Abstract

Background:

There is limited information about thymosin α1 (Tα1) as adjuvant immunomodulatory therapy, either used alone or combined with other treatments, in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). This study aimed to evaluate the effect of adjuvant Tα1 treatment on long-term survival in margin-free (R0)-resected stage IA–IIIA NSCLC patients.

Methods:

A total of 5746 patients with pathologic stage IA-IIIA NSCLC who underwent R0 resection were included. The patients were divided into the Tα1 group and the control group according to whether they received Tα1 or not. A propensity score matching (PSM) analysis was performed to reduce bias, resulting in 1027 pairs of patients.

Results:

After PSM, the baseline clinicopathological characteristics were similar between the two groups. The 5-year disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) rates were significantly higher in the Tα1 group compared with the control group. The multivariable analysis showed that Tα1 treatment was independently associated with an improved prognosis. A longer duration of Tα1 treatment was associated with improved OS and DFS. The subgroup analyses showed that Tα1 therapy could improve the DFS and/or OS in all subgroups of age, sex, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI), smoking status, and pathological tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage, especially for patients with non-squamous cell NSCLC and without targeted therapy.

Conclusion:

Tα1 as adjuvant immunomodulatory therapy can significantly improve DFS and OS in patients with NSCLC after R0 resection, except for patients with squamous cell carcinoma and those receiving targeted therapy. The duration of Tα1 treatment is recommended to be >24 months.

Keywords: Non-small cell lung cancer, Resection, Adjuvant therapy, Thymosin α1

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths for men and women globally.[1] Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is the most common type of lung cancer, accounting for approximately 85% of the cases.[2] The selection of the therapeutic options for NSCLC is based on the tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) classification system. Complete surgical resection is the most effective treatment for patients with stage I and II disease and resectable stage IIIA disease.[3] Postoperative recurrence is the most important issue affecting patient survival. Although adjuvant therapy (such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapy) has been improved in the last decades, overall survival (OS) remains poor. The frequency of postoperative recurrence increases with tumor stage, ranging from 15% in stage IA to 60% in stage IIIA,[3] resulting in a decrease in the expected 5-year survival rate after surgery from 90% to 41%.[4] Therefore, exploring effective adjuvant treatments is important to reduce the recurrence risk and improve prognosis.

The treatment of cancer is entering the era of immunotherapy. This therapy can assist the immune system in attacking and eradicating the cancer cells by enhancing the antitumor immune response and reversing the immune tolerance toward the tumor. Cancer immunotherapy can be broadly classified into two general categories: active and passive.[5] The active approach includes the induction of a tumor-directed immune response through vaccination with tumor-associated antigens.[6] The passive immunotherapies include non-specific immunostimulation, monoclonal antibodies, and immune checkpoint inhibitors, as well as adoptive cell transfer approaches using tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes or genetically engineered T cells.[6]

Immunomodulatory therapy, as a type of non-specific immune stimulation, has been widely used as adjuvant therapy and can improve the long-term outcomes of cancer patients.[7–10] Thymosin α1 (Tα1) is one of the commonly used immunomodulators and consists of an N-terminal acetylated acidic peptide containing 28 amino acids with a molecular weight of 3108 Da.[11] Tα1 treatment combined with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy for non-surgical NSCLC patients is associated with improved immune parameters and prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) and OS.[10,12–14] Still, whether Tα1 can improve the long-term prognosis of NSCLC patients who underwent complete surgical resection has not been confirmed. The present study aimed to evaluate the impact of Tα1 as an adjuvant immunomodulatory therapy on the long-term survival of patients with NSCLC who underwent complete surgical resection.

Methods

Ethical approval

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the West China Hospital, Sichuan University (No. 2020-344). Informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board because of the retrospective nature of the study.

Patients

Consecutive patients who underwent surgery for primary NSCLC between May 2005 and December 2018 were identified from the Western China Lung Cancer Database (WCLCD), West China Hospital, Sichuan University. The data did not contain any identifiable patient information. The patients were staged according to the seventh edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) TNM staging system for lung cancer.

The exclusion criteria were pathological stage 0 (ie, carcinoma in situ), IIIB, or IV disease, positive surgical margin (R1 or R2), lack of staging data, previous history of malignancy, lack of data on postoperative immunomodulator use, adjuvant therapy using other synthetic thymic peptides (eg, thymosin or thymopentin), or death within 90 days after surgery regardless of causes.

The patients were grouped into the Tα1 group or the control group according to whether Tα1 was used or not after surgery.

Data collection

The durations of all prescriptions were calculated to determine the duration of Tα1 administration. Clinicopathological data were collected, including the year of surgery, age at surgery (dichotomized according to the median age of 59 years), sex, body mass index (BMI), history of comorbidity according to the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI),[15] smoking status, surgical approach, type of surgery, histological subtypes, pathological TNM stage, neoadjuvant therapy, adjuvant therapy, and follow-up information.

Follow-up

All patients were followed according to the established institutional standards, that is, every 3 to 6 months during the first 5 years after surgery and annually after that. Chest and upper abdominal computed tomography (CT) and brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or CT were performed at every follow-up. Whole-body bone scintigraphy was performed annually. A telephone follow-up was conducted for patients from distant geographical locations and followed at a local hospital. OS was calculated as the time from surgery until death from any cause or last follow-up. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as the period from the surgery date until any local or distant recurrence or death or last follow-up. Survival and postoperative therapy data were recorded in the WCLCD at West China Hospital, Sichuan University.

Statistics analysis

The baseline characteristics are presented as counts and proportions. Pearson's chi-squared test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare the frequencies of the categorical measures. In order to minimize the selection bias between the two groups, propensity score matching (PSM) was performed using R (version 3.5.2, R Core Team, 2018) and the MatchIt package (Daniel Ho, 2018). The logistic regression model was used as the link model. For regression adjustment to be trustworthy, the standardized mean differences of all the included confounding variables were requested within the recommended limits of −0.25 and 0.25.[16] The following statistically different confounding variables were included: year of surgery, sex, CCI, smoking status, surgical approach, type of surgery, histologic subtypes, pathological TNM stage, neoadjuvant therapy, and adjuvant therapy. At last, the patients were matched 1:1, without replacement, using a nearest neighbor approach without a preset caliper width. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to generate the OS and DFS curves before and after PSM. The differences between the curves were analyzed using the log-rank test. Univariable and multivariable analyses for OS and DFS were carried out using the Cox proportional hazard regression model before and after PSM. Subgroup analyses of OS and DFS were also performed by the Cox proportional hazard regression model after PSM. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. All comparisons were two tailed. Statistical tests were performed using SAS for Windows (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R (version 3.5.2, R Core Team, 2018).

Results

Characteristics of the patients

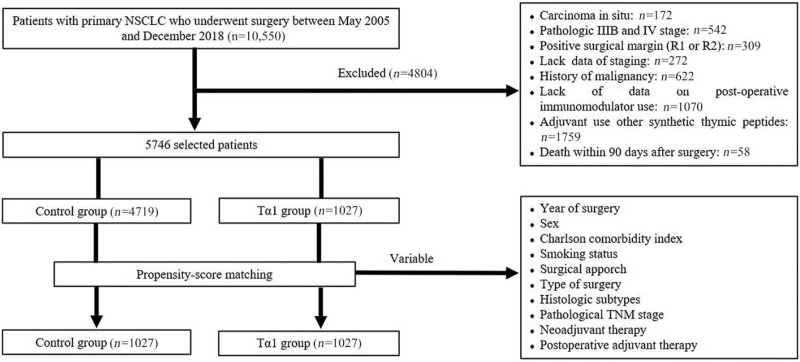

A total of 5746 patients were included (1027 in the Tα1 group and 4719 in the control group) [Figure 1]. Among all patients (n = 5746), 2878 (50.1%) were ≥59 years of age and 3151 (54.8%) were male. In the Tα1 group (n = 1027), 513 (50.0%) were ≥59 years of age and 456 (44.4%) were male; those numbers were 50.1% (2365/4719) and 57.1% (2695/4719), respectively, in the control group. All patients in the Tα1 group started Tα1 medication from 1 month to 3 months after surgery. The dosage was 1.6 mg subcutaneously twice a week, with the doses separated by 3 to 4 days. The control group was free from any immunomodulators after surgery. In the Tα1 group, most operations were performed during the late period of the study (2012–2018) (χ2 = 48.907, P < 0.0001). The female-to-male ratio was higher in the Tα1 group (χ2 = 55.002, P < 0.0001). There were more patients with higher CCI scores (3 and 4–8) (χ2 = 31.749, P < 0.0001) but fewer smokers in the Tα1 group (χ2 = 59.925, P < 0.0001). Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) was more frequently performed in the Tα1 group (χ2 = 75.341, P < 0.0001), as well as sublobectomy (χ2 = 18.921, P < 0.0001). There were more patients with adenocarcinoma in the Tα1 group (χ2 = 62.459, P < 0.0001). The proportion of patients with an earlier pathological stage (IA and IB) was higher in the Tα1 group compared with the control group (χ2 = 104.796, P < 0.0001). More patients received neoadjuvant therapy in the control group (χ2 = 4.285, P = 0.0385). In the Tα1 group, 692 of 1027 patients were postoperatively treated with Tα1 alone, 164 with Tα1 combined with chemotherapy, 58 combined with targeted therapy, 51 combined with chemoradiotherapy, 27 combined with chemotherapy plus targeted therapy, and 35 combined with chemoradiotherapy plus targeted therapy. Among the 4719 patients in the control group, 3297, 1207, 290, 534, 186, and 232 patients received no treatment, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, chemoradiotherapy, chemotherapy plus targeted therapy, and chemoradiotherapy plus targeted therapy after surgery, respectively. No patients in either group received immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Figure 1.

Flowchart diagram of patient selection. NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer; Tα1: Thymosin α1.

After PSM, 1027 pairs of patients were obtained, and there were no significant differences in all variables mentioned above. The clinical characteristics of the two groups, both before and after PSM, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics in the overall study population.

| Overall cohort | Matched cohort | |||||||||

| Variables | Overall | Control group | Tα1 group | χ 2 | P value | Overall | Control group | Tα1 group | χ 2 | P value |

| (N = 5746) | (N = 4719) | (N = 1027) | (N = 2054) | (N = 1027) | (N = 1027) | |||||

| Year of surgery | 48.907 | <0.0001 | – | >0.9999 | ||||||

| 2005–2011 | 1135 (19.8) | 1013 (21.5) | 122 (11.9) | 244 (11.9) | 122 (11.9) | 122 (11.9) | ||||

| 2012–2018 | 4611 (80.2) | 3706 (78.5) | 905 (88.1) | 1810 (88.1) | 905 (88.1) | 905 (88.1) | ||||

| Age (years) | 0.009 | 0.9235 | 0.049 | 0.8254 | ||||||

| <59 | 2868 (49.9) | 2354 (49.9) | 514 (50.0) | 1023 (49.8) | 509 (49.6) | 514 (50.1) | ||||

| ≥59 | 2878 (50.1) | 2365 (50.1) | 513 (50.0) | 1031 (50.2) | 518 (50.4) | 513 (49.9) | ||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 2.566 | 0.2772 | 0.305 | 0.8584 | ||||||

| <24 | 3762 (65.5) | 3072 (65.1) | 690 (67.2) | 1385 (67.4) | 695 (67.7) | 690 (67.2) | ||||

| 24 to <28 | 1678 (29.2) | 1387 (29.4) | 291 (28.3) | 582 (28.3) | 291 (28.3) | 291 (28.3) | ||||

| ≥28 | 306 (5.3) | 260 (5.5) | 46 (4.5) | 87 (4.3) | 41 (4.0) | 46 (4.5) | ||||

| Sex | 55.002 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.9646 | ||||||

| Female | 2595 (45.2) | 2024 (42.9) | 571 (55.6) | 1141 (55.6) | 570 (55.5) | 571 (55.6) | ||||

| Male | 3151 (54.8) | 2695 (57.1) | 456 (44.4) | 913 (44.4) | 457 (44.5) | 456 (44.4) | ||||

| CCI | 31.749 | <0.0001 | 1.045 | 0.9029 | ||||||

| 0 | 1575 (27.4) | 1336 (28.3) | 239 (23.3) | 484 (23.6) | 245 (23.8) | 239 (23.3) | ||||

| 1 | 1439 (25.0) | 1188 (25.2) | 251 (24.4) | 494 (24.0) | 243 (23.7) | 251 (24.4) | ||||

| 2 | 1413 (24.6) | 1166 (24.7) | 247 (24.1) | 480 (23.4) | 233 (22.7) | 247 (24.1) | ||||

| 3 | 808 (14.1) | 650 (13.8) | 158 (15.4) | 324 (15.8) | 166 (16.2) | 158 (15.4) | ||||

| 4–8 | 511 (8.9) | 379 (8.0) | 132 (12.8) | 272 (13.2) | 140 (13.6) | 132 (12.8) | ||||

| Smoking status | 59.925 | <0.0001 | 0.109 | 0.7415 | ||||||

| Current/former | 2469 (43.0) | 2139 (45.3) | 330 (32.1) | 667 (32.5) | 337 (32.8) | 330 (32.1) | ||||

| Never | 3277 (57.0) | 2580 (54.7) | 697 (67.9) | 1387 (67.5) | 690 (67.2) | 697 (67.9) | ||||

| Surgical approach | 75.341 | <0.0001 | 0.129 | 0.7198 | ||||||

| VATS | 4165 (72.5) | 3308 (70.1) | 857 (83.5) | 1720 (83.7) | 863 (84.0) | 857 (83.4) | ||||

| Thoracotomy | 1581 (27.5) | 1411 (29.9) | 170 (16.5) | 334 (16.3) | 164 (16.0) | 170 (16.6) | ||||

| Type of surgery | 18.921 | <0.0001 | 0.338 | 0.8446 | ||||||

| Sublobectomy | 1018 (17.7) | 794 (16.8) | 224 (21.8) | 438 (21.3) | 214 (20.8) | 224 (21.8) | ||||

| Pneumonectomy | 93 (1.6) | 85 (1.8) | 8 (0.8) | 17 (0.8) | 9 (0.9) | 8 (0.8) | ||||

| Lobectomy | 4635 (80.7) | 3840 (81.4) | 795 (77.4) | 1599 (77.9) | 804 (78.3) | 795 (77.4) | ||||

| Histologic subtypes | 62.459 | <0.0001 | 0.789 | 0.6739 | ||||||

| Adenocarcinoma | 4177 (72.7) | 3329 (70.5) | 848 (82.6) | 1710 (83.3) | 862 (83.9) | 848 (82.6) | ||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1114 (19.4) | 980 (20.8) | 134 (13.0) | 260 (12.6) | 126 (12.3) | 134 (13.1) | ||||

| Others | 455 (7.9) | 410 (8.7) | 45 (4.4) | 84 (4.1) | 39 (3.8) | 45 (4.3) | ||||

| Pathological TNM stage | 104.796 | <0.0001 | 4.839 | 0.3043 | ||||||

| IA | 1846 (32.1) | 1443 (30.6) | 403 (39.2) | 796 (38.8) | 393 (38.2) | 403 (39.3) | ||||

| IB | 2028 (35.3) | 1601 (33.9) | 427 (41.6) | 847 (41.2) | 420 (40.9) | 427 (41.6) | ||||

| IIA | 589 (10.3) | 516 (10.9) | 73 (7.1) | 153 (7.5) | 80 (7.8) | 73 (7.1) | ||||

| IIB | 236 (4.1) | 211 (4.5) | 25 (2.4) | 40 (1.9) | 15 (1.5) | 25 (2.4) | ||||

| IIIA | 1047 (18.2) | 948 (20.1) | 99 (9.6) | 218 (10.6) | 119 (11.6) | 99 (9.6) | ||||

| Neoadjuvant therapy | 4.285 | 0.0385 | – | >0.9999 | ||||||

| Yes | 63 (1.1) | 58 (1.2) | 5 (0.5) | 10 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | 5 (0.5) | ||||

| No | 5683 (98.9) | 4661 (98.8) | 1022 (99.5) | 2044 (99.5) | 1022 (99.5) | 1022 (99.5) | ||||

| Postoperative therapy | 65.654 | <0.0001 | 1.376 | 0.9269 | ||||||

| None | 3297 (57.4) | 2605 (55.2) | 692 (67.3) | 1380 (67.2) | 688 (67.0) | 692 (67.4) | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 1207 (21.0) | 1043 (22.1) | 164 (16.0) | 329 (16.0) | 165 (16.1) | 164 (16.0) | ||||

| Targeted therapy | 290 (5.1) | 232 (4.9) | 58 (5.7) | 113 (5.5) | 55 (5.4) | 58 (5.6) | ||||

| Chemoradiotherapy | 534 (9.3) | 483 (10.2) | 51 (5.0) | 113 (5.5) | 62 (6.0) | 51 (5.0) | ||||

| Chemotherapy plus targeted therapy | 186 (3.2) | 159 (3.4) | 27 (2.6) | 52 (2.5) | 25 (2.4) | 27 (2.6) | ||||

| Chemoradiotherapy plus targeted therapy | 232 (4.0) | 197 (4.2) | 35 (3.4) | 67 (3.3) | 32 (3.1) | 35 (3.4) | ||||

Data are shown as n (%). BMI: Body mass index; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; Tα1: Thymosin α1; TNM: Tumor-Node-Metastasis; VATS: Video-assisted thoracic surgery.

Survival outcomes

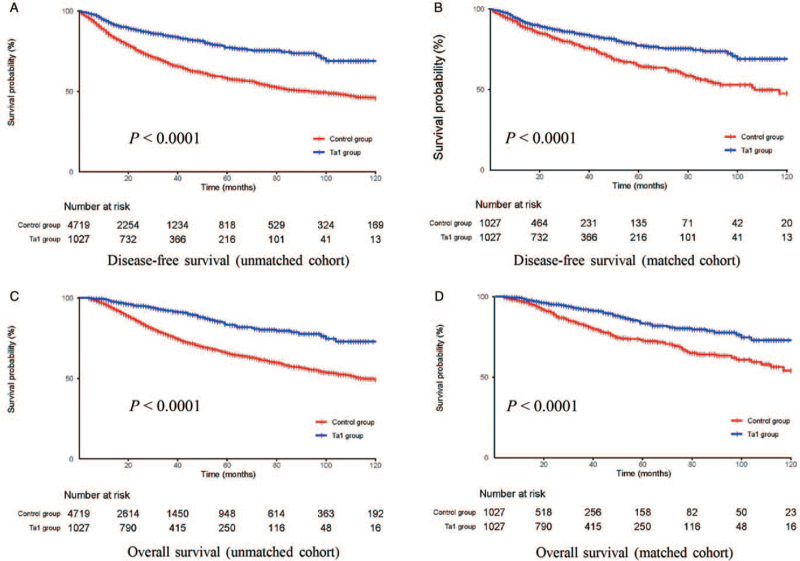

By December 2019, the median follow-up was 25 (range, 4–160) months for the unmatched patients and 26 (range, 4–159) months for the matched patients. Before PSM, there were 10 (1.0%) and 67 patients (1.4%) lost to follow-up in the Tα1 and control groups, respectively. After PSM, 10 (1.0%) and 9 patients (0.9%) in the Tα1 and control groups were lost to follow-up, respectively. Both before and after PSM, the 5-year DFS was higher in the Tα1 group than in the control group (before matching: 77.3% vs. 57.9%, P < 0.0001; after matching: 77.3% vs. 64.7%, P < 0.0001). Similar differences were also observed for OS (before matching: 83.3% vs. 65.6%, P < 0.0001; after matching: 83.3% vs. 72.7%, P < 0.0001) [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curves for DFS (A,B) and OS (C,D) of patients between the Tα1 group and control group in the unmatched and matched cohort. DFS: Disease-free survival; OS: Overall survival; Tα1: Thymosin α1.

The univariable and multivariable analyses for DFS and OS before PSM are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The results after PSM are shown in Tables 2 and 3. In the univariable analyses, adjuvant treatment with Tα1, the later surgery period (2012–2018), age < 59 years, female sex, CCI scores of 0, no smoking history, adenocarcinoma, and early pathologic stage were associated with better DFS and OS. In the multivariable analyses, adjuvant treatment with Tα1 (DFS: hazard ratio [HR], 0.655; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.533–0.805; P < 0.0001; OS: HR, 0.548; 95% CI, 0.426–0.705; P < 0.0001) and early pathologic stage (all stages, P < 0.0001 vs. IA for DFS and OS) were independently associated with better DFS and OS while non-adenocarcinoma and non-squamous cell carcinoma subtypes (DFS: HR, 1.706; 95% CI, 1.188–2.449; P = 0.0038; OS: HR, 2.019; 95% CI, 1.333–3.058; P = 0.0009), were independently associated with worse DFS and OS [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression for DFS after PSM.

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable model | |||||

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Adjuvant Tα1 treatment (yes vs. no) | 0.618 | 0.505–0.758 | 0.0001 | 0.655 | 0.533–0.805 | <0.0001 |

| Year of surgery (2012–2018 vs. 2005–2011) | 0.606 | 0.476–0.772 | <0.0001 | 0.884 | 0.692–1.131 | 0.3277 |

| Age (years, ≥59 vs. <59) | 1.420 | 1.155–1.745 | 0.0009 | 1.252 | 0.880–1.781 | 0.2108 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.828 | 1.489–2.245 | <0.0001 | 1.166 | 0.856–1.589 | 0.3297 |

| CCI (vs. 0) | ||||||

| 1 | 1.145 | 0.814–1.610 | 0.4367 | 0.940 | 0.663–1.333 | 0.7292 |

| 2 | 1.341 | 0.968–1.859 | 0.0778 | 0.924 | 0.598–1.426 | 0.7204 |

| 3 | 1.327 | 0.935–1.884 | 0.1128 | 0.805 | 0.497–1.305 | 0.3794 |

| 4–8 | 1.668 | 1.173–2.371 | 0.0044 | 1.244 | 0.758–2.042 | 0.3883 |

| BMI (kg/m2, vs. ≤24) | ||||||

| 24 to <28 | 0.941 | 0.750–1.182 | 0.6039 | 0.922 | 0.729–1.165 | 0.4961 |

| ≥28 | 1.259 | 0.780–2.031 | 0.3452 | 1.102 | 0.674–1.800 | 0.6995 |

| Smoking status (never vs. current/former) | 0.535 | 0.438–0.655 | <0.0001 | 0.886 | 0.646–1.213 | 0.4496 |

| Histologic subtypes (vs. adenocarcinoma) | ||||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2.015 | 1.586–2.561 | <0.0001 | 0.892 | 0.673–1.183 | 0.4276 |

| Others | 2.862 | 2.029–4.038 | <0.0001 | 1.706 | 1.188–2.449 | 0.0038 |

| Pathological TNM stage (vs. IA) | ||||||

| IB | 3.999 | 2.666–5.999 | <0.0001 | 3.649 | 2.427–5.484 | <0.0001 |

| IIA | 11.661 | 7.470–18.204 | <0.0001 | 9.944 | 6.250–15.819 | <0.0001 |

| IIB | 10.845 | 5.993–19.625 | <0.0001 | 10.072 | 5.432–18.676 | <0.0001 |

| IIIA | 19.642 | 13.055–29.550 | <0.0001 | 17.510 | 11.546–26.555 | <0.0001 |

The total number of patients in the Cox regression before adjustment was 2054 (1027 each group). BMI: Body mass index; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI: Confidence interval; DFS: Disease-free survival; HR: Hazard ratio; PSM: Propensity score matching; Tα1: Thymosin α1; TNM: Tumor-Node-Metastasis.

Table 3.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression for OS after PSM.

| Univariable analysis | Multivariable model | |||||

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value |

| Adjuvant Tα1 treatment (yes vs. no) | 0.505 | 0.394–0.646 | <0.0001 | 0.548 | 0.426–0.705 | <0.0001 |

| Year of surgery (2012–2018 vs. 2005–2011) | 0.700 | 0.525–0.933 | 0.0149 | 0.911 | 0.681–1.218 | 0.5286 |

| Age (years, ≥59 vs. <59) | 1.769 | 1.366–2.289 | <0.0001 | 1.554 | 0.981–2.462 | 0.0604 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 2.031 | 1.576–2.617 | <0.0001 | 1.089 | 0.740–1.603 | 0.6641 |

| CCI (vs. 0) | ||||||

| 1 | 0.861 | 0.552–1.341 | 0.5068 | 0.686 | 0.435–1.082 | 0.1052 |

| 2 | 1.249 | 0.836–1.867 | 0.2781 | 0.808 | 0.462–1.414 | 0.4551 |

| 3 | 1.499 | 0.987–2.277 | 0.0577 | 0.858 | 0.467–1.578 | 0.6226 |

| 4–8 | 1.853 | 1.216–2.821 | 0.0041 | 1.299 | 0.695–2.429 | 0.4123 |

| BMI (kg/m2, vs. ≤24) | ||||||

| 24 to <28 | 0.945 | 0.720–1.239 | 0.6807 | 0.886 | 0.669–1.173 | 0.3964 |

| ≥28 | 0.676 | 0.317–1.440 | 0.3102 | 0.511 | 0.236–1.106 | 0.0881 |

| Smoking status (never vs. current/former) | 0.475 | 0.372–0.606 | <0.0001 | 0.772 | 0.526–1.132 | 0.1846 |

| Histologic subtypes (vs. adenocarcinoma) | ||||||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 2.248 | 1.703–2.968 | <0.0001 | 1.136 | 0.819–1.574 | 0.4454 |

| Others | 2.972 | 2.006–4.405 | <0.0001 | 2.019 | 1.333–3.058 | 0.0009 |

| Pathological TNM stage (vs. IA) | ||||||

| IB | 4.369 | 2.533–7.537 | <0.0001 | 3.819 | 2.210–6.598 | <0.0001 |

| IIA | 12.771 | 7.126–22.888 | <0.0001 | 9.966 | 5.451–18.219 | <0.0001 |

| IIB | 10.058 | 4.778–21.172 | <0.0001 | 7.808 | 3.627–16.809 | <0.0001 |

| IIIA | 19.327 | 11.201–33.348 | <0.0001 | 17.221 | 9.926–29.878 | <0.0001 |

The total number of patients in the Cox regression before adjustment was 2054 (1027/group).

BMI: Body mass index; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; CI: Confidence interval; HR: Hazard ratio; OS: Overall survival; PSM: Propensity score matching; Tα1: Thymosin α1; TNM: Tumor-Node-Metastasis.

Medication duration

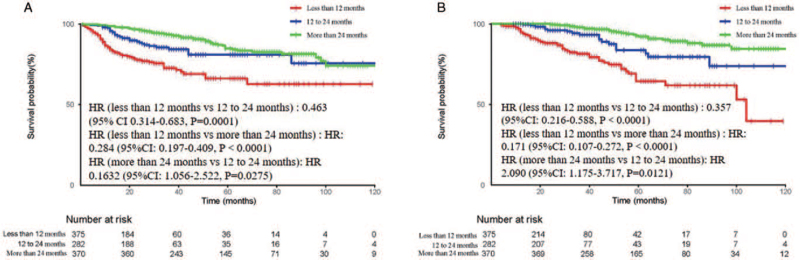

To investigate the effect of the duration of medication on the long-term outcomes, the patients in the Tα1 group were further divided into three groups: < 12 months (n = 375), 12 to 24 months (n = 282), and >24 months (n = 370). The median duration of medication was 4, 18, and 36 months, respectively. The median follow-up was 20 (range, 4–159) months. There were significant differences in DFS and OS among the three subgroups. The 5-year DFS rates for the three groups were 66.1%, 81.0%, and 84.7%, respectively. The 5-year OS rates were 64.5%, 83.7%, and 92.2%, respectively [Figure 3].

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for (A) DFS and (B) OS based on the duration of administration. DFS: Disease-free survival; HR: Hazard ratio; OS: Overall survival.

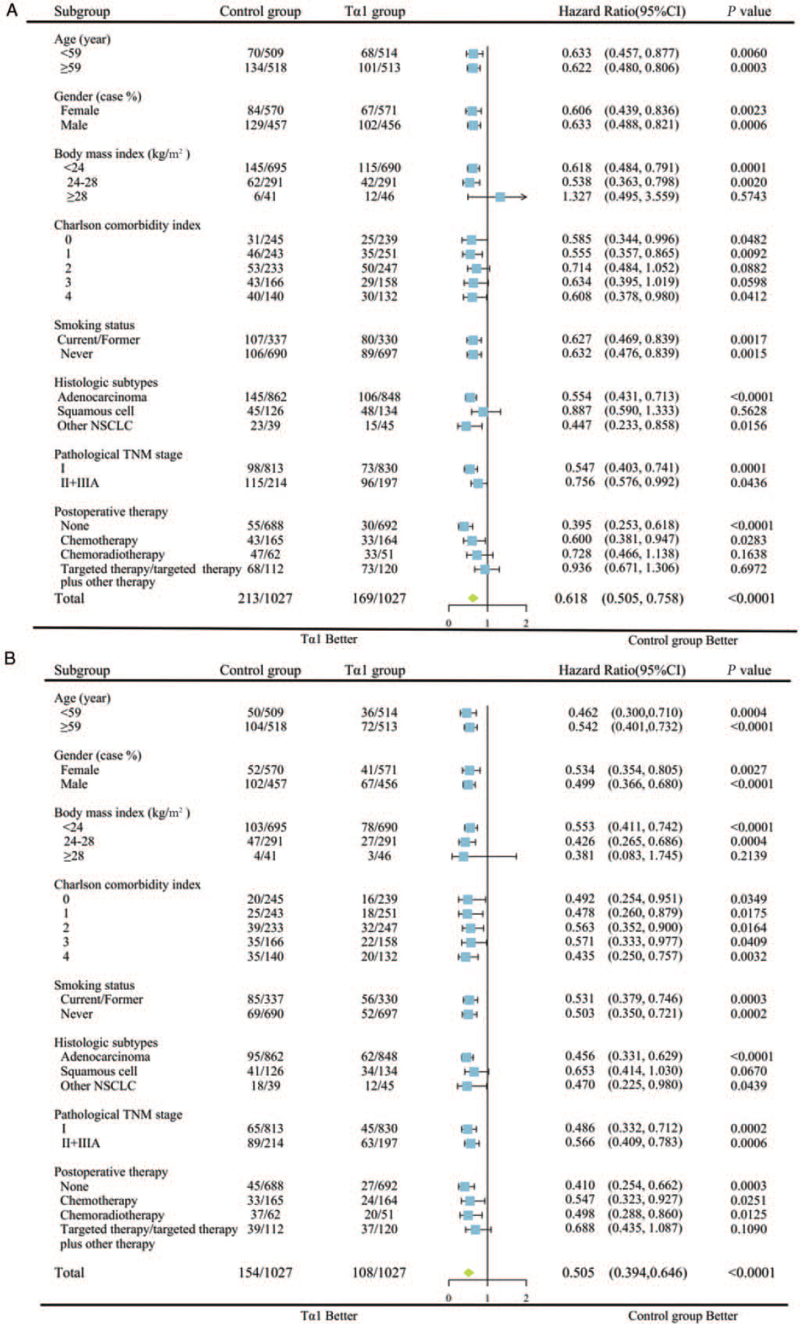

Subgroup analyses for OS and DFS

In order to identify which specific subgroups were more likely to benefit from adjuvant Tα1 treatment, subgroup analyses for OS and DFS were performed after PSM. The patients were divided into subgroups by median age, sex, BMI, CCI, smoking status, histological subtypes, pathological TNM stage, and adjuvant therapy.

The patients in the different subgroups of age, sex, smoking status, and pathological TNM stage benefited from adjuvant Tα1 treatment when considering DFS and OS [Figure 4]. As for comorbidities, although only those patients with CCI 0 and 1 had improved DFS in the Tα1 group, all subgroups showed better OS. The patients with BMI >28 kg/m2 and those with squamous cell carcinoma might not benefit from postoperative Tα1 injection. Moreover, as for the combination with other adjuvant drugs, patients without postoperative adjuvant therapy and those who received chemotherapy alone had better DFS and OS in the Tα1 group, while those who received chemoradiotherapy had a better OS. The patients who received targeted therapy had neither DFS nor OS benefits in the Tα1 group.

Figure 4.

Subgroup analysis of (A) DFS and (B) OS between the Tα1 group and control group in the matched cohort. CI: Confidence interval; DFS: Disease-free survival; HR: Hazard ratio; OS: Overall survival; Tα1: Thymosin α1.

Discussion

This study showed a significant survival advantage of Tα1 therapy in patients with NSCLC and R0 resection. It yielded a 5-year DFS rate of 77.3% and a 5-year OS rate of 83.3%, whereas patients without Tα1 therapy had DFS and OS rates of 64.7% and 72.7%, respectively. Combining the results from univariable and multivariable Cox regression analyses, it reasonably suggests that Tα1 therapy is an independent predictor of DFS and OS. Besides, subgroup analyses showed that Tα1 as an immunomodulatory therapy improved the DFS and/or OS in all subgroups of age, sex, CCI, smoking status, and pathological TNM stage, especially for patients with non-squamous cell NSCLC and no targeted therapy.

As an immunomodulator for cancer therapy, Tα1 has been used in liver cancer, melanoma, and lung cancer for decades,[12] but its efficacy and safety in NSCLC have not been well characterized. It has been confirmed that the combination of cyclophosphamide, murine interferon α/β, and Tα1 has a certain effect on the treatment of advanced lung cancer in mouse models,[17] and it has also been demonstrated that Tα1 could inhibit the growth of lung cancer cells and prolong the survival in mouse models.[18] Still, there is a lack of solid clinical evidence on the effects of Tα1 in lung cancer patients. The first clinical study for NSCLC treatment with Tα1 was reported by Schulof et al[14] in 1985. That study showed that Tα1 treatment after radiotherapy was associated with significant improvements in recurrence-free survival (RFS) and OS for NSCLC patients. Still, that study only enrolled 42 patients with a short follow-up (8–108 weeks). Several mechanisms might be related to the efficacy of Tα1 in improving the outcomes. Tα1 can trigger the differentiation of human CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells into CD3+CD4+ T cells,[19] which play a crucial role in tumor immune surveillance and pathogen clearance. Tα1 has immunomodulating effects by primarily increasing the ability of T cells to produce a variety of cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-2, IL-7, IL-10, IL-12, IL-15, interferon-α, and interferon-γ and further increasing the efficiency of T-cell maturation.[20] Tα1 can also promote dendritic cells, natural killer (NK) cells, and macrophage activity.[21–23] Moreover, Tα1 increases the expression of the major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) in lymphoid cells.[24] Immune system dysregulation plays a significant role in cancer progression. Besides these immunomodulatory effects, Tα1 can exert antitumor effects by acting directly on tumor cells. Moody et al[25] found that biologically active Tα1 receptors were present on NCI-H1299 NSCLC cells, and Tα1 could inhibit lung cancer growth in vivo and in vitro by stimulating arachidonic acid release. Giuliani et al[24] showed that the treatment of murine and human tumor cell lines with Tα1 could increase the expression of MHC-I.[25] Studies also revealed the antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of Tα1 on lung cancer, breast cancer, and leukemia cells.[18,26,27] The immunomodulatory effect and direct action on tumor cells of Tα1 might be beneficial in increasing antitumor immunity of the tumor-bearing host, which improves the survival outcomes.

Nevertheless, which specific subgroups of patients are more likely to benefit from Tα1 therapy remains an issue. This study suggests prognostic benefits of Tα1 therapy in all subgroups of age, sex, smoking history, CCI, and stage I–III lung cancer. Patients who were not eligible for adjuvant therapy (eg, stage I disease not requiring postoperative adjuvant therapy) and those who received adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy also had benefits in OS. On the other hand, there was no survival benefit from Tα1 therapy in patients with a BMI >28 kg/m2. It might be because a dose of only 1.6 mg might be insufficient in obese patients. The results also showed that there was no survival benefit for squamous cell carcinoma. Patients who received targeted therapy (alone or plus chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy) had neither DFS nor OS benefits in the Tα1 group. These results might help clinicians target the patients who are likely to benefit from Tα1 therapy.

More importantly, Tα1 treatment led to a survival benefit in early (stage I) and locally advanced (stage II and IIIA) stages. For patients with stage I NSCLC, surgery with curative intent is the standard treatment, but approximately, 30% to 40% of the postoperative patients die of recurrent disease.[28] The indication of adjuvant treatment remains a matter of debate,[29] and there is still no standard adjuvant treatment regimen for stage I patients. The results of our study have a guiding value for the adjuvant treatment of stage I NSCLC and might provide an adjuvant treatment option for these patients. Adjuvant cisplatin-based chemotherapy is recommended for R0-resected stage II and IIIA NSCLC to eradicate any remaining cancer cells and prolong survival.[30] Several clinical trials evaluating Tα1 with chemotherapy have been reported. Garaci et al[31] demonstrated that sequential chemoimmunotherapy based on cisplatin, etoposide, Tα1, and interferon-α2a could improve the response rate of chemotherapy. Similarly, combined treatment with Tα1 and low-dose interferon-α after ifosfamide enhanced the response rates compared with chemotherapy alone (33% vs. 10%).[13] A recent meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials, including 1925 late-stage NSCLC patients from China, evaluated Tα1 and chemotherapy combination therapy compared with chemotherapy alone and showed that the addition of Tα1 could improve antitumor immunity, tumor response, quality of life, and the 1-year OS rate.[10] The results of the present study are consistent with the previous studies, and the OS was significantly longer in the patients with chemotherapy combined with Tα1. It might benefit from the increased response rate of chemotherapy. In addition to chemotherapy, postoperative adjuvant targeted therapy is one of the alternative treatment modalities for patients with sensitive gene mutations.[32] Nevertheless, there are no previous clinical studies about the efficacy of Tα1 combined with targeted therapy for lung cancer. This study's findings suggest no DFS benefits in patients treated with targeted therapy and targeted therapy plus other therapies combined with Tα1. It indicates that Tα1 might not be synergistic with targeted therapy or that the effect of targeted therapy in sensitive tumors is stronger and masks the effect of Tα1.

Another issue that bothers clinicians is how long Tα1 should be administered. This study suggests significant differences in DFS and OS among <12 months, 12 to 24 months, and >24 months of Tα1 therapy. Therefore, we recommend that the duration of medication should preferably be >24 months. Still, it should be confirmed by prospective trials.

In this study, there were no drug-related serious adverse events that affected the survival of the patients nor adverse events that led to Tα1 discontinuation. No new safety signals were identified. Tα1 was well tolerated by all patients.

There are several limitations to this study. First, although we attempted to balance the variables between the two groups using PSM, selection bias and unobserved confounding associated with the retrospective nature of the study cannot be eliminated. Second, the generalization of the observed outcomes in the subgroup analyses to clinical practice must be cautiously scrutinized because the sample size for some subsets in this series was small. Third, the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group's performance status was missing in most patients. Finally, the data were derived from a single institution. Thus, more studies from other institutions, preferably multicenter studies, are encouraged to validate our results.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that Tα1 as adjuvant therapy could delay recurrence and prolong OS in stage I–III NSCLC patients following margin-free resection, except for patients with squamous carcinoma and those who received targeted therapy. The duration of Tα1 treatment is recommended to be >24 months.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the 1.3.5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Nos. ZYGD18021 and ZYJC18009).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Guo CL, Mei JD, Jia YL, Gan FY, Tang YD, Liu CW, Zeng Z, Yang ZY, Deng SY, Sun X, Liu LX. Impact of thymosin α1 as an immunomodulatory therapy on long-term survival of non-small cell lung cancer patients after R0 resection: a propensity score-matched analysis. Chin Med J 2021;134:2700–2709. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001819

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molina JR, Yang P, Cassivi SD, Schild SE, Adjei AA. Non-small cell lung cancer: epidemiology, risk factors, treatment, and survivorship. Mayo Clin Proc 2008; 83:584–594. doi: 10.4065/83.5.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ghysen K, Vansteenkiste J. Immunotherapy in patients with early stage resectable nonsmall cell lung cancer. Curr Opin Oncol 2019; 31:13–17. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldstraw P, Crowley J, Chansky K, Giroux DJ, Groome PA, Rami-Porta R, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: proposals for the revision of the TNM stage groupings in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of malignant tumours. J Thorac Oncol 2007; 2:706–714. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31812f3c1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sambi M, Bagheri L, Szewczuk MR. Current challenges in cancer immunotherapy: multimodal approaches to improve efficacy and patient response rates. J Oncol 2019; 2019:4508794.doi: 10.1155/2019/4508794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goel G, Sun W. Cancer immunotherapy in clinical practice - the past, present, and future. Chin J Cancer 2014; 33:445–457. doi: 10.5732/cjc.014.10123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danielli R, Fonsatti E, Calabro L, Di Giacomo AM, Maio M. Thymosin alpha1 in melanoma: from the clinical trial setting to the daily practice and beyond. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2012; 1270:8–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maio M, Mackiewicz A, Testori A, Trefzer U, Ferraresi V, Jassem J, et al. Large randomized study of thymosin alpha 1, interferon alfa, or both in combination with dacarbazine in patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28:1780–1787. doi: 10.1200/jco.2009.25.5208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Danielli R, Cisternino F, Giannarelli D, Calabro L, Camerini R, Savelli V, et al. Long-term follow up of metastatic melanoma patients treated with Thymosin alpha-1: investigating immune checkpoints synergy. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2018; 18:77–83. doi: 10.1080/14712598.2018.1494717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng FL, Xiao Z, Wang CQ, Jiang Y, Shan JL, Hu SS, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of synthetic thymic peptides with chemotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 27 randomized controlled trials following the PRISMA guidelines. Int Immunopharmacol 2019; 75:105747.doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2019.105747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King R, Tuthill C. Immune modulation with thymosin alpha 1 treatment. Vitam Horm 2016; 102:151–178. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Costantini C, Bellet MM, Pariano M, Renga G, Stincardini C, Goldstein AL, et al. A reappraisal of thymosin alpha1 in cancer therapy. Front Oncol 2019; 9:873.doi: 10.3389/fonc.2019.00873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salvati F, Rasi G, Portalone L, Antilli A, Garaci E. Combined treatment with thymosin-alpha1 and low-dose interferon-alpha after ifosfamide in non-small cell lung cancer: a phase-II controlled trial. Anticancer Res 1996; 16:1001–1004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schulof RS, Lloyd MJ, Cleary PA, Palaszynski SR, Mai DA, Cox JW, Jr, et al. A randomized trial to evaluate the immunorestorative properties of synthetic thymosin-alpha 1 in patients with lung cancer. J Biol Response Mod 1985; 4:147–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stuart EA. Matching methods for causal inference: a review and a look forward. Stat Sci 2010; 25:1–21. doi: 10.1214/09-STS313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garaci E, Mastino A, Pica F, Favalli C. Combination treatment using thymosin alpha 1 and interferon after cyclophosphamide is able to cure Lewis lung carcinoma in mice. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1990; 32:154–160. doi: 10.1007/BF01771450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moody TW. Thymosin alpha1 as a chemopreventive agent in lung and breast cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2007; 1112:297–304. doi: 10.1196/annals.1415.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knutsen AP, Freeman JJ, Mueller KR, Roodman ST, Bouhasin JD. Thymosin-alpha1 stimulates maturation of CD34+ stem cells into CD3+4+ cells in an in vitro thymic epithelia organ coculture model. Int J Immunopharmacol 1999; 21:15–26. doi: 10.1016/s0192-0561(98)00060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldstein AL, Goldstein AL. From lab to bedside: emerging clinical applications of thymosin alpha 1. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2009; 9:593–608. doi: 10.1517/14712590902911412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serrate SA, Schulof RS, Leondaridis L, Goldstein AL, Sztein MB. Modulation of human natural killer cell cytotoxic activity, lymphokine production, and interleukin 2 receptor expression by thymic hormones. J Immunol 1987; 139:2338–2343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Umeda Y, Sakamoto A, Nakamura J, Ishitsuka H, Yagi Y. Thymosin alpha 1 restores NK-cell activity and prevents tumor progression in mice immunosuppressed by cytostatics or X-rays. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1983; 15:78–83. doi: 10.1007/BF00199694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serafino A, Pica F, Andreola F, Gaziano R, Moroni N, Moroni G, et al. Thymosin alpha1 activates complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis in human monocyte-derived macrophages. J Innate Immun 2014; 6:72–88. doi: 10.1159/000351587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Giuliani C, Napolitano G, Mastino A, Di Vincenzo S, D’Agostini C, Grelli S, et al. Thymosin-alpha1 regulates MHC class I expression in FRTL-5 cells at transcriptional level. Eur J Immunol 2000; 30:778–786. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200003)30:3<778::aid-immu778>3.0.co;2-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moody TW, Fagarasan M, Zia F, Cesnjaj M, Goldstein AL. Thymosin alpha 1 down-regulates the growth of human non-small cell lung cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 1993; 53:5214–5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fan YZ, Chang H, Yu Y, Liu J, Wang R. Thymosin alpha1 suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in human leukemia cell lines. Peptides 2006; 27:2165–2173. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo Y, Chang H, Li J, Xu XY, Shen L, Yu ZB, et al. Thymosin alpha 1 suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells through PTEN-mediated inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Apoptosis 2015; 20:1109–1121. doi: 10.1007/s10495-015-1138-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brock MV, Hooker CM, Ota-Machida E, Han Y, Guo M, Ames S, et al. DNA methylation markers and early recurrence in stage I lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2008; 358:1118–1128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0706550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Terroba E, Behrens C, de Miguel FJ, Agorreta J, Monso E, Millares L, et al. A novel protein-based prognostic signature improves risk stratification to guide clinical management in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma patients. J Pathol 2018; 245:421–432. doi: 10.1002/path.5096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arriagada R, Bergman B, Dunant A, Le Chevalier T, Pignon JP, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with completely resected non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 350:351–360. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa031644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garaci E, Lopez M, Bonsignore G, Giulia MD, D’Aprile M, Favalli C, et al. Sequential chemoimmunotherapy for advanced non-small cell lung cancer using cisplatin, etoposide, thymosin-alpha 1 and interferon-alpha 2a. Eur J Cancer 1995; 31A:2403–2405. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00477-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu YL, Herbst RS, Mann H, Rukazenkov Y, Marotti M, Tsuboi M. ADAURA: Phase III, double-blind, randomized study of osimertinib versus placebo in EGFR mutation-positive early-stage NSCLC after complete surgical resection. Clin Lung Cancer 2018; 19:e533–e536. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2018.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.