyl group at C-5 and with trans configuration relative to the hydroxy group at C-4. Finally, (±)-codonopsinol B (1) will be obtained by treatment of the deprotected pyrrolidine 2 with formaldehyde under reductive amination conditions.

Scheme 1.

Synthetic approach towards (±)-codonopsinol B (1) and its N-nor-methyl analogue 2.

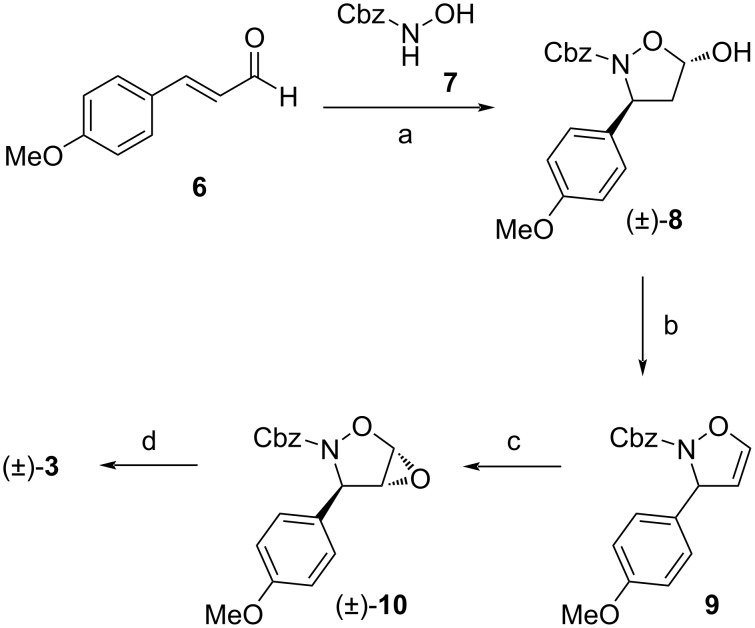

As described in Scheme 2, isoxazolidine-4,5-diol 3 was readily synthesized in four steps according to our procedure [16], starting from commercially available (E)-4-methoxycinnamaldehyde (6). Thus, the reaction of 6 with N-Cbz-protected hydroxylamine 7 catalyzed by ᴅʟ-proline in chloroform gave racemic 5-hydroxyisoxazolidine 8 in 77% yield almost as a sole trans isomer (dr > 9:1). Its structure was confirmed by comparison with already reported NMR data for the known (3S,5S)-enantiomer [18]. We have used ᴅʟ-proline for three reasons: first, it provides the target compounds 1 and 2 in their racemic form, second, it is able to catalyze the conjugate addition between N-EWG-protected hydroxylamines and enals effectively, and third, based on our experience, the products obtained by the proline catalysis are of higher purity (after purification by silica gel column chromatography), than those synthesized by other methods [16]. Definitely, the effective asymmetric organocatalytic conjugate additions of hydroxylamines to enals using various catalysts provide access to enantiomerically enriched isoxazolidin-5-ols [18–24], which, if needed can be converted into the desired pyrrolidine alkaloids. Treatment of 8 with Tf2O in the presence of 2-fluoropyridine in NMP at room temperature afforded 2,3-dihydroisoxazole 9 in good 68% yield. The use of originally reported 2-chloropyridine reduced the product yield slightly to 60% [25]. The subsequent epoxidation of 9 with in situ-generated DMDO (a combination of oxone and NaHCO3 in acetone/water) provided isoxazolidinyl epoxide 10 in almost quantitative yield as a sole trans isomer (dr > 95:5).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of isoxazolidine-4,5-diol (±)-3. Reagents and conditions: (a) ᴅʟ-proline, CHCl3, rt, 48 h, 77%; (b) Tf2O, 2-fluoropyridine, NMP, −20 °C to rt, 16 h, 68%; (c) oxone, NaHCO3, acetone/H2O 3:2, 0 °C to rt, 80 min, 99%; (d) HCl (37 wt % in H2O), acetone/H2O 4:1, 0 °C, 30 min, 93%.

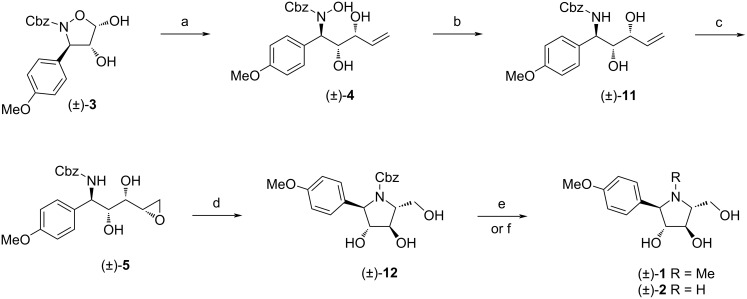

Finally, the acid-catalyzed hydrolysis of 10 with concentrated hydrochloric acid in acetone/water afforded diol 3 in excellent 93% yield. The crystallization of the crude product from a hexanes/CH2Cl2 mixture led to the preferential formation of the thermodynamically more stable 4,5-cis isomer (determined on the basis of a doublet at δ = 5.63 ppm with J4,5 = 4.1 Hz for the H-5 proton). The reaction of isoxazolidine-4,5-diol 3 with vinylmagnesium bromide in the presence of 1.5 equivalents of anhydrous CeCl3 in THF at room temperature proceeded with an excellent syn selectivity providing only one anti,syn isomer of γ-(hydroxyamino)-α,β-diol 4 (dr > 95:5) in 73% yield (Scheme 3). Its relative configuration was determined by comparison with already reported NMR data of related γ-(hydroxyamino)-α,β-diols [17]. More specifically, the value of the vicinal coupling constant J2,3 = 1.8 Hz and the chemical shift of the H-2 proton at 4.22 ppm referred to the 2,3-syn configuration. Whereas the above mentioned addition was highly diastereoselective, the same reaction under identical conditions but in the absence of CeCl3 resulted in the formation of a small amount of the anti,anti diastereomer of 4 (anti,syn/anti,anti, 80:20). Subsequently, the treatment of anti,syn-4 with zinc in acetic acid at 40 °C gave the N-Cbz-protected amino diol 11 in a very good yield of 85% [20,26].

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of final pyrrolidines (±)-1 and (±)-2. Reagents and conditions: (a) vinyl-MgBr, CeCl3, THF, 0 °C to rt, 16 h, 73%; (b) Zn dust, AcOH, 40 °C, 24 h, 85%; (c) 12WO3·H3PO4×H2O, H2O2 (35 wt % in H2O), pyridine, ethyl acetate, rt, 48 h, 70%; (d) BF3·OEt2, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 15 min, 69%; (e) H2 (1 atm), Pd(OH)2/C (5 wt %), MeOH, rt, 2 h, (±)-2, 71%; (f) H2 (1 atm), Pd(OH)2/C (5 wt %), MeOH, rt, 2 h; then formaldehyde (37 wt % in H2O), H2 (1 atm), Pd(OH)2/C (5 wt %), MeOH, rt, 16 h, (±)-1, 58% over two steps.

Next, we investigated the substrate-directed epoxidation that could deliver an oxygen atom from the same side of the double bond as the adjacent hydroxy group [27]. First, the epoxidation of 11 with m-CPBA in dichloromethane was carried out. However, the reaction was almost nonselective regardless to the reaction temperature, affording a mixture of both syn and anti isomers of epoxide 5 in comparable amounts (syn/anti, 58:42; see Supporting Information File 1, page S25). Although the syn selectivity was further improved (80:20) by using the in situ-generated trifluoroperoxyacetic acid [28], the reaction suffered from formation of a high level of impurities. Gratifyingly, this issue has been overcome by the use of hydrogen peroxide in the presence of phosphotungstic heteropoly acid, a commercial heteropoly acid [29–30]. Under our optimized conditions in terms of amount of catalyst, reaction temperature, and organic co-solvent, the epoxidation of 11 with aqueous H2O2 (35 wt %) and 12WO3·H3PO4×H2O (1 mol %) at room temperature in ethyl acetate provided the desired epoxide 5 in an acceptable 70% yield with excellent stereoselectivity as the sole syn isomer (dr > 95:5). It is worth noting that a small quantity of pyridine was added to prevent unwanted acid-catalyzed epoxide hydrolysis [31]. The stereochemistry of 5 was assigned later after pyrrolidine ring formation. Since the aqueous tungstic acid-catalyzed hydrogen peroxide epoxidations of monosubstituted allylic alcohols usually proceed in anti (erythro) stereoselective fashion [32], we propose that the high syn selectivity can be attributed to the presence of the unprotected hydroxy group in the homoallylic position that assists the electrophilic attack on the double bond [33–34]. The protection of the homoallylic hydroxy group in similar alkenyl diols in epoxidations with the VO(acac)2/t-BuOOH system led to the formation of the erythro isomer [35]. Actually, highly stereoselective epoxidations of terminal alkenes bearing both an allylic and homoallylic-type hydroxy group, yielding a sole threo isomer, are rare [36].

The cyclization of 5 through an epoxide ring-opening reaction with boron trifluoride etherate in dichloromethane at 0 °C yielded pyrrolidine derivative 12 in 69% isolated yield [37]. Its structure was determined on the basis of 1H and 13C NMR spectra. The relative configuration was unambiguously confirmed by X-ray crystallographic analysis (Figure 2) [38] (see also Supporting Information File 1, Figures S1–S3).

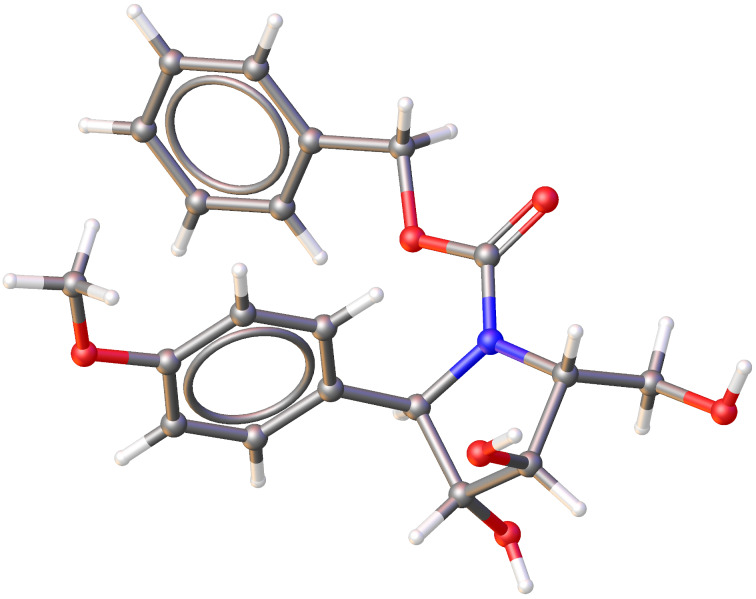

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of N-Cbz-protected pyrrolidine 12 confirmed by single-crystal X-ray crystallographic analysis, proving the same relative configuration as that in natural codonopsinol B.

Interestingly, NMR spectroscopy of 12 revealed that it exists as a mixture of two rotamers in a ≈2:1 ratio at 25 °C, probably caused by the Cbz-protecting group (see Supporting Information File 1, page S26).

It is worth mentioning that the attempts to prepare polyhydroxylated pyrrolidine 2 directly from epoxide 5 by the one pot Cbz-removal/aminocyclization under hydrogenolysis conditions led only to the formation of several undesired byproducts. To our satisfaction when compound 12 was subjected to catalytic hydrogenation using Pd(OH)2/C in methanol [39], 2 was formed in 71% yield.

Finally, (±)-codonopsinol B (1) was directly obtained from 12 in the yield of 58% (over two steps) under the same reaction conditions when using formaldehyde (37 wt % in H2O). The 1H and 13C NMR spectra recorded on compounds (±)-1 and (±)-2 were in good agreement with those previously reported for the natural sample [1] as well as for the synthetic products [2].

Biological evaluation

(±)-Codonopsinol B (1) and its N-nor-methyl analogue 2 were evaluated for their antiproliferative activity against the four cancer cell lines U87-MG, HepG2, JEG-3, MOLM-13 and against immortalized proximal tubular cells HK2 (see Supporting Information File 1, Table S1, Figures S4–S8). The IC50 values of all tested compounds exceeded the highest treated concentration (1000 µM respectively and 500 µM for MOLM-13) or were not defined by the employed method of analysis (see Supporting Information File 1). The findings reveal that these compounds display no antiproliferative activity at the tested concentrations.

The results may indicate that the expected antiglycosidase activities of the tested compounds are not sufficient enough to be effective in the examined cancer cell lines. The observed weak or even no antiproliferative activities may be caused due to the high hydrophilicity of the polyhydroxylated pyrrolidine core. It is proven that the presence of lipophilic groups in the structure of such compounds improves their penetration trough the cell membrane, and thereby increases their antitumor effectiveness [40].

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed an efficient highly diastereoselective synthesis of racemic codonopsinol B (1) and its N-nor-methyl analogue 2 starting from achiral materials. Four consecutive stereocenters in the target molecules were accomplished sequentially by the organocatalytic aza-Michael addition of N-Cbz-protected hydroxylamine to (E)-4-methoxycinnamaldehyde, the trans-stereoselective epoxidation of 2,3-dihydroisoxazole 9 with in situ-generated DMDO, the syn-selective α-chelation-controlled addition of vinylmagnesium bromide to isoxazolidine-4,5-diol 3 in the presence of cerium chloride, and the substrate-directed epoxidation of the terminal double bond of N-Cbz-protected γ-amino-α,β-diol 11 with aqueous hydrogen peroxide catalyzed by phosphotungstic heteropoly acid. Each of the key reactions proceeded with an excellent diastereoselectivity (dr > 95:5). Employing our synthetic strategy, racemic codonopsinol B was prepared in 10 steps with overall 8.4% yield.

Although naturally occurring (−)-codonopsinol B (1) and its N-nor-methyl analogue 2 were found to be effective α-glucosidase inhibitors, their racemic forms showed no evident antiproliferative activities against the selected human cancer cell lines U87-MG, HepG2, JEG-3 and MOLM-13 as well as immortalized proximal tubular cells HK2.

Supporting Information

Detailed experimental procedures, characterization data and NMR spectra of synthesized compounds, X-ray crystallographic data of 12, and biological evaluation of antiproliferative activities of 1 and 2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank to Dr. Vladimír Mastihuba for HPLC measurements.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Slovak Grant Agency for Science VEGA (project nos. 1/0552/18, 2/0057/18), and Charles University Research Programme Progres (grant no. Q42).

Contributor Information

František Trejtnar, Email: trejtnarf@faf.cuni.cz.

Lucia Messingerová, Email: lucia.messingerova@stuba.sk.

Róbert Fischer, Email: robert.fischer@stuba.sk.

References

- 1.Wakana D, Kawahara N, Goda Y. Chem Pharm Bull. 2013;61:1315–1317. doi: 10.1248/cpb.c13-00516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsou E-L, Chen S-Y, Yang M-H, Wang S-C, Cheng T-R R, Cheng W-C. Bioorg Med Chem. 2008;16:10198–10204. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2008.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shibano M, Tsukamoto D, Masuda A, Tanaka Y, Kusano G. Chem Pharm Bull. 2001;49:1362–1365. doi: 10.1248/cpb.49.1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu C-Y, Huang M-H. Org Lett. 2006;8:3021–3024. doi: 10.1021/ol0609210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagadeesh Y, Reddy J S, Rao B V, Swarnalatha J L. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.12.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliveira D F, Severino E A, Correia C R D. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2083–2086. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(99)00151-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jain V K. Synthesis. 2019;51:4635–4644. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1610729. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.He J-Y, Ma N, Zhu S, Komatsu K, Li Z-Y, Fu W-M. J Nat Med. 2015;69:1–21. doi: 10.1007/s11418-014-0861-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao S-M, Liu J-S, Wang M, Cao T-T, Qi Y-D, Zhang B-G, Sun X-B, Liu H-T, Xiao P-G. J Ethnopharmacol. 2018;219:50–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2018.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xin T, Zhang F, Jiang Q, Chen C, Huang D, Li Y, Shen W, Jin Y, Sui G. Int J Biol Macromol. 2012;51:788–793. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang Y-y, Zhang Y-m, Xu H-y. Int J Polym Sci. 2019:7068437. doi: 10.1155/2019/7068437. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He W, Tao W, Zhang F, Jie Q, He Y, Zhu W, Tan J, Shen W, Li L, Yang Y, et al. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24(6):3359–3369. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.15009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bailly C. Nat Prod Bioprospect. 2021;11(2):143–153. doi: 10.1007/s13659-020-00283-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dikošová L, Otočková B, Malatinský T, Doháňošová J, Kopáčová M, Ďurinová A, Smutná L, Trejtnar F, Fischer R. RSC Adv. 2021;11:31621–31630. doi: 10.1039/d1ra06225e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Záborský O, Malatinský T, Marek J, Moncol J, Fischer R. Eur J Org Chem. 2016:3993–4002. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201600471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Záborský O, Štadániová R, Doháňošová J, Moncol J, Fischer R. Synthesis. 2017;49:4942–4954. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1590924. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ďurina L, Malatinský T, Moncol J, Záborský O, Fischer R. Synthesis. 2021;53:688–698. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1706543. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai J, Sayalero S, Ferrali A, Osorio-Planes L, Bravo F, Rodríguez-Escrich C, Pericàs M A. Adv Synth Catal. 2018;360:2914–2924. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201800572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dou Q-Y, Tu Y-Q, Zhang Y, Tian J-M, Zhang F-M, Wang S-H. Adv Synth Catal. 2016;358:874–879. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201501025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y K, Yoshida M, MacMillan D W C. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9328–9329. doi: 10.1021/ja063267s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Juarez-Garcia M E, Yu S, Bode J W. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:4841–4853. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2010.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Enders D, Wang C, Liebich J X. Chem – Eur J. 2009;15:11058–11076. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ibrahem I, Rios R, Vesely J, Zhao G-L, Córdova A. Synthesis. 2008:1153–1157. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-990935. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu F-F, Chen L-Y, Sun P, Lv Y, Zhang Y-X, Li J-Y, Yin X, Li Y. Chirality. 2020;32:378–386. doi: 10.1002/chir.23168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Záborský O, Šoral M, Fischer R. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:2155–2158. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.03.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miyabe H, Moriyama K, Takemoto Y. Chem Pharm Bull. 2011;59:714–720. doi: 10.1248/cpb.59.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoveyda A H, Evans D A, Fu G C. Chem Rev. 1993;93:1307–1370. doi: 10.1021/cr00020a002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gil L, Compère D, Guilloteau-Bertin B, Chiaroni A, Marazano C. Synthesis. 2000:2117–2126. doi: 10.1055/s-2000-8712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuznetsova L I, Maksimovskaya R I, Fedotov M A. Russ Chem Bull. 1985;34:488–493. doi: 10.1007/bf00947706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oguchi T, Sakata Y, Takeuchi N, Kaneda K, Ishii Y, Ogawa M. Chem Lett. 1989;18(11):2053–2056. doi: 10.1246/cl.1989.2053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada Y M A, Ichinohe M, Takahashi H, Ikegami S. Org Lett. 2001;3:1837–1840. doi: 10.1021/ol015863r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prat D, Delpech B, Lett R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:711–714. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)84080-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bartlett P A, Jernstedt K K. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:4829–4830. doi: 10.1021/ja00456a052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mihelich E D, Daniels K, Eickhoff D J. J Am Chem Soc. 1981;103:7690–7692. doi: 10.1021/ja00415a067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Surivet J-P, Goré J, Vatèle J-M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:371–374. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(95)02125-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roush W R, Michaelides M R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1986;27:3353–3356. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)84794-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakata M, Tamai T, Kamio T, Kinoshita M, Tatsuta K. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1994;67:3057–3066. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.67.3057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.CCDC 2058692 (IAM) and CCDC 2099851 (HAR) contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. The data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/getstructures.

- 39.Takahata H, Banba Y, Momose T. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:7635–7644. doi: 10.1016/s0040-4020(01)88287-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fiaux H, Popowycz F, Favre S, Schütz C, Vogel P, Gerber-Lemaire S, Juillerat-Jeanneret L. J Med Chem. 2005;48:4237–4246. doi: 10.1021/jm0409019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detailed experimental procedures, characterization data and NMR spectra of synthesized compounds, X-ray crystallographic data of 12, and biological evaluation of antiproliferative activities of 1 and 2.