Abstract

Objectives To evaluate disparities in youth e-cigarette use patterns and flavor use by race/ethnicity over time.

Methods We used data from the US 2014–2019 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) to examine trends in dual use (co-use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes or other tobacco products), occasional (≤ 5 days) versus frequent use (≥ 20 days) in the past 30 days, and flavor use among current (past-30-day) e-cigarette users (n = 13 178) across racial/ethnic groups (non-Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics/Latinos, and non-Hispanic others).

Results Among current e-cigarette users, dual use and occasional use decreased significantly from 2014 to 2019 across racial and ethnic groups except for non-Hispanic Blacks; frequent use and flavored e-cigarette use increased among non-Hispanic Whites, Hispanics/Latinos, and non-Hispanic others but not among non-Hispanic Blacks. In 2019, non-Hispanic Black e-cigarette users were more likely to report dual use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 2.2; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.5, 3.2; P < .001) and occasional use of e-cigarettes (AOR = 3.7; 95% CI = 2.3, 5.9; P < .001) but less likely to report frequent use (AOR = 0.2; 95% CI = 0.1, 0.4; P < .001) and flavored e-cigarette use (AOR = 0.4; 95% CI = 0.3, 0.5; P < .001) than their White peers.

Conclusions Youth e-cigarette use patterns differed considerably across racial/ethnic groups, and tailored strategies to address disparities in e-cigarette use are needed. (Am J Public Health. 2021;111(11):2050–2058. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2021.306448)

While the cigarette smoking rate among youths has been declining over the past several decades,1,2 the prevalence of current (past-30-day) e-cigarette use (or vaping) among adolescents increased dramatically during 2017 to 2019.2,3 Although e-cigarettes deliver a substantially lower level of toxins than do combustible cigarettes,4 e-cigarette aerosol is not harmless, as studies have identified harmful and potentially harmful constituents in e-cigarettes.5 Vaping at a young age could cause nicotine addiction, harm brain development, and increase risks of respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.5–7

Race/ethnicity may differentiate youth tobacco use, and non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic/Latino tobacco users experience significant health disparities in tobacco-related diseases, including cancer, stroke, and heart disease.8,9 Studies have documented that non-Hispanic Black adolescents report a significantly lower prevalence of cigarette smoking but a higher prevalence of cigar use than their Hispanic/Latino and White peers.10 Hispanic/Latino youths reported a higher prevalence of hookah use.10 Recent studies also indicate that e-cigarettes are not uniformly used across racial and ethnic groups,5 and non-Hispanic White and Hispanic/Latino youths are more likely to use e-cigarettes than are non-Hispanic Black youths.10,11 Longitudinal studies also show distinct transition patterns by racial and ethnic group,12,13 and White and Hispanic adolescent e-cigarette users are more likely to transition to cigarette smoking than their Black counterparts.13 Another national study found that non-Hispanic Black students and Hispanic students significantly initiate e-cigarettes at an earlier age than White peers.14 Alarmingly, early initiation (age 13 years and younger vs older than 13 years) of e-cigarettes could increase the risk of nicotine dependence and sustained e-cigarette use.14 A socioecological model posits that multifaceted factors at the individual, interpersonal, community, and policy levels could lead to distinct patterns of exposure to secondhand tobacco, tobacco initiation, use patterns, and cessation behaviors by race and ethnicity.15 These existential disparities in e-cigarette and tobacco use may be attributable to social determinants related to race/ethnicity (e.g., education, income, geography), neuropsychological factors, the long history of the tobacco industry’s aggressive marketing toward racial and ethnic minority communities, and biological aspects.5,8,9

A growing body of literature has extended current youth e-cigarette research to better understand the frequency of e-cigarette use, co-use of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products, and flavored e-cigarette use. For instance, Glasser et al.16 reported that about half of current e-cigarette users vaped occasionally (≤ 5 days in the past 30 days) and roughly a quarter vaped frequently (≥ 20 days in the past 30 days) in 2018.16 E-cigarette use is strongly associated with cigarette smoking and other tobacco use; a majority of young current e-cigarette users have been found to report concurrently using 1 or more other tobacco products.5,17 A previous study17 identified that, across racial and ethnic groups, most current tobacco users were dual or poly tobacco users in 2014. But it is unclear whether poly tobacco use behaviors have changed since then.

Meanwhile, flavored e-cigarette products are widely available in the United States, and flavors have become one of the leading reasons for current e-cigarette use among youths.18 Flavored e-cigarette use has been increasing among youths since 2015, with 65.2% of current e-cigarette users reporting use of flavored products in the past 30 days in 2018.19,20 However, little is known about differential patterns of e-cigarette use and flavor use across racial/ethnic groups over time. Understanding how adolescents use e-cigarettes (e.g., use patterns, flavors) is critical to inform regulatory actions and develop effective intervention strategies to prevent and reduce youth vaping behaviors, especially among vulnerable subpopulations such as racial and ethnic minority adolescents.

To address these gaps in knowledge, we analyzed data from the 2014–2019 National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) by examining the changes in temporal trends of e-cigarette use patterns and flavor use among current youth e-cigarette users across racial and ethnic groups. We further tested disparities in e-cigarette use patterns and flavor use across racial/ethnic groups.

METHODS

The NYTS is a nationally representative, cross-sectional, and school-based annual survey of middle- and high-school students between the ages of 9 and 19 years in the United States. The survey was conducted using a probabilistic sampling procedure without replacement at 3 stages: (1) primary sampling units such as a county, a group of small counties, or part of a very large county; (2) secondary sampling units including schools within each selected primary sampling unit; and (3) students within each selected school. The 2014–2019 NYTS data included 117 472 respondents, with the annual survey sample size ranging from 17 711 in 2015 to 22 007 in 2014. The median response rate for participating schools and students ranged from 63.4% to 73.3% during the study period. A detailed description of the NYTS survey can be found on the NYTS Web site.21

Measures

Race/ethnicity

Participants were classified into 4 groups: non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic/Latino, or non-Hispanic other.

E-cigarette use

Current e-cigarette users were determined by those who reported using e-cigarettes 1 or more days in the past 30 days. We further categorized current e-cigarette users as occasional users (≤ 5 days) and frequent users (≥ 20 days) based on the frequency of e-cigarette use in the past 30 days.

Current cigarette smokers were defined as those who reported smoking 1 or more days in the past 30 days, and current other tobacco users were defined as those who reported using 1 or more other tobacco products on 1 or more days of the past 30 days. Other tobacco products included cigars (cigars, little cigars, and cigarillos), smokeless tobacco (chewing tobacco, snuff, dip, snus, and dissolvable tobacco), hookahs, pipe tobacco, and bidis.10 Those who reported current co-use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes or other tobacco products were defined as dual users. Current e-cigarette users who reported using e-cigarettes that tasted like menthol (mint), alcohol (wine, cognac), candy, fruit, chocolate, or any other flavors were classified as flavored e-cigarette users. The NYTS did not have separate questions for each flavor, and a single composite flavor question was utilized. Those who reported not using flavored e-cigarettes were likely to be users of tobacco-flavored or flavorless e-cigarettes or those who did not recall the flavor in e-cigarettes.

Covariates

Demographic variables include gender (male or female), age (continuous variable), school level (middle or high school), and tobacco use by other household members (“none,” “other tobacco product use” [i.e., non‒e-cigarette use], and “e-cigarettes”).

Statistical Analyses

We weighted data to provide national estimates by accounting for the complex survey design and nonresponse. First, weighted percentages and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of sample characteristics (e.g., demographic characteristics, smoking prevalence) among current e-cigarette users were reported from 2014 to 2019.

Second, temporal trends of e-cigarette use patterns (dual use, occasional use, and frequent use) and flavored e-cigarette use from 2014 to 2019 were reported, overall and by racial/ethnic groups. We examined the interaction of year × race/ethnicity in the multivariable model adjusted for covariates, current cigarette smoking, and other tobacco use status. We also reported linear and quadratic trends based on multivariable logistic regression analyses, where survey years served as a continuous variable. We performed stratified analyses by racial/ethnic group. The sample sizes for other races, such as Asians, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, and other Pacific Islanders, were too small to model the temporal trends. Therefore, we combined these minority subpopulations into 1 category (i.e., non-Hispanic others).

Third, we performed separate multivariable logistic regression models to examine the association between race/ethnicity and e-cigarette use patterns and flavor use among current e-cigarette users by using the 2019 NYTS data. The temporal trends in associations between race/ethnicity and e-cigarette use patterns from 2014 to 2019 are reported in Figure A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) are reported in the multivariable analysis. We analyzed data by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) survey procedures, and we considered a P level of less than .05 to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

The analytical sample included 13 178 current e-cigarette users from the combined 2014–2019 NYTS (female, 44.6%; high school, 79.8%; non-Hispanic White, 65.0%; non-Hispanic Black, 7.6%; Hispanic/Latino, 23.6%; current cigarette smokers, 28.6%; current other tobacco use, 43.0%). Table A (available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org) presents the sample characteristics of current e-cigarette users from 2014 to 2019. Overall, the distribution of e-cigarette users by age and grade was relatively stable, while more female students were current e-cigarette users in 2019 (47.8%) than in 2014 (44.1%). Among current e-cigarette users, the prevalence of current cigarette smoking dropped dramatically from 37.6% in 2014 to 17.9% in 2019. We also observed a decreasing trend in the prevalence of current other tobacco use (56.5% in 2014 to 30.8% in 2019). Table B reports the unweighted sample sizes for each outcome variable by racial/ethnic group.

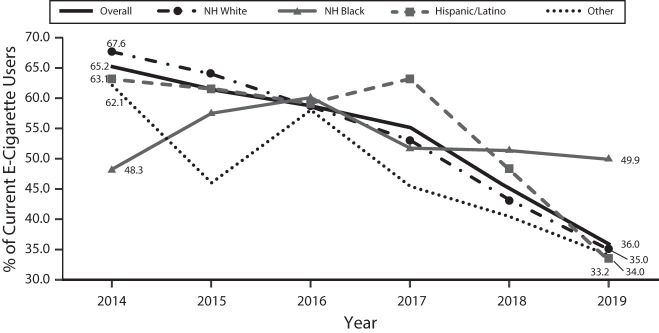

Figure 1 presents the temporal trends of dual use among current e-cigarette users from 2014 to 2019. The overall dual use decreased significantly from 65.2% in 2014 to 36.0% in 2019 (difference = −29.2%; 95% CI = ‒34.4%, −24.0%) and fit a significant quadratic trend over 2014 to 2019 (P = .009). Changes in dual use among current e-cigarette users from 2014 to 2019 differed significantly by racial and ethnic group (year × race/ethnicity; P < .001). The decreases were significant for non-Hispanic Whites (AOR = 0.76; 95% CI = 0.72, 0.80; P < .001) and non-Hispanic others (AOR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.71, 1.00; P = .046). The changes fit a quadratic trend for Hispanics/Latinos (P < .001). For non-Hispanic Blacks, there was no significant change in dual use from 48.3% in 2014 to 49.9% in 2019 (AOR = 0.97; 95% CI = 0.88, 1.06; P = .46).

FIGURE 1—

Trends in Dual Use Among Current E-Cigarette Users: United States, 2014–2019

Note. NH = non-Hispanic. The y-axis shows the observed % of dual use (co-use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes or other tobacco products) among current e-cigarette users. Multivariable regression models adjusted for age, gender, and tobacco use by a household member. The interaction for year × race/ethnicity was P < .001. Overall: quadratic trend, P = .009. NH White: linear trend, adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.76; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.72, 0.80; P < .001; quadratic trend, P = .24. NH Black: linear trend, AOR = 0.96; 95% CI = 0.87, 1.06; P = .40; quadratic trend, P = .16. Hispanic/Latino: quadratic trend, P < .001. NH other: linear trend, AOR = 0.84; 95% CI = 0.71, 1.00; P = .046; quadratic trend, P = .67.

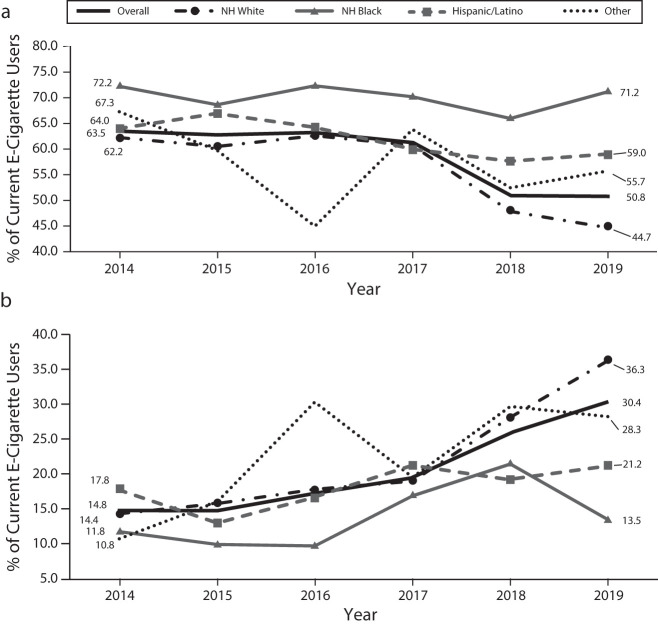

Among current e-cigarette users, there was a significant decrease in occasional use (Figure 2a; 63.5% in 2014 vs 50.8% in 2019; quadratic trend, P < .001) and a significant increase of frequent use (Figure 2b; 14.8% in 2014 vs 30.4% in 2019; quadratic trend, P < .001). Changes in use patterns among current e-cigarette users differed by racial and ethnic group (year × race/ethnicity; P < .001). The drops in occasional use were significant across all racial/ethnic groups except for non-Hispanic Blacks, for whom the proportion was stable at 72.2% in 2014 versus 71.2% in 2019 (AOR = 1.01; 95% CI = 0.90, 1.13; P = .87). Similarly, the increases in frequent use were significant across all racial/ethnic groups except for non-Hispanic Blacks with a stable trend at 11.8% in 2014 versus 13.5% in 2019 (AOR = 1.10; 95% CI = 0.95, 1.27; P = .19).

FIGURE 2—

Trends in E-Cigarette Use Among Current E-Cigarette Users, by (a) Occasional Use and (b) Frequent Use: United States, 2014–2019

Note. NH = non-Hispanic. The y-axis shows the observed % of (a) occasional (≤ 5 days in the past 30 days) or (b) frequent (≥ 20 days in the past 30 days) e-cigarette use among current e-cigarette users. Multivariable regression models adjusted for age, gender, current cigarette smoking, current other tobacco use, and tobacco use by a household member. The interaction for year × race/ethnicity was P < .001. Overall: quadratic trend, P < .001. NH White: quadratic trend, P < .001. NH Black: linear trend, adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.01; 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.91, 1.13; P = .87; quadratic trend, P = .92. Hispanic/Latino: quadratic trend, P = .02; NH others: linear trend, AOR = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.77, 0.98; P = .02; quadratic trend, P = .38. Overall: quadratic trend, P < .001. NH Whites: quadratic trend, P < .001. NH Black: linear trend, AOR = 1.10; 95% CI = 0.95, 1.27; P = .19; quadratic trend, P = .92. Hispanic/Latino: quadratic trend, P = .005. NH other: linear trend, AOR = 1.42; 95% CI = 1.20, 1.67; P < .001; quadratic trend, P = .64.

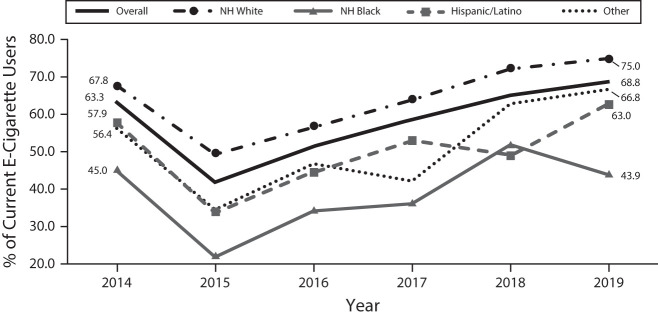

Changes in flavor use among current e-cigarette users fit a quadratic trend from 2014 to 2019 (P < .001) with a significant decrease from 2014 to 2015 and then a significant increase from 2015 to 2019 (Figure 3). The interaction term between the year and race/ethnicity was not significant (P = .23). Table 1 presents univariate and multivariable analyses of e-cigarette use patterns and race/ethnicity among current e-cigarette users in 2019 (n = 3628). Non-Hispanic Black e-cigarette users had higher odds of reporting dual use compared with their White peers (AOR = 2.2; 95% CI = 1.5, 3.2; P < .001). Non-Hispanic White e-cigarette users were less likely than their racial/ethnic minority peers to report occasional use but more likely to report frequent use. For instance, 44.7% (95% CI = 41.6%, 47.8%) of non-Hispanic White e-cigarette users reported occasional use in 2019, compared with 71.2% (95% CI = 64.0%, 78.4%) of non-Hispanic Blacks (AOR = 3.7; 95% CI = 2.3, 5.9; P < .001) and 59.0% (95% CI = 54.9%, 63.1%) of Hispanics/Latinos (AOR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.3, 2.0; P < .001). Conversely, 36.3% (95% CI = 32.9%, 39.7%) of non-Hispanic White e-cigarette users reported frequent use in 2019, in comparison with 13.5% (95% CI = 8.4%, 18.6%) of non-Hispanic Blacks (AOR = 0.2; 95% CI = 0.1, 0.4; P < .001) and 21.2% (95% CI = 17.3%, 25.1%) of Hispanics/Latinos (AOR = 0.5; 95% CI = 0.4, 0.7; P < .001).

FIGURE 3—

Trends in Flavored E-Cigarette Use Among Current E-Cigarette Users: United States, 2014–2019

Note. NH = non-Hispanic. The y-axis shows the observed % of flavored e-cigarette use among current e-cigarette users. Multivariable regression models adjusted for age, gender, current cigarette smoking, current other tobacco use, tobacco use by a household member, and the number of days using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days. The interaction term of year × race/ethnicity: P = .56. Overall: quadratic trend, P < .001. NH White: quadratic trend, P < .001. NH Black: linear trend, adjusted odds ratio = 1.12; 95% confidence interval = 1.03, 1.22; P = .01; quadratic trend, P = .11. Hispanic/Latino: quadratic trend, P < .001. NH other: quadratic trend, P = .004.

TABLE 1—

Univariate and Multivariable Analysis of E-Cigarette Use Behaviors Among Current E-Cigarette Users: United States, 2019 National Youth Tobacco Survey

| Weighted % (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

| Dual usea | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| NH White | 35.0 (30.2, 39.8) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| NH Black | 49.9 (41.6, 58.2) | 1.8 (1.3, 2.6) | 2.2b (1.5, 3.2) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 33.2 (29.4, 37.0) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.2) | 1.1b (0.9, 1.4) |

| Other | 34.0 (22.1, 46.0) | 1.0 (0.6, 1.7) | 1.0b (0.6, 1.8) |

| Occasional e-cigarette usec | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| NH White | 44.7 (41.6, 47.8) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| NH Black | 71.2 (64.0, 78.4) | 3.1 (2.1, 4.5) | 3.7d (2.3, 5.9) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 59.0 (54.9, 63.1) | 1.8 (1.5, 2.2) | 1.6d (1.3, 2.0) |

| Other | 55.7 (46.1, 65.4) | 1.6 (1.0, 2.4) | 1.5d (0.9, 2.3) |

| Frequent e-cigarette usec | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| NH White | 36.3 (32.9, 39.7) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| NH Black | 13.5 (8.4, 18.6) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.4) | 0.2d (0.1, 0.4) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 21.2 (17.3, 25.1) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.6) | 0.5d (0.4, 0.7) |

| Other | 28.3 (19.7, 36.9) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.1) | 0.8d (0.5, 1.3) |

| Flavored e-cigarette usee | |||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| NH White | 75.0 (72.5, 77.6) | 1 (Ref) | 1 (Ref) |

| NH Black | 43.9 (37.1, 50.7) | 0.3 (0.2, 0.3) | 0.4f (0.3, 0.5) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 63.0 (58.6, 67.3) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 0.7f (0.5, 0.9) |

| Other | 66.8 (57.5, 76.1) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.0) | 0.8f (0.5, 1.2) |

Note. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NH = non-Hispanic; OR = odds ratio. The sample size was n = 3628.

Dual use (co-use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes or other tobacco products) was the dependent variable (yes vs no).

Adjusted by age, gender, and tobacco use by a household member.

Occasional use (1‒5 days in the past 30 days) and frequent use (≥20 days in the past 30 days) were the dependent variables (yes vs no) and analyzed separately.

Adjusted by age, gender, current cigarette smoking, current other tobacco use, and tobacco use by a household member.

Flavored e-cigarette use (tasted like menthol [mint], alcohol [wine, cognac], candy, fruit, chocolate, or any other flavors) was the dependent variable (yes vs no). Flavored e-cigarette use was correlated with the number of days using e-cigarettes in the past 30 d. In 2019, the proportions of flavored e-cigarette use among current e-cigarette users reporting e-cigarettes 1–2 days, 3–5 days, 6–9 days, 10–19 days, 20–29 days, and all 30 days were 54.2%, 66.4%, 71.6%, 76.0%, 79.6%, and 84.1%, respectively.

Adjusted by age, gender, current cigarette smoking, current other tobacco use, tobacco use by a household member, and the number of days using e-cigarettes in the past 30 days.

Flavored e-cigarette use differed significantly by racial and ethnic group, with non-Hispanic White e-cigarette users reporting the highest proportion (75.0%; 95% CI = 72.5%, 77.6%) and non-Hispanic Blacks reporting the lowest proportion (43.9%; 95% CI = 37.1%, 50.7%; AOR = 0.4; 95% CI = 0.3, 0.5; P < .001).

Temporal trends of associations between e-cigarette use behaviors and race/ethnicity are presented in Figure A. The sensitivity analysis shows wide gaps in dual use, occasional use, and frequent use between non-Hispanic Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites.

DISCUSSION

Although enormous progress has been made in reducing tobacco use in the United States, this progress has not been equally distributed across the population, with a large disparity in tobacco use persisting across groups defined by race/ethnicity, education level, income level, region, and other factors.15 The tobacco use landscape has substantially changed in recent years with more adolescents using e-cigarettes, and the prevalence of youth e-cigarette use has surpassed the use of cigarettes since 2015.22 However, there is a dearth of research in assessing disparities of e-cigarette use with little work comparing trajectory and etiology in e-cigarette use patterns by racial and ethnic subpopulation. Surveillance of current e-cigarette use is important for public health, but attention to past-30-day e-cigarette use prevalence may obscure important use behavioral differences such as occasional use versus frequent use and co-use of e-cigarettes and other tobacco products across racial and ethnic groups.16

This study identified sharply different trends in the dual use between non-Hispanic Blacks and other racial/ethnic groups from 2014 to 2019. For instance, the proportion of current e-cigarette users reporting dual use dropped by nearly half from 65.2% in 2014 to 36.0% in 2019 for non-Hispanic Whites, but the proportion was stable for non-Hispanic Blacks (48.3% vs 49.9%). The multivariable analysis further showed a considerable disparity, with non-Hispanic Black e-cigarette users being 1.8 times more likely to report dual use than their White peers in 2019.

Sensitivity analyses also showed a growing gap between non-Hispanic Blacks and non-Hispanic Whites in dual use over time. One may speculate that the relative preference for combustible products among non-Hispanic Blacks, possibly facilitated by the tobacco industry’s targeted advertising,23 including the promotion of menthol cigarettes and flavored little cigars, drives these results. Another factor to consider is relatively easy access to single cigarettes and cigarillos such as Phillies, Black & Mild, and Swisher Sweets sold individually in segregated Black neighborhoods.24 Dual use may further increase disparities in health outcomes given that multiple tobacco product use is associated with increased symptoms of nicotine dependence and addiction in comparison with single product use.25

Our study showed that e-cigarette use patterns differed considerably by race/ethnicity. From 2014 to 2019, frequent use of e-cigarettes showed a 2.5-fold increase for non-Hispanic White e-cigarette users (14.8% to 36.3%), but the proportion was relatively flat for non-Hispanic Blacks (11.8% to 13.5%; P = .15). Furthermore, non-Hispanic White e-cigarette users were more likely to report frequent e-cigarette use and flavored e-cigarette use than non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics/Latinos in 2019. Studies have shown that vaping more frequently among adolescents was associated with a higher risk of frequent and heavy smoking in the future26 and that flavored e-cigarette use was associated with an increased risk of cigarette smoking and future vaping.27 Even occasional e-cigarette use is associated with significantly higher risks of binge drinking, marijuana use, and other illicit drug use than nonuse.28

These remarkable disparities in e-cigarette use behaviors underscore the importance of developing and implementing tailored strategies to address the e-cigarette use epidemic across race/ethnicity. Our results suggest that non-Hispanic Black adolescents are more likely to be dual users of e-cigarette and other tobacco products, which may lead to less frequent use of e-cigarettes. For non-Hispanic Black youths, tailored interventions are needed to promote prevention and cessation of tobacco use and raise the harm perception of light tobacco use, including the occasional use of e-cigarettes. On the other hand, non-Hispanic White youths seem to be moving toward more exclusive and frequent e-cigarette use. Therefore, evidence-based youth vaping cessation programming may be suitable for this subpopulation. Certainly, while possibly acknowledging differential preferences for various tobacco products, a uniform message might be provided—that any nicotine-containing product is dangerous for youths and may lead to cardiovascular and carcinogenic consequences later on.5

Enactment and implementation of tobacco control policies need to account for differential effects on racial/ethnic subpopulations to ensure that policies can uniformly prevent the initiation and reduce the prevalence of youth tobacco use, which could further lead to a reduction of health disparities in tobacco use and tobacco-related morbidity and mortality. There are large variations in tobacco-free and smoke-free public policies, tobacco taxes, tobacco retail and vape shop density, tobacco product point-of-sale advertising restrictions, and other tobacco control legislation across states and localities. In addition, the contents and coverage of e-cigarette regulations vary by jurisdiction, which could exacerbate inequities in e-cigarette use and tobacco-related disease burden by geography, race, and ethnicity. The nationwide Tobacco 21 policy that was passed in December 2019 to raise the minimum legal age of tobacco sales to 21 years29 could increase tobacco control coverage in minority populations and reduce youth access to tobacco products through commercial and social sources.

The US Food and Drug Administration issued an enforcement policy on unauthorized cartridge-based e-cigarette flavors other than tobacco and menthol, which went into effect on February 6, 2020,30 and further sent warning letters to notify e-cigarette companies including Puff Bar to remove flavored disposable e-cigarette products from the market in July 2020.31 As menthol-flavored tobacco products are particularly appealing to African American tobacco users, continued surveillance of current e-cigarette use by racial and ethnic groups is critically needed.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the NYTS is a survey of middle- and high-school students, and our findings might not be generalizable to the broader youth population. However, 97% of adolescents aged between 10 and 17 years were enrolled in school.32

Second, e-cigarette use behaviors were self-reported, and they are subject to recall bias, especially for younger respondents. However, the test and retest reliability of self-reported behaviors related to tobacco use among adolescents is high.33

Third, self-reported race/ethnicity was grouped into 4 categories to ensure sufficient sample sizes in assessing temporal trends of e-cigarette use. However, a deeper understanding of differences within these groups is needed.

Fourth, these nationally representative data were of repeated cross-sections, and changes in cohort composition over time could affect results (e.g., trends between e-cigarette use and dual use). However, the sample sizes at each time point were large, and sampling strategies for data collection minimize that possibility.34

Fifth, the NYTS only asked a single composite question about flavor use. It is possible that if separate flavors were recorded, the results might differ. In addition, occasional e-cigarette users may be less likely to know if the e-cigarette products they used were flavored, potentially leading to misclassified responses.

Finally, there were small changes in the wording and placement of survey questions for certain tobacco products during 2014 to 2019. Prevalence estimates with similar definitions have been reported in other surveillance reports.2 Furthermore, some confounders that may affect the outcomes, such as peer use, household income, parental education, and socioeconomic status, were not asked in the NYTS.

Public Health Implications

The latest statistics from the 2020 NYTS data showed a drop in e-cigarette use among US youths, but the prevalence is still at an unacceptably high level, with about 1 in 5 high-school students (∼3 million) and 1 in 20 middle-school students (∼550 000) reporting current e-cigarette use.35 This study identified significant disparities in youth e-cigarette use across racial/ethnic groups. Non-Hispanic White youths were more likely to report frequent e-cigarette use and use of flavored products, while non-Hispanic Black adolescents were more likely to report occasional use of e-cigarettes and dual use of e-cigarettes and cigarettes or other tobacco products than their peers. Tailored, culturally relevant messaging and interventions may help address the racial/ethnic disparities in e-cigarette use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Research reported in this publication was supported by R21DA054818 (PI: H. Dai) from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and US Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products.

Note. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Food and Drug Administration.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no potential conflicts of interest.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

Institutional board review was not required for this study, as it was a secondary analysis of de-identified data.

REFERENCES

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services Preventing Tobacco Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gentzke AS, Creamer M, Cullen KA, et al. Vital Signs: Tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2011‒ 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. . 2019;68(6):157–164. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6806e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Miech R, Johnston L, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Patrick ME. Trends in adolescent vaping, 2017‒2019. N Engl J Med. . 2019;381(15):1490–1491. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1910739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Public Health Consequences of E-Cigarettes. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.US Department of Health and Human Services E-Cigarette Use Among Youth and Young Adults: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Qasim H, Karim ZA, Rivera JO, Khasawneh FT, Alshbool FZ. Impact of electronic cigarettes on the cardiovascular system. J Am Heart Assoc. . 2017;6(9):e006353. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. McConnell R, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wang K, et al. Electronic cigarette use and respiratory symptoms in adolescents. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. . 2017;195(8):1043–1049. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201604-0804OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.US Department of Health and Human Services Tobacco Use Among US Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups—African Americans, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and Hispanics: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.US Department of Health and Human Services The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang TW, Gentzke AS, Creamer MR, et al. Tobacco product use and associated factors among middle and high school students—United States, 2019. MMWR Surveill Summ. . 2019;68(12):1–22. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6812a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hartwell G, Thomas S, Egan M, Gilmore A, Petticrew M. E-cigarettes and equity: a systematic review of differences in awareness and use between sociodemographic groups. Tob Control. . 2017;26(e2):e85–e91. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Barrington-Trimis JL, Bello MS, Liu F, et al. Ethnic differences in patterns of cigarette and e-cigarette use over time among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. . 2019;65(3):359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Stokes AC, Wilson AE, Lundberg DJ, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in associations of non-cigarette tobacco product use with subsequent initiation of cigarettes in US youths. Nicotine Tob Res. . 2021;23(6):900–908. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sharapova S, Reyes-Guzman C, Singh T, Phillips E, Marynak KL, Agaku I. Age of tobacco use initiation and association with current use and nicotine dependence among US middle and high school students, 2014‒2016. Tob Control. . 2020;29(1):49–54. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Cancer Institute. 2017. https://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/22/monograph22.html

- 16. Glasser AM, Johnson AL, Niaura RS, Abrams DB, Pearson JL. Youth vaping and tobacco use in context in the United States: results from the 2018 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. . 2021;23(3):447–453. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Choi HJ, Yu M, Sacco P. Racial and ethnic differences in patterns of adolescent tobacco users: a latent class analysis. Child Youth Serv Rev. . 2018;84:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.11.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ambrose BK, Day HR, Rostron B, et al. Flavored tobacco product use among US youth aged 12‒17 years, 2013‒2014. JAMA. . 2015;314(17):1871–1873. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.13802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cullen KA, Liu ST, Bernat JK, et al. Flavored tobacco product use among middle and high school students—United States, 2014‒2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. . 2019;68(39): 839–844. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6839a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dai H. Changes in flavored tobacco product use among current youth tobacco users in the United States, 2014‒2017. JAMA Pediatr. . 2019;173(3):282–284. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.4595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/index.htm

- 22. Cullen KA, Ambrose BK, Gentzke AS, Apelberg BJ, Jamal A, King BA. Notes from the field: use of electronic cigarettes and any tobacco product among middle and high school students—United States, 2011‒2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. . 2018;67(45):1276–1277. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6745a5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gardiner PS. The African Americanization of menthol cigarette use in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. . 2004;6(suppl 1):S55–S65. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001649478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Landrine H, Klonoff EA. Racial segregation and cigarette smoking among Blacks: findings at the individual level. J Health Psychol. . 2000;5(2):211–219. doi: 10.1177/135910530000500211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Apelberg BJ, Corey CG, Hoffman AC, et al. Symptoms of tobacco dependence among middle and high school tobacco users: results from the 2012 National Youth Tobacco Survey. Am J Prev Med. . 2014;47(2, suppl 1):S4–S14. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Leventhal AM, Stone MD, Andrabi N, et al. Association of e-cigarette vaping and progression to heavier patterns of cigarette smoking. JAMA. . 2016;316(18):1918–1920. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.14649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dai H, Hao J. Flavored electronic cigarette use and smoking among youth. Pediatrics. . 2016;138(6):e20162513. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCabe SE, West BT, Veliz P, Boyd CJ. E-cigarette use, cigarette smoking, dual use, and problem behaviors among US adolescents: results from a national survey. J Adolesc Health. . 2017;61(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.US Food and Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/tobacco-products/retail-sales-tobacco-products/selling-tobacco-products-retail-stores

- 30.US Food and Drug Administration. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-finalizes-enforcement-policy-unauthorized-flavored-cartridge-based-e-cigarettes-appeal-children

- 31.US Food and Drug Administration. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-notifies-companies-including-puff-bar-remove-flavored-disposable-e-cigarettes-and-youth

- 32.US Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/demo/school-enrollment/2018-cps.html

- 33. Brener ND, Billy JO, Grady WR. Assessment of factors affecting the validity of self-reported health-risk behavior among adolescents: evidence from the scientific literature. J Adolesc Health. . 2003;33(6):436–457. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Office on Smoking and Health 2019 National Youth Tobacco Survey: Methodology Report. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang TW, Neff LJ, Park-Lee E, Ren C, Cullen KA, King BA. E-cigarette use among middle and high school students—United States, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. . 2020;69(37):1310–1312. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]