Abstract

Alcohol use can cause hepatic necroinflammation and worsening portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. We aimed to evaluate the associations between degree of alcohol use and clinical liver‐related outcomes according to etiology of cirrhosis. In this retrospective cohort analysis, 44,349 U.S. veterans with cirrhosis from alcohol‐associated liver disease (ALD), chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection, or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease were identified who completed the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption questionnaire in 2012. Based on this score, level of alcohol use was categorized as none, low level, or unhealthy. Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used to assess for associations between alcohol use and mortality, cirrhosis decompensation (new ascites, encephalopathy, or variceal bleeding), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). At baseline, 36.4% of patients endorsed alcohol use and 17.1% had unhealthy alcohol use. During a mean 4.9 years of follow‐up, 25,806 (57.9%) patients died, 9,409 (21.4%) developed a new decompensation, and 4,733 (11.1%) developed HCC. In patients with ALD‐cirrhosis and HCV‐cirrhosis, unhealthy alcohol use, compared with no alcohol use, was associated with higher risks of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.13, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.07‐1.19 and aHR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.08‐1.20, respectively) and decompensation (aHR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.07‐1.30 and aHR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.00‐1.16, respectively). Alcohol use was not associated with HCC, regardless of cirrhosis etiology. Conclusion: Unhealthy alcohol use was common in patients with cirrhosis and was associated with higher risks of mortality and cirrhosis decompensation in patients with HCV‐cirrhosis and ALD‐cirrhosis. Therefore, health care providers should make every effort to help patients achieve abstinence. The lack of association between alcohol use and HCC merits further investigation.

Abbreviations

- aHR

adjusted hazard ratio

- ALD

alcohol‐associated liver disease

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- AUD

alcohol use disorder

- AUDIT‐C

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption

- CI

confidence interval

- FIB‐4

Fibrosis‐4

- HBV

hepatitis B virus

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HCV

hepatitis C virus

- HIV

human immunodeficiency virus

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- INR

international normalized ratio

- NAFLD

nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- SVR

sustained viral response

- VAHS

Veterans Affairs Healthcare System

Alcohol use in patients with chronic liver disease is common, with approximately 20%‐69% of patients endorsing drinking to various degrees.( 1 , 2 , 3 ) In patients with alcohol‐associated liver disease (ALD), including those with cirrhosis, alcohol use has been shown to contribute to increased rates of hepatic decompensation and mortality.( 1 , 2 , 4 )

In patients with chronic liver disease due to hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcohol has been associated with increased mortality( 5 ) and higher rates of decompensated liver disease.( 6 , 7 ) Furthermore, among patients with HCV, alcohol use is associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).( 8 ) This is likely due to synergistic hepatocellular damage and resulting fibrosis from both alcohol and HCV.( 9 ) In contrast, the literature on alcohol use in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is mixed. Some studies have reported increased risk of hepatic fibrosis,( 10 ) HCC,( 11 ) and mortality.( 12 ) Other studies have found a beneficial effect from moderate alcohol consumption.( 13 , 14 ) Many of these studies included patients with both noncirrhotic liver disease and cirrhosis, making it difficult to assess whether the risk of alcohol use is different among patients with established cirrhosis.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to describe the patterns of alcohol use in a cohort of U.S. veterans with cirrhosis and to evaluate the associations between severity of alcohol use and liver‐related outcomes and mortality, overall and by etiology of cirrhosis. We hypothesized that any alcohol use, and particularly high‐risk alcohol use, would be associated with an increased risk of liver‐related decompensation, HCC, and all‐cause mortality.

Patients and Methods

Study Design

We identified all patients with cirrhosis, without a prior history of liver transplantation, who received care in the national Veterans Affairs Healthcare System (VAHS) in calendar year 2012 and who had Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT‐C) testing performed for screening of alcohol use disorder (AUD) in 2012 or within 1 year before entry in the cohort. We followed these patients retrospectively until February 5, 2020, to assess for the development of death and liver‐related outcomes, including decompensated cirrhosis (i.e., ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or bleeding gastroesophageal varices), HCC, and liver transplantation. We then examined the associations between baseline alcohol use (estimated by AUDIT‐C) and development of these outcomes.

Study Population and Data Source

The VAHS is the largest integrated health care system in the United States and provides health care to more than 8.9 million veterans each year, at 168 VAHS Medical Centers and 1,053 outpatient clinics. Demographic, comorbidities, alcohol use, and clinical outcomes data were extracted from the VAHS’s Corporate Data Warehouse, a data repository derived from the VAHS electronic medical records, developed specifically to facilitate research. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the Veterans Affairs Puget Sound Healthcare System.

We identified 56,760 patients who had a diagnosis of cirrhosis related to HCV, ALD, or NAFLD first recorded at or before December 31, 2012, and who received VAHS health care in calendar year 2012, defined by having at least one inpatient or outpatient visit during that calendar year. We excluded 1,909 patients who had undergone liver transplantation before baseline AUDIT‐C and 10,502 patients who did not have a baseline AUDIT‐C score performed in 2012 or within 1 year of entry into the cohort, leaving 44,349 patients in the current analyses.

Definition of Cirrhosis

Diagnosis of cirrhosis was established based on the report of an associated International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD‐9) code, recorded at least twice in any inpatient or outpatient encounter, or a diagnosis of cirrhosis recorded only once together with at least one complication of cirrhosis. The ICD‐9 codes that we used for cirrhosis and complications of cirrhosis are given in Appendix 1. ICD‐9 codes only (rather than ICD‐10 codes) were used for the baseline diagnosis of cirrhosis in 2012, because ICD‐10 codes were introduced in the VAHS only after October 2015. The diagnosis of cirrhosis using at least two ICD‐9 codes in VAHS data has been shown to have a 97% positive predictive value as compared with chart extraction.( 15 )

Among patients with cirrhosis, the following three mutually exclusive etiologies were defined based on previously published studies( 15 )

HCV: Patients who ever had a positive HCV RNA were categorized as HCV regardless of any additional etiologies. Patients with HCV were subcategorized as “HCV‐cured” if their HCV had been eradicated before entry into the cohort in 2012 or “HCV‐active” if they still had a positive HCV viral load at the time of entry into the cohort. For patients with active HCV at baseline, HCV eradication during follow‐up was accounted for as a time‐varying covariate.

ALD: Patients with ICD‐9 codes for AUD in the absence of serological markers of chronic HCV or hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and in the absence of ICD‐9 codes for hemochromatosis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or autoimmune hepatitis were categorized as ALD.

NAFLD: Patients with ICD‐9 codes for diabetes mellitus, recorded at least twice, or body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 before the diagnosis of cirrhosis, who did not have HCV, ALD as defined previously, or ICD‐9 codes for hemochromatosis, primary biliary cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, or autoimmune hepatitis were categorized as NAFLD. This definition is based on previous work( 11 , 15 ) and reflects the diagnostic process used in clinical practice to diagnose NALFD, as suggested by the risk factors of diabetes mellitus and obesity and exclusion of other etiologies, as NAFLD‐related cirrhosis does not have unique serological, radiological, or histological features. Because the diagnosis of NAFLD was based on the absence of diagnosis of AUD rather than reporting no alcohol use on AUDIT‐C, patients with NAFLD‐cirrhosis could fall into any of the AUDIT‐C categories.

Patients with other etiologies of cirrhosis were not included in the study because they were too heterogeneous.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

We obtained the values of all baseline characteristics as of calendar year 2012 (the year of inception of our cohort). We extracted age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, cirrhosis etiology, laboratory data, and comorbidities including diabetes mellitus, nonalcohol substance use disorder, depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Medical and psychiatric comorbidities were included if reported at least twice before diagnosis of cirrhosis, based on ICD‐9 codes.

Assessment of Alcohol Use at Baseline and During Follow‐up

Alcohol use was assessed using the AUDIT‐C questionnaire, which is a validated screening tool for identifying unhealthy alcohol use (Appendix 2).( 16 ) Scores range from 0‐12, with 0 indicating nondrinking and higher scores reflecting greater amounts of alcohol consumption. The VAHS has been aiming to perform annual screening for unhealthy alcohol use with AUDIT‐C testing for all patients since 2004.

Baseline alcohol use was defined by the AUDIT‐C score reported in 2012 or within 1 year before entry into the cohort; for patients with multiple AUDIT‐C scores, we recorded the one closest to January 1, 2012. Baseline alcohol use was categorized into nondrinking (score of 0), low‐level drinking (score of 1‐3 in men, 1‐2 in women), and unhealthy drinking (score of ≥4 in men, ≥3 in women).( 17 )

We also extracted the AUDIT‐C scores recorded during follow‐up at least 3 months after inception into the cohort and used them to model AUDIT‐C score as a time‐dependent covariate.

Outcomes

We assessed overall mortality and the development of the following liver‐related outcomes during follow‐up: cirrhosis decompensation, HCC, and liver transplantation. Cirrhosis decompensation was defined by the development of at least one of the following: ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, or bleeding gastroesophageal varices. These outcomes were defined based on ICD‐9 or ICD‐10 codes (Appendix 3) that appeared at least twice starting from 3 months after entry into the cohort in 2012. Patients were retrospectively followed until up to February 5, 2020, for the development of these outcomes.

Statistical Analysis

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression was used to assess for associations between severity of alcohol use (assessed by AUDIT‐C scores) and overall mortality and for each of the liver‐related outcomes listed previously. Patients were censored at time of death, liver transplantation, or last follow‐up visit at the VAHS. We modeled baseline alcohol use using the AUDIT‐C scores recorded in 2012 or within 1 year before inception into the cohort. We also modeled the AUDIT‐C scores recorded during follow‐up as time‐dependent covariates (Appendix 4). Survival analyses were stratified by the VAHS facility at which the baseline AUDIT‐C testing was done.

Analyses were adjusted for the following potential confounders that may be associated with both alcohol consumption and the risk of adverse liver‐related outcomes: history of ascites, history of hepatic encephalopathy, history of variceal bleeding, history of HCC, Charlson Comorbidity Index (Appendix 2), age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, HCV genotype, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, HBV infection, diabetes mellitus, platelet count, serum bilirubin, creatinine, albumin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to alanine aminotransferase (ALT) ratio, international normalized ratio (INR), and hemoglobin. For patients with HCV‐cirrhosis, we adjusted for baseline HCV status (active versus history of sustained viral response [SVR]) and accounted for subsequent eradication of HCV during follow‐up as a time‐varying covariate. Continuous variables were categorized and modeled as dummy categorical variables.

Separate analyses were performed for each of the four outcomes (mortality, cirrhosis decompensation, HCC, and liver transplantation), each with its own censoring. All patients were included in the analysis of mortality and liver transplantation. Patients with a history of HCC (active or previously treated) at inception into the cohort were excluded from the analysis of HCC. Patients with a history of all three cirrhosis decompensations (ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, and bleeding gastroesophageal varices) at inception into the cohort were excluded from the analysis of cirrhosis decompensation. Patients lacking at least one decompensation were included in this analysis and followed for the development of a new decompensation (e.g., a patient with ascites as his or her only decompensation would be followed for the development of hepatic encephalopathy and/or bleeding gastroesophageal varices, either of which would qualify as new cirrhosis decompensation).

Receipt of liver transplantation can be a “competing risk” that prevents the development of other outcomes, especially death. This is particularly important because patients who consume alcohol may be less likely to be eligible for liver transplantation, and therefore more likely to die. To account for this, we additionally performed a competing risks analysis in which liver transplantation was considered a competing risk for death.

Results

Baseline Characteristics of Cohort of Patients With Cirrhosis

The cohort of 44,349 patients with cirrhosis had a mean age of 62.1 years (SD = 8.0) and were predominantly male (97.3%) and non‐Hispanic White (65.6%) (Table 1). The underlying etiology of cirrhosis was HCV infection in 52.6% (most with active HCV), ALD in 32.4%, and NAFLD in 14.9%. Of the patients with active HCV, 42% achieved SVR after their baseline AUDIT‐C.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Our Cohort of Patients With Cirrhosis at the Time of Cohort Inception in 2012, Presented According to AUDIT‐C Score

| Total | No Alcohol Use† | Low‐Level Alcohol Use† | Unhealthy Alcohol Use† | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 44,349 | n = 28,239 (63.7%) | n = 8,539 (19.3%) | n = 7,571 (17.1%) | ||

| Age (mean, SD) | 62.1, 8.0 | 62.6, 8.0 | 62.0, 8.0 | 60.3, 7.9 | <0.001 |

| Male (n, %) | 43,173, 97.3 | 27,430, 97.1 | 8,353, 97.8 | 7,390, 97.6 | <0.001 |

| Race/ethnicity (n, %) | <0.001 | ||||

| White, non‐Hispanic | 29,077, 65.6 | 18,423, 65.2 | 5,434, 63.6 | 5,220, 68.9 | |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 8,045, 18.1 | 5,102, 18.1 | 1,735, 20.3 | 1,208, 16.0 | |

| Hispanic | 3,820, 8.6 | 2,555, 9.0 | 706, 8.3 | 559, 7.4 | |

| Other | 907, 2.0 | 576, 2.0 | 177, 2.1 | 154, 2.0 | |

| Declined/missing | 2,500, 5.6 | 1,583, 5.6 | 487, 5.7 | 430, 5.7 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean, SD) | <0.001 | ||||

| ≤25.1 | 11,003, 24.9 | 6,265, 22.3 | 2,132, 25.1 | 2,606, 34.6 | |

| 25.1 to ≤28.7 | 11,074, 25.1 | 6,989, 24.9 | 2,083, 24.5 | 2,002, 26.6 | |

| 28.7 to ≤33.0 | 11,054, 25.0 | 7,273, 25.9 | 2,119, 24.9 | 1,662, 22.1 | |

| >33.0 | 11,029, 25.0 | 7,595, 27.0 | 2,174, 25.6 | 1,260, 16.7 | |

| Cirrhosis etiology (n, %) | <0.001 | ||||

| ALD | 14,385, 32.4 | 7,491, 26.5 | 2,830, 33.1 | 4,064, 53.7 | |

| HCV | 23,324, 52.6 | 17,156, 64.9 | 4,734, 59.3 | 3,465, 48.6 | |

| HCV‐active ‡ | 21,329, 48.1 | 15,654, 55.4 | 4,388, 51.4 | 3,300, 43.6 | |

| HCV‐cured ‡ | 2,013, 4.5 | 1,502, 9.5 | 346, 7.9 | 165, 5.0 | |

| NAFLD | 6,622, 14.9 | 5,094, 18.0 | 1,321, 15.5 | 207, 2.7 | |

| MELD (mean, SD) | 10.4, 4.6 | 10.5, 4.5 | 10.1, 4.5 | 10.6, 4.9 | <0.001 |

| FIB‐4 score (mean, SD) | 6.3, 28.7 | 6.0, 25.7 | 5.9, 25.8 | 7.8, 40.2 | <0.001 |

| FIB‐4 score (median, IQR) | 3.6 (2.0,6.6) | 3.6 (2.0,6.4) | 3.4 (1.9,6.3) | 4.2 (2.3,7.8) | <0.001 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (n, %) | <0.001 | ||||

| 0 | 6,838, 15.4 | 3,311, 11.7 | 1,498, 17.5 | 2,029, 26.8 | |

| 1 | 10,388, 23.4 | 6,313, 22.4 | 2,113, 24.7 | 1,962, 25.9 | |

| 2 | 7,253, 16.4 | 4,628, 16.4 | 1,476, 17.3 | 1,149, 15.2 | |

| >2 | 19,870, 44.8 | 13,987, 49.5 | 3,452, 40.4 | 2,431, 32.1 | |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (n, %) | 11,047, 24.9 | 7,662, 27.1 | 1,744, 20.4 | 1,641, 21.7 | <0.001 |

| Ascites | 7,349, 16.6 | 5,067, 17.9 | 1,194, 14.0 | 1,088, 14.4 | <0.001 |

| Encephalopathy | 3,681, 8.3 | 2,746, 9.7 | 469, 5.5 | 466, 6.2 | <0.001 |

| Bleeding gastroesophageal varices | 3,319, 7.5 | 2,321, 8.2 | 506, 5.9 | 492, 6.5 | <0.001 |

| HCC (n, %) | 2,274, 5.1 | 1,744, 6.2 | 328, 3.8 | 202, 2.7 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (n, %) | 19,060, 43.0 | 13,478, 47.7 | 3,560, 41.7 | 2,022, 26.7 | <0.001 |

| Depression (n, %) | 21,910, 49.4 | 14,230, 50.4 | 3,930, 46.0 | 3,750, 49.5 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety (n, %) | 13,514, 30.5 | 8,871, 31.4 | 2,320, 27.2 | 2,323, 30.7 | <0.001 |

| PTSD (n, %) | 10,950, 24.7 | 7,180, 25.4 | 1,924, 22.5 | 1,846, 24.4 | <0.001 |

| Nonalcohol substance use disorder (n, %) | 13,824, 31.2 | 8,364, 29.6 | 2,531, 29.6 | 2,929, 38.7 | <0.001 |

| AUDIT‐C score (mean, SD) | 1.6, 2.9 | 0.0, 0.0 | 1.7, 0.8 | 7.2, 2.8 | <0.001 |

Baseline severity of alcohol use defined by AUDIT‐C score recorded within 1 year of entry into the cohort: nondrinking: AUDIT‐C score 0; low‐level drinking: AUDIT‐C score 1‐3 in men, 1‐2 in women; and unhealthy drinking: AUDIT‐C score 4‐12 in men, 3‐12 in women.

Patients were categorized as HCV‐cured if their HCV was eradicated before entry into the cohort in 2012; otherwise they were categorized as HCV‐active if they still had a positive HCV‐RNA viral load.

Abbreviations: IQR, interquartile range; MELD, Model for End‐Stage Liver Disease; and PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

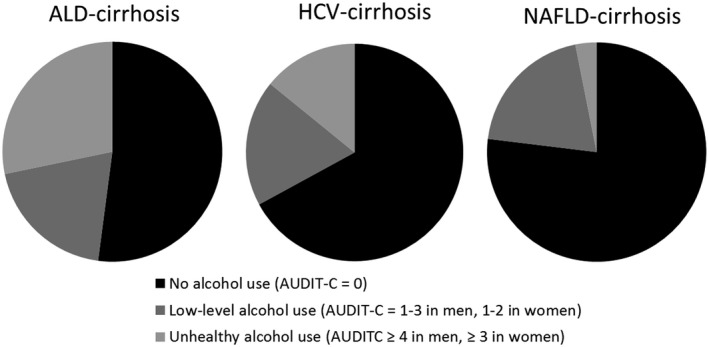

At baseline, 63.7% of all patients did not drink alcohol (AUDIT‐C = 0), 19.3% had low‐level alcohol use (AUDIT‐C = 1‐3 in men, 1‐2 in women), and 17.1% had unhealthy alcohol use (AUDIT‐C ≥ 4 in men, ≥3 in women). Of patients with ALD‐cirrhosis, 47.9% were using alcohol compared to 32.9% with HCV‐cirrhosis and 23.1% with NAFLD‐cirrhosis. Unhealthy alcohol use was also most common in patients with ALD‐cirrhosis (28.0%) and least common in those with NAFLD‐cirrhosis (3.1%) (Fig. 1). Patients with unhealthy alcohol use tended to be younger and non‐Hispanic White and have a lower body mass index, lower rate of diabetes mellitus, lower Charlson Comorbidity Index score, higher Fibrosis‐4 (FIB‐4) score, and higher rate of a nonalcohol substance use disorder than those with no or low‐level alcohol use. Nondrinkers had the highest rate (27.1%) of decompensated cirrhosis, whereas patients with low‐level alcohol use had the lowest rate (21.7%).

FIG. 1.

Proportion of patients with varying degrees of alcohol use as determined by baseline AUDIT‐C scores, at the time of cohort inception in 2012.

Associations Between Baseline Alcohol Use and Adverse Outcomes in Patients With Cirrhosis

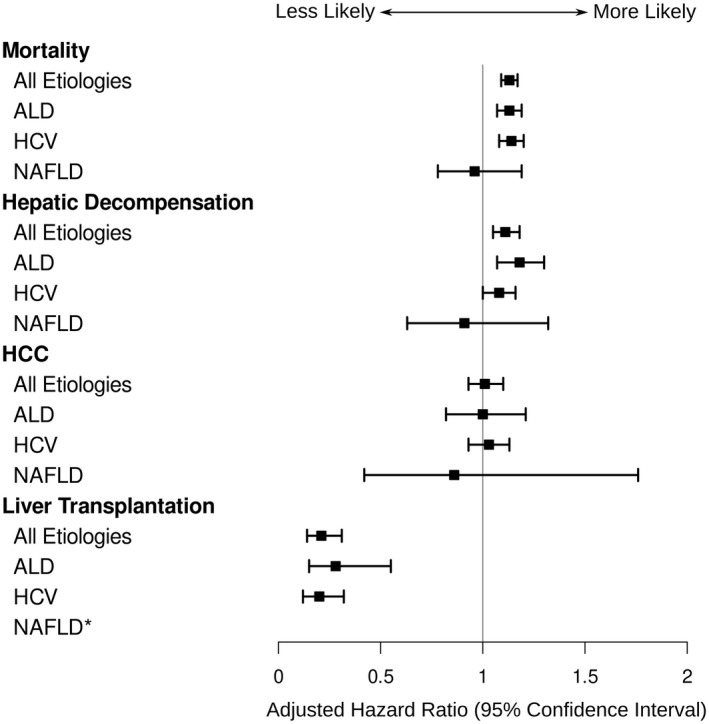

During a mean 4.9 years of follow‐up (range = 1 day to 9.1 years), 25,806 (57.9%) patients died, 9,409 (21.4%) developed cirrhosis decompensation, 4,733 (11.1%) developed HCC, and 683 (1.5%) underwent liver transplantation. Compared with those who reported no alcohol use, unhealthy alcohol use was associated with a higher risk of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 1.13, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.09‐1.17) and decompensation (aHR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.03‐1.16) and lower likelihood of liver transplantation (aHR = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.14‐0.31) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Low‐level alcohol use was also associated with a higher risk of mortality and decompensation and lower likelihood of liver transplantation than no alcohol use, but the magnitudes of these associations were lower than those with unhealthy alcohol use. There was no association between unhealthy or low‐level alcohol use and HCC risk. Results were similar in the competing risks analysis.

TABLE 2.

Association of Baseline and Follow‐up Alcohol Use Modeled as a Time‐Varying Covariate With Mortality and Liver‐Related Outcomes

| Severity of Alcohol Use* | Mortality | New Cirrhosis Decompensation † | HCC | Liver Transplantation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio ‡ | Hazard ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio ‡ | Hazard Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio ‡ | Hazard Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio ‡ | |

| No use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Low‐level use | 0.80 (0.76‐0.83) | 0.89 (0.85‐0.92) | 0.81 (0.75‐0.87) | 0.87 (0.81‐0.94) | 0.86 (0.78‐0.93) | 0.94 (0.86‐1.03) | 0.13 (0.08‐0.20) | 0.12 (0.07‐0.21) |

| Unhealthy use | 1.14 (1.09‐1.18) | 1.18 (1.13‐1.23) | 1.34 (1.25‐1.43) | 1.33 (1.24‐1.43) | 0.82 (0.74‐0.91) | 0.90 (0.81‐1.01) | 0.11 (0.06‐0.19) | 0.10 (0.05‐0.20) |

Baseline severity of alcohol use defined by AUDIT‐C score recorded within 1 year of entry into the cohort: nondrinking: AUDIT‐C score 0; low‐level drinking: AUDIT‐C score 1‐3 in men, 1‐2 in women; and unhealthy drinking: AUDIT‐C score 4‐12 in men, 3‐12 in women.

Defined as new ascites, encephalopathy, or variceal bleeding.

Adjusted for cirrhosis etiology, history of decompensated cirrhosis, history of HCC, history of SVR, SVR (time‐varying), Charlson Comorbidity Index, age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, HIV infection, HBV infection, diabetes mellitus, platelet count, bilirubin, creatinine, albumin, AST/√ALT ratio, INR, and hemoglobin levels.

FIG. 2.

Forest plot of the aHRs of liver‐related outcomes in patients with unhealthy drinking compared with nondrinkers. *There were too few events (patients with NAFLD with unhealthy alcohol use undergoing liver transplantation) to analyze.

Modeling Alcohol Use During Follow‐Up as a Time‐Varying Covariate

When baseline and follow‐up alcohol use was modeled as a time‐varying covariate, unhealthy alcohol was associated with a higher risk of mortality (aHR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.13‐1.23), higher risk of new cirrhosis decompensation (aHR = 1.31, 95% CI = 1.22‐1.41), and lower likelihood of liver transplantation (aHR = 0.10, 95% CI = 0.05‐0.20) compared with nondrinkers (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Association of Baseline Alcohol Use With Mortality and Liver‐Related Outcomes, According to Underlying Etiology of Cirrhosis

| Severity of Alcohol Use§ | Mortality | New Cirrhosis Decompensation† | HCC | Liver Transplantation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡ | Hazard Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡ | Hazard Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡ | Hazard Ratio | Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡ | |

| All patients with cirrhosis | ||||||||

| No use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Low‐level use | 0.97 (0.94‐1.00) | 1.05 (1.02‐1.09) | 1.01 (0.96‐1.07) | 1.05 (1.00‐1.11) | 0.99 (0.92‐1.06) | 1.05 (0.97‐1.13) | 0.38 (0.30‐0.49) | 0.47 (0.36‐0.61) |

| Unhealthy use | 1.17 (1.13‐1.21) | 1.13 (1.09‐1.17) | 1.34 (1.27‐1.41) | 1.11 (1.05‐1.18) | 1.00 (0.93‐1.08) | 1.01 (0.93‐1.10) | 0.22 (0.16‐0.31) | 0.21 (0.14‐0.31) |

| ALD‐cirrhosis | ||||||||

| No use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Low‐level use | 1.07 (1.01‐1.13) | 1.11 (1.05‐1.18) | 1.36 (1.23‐1.50) | 1.24 (1.11‐1.37) | 1.08 (0.89‐1.31) | 1.14 (0.94‐1.40) | 0.50 (0.29‐0.87) | 0.67 (0.37‐1.19) |

| Unhealthy use | 1.16 (1.11‐1.22) | 1.13 (1.07‐1.19) | 1.65 (1.52‐1.80) | 1.18 (1.07‐1.30) | 1.02 (0.86‐1.22) | 1.00 (0.82‐1.21) | 0.34 (0.19‐0.60) | 0.28 (0.15‐0.55) |

| HCV‐cirrhosis | ||||||||

| No use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Low‐level use | 1.01 (0.97‐1.06) | 1.07 (1.02‐1.12) | 0.98 (0.91‐1.05) | 1.00 (0.93‐1.08) | 1.05 (0.96‐1.14) | 1.03 (0.94‐1.12) | 0.36 (0.26‐0.49) | 0.39 (0.28‐0.54) |

| Unhealthy use | 1.24 (1.18‐1.30) | 1.14 (1.08‐1.20) | 1.29 (1.20‐1.39) | 1.08 (1.00‐1.16) | 1.22 (1.11‐1.33) | 1.03 (0.93‐1.13) | 0.22 (0.14‐0.35) | 0.20 (0.12‐0.32) |

| NAFLD‐cirrhosis | ||||||||

| No use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | § | § |

| Low‐level use | 0.69 (0.64‐0.75) | 0.86 (0.79‐0.95) | 0.71 (0.61‐0.82) | 0.93 (0.80‐1.09) | 0.85 (0.65‐1.11) | 1.01 (0.76‐1.34) | § | § |

| Unhealthy use | 0.76 (0.63‐0.92) | 0.96 (0.78‐1.19) | 0.76 (0.54‐1.08) | 0.91 (0.63‐1.32) | 0.66 (0.33‐1.34) | 0.86 (0.42‐1.76) | § | § |

Baseline severity of alcohol use defined by AUDIT‐C score recorded within 1 year of entry into the cohort: nondrinking: AUDIT‐C score 0; low‐level drinking: AUDIT‐C score 1‐3 in men, 1‐2 in women; and unhealthy drinking: AUDIT‐C score 4‐12 in men, 3‐12 in women.

Defined as new ascites, encephalopathy, or variceal bleeding.

Adjusted for cirrhosis etiology, history of decompensated cirrhosis, history of HCC, history of SVR, SVR (time‐varying), Charlson Comorbidity Index, age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, HIV infection, HBV infection, diabetes mellitus, platelet count, bilirubin, creatinine, albumin, AST/ALT ratio, INR, and hemoglobin levels.

There were too few events (patients with NAFLD with unhealthy alcohol use undergoing liver transplantation) to analyze.

Associations Between Baseline Alcohol Use and Adverse Outcomes According to Etiology of Cirrhosis

Among patients with ALD‐cirrhosis, unhealthy drinking, compared with no drinking, was associated with higher risk of mortality (aHR = 1.13, 95% CI = 1.07‐1.20), higher risk of cirrhosis decompensation (aHR = 1.15, 95% CI = 1.05‐1.27), similar risk of HCC (aHR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.83‐1.24), and lower likelihood of liver transplantation (aHR = 0.28, 95% CI = 0.15‐0.54) (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Among patients with HCV‐cirrhosis, unhealthy drinking was associated with higher risk of mortality (aHR = 1.14, 95% CI = 1.09‐1.20), high risk of cirrhosis decompensation (aHR = 1.07, 95% CI = 1.00‐1.15), similar risk of HCC (aHR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.93‐1.13), and lower likelihood of liver transplantation (aHR = 0.20, 95% CI = 0.12‐0.32) compared with nondrinkers. However, among patients with NAFLD‐cirrhosis, the association between unhealthy drinking (vs. no drinking) was not statistically significantly associated with mortality (aHR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.77‐1.18), cirrhosis decompensation (aHR = 0.91, 95% CI = 0.63‐1.32), or HCC (aHR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.42‐1.75).

Discussion

In this cohort of 44,349 patients with cirrhosis, we found that alcohol use, as estimated by the AUDIT‐C questionnaire, was associated with increased risks of mortality and hepatic decompensation in a dose‐dependent manner in patients with ALD‐cirrhosis and HCV‐cirrhosis, but not those with NAFLD‐cirrhosis. The increased risk of decompensation was driven by increased rates of ascites and bleeding gastroesophageal varices but not hepatic encephalopathy. We did not find an association between alcohol use and HCC.

Alcohol Use Is Common in Patients With Cirrhosis

Despite recommendations that patients with cirrhosis abstain from alcohol,( 18 ) our study shows that alcohol use in patients with cirrhosis is common (36.4%) and comparable with other studies.( 1 , 2 , 3 ) Not surprisingly, rates of alcohol use were highest in ALD‐cirrhosis (47.9%), followed by HCV‐cirrhosis (32.9%) and NAFLD‐cirrhosis (23.1%). According to a survey of patients with ALD, many stated that AUD treatment and alcohol abstinence were futile because the liver disease had already occurred.( 3 ) Dedicated efforts should be made to educate patients on the demonstrated health benefits of behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy for AUD in patients with cirrhosis.( 19 )

Association Between Alcohol Use and Mortality or Cirrhosis Decompensation in ALD‐Cirrhosis and HCV‐Cirrhosis

In patients with ALD‐cirrhosis and HCV‐cirrhosis, we found that alcohol use was associated with increased mortality. This is consistent with prior studies and the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines.( 1 , 2 , 4 , 18 ) Many studies in patients with HCV have been limited by the inclusion of mixed populations of those with and without cirrhosis, and in these cohorts, alcohol consumption has been identified as a risk factor for decompensated cirrhosis( 6 , 7 ) and increased mortality.( 5 ) The association between alcohol use and poor outcomes in those with HCV‐cirrhosis may be due to the synergistic effect of HCV and alcohol on the progression of liver fibrosis and hepatocellular damage.( 6 , 20 ) Counseling on the harms of alcohol use and referral for AUD therapy may therefore be particularly important in patients with HCV‐cirrhosis, even after HCV cure.

The highest risks of mortality were demonstrated in patients with unhealthy alcohol use, but importantly, even low‐level use was significantly associated with increased mortality. Furthermore, alcohol use was associated with new decompensation events, specifically ascites and variceal bleeding. These associations may be explained by the effects of alcohol on increasing portal pressure.( 21 ) Overall, our findings suggest that there is no “safe” amount of alcohol that can be recommended to patients with ALD‐cirrhosis and HCV‐cirrhosis.

Association Between Alcohol Use and Mortality or Cirrhosis Decompensation in NAFLD‐Cirrhosis

In patients with NAFLD‐cirrhosis, alcohol use was not associated with decompensation, and low‐level alcohol use was associated with a decreased risk for mortality. The literature has been mixed on whether alcohol use is harmful or protective in patients with NAFLD,( 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ) and most studies have focused on noncirrhotic NAFLD. Our cohort included a small number of patients with a diagnosis of NAFLD and heavy alcohol use, and as patients with NAFLD do not have AUD by definition, this may have contributed to these null results. Additionally, NAFLD is a common disorder that may have been a contributor to the chronic liver disease in patients categorized as HCV‐cirrhosis or ALD‐cirrhosis, and those patients would not have been included in this cohort. The risks of alcohol use in NAFLD‐cirrhosis therefore deserve additional investigation, especially in light of the associated harms of alcohol use seen among our overall cohort of cirrhosis patients.

No Association Between Alcohol and HCC

There was no statistically significant association between alcohol use and increased risk of HCC in patients with cirrhosis. Much of the existing literature has reported that alcohol is a risk factor for the development of HCC; however, many of these studies included patients without cirrhosis or chronic liver disease.( 22 , 23 , 24 ) Therefore, it is unclear whether alcohol use is a risk factor for the development of cirrhosis, which then predisposes to HCC, or if alcohol is a risk factor for HCC itself.

Of the studies specific to patients with cirrhosis, several have reported that alcohol use was not associated with the development of HCC,( 25 , 26 , 27 ) whereas other studies have reported an association with HCC.( 8 , 28 , 29 ) These positive studies did not use standardized alcohol use questionnaires( 8 ) and only assessed alcohol use before, but not after, cirrhosis diagnosis,( 28 , 29 ) which may explain the discrepant results.

Of note, in our time‐varying covariate model, alcohol use was associated with a lower risk for HCC. This pattern has been described in the past and may be explained by the fact that many patients stop drinking during follow‐up when they are diagnosed with liver decompensation or worsening liver function.( 22 )

Strengths and Limitations

This study has a number of strengths, including its large, national cohort, inclusion of multiple etiologies of cirrhosis (ALD, HCV, and NAFLD), adjustment for multiple confounding factors, and prospective ascertainment of screening AUDIT‐C scores during routine clinical practice, which may be less susceptible to underreporting bias. However, this study also had some limitations. First, most patients in the cohort were male, consistent with a U.S. veteran study population, which may limit generalizability. This is particularly relevant given that women are more susceptible to the hepatotoxic effects of alcohol.( 30 ) Second, AUDIT‐C testing is a screening tool that may not precisely reflect safe drinking limits established by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Third, as this is an observational study, there remains the potential for unmeasured confounding, despite multivariable adjustments for a large number of potential confounders. Finally, patients with less common etiologies of cirrhosis, such as chronic hepatitis B infection and cholestatic liver diseases, were not included, so these findings may not generalize to these groups.

In conclusion, in this large retrospective study of U.S. veterans with cirrhosis, we found that alcohol use was common and was associated with increased risks of mortality and decompensation in a dose‐dependent manner in patients with ALD‐cirrhosis and HCV‐cirrhosis, but not those with NAFLD‐cirrhosis. The increased risk of decompensation was driven by increased rates of ascites and bleeding gastroesophageal varices but not hepatic encephalopathy. Given this high burden of alcohol use, clinicians should make every effort to help patients with cirrhosis achieve complete abstinence.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Brian Hulette for his contribution to the creation of Figure 2.

Appendix 1.

ICD‐9 Codes Used for the Definition of Cirrhosis at Baseline Entry Into the Cohort in 2012

Patients were required to have at least two records of ICD‐9 codes for cirrhosis or one record for cirrhosis and at least one for any of the complications of cirrhosis listed in the table (varices no bleeding, varices with bleeding, ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, encephalopathy, hepatorenal syndrome, and hepatopulmonary syndrome).

| Diagnosis | ICD‐9 |

|---|---|

| 1. CIRRHOSIS | |

| Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver | 571.2 |

| Cirrhosis of liver without mention of alcohol | 571.5 |

| 2. VARICES NO BLEEDING | |

| Esophageal varices without mention of bleeding | 456.1 |

| Esophageal varices in diseases classified elsewhere, without mention of bleeding | 456.21 |

| 3. VARICES WITH BLEEDING | |

| Esophageal varices with bleeding | 456.0 |

| Esophageal varices in diseases classified elsewhere, with bleeding | 456.20 |

| 4. ASCITES | |

| Ascites | 789.5 |

| Other ascites | 789.60 |

| Nonmalignant ascites | 789.59 |

| 5. SPONTANEOUS BACTERIAL PERITONITIS | |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 567.23 |

| 6. ENCEPHALOPATHY | |

| Encephalopathy | 572.2 |

| Chronic hepatitis C with hepatic coma | 070.44 |

| 7. HEPATORENAL SYNDROME | |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | 572.5 |

| 8. HEPATOPULMONARY SYNDROME | |

| Hepatopulmonary syndrome | 573.5 |

Appendix 2.

AUDIT‐C Questionnaire and Charlson Comorbidity Index

| AUDIT‐C Questions and Scoring System | Charlson Comorbidity Index Scoring System |

|---|---|

| 1. How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | 1 point |

| a. Never (0) | Age (per decade >40 years) |

| b. Monthly or less (1) | Myocardial infarction |

| c. 2‐4 times a month (2) | Congestive heart failure |

| d. 2‐3 times a week (3) | Peripheral vascular disease |

| e. 4 or more times a week (4) | Cerebrovascular accident or |

| 2. How many standard drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day? | transient ischemic attack |

| a. 1 or 2 (0) | Dementia |

| b. 3 or 4 (1) | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| c. 5 or 6 (2) | Connective tissue disease |

| d. 7 to 9 (3) | Peptic ulcer disease |

| e. 10 or more (4) | Mild liver disease |

| 3. How often do you have six of more drinks on one occasion? | Diabetes mellitus |

| a. Never (0) | 2 points |

| b. Less than monthly (1) | Hemiplegia |

| c. Monthly (2) | Moderate to severe chronic kidney disease |

| d. Weekly (3) | Solid tumor without metastases |

| e. Daily or almost daily (4) | Leukemia |

| Lymphoma | |

| 3 points | |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | |

| 6 points | |

| Solid tumor with metastases | |

| AIDS |

Appendix 3.

ICD‐9 and ICD‐10 Codes Used in the Diagnostic Definitions of HCC, Liver Transplantation, Decompensated Cirrhosis, Diabetes Mellitus, AUD, Hemochromatosis, Primary Biliary Cirrhosis, Autoimmune Hepatitis, and Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis

Patients were required to have at least two records of ICD‐9 or ICD‐10 codes within each outcome.

| Diagnosis | ICD‐9 | ICD‐10 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HCC | |||

| HCC | 155.0 | HCC | C22.0 |

| 2. LIVER TRANSPLANTATION | |||

| Liver replaced by transplant | V42.7 | Liver transplant status | Z49.4 |

| Z48.23 | |||

| Complications of liver transplant | 996.82 | Complications of liver transplant | T86.40 |

| T86.41 | |||

| T86.42 | |||

| T86.43 | |||

| T86.49 | |||

| Procedure Codes | |||

| Liver transplant | 50.51 | Liver transplant | 0FY00Z |

| 50.59 | 47135 | ||

| 47136 | |||

| 3. DECOMPENSATED CIRRHOSIS | |||

| A. VARICES WITH BLEEDING | |||

| Esophageal varices with bleeding | 456.0 | Esophageal varices, with bleeding | I85.01 |

| Esophageal varices in diseases classified elsewhere, with bleeding | 456.20 | Gastric varices, with bleeding | I86.41 |

| B. ASCITES | |||

| Ascites | 789.5 | Alcoholic cirrhosis with ascites | K70.31 |

| Other ascites | 789.60 | Ascites in alcoholic hepatitis | K70.11 |

| Nonmalignant ascites | 789.59 | Ascites in toxic liver disease with chronic active hepatitis | K71.51 |

| Other ascites | R18.8 | ||

| C. ENCEPHALOPATHY | |||

| Encephalopathy | 572.2 | Hepatic failure, unspecified with coma | K72.91 |

| Chronic hepatitis C with hepatic coma | 070.44 | Encephalopathy, unspecified | G93.40 |

| Chronic failure with coma | K72.11 | ||

| 4. DIABETES MELLITUS | |||

| Diabetes | 250.00‐250.92 | ||

| 5. ALCOHOL USE DISORDERS | |||

| Alcohol abuse disorders | 305.0‐305.03 | ||

| Alcohol dependence | 303.9‐303.93 | ||

| Alcohol withdrawal | 291.81 | ||

| Alcohol withdrawal delirium | 291.0 | ||

| Alcohol‐induced persisting amnestic disorder | 291.1 | ||

| Alcohol‐induced persisting dementia | 291.2 | ||

| Dementia associated with alcoholism | 291.2x | ||

| Alcohol‐induced psychotic disorder with hallucinations | 291.3 | ||

| Idiosyncratic alcohol intoxication | 291.4 | ||

| Alcohol‐induced psychotic disorder with delusions | 291.5 | ||

| Other specified alcohol‐induced mental disorders | 291.8 | ||

| Unspecified alcohol‐induced mental disorders | 291.9 | ||

| Acute alcohol intoxication | 303.00‐301.03 | ||

| Pancreatitis secondary to alcohol | 577 | ||

| Alcoholic polyneuropathy | 357 | ||

| Cardiomyopathy secondary to alcohol | 425.5 | ||

| Toxic effect of alcohol | 980.9 | ||

| Non‐dependent alcohol abuse | 305.00 | ||

| Alcoholic fatty liver | 571.0x | ||

| Acute alcoholic hepatitis | 571.1x | ||

| Alcoholic liver damage, unspecified | 571.3x | ||

| Alcoholic cirrhosis of liver | 571.2 | ||

| 6. HEMOCHROMATOSIS | |||

| Hemochromatosis | 275.0 | ||

| 7. PRIMARY BILIARY CIRRHOSIS | |||

| Primary biliary cirrhosis | 571.6 | ||

| 8. AUTOIMMUNE HEPATITIS | |||

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 571.32 | ||

| 9. PRIMARY SCLEROSING CHOLANGITIS | |||

| Cholangitis | 576.1 |

Appendix 4.

Cox Proportional Hazards Model: Association of Baseline and Follow‐up Alcohol Use Modeled as a Time‐Varying Covariate With Mortality and Liver‐Related Outcomes

| Mortality Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡ | New Cirrhosis Decompensation† Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡ | HCC Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡ | Liver Transplantation Adjusted Hazard Ratio‡ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of alcohol use* | ||||

| No use | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Low‐level use | 0.89 (0.85‐0.92) | 0.87 (0.81‐0.94) | 0.94 (0.86‐1.03) | 0.12 (0.07‐0.21) |

| Unhealthy use | 1.18 (1.13‐1.23) | 1.33 (1.24‐1.43) | 0.90 (0.81‐1.01) | 0.10 (0.05‐0.20) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| ≤57 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >57‐62 | 1.21 (1.16‐1.26) | 0.92 (0.86‐0.98) | 1.37 (1.25‐1.49) | 0.97 (0.78‐1.20) |

| >62‐66 | 1.26 (1.21‐1.31) | 0.90 (0.84‐0.97) | 1.50 (1.36‐1.65) | 0.73 (0.57‐0.94) |

| >66 | 1.83 (1.74‐1.91) | 0.79 (0.72‐0.87) | 1.47 (1.30‐1.66) | 0.14 (0.08‐0.24) |

| Male | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.38 (1.24‐1.53) | 1.02 (0.87‐1.20) | 1.58 (1.21‐2.06) | 1.19 (0.67‐2.13) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White, non‐Hispanic | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Black, non‐Hispanic | 0.76 (0.73‐0.80) | 0.69 (0.64‐0.75) | 0.93 (0.85‐1.02) | 0.75 (0.57‐0.98) |

| Hispanic | 0.81 (0.77‐0.86) | 0.92 (0.84‐1.00) | 1.14 (1.02‐1.28) | 0.83 (0.61‐1.13) |

| Other | 1.00 (0.90‐1.11) | 0.94 (0.78‐1.12) | 1.27 (1.02‐1.58) | 0.89 (0.47‐1.67) |

| Declined/missing | 1.04 (0.98‐1.11) | 0.94 (0.83‐1.06) | 0.94 (0.80‐1.11) | 0.76 (0.48‐1.21) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||

| ≤25.1 | 1.23 (1.18‐1.28) | 0.93 (0.86‐1.01) | 1.02 (0.93‐1.13) | 0.60 (0.43‐0.82) |

| 25.1 to ≤28.7 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 28.7 to ≤33.0 | 0.93 (0.89‐0.97) | 0.99 (0.92‐1.06) | 0.91 (0.83‐1.00) | 1.22 (0.96‐1.55) |

| >33.0 | 0.93 (0.89‐0.97) | 1.00 (0.92‐1.07) | 0.90 (0.82‐1.00) | 1.00 (0.77‐1.28) |

| Cirrhosis etiology | ||||

| HCV | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ALD | 0.87 (0.83‐0.90) | 0.91 (0.85‐0.98) | 0.37 (0.33‐0.41) | 0.62 (0.47‐0.82) |

| NAFLD | 0.84 (0.80‐0.89) | 0.95 (0.86‐1.05) | 0.43 (0.37‐0.50) | 1.24 (0.89‐1.73) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1 | 1.01 (0.96‐1.07) | 1.01 (0.92‐1.11) | 1.00 (0.90‐1.12) | 0.78 (0.56‐1.08) |

| 2 | 1.18 (1.11‐1.25) | 0.98 (0.88‐1.09) | 1.10 (0.97‐1.24) | 0.77 (0.53‐1.13) |

| >2 | 1.40 (1.33‐1.47) | 1.21 (1.11‐1.33) | 1.05 (0.94‐1.18) | 0.96 (0.71‐1.32) |

| Decompensated cirrhosis | ||||

| No | 1 | ‐ | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.13 (1.09‐1.17) | ‐‐ | 1.11 (1.02‐1.22) | 1.44 (1.17‐1.78) |

| HCC | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ‐ | 1 |

| Yes | 1.82 (1.71‐1.94) | 1.42 (1.26‐1.60) | ‐ | 4.82 (3.68‐6.31) |

| History of SVR | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.47 (1.33‐1.63) | 1.13 (0.93‐1.36) | 0.88 (0.72‐1.07) | 1.67 (0.92‐3.04) |

| SVR | ||||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| 0.41 (0.39‐0.44) | 0.54 (0.48‐0.60) | 0.76 (0.69‐0.85) | 0.47 (0.34‐0.66) | |

| Diabetes | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.17 (1.13‐1.21) | 1.35 (1.27‐1.44) | 1.17 (1.08‐1.27) | 1.17(0.95‐1.44) |

| HIV co‐infection | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 0.81 (0.71‐0.91) | 0.76 (0.61‐0.95) | 0.60 (0.44‐0.82) | 0.35 (0.11‐1.11) |

| HBV co‐infection | ||||

| No | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Yes | 1.05 (0.98‐1.13) | 0.95 (0.83‐1.09) | 1.09 (0.93‐1.27) | 0.61 (0.36‐1.03) |

| Platelet count (k/µL) | ||||

| >187 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >133‐187 | 1.01 (0.97‐1.06) | 1.51 (1.36‐1.67) | 1.50 (1.32‐1.70) | 1.68 (1.07‐2.64) |

| >89‐133 | 1.10 (1.05‐1.15) | 2.09 (1.90‐2.31) | 1.91 (1.69‐2.17) | 2.09 (1.36‐3.20) |

| ≤89 | 1.22 (1.17‐1.28) | 2.60 (2.35‐2.87) | 2.34 (2.06‐2.66) | 3.19 (2.10‐4.86) |

| Bilirubin (g/dL) | ||||

| ≤0.6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >0.6 to 0.9 | 1.02 (0.98‐1.06) | 1.15 (1.06‐1.25) | 0.98 (0.89‐1.09) | 1.04 (0.72‐1.50) |

| >0.9 to 1.38 | 1.14 (1.08‐1.19) | 1.30 (1.19‐1.42) | 1.20 (1.08‐1.34) | 1.62 (1.14‐2.32) |

| >1.38 | 1.18 (1.12‐1.24) | 1.44 (1.32‐1.57) | 1.07 (0.96‐1.20) | 2.67 (1.90‐3.77) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ||||

| ≤0.79 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >0.79 to 0.9 | 0.89 (0.86‐0.93) | 1.01 (0.94‐1.08) | 1.03 (0.94‐1.12) | 1.29 (1.01‐1.65) |

| >0.9 to 1.1 | 0.90 (0.86‐0.94) | 0.98 (0.91‐1.06) | 0.91 (0.82‐1.00) | 1.34 (1.03‐1.74) |

| >1.1 | 1.12 (1.08‐1.17) | 1.01 (0.93‐1.10) | 0.76 (0.68‐0.85) | 1.59 (1.20‐2.11) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | ||||

| >4.1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >3.7 to 4.1 | 1.22 (1.16‐1.28) | 1.37 (1.24‐1.51) | 1.35 (1.19‐1.52) | 1.37 (0.88‐2.15) |

| >3.2 to 3.7 | 1.68 (1.60‐1.77) | 1.82 (1.65‐2.00) | 1.74 (1.54‐1.96) | 1.95 (1.27‐2.99) |

| ≤3.2 | 2.22 (2.10‐2.34) | 2.22 (2.00‐2.47) | 2.05 (1.79‐2.35) | 2.86 (1.83‐4.46) |

| AST/√ALT ratio | ||||

| ≤5.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >5.5 to 7.42 | 1.14 (1.09‐1.19) | 1.45 (1.32‐1.60) | 1.48 (1.30‐1.69) | 1.65 (1.10‐2.46) |

| >7.42 to 10.42 | 1.30 (1.24‐1.36) | 1.90 (1.72‐2.09) | 2.25 (1.98‐2.56) | 1.83 (1.22‐2.74) |

| >10.42 | 1.47 (1.39‐1.55) | 2.36 (2.13‐2.62) | 2.34 (2.04‐2.68) | 2.32 (1.53‐3.53) |

| INR | ||||

| ≤1.02 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >1.02 to 1.1 | 1.06 (1.02‐1.11) | 1.27 (1.16‐1.39) | 1.27 (1.14‐1.41) | 1.01 (0.68‐1.49) |

| >1.1 to 1.3 | 1.21 (1.16‐1.26) | 1.58 (1.45‐1.72) | 1.34 (1.21‐1.49) | 1.52 (1.06‐2.18) |

| >1.3 | 1.37 (1.30‐1.44) | 1.53 (1.38‐1.69) | 1.20 (1.05‐1.36) | 1.94 (1.33‐2.85) |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||

| ≤12.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| >12.2 to 13.7 | 0.84 (0.81‐0.88) | 0.81 (0.75‐0.87) | 1.01 (0.91‐1.12) | 0.68 (0.53‐0.87) |

| >13.7 to 14.9 | 0.76 (0.73‐0.80) | 0.71 (0.65‐0.77) | 1.11 (1.00‐1.24) | 0.85 (0.65‐1.10) |

| >14.9 | 0.75 (0.71‐0.78) | 0.65 (0.59‐0.71) | 1.23 (1.10‐1.37) | 0.79 (0.59‐1.07) |

*Baseline severity of alcohol use defined by AUDIT‐C score recorded within 1 year of entry into the cohort: nondrinking: AUDIT‐C score 0; low‐level drinking: AUDIT‐C score 1‐3 in men, 1‐2 in women; and unhealthy drinking: AUDIT‐C score 4‐12 in men, 3‐12 in women.

†Defined as new ascites, encephalopathy, or variceal bleeding.

‡Adjusted for cirrhosis etiology, history of decompensated cirrhosis, history of HCC, history of SVR, SVR (time‐varying), Charlson Comorbidity Index, age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, HIV infection, HBV infection, diabetes mellitus, platelet count, bilirubin, creatinine, albumin, AST/√ALT ratio, INR, and hemoglobin levels.

Supported by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (R01CA196692), Center for Integrated Healthcare, and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (I01CX001156 and IIR 17‐120).

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

References

- 1. Lucey MR, Connor JT, Boyer TD, Henderson JM, Rikkers LF. Alcohol consumption by cirrhotic subjects: patterns of use and effects on liver function. Am J Gastroenterol 2008;103:1698‐1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lackner C, Spindelboeck W, Haybaeck J, Douschan P, Rainer F, Terracciano L, et al. Histological parameters and alcohol abstinence determine long‐term prognosis in patients with alcoholic liver disease. J Hepatol 2017;66:610‐618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mellinger JL, Scott Winder G, DeJonckheere M, Fontana RJ, Volk ML, Lok ASF, et al. Misconceptions, preferences and barriers to alcohol use disorder treatment in alcohol‐related cirrhosis. J Subst Abuse Treat 2018;91:20‐27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Goh GB, Chow WC, Wang R, Yuan JM, Koh WP. Coffee, alcohol and other beverages in relation to cirrhosis mortality: the Singapore Chinese Health Study. Hepatology 2014;60:661‐669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zeng QL, Feng GH, Zhang JY, Chen Y, Yang B, Huang HH, et al. Risk factors for liver‐related mortality in chronic hepatitis C patients: a deceased case‐living control study. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:5519‐5526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hutchinson SJ, Bird SM, Goldberg DJ. Influence of alcohol on the progression of hepatitis C virus infection: a meta‐analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2005;3:1150‐1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alavi M, Janjua NZ, Chong M, Grebely J, Aspinall EJ, Innes H, et al. The contribution of alcohol use disorder to decompensated cirrhosis among people with hepatitis C: an international study. J Hepatol 2018;68:393‐401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vandenbulcke H, Moreno C, Colle I, Knebel J‐F, Francque S, Sersté T, et al. Alcohol intake increases the risk of HCC in hepatitis C virus‐related compensated cirrhosis: a prospective study. J Hepatol 2016;65:543‐551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Singal AK, Anand BS. Mechanisms of synergy between alcohol and hepatitis C virus. J Clin Gastroenterol 2007;41:761‐772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chang Y, Cho YK, Kim Y, Sung E, Ahn J, Jung H‐S, et al. Nonheavy drinking and worsening of noninvasive fibrosis markers in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a cohort study. Hepatology 2019;69:64‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ascha MS, Hanouneh IA, Lopez R, Tamimi TA, Feldstein AF, Zein NN. The incidence and risk factors of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology 2010;51:1972‐1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Ong J, Yilmaz Y, Duseja A, Eguchi Y, et al. Effects of alcohol consumption and metabolic syndrome on mortality in patients with nonalcoholic and alcohol‐related fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;17:1625‐1633.e1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dunn W, Sanyal AJ, Brunt EM, Unalp‐Arida A, Donohue M, McCullough AJ, et al. Modest alcohol consumption is associated with decreased prevalence of steatohepatitis in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). J Hepatol 2012;57:384‐391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Mitchell T, Jeffrey GP, de Boer B, MacQuillan G, Garas G, Ching H, et al. Type and pattern of alcohol consumption is associated with liver fibrosis in patients with non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2018;113:1484‐1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ioannou GN, Green P, Lowy E, Mun EJ, Berry K. Differences in hepatocellular carcinoma risk, predictors and trends over time according to etiology of cirrhosis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0204412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT‐C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1789‐1795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Tsui JI, Williams EC, Green PK, Berry K, Su F, Ioannou GN. Alcohol use and hepatitis C virus treatment outcomes among patients receiving direct antiviral agents. Drug Alcohol Depend 2016;169:101‐109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Crabb DW, Im GY, Szabo G, Mellinger JL, Lucey MR. Diagnosis and treatment of alcohol‐associated liver diseases: 2019 Practice Guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2020;71:306‐333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rogal S, Youk A, Zhang H, Gellad WF, Fine MJ, Good CB, et al. Impact of alcohol use disorder treatment on clinical outcomes among patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2020;71:2080‐2092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Serfaty L, Poujol‐Robert A, Carbonell N, Chazouilleres O, Poupon RE, Poupon R. Effect of the interaction between steatosis and alcohol intake on liver fibrosis progression in chronic hepatitis C. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1807‐1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Luca A, Garcia‐Pagan JC, Bosch J, Feu F, Caballeria J, Groszmann RJ, et al. Effects of ethanol consumption on hepatic hemodynamics in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 1997;112:1284‐1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Donato F, Tagger A, Gelatti U, Parrinello G, Boffetta P, Albertini A, et al. Alcohol and hepatocellular carcinoma: the effect of lifetime intake and hepatitis virus infections in men and women. Am J Epidemiol 2002;155:323‐331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aizawa Y, Shibamoto Y, Takagi I, Zeniya M, Toda G. Analysis of factors affecting the appearance of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic hepatitis C. A long term follow‐up study after histologic diagnosis. Cancer 2000;89:53‐59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hassan MM, Hwang L‐Y, Hatten CJ, Swaim M, Li D, Abbruzzese JL, et al. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma: synergism of alcohol with viral hepatitis and diabetes mellitus. Hepatology 2002;36:1206‐1213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Velazquez RF, Rodriguez M, Navascues CA, Linares A, Pérez R, Sotorríos NG, et al. Prospective analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology 2003;37:520‐527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Di Costanzo GG, De Luca M, Tritto G, Lampasi F, Addario L, Lanza AG, et al. Effect of alcohol, cigarette smoking, and diabetes on occurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with transfusion‐acquired hepatitis C virus infection who develop cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;20:674‐679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Adami H‐O, Hsing AW, McLaughlin JK, Trichopoulos D, Hacker D, Ekbom A, et al. Alcoholism and liver cirrhosis in the etiology of primary liver cancer. Int J Cancer 1992;51:898‐902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ikeda K, Saitoh S, Koida I, Arase Y, Tsubota A, Chayama K, et al. A multivariate analysis of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinogenesis: a prospective observation of 795 patients with viral and alcoholic cirrhosis. Hepatology 1993;18:47‐53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ganne‐Carrié N, Layese R, Bourcier V, Cagnot C, Marcellin P, Guyader D, et al. Nomogram for individualized prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence in hepatitis C virus cirrhosis (ANRS CO12 CirVir). Hepatology 2016;64:1136‐1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Becker U, Deis A, Sorensen TI, Gronbaek M, Borch‐Johnsen K, Muller CF, et al. Prediction of risk of liver disease by alcohol intake, sex, and age: a prospective population study. Hepatology 1996;23:1025‐1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]