SUMMARY.

The Mississippi Flyway is of utmost importance in monitoring influenza A viral diversity in the natural reservoir, as it is used by approximately 40% of North American migratory waterfowl. In 2008, influenza A virus (IAV) surveillance was initiated in eight states within the flyway during annual southern migration, to gain better insight into the natural history of influenza A viruses in the natural reservoir. More than 45,000 samples have been collected and tested, resulting in hundreds of diverse influenza A viral isolates, but seasonal sampling may not be the best strategy to gain insight into the natural history of IAV. To investigate the progress of this sampling strategy toward understanding the ecology of IAV in wild waterfowl, data from mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) sampled nearly year-round in Ohio were examined. Overall, 3,645 samples were collected from mallards in Ohio from 2008 to 2016, with IAV being recovered from 13.6% of all samples collected. However, when data from each month are examined individually, it becomes apparent that the aggregated summary may be providing a misleading view of IAV in Ohio mallards. For instance, in August the frequency of viral recovery is 29.8%, with isolates representing at least 47 hemagglutinin/neuraminidase (HA/NA) combinations. In November, during the height of southern migration, IAV isolation drops to 6.2%, with only 25 HA/NA combinations being represented. Our biased sampling towards convenience and high IAV recovery has created gaps in the data set, which prohibit a full understanding of the IAV ecology in this waterfowl population.

Keywords: influenza A virus, wild waterfowl, Mississippi Migratory Flyway

RESUMEN.

La ruta migratoria de Mississippi es de suma importancia para monitorear la diversidad del virus de la influenza A en los reservorios naturales, ya que es utilizada por aproximadamente el 40% de las aves acuáticas migratorias de América del Norte. En el año 2008, se inició la vigilancia del virus de la influenza A (IAV) en ocho estados dentro de dicha ruta migratoria durante la migración anual al sur, para obtener una mejor comprensión de la historia natural de los virus de la influenza A en el reservorio natural. Se han recolectado y analizado más de 45,000 muestras, lo que dio como resultado cientos de diversos aislados virales de influenza A, pero el muestreo estacional puede no ser la mejor estrategia para conocer la historia natural del virus de la influenza aviar. Para investigar el progreso de esta estrategia de muestreo para comprender la ecología del virus de la influenza aviar en aves acuáticas silvestres, se examinaron datos de patos de collar (Anas platyrhynchos) muestreados durante casi todo el año en Ohio. En total, se recolectaron 3,645 muestras de patos silvestres en Ohio desde el año 2008 hasta el 2016, y se recuperó al virus de la influenza aviar en el 13.6% de todas las muestras recolectadas. Sin embargo, cuando los datos de cada mes se examinaron individualmente, se hace evidente que el resumen agregado puede proporcionar un panorama engañoso del virus de la influenza aviar en los patos silvestres de Ohio. Por ejemplo, en agosto, la frecuencia de recuperación viral fue del 29.8%, con aislamientos que representan al menos 47 combinaciones de hemaglutininas (HA) y neuraminidasas (NA). En noviembre, durante el apogeo de la migración hacia el sur, el aislamiento del virus de la influenza se redujo a 6.2%, con solo 25 combinaciones de HA y NA representadas. El muestreo sesgado hacia la conveniencia y la alta recuperación del virus de influenza ha creado brechas en el conjunto de datos, que prohíbe una comprensión completa de.

Influenza A viruses, of the family Orthomyxoviridae, infect a wide range of mammalian hosts, including humans, with human seasonal strains causing severe disease and thousands of human deaths each year (11,17) Wild waterfowl, especially from the order Anseriformes, have been identified as a natural reservoir for influenza A viruses and maintain a high level of viral diversity within the population (13,15,16,17). This diversity is characterized by two surface proteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), for which there are 16 and 9 unique subtypes, respectively (12,13). Nearly all potential HA/NA combinations have been identified in waterfowl; however, the mechanisms by which the viral diversity is maintained are still unclear (8,12,13) Many efforts are ongoing to improve the understanding of the natural history of influenza A viruses (IAV) in this natural reservoir (1,2,5).

The Mississippi Flyway is of significant importance in monitoring influenza A viral diversity in the natural reservoir, as it is used by approximately 40% of North American migratory waterfowl, and is home to more than 325 bird species (4). In the United States, the Mississippi flyway includes areas along the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast, administratively including Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Missouri, Kentucky, Arkansas, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. In 2008, influenza A virus surveillance was initiated in eight states within the flyway during annual southern migration to gain better insight into the natural history of influenza A viruses in the natural reservoir (5). More than 45,000 samples have been collected and tested, resulting in hundreds of diverse influenza A viral isolates, but seasonal surveillance may not be the best strategy to gain insight into the natural history of IAV. To investigate the progress of this sampling strategy toward understanding the ecology of IAV in wild waterfowl, data from mallard ducks (Anas platyrhynchos) sampled nearly year-round in Ohio were examined. Mallard ducks are known to be important in the ecology of IAVs; thus, understanding viral transmission in this population could lead to a better understanding of IAV ecology in other waterfowl species (3,7,9,10).

METHODS

Active surveillance was conducted at Winous Point Marsh Conservancy in Ohio, USA during summer–winter, 2008–2016. During spring and summer months (June–August), wild mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) ducks were live trapped during regulatory agency banding efforts (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Collection Permit MB66162B-0), and cloacal swabs were collected as previously described (5). During autumn and winter months, cloacal swabs were collected from hunter-harvested mallards with similar sample collection and storage methods. All samples were collected under The Ohio State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocol 2007A0148. IAVs were detected with the use of embryonated chicken egg isolation with previously described methods (5). Hemagglutinin and neuraminidase subtypes were determined by PCR and sequencing methods by the National Veterinary Service Laboratory (Ames, IA). Frequencies were tabulated and compared with the use of chi-square statics in SPSS (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

RESULTS

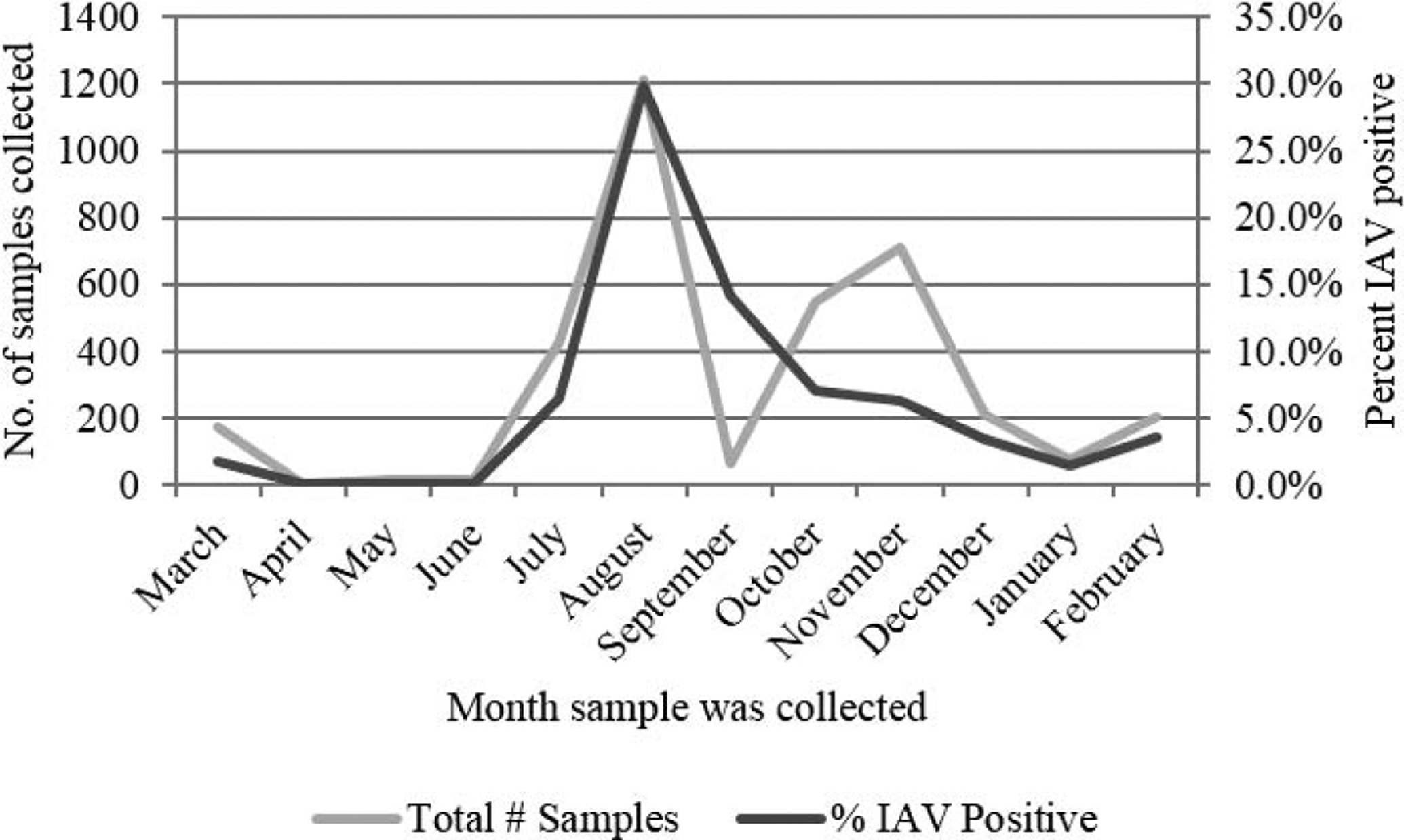

A total of 3645 cloacal samples were collected from 2008 to 2016 from mallard ducks using Ohio marshes, resulting in 497 (13.6%) IAV isolates. Samples were not evenly distributed across seasons, with the most samples being collected in summer (June–August) months (n = 1653) from live-trapped birds (Fig. 1). A total of 1322 samples were collected from hunter-harvested ducks in autumn (September–November), 485 samples were collected in winter (December–February), and 185 samples were collected from spring months (March–May). Similarly, the greatest number of influenza A virus isolates were recovered during summer (n = 388), followed by autumn (n = 91), winter (n = 15), and spring (n = 3). Diverse HA/NA subtypes were recovered with 41 unique, single HA/NA combinations being isolated through the duration of the study. In addition, 8.8% of all isolates recovered were determined to have mixed HA or NA subtypes. Subtype diversity also varied between seasons, with the most diversity being recovered during summer. However, four HA/NA subtypes (H3N9, H4N4, H7N7, and H11N3) would have been missed if sampling only occurred in the summer (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

The number of samples collected and percent that are positive for influenza A virus isolates, during each month. All samples collected from 2008–2016 are included.

Table 1.

Number of HA/NA subtypes recovered from both immature and mature ducks during each month of the study. All but four HA/NA subtype combinations were recovered during summer sampling (I is immature, and M is mature).

| Spring | Summer | Autumn | Winter | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| March | July | August | September | October | November | December | January | February | ||||||||||

| Subtype | I | M | I | M | I | M | I | M | I | M | I | M | I | M | I | M | I | M |

| H1N1 | 16 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| H1N2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H1N6 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H1N8 | 10 | 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| H2N2 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H2N3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||||||||

| H2N8 | 3 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H2N9 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H3N1 | 4 | |||||||||||||||||

| H3N2 | 15 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| H3N6 | 6 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| H3N8 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| H3N9 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H4N2 | 4 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H4N4 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H4N5 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| H4N6 | 2 | 18 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | |||||||||||

| H4N8 | 48 | 23 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| H4N9 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H5N1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H5N2 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||||||

| H6N1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||

| H6N2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| H6N4 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H6N9 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H7N3 | 6 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| H7N5 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H7N7 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H7N8 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||

| H8N4 | 2 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H9N2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H9N3 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H10N1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H10N3 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| H10N7 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| H10N8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||

| H11N2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||

| H11N3 | 1 | 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| H11N9 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | |||||||||||||

| H12N4 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| H12N5 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||

| Total | 1 | 1 | 25 | 11 | 168 | 45 | 6 | 1 | 16 | 7 | 29 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

As previously reported, the frequency of IAV isolation is significantly higher (P < 0.5) from immature ducks than what is recovered from mature ducks (3). A total of 2086 samples were collected from immature ducks, resulting in 379 (18.1%) IAV isolates. Mature ducks were sampled 1377 times with 112 (8.13%) isolates recovered. Age was not determined for 182 ducks, accounting for 6 of the IAV isolates recovered in the study. Subtype variation between the duck age groups is described in Table 1.

DISCUSSION

Mallard ducks have been studied extensively to understand influenza A virus ecology, and it is well established that they become infected with a diverse range of IAVs (7,9,10,18). Therefore, data from mallard ducks sampled nearly year-round at one location in Ohio was used to gain insight into the effectiveness of IAV surveillance efforts in the Mississippi Migratory Flyway. Aggregation of mallard data identifies an overall frequency of viral recovery of 13.6%; however, when data from each month are examined individually, it is apparent that the aggregated summary may be providing a misleading view of IAV in Ohio mallards. For example, if only data from August are reported, frequency is 29.8% (n = 361) representing 32 HA/NA subtypes. In contrast, reporting only November data shows a different picture of IAV in mallards, with a 6.2% (n = 44) frequency of viral recovery, including 17 HA/NA subtype combinations. In addition to seasonality differences in viral recovery and subtype diversity, there is variance in isolation and diversity based on the age of the duck (3,18). If sampling had occurred only in 1 mo of the year, conclusions could misrepresent what is occurring within the ducks at that specific location.

Accounting for these changes could be the dynamics of mallard populations throughout the year at this site and their interactions with other bird species. Samples collected from January to August were from resident ducks who use the Lake Erie basin as their breeding grounds. The number of ducks using this area to breed varies greatly between years, depending on weather conditions, with bird counts ranging from zero to >10,000 per winter within the study population (Shirkey, personal communication). An influx of migrating ducks occurs in late summer/early fall (September–October); however, mallard ducks are not sampled during this time because hunting is not permitted.

Subtype diversity shifts are likely attributed to the changes in the population from only resident mallards and wood ducks using the area during summer, to several duck species using the area as a stopover during autumn migration. Viruses with a HA/NA subtype H4N8 are the predominantly isolated strains during the summer months, when only resident ducks are being sampled. In contrast, once the migrants have arrived, the predominately isolated subtype in the study in the autumn was H5N2. Subtype differences based on seasonality have been seen by other investigators and warrant further investigation (14).

A majority of surveillance conducted by this research team throughout the Mississippi Flyway is not across multiple months of the year, as is done in Ohio, but rather occurs once or twice within the localities’ hunting seasons. Determining differences in IAV ecology within the Ohio mallards depending on the time of sampling points out the importance of longitudinal sampling at one location, if conclusions are to be drawn regarding IAV ecology in that location. In addition, subtype diversity may not be well represented for underrepresented study sites if sampling occurred when birds were not at peak viral shedding. Misinterpreting viral diversity within a location could lead to invalid conclusions being drawn when phylogenetic analysis occurs downstream. Collecting samples from the same population of ducks as they migrate down the Mississippi Flyway can reduce the risk of misinterpretation because viral diversity is captured at various locations.

Continued wild bird surveillance is important to understand viral diversity fully and to identify virus strains that may pose risk to human and animal health. However, our biased sampling towards convenience and high IAV recovery has created gaps in the data set, which prohibit a full understanding of the IAV ecology in the waterfowl population using the Mississippi Flyway. But how do we better understand the ecology of IAVs? Altering surveillance efforts to ask specific questions could help fill these gaps in the knowledge base. First, surveillance has not been conducted in mallards during several months of the year within Ohio, which is the richest data set within this repository. Filling the gaps of surveillance during undersampled seasons and unsampled months could allow investigators to understand how viral diversity is maintained within this specific population of ducks. Perhaps there are niche species that are underrepresented in current surveillance programs, which may be identified by observing the behavior of mallards in Ohio, leading to the inclusion of these species in surveillance efforts. Viral diversity within mallards may be driven by the viral isolates that are maintained in other species and merely amplified by susceptible mallards (6,9). This could also explain the mechanisms that drive viral diversity across seasons. Answering these questions in mallards at one location could shape the future direction of wild bird IAV surveillance in other locations to gain understanding in the natural history of IAVs in a natural reservoir.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank all personnel at Winous Point Marsh Conservancy for their continued support of field efforts associated with this surveillance. In addition, we thank the National Veterinary Service Laboratory for completing HA/NA subtyping for all isolates included in this study. This work was supported by the Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); National Institutes of Health (NIH); Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), contract HHSN272201400006C.

Abbreviations:

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IAV

influenza A virus

- NA

neuraminidase

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown JD, Luttrell MP, Uhart MM, del Valle Ferreyra H, Romano MM, Rago MV, and Stallknecht DE. Antibodies to type A influenza virus in wild waterbirds from Argentina. J. Wildl. Dis 46:1040–1045. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown JD, and Stallknecht DE. Wild bird surveillance for the avian influenza virus. Methods Mol. Biol 436:85–97. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Costa TP, Brown JD, Howerth EW, and Stallknecht DE. The effect of age on avian influenza viral shedding in mallards (Anas platyrhynchos). Avian Dis 54:581–585. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elphrick J The atlas of bird migration; tracing the great journeys of the world’s birds Struik, Johannesburg, South Africa. 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fries AC, Nolting JM, Bowman AS, Lin X, Halpin RA, Wester E, Fedorova N, Stockwell TB, Das SR, Dugan VG, Wentworth DE, Gibbs HL, and Slemons RD. Spread and persistence of influenza a viruses in waterfowl hosts in the North American Mississippi migratory flyway. J. Virol 89:5371–5381. 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hill NJ, Takekawa JY, Ackerman JT, Hobson KA, Herring G, Cardona CJ, Runstadler JA, and Boyce WM. Migration strategy affects avian influenza dynamics in mallards (Anas platyrhynchos). Mol. Ecol 21:5986–5999. 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jourdain E, Gunnarsson G, Wahlgren J, Latorre-Margalef N, Brojer C, Sahlin S, Svensson L, Waldenstrom J, Lundkvist A, and Olsen B. Influenza virus in a natural host, the mallard: experimental infection data. PLoS One 5:e8935. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krauss S, Walker D, Pryor SP, Niles L, Chenghong L, Hinshaw VS, and Webster RG. Influenza A viruses of migrating wild aquatic birds in North America. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 4:177–189. 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Latorre-Margalef N, Gunnarsson G, Munster VJ, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, Elmberg J, Olsen B, Wallensten A, Haemig PD, Fransson T, Brudin L, and Waldenström J. Effects of influenza A virus infection on migrating mallard ducks. Proc. Biol. Sci 276:1029–1036. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Latorre-Margalef N, Tolf C, Grosbois V, Avril A, Bengtsson D, Wille M, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA, Olsen B, and Waldenstrom J. Long-term variation in influenza A virus prevalence and subtype diversity in migratory mallards in northern Europe. Proc. Biol. Sci 281:20140098. 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molinari NA, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Messonnier ML, Thompson WW, Wortley PM, Weintraub E, and Bridges CB. The annual impact of seasonal influenza in the US: measuring disease burden and costs. Vaccine 25:5086–5096. 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Munster VJ, Veen J, Olsen B, Vogel R, Osterhaus AD, and Fouchier RA. Towards improved influenza A virus surveillance in migrating birds. Vaccine 24:6729–6733. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsen B, Munster VJ, Wallensten A, Waldenström J, Osterhaus AD, and Fouchier RA. Global patterns of influenza A virus in wild birds. Science 312:384–388. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramey AM, Walther P, Link P, Poulson RL, Wilcox BR, Newsome G, Spackman E, Brown JD, and Stallknecht DE. Optimizing surveillance for South American origin influenza A viruses along the United States Gulf Coast through genomic characterization of isolates from blue-winged teal (Anas discors). Transboundary Emerging Dis 63:194–202. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Slemons RD, and Easterday BC. The natural history of type A influenza viruses in wild waterfowl. In: Third International Wildlife Disease Conference Page LA, ed. Plenum Press, New York. pp. 215–224. 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Slemons RD, and Easterday BC. Type-A influenza viruses in the feces of migratory waterfowl. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc 171:947–948. 1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Webster RG, Bean WJ, Gorman OT, Chambers TM, and Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol. Rev 56:152–179. 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilcox BR, Knutsen GA, Berdeen J, Goekjian V, Poulson R, Goyal S, Sreevatsan S, Cardona C, Berghaus RD, Swayne DE, Yabsley MJ, and Stallknecht DE. Influenza-A viruses in ducks in northwestern Minnesota: fine scale spatial and temporal variation in prevalence and subtype diversity. PLoS One 6:e24010. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]