Abstract

Severe oligohydramnios (OH) due to prolonged loss of amniotic fluid can cause pulmonary hypoplasia. Animal model of pulmonary hypoplasia induced by amniotic fluid drainage is partly attributed to changes in mechanical compression of the lung. Although numerous studies on OH-model have demonstrated changes in several individual proteins, however, the underlying mechanisms for interrupting normal lung development in response to a decrease of amniotic fluid volume are not fully understood. In this study, we used a proteomic approach to explore differences in the expression of a wide range of proteins after induction of OH in a mouse model of pulmonary hypoplasia to find out the signaling/molecular pathways involved in fetal lung development. Liquid chromatography-massspectromery/mass spectrometry analysis found 474 proteins that were differentially expressed in OH-induced hypoplastic lungs in comparison to untouched (UnT) control. Among these proteins, we confirmed the downregulation of AKT1, SP-D, and CD200, and provided proofof-concept for the first time about the potential role that these proteins could play in fetal lung development.

Keywords: AKT1, lung, mouse model, oligohydramnios, SP-D

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Mechanical forces are critical for fetal lung development.1 The fetus secretes fluid into the lumen of the lung creating a constant transpulmonary pressure that is critical for normal lung development.2 Tracheal ligation in fetal sheep increased lung distension and promoted lung development; whereas the opposite effect was observed when tracheal lung fluid was drained.3 These studies clearly suggest that mechanical forces secondary to fluid distention are a major determinant for fetal lung growth.

Underdevelopment of the lung, or pulmonary hypoplasia, is a common finding in neonatal autopsies (around 22%).4 Oligohydramnios (OH), congenital diaphragmatic hernia, and renal agenesis are major causes of pulmonary hypoplasia and neonatal mortality and morbidity. OH is a state in which the volume of amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus in utero is substantially decreased. The sources of amniotic fluid are maternal plasma, fetal membrane, and fetal urine, when fetal kidneys start to function. In humans, rupture of the fetal membrane can cause OH.5 In an experimental model, we and others have shown the induction of pulmonary hypoplasia by amniotic fluid drainage in the canalicular stages of lung development.6–8 The likely mechanism is a reduction in the distention of the lung secondary to a decrease of the volume of fluid in the potential airways and air spaces.9–11 However, the molecular mechanisms by which a decrease of lung distention compromises lung development are not well understood.

Prior studies have demonstrated that several factors are involved in lung development. For example, in a rat model of OH induced at the pseudoglandular stage of lung development, the crucial role of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and its receptors for alveolarization during normal lung development was demonstrated.12 Altered extracellular matrix caused by OH might correspond to the altered respiratory function of the offspring.13 Indeed, in hypoplastic human fetal lungs, the absence of elastic tissue is associated with maternal OH.14 Furthermore, OH induced at the pseudoglandular stage of lung development in rat showed decreased expression of collagen I.15 Altogether, these studies indicate an important role of extracellular matrix in lung development mediated by mechanical signals.

Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) plays an important role in endothelial cell differentiation and angiogenesis. However, in a fetal rat model of OH, angiogenesis was compromised without affecting the expression of VEGF.13 These studies suggest that, in addition to VEGF, other angiogenic factors may be involved in regulating fetal lung angiogenesis. These studies also emphasize the complexity of fetal lung angiogenesis.

To better understand the differentially expressed proteins in a mouse pulmonary hypoplasia model, we used a proteomic approach as a system-based screening method. The present investigations are a continuation of our previous studies6 with the long-term goal of elucidating the underlying mechanism of lung development mediated by mechanical forces.

This study provides a wealth of information to investigate the underlying cellular and molecular mechanism of the development of the lung associated with mechanical force.

2 |. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1 |. Animal experiment to induce oligohydramnios (OH)

Surgical procedures used in this study were approved by the Lifespan Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Rhode Island. We followed the procedure to induce pulmonary hypoplasia on mice by OH as previously described.6 Frozen lungs were submitted to COBRE Center for Cancer Research Development Proteomics Core Facility of Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI to use for the proteomics analysis. Detailed methods of OH induction in an animal experiment is provided in Supplementary File 1.

2.2 |. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry

The liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis was performed on a fully automated proteomic technology platform that includes an Agilent 1200 Series Quaternary HPLC system (Agilent Technologies) connected to a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The LC-MS/MS setup was used as described earlier.16 The MS/MS spectra were acquired at a resolution of 17,500, with a targeted value of 2 × 106 ions or a maximum integration time of 200 ms. The ion selection abundance threshold was set at 8.0 × 102 with charge state exclusion of unassigned and z = 1, or 6–8 ions and dynamic exclusion time of 30 s.

2.3 |. Database search and label-free quantitative analysis

Peptide spectrum matching of LC-MS/MS spectra of each file was searched against the Uniport Mus musculus database (TaxonID: 10090, downloaded on 02/09/2015) using the SEQUEST algorithm within Proteome Discoverer v 2.3 software (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The SEQUEST database search was performed with the following parameters: trypsin enzyme cleavage specificity, two possible missed cleavages, 10 ppm mass tolerance for precursor ions, 0.02 Da mass tolerance for fragment ions. Search parameters permitted dynamic modification of methionine oxidation (+15.9949 Da) and static modification of carbamidomethylation (+57.0215 Da) on cysteine. Peptide assignment from the database search was filtered down to a 1% false discovery rate. The relative label-free quantitative and comparative among the samples were performed using the Minora algorithm and the adjoining bioinformatics tools of the Proteome Discoverer 2.3 software. To select proteins that show a statistically significant change in abundance between two groups, a threshold of 1.5-fold change with p value (0.05) was selected. Proteomics data is submitted in a public repository (MassIVE MSV 000086641).

2.4 |. Bioinformatics analysis

The proteomic data set was further analyzed by the adjoining tools of the Proteome Discoverer v2.3 software. The gene enrichment analysis including Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) and WiKi pathway analysis of the significantly abundant proteins was conducted with an open-source bioinformatics platform named ShinyGO (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/). STRING, an open-source protein–protein interaction network was used to develop our protein of interest network.

2.5 |. Statistics analysis

Student t-test or Mann–Whitney test (GraphPad prism software, version 5.04) were used for statistical analyses to identify differences between control and OH tissues. p ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Further details of the methodology are described in Supplementary Materials.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Model of pulmonary hypoplasia

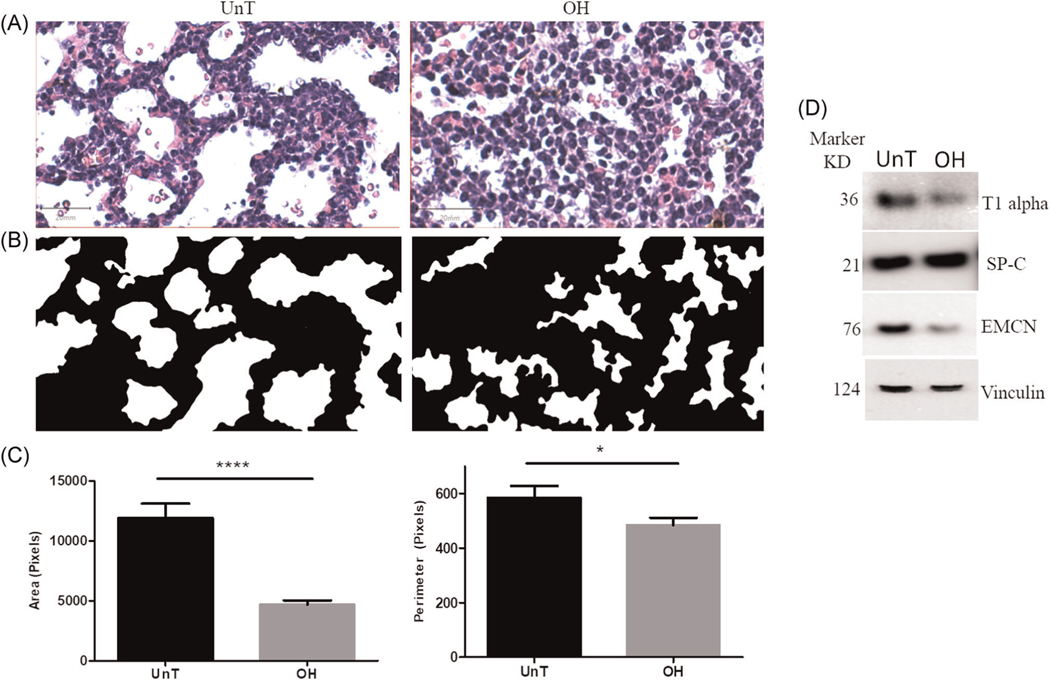

To confirm the presence of pulmonary hypoplasia in OH lungs, morphometric analysis was performed on H&E stained histological sections. Our results confirmed our previous findings,6 and clearly showed a significant reduction in lung space size as measured by area and perimeter (Figure 1A–C).

FIGURE 1.

Confirmation of pulmonary hypoplasia mouse model. (A)–(C) represent the effect of oligohydramnios on the morphometry of distal air space. (A) representative hematoxylin and eosin-stained histological sections (×20) showing a marked decrease in the air spaces in OH lungs when compared to UnT control, (B) binary image of the spaces from (A) and (C) analysis of the size of the spaces using the area and perimeter parameters showing a significant decrease of space size on OH (n = 6) in comparison to UnT (n = 5). (D) Representative western blots (blot of one replicate) showing the protein expression in OH lung compare to UnT. Name of the proteins was shown at the right side of the blot and corresponding molecular markers were shown at the left. T1 alpha and EMCN were downregulated and SP-C was unchanged compared to UnT lung. Vinculin served as endogenous control. The protein used in this assay was taken from the same samples used in proteomic analysis. *p < .05 and ****p < .0001. EMCN, endomucin; OH, oligohydramnios; UnT, untouched

We also tested the reproducibility of the expression of T1 alpha and SP-C (alveolar epithelial cell type I [AEC1] and type II [AEC2] markers respectively, and endomucin (EMCN, endothelial cell marker) proteins in OH lung, as a justification of using the mouse model (Figure 1D). A representative immunoblot shows that the expression of T1 alpha, and EMCN decreased in OH lung when compared with untouched controls (UnT) whereas the abundance of SP-C protein did not change. These studies validate the pulmonary hypoplasia mouse model, as we have previously reported.6 Tissues from these lungs were used to carry out the proteomic analysis in this study.

3.2 |. Identification of differentially expressed proteins in oligohydramnios induced pulmonary hypoplasia

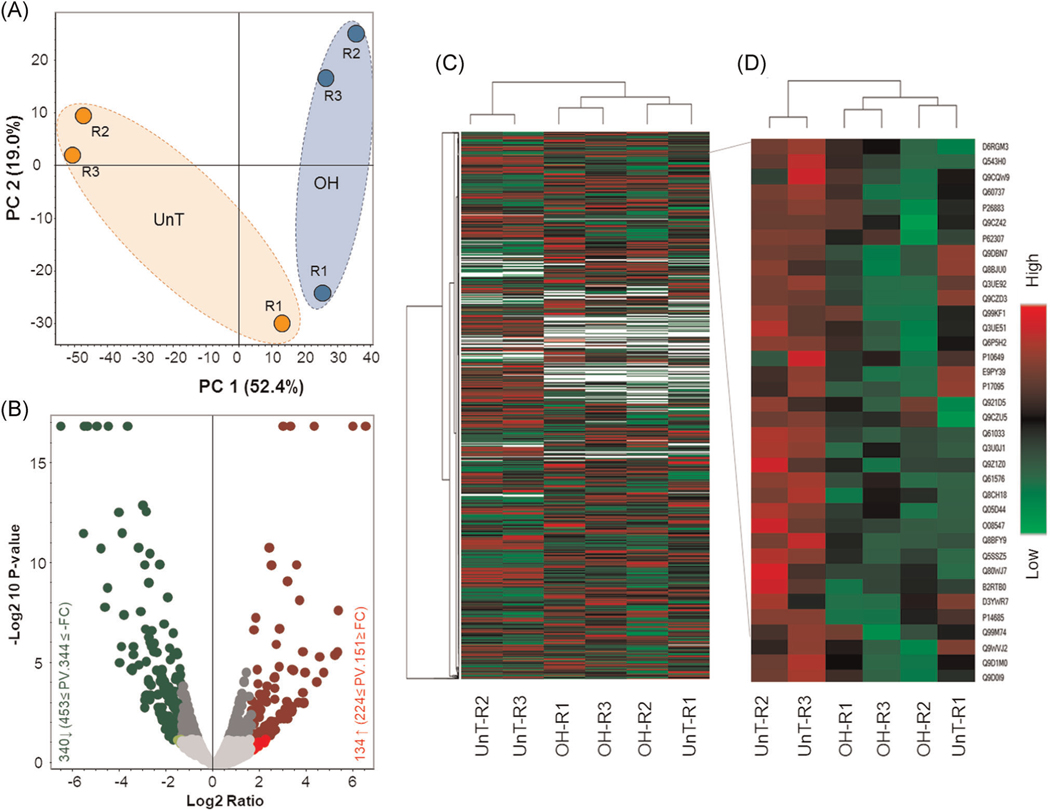

A comparative label-free relative quantitative proteomic analysis was performed between UnT and OH lungs. Three biological replicates were used in each group of samples. A total of 23,587 unique peptides corresponding to 3385 unique proteins were identified by LC-MS/MS analysis. Principal component analysis demonstrated comparatively close clustering of total normalized protein abundance among the replicates in each condition with a clear distinction between the conditions (parabolic structures; light orange, UnT & light blue, OH) (Figure 2A). The total number of unique protein set (3385) identified by LC-MS/MS analysis was further subjected for label-free quantitative analysis. A total of 134 and 340 proteins were found to be increased and decreased respectively in abundance at least −2 to 2 folds with significant p value (≤0.05) in OH lungs compared with UnT. In volcano plot, x-axis and y-axis represent the differentially expressed proteins with fold changes and statistical significance (−log10 of p value) respectively (Figure 2B). Profiles of differentially expressed proteins are shown using the clustering method by generating a heat map. Proteins were grouped based on their similarity of expression pattern and are shown in a grid where each row and column represent protein and sample, respectively. Fold change of protein expression was set up at ≤−1.5 to ≥ 1.5 and p value at ≤ .05. Red and green colors indicate up and downregulation of protein expression respectively (Figure 2C). A closer view of a group of proteins that have similar expression patterns in each condition in all three replicates regardless of any outliers (Figure 2D).

FIGURE 2.

Comparative label-free quantitative proteomic analysis of hypoplastic (OH) and control fetal mouse lungs (UnT). Proteome from three biological replicates of each condition was subjected to quantitative analysis. (A) PCA analysis of total proteome data set showed comparatively close clustering of total normalized protein abundance of the replicates in each condition, however, distinct from other groups/conditions. Samples are colored by experimental conditions in which orange and blue represent normal and pulmonary hypoplasia, respectively. (B) shows the volcano plot analysis of the 3387 proteins subjected to the analysis. Significantly increased and decreased proteins in hypoplastic lungs compared with control lungs are marked as red and green, respectively. x-axis represents differentially expressed proteins with abundance by log2 ratio and y-axis represents statistical significance with −log 10 of p value. Gray dots are nonsignificant (p > .05) and below the threshold of the fold change (1.5-fold). (C) shows the heat map clustering of total differentially expressed protein pattern of each groups. (D) a group of proteins showed a very similar expression pattern in each condition in all three replicates regardless of outliers (one replicate from each condition). R1, R2, and R3 denote three replicate experiments. One lung for each condition was taken from each replicate experiment in LC-MS analysis. LC-MS, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry; PCA, principal component analysis

3.3 |. Classification and pathway analysis of differentially abundant proteins

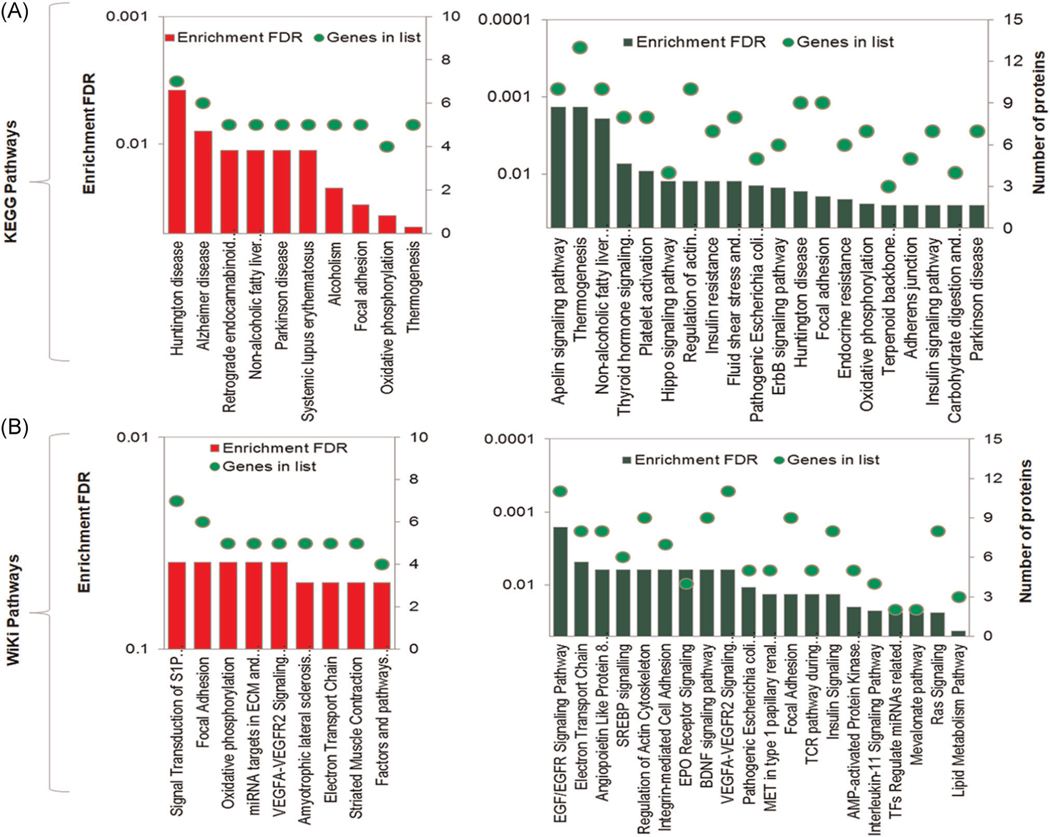

Pathway enrichment analysis was performed using differentially expressed proteins in OH lungs to identify the enriched affected biological pathways. KEGG and Wiki pathway analysis for 340 downregulated proteins revealed that Apelin signaling and EGF/EGFR signaling are major enriched pathways respectively (Figures 3A,B, right panel). These pathways are involved in several cellular processes including cell proliferation, survival, differentiation, and angiogenesis.17 Akt1 gene is involved in the majority of the enriched signaling pathways. Huntington’s disease and signal transduction S1P receptor pathways are enriched as most affected by 134 upregulated proteins in OH lung by KEGG and Wiki pathway analysis respectively (Figure 3A,B, left panel).

FIGURE 3.

Gene enrichment pathway analysis of the significantly abundant proteins. Significantly increased (340) and decreased (134) proteins in hypoplastic lung compared with the control lungs are used in KEGG and Wiki pathways analysis as shown in (A) and (B) respectively. The red and dark green bar diagrams represent the increased and decreased proteins in hypoplastic lung, respectively. Green circles indicate the number of genes identified in each pathway. Enrichment FDR p value ≤ .05 was used in the analysis. The Analysis was conducted with an open-source bioinformatics platform named Shiny GO (http://bioinformatics.sdstate.edu/go/). FDR, false discovery rate; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

3.4 |. Verification of proteomic data

A specific group of candidate proteins important for fetal lung development was selected to verify the proteomic data set. These included AKT1. SP-D and CD200.

AKT pathway plays a role in fetal lung development.18 AKT1, AKT2, and AKT3 are the three isoforms of AKT. Each isoform has unique and overlapping functions in the regulation of cellular proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, and survival.19 The role of specific AKT isoforms in lung development has not been investigated. Pathway enriched analysis in this study revealed the involvement of AKT1 isoform in most of the signaling pathways affected in oligohydramnios induced hypoplastic lung compared with the control.

There are four surfactant associated proteins; namely SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, and SP-D. Among them SP-C is expressed exclusively in AEC2 in the lung and is known as a canonical marker of this cell.20 In this study, the LC-MS/MS data revealed that among the four surfactant proteins, SP-D was significantly downregulated in OH lung. SP-D protein is well-known as a modulator of lung inflammation.21 Our data showed that there is no differential expression of any pro-inflammatory factors in the proteomic data set suggesting that an inflammatory response in OH lung is not activated. Thus, our proteomic data suggest the potential role of SP-D in fetal lung development independent of its role in inflammation.

The proteomics data in this study showed also a significant reduction of CD200 expression in OH lung compare to UnT suggesting the potential role of CD200 in fetal lung development. CD200 is widely spread in both pulmonary and nonpulmonary tissues. CD200 participates in autoimmune and allergic disorders, bone development, and reproductive biology.22 Developmental regulation of CD200 in rat lung has been documented 23 suggestings CD200 has a potential role in OH-induced pulmonary hypoplasia.

Based on our findings, where the proteomic analyses showed significant changes in these proteins, in addition to the above discussion describing the potential role of AKT1, SP-D, and CD200, we sought to validate the proteomic data quantitatively using western blot (Figure 4) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Quantification of protein expression in the lungs of fetal mice by western blot. Protein used in this assay was taken from the same pool as those were used in proteomic analysis. (A) and (B) represent immunoblotting and densitometric analysis respectively for the quantification of AKT1, AKT2, SP-D, and CD200 proteins. Vinculin represents the loading control for endogenous protein. Western blot analysis showed decreased expression of AKT1 in OH lungs compare to UnT lungs whereas AKT2 was unchanged. The expression of SP-D and CD200 also showed significant reduction in OH lungs. repl.1, repl.2, and repl.3 denote three replicate experiments. n = 3 per group. Densitometry analysis was performed for each target protein individually for three replicates relative to the mean of the UnT control and correspondence statistical significance were measured by t-test. *p < .05 & **p < .01

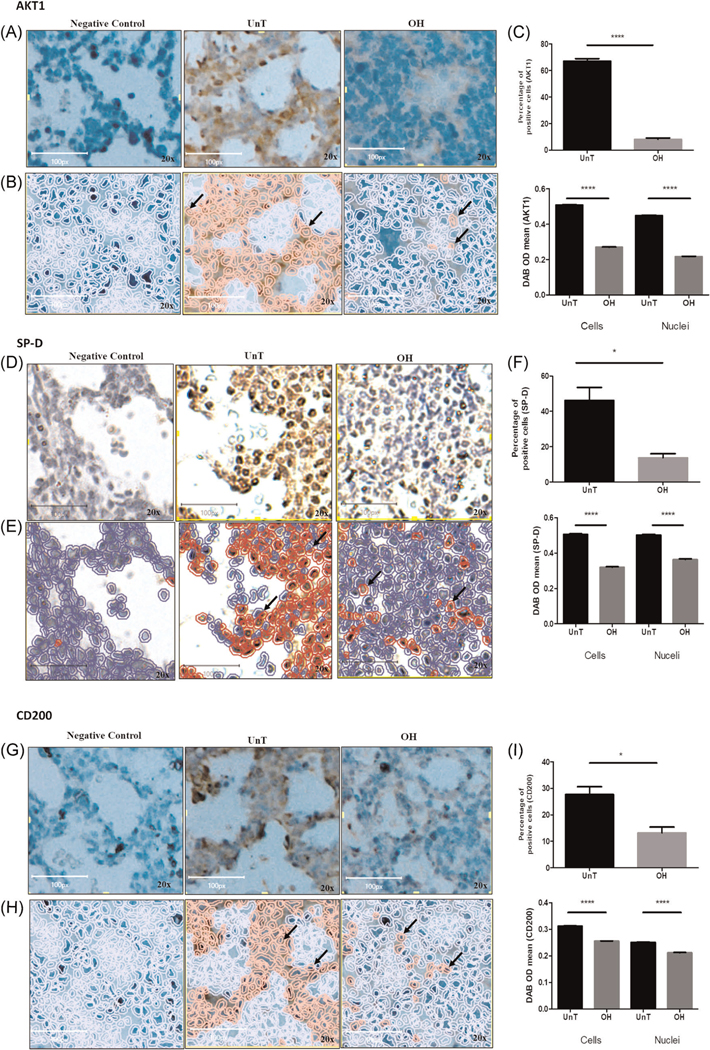

FIGURE 5.

Quantification of proteins in the tissue of fetal mice by IHC analysis. (A), (D), and (G) representative micrographic images of AKT1, SP-D, and CD200 stained sections of lung tissue, respectively. Left and right images (×20) are of negative control (for the detection of AKT1, SP-D, and CD200, respectively) and OH lung, respectively. Middle represents the UnT lung of corresponding proteins. (B), (E), and (H) analysis of the DAB positive cells as automatically analyzed using QuPath. Positive cells are in red. (C), (F), and (I) quantification of the images showed that the percentage of AKT1, SP-D, and CD200 positive cells in OH-lung were significantly decreased compare with UnT lungs (upper bar diagram respectively). The mean intensity of the AKT1, SP-D, and CD200 expressions in both nuclei and whole cells were also significantly reduced in OH lungs (lower bar diagram respectively). n = 3 per group. *p < .05 and ****p < .0001. Arrows pointing to positive cells. Images in this figure are subsets of the original whole images (Supplementary File 2). In (A) and (G) the brightness and contrast of the images were adjusted for publication purposes. The analyses were performed on the original untouched images. Images in (D) were captured with a different microscope as detailed in the supplementary methods. DAB, 3ʹ-diaminobenzidine; IHC, immunohistochemistry

Figure 4A,B represents the immunoblotting and densitometry analysis, respectively. Western blot confirmed the proteomic results by showing the significant decrease in the expression of AKT1 (p ≤ .05), SP-D (p ≤ .001), and CD200 (p < .05) in OH compared with UnT lung. AKT2 was used in this assay to test whether AKT1 was the AKT isoform specifically downregulated in OH lung.

IHC also showed reduced expression of AKT1, SP-D, and CD200 in OH lung tissue compared with UnT (Figures 5A, 5D, and 5G). Representative microscopic images of IHC stained sections to detect AKT1, SP-D, and CD200 are shown in Figures 5B, 5E, and 5H, respectively. Figures 5C, 5F, and 5I represent the quantitative analysis of the AKT1, SP-D, and CD200 expressing positive cells respectively as analyzed by QuPath. Image analysis showed that the percentage of positive cells is significantly decreased for AKT1 (p < .0001), SP-D (p < .05), and CD200 (p < .05) in OH compared with UnT lung. Optical density as a measure of protein expression level was also significantly reduced for AKT1 (p < .0001), SP-D (p < .0001), and CD200 (p < .0001) in both the nuclei and the whole cells. Figure 5 shows representative subsets of the original images, while image analysis was performed on the whole images (representative figures in Supplementary File 2).

4 |. DISCUSSION

Pulmonary hypoplasia secondary to OH can cause significant morbidity and mortality to the neonatal population.5 The precise mechanism by which OH induces lung hypoplasia remains unknown. In this study, we used LC-MS/MS proteomic analysis to elucidate the differences in the lung proteomic profile between OH-induced lung hypoplasia and UnT control. Our data identified a total of 474 proteins that were significantly differentially expressed in our experimental mouse model of lung hypoplasia including AKT1, SP-D, and CD200. Further analysis of the 340 downregulated proteins using KEGG and Wiki enrichments showed that the major significant enriched pathways were the Apelin and EGF/EGFR signaling pathways. Both of these signaling pathways are involved in cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival.24–26 Due to the large data set of differentially expressed proteins in OH lung, here we considered the downregulated proteins to avoid intricacy in the investigation in this study. Full list of significantly down and upregulated proteins are provided in Supplementary Data File 3. We believe these studies provide novel information on the potential mechanisms underlying lung development mediated by mechanical signals.

Apelin binding to apelin receptors transduces signals through G protein to a variety of signaling pathways including the PI3K-AKT pathway. PI3K-AKT pathway contributes to cell proliferation, survival, and differentiation in the development of the fetal murine lung.18 However, the role of specific AKT isoforms in lung development is not known. Our proteomic data revealed significant downregulation of AKT1 in OH-induced hypoplastic fetal mouse lung which was confirmed by western blot and IHC. Akt1 gene is involved in most of the pathways enriched by KEGG analysis including thermogenesis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, thyroid hormone signaling pathway, ErbB signaling pathway, focal adhesion, and insulin signaling pathway among others. Our investigations suggest that the pathways mediated by AKT1 may be critical in the pathogenesis of the developmental lung defect in response to OH. On the other hand, our western data revealed no changes in the AKT2 isoform in OH compared with UnT lungs, thus suggesting unique roles for different isoforms in lung development.

Alveolar epithelial cells type 1 (AEC1) and type II (AEC2) differentiation is a hallmark of the development of fetal lung.27 We had previously described in a murine model of pulmonary hypoplasia, that the decrease of external compression secondary to severe OH can compromise the differentiation of AEC1 cells in the distal lung.6 In this study, proteomic analysis revealed that the expression of PDK1 is significantly downregulated in OH lung, suggesting a role of PI3K-AKT pathway in lung development. This is an interesting finding, as AKT1 investigations have primarily focused on cancer research with only few studies looking at the role of AKT1 in adipose tissue28 and mammary gland development.29 Thus, we speculate that PI3K/PDk1-AKT signaling pathway may be important for ACE1 cell differentiation mediated by mechanical signals. Testing this hypothesis will be the focus of future studies.

Among the four proteins associated with alveolar surfactant namely SP-A, SP-B, SP-C, and SP-D, SP-C is known to be a canonical differentiation marker of alveolar AEC2 with its expression restricted to these cells.30 SP-D is expressed in different cells including nonpulmonary tissues.20 Our proteomic data revealed a significant downregulation of SP-D in OH lung, which was confirmed by western blot and IHC. The expression of SP-D is gradually increased, and distribution of this protein within the lung changes with the advancing gestation, where it is initially expressed in bronchial epithelial cells and later found in AEC2. But in lungs from patients with bronchopulmonary dysplasia, SP-D was barely detected.31 These data suggest an important role for this protein during lung development. SP-D is thought to play a role in surfactant homeostasis through unidentified signaling pathways.32 SP-D is a member of C-type lectin family. This protein is believed to participate only in innate immunity or non-antibody mediated host defense system in the lung due to its structural feature of collectins.21 Studies have provided evidence that in addition to their role in innate immunity, collectins could have other functions.33 Thus, SP-D seems to have other roles in addition to immunity, including a role in lung development as our findings suggest. In this study, the surgical procedure for the induction of OH did not trigger inflammatory signals in the fetal lung as evidenced by the proteomic analysis that did not show differential expression of any key pro-inflammatory cytokines. Thus, downregulation of SP-D in OH lung indicates a potential role in lung development independent of its role in immunity.

CD200 is a membrane glycoprotein that functions as an immunosuppressive signaling molecule.34 CD200 is widely spread in both pulmonary and nonpulmonary tissues and cells.22 In the lung, CD200 is expressed on AEC2, Clara cells, and endothelial cells. CD200 has a dynamic expression in the developing lung and is associated with alveolar capillary development in rat lung.23 Here, our results by proteomics analysis and further confirmed by western blot and IHC, revealed the downregulation of CD200 in a pulmonary hypoplasia mouse model. Furthermore, there is a reduction in lung angiogenesis, as previously demonstrated.6 Together these findings suggest a potential role for CD200 in angiogenesis within the developing lung. This hypothesis needs to be tested experimentally.

Although changes in the expression of AKT1,35,36 CD200,37 and SP-D 38,39 were observed in multiple pulmonary disorders, including lung fibrosis, BPD, RDS, Asthma, COPD, and lung cancer, however, the role of these proteins in lung development has not been explored. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report changes in these three proteins in the developing lung as a consequence of OH.

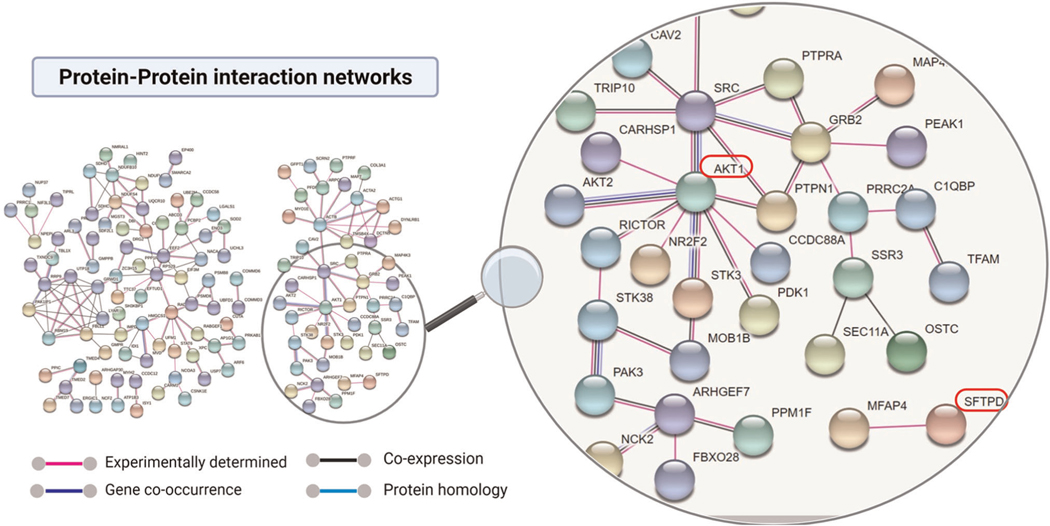

Using STRING (protein–protein interaction networks), we identified potential interactions among the significantly downregulated proteins and transcriptional regulators (Figure 6). Lung development is a complicated process and depends on the timely interplay of highly regulated molecular signals.40 For example, TFAM (transcription factor A, mitochondrial) is a nuclear gene critical for transcription of the mitochondrial genome,41 and is required for lung development.42 In protein–protein interaction networks, TFAM is present in an interaction clustered with a central molecule, AKT1. This could indicate its potential role in lung development via AKT-pathway. Another example is the direct binding of SP-D with microfibrillar-associated protein 4 an extracellular glycoprotein thought to facilitate surfactant homeostasis43,44 in normal physiological condition. Therefore, protein–protein interaction networks provide a wealth of information which could be used to elucidate unknown mechanisms regulating lung development related to mechanical forces.

FIGURE 6.

Protein–protein interaction networks. A protein-protein interaction network was created using a total of 340 proteins those were significantly (1.5-fold, p value < .05) decreased in abundant in OH-induced hypoplastic lungs. Line color indicates the strength of the data support based on the experiments (pink line), co-expression (black line), gene-fusion (red line) and co-occurrence (blue line) according to the STRING (http://string-db.org/). Red rectangular marked proteins were further verified by immunoblot analysis.

In summary, our data revealed significant changes in the expression of a wide variety of proteins as a result of OH-induced pulmonary hypoplasia. Our findings show for the first time that AKT1, SP-D, and CD200 have potential roles in fetal lung development. This investigation also provided a proof-of-concept that one of the potential mechanisms by which mechanical signals are transduced to physiological signals is through the AKT-pathway with specific isoforms having different functions. The information gained from this study will provide the basis for future investigations to test the role of specific molecules and signaling pathways in fetal lung development. Understanding the mechanisms regulating lung development could lead to the development of new therapies to treat pulmonary hypoplasia.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by funding from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health, Number: P30GM114750 and Oh–Zopfi Grant for Perinatal Research, Department of Pediatrics; Kilguss Research Core at Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island.

Funding information

National Institute of General Medical Sciences, Grant/Award Number: P30GM114750; Oh–Zopfi Award for Perinatal Research, Women & Infants Hospital of Rhode Island

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study will be available in Center for Computational Mass Spectrometry at ftp://massive.uscd.edu/MSV000086641/doi10.25345/C5779H from the date of publication. Proteomics data set is submitted in public repository website at massive.uscd.edu. The accession number is MassIVE MSV 000086641.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional Supporting Information may be found online in the supporting information tab for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kitterman JA. The effects of mechanical forces on fetal lung growth. Clin Perinatol. 1996;23(4):727–740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hooper SB, Harding R. Fetal lung liquid: a major determinant of the growth and functional development of the fetal lung. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 1995;22(4):235–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alcorn D, Adamson TM, Lambert TF, Maloney JE, Ritchie BC, Robinson PM. Morphological effects of chronic tracheal ligation and drainage in the fetal lamb lung. J Anat. 1977;123(Pt 3):649–660. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Husain AN, Hessel RG. Neonatal pulmonary hypoplasia: an autopsy study of 25 cases. Pediatr Pathol. 1993;13(4):475–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fliegner JR, Fortune DW, Eggers TR. Premature rupture of the membranes, oligohydramnios and pulmonary hypoplasia. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 1981;21(2):77–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Najrana T, Ramos LM, Abu Eid R, Sanchez-Esteban J. Oligohydramnios compromises lung cells size and interferes with epithelial-endothelial development. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2017;52(6): 746–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thibeault DW, Beatty EC Jr., , Hall RT, Bowen SK, O’Neill DH. Neonatal pulmonary hypoplasia with premature rupture of fetal membranes and oligohydramnios. J Pediatr. 1985;107(2):273–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitterman JA, Chapin CJ, Vanderbilt JN, et al. Effects of oligohydramnios on lung growth and maturation in the fetal rat. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2002;282(3):L431–L439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dickson KA, Harding R. Decline in lung liquid volume and secretion rate during oligohydramnios in fetal sheep. J Appl Physiol. 1989; 67(6):2401–2407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Savich RD, Guerra FA, Lee CC, Padbury JF, Kitterman JA. Effects of acute oligohydramnios on respiratory system of fetal sheep. J Appl Physiol. 1992;73(2):610–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cloutier M, Tremblay M, Piedboeuf B. ROCK2 is involved in accelerated fetal lung development induced by in vivo lung distension. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2010;45(10):966–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CM, Wang LF, Chou HC, Lang YD. Oligohydramnios decreases platelet-derived growth factor expression in fetal rat lungs. Neonatology. 2007;92(3):187–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen CM, Chou HC, Wang LF, Yeh TF. Effects of maternal retinoic acid administration on lung angiogenesis in oligohydramnios-exposed fetal rats. Pediatr Neonatol. 2013;54(2):88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura Y, Fukuda S, Hashimoto T. Pulmonary elastic fibers in normal human development and in pathological conditions. Pediatr Pathol. 1990;10(5):689–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen CM, Chou HC, Wang LF, Lang YD. Experimental oligohydramnios decreases collagen in hypoplastic fetal rat lungs. Exp Biol Med. 2008;233(11):1334–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahsan N, Belmont J, Chen Z, Clifton JG, Salomon AR. Highly reproducible improved label-free quantitative analysis of cellular phosphoproteome by optimization of LC-MS/MS gradient and analytical column construction. J Proteomics. 2017;165:69–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Datta SR, Brunet A, Greenberg ME. Cellular survival: a play in three Akts. Genes Dev. 1999;13(22):2905–2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang J, Ito T, Udaka N, Okudela K, Yazawa T, Kitamura H. PI3K-AKT pathway mediates growth and survival signals during development of fetal mouse lung. Tissue Cell. 2005;37(1):25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hers I, Vincent EE, Tavare JM. Akt signalling in health and disease. Cell Signal. 2011;23(10):1515–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haagsman HP, Diemel RV. Surfactant-associated proteins: functions and structural variation. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2001;129(1):91–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu J, Teh C, Kishore U, Reid KB. Collectins and ficolins: sugar pattern recognition molecules of the mammalian innate immune system. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1572(2-3):387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gorczynski RM. CD200:CD200R-mediated regulation of immunity. ISRN Immunology. 2012;2012:682168-18. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tsai MH, Chu CC, Wei TS, et al. CD200 in growing rat lungs: developmental expression and control by dexamethasone. Cell Tissue Res. 2015;359(3):729–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chandra A, Lan S, Zhu J, Siclari VA, Qin L. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling promotes proliferation and survival in osteoprogenitors by increasing early growth response 2 (EGR2) expression. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(28):20488-20498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shan PF, Lu Y, Cui RR, Jiang Y, Yuan LQ, Liao EY. Apelin attenuates the osteoblastic differentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells. PLoS One. 2011;6(3):e17938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang SY, Xie H, Yuan LQ, et al. Apelin stimulates proliferation and suppresses apoptosis of mouse osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1 via JNK and PI3-K/Akt signaling pathways. Peptides. 2007;28(3): 708–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schittny JC. Development of the lung. Cell Tissue Res. 2017;367(3): 427–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Martinez Calejman C, Jung SM, Li H, Guertin DA. Brown fat organogenesis and maintenance requires AKT1 and AKT2. Mol Metab. 2019;23:60–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.LaRocca J, Pietruska J, Hixon M. Akt1 is essential for postnatal mammary gland development, function, and the expression of Btn1a1. PLoS One. 2011;6(9):e24432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Perez-Gil J, Weaver TE. Pulmonary surfactant pathophysiology: current models and open questions. Physiology. 2010;25(3):132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Botas C, Poulain F, Akiyama J, et al. Altered surfactant homeostasis and alveolar type II cell morphology in mice lacking surfactant protein D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(20): 11869-11874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stahlman MT, Gray ME, Hull WM, Whitsett JA. Immunolocalization of surfactant protein-D (SP-D) in human fetal, newborn, and adult tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 2002;50(5):651–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wright JR. Immunomodulatory functions of surfactant. Physiol Rev. 1997;77(4):931–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barclay AN, Ward HA. Purification and chemical characterisation of membrane glycoproteins from rat thymocytes and brain, recognised by monoclonal antibody MRC OX 2. Eur J Biochem. 1982;129(2): 447–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nie Y, Hu Y, Yu K, et al. Akt1 regulates pulmonary fibrosis via modulating IL-13 expression in macrophages. Innate Immun. 2019; 25(7):451–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crosbie PA, Crosbie EJ, Aspinall-O’Dea M, et al. ERK and AKT phosphorylation status in lung cancer and emphysema using nano-capillary isoelectric focusing. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2016;3(1): e000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshimura K, Suzuki Y, Inoue Y, et al. CD200 and CD200R1 are differentially expressed and have differential prognostic roles in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9(1):1746554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nishikiori H, Chiba H, Ariki S, et al. Distinct compartmentalization of SP-A and SP-D in the vasculature and lungs of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med. 2014;14:196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sorensen GL. Surfactant protein D in respiratory and non-respiratory diseases. Front Med. 2018;5:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piairo P, Moura RS, Baptista MJ, Correia-Pinto J, Nogueira-Silva C. STATs in lung development: distinct early and late expression, growth modulation and signaling dysregulation in congenital diaphragmatic hernia. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;45(1):1–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Campbell CT, Kolesar JE, Kaufman BA. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulates mitochondrial transcription initiation, DNA packaging, and genome copy number. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012; 1819(9-10):921–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Srivillibhuthur M, Warder BN, Toke NH, et al. TFAM is required for maturation of the fetal and adult intestinal epithelium. Dev Biol. 2018;439(2):92–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lausen M, Lynch N, Schlosser A, et al. Microfibril-associated protein 4 is present in lung washings and binds to the collagen region of lung surfactant protein D. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(45):32234-32240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dieterle AM, Böhler P, Keppeler H, et al. PDK1 controls upstream PI3K expression and PIP3 generation. Oncogene. 2014;33(23): 3043–3053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.