Abstract

Fluorine (19F) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is severely limited by a low signal-to noise ratio (SNR), and tapping it for 19F drug detection in vivo still poses a significant challenge. However, it bears the potential for label-free theranostic imaging. Recently, we detected the fluorinated dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitor teriflunomide (TF) noninvasively in an animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS) using 19F MR spectroscopy (MRS). In the present study, we probed distinct modifications to the CF3 group of TF to improve its SNR. This revealed SF5 as a superior alternative to the CF3 group. The value of the SF5 bioisostere as a 19F MRI reporter group within a biological or pharmacological context is by far underexplored. Here, we compared the biological and pharmacological activities of different TF derivatives and their 19F MR properties (chemical shift and relaxation times). The 19F MR SNR efficiency of three MRI methods revealed that SF5-substituted TF has the highest 19F MR SNR efficiency in combination with an ultrashort echo-time (UTE) MRI method. Chemical modifications did not reduce pharmacological or biological activity as shown in the in vitro dihydroorotate dehydrogenase enzyme and T cell proliferation assays. Instead, SF5-substituted TF showed an improved capacity to inhibit T cell proliferation, indicating better anti-inflammatory activity and its suitability as a viable bioisostere in this context. This study proposes SF5 as a novel superior 19F MR reporter group for the MS drug teriflunomide.

Keywords: SF5, teriflunomide, DHODH, fluorine, MRI, MRS

More than one-third of prescribed drugs contain fluorine (19F), which generally improves their pharmacokinetic properties.1−5 Fluorination also opens an opportunity to noninvasively study drugs in vivo using 19F magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This prospect heralds an age when exact locations and concentrations of drugs can be determined in patients to inform drug therapies.2−8 The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) achieved with 19F MRI is limited because of the low availability of 19F nuclei in vivo. Additionally, specific 19F magnetic resonance (MR) properties (chemical shift, spectral shape, e.g., full width at half maximum or FWHM, spin–lattice (T1) and spin–spin (T2) relaxation times) and pharmacological properties (metabolism, protein binding, etc.) could influence SNR and 19F MR signal detection.

The application of 19F MRI continues to expand, e.g., to track immunotherapies,9 investigate temperature-dependent molecular switches,10 image tumors using pH-responsive probes,11 or monitor inflammatory processes in vivo.12,13 The implications of 19F MR methods to study physiological, enzymatic, and other metabolic processes in vitro and in vivo have long been recognized.1,14 Molecular modifications involving introduction of 19F side groups have served several purposes, e.g., as diagnostic biomarkers, where 19F tracers or contrast agents are implemented to interrogate function in biological systems.1

Fluorinated drugs can be detected in vivo using 19F MR spectroscopy (MRS) methods.15 Recently, we detected teriflunomide (TF), a dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) inhibitor, in an animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS) using nonlocalized 19F MRS.16 TF inhibits the mitochondrial DHODH enzyme that catalyzes the synthesis of the pyrimidine nucleotide precursor orotate necessary for DNA replication, including CNS-specific T cells that are key players in the MS pathology, thereby exerting its anti-inflammatory action in MS.17 Despite recent advances to improve radiofrequency coil sensitivities,18 there are still limitations that impede detection of 19F drugs in vivo with 19F MRI or localized 19F MRS, while these methods will be essential to locate drugs within specific tissue and study their distribution in vivo. SNR was a major limitation in our previous study due to the low TF availability in vivo, thereby prohibiting imaging or localized MRS to specify its location in vivo.16

The pentafluorosulfanyl (SF5) group has gained an immanent role in organic materials, polymers, and liquid crystals and has also recently emerged as a bioisostere for lipophilic groups like CF3, tert-butyl, halogen, or nitro groups in biologically active compounds.19 SF6 has been studied extensively in the gas phase as a diagnostic tool for pulmonary 19F MRI.20−25 However, surprisingly, the corresponding derived organic -SF5 group has thus far not been investigated as a 19F MRI reporter group.

In this study, we investigated different modifications to the CF3 group of TF. This included the addition of two symmetrical CF3 groups to increase the number of 19F atoms and the introduction of a SF5 group and a trifluoromethoxy-group to probe the effects of altering the chemical environment of 19F atoms while leaving their number constant, to improve their SNR and promote drug monitoring in vivo. In parallel, we also aimed to preserve or even improve the pharmacological activity of TF. Generally, the introduction of fluorine substituents enhances the potency of DHODH inhibition of TF.26 Here, the CF3 group plays an important role in stabilizing the bioactive conformation of TF.27 The SF5 group can be considered a bioisostere of CF3-groups in drug compounds.28 After a thorough characterization of the pharmacological properties and 19F MR properties of the synthesized derivatives, we selected and optimized suitable MR sequences, compared their SNR efficiency in imaging the derivatives, and aligned this with their capacity to inhibit T cell proliferation. Ultimately, we selected the best suited candidate for an ex vivo demonstration of 19F MRI in the murine stomach.

Experimental Section

Synthesis of TF and Its Derivatives

Fluorinated anilines were coupled with isoxazol acid chloride by a Schotten–Baumann reaction,29,30 and the isoxazol ring of the resulting leflunomide prodrug structure was hydrolyzed for conversion into the teriflunomide derivatives31 (Supporting Information: Chemistry, Figure S1). Derivatives of TF (Figure 1) resulted from a substitution of the para CF3-group on the benzene ring with a trifluoromethoxy CF3O-R group, two chemically symmetrical meta CF3 groups, and one para pentafluorosulfanyl SF5 group.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the synthesized teriflunomide derivatives.

Pharmacological Activity

The inhibitory activity of TF derivatives on the DHODH enzyme was measured with a colorimetric enzyme activity assay. Drug concentration ranged from 50 μM serially diluted in DMSO to 4.9 nM with a final DMSO concentration of 1%. DHODH inhibition was studied by monitoring the reduction of 2,6-dichloroindophenol (DCIP) (Alfa Aesar) via color change (blue to colorless, loss of absorbance at 620 nm). The colorimetric reaction is associated with the oxidation of l-dihydroorotate (l-DHO) (Alfa Aesar) that is catalyzed by the DHODH enzyme.32−35 The reaction was performed in duplicate in volumes of 30 μL in a 384-well plate in 50 mM tris–HCl buffer, containing 73 nM coenzyme Q10 (Selleckchem), 0.1% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), 150 mM KCl (Sigma-Aldrich), 211 nM DCIP (Thermo Fisher), and 7.5 nM DHODH (Biozol). The reaction was started by the addition of the substrate l-DHO, performed at 30 °C, and monitored over 60 min using a Tecan Safire2 Multimode Microplate Reader (Tecan).

Biological Activity

The inhibitory activity of TF derivatives on T cell proliferation was studied after isolating peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy volunteers. Informed, signed consent was obtained for collecting blood samples. Approval was granted from the ethics commission of the Charité (EA1/023/15). Compounds were dissolved in DMSO (19 mM) and further diluted to final concentrations ranging from 0.39 to 50 μM.36 Compounds (10 μL) were plated on 96-well plates and stored at 4 °C.

Blood (in EDTA) was withdrawn from two male healthy volunteers (aged 25–35), diluted 1:2 in PBS, and layered on Lymphopure (BioLegend) for separating cell populations using the principle of Ficoll density gradient centrifugation (764 g, 40 min, RT, no brake). PBMCs were cautiously collected from the corresponding phase and diluted in PBS. After two washing steps in PBS, the cell pellet was resuspended in a HEPES–RPMI 1640 buffer and counted using a Neubauer cell-counting chamber.

Isolated PBMCs were labeled with carboxyfluoresceinsuccinimidylester (CFSE) (BioLegend) as described elsewhere.37 The fluorescent dye CFSE is taken up into the cells. Dilutions of CFSE in daughter cells (1:2 as a result of cell division) result in sequential losses in fluorescence intensities. Labeling was performed according to the manufacturer’s descriptions using 5 μM CFSE, and staining was quenched using a medium containing 10% FCS. Cells were recounted and resuspended in a cell culture medium (5% human AB serum, 1% GlutaMax (×100, Gibco), 10 mM HEPES (Gibco), and 1% penicillin (10 U/μL)/streptomycin (10 μg/μL) (Gibco) in an RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco)) at a concentration of 106 cells/mL. To induce T cell proliferation, isolated PBMCs were incubated with the superantigen-similar polyclonal stimulating reagent CytoStim (Miltenyi Biotec) following the manufacturer’s instructions. CytoStim was added to the cell suspensions (0.2%).

Cells with or without CytoStim were distributed in 96-well plates (in triplicate, with final volumes of 200 μL per well) and kept at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 72 h. Wells without DHODH inhibitors (TF or its derivates) served as positive proliferation controls, and wells without T cell stimuli and inhibitors served as negative controls. After incubation, cells were centrifuged, washed with PBS, and resuspended in FACS buffer (0.5% BSA and 0.1% NaN3 (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS). Propidium iodide (PI) (BioLegend) was added to each well approximately 5 min before the measurement to stain the dead cell population. The fluorescence of CFSE labeling and PI staining was analyzed by flow cytometry using a BD LSRFortessa flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

MR Methods

MR experiments were performed on a 9.4 T MR scanner (Bruker Biospec, Ettlingen, Germany). All DHODH inhibitors (TF or its derivates) were diluted in either 100% DMSO (Roth) or 100% human serum. The human serum was prepared from whole blood withdrawn from a male healthy volunteer (aged 25) and allowed to stand for 15–30 min at room temperature; following centrifugation (21.1 g, 10 min, RT), the supernatant (serum) was transferred into a new container. Serum samples were stored at −20 °C. Phantoms were prepared in 2 and 1 mL syringes to characterize the spectra, chemical shifts, relaxation times, and signal-to-noise (SNR) efficiencies. Teriflunomide (Sigma-Aldrich and Genzyme) was used as a reference compound. Concentrations of the compounds were adjusted as indicated in Table S1.

For phantom experiments, a home-built dual-tunable 19F/1H mouse head RF coil was used.12 MR measurements were performed at room temperature (RT).

A global single pulse spectroscopy (TR = 1000 ms, TA = 8 s, nominal flip angle (FA) = 90°, block pulse, 4096 points, dwell time = 0.02 ms, excitation pulse = 10,000 Hz, spectral bandwidth = 25,000 Hz) was used to detect the 19F signal and to make frequency adjustments. Chemical shifts are referenced to trichlorofluoromethane, CFCl3 (δF = 0 ppm).

For determining T1 in low concentrated serum samples, global spectroscopy with different TRs (TR = 50–8000 ms) was used. For spectroscopically determining T2, a CPMG sequence was used (TR = 5000 ms, 25 echoes, echo spacing = 2.8 ms, excitation pulse = 5000 Hz, spectral bandwidth = 25,000 Hz).

T1 mapping was performed using RARE (rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement): TE = 4.6 ms, echo train length (ETL) = 4, FOV = [16 × 16] mm2, matrix size = 64 × 64, with 9 variable repetitions times (TR = 25–8000 ms). T2 mapping was performed using a multislice multiecho sequence: TR = 2000 ms, FOV = [16 × 16] mm2, matrix size = 64 × 64, with 25 different TEs (TE = 40–1000 ms in steps of 40 ms for long T2 and TE = 8–200 ms in steps of 8 ms for short T2).

To determine the most SNR efficient MR technique for acquiring 19F MRI of TF and its derivatives, we optimized the parameters (Table S3) of three MR sequences: RARE, bSSFP (balanced steady-state free precession), and UTE (ultrashort echo time). For all methods, the image geometry was set to FOV = [28 × 28] mm2, matrix size = 96 × 96 in DMSO, matrix size = 64 × 64 in serum, and slice thickness = 5 mm. Pulse sequence parameters were optimized based on the relaxation times of each compound in DMSO and serum.38,39

For RARE, the receiver bandwidth was set to 10 kHz to maximize SNR but limit chemical shift artifacts. Centric encoding was used, and the echo spacing was kept minimal for both long T2 conditions, i.e., in DMSO (TEDMSO = 12.12 ms), and short T2 conditions, i.e., in serum (TEserum = 2.29 ms). For the latter condition, a RARE sequence with gradient pulses optimized for short echo spacing (RAREst) was used. We used a flip-back module and, based on simulations, chose the highest possible ETL with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the point spread function (PSF) below 1.5 pixels. Given these parameters, we optimized the repetition time (TR) based on the steady state signal intensity equation.38

For bSSFP, the receiver bandwidth was set to 100 kHz to achieve a short TR = 2.6 ms (TE = 1.3 ms) and thus stability regarding banding artifacts. For each compound and condition, the flip angle αbSSFP was adjusted to

For UTE, we used an FID readout (TE = 0.27 ms) and a read bandwidth of 20 kHz. We used TR = 100 ms and the calculated Ernst angle αE as the flip angle

Animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the procedures approved by the Animal Welfare Department of the State Office for Health and Social Affairs Berlin (LAGeSo) and conformed to guidelines to minimize discomfort to animals (86/609/EEC).

The same molar concentrations of TF (12.15 mg/mL) and SF5-TF (10 mg/mL) suspended in 0.6% carboxymethyl cellulose were administered orally (bolus volume of 800 μL) to an anesthetized (intraperitoneal injection, 7.5 mg/kg of xylazine and 100 mg/kg of ketamine in NaCl) C57BL/6N mouse. After 20 min, the animal was sacrificed by an overdose of the anesthetic, the esophagus and duodenum were closed with a surgical suture, and the stomach was removed. An ex vivo phantom was prepared in a 5 mL tube filled with 4% paraformaldehyde (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). We used RARE for anatomical 1H MRI of the stomach: TR/TE = 2000 ms/10 ms; TA = 1 min, 4 s; FOV = [28 × 28] mm2, and matrix = 256 × 256, slice thickness = 0.5 mm, and an optimized UTE sequence for 19F MRI of TF and SF5-TF: TR/TE = 100 ms/0.27 ms; TA = 2 h, 30 min, slice thickness = 5 mm, FATF = 25°, FASF5-TF = 42°, FOV = [28 × 28] mm2, and matrix = 32 × 32.

Data Analysis

For DHODH activity, time–absorbance curves reflect the enzymatic activity over time. We calculated the initial slope of these curves to quantify the initial velocity of the enzyme reaction. A Z′ factor was calculated40 using an in-house online Z′ calculator to assess the quality of the screening method (http://www.screeningunit-fmp.net/tools/z-prime.php). Screening assays with Z′ values between 0.5 and 1 are categorized as excellent.40

For T cell proliferation, we analyzed flow cytometry data using FlowJo (software version 10.5.3, FlowJo LLC, Figure S2). The lymphocyte population was selected from the forward (FSC-A)/sideward scatter (SSC-A) and gated for single cells (FSC-A/FSC-H). Dead cells were excluded by gating for the cell population SSC-A/PI without PI staining. From this population, the CFSE-labeled cells were gated and displayed in a histogram, dividing the different generations of cells from cell divisions. The percentage of proliferating cells in relation to the originally labeled parental cell population was calculated.

A Z′ factor (see the DHODH assay) was calculated from the number of proliferating cells in unstimulated negative and stimulated untreated positive controls. Additionally, the stimulation index (SI) was determined from the proportion of proliferating cells from nonproliferating ones

|

Data from triplicates from each donor were combined so that each concentration point is represented by three measurement points.

MR image processing and spectral analysis and processing were performed in MATLAB R2018a (MathWorks, Inc.). MR data was analyzed as detailed in our previous work.41 Briefly, we quantified the spectral signal intensity, performed a Fourier transform to obtain magnitude spectra, and determined the chemical shift. We estimated the T1 and T2 time constants by fitting the measured signal intensities in MR magnitude images to the equations for T1 and T2 relaxations. SNR estimations for RARE, bSSFP, and UTE measurements and image preparation of ex vivo samples were performed as previously described.42 ImageJ43 was used for further image analysis. We calculated the SNR efficiency (SNR/sqrt(time)) per mol to determine the compounds beneficial for in vivo application.

Results and Discussion

Inhibitory Activity of TF Derivatives In Vitro

The trifluoromethoxy-substituted TF (CF3O-TF) and pentafluorosulfanyl-substituted TF (SF5-TF) demonstrated equal or even better pharmacological and antiproliferative activities compared to TF (CF3-TF) as shown by the IC50 values for DHODH inhibition in in vitro enzyme and proliferation assays (Table 1). We calculated the IC50 values for pharmacological DHODH inhibitory activity from dose–response curves and by fitting a dose–response model to the data points (Figure S3). The impact of TF and its derivates to inhibit T cell proliferation was also determined from the IC50 values from dose–response curves and by fitting a dose–response model to the data points (Figure S3). The T cell stimulation index yielded 47.3.

Table 1. IC50 Values and Confidence Intervals of the Enzyme Inhibition and Cell Proliferation Assaysa.

| DHODH inhibition | cell proliferation inhibition | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | IC50 [μM] | lower limit CI [μM] | upper limit CI [μM] | IC50 [μM] | lower limit CI [μM] | upper limit CI [μM] |

| TF | 0.54 | 0.32 | 0.77 | 24.25 | 19.01 | 29.52 |

| CF3O-TF | 0.33 | 0.11 | 0.55 | 10.98 | 8.65 | 13.31 |

| di-CF3-TF | 1.32 | 0.53 | 2.11 | 39.73 | 6.88 | 72.60 |

| SF5-TF | 0.58 | 0.42 | 0.73 | 8.48 | 8.04 | 8.92 |

The Z′ value for the proliferation assay was 0.893, which is comparable to the Z’ value obtained in the enzyme inhibition assay. A Z′ value of >0.5 confirms the robustness of the assay. Therefore, unstimulated cells could be safely discriminated from stimulated controls.

For TF and its derivatives, we calculated the IC50 values and 95% confidence intervals, for both DHODH and T cell proliferation assays (Figure S3). The activity of CF3O-TF to inhibit DHODH was marginally higher than that of TF as shown by the lower IC50, while that of SF5-TF was similar, and that of the difluoromethyl-substituted di-CF3-TF was lower (Figure S3 and Table 1). In T cell proliferation experiments, both CF3O-TF and SF5-TF showed a considerably greater inhibitory activity than TF, as shown by the dose–response curves (Figure S3B) and IC50 values (Table 1). Compared to TF, SF5-TF revealed the best inhibitory activity (IC50 8.48 μM).

Substitution of the CF3 group with a SF5 group is expected to result in changes in the side chain geometry and electron density. The SF5 group is characterized by a higher electronegativity and lipophilicity.19 The increased T cell inhibitory activity by SF5-TF suggests an increased cellular uptake in T cells as a result of more efficient permeation through cell membranes due to increased lipophilicity, as has been shown in trypanothione reductase inhibitors exhibiting increased cellular activity and membrane permeability following introduction of SF5.44

We also performed a cell growth inhibition and cytotoxicity test in HepG2 cells (Supporting Information: Toxicology). All compounds showed a similar impact on cancer cell growth and cytotoxicity to that of TF (Figure S4). While T cell inhibitory activity of SF5-TF was enhanced, its impact on cytotoxicity was similar to that of TF. Furthermore, nucleic acid staining using propidium iodide (PI) did not reveal cytotoxic effects in T cells, even at higher concentrations (Figure S5).

19F MR Relaxation and Chemical Shifts of TF Derivatives

We studied the 19F MR properties of all TF derivatives in DMSO and in human serum. We used serum to simulate the in vivo situation. When TF is administered to patients, it becomes strongly protein bound (e.g., in blood, it is >99% bound to protein45). Since the solubility of TF compounds in serum was lower than in DMSO, lower concentrations of TF compounds were available in serum (Table S1); this resulted in an expected lower SNR (Figure S6). TF, CF3O-TF, and di-CF3-TF exhibit a single peak at −58, −55, and −59 ppm, respectively, in DMSO (Figure 2). SF5-TF shows a main peak at 67.4 ppm and a smaller peak at 91.7 ppm at a ratio of 4:1 (Figure 2 and Figure S7). Due to the geometric orientation of the five fluorine atoms to the phenyl moiety, one positioned axially and four in equatorial positions, the main peak shows a line splitting (doublet) and the smaller peak shows an apparent 1:4:6:4:1 intensity pentet (Figure S7).46

Figure 2.

19F MR spectra of teriflunomide and its derivatives. Signal acquired (normalized amplitudes) from compounds dissolved in DMSO (upper panels) or human serum (lower panels) obtained by a global single-pulse spectroscopy (TR = 1000 ms and TA = 8000 ms).

Spectra of the compounds solubilized in serum were similar to those in DMSO; although we observed a slight change in the chemical shift and peak broadening (Figure 2, lower panels), also quantified from the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the peaks (Table S2).

Interestingly, increasing the number of fluorine atoms on a drug structure is not the only factor that affects the effective SNR. Our results indicate that addition of the SF5-group to the molecular structure reduces both the transversal relaxation time T2 and longitudinal relaxation time T1.

Spin–lattice relaxation times (T1) were measured for all TF derivatives (Table 2). Compared to TF in DMSO, di-CF3-TF had an almost equal T1 relaxation time, CF3O-TF had a prolonged T1 relaxation time, and SF5-TF had a substantially reduced T1 relaxation time. In serum, T1 was equal for TF but was reduced for CF3O-TF, di-CF3-TF, and SF5-TF, compared to the same compounds in DMSO.

Table 2. Comparison of T1 and T2 Relaxation Times in DMSO and Serum of TF and Its Derivatives to Optimize the SNR Efficiency of the 19F MR Acquisition Method.

| T1 (ms) | T2 (ms) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | DMSO | serum | DMSO | serum |

| TF | 1003 | 1017 | 508 | 5 |

| CF3O-TF | 1666 | 753 | 942 | 8 |

| di-CF3-TF | 1098 | 875 | 642 | 5 |

| SF5-TF | 371 | 331 | 68 | 6 |

Spin–spin relaxation times (T2) were also measured for all compounds (Table 2). Compared to TF in DMSO, CF3O-TF and di-CF3-TF had longer spin–spin relaxations, while SF5-TF had a markedly shorter spin–spin relaxation. The T2 in serum also dramatically dropped to values between 5 and 8 ms.

While a reduction in T2 requires MR methods with faster signal acquisition (e.g., UTE), a reduction in T1 reduces the time required between different excitations, thereby enabling more efficient data acquisition. The reductions in relaxation times could be attributed to dipole–dipole interactions and chemical shift anisotropy.47,48 Besides modifications of side chains, the addition of a paramagnetic dopant such as lanthanide chelates, in particular, gadolinium-containing contrast agents, has been used for shortening the T1.(49) For 19F MR applications, 19F nanoparticles were functionalized with Gd(III) complexes for modulating the 19F signal.50 Increased 19F MR signals from 19F nanoparticles were observed in close proximity to blood–brain barrier disruptions, indicating a T1 shortening effect not only for 1H but also for19F as a result of the paramagnetic contrast agent Gd–DTPA leakage.51

Impact of Serum on 19F MR Relaxation

Differences in chemical shifts and relaxation times can be attributed to the different physicochemical properties of the 19F groups. These properties were also severely affected by the serum environment. SF5-TF is administered as a suspension, and SF6 is administered as a gas. All six fluorines on SF6 produce one signal, whereas the SF5 group has an AX4 spin system and produces two separate signals. Most notably, the 19F T2 relaxation times of TF and its derivatives were drastically shortened in serum. The increase in FWHM of the 19F MR spectra in the serum compared to DMSO also suggests a T2* shortening.52 The observed shortening in relaxation is presumably attributed to unspecific binding of the compounds to serum proteins.53 Similar to SF5-substituted TF, the fluorinated gas SF6 exhibits a short transversal relaxation time.20 SF5 is an organic derivative of SF6 in which one of the fluorine atoms is replaced by an organic residue. However, there are notable T1 and T2 differences between SF5-TF and SF6.20,21 At 9.4 T, the T1 of SF6 at room temperature (300 K) was reported to be <200 ms21 and is even shorter (1.24 ms at 1.9 T) when administered to rats as a gas (80%, 630 Torr barometric pressure).20 The T1 of SF5-TF was not strongly reduced in the presence of serum (Table 2), and we would expect similar values for this compound in vivo. On the other hand, the T2 of SF5-TF was strongly reduced (by 90%) in the presence of serum. Differences between SF5-TF and SF6 with respect to T1 and T2 can be attributed to differences in chemical environments.23

Recently, we could detect TF in vivo when employing 19F MRS.16 The above limitations in relaxation times, particularly when protein bound, restrict SNR. Due to the associated rapid loss in 19F signal during T2 relaxation, signal detection with 19F MRI is expected to be more challenging.

Optimization of 19F MR Parameters

We used the determined 19F relaxation times for TF and its derivatives to calculate the most efficient parameters for three 19F MRI acquisition methods: rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE), balanced steady-state free precession (SSFP), and ultrashort echo time (UTE) (Table S3). Selection of the appropriate MR acquisition method according to the MR properties of the compound within a specific environment is essential to acquire data with the best SNR efficiency. A thorough characterization of 19F compounds41 is typically necessary to adapt SNR efficient 19F MR acquisition methods to the specific MR characteristics of these compounds.38

We acquired 19F MR images of all compounds using the corresponding optimized sequences (Figure S6) and compared SNR efficiencies (SNR per molecule divided by the square root of the acquisition time) to identify the most suited method for each compound, in DMSO and in serum (Table 3). In DMSO, RARE yielded the best SNR efficiency for all compounds, followed by bSSFP and UTE. In DMSO, di-CF3-TF showed the best SNR efficiency performance compared to TF. In serum, UTE was the MR acquisition method that provided the best SNR efficiency for all TF compounds, particularly for SF5-TF. The SF5-substituted derivative showed a gain in 19F SNR efficiency of ∼3 compared to TF when using the UTE 19F MRI method. This translates into a 9-fold reduction in measurement time, which is the primary obstacle of 19F MRI for both clinical and preclinical applications. In addition, the SF5-TF also showed an increase of ∼3 in inhibiting T cell proliferation.

Table 3. SNR Comparison Using Optimized RARE, bSSFP, and UTE Protocols Studying the SNR Efficiency of Compounds (Using SNR per Molecule) in DMSO and in Serum (in % Normalized to TF RARE).

| RARE | bSSFP | UTE | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | DMSO | serum | DMSO | serum | DMSO | serum |

| TF | 100 | 100 | 63 | 9 | 17 | 163 |

| CF3O-TF | 106 | 101 | 55 | 20 | 14 | 148 |

| di-CF3-TF | 200 | 162 | 130 | 34 | 33 | 240 |

| SF5-TF | 68 | 76 | 74 | 26 | 32 | 363 |

One interpretation of these results is that the increased activity of SF5-TF could allow a lower dose to be used while maintaining the same level of therapeutic efficacy. However, a randomized clinical study following 12–14 years of TF treatment showed that a larger proportion of MS patients (51.5%) were relapse-free when receiving 14 mg of teriflunomide, compared to those receiving 7 mg of TF (39.5%).54,55 Thus, the higher efficacy of SF5-TF might have downstream benefits for MS patients, and future in vivo experiments in the animal model will be needed to clarify whether SF5-TF administered at the same dose as TF will be more efficacious at treating neurological diseases. Apart from a ∼3× gain in the 19F SNR efficiency in vitro, we observed an SNR gain of ∼2 for SF5-TF compared to TF in the stomach ex vivo. This variation in the SNR gain could reflect variations in pH in the stomach that could affect relaxation times of TF.16 Future comparative studies are needed to focus on organ systems more relevant to the pathophysiology of MS such as the CNS.

Biological and 19F MR Reporter Activities of TF Compounds

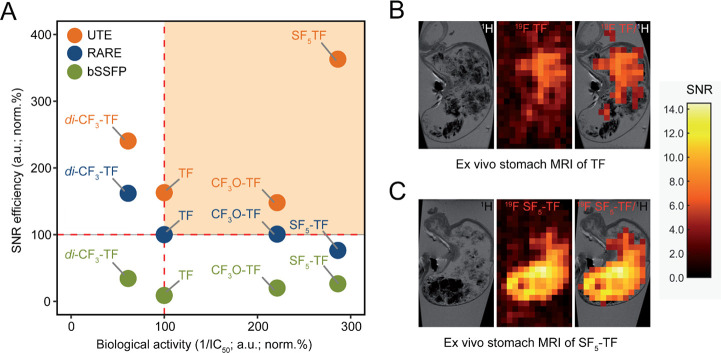

We aligned the biological activity with SNR efficiency of all 19F MRI acquisition methods when comparing TF with its substituted derivatives (Figure 3A). Compared to all compounds, SF5-TF showed a clear enhancement in the T cell proliferation inhibitory activity, as well as SNR efficiency under serum conditions when using a UTE sequence. We administered TF and SF5-TF orally to C57BL/6 mice using the same molar concentrations (TF =12.15 mg/mL (n = 3) and SF5-TF = 10 mg/mL (n = 3)) and acquired 19F MR images of the stomachs ex vivo using the optimized parameters (Figure 3B,C). We observed a clear distribution of both TF and SF5-TF in the stomach and measured peak SNR values of 13.2 ± 1.2 (mean ± maximum absolute deviation) for SF5-TF in the stomach, compared to 5.8 ± 2.9 for TF (MR Characterization, Figure S8 and Table S4).

Figure 3.

Biological and 19F MR reporter activities of TF compounds. (A) Selecting the best 19F TF derivative and corresponding MR acquisition method. Drug compounds with the best inhibitory capacity (inverse IC50 normalized to TF in percentage) and best SNR efficiency in serum (normalized to TF in percentage using a RARE sequence) obtained using RARE, bSSFP, and UTE sequences are shown in the upper right quadrant (orange region). (B)19F MR reporter activity of TF in the stomach of a C57BL/6 mouse ex vivo using an optimized 19F UTE MR sequence. Left panel: 1H anatomical image of the stomach, middle panel: 19F MRI of TF in the stomach, and right panel: 19F/1H overlay. 1H: RARE (TR/TE = 2000 ms/10 ms, TA = 1 min, 4 s) and 19F: UTE (TR/TE = 100 ms/0.27 ms, TA = 2 h, 30 min, FA = 25 °). (C) 19F MR reporter activity of SF5-TF in the stomach of a C57BL/6 mouse ex vivo using an optimized 19F UTE MR sequence. Left panel: 1H anatomical image of the stomach, middle panel: 19F MRI of SF5-TF in the stomach, and right panel: 19F/1H overlay. 1H: RARE (TR/TE = 2000 ms/10 ms, TA = 1 min, 4 s) and 19F: UTE (TR/TE = 100 ms/0.27 ms, TA = 2 h, 30 min, FA = 42 °). SNR is indicated by the color bars.

Conclusions

In this study, we introduced modifications, including those of SF5, to a pharmacologically active compound, to increase detection in vivo. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has performed an in-depth investigation of 19F modifications on pharmacological and biological activities, alongside the MR reporter function. Here, we addressed SNR by modifying the CF3 side chain of TF to vary the 19F MR properties and identify potential SNR-boosting derivatives. Substituting the CF3 side chain by CF3O, SF5, or di-CF3 did not compromise the pharmacological and antiproliferative activities. Of note, the superiority of the SF5-substituted derivative to inhibit T cell proliferation compared to TF indicates that some fluorination strategies might even improve the biological function.

Our study indicates SF5 as a potential theranostic marker for detecting and studying the biodistribution of fluorinated drugs noninvasively, particularly during pathology. However, in vivo studies will now be necessary to study the versatility of the SF5 bioisostere in combination with the UTE method for in vivo 19F MRI and to determine its superiority over teriflunomide to treat disease in the animal model of multiple sclerosis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Peter Schmieder (FMP) for supporting the NMR analysis of the compounds.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 19F

fluorine-19

- 1H

hydrogen-1/proton

- bSSFP

balanced steady-state free precession

- CF3

trifluoromethyl

- CFSE

carboxyfluoresceinsuccinimidylester

- DCIP

dichloroindophenol

- DHODH

dihydroorotate dehydrogenase

- DMSO

dimethylsulfoxide

- FA

flip angle

- FID

free induction decay

- FOV

field of view

- FWHM

full width at half maximum

- IC50

inhibitory concentration (50%)

- l-DHO

l-dihydroorotate

- MR

magnetic resonance

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- PBMCs

peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PSF

point-spread-function

- RARE

rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement

- RF

radiofrequency

- RT

room temperature

- SF5

pentafluorosulfanyl

- SNR

signal-to-noise ratio

- TA

acquisition time

- TE

echo time

- TF

teriflunomide

- TR

repetition time

- UTE

ultrashort echo time

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssensors.1c01024.

Supplemental methods and results (chemistry, flow cytometry, enzyme and T cell growth inhibition, toxicology, and MR characterization) (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions from all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This work was supported by funding from the Germany Research Council (DFG WA2804). This project has received funding in part (T.N. and J.M.M.) from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 743077 (ThermalMR).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ruiz-Cabello J.; Barnett B. P.; Bottomley P. A.; Bulte J. W. M. Fluorine 19F MRS and MRI in biomedicine. NMR Biomed. 2011, 24, 114–129. 10.1002/nbm.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. G.; Murphy P. S. Fluorine magnetic resonance in vivo: a powerful tool in the study of drug distribution and metabolism. Drug Discovery Today 2008, 13, 473–480. 10.1016/j.drudis.2007.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller K.; Faeh C.; Diederich F. Fluorine in pharmaceuticals: looking beyond intuition. Science 2007, 317, 1881–1886. 10.1126/science.1131943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Sanchez-Rosello M.; Acena J. L.; del Pozo C.; Sorochinsky A. E.; Fustero S.; Soloshonok V. A.; Liu H. Fluorine in pharmaceutical industry: fluorine-containing drugs introduced to the market in the last decade (2001-2011). Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2432–2506. 10.1021/cr4002879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niendorf T.; Ji Y.; Waiczies S., Chapter 11 Fluorinated Natural Compounds and Synthetic Drugs. In Fluorine Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 1 ed.; Ahrens E. T.; Flögel U. Ed. Pan Stanford Publishing: 2016; pp. 311–344, 10.1201/9781315364605-12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf W.; Presant C. A.; Waluch V. 19F-MRS studies of fluorinated drugs in humans. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2000, 41, 55–74. 10.1016/S0169-409X(99)00056-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H.; Viel S.; Ziarelli F.; Peng L. 19F NMR: a valuable tool for studying biological events. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 7971–7982. 10.1039/c3cs60129c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartusik D.; Aebisher D. 19F applications in drug development and imaging - a review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2014, 68, 813–817. 10.1016/j.biopha.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens E. T.; Helfer B. M.; O’Hanlon C. F.; Schirda C. Clinical cell therapy imaging using a perfluorocarbon tracer and fluorine-19 MRI. Magn Reson Med 2014, 72, 1696–1701. 10.1002/mrm.25454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieger A.; Wiester M. J.; Procissi D.; Parrish T. B.; Mirkin C. A.; Thaxton C. S. Hybridization-induced ″off-on″ 19F-NMR signal probe release from DNA-functionalized gold nanoparticles. Small 2011, 7, 1977–1981. 10.1002/smll.201100566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Li L.; Han F. Y.; Yu X.; Tan X.; Fu C.; Xu Z. P.; Whittaker A. K. Integrating Fluorinated Polymer and Manganese-Layered Double Hydroxide Nanoparticles as pH-activated 19F MRI Agents for Specific and Sensitive Detection of Breast Cancer. Small 2019, 15, e1902309 10.1002/smll.201902309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waiczies H.; Lepore S.; Drechsler S.; Qadri F.; Purfurst B.; Sydow K.; Dathe M.; Kuhne A.; Lindel T.; Hoffmann W.; Pohlmann A.; Niendorf T.; Waiczies S. Visualizing brain inflammation with a shingled-leg radio-frequency head probe for 19F/1H MRI. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1280. 10.1038/srep01280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flögel U.; Ding Z.; Hardung H.; Jander S.; Reichmann G.; Jacoby C.; Schubert R.; Schrader J. In vivo monitoring of inflammation after cardiac and cerebral ischemia by fluorine magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation 2008, 118, 140–148. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.737890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. X.; Hallac R. R.; Chiguru S.; Mason R. P. New frontiers and developing applications in 19F NMR. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2013, 70, 25–49. 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolo N. R.; Hode Y.; Nedelec J. F.; Laine E.; Wagner G.; Macher J. P. Brain pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution in vivo of fluvoxamine and fluoxetine by fluorine magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Neuropsychopharmacology 2000, 23, 428–438. 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00116-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz C.; Starke L.; Millward J. M.; Fillmer A.; Delgado P. R.; Waiczies H.; Pohlmann A.; Rothe M.; Nazare M.; Paul F.; Niendorf T.; Waiczies S. In vivo detection of teriflunomide-derived fluorine signal during neuroinflammation using fluorine MR spectroscopy. Theranostics 2021, 11, 2490–2504. 10.7150/thno.47130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiese M. D.; Rowland A.; Polasek T. M.; Sorich M. J.; O’Doherty C. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of teriflunomide for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 2013, 9, 1025–1035. 10.1517/17425255.2013.800483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waiczies S.; Millward J. M.; Starke L.; Delgado P. R.; Huelnhagen T.; Prinz C.; Marek D.; Wecker D.; Wissmann R.; Koch S. P.; Boehm-Sturm P.; Waiczies H.; Niendorf T.; Pohlmann A. Enhanced Fluorine-19 MRI Sensitivity using a Cryogenic Radiofrequency Probe: Technical Developments and Ex Vivo Demonstration in a Mouse Model of Neuroinflammation. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 9808. 10.1038/s41598-017-09622-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowaileh M. F.; Hazlitt R. A.; Colby D. A. Application of the Pentafluorosulfanyl Group as a Bioisosteric Replacement. ChemMedChem 2017, 12, 1481–1490. 10.1002/cmdc.201700356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adolphi N. L.; Kuethe D. O. Quantitative mapping of ventilation-perfusion ratios in lungs by 19F MR imaging of T1 of inert fluorinated gases. Magn Reson Med 2008, 59, 739–746. 10.1002/mrm.21579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson P.; Javed M. A.; Komulainen S.; Chen L.; Holden D.; Hasell T.; Cooper A.; Lantto P.; Telkki V. V. NMR relaxation and modelling study of the dynamics of SF(6) and Xe in porous organic cages. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 24373–24382. 10.1039/C9CP04379A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couch M. J.; Ball I. K.; Li T.; Fox M. S.; Biman B.; Albert M. S. 19F MRI of the Lungs Using Inert Fluorinated Gases: Challenges and New Developments. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019, 49, 343–354. 10.1002/jmri.26292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassetto M.; Ferla S.; Pertusati F. Polyfluorinated groups in medicinal chemistry. Future Med. Chem. 2015, 7, 527–546. 10.4155/fmc.15.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf U.; Scholz A.; Heussel C. P.; Markstaller K.; Schreiber W. G. Subsecond fluorine-19 MRI of the lung. Magn Reson Med 2006, 55, 948–951. 10.1002/mrm.20859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuethe D. O.; Caprihan A.; Gach H. M.; Lowe I. J.; Fukushima E. Imaging obstructed ventilation with NMR using inert fluorinated gases. J. Appl. Physiol. 2000, 88, 2279–2286. 10.1152/jappl.2000.88.6.2279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner R.; Walloschek M.; Kralik M.; Gotschlich A.; Tasler S.; Mies J.; Leban J. Dual binding mode of a novel series of DHODH inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 1239–1247. 10.1021/jm0506975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomo S.; Tosco P.; Giorgis M.; Lolli M.; Fruttero R. The role of fluorine in stabilizing the bioactive conformation of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors. J. Mol. Model. 2013, 19, 1099–1107. 10.1007/s00894-012-1643-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westphal M. V.; Wolfstadter B. T.; Plancher J. M.; Gatfield J.; Carreira E. M. Evaluation of tert-butyl isosteres: case studies of physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties, efficacies, and activities. ChemMedChem 2015, 10, 461–469. 10.1002/cmdc.201402502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avrutov I.; Gershon N.; Liberman A.. Method for synthesizing leflunomide. Patent 2002, US20020022646A1

- Frantz D. E.; Weaver D. G.; Carey J. P.; Kress M. H.; Dolling U. H. Practical synthesis of aryl triflates under aqueous conditions. Org. Lett. 2002, 4, 4717–4718. 10.1021/ol027154z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palle V. R.; Bhat R. P.; Kaliappan M.; Babu J. R.; Shanmughasamy R.. A novel process for the preparation of teriflunomide. Patent 2016, WO 2016203410 A1

- Sainas S.; Pippione A. C.; Giorgis M.; Lupino E.; Goyal P.; Ramondetti C.; Buccinnà B.; Piccinini M.; Braga R. C.; Andrade C. H.; Andersson M.; Moritzer A.-C.; Friemann R.; Mensa S.; Al-Kadaraghi S.; Boschi D.; Lolli M. L. Design, synthesis, biological evaluation and X-ray structural studies of potent human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibitors based on hydroxylated azole scaffolds. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 129, 287–302. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladds M.; van Leeuwen I. M. M.; Drummond C. J.; Chu S.; Healy A. R.; Popova G.; Pastor Fernandez A.; Mollick T.; Darekar S.; Sedimbi S. K.; Nekulova M.; Sachweh M. C. C.; Campbell J.; Higgins M.; Tuck C.; Popa M.; Safont M. M.; Gelebart P.; Fandalyuk Z.; Thompson A. M.; Svensson R.; Gustavsson A. L.; Johansson L.; Farnegardh K.; Yngve U.; Saleh A.; Haraldsson M.; D’Hollander A. C. A.; Franco M.; Zhao Y.; Hakansson M.; Walse B.; Larsson K.; Peat E. M.; Pelechano V.; Lunec J.; Vojtesek B.; Carmena M.; Earnshaw W. C.; McCarthy A. R.; Westwood N. J.; Arsenian-Henriksson M.; Lane D. P.; Bhatia R.; McCormack E.; Lain S. A DHODH inhibitor increases p53 synthesis and enhances tumor cell killing by p53 degradation blockage. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1107. 10.1038/s41467-018-03441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knecht W.; Löffler M. Species-related inhibition of human and rat dihydroorotate dehydrogenase by immunosuppressive isoxazol and cinchoninic acid derivatives. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1998, 56, 1259–1264. 10.1016/S0006-2952(98)00145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland R. A.; Davis J. P.; Dowling R. L.; Lombardo D.; Murphy K. B.; Patterson T. A. Recombinant human dihydroorotate dehydrogenase: expression, purification, and characterization of a catalytically functional truncated enzyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1995, 323, 79–86. 10.1006/abbi.1995.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Liu J.; Delohery T.; Zhang D.; Arendt C.; Jones C. The effects of teriflunomide on lymphocyte subpopulations in human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in vitro. J. Neuroimmunol. 2013, 265, 82–90. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons A. B. Analysing cell division in vivo and in vitro using flow cytometric measurement of CFSE dye dilution. J. Immunol. Methods 2000, 243, 147–154. 10.1016/S0022-1759(00)00231-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber C.; Schmid F.. Chapter 1 Pulse Sequence Considerations and Schemes. In Fluorine Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Ahrens E. T.; Flögel U. Ed. Pan Stanford Publishing: 2016; pp. 3–27, 10.1201/9781315364605-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mastropietro A.; De Bernardi E.; Breschi G. L.; Zucca I.; Cametti M.; Soffientini C. D.; de Curtis M.; Terraneo G.; Metrangolo P.; Spreafico R.; Resnati G.; Baselli G. Optimization of rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement (RARE) pulse sequence parameters for 19F-MRI studies. J Magn Reson Imaging 2014, 40, 162–170. 10.1002/jmri.24347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. H.; Chung T. D. Y.; Oldenburg K. R. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen 1999, 4, 67–73. 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinz C.; Delgado P. R.; Eigentler T. W.; Starke L.; Niendorf T.; Waiczies S. Toward 19F magnetic resonance thermometry: spin-lattice and spin-spin-relaxation times and temperature dependence of fluorinated drugs at 9.4 T. MAGMA 2019, 32, 51–61. 10.1007/s10334-018-0722-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starke L.; Niendorf T.; Waiczies S., Data Preparation Protocol for Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio Fluorine-19 MRI. In Preclinical MRI of the Kidney: Methods and Protocols, Pohlmann A.; Niendorf T., Eds. Springer US: New York, NY, 2021; pp. 711–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindelin J.; Arganda-Carreras I.; Frise E.; Kaynig V.; Longair M.; Pietzsch T.; Preibisch S.; Rueden C.; Saalfeld S.; Schmid B.; Tinevez J. Y.; White D. J.; Hartenstein V.; Eliceiri K.; Tomancak P.; Cardona A. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 676–682. 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stump B.; Eberle C.; Schweizer W. B.; Kaiser M.; Brun R.; Krauth-Siegel R. L.; Lentz D.; Diederich F. Pentafluorosulfanyl as a novel building block for enzyme inhibitors: trypanothione reductase inhibition and antiprotozoal activities of diarylamines. ChemBioChem 2009, 10, 79–83. 10.1002/cbic.200800565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warnke C.; Stuve O.; Kieseier B. C. Teriflunomide for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2013, 115 Suppl 1, S90–S94. 10.1016/j.clineuro.2013.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolbier W. R., Guide to fluorine NMR for organic chemists. 2 ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, N.J., 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kadayakkara D. K.; Damodaran K.; Hitchens T. K.; Bulte J. W. M.; Ahrens E. T. 19F spin-lattice relaxation of perfluoropolyethers: Dependence on temperature and magnetic field strength (7.0-14.1T). J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 242, 18–22. 10.1016/j.jmr.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalvit C.; Vulpetti A. Fluorine-protein interactions and (1)(9)F NMR isotropic chemical shifts: An empirical correlation with implications for drug design. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 104–114. 10.1002/cmdc.201000412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aime S.; Botta M.; Fasano M.; Terreno E. Lanthanide(III) chelates for NMR biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998, 27, 19–29. 10.1039/A827019Z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries A.; Moonen R.; Yildirim M.; Langereis S.; Lamerichs R.; Pikkemaat J. A.; Baroni S.; Terreno E.; Nicolay K.; Strijkers G. J.; Grull H. Relaxometric studies of gadolinium-functionalized perfluorocarbon nanoparticles for MR imaging. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2014, 9, 83–91. 10.1002/cmmi.1541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nöth U.; Morrissey S. P.; Deichmann R.; Jung S.; Adolf H.; Haase A.; Lutz J. Perfluoro-15-Crown-5-Ether Labelled Macrophages in Adoptive Transfer Experimental Allergic Encephalomyelitis. Artif Cells Blood Substit Immobil Biotechnol 1997, 25, 243–254. 10.3109/10731199709118914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen J. F. A.; Backes W. H.; Nicolay K.; Kooi M. E. 1H MR spectroscopy of the brain: absolute quantification of metabolites. Radiology 2006, 240, 318–332. 10.1148/radiol.2402050314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois B. W.; Evers A. S. Fluorine-19 NMR spin-spin relaxation (T2) method for characterizing volatile anesthetic binding to proteins. Analysis of isoflurane binding to serum albumin. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 7069–7076. 10.1021/bi00146a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremenchutzky M.; Freedman M.; Bar-Or A.; Dukovic D.; Benamor M.; Truffinet P.; Connor P. 12-Year Clinical Efficacy and Safety Data for Teriflunomide: Results from a Phase 2 Extension Study (P7.223). Neurology 2015, 84, P7.223. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman M. S.; Bar-Or A.; Benamor M.; Truffinet P.; Poole E.; Mandel M.; Kremenchutzky M. Long-term Disability Outcomes in Patients Treated With Teriflunomide for up to 14 Years: Group- and Patient-Level Data From the Phase 2 Extension Study (P6.389). Neurology 2018, 90, P6.389. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.