Abstract

Purpose of review

The purpose of this paper is (1) to provide insight in the palliative care needs of patients with COVID-19; (2) to highlight the challenges of COVID-19 for palliative care; and (3) to highlight developments in COVID-19 palliative care.

Recent findings

Patients with serious COVID-19 have palliative care needs in all domains: physical, psychological, social and spiritual. COVID-19 palliative care is confronted with many challenges, including: the uncertain prognosis, resource limitations, challenges regarding advance care planning, lack of guidance, limited multidisciplinary collaboration, need for remote communication, restrictions in family visits, and burden for clinicians. Palliative care responded with many developments: development of services; integration of palliative care with other services; tools to support advance care planning, (remote) communication with patients and families, or spiritual care; and care for team members.

Summary

Palliative care has an important role in this pandemic. Palliative care rapidly developed services and opportunities were found to support patients, families and clinicians. Further developments are warranted to face future demands of a pandemic, including integrated palliative care and education in palliative care skills across all specialties. Intervention studies are needed to enable evidence-based recommendations for palliative care in COVID-19.

Keywords: advance care planning, COVID-19, end-of-life care, palliative care, palliative medicine

INTRODUCTION

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, millions of people worldwide have died because of COVID-19 and despite all efforts and milliards of vaccine doses administered, this number still rises every day [1]. The need for palliative care is already increasing worldwide due to the ageing population and increases in the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases. Progress has been made, especially in high-income countries, to meet the palliative care needs of patients with cancer and other (chronic) noncommunicable and life-limiting diseases [2]. However, the recent COVID-19 pandemic resulted in many people with an acute infectious illness being in need for palliative care. Mortality is highest among male patients, people of old age and people with chronic or malignant diseases [3,4]. Most people die because of respiratory failure, myocardial damage or failure [5]. In a German study, 19% of all hospitalized patients with COVID-19 died [4], however many patients die at home, in long-term care facilities or in hospices [6▪]. Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of the World Health Organization stated that: ‘The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of palliative care in all healthcare systems. The need for relief from severe suffering, the difficult decision making, and complicated grief brought on by the pandemic are exactly the types of problems that palliative care was designed to help address.’[2] Therefore, the aims of the present review are: (1) to provide insight in the palliative care needs of patients with COVID-19; (2) to highlight the challenges of COVID-19 for palliative care; (3) to highlight developments in COVID-19 palliative care. For the current review, Pubmed was searched in June 2021 for all studies regarding palliative care in COVID-19.

Box 1.

no caption available

PALLIATIVE CARE NEEDS OF PATIENTS WITH COVID-19

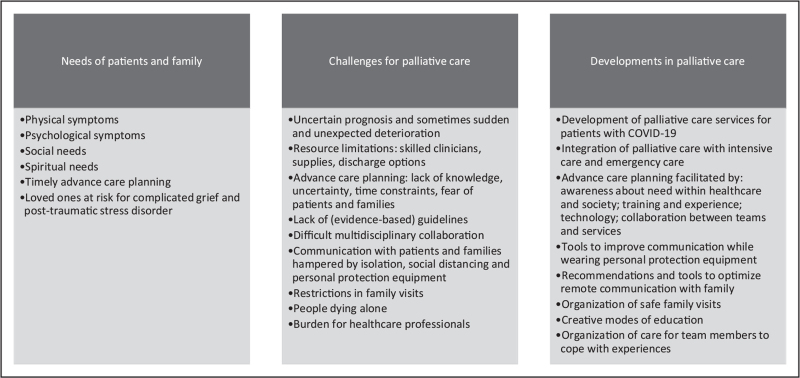

Patients with serious COVID-19 and their families have needs in all domains of palliative care: physical, psychological, social and spiritual (Fig. 1). Indeed, multiple symptoms are present in hospitalized patients dying from COVID-19. Breathlessness is one of the most prevalent symptoms, but other frequently seen symptoms include cough, fever, drowsiness, pain and delirium [7▪▪]. We still have to learn about palliative treatment of symptoms in patients with COVID-19, but current data suggest that regular used palliative drugs such as opioids and midazolam are in most patients effective for soothing symptoms [7▪▪]. Frequently present psychological symptoms include anxiety and agitation [5,7▪▪,8,9▪]. Families are often confronted with significant burden, which they have to face in times of social isolation, sometimes being ill themselves or having more than one ill or even deceased family member. They may suffer from feelings of guilt over the possible transmission of COVID-19 [9▪]. Spiritual needs are present, both among patients and their loved ones. In fact, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in fundamental uncertainty in communities, patients, and families, including existential views of life and death [10]. Previous authors have stated that: ‘spiritual care is not a luxury, it is a necessity for any system that claims to care for people’ [11▪].

FIGURE 1.

COVID-19 palliative care needs, challenges and developments.

The often uncertain prognosis requires timely advance care planning, including discussing goals of care, willingness to undergo life-sustaining treatments and end-of-life wishes [9▪]. Indeed, the ‘COVID-19: guidance on palliative care from a European Respiratory Society (ERS) international task force’ recommended that advance care planning should be routinely done or reviewed by clinicians with patients and their loved ones at diagnosis of serious COVID-19, but also at the discharge of recovered patients. They acknowledged that life-sustaining treatment preferences might have changed after such a life event as a hospital admission because of COVID-19. Moreover, preferences regarding life-sustaining treatments in case of COVID-19 might be different than preferences in other circumstances [12▪].

Family members of deceased patients with COVID-19 are at risk for complicated grief and even posttraumatic stress disorder, for example, because of being unable to prepare for the often unexpected death, multiple losses in one family, insufficient social support because of social isolation and being able to follow traditional grieving rituals [13▪▪,14]. Supporting families before and after the death of a patient can positively influence bereavement outcomes [14].

So, the need for palliative care addressing physical, psychological, social and existential needs in people with serious COVID-19 is paramount. The above mentioned ERS taskforce, therefore, recommended that healthcare professionals trained in palliative care should be available to all patients with ‘serious COVID-19’ (defined as COVID-19 that carries a high risk of mortality, negatively impacts quality of life and daily function, and/or is burdensome in symptom, treatment or caregiver stress) with persistent symptoms and concerns despite optimal disease treatment, irrespective of whether people remain in the hospital or at home [12▪].

PALLIATIVE CARE CHALLENGES

The crisis situation around COVID-19 resulted in many challenges for palliative care (Fig. 1), several of which are discussed below.

First, patients with COVID-19 may deteriorate quickly, which makes it difficult to introduce palliative care in a timely way. Clinicians working in community care often saw patients die within days of becoming ill, especially frail elderly [6▪]. Other patients, even with comorbidities, were living much longer than expected [15]. Triage tools are only able to predict adverse outcomes for individuals with COVID-19 to a limited extent [16].

Second, clinicians are facing resource limitations, including the limited availability of palliative care specialists. Indeed, healthcare resources are under pressure in trying to cope with many acutely ill people. Naturally, the first efforts in this pandemic were focused on critical care. Nevertheless, the need for involving palliative care quickly became clear [17], resulting in high demands on palliative care providers. Indeed, palliative care clinicians reported both stress as well as exhaustion [18]. Home care services were struggling with shortages of resources and supplies, including access to medication and medical equipment [19]. Sometimes discharge options for COVID-19 patients were limited, preventing patients from dying in their preferred place [20]. Although the media mainly paid attention to critical care for patients with COVID-19 [21], the provision of end-of-life care in the community also significantly increased, particularly for older people [6▪]. Community nurses provision of advance care planning, anticipatory prescribing of medication, symptom management, bereavement support, death verification and support to family and carers increased [6▪].

Third, advance care planning and decision-making were further challenged by both the lack of knowledge, and the huge amount of uncertainty, regarding the clinical course and prognosis of COVID-19 as well as time constraints. Because of these time constraints, clinicians found they had to rush their advance care planning conversations [20]. Healthcare providers observed that media coverage increased fear among patients and families that clinical decisions were made in the context of limited resources [20].

Fourth, healthcare professionals reported a lack of guidance in palliative care for patients with COVID-19 [22]. Although first consensus-based recommendations for palliative care have been published, evidence-based recommendations are now needed [12▪,23].

Fifth, multidisciplinary collaboration is a cornerstone of palliative care, but was defied during this pandemic as well. For example, community nursing staff in the UK felt abandoned and vulnerable and found that, whereas their visits to patients had increased, family physicians and specialist palliative care services decreased their home visits [6▪]. Also, bereaved family members sometimes reported the lack of visits by family physicians, whereas other family members greatly appreciated their family physician [24]. Other community clinicians valued working together with specialist palliative care services [6▪].

Sixth, communication with patients and their loved ones is an essential part of palliative care. Indeed, compassionate communication is vital for multidimensional needs assessment and to elicit expectations, goals and values. In COVID-19, because of isolation and social distancing, often remote communication with family members is needed [25]. The lack of in-person communication led to uncertainty about levels of care and distress among family members. Communication was not always clear enough concerning the imminent death: families experienced less time to say goodbye to their loved ones and lacked emotional support for themselves [24]. Remote communication is more challenging for people with low literacy or limited digital literacy skills, and for people with visual or hearing impairment [26]. Some family members even experienced the death of their loved ones as traumatic [24]. In-person communication usually required personal protection equipment, which also challenges interaction [25]. Clinicians felt that they lacked the usual tools for communication, such as being able to read nonverbal cues, use nonverbal communication skills to show empathy and build a trusted relationship before having these difficult conversations [20]. Remote consultations with patients also increased in community end-of-life care and healthcare professionals were frustrated by the limitations they experienced. Some professionals experienced remote consultations as a source of confusion and distress for patients and even reported that these consultations could cause huge emotional trauma to families [6▪].

Seventh, family visits are restricted with some families being advised not to touch or even to be in the same room as their loved one [27]. Bereaved family members reported distress, anxiety, guilt and sadness because of these restrictions [24]. In a qualitative study, palliative care physicians explained that family was allowed to be with an actively dying patient but, as predicting death is so challenging in COVID-19, in several instances family were unable to attend as the patient died before staff had expected [18]. Data from the national Swedish Register of Palliative Care showed that someone was present in 59% of the expected deaths from COVID-19 in hospital or nursing homes, but in only 17% of the patients a relative had been present during dying [28].

Finally, COVID-19 resulted in considerable burden for many healthcare professionals, including in palliative care. Clinicians found witnessing the suffering of families and patients dying alone as one of the hardest things [18]. Also seeing so many patients dying and managing anxiety around infection control negatively influenced the well-being of healthcare professionals. Healthcare professionals became ill themselves or felt being accused of bringing the virus to others [6▪]. Some healthcare professionals chose to isolate themselves from their social support systems to limit the risk of exposure their families or friends to the virus [13▪▪]. Public ignorance of preventive measures was another source of distress [29].

DEVELOPMENTS IN COVID-19 PALLIATIVE CARE

Although facing these challenges, palliative care services worldwide rapidly developed their services and sought opportunities to support patients, their families and healthcare providers (Fig. 1). In Boston, for example, a hospital-based palliative care unit was rapidly developed to support interdisciplinary end-of-life care and support family, whereas allowing other staff members to focus on patients in need of life-sustaining treatments [15]. The paramount need of palliative care also facilitated the integration of palliative care with intensive care and emergency care, and appreciation for palliative care services [18].

The pandemic also facilitated advance care planning [21]. Suddenly, awareness about the need for advance care planning increased within both healthcare and society, facilitating these conversations [18,21]. Palliative care services increased their provision of advance care planning as well as providing advice to others on how to conduct advance care planning [20]. Advance care planning was made part of regular clinical care at referral to palliative care services as well as a standard topic during multidisciplinary meetings. Technology was used to facilitate recording of COVID-19 specific advance care planning discussions [20]. This also showed the need for training clinicians across all specialties in primary palliative care skills, such as communication and advance care planning [18]. For example, family physicians and practice nurses further developed their role in advance care planning. They encouraged their patients to think about advance care planning, provided information that became easier as knowledge concerning COVID-19 increased, and provided advice concerning advance care planning, including in patients they would have not identified before as being in need of advance care planning [21]. Tools are now available to support clinicians with limited experience in palliative care in performing advance care planning conversations, such as the GOOD framework which consists of four steps: Goals (determine goals and values); Options (determine and describe options); Opinions (elicit patient preferences regarding options, communicate clinician perspective and arrive at shared decision); and Documentation (document outcome of decision-making and reasoning behind decisions) [30▪]. Collaboration between teams and services further facilitated advance care planning.

Tools were developed for healthcare professionals to improve communication whilst wearing personal protection equipment, such as flashcards [31]. Teams also found ways to communicate with families in the absence of in person visits, like daily updates after rounds, support calls by social workers or chaplains, and video visits to update family and help the family see the patient [15]. Key elements of remote communication skills have been published and include appropriate set-up and conduct of the meeting (for example, a quiet environment, maintaining eye contact), preparing the participants for this way of communication, avoiding prolonged silence as well as overtalking, responding to emotions and closing the visit [32]. A guide for compassionate phone communication with loved ones was developed to facilitate daily phone updates [33▪▪]. Bereaved family reported how helpful these regular proactive phone calls are [24]. Moreover, they reported that despite all challenges their loved one received compassionate care and died in the right place [24]. Later on, teams developed a protocol to allow safe visits of family members, whereas at the same time providing support to these family members [15]. Teams were creative in offering education in palliative care, such as educational videos, individual education, and bedside mentoring [15].

Guidance has also been offered to clinicians to offer spiritual care. To facilitate clinicians to become a ‘spiritual care generalist’, COVID-19 related questions were added to the FICA tool. The FICA tool consists of four model components (Faith, Importance or Influence, Community, Address), each with related assessment questions to facilitate talking about spiritual needs. It can be used in any setting [11▪].

Finally, recommendations were provided to enhance self-care for healthcare providers, such as: being able to take breaks and disconnect from COVID-19; prepare and inform; adequate supervision and peer support [13▪▪]. Teams were organizing taking care of their team members. They for example arranged scheduling time to reflect and debrief, virtual meditation sessions, or virtual group reflections led by a psychologist [15].

CONCLUSION

Palliative care has an important role in this pandemic and is facing great demands. Palliative care services worldwide have rapidly developed their services in response and found opportunities to support patients, their families and healthcare providers, for example by integration of palliative care with other departments or services, and the developments of tools and education for nonpalliative care clinicians. Increased multidisciplinary collaboration, integrated palliative care and education across all specialties in primary palliative care skills are needed to be able to face future demands of such a pandemic [18]. Finally, intervention studies are needed to enable evidence-based recommendations for providing optimal palliative care in COVID-19.

Acknowledgements

None.

Financial support and sponsorship

None.

Conflicts of interest

D.J.A.J. has received lecture fees from Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim and Chiesi in the previous 3 years.

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

▪ of special interest

▪▪ of outstanding interest

REFERENCES

- 1. COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. [Accessed 17 June 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Worldwide Hospice Palliative Care Alliance (WHPCA) Global Atlas of Palliative Care. 2020. https://www.thewhpca.org/resources/globalatlas-on-end-of-life-care. [Accessed 17 June 2021] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Espana PP, Bilbao A, Garcia-Gutierrez S, et al. Predictors of mortality of COVID-19 in the general population and nursing homes. Intern Emerg Med 2021; 16:1487–1496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gessler N, Gunawardene MA, Wohlmuth P, et al. Clinical outcome, risk assessment, and seasonal variation in hospitalized COVID-19 patients – results from the CORONA Germany study. PLoS One 2021; 16:e0252867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Keeley P, Buchanan D, Carolan C, et al. Symptom burden and clinical profile of COVID-19 deaths: a rapid systematic review and evidence summary. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020; 10:381–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6▪.Mitchell S, Oliver P, Gardiner C, et al. Community end-of-life care during COVID-19: findings of a UK primary care survey. BJGP Open 2021; 5:BJGPO.2021.0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article provides insight in the challengens and opportunities of community palliative care in COVID-19.

- 7▪▪.Lovell N, Maddocks M, Etkind SN, et al. Characteristics, symptom management, and outcomes of 101 patients with COVID-19 referred for hospital palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020; 60:e77–e81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article provides an overview of characteristics of 101 patients with COVID-19 referred to palliative care.

- 8.Sun H, Lee J, Meyer BJ, et al. Characteristics and palliative care needs of COVID-19 patients receiving comfort-directed care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020; 68:1162–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9▪.Bajwah S, Wilcock A, Towers R, et al. Managing the supportive care needs of those affected by COVID-19. Eur Respir J 2020; 55:2000815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review provides an excellent overview of how to manage supportive care needs of patients with COVID-19.

- 10.Etkind SN, Bone AE, Lovell N, et al. The role and response of palliative care and hospice services in epidemics and pandemics: a rapid review to inform practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020; 60:e31–e40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11▪.Ferrell BR, Handzo G, Picchi T, et al. The urgency of spiritual care: COVID-19 and the critical need for whole-person palliation. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020; 60:e7–e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article shows the needs and opportunities for spiritual care in COVID-19.

- 12▪.Janssen DJA, Ekstrom M, Currow DC, et al. COVID-19: guidance on palliative care from a European Respiratory Society international task force. Eur Respir J 2020; 56:2002583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article provides international consensus recommendation for palliative care in COVID-19.

- 13▪▪.Wallace CL, Wladkowski SP, Gibson A, et al. Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: considerations for palliative care providers. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020; 60:e70–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article provides an important overview of grief related to COVID-19.

- 14.Morris SE, Moment A, Thomas JD. Caring for bereaved family members during the COVID-19 pandemic: before and after the death of a patient. J Pain Symptom Manag 2020; 60:e70–e74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drutchas A, Kavanaugh A, Cina K, et al. Innovation in a crisis: lessons learned from the rapid development of an end-of-life palliative care unit during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Palliat Med 2021; 24:1280–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomas B, Goodacre S, Lee E, et al. Prognostic accuracy of emergency department triage tools for adults with suspected COVID-19: the PRIEST observational cohort study. Emerg Med J 2021; 38:587–593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radbruch L, Knaul FM, de Lima L, et al. The key role of palliative care in response to the COVID-19 tsunami of suffering. Lancet 2020; 395:1467–1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rowe JG, Potts M, McGhie R, et al. Palliative Care Practice During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Descriptive Qualitative Study of Palliative Care Clinicians. J Pain Symptom Manag 2021; doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.013. [Online ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ritchie CS, Gallopyn N, Sheehan OC, et al. COVID Challenges and Adaptations Among Home-Based Primary Care Practices: Lessons for an Ongoing Pandemic from a National Survey. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2021; 22:1338–1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradshaw A, Dunleavy L, Walshe C, et al. Understanding and addressing challenges for advance care planning in the COVID-19 pandemic: an analysis of the UK CovPall survey data from specialist palliative care services. Palliat Med 2021; 35:1225–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dujardin J, Schuurmans J, Westerduin D, et al. The COVID-19 pandemic: a tipping point for advance care planning? Experiences of general practitioners. Palliat Med 2021; 35:1238–1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Costantini M, Sleeman KE, Peruselli C, et al. Response and role of palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national telephone survey of hospices in Italy. Palliat Med 2020; 34:889–895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munch U, Muller H, Deffner T, et al. Recommendations for the support of suffering, severely ill, dying or grieving persons in the corona pandemic from a palliative care perspective: Recommendations of the German Society for Palliative Medicine (DGP), the German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive and Emergency Medicine (DIVI), the Federal Association for Grief Counseling (BVT), the Working Group for Psycho-oncology in the German Cancer Society, the German Association for Social Work in the Healthcare System (DVSG) and the German Association for Systemic Therapy, Counseling and Family Therapy (DGSF). Schmerz 2020; 34:303–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mayland CR, Hughes R, Lane S, et al. Are public health measures and individualised care compatible in the face of a pandemic? A national observational study of bereaved relatives’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med 2021; 35:1480–1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fadul N, Elsayem AF, Bruera E. Integration of palliative care into COVID-19 pandemic planning. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2021; 11:40–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sutherland AE, Stickland J, Wee B. Can video consultations replace face-to-face interviews? Palliative medicine and the Covid-19 pandemic: rapid review. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2020; 10:271–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.The Lancet. Palliative care and the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 2020; 395:1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Strang P, Bergstrom J, Martinsson L, et al. Dying from COVID-19: loneliness, end-of-life discussions, and support for patients and their families in nursing homes and hospitals. A National Register Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2020; 60:e2–e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galehdar N, Kamran A, Toulabi T, et al. Exploring nurses’ experiences of psychological distress during care of patients with COVID-19: a qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry 2020; 20:489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30▪.Petriceks AH, Schwartz AW. Goals of care and COVID-19: a good framework for dealing with uncertainty. Palliat Support Care 2020; 18:379–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This article shows the possibility of the GOOD framework in facilitating advance care planning in COVID-19.

- 31. Cardmedic. https://www.cardmedic.com. [Accessed 16 June 2020] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chua IS, Jackson V, Kamdar M. Webside manner during the COVID-19 pandemic: maintaining human connection during virtual visits. J Palliat Med 2020; 23:1507–1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33▪▪.Field-Smith A, Robinson L. Talking to relatives. A guide to compassionate phone communication during COVID-19. https://www.pslhub.org/learn/coronavirus-covid19/tips/talking-to-relatives-guide-to-compassionate-phone-communication-during-covid-19-r2009/. [Accessed 29 June 2021] [Google Scholar]; This is an excellent guide for remote communication with family members.