Abstract

Polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) are compounds with a minimum of two 6-atom aromatic fused rings. PACs arise from incomplete combustion or thermal decomposition of organic matter and are ubiquitous in the environment. Within PACs, carcinogenicity is generally regarded to be the most important public health concern. However, toxicity in other systems (reproductive and developmental toxicity, immunotoxicity) has also been reported. Despite the large number of PACs identified in the environment, research attention to understand exposure and health effects of PACs has focused on a relatively limited subset, namely, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), the PACs with only carbon and hydrogen atoms. To triage the rest of the vast number of PACs for more resource-intensive testing, we developed a data-driven approach to contextualize hazard characterization of PACs, by leveraging the available data from various data streams (in silico toxicity, in vitro activity, structural fingerprints, and in vivo data availability). The PACs were clustered based on their in silico toxicity profiles containing predictions from 8 different categories (carcinogenicity, cardiotoxicity, developmental toxicity, genotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, and urinary toxicity). We found that PACs with the same parent structure (e.g., fluorene) could have diverse in silico toxicity profiles. In contrast, PACs with similar substituted groups (e.g., alkylated-PAHs) or heterocyclics (e.g., N-PACs) with varying ring sizes could have similar in silico toxicity profiles, suggesting that these groups are better candidates for toxicity read-across analysis. The clusters/regions associated with certain in silico toxicity, in vitro activity, and structural fingerprints were identified. We found that genotoxicity/carcinogenicity (in silico toxicity) and xenobiotic homeostasis and stress response (in vitro activity), respectively, dominate the toxicity/activity variation seen in the PACs. The “hot spots” with enriched toxicity/activity in conjunction with availability of in vivo carcinogenicity data revealed regions of either data-poor (hydroxylated-PAHs) or data-rich (unsubstituted, parent PAHs) PACs. These regions offer potential targets for prioritization of further in vivo assessment and for chemical read-across efforts. The analysis results are searchable through an interactive web application (https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/pacs_tableau), allowing for alternative hypothesis generation.

Keywords: polycyclic aromatic compound (PAC), Tox21, new approach methodology (NAM), data science, in silico toxicity profile

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Polycyclic aromatic compounds (PACs) are a structurally-diverse class of organic compounds. They are ubiquitous environmental contaminants that arise from incomplete combustion or thermal decomposition of organic matter. Exposure to PACs is almost never to a single chemical, but to complex and dynamic mixtures, and can occur from various sources and through different routes. Examples of possible exposure scenarios include dermal exposure in occupational settings such as roofing and paving 1, oral exposure through consumption of smoked or chargrilled foods2, or inhalation exposure via traffic pollution3. Carcinogenicity is generally regarded to be the most important public health concern associated with PACs4,5. However, individual PACs (e.g., benzo(a)pyrene) have also been linked to multiple health effects including reproductive6,7 and developmental toxicity8, neurotoxicity9, and immunotoxicity10.

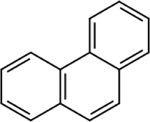

The defining feature of the PAC class is the presence of two or more fused aromatic rings, with polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH) limited to structures containing carbon and hydrogen atoms. PACs also include heterocyclics (a cyclic compound that has nitrogen, oxygen, or sulfur atoms in addition to the carbon atoms, as members of its ring(s)) and/or ring structures containing substituted functional groups (e.g., N-, S-, or O-substituted PAHs). The structural features that define the PAC class are straightforward, allowing for a great number of structural configurations. Research attention dedicated to understanding exposure and health effects has focused on a relatively limited subset of PAHs within the PAC class. In fact, the majority of work to understand the risk from exposure to PACs involves the 16 PAHs on the US EPA Priority Pollutant List11, with benzo(a)pyrene serving as a prototype for the class and receiving the most scrutiny.

Evaluation of human health risk from PAC exposure relies heavily upon the Provisional Guidance for Quantitative Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons5. The Relative Potency Factor (RPF) method is used to calculate risk, by using the carcinogenicity data of benzo(a)pyrene as the reference for comparison5. Many uncertainties and challenges are involved in this approach12. Importantly, carcinogenicity is assumed to be the most sensitive endpoint for all PACs and other toxicities are not considered. To improve risk evaluation of PACs, the National Toxicology Program (NTP) developed a research plan, PAC Mixtures Assessment Program (PAC MAP) (https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/PACs). The PAC MAP has three aims: 1) to expand the number and structural diversity of PACs evaluated in multiple exposure contexts, 2) to use novel approach methodologies (NAMs) to screen a diverse array of PACs for hazard characterization, and 3) to evaluate the assumptions used in the current risk assessment paradigm for PACs. Toward the final aim, the NTP is currently evaluating 13 individual PACs and defined mixtures comprised of those PACs in 28-day immunotoxicity dose-response studies in B6C3F1/N mice. The connection between immune suppression and carcinogenicity has been recommended as an avenue to explore for improving cancer risk assessment for PAC mixtures13.

The work described herein is part of the hazard characterization aim of the PAC MAP. Data generated under this aim will increase the biological understanding of PACs. Both predicted and experimental data across various biological endpoints were surveyed. Data from this effort can be used to prioritize individual PACs for possible in vivo assessment and contribute to our mechanistic understanding of PAC toxicity. In the first phase of this work, we created a computational workflow to identify PACs from a chemical library (in our case, the Tox21 library, which contains over 9,000 unique chemical structures)14. We clustered PAC chemicals based on the similarity between their in silico toxicity profiles, covering eight different categories of toxicity. We then identified the features, including structures and in silico/in vitro biological endpoints, that were associated with PAC clusters. A web application hosting the data is accessible at https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/pacs_tableau.

Materials and Methods

Minimal requirement of PAC characteristics

The starting definition of a PAC requires the chemical structure to have at least two fused rings with a minimum of two 6-atom aromatic rings (base structure). According to this definition, naphthalene (DTXSID8020913) represents the smallest PAC. In addition to the PACs containing only carbon and hydrogen atoms and lacking substitutions (a.k.a. “parent” or PAH), two other classes of PACs were also included: heterocyclic and substituted. The “heterocyclic” PACs are compounds with a PAC base structure but having nitrogen, oxygen, and/or sulfur atom(s) within the fused rings (e.g., phenothiazine, DTXSID5021126). The “substituted” PACs are compounds with a PAC base structure but having functional groups attached to the base structure (e.g., 1-hydroxypyrene, DTXSID1038298). If a PAC has both features of heterocyclic and substituted, it is categorized as a heterocyclic PAC (e.g., quazodine, DTXSID4046232).

Collection of PACs in the Tox21 compound library

To automatically collect PACs in the Tox21 chemical structure library (INVITRODBV3_20181017_v2000.sdf) and label them according to the three classes (parent, heterocyclic, and substituted), the definition of PAC was coded into a set of SMILES arbitrary target specification (SMARTS) queries. Based on the SMARTS queries, the KNIME workflows were developed (https://www.knime.com/, version 3.7) so that other chemical libraries can be used as the input. The KNIME workflows are available in the Supplemental File S1.

Defining the boundaries of the PAC class

Since there is no a priori limitation on the size of the substituted functional groups on the base structures, the identified PACs could theoretically have very diverse or long substituted groups. Although those compounds would still meet the minimum requirement of PAC characteristics, the designation would be meaningless without any boundaries (e.g., buquinolate, DTXSID1041689) since the primary biological interactions may not involve the PAH structure. Therefore, we devised an approach for determining boundaries of the PAC class. The first step was to identify PACs in each of the three categories that could be used as ‘reference PACs’. The reference PACs were selected from the pool of PACs meeting the minimum requirement by NTP chemists with experience in PAC chemistry, to reflect “typical” PACs in each category (i.e., PACs that are commonly associated with each PAC category – parent, heterocyclic, and substituted). Next, physicochemical properties of PACs that meet the minimum requirement (see above) were converted to distance measures from the reference PACs. The physicochemical properties (n = 29), including SlogP, SMR, LabuteASA, TPSA, AMW, ExactMW, NumLipinskiHBA, NumLipinskiHBD, NumRotatableBonds, NumHBD, NumHBA, NumAmideBonds, NumHeteroAtoms, NumHeavyAtoms, NumAtoms, NumStereocenters, NumUnspecifiedStereocenters, NumRings, NumAromaticRings, NumSaturatedRings, NumAliphaticRings, NumAromaticHeterocycles, NumSaturatedHeterocycles, NumAliphaticHeterocycles, NumAromaticCarbocycles, NumSaturatedCarbocycles, NumAliphaticCarbocycles, FractionCSP3, HallKierAlpha, were calculated using the RDKit node in KNIME (3.4.0.v201807311105) with de-salted SMILES of PACs. The similarity cutoff was determined using the mean plus 1 standard deviation (SD) from the distribution of the pairwise Euclidean distance of properties (after range-scaled normalization) of the reference PACs in each class. Non-reference PACs with Euclidean distance to any of the reference PACs smaller than the similarity cutoff in each class were included – along with the reference PACs - for the following analyses. The cutoff was selected after review of the excluded and included list. The list of PACs can be found in Supplemental File S2.

PACs under NTP in vivo immunotoxicity testing

Thirteen PACs are currently being evaluated in 28-day immunotoxicity and gene expression studies in female B6C3F1/N mice. Ten out of the 13 are available in the Tox21 compound library, and they include 8 parent PACs (pyrene, benzo(a)pyrene, indeno[1,2,3-cd]pyrene, chrysene, phenanthrene, dibenz[a,h]anthracene, benzo(b)fluoranthene, benzo(k)fluoranthene), 1 heterocyclic PAC (dibenzothiophene), and 1 substituted PAC (acenaphthenequinone). The 3 PACs that were not included in the Tox21 library are 3 parent PACs: dibenzo[def,p]chrysene (a.k.a. dibenzo[a,l]pyrene), 7H-benzo[c]fluorene, and benz(j)aceanthrylene. Their SMILES were retrieved by Chemical Abstracts Service Registry Number (CASRN) through the EPA Chemical Dashboard (https://comptox.epa.gov/dashboard, accessed on April 24th, 2019).

In silico toxicity profiling of PACs

PACs were profiled for predicted biological activity using in silico toxicity from Leadscope quantitative structure activity relationship (QSAR) models (http://www.leadscope.com/model_appliers/). The Leadscope QSAR models were trained using Leadscope proprietary structural fingerprints and curated data from government agencies15. For our analysis, only models with balanced accuracy > 0.7 were used in the calculation. In total, 40 QSAR models were used (see descriptions below). The QSAR-ready SMILES of PACs downloaded from the EPA Chemical Dashboard were used as the input for the models to get predicted probabilities of an activity occurring (value from 0 to 1) and activity calls (positive or negative). To preserve a complete data matrix, instead of dropping out the out-of-applicability-domain predictions, their values were replaced using the average probability value from all the predictions with negative calls in the respective model. This imputing approach deliberately emphasizes positive activity signals and is similar to methods reported in several other studies16–18.

The 40 QSAR models can be categorized into 15 different toxicological effects, covering 8 different toxicity categories (carcinogenicity, cardiotoxicity, developmental toxicity, genotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, and urinary toxicity) (Table 1). The predicted probability values in models of each of the 15 categories were aggregated: the maximum predicted probability in each category was reported. The probability values in these 15 toxicological categories served as a toxicity profile for each compound to be used in calculating the similarity between PACs. Due to the lack of robust data for the effects of PACs on immune endpoints, immunotoxicity was not included in the categories comprising the toxicity profiles. However, immune modulation is known to play an important role in cancer development19. Both carcinogenicity and immunotoxicity of PACs occur via complex and intersecting molecular pathways4.

Table 1.

The list of 15 toxicological effects predicted by QSAR models

| level3 | level2 | level1 | # of models in level 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mammalian Cell Transformation | Carcinogenicity in Vitro | Carcinogenicity | 2 |

| Rodent Carcinogencity | Carcinogenicity in Vivo | Carcinogenicity | 1 |

| Human Adverse Cardiological Effects | Cardiatoxicity in Vivo | Cardiactoxicity | 9 |

| Rodent Pre-implantation Loss | Fetal Survival | Developmental Toxicity | 1 |

| Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations | Clastogenicity in Vitro | Genotoxicity | 2 |

| Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation | Gene Mutation in Vitro | Genotoxicity | 2 |

| Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE) | Clastogenicity in Vitro | Genotoxicity | 1 |

| Microbe Gene Mutation | Gene Mutation in Vitro | Genotoxicity | 4 |

| Rodent Gene Mutation | Gene Mutation in Vivo | Genotoxicity | 2 |

| Rodent Micronucleus | Clastogenicity in Vivo | Genotoxicity | 1 |

| Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects | Hepatotoxicity in Vivo | Hepatotoxicity | 3 |

| Rodent Newborn Behavior | Neurotoxicity in Vivo | Neurotoxicity | 3 |

| Rodent Reproductive Adverse Effect | Reproductive Toxicity in Vivo | Reproductive Toxicity | 4 |

| Rodent Sperm Abnormality | Reproductive Toxicity in Vivo | Reproductive Toxicity | 2 |

| Adverse Urinary Effects | Urinary Toxicity in Vivo | Urinary Toxicity | 3 |

PAC clustering

The similarity between PACs based on in silico toxicity profiles was calculated using Euclidean distance. We clustered PACs based on their in silico toxicity profiles, using the hierarchical density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (HDBSCAN)20 (Python hdbscan, v0.8.1). The Euclidean distance between pairs of PACs was used as the input for HDBSCAN. The minimum cluster size (min_cluster_size) was set to 3 PACs and the minimum number of samples (min_samples) was set to 1 PAC to generate the clusters. The parameters were selected to minimize the number of PACs in the ‘noise’ category. The HDBSCAN output, including cluster membership probability, cluster persistence score, and cluster identification, were kept for further analyses. The HDBSCAN results can be found in Supplemental File S3.

Property association analysis

Each cluster produced by HDBSCAN included compounds that had similar in silico toxicity profiles. To understand if there were properties associated with each cluster, Fisher’s exact test was applied (R, exact2×2, v1.6.3) with the alternative hypothesis as “true odds ratio is greater than 1” using three datasets. The three datasets were 1) in silico toxicity: the positive/negative call in 15 toxicological categories binarized using the predicted probability value (cutoff = 0.5), 2) Tox21 in vitro activity: active/inactive call (assay interference as inactive) of 37 targets (e.g., activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor) from Tox21 quantitative high throughput (qHTS) assays21, and 3) structural fingerprints: presence/absence of 728 ToxPrint fingerprints (originally 729 but one was excluded because it was not present in any of the PACs)22. The association analysis was used to determine whether there was an association between the positive event (positive, active, presence) and the cluster identity. The property was considered associated with the respective cluster if the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval of the odds ratio was larger than 1 in the Fisher’s exact test or all PACs in the cluster had the respective property. The p-value and the adjusted p-value based on Holm correction were also reported. The Holm correction was applied on all p-values from Fisher’s exact test of property-cluster contingency tables per property category. The association analyses results can be found in Supplemental File S3.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of activity profiles

The in silico toxicity profile and in vitro activity profile were used separately as the input for PCA (R, FactoMineR, v1.42)23. The input value is the predicted probability processed as mentioned before and the negative logarithm (base 10) of the point-of-departure (POD). For the missing values of the Tox21 activity matrix (inactive and non-tested), a value of 0 was used. In this data matrix, 9.2% of the values were non-tested. The cause of non-tested value is due to the switching of the compound library after replenishing the compound plates. Classifying non-tested values as inactive was based on the observation that, generally, there is a low percentage of active values in HTS screenings24. The correlation of the input variables to the new dimensions and quality of the representation of variables on the new dimensions were obtained through PCA.

PAC visualization in in silico toxicity space

The relationship between PACs based on their in silico toxicity profiles in 2-dimensional (2D) space was visualized using the Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection, UMAP (R package, umap, v0.2.2) with Euclidean distance between pairs of PACs as the input. The UMAP is a non-linear neighbor graph-based dimension reduction algorithm25. It is similar to the antecedent t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) approach, but with improved calculation speed and overall performance. In non-mathematical terms, it constructs a high dimensional graphic representation of the data then optimizes a low-dimensional graph to be as structurally similar as possible. In the high-dimensional graph, the likelihood of connection of points is dependent on each point’s nearest neighbors (local environment). Once the high-dimensional graph is constructed, UMAP optimizes the layout of a low-dimensional analogue to be as similar as possible.

Study counts of in vivo data

The CASRN of the 329 PACs were used as the input to search for available in vivo data in the Leadscope® SAR Carcinogenicity Database and Leadscope® Toxicity Database. The in vivo data in these databases were curated from the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN). For carcinogenicity data, in addition to the above sources, data from NTP, Chemical Carcinogenesis Research Information System (CCRIS), and Carcinogenicity Potency Database (CPDB) were also used.

Interactive online application

Tableau Software (https://www.tableau.com/, v2019.1), particularly Tableau Desktop, was used to develop the interactive application. The embedded code of the deployed application (“viz”) was inserted into an HTML page hosted by NTP.

Results

Tox21 PAC collection

The PAC characteristics were coded into SMARTS queries and used in the KNIME workflows (Figure 1a and Supplemental File S1). Using the KNIME workflows and the Tox21 library as the structural input, we identified a total of 443 PACs in the Tox21 library (n = 8962), including 20 parent PACs, 186 substituted PACs, and 237 heterocyclic PACs. From 443 PACs, 49 (10 parent, 12 heterocyclic, and 27 substituted PACs) were selected as the reference PACs. The non-reference PACs that were dissimilar to the reference PACs based on physicochemical properties per class (see Methods) were excluded, and a total of 326 PACs were selected for further analysis. These structures consist of 20 parent PACs (reference/non-reference: 10/10), 150 heterocyclic PACs (12/138), and 156 substituted PACs (27/129). The percentage of PACs included in the analyses was 100% (parent), 83.9% (substituted), 63.3% (heterocyclic), respectively. The PACs, in addition to other Tox21 compounds, were visualized in 2D space by PCA based on the range-scaled-normalized physicochemical properties (Figure 1b and 1c). Many of the excluded PACs (open circles with color) were clearly distant from the reference PACs (solid triangle symbols).

Figure 1.

The collection of PACs from the Tox21 compound library. a) A flowchart to illustrate the process of collecting and categorizing PACs into three classes: parent, substituted, and heterocyclic. b) Tox21 compounds (including PACs, colored points) in the 2D principal component space based on physicochemical properties. c) A zoom-in from b) to highlight the selected PACs. The reference PACs (solid, colored triangles) were used to select some of the non-reference PACs which are more similar to the reference PACs (solid, colored circles). The hollow colored circles are the excluded PACs. The solid gray circles represent Tox21 compounds that did not meet the definition for consideration as PACs.

PAC clustering using in silico toxicity profiles

For 329 PACs (326 in Tox21 + 3 not in Tox21 but included in immunotoxicity testing), the predicted probabilities against 40 Leadscope QSAR models were aggregated into 15 toxicological effects (see Methods). The vector of 15 toxicological effects served as the in silico toxicity profile for each PAC. The 15-dimension in silico toxicity profile matrix (329 × 15) was the input for the following UMAP and HDBSCAN analyses. In this data matrix, the percentage of out-of-domain predictions was 35%. Figure 2a shows the similarity between PACs in two dimensions after UMAP analysis. Based on similarity of their toxicity profiles, PACs were clustered using the HDBSCAN clustering algorithm (Figure 2b, “PAC grouping”). The representative PAC based on the highest membership probability for each cluster is listed in Table 2.

Figure 2:

The PACs in 2D UMAP space based on in silico toxicity profiles. a) PACs in the in silico toxicity space colored based on their class (parent, substituted, or heterocyclic). b) PACs in the in silico toxicity space colored based on the clustering results from HDBSCAN using in silico toxicity profiles. The PACs that cannot be clustered with others (singletons) are shown as gray points. The cluster ID is shown as text next to its corresponding cluster.

Table 2.

The composition of the PAC clusters

| Cluster ID | # PACs in Cluster | Cluster Persistence Score | Representative PAC (Name) | Representative PAC (DSSTOXID) | # reference PACs | # PACs in In Vivo testing | PAC type (#) (parent|substituted|heterocyclic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (singleton) | 132 | NA | 1,4-Dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | DTXSID0037730 | 15 | 2 | 4|65|63 |

| 1 | 4 | 0.5035 | Benzo(a)pyrene | DTXSID2020139 | 3 | 3 | 4|0|0 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.0048 | 2,4,6-Trimethylpyridinium p-toluenesulfonate | DTXSID2058702 | 0 | 0 | 0|1|2 |

| 3 | 9 | 0.0050 | Zaltoprofen | DTXSID0049076 | 0 | 0 | 0|5|4 |

| 4 | 4 | 0.0246 | Isobutyl 2-naphthyl ether | DTXSID1051484 | 1 | 0 | 0|3|1 |

| 5 | 3 | 0.0407 | Imipramine | DTXSID1043881 | 0 | 0 | 0|0|3 |

| 6 | 6 | 0.0604 | Chrysene | DTXSID0022432 | 3 | 2 | 6|0|0 |

| 7 | 13 | 0.0118 | Chlorpromazine | DTXSID0022808 | 0 | 0 | 0|1|12 |

| 8 | 3 | 0.0109 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-4-methylcoumarin | DTXSID0025078 | 0 | 0 | 0|0|3 |

| 9 | 3 | 0.0233 | Umbelliferone | DTXSID5052626 | 0 | 0 | 0|0|3 |

| 10 | 8 | 0.0273 | Proflavin hemisulfate | DTXSID4043777 | 1 | 0 | 0|4|4 |

| 11 | 3 | 0.0396 | Anthraquinone | DTXSID3020095 | 1 | 0 | 0|3|0 |

| 12 | 4 | 0.0201 | Purpurin | DTXSID4021214 | 0 | 0 | 0|4|0 |

| 13 | 5 | 0.3211 | Methylene blue | DTXSID0023296 | 0 | 0 | 0|2|3 |

| 14 | 10 | 0.0272 | 9-Ethylcarbazole | DTXSID1052585 | 2 | 1 | 1|3|6 |

| 15 | 3 | 0.0003 | 1-Amino-2,4-dibromoanthraquinone | DTXSID4039235 | 1 | 0 | 0|3|0 |

| 16 | 9 | 0.0333 | 1,5-Naphthalenedisulfonic acid, disodium salt hydrate | DTXSID0044315 | 0 | 0 | 0|9|0 |

| 17 | 4 | 0.0547 | 6-Amino-4-hydroxynaphthalene-2-sulfonic acid | DTXSID0026547 | 0 | 0 | 0|4|0 |

| 18 | 5 | 0.0314 | Trioxsalen | DTXSID3023716 | 0 | 0 | 0|0|5 |

| 19 | 8 | 0.0206 | 2,6-Dimethylnaphthalene | DTXSID0029187 | 1 | 0 | 0|6|2 |

| 20 | 3 | 0.0011 | 3-Methylcholanthrene | DTXSID0020862 | 1 | 0 | 0|3|0 |

| 21 | 6 | 0.0588 | 1-Methylpyrene | DTXSID0025654 | 1 | 0 | 0|6|0 |

| 22 | 4 | 0.0356 | Cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride | DTXSID2045105 | 0 | 0 | 0|3|1 |

| 23 | 7 | 0.0148 | 6-Hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | DTXSID3029312 | 3 | 0 | 0|4|3 |

| 24 | 4 | 0.5137 | 2,3-Dichloroquinoxaline | DTXSID1025013 | 0 | 0 | 0|0|4 |

| 25 | 3 | 0.0030 | 9-Anthracenemethanol | DTXSID1049221 | 2 | 0 | 0|3|0 |

| 26 | 3 | 0.0002 | Bretylium tosylate | DTXSID1022685 | 0 | 0 | 0|3|0 |

| 27 | 3 | 0.0280 | 6-Nitroquinoline | DTXSID1020984 | 1 | 0 | 0|1|2 |

| 28 | 5 | 0.6002 | Benzo(k)fluoranthene | DTXSID0023909 | 0 | 2 | 3|0|2 |

| 29 | 4 | 0.0334 | Dibenzothiophene | DTXSID0047741 | 1 | 1 | 0|1|3 |

| 30 | 6 | 0.2127 | Dizocilpine maleate | DTXSID2045785 | 0 | 0 | 0|0|6 |

| 31 | 6 | 0.0231 | 2-Hydroxyanthraquinone | DTXSID4049327 | 1 | 0 | 0|6|0 |

| 32 | 7 | 0.0374 | 4,7-Dichloroquinoline | DTXSID0052590 | 0 | 0 | 0|0|7 |

| 33 | 4 | 0.0542 | Pyrene | DTXSID3024289 | 2 | 2 | 4|0|0 |

| 34 | 8 | 0.1907 | 1,5-Dinitronaphthalene | DTXSID4025165 | 4 | 0 | 0|8|0 |

| 35 | 3 | 0.0238 | 2-Naphthalenol | DTXSID5027061 | 1 | 0 | 0|2|1 |

| 36 | 4 | 0.0309 | Acenaphthene | DTXSID3021774 | 2 | 0 | 1|3|0 |

| 37 | 3 | 0.0036 | Quinoline | DTXSID1021798 | 1 | 0 | 0|0|3 |

| 38 | 4 | 0.0487 | 8-Hydroxyquinoline citrate | DTXSID1040326 | 1 | 0 | 0|0|4 |

| 39 | 3 | 0.0456 | 6-Methylquinoline | DTXSID3020887 | 0 | 0 | 0|0|3 |

In total, there were 39 clusters generated and 40% of PACs (132/329) were considered as singletons (i.e., noise) that could not be grouped with others. Both substituted and heterocyclic PACs had about 40% of compounds not included in clusters. The largest cluster included 13 compounds and the median size of the clusters was 4. Some clusters have highly similar in silico toxicity profiles among the members of the cluster (as indicated by high cluster persistence scores), such as Cluster Id = 28 (rep., benzo(k)fluoranthene), Cluster Id = 1 (rep., benzo(a)pyrene), and Cluster Id = 24 (rep., 2,3-dichloroquinoxaline).

PACs with PAH structures

The PACs with a certain basic parent ring structure are highlighted in Figure 3a–3e: acenaphthylene (n = 12), fluorene (n = 11), pyrene (n = 11), anthracene (n = 24), and phenanthrene (n = 30). Over 50% of the PACs with the fluorene structure had more unique in silico toxicity profiles (i.e., not included in clusters) and their in silico toxicity profiles tended to be more diverse (i.e., distant to each other on the map) than PACs with other parent ring structures. More scattered positive calls could be seen among the PACs with the fluorene structure (Supplemental Figure S1). In contrast, almost all the PACs with the pyrene structure were included in clusters and were located closer to each other, indicating that PACs with the pyrene structure in this dataset had similar in silico toxicity profiles.

Figure 3.

Examples of PACs highlighted on the UMAP space based on in silico toxicity profiles. PACs with selected parent structures, including acenaphthylene (a), fluorene (b), pyrene (c), anthracene (d), phenanthrene (e), are colored based on clustering results from HDBSCAN using in silico toxicity profiles. PACs that cannot be clustered with others but have the corresponding parent structure are shown as black points. f) PACs colored based on clustering results; same plot as Figure2b duplicated for comparison with a) - e).

Toxicological and structural properties associated with clusters

To understand whether there are toxicological and structural properties associated with each cluster, we conducted Fisher’s exact test using three datasets and the results are shown below. For each cluster, the associated properties, based on a) in silico toxicity; b) in vitro activities; c) ToxPrint structural fingerprints, were identified (see Methods) and are shown in Table 4. Examples and summary results are shown on the map (Figure 4). Additional examples are available in Supplemental Figure S2.

Table 4.

The PAC clusters and the associated structural information (present), Tox21 in vitro activities (active), and in silico toxicities (positive).

| Cluster ID | Representative PAC (Name) | ToxPrint structure | Tox21 in vitro activity | In silico toxicity prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Benzo(a)pyrene | fused_[6_6]_naphthalene|fused_PAH_anthracene|fused_PAH_benz(a)anthracene|fused_PAH_benzophenanthrene|fused_PAH_phenanthrene|fused_PAH_pyrene | NA | Human Adverse Cardiological Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Carcinogencity|Rodent Reproductive Adverse Effect|Rodent Sperm Abnormality |

| 2 | 2,4,6-Trimethylpyridinium p-toluenesulfonate | S=O_sulfonyl_generic | NA | Mammalian Cell Transformation|Rodent Gene Mutation |

| 3 | Zaltoprofen | C(=O)O_carboxylicAcid_alkyl|C(=O)O_carboxylicAcid_generic|C=O_carbonyl_generic|CC(=O)C_ketone_alkane_cyclic|COC_ether_aliphatic__aromatic|alkaneLinear_ethyl_C2_(connect_noZ_CN=4)|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_acyclic_connect_noDblBd|hetero_[7]_generic_1-Z | peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma(up) | Human Adverse Urinary Effects|Human Adverse Cardiological Effects |

| 4 | Isobutyl 2-naphthyl ether | COC_ether_aliphatic__aromatic|alkaneLinear_ethyl_C2_(connect_noZ_CN=4) | NA | Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Human Adverse Urinary Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Rodent Micronucleus |

| 5 | Imipramine | CN_amine_aliphatic_generic|CN_amine_aromatic_generic|CN_amine_ter-N_aliphatic|alkaneLinear_propyl_C3|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic|ligand_path_5_bidentate_propandiamine|hetero_[7]_generic_1-Z | mitochondrial membrane potential(up)|retinoic acid receptor(down) | Human Adverse Cardiological Effects|Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Human Adverse Urinary Effects|Rodent Newborn Behavior |

| 6 | Chrysene | fused_[6_6]_naphthalene|fused_PAH_anthracene|fused_PAH_phenanthrene | ATF6(up) | Human Adverse Cardiological Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 7 | Chlorpromazine | CN_amine_aliphatic_generic|CN_amine_aromatic_generic|CN_amine_ter-N_aliphatic|CS_sulfide|CX_halide_aromatic-X_generic|X[any]_halide|alkaneLinear_propyl_C3|ligand_path_5_bidentate_propandiamine|hetero_[6]_Z_1_4-|hetero_[6_6]_Z_generic|hetero_[6_6_6]_N_S_phenothiazine|hetero_[7]_generic_1-Z | AP-1(up)|mitochondrial membrane potential(up)|RAR-related orphan receptor gamma(down)|retinoic acid receptor(down) | Human Adverse Cardiological Effects|Human Adverse Urinary Effects|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Rodent Newborn Behavior|Rodent Reproductive Adverse Effect |

| 8 | 5,7-Dihydroxy-4-methylcoumarin | C(=O)O_carboxylicEster_alkenyl|C=O_carbonyl_generic|COH_alcohol_aromatic|COH_alcohol_generic|alkeneCyclic_ethene_C_(connect_noZ)|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic|hetero_[6]_Z_1-|hetero_[6]_Z_generic | NA | Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Micronucleus|Rodent Sperm Abnormality |

| 9 | Umbelliferone | C(=O)O_carboxylicEster_alkenyl|C=O_carbonyl_generic|alkeneCyclic_ethene_C_(connect_noZ)|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic|hetero_[6]_Z_1-|hetero_[6]_Z_generic | NA | Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Micronucleus |

| 10 | Proflavin hemisulfate | CN_amine_aromatic_generic|CN_amine_pri-NH2_aromatic|alkeneCyclic_diene_cyclopentadiene|aromatic_biphenyl|fused_PAH_fluorene|hetero_[6]_N_pyridine|hetero_[6_6]_N_quinoline | androgen receptor(down)|aromatase(down)|aryl hydrocarbon receptor(up)|constitutive androstane receptor(down)|estrogen receptor alpha(up)|farnesoid X receptor(down)|Ku70/Rad54(up)|retinoic acid receptor(down)|retinoic acid receptor(up)|thyroid receptor(down) | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Micronucleus |

| 11 | Anthraquinone | C=O_carbonyl_generic|CC(=O)C_ketone_alkane_cyclic|CC(=O)C_quinone_1_4-benzo|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic | NA | Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Gene Mutation|Rodent Micronucleus|Rodent Reproductive Adverse Effect|Rodent Sperm Abnormality |

| 12 | Purpurin | C=O_carbonyl_generic|CC(=O)C_ketone_alkane_cyclic|CC(=O)C_quinone_1_4-benzo|COH_alcohol_generic|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic | aryl hydrocarbon receptor(up)|estrogen receptor alpha(up)|mitochondrial membrane potential(down) | Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Gene Mutation|Rodent Micronucleus|Rodent Sperm Abnormality |

| 13 | Methylene blue | CN_amine_aliphatic_generic|CN_amine_aromatic_generic|CN_amine_sec-NH_alkyl|CN_amine_ter-N_aliphatic|CN_amine_ter-N_aromatic_aliphatic | androgen receptor(up)|aryl hydrocarbon receptor(up)|Nrf2(up)|p53(up)|retinoic acid receptor(up) | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Micronucleus |

| 14 | 9-Ethylcarbazole | hetero_[5]_N_pyrrole_generic|hetero_[5]_O_furan|hetero_[5]_Z_1-Z|hetero_[6_5_6]_N_carbazole | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 15 | 1-Amino-2,4-dibromoanthraquinone | C=O_carbonyl_generic|CC(=O)C_ketone_alkane_cyclic|CC(=O)C_quinone_1_4-benzo|CX_halide_aromatic-X_generic|X[any]_halide|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic | NA | Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Carcinogencity |

| 16 | 1,5-Naphthalenedisulfonic acid, disodium salt hydrate | element_metal_group_I_II|COH_alcohol_aromatic|COH_alcohol_generic|S(=O)O_sulfonate|S=O_sulfonyl_generic|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene | NA | Mammalian Cell Transformation |

| 17 | 6-Amino-4-hydroxynaphthalene-2-sulfonic acid | CN_amine_aromatic_generic|CN_amine_pri-NH2_aromatic|S(=O)O_sulfonate|S=O_sulfonyl_generic|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 18 | Trioxsalen | C(=O)O_carboxylicEster_alkenyl|C=O_carbonyl_generic|COC_ether_aliphatic__aromatic|alkeneCyclic_ethene_C_(connect_noZ)|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic|hetero_[5]_O_furan|hetero_[5]_Z_1-Z|hetero_[6]_Z_1-|hetero_[6]_Z_generic | androgen receptor(down) | Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 19 | 2,6-Dimethylnaphthalene | aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_acyclic_connect_noDblBd|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Rodent Reproductive Adverse Effect |

| 20 | 3-Methylcholanthrene | aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_acyclic_connect_noDblBd|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene|fused_PAH_anthracene|fused_PAH_benz(a)anthracene|fused_PAH_phenanthrene | aryl hydrocarbon receptor(up) | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Carcinogencity|Rodent Reproductive Adverse Effect |

| 21 | 1-Methylpyrene | aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_acyclic_connect_noDblBd|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene|fused_PAH_phenanthrene | androgen receptor(down)|constitutive androstane receptor(up)|retinoic acid receptor(up) | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Carcinogencity|Rodent Reproductive Adverse Effect|Rodent Sperm Abnormality |

| 22 | Cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride | CN_amine_aliphatic_generic|CN_amine_sec-NH_alkyl|X[any]_halide|alkaneLinear_propyl_C3|alkeneCyclic_ethene_C_(connect_noZ)|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic | mitochondrial membrane potential(up) | Human Adverse Cardiological Effects|Human Adverse Urinary Effects |

| 23 | 6-Hydroxy-2-naphthoic acid | C(=O)O_carboxylicAcid_aromatic|C(=O)O_carboxylicAcid_generic | NA | Mammalian Cell Transformation |

| 24 | 2,3-Dichloroquinoxaline | hetero_[6]_N_pyrazine|hetero_[6]_Z_1_4-|hetero_[6]_Z_generic|hetero_[6_6]_Z_generic | NA | Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation |

| 25 | 9-Anthracenemethanol | COH_alcohol_generic|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene|fused_PAH_anthracene | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Newborn Behavior |

| 26 | Bretylium tosylate | S=O_sulfonyl_generic | NA | Human Adverse Cardiological Effects |

| 27 | 6-Nitroquinoline | N(=O)_nitro_aromatic|hetero_[6_6]_N_quinoline | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Micronucleus|Rodent Sperm Abnormality |

| 28 | Benzo(k)fluoranthene | alkeneCyclic_diene_cyclopentadiene|aromatic_biphenyl|fused_PAH_acenaphthylene | aryl hydrocarbon receptor(up) | Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 29 | Dibenzothiophene | hetero_[5]_Z_1-Z | NA | Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 30 | Dizocilpine maleate | CS_sulfide|hetero_[5]_N_pyrrole_generic|hetero_[5]_Z_1-Z | NA | NA |

| 31 | 2-Hydroxyanthraquinone | C=O_carbonyl_generic|CC(=O)C_ketone_alkane_cyclic|CC(=O)C_quinone_1_4-benzo|COH_alcohol_aromatic|COH_alcohol_generic|aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_cyclic | Ku70/Rad54(up)|mitochondrial membrane potential(down)|Nrf2(up) | Human Adverse Hepatobiliary Effects|Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Carcinogencity|Rodent Sperm Abnormality|Rodent Reproductive Adverse Effect |

| 32 | 4,7-Dichloroquinoline | COH_alcohol_aromatic|COH_alcohol_generic|CX_halide_aromatic-X_generic|CX_halide_aromatic-X_halo_phenol_para|X[any]_halide|hetero_[6]_N_pyridine|hetero_[6]_Z_1-|hetero_[6]_Z_generic|hetero_[6_6]_N_quinoline|hetero_[6_6]_Z_generic | androgen receptor(down)|ATAD5(up)|estrogen receptor alpha(down)|gamma-H2AX(up)|glucocorticoid receptor(down)|HSF(up)|p53(up)|peroxisome proliferator activated receptor delta(down)|RAR-related orphan receptor gamma(down)|vitamin D receptor(down) | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Rodent Micronucleus |

| 33 | Pyrene | alkeneCyclic_diene_cyclopentadiene|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene|fused_PAH_acenaphthylene|fused_PAH_phenanthrene|fused_PAH_pyrene | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Carcinogencity |

| 34 | 1,5-Dinitronaphthalene | N(=O)_nitro_aromatic|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene | androgen receptor(down)|glucocorticoid receptor(down)|mitochondrial membrane potential(down) | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation|Rodent Carcinogencity|Rodent Sperm Abnormality|Rodent Micronucleus |

| 35 | 2-Naphthalenol | NA | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Rodent Newborn Behavior|Rodent Sperm Abnormality |

| 36 | Acenaphthene | CN_amine_aromatic_generic|fused_[6_6]_naphthalene | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 37 | Quinoline | hetero_[6]_N_pyridine|hetero_[6]_Z_1-|hetero_[6]_Z_generic|hetero_[6_6]_N_quinoline|hetero_[6_6]_Z_generic | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 38 | 8-Hydroxyquinoline citrate | COH_alcohol_aromatic|COH_alcohol_generic|hetero_[6]_N_pyridine|hetero_[6]_Z_1-|hetero_[6]_Z_generic|hetero_[6_6]_N_quinoline|hetero_[6_6]_Z_generic | gamma-H2AX(up)|glucocorticoid receptor(up)|HSF(up)|p53(up)|retinoic acid receptor(down) | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation |

| 39 | 6-Methylquinoline | aromaticAlkane_Ph-C1_acyclic_connect_noDblBd|hetero_[6]_N_pyridine|hetero_[6]_Z_1-|hetero_[6]_Z_generic|hetero_[6_6]_N_quinoline|hetero_[6_6]_Z_generic | NA | Mammalian Cell Chromsome Aberrations|Mammalian Cell Gene Mutation|Mammalian Cell Sister Chromatid Exchange (SCE)|Mammalian Cell Transformation|Microbe Gene Mutation |

Figure 4.

Properties of three categories (in silico toxicity, in vitro activity, and structural fingerprints) associated with PAC clusters. Clusters on the UMAP space associated with one example of each of the three categories are highlighted: a) Microbe Gene Mutation from in silico toxicity category, b) aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation from in vitro activity category, and c) ring:hetero_[6_6]_N_quinoline from structural fingerprint category. The solid colored points represent the positive cases in each property category. Clusters that are associated with the property have their cluster ID numbers shown in colored text. Summaries of the properties associated with each PAC cluster are presented in d) in silico toxicity, e) in vitro activity, and f) structural fingerprints.

For in silico toxicities, 180 out of the 260 (toxicity x cluster) combinations showed associations. The 180 (toxicity x cluster) combinations covered 14 toxicity types and 38 clusters. Only Cluster Id = 30 did not have any associated toxicity (Figure 4d). The annotation of ‘Mammalian Cell Transformation’ (in vitro) had the greatest number of associated clusters, followed by ‘Mammalian Cell Chromosome Aberrations’ (in vitro), and ‘Microbe Gene Mutation’ (in vitro). The clusters associated with the ‘Mammalian Cell Transformation’ (in vitro) were highlighted in Figure 4a. The analyses showed that PACs are highly enriched with genotoxicity related in silico toxicities.

For in vitro activities, 54 out of the 305 (Tox21 activity x cluster) combinations showed associations. The 54 combinations covered 28 different types of Tox21 activities and 16 (out of 39) clusters. More clusters did not have any associated activities (Figure 4e) than ones with associated activities. The increase of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) transcriptional factor (TF) activity and decrease of androgen receptor (AR) TF activity were the two activities with the greatest number of associated clusters. The clusters associated with AhR activity are highlighted in Figure 4b. The analyses showed that AhR activation is the top enriched in vitro activity in PACs.

For ToxPrint structural fingerprints, 303 out of the 748 (fingerprint x cluster) combinations showed associations. The number was further reduced to 182 (fingerprint x cluster) combinations by removing the redundant cases (i.e., the entries with the same number of incidences in the dataset). The 182 (fingerprint x cluster) combinations covered 53 fingerprints and 38 clusters; only Cluster Id = 35 did not have any associated fingerprint (Figure 4f). The clusters associated with the quinoline structures were highlighted in Figure 4c. By inspecting the associated structural fingerprints, we found that the Cluster Ids = 11, 12, 15, 31 were associated with oxygenated PAHs; Cluster Ids = 27, 34 were associated with the nitro-PAHs; Cluster Ids = 19, 20, 21, 39 were associated with the alkylated-PAHs. The PACs with quinoline structures (Cluster Ids = 10, 27, 32, 37, 38, 39) were located closely. The analyses demonstrated that PACs with similar substituted groups (e.g., alkylated-PAHs) or heterocyclics with varying ring sizes (e.g., N-PACs) could have similar in silico toxicity profiles. Compared with PACs with PAH structures (Figure 3), particularly the PACs with a fluorene structure, which could have diverse in silico toxicity profiles. Therefore, substituent groups appear to be better candidates for toxicity read-across analysis.

Context driven PAC prioritization

The PCA results of PACs using either in silico toxicity profiles (Figure 5a) or in vitro activity profiles (Figure 5d) as the input variables are shown. The variables in the in silico toxicity profile that are positively correlated with PC#1, the dimension that preserves the most variance in the dataset, are in the category of genotoxicity/carcinogenicity (Figure 5a). The PACs with higher scores in PC#1 are mostly in the lower-right corner (Cluster Id = 10, 11, 12, 31, 34) of the map, including amino-PAHs, oxygenated-PAHs (anthraquinones), and nitro-PAHs. (Figure 5b). The top 2 variables that are positively correlated with PC#2 are the ‘human adverse hepatobiliary effects’ and ‘rodent reproductive adverse effects’. The PACs with higher scores in PC#2 are in scattered corners of the map (Cluster Id = 1, 7, 11, 12), including PAHs, chemicals with dimethylaminoalkyl functional groups (e.g., promazine), and oxygenated-PAHs (anthraquinones). Similar plots were generated for the PCA results using in vitro activity profiles. For PC#1, the top variables that are positively correlated include processes related to xenobiotic homeostasis (AhR, constitutive androstane receptor [CAR], genotoxic stress [p53], and oxidative stress [Nrf2]). The PACs with higher scores in PC#1 are around the middle area of the map (Cluster Id = 10, 32, 13, 38), including amino-PAHs, halogenated-PAHs, phenothiazines, quinolines. For PC#2, the two positively correlated variables are a decrease of TF activity of RAR related orphan receptor gamma (RORg) and retinoic acid receptor (RAR). The clusters with higher scores are less distinctive, including Cluster Id = 7 and 10 (promazine class of compounds and amino-PAHs). The analyses demonstrate that there are regions of PACs that are enriched with certain toxicities/activities in the PAC toxicity landscape (i.e., “hot spots”). These regions are candidates for further resource-intensive testing; for example, prioritization could be given to testing individual PACs in these hot spots that have not been tested yet. Below, the availability (tested/non-tested) of the related in vivo data was overlaid onto the map to identify data-poor/data-rich regions.

Figure 5.

Context-driven chemical prioritization. a)-c) PCA results of PACs based on in silico toxicity profile. a) The correlation (color) and quality (size) of the representation of in silico toxicity in the PC space. Only quality > 0.2 are shown. b) The score of PC #1 of PACs overlaid on the UMAP space based on in silico toxicity profiles. c) The score of PC #2 of PACs overlaid on the UMAP space. d)-f) PCA results of PACs based on Tox21 in vitro activity profile. The description of d)-f) is the same as a)-c). A higher score at PC axis represents higher values in the positively correlated variables in the original space. The availability of carcinogenicity (g) or reproductive/developmental (h) studies of PACs overlaid on the UMAP space based on in silico toxicity profiles.

The availability of carcinogenicity studies or reproductive/developmental studies of PACs were used to color the PACs in Figures 5g and 5h. The PACs with carcinogenicity studies are located mostly in the lower half of the map, where PACs also had a higher probability of being associated with genotoxicity/carcinogenicity related endpoints. This is not surprising since the map was built using in silico predictions trained on the related datasets. However, there are some clusters that have high predicted probability in genotoxicity/carcinogenicity related endpoints but do not have many chemicals with carcinogenicity studies such as Cluster Id = 8, 25 (hydroxy-PAHs), 21 (alkylated PAHs), 31 (oxygenated-PAHs). These are potential candidates for prioritization. Also, in some clusters (Cluster Id = 10, 11, 12), many of the PACs could already have carcinogenicity studies. These PACs can be used for read-across to the unknown PACs in the same cluster. For reproductive/developmental study types, there are fewer PACs with data. Most PACs with data are in the upper corner (Cluster Id = 5, 7). The data on in vivo (study counts), in vitro activity, and in silico toxicity predictions can be found in Supplemental File S4.

We highlighted the results for PACs currently being evaluated for immunotoxicity in vivo (Figure 6a). The only two PACs from the in vivo testing set that were not included in clusters were benz(j)aceanthrylene and acenaphthenequinone. The 11 remaining PACs were included in six different clusters (Table 2). The underlying in silico toxicity profiles were presented as a heatmap in Figure 6b. Comparing with Figure 5b, the dispersion of the 13 PACs ranges from higher probability in carcinogenicity (e.g., chrysene), to medium probability (e.g., acenaphthenequinone), to lower probability (e.g., benzo(b)fluoranthene), based on the in silico predictions. The 13 PACs are in the “hot spots” related to genotoxicity/carcinogenicity with varying degrees (high → low: benzo(a)pyrene → dibenzothiophene). One cluster (#28, including benzo(b)fluoranthene) is particularly associated with AhR activation. While AhR is involved in both carcinogenicity and immunotoxicity of PACs, the precise mechanisms have not been fully elucidated4,26. The in vivo immunotoxicity results can be used to compare with the data in the map (e.g., will we see more similar in vivo results for the PACs in the same cluster versus those in different clusters? how will the differences between clusters relate to the differences observed in immunotoxicity?), and the map may be useful for next-round PAC prioritization.

Figure 6.

The 13 PACs under immunotoxicity testing. a) The PACs are text-labeled and colored based on clustering results from HDBSCAN on the UMAP space using in silico toxicity profiles. Benz(j)aceanthrylene and acenaphthenequinone cannot be clustered with others and are labeled with black text. b) The in silico toxicity profile of the PACs presented as a heatmap. The rows of the heatmap are the PACs and the columns are the in silico toxicity. The annotations of the PACs (cluster ID) and the toxicity (type and environment) are attached with the heatmap. The rows and columns of the heatmap were arranged based on average linkage hierarchical clustering with Euclidean distance. The similarity relationship between PACs are similar between the map and hierarchical clustering

Interactive visualization of results online

To allow users to easily search results and to generate hypotheses, a Tableau application was constructed (https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/go/pacs_tableau). One screenshot is presented in Figure 7. In the application, the UMAP representation is used as the background and the results of association tests can be searched for selected clusters. Most importantly, on-the-fly structural images of PACs can be seen in the application when the pointer hovers on a data point. Additionally, a link to connect to the EPA Chemical Dashboard entry for the selected PAC is available.

Figure 7.

A screenshot of the online application. The orange frames show PAC clustering results using in silico toxicity profiles. The green/brown frames show in silico toxicity/in vitro activity associated with the selected PAC cluster. The purple frame shows the respective PAC structural image.

Discussion

While there is a significant body of literature on the toxicity of individual PACs, particularly PAHs, the big picture of how to evaluate risk from exposure to these ubiquitous contaminants remains obscure. The dual challenges are the incredible structural diversity and the wide array of biological activities displayed within the class. Although there has been some progress in the decades since scientists first attempted to link structural features of PAHs to carcinogenic potential27, the scope of QSAR work has focused on parent PAHs and carcinogenicity. When considering the broader PAC class and the suite of potential toxicity targets, progress is more difficult to achieve. Fundamentally, the structural boundaries of the PAC class are not clear. Once defined, it is important to consider whether all PACs should be included as a target chemical class for risk evaluation. Alternatively, should focused research and regulatory attention be directed at more well-defined, cohesive classes within the PAC ‘universe’? If so, which of these groups should be prioritized to maximize the public health impact from investment? The study presented here is part of the hazard characterization aim of the NTP PAC research program and is directed at these questions.

The first goal of this hazard characterization work was to harness existing data on PACs to better understand the PAC toxicity landscape. In effect, which PAC members have toxicity data, and can patterns of activity provide information for prioritization or read-across activities? To facilitate exploration of available PAC data, an automated approach for identifying PAC structures in chemical libraries was required. To this end, we developed reusable KNIME workflows based on SMARTS queries that can be used to identify PACs and label the PACs as parent, substituted, or heterocyclic, from a supplied chemical library. In this study, the Tox21 library was used, but the approach can be easily applied to other compound libraries. The Tox21 library was selected because it has been screened for over 40 different endpoints related to nuclear receptor and stress response pathways28. Notably, the Tox21 library comprises purchasable compounds soluble in DMSO29. When constructing the SMARTS queries for PAC definitions, we intentionally did not set a limitation on the length of substituted groups to filter the identified PACs. Instead, the PACs were filtered based on their similarity to the selected reference PACs using physicochemical descriptors. This approach is intended to include PACs with more diverse substituted groups in this study for the purpose of PAC clustering. Clustering similar PACs together can help to prioritize compounds for testing either by diverse sampling (i.e., selecting a representative PAC from each cluster) or by targeted sampling (i.e., selecting multiple PACs from a single cluster).

The selection of a profile to characterize compounds is critical in clustering; common options include structural fingerprints (e.g., extended connectivity fingerprint, ECFP30) and biological descriptors (e.g., Tox21/ToxCast assay readouts31). For complex endpoints such as toxicity, the inclusion of biological descriptors may improve the accuracy of toxicity predictions and help to provide mechanistic insights32. In this study, besides the two types of descriptors mentioned above, we used the in silico toxicity profile generated from QSAR models as descriptors. By using in silico QSAR-based profiles as descriptors, we can combine both structural and biological information more uniformly than using the ‘hybrid descriptors’33, which are generated by concatenation of two types of descriptors. Additionally, since the number of PACs could be large, by using the in silico toxicity profile, we enabled evaluation of PACs without experimental data (e.g., three of the PACs under in vivo immunotoxicity testing do not have Tox21 data). While these in silico QSAR models cover more biological space than only carcinogenicity-related endpoints (i.e., carcinogenicity, cardiotoxicity, developmental toxicity, genotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, neurotoxicity, reproductive toxicity, and urinary toxicity), they do not include immunotoxicity, our endpoint of interest for 13 PACs currently being tested at NTP. In addition, immune-related endpoints are also absent from the Tox21 assay coverage. A number of in vitro methods are available to screen human and rodent cells to assess the ability of xenobiotics to modulate the immune system, including cytokine release assays34 and the Multi-ImmunoTox Assay35, but to date, these methods have been focused on evaluating therapeutics rather than environmental chemicals, and are not designed to support risk quantification36. A focus on improving the immunotoxicity database for PACs is important, considering the association of some parent PAHs with decreased immune function37, the link between immune suppression and cancer19, and a lack of immune-related data on many PACs.

The algorithm we selected for clustering is HDBSCAN. HDBSCAN contains both features of hierarchical-based clustering and density-based, non-parametric clustering (the density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise, or DBSCAN, the predecessor of HDBSCAN). HDBSCAN has several advantages compared to the more traditional methods such as k-Means or related centroid-based parametric methods, including varying density of points in clusters and a more intuitive parameter selection process. The most useful feature related to read-across application is to allow data points (PACs in our case) that are dissimilar to others not to be grouped with others (i.e., singletons). In read-across, compounds in a cluster vs compounds as singletons can be treated differently. In addition, it is possible to predict the activity/toxicity of new PACs based on the read-across concept (i.e., compounds in the same cluster can have similar properties) using clusters from HDBSCAN. HDBSCAN has the functionality to predict clusters for the new data points (PACs). Future application of HDBSCAN to read-across could include more quantitative approaches38 to evaluate the predictivity of the tool.

Rendering high-dimensional data in 2D space is useful to communicate results and to generate hypotheses. In the past, we have tried t-SNE using Tox21 in vitro assay readouts as descriptors31. Here we adopted a newly developed approach, UMAP. UMAP belongs to the same class of algorithm as t-SNE (neighbor graph) but claims to preserve more global similarity and as much local similarity as shown in the single-cell analysis39. In our example (Figure 6 and unpublished data), we also think UMAP does better in that respect, as the location of clusters on the UMAP representation provides relative similarity between clusters. This observation is important since a user tends to consider neighboring points as having similar profiles.

After clustering, we propose two ways of linking in silico and in vitro data with the identified clusters. The prioritization plan can be discussed in conjunction with the in vivo data. The first approach is by performing association tests for each (data set x cluster) combination. This approach provides detailed associated properties attached to each cluster and allows for identification of underlying activities for each of the compounds. The second approach utilizes PCA results and UMAP visualization to give an overview of summarized activities on the chemical landscape. This approach allows the user to quickly identify the areas that are hot spots for the summarized activities. The two approaches are complementary to each other for prioritizing compounds. In interpreting PAC activity outcomes from Tox21 in vitro assays, one should be cautious and address potential interference because parent PAHs are known to be auto-fluorescent due to their resonance structures40 and fluorescence is one of the major readout methods used in Tox21 in vitro assays. In our analysis, we filtered out potential assay interference, including compound auto-fluorescence, quenching, cytotoxicity, etc.21. Also, Tox21 assays have limited metabolic capacity28. For the PACs that require metabolic activation, expected outcomes may not be observed.

In summary, we have developed a data-driven approach to contextualize hazard characterization of PACs by leveraging the available data from various data streams (in silico toxicity, in vitro activity, structural fingerprints, and in vivo data availability). This strategy can be used to prioritize PACs for further testing and aid in chemical read-across efforts. Furthermore, these approaches can be extended to other classes of compounds which need hazard characterization.

Supplementary Material

File S2: an Excel file with Tox21 chemicals (and their structural images) satisfying the minimal requirement PAC characteristics

File S1: KNIME workflows for identifying PACs in a library

File S3: an Excel file including sheets including results from clustering, association analyses, and the positive cases in the association analyses

File S4: an Excel file with PACs and their activity profiles (in silico, in vitro, in vivo) appended

Table 3.

The 13 PACs under NTP in vivo immunotoxicity testing and the cluster to which they belong.

| Cluster ID | Chemical Name | Chemical structure | DSSTOXID | Reference PAC? | PAC type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (singleton) | Benz(j)aceanthrylene |

|

DTXSID30174041 | No | parent |

| 0 (singleton) | Acenaphthenequinone |

|

DTXSID7049429 | No | substituted |

| 1 | Benzo(a)pyrene |

|

DTXSID2020139 | Yes | parent |

| 1 | Dibenz(a,h)anthracene |

|

DTXSID9020409 | Yes | parent |

| 1 | Dibenzo[a,l]pyrene |

|

DTXSID9059753 | No | parent |

| 6 | Chrysene |

|

DTXSID0022432 | Yes | parent |

| 6 | Phenanthrene |

|

DTXSID6024254 | Yes | parent |

| 14 | 7H-Benzo[c]fluorene |

|

DTXSID30874039 | No | parent |

| 28 | Benzo(b)fluoranthene |

|

DTXSID0023907 | No | parent |

| 28 | Benzo(k)fluoranthene |

|

DTXSID0023909 | No | parent |

| 29 | Dibenzothiophene |

|

DTXSID0047741 | Yes | heterocyclic |

| 33 | Pyrene |

|

DTXSID3024289 | Yes | parent |

| 33 | Indeno(1,2,3-cd)pyrene |

|

DTXSID8024153 | No | parent |

Acknowledgments

We thank Leadscope, Inc. for providing the QSAR models and SAR databases. And we thank Dr. Amy Wang and Dr. Steve Ferguson for providing valuable comments when reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, Intramural Research project ZIA ES103316.

References

- (1).Rhomberg LR; Mayfield DB; Prueitt RL; Rice JW A Bounding Quantitative Cancer Risk Assessment for Occupational Exposures to Asphalt Emissions during Road Paving Operations. Crit. Rev. Toxicol 2018, 48 (9), 713–737. 10.1080/10408444.2018.1528208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Singh L; Varshney JG; Agarwal T. Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons’ Formation and Occurrence in Processed Food. Food Chem. 2016, 199, 768–781. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Agudelo-Castañeda DM; Teixeira EC; Schneider IL; Lara SR; Silva LFO Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons in Atmospheric PM1.0 of Urban Environments: Carcinogenic and Mutagenic Respiratory Health Risk by Age Groups. Environ. Pollut 2017, 224, 158–170. 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.01.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. Some Non-Heterocyclic Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Some Related Exposures. IARC Monogr. Eval. Carcinog. Risks Hum 2010, 92, 1–853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).U.S. EPA. Provisional Guidance for Quantitative Risk Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAH). U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Office of Research and Development, Office of Health and Environmental Assessment, Washington, DC: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- (6).Inyang F; Ramesh A; Kopsombut P; Niaz MS; Hood DB; Nyanda AM; Archibong AE Disruption of Testicular Steroidogenesis and Epididymal Function by Inhaled Benzo(a)Pyrene. Reprod. Toxicol 2003, 17 (5), 527–537. 10.1016/S0890-6238(03)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Jurisicova A; Taniuchi A; Li H; Shang Y; Antenos M; Detmar J; Xu J; Matikainen T; Benito Hernández A; Nunez G; Casper RF Maternal Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons Diminishes Murine Ovarian Reserve via Induction of Harakiri. J. Clin. Invest 2007, 117 (12), 3971–3978. 10.1172/JCI28493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Choi H; Jedrychowski Wieslaw; Spengler John; Camann David E.; Whyatt Robin M.; Rauh Virginia; Tsai Wei-Yann; Perera Frederica P. International Studies of Prenatal Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Fetal Growth. Environ. Health Perspect 2006, 114 (11), 1744–1750. 10.1289/ehp.8982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Chen C; Tang Y; Jiang X; Qi Y; Cheng S; Qiu C; Peng B; Tu B. Early Postnatal Benzo(a)Pyrene Exposure in Sprague-Dawley Rats Causes Persistent Neurobehavioral Impairments That Emerge Postnatally and Continue into Adolescence and Adulthood. Toxicol. Sci 2012, 125 (1), 248–261. 10.1093/toxsci/kfr265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Blanton RH; Lyte M; Myers MJ; Bick PH Immunomodulation by Polyaromatic Hydrocarbons in Mice and Murine Cells. Cancer Res. 1986, 46 (6), 2735–2739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Keith LH The Source of U.S. EPA’s Sixteen PAH Priority Pollutants. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd 2015, 35 (2–4), 147–160. 10.1080/10406638.2014.892886. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Flowers L; Rieth SH; Cogliano VJ; Foureman GL; Hertzberg R; Hofmann EL; Murphy DL; Nesnow S; Schoeny RS Health Assessment of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Mixtures: Current Practices and Future Directions . Polycycl. Aromat. Compd 2002, 22 (3–4), 811–821. 10.1080/10406630290103960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Zaccaria KJ; McClure PR Using Immunotoxicity Information to Improve Cancer Risk Assessment for Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Mixtures: Int. J. Toxicol 2013. 10.1177/1091581813492829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Attene-Ramos MS; Miller N; Huang R; Michael S; Itkin M; Kavlock RJ; Austin CP; Shinn P; Simeonov A; Tice RR; Xia M. The Tox21 Robotic Platform for the Assessment of Environmental Chemicals – from Vision to Reality. Drug Discov. Today 2013, 18 (15), 716–723. 10.1016/j.drudis.2013.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Matthews EJ; Kruhlak NL; Weaver JL; Contrera RDB and J F Assessment of the Health Effects of Chemicals in Humans: II. Construction of an Adverse Effects Database for QSAR Modeling http://www.eurekaselect.com/91448/article (accessed May 15, 2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Škuta C; Cortés-Ciriano I; Dehaen W; Kříž P; van Westen GJP; Tetko IV; Bender A; Svozil D. QSAR-Derived Affinity Fingerprints (Part 1): Fingerprint Construction and Modeling Performance for Similarity Searching, Bioactivity Classification and Scaffold Hopping. J. Cheminformatics 2020, 12 (1), 39. 10.1186/s13321-020-00443-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Riniker S; Wang Y; Jenkins JL; Landrum GA Using Information from Historical High-Throughput Screens to Predict Active Compounds. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2014, 54 (7), 1880–1891. 10.1021/ci500190p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Sturm N; Sun J; Vandriessche Y; Mayr A; Klambauer G; Carlsson L; Engkvist O; Chen H. Application of Bioactivity Profile-Based Fingerprints for Building Machine Learning Models. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2019, 59 (3), 962–972. 10.1021/acs.jcim.8b00550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Hanahan D; Weinberg RA Hallmarks of Cancer: The next Generation. Cell 2011, 144 (5), 646–674. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).McInnes L; Healy J; Astels S. hdbscan: Hierarchical density based clustering https://joss.theoj.org (accessed Oct 4, 2019). 10.21105/joss.00205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Hsieh J-H; Sedykh A; Huang R; Xia M; Tice RR A Data Analysis Pipeline Accounting for Artifacts in Tox21 Quantitative High-Throughput Screening Assays. J. Biomol. Screen 2015, 20 (7), 887–897. 10.1177/1087057115581317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yang C; Tarkhov A; Marusczyk J; Bienfait B; Gasteiger J; Kleinoeder T; Magdziarz T; Sacher O; Schwab CH; Schwoebel J; Terfloth L; Arvidson K; Richard A; Worth A; Rathman J. New Publicly Available Chemical Query Language, CSRML, To Support Chemotype Representations for Application to Data Mining and Modeling. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2015, 55 (3), 510–528. 10.1021/ci500667v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Lê S; Josse J; Husson F. FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis. J. Stat. Softw 2008, 25 (1), 1–18. 10.18637/jss.v025.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Heikamp K; Bajorath J. Large-Scale Similarity Search Profiling of ChEMBL Compound Data Sets. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2011, 51 (8), 1831–1839. 10.1021/ci200199u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).McInnes L; Healy J; Saul N; Großberger L. UMAP: Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection https://joss.theoj.org (accessed Oct 4, 2019). 10.21105/joss.00861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Stevens EA; Mezrich JD; Bradfield CA The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor: A Perspective on Potential Roles in the Immune System. Immunology 2009, 127 (3), 299–311. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Vijayalakshmi KP; Suresh CH Theoretical Studies on the Carcinogenicity of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. J. Comput. Chem 2008, 29 (11), 1808–1817. 10.1002/jcc.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Tice RR; Austin CP; Kavlock RJ; Bucher JR Improving the Human Hazard Characterization of Chemicals: A Tox21 Update. Environ. Health Perspect 2013, 121 (7), 756–765. 10.1289/ehp.1205784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Richard AM; Judson RS; Houck KA; Grulke CM; Volarath P; Thillainadarajah I; Yang C; Rathman J; Martin MT; Wambaugh JF; Knudsen TB; Kancherla J; Mansouri K; Patlewicz G; Williams AJ; Little SB; Crofton KM; Thomas RS ToxCast Chemical Landscape: Paving the Road to 21st Century Toxicology. Chem. Res. Toxicol 2016, 29 (8), 1225–1251. 10.1021/acs.chemrestox.6b00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Rogers D; Hahn M. Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints. J. Chem. Inf. Model 2010, 50 (5), 742–754. 10.1021/ci100050t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hubbard TD; Hsieh J-H; Rider CV; Sipes NS; Sedykh A; Collins BJ; Auerbach SS; Xia M; Huang R; Walker NJ; DeVito MJ Using Tox21 High-Throughput Screening Assays for the Evaluation of Botanical and Dietary Supplements. Appl. Vitro Toxicol 2019, 5 (1), 10–25. 10.1089/aivt.2018.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Russo Daniel P; Strickland Judy; Karmaus Agnes L.; Wang Wenyi; Shende Sunil; Hartung Thomas; Aleksunes Lauren M.; Zhu Hao. Nonanimal Models for Acute Toxicity Evaluations: Applying Data-Driven Profiling and Read-Across. Environ. Health Perspect 127 (4), 047001. 10.1289/EHP3614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Sedykh A; Zhu H; Tang H; Zhang L; Richard A; Rusyn I; Tropsha A. Use of in Vitro HTS-Derived Concentration-Response Data as Biological Descriptors Improves the Accuracy of QSAR Models of in Vivo Toxicity. Environ. Health Perspect 2011, 119 (3), 364–370. 10.1289/ehp.1002476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Finco D; Grimaldi C; Fort M; Walker M; Kiessling A; Wolf B; Salcedo T; Faggioni R; Schneider A; Ibraghimov A; Scesney S; Serna D; Prell R; Stebbings R; Narayanan PK Cytokine Release Assays: Current Practices and Future Directions. Cytokine 2014, 66 (2), 143–155. 10.1016/j.cyto.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Kimura Y; Fujimura C; Ito Y; Takahashi T; Aiba S. Evaluation of the Multi-ImmunoTox Assay Composed of 3 Human Cytokine Reporter Cells by Examining Immunological Effects of Drugs. Toxicol. Vitro Int. J. Publ. Assoc. BIBRA 2014, 28 (5), 759–768. 10.1016/j.tiv.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Vidal J-M; Kawabata TT; Thorpe R; Silva-Lima B; Cederbrant K; Poole S; Mueller-Berghaus J; Pallardy M; Van der Laan J-W In Vitro Cytokine Release Assays for Predicting Cytokine Release Syndrome: The Current State-of-the-Science. Report of a European Medicines Agency Workshop. Cytokine 2010, 51 (2), 213–215. 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).White KL; Lysy HH; Holsapple MP Immunosuppression by Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons: A Structure-Activity Relationship in B6C3F1 and DBA/2 Mice. Immunopharmacology 1985, 9 (3), 155–164. 10.1016/0162-3109(85)90011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Shah I; Liu J; Judson RS; Thomas RS; Patlewicz G. Systematically Evaluating Read-across Prediction and Performance Using a Local Validity Approach Characterized by Chemical Structure and Bioactivity Information. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol 2016, 79, 12–24. 10.1016/j.yrtph.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Becht E; McInnes L; Healy J; Dutertre C-A; Kwok IWH; Ng LG; Ginhoux F; Newell EW Dimensionality Reduction for Visualizing Single-Cell Data Using UMAP. Nat. Biotechnol 2019, 37 (1), 38–44. 10.1038/nbt.4314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).William E. Acree Jr; Tucker SA; Fetzer JC Fluorescence Emission Properties of Polycyclic Aromatic Compounds in Review. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd 1991, 2 (2–3), 75–105. 10.1080/10406639108048933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

File S2: an Excel file with Tox21 chemicals (and their structural images) satisfying the minimal requirement PAC characteristics

File S1: KNIME workflows for identifying PACs in a library

File S3: an Excel file including sheets including results from clustering, association analyses, and the positive cases in the association analyses

File S4: an Excel file with PACs and their activity profiles (in silico, in vitro, in vivo) appended