Abstract

Background

Preterm infants are at risk of lung atelectasis due to various anatomical and physiological immaturities, placing them at high risk of respiratory failure and associated harms. Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a positive pressure applied to the airways via the nares. It helps prevent atelectasis and supports adequate gas exchange in spontaneously breathing infants. Nasal CPAP is used in the care of preterm infants around the world. Despite its common use, the appropriate pressure levels to apply during nasal CPAP use remain uncertain.

Objectives

To assess the effects of 'low' (≤ 5 cm H2O) versus 'moderate‐high' (> 5 cm H2O) initial nasal CPAP pressure levels in preterm infants receiving CPAP either: 1) for initial respiratory support after birth and neonatal resuscitation or 2) following mechanical ventilation and endotracheal extubation.

Search methods

We ran a comprehensive search on 6 November 2020 in the following databases: CENTRAL via CRS Web and MEDLINE via Ovid. We also searched clinical trials databases and the reference lists of retrieved articles for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomized trials.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs, quasi‐RCTs, cluster‐RCTs and cross‐over RCTs randomizing preterm infants of gestational age < 37 weeks or birth weight < 2500 grams within the first 28 days of life to different nasal CPAP levels.

Data collection and analysis

We used the standard methods of Cochrane Neonatal to collect and analyze data. We used the GRADE approach to assess the certainty of the evidence for the prespecified primary outcomes.

Main results

Eleven trials met inclusion criteria of the review. Four trials were parallel‐group RCTs reporting our prespecified primary or secondary outcomes. Two trials randomized 316 infants to low versus moderate‐high nasal CPAP for initial respiratory support, and two trials randomized 117 infants to low versus moderate‐high nasal CPAP following endotracheal extubation. The remaining seven studies were cross‐over trials reporting short‐term physiological outcomes. The most common potential sources of bias were absent or unclear blinding of personnel and assessors and uncertain selective reporting.

Nasal CPAP for initial respiratory support after birth and neonatal resuscitation

None of the six primary outcomes prespecified for inclusion in the summary of findings was eligible for meta‐analysis. No trials reported on moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 26 months. The remaining five outcomes were reported in a single trial. On the basis of this trial, we are uncertain whether low or moderate‐high nasal CPAP levels improve the outcomes of: death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age (PMA) (risk ratio (RR) 1.02, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.56 to 1.85; 1 trial, 271 participants); mortality by hospital discharge (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.51 to 2.12; 1 trial, 271 participants); BPD at 28 days of age (RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.17; 1 trial, 271 participants); BPD at 36 weeks' PMA (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.57; 1 trial, 271 participants), and treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.57; 1 trial, 271 participants). We assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low for all five outcomes due to risk of bias, a lack of consistency across multiple studies, and imprecise effect estimates.

Nasal CPAP following mechanical ventilation and endotracheal extubation

One of the six primary outcomes prespecified for inclusion in the summary of findings was eligible for meta‐analysis. On the basis of these data, we are uncertain whether low or moderate‐high nasal CPAP levels improve the outcome of treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation (RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.50; 2 trials, 117 participants; I2 = 17%; risk difference 0.15, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.32; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome 7, 95% CI −50 to 3). We assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low due to risk of bias, inconsistency across the studies, and imprecise effect estimates. No trials reported on moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 26 months or BPD at 28 days of age. The remaining three outcomes were reported in a single trial. On the basis of this trial, we are uncertain whether low or moderate‐high nasal CPAP levels improve the outcomes of: death or BPD at 36 weeks' PMA (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.49; 1 trial, 93 participants); mortality by hospital discharge (RR 2.94, 95% CI 0.12 to 70.30; 1 trial, 93 participants), and BPD at 36 weeks' PMA (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.49; 1 trial, 93 participants). We assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low for all three outcomes due to risk of bias, a lack of consistency across multiple studies, and imprecise effect estimates.

Authors' conclusions

There are insufficient data from randomized trials to guide nasal CPAP level selection in preterm infants, whether provided as initial respiratory support or following extubation from invasive mechanical ventilation. We are uncertain as to whether low or moderate‐high nasal CPAP levels improve morbidity and mortality in preterm infants. Well‐designed trials evaluating this important aspect of a commonly used neonatal therapy are needed.

Plain language summary

Nasal continuous positive airway pressure levels for the prevention of morbidity and mortality in preterm infants

Review question

How does giving preterm infants low versus moderate‐high levels of nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) impact important health outcomes?

Background

Preterm infants are born earlier than expected. Compared to term infants, preterm infants have immature lungs that are at risk of partial collapse. This collapse makes it difficult for the lungs to bring oxygen into the body and remove carbon dioxide from the body. In response, such infants are commonly treated with nasal CPAP, a therapy that maintains a positive pressure against the airways in an effort to keep the lungs open and to prevent respiratory failure. The pressure is applied through a mask or prongs attached to the nose. Nasal CPAP may be used upon admission to the neonatal intensive care unit as the initial respiratory support and also after a period of mechanical ventilation (use of a breathing machine) and extubation (removal of a breathing tube). Medical providers choose how much pressure to give. The amount of pressure is referred to as the CPAP level, which is measured in units of centimeters of water (cm H2O). Both not enough and too much pressure can be harmful, and it remains uncertain which CPAP pressure levels lead to the best outcomes. We performed a comprehensive search of the medical literature to summarize the impact of using low (≤ 5 cm H2O) versus moderate‐high (> 5 cm H2O) initial CPAP pressure levels in preterm infants.

Study characteristics

The search is up‐to‐date through 6 November 2020. We included 11 studies in the review. Four studies reported health outcomes that we had pre‐selected as being relevant to nasal CPAP levels and to the overall health of preterm infants, while the remaining studies reported short‐term physiological outcomes such as oxygen levels, heart rate, and blood pressure.

Key results

Of the four studies reporting pre‐selected health outcomes, we could only combine data from two studies comparing nasal CPAP levels for initial respiratory support and two studies comparing levels for support following extubation. Based on the data from these studies, we are uncertain as to whether low or moderate‐high nasal CPAP levels improve these outcomes. Future studies are needed to answer our review question.

Certainty of evidence

The overall numbers of studies and participants were small, and some of the included studies had flaws potentially limiting the accuracy of their findings. We therefore judged our findings as of very low certainty.

Summary of findings

Background

Description of the condition

Preterm infants are born with lungs prone to atelectasis (Gregory 1971). This results from several anatomical and physiological factors. Immature neurological control leads to periodic breathing and central apnea (Martin 1977). A compliant chest wall and the relative shape and position of the diaphragm, ribs, and chest wall contribute to inefficient respiratory mechanics, requiring additional work to inflate the lungs and maintain them open (Muller 1979). The supraglottic airway is unstable and prone to obstruction (Miller 1990). The quantity and quality of endogenous surfactant is decreased (Ueda 1994). These factors among others contribute to inadequate pulmonary gas exchange. Respiratory failure is the extreme result of this pathophysiology and is a leading cause of neonatal death (Patel 2015). In turn, the interventions used to treat poor gas exchange, such as supplemental oxygen and mechanical ventilation (MV), can injure the lung and contribute to important neonatal morbidities, such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), and retinopathy of prematurity (ROP).

Description of the intervention

Nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a positive pressure applied to the airways via the nares without an endotracheal tube. This provides a continuous distending airway pressure throughout the respiratory cycle in spontaneously breathing infants. Nasal CPAP is a common mode of non‐invasive respiratory support in preterm infants, applied as either initial respiratory support after birth and neonatal resuscitation or as postextubation support following a period of MV. Providers choose how much CPAP pressure to apply, which is typically measured in centimeters of water (cm H2O). We focused on the impact of different pressure levels in this review.

How the intervention might work

Nasal CPAP provides a continuous distending airway pressure to help offset atelectasis and inadequate gas exchange in preterm infants (Gregory 1971; Martin 1977; Miller 1990). Evidence for CPAP benefit compared to supplemental oxygen alone is established (Davis 2003; Ho 2015). However, it is uncertain how much pressure should be used. While higher levels may increase lung volumes and improve respiratory mechanics and gas exchange in under‐recruited lungs, excessive distending pressures may directly impair gas exchange and worsen respiratory mechanics and cardiovascular performance through overdistension (Abdel‐Hady 2008; Milner 1977). Furthermore, overdistension may contribute to air leak syndromes and facilitate volutrauma, a leading mechanism of lung injury contributing to BPD (Morley 2008; Wheeler 2011). A stratified analysis of the Cochrane Review on nasal CPAP versus headbox oxygen following extubation by pressure levels of < 5 cm H2O or ≥ 5 cm H2O suggests that higher pressures may be more effective in this setting (Davis 2003), but does not focus on studies directly comparing different pressure levels. Large, multicenter trials that compared nasal CPAP to MV used pressure levels as disparate as 4 cm H2O to 8 cm H2O (Göpel 2011; Morley 2008). Approaches to setting a CPAP level include choosing a single consistent pressure level for all preterm infants or an individualized approach. The latter usually selects an initial pressure level with subsequent pressure level titrations guided by clinical observations such as measures of gas exchange, work of breathing, and radiographic lung expansion.

Why it is important to do this review

Systematic reviews comparing the preferential use of non‐invasive respiratory support strategies such as nasal CPAP for initial respiratory support instead of MV in preterm infants favor CPAP for the outcome of survival without BPD (Fischer 2013; Schmölzer 2013). This is likely mediated by avoiding MV and ventilator‐induced lung injury. However, the magnitude of the benefit is modest, with a number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome of 25 to 35 and confidence intervals approaching no effect. This may be explained by high CPAP failure rates, observed in 46% to 83% of preterm infants randomized to preferential CPAP (Morley 2008; SUPPORT 2010). Likewise, non‐invasive respiratory support failure is common when used after extubation (Danan 2008). Evidence‐based guidance on specific key aspects of non‐invasive respiratory support may further enhance its benefit. Existing Cochrane Reviews have compared non‐invasive respiratory support modes (nasal CPAP versus nasal intermittent positive pressure ventilation (NIPPV) (Lemyre 2016; Lemyre 2017), as well as differing nasal CPAP devices and pressure sources (De Paoli 2008). This Cochrane Review considers how much pressure should be used by identifying and analyzing trials that compare different nasal CPAP levels.

Objectives

To assess the effects of 'low' (≤ 5 cm H2O) versus 'moderate‐high' (> 5 cm H2O) initial nasal CPAP pressure levels in preterm infants receiving CPAP either: 1) for initial respiratory support after birth and neonatal resuscitation or 2) following MV and endotracheal extubation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐RCTs, cluster‐RCTs, and cross‐over trials with random nasal continuous positive airway pressure (NCPAP) level sequence allocation. We excluded studies completed prior to 1990 to increase the applicability of findings to modern neonatal practice, recognizing the now common use of antenatal corticosteroids, surfactants, and gentler ventilation strategies.

Types of participants

We included preterm infants of gestational age < 37 weeks or birth weight < 2500 grams randomized within the first 28 days of life. We included studies in which some but not all infants met these demographic criteria if the central tendency of enrolled infants (e.g. mean gestational age, median age at study) satisfied our inclusion criteria.

Types of interventions

We included trials comparing:

two or more different nasal CPAP levels for initial respiratory support after birth and neonatal resuscitation; or

two or more different nasal CPAP levels following mechanical ventilation and endotracheal extubation.

For the purposes of data synthesis, these two indications were considered separately.

We excluded trials in which the intervention was initiated during neonatal resuscitation. We compared interventions as 'low' (≤ 5 cm H2O) versus 'moderate‐high' (> 5 cm H2O) pressure levels. This dichotomy is arbitrary but acknowledges the common use of a pressure level of 5 cm H2O for initial support. For trials that evaluated more than two randomly allocated nasal CPAP levels, these were collapsed into either 'low' or 'moderate‐high' classifications. For example, in a hypothetical three‐arm trial comparing levels of 4 cm H2O versus 6 cm H2O versus 8 cm H2O, we would combine 6 cm H2O and 8 cm H2O as 'moderate‐high' and compare to 4 cm H2O as 'low'. We also planned a sensitivity analysis replacing 5 cm H2O with 8 cm H2O as the dichotomizing value, thereby comparing 'low‐moderate' (≤ 8 cm H2O) versus 'high' (> 8 cm H2O) pressure levels. We excluded trials that compared CPAP levels inconsistent with either dichotomy. For example, a trial comparing 6 cm H2O versus 8 cm H2O would be classified as 'moderate‐high' versus 'moderate‐high' in the primary comparison and as 'low‐moderate' versus 'low‐moderate' in the sensitivity analysis, and would be excluded.

We used the initial nasal CPAP pressure level following randomization for the comparisons above. This acknowledges that selection of an initial pressure level with subsequent titrations is common in clinical practice and may be applied to clinical research protocols.

Types of outcome measures

We included trials reporting at least one of our prespecified primary or secondary outcomes. The following outcome measures apply to both initial and postextubation respiratory support comparisons.

Primary outcomes

Death or BPD at 36 weeks' postmenstrual age (PMA); we defined BPD as supplemental oxygen or positive pressure support use at 36 weeks' PMA (for infants less than 32 weeks' gestational age) (Jobe 2001; Shennan 1988).

Mortality at 28 days, hospital discharge, and one year.

Moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 26 months and at 3 to 5 years. We defined moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment as: cerebral palsy or gross motor disability (defined as ≥ level 2 according to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS)) (Palisano 1997); developmental delay (Bayley or Griffith assessment > 2 standard deviations (SD) below the mean) (Bayley 1993; Bayley 2006; Griffiths 1954) or intellectual impairment (intelligent quotient (IQ) > 2 SD below the mean); blindness (vision < 6/60 in both eyes); or sensorineural deafness requiring amplification. We planned to perform separate analyses for children aged 18 to 26 months and 3 to 5 years (Jacobs 2013).

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, defined as supplemental oxygen use at 28 days of age (NIH 1979).

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia, defined as supplemental oxygen or positive pressure support use at 36 weeks' PMA (for infants less than 32 weeks' gestational age) (Jobe 2001; Shennan 1988).

Treatment failure as indicated by study author prespecified values of recurrent apnea, hypoxia, hypercarbia, increasing oxygen requirement; or the need for mechanical ventilation. If this outcome was reported for more than one time point (e.g. failure by three days, failure by five days, etc.), we used the latest time point up to seven days from randomization.

Need for mechanical ventilation.

We included the first six outcomes in the summary of findings table; we selected mortality at discharge and neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 26 months as the time points for inclusion in the summary of findings table from the three time points prespecified for these outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

-

Components of moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment:

cerebral palsy or gross motor disability (defined as ≥ level 2 according to the GMFCS) (Palisano 1997);

developmental delay (Bayley or Griffith assessment > 2 SD below the mean) (Bayley 1993; Bayley 2006; Griffiths 1954) or intellectual impairment (IQ > 2 SD below the mean);

blindness (vision < 6/60 in both eyes);

sensorineural deafness requiring amplification.

Severe intraventricular hemorrhage (Papile grade III or IV) (Papile 1978).

Periventricular leukomalacia (de Vries 1992).

Severe retinopathy of prematurity (International Classification of Retinopathy of Prematurity (ICROP) stage III to V) (ICROP 2005).

Necrotizing enterocolitis requiring surgery.

Pneumothorax.

Pulmonary air leak (any air leak, including pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, pulmonary interstitial emphysema, pneumopericardium).

Rate of apnea and bradycardia expressed as events per hour.

Patent ductus arteriosus receiving medical or surgical treatment.

Necrotizing enterocolitis (Bell stage 2 or greater) (Bell 1978).

Intraventricular hemorrhage (any) (Papile grade I to IV) (Papile 1978).

Physiological definition of BPD (Walsh 2004).

Severe BPD, defined as the need for ≥ 30% oxygen or positive pressure at 36 weeks’ PMA, or both (Ehrenkranz 2005; Jobe 2001).

Any retinopathy of prematurity (ICROP stage I to V).

Duration of positive pressure ventilation (days).

Duration of oxygen supplementation (days).

Length of hospital stay (days).

Days to establish full feeding (enteral, oral, breast).

Days to regain birth weight.

Weight gain (gram/day) at discharge.

Weight z score (g/kg/day) at discharge.

Growth failure (weight < 10th percentile for the index population measured) at discharge.

Nasal injury as defined by study including hyperemia, septal injury, septal necrosis, scarring.

Gastrointestinal perforation.

Short‐term physiologic measures

Measures of oxygenation, such as fraction of inspired oxygen needed to maintain oxygen saturation targets or alveolar to arterial gradients.

Carbon dioxide values, including venous, capillary, arterial, or transcutaneous measures.

Direct or surrogate measures of cardiac output, including echocardiography.

Heart rate in beats per minute.

Systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure in mmHg.

Lung volume measurements such as tidal volume or functional residual capacity.

We summarized physiologic outcomes in tabular form without meta‐analysis due to substantial heterogeneity in definitions, baseline values, and units of measure. We limited eligible outcomes from cross‐over trials to the physiological measures described above. When studies reported repeated measures over time, we used the measure farthest from the intervention, as long as we judged it to plausibly reflect the impact of the pressure level change.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We conducted a search in November 6, 2020 including: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; 2020, Issue 11) in the Cochrane Library and Ovid MEDLINE and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions (1946 to 6 November 2020). We have included the search strategies for each database in Appendix 1. We did not apply any language restrictions.

We searched the following clinical trial registries for ongoing or recently completed trials via CENTRAL: World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/) and ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov). We also searched the ISRCTN registry (http://www.isrctn.com/) for any unique trials not found through our search of CENTRAL.

This is the second update of this search strategy. Previous search details are listed in Appendix 2.

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of studies included in the review to identify additional relevant articles. We additionally used the review authors' existing knowledge of studies on the review topic to identify potentially relevant studies missed by the search.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

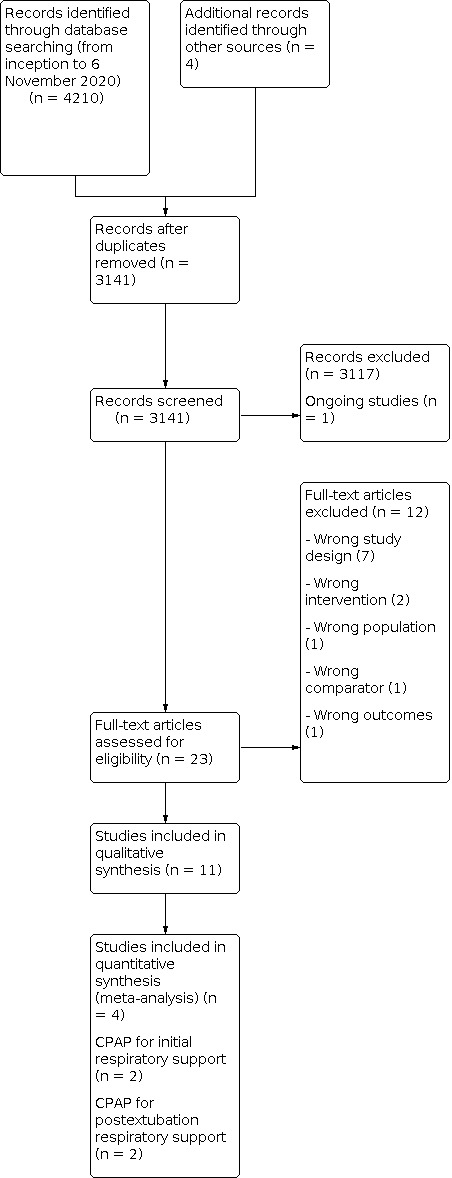

We exported the records of the electronic database searches to Covidence to facilitate title and abstract screening. We ensured the single inclusion of duplicate data from the same study identified in multiple reports. Two review authors (NB, JF or AM) independently performed title and abstract screening of the search results, excluding any irrelevant studies. We obtained the full‐text articles of potentially relevant studies when available. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion between review authors. We listed all studies excluded after full‐text assessment and the reasons for their exclusion in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. We illustrated the study selection process in a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram.

Data extraction and management

We developed a standardized data extraction form to help guide determination of eligibility, study characterization, and data extraction. Two review authors (NB and AM) reviewed the full texts of eligible studies in duplicate. One review author (NB) transcribed data and study details into Review Manager Web (RevMan Web 2019), which a second review author (AM) independently reviewed and verified; any disagreements between review authors were reconciled through discussion or by consulting a third review author (JF) when necessary.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (NB and AM) independently assessed the risk of bias (low, high, or unclear) of all included trials using the Cochrane risk of bias tool for the following domains (Higgins 2011):

sequence generation (selection bias);

allocation concealment (selection bias);

blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias);

blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias);

incomplete outcome data (attrition bias);

selective reporting (reporting bias);

any other bias.

We assessed individual trials as having a high overall risk of bias if the number of domains at high risk of bias were greater than those at low risk of bias. This determination was relevant to the sensitivity analyses described below.

Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third review author (JF) when necessary. For a more detailed description of risk of bias for each domain, see Appendix 3.

Measures of treatment effect

For continuous data, we presented treatment effects as the mean difference (MD) or standardized mean difference (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for individual studies and pooled estimates, using an inverse‐variance fixed‐effect approach for meta‐analysis. For outcomes reported as median and interquartile range, we substituted the median for the mean, and derived the median from the interquartile range by dividing the latter by 1.35, as per the methods described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2021), while noting this approximation within the analysis footnote.

For dichotomous categorical data, we presented treatment effect as risk ratio (RR), risk difference (RD), and number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) or number needed to treat for an additional harmful outcome (NNTH) with 95% CIs for pooled estimates for all primary outcomes and statistically significant secondary outcomes. We used a Mantel‐Haenszel fixed‐effect approach for meta‐analysis.

For continuous data reflecting short‐term physiologic outcomes, we summarized the data presented in each study in tabular form, using the study's summary measures of central tendency (e.g. mean, median, etc.) and variance (e.g. SD, interquartile range, etc.) We did not pursue meta‐analysis for these outcomes, as discussed above (Secondary outcomes).

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participating infant in individually randomized trials, and an infant was considered only once in each meta‐analysis for all primary and secondary outcomes. Data from cross‐over trials in which an infant contributed multiple observations to an outcome (up to once per cross‐over period) were not restricted to the first cross‐over period, but summarized in aggregate across the study cohort by nasal CPAP level in tabular form and considered in the qualitative synthesis of the review only.

The participating neonatal unit or section of a neonatal unit or hospital was the planned unit of analysis in cluster‐randomized trials; however, none of these have been identified to date. We planned to analyze such trials using an estimate of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) derived from the trial (if possible) or from a similar trial or from a study with a similar population as described in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2021). We planned that if we used ICCs from a similar trial or from a study with a similar population, we would report this and conduct a sensitivity analysis to investigate the effect of variation in the ICC.

In the future, if we identify both cluster‐randomized trials and individually randomized trials, we will only combine the results from both if there is little heterogeneity between the study designs, and interaction between the effect of the intervention and the choice of randomization unit is considered to be unlikely. We will acknowledge any possible heterogeneity in the randomization unit and perform a sensitivity analysis to investigate possible effects of the randomization unit.

Dealing with missing data

When feasible, we carried out analyses on an intention‐to‐treat basis for all outcomes. To the greatest degree possible, we analyzed all participants in the treatment group to which they had been randomized, regardless of the actual treatment received. Assumptions made to deal with missing data were described within the specific analysis. We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to assess the consistency of results to reasonable changes in the underlying assumptions. When applicable, we addressed the potential impact of missing data on the findings in the Discussion.

Assessment of heterogeneity

The Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity section outlines the steps taken to limit aggregation and meta‐analysis of data at risk of excess heterogeneity and to facilitate assessment of heterogeneity within the overall results. When we pursued meta‐analyses, we performed posterior assessments of heterogeneity through identification of studies contributing ‘outlying’ effect estimates through visual inspection of forest plots. We assessed these studies for unanticipated clinical and methodological characteristics plausibly explaining the observed heterogeneity. Identification of such characteristics did not result in exclusion from the pooled estimates of the primary analysis, but in exclusion from a secondary sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). We quantified the degree of heterogeneity by applying the I² statistic together with a Chi² test as a measure of corresponding statistical significance, using a conservative P value of 0.10 for statistical significance. We used the following I² statistic thresholds as a guide to help interpret the degree of heterogeneity:

25%: none;

25% to 49%: low;

50% to 74%: moderate;

75% to 100%: high.

Assessment of reporting biases

We assessed reporting bias by comparing the stated outcomes and the reported outcomes. When study protocols were available, we compared intended and reported outcomes to determine the likelihood of reporting bias. We planned to use funnel plots to screen for publication bias when there were at least 10 studies for an outcome. We considered suggestion of publication bias by significant asymmetry of the funnel plot on visual assessment in our assessment of the certainty of the evidence.

Data synthesis

When we identified multiple studies considered to be sufficiently similar, we performed meta‐analysis using Review Manager Web (RevMan Web 2019), reporting measures of treatment effects as described in Measures of treatment effect. We used fixed‐effect models given our assumption that studies were estimating the same underlying treatment effect. When we judged meta‐analysis to be inappropriate, we analyzed and interpreted trials separately.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We used a cautious approach to aggregation and meta‐analysis of data at risk of excess heterogeneity, erring on the side of avoidance when uncertainty existed. Two review authors (NB and JF) independently made this decision, resolving any disagreements through discussion or resolution by a third review author (AM). We planned to further assess heterogeneity by the a priori application of several subgroup analyses stratified on key clinical characteristics. We included study data in the subgroup analysis when all infants met the criteria, unless otherwise specified.

Planned subgroups analyses

For both comparisons (as specified in Types of interventions) we planned subgroup analyses for all primary outcomes stratified on the basis of the following.

-

Gestational age groups:

Late preterm infants, defined as infants 34 to 36 completed weeks' gestational age

Moderate preterm infants, defined as infants born at 32 to 33 completed weeks' gestational age

Very preterm infants, defined as infants born at 28 to 31 completed weeks' gestational age

Extremely preterm infants, defined as infants born at less than 28 completed weeks' gestational age

-

Birth weight groups:

Low birth weight (LBW) infants, defined as infants with birth weight < 2500 grams

Very low birth weight (VLBW) infants, defined as infants with birth weight < 1500 grams

Extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infants, defined as infants with birth weight < 1000 grams

-

Setting:

Low‐ and middle‐income countries, as defined by the World Bank List of Country Economies (World Bank 2021)

High‐income countries

Mixed or not reported

-

Type of CPAP pressure generation:

Underwater bubble CPAP

CPAP delivered by ventilator

CPAP delivered by variable flow device

Mixed or not reported

-

Type of CPAP delivery interface:

Short single prong

Short binasal (double) prongs

Long (nasopharyngeal) prongs

Mask

RAM cannula

Mixed or not reported

-

Antenatal steroid exposure, as baseline characteristic:

Yes, if ≥ 50% of infants were treated with any corticosteroid

No, if < 50% of infants were treated with any corticosteroid

Unknown

-

Methylxanthine exposure, as baseline characteristic:

Yes, if ≥ 50% of infants were treated with any methylxanthine

No, if < 50% of infants were treated with any methylxanthine

Unknown

Sensitivity analysis

For all primary outcomes, we planned the following sensitivity analyses:

excluding studies assessed as at overall high risk of bias;

excluding studies contributing 'outlying effect' estimates, as described in Assessment of heterogeneity;

considering 8 cm H2O as the threshold for CPAP level comparisons, i.e. 'low‐moderate' (≤ 8 cm H2O) versus 'high' (> 8 cm H2O).

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach, as outlined in the GRADE Handbook (Schünemann 2013), to assess the certainty of evidence for the first six primary outcomes listed above (Primary outcomes). Two review authors (NB and JF) independently assessed the certainty of the evidence for each outcome. We considered evidence from RCTs as high certainty, downgrading the certainty of the evidence one level for serious (or two levels for very serious) limitations based upon the following: design (risk of bias), consistency across studies, directness of the evidence, precision of estimates, and presence of publication bias. We used GRADEpro GDT to create summary of findings tables (Table 1; Table 2) to report the certainty of the evidence (GRADEpro GDT).

Summary of findings 1. Summary of Findings Table ‐ Low compared to moderate‐high nasal continuous positive airway pressure levels for preterm infants receiving initial respiratory support.

| Low compared to moderate‐high nasal continuous positive airway pressure levels for preterm infants receiving initial respiratory support | ||||||

| Patient or population: health problem or population Setting: Intervention: Low Comparison: Moderate‐High | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Moderate‐High | Risk with Low | |||||

| Death or BPD at 36 weeks PMA | 135 per 1000 | 138 per 1000 (76 to 250) | RR 1.02 (0.56 to 1.85) | 271 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a | |

| Mortality, by hospital discharge | 98 per 1000 | 102 per 1000 (50 to 207) | RR 1.04 (0.51 to 2.12) | 271 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a | |

| Moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 26 months ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen use at 28 days of age | 105 per 1000 | 116 per 1000 (59 to 228) | RR 1.10 (0.56 to 2.17) | 271 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a | |

| BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen or positive pressure support use at 36 weeks PMA | 45 per 1000 | 36 per 1000 (11 to 116) | RR 0.80 (0.25 to 2.57) | 271 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a | |

| Treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation | 218 per 1000 | 218 per 1000 (137 to 342) | RR 1.00 (0.63 to 1.57) | 271 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_425006380464097721. | ||||||

a. Downgraded one level for serious limitations based on: risk of bias (high risk of performance bias, unclear risk of detection and reporting bias); one level for consistency across studies (single study); and one level for precision of estimates (single study with 271 participants).

Summary of findings 2. Summary of Findings Table ‐ Low compared to moderate‐high nasal continuous positive airway pressure levels for preterm infants receiving postextubation respiratory support.

| Low compared to moderate‐high nasal continuous positive airway pressure levels for preterm infants receiving postextubation respiratory support | ||||||

| Patient or population: health problem or population Setting: Intervention: Low Comparison: Moderate‐high | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with Moderate‐high | Risk with Low | |||||

| Death or BPD at 36 weeks' PMA | 391 per 1000 | 340 per 1000 (200 to 583) | RR 0.87 (0.51 to 1.49) | 93 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a | |

| Mortality, by hospital discharge | 0 per 1000 | 0 per 1000 (0 to 0) | RR 2.94 (0.12 to 70.30) | 93 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a | |

| Moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 26 months ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen use at 28 days of age ‐ not measured | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | |

| BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen or positive pressure support use at 36 weeks' PMA | 391 per 1000 | 340 per 1000 (200 to 583) | RR 0.87 (0.51 to 1.49) | 93 (1 RCT) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW a | |

| Treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation | 288 per 1000 | 438 per 1000 (265 to 720) | RR 1.52 (0.92 to 2.50) | 117 (2 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW b | |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; RR: Risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect | ||||||

| See interactive version of this table: https://gdt.gradepro.org/presentations/#/isof/isof_question_revman_web_425006643542116952. | ||||||

a. Downgraded one level for serious limitations based on risk of bias (high risk of performance bias, unclear risk of detection and reporting bias); one level for consistency across studies (single study); and one level for precision of estimates (single study with 93 participants). b. Downgraded one level for serious limitations based on risk of bias (high risk of performance bias, unclear risk of detection and reporting bias); one level for consistency across studies (overall inconsistent estimates); and one level for precision of estimates (two studies with 117 participants).

The GRADE approach results in an assessment of the certainty of a body of evidence into one of four grades.

High: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect.

Moderate: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different.

Low: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect.

Very low: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect.

Results

Description of studies

The search results and study identification process are displayed in Figure 1.

Results of the search

From 3141 records retrieved by the search, our screening identified one ongoing study, ACTRN12618001638224, and 23 completed studies for potential inclusion in the review. Following full‐text review, we included 11 studies and excluded 12 studies.

Included studies

See: Characteristics of included studies.

We included 11 trials published between 2001 and 2016. Four trials were two‐arm, parallel‐group RCTs: Murki 2016 and Dhir 2016 compared CPAP levels for initial respiratory support, while Buzzella 2014 and Kitsommart 2013 compared CPAP levels for postextubation support. The remaining seven studies were cross‐over trials with random CPAP level sequence allocation: Lavizzari 2014 enrolled infants on CPAP for initial respiratory support; Magnenant 2004 for postextubation support; and five studies enrolled a mix of the two populations (Beker 2014; Elgellab 2001 Lomp 2010; Miedema 2013; Rehan 2001). Beker 2014, Lomp 2010, and Miedema 2013 predominantly enrolled infants on CPAP for initial respiratory support. Elgellab 2001 and Rehan 2001 predominantly enrolled infants on CPAP following extubation. All of the included studies were performed at a single center. Three studies were conducted in low‐/middle‐income country settings (Dhir 2016, Lomp 2010; Murki 2016), while the remaining eight studies were conducted in high‐income country settings.

Population

The four parallel‐group RCTs enrolled between 24 and 271 infants; only Murki 2016 enrolled over 100 infants. The cross‐over trials contributed 37 infants, in Lomp 2010, or fewer.

Most studies enrolled a broad population of preterm neonates, with all studies including multiple prespecified gestational age or birth weight subgroup categories, except Buzzella 2014, who restricted enrollment to ELBW infants.

In 6 of the 11 studies, half or more infants received antenatal corticosteroids. This information was not provided for the remaining five studies. Only Buzzella 2014 described methylxanthine use in greater than half of infants. Less than 50% of infants were exposed to methylxanthines at baseline in Murki 2016. The remaining nine studies did not describe present or absent methylxanthine use.

Interventions

All four parallel‐group RCTs compared 'low' (≤ 5 cm H2O) versus 'moderate‐high' (> 5 cm H2O) initial nasal CPAP levels. For CPAP as initial respiratory support, both Murki 2016 and Dhir 2016 compared 5 cm H2O versus 7 cm H2O. For postextubation support, both Buzzella 2014 and Kitsommart 2013 compared CPAP levels of 5 cm H2O versus 8 cm H2O. A broader number and range of CPAP levels were evaluated in the included cross‐over trials (Table 3). Four studies evaluated three distinct CPAP levels (Beker 2014; Lavizzari 2014; Miedema 2013; Rehan 2001), while Elgellab 2001, Lomp 2010, and Magnenant 2004 evaluated four levels. The range of CPAP levels evaluated across all included studies was 0 cm H2O, Magnenant 2004, to 8 cm H2O (Beker 2014; Elgellab 2001; Lomp 2010; Rehan 2001). The broadest within‐study ranges were reported by Magnenant 2004 (0 to 6 cm H2O) and Lomp 2010 and Elgellab 2001 (both 2 to 8 cm H2O).

1. Impact of nasal CPAP levels on short‐term physiologic measures.

| Outcome | Study, type | Respiratory support |

Initial CPAP level (cm H2O) |

||||||

| 0 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | |||

| Oxygenation measures | |||||||||

| Maximal FiO2 during intervention, median (IQR) | Murki 2016, RCT | Initial | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

n = 138 0.40 (40 to 44) |

‐ |

n = 133 0.40 (40 to 40) |

‐ |

| Maximal FiO2 during intervention, mean (SD) | Kitsommart 2013, RCT | Postextubation | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ | n = 11 0.33 (0.12) | ‐ | ‐ | n = 13 0.42 (0.16) |

| Maximal FiO2 during cross‐over period, mean (SD) | Lavizzari 2014, cross‐over RCT | Initial | ‐ |

n = 3 0.22 (1.2) |

n = 2 0.21 (0) |

‐ |

n = 2 0.21 (0) |

‐ | ‐ |

| FiO2 during cross‐over period, mean (SD) | Lomp 2010, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ |

n = 37 0.25 (0.7) |

n = 37 0.23 (0.5) |

‐ |

n = 36 0.23 (0.5) |

‐ |

n = 33 0.23 (0.5) |

| Peripheral oxygen saturations, mean (SD) | Rehan 2001, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most postextubation | ‐ |

n = 12 91 (2.5) |

‐ |

n = 12 95 (2.3) |

‐ | ‐ |

n = 12 98 (2.2) |

| Transcutaneous partial oxygen pressure, in kPa, mean (SD) | Miedema 2013, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ |

n = 22 7.2 (1.7) |

n = 22 8.2 (1.9) |

‐ |

n = 22 8.9 (2.0) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Transcutaneous partial oxygen pressure, in mmHg, mean (SD) |

Magnenant 2004, cross‐over RCT |

Postextubation | n = 11 36 (4) |

n = 11 40 (3) |

n = 11 39 (3) |

‐ |

n = 11 42 (4) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Transcutaneous partial oxygen pressure divided by FiO2, in mmHg, mean (SD) |

Magnenant 2004 cross‐over RCT |

Postextubation |

n = 11 134 (15) |

n = 11 154 (14) |

n = 11 163 (14) |

‐ |

n = 11 175 (17) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Carbon dioxide measures | |||||||||

| Transcutaneous partial carbon dioxide pressure, in kPa, mean (SD) |

Miedema 2013, cross‐over RCT |

Mixed, most initial | ‐ |

n = 22 6.4 (0.8) |

n = 22 6.4 (0.8) |

‐ |

n = 22 6.3 (0.8) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Transcutaneous partial carbon dioxide pressures, in mmHg, mean (SD) | Lavizzari 2014, cross‐over RCT | Initial support | ‐ |

n = 3 40.7 (3.5) |

n = 2 45.5 (3.5) |

‐ |

n = 2 37.5 (7.8) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Transcutaneous partial carbon dioxide pressures, in mmHg, mean (SD) | Magnenant 2004, cross‐over RCT | Postextubation |

n = 11 62 (3) |

n = 11 62 (4) |

n = 11 59 (3) |

‐ |

n = 11 62 (5) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Cardiac output measures | |||||||||

| Left ventricular output, as measured on echocardiography, in mL/kg/min, mean (SD) | Beker 2014, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ | ‐ |

n = 34 286 (101) |

‐ |

n = 34 283 (83) |

‐ |

n = 282 (88) |

| Right ventricular output, as measured on echocardiography, in mL/kg/min, mean (SD) | Beker 2014, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ | ‐ |

n = 34 294 (94) |

‐ |

n = 34 301 (106) |

‐ |

n = 34 294 (92) |

| Heart rate measures | |||||||||

| Heart rate, beats per minute, mean (SD) | Lavizzari 2014, cross‐over RCT | Initial support | ‐ |

n = 3 148 (13.1) |

n = 2 128 (6.4) |

‐ |

n = 2 137 (2.8) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Heart rate, beats per minute, mean (SD) | Rehan 2001, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most postextubation | ‐ |

n = 12 157 (20) |

‐ |

n = 12 150 (16) |

‐ | ‐ |

n = 12 156 (17) |

| Heart rate, beats per minute, mean (SD) | Beker 2014, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ | ‐ |

n = 34 150 (13) |

‐ |

n = 34 148 (13) |

‐ |

n = 34 151 (14) |

| Heart rate, beats per minute, mean (SD) | Lomp 2010, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ |

n = 37 149 (19) |

n = 37 149 (17) |

‐ |

n = 37 150 (19) |

‐ |

n = 37 148 (18) |

| Heart rate, beats per minute, mean (SD) | Magnenant 2004 cross‐over RCT | Postextubation |

n = 11 149 (5) |

n = 11 147 (6) |

n = 11 147 (5) |

‐ |

n = 11 150 (5) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Blood pressure measures | |||||||||

| Systolic, via cuff, mmHg, mean (SD) | Beker 20144, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ | ‐ |

n = 34 64 (11) |

‐ |

n = 34 63 (10) |

‐ |

n = 34 62 (9) |

| Diastolic, via cuff, mmHg, mean (SD) | Beker 2014 cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ | ‐ |

n = 34 38 (7) |

‐ |

n = 34 39 (9) |

‐ |

n = 34 39 (8) |

| Mean, via cuff, mmHg, mean (SD) | Beker 2014, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most initial | ‐ | ‐ |

n = 34 47 (7) |

‐ |

n = 34 47 (9) |

‐ |

n = 34 47 (7) |

| Mean, arterial, mmHg, mean (SD) | Magnenant 2004, cross‐over RCT | Postextubation |

n = 11 46 (2) |

n = 11 44 (3) |

n = 11 47 (2) |

‐ |

n = 11 47 (3) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Lung volume measures | |||||||||

| Tidal volume, measured by respiratory inductance plethysmography, mL, mean (SD) | Lavizzari 2014, cross‐over RCT | Initial support | ‐ |

n = 3 4.3 (1.9) |

n = 2 7.1 (2.1) |

‐ |

n = 2 5.7 (4.6) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Tidal volume, measured by respiratory inductance plethysmography, and reported as % of tidal volume obtained at CPAP 0 cm H2O, i.e. 100% = tidal volume at 0 cm H2O | Elgellab 2001, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most postextubation | ‐ |

n = 10 104 (10) |

n = 10 110 (18) |

‐ |

n = 10 125 (20) |

‐ |

n = ? 143 (24) |

| Tidal volume, measured by respiratory inductance plethysmography, and reported as % of tidal volume obtained at CPAP 0 cm H2O, i.e. 100% = tidal volume at 0 cm H2O | Magnenant 2004, cross‐over RCT | Postextubation |

n = 11 100 (0) |

n = 11 108 (5) |

n = 11 122 (9) |

‐ |

n = 11 146 (15) |

‐ | ‐ |

| Change in end‐expiratory lung volume, measured by respiratory inductance plethysmography, calculated as the difference in end‐expiratory lung volume compared to CPAP 0 cm H2O and reported as % of tidal volume obtain at CPAP 0 cm H2O, i.e. 100% = change in volume equivalent to tidal volume at 0 cm H2O | Elgellab 2001, cross‐over RCT | Mixed, most postextubation | ‐ |

n = 10 38 (25) |

n = 10 110 (46) |

‐ |

n = 10 135 (49) |

‐ |

n = ? 210 (37) |

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure;FiO2: fraction of inspired oxygen; IQR: interquartile range;RCT: randomized controlled trial;SD: standard deviation

The following pressure generation devices were used: bubble CPAP (Murki 2016), ventilators (Buzzella 2014; Kitsommart 2013), variable flow devices (Elgellab 2001; Lavizzari 2014; Lomp 2010; Magnenant 2004; Miedema 2013), and either bubble CPAP or ventilators (Beker 2014). Two studies did not detail pressure generation (Dhir 2016; Rehan 2001). All studies describing CPAP interfaces used short binasal prongs, but the interface was not described in 4 of the 11 studies (Dhir 2016; Elgellab 2001; Magnenant 2004; Miedema 2013).

All cross‐over trials reported the duration over which each pressure level was maintained prior to obtaining measures, with a range of 10, Lomp 2010; Miedema 2013; Rehan 2001, to 30 minutes (Elgellab 2001; Magnenant 2004). No study described a wash‐out period in which CPAP levels were returned to a baseline or reference value for a period of time between assessed CPAP levels.

Outcomes

In the two parallel‐group RCTs comparing CPAP levels for initial respiratory support, review primary outcomes reported by the studies were: death or BPD at 36 weeks' PMA (Murki 2016), mortality by hospital discharge (Murki 2016), BPD at 28 days (Murki 2016), BPD at 36 weeks' PMA (Murki 2016), treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation (Murki 2016), and need for mechanical ventilation (Dhir 2016; Murki 2016). Secondary outcomes reported by Murki 2016 were: severe intraventricular hemorrhage, severe retinopathy of prematurity, pneumothorax, necrotizing enterocolitis, duration of positive pressure ventilation, and duration of oxygen supplementation. No additional review‐specified outcomes were reported by Dhir 2016.

In the two parallel‐group RCTs comparing CPAP levels for postextubation support, review primary outcomes reported by the studies were: death or BPD at 36 weeks' PMA (Buzzella 2014), mortality by hospital discharge (Buzzella 2014), BPD at 36 weeks' PMA (Buzzella 2014), treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation (Buzzella 2014; Kitsommart 2013), and need for mechanical ventilation (Buzzella 2014; Kitsommart 2013). Severe intraventricular hemorrhage was the only secondary outcome reported by both studies. Additional secondary outcomes reported by Buzzella 2014 were: severe retinopathy of prematurity, pneumothorax, necrotizing enterocolitis, severe BPD, duration of positive pressure ventilation, and duration of oxygen supplementation. Additional secondary outcomes reported by Kitsommart 2013 were: any intraventricular hemorrhage, pulmonary air leak, and nasal injury.

Qualifying short‐term physiologic measures reported by parallel‐group or cross‐over trials are displayed in Table 3. Seven studies reported eight oxygenation measures (Kitsommart 2013; Lavizzari 2014; Lomp 2010; Magnenant 2004; Miedema 2013; Murki 2016; Rehan 2001); three studies reported carbon dioxide measures (Lavizzari 2014; Magnenant 2004; Miedema 2013); one study reported two cardiac output measures (Beker 2014); five studies reported heart rate measures (Beker 2014; Lavizzari 2014; Lomp 2010; Magnenant 2004; Rehan 2001); two studies reported four blood pressure measures (Beker 2014; Magnenant 2004); and three studies reported four lung volume measures (Elgellab 2001; Lavizzari 2014; Magnenant 2004).

Excluded studies

We excluded 12 studies (see Characteristics of excluded studies). The most common reason for exclusion was wrong study design, with seven of the 12 studies identified as cross‐over trials without random CPAP level sequence allocation (Courtney 2003; Courtney 2011; Mukerji 2019; Pandit 2001; Pickerd 2014; Veneroni 2014; Zhou 2020).

Risk of bias in included studies

Methodologic quality varied amongst the included trials (Figure 2). All included studies had unclear or high risk of bias in at least one domain. No trials contributing primary outcomes were judged as having overall high risk of bias and in need of exclusion for planned sensitivity analyses.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements for each risk of bias domain for included studies.

Allocation

We judged all four parallel‐group RCTs to have low risk of selection bias. Random sequence was generated through computer or web‐based programs, and allocation was concealed through the use of sealed, opaque envelopes. In contrast, only two of seven cross‐over trials described low risk of bias for random sequence generation (Beker 2014; Lomp 2010), and only Beker 2014 described allocation concealment through the use of sealed, opaque envelopes.

Blinding

We did not identify any studies in which all participants and personnel were described as masked to the allocated intervention. In Beker 2014 and Rehan 2001, the investigator obtaining or recording the outcome measures was masked to CPAP level. We judged both of these studies as having a low risk of detection bias.

Incomplete outcome data

We judged attrition bias to be low for all trials except Dhir 2016, Elgellab 2001, and Lomp 2010. We assessed Dhir 2016 as at unclear risk of attrition bias on the basis of unclear reporting. Elgellab 2001 described conditional assessments at a CPAP level of 8 cm H2O, without enumerating final sample size at that pressure level. Lomp 2010 reported incomplete analysis in 19 of 56 infants, meeting the prespecified 20% threshold for high risk of bias for this review (Appendix 3).

Selective reporting

We identified trial registrations in 3 of the 11 studies (Beker 2014; Kitsommart 2013; Murki 2016). We judged two studies as having a low risk of reporting bias (Beker 2014; Kitsommart 2013). We noted incomplete outcome reporting for Murki 2016, but only for a few secondary outcomes, while all prespecified primary outcomes were reported, resulting in a judgement of unclear risk of reporting bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We judged there to be other potential sources of bias for Dhir 2016, as the trial was reported as a “Scientific Letter” with sparse methodologic details, and for Lomp 2010, as the study did not undergo peer review. Study details were obtained from a thesis published online.

Effects of interventions

Primary and secondary outcomes are described below; we judged meta‐analysis to be appropriate in all instances where more than one parallel‐group RCT contributed data.

We did not pursue subgroup analyses, as no single outcome included data from more than two studies. We did not perform sensitivity analyses, as outlier effects are not applicable to meta‐analyses of two trials; no studies contributing data for primary outcomes were judged as having a high overall risk of bias; and no studies to date have allocated participants to CPAP levels > 8 cm H2O.

All short‐term physiologic outcomes are summarized in Table 3 and below.

Comparison 1. Low (≤ 5 cm H2O) versus moderate‐high (> 5 cm H2O) CPAP levels for initial respiratory support

Primary outcomes

Death or BPD at 36 weeks' PMA

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 1: Death or BPD at 36 weeks' PMA

Risk ratio (RR) 1.02, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.56 to 1.85.

Mortality at 28 days

No trials reported this outcome.

Mortality by hospital discharge

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 2: Mortality, by hospital discharge

RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.51 to 2.12.

Mortality at one year

No trials reported this outcome.

Moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 26 months

No trials reported this outcome.

Moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 3 to 5 years

No trials reported this outcome.

BPD at 28 to 30 days of age

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.3).

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 3: BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen use at 28 days of age

RR 1.10, 95% CI 0.56 to 2.17.

BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen or positive pressure support at 36 weeks' PMA

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 4: BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen or positive pressure support use at 36 weeks' PMA

RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.25 to 2.57.

Treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 5: Treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation

RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.57.

Need for mechanical ventilation

Meta‐analysis of data from two trials (316 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.6).

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 6: Need for mechanical ventilation

RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.70 (I2 = 50%); risk difference (RD) 0.03, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.13; number needed to treat for an additional beneficial outcome (NNTB) 33, 95% CI −17 to 8.

Secondary outcomes

Cerebral palsy or gross motor disability

No trials reported this outcome.

Developmental delay or intellectual impairment

No trials reported this outcome.

Blindness

No trials reported this outcome.

Sensorineural deafness requiring amplification

No trials reported this outcome.

Severe intraventricular hemorrhage

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 7: Severe intraventricular hemorrhage

RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.21 to 2.81.

Periventricular leukomalacia

No trials reported this outcome.

Severe retinopathy of prematurity

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.8).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 8: Severe retinopathy of prematurity

RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.11 to 3.78.

Necrotizing enterocolitis requiring surgery

No trials reported this outcome.

Pneumothorax

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.9).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 9: Pneumothorax

RR 2.41, 95% CI 0.48 to 12.20.

Pulmonary air leak, any

No trials reported this outcome.

Rate of apnea and bradycardia

No trials reported this outcome.

Patent ductus arteriosus receiving medical or surgical treatment

No trials reported this outcome.

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.10).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 10: Necrotizing enterocolitis

RR 1.07, 95% CI 0.45 to 2.55.

Intraventricular hemorrhage, any

No trials reported this outcome.

Physiological definition of BPD

No trials reported this outcome.

Severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia

No trials reported this outcome.

Retinopathy of prematurity, any

No trials reported this outcome.

Duration of positive pressure ventilation

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.11).

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 11: Duration of positive pressure ventilation, days

Mean difference (MD) (days) 0.30, 95% CI −0.61 to 1.21.

Duration of oxygen supplementation

Data from one trial (271 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 1.12).

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, as initial respiratory support, Outcome 12: Duration of oxygen supplementation, days

MD (days) 1.20, 95% CI −2.13 to 4.53.

Length of hospital stay

No trials reported this outcome.

Days to establish full feeding

No trials reported this outcome.

Days to regain birth weight

No trials reported this outcome.

Weight gain at discharge

No trials reported this outcome.

Weight z‐score at discharge

No trials reported this outcome.

Growth failure at discharge

No trials reported this outcome.

Nasal injury

No trials reported this outcome.

Gastrointestinal perforation

No trials reported this outcome.

Short‐term physiologic outcomes

See also Table 3.

Oxygenation measures

Two of four studies reported improved oxygenation with increasing CPAP levels (Lomp 2010; Miedema 2013); no certain differences were noted in Lavizzari 2014 and Murki 2016.

Carbon dioxide measures

No certain differences were noted in Lavizzari 2014 and Miedema 2013.

Cardiac output measures

No certain differences were noted in Beker 2014.

Heart rate measures

No certain differences were noted in Beker 2014 and Lomp 2010.

Blood pressure measures

No certain differences were noted in Beker 2014.

Lung volume measures

No certain differences were noted in Lavizzari 2014.

Comparison 2. Low (≤ 5 cm H2O) versus moderate‐high (> 5 cm H2O) CPAP levels for postextubation respiratory support

Primary outcomes

Death or BPD at 36 weeks' PMA

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.1).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 1: Death or BPD at 36 weeks' PMA

RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.49.

Mortality at 28 days

No trials reported this outcome.

Mortality by hospital discharge

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.2).

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 2: Mortality, by hospital discharge

RR 2.94, 95% CI 0.12 to 70.30.

Mortality at one year

No trials reported this outcome.

Moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 18 to 26 months

No trials reported this outcome.

Moderate‐severe neurodevelopmental impairment at 3 to 5 years

No trials reported this outcome.

BPD at 28 to 30 days of age

No trials reported this outcome.

BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen or positive pressure support at 36 weeks' PMA

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.3).

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 3: BPD, defined as supplemental oxygen or positive pressure support use at 36 weeks' PMA

RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.49.

Treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation

Meta‐analysis of data from two trials (117 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.4).

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 4: Treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation

RR 1.52, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.50 (I2 = 17%); RD 0.15, 95% CI −0.02 to 0.32; NNTB 7, 95% CI −50 to 3.

We assessed the certainty of evidence as very low, downgrading one level for risk of bias, one level for inconsistency across studies, and one level for imprecision of effect estimate (Table 2).

Need for mechanical ventilation

Meta‐analysis of data from two trials (117 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.5).

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 5: Need for mechanical ventilation

RR 1.26, 95% CI 0.78 to 2.05 (I2 = 78%); RD 0.09, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.26; NNTB 11, 95% CI −13 to 4.

Secondary outcomes

Cerebral palsy or gross motor disability

No trials reported this outcome.

Developmental delay or intellectual impairment

No trials reported this outcome.

Blindness

No trials reported this outcome.

Sensorineural deafness requiring amplification

No trials reported this outcome.

Severe intraventricular hemorrhage

Meta‐analysis of data from two trials (115 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.6).

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 6: Severe intraventricular hemorrhage

RR 1.65, 95% CI 0.23 to 11.86 (I2 = 0%).

Periventricular leukomalacia

No trials reported this outcome.

Severe retinopathy of prematurity

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.7).

2.7. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 7: Severe retinopathy of prematurity

RR 1.96, 95% CI 0.52 to 7.36.

Necrotizing enterocolitis requiring surgery

No trials reported this outcome.

Pneumothorax

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.8).

2.8. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 8: Pneumothorax

RR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01 to 2.63.

Pulmonary air leak, any

Data from one trial (24 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.9).

2.9. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 9: Pulmonary air leak

RR 2.36, 95% CI 0.25 to 22.70.

Rate of apnea and bradycardia

No trials reported this outcome.

Patent ductus arteriosus receiving medical or surgical treatment

No trials reported this outcome.

Necrotizing enterocolitis

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.10).

2.10. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 10: Necrotizing enterocolitis

RR 2.94, 95% CI 0.32 to 27.21.

Intraventricular hemorrhage, any

Data from one trial (24 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.11).

2.11. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 11: Any intraventricular hemorrhage

RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.41 to 1.51.

Physiological definition of BPD

No trials reported this outcome.

Severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.12).

2.12. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 12: Severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia

RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.53 to 2.82.

Retinopathy of prematurity, any

No trials reported this outcome.

Duration of positive pressure ventilation

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.13).

2.13. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 13: Duration of positive pressure ventilation, days

MD (days) 5.00, 95% CI −2.35 to 12.35.

Duration of oxygen supplementation

Data from one trial (93 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.14).

2.14. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 14: Duration of oxygen supplementation, days

MD (days) −1.00, 95% CI −27.41 to 25.41.

Length of hospital stay

No trials reported this outcome.

Days to establish full feeding

No trials reported this outcome.

Days to regain birth weight

No trials reported this outcome.

Weight gain at discharge

No trials reported this outcome.

Weight z‐score at discharge

No trials reported this outcome.

Growth failure at discharge

No trials reported this outcome.

Nasal injury

Data from one trial (24 infants) showed an uncertain effect (Analysis 2.15).

2.15. Analysis.

Comparison 2: Low versus moderate‐high NCPAP level, following endotracheal extubation, Outcome 15: Nasal injury

RR 1.18, 95% CI 0.08 to 16.78.

Gastrointestinal perforation

No trials reported this outcome.

Short‐term physiologic outcomes

See also: Table 3.

Oxygenation measures

Rehan 2001 reported improved oxygenation with increasing CPAP levels; no certain differences were noted in Kitsommart 2013 and Magnenant 2004.

Carbon dioxide measures

No certain differences were noted in Magnenant 2004.

Cardiac output measures

No trials reported this outcome.

Heart rate measures

No certain differences were noted in Magnenant 2004 and Rehan 2001.

Blood pressure measures

No certain differences were noted in Magnenant 2004.

Lung volume measures

Elgellab 2001 and Magnenant 2004 reported higher tidal volumes with increasing CPAP levels. Elgellab 2001 reported higher end‐expiratory lung volumes with increasing CPAP levels.

Discussion

Summary of main results

There are insufficient data from randomized trials to guide nasal CPAP level selection in preterm infants, whether provided as initial respiratory support or following extubation from invasive mechanical ventilation. For both indications, we identified only two RCTs measuring clinically important outcomes. The outcomes reported by these studies varied, and the overall number of enrolled infants was modest. As a result, comparisons for meta‐analysis were few, and no certain differences between low and moderate‐high nasal CPAP levels were identified. Among outcomes prespecified for inclusion in the summary of findings tables, only treatment failure or need for mechanical ventilation in infants receiving CPAP for postextubation support was meta‐analyzed (Table 2). Though the effect estimate suggests potential benefit with moderate‐high CPAP levels, the estimate was uncertain (Analysis 2.4). The impact of CPAP levels on short‐term physiologic outcomes was unclear based on the available data (Table 3). Three of seven studies reported statistically significant improvements in varying oxygenation measures, but the absolute differences in these were modest and of uncertain clinical relevance. Changing CPAP levels seemed to have minimal impact on carbon dioxide, heart rate, and blood pressure measures. Additional studies are needed to develop evidence‐based recommendations for CPAP level selection in preterm infants.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The overall completeness of the available evidence was very low, and we were unable to make any definitive conclusions regarding the objectives of this review.

We planned to exclude studies published prior to 1990 to increase the applicability of findings to modern neonatal practice, but did not identify any otherwise eligible studies from this time period, therefore none were excluded. The included studies, particularly the four parallel‐groups RCTs contributing data to the primary outcomes, are applicable to modern neonatal practice (see Characteristics of included studies) (Buzzella 2014; Dhir 2016; Kitsommart 2013; Murki 2016). All of these studies were published between 2013 and 2016; enrolled populations that commonly receive nasal CPAP; and compared CPAP pressure levels generated with, and delivered through, currently used pressure sources and nasal interfaces. Both low‐/middle‐ and high‐income countries were represented in these four studies, although both studies comparing CPAP for initial respiratory support were conducted in a low‐/middle‐income country (India) (Dhir 2016; Murki 2016), while both studies comparing CPAP for postextubation support were conducted in high‐income countries (Buzzella 2014, the USA; Kitsommart 2013, Canada). Furthermore, Dhir 2016 and Murki 2016 enrolled a broader and more mature preterm population than Buzzella 2014 and Kitsommart 2013. As such, the applicability of the limited available evidence may be low for less mature preterm infants in high‐income settings when CPAP is given as initial respiratory support, and for more mature infants in lower‐income settings when CPAP is given as postextubation support.

The seven included cross‐over trials are also generally applicable to modern neonatal practice, but span a broader study era (2001 to 2014). All of these studies except Lomp 2010 (South Africa) were conducted in high‐income countries, and the studies enrolled few extremely preterm or extremely low birth weight (< 1000 grams) infants. Though four studies permitted the inclusion of such infants (Elgellab 2001; Lomp 2010; Magnenant 2004; Miedema 2013), the eligible populations were broad, and the central tendencies of enrolled infants suggest these extremely immature infants were few. Furthermore, the cross‐over studies generally enrolled infants that were stable on low levels of pressure support while requiring minimal supplemental oxygen. The overall suggestion that changing CPAP levels has modest impact on physiological outcomes may not be applicable to less mature infants with greater lung disease, precisely the population in whom consideration of higher CPAP levels is most relevant. Lastly, the duration of time required for equilibration of lung volumes following CPAP level changes is uncertain, and may vary as a function of the underlying disease state. Elgellab 2001 maintained CPAP levels for 30 minutes in each cross‐over period, citing preliminary tests that showed that up to 20 minutes are needed to achieve stabilization of end‐expiratory lung volumes after CPAP level changes. Beker 2014, Lavizzari 2014, Lomp 2010, Miedema 2013, and Rehan 2001 all evaluated outcomes within 20 minutes, raising the possibility that the applicability of these findings are limited by insufficient time allowed for equilibration of lung volumes following CPAP level changes.

Quality of the evidence

We graded the overall certainty of the evidence for the outcomes listed in the summary of findings tables to be very low based on the GRADE approach, consistent with very little confidence in the effect estimates (Table 1; Table 2) (Schünemann 2013). For all outcomes in both comparisons, we started with a default of 'high‐certainty' based on study design (RCT), downgrading for risk of bias, lack of consistency across multiple studies, and imprecision.

Regarding bias, we judged the study (Table 1) or studies (Table 2) contributing data to have a low risk of selection bias, but overall high risk of performance bias as participants or personnel were not masked to random CPAP level allocations. Knowledge of the allocation plausibly impacts clinical management decisions such as subsequent pressure level titrations and decisions regarding the need for mechanical ventilation. However, we acknowledge that masking CPAP level is pragmatically challenging and raises safety concerns. We judged there to be an overall unclear risk of detection and reporting bias due to the lack of detail surrounding masking of outcome assessors and inconsistent clinical trial registrations.